Cultural Studies Review, Vol. 24, No. 1, March 2018

ISSN 1837-8692 | Published by UTS ePRESS | http://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/journals/index.php/csrj/index

RESEARCH ARTICLE

In the Shadow of a Willow Tree: A Community Garden Experiment in Decolonising, Multispecies Research

Kate Wright

University of New England

Corresponding author: Kate Wright, School of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences, University of New England, Armidale NSW 2351 Australia. kwrigh33@une.edu.au

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5130/csr.v24i1.4700

Article History: Received 22/10/2015; Revised 21/11/2017; Accepted 07/02/2018; Published 20/20/2018

Citation: Wright, K. 2018. In the Shadow of a Willow Tree: A Community Garden Experiment in Decolonising, Multispecies Research. Cultural Studies Review, 24:1, 74-101. http://dx.doi.org/10.5130/csr.v24i1.4700

© 2018 by the author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Abstract

In 2014 I commenced a postdoctoral project that involved collaboratively planting and maintaining a community garden on a block of land that was once part of the East Armidale Aboriginal Reserve in the so-called New England Tableland region of New South Wales, Australia. At the edge of this block of land is an introduced, invasive willow tree. In this article I write with and alongside the willow tree to interrogate the potential and limitations of anticolonial projects undertaken from colonial subject positions predicated on relations of social and environmental privilege.

Anticolonial scholarly activism demands a critique of individual and institutional complicity with ongoing colonial power structures. The following analysis offers a personal narrative of what it has been like to be involved in an anticolonial multispecies research project while working within the confines of the neoliberal university. Exploring the intersection of academic, social and environmental ecologies, I position the community garden as an alternative pedagogical and public environmental humanities research site that interrupts the reproduction of settler colonial power relations by cultivating tactics of collective resistance in alliance with the nonhuman world.

Keywords

multispecies, decolonisation, community garden, education policy, activism

Gran planted it there with a little stick … it had a little stick. The willow grew big. Then it got struck with lightning. The limbs fell down but it was still growing, you know, still alive.

Uncle Richard Vale1

All growth is rhizomatic … a rhizome has neither a beginning nor end, but always a middle (milieu) from which it grows and from which it overspills.

Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari2

Figure 1 The willow tree that this article has been written around, through and with, Armidale Aboriginal Community Garden, 2015. Photograph: Kate Wright

I. Seeds

Willow trees, like all plants, germinate from seeds. Tenacious roots take hold in the elusive darkness of soils as stems and leaves shoot upward into light.

Like sentient and conscious subjects who always find themselves in the midst of something that has already begun outside the sphere of their memory and control, the plant is an elaboration on and from the midsection devoid of clear origin.3

Everything extends from the middle. Everything begins in the midst of something else.

—

The Australian landscape is a massive crime scene. Almost all places are stained with social and ecological violence and trauma. The aftershocks ripple through relational landscapes, producing what Joseph Pugliese calls ‘ecologies of obliteration and suffering’ and ‘geographies of dispossession’.4

In 2014, I began a postdoctoral project that involved labouring in one of these zones—collaboratively planting and maintaining a community garden on a block of land that was once part of the Aboriginal Reserve in my hometown of Armidale, New South Wales. At the edge of this community garden is a willow tree, and it grows in the space of a willow that has since been removed. The first willow was planted by a Dunghutti woman, Sara Archibald (nee Morris), who lived on the East Armidale Aboriginal Reserve in the mid twentieth century. Sara and her willow are remembered by her many descendants who still live on the old Reserve site, now known as ‘Narwan Village’.

Joseph Pugliese has written on the way nonhuman entities bespeak histories of dispossession, loss and trauma.5 In this article, I think with the new willow tree, and the ghost of the lost willow that it shadows, as a way of tackling some of the complexity of undertaking anticolonial activist research within colonial societies and ecologies.

Gary Lewis articulates the critical imperative of personal and systemic reflection for researchers involved in movements for social justice:

We, speaking from a settler activist standpoint, need to consider … how we are bound up within systems of colonialism. We must continue our ethical activist research work, maintaining embedded relationships, reflexivity and a commitment to resist oppression and domination, all aspects that resonate with Indigenous and anti-colonial articulations … We must recognise the persistence of colonialism in intersecting systems of oppression and domination and seek to include such an ethical understanding into our research practice. We must recognise ourselves as allies in solidarity with Indigenous and anti-colonial struggles, with the imperative to unsettle and decolonise within our own communities and selves. We must rethink our collaborations, our contexts, our privileges and our practices, and conceive of them ethically in anti-colonial terms as a process that is never complete.6

In keeping with a decolonising ethic of critical self-reflection and commitment to political action,7 this analysis reports on the experimental anticolonial research taking place at the Armidale Aboriginal Community Garden, alongside a personal narrative of what it has been like to tackle my own complicity with colonialism and dispossession while working as an ally to Aboriginal struggles for self-determination.

The idea of establishing a community garden at the old Reserve site was planted in my mind during a conversation with Anaiwan Elder, Uncle Steve Widders, in 2011. At the time, I was finishing a series of interviews with Elders who had shared with me intimate accounts of their childhood spent on the so-called ‘New England’ tablelands, which included fond recollections of community and family, alongside profoundly moving experiences of racism and dispossession. While I had read and learned about colonisation for many years, this situated account of trauma and the localised impact of dispossession in the region where I had spent the first eighteen years of my life called me into a new relationship of responsibility. As familiar landscapes from my childhood were writ strange by histories of violence I was forced to confront the deeply uncomfortable fact that my places of intimate habitation—the places where I grew to understand myself and the world—were scarred by a genocidal and ecocidal past.8

In my PhD, I had written about the importance of decolonising a homeplace, and had set about to theoretically engage in what Deborah Bird Rose has termed ‘recuperative work’, to acknowledge the violence of the past and commit to a non-violent future.9 When Uncle Steve Widders mentioned to me that he would like to begin a community garden at the old Reserve site as a place of healing and Aboriginal cultural revival, I saw an opportunity to put the more-than-human decolonisation I had been advocating in my PhD into practice. Inhabiting the ‘harshly situated presence’ of a settler Australian, commitment to decolonisation on home ground requires scrutiny of the colonial and neo-colonial systems with which I am entangled, and the violences with which I am complicit.10

Albert Memmi observed in The Colonizer and the Colonized that ‘it is not easy to escape mentally from a concrete situation, to refuse its ideology while continuing to live with its actual relationships’.11 In this article, I interrogate the process of acting from within the social relations and subject positions I seek to change in order to develop a clearer understanding of my complicity with institutional reproductions of colonial privilege and power, and begin to develop strategies to deploy that privilege to subversive, anticolonial ends.12

The Armidale Aboriginal Community Garden opened in May 2015 as a collaborative initiative between Uncle Steve Widders, myself and a committee of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal community members and organisational representatives. Since this time it has been running as an activist platform for Aboriginal reclamation and cultural revival, and my experimental postdoctoral research project is situated within the dynamic more-than-human community taking shape at the garden.

In the following pages, I position the community garden as an alternative pedagogical and public environmental humanities research site that interrupts the reproduction of settler colonial power relations by cultivating tactics of collective resistance in alliance with the nonhuman world. Taking Deleuze and Guattari’s instruction to ‘follow the plants’, I look to the willow tree that stands at the edge of our community garden to think through multispecies entanglements with power in settler colonial states, and begin to conceptualise strategies to develop decolonising collectives that subvert neo-colonial systems, institutions, and ways of thinking and being.13

II. Roots and rhizomes

Weeping willows produce extensive root systems that spread far beyond their canopies … The aggressive root systems … create a network of shallow roots that spread out from the tree in every direction. Weeping willows typically produce foliage that is between 45 and 70 feet wide at maturity with roots that can spread approximately 100 feet from the centre of the trunk of large specimens.14

The wisdom of the plants: even when they have roots, there is always an outside where they form a rhizome with something else—with the wind, an animal, human beings …

Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari15

Willows first began being planted in Australia soon after colonial invasion and settlement as an erosion control measure along waterways. In the all-too-familiar tale of colonial Australian agricultural blunders, willows are now regarded as one of Australia’s most destructive riparian and wetland weeds. These water-hungry plants send their large, tough roots into streams and creeks, choking waterways and eroding riverbeds. Willows are water and habitat thieves, implicated in the violent theft of Indigenous lands. As Alfred Crosby reminds us, colonisation was always a more-than-human enterprise.16

The willow at the edge of our community garden was born in the midst of ecological and social violence, and unwittingly continues it through its invasion of waterways and habitats. Yet the willow also marks a beloved childhood place and holds memories and ancestral ties. It is a site of nostalgia and trauma, both damaged and loved.

While the willow is entangled in an ecology of dispossession, its cultural position is by no means simple or settled, and the complexity of its relation to the community garden and to the people who lived on the East Armidale Aboriginal Reserve where the garden now grows helps me to ‘stay with the trouble’of what it means to work toward decolonisation in contested spaces.17

Uncle Richard Vale grew up on the East Armidale Aboriginal Reserve and now lives three houses down from our community garden. He walked with me from the garden to the willow tree, which is located on the block of land where his grandparents, Frank and Sara Archibald, once lived. As he shared his memories he called up a landscape, a house, a yard that was no longer present, but was clearly visible in his mind’s eye:

The Catholic Church built a house here for Gran and Grandfather, and we used to call it ‘the white house’ … there was a willow in the backyard. Gran put it in with a little stick … it had a little stick. The willow grew big. Then it got struck with lightning. The limbs fell down but it was still growing, you know, still alive.18

Uncle Richard Vale’s rather conventional and suburban memory of his grandmother planting a willow in her backyard says so much about life for Aboriginal people living on reserves and missions in the mid twentieth century. As he spoke gently and softly of times past, I heard in his words an echo of the assimilationist impact of Catholicism: the way the church helped Aboriginal people when no one else would, but did so with paternalistic charity and controI. I heard, too, of the ferocious spread of invasive nonhuman plants and animals through native ecologies. And I heard of the violent subjugation of dispossessed Aboriginal peoples to Western concepts of property—the illegal carving of a sovereign continent into rectangular blocks to be managed by colonial institutions.

Figure 2 Uncle Richard Vale sharing his memories with me, at the edge of the Armidale Aboriginal Community Garden, 2015. Photograph: Kate Wright

The ‘white house’ that the Catholic Church built for Frank and Sara Archibald was completed in January 1957. The local newspaper, The Armidale Express, reported that ‘Father Kelly said Frank Archibald owned the house but not the land’.19 In a colonial cartography of dispossession, Frank and Sara Archibald had been calculated out of their Country, and were now expected to be grateful to be charged £1 a week for a home established on stolen Aboriginal lands.

Frank Archibald was descended from the Gumbaynggirr nation and was also initiated as a Dunghutti man. He was born in a shack on the outskirts of Armidale in approximately 1885 to a Scottish father and a Gumbaynggirr mother—Emily. Historical records report that Archibald could speak seven Aboriginal languages and understood two others, while being fluent in English.20

Figure 3 Sara and Frank Archibald with Father F.I. Kelly, East Armidale Aboriginal Reserve. Source: Richard Vale, reproduced with permission

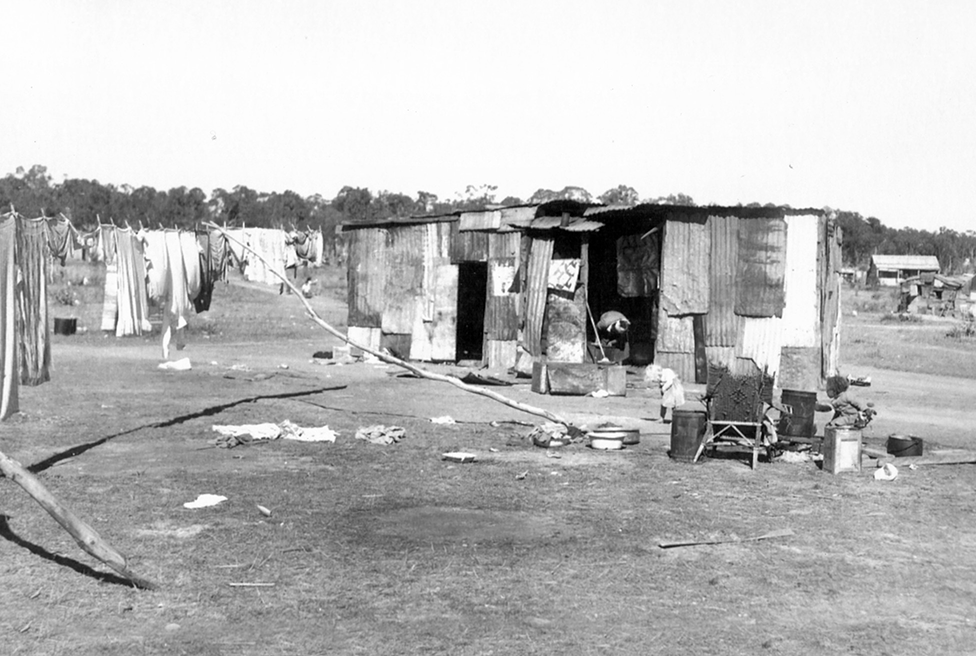

At the time that Father Kelly of the Catholic Church raised money and mobilised volunteers to build a house for Frank and Sara, the Archibalds had been living for a number of years, with their twelve children and other family members, in a tin humpy at the edge of the old Armidale rubbish dump.21 The people settling at this fringe camp had been violently dispossessed from their homelands following the great pastoral expansion of New South Wales in the 1830s. Margaret-Ann Franklin notes that by 1840 the non-Aboriginal population of the New England tablelands was almost double that of the Aboriginal population, and there were over five thousand sheep in the area.22

In the neo-colonial architecture of the Old Teachers’ College in Armidale, I read through archival records left by the Armidale Association for the Assimilation of Aborigines. They document the way an expanding colonial empire, and the violent practices of its institutions, transformed a sovereign people into fugitives in their own land. Having spent my childhood on a 35-acre block ostensibly ‘owned’ by my parents at the edge of this township, I was burdened by the uncomfortable awareness that I am implicated in the racialised geographies of colonisation that privileged me and my family with stolen ecological gifts while confining this continent’s first peoples to a rubbish dump.

The archival material states that Frank and Sara moved to the fringe-dwelling camp on the tip in Armidale after the local council bulldozed their humpy (just after Christmas, 1954) at Yarra Bay, near La Perouse in Sydney. They were followed by many relations. A few families had already settled at the camp, and by 1956 about one hundred dispossessed Aboriginal people were ‘living in poverty in hessian and corrugated iron humpies on the old superseded municipal dump’.23 A survey undertaken in 1961 by the Armidale Assocation for the Assimilation of Aborigines showed that of a total population of one hundred and fifteen, eighty-two were directly related to the Archibalds.24

Figure 4 Frank and Sara Archibald’s children, Leonard and Ethel De Silva, with their daughter, Barbara, and two other children, at the East Armidale Aboriginal Reserve. Source: Richard Vale, reproduced with permission

The Armidale fringe camp was declared a reserve in 1958, bringing it under the control of the Aboriginal Welfare Board. Under the jurisdiction of the board, reserves functioned as segregated paternalistic prisons. Inhabitants were denied freedom of movement, and ancestral languages and cultural practices, including hunting traditional foods, were banned.

In 1915 an amendment to the Aborigines Protection Act stated that any Aboriginal child could be removed from their family without consent, and without any involvement of the court, if the Aboriginal Protection Board (renamed the Welfare Board in 1940), considered it to be in the interest of the child’s moral or physical welfare.25 At a cultural immersion event held for university staff at the community garden, Uncle William (Bim) Widders remembered his own fear at the threat of being stolen from his family while living on the Reserve.

There was a protection board manager, cause of the Reserve. He always used to come down this road here [Bim points his finger toward what is now a bitumen street that runs beside our community garden]. The parents told us as soon as you see that white station wagon go away and hide. And we used to see the dust coming up here. You’d see all the kids just scatter. My hiding place was underneath the laundry … me and Ollie used to stand up in there and hide. We were terrified.26

Following Uncle Bim’s pointed finger, I looked toward the town where I had lived from the time I was born until I was eighteen years old. My primary school is about two hundred metres down the road that foreboding white station wagon used to drive along but I was never taught this history. I learned about the East Armidale Aboriginal Reserve for the first time during my PhD research in my mid twenties, and yet hearing Uncle Bim and other Elders speak, it seemed that the memories were immanent in the space, sedimented by the shared testimony of the Elders who had lived them.

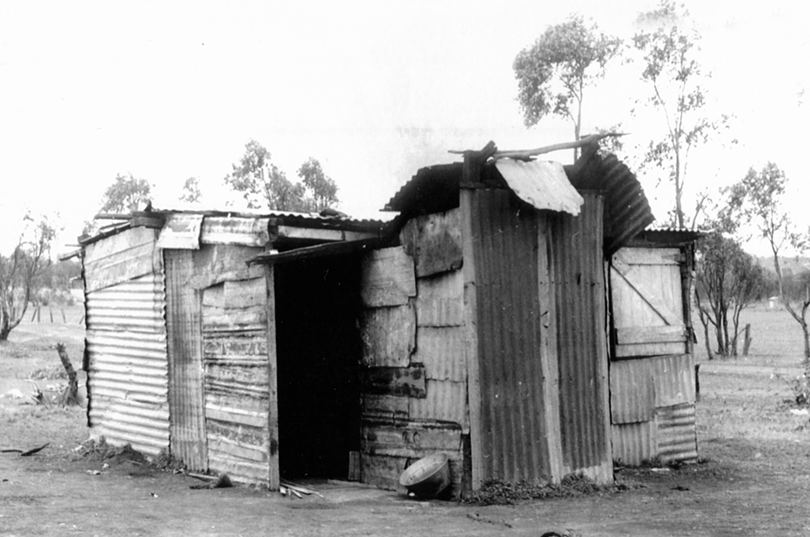

Figure 5 Tin humpy at the East Armidale Aboriginal Reserve. Source: Richard Vale, reproduced with permission

Uncle Richard Vale described his vivid childhood memories of the old Reserve site:

The real old houses were just tin, what they picked up from anywhere, and put hessian bags around, and cardboard boxes. Some had floorboards and some hard dirt ground—a floor of dirt. I remember those places real well.27

Memory is at the heart of decolonisation because the perceived legitimacy of settler colonial occupation of land and the denial of Aboriginal sovereignty depends on silence and amnesia. The land surrounding the Armidale Aboriginal Community Garden is immersed in more-than-human ecologies of colonisation, with histories of community, of violent dispossession, and of Aboriginal people’s resilience, sustained in place, and in the memories of the people who still inhabit that place.

Edward Casey argues that place is essential to the preservation of memory: ‘As much as body or brain, mind or language, place is a keeper of memory—one of the main ways by which the past comes to be secured in the present, held in things before and around us.’28 At the community garden, Elders have gathered together over a series of workshops to share some of the untold history of the East Armidale Aboriginal Reserve with university staff as part of a cultural immersion program, designed by University of New England Gomeroi academic Rob Waters and Kamilaroi academic Marcelle Burns. This emplaced survivor testimony is a form of ‘immanence-as-resistance’ that fights the settler colonial state’s ‘violent practices of occupation, erasure and colonial resignification’.29

Aunty Pat Cohen moved onto the Reserve when she was sixteen years old. As she shared her memories of the area with university staff, she initiated a decolonising process of ‘unforgetting’:30

Figure 6 Woman and child at East Armidale Aboriginal Reserve. Source: Richard Vale, reproduced with permission

Out here was one old lady and her two sons, and she had a shack over the back there. It was a rubbish dump, and the little shack was built in amongst the rubbish. And a bit further away was a couple living in a huge tank ... There was one tap amongst probably 80 people, and the toilets were just the old pan thing that they used to have ... At that time there was a lot of sickness going around, there was a terrible lot of deaths out that way. A lot of young kids were dying of diarrhoea—and older people. My mother’s husband was Nick White—he died of gastroenteritis—and at one stage I remember there was five young children died within a week from gastroenteritis out here.31

Ghassan Hage has observed the way colonisation functions as a ‘mode of rubbishing people’. He argues that rubbishing was the dominant mode of racial extermination in Australia:

Exterminating people by ‘rubbishing them’ is always less dramatic than when it is done through massacres. It is more like dumping a truck that one has destroyed somewhere on one’s property and letting it slowly rust, corrode and disintegrate.32

Traci Brynne Voyles coined the term ‘wastelanding’ in relation to Navajo lands to refer to the ways in which settlers, including missionaries, mining prospectors and settler governments, framed Indigenous landscapes as empty, or as spaces amenable to mineral and natural resource extraction and, ultimately, to the disposal of toxic wastes. As a result, wastelanding ‘rendered an environment and the bodies that inhabit it as pollutable’.33

The old Reserve site carries ecological memories of fatal neglect and wastelanding. Contaminated soils of the old dump hold remnants of asbestos and lead in their molecular structure, an archive of bio-mineral and geo-social traumas which remain largely unacknowledged in official histories. Deborah Bird Rose has written on the way connected ecologies of bio-social remembrance resist colonial attempts at annihilation: ‘Memory, place, dead bodies and genealogies hold the stories that tell the stories, that are not erased, that refuse erasure. Painful as they are, they also constitute relationships of moral responsibility, binding people into the country and the generations of their lives.’34

Sara Morris’s willow tree is a complex mnemonic in this environmental archive, telling tales of dispossession, resilience, assimilation, community, family and resistance. The willow tree is part of the colonial wasting project, an environmentally invasive species that destroys native life. Yet it also exceeds this designation in lived relation to Aboriginal peoples. As it evokes family, community and cultural connection, the willow speaks of a rhizomatic form of rootedness forged in a space designed to decimate Aboriginal roots.35

Deleuze and Guattari write that ‘to be rhizomorphous is to produce stems and filaments that seem to be roots, or better yet connect with them by penetrating the trunk, but put them to strange new uses’.36

Because colonisation was a multispecies invasion that mobilised the power of nonhuman lives to transform Aboriginal lands, many Aboriginal people have lived their lives within colonial ecologies: loving dogs and cats, remembering willow trees, and surviving on rabbits. Culture and community are not static; and like the willow still growing after being stripped of its branches by a lightning strike, the decimation of Aboriginal culture has been met with resilient growth.

Richard Vale lamented that a local school that now officially owns the land destroyed the original willow:

I asked them would they leave the willow tree in there, but one of them knocked it out. They mightn’t have told the workers. Otherwise they probably would have left it there because there was no reason to tear it down.37

About ten metres away from where the old willow was, another willow grows. While not the same willow Richard Vale remembers as a child, this willow is kin, and shadows the lost one. Seeing this one helps us remember the other.

Deleuze and Guattari write, ‘[a] rhizome may be broken, shattered at a given spot, but it will start up again on one of its old lines, or on new lines’.38

Richard Vale’s childhood memories connect synapses to living and growing botany, so that the new willow and the old remembered willow come to form essential components of what Gregory Bateson called an eco-mental system, and this system conveys resilience and survival.39 In the wasteland ecology of postcolonised Australia, Sara Morris’s removed willow tree, and its remaining neighbouring sister, evidences the ongoing slow violence40 of the colonial state, while also acting as an ‘elliptical blueprint’ that memorialises ‘what has been, what survives, and what must be restituted’41 to Aboriginal people.

But how does a willow tree think? How does it remember the trauma of the past?

Michael Marder says that ‘plants are the first material mediations between the concrete universality of the earth and the purely abstract ideal being of light’.42 Plants emerge from a subterranean rhizosphere, carrying in their bodies the thick-time of the soil communities that sustain them.43 If soils are toxic or depleted the past will manifest in the present through the suffering and dying of plants. Rubbing my fingers against the smooth veneer like leaves of the willow tree, I think too of the way plants hold the memory of light, the way photons soak into their chlorophyll pigment just as images soak into the emulsion of film. Memory is a materiality folded into their being, intimately connected to processes of photosynthesis. Light, life and the earth cannot be separated, and what phenomenally appears on plants’ botanical flesh circulates through rhizomatic, multispecies networks.

Figure 7 Willow branches in sunlight. Photograph: Kate Wright

Willows reproduce through a process of ecological and interspecies cross-pollination. Wind picks up the finely haired seeds and distribute them across land and waterways, while birds, bees and other insects also carry willow futures in their bodies as they move through the world. This interspecies collaboration is a form of what Isabelle Stengers terms ‘reciprocal capture’, a ‘dual process of identity construction’ where divergent desires come together to produce mutual benefit.44

Deleuze and Guattari observe that ‘the tree is filiation, but the rhizome is alliance, uniquely alliance’.45 I want to mobilise the ‘becoming-with’ and ‘reciprocal capture’ of this willow tree, in connection to both human communities and more-than-human communities, to develop a radicalised logic of relation which offers an alternative means of conceptualising multispecies ally work.

Cate Sandilands notes:

Plants complicate capitalist inhabitation. Despite their active participation in enabling certain projects of colonial globalisation (think most obviously of corn, cotton and coffee) the fit between plant and capitalist desire is always provisional, and this provisionality provides a space in which to think about plants as participants … in more resistant projects.46

Despite being an invasive and colonising plant, in rhizomatic relation to the Archibald’s and their families, and to the multispecies ecology in which it is immersed, Sara Morris’s willow reveals the space of excess that is present in any multiplicity, and which, via forms of decolonising becoming-with, can produce anticolonial entanglements that become networks of resistance.

Vivieros De Castro observes that ‘a becoming is a movement that deterritorialises the two terms of the relation it creates, by extracting them from the relations defining them in order to link them via a new “partial connection”’.47 A Deleuzian inflected, minoritarian concept of differentiation and becoming allows for divergence from, or deterritorialisation of, constructed anthropocentric and colonial identities. As Clare Land argues, ‘when non-Indigenous activists serve anti-Colonial interests, they manifest a subjectivity that refuses the colonial logic that rigidly treated people according to the ascribed categories of Indigenous and non-Indigenous’.48 This becoming does not entail cultural appropriation: an ally becoming-Indigenous or becoming-Aboriginal. Rather it is what Deleuze and Guattari might refer to as becoming-revolutionary, or becoming-minor; that is, the creative process of becoming different or diverging from the hegemonic forces of colonialism.49

The Australian colonial state has policed the difference between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal peoples with great violence. Racialised identity has become oppressively defined as ‘the difference that makes a difference’, and this has been made manifest in the ongoing harsh lived realities of Aboriginal peoples in this continent.50 The state construction of Aboriginal identity has been definitively arborescent with blood quantum measurements, assimilation policies, certificates of exemption, and continued emphasis on genealogies and bloodlines used to define Aboriginality from a position of external state control. In resistance to the political-legal construction of Aboriginal or Indigenous identity, Indigenous scholars across the globe emphasise practice-based concepts of identity that foreground the dynamic and interconnected nature of being Indigenous, which they argue is a subjectivity constituted in history, ceremony, language and land, with relationships or kinship networks at its core.51

If the self is not fixed, but continually iterated through a series of relational enactments with others, the Armidale Aboriginal Community Garden can be seen as a site of more-than-human becoming that works to produce rhizomatic alliances focused on common matters of concern.52 As I struggle to understand how, as a non-Aboriginal woman, I am both complicit with and working against interlinked colonial and capitalist systems, a framework of subjectivity that emphasises practice-based understandings of the self, grounded in ongoing differentiation and becoming, speaks to the transformative power of working collaboratively in anticolonial or discolonial ways.53 By dwelling in the nonhuman alterity within and around us, members of the Armidale Aboriginal Community Garden are cultivating a transversalisation of struggles against oppressive antihuman systems and weaving multispecies networks of resistance.

III. Weaving

Weaving is a strong tool to decolonise yourself. Not just learning the practice, and reviving that practice, but also everything that comes along with it … Decolonisation for me is a process that you go through individually, before you can do something that’s outside yourself. To think in a decolonised way, it is necessary for you to decolonise your own practice and dismantle all the colonial things that you’ve experienced or that you do … Being able to decolonise yourself is very important, but it’s a lifetime process … it’s an ongoing thing.

Gabi Briggs54

The Armidale Aboriginal Community Garden, sited on the old East Armidale Aboriginal Reserve, is bordered by a woven willow fence. The fence is made from recycled poplars from local urban river regeneration programs, where weedy willows are being removed to make space for native plants. Fifty years ago, residents on the Reserve were taking up the discarded trash of the colonisers to create shelter from Armidale’s bitter winters. I have been moved by stories of ingenuity and survival, of blankets woven from old hessian bags, and tin walls clad in insulating newspapers glued on with flour and water. In this pocket of wounded country,55 the fence recycles the form of an invasive species to mark a space for resistance and reclamation. Taking up the discards of more-than-human colonisation, the willow weaves introduced and invasive histories into hopeful, collaborative futures.

Through a material agency the fence weaves lives together. It speaks to the willow one hundred metres away, and the ghost of the willow planted by Sara Archibald over fifty years ago. This is an ongoing dialogue of colonisation and decolonisation, the ever-unfinished process of weaving and unravelling and re-weaving identity, community and self.

The community garden willow fence is not protective in the mode of exclusion or indemnification. It does not keep anyone out and does not provide security by creating an impenetrable physical wall. Instead, the woven willow branches convoke forces of place and multispecies community, weaving a space of togetherness through line and form. The fence is unfinished and ongoing, perpetually in process, as groups of young Aboriginal students and garden volunteers pick up poplars from the pile nearby and continue the weaving. People mentor and school one another in how to weave the fence and, in passing on the craft, volunteers offer newcomers a small apprenticeship modelled on almost-forgotten artisan knowledges of fence-making. This performative, creative and loose collaboration calls up a time when labour and production was not ruled by technocratic doctrines of efficiency.

Figure 8 Uncle Steve Widders at the Community Garden fence, woven of willow branches, 2015. Photograph: Kate Wright

The community garden also hosts Indigenous weaving workshops. Gabi Briggs, an Ambēyaŋ weaver who grew up in Armidale, returned from Melbourne in August 2015 to host a Lomandra grass weaving workshop for Aboriginal high school girls at the garden. Briggs explains that weaving is a decolonising practice that revives culture and ancestral connections to empower individuals and communities:

I think it’s just so incredibly beautiful and humbling that you’re … doing the same movements, you’re weaving the same thing—or weaving a product—that your people used for thousands of years … And you’re thinking, ‘Is this the mindset? Is this the state of being?’ and it’s not even ‘if’. You know that you are sharing the same experience as your ancestors thousands of years ago … and it’s just so powerful and so incredible to be in that moment. It makes me stronger, I know that for sure, culturally stronger, personally a lot stronger—my confidence, and how I navigate myself throughout this world. And it makes me want to be home, to be on Country, and to do this here.56

Isabelle Stengers writes: ‘Reviving a destroyed practice is not resurrecting the past “as it was” … Reclaiming is not about rediscovering a lost tradition but about reactivating it, that is, reinventing it in a different epoch, a devastated epoch.’57 A weaving circle can be understood as a ‘circle of protection’,58 convoking forces of culture, community, ancestral ties and the nonhuman world to strengthen resistance against colonialism. Stengers argues that performative resistance requires ‘relaying, the sharing of stories, experiences, and experiments of “healing”, of recovering and reactivating what has been destroyed—the practices liable to confer the power to feel and think and decide together what a situation is demanding’.59

Figure 9 High school students weaving the fence, 2015. Photograph: Kate Wright

Figure 10 High school girls weaving with Lomandra grass at Gabi Briggs’ weaving workshop, 2015. Photograph: Kate Wright

Like a weaving circle, the woven fence of the garden also demarcates a space for ‘tactics of togetherness’ that can facilitate a transversal struggle against settler colonialism and neoliberal exploitation of people and places.60

Natasha Myers has written that a garden ‘provides a stage for plants and people to perform their entangled powers’.61 The nonhuman world has been exploited by the logic of capital, which reduces wondrous living systems to their instrumental value. Val Plumwood has observed that human relationships with the nonhuman world often take the form of colonisation, and Karl Marx identified imperial expansion and exploitation as ‘the rosy dawn of the era of capitalist production’.62 In the contemporary world, capitalism and colonialism collude to exploit and subjugate nonhuman life. The living world is thus both a victim and an ally in the anti-colonial, anti-capitalist struggle against oppressive systems.

Audre Lorde once said that ‘the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house’.63 The tools that perpetuate social and environmental injustice are colonial and anthropocentric ways of thinking deeply inscribed into our language, our policies and our institutional structures. In its dynamic, intra-active becoming, the nonhuman world provides us with a subaltern language to think and speak with that is grounded in a logic of connection.64

The research transpiring at the Armidale Aboriginal Community Garden can be understood as a form of worlding—an experiment in the construction of a hybrid multispecies research community. In this mode, research is not about uncovering data as if they were established empirical facts waiting to be unearthed, but is instead a generative process of place making and self re-creation—one of invention rather than discovery.

Figure 11 Iwata, a living sculpture of an echidna made of soil and Lomandra grasses. She marks the entrance to the Armidale Aboriginal Community Garden, 2015. Photograph: Kate Wright

Sarah Wright et al. explain how, in open-ended, collaborative and emergent research projects, researchers’ very identities are at stake in processes of intra-active becoming:

Research encounters are uncertain, dynamic, and fragile sites of engagement, filled with improvised but knowing performances. ‘Researcher’, ‘co-researcher’, and ‘participant’ draw on identities that are fluid, flexible, and deployable, and that elude confinement into fixed categories or stereotypes. These encounters are not ‘knowable’ in the conventional sense; rather, they constitute the actual production of knowledge.65

In 2015, the community garden welcomed a new inhabitant, ‘Iwata’, a living sculpture of an echidna. Iwata is the Anaiwan name for echidna, and the echidna is one of the Anaiwan totems. The sculpture is the result of a community arts project in which local artist Jeremy Rudge worked with Aboriginal high school and primary school students to create an echidna with spikes that are made of Lomandra grasses (the same grasses used in Gabi Briggs’ weaving workshops), and a body that is composed of living soil—a multiplicity of minerals coalescing with organic fragments of the bodies of the living and the dead.

Iwata is ancient and immanent; she is ancestral but created by the young. She is alive, but she is not singular. She is a heaving multitemporal sea of becomings, and she is a focal point for visitors to the community garden to begin to encounter the incommensurate belonging of Aboriginal people to this land.

As a manifestation of connectivity and healing, Iwata articulates the more-than-human alliances that are forming in the community garden, and works to subjectify grasses, soils and plants as part of an insurgent instrument to resist reductive and extractive approaches to the living world.

Hugo Reinart argues that research methods choreograph reality, ‘predetermining the scope of what can exist, dictating what can be discovered and how, and enlisting researchers in reproduction of certain dominant ontological coordinates’.66 Reinart observes that multispecies methodologies experiment with ‘novel assemblages of form, bodies, and technique to generate new forms of knowledge’ with insurrectionary potential.67

While the University of New England has created the possibility for this collaborative community research project, the community garden is also a site for revolutionary ways of thinking and being that are in direct opposition to increasingly corporatised university structures. It is thus an example of what George E. Marcus terms a ‘para-site’: ‘a site of alternativity in which anything, or at least something different, could happen’.68

With universities increasingly pressured to function as risk-averse, neoliberal entities, there is an urgent need to establish alternative sites of learning and transformation that might provide the possibility of thinking and acting differently. Akwugo Emejulu argues that ‘[u]niversities are contradictory spaces. They govern knowledge through hierarchies of control whilst simultaneously providing temporary and contingent spaces to think within and beyond themselves.’69 The community garden can be understood as a complex doubling of the university environment, where the research taking place on-site but off-campus subverts the neoliberalisation of knowledge construction while providing opportunities for the deterritorialisation and decolonisation of research methodologies and researchers’ subjectivities.

From the beginning of my postdoctoral project, I have struggled with how to resist and redress my complicity with colonialism and what Tess Lea has termed ‘the state within the self’.70 I have battled with ‘the contradiction between living comfortably in the system and being an agent for changing it’.71 Para-sites, writes Marcus, ‘facilitate alternative thinking by subjects who are deeply complicit with and implicated in powerful institutional processes in times of heightened consciousness of great social transformations’.72 While decolonising encounters at the community garden have offered what Elizabeth Povinelli has described as a means of pulling away, ‘a way of being out of the grip’73 of colonising modes, the discordance between on the ground, community-based research and the practices of the corporate university have produced acute, and illuminating, tensions and dilemmas in my research process and the way I engage with community.

Decolonising research collaborations require that the researcher adopt an open stance where they are vulnerable to transformative encounter. Environmental philosopher, Deborah Bird Rose, explains:

To be open is to hold one’s self available to others: one takes risks and becomes vulnerable. But this is also a fertile stance: one’s own ground can become destabilised. In open dialogue one holds one’s self available to be surprised, to be challenged, to be changed.74

Affect is at the heart of decolonisation because embodied responses to social and environmental injustice enact a visceral critique of a lifetime of colonial conditioning. During my PhD research, when I first heard Elders speak of growing up on reserves, hiding from government agencies so they wouldn’t be stolen as children, in the area of my hometown, my physical response, my profoundly affected body, commanded me into a relationship of responsibility. I felt for the first time that I had lived my life on stolen land. I had known that for a long time, but I felt it that day. Affect, vulnerability, self-reflection through risky encounters with a deeply uncomfortable situation, places the self at stake in social and political critique.

The research practices of universities are often founded on the fallacious premise that proximity leads to harm, but my experience has been that ethical community work requires individuals to get close, be vulnerable, take risks, and make mistakes in order to feel, and be propelled to act on, injustices.75

Risk aversion plagues many contemporary institutions, including universities, which are increasingly behaving as corporate entities subject to the desires of the market place. Under a neoliberal framework of global corporate culture, community relationships are often reduced to ‘brand management’, where engagement with the public is not so much about building reciprocal and trusting relationships, but managing public perceptions.

The position of being an early career researcher attempting to do on-the- ground decolonising work, while ‘managing’ the community’s perception of the university brand, is deeply uncomfortable and paradoxical. My dependence on my employer for project funding and a salary has often left me shying away from, rather than staying with, the trouble.

Furthermore, the protective characteristics of institutional indemnification and its externalisation of responsibility can eschew unpleasant affects that derive from vulnerability: fear, anxiety, shock and insecurity. Yet many scholars have recognised that discomfort is vital to the decolonising process, and for non-Aboriginal supporters to engage ethically with Aboriginal struggles, they must locate themselves in situations where they can be challenged and held accountable for their actions.76

University ethics processes purport to provide an avenue for research subjects, or communities, to complain if they deem any research practice to be unethical, but the ethics policy leaves little room for genuine and ongoing negotiation with Aboriginal communities, and does not engage with cultural protocols that might actually contradict university practices and principles. I have felt deeply compromised asking Elders to signal their support for my research project with signatures on complex documents based on protocols that have not emerged from community consultation (in terms of conversations with the particular people I am working with), but have been dictated in advance by university committees applying pre-existing guidelines.77 These litigious documents are incapable of making space for improvisational encounter in performative research practice, as only certain interactions are licensed by the ethics policy.78 The demand to be able to forecast the anticipated outcomes of a research project and align them with metrics for grant funding is also antithetical to open-ended research methods that are attempting to imagine different, minoritarian ways of producing knowledge.

Robyn Ferrell notes that ‘to know at the outset [of a research project] what one will find is not a priority of theoretical research, but of risk management’.79 Risk management requires that one projectively imagine the future, build a schematic model of the world based on that imagined future, and put measures in place to minimise encounters and occurrences that threaten the delivery of pre-ordained research outcomes. Risk management requires the kind of alienated symbolic and projective thinking that will pre-emptively frame the kinds of encounters that take place, and delimit connections by building a representation of the world modelled on the world one inhabits, but not necessarily responsive to the actual world. That is, risk management may diminish our capacity to think with the worlds and communities we are engaging with, because it responds to the map, but the map is not the territory.

Gregory Bateson differentiated the living world (creatura) from the world of forces (pleroma), noting that in the living world difference is a cause, rather than forces and impacts.80 The ‘difference that makes a difference’81 is the information that is transcribed on the map of reality that we draw—the distinctions that each creature deems important. Robert E. Ulanowicz, reflecting on Bateson’s work, writes:

A healthy ecosystem must always retain a modicum of inefficient, incoherent and disorganised repertoires that could be implemented in the face of novel perturbation to generate an effective response to the threat … Any system that is so finely honed in its performance so as to exclude too much such insurance is doomed to extinction.82

Pre-emptively conditioning risk to delimit vulnerability is a conditioning of our exposure to difference. Tightly clutching our map, we may be unable to adequately respond to the territory—to the world in its dynamic becoming. ‘Latent difference’ will be neglected, tuned out as noise, weeded from the margins of research questions and engagements. This is a significant problem, because ‘noise [is] the only possible source of new patterns’.83

A conditioning of difference presents blockages to the becomings that enable new decolonised modes of thinking attuned to the radical worldings of a living and lively world. This also threatens to prevent us from responding to difference and multiplicity within the self, as far as it is understood as a series of enactments with others.

Just as Uncle Richard Vale’s memories are held in willow trees as part of an eco-mental system, his cognition distributed across the landscape of his youth, so, too, the self is dispersed and multiplicitous. The individual, while nested in a bed of relations, and having an integrity of self, is also what Deleuze and Guattari term a ‘body without organs’, a ‘pure multiplicity of immanence’.84 John Scannell, via Deleuze, observes that there is no essential self, only difference, and enactments with others invoke the constructed ‘I’ of identity performance, and can contribute to ‘recognition of its actual ongoing difference’.85 Encounter with the Other is thus an encounter with self-alterity, an exchange of difference that mobilises centripetal and centrifugal forces of self. Blockages to this process of ravelling and unravelling threaten to trap us in the death masks of neo-colonial identities, and prevent us from even imagining how things might be done differently.

Donna Haraway implores people to look beyond alienating corporate systems to ‘think the world we are actually living’ and the worldings we are engaged in.86 The amnesiac, fragmenting practices of settler colonialism blind us to our complicity in ongoing colonial violence—in maintaining the status quo of white privilege and racialised control and oppression. The liberal settler state also blinds us to lines of flight—to the openings into what Ghassan Hage terms ‘minor realities’, operating at the periphery of the colonial world. Hage writes:

We have increasingly come to see instrumental reason and the reality associated with it as the only possible mode of being and the only possible mode of reasoning. In this sense, rather than instrumental reason as such, Western modernity’s greatest ‘achievement’ has been to make us mono-realists, minimising our awareness of the multiplicity of realities in which we exist.87

Deleuze and Guattari write that they watched lines of flight migrate ‘like columns of tiny ants’.88 But ants aren’t just metaphors to be used by lyrical philosophers; they are agents in the world’s ongoing differentiation and becoming. At the Armidale Aboriginal Community Garden, ants, birds, bees, butterflies, the rhizomatic and multiplicitous underworld of soils, the rabbits that dig up the vegetables, the crows that fly overhead, all manifest pathways into rhizomes, other worlds, other ways of being. Just as Sara Morris’s willow exceeds its eco-political designation as an invasive coloniser, plants and animals in our community garden, both the native and the introduced, ‘keep the place moving, subverting and rearranging the institutional relations that brought them here’.89 It is not only intentional strategies of resistance—cultural revival practices, survivor testimony, public remembering—that come to matter, to be the difference that makes a difference, but also the incidental, uncontrollable, and largely unknowable agency of the living and lively world.

Figure 12 Minimbah preschool student Leroy Fernando encountering a goat at the Armidale Aboriginal Community Garden, 2016. Photograph: Kate Wright

If, as activists and scholars have observed, humility is at the heart of decolonising work, part of that humility in a multispecies project is to accept, embrace and revel in the fact that humans are not the only researchers, and that Country and its inhabitants have their own research agendas and desires.90

The community garden is a multiplicity, a heterotopia. Dwelling in its rhizomatic, more-than-human alterity is a way of activating the alterity within ourselves. In this space ‘being other than what we are is not just conceptually possible. It is materially possible’91 because we make decisions and act from within an ecology sustained by difference without erasure, where minor realities flicker like fireflies at the periphery of colonial consciousness.

Michael Marder, reflecting on the way plants think, writes of a mode of thought that ‘takes place in the interconnections between the nodes, in the lines of flight across which differences are communicated and shared, the lines leading these nodal points out of themselves, beyond the fictitious enclosure of reified and self-sufficient identity’.92 Marder’s vision of thought is not an internal process of anthropocentric, instrumental reason, but a dynamic and multispecies assemblage, fundamentally contextualised and embedded in place. In this context of radical exposure and multiplicity, ‘the question is not who or what thinks’, but ‘when and where does thinking happen?’93 Marder envisions this rhizomatic mind as a place where ‘thoughts and discernments are not stored in the interiority of consciousness … but circulate on the surface and keep close to the phenomenal appearance of things’.94

Figure 13 Myrmecia ant in the soils of the community garden, 2014. Photograph: Kate Wright

Moving beyond the neural and symbolic limits of cognition to look at other processes of differentiation, dynamism and relationality in the community garden, we can understand thought as immanent, collective, affective, circulating through bodies in contact with one another.

The fissures between the firing synapses are the spaces between the insect and the pollen. The air is thick with propositions deeply scented by the erotic aromas that beckon bees and butterflies to flowers.95 Beneath the soils a rhizomatic underworld of roots and microorganisms buzzes with life. If you follow ants into their tunnels you might find yourself entering this subterranean world from a newly formed neural pathway.

Isabelle Stengers writes that ‘struggling against Gaia makes no sense—it is a matter of learning to compose with her. Composing with capitalism makes no sense—it is a matter of struggling against its stronghold’.96

At the Armidale Aboriginal Community Garden, the articulations of the more-than-human world rise up as an incantation against the capitalist and colonial silencing of voices of resistance. This multispecies language has been collecting and collective for hundreds of thousands of years of coevolution, like the voice of the sea that lingers in a shell. It is a minoritarian way of speaking, thinking and connecting that is patterned through the world we move in, and if we think and compose with it, we compose with the great patterns of life. It is punctuated with a grammar that does not block, but creates the conditions for, new thought—the hyphen connects one body to another, the ellipses make space for lines of flight …

About the author

Kate Wright is a postdoctoral research fellow at the University of New England, Armidale, where her research focuses on the role played by more-than-human communities in working toward social and environmental justice, with a particular emphasis on decolonisation in Australia. Her current project is a collaboration with Armidale’s Aboriginal community to develop and maintain a community garden at the old East Armidale Aboriginal Reserve site as an activist platform for Aboriginal reclamation and cultural revival. Her publications include Transdisciplinary Journeys in the Anthropocene: More-than-human Encounters (2017) and she is co-editor of the Living Lexicon section of Environmental Humanities.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge and thank Uncle Richard Vale, Uncle Steve Widders, Uncle Bim Widders, Aunty Pat Cohen and Gabi Briggs for generously sharing their thoughts and memories with me.

Bibliography

Alfred, T. and J. Corntassel, ‘Being Indigenous: Resurgences against Contemporary Colonialism’, Government and Opposition, vol. 40, no. 4, 2005, pp. 597–614. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-7053.2005.00166.x

Anderson, K., A Recognition of Being: Reconstructing Native Womanhood, Sumach Press, Toronto, 2000.

Barad, K., Meeting the Universe Halfway, Duke University Press, Durham and London, 2007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1215/9780822388128.

Bateson, G., Steps to an Ecology of Mind, Chandler Publishing, San Francisco, 1972. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226924601.001.0001

Bateson, G., Mind and Nature: A Necessary Unity, E.P. Dutton, New York, 1979. https://doi.org/10.2307/2906578

Casey, E.S., Remembering: A Phenomenological Study, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 2000.

Crosby, A.W., Ecological Imperialism: The Biological Expansion of Europe, 900–1900, 2nd edn, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2004. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0025727300047062

Deleuze, G. and F. Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 1987. https://doi.org/10.2307/203963

Emejulu, A., ‘The University is Not Innocent: Speaking of Universities’, Verso Books Blog, 2017, <https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/3148-the-university-is-not-innocent-speaking-of-universities>.

Frankenburg, R., White Women, Race Matters: The Social Construction of Whiteness, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 1993. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203973431

Franklin, M-A., Assimilation in Action: The Armidale Story, University of New England Press, Armidale, 1995.

Garbutt, R., S. Biermann and B. Offord, ‘Into the Borderlands: Unruly Pedagogy, Tactile Theory and the Decolonising Nation’, Critical Arts, vol. 26, no. 1, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2012.663160

Hage, G., ‘Dwelling in the Reality of Utopian Thought’, Traditional Dwellings and Settlement Review, vol. 1, no. 23, 2011.

Hage, G., Alter-Politics: Critical Anthropology and the Radical Imagination, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-8676.12382

Haraway, D. ‘Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Chthulucene: Staying with the Trouble’, paper presented at Anthropocene: Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet, Santa Cruz, California May 8-10, 2014, available at: https://vimeo.com/97663518.

Haraway, D., Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Cthulucene, Duke University Press, London, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1111/amet.12570

Holm, T.J., D. Pearson and B. Chavis, ‘Peoplehood: A Model for American Indian Sovereignty in Education’, Wicazo Sa Review, no. 18, 2003, pp. 7–24. https://doi.org/10.1353/wic.2003.0004

‘House for Aborigines Seen as Successful Community Project’, Armidale Express, 23 January 1957, p. 6.

Land, C., Decolonizing Solidarity: Dilemmas and Directions for Supporters of Indigenous Struggles, Zed Books, London, 2015. https://doi.org/10.7202/1038616ar

Latour, B., ‘Why Has Critique Run Out of Steam? From Matters of Fact to Matters of Concern’, Critical Inquiry, no. 30, 2004, pp. 225–48. https://doi.org/10.2307/1344358

Latour, B., ‘How to Talk about the Body? The Normative Dimensions of Science Studies’, Body and Society, vol. 10, no. 2, 2004, pp. 205–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357034x04042943

Lea, T., Bureaucrats and Bleeding Hearts: Indigenous Health in Northern Australia, UNSW Press, Sydney, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1375/s1326011100000703

Lewis, G., ‘Ethics, Activism and the Anti-Colonial: Social Movement Research as Resistance’, Social Movement Studies: Journal of Social, Cultural and Political Protest, vol. 11, no. 2, 2012, pp. 227–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2012.664903

Lorde, A., ‘The Masters Tools Will Never Dismantle the Masters House’, in Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches, Crossing Press, Berkeley, 2007 [1984], pp. 110–14.

Marcus, G.E. (ed.), Para-Sites: A Casebook Against Cynical Reason, University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London, 2000.

Marder, M., Plant-Thinking: A Philosophy of Vegetal Life, Columbia University Press, New York, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0012217313001029

Marx, K., Capital: A Critique of Political Economy Vol. 1, chapter 31, https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1867-c1/ch31.htm [1865].

Memmi, A., The Colonizer and the Colonized, Orion Press, New York, 1965. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0003055400136238

Muecke, S., ‘The Mother’s Day Protest’, in S. Muecke, The Mother’s Day Protest and Other Fictocritical Essays, Rowman and Littlefield, London, 2016.

Myers, N., ‘From the Anthropocene to the Planthroposcene: Designing Gardens for Plant/People Involution’, History and Anthropology, vol. 28, no. 3, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1080/02757206.2017.1289934

Neimanis, A. and S. Walker, ‘Weathering: Climate Change and the “Thick Time” of Transcorporeality’, Hypatia, vol. 29, no. 3, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1111/hypa.12064

Nixon, R., Slow Violence and Environmentalism of the Poor, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309133311431670

Patton, P., ‘Difference and Politics’, in The Deleuze Dictionary, revised edn, ed. Adrian Parr, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, 2005.

Pignarre, P. and I. Stengers, Capitalist Sorcery: Breaking the Spell, trans. Andrew Goffey, Palgrave Macmillan, Hampshire and New York, 2011. https://doi.org/10.5840/symposium201216239

Plumwood, V., ‘Decolonising Relationships with Nature’, Philosophy, Activism, Nature, vol. 2, 2002, pp. 7–30.

Povinelli, E., The Empire of Love: Toward a Theory of Intimacy, Genealogy and Carnality, Duke University Press, Durham and London, 2000.

Pugliese, J., ‘Forensic Ecologies of Occupied Zones and Geographies of Dispossession: Gaza and Occupied East Jerusalem’, Borderlands, vol. 14, no. 1, 2015.

Read, P., ‘The Stolen Generations: The Removal of Aboriginal Children in New South Wales 1883–1969’, 2006 (fourth rpr, originally published 1981), https://daa.asn.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Reading-7_StolenGenerations.pdf.

Reinart, H., ‘About a Stone: Some Notes on Geologic Conviviality’, Environmental Humanities, vol. 8, no. 1. https://doi.org/10.1215/22011919-3527740

Rose, D.B., Reports from a Wild Country: Ethics for Decolonisation, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2004. https://doi.org/10.1177/1030570x0601900320

Sandilands, C., ‘Plantasm: Vegetal Participation and Imagination’, paper presented at Participatory Environmental Humanities conference, University of New South Wales, July 2017.

Scannell, J., ‘Education: The Subjectivising Power of the Performative’, Somatechnics, vol. 4, no. 2, 2014. https://doi.org/10.3366/soma.2014.0134

Stengers, I., Cosmopolitics I, trans. R. Bononno, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1086/671744

Stengers, I., In Catastrophic Times: Resisting the Coming Barbarism, trans. A. Goffey, Open Humanities Press in collaboration with Meson Press, London, 2015, http://openhumanitiespress.org/books/download/Stengers_2015_In-Catastrophic -Times.pdf.

Stengers, I., ‘Autonomy and the Intrusion of Gaia’, South Atlantic Quarterly, vol. 116, no. 2, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1215/00382876-3829467

Thompson, D., ‘The Root System of a Weeping Willow’, SF Gate Home Guides, http://homeguides.sfgate.com/root-system-weeping-willow-51554.html.

Ulanowicz, R.E., ‘Process Ecology: Creatura in an Open Universe’, in A Legacy for Living Systems: Gregory Bateson as Precursor to Biosemiotics, ed. J. Hoffmeyer, Springer, Dordrecht, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-6706-8_8

Viveiros de Castro, E., Cannibal Metaphysics, ed. and trans. P. Skafish, Univocal Publishing, Minneapolis, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474016643977

Voyles, T.B., Wastelanding: Legacis of Uranium Mining in Navajo Country, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 2015.

Whelan, A. and M. McLelland, ‘Management of Risk of Harm as Governing Logic’, paper presented at Cultural Studies Association of Australasia conference, 5 December 2015.

Wright, K., Transdiciplinary Journeys in the Anthropocene: More than Human Encounters, Routledge, Oxford and New York, 2017. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315692975

Wright, S., K. Lloyd, S. Suchet-Pearson, L. Burarrwanga, M. Tofa and Bawaka Country, ‘Telling Stories in, through and with Country: Engaging with Indigenous and More-than-Human Methodologies at Bawaka, NE Australia’, Journal for Cultural Geography, vol. 29, no.1, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1080/08873631.2012.646890

Notes

1. Richard Vale, personal communication, 18 September 2015.

2. Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 1987, p. 672.

3. Michael Marder, Plant-Thinking: A Philosophy of Vegetal Life, Columbia University Press, New York, 2013, p. 63.

4. Joseph Pugliese, ‘Forensic Ecologies of Occupied Zones and Geographies of Dispossession: Gaza and Occupied East Jerusalem’, Borderlands, vol. 14, no. 1, 2015, pp. 13, 1.

6. Gary Lewis, ‘Ethics, Activism and the Anti-Colonial: Social Movement Research as Resistance’, Social Movement Studies: Journal of Social, Cultural and Political Protest, vol. 11, no. 2, 2012, pp. 227–40.

7. Clare Land, Decolonizing Solidarity: Dilemmas and Directions for Supporters of Indigenous Struggles, Zed Books, London, 2015, p. 200.

8. Sections of these interviews, and an account of this decolonising experience, are published in my recent monograph Transdiciplinary Journeys in the Anthropocene: More than Human Encounters, Routledge, Oxford and New York, 2017.

9. Deborah Bird Rose, Reports from a Wild Country: Ethics for Decolonisation, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2004.

11. Albert Memmi, The Colonizer and the Colonized, Orion Press, New York, 1965, p. 20.

12. Ruth Frankenburg, White Women, Race Matters: The Social Construction of Whiteness, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 1993, p. 5.

13. Deleuze and Guattari, p. 11.

14. Daniel Thompson, ‘The Root System of a Weeping Willow’, SF Gate Home Guides, http://homeguides.sfgate.com/root-system-weeping-willow-51554.html.

15. Deleuze and Guattari, p. 12.

16. Alfred W. Crosby has made the persuasive argument that the invasion of Australia, and other ‘neo-European’ countries, was, necessarily, more-than-human. Crosby charts the historical partnership between human European colonisers in Indigenous lands and the ‘grunting, lowing, neighing, crowing, chirping, snarling, buzzing, self-replicating and world-altering avalanche’ of introduced life that they brought with them. Alfred W. Crosby, Ecological Imperialism: The Biological Expansion of Europe, 900–1900, 2nd edn, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2004, p. 194.

17. Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Cthulucene, Duke University Press, London, 2016.

18. Richard Vale, personal communication, 18 September 2015.

19. ‘House for Aborigines Seen as Successful Community Project’, Armidale Express, 23 January 1957, p. 6.

20. Margaret-Ann Franklin, Assimilation in Action: The Armidale Story, University of New England Press, Armidale, 1995, p. 16.

25. Peter Read, ‘The Stolen Generations: The Removal of Aboriginal Children in New South Wales 1883–1969’, 2006 (fourth rpr, originally published 1981), p. 8, https://daa.asn.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Reading-7_StolenGenerations.pdf.

26. William Widders, Cultural Immersion discussion at Armidale Aboriginal Community Garden, 11 September 2015.

27. Richard Vale, personal communication, 18 September 2015.

28. Edward S. Casey, Remembering: A Phenomenological Study, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 2000, p. 213.

30. Rob Garbutt, Soenke Biermann and Baden Offord, ‘Into the Borderlands: Unruly Pedagogy, Tactile Theory and the Decolonising Nation’, Critical Arts, vol. 26, no. 1, 2012, p. 68.

31. Pat Cohen, Cultural Immersion discussion at Armidale Aboriginal Community Garden, 11 September 2015.

32. Ghassan Hage, Alter-Politics: Critical Anthropology and the Radical Imagination, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2015.

33. Traci Brynne Voyles, Wastelanding: Legacis of Uranium Mining in Navajo Country, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 2015, p. 9.

35. Ghassan Hage conceptualises a rhizomatic form of rootedness as an ‘open, non-exclusivist, rootedness that allows for a superposed multiplicity of roots’ in Alter-Politics.

36. Deleuze and Guattari, p. 17.

37. Richard Vale, personal communication, 18 September 2015.

38. Deleuze and Guattari, p. 7.

39. Gregory Bateson, Steps to an Ecology of Mind, Chandler Publishing, San Francisco, p. 492.

40. Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and Environmentalism of the Poor, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 2011.

43. Astrida Neimanis and Stephanie Walker use the term ‘thick time’ to articulate the way ‘matter has a memory of the past, and this memory swells as it creates and unmakes possible futures’ in ‘Weathering: Climate Change and the “Thick Time” of Transcorporeality’, Hypatia, vol. 29, no. 3, 2013, p. 571.

44. Isabelle Stengers, Cosmopolitics I, trans. Robert Bononno, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 2010, p. 36.

45. Deleuze and Guattari, p. 27.

46. Cate Sandilands, ‘Plantasm: Vegetal Participation and Imagination’, paper presented at Participatory Environmental Humanities conference, University of New South Wales, July 2017.

47. Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, Cannibal Metaphysics, ed. and trans. Peter Skafish, Univocal Publishing, Minneapolis, 2014, p. 160.

49. Paul Patton explains, ‘in order to draw attention to the sense in which the reconfiguration of the majority is dependent upon a prior process of differentiation, [Deleuze and Guattari] introduce … “becoming-minor” or “minoritarian”, by which they mean the creative process of becoming different or diverging from the majority. This process of becoming-minor, which subjects the standard to a process of continuous variation or deterritorialisation, is the real focus of Deleuze and Guattari’s approach to the politics of difference … the transformative potential of becoming-minor, or becoming-revolutionary … Everyone may attain the creative power of minority-becoming that carries with it the potential for new earths and new peoples.’ Paul Patton, ‘Difference and Politics’, The Deleuze Dictionary, revised edn, ed. Adrian Parr, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, 2005, pp. 77–8.

50. Bateson, Steps to an Ecology of Mind.

51. See Taiaiake Alfred and Jeff Corntassel, ‘Being Indigenous: Resurgences against Contemporary Colonialism’, Government and Opposition, vol. 40, no. 4, 2005, pp. 597–614; Kim Anderson, A Recognition of Being: Reconstructing Native Womanhood, Sumach Press, Toronto, 2000; Tom J. Holm, Diane Pearson and Ben Chavis, ‘Peoplehood: A Model for American Indian Sovereignty in Education’, Wicazo Sa Review, no. 18, 2003, pp. 7–24.

52. Bruno Latour, ‘Why Has Critique Run Out of Steam? From Matters of Fact to Matters of Concern’, Critical Inquiry, no. 30, 2004, pp. 225–48.

53. The ‘discolonial’ is a macro concept conceptualised by Ambēyaŋ language revivalist Callum Clayton-Dixon and Gomeroi poet Rob Waters (both members of the Armidale Aboriginal Community Garden) to refer to a mode of thinking and being that exists simultaneously alongside, but beyond and outside of, the logic of colonialism. Unlike precolonial or postcolonial, the discolonial is not fixed to a particular time period (for example, prior to 1788). Decolonisation is aimed at restoring a discolonial existence, in principle and in practice (personal communication, November 2017).

54. Gabi Briggs, personal communication, 17 August 2015.

56. Gabi Briggs, personal communication, 17 August 2015.

57. Isabelle Stengers, ‘Autonomy and the Intrusion of Gaia’, South Atlantic Quarterly, vol. 116, no. 2, 2017, pp. 391, 398.

58. Philippe Pignarre and Isabelle Stengers use the idea of ‘sorcery’ to describe the way capitalism functions as a system of capture. By characterising capitalism as a form of sorcery, they are concerned with the relationship between individuals and a system; not what that system is, but how it affects and enacts. The idea of ‘sorcery’ evokes a wicked form of capture that an individual is incapable of resisting, making the cultivation of practices of protection necessary. Stengers and Pignarre look to the contemporary neo-pagan witch Starhawk for lessons in how to cultivate practices of protection, as wiccans ‘have learned … the necessity of casting the circle, of creating the closed space where the forces they have a vital need for can be convoked. Philippe Pignarre and Isabelle Stengers, Capitalist Sorcery: Breaking the Spell, trans. Andrew Goffey, Palgrave Macmillan, Hampshire and New York, 2011, p. 135.

59. Stengers, ‘Autonomy and the Intrusion of Gaia’, p. 398.

60. Stephen Muecke, ‘The Mother’s Day Protest’, in his The Mother’s Day Protest and Other Fictocritical Essays, Rowman and Littlefield, London, 2016, p. 24.

61. Natasha Myers, ‘From the Anthropocene to the Planthroposcene: Designing Gardens for Plant/People Involution’, History and Anthropology, vol. 28, no. 3, 2017, pp. 297.

62. Val Plumwood, ‘Decolonising Relationships with Nature’, Philosophy, Activism, Nature, vol. 2, 2002, pp. 7–30; Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy Vol. 1, chapter 31, https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1867-c1/ch31.htm [1867].

63. Audre Lorde, ‘The Masters Tools Will Never Dismantle the Masters House’, in Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches, Crossing Press, Berkeley, 2007 [1984], pp. 110–14.

64. Karan Barad, Meeting the Universe Halfway, Duke University Press, Durham and London, 2007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1215/9780822388128.

65. S. Wright, K. Lloyd, S. Suchet-Pearson, L. Burarrwanga, M. Tofa and Bawaka Country, ‘Telling Stories in, through and with Country: Engaging with Indigenous and More-than-Human Methodologies at Bawaka, NE Australia’, Journal for Cultural Geography, vol. 29, no.1, 2012, p. 42.

66. Hugo Reinart, ‘About a Stone: Some Notes on Geological Conviviality’, Environmental Humanities, vol. 8, no. 1, 2016, p. 106.

68. George E. Marcus (ed.), Para-Sites: A Casebook Against Cynical Reason, University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London, 2000, p. 8.

69. Akwujo Emejulu, ‘The University is Not Innocent: Speaking of Universities’, Verso Books Blog, 2017, https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/3148-the-university-is-not-innocent-speaking-of-universities.

73. Elizabeth Povinelli, The Empire of Love: Toward a Theory of Intimacy, Genealogy and Carnality, Duke University Press, Durham and London, 2006, pp. 231–2

75. Andrew Whelan and Mark McLelland, ‘Management of Risk of Harm as Governing Logic’, paper presented at Cultural Studies Association of Australasia conference, 5 December 2015.

76. For an extensive discussion on this see Land.

80. Gregory Bateson, Mind and Nature: A Necessary Unity, E.P. Dutton, New York, 1979.

81. In Steps to an Ecology of Mind, Gregory Bateson offers the following definition of information: ‘what we mean by information—the elementary unit of information—is a difference which makes a difference’, p. 459.

82. Robert E. Ulanowicz, ‘Process Ecology: Creatura in an Open Universe’, in A Legacy for Living Systems: Gregory Bateson as Precursor to Biosemiotics, ed. Jesper Hoffmeyer, Springer, Dordrecht, 2009, p. 132.

83. Bateson, Ecology of Mind, p. 416.

84. Deleuze and Guattari, p. 157.

85. John Scannell, ‘The Subjectivising Power of the Performative’, Somatechnics, vol. 4, no. 2, p. 320.

86. Donna Haraway, ‘Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Chthulucene: Staying with the Trouble’, in her Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Cthulucene, Duke University Press, London, 2016.

87. Ghassan Hage, ‘Dwelling in the Reality of Utopian Thought’, Traditional Dwellings and Settlement Review, 2011, vol. 1, no. 23, p. 7.

88. Deleuze and Guattari, p. 22.

90. See Land for a discussion on the importance of humility in ally work.

91. Hage, ‘Dwelling in the Reality of Utopian Thought’, p. 11.

95. Bruno Latour builds on Isabelle Stengers’ work to argue that the world is full of ‘propositions’ waiting to be registered by interested bodies in ‘How to Talk about the Body? The Normative Dimensions of Science Studies’, Body and Society, vol. 10, no. 2, 2004, pp. 205–29.

96. Isabelle Stengers, In Catastrophic Times: Resisting the Coming Barbarism, trans. Andrew Goffey, Open Humanities Press in collaboration with Meson Press, London, 2015, http://openhumanitiespress.org/books/download/Stengers_2015_In-Catastrophic -Times.pdf, p. 56.