Making Room for Ghosts

Memory, History and Family Biography on Film

KERREEN ELY-HARPER

MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY

ISSN 1837-8692

Cultural Studies Review 2014. © 2014 Kerreen Ely-Harper. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Citation: Cultural Studies Review (CSR) 2014, 20, 3995, http://dx.doi.org/10.5130/csr.v20i2.3995

The documentary film, Close to the Bone, which I made in 2012, re-tells history through the memory stories of my father's family: the Harper children, postwar British orphans who migrated to Australia in 1948. I was inspired to make the film by documentary's capacity to represent and transmit the lost voices of history, and it is this conceptual premise upon which it was based. Close to the Bone is a case study in how film can speak back to former public representations of the British migrant child by re-constructing an individual family story from autobiographical and familial memories. This article charts the research approach I used and the personal and methodological challenges that I faced when making the film. I discovered in the filmmaking process that the documentary memory film has a lot in common with the ghost story.

The body is a repository for and generator of memories. The body, like memory, is unstable; organic and fickle, not fixed. Like memory the body claims existence, occupies time-space, inhabits place, tells, crafts and repeats stories, forgets and sometimes chooses to be silent. The body as memory can be an unreliable narrator, vulnerable to contamination, disease and sudden death. The filmmaker who stages family memory as lost history is not unlike the genealogist who sets out to study the beginning, adopting a historical perspective not to write history alone but to re-incarnate bodies of familial memories that haunt the living by performing remembering and forgetting on film.

The remembering subject in documentary is like a ghost who has ‘come back’ on film from an ‘already accomplished event’ which is ‘unfolding in the viewer's present’.1 In Ken McMullen's Ghost Dance (1983) Jacques Derrida performed his notion of hauntology. Derrida engages here in a discussion of hauntology's practice and function within the context of history as a study of spectral returnings. Like a ghost that can never be fully present, he as the interview subject cannot be anything more than a ghost, out of sequential linear time-space and therefore out of body and out of history. He can only exist on camera in spectral form. Derrida deems the cinema an art form for conjuring up ghosts, and matches it with his presentation of historical memory as a kind of haunting.2

In her analysis of ghost films as historical allegories, Bliss Cua Lim refers to Derrida's definition in Specters of Marx of historical justice as ‘accountable’ to ghosts from the past and the future.3 Derrida's ghosts are either ‘those who are not born or who are already dead’.4 Lim argues the ghost-film that retells the historical injustice narrative gives new meaning to ‘almost-forgotten’ histories and ‘troubles the boundaries of past, present and future’ by disrupting notions of mortality and linear time as ‘progressive and universal’5 Drawing upon Walter Benjamin's theory of ‘now-time’ (jetztzeit) in reading history as nonlinear and fragmentary, Lim makes her case for the ghost as not only a mechanism for remembering oppressed (and suppressed) pasts but also as a way of thinking about time as non-sequential. Lim suggests ghosts challenge us to consider and re-incorporate past legacies into the future. The ghost-film undermines ‘modernity's homogenous time’, enabling a ‘radicalized accountability to those who are no longer with us, a solidarity with spectres made possible by remembering’.6 It is this notion of radical ‘accountability’ that underpins my proposal that the documentary memory film is a ghost narrative of return: a returning to what has not been understood, recognised or redressed, and to what will not be forgotten by the body.

PERSONAL MEMORY, SOCIAL MEMORY AND THE HISTORIC MOMENT

Personal memory can only become social memory through engagement with the mechanisms and tools of memory transmission. The video camera, following its predecessor, the stills camera, has become an increasingly accessible ‘everyday tool’, influencing both the deconstruction and democratisation of official history and the re-inclusion of the memory narratives of the marginal, invisible, subversive and radical. The amateur video has enabled spontaneous and easy recording of events, thus increasing the participation of historically marginalised individuals and communities in the social memory discourse. The eye witness footage of the Los Angeles Police Department beating Rodney King in 1991, and its repeated use as evidence in court, is according to sociologist Eviatar Zerubavel ‘the ultimate victory of social over personal memory’.7 The Rodney King footage became a site for social memory that then became a tool for social and political resistance. Every time the footage was screened on televisions in homes, public spaces and in court, it became an act of social memory making and re-activation through multiple screenings. You may not have actually been there, at the scene, but you felt as if you had been. Someone else's experience becomes yours, and yours ours through the transmission of an individual memory captured on film. With new technologies and the internet, personal memory on camera (particularly via mobile phones and computers) is increasingly becoming social memory for the collective gaze as previously held distinctions between the private, personal and public are blurred.

Documentary film's visual recording of events and witness accounts at the time and place of the event has earned the genre the status of representing the real, of providing evidence of things as they really are or were. The audiences of the first filmed documentaries marvelled at the moving pictures’ depiction of the real and revered them as ‘truthful’ accounts. The film Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat (Lumiere Brothers, 1895), which depicted a train approaching a station, reportedly caused members of the audience to jump ‘from their chairs in shock’ in the belief they were witnessing a ‘real’ train coming toward them.8 Film enables us to look, replay, revisit and reflect upon an event, to ‘freeze’ a moment in time and space. We watch and perform in films to see ourselves, to be seen by others, and to hold others in our gaze. In documentary films that re-construct history through autobiographical memories and witness testimony, the viewer is invited to re-imagine the past in the present moment. In this process of viewing my imagination meets with my desire to grasp the ‘historical moment’.9

Documentary theorist Malin Wahlberg attributes the viewer's desire to engage with the ‘historical moment’ in documentary to the potential the archival image text has to transgress linear time. Photography historian Anne Marsh similarly ascribes the relationship between photography and viewer desire as inherent in the photograph's ‘potential to deconstruct conventional narrative time’.10 The photograph appears to fix time in its own time. ‘Duped by our desire’ to return to the lost moment, the photograph's capacity to ‘preserve memory, project fantasy and to make the ordinary uncanny’ becomes a ‘kind of theatre in which the subject's desire performs and engages with the mechanism (the camera) and chemical and light processes which will create a virtual image (a photograph) out of a latent object or body’.11

The documentary film as a memory theatre is both an act of memory and a memory trace where the past ‘holds centre stage’ and all participants (on and off screen) are players.12 Film is a ‘multitemporal presentation’ able to bring two events together: the first event the initial recording of an event and the second the viewing of the representation of the first event on film.13 Films as ‘retrospective representational’ objects of memory record sound and images that can be screened repeatedly, reflecting memory as both a cultural practice and an embodied experience.14

Although we might see moving pictures in our mind's eye when we replay a memory, we do not record or store memories like a camera, nor can we call images up at will as an exact replica of the original event.15 Memory is inherently fragmentary, forever complex and potentially always unreliable. The body-mind as a producer of memories is vulnerable to many influences including the internal and external conditions and contexts at the time of an event.

Documentary films that re-construct memory narratives invariably encounter the unreliability of memory. Many films have exploited the phenomena of differing memories of the same event, often pitting interview subjects’ memory accounts against one other to undermine or discount witness testimonies as false or unsubstantiated. Understanding forgetting and the reasons we don't remember things in the same way, even when we are witness to the same event at the same time and place, are important considerations when making a film based on memory narratives. Memory may be fragmented, unreliable, open to contamination and easily influenced but at the same time not necessarily intentionally untruthful on the part of the remembering (or forgetting) subject. Memories can be re-experienced but are not always accompanied by details of all the facts pertaining to the original context, where, for example, the date of the event may be forgotten. The remembering subject's experience may be no less real, or less truthful, than the subject who is able to replay and articulate accurate details of the original event.16

Memories that have not been narrativised into a vocabulary or memorialised in a visible and tangible form such as a photograph, memorial plaque, statue or film remain the silent past ‘casting a shadow’ on the past and future. Histories do get forgotten and historical stories need to be reinvestigated and retold by successive generations for their legacies to be understood, particularly stories of traumatic events. Janet Walker in her study on trauma cinema declares ‘we have an ethical and political obligation to remember’, as well as a responsibility to recognise how events are interpreted, reimagined and communicated on film. Walker describes a ‘paradox’ between the ‘friable’ nature of witness testimony memory and the competing ‘social, political and cultural interests’ of those who seek to write authorised history based on visible evidence (including memory testimonies). She proposes that filmmakers can be ‘helpers and historiographers’ in problematising, and thereby advancing, an understanding and interpretion of the past ‘by elaborating the links between, and the consequences of, catastrophic past events and demon memories’. Audiovisual texts’ ‘plastic’ nature enables them to ‘render the shifting colours and shapes of human experience’. Films that represent traumatic histories ‘externalize, publicize and historicize traumatic material that would otherwise remain at the level of internal, individual psychology’.17

THE BIOGRAPHICAL PERSPECTIVE

For a history to be passed on, it needs to be told. It needs to be heard and seen, it needs to be experienced and felt in the body. Even unwanted histories find their way back into the body psyche despite the best efforts of one generation to eliminate what it would rather forget. A filmmaker who reconstructs genealogy as social history is often drawn to tell their family story in a quest to know the truth about that history or to shed an unwanted familial legacy. Filmmakers who make films about family memories generally tend toward the autobiographical. Significant contributors to the family and autobiographical memory documentary genre include filmmakers such as Rea Tajiri, Terence Davies, Rithy Panh, Sarah Polley, Alan Berliner, Ross Mclwee and Su Friedrich.18

The autobiographical narrative invariably is driven by the quest ‘to know’, to explore, uphold and rework the ‘goals of self’.19 The filmmaker is the knowing subject in the autobiographical film and is always present in the narrative, if not actually appearing on screen. Family figures loom large in the autobiographical narrative, secrets are uncovered, past grievances are named and reconciliations are sometimes achieved. In the case of absent subjects, archival materials, voice-over narration and re-enactments are made to fill representational gaps. The filmmaking process is meant to be a transformative one, in which the filmmaker enacts a personal journey which may involve revisiting a past experience or making a connection with an absent other figure (usually a parent).

Close to the Bone is not concerned with autobiographical memories or the personal on screen journey of the filmmaker (me). As a filmmaker and a family member telling a family story in order to understand the past, to understand myself and my family, I embrace and defend the familial body as ‘radically interactive’ with the social, political and historic.20 I am drawn to creatively reconstruct family memories on film and in doing so I enact both the emotional narrative of familial connection and the wish ‘to rise above it’. British film director Terence Davies in an interview about his autobiographical memory documentary Of Time and the City (2008) describes the transformative capacity of human memory: ‘we are the only species that remember the good and the bad and we rise above it, we rise above it and become something better’.21 Davies believes that becoming ‘something better’ is achieved through our ability to access personal memories. His references to the ‘good and bad’ dichotomy and the concept of rising above the common lot have allegorical connections to the Christian resurrection story and evangelist transformation myths. But as a contemporary (and secular) memory filmmaker Davies is not interested in reinforcing Christian transformation beliefs. Rather, he wants to give credence to the interconnections that exist between the past and the present, between autobiographical memories and narrative. Memory reflects the complexities and contradictions of the human psyche and its generative possibilities for change and reinvention of the autobiographical self. Memories may be stored for permanence (on the internet, in a museum) but memories are not permanent and neither are human lives. Memories are as vulnerable to death and erasure as the bodies that produce them. Films that aim to capture memory narratives are an attempt to protect and preserve bodies of memories no longer accessible in real time and place.

Close to the Bone is a memory and history documentary, which adopts the ‘biographical perspective’ to reconstruct not only the nostalgia narrative of longing for a ‘lost time and lost place’ but also the lost familial figure/s ‘who once inhabited it’.22 As a filmmaker (re) telling my parent/s’ story I am attempting to recover who and what cannot be returned to or restored in real time and place. By keeping an eye on history, as the family biographer I am both a transmitter and translator of personal memory into the domain of social and public memory. The genealogical narrative is one that tells the ‘discontinuous history’ of corporeal impermanence.23 Close to the Bone works through and comes to terms with the past to recreate a family identity. By doing so, it also reclaims the family's place in history as contributors to the great Australian nation building exercise. Central to this is the Harper children's role as poster children for the British and Australian governments’ migration schemes.

THE STAGING OF SOCIAL MEMORY: PHOTOGRAPHING ‘TOMORROW'S AUSTRALIANS’

While Australia is encouraging a cross-section of the British community the accent is on youth as there is no language barrier to overcome. These British children can adapt themselves immediately.

Arthur Calwell, Minister for Immigration, Tomorrow's Australians, 194924

The family photograph is one way families attempt to create a visible and continuous history between family members and a mechanism by which individuals can identify themselves as belonging (or not) to a specific family group. The family photograph as a model of continuity and social cohesion was adopted and adapted by the British and Australian governments, church and welfare institutions in the post World War II period to permeate their narratives of good citizenship.

The Australian Department of Information (later Australian News and Information Bureau) commissioned a great many photographs in the late 1940s and throughout the 1950s to promote postwar migration to Australia. These photographs included pictures of new arrivals: family groups, single adults and sponsored child migrants from the United Kingdom. Publicity photos that represented British child migrants to Australia as healthy, happy and productive were taken to promote the postwar ‘Populate or Perish’ policy, which aimed to populate Australia with ‘Good British stock’.25 Many of these children were commonly described as orphans, although most actually had parents living.26 These official photographs became one of the principal mechanisms through which the British child migrant (‘nobody's child’) was ‘legitimised’ as the good Australian citizen of the future.27 They served the imperialist narrative of both countries.

The arrival photos taken by the Department of Information, church and welfare oganisations (Dr Barnardos, the Fairbridge Society and the Big Brother Movement being the largest) depicted smiling expectant children, waving, running toward the camera, holding suitcases, pointing to landmarks, or taking in their new surroundings (Figures 1 and 2). These British children would become Immigration Minister Arthur Calwell's ‘Tomorrow's Australians’. The photographs hold particular significance for former British child migrants because they are the only documentation many of them have of their childhoods. The photos have come to represent a visible and tangible history that has been previously deemed non-existent and ‘invisible’ by official history.

Figure 1:

The Harper children at Railway Pier, Melbourne (June 1948)

Source: Department of Information publicity still, Australian Government

CLOSE TO THE BONE: A CASE STUDY

In May 1948 the former battle ship SS Ormonde left Tilbury docks in London and set sail for Australia carrying over one thousand ‘free and assisted’ migrant passengers from Great Britain towards what they hoped would be a ‘new and better life’. There were reportedly two hundred and fifty-four children aboard the Ormonde in what the Melbourne Herald newspaper described at the time as a ‘floating nursery’.28 While some children were accompanied by their parents most were in sponsored parties, hosted by various charitable organisations and churches and operating under government-sanctioned child migration schemes. The Harper children from Corby, Northhamptonshire, England, were an unaccompanied group of orphans who belonged to neither of these groups. They were selected out for special attention by the press and government photographers the look of the family group suited their publicity purposes.

The children's Australian Uncle John and Aunt Lizzie, who lived in Brighton, Melbourne, had sponsored the children to come and live with them and their four daughters. The aunt exchanged letters with the Immigration Department and had some personal correspondence with Calwell as she pleaded the case for speedy approval of their application and financial assistance. Justifying her claims, Aunt Lizzie wrote, ‘aren't these the sort of migrants Australia is looking for?’ ‘Good British stock’ was the government's catch cry. Calwell took a personal interest in the case. The records of the Immigration Department reveal the government was tracking the children. In one document, dated 3 June 1948, it is noted in bold ink: ‘Discussed with Mr Hugh Murphy, Department of Information he is talking necessary action for publicity.’29

The Harper children arrived at Station Pier, Melbourne, on 24 June 1948. Arthur Calwell, whose usual practice was to greet new arrivals in person, was not there to meet them because his eleven-year-old son had died a few days earlier. Nevertheless, they received a fanfare of publicity, and photographs of their arrival appeared in newspapers, government pamphlets and journals. In these images the Harper orphans are cast clearly as ‘New Australians’, walking proudly toward their future as good citizens (Figure 1). The six were arranged symmetrically in height from left to right, from the youngest to the eldest. In a chorus line formation, clasping hands or holding onto bags, they move their left foot forward first, heel to toe, followed by the right foot. The Harper children were made to rehearse their moves ‘a couple of times’ in the drama that was being constructed around them.30 They were the leading players in a scripted narrative of nation building.

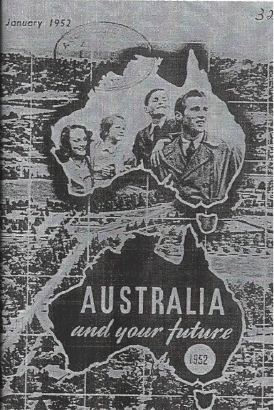

One of the photographs taken that day was cropped into the shape of a map of Australia for the Department of Information's ‘Australia And Your Future’ pamphlet, which was provided to British migrants between 1949 and 1952. (Figures 2 and 3) The children have been refigured to tell a new story. The two middle children (my father and his sister) were cut out of the original picture to remake the image into that of the nuclear postwar family ideal. The eldest brother is recast in the role of the handsome young husband and father, the older sister appears as wife and mother and the two younger siblings complete the happy family postcard as their imaginary children.

Figure 2.

The Harper children at Railway Pier, Melbourne (June 1948)

Source: Department Of Information, publicity still, Australian Government

Figure 3.

‘Australia And Your Future’ pamphlet

Source: Department of Immigration, Australian Government, Fifth Edition, November 1948)

The Immigration Department also constructed the ‘nation as family’ narrative around the children's arrival photographs. Another Immigration Department pamphlet publication, ‘Tomorrow's Australians’, reconstructed the Harper children's story as a fairytale narrative reinforcing the idea of the nation as the rescuing godparent. The headline reads ‘The Immigrant Family of Six Orphans Begins a New Life in Australia. The story of the six Harper children is a sad one, but it has a happy ending’. The piece continues, ‘Six healthy, happy children all growing up straight and strong and good looking’ are heading ‘forward to a rosy future’ until a sudden ‘bitter tragedy’ struck:

The father was killed in an accident. Not long afterwards the mother died. The Harper home was broken up. Young Jane, [Jayne] the eldest of the family, had to stop being a teenager, stop thinking of the next dance, the next frock, and become virtual mother of her brothers and sisters.31

The Harper family story was thus captured as a national image of ‘family togetherness’ in the face of adversity. As the poster nuclear family they were an ideal representation of the public face of the Australian government's White Australia policy.

FAMILY REMEMBERING ON FILM

Today, if you type the Harper name into the on-line search catalogue of Melbourne's Immigration Museum the screen text responds: ‘Your search found no stories.’ Despite all the publicity at the time, the Harper children have gone missing from the public records. So what happened to the Harper orphans? Was coming to Australia the ‘happy ending’ they had been promised? Where are the Harper children now? What do they remember of that period? These questions became the starting points for my application of memory work on film.

The reconstruction of the Harper family history has involved collecting and piecing together family memory texts and archival research in Australia, Great Britain and Ireland. Reading letters and diaries, collecting and viewing photographs and objects, making return visits to places of significance and re-enactments of past events have been some of the strategies I employed to explore on film the act of remembering. I encountered three methodological challenges in adopting these approaches. First was the elusive nature of memory and how individual accounts of the same event vary within the family and can destabilise long held beliefs and family myths. Second, the awareness of an audience (and in the case of film, the presence of a camera) for the participants being filmed to an extent shapes the memory stories they chose to tell and not tell. Third, I had to negotiate my role as the researcher and filmmaker when I was also a participating family member.

These challenges provided significant opportunities to investigate how family memories are created and transmitted within the familial network: how the passing of time, ageing, and social and cultural changes affect individual memory, and how the articulation of British child migrant memories, especially those around displacement trauma and family loss, can contribute to the process of renegotiating a national memory based on the inclusion of historically marginalised voices.

To declare my ‘position’ as researcher and family member—daughter, niece, cousin and goddaughter—is to pay attention to the choices that shape and interpret the familial narrative to be reconstructed by me on film. My interaction with the research participants, who are also my family members, is necessarily interpersonal and deeply intimate. Everyone has different memories and opinions, but we as a family all share a strong desire to know ‘what really happened’. The creative research has become a catalyst for the Harper children (and me) to reinvestigate and rearticulate their childhood memories. For most, their motivation in wanting to participate in the research is concern about what they don't remember and what they want to know more about.

The film does not represent my personal memories, but by asking questions and listening to the Harper children's memories I am an active participant and a witness in what is a ‘shared memory activity’ of imagining and creating a family history.32 Our remembering, as a familial ‘social event’, is transmitted through the camera, operating as a technology of memory, into the public, collective domain.33 Through the creative research process of recording and memory transmission on film, our conversations and autobiographical narratives become embedded within social narratives. What may have been lost to history in the absence of this memory interaction in the past is now restored on film.

THE HARPER CHILDREN'S STORY (RE) TOLD

The Harper children's father died at home at the age of thirty-eight from what was commonly refereed to ‘dust on the lungs’ (pneumoconiosis or ‘black lung disease’), caused by his job as a steel worker from the age of eight. He had promised the children that when he got well they would move to Australia and he would be a better father. Although his promise was not realised, it did sow the first seed of the idea that Australia represented ‘the better life’. Two years later their mother, Maisie, died at the age of thirty-nine after giving birth to an illegitimate child. Maisie had kept her pregnancy a secret from the family by feigning ill health and taking herself off to Scotland. The two eldest children, Jayne and Jim, both teenagers, went to Scotland as soon as they heard of their mother's death, leaving the younger children with neighbours. They were not at all prepared for the circumstances of their mother's death, which carried with it the realisation of her deception and an unwanted baby boy. They decided not to tell the rest of the family what had happened. They followed through with their mother's plan to have the child adopted out through the church. The cause of their mother's death was never explained to the younger children. Septicemia, the flu, ‘a broken heart’ were some of the stories that circulated within the family over the past sixty years.

My father did not see his mother after she left for Scotland, he did not attend her funeral or ever visit her grave. My grandmother's unexpected and unexplained death left the younger Harpers with a silent nagging doubt about what happened to her for the rest of their lives. The older children lived with a difficult and guilty secret. My father and his brother, then aged fourteen and nine, were placed in a boy's home. Their two younger sisters, aged eleven and four, were put in a home for girls. They remained in institutional care until the older children managed to get assistance from their relatives in Australia.

Within a few weeks of their arrival in Australia the ‘happy’ Harpers became embroiled in conflict with their uncle and aunt. Cultural differences and unrealistic expectations eventually led to them being split up into different living arrangements in Melbourne and interstate. It was not until 1984 when the child who had been adopted out in 1947 traced his birth mother's family to the Harpers in Australia that my father and his younger siblings learned the true circumstances of their mother's death.

In the Harper family, migration has been precipitated by maternal deaths over three generations across four countries, from Ireland to Scotland to England and Australia. The untimely death of my grandmother mirrored the premature death of her own mother in Ireland. My grandmother and her three siblings, all under the age of five, were separated and put into the temporary care of relatives—like her own children would be after her death—while their widowed father enlisted to fight in World War I. Maternal death in the Harper family has not only left children without a primary care-giver but has also brought with it a change in status from legitimate to illegitimate, parented to orphaned, and the replacement of one national identity with another. The death of their actual mother and with it the death of the mother symbolic of country and national identity has had a defining effect on the lives of the Harper children.

The publicity photographs have become significant objects of memory and mourning for the Harper children. They are the only images the children have of themselves as a family group. There were no photos of the family before 1948 and none have ever been taken since. In every photo taken after 1948 there is always at least one Harper child missing, a reflection of the conflicts and internal divisions that has arisen from the disruption, bereavement and separation that occurred to the family in their formative years.

ON-CAMERA INTERVIEWS

Close to the Bone is a conscious staging of family history and memory that involves the understanding that memory ‘is the action of telling a story’.34 Janet Walker defines ‘staging’ in documentary as meaning the action or scene ‘would not be occurring if not for the purpose of being filmed’.35 Within this context, Harper family members were invited to participate in performing their individual memory narrative to and for the camera as a consciously staged event. This conscious staging made a purely observational (verité) mode of filmmaking, where there is an attempt to conceive the camera as an impartial unseen observer, inappropriate and less likely to achieve the close focus on memory I was aiming for. Here, I discuss the filmic strategies employed in the film interview process to generate and capture memory performance.

The research interviews were structured around the participants looking at and discussing the publicity photographs and the film's narrative was in turn structured around these memory research interviews. The on-camera interviews were shot employing the interrotron technique developed by documentary filmmaker Errol Morris. Interrotron involves setting up a ‘mirror box’ (or two-way mirror) that reflects a live image of the interviewer and interviewee, thus enabling the interviewee to see the interviewer even while looking directly at the camera lens.

There were two reasons for choosing this technique. Firstly, the interrotron camera style does not allow for free flowing ‘open frame’ camera movement; instead it is conducive to still, ‘closed’ frames and formal composition. The closed frame requires a conscious staging of the subject for symmetry and clarity that complemented my intention to consciously stage memory on film. Second, the interrotron keeps the focus on the interviewee. The interview approach is interactive, but neither my voice nor my physical presence are represented on camera. The biographical focus is on other people's memories. My voice as the filmmaker and family member is represented through text. For example, the film opens with on-screen text: ‘My 15 year old father came to Australia in 1948.’ The audience will not witness an on-screen conversation between the remembering participants and myself, rather they are directed to watch and engage exclusively with the participant performing their autobiographical memories as if they were speaking directly to the audience.

The interrotron technique enables a powerful engagement between the interviewee and the camera (as viewer and witness) that removes the three-way relationship between interviewee, interviewer and camera or audience. You, the viewer, experiences the illusion that the interviewee is speaking directly to you (‘down the barrel’). This technique intensifies the emotional and physiological engagement between the interview subject's gaze and the interviewer or viewer in the camera or ‘seeing’ position. Rather than the participants looking at me (off camera), they are required to look directly at the camera but are able to do so without losing connection because they can still see my reflection. If they did lose eye contact I would direct them to return their gaze to the correct position. This prompting maintained the interaction between us as a shared action of performing for the camera.

Interrotron requires both the interviewer and interviewee to maintain focus and engagement with each other. Neither the camera nor either party can move at will without altering the eye line to camera. By limiting physical movement (of the eye and whole body) the discipline is on speaking and listening. By not seeing me and not being able to read my body language the interviewee engages more with their autobiographical self. The interrotron enables a more direct relationship for the interviewee with the ‘here and now’ and more interaction with ‘problematic present’ and past interactions.36

Filming the Harper children became very much about working through the dynamics of the existing and returning problems of the ‘alive past’ in the present, most specifically around the death of their mother.37 I now look more closely at two selected excerpts from the film for closer analysis of how the camera is used by the rememberer to (re)tell, make meaning and arrive at new understandings of their personal histories and identities.

BETTY REMEMBERS

Betty was ten years old when her mother died. Now seventy-six, she remembers visiting her mother's unmarked grave in England in the early 1980s:

I wanted to sit down there and cry and say goodbye because we'd never said goodbye because when we said goodbye I can remember her going to the carriage I can remember the coat she had on I can remember the cream she had on her face the perfume of it I can even remember the name of it [Eslem] and she only ever used that with some lipstick and she said she'd be back soon and I think that's why it took such a long time because you kept on expecting her to come back and when you don't have the opportunity to say goodbye that's what makes it so hard and so difficult to accept I used to pray even though I knew she was dead I used to pray that by some miracle she would come back and I did that for a long time and then when I came out here I always wanted to go back there to live to be close to her but when I went it was just grass I said goodbye in my own sort of way and I knew then that I would just let go and I came back here and I haven't thought of myself as anything but an Australian since then. I even barrack for the Australians in the cricket now. I never did up until 1985.38

In accepting the loss of her mother, Betty finally accepts her identity as an Australian. But why does she then align her personal mourning memory with which cricket team she has chosen to barrack for? Betty's reference to cricket may be her ‘speaking back’ to the staged Department Of Information photographs (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 4.

Harper Children and Aunt Lizzy, Talofa Avenue, Brighton, Melbourne (1948)

Source: Department Of Information publicity still, Australian Government

Figure 5.

Harper Children and Aunt Lizzy, Talofa Avenue, Brighton, Melbourne (1948)

Source: Department Of Information publicity still, Australian Government

The ‘before’ photograph was taken in the host family home a few days after she arrived in Australia (Figure 4). The children are arranged around the radio ‘listening’ to one of the tests in the famed Donald Bradman-led Australia vs England Ashes series being held in England. In the ‘after’ photograph they are seen cheering for their new country (Figure 5). Arms are raised, scores are noted and Betty now looks directly at the camera as does her younger sister, Margaret, with her thumb in her mouth. Is Betty telling us in her interview that although she might have been made to appear to be barracking for Australia in 1948 she didn't really until 1985?

Betty's personal memory of mourning her mother's death is ‘relocated’ and ‘momentarily merges’ with the collective national memory of Australia winning that cricket test in 1948.39 When she gets to say a final goodbye to her mother, she says goodbye to her country of origin. Betty no longer barracks for England. She says she is no longer British, she is an Australian. The adult speaks back to and relocates the displaced and silenced child in the photographs. Betty's memory narrative foreshadows the film's ending, where the surviving Harper children reflect on their role as poster children for the White Australia policy and what it means for them now to be identified as Australian.

How individual participants in this film construct and situate their memory narratives within other narratives—specifically familial and social memory—is relevant to furthering our understanding of how the Harper children remember. Part of the Harper children's revisionist intention is a desire to set the record straight by speaking back to the photos. The film process offers an opportunity that is seized by them to tell the story they want to tell: what happened then and how it is for them now.

JOHN REMEMBERS

John, seventy-eight, tells us how he wants to remember his mother:

I think it was 2007 before I finally reconciled that my mother was dead because she would have been a hundred years old and I said to myself she wouldn't be alive today so she would be gone and just let it go at that. I know in my own mind in my thinking that 2007 was a sort of cut off date. I've often thought in the intervening years she was always with me and I certainly felt that … I'm sorry I'm getting a bit emotional … but when I have these memories they are always good memories … you say to yourself why this, why did this happen? In today's life you look at your children, you look at your youngest daughter and she has had two children and my God she's forty-three and my mother had six children by the time she was forty and by the time she was forty she was dead. How cruel can life be? I think I'd like to finish there Kerreen … I've touched on a few memories, raw nerves within me … Perhaps at the time if it had been explained to me I would of got over it a lot earlier but for years I just didn't get over it at all … I was lucky I married well and I had a good family and I got on with life in other ways. If you like, forget the past and it's only on occasions like this and you think about the past and you begin to recall everything, you only realise who you are and what makes you the person you are.40

My father tells me he would ‘like to finish there.’ He addresses me formally by name, drawing attention to my witnessing of his story. Exerting his authority he directs me to finish, but in his own time, on his own terms. John is an active participant in shaping the narrative he wants to tell. These memories that touch on ‘raw nerves’ are also ‘good memories’. A child who could not control the death of his mother at the time is now taking back control through reconstructing his autobiographical narrative on film.

The Harper children want to tell their story to an audience. They are hopeful it will be an opportunity to gain insight and understanding about ‘what really happened’ to them as children and how these early experiences have effected their adult lives. Their desire to tell is driven by a number of factors: seeking justice for the injustices they felt as children; desire to be reinstated into the public record; and continuing need to mourn the loss of their mother—a mourning process that was denied them as children.

The Harper family case study is a study in the relationship between individual and family memories within the framework of not only the family's own genealogical history but also Australia's postwar nation-building enterprise. The Harper family has inherited a mythological status through its role and function in the representation of the nation as family, through which they became a property of the postwar British and Australian child migration policies. They were only one group of thousands of children who would play their part in a much larger social agenda, but that part has remained a strong part of their identity.

REFLECTIONS

Stories that are not told or heard can become lost and forgotten. Every generation is faced with the challenge of what it will or will not remember. Every generation must relearn the old stories of past generations if they are to remain in the collective memory for current and future generations. One way of ensuring that former British child migrants are not forgotten is by documenting their social histories and memory stories.

Films are memory diaries, archives of human machinations and ghost narratives. The speaking of childhood silences of the past on film is an opportunity for us to view and consider how individual and social memories are formulated and intertwined within public and personal spheres. We can look at how film can be a vehicle to articulate and re-negotiate our understanding of what constitutes and contributes to a national memory.

The recovery and re-articulation of former British child migrant memories on film, especially those focused around displacement trauma and family loss, demonstrates how documentary practice can make a valuable contribution to the recovery and relocation of lost histories. As a technology of memory transmission the documentary camera provides a representational space for the rememberer to reconstruct and re-evaluate the past they want to tell for present and future generations.

—Kerreen Ely-Harper is a screen educator and filmmaker. Her documentary In Her Own Words won an Australian Teachers of Media (ATOM) award for Best Education Resource (1997). She has received ATOM nominations for her documentary Even Girls Play Footy (2012) and short drama, Parts of A Horse (2004).

NOTES

1. Bliss Cua Lim, ‘Spectral Times: The Ghost Film As Historical Allegory’, Positions: East Asia Cultures Critique, vol. 9, no. 2, Fall 2001, pp. 287–29.

2. Jacques Derrida, Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt. The Work of Mourning, and the New International, Routledge, New York, 1994. See also Nchamah Miller's essay, ‘Hauntology and History in Jacques Derrida's Specters of Marx’, York University 2003, <http://www.nodo50.org/cubasigloXXI/taller/miller_100304.pdf>, p. 11.

3. Derrida, p. 116; Lim, p. 318.

6. Lim, pp. 318–19. See Walter Benjamin, ‘On The Concept of History’, in Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings, vol. 4, 1938–1940. p. 395.

7. Eviatar Zerubavel, Time Maps: Collective Memory and the Social Shape of the Past, University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London, 2003, p. 28.

8. Noel Burch, Life to Those Shadows, British Film Institute, London, 1990, p. 39; Martin Loiperdinger, ‘Lumiere's Arrival of the Train: Cinema's Founding Myth’, The Moving Image, vol. 4, no. 1, 2004, pp. 89–118.

9. Malin Wahlberg, Documentary Time: Film and Phenomenology, University Of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 2008, p. xiv.

10. Anne Marsh, The Darkroom: Photography And The Theatre of Desire, Macmillan, Sydney, 2003, p. 266.

11. Anne Marsh, The Darkroom: Photography And The Theatre of Desire, Macmillan, Sydney, 2003, p. 266.

12. Daniel N. Stern, The Present Moment in Psychotherapy and Everyday Life, W.W. Norton & Company, New York, 2004, p. 33.

13. Daniel N. Stern, The Present Moment in Psychotherapy and Everyday Life, W.W. Norton & Company, New York, 2004, p. 207.

14. Janet Walker, Trauma Cinema: Documenting Incest and the Holocaust, University of California Press, Berkeley, 2005, p. 29.

15. Antonio Damasio, ‘How Memory Works’, Big Think Forum, 2 July 2010, <http://bigthink.com/videos/how-memory-works>.

16. Shoshana Felman and Dori Laub, Testimony: Crises of Witnessing in Literature, Psychoanalysis, and History, Routledge, New York, 1992, p. 61–2.

18. See, for example, Rea Tajiri, History and Memory: For Akikio and Takashige (1991); Terence Davies, Of Time and the City (2008); Rithy Panh, The Missing Picture (2013); Sarah Polley, Stories We Tell (2012); Alan Berliner, The Family Album (2008); Ross Mclwee, Bright Leaves ( 2003); Su Friedrich, The Ties That Bind (1984).

19. Martin A. Conway, ‘Sensory-perceptual Episodic Memory and its Context: Autobiographical Memory’, The Philosophical Transactions Of The Royal Society B, vol. 356, no. 1413, 2001, pp. 1375–6.

20. Elaine Reese and Robyn Fivush, ‘The Development of Collective Remembering’, Memory, April 2008, vol. 16, no. 3, p. 1. See also Maurice Halbwachs, ‘Historical Memory and Collective Memory’, The Collective Memory, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1992, pp. 50–1.

21. Terence Davies, hurricanefilms, 25 October 2010, <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8DKgiDmHLKQ>.

22. Walker, p. 119. Svetlana Boym, The Future of Nostalgia, Basic Books, New York, 2001, p. ix.

23. Ann Curthoys and John Docker, Is History Fiction?, UNSW Press, Sydney, 2010, p. 184.

24. Tomorrow's Australians, 1949, directed by Jack S. Allan. Produced by Department of Information and Australian National Film Board. Australian Diary. No 030. Newsreel series.

25. Michelle Langfield, More People Imperative: Immigration to Australia 1901–39, National Archives of Australia, Research Guide, no 7, February 1999. Barry Coldrey, Good British Stock: Child and Youth Migration to Australia, National Archives of Australia, 1999.

26. Parliament of Australia, Lost Innocents: Righting the Records, Parliament of Australia, Canberra, 2001, 1.47, p. 40.

27. Lydia Murdoch, Imagined Orphans: Poor Families, Child Welfare and Contested Citizenship in London, Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, 2006.

28. ‘Reinforcements Here for Harper Family From England In “Floating Nursery”’, Herald, 24 June 1948, p. 3.

29. Harper family 1948 confidential case file, accessed by author under the FOI Act, currently held in Department of Immigration.

30. Kerreen Ely-Harper, Close to the Bone, Macquarie University, documentary film, 2012.

31. ‘Tomorrow's Australians’, Department of Immigration, Australian Government no. 5, August 1948.

32. John Sutton, ‘Collective Memory: Coordinating, Interaction, Distribution’, Social Research, vol. 75, no. 1, Spring 2008, pp. 23–48.

33. Henry L. Roediger, Erik T. Bergman and Michelle L. Meade, ‘Repeated Reproduction from Memory’, in A. Saito (ed.), Bartlett, Culture and Cognition, Routledge, London, 2000, pp. 115–34.

34. Pierre Janet, Psychological Healing: A Historical and Clinical Study, vol 1, G. Allen & Unwin, London, 1925. Quoted in Russell Meares, The Metaphor of Play: Origin and Breakdown of Personal Being, Routledge, London, 2005, p. 166.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Benjamin, W., ‘On The Concept of History’, in Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings, Vol. 4, 1938–1940.

Boym, S., The Future of Nostalgia, Basic Books, New York, 2001.

Burch, N., Life to Those Shadows, British Film Institute, London, 1990.

Coldrey, B., Good British Stock: Child and Youth Migration to Australia, National Archives of Australia, 1999.

Conway, M.A., ‘Sensory-perceptual Episodic Memory and its Context: Autobiographical Memory’, The Philosophical Transactions Of The Royal Society B, vol. 356, no. 1413, 2001. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2001.0940

Curthoys A., and J. Docker, Is History Fiction?, UNSW Press, Sydney, 2010.

Damasio, A., ‘How Memory Works’, Big Think Forum, 2 July 2010, http://bigthink.com/videos/how-memory-works.

Davies, T., hurricanefilms, 25 October 2010, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8DKgiDmHLKQ.

Department of Immigration, Harper family 1948 confidential case file, accessed by author under the FOI Act, currently held in Department of Immigration.

Department of Immigration, ‘Tomorrow's Australians’, Australian Government, no. 5, August 1948.

Derrida, J., Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt. The Work of Mourning, and the New International, Routledge, New York, 1994.

Felman, S. and D. Laub, Testimony: Crises of Witnessing in Literature, Psychoanalysis, and History, Routledge, New York, 1992.

Halbwachs, M., ‘Historical Memory and Collective Memory’, The Collective Memory, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992.

Herald, ‘Reinforcements Here for Harper Family From England In ‘Floating Nursery’, The Herald, 24 June 1948.

Janet, P., Psychological Healing: A Historical and Slinical Study, vol 1, G. Allen & Unwin, London, 1925.

Langfield, M., More People Imperative: Immigration to Australia 1901–39, National Archives of Australia. Research Guide, No 7, February 1999.

Lim, B.C., ‘Spectral Times: The Ghost Film As Historical Allegory’, Positions: East Asia Cultures Critique, vol. 9, no. 2, Fall 2001.

Loiperdinger, M., ‘Lumiere's Arrival of the Train: Cinema's Founding Myth’, The Moving Image, vol. 4, no 1, 2004. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/mov.2004.0014

Marsh, A., The Darkroom: Photography And The Theatre of Desire, Macmillan, Sydney, 2003.

Meares, R., The Metaphor of Play: Origin and Breakdown of Personal Being, Routledge, London, 2005.

Miller, N., ‘Hauntology and History in Jacques Derrida's Specters of Marx’, York University, 2003, http://www.nodo50.org/cubasigloXXI/taller/miller_100304.pdf.

Murdoch, L., Imagined Orphans: Poor Families, Child Welfare and Contested Citizenship in London, Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, 2006.

Parliament of Australia, Lost Innocents: Righting the Records, Parliament of Australia, Canberra, 2001.

Parliament of Australia, Forgotten Australians: A Report on Australian who Experienced Institutional or Out-of-home-care as Children, Parliament of Australia, Canberra, 2004.

Parliament of Australia, Lost Innocents and Forgotten Australians Revisited, Parliament of Australia, Canberra, 2009.

Reese, E. and R. Fivush, ‘The Development of Collective Remembering’, Memory, vol. 16, no. 3, April 2008. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09658210701806516

Roediger, H. L., E. T. Bergman and M. L. Meade, ‘Repeated Reproduction from Memory’, in A. Saito (ed.), Bartlett, Culture and Cognition, Routledge, London, 2000.

Stern, D. N., The Present Moment in Psychotherapy and Everyday Life, W.W. Norton & Company, New York, 2004.

Sutton, J., ‘Collective Memory: Coordinating, Interaction, Distribution’, Social Research, vol. 75, no. 1, Spring 2008.

Wahlberg, M., Documentary Time: Film and Phenomenology, University Of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 2008.

Walker, J., Trauma Cinema: Documenting Incest and the Holocaust, University of California Press, Berkeley, 2005.

Zerubavel, E., Time Maps: Collective Memory and the Social Shape of the Past, University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London, 2003. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226924908.001.0001