RESEARCH ARTICLE

Post-Domicide Artefacts: Mapping Resistance and Loss onto Palestinian House-Keys

Scott Webster

University of Sydney

Cultural Studies Review, Vol. 22, No. 2, September 2016

© 2016 by Scott Webster. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Citation: Webster S. 2016. Post-Domicide Artefacts: Mapping Resistance and Loss onto Palestinian House-Keys. Cultural Studies Review, 22:2, 41-64. http://dx.doi.org/10.5130/csr.v22i2.4726

ISSN 1837-8692 | Published by UTS ePRESS | http://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/journals/index.php/csrj/index

Corresponding author: Scott Webster, University of Sydney, Camperdown, NSW, 2006, Australia. scwebster.89@gmail.com

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5130/csr.v22i2.4726

Article History: Received 10/11/2015; Revised 15/05/2016; Accepted 20/06/2016; Published 18/11/2016

Abstract

This article is concerned with the experiences of domicide—that is, the suffering caused by the deliberate destruction of home by human agency in pursuit of certain objectives—faced by Palestinians as a legacy (as well the present) of the ongoing conflict with Israel. Existing scholarly and activist research provides some essential data about these experiences, but intellectual contributions remain primarily focused on the act of demolition or displacement. This act alone does not constitute ‘domicide’. What must follow is an attempt by the displaced to grapple with the whole affective dimension of being forcibly separated from home and the symbolic and creative responses that this begets. The significance house-keys have acquired within Palestinian inter-familial and communal customs, as well as within cultural (re)production, provides insight into this suffering. Attachment to the house-key is viewed as emblematic of feelings towards the lost home—a continuation of that connection by other means. This article explores the range of ways the key’s symbolic value has been reconfigured as it permeates different arenas of cultural production and activity, and how the keys have come to embody both loss of home and resistance of the goals of Israeli domicide.

Keywords

Domicide; Palestine; Israel; house-keys; The Promise; return; memory

Home destruction and forced exile are long-running features of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. Israeli historians Ilan Pappé and Benny Morris have revealed their prominent role in cementing the nascent Jewish State during the First Arab–Israeli War (1947–49).1 Through the fighting over 700,000 Palestinians were displaced from within Israel’s expanding territory and barred from ever returning—an exodus now known as al-nakba (Arabic for ‘the catastrophe’).2 Scholarly and mainstream debate argue over whether this exodus proves a deliberate ethnic cleansing campaign, yet its demographic outcome—a distinct Jewish majority in the State of Israel—remains clear.3

Pappé also identifies the relationship nakba-era home destruction had with ‘memoricide’: the vanishing of Palestine’s material cultural landscape as a means of expunging memory of Palestinian presence.4 Five hundred and thirty-one villages were destroyed and the coastal cities of Jaffa, Acre and Haifa depopulated of their Palestinian majorities.5 Many of these villages have been planted over with public parks and artificial forests, rendering their cartographical erasure permanent.6 It is a literal effacement of Palestinian residential geography, of markers and signs that (can) act to preserve history and memory. Without prior research or some lingering material ‘clues’ on the surface, it would be difficult to know that Palestinian villages once stood there. The framing mechanisms for these parks—the websites, the signposts—do not indicate what lies beneath the flora.7

Alongside academic work are the studies and statistical monitoring of Israel’s contemporary policies targeting homes by rights-based organisations Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch and the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UN OCHA).8 Groups such as the Israeli Committee Against House Demolitions (ICAHD), Zochrot and Badil have been founded to address many of these practices and their effects specifically.9 This collective research recognises the widespread destruction and theft by Israel and deconstructs the bureaucratic, legal and military regimes enabling policies of demolition, eviction, expropriation and deportation. Home as a valid ‘pressure point’—that is, leverage for disciplining Palestinians—features as a guiding principle for administering the Occupied Palestinian Territories (OPT).10 This disciplinary purpose is also linked to familiar themes of expansionism and influencing demographic ratios.

While providing essential data and intellectual contributions, the research by rights-based organisations is primarily concerned with the demolition or displacement act. In John Porteous and Sandra Smith’s view, this research covers the deliberate destruction of home by human agency in pursuit of certain objectives.11 This alone does not constitute ‘domicide’. It is the psychological hurt of losing home, different from equally important socioeconomic ruination or physical harm, that Porteous and Smith emphasise in creating the concept.12 What must follow, then, is an attempt to grapple with the whole affective dimension of being forcibly separated from home—including the means by which victims try to overcome its impact. This article examines the use of nakba-era objects—specifically house-keys—by Palestinians to convey hurt, memory and ownership. What do these practices and their symbolic filtration into various modes of cultural production reveal about domicidal suffering? What is their potential for combating the goals of domicide itself at a physical and temporal remove from the lost homes?

The vulnerable home

The pain caused by the loss of home is a complex phenomenon. This, in turn, is due to flexible interpretations of ‘home’. It can bear a ‘cluster of meanings’ including multiple, simultaneous ones; as diverse spatialisations as a single room (or individual’s psyche) to a country or region, even the planet and beyond.13 Literature has explored the meaningfulness of home with a view to its acute vulnerability. Vidler describes the ‘uncanny’: ‘the fundamental propensity of the familiar to turn on its owners, suddenly defamiliarized, derealized, as if in a dream’.14 In other words, the transformation of the homely (heimlich) into the unhomely (unheimlich).15 He cites this as an aspect of the ‘modern condition’, a pervasive feeling of being unsettled and rootless following world wars and severe economic depression.16 Lukács termed this ‘transcendental homelessness’.17 Dreyfus argues that this condition means ‘human beings can never be at home in the world’.18 Heidegger applies this to dwellings: ‘not a condition of being without a roof, but of not feeling “at home” with the house one has’.19 Hence the (often exaggerated) impulse to ‘make ourselves at home and secure’ that manifests within planning, architecture and politics.20

Existing research demonstrates the strong resonance of home with comfort and security.21 It even functions as a metaphor: to make yourself ‘at home’.22 This reappears in Ballantyne’s analysis: ‘The nest’, ‘a modest and comforting place to snuggle down and feel at home’, is set up against the opposing extreme, the ‘pillar of fire’ that aspires to awe and artistic prestige.23 The bird’s nest metaphor is fitting given the home’s role in a dichotomous relationship with outside.24 ‘The nest, which feels absolutely secure from within, is in fact precariously placed.’25 The home becomes a stable and known space in the face of external chaos and danger. Yet the pervasive uncanny suggests that closing off comforting enclaves from the world is perhaps futile. If we accept this analysis, the forcible separation from home becomes traumatic as victims lose an already limited sense of stability.

‘The home is clearly meant to be perceived very differently from inside and outside.’26 The design of homes has adapted bluntly to meet our need for feeling secure and ‘at-home’. In some cases this amounts to deliberately dispelling an external appearance of ‘homeliness’, as though visually signifying this enhances the dwelling’s vulnerability. Dennis Hopper’s home in Venice, California, is one instance; its white picket fence borders off a corrugated metal structure without windows.27 The dwelling’s exterior is as unheimlich as possible. The proliferation of gated communities provides a further example. Several essays collected in Ellin’s Architecture of Fear note these communities are motivated by (an often misplaced) paranoia about crime and shifting local demographics.28 They serve a dual function in securing a cluster of dwellings and sustaining a particular communal identity. Though at times ineffective in preventing crime, the walls and gates, guard-stations and cameras communicate unhomeliness to outsiders. Meanwhile, the home security industry fortifies individual dwellings with these and other unheimlich products.

Control joins comfort and security as essential to the home. This reached an extreme expression at New York’s World Fair 1964, only two years after the Cuban Missile Crisis. One display at the fair was the Underground Home, ‘a traditional suburban ranch house buried as protection from the new threat of nuclear fallout’.29 A publicity brochure reads: ‘A few feet underground can give man an island onto himself; a place where he controls his own world—a world of total ease and comfort, of security, safety and, above all, privacy.’30 The unique response to the threat of nuclear fallout aside, the publicity brochure reaffirmed domesticity’s familiar themes: comfort, security, privacy. Present in each theme is an element of control. Home as an enclosure of controlled space, however, achieves its zenith with the bunker-home’s mechanisms: controllable temperature, ‘dial-a-view’ for each window, even mastery over the ‘time of day’.31 As the brochure claims, in the bunker-house you control the previously uncontrollable: the world. The nest should not be taken for granted though. It can have a dark side—from psychological traumas and phobias (agoraphobia and claustrophobia) to financial over-commitment and domestic violence.32 Ballantyne notes that murder within the household is more likely to be committed by one member of the household upon another.33 The uncanny does not exclusively emerge from the world outside.

Home is meaningful, regardless of how it resonates. So too is its loss; whether it be a loss of control, security, comfort, privacy, rootedness or community. Israel’s long-term refusal to deal with domicide has seen the forms suffering manifests ‘take on a life of their own’. Bshara has written on the semiotics of the Palestinian house-key, with a focus on its role in identity formation and ‘keeping memory alive’.34 He traces the key’s unfolding use-values and symbolic-values as ‘capital’ within an economy of resistance. His is an influential precedent, and in this article I share a number of its observations, including a case study looking at Aida’s Return Key monument. Where my analysis differs is in identifying how the key’s evolving customary and symbolic use transforms the meaningfulness of home loss into both a deliberate sociocultural creative strategy and a rhetorical means of resisting domicide.

Inheriting exile: the Return Generations

‘My grandfather left the key to my father, my father left it to me and I will leave it for my son. We will never ever forget our house.’

Nasser Flaifel, ‘“Key of Return”, A Marriage Gift in Gaza’, 200535

‘When my father died, I got the key and I hold onto it with the hope of returning to my homeland.’

Munther Ameera, ‘Palestinian “Key of Return” on show at Biennale’, 201236

For many refugees of al-nakba house-keys remain the only tangible link to their lost homes. Domicide victims do not usually languish long without shelter. But they still suffer, a pain caused by having their connection to home permanently ruptured.37 Palestinian refugees demonstrate this ongoing hurt by refusing to discard their now functionless house-keys. These objects no longer serve a practical purpose, they cannot unlock anyone’s front door. Holding onto these redundant artefacts, then, clearly has other significance.38 Letting go would be tantamount to accepting the loss of home and surrendering that bond. The connection to home thus survives, albeit in damaged and diminished form, through safeguarding the key—an effect aided by the meanings invested in such a practice.

The two refugees quoted above reveal how this connection is sustained through mapping resistance onto the post-domicide key. For Flaifel, salvaging the key preserves the memory of ancestral history (‘We will never ever forget our house’). This acts as a challenge to the attempted memoricide of Palestinian history—at least as regards those most affected by it, and their descendants. ‘Memories’ of ancestral homes, of rightful ownership and belonging, are preserved; connection to a lost home is established by other means. Meanwhile Ameera channels a desire to return to his ‘homeland’ through his key, as though the artefact itself is the source of that wish’s legitimacy. This confronts another deliberate consequence of al-nakba domicide—the Jewish demographic majority it cultivated for the newly established State of Israel.

It is a disavowal of the current dwelling situation in favour of the lost, ‘legitimate’ home. Studies of exiled peoples and their feelings of home identify current residences as seeming inauthentic, false or otherwise inferior.39 The exiled are not ‘at-home’ in the house they live in. Exiles often attempt to recreate or mirror home in the way they organise and decorate their new surroundings.40 Tuan suggests that home acquires its strong resonance from to the accumulation of memories.41 Douglas echoes this in describing home as a ‘memory machine’, its physical dimensions and contents functioning as stimulants for reflecting and reliving memories.42 The key-artefact may act as a memory trigger in lieu of the home surroundings. Regardless of the explanations for this hyper-attachment, the key-artefact figures as an object for expressing a state of exile, of home as elsewhere and unobtainable but still existing.

If the house-key confirms this for first generation refugees, its inter-generational passage similarly confers exile onto new owners. Recipients essentially inherit exile. Both Ameera and Flaifel present this custom’s basic function. Home remains the place that was stolen or destroyed, from where grandfathers and great-grandfathers were displaced, and not the dwelling their families have inhabited since. They refer to the place regarded as home as ‘my homeland’ or ‘our house’, even though these homes only exist as constructions imagined through the accumulation of oral histories, surviving artefacts and photographs. It is unlikely either have ever set foot in the lost home or neighbourhood, but there is a demonstrated yearning for these places that has been cultivated within each family. In signifying and confirming an ancestral home and a responsibility to undo the damage caused by domicide, the practice of passing down keys aims to create and sustain ‘new’ Return Generations.

In isolation, keeping keys presents a significant yet limited challenge to domicide’s goals. Certainly it is of great importance to the concerned families. As a political tactic, it is dwarfed by the broader memoricidal project. However, in sustaining a belief in the ‘right of return’ across generations, the inheritance custom does combat Israel’s demographic intentions. This much is clear in Israel’s historical and contemporary efforts to prevent refugee return. If an ethnic cleansing campaign did not exist during 1947–48, it has certainly existed in the subsequent obstruction of return. A return to property (or restitution should the property be destroyed) is mandated under international law—specifically Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention and subsequent resolutions at the United Nations (General Assembly Resolution 194)—regardless of whether the exodus was voluntary or not.43 Refugees were actively prevented from returning and the emptied residences, villages and neighbourhoods that still stood were either resettled with Jewish immigrants or demolished.44

The Oslo peace process (1993–95) witnessed no commitments to allow refugees’ return, as this issue was delayed until final status talks that never eventuated. Meanwhile, posturing within negotiations for Palestinian recognition of Israel as the Jewish State has presented another obstacle to return. Recognition of this nature is not the same as recognising Israel as a nation-state. Rather, it would operate as acceptance of Israel’s demographic character and, by extension, measures to preserve that character. Erekat, one of Palestine’s negotiators, argues such discourse exists primarily to thwart any refugee return—to literally enforce a point of no return.45 Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu was explicit about this during the 2013 Kerry-led peace talks, declaring, ‘give up your dream of the right of return. We will not be satisfied with recognition of the Israeli people or of some kind of binational state which will later be flooded by refugees.’46 Apocalyptic adjectives and phrases, such as the state would be ‘destroyed’ or ‘cease to exist’, often frame the scenario of return.47 It continues a discourse that existed as far back as 1948. Anxiety over the demographic balance within Israel shaped the Declaration of Independence 1948 and the Law of Return 5710–1950.48 Despite these measures, and Netanyahu’s categorical rejection of return, it remains an explicit concern on both sides. The inheritance custom contributes to this durability.

Aida’s Return Key: imagining community through domicidal loss

The Return Key monument, known alternatively as the ‘Gate of Return’, is situated in Aida, a West Bank refugee community formed out of al-nakba.49 With the Separation Wall pressing in from three directions, only a few passages exist for visitors and residents to cross through.50 Framing one of these is the ‘Gate of Return’: a twelve-metre high archway crowned with an immense ‘skeleton’ key sculpture (see Figure 1).51 Moulded from two tonnes of iron, the Return Key stretches ten metres wide from bow-to-blade.52 It is modelled in the same style as the keys the original Return Generations were left with. A slender, elongated shaft connects the blade to the ringed (or oval-shaped) bow. Messages, mostly in Arabic, are scrawled along the sculpture’s surface. Visible among them is a large, red rectangle containing the phrase ‘Not for Sale’. The arch-threshold continues the key paraphernalia theme, its interior curves angled to resemble a broad keyhole.

Figure 1

Aida’s ‘Gate of Return’, Aida, Palestine

Photo: Scott Webster, 2013

Monuments have been described as devices for forging communal meanings and identities.53 Aida’s Return Key embodies this function by attempting to import the private significance of the key into public space.54 Ameera, who also had the idea for the structure, claims the intent was for ‘our children to look at the key memorial and think of the day they will return to their motherland’.55 He recognises the need for the key-signifier to be turned outward and address those beyond the family unit if it is to effectively disrupt forgetting. An account of the monument’s inauguration, which coincided with the annual al-nakba commemorations, reflects this goal. It began on 8 May 2008 with a march, called Ajiall al-Awdeh (the Return Generations), which wove through Bethlehem and its adjoining refugee camps: Dheisheh, Azza and finally Aida.56 The march, and its name, demonstrates an effort to unify these separate communities behind the monument. A collective identity—an ‘us’—that it addresses is cultivated, grounded in a shared legacy of domicidal victimhood. At Aida, the oldest refugee present ‘christened’ the monument by handing down his key to his grandson.57 This public enactment of a normally private affair reinforced what the structure is meant to replicate at a communal level.

The constricted space produced by the Separation Wall is used to subvert its intended effect on the population. The Return Key acquires a visual and spatial dominance within a frequently traversed area, thereby reaching more individuals than the intimate family practice it mimics. Necessarily this includes Palestinians, such as younger siblings or those born in the camp, who will not directly inherit a family key, thus encouraging a collective sense of inclusion in the Return Generations. These efforts in forging communal linkages extended to a small section of the diaspora during Berlin’s 7th Biennale, which featured the sculpture as an exhibit. Local Palestinians brought their own key-artefacts, displaying common recognition of the object’s significance. The key-signifier resonated between the Palestinians of Berlin and Aida, acquainting both with the notion of belonging to a greater community—an ‘imagined community’.58 Messages written on the Return Key, many still present, carried these ties back home to Aida’s residents. This minute effort to connect disparate groups of Palestinians, with the house-key’s rallying symbolism at its core, highlights a form of resistance. The heavily dispersed refugee communities are bound through their joint history of displacement.

Meanwhile the message intended for non-refugees, particularly Palestinians involved in endless peace negotiations, is of an altogether different nature. The monument demarcates communal boundaries as much as it encourages members, as it overshadows the line between the Aida refugee community and Bethlehem’s urban sprawl. Bshara writes that instances of nakba commemoration, and the increasingly public visibility of key exchanges, are a predominantly post-Oslo phenomenon, a reaction to the seemingly negligible (even expendable) treatment of the right of return since Oslo.59 As the sculpture declares, this right is ‘Not for Sale’. The key transforms from an object to map out feelings of grief, loss and memory into an outwardly focused declarative symbol: the right of return must not be surrendered.

The Return Key monument also features as a bold challenge to the domicidal goal of erasure. It stands in defiant contrast to a sign of Israel’s Occupation, the Separation Wall, literally placing the symbol of enduring memory on a pedestal beside it. Till suggests that public collective memory is ‘the dynamic process by which groups map myths … about themselves and their world onto a specific time and place’.60 Johnson identifies this ‘mapping process’ within continuing efforts to forge collective identities, which are coded into monumental architecture and their associated ceremonies, as in the case of Aida’s Return Key, which is inscribed with a Palestinian narrative of displacement and domicide.61

It is tempting to view the structure as akin to a war memorial, importing individual trauma and loss into the public realm to construct an idea of communal grief. The monument is a focal point of al-nakba commemoration each year, encapsulating what Nora terms a ‘site of memory’.62 These sites become the epicentre of public ritualisation and commemoration of dates and events, in this instance al-nakba. However the Return Key is not exclusively a stage for select days. Rather, these commemorative events reinforce and enhance its daily visibility and embodied meanings, complementing the construction’s everyday anti-memoricide.

The positioning and physical dimensions of the Return Key serve other strategic purposes: much like any public statuary it is intended to attract visitors. The creators encourage its association with ‘big thing’ tourism—even going so far as to campaign Guinness World Records for its recognition as ‘the world’s biggest key’.63 The Return Key is undoubtedly an attraction, as can be seen in my visit to it with the Israeli Committee Against House Demolitions (ICAHD) as part of its annual camp’s tour package. The ICAHD’s decision to bring campers to the ‘Gate of Return’ highlights the landmark’s capacity to draw international interest. The Return Key as an attraction is reinforced on its related webpages for Berlin’s Biennale exhibit. Videos capture how the Key’s journey was itself shaped into an advertisement.64 The canvas sides of the truck’s trailer were removed as it exited customs, the Key within left upright and visible to all as it travelled to its destination in Berlin. The unusual sight was clearly intended to lure curious onlookers to the exhibit.

The key in Badil’s al-Awda Awards

Badil, the Resource Centre for Palestinian Residency and Refugee Rights, annually invites submissions for the al-Awda (The Return) Awards, its creative competition commemorating al-nakba.65 Besides celebrating talented Palestinian artists, these events are intended to foster a feeling of belonging to a wider (imagined) community—much like Aida’s monument. The commemoration of al-nakba anchors that communal identity in a shared legacy of displacement and ‘culture of return’ as Palestinians across the globe artistically express its impact. The ‘headline’ since 2007 is the poster design category, with hundreds of submissions received each year. The first-place winner, chosen by an independent jury panel, is confirmed by the National Nakba Commemoration Committee (NNCC) as that year’s official poster.66 The NNCC comprises representatives from several Palestinian national movements and networks, as well as the PLO Department of Refugee Affairs.67 It is responsible for the organisation of commemorative events and, thus, offers canonical weight to the winning posters—many of which feature house-keys. Alongside local distribution, many submissions circulate online through Badil’s website, Facebook page and other social media.68

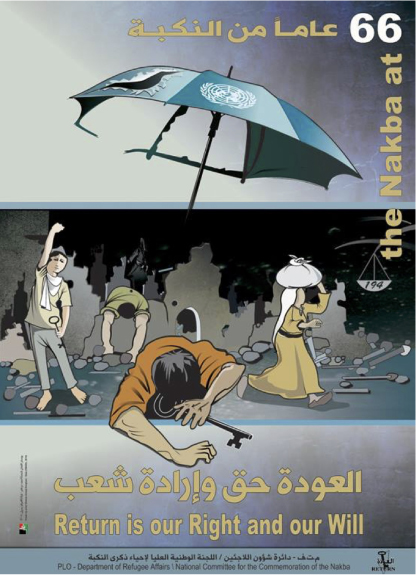

Both the 2013 and 2014 first-place winners use the key symbol to articulate its base importance to Palestinians. The winner in 2014—a poster submitted by Shehda Durgham from Jabaliya (Gaza Strip)—features a ruined umbrella displaying the United Nations’ emblem (see Figure 2). It is ripped and torn, incapable of shielding its user. Below it lies a scene of devastation: buildings reduced to rubble; a body slumped over a partially remaining wall; people fleeing or stumbling through the mess. The poster asserts the failure of the United Nations to protect Palestinians. The umbrella used as a shelter from fallen objects might indicate that Israeli drone strikes caused the destruction, the scenes are reminiscent of images from Gaza. Regardless of the specifics—and it is just as likely to be a metaphor for general Israeli aggression and UN failure to intervene—the image presents a narrative where Palestinians are under great duress. Notably, many of the figures depicted cling to their keys. One character clasps their key while brandishing his fist at the heavens defiantly. Another—the most central figure in the scene—pushes himself off the ground, a large skeleton key in hand. Even under extreme circumstances these Palestinians are shown to value their keys above all other possessions. This interpretation of keys as an affirmation of Palestinians’ right to return is guided by the underlying phrase: ‘Return is our Right and our Will’.

Figure 2

Shehda Durgham, Poster 2014

© Badil Center

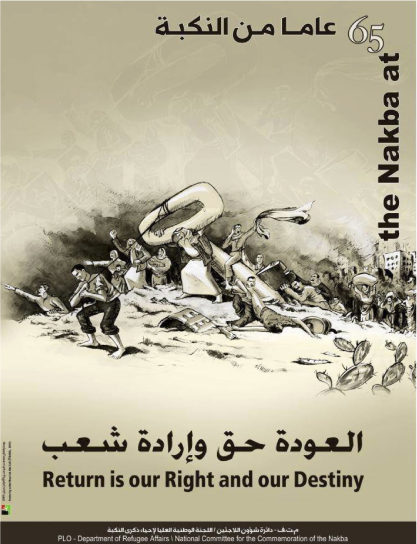

Musa’ab abu Sel, also from Gaza, received first place in 2013’s al-Awda Awards (see Figure 3). In his poster, a crowd of Palestinians are depicted heaving a large and cumbersome key—some are pulling it forward, others are carrying or pushing it. Behind them are signs of destruction, with smoking buildings and more crowds of refugees. The size of the key, and the numerous hands required to shift it, mirror Aida’s monument in representing the joint effort necessary to secure return. A communal burden is identified, the physical exertion emphasising the difficulties involved in achieving return. Yet, despite these difficulties and the nearby carnage, the task is still attempted. One particular figure is portrayed riding the monolithic key and waving a Palestinian flag, heralding ‘Palestine’ as the crowd’s destination and the key’s function. Much like Durgham’s design, the phrase ‘Return is our Right and our Destiny’ reinforces the poster’s use of key symbolism to indicate the will to return and undo the consequences of nakba-era domicide.

Figure 3

Musa-ab abu Sel, Poster, 2013

Source: © Badil Center, reproduced with permission

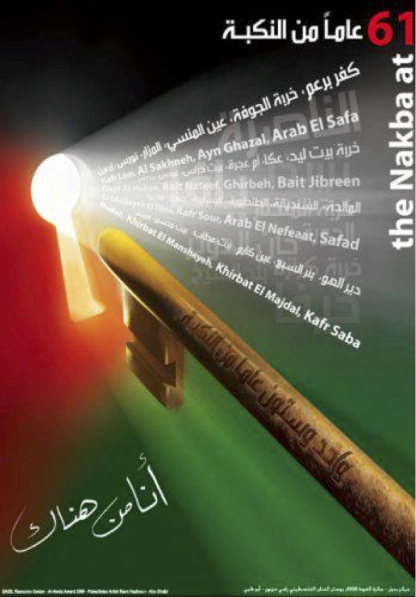

The key, and by extension return, is visualised as the catalyst for actualising Palestinian nationhood. Rami Hazboun’s award-winning entry bluntly demonstrates this (see Figure 4). A keyhole emanating light appears on a background bearing the Palestinian national colours. The names of lost villages, in English and Arabic, emerge from the beam of light, inferring that the key approaching it shall ‘unlock’ them. In this sense, the key-signifier has an anti-memoricide function. The background, meanwhile, hints that the unlocking would be part of a broader process involving ‘Palestine’ as a whole.

Figure 4

Rami Hazboun, Poster, 2009

Source: © Badil Center, reproduced with permission

Nationhood and return are consistently drawn together in these representations, the latter (represented by the key) depicted as leading to the former. Significantly, these posters also identify domicide’s relationship with nation-making (and nation-breaking). Advancing the narrative of return and nationhood, positions rectifying domicide’s effects as essentially (re)building the nation. The key serves a geopolitical function. Conversely, domicide’s role in hindering nationhood, by entailing the necessity for a call for return, is simultaneously confirmed.

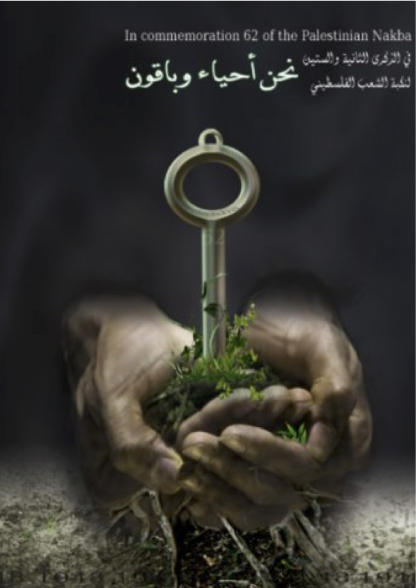

A symbolic entanglement with trees, roots and the earth also envelops the key. In some instances the key substitutes as ‘roots’, such as in Mustafa Akram Badr’s 2012 prize-winning entry (see Figure 5). This particular poster lines up a sequence of root systems. The top half portrays the sun beaming down on a field of plants; the bottom half depicts their roots beneath the surface. To the right is the natural root system for the adjoining plant. The middle inserts the shaft and blade of a key in place of the plant’s proper roots. This develops a metaphor for indigenous ancestry and ties to the land—in other words, Palestinian ‘roots’. It highlights another instance whereby the post-domicide key metaphorically asserts belonging. Posters like Mohammed Ja’edi’s from 2010 extend this metaphor with depictions of keys being ‘planted’ (see Figure 6). These keys do not unlock doors or relate to specific dwellings. They confirm a connection to the land, general and broad.

Figure 5

Mustafa Akram Badr, Poster, 2012

Source: © Badil Center, reproduced with permission

Figure 6

Mohammed Ja’edi, Poster, 2010

Source: © Badil Center, reproduced with permission

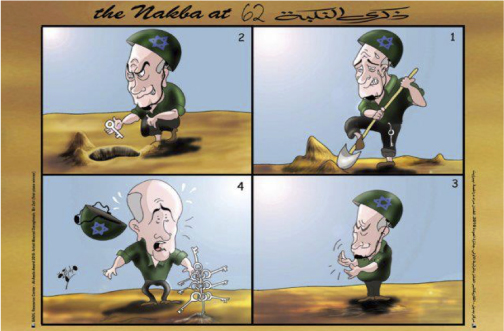

Inheritance and memory converge in 2010’s first-place caricature submitted by Morad Nael Rashed Doraghmeh of Ramallah (see Figure 7). A cartoon rendition of Benjamin Netanyahu appears across a four-panelled comic strip. In the first panel, he seems to be digging a hole in the desert while clad in military gear. The subsequent panel reveals that he is burying a key. This act represents efforts to deny memory of domicide, and the domicidal goal of memoricide, in the narrative of 1947–48. It also brings to mind persistent efforts to prevent return. Yet, in the cartoon, to Netanyahu’s comical surprise, a ‘plant’ comprising many additional keys has sprouted at the burial site by the final panel. This depiction presents another example of keys intersecting with flora and the earth, which equally embodies the resistance mapped onto the key. Memory is preserved through the inheritance custom—producing more keys and thus more Return Generations.

Figure 7

Morad Nael Rashed Doraghmeh, Caricature, 2010

Source: © Badil Center, reproduced with permission

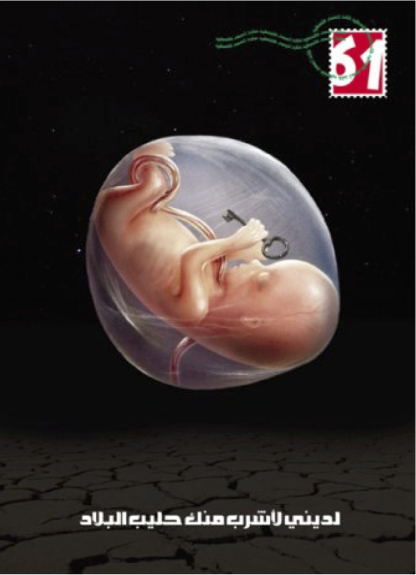

The trans-generational scope of the Return Generations has been imagined creatively among other entrants. Joining Doraghmeh’s ‘key-plant’ as a more inventive interpretation is Kamel Roubi’s entry from 2009, which goes so far as to present a baby, still in its mother’s womb, holding the key (see Figure 8). Creativity aside, each poster communicates a similar message. The key asserts belonging to the Return Generations, unrestricted by the passage of time.

Figure 8

Kamel Roubi, Poster, 2009

Source: © Badil Center, reproduced with permission

Persistent across the disparate themes is a fixation on particular ideas and values about space: memory, return, indigenous ancestry and roots, inheritance. Each representation at least in part relates to a metanarrative, a conceived space defined by Palestinian ownership, presence and belonging. The dissemination of these and similar works is a way to transfer that knowledge and potentially shape how individuals may regard the spaces they are concerned with. It is a creative strategy to combat the effects of domicide and memoricide. As the competition’s name—al-Awda (The Return) Awards—indicates, these artworks also service Badil and the NNCC’s interest in encouraging a belief in the right of return. That these representations originate from a broad cross-section of Palestinian society reinforces the key’s status as a symbol for an imagined community, one that actively resists the Israeli campaign of fragmentation represented in the denial of return, blockade of Gaza and the cantonisation of the West Bank.69

The Promise: exposing post-domicide landscapes and suffering

On 14 February 2012 SBS managing director, Michael Ebeid, fronted an Estimates Committee of the Australian Senate.70 The hearing began with a focus on the public broadcaster’s decision to screen The Promise, a four-part British television mini-series set in Israel and Palestine.71 Israel’s local supporters and lobby groups had campaigned against the program since its premier, alleging anti-Semitism and unbalanced portrayals. The Executive Council of Australian Jewry (ECAJ) submitted an extensive complaint to the SBS and demanded sales of DVDs stop immediately while the matter was investigated.72 This echoed efforts in the United Kingdom to tarnish both the series and those who chose to air it. Israel’s London embassy published a condemnatory statement, claiming the series ‘created a new category of hostility towards Israel’.73 Ofcom, the UK broadcast regulator, was prompted into an inquiry by numerous complaints before it ultimately cleared the program of conduct violations.74 Demonstrable interest in undermining this series, which has the Palestinian house-key central to its plot, clearly existed among Israel’s networks.

The Promise alternates between two plot threads. Sergeant Leonard ‘Len’ Matthews, part of the British military stationed during the final years of Mandatory Palestine, witnesses the campaign against the Jewish Irgun militia and the beginning of al-nakba. Those experiences are relayed through his diary to Erin, his granddaughter. Erin is spending part of her gap year in modern-day Israel with her best friend, Eliza, who undertakes her Israel Defence Force (IDF) service. However, as her grasp on the contemporary situation disrupts the middle-class veneer of Eliza’s home, Erin discovers a house-key belonging to her grandfather’s Palestinian friend. She decides to fulfil Len’s promise to return it to Abu-Hassan Mohammed, beginning an odyssey that exposes the wider realities of Occupation from Israel proper to Gaza. The artefact becomes an aporetic device, engaging the viewer with the history and significance of domicidal suffering as Erin’s preconceptions unravel.

The key first appears during the critical juncture of Erin’s stay. Having survived a suicide bombing with Eliza’s brother, Paul, Erin is shaken and keen to leave. Concurrently she has been reading about her grandfather’s experiences fighting the Irgun, including a first-hand account of the King David Hotel bombing. Parallels are established between modern Palestinian terrorism and the Irgun through the rotating depictions of past and present bombings. The Meyers’ revelation that Eliza’s grandfather helped perpetrate the blast that nearly killed Len distresses Erin, causing her to reach breaking point. An impulsive flick forward to the final page of her grandfather’s diary, however, reveals a troubling tonal shift—guilt ridden and despairing. Len mentions a key and the need to return it. Erin finds the artefact in an attached envelope; the discovery and the diary’s mysterious words convince her to stay. The key represents unanswered questions, both for Erin and the viewer, being without context within the narratives thus far. Her subsequent investigation into the key’s ‘meaning’ drives the plot and initiates a journey traversing multiple post-domicide landscapes across Israel and the Occupied Territories.

Erin’s pursuit of the key’s significance reveals a family history uprooted by three instances of domicide. These span the three crucial periods of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict: al-nakba, the ‘Six Day War’ and the ongoing Occupation. The key acts as a conduit that unveils a plurality of historical and contemporary issues despite being a nakba-era artefact. Erin’s first destination is Ein Hod—the location of the home the key is meant to unlock. Erin expects an Arab village and brings Omar (Paul’s Palestinian acquaintance) along to help with translation, but encounters a town that has been ethnically cleansed. Omar then takes her to the nearby Ayn Hawd, the village local Arabs eventually established after being internally displaced by al-nakba. Erin learns how the inhabitants discovered their homes were being lived in by Jewish immigrants, and were forced to build a new village further up the mountain. After driving through Ein Hod with a former resident, they find the home they are seeking and learn Len’s friend has relocated to Hebron.

Erin’s search heads into the Occupied Territories. While in Hebron, Erin eventually learns that the family had been displaced again through the ‘Six Day War’. The final destination is Gaza, the discontinuous coastal enclave subjected to a complete naval, air and land blockade. Erin finally reaches the last surviving member of Abu-Hassan’s family who knew her grandfather—the daughter, Jawda. It is here that Erin witnesses firsthand the family’s third experience of domicide: the family home is demolished as punishment for the family being related to a suicide bomber. Erin succeeds in returning the key to its rightful owner, but she is unable to prevent the third displacement. The nakba-era key, then, delineates a pathway that broadly covers domicidal practice and generational suffering over the conflict’s course, rather than exclusively focus on the events of 1947–1948.

Erin’s journey is underpinned by an education in the significance of home. When travelling through Ein Hod, Erin cannot empathise with the elderly Palestinian’s reluctance to visit his former village. ‘I don’t see what the big deal is.’ After the trip, the man pointedly thanks Erin. Omar translates: ‘He is thanking you. He is saying it was good to go, even though it’s painful.’ Erin is visibly taken aback by his outpouring of gratitude. She receives another lesson when she finally shows the key to someone. She presents it to Omar, hoping to convince him to take her to Gaza, with the subsequent exchange delving into the artefact’s meaningfulness:

Omar: ‘You don’t know what this is, do you?’

Erin: ‘… It’s a key?’

Omar retrieves a box stored for safekeeping, removing a carefully wrapped metal key from it: ‘That was my uncle’s key to his house in Jaffa. It passed to me when he died. It was his most precious possession.’ Erin is confronted with the hyper-attachment to home, as embodied by the ‘precious’ key. The inheritance custom is also explained, adding weight to her grandfather’s urgency and fuelling her own felt need to return the key to its rightful owner.

So far Erin has been driven by the ambiguous ending of her grandfather’s diary. But once her search reaches Gaza, the viewer witnesses her transition into embracing the value of home. Motivated by the perceived injustice of the impending domicidal act, she chains herself to a pillar in Jawda’s home. Erin has evolved from her original, uncomprehending position on the emotional complexity of ‘home’. As she pleads with Eliza not to cut her free, Erin unknowingly echoes Abu-Hassan when arguing with Len about leaving: ‘This is my home. I was born in this house.’ Erin desperately appeals to Eliza: ‘This was his home. He died in this house.’

Later, after the house has been destroyed, Erin rummages through the wreckage for belongings. This results in a precarious moment where a bulldozer almost runs her over. Erin stands her ground, risking injury or worse to secure mementoes for Jawda. The gesture, salvaging artefacts to remember with, is clearly important to her. It is notable that the photo album used in an earlier scene is saved, bearing with it connotations of memory. Potentially these objects, like the key, could become symbols in their own right. Furthermore, as Erin hands the rescued belongings back to Jawda, Israeli troops intervene and attempt to confiscate them. The resulting struggle causes Erin to lapse into an epileptic seizure, emphasising the emotional and physical toll of her journey and empathy for Palestinian domicidal suffering. The key-artefact initiated this journey, and acts as a catalyst for Erin to bear witness to, and herself endure, domicidal pain.

In contrast to Aida’s Return Key, the signifier in The Promise predominantly addresses non-Palestinian viewers. The plot inverts the inheritance custom, deploying it as a narrative device positioning Erin (and the viewer) in the place of the inheritor. Abu-Hassan Mohammed passes the key down to his son at the moment the family decide to temporarily leave. ‘I told him it is his responsibility to keep it safe … because one day we will return.’ The key is bound to the notion of return, as the physical object is in reality. Tragically, Abu-Hassan’s son dies after staying behind to fight the Jewish militias. He hands the key to Len, telling him to give it back to his father. It falls to Erin to fulfil the titular promise by returning the key and restoring the link between Abu-Hassan’s family and their original home. The motivations and investment in the custom, and the urgency and longing to restore home it bestows, transfers to Erin, who develops a sense of its deeply felt importance for Palestinian refugees. In her position as protagonist, Erin’s gradual shift into reinforcing the value of home specifically encourages the audience to adopt that same stance through her.

Conclusion

The deliberate, permanent separation of Palestinians from their homes is heavily implicated in Israel’s historical production of space, as it cultivated the necessary demographic character and borders for the ‘Jewish State’ via the First Arab–Israeli War. The imaginative geography—‘a land without people, for a people without land’—that negates Palestinian inhabitation is augmented by the way domicide removes structures and markers that act as triggers for memory.75 It would require specific knowledge of the conflict and local history for a visitor to see through the imposed narrative while passing over destroyed or through resettled villages of al-nakba. Qastal, one of the first villages around Jerusalem to be uprooted in 1948, encapsulates this point.76 An Israeli monument vaguely casts the site as an ‘enemy base’, occluding any sense that the space was once lived in, that it entailed homes.77 Domicide and its supporting mechanisms—post-nakba green-washing and renaming; the present day occupation apparatus—have entrenched this ‘knowledge’ of space, making it difficult to counter.

Difficult, but not impossible. As Porteous and Smith note, ‘memoricide proves a much more arduous task’ than domicide.78 The affective energies of home, and its forced loss, have led to a range of sociocultural and creative phenomena communicating and sustaining the idea of a Palestinian homeland. House-keys are kept and passed down by refugees, with younger generations confirming home as the properties lost in al-nakba. The importance of this custom cannot be understated. Palestinian refugees effectively prevent the passage of time from becoming an aid to memoricide by inheriting domicidal victimhood. A continuation of the Return Generations is encouraged even when the original domicide victims pass away. But in this form resistance is otherwise limited. The key-signifier must reach beyond the intimate family setting of its customary use if it is to effectively oppose domicide’s goals.

As Bshara argues: ‘Keys have become the par-excellence symbol of the lost homes, and the signifier of ongoing exile.’79 In some instances, such as Aida’s Return Key monument, the key binds disparate communities together through a shared legacy of displacement—an emergent national icon. This is reflected in numerous entrants for Badil’s al-Awda Awards. Both also exemplify the signifier’s purpose in encouraging a groundswell around the notion of return—a notion that runs completely contrary to Israel’s internal demographic intentions. The Promise presents its filtration into non-Palestinian production and contexts. Clearly it caused a reaction. Criticism, particularly in Australia, focused on the greater sympathy generated for Palestinians; the key, a plot device as analysed, is central to building this representation. It is tempting to view these case studies as evidence of the key-signifier’s permeation of local, national and international circulation (though there is varying overlap between them). In any case recognition of the key as a symbol for enduring memory and intent to return exists broadly.

But as Erin discovers when returning the key, the signifier’s spread and effectiveness has its limits. Punitive and administrative demolitions still occur in the OPT. The Wall constricts the growth of Palestinian jurisdictions while Israeli settlements expand, some well beyond the pre-Occupation borders. Already some settlements have been lived in for generations. As time passes, more and more Israelis come to experience these illegal towns as their home. The challenge for advocates of a ‘two-state solution’ is that these homes would need to make way for a Palestinian state in the West Bank to be viable. It threatens another wave of domicide. This does not excuse the crime of nakba-era domicide nor diminish its lingering effects discussed here. Nor does it excuse the illegality of the settlements’ foundation. It especially should not be used as a reason to force an unviable, discontinuous state on the Palestinians. What it does mean is that the question of domicide—past, present and future—must be engaged with in any serious proposal for conflict resolution.

About the author

Scott Webster is a PhD candidate in the Department of Gender and Cultural Studies, University of Sydney. He researches in the fields of memory studies and cultural studies.

DECLARATION OF CONFLICTING INTEREST The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. FUNDING The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Bibliography

Abu Salem, S., ‘“Key of Return”, a Marriage Gift in Gaza’, in Electronic Intifada, 15 May 2005, http://electronicintifada.net/content/key-return-marriage-gift-gaza/5588

Aida Youth Center, ‘History of Aida Refugee Camp’, 2012, http://www.key1948.org/about-us/history-of-aida-youth-center/

Aida Youth Center, ‘The Key of Return and Gate of Return’, 2012, http://www.key1948.org/the-key/

AlArabiya, ‘Palestinian ‘Key of Return’ on Show at Biennale’, YouTube, 10 May 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OE9JD1e8c0w

Amnesty International, ‘Israel and the Occupied Territories—Under the Rubble: House Demolition and Destruction of Land and Property’, 2004, http://www.amnesty.org/en/library/asset/MDE15/033/2004/en/2193fae2-d5f6-11dd-bb24-1fb85fe8fa05/mde150332004en.pdf

Anderson, B., Imagined Communities, Verso, London and New York, 2006.

Appleyard, D., ‘Home’, Architectural Association Quarterly, vol. 11, no. 2, 1979, pp. 4–20.

Badil, ‘About the Award’, 2010, http://www.badil.org/annual-al-awda-award/item/266-about-the-award

Badil, Survey of Palestinian Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons 2010–2012 Volume VII, Al-Ayyam, Bethlehem, 2012.

Badil, Israeli Land Grab and Forced Population Transfer of Palestinians: A Handbook for Vulnerable Individuals and Communities, Al-Ayyam, Bethlehem, 2013.

Ballantyne, A., What is Architecture? Routledge, London and New York, 2002.

Ben-Gurion, D., ‘The Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel’, 1948, http://www.knesset.gov.il/docs/eng/megilat_eng.htm

Bshara, K., ‘A Key and Beyond: Palestinian Memorabilia in the Economy of Resistance’, Working Paper Series, 2010, http://www.cgpacs.uci.edu/research/workingpapers.php

Colomina, B., ‘Domesticity at War’, Assemblage, no. 16, December 1991, pp. 14–41, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3171160

Davis, R., Palestinian Village Histories: Geographies of the Displaced, Stanford University Press, Stanford, California, 2011.

Douglas, M., ‘A Kind of Space’, in Home: A Place in the World, ed. A. Mack, special edition of Social Research, vol. 58, New York, 1991, pp. 287–307.

Dovey, K., ‘Home as an Ordering Principle in Space’, Landscape, vol. 22, 1978, pp. 27–30.

Dysch, M., ‘The Promise has an “Anti-Israel Premise”’, The Jewish Chronicle, 24 February 2011, http://www.thejc.com/news/uk-news/45709/the-promise-has-anti-israel-premise

Ellin, N. (ed.), Architecture of Fear, Princeton Architectural Press, New York, 1997.

Environment and Communications Committee, ‘14/02/2012—Estimates—Broadband, Communications And The Digital Economy Portfolio—Special Broadcasting Service Corporation’, 14 February 2012, http://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;db=COMMITTEES;id=committees%2Festimate%2F40e11b0a-2fbd-48e2-a290-a121fd0386bd%2F0010;query=Id%3A%22committees%2Festimate%2F40e11b0a-2fbd-48e2-a290-a121fd0386bd%2F0000%22

Halper, J., An Israeli in Palestine: Resisting Dispossession, Redeeming Israel, Pluto Press, New York, 2010.

Honig-Parnass, T., False Prophets of Peace: Liberal Zionism and the Struggle for Palestine, Haymarket Books, Chicago, 2011.

Human Rights Watch, ‘“I Lost Everything”: Israel’s Unlawful Destruction of Property during Operation Cast Lead’, 2010, http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/iopt0510webwcover_1.pdf

Human Rights Watch, ‘Separate and Unequal: Israel’s Discriminatory Treatment of Palestinians in the Occupied Palestinian Territories’, 2010, http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/iopt1210webwcover_0.pdf

ICAHD, ‘Obstacles to Peace: A Reframing of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict’, 2009, http://www.icahd.org/sites/default/files/Obstacles-2009.pdf

ICAHD, ‘Demolishing Homes, Demolishing Peace: Political and Normative Analysis of Israel’s Displacement Policy in the OPT’, 2012, http://www.icahd.org/sites/default/files/Demolishing%20Homes%20Demolishing%20Peace_1.pdf

Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs ‘Law of Return 5710–1950’, 2013 [1950], http://www.mfa.gov.il/mfa/mfa-archive/1950-1959/pages/law%20of%20return%205710-1950.aspx

Johnson, N., ‘Mapping Monuments: The Shaping of Public Space and Cultural Identities’, Visual Communication, vol. 1, 2002, pp. 293–8, http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/147035720200100302

Kosminsky, P. (dir.), The Promise. Daybreak Pictures, United Kingdom, 2011.

Kuperwasser, Y. and S. Lipner, ‘The Problem is Palestinian Rejectionism’, Foreign Affairs, vol. 90, no. 6, November–December 2011.

Levi, J., ‘SBS Rejects “The Promise” Complaint’, The Australian Jewish News, 2 February 2012, http://www.jewishnews.net.au/sbs-rejects-the-promise-complaint/24595

Morris, B., Righteous Victims: A History of the Zionist-Arab Conflict, 1881–2001, Vintage Books, New York, 2001.

National Nakba Commemoration Committee, ‘There is no Alternative to the Right of Return’, Electronic Intifada, 14 May 2008. https://electronicintifada.net/content/there-no-alternative-right-return/829

Netanyahu, B., ‘PM Netanyahu Speech at Bar Ilan University’, Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 6 October 2013, http://mfa.gov.il/MFA/PressRoom/2013/Pages/PM-Netanyahu-speech-at-Bar-Ilan-University-6-Oct-2013.aspx

Nora, P., ‘Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Memoire’, Representations, vol. 26, 1989, pp. 7–24. http://dx.doi.org/10.1525/rep.1989.26.1.99p0274v

Pappé, I., The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, Oneworld Publications, Oxford, 2006.

Porteous, J., Landscapes of the Mind, University of Toronto Press, Toronto, 1990.

Porteous, J. and S. Smith, Domicide: The Global Destruction of Home, McGill-Queen’s University Press, Montreal, 2001.

Rakoff, R., ‘Ideology in Everyday Life: The Meaning of the House’, Politics and Society, vol. 7, 1977, pp. 85–104. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/003232927700700104

Rees, R., ‘In a Strange Land … Homesick Pioneers on the Canadian Prairie’, Landscape, vol. 26, no. 3, 1982, pp. 1–9.

Reinhart, T., Israel / Palestine: How to End the War of 1948, Seven Stories Press, Canada, 2002.

Relph, E., Place and Placelessness, Pion, London, 1976.

Rosen, R., ‘Broadcast Regulator Rejects Every Complaint on Promise’, The Jewish Chronicle, 21 April 2011, http://www.thejc.com/news/uk-news/48120/broadcast-regulator-rejects-every-complaint-promise

Said, E., The Question of Palestine, Vintage Books, New York, 1992.

Shaw, S., ‘Returning Home’, Phenomenology & Pedagogy, vol. 8, 1990, pp. 224–36.

Stillman, L., ‘The Promise: Controversy Rages, Understanding Lost’, ABC The Drum, 17 January 2012, http://www.abc.net.au/news/2012-01-17/stillman-the-promise-controversy/3778466

Till, K., ‘Staging the Past: Landscape Designs, Cultural Identity and Erinnerungspolitik at Berlin’s Neue Wache’, Ecumene, vol. 6, 1991, pp. 251–83. http://dx.doi.org/10.1191/096746099701556277

Touq, T., ‘Key of Return: Probably the Biggest Key in the World’, Berlin Biennale, 2012, http://www.berlinbiennale.de/blog/en/projects/key-of-return-probably-the-biggest-key-in-the-world-19705

Tuan, Y.-F., ‘Geography, Phenomenology, and the Study of Human Nature’, Canadian Geographer, vol. 15, no. 3, 1971, pp. 181–92. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0064.1971.tb00156.x

UN OCHA, ‘East Jerusalem: Key Humanitarian Concerns’, 2011, http://www.ochaopt.org/documents/ocha_opt_jerusalem_report_2011_03_23_web_english.pdf

UN OCHA, ‘Gaza Crisis, 2014’ 2014, http://www.ochaopt.org/content.aspx?id=1010361

UN OCHA, ‘Occupied Palestinian Territory: Gaza Emergency—Situation Report (as of 4 September 2014, 08:00 hrs)’, 4 September 2014, http://www.ochaopt.org/documents/ocha_opt_sitrep_04_09_2014.pdf

Vidler, A., The Architectural Uncanny: Essays in the Modern Unhomely, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 1992.

Winchester, S., Outposts, Hodder and Stoughton, London, 1985.

Zochrot, ‘Who We Are’, 2014, http://zochrot.org/en/content/17

_________________

1 Ilan Pappé, The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, Oneworld Publications, Oxford, 2006; Benny Morris, Righteous Victims: A History of the Zionist-Arab Conflict, 1881–2001, Vintage Books, New York, 2001.

2 Rochelle Davis, Palestinian Village Histories: Geographies of the Displaced, Stanford University Press, Stanford, California, 2011, pp. 7, 235; Tikva Honig-Parnass, False Prophets of Peace: Liberal Zionism and the Struggle for Palestine, Haymarket Books, Chicago, 2011 pp. 2, 12; Tanya Reinhart, Israel / Palestine: How to End the War of 1948, Seven Stories Press, Canada, 2002, p. 52.

3 Palestinians assert that inhabitants were systematically expelled by force and through ‘psychological warfare’ to cultivate as large a Jewish majority as possible. Multiple massacres, including the Deir Yassin tragedy (where between 100 and 250 Arab villagers were murdered depending on the source), contributed to fear encouraging flight. In Pappé’s findings, depopulating Palestine was a clearly sanctioned objective. Plan D (Dalet) included a list of villages and neighbourhoods each unit was to dispose of via ‘large-scale intimidation; laying siege to and bombarding villages and population centres; setting fire to homes, properties and goods; expulsion; demolition; and, finally, planting mines among the rubble to prevent any of the expelled inhabitants from returning’. See Morris, pp. 207–9, 253; Pappé, pp. xii, 91.

6 For more information see Davis, p. 2; Pappé, pp. 230–1.

8 See Amnesty International, ‘Israel and the Occupied Territories—Under the Rubble: House Demolition and Destruction of Land and Property’, 2004, http://www.amnesty.org/en/library/asset/MDE15/033/2004/en/2193fae2-d5f6-11dd-bb24-1fb85fe8fa05/mde150332004en.pdf; Human Rights Watch, ‘“I Lost Everything”: Israel’s Unlawful Destruction of Property during Operation Cast Lead’, 2010, http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/iopt0510webwcover_1.pdf; Human Rights Watch, ‘Separate and Unequal: Israel’s Discriminatory Treatment of Palestinians in the Occupied Palestinian Territories’, 2010, http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/iopt1210webwcover_0.pdf; UN OCHA ‘East Jerusalem: Key Humanitarian Concerns’, 2011, http://www.ochaopt.org/documents/ocha_opt_jerusalem_report_2011_03_23_web_english.pdf; UN OCHA ‘Gaza Crisis, 2014, http://www.ochaopt.org/content.aspx?id=1010361; UN OCHA ‘Occupied Palestinian Territory: Gaza Emergency – Situation Report (as of 4 September 2014, 08:00 hrs)’, 4 September 2014, http://www.ochaopt.org/documents/ocha_opt_sitrep_04_09_2014.pdf.

9 See ICAHD, ‘Demolishing Homes, Demolishing Peace: Political and Normative Analysis of Israel’s Displacement Policy in the OPT’, 2012, http://www.icahd.org/sites/default/files/Demolishing%20Homes%20Demolishing%20Peace_1.pdf; Zochrot, ‘Who We Are’, 2014 http://zochrot.org/en/content/17; Badil, Survey of Palestinian Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons 2010–2012 Volume VII, Al-Ayyam, Bethlehem, 2012; Badil, Israeli Land Grab and Forced Population Transfer of Palestinians: A Handbook for Vulnerable Individuals and Communities, Al-Ayyam, Bethlehem, 2013.

10 The ‘Six Day War’ was a simultaneous assault launched by Israel on 5 June 1967 against the armies of Egypt, Syria and Jordan. By its conclusion on 10 June, Israel had conquered all of Egypt and Jordan’s 1947–48 gains (‘East’ Jerusalem, the West Bank and the Gaza Strip). The contours of the 1947–48 armistice lines thus became the Occupied Palestinian Territories. See Morris, pp. 316–29.

11 J. Douglas Porteous and Sandra E. Smith, Domicide: The Global Destruction of Home, McGill-Queen’s University Press, Montreal, 2001, p. 12.

14 Anthony Vidler, The Architectural Uncanny: Essays in the Modern Unhomely, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 1992, p. 7.

19 Andrew Ballantyne, What is Architecture? Routledge, London and New York, 2002, p. 16.

21 For more on this, see R. Rakoff, ‘Ideology in Everyday Life: The Meaning of the House’, Politics and Society, vol. 7, 1977, pp. 93–4; Donald Appleyard, ‘Home’, Architectural Association Quarterly, vol. 11, no. 2, 1979, p. 5.

24 For more on this, see Edward Relph, Place and Placelessness, Pion, London, 1976, pp. 39–40; Kim Dovey, ‘Home as an Ordering Principle in Space’, Landscape, no. 22, 1978, p. 28; Stephen Shaw, ‘Returning Home’, Phenomenology & Pedagogy, vol. 8, 1990, p. 227.

27 Nan Ellin (ed.), Architecture of Fear, Princeton Architectural Press, New York, 1997, p. 49.

28 See, in particular, Edward Blakely and Mary Snyder, ‘Divided We Fall: Gated and Walled Communities in the United States’, in Architecture of Fear, ed. Nan Ellin, Princeton Architectural Press, New York, 1997.

29 Beatriz Colomina, ‘Domesticity at War’, Assemblage, no. 16, December 1991, p. 20.

34 Khaldun Bshara, ‘A Key and Beyond: Palestinian Memorabilia in the Economy of Resistance’, Working Paper Series, 2010, http://www.cgpacs.uci.edu/research/workingpapers.php

35 S. Abu Salem, ‘“Key of Return”: A Marriage Gift in Gaza’, in Electronic Intifada, 15 May 2005 http://electronicintifada.net/content/key-return-marriage-gift-gaza/5588

36 AlArabiya, ‘Palestinian “Key of Return” on Show at Biennale’, YouTube, 10 May 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OE9JD1e8c0w

39 J. Douglas Porteous, Landscapes of the Mind, University of Toronto Press, Toronto, 1990, p. 141; Porteous and Smith, p. 57.

40 For more, see Porteous and Smith, p. 59; Ronald Rees, ‘In a Strange Land … Homesick Pioneers on the Canadian Prairie’, Landscape, vol. 26, no. 3, 1982, pp. 1–9, p. 1; Simon Winchester, Outposts: Journeys to the Surviving Relics of the British Empire, Hodder and Stoughton, London, 1985, p. 119.

41 Yi-Fu Tuan, ‘Geography, Phenomenology, and the Study of Human Nature’, Canadian Geographer, vol. 15, no. 3, 1971, p. 190.

42 Mary Douglas, ‘A Kind of Space’, in Home: A Place in the World, ed. Arien Mack, Special Edition of Social Research, New York, 1991, p. 294.

43 Jeff Halper, An Israeli in Palestine: Resisting Dispossession, Redeeming Israel, Pluto Press, New York, 2010, p. 53.

44 For more information see Halper, p. 53 and Morris pp. 256–7

45 Yosef Kuperwasser and Shalom Lipner, ‘The Problem is Palestinian Rejectionism’, Foreign Affairs, vol. 90, no. 6, November–December 2011, p. 4.

46 Benjamin Netanyahu, ‘PM Netanyahu speech at Bar Ilan University’, Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 6 October 2013, http://mfa.gov.il/MFA/PressRoom/2013/Pages/PM-Netanyahu-speech-at-Bar-Ilan-University-6-Oct-2013.aspx

47 Reinhart, pp. 51–2, 53–5; Kuperwasser and Lipner, p. 4.

48 Israel’s Declaration of Independence 1948: ‘Accordingly we, members of the People’s Council, representatives of the Jewish Community of Eretz-Israel and of the Zionist Movement, are here assembled on the day of the termination of the British Mandate over Eretz-Israel and, by virtue of our natural and historic right and on the strength of the resolution of the United Nations General Assembly, hereby declare the establishment of a Jewish state in Eretz-Israel, to be known as the State of Israel’ (emphasis added). Even in a paragraph seemingly embracing liberal democratic principles ‘irrespective of religion, race or sex’, there remains a blunt privileging of Jews in its first sentence: ‘The State of Israel will be open for Jewish immigration, and for the Ingathering of the Exiles …’ See David Ben-Gurion, ‘The Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel’, 1948, http://www.knesset.gov.il/docs/eng/megilat_eng.htm

The ‘Ingathering of the Exiles’ was formalised legally as the Law of Return 5710–1950 on 5 July 1950. This law grants immediate citizenship to Jewish immigrants, defined in Section 4.B as ‘a person who was born of a Jewish mother or has become converted to Judaism and who is not a member of another religion’. Such an exclusive immigration benefit aims to tip the state’s demographic balance even more favourably towards Jews. See Honig-Parnass, pp. 3, 5; Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, ‘Law of Return 5710–1950’, 2013 [1950], http://www.mfa.gov.il/mfa/mfa-archive/1950-1959/pages/law%20of%20return%205710-1950.aspx

49 Aida Youth Center, ‘History of Aida Refugee Camp’, 2012, http://www.key1948.org/about-us/history-of-aida-youth-center

50 Bshara, p. 4. The Separation Barrier: a wall of massive concrete slabs eight metres tall forming a noose around heavily built-up Palestinian population centres, leaving minimal space for expansion and slicing through fields, groves, roads, even neighbourhoods. The wall is propagated as a security measure–while acting as a unilateral means to permanently annex swathes of available land. See Amnesty International, pp. 2–3.

51 Aida Youth Center, ‘The Key of Return and Gate of Return’, 2012, http://www.key1948.org/the-key/

53 Nuala Johnson, ‘Mapping Monuments: The Shaping of Public Space and Cultural Identities’, Visual Communication, vol. 1, 2002, p. 293; Karen Till, ‘Staging the Past: Landscape Designs, Cultural Identity and Erinnerungspolitik at Berlin’s Neue Wache’, Ecumene, vol. 6, 1991, p. 254.

56 Bshara, p. 5; Aida Youth Center, ‘History of Aida Refugee Camp’.

57 Ameera, cited in Bshara, p. 7.

58 Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities, Verso, London and New York, 2006.

62 Pierre Nora, ‘Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Memoire’, Representations, vol. 26, 1989, pp. 7–25.

63 Aida Youth Center, ‘History of Aida Refugee Camp’; Toleen Touq, ‘Key of Return: Probably the Biggest Key in the World’, 2012, Berlin Biennale, http://www.berlinbiennale.de/blog/en/projects/key-of-return-probably-the-biggest-key-in-the-world-19705

65 Badil, ‘About the Award’, 2010, http://www.badil.org/annual-al-awda-award/item/266-about-the-award

67 National Nakba Commemoration Committee, ‘There is no Alternative to the Right of Return’, Electronic Intifada, 14 May 2008, https://electronicintifada.net/content/there-no-alternative-right-return/829

68 See www.badil.org; https://www.facebook.com/BADILCenter/?fref=ts

69 See ICAHD, ‘Obstacles to Peace: A Reframing of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict’, 2009, http://www.icahd.org/sites/default/files/Obstacles-2009.pdf

70 Environment and Communications Committee ‘14/02/2012—Estimates—Broadband, Communications And The Digital Economy Portfolio—Special Broadcasting Service Corporation’, 14 February 2012, http://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;db=COMMITTEES;id=committees%2Festimate%2F40e11b0a-2fbd-48e2-a290-a121fd0386bd%2F0010;query=Id%3A%22committees%2Festimate%2F40e11b0a-2fbd-48e2-a290-a121fd0386bd%2F0000%22.

71 Peter Kosminsky (dir.), The Promise, Daybreak Pictures, United Kingdom, 2011.

72 For more information see Joshua Levi, ‘SBS rejects “The Promise” Complaint’, The Australian Jewish News, 2 February 2012, http://www.jewishnews.net.au/sbs-rejects-the-promise-complaint/24595; Larry Stillman, ‘The Promise: Controversy Rages, Understanding Lost’, ABC The Drum, 17 January 2012, http://www.abc.net.au/news/2012-01-17/stillman-the-promise-controversy/3778466

73 Marcus Dysch, ‘The Promise has an ‘Anti-Israel Premise’’, The Jewish Chronicle, 24 February 2011, http://www.thejc.com/news/uk-news/45709/the-promise-has-anti-israel-premise

74 Robyn Rosen, ‘Broadcast Regulator Rejects Every Complaint on Promise’, The Jewish Chronicle, 21 April 2011, http://www.thejc.com/news/uk-news/48120/broadcast-regulator-rejects-every-complaint-promise

75 Edward Said, The Question of Palestine, Vintage Books, New York, 1992.