Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance

Issue 30

December 2025

RESEARCH AND EVALUATION (PEER REVIEWED)

Local Government Staff Perceptions of Accountants’ Ethical Conduct: A Case Study of Kassena-Nankana Municipal Assembly, Ghana

Mohammed Bashar Aliu

University of Professional Studies, Accra, PO Box LG 149, Legon Accra, Ghana, vicealti@yahoo.com

University of Professional Studies, Accra, PO Box LG 149, Legon Accra, Ghana, Adam.salifu@upsamail.edu.gh

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/.pkt2fh59

Article History: Received 20/01/2025; Accepted 04/11/2025; Published 31/12/2025

Citation: Aliu, M. B., Salifu, A. 2025. Local Government Staff Perceptions of Accountants’ Ethical Conduct: A Case Study of Kassena-Nankana Municipal Assembly, Ghana. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, 30, 41–61. https://doi.org/10.5130/.pkt2fh59

© 2025 by the author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercial, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Abstract

This study examines local government staff perceptions of whether accountants within the Kassena-Nankana Municipal Assembly, Ghana behave ethically. Within Ghana’s decentralised governance system, accountants play a central role in safeguarding public resources, yet little is known about how ethical they are perceived to be by colleagues. Using a qualitative case study design, data was collected through semi-structured interviews with staff from eight departments. Thematic analysis, guided by Rest’s four-component model of ethical decision-making, revealed gaps in ethical awareness, inconsistent training, and organisational pressures that undermine ethical conduct. While staff expressed strong intent to act ethically, weak institutional support, political interference and limited enforcement of policies often prevented ethical judgement from translating into action. The study findings underscore the need for continuous, context-specific ethics training and stronger institutional safeguards. The study contributes to the literature by extending Rest’s model to show how organisational culture mediates the translation of ethical intent into practice.

Keywords

Local Government; Ethical Standards; Ethical Training; Public Accountability; Ethical Awareness; Ghana

Introduction

Ethical governance has emerged as a critical concern in public administration, particularly within decentralised systems, where local governments are entrusted with delivering essential services and managing public resources. The conduct of public-sector accountants, who bear responsibility for ensuring the integrity of financial management processes, lies at the core of this discourse. Recent concerns over financial misreporting, fund misappropriation and procedural irregularities have raised questions about how ethical standards are applied in local governance (Shree 2024). In both private and public sectors, these standards act as both regulatory requirements and a moral compass, shaping integrity, transparency and accountability (Temitayo et al. 2024). Ethical standards promote honesty, responsibility, objectivity and fairness, underpinning institutional legitimacy and public trust. However, applying ethical principles in real-world financial contexts is often compromised by illegal practices such as fraudulent reporting, nondisclosure of critical financial information, asset misappropriation, and other forms of financial mismanagement. This type of malpractice undermines institutional credibility and erodes public confidence in governance systems (Shree 2024; Temitayo et al. 2024).

In Ghana’s decentralised governance framework, local government institutions – specifically the metropolitan, municipal and district assemblies (MMDAs) – occupy a critical space in managing public resources and delivering essential services. Given their proximity to citizens, these institutions are particularly vulnerable to unethical pressure from limited resources, competing interests and unnecessary public interference. Accountants in local government play a vital role, as they are tasked with ensuring that financial records are accurate, transparent, and consistent with professional and statutory ethical standards (Azeez 2024). However, their ability to discharge this role effectively depends on their technical skills and the organisational context within which they operate.

Although professional codes of conduct bind accountants, the ethical ecosystem within which they function involves the awareness, perceptions and behaviours of other staff members within the organisation. Ethical lapses in accounting are often symptomatic of broader institutional challenges, including weak oversight mechanisms, a lack of training, inconsistent enforcement of regulations, and varying degrees of ethical awareness among non-accounting staff. As Barker and White (2020) observed, the failure to cultivate a shared understanding of ethical principles across departments can lead to unintentional violations or misjudgements, thereby compromising institutional accountability.

Despite the proliferation of ethical codes and standards within public financial management systems, a notable gap remains in understanding how staff, elected representatives and political appointees in local governments perceive and interpret these standards, particularly those not directly involved in accounting functions. Most studies have focused on the actions and responsibilities of accountants rather than on the perspectives of other staff and other elected or appointed representatives, whose attitudes, expectations and experiences can significantly influence ethical outcomes within the organisation. For example, Ayee (2001), in his case study on civil service reform in Ghana, found that non-financial staff often perceived ethical codes as irrelevant or a top-down imposition. Similarly, Lawton and Macaulay (2004) reported in their study that ethical codes were viewed by non-finance staff as abstract or overly bureaucratic, highlighting a disconnect between the formal ethical framework and its practical relevance in day-to-day operations. Furthermore, while there is general agreement on the importance of ethics training in improving workplace behaviour, there is limited empirical evidence on the extent to which such training initiatives enhance ethical decision-making and conduct within local government assemblies.

This study explores how local government staff perceive the ethical responsibilities of accountants within the context of the Kassena-Nankana Municipal Assembly (KNMA) in Ghana’s Upper East Region. This research examines the level of ethical awareness among staff, the organisational and contextual factors that shape their perceptions, and the impact of training programmes on ethical conduct. By adopting a qualitative case study approach, the authors aim to provide a deeper understanding of the complex ethical dynamics that influence accountants’ conduct in local governments. The findings from this study are expected to contribute not only to the academic literature on public sector ethics, but also to policy and practice by highlighting the need for more inclusive and context-specific ethical training programmes, stronger ethical cultures, and systemic interventions to support ethical conduct within local governments.

Study context: Kassena-Nankana Municipal Assembly

Presenting a brief profile of KNMA is important because the municipality’s socio-economic and institutional characteristics directly shape the ethical environment in which KNMA’s accountants operate, and influence how their conduct is perceived by staff. KNMA serves as the principal administrative authority for the Kassena-Nankana municipality. With a land area of approximately 1,100km2 and a population of 121,437, according to the 2021 Population and Housing Census (Ghana Statistical Service 2021), the municipality is predominantly rural, with agriculture as the primary economic activity. Over 70% of the working population is engaged in subsistence farming (Ghana Statistical Service 2021; Ghana Districts 2023). Local people and the municipal assembly face persistent challenges, such as food insecurity, limited infrastructure, high youth unemployment and climate vulnerability.

These socio-economic and demographic conditions directly affect the assembly’s ability to mobilise resources and fulfil its developmental mandate under the Local Government Act 2016 (Act 936). Limited revenue generation, dependence on central government transfers and institutional inefficiencies (Institute for Democratic Governance 2020) create financial pressures that heighten the likelihood of ethical dilemmas in resource management.

The assembly’s governance structure – which combines elected representatives, technical staff and career bureaucrats – further introduces tensions between political imperatives and professional standards (Ayee 2019). Within this environment, accountants are at the centre of financial management, expected to uphold ethical standards despite weak accountability systems, recurring audit delays, and documented cases of fund misapplication (Audit Service of Ghana 2022). Moreover, the rural setting constrains access to professional ethics training and capacity-building opportunities (Commonwealth Local Government Forum 2022), shaping how staff interpret accountants’ actions. The selection of KNMA as a case study is therefore deliberate. Its socio-economic profile and institutional context provide critical insight into how local government staff perceive accountants’ ethical conduct and, by extension, how broader issues of accountability and ethical governance play out in Ghana’s decentralised system.

Literature review and conceptual framework

This section synthesises current knowledge on ethical standards in public sector accounting, the influence of organisational culture and leadership on ethical behaviour, the challenges encountered in upholding ethics in local governments, and the broader implications for public trust. It employs 1) Rest’s four-component model of ethical decision-making (Rogers and Breakey 2023; Craft and Shannon 2025) and 2) organisational culture as theoretical lenses for the study (Barrainkua and Espinosa-Pike 2018; Mekonnen 2025).

Ethical standards in public sector accounting and governance

Professional accountants operating within the public sector are guided by internationally recognised ethical codes that emphasise integrity, objectivity, transparency and accountability. These values are codified in national frameworks such as the Ghana Accounting Standards and the International Federation of Accountants (IFAC) Code of Ethics. Within local government settings, adherence to these standards is essential for maintaining public trust and ensuring sound financial governance (Nafiisa et al. 2023; García et al. 2024). However, empirical research has indicated that local government accountants often face systemic constraints that hinder compliance. These include inadequate training, resource limitations, and conflicting pressures from political actors (Cohen and Pant 1991; Zimmerman 2016).

While much of the literature focuses on accountants’ actions, there is increasing recognition that ethical behaviour is also shaped by the perceptions and interactions of non-accounting staff within the same institution. These perceptions influence organisational norms and the degree of accountability expected of finance professionals (Widyawati and Saud 2015). As such, understanding the ethical landscape within local governments requires an examination of formal standards and how these standards are socially constructed, interpreted, and sometimes contested by staff and elected or appointed representatives across departments.

Organisational culture, leadership, and ethical behaviour

Organisational culture and leadership have been shown to play a significant role in shaping ethical conduct in public institutions. A favourable ethical climate, characterised by clearly communicated values, ethical role-modelling by leaders, and institutional support for whistleblowing, has been linked to enhanced staff motivation and reduced incidences of unethical behaviour (Victor and Cullen 1988; Demir et al. 2023). In contrast, where organisational values are ambiguous or inconsistently enforced, employees are more likely to engage in, ignore or rationalise ethical violations (Lestari and Saud 2024; Kamau and Gakobo 2024).

Leadership styles, particularly those grounded in ethical and transformational principles, can foster institutional environments where accountability and integrity are upheld. Ethical leaders not only influence individual behaviour through example, but also shape the collective expectations of their teams (Brown and Treviño 2006). This dynamic is especially pertinent in local government settings where informal practices and interpersonal relationships often exert a more decisive influence than formal rules or regulations. Therefore, organisational support mechanisms, including regular ethics training, ethical reporting frameworks, and performance appraisals that reward ethical behaviour are critical to sustaining an ethical work culture.

Ethical challenges, dilemmas, and impacts on public trust

Although ethical approaches are formalised through laws and codes, local government staff often face dilemmas such as conflicting loyalties, weak accountability, and pressure to compromise ethical standards. Accountants in particular may be asked to falsify reports, conceal misuse of funds, or overlook irregular procurement (Blake and Gowthorpe 1998; Parmar 2016). Without safeguards, such pressures erode professional standards and staff morale.

Significantly, the consequences of unethical conduct extend beyond internal dysfunction; they directly affect public perceptions of governance. Ethical lapses in local governments are often visible and personal to communities, diminishing trust in the state and compromising citizen engagement (Amrizal 2018; Azeez 2024). Studies have consistently found that public trust in governments correlates with perceptions of fairness, financial transparency and procedural integrity. Even well-intentioned development efforts may be viewed with scepticism, where these are absent.

Consequently, restoring or sustaining public trust in local government institutions requires a multifaceted approach that combines clear ethical standards, robust institutional frameworks, and an organisational culture that empowers staff to act ethically despite institutional pressure.

Theoretical and conceptual framework

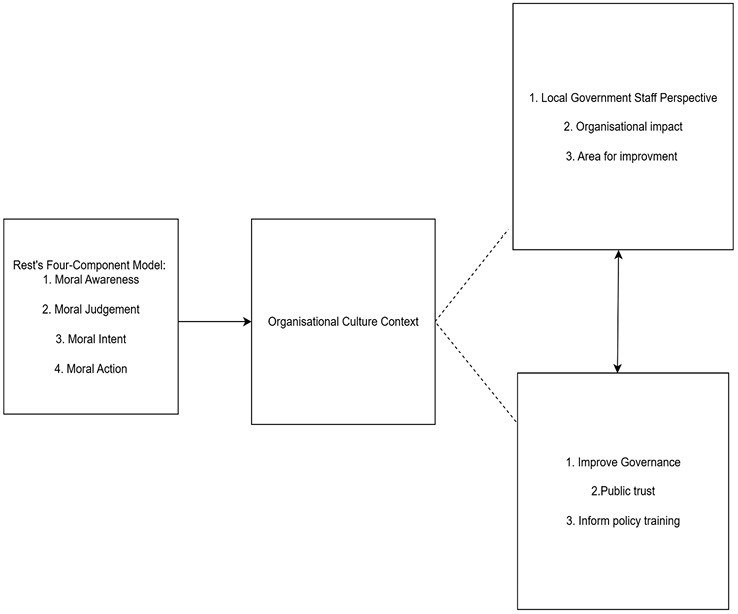

This study employs Rest’s four-component model of ethical decision-making as its core theoretical lens to analyse how local government staff perceive accountants’ ethical conduct. This model posits that ethical behaviour arises from a sequence of four psychological processes – moral awareness, moral judgement, moral intent and moral action – as shown in Figure 1 (Khursheed et al. 2019).

Figure 1. Integrating Rest’s four-component model and organisational culture: a conceptual framework for ethical governance in local government

Source: Authors’ construct, 2025

Rest’s model offers a structured lens through which the ethical conduct of individuals within organisations can be understood.

The first component, moral awareness, refers to the recognition of ethical dimensions embedded within a situation. This awareness is influenced by contextual cues, prior ethical training, and extent of exposure to professional discourse on ethics. In the context of local government, moral awareness might manifest in recognising practices such as inflated budgets, the insertion of ghost names on payrolls, or irregularities in procurement procedures as ethically problematic behaviours.

Once an ethical issue is identified, the individual proceeds to the second stage, moral judgement, which involves evaluating various courses of action to determine the most ethically appropriate one. This process relies heavily on analytical capacity, clarity of values, and familiarity with professional codes of conduct. During this stage, individuals weigh competing interests and assess their various consequences in the light of ethical standards.

The third stage is moral intent, which represents the internal motivation and commitment to pursue the ethically correct course of action, even when doing so may conflict with personal interests, peer pressure, or institutional expectations. Moral intent reflects an individual’s prioritisation of ethical values over expediency or self-preservation.

The final component, moral action, involves executing ethical decisions through concrete behaviour. However, this step can be significantly influenced – or even obstructed – by organisational realities such as inadequate whistleblower protections, fear of retaliation, or institutional inertia (Procópio 2019). Thus, while an individual may recognise an ethical issue and intend to act ethically, successfully translating intention into action often depends on the broader organisational environment. While Rest’s model focuses on individual cognitive processes, this study extends it by incorporating organisational culture as a mediating factor. The ethical climate of an organisation, including leadership support, peer influence and institutional safeguards, shapes whether individual moral awareness and intent are likely to be translated into action (Bogale and Debela 2024). Looking at ethical decisions through this dual framework allows for an integrated analysis of how personal and institutional factors influence staff ethical behaviour.

Research design and methodology

This study adopts a qualitative approach. Given the exploratory nature of the research, the qualitative approach was deemed most suitable, as it enables an in-depth investigation of participant experiences, insights and interpretations in their natural contexts (Bryman 2016; Creswell and Poth 2017). A case study design was adopted to provide a focused and context-specific understanding of ethical perceptions within a municipal assembly (Yin 2018). This design was particularly appropriate because it allowed the study to situate KNMA staff perceptions of accountants’ ethical conduct within the broader socio-political and institutional realities of the municipality.

Sampling strategy

A purposive sampling strategy was employed to identify participants with relevant exposure to the work of the finance or accounting departments within the KNMA. This approach ensured that the selected individuals had either direct interaction with accountants or worked in roles that were significantly influenced by accounting practices (Palinkas et al. 2015; Etikan et al. 2016). Participants were drawn from departments such as procurement, internal audits, budgeting, administration, parks and gardens, works, and transport. The accounting department was deliberately excluded to maintain an external perspective on accountants’ conduct and ethical practices.

The study initially aimed to include participants from 15 departments. However, interviews across eight departments revealed recurring views, with no new themes emerging. This thematic consistency indicated data saturation (Guest et al. 2006; Palinkas et al. 2015), supporting the adequacy of the sample.

Data collection methods

Data was collected through semi-structured interviews, a method well suited to capturing deep, reflective responses and uncovering the meanings participants attach to their experiences (DiCicco-Bloom and Crabtree 2006; Kvale and Brinkmann 2015). This approach allowed the interviewer to probe, clarify and explore emergent issues during the interviews while maintaining consistency through a thematic protocol designed around the study’s conceptual framework, particularly Rest’s four-component model. Semi-structured interviews are especially useful for exploring sensitive ethical issues as they allow flexibility in following participant narratives while still ensuring comparability across responses (Gill et al. 2008).

To minimise researcher bias, careful phrasing of questions and adherence to ethical interviewing standards were maintained throughout the process (Kvale and Brinkmann 2015).

Data analysis

The data collected from the semi-structured interviews was analysed using a thematic approach, which is well suited for identifying, analysing and reporting recurring patterns in qualitative data (Braun and Clarke 2006; Guest et al. 2012). The analysis followed a structured, multi-stage approach. First, interviews were transcribed verbatim to preserve meaning. Open coding was then applied to generate initial codes, following by axial coding to identify relationships among categories, and finally selective coding to distil central themes (Guest et al. 2012).

NVivo 12 software facilitated the management of data, coding and theme retrieval. To ensure trustworthiness and rigour, the study incorporated peer debriefing and independent cross-checking of coded transcripts (Nowell et al. 2017). Attention was also paid to contextual nuances, emotional tones and non-verbal cues observed during the interview, ensuring that findings reflected the institutional and ethical complexities shaping staff perceptions.

Findings

The analysis revealed five interrelated themes that shape staff perceptions of accountants’ ethical conduct within the KNMA. These themes highlight staff experiences of ethical awareness and training, the dilemmas encountered in accounting practices, the perceived effectiveness of ethical policies, the organisational and external influences on ethical behaviour, and the link between public trust and accountability. Together, the findings illustrate the tensions between ethical principles and the practical realities of local government financial management. Table 1 summarises the five themes, and illustrative quotations that informed each category.

Source: Authors’ fieldwork, 2025

Enhancing ethical awareness and training among local government accountants

Participants widely acknowledged that ethical conduct is foundational to maintaining integrity in public services, especially in local government settings where financial management directly impacts public trust. A consistent theme across the interviews was the variable level of ethical awareness among staff members, which was attributed to limited and irregular training opportunities. This disparity in understanding was noted as a critical gap that required a structured intervention. An internal auditor observed, “there seems to be limited understanding among staff but this can easily be resolved through clear guidelines and training.” Similar concerns were raised by two budgeting officers and an internal auditor, who emphasised that while ethics training exists, it is neither comprehensive nor frequent enough to address the complex and evolving nature of ethical issues in public service. By contrast, respondents from administration and works departments reported having had little or no access to ethics training in the past two years: “Since my appointment to the assembly two years ago, no formal training programme has been conducted,” an administrative officer emphasised.

The findings therefore reveal a shared perception, across multiple departments, that existing training programmes are insufficient to meet current ethical demands. Three respondents from the budgeting, works, and transport units emphasised the need for more robust and frequent training, with one staff member from the works department stating, “Yes, but more emphasis on training and awareness is needed,” suggesting that the depth and impact of current initiatives are limited. This critique recognises that ethical training must move beyond introductory sessions and evolve into a continuous learning process embedded within institutional culture.

Respondents from departments tasked with audits and procurement also stressed the importance of ongoing training in responding to changes in standards, laws and expectations. An audit officer succinctly remarked, “Continuous training is necessary due to evolving standards,” emphasising the dynamic nature of ethical obligations in financial governance. In response to this reality, both procurement and budgeting staff specifically called for ethics education to be updated regularly and tailored to the current institutional and regulatory conditions. This would ensure that staff members understand existing policies and are equipped to interpret and apply them in new or unfamiliar scenarios.

Beyond content delivery, the structure and evaluation of training were also raised as concerns. Two procurement officers proposed that ethics training should include mechanisms for feedback and reflection, allowing organisations to assess what has been learned and where gaps remain. As one respondent from the procurement unit suggested, “Periodic evaluations and reviews could enhance understanding,” highlighting the need for systematic follow-up to determine whether training has a lasting impact on behaviour and decision-making.

Collectively, these insights point to a pressing need for more intentional and comprehensive ethics capacity-building within local government institutions. The perceived inconsistencies in levels of ethical knowledge and calls for structured, ongoing training indicate that efforts to foster ethical awareness must be integrated into broader institutional development strategies. Building a shared ethical foundation among staff grounded in formal guidelines and applied reasoning will strengthen both ethical culture and accountability in the local government context.

Ethical dilemmas in local government accounting

Ethical dilemmas in local government accounting are not abstract challenges, but routine occurrences that test staff’s moral judgement, resilience and professionalism. Some participants described situations in which they were confronted with decisions that required balancing organisational expectations, legal obligations, and personal ethical convictions. These dilemmas often emerge from systemic weaknesses, institutional pressures, and competing interests in financial governance.

For example, an officer from the budgeting department recalled “an example of being pressured to process a warrant to pay for unauthorised expenditures”. He went on to say that he had resolved it “by escalating the issue”. This case underscores the institutional tension between ethical standards and hierarchical directives, while the act of escalation demonstrates professional integrity in the face of pressures.

A works department officer recalled a “contractor demanding immediate payment for an Interim Payment Certificate”. The monitoring team resisted and completed all checks despite the pressure. This example shows how collective decision-making and adherence to procedures can safeguard against unethical practices.

From the internal audit unit, one staff member recounted “discovering a misclassification of expenses leading to a necessary restatement of financial statements through the escalation of the issue.” This example reflects the importance of accountability and professional courage to ensure transparency in financial reporting, even when it requires revisiting past decisions.

By contrast, administrative staff and officers from parks and gardens reported no direct encounters with ethical dilemmas, offering responses such as “No specific experience shared” or “Not yet faced an ethical dilemma”. This suggests that exposure to ethical conflict may depend on department or role: those in finance-related units face more ethical risks, while staff in administrative or technical units may encounter them less frequently. Alternatively, the absence of reported experiences may indicate reluctance to disclose sensitive information or a tendency to normalise questionable practices as routine.

Overall, this theme illustrates both the everyday nature of ethical decision-making in local government accounting and the mixed capacity of staff to navigate such challenges. While some budgeting, works and audit staff demonstrated resilience and confidence in confronting misconduct, administrative and technical departments showed limited awareness or direct exposure. These findings reinforce the need for ethical training that not only builds awareness of subtle dilemmas but also equips staff across all units with practical strategies for responding to the pressures of financial governance.

Effectiveness of ethical policies

Ethical policies and codes of conduct are foundational tools for fostering the integrity, transparency and accountability of local governments. Participants generally acknowledged the importance of these frameworks and their potential to guide ethical behaviour. However, the responses also revealed tension between the existence of policies and the realities of their implementation and enforcement.

From the procurement unit, a respondent remarked: “Effective if adhered to properly” reflecting a common belief that policy alone does not ensure ethical behaviour; compliance and enforcement are what determine their effectiveness. This perspective was echoed by an internal audit officer who observed that policies are “very effective, monitored, and evaluated,” pointing to the importance of oversight mechanisms in translating written guidelines into practice.

By contrast, staff in administration described policies as “Fairly effective but needs improvement” while a budgeting department respondent noted that “Weak enforcement reduces impact”. These views highlight how well-intentioned frameworks often fall short due to gaps in leadership commitment or operational follow-through. Such comments reflect a broader challenge in public institutions, where rules may exist on paper but be undermined by institutional inertia or lack of accountability.

Leadership has emerged as a central factor shaping the efficacy of ethical policies. An officer from the transport unit stressed: “Commitment to ethical behaviour from leadership is crucial” reinforcing that ethical governance must be modelled from the top. This sentiment resonates with scholarship on public sector ethics, which emphasises the decisive role of senior officials in shaping organisational culture (Lawton and Páez 2015). Beyond leadership, participants also identified the need for stronger internal control systems to support policy enforcement. A respondent from the budgeting unit suggested the need to strengthen “internal controls and underscore the operational dimension of ethical policy implementation”. Mechanisms such as checks and balances, independent audits and automated monitoring systems were seen as crucial to embedding ethics into practice and reducing reliance on individual discretion.

The interplay between leadership, policy and organisational values was further emphasised by a works department office respondent who argued that “strong leadership and clear policies are needed”. Such statements highlight that policies are most effective when aligned with institutional culture and championed by leaders. If leadership tolerates circumvention or inconsistency, policies lose normative force and staff moral intent declines.

Finally, some participants linked the effective application of ethical policies to public trust in local governance. For instance, a respondent from the administrative unit observed: “Ethical policies positively influence public trust” suggesting that consistent enforcement and transparency in communication not only enhance internal accountability but also build external legitimacy. This underscores the dual function of ethical policies as both internal governance tools and external signals of integrity to the wider community.

Influencing factors on ethical practices

Participants highlighted interconnected internal and external factors that shape ethical behaviour within local government accounting. These influences operate at multiple levels – individual, organisational and systemic – as they interact to reinforce or undermine ethical conduct.

The recurring internal influence cited by some respondents was leadership behaviour. Staff across finance-related units (budgeting, procurement, and internal audit) emphasised the importance of ethical leadership in setting expectations, modelling appropriate behaviour, and reinforcing standards. For example, a budgeting officer noted: “effective leadership and well-defined ethical policies are essential for guiding our work,” while an officer from the transport unit reiterated: “leaders who act ethically inspire confidence and accountability among staff.” These perspectives affirm the well-established understanding that good leadership fosters an ethical culture. Where leaders demonstrate integrity, transparency and consistency, staff are more likely to align with those values in their daily responsibilities.

In addition to leadership, organisational culture – particularly norms around communication and accountability – was highlighted as a major determinant of ethical practice. Respondents from the administration and works departments expressed concerns about barriers to cooperation and information sharing, which could obscure ethical problems or delay their resolution. They noted that siloed structures and poor collaboration often contribute to ethical ambiguities and complicated decision-making processes. Transparent communication and cross-functional engagement were described as critical for ethical responsiveness.

The roles of training and professional development were also highlighted. A budget officer stressed: “regular ethics training is essential to keep pace with changing standards and regulations,” while a procurement officer added: “More frequent training programmes should be organised.” These reflections reinforce earlier themes and point to the need for institutionalised, adaptive learning systems that respond to the dynamic nature of ethical challenges in the public sector.

External influences, particularly political interference and resource constraints, were repeatedly cited as major obstacles to ethical conduct. An internal audit officer highlighted “political interference and limited resources” while a budgeting staff member referred to “pressure to manipulate reports”. These remarks underscore the complexity of ethical decision-making in public services, where informal power dynamics or structural limitations may undermine formal policies. Even well-intentioned staff may find it difficult to uphold ethical standards without institutional protection or support.

Finally, participants highlighted the importance of personal integrity and professional responsibility. A respondent from the audit unit explained that these character traits “ensure confidentiality and professional due care” underscoring the role of individual ethical commitment as a safeguard, especially when institutional protections are weak or ambiguous.

Overall, this theme illustrates that the complex interplay of leadership, organisational systems, external pressures and personal values shapes ethical practices in local government accounting. Strengthening ethical conduct requires a holistic strategy that addresses structural weaknesses, fosters ethical leadership, and empowers staff through training, communication and institutional support.

Public trust and accountability in local government accounting

The findings revealed a strong consensus among participants that ethical behaviour in local government accounting is inextricably linked to public trust and accountability. Ethical conduct was described as a professional obligation and a moral and civic duty essential to good governance and citizen confidence in public institutions.

Respondents from the budget and internal audit departments emphasised that ethical practices directly enhance service delivery and institutional credibility. An internal audit officer explained: “Very important for accountability and service delivery” highlighting how transparent financial management fosters efficiency and responsiveness in government operations. Similarly, a budget officer observed: “Ethical behaviour builds public confidence in local governance” clarifying the connection between ethical integrity and public perception. These reflections align with broader governance literature, which suggests that trust in public institutions is shaped not only by the quality of services delivered but also by how fairly, transparently and accountably they are administered.

All participants viewed accountants as stewards of public resources, whose actions send powerful signals to the public regarding government intentions. This was emphasised by an internal auditor, who stated that ensuring “funds are used for intended purposes” is essential, underscoring how ethical financial reporting affirms the government’s commitment to the responsible use of taxpayer money. In this light, ethical lapses are not merely technical failures but are perceived as breaches of public trust.

The respondents further identified accountability mechanisms such as internal audits, transparent procurement processes and citizen-facing reporting as vital for safeguarding integrity and reinforcing public confidence in public institutions. A procurement officer noted: “Accountability and transparency are vital for maintaining faith in the system,” while a budget officer noted that this approach “positively influences public trust by demonstrating accountability”. These statements underscore that public trust is not passively awarded but must be built through visible, responsible and verifiable governance practices.

At the same time, respondents acknowledged that, despite their best intentions, external influences continue to challenge ethical governance. A budgeting officer pointed to “political pressure and circumvention by suppliers” as factors that compromise the integrity of financial systems and weaken public confidence. If unaddressed, such external threats create perceptions of impunity, corruption or favouritism, thereby eroding the trust necessary for effective governance.

In summary, participants across audit, budgeting and procurement were clear that public trust is both a consequence and a reflection of ethical governance. Maintaining it requires strict adherence to codes of conduct, sound accounting procedures, visible mechanisms of accountability, firm resistance to political interference, and a culture of integrity that permeates the entire institution. When these elements are in place, ethical financial management becomes the platform for democratic legitimacy and sustainable local development.

Ethical conduct through the lens of Rest’s four-component model

To deepen the researchers’ understanding of staff perspectives on ethical behaviour in local government accounting, the study findings were analysed through the lens of Rest’s four-component model of ethical decision-making. As noted above, the model comprises four key stages: moral awareness, moral judgement, moral intent and moral action. This framework revealed a nuanced picture in which staff members generally exhibit high ethical awareness and intent but struggle with judgement and action due to contextual constraints.

Moral awareness: Respondents across procurement, budget and internal audit units demonstrated a clear understanding that ethical responsibilities are central to their roles, and that deviations have tangible implications for both governance and public trust. However, a budget officer noted that “the level of understanding of ethical principles differ significantly among staff” suggesting that although awareness exists, it is unevenly distributed across departments. Similarly, audit staff highlighted instances of unauthorised payments, while a budgeting officer pointed to irregular procurement requests, indicating that moral sensitivity is present but constrained by inconsistent training and weak communication channels.

Moral judgement: The ability to critically evaluate ethical issues and determine the most appropriate course of action varied significantly across the respondents. As a budget officer remarked: “Some staff are able to critically assess the ethical implications while others struggle to articulate what constitutes an ethical issue.” By contrast, administration staff admitted limited exposure to complex ethical dilemmas which restricted their judgement capacity. These differences reveal that while moral awareness is fairly widespread, moral reasoning skills are uneven and require targeted capacity-building.

Moral intent: Staff across the budget, procurement, internal audit and works departments generally expressed a desire to uphold ethical standards even under pressure. A budget officer explained: “We want to do the right thing, but often the pressure of the job makes it difficult to follow through on ethical decisions.” Respondents cited factors such as political interference (budgeting officer), fear of reprisal (internal audit officer), and heavy workloads (procurement officer) as obstacles that weaken their ability to translate ethical intent into action. This illustrates the disjunction between individual commitment and organisational realities, highlighting the need for institutional support to bridge this gap.

Moral action: Barriers to acting ethically were most strongly reported by internal auditors and transport officers, who described situations where structural and procedural gaps blocked ethical responses. As one auditor explained: “Even when we know the right thing, the lack of support in procedures makes it challenging to act ethically.” Transport staff similarly noted the absence of “formal reporting mechanisms to escalate ethical breaches”. Across both groups, the lack of whistleblower protections and supportive leadership structures left staff vulnerable or isolated when confronting misconduct.

Discussion

This study makes a substantive contribution to the ongoing discourse on ethical standards in local government accounting by affirming prevailing scholarly perspectives and introducing new empirical insights rooted in the lived experiences of public officials. It thus provides a deeper, context-specific understanding of how ethical standards are perceived, enacted and challenged within Ghana’s local governance structure.

The findings strongly affirm the centrality of ethical behaviour as a prerequisite for maintaining public trust in government institutions. This aligns with Adams and Gibbon (2018), who argue that ethical conduct is not merely an abstract ideal, but also a practical requirement for administrative legitimacy. Procurement and budget department participants’ views, such as the emphasis on ensuring that “funds are used for intended purposes”, demonstrate how ethical practice is intrinsically linked to the public’s perception of government credibility. These insights reinforce the idea that ethical integrity in financial management plays a critical role in sustaining citizens’ confidence and enabling effective service delivery at the local level.

Although Hurtado-Guevara et al. (2024) stress institutional frameworks as the main factor influencing ethical behaviour, the KNMA case reveals several other barriers. Staff across departments highlighted poor communication, fragmented supervision and limited ethics training as key obstacles to ethical behaviour. These findings suggest that ethical compliance cannot be assured by formal policies alone; rather, it must be nurtured through enabling organisational culture, consistent leadership and ongoing ethics education. This challenges the traditional institutionalist view and invites a more integrated ethical governance model that balances rules with culture and practice.

Building on Azeez’s (2024) framing of transparency and accountability as cornerstones of local governance, this study introduced ethical awareness as a critical antecedent to accountability. Participants from the procurement, budgeting, works and transport departments expressed varying levels of understanding of ethical obligations, which contributed to inconsistencies in financial oversight and decision-making. These findings underscore that formal accountability mechanisms are only as effective as individuals’ ethical consciousness in operating them. By situating ethical literacy as central to accountability, this study calls for a shift in policy focus from compliance-based reform to capacity-building in ethical reasoning and practice.

This study also contributes empirical support to the call by Barker and White (2020) for greater investment in ethics training in public sector accounting. The testimonies of participants from the budgeting, works and transport units highlight a strong demand for “more frequent training”, and training which is both context-specific and reflective of real-world dilemmas. The desire for continuous learning highlights the need for training programmes that go beyond static codes of conduct to include scenario-based learning, reflective practice, and peer accountability mechanisms. These insights provide actionable guidance for integrating ethics more systematically into public service training curricula and professional development plans.

A distinctive contribution of this study lies in its focus on the contextual complexities of ethical behaviour in resource-constrained and politically charged environments. Participants from budget, works and internal audit units shared vivid examples of ethical dilemmas, such as the pressure to authorise unauthorised payments or circumvent standard procurement procedures, which highlight the routine nature of moral tension in local governments. These narratives enrich the literature by grounding ethical discourse in the social and political realities of local administration, an area often overlooked in abstract or global frameworks. This underscores the importance of developing ethical guidelines and interventions that are sensitive to local dynamics and administrative culture.

Finally, the study makes an important contribution to the theoretical discourse by applying and critically reflecting on Rest’s four-component model of ethical decision-making within a public sector context in the Global South. The findings suggest that while moral awareness and intent are generally present among staff, moral judgement and action are frequently hindered by institutional constraints such as fear of retaliation, unclear reporting channels, or lack of leadership support. This illustrates the limitations of Rest’s model when applied without sufficient consideration of organisational and contextual factors. By highlighting the structural conditions that prevent staff from acting ethically, even when they recognise and intend to do so, this study invites future scholars to expand the model to account more explicitly for the mediating role of organisational culture, power dynamics, and administrative support.

Conclusion and implications for practice and research

This study explored the perceptions of local government staff regarding the ethical conduct of accountants within the KNMA, offering important empirical insights into how ethical awareness, judgement and action are shaped by institutional reality. Central to this study is the recognition that ethical awareness varies considerably across departments, a disparity that impedes the development of consistent accountability practices. The data revealed that while participants generally recognised the importance of ethical conduct, many also expressed concern over the inadequacy of current ethics training, the absence of reinforcement mechanisms, and the limited support systems available to staff seeking to uphold ethical standards. This suggests that structural compliance alone is insufficient to promote ethical behaviour. Instead, a deliberate effort to build a values-based organisational culture that prioritises ethical learning, supports moral reasoning and reinforces ethical action is necessary.

Applying Rest’s four-component model helped explain how ethical behaviour unfolds in local governance. While staff showed awareness and intent, they struggled at the judgement and action stages due to weak leadership, poor communication, and unclear procedures. This extends Rest’s model by highlighting the role of organisational dynamics in shaping ethical decisions. This contextualised application of the model reveals that individual ethical capacity must be matched by institutional readiness if ethical action is to be sustained.

This study also contributes to the broader discourse on ethical training in public administration. All participants strongly advocated for more frequent, context-specific and structured ethics training, which reinforces the idea that ethical competence must be cultivated continuously rather than being assumed or front-loaded at entry points. The call for ongoing capacity-building and the integration of ethics into both formal training and workplace culture reflects the growing recognition that ethical behaviour must be embedded holistically within public institutions.

Simultaneously, the findings illuminate the fragile nature of ethical behaviour in environments where political interference, operational opacity, and leadership ambivalence create conditions of ethical vulnerability. Participants’ accounts of external pressures and procedural breakdowns illustrate that, without institutional safeguards, even well-intentioned actors may struggle to translate ethical awareness into ethical actions. This highlights the need for local government institutions to move beyond symbolic adherence to ethics and towards the development of systems that enable and protect ethical decision-making at all levels.

While the study is situated within the specific institutional and socio-cultural context of the KNMA, its findings offer insights that may be transferable to other settings where public sector accountability and ethical practice are subject to comparable pressures. As with all qualitative studies, the findings are interpretive and context-bound, rather than predictive or universally representative. They should be read as a lens through which to understand the lived realities of ethical conduct in local governments, not as a claim to statistical generalisation. Future research may build on this foundation by examining similar dynamics in other municipal contexts, exploring cross-cultural comparisons, or adopting longitudinal designs to assess how ethical practices evolve over time and under various institutional reforms. By deepening our contextual understanding of how ethical standards are enacted, constrained and potentially transformed, such research can help to inform ongoing efforts to strengthen accountability and integrity in public governance.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship or publication of this article.

References

Adams, R. and Gibbon, A. (2018) Ethical issues in the public sector and their impact on public welfare. Public Administration Review, 78 (3), 456–468.

Amrizal, M. (2018) The impact of ethical violations on the public’s trust in accountants. Journal of Accounting and Public Trust, 24 (1), 45–58.

Audit Service of Ghana. (2022) Report of the Auditor-General on the management and utilisation of District Assemblies Common Fund. Accra, Ghana: Audit Service of Ghana.

Ayee, J.R.A. (2001) Civil service reform in Ghana: A case study. Accra, Ghana: African Centre for Economic Transformation. https://doi.org/10.4314/ajps.v6i1.27319

Ayee, J.R.A. (2019) The politics of decentralization in Ghana’s fourth republic. Accra: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

Azeez, A. (2024) Ethical accounting practices and the restoration of public trust in government financial reporting. International Journal of Government Accountability, 17 (3), 215–230.

Barker, R. and White, M. (2020) The international monetary and financial system. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Barrainkua, I. and Espinosa-Pike, M. (2018) The influence of auditors’ commitment to independence enforcement and firms’ ethical culture on auditors’ professional values and behaviour. In: Jefrey, C. (ed.) Research on professional responsibility and ethics in accounting. Bingley, UK: Emerald Publishing Limited, Vol. 21, pp. 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1574-076520180000021002

Blake, J. and Gowthorpe, C. (1998) Ethical dilemmas in public sector accounting: creative accounting and the role of whistleblowing. Journal of Business Ethics, 18 (4), 289–301.

Bogale, A.T. and Debela, K.L. (2024) Organizational culture: a systematic review. Cogent Business & Management, 11 (1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2024.2340129

Braun, V. and Clarke, V. (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3 (2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brown, M.E. and Treviño, L.K. (2006) Ethical leadership: a review and future directions. The Leadership Quarterly, 17 (6), 595–616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2006.10.004

Bryman, A. (2016) Social research methods. 5th ed. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

Cohen, J.R. and Pant, L.W. (1991) Beyond bean counting: establishing high ethical standards in the public accounting profession. Journal of Business Ethics, 10, 45–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00383692

Commonwealth Local Government Forum. (2022) Country profile: Ghana. Available at: https://www.clgf.org.uk/default/assets/File/Country_profiles/Ghana.pdf

Craft, J.L. and Shannon, K.R. (2025) An examination of the 2012–2022 empirical ethical decision‐making literature: a quinary review. Business Ethics: The Environment & Responsibility, 34, 701–721. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12676

Creswell, J.W. and Poth, C.N. (2017) Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Demir, T., Reddick, C.G. and Perlman, B. (2023) Ethical performance in local governments: an empirical study of organizational leadership and ethics culture. Public Administration Review, 53 (5-6). https://doi.org/10.1177/02750740231175653

DiCicco‐Bloom, B. and Crabtree, B.F. (2006) The qualitative research interview. Medical Education, 40 (4), 314–321. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02418.x

Etikan, I., Musa, S.A. and Alkassim, R.S. (2016) Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5 (1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11

García, A., Hernández, M. and Pérez, S. (2024) Ethical standards in public sector accounting: a framework for ensuring transparency and fairness. Journal of Public Finance, 34 (1), 77–92.

Ghana Districts. (2023) Kassena-Nankana municipal assembly profile. Available at: http://www.ghanadistricts.com

Ghana Statistical Service. (2021) 2021 Population and housing census: regional report – Upper East Region. Accra, Ghana: Ghana Statistical Service.

Gill, P., Stewart, K., Treasure, E. and Chadwick, B. (2008) Methods of data collection in qualitative research: interviews and focus groups. British Dental Journal, 204 (6), 291–295. https://doi.org/10.1038/bdj.2008.192

Guest, G., Bunce, A. and Johnson, L. (2006) How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18 (1), 59–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X05279903

Guest, G., MacQueen, K.M. and Namey, E.E. (2012) Applied thematic analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483384436

Hurtado-Guevara, R.F., López-Pérez, P.J. and Muñoz-Intriago, K.R. (2024) The role of accountants in local government: ensuring financial integrity and accountability. Humanities & Social Sciences Research Journal, 2 (3), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.70881/hnj/v2/n3/7

Institute for Democratic Governance. (2020) Decentralization and local governance in Ghana: challenges and prospects. Accra, Ghana: Institute for Democratic Governance.

Kamau, L.W. and Gakobo, J. (2024) Ethical climates and organizational performance in Cascade Premier Hotel in Kiambu County, Kenya. Journal of Business and Management Studies, 6 (2), 115–130. https://doi.org/10.61426/sjbcm.v11i1.2872

Khursheed, U., Sehar, S. and Afzal, M. (2019) Importance of ethical decision making: application of James Rest’s model. Scholars Journal of Nursing and Healthcare, 2 (12). https://doi.org/10.36348/sjnhc.2019.v02i12.007

Kvale, S. and Brinkmann, S. (2015) Interviews: learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Lawton, A. and Macaulay, M. (2004) Ethics at the crossroads? Developments in the ethics infrastructure in local government. Local Government Studies, 30 (4), 606–621. https://doi.org/10.1080/0300393042000318021

Lawton, A. and Páez, I. (2015) Developing a framework for ethical leadership. Journal of Business Ethics, 130, 639–649. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2244-2

Lestari, A. and Saud, I.M. (2024) The determinants of ethical judgments at local government agencies. SHS Web of Conferences, 201, 03003. https://doi.org/10.1051/shsconf/202420103003

Mekonnen, N. (2025) The role of ethical climate types in professional accountants’ ethical decision-making: a necessary condition analysis (NCA). Accounting Research Journal, 38 (5–6), 581–598. https://doi.org/10.1108/ARJ-01-2025-0028

Nafiisa, M., Al-Hassan, N. and Rizvi, K. (2023) Codes of ethics and their role in fostering accountability and professionalism in public sector accounting. Journal of Ethical Public Administration, 29 (4), 45–60.

Nowell, L.S., Norris, J.M., White, D.E. and Moules, N.J. (2017) Thematic analysis: striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16 (1). https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847

Palinkas, L.A., Horwitz, S.M., Green, C.A., Wisdom, J.P., Duan, N. and Hoagwood, K. (2015) Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 42 (5), 533–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y

Parmar, R. (2016) The impact of corporate scandals on public trust and ethical standards in accounting. Accounting Ethics Journal, 15 (4), 350–365.

Procópio, L.M. (2019) Moral standards in managerial decisions: in search of a comprehensive theoretical framework. Business Ethics: A European Review, 28 (2), 261–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12216

Rogers, J. and Breakey, H. (2023) James Rest’s Four Component Model (FCM): a case for its central place in legal ethics. In: Webb, J. (ed.) Leading works in legal ethics. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003015093-14

Shree, C.C. (2024) Ethical issues in accounting: a comprehensive review and analysis. International Journal for Multidisciplinary Research (IJFMR). https://www.ijfmr.com/papers/2024/1/13612.pdf

Temitayo, O.J., Noluthando, Z.M. and Titilola, O.J. (2024) The role of ethical practices in accounting: a review of corporate governance and compliance trends. Finance & Accounting Research Journal, 6 (4), 707–720. https://doi.org/10.51594/farj.v6i4.1070

Victor, B. and Cullen, J.B. (1988) The organizational bases of ethical work climates. Administrative Science Quarterly, 33 (1), 101–125. https://doi.org/10.2307/2392857

Widyawati, A. and Saud, H. (2015) Perceptions of ethical standards among accountants, educators, and students. Journal of Accounting Education, 12 (2), 56–67.

Yin, R.K. (2018) Case study research and applications: design and methods. 6th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Zimmerman, J. (2016) Ethical dilemmas in public service: conflicts of interest and abuses of authority. Public Service Ethics, 27 (5), 450–465.