Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance

Issue 30

December 2025

RESEARCH AND EVALUATION (PEER REVIEWED)

Governance Dynamics for Balancing Authority and Efficiency: Assessing the Efficacy of Ghana’s Decentralisation Programme

Institute of Local Government Studies, Tamale Campus, Ghana, radamteysekade@gmail.com, ronald.adamtey@ilgs.edu.gh

Institute of Local Government Studies, Tamale Campus, Ghana, hawamahama@gmail.com, hawa.mahama@ilgs.edu.gh

Abdul-Moomen Salia

Institute of Local Government Studies, Tamale Campus, Ghana, salia.abdulmoomen@gmail.com, salia.abdulmoomen@ilgs.edu.gh

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/6npx0m66

Article History: Received 09/01/2025; Accepted 09/09/2025; Published 31/12/2025

Citation: Adamtey, R., Mahama, H., Salia, A.-M. 2025. Governance Dynamics for Balancing Authority and Efficiency: Assessing the Efficacy of Ghana’s Decentralisation Programme. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, 30, 24–40. https://doi.org/10.5130/6npx0m66

© 2025 by the author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercial, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Abstract

A balanced approach to allocating authority is a cornerstone of decentralisation. However, in the Ghanaian context questions remain as to whether the centre is ready to share authority, and whether local authorities have the capacity to wield it effectively. This study sought to answer these questions, using a combination of in-depth interviews with 133 key actors in the decentralisation process and content analysis of relevant laws. Troublingly, it found both structural and practical obstacles which prevent decentralisation in Ghana from flourishing. Following analysis of the findings, the authors recommend several measures to improve the position: clear commitment on the part of the centre; implementing full fiscal decentralisation; strengthening the capacity of local government functionaries; more awareness-raising campaigns to promote citizen engagement; making the planning process responsive to local needs; and strengthening horizontal coordination and collaboration.

Keywords

Balanced Authority; Decentralisation; District Assembly; Governance Dynamics; Ghana

Introduction

Governance dynamics is a research area which looks at how institutions and systems interact in a decision-making environment. It focuses on decision logic by analysing the factors that influence the behaviour of actors in the governance environment, the choices they opt for regarding a particular development issue, and the kind of development outcomes that such interactions produce.

We can conceptualise this interaction as a game where decisions made by the actors individually and jointly impact their own interests and those of others. Players in the game of governance are mainly public officers and leaders of civil society groups, many of whom have the authority to represent constituencies of ordinary people. It is generally seen as advisable that this authority be legitimately granted to the actors in the game by their constituencies. Governance dynamics is rooted in Nash equilibrium theory (Duffy 2015; Flores 2019), a decision-making theory which holds that players in a game have the best chance of achieving their desired outcome by not deviating from their initial strategy. In the Nash equilibrium, each player’s strategy is optimal when it is selected after considering the decisions of other players. Every player wins because everyone gets their desired outcome (Duffy 2015; Flores 2019; Rana 2019). Following from Nash equilibrium theory, the term ‘governance dynamics’ is used in this paper to mean the relationship between central government and local government authorities in the context of Ghana’s decentralisation programme (Republic of Ghana 2016a).

The concept of ‘authority’ has varied interpretations, but there is some consensus that it refers to a legal and formal right to give commands and make decisions (Williams 1968; Laski 2000; Hershovitz 2011). In the context of Ghana’s decentralisation reforms as provided for by Ghana’s 1992 Constitution, authority is given to local government authorities (metropolitan, municipal and district assemblies) (all referred to as district assemblies (DAs) in this paper) by Article 240 (1) of the 1992 Constitution and the Local Governance Act 2016 (Act 936) to exercise the highest political authority at the district level. Ghana’s DAs are mandated to 1) exercise political and administrative authority in the district, 2) promote local economic development, and 3) provide guidance, give direction to and supervise other administrative authorities in the district (Republic of Ghana 1992, 2016a, 2016b). Article 240(1) of the 1992 Constitution, together with the Local Governance Act 2016, establishes the relationship between the central government (referred to as the ‘centre’ in this paper) and the DAs. Authority within this relationship needs to be effectively balanced to make the decentralisation process work.

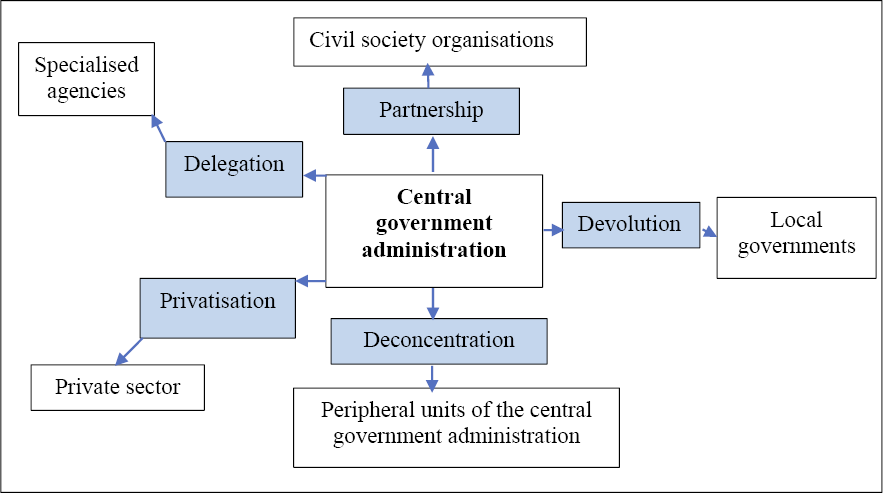

This paper uses the phrase ‘well-balanced authority’ to mean that DAs and other actors at the district level have sufficient human, technical and financial capacity, together with legal and formal right to direct local-level affairs and make decisions; and that their work is endorsed by the participation of highly aware citizens. This approach echoes many other central government relationships; for example those with peripheral central government units and their deconcentrated mandate, with the private sector as it takes on certain aspects of public service delivery, with specialised agencies that are given delegated functions, and with civil society organisations (CSOs), non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and development partners that work with central government (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Relationship between central government and peripheral central government units

Source: Authors’ construct, July 2025

For efficient public service delivery, the various actors in the decentralisation system must deliver public services with an optimal balance of expenditure of financial resources, time and effort (UNDESA, UNDP and UNESCO 2012; Spours 2020). Thus, in the context of this paper, services such as health, education and water need to be delivered to Ghanaians at the local level in the right quality and quantity, and at the right time. Achieving this will require effectively balancing authority between the centre and the peripheries, since the DAs and other actors such as the private sector, CSOs and specialised agencies are closer to the people and have a better understanding of their development needs (Institute of Local Government Studies and Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung 2010; Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development 2014). As discussed in a later section, the saints, wizards and systems must be present and the demons need to be cast out for a well-balanced authority to work (Ayee 2000).

Balancing authority is laudable as it can help achieve efficiency. A number of questions are however not sufficiently answered in Ghana’s current decentralisation literature. Has the centre demonstrated sufficient commitment to sharing authority? Is there sufficient technical, human and fiscal capacity at the local level to work with the authority if balanced? Given the diversity of actors at the local level, do we have the required collaboration and coordination between them? And do we have highly aware citizens at the local level able to actively participate in the governance process and hold service providers and government bureaucrats to account?

The argument of this paper is that although decentralisation is a viable approach to securing grassroots participation in decision-making (Ato-Arthur 2012, p. 225) and balancing authority has the promise to improve decentralised governance and service delivery, it cannot work effectively until these critical questions are answered positively.

These questions are therefore the focus of this paper, which looks at the relationship between the centre and the periphery, ie between the central government and the DAs. It is organised into seven main sections.

Section one is the introduction followed by the study context in section two. The literature underpinning the study is in section three. Section four presents the methodology, while the findings and discussions, conclusions and recommendations are in sections five, six and seven respectively.

Study context – decentralisation in Ghana and the need for balancing authority

The DA system was introduced in Ghana in 1988 after about two decades of military rule. In 1992 a new constitution came into force, crystallising the decentralisation agenda by making DAs the highest political authority at the district level (Republic of Ghana 1992, 2016a). The DAs have since become the epicentres of local-level development decision-making, rooted in district development plans and budgets. The law requires DAs to ensure effective mobilisation and utilisation of human, physical and financial resource – partly through the levying and collection of taxes, rates, duties and fees – to implement their plans for economic and social development. Responsibilities include the provision of basic infrastructure, municipal works and services; development, improvement and management of human settlements; and the maintenance of security and public safety (Republic of Ghana 2016a).

DAs operate with a devolved mandate, but the president appoints a representative to head each DA as the district chief executive (DCE). This appointment requires prior approval of two-thirds of DA members present and voting. In addition, the president appoints 30% of the members of the DA in consultation with traditional authorities and other interest groups, while the local people elect the other 70% on a non-partisan basis. Some commentators claim that in practice all appointees are party favourites of the president, and have called for all DCEs and DA members to be elected (Gyampo 2008; Antwi-Boasiako 2010; Afrobarometer 2017; Sanja 2019).

DCEs are responsible for the day-to-day performance of their DA, as well as the supervision of DA departments. The head of the government bureaucracy is the district coordinating director. He or she is answerable to the DCE, and their chief task is coordination of the activities of the DA departments.

However, evidence suggests that many DAs are not performing as expected, for a number of reasons.

Balancing authority in the lens of ‘saints, wizards, demons’ and systems characterisation

The characterisation of policy actors as either saints, wizards or demons and the policy-making environment as a set of systems emerged in the 1990s. It has been used by scholars such as Peterson (1998), who was the originator, Ayee (2000) and Amanor-Lartey (2019) to analyse policy-making and implementation challenges in developing countries. For example, in the Ghanaian context Ayee (2000) analysed the quality and roles of the various actors in public policy implementation, and more recently Amanor-Lartey (2019) explored the dynamics of this implementation. Essentially, the characterisation is a powerful way to analyse the factors that explain the success or otherwise of public bureaucrats.

According to this approach, the politicians and bureaucrats in government with genuine intention to work hard to successfully implement public policies are the saints. Among other qualities, the saints need to be competent, open-minded, progressive, and ready to embrace innovation and change; have the political will to implement public policy as designed and intended, and take the risks needed to achieve policy goals; and provide a clear vision, direction and sense of purpose for other agents to follow (Ayee 2000). What this suggests is that we must have public leaders who will behave like the saints at both national and local level in order for balancing authority to work in the frame of Nash equilibrium.

Working alongside the saints, those technocratic officials who engage in policy analysis employing reliable and trustworthy data and maintaining professional integrity and ethics in their decision-making are the wizards (Ayee 2000). They help protect the resilience of the system and mobilise the resources needed for successful policy implementation. While supporting the saints in management activities, their main role is organisational improvement. In the context of Ghana’s decentralisation environment, departmental heads and other technical advisors at the local level fall in this category as they have the technical capacity to provide much-needed support to the saints.

Falling in the category of demons are any antagonistic, lethargic or treacherous politicians and bureaucrats in the policy environment. They undermine the saints and wizards by their actions, making it difficult for the saints and wizards to deliver. They are interested in personal gain not public good, and they seek this through corrupt practices such as bribery, cronyism, fraud and embezzlement. In the case of Ghana, there is huge evidence that many demons are present, as the country still suffers from high corruption and low transparency, and this is especially the case within DAs (Armah-Attoh et al. 2014; Auditor General 2021).

The socio-economic, cultural and political environment in which public policy is designed and implemented constitutes the system. The ways in which actors influence and shape policy determine the extent to which public policy will succeed or fail. This implies that infrastructure to support citizens’ engagement with the state should be fully developed, to promote public accountability. Information access is key – however, currently the necessary infrastructure for the dissemination of information, such as internet and intranet connectivity, is weak in many districts (Media Foundation for West Africa 2019).

Research methodology

This paper is based on qualitative evidence gathered from in-depth face-to-face interviews with purposively selected key informants at both national and local levels. A total of 133 interviews took place from July to September 2024. At the national level, the authors interviewed ten high-profile public officers in the then Ministry of Local Government Decentralisation and Rural Development (MLGRD), now Ministry of Local Government, Chieftaincy and Religious Affairs, together with ten of their counterparts at the Office of the Head of the Local Government Service, and five senior active politicians with expertise in decentralisation and local governance. At the local level, the researchers divided Ghana into three main zones – northern, middle and southern – and used the lottery method to select one DA from each zone. For each DA selected, the DCE (politician), district coordinating director (bureaucrat) and budget officer, planning officer and finance officer (technocrats) were interviewed. For each DA the presiding member and up to a quarter of assembly members were also randomly selected for interviews. Up to five key senior officers of the decentralised departments with deconcentrated mandates in the selected DAs were also randomly selected for interviews. The next group of interviewees were up to five leaders of NGOs and CSOs recognised by the DA as working in the district. Finally, in-depth interviews were held with five Ghanaian seasoned scholars and ten retired politicians who have shaped the design and implementation of Ghana’s decentralisation reforms and continue to influence implementation.

Interviews explored the following questions:

1. Is there sufficient evidence to conclude that the centre is fully committed to balancing authority with the periphery?

2. Is there sufficient technical/human/fiscal resource capacity at local level to support well-balanced authority?

3. Is there the required collaboration among actors at the local level?

4. Is there sufficient awareness among citizens to hold local public officers to account?

The NVivo software (version 20) was used to analyse the interviews.

Analysis of the qualitative data was supported by content analysis of relevant parts of the following legislation: the 1992 Fourth Republican Constitution of Ghana; the Local Governance Act 2016 (Act 936); the Local Governance (Amendment) Act, 2017 (Act 940); and Legislative Instrument LI 1967 (Republic of Ghana 2010, 2017).

Findings and discussion

The study revealed that, in the case of Ghana’s DAs, neither saints, wizards nor systems are present in the required quantities – but unfortunately there are numerous demons undermining performance. Many actors have drastically shifted their stated or legally mandated positions, thereby destabilising the Nash equilibrium. This paper will discuss findings relating to each research question in turn.

Is the centre fully committed to balancing authority?

The findings suggest that although the central government has taken some bold policy steps to balance authority with local-level actors, about 90% of interviewees across all categories feel the commitment is insufficient. The steps taken by government were well outlined by two national-level interviewees:

Among the key policies supporting decentralisation in balancing authority are that government has introduced systems and structures to improve transparency and accountability in the management of public funds. The passage of the Public Financial Management Act 2016 (Act 921) and the Public Procurement (Amendment) Act 2016 (Act 914) provide additional instruments to ensure financial integrity in the system. Also, in 2018, the Fiscal Responsibility Act was passed to enhance prudent macroeconomic management and debt sustainability (Key informant, MLGRD, August 2024).

and:

The creation of specialised institutions such as the establishment of the Institute of Local Government Studies (ILGS) by the Institute of Local Government Studies Act 2003 (Act 647) to train staff and members of local government authorities towards operational efficiency is in the right direction. The establishment of the Inter-Ministerial Coordinating Committee on Decentralisation to provide expert advice to the president and the recent call by the president to build a national consensus on the amendment of articles 55(3) and 243(1) of the 1992 Constitution to make it possible for the election of DCEs is also a welcome idea (Retired high-profile politician, August 2024).

However, despite the initiatives cited above, over 90% of local-level bureaucrats and technocrats feel more is needed from central government, and that commitment by the centre to share authority is weak. These respondents expressed concern over Article 240 (1) of the 1992 Constitution, which states that “Ghana shall have a system of local government and administration which shall, as far as practicable, be decentralised” (Republic of Ghana 1992, p. 150) [emphasis added]. This suggests there are limits to Ghana’s decentralisation, and many respondents felt the phrase “as far as practicable” facilitates the concentration of authority at the centre.1

Perhaps this is why, for example, fiscal decentralisation has not been fully completed. Central government appears to give out authority with one hand and retake it with the other hand (Ayee 2008). As evidence, local-level politicians, bureaucrats and technocrats cited the recentralisation of the District Assemblies Common Fund Responsiveness Factor Grant (DACF-RFG), expressed by one respondent in this way:

The DACF-RFG was created to encourage local governance: to deepen government’s commitment to decentralisation in particular and promote sustainable self-help development; complement the internally generated funds of the DAs to undertake development projects; ensure equitable distribution of development resources in every part of Ghana; make up for development deficiencies in deprived communities; and support creation and improvement of socio-economic infrastructure. Yet in terms of the disbursement of the DACF-RFG, the District Assemblies Common Fund Act 1993 (Act 455) does not give us wide room to determine its usage as a huge component is beyond our determination with huge deductions at source. In the end we receive far less than we need (High-profile local politician, July 2024).

As well as the limited room given to local-level officials to determine use of the DACF-RFG, local-level politicians and bureaucrats were also concerned about other aspects of the DACF law, suggesting it facilitated recentralisation of power. For example, the law provides for the Minister for Finance and Economic Planning, in consultation with the Minister for Local Government and Rural Development, to determine categories of expenditure at DAs and also their approved development budget – effectively dictating how DAs spend much of their DACF grant (Republic of Ghana 2014, p. 20). This suggests that those who drafted, and voted through, the DACF law may not have been genuine ‘saints’, as the law appears to give undue control to the centre.

Another major concern of local-level officials is the many deductions at source from the DAs’ share of the DACF-RFG – for which no receipts are issued by the administrator of the fund. This contravenes the regulations on the administration of the DACF-RFG. One respondent noted that:

Many have the view that the absence of receipts from the administrator of the DACF-RFG could cast doubts about the intended purposes of the deductions. Further, this could result in understatement of receipts from the DACF-RFG Secretariat and can affect the assembly’s cash flow position and undermine the fulfilment of the development agenda as the DAs have to rely on net receipts to develop the same services for which the deductions were made (Retired senior politician, July 2024).

Furthermore, respondents noted that the administrator of the fund does not give advance notification of the at-source deductions, which would enable the DAs to factor them into their supplementary budgets (see for example Audit Service 2021, NR/LA/DC/2/Vol. 1/12). This point was corroborated by national-level respondents and also by Ghana’s Audit Service. The situation is worsened by delays in the release of transfer funds – often several quarters behind schedule.

The voting and appointment system for DCE members was, according to nearly all respondents, further evidence of an absence of genuine saints and resilient systems at the centre. Although Section 20(1) of Act 936 provides for DCEs to be appointed by the president with the prior approval of not less than a two-thirds majority of DA members present and voting, this system is frequently manipulated.

This respondent’s view was generally representative:

It is worth mentioning that one-third of the members of the assembly is supposed to be appointed by the president in consultation with traditional authorities and other interest groups in the district; but it is common knowledge that in most cases the appointment is done through the political party structures sending party faithful into the assembly. It is also common knowledge that in spite of the fact that Section 5(1)(b) of Act 936 provides for the election of 70% of the members of the assembly through universal adult suffrage, the election is highly partisan with the incumbent government sponsoring candidates to get to the assembly. What this implies is that chances are high for whoever is elected as presiding member to be a member of the incumbent government party. In addition to this, the chairperson of the executive committee of the assembly is the DCE. With the 30% being party members and a good number of the elected aligned to the incumbent DCE, it is obvious that proper accountability cannot be guaranteed (Respondent at district level, July 2024).

Local officers also raised concerns about Sections 37(1) and 37(2) of Act 925, claiming that they suggest the centre does not fully support a well-balanced authority. Section 37(1) states that the DCE shall be the chairperson of the District Spatial Planning Committee, and in their absence the district coordinating director shall act as chairperson (Republic of Ghana 2016a). Respondents reported that DCEs were frequently away, but were often unwilling to allow their coordinating directors to act. This slowed down the work of what is a critical committee for ensuring that local physical development is carried out in accordance with the law.

Another issue raised by a senior scholar in Ghana’s decentralisation, and corroborated by all the retired politicians, is that decentralisation laws can conflict with other laws. It was noted that:

One example of such conflict and ambiguity can be found between the Local Governance Act 2016 (Act 936) and the Ghana Health Service and Teaching Hospitals Act 1996 (Act 525). In accordance with the local government system, Section 3(2) states that the district assembly shall constitute the highest political authority in the district. In practice, however, this does not seem to be the case especially with healthcare decentralisation (Senior scholar in decentralisation, July 2024).

In principle, the district health director should be under the authority of the DCE – yet postholders appear to be closer to the regional director of health services (a central government employee). Health departments tend to be strongly aligned to the parent ministry, and the dual reporting system has contributed to undermining trust between DCEs and health directors (Ghana Health Service 2004).

Is there sufficient technical/human/fiscal resource capacity at local level to support a well-balanced authority?

Findings from the interviews suggest that the answer to this question is ‘No’. It appears that the saints have not passed the test and the wizards are still in training – and all are operating within a wobbly system. In the policy design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation environment at the local level, there is a complex web of actors – yet there exist capacity deficiencies (ILGS 2021, 2022; Commonwealth Local Government Forum 2022).

This finding is supported by the Auditor General’s recent report:

The many unresolved issues regarding the utilisation of the DACF-RFG identified by the Auditor General have been attributed to deficiencies in internal controls in the operations of the Assemblies. Irregularities such as non-compliance with existing legislative frameworks and instruments, managerial lapses and weak monitoring procedures are prevalent at the Assemblies. There are issues with human capacity and competence gaps in the areas of planning and budgeting at the Assemblies. This has led to the initiation of new projects whilst ongoing ones have not been completed, spreading their limited resources inefficiently causing projects to be abandoned or delayed. Some projects are not planned to include all ancillary amenities such as furniture, utilities and washrooms. Such projects may be completed but cannot be put to use (Auditor General 2021).

In the saints, wizards, demons and systems model (Ayee 2000), it is noted that strong internal controls (systems) are needed to make the saints do the right thing by avoiding irregularities and complying with legislative frameworks and instruments. In addition, budget and planning officers (wizards) need to be on top of their jobs so that value for money is achieved for all expenditures and development decision-making.

However, this study found evidence of both weak human resource capacity at DA level, and limited application of modern technology to streamline operations. For example, budgeting, planning and revenue mobilisation are all mostly done manually. As one technocrat explained (a view supported by both national and local politicians):

We do not have reliable internet services. We use our own resources to buy data to work so we are unable to work well. We also do not have modern computers so we are all forced to use our personal laptops and, in most cases, virus attacks and other issues render our laptops unusable all undermining our work (Budget officer, August 2024).

Another officer noted that:

We do not have reliable data on revenue sources to enable us to project and collect the much-needed internal revenues. For example, we do not know the number of new houses coming up to collect property rate as many of the developments are not captured in our records either due to development control weakness or non-compliance on the part of the developers to acquire the appropriate development permits (Physical planning officer, August 2024).

Claims of this nature were common in all the DAs studied. Bureaucrats at the centre, the retired politicians and the academics interviewed all corroborated these claims.

As the above quotes show, weak systems severely inhibit local revenue mobilisation, meaning DAs cannot deliver on their mandates. It is worth noting that for many DAs this problem is so extreme that they rely heavily on central government transfers, especially the DACF-RFG and other earmarked funds, for their recurrent expenditure (Auditor General 2021). For example, when a donor-funded project ends, its sustainability typically cannot be assured.

These weak local systems reinforce central government control over the DAs and may strengthen a determination to recentralise power. As noted by the Media Foundation for West Africa (2019), if DAs cannot raise sufficient local revenues to fund activities that engage the ordinary citizen then how can they escape the grip of central government controls?

Is there the required collaboration among actors at the local level?

This study found poor collaboration and coordination among decentralised agencies at the local level – further supporting the hypothesis that Ghana’s systems are too weak to support a well-balanced authority. The relationship between the Health Directorate and the DA discussed above is a case in point, showing that coordination on the ground is lacking or weak. A review of intergovernmental fiscal transfer systems in 2014 (which have been in existence for more than a decade since 2014) also revealed worrying gaps in collaboration between the district health offices and the DAs in relation to health delivery. The review (Republic of Ghana 2014, p. 99) noted that:

The Ghana Health Service operates a deconcentration system of decentralisation instead of a devolved system as envisaged by the decentralisation concept. This implies that the District Health systems largely operate outside the DA structure. The consequences are that there is weak communication between the health team and the DA; health teams do not provide adequate financial information to DAs to promote transparency and accountability; and are unable to fully access health expenditure components of District Assembly Common Fund allocations.

This study found similar issues in relation to the work of many development partners and NGOs in the districts. While many of them function well, they are still working in silos without proper coordination and information sharing. Some respondents suggested that this is why, in spite of various interventions by many development partners in the northern parts of Ghana, the north is still deprived, conflict-prone, underdeveloped and poor compared to other parts of the country (see, for example, the Gulf of Guinea Northern Regions Social Cohesion Project 2024).

Traditional authorities, if integrated into the system, have a huge role to play in decentralisation. Ghanaian citizens respect their traditional authorities and are more likely to comply with directives and behaviourial change requirements issued by chiefs and queen mothers, rather than government officials. However, this study found that while some traditional authorities are performing their role well, others are not. As one high-profile national respondent put it (a view supported by more than 90% of respondents):

The chiefs and queen mothers are part of the land use and development control problems we have in Ghana in recent times. Issues of land guards, resulting in many land disputes and litigation and murders, have been associated with some chiefs and traditional rulers (High-profile officer, July 2024).

Other important players in the system are religious organisations such as churches and mosques. These actors are important, yet about 90% of respondents noted that many of them are focused on profiteering from their activities.

Turning to the situation within DAs, this study’s findings also point to an absence of genuine saints and resilient systems here. All the national-level politicians and bureaucrats took the view, corroborated by Ghana’s Auditor General, that many DAs violate the laws, regulations and guidelines governing their work, and also disregard internal controls instituted to safeguard public resources (Auditor General 2021). Irregularities cited included misappropriation of funds, unaccounted funds, using public funds to pay judgement debts, overpayment of contract sums, abandoned and incomplete projects, and commissioning of unnecessary projects. It was also claimed that some DAs fail to allocate the required 2% of their DACF-RFG for the activities of sub-districts, undermining their ability to carry out duties required by law.

Is there sufficient awareness among citizens to hold local public officers to account?

Generally, political accountability requires the capacity of citizens to sanction their leaders, usually through elections. There must be a mechanism for holding an agent to account by imposing sanctions and removing decision-making power. One scholar interviewee suggested that, “While political accountability emphasises the procedural effectiveness of institutions, many Ghanaians do not sufficiently understand the concept of accountability in order to hold their leaders to account” (High-profile Ghanaian scholar, July 2024; see also Armah-Attoh et al. 2014, p. 1). This view echoes that of many scholars and governance experts, who have argued that the practice of democracy in Ghana has not progressed much beyond formal participation by voting in elections. Most Ghanaians remain inactive in the period between elections (Media Foundation for West Africa 2019, p. 2).

This study similarly found a high level of apathy among citizens at the local level. One possible reason is that many Ghanaians think their elected representatives never listen to the concerns of the ordinary Ghanaian. This has produced a culture of what the Media Foundation for West Africa (2019, p. 10) has described as “voice without accountability between citizens and governments, contributing to the relatively low level of interest among citizens in the governance process”.

The apathy may also be a result of the fact that many DAs do not sufficiently prioritise citizens’ participation in their operations, especially when setting local budgets. This was noted by more than 80% of all the local actors interviewed, and corroborated by all the national-level officials. As one respondent said:

Many DAs hardly organise public hearings as mandated by law. For example, the conduct of a public hearing as required in the preparation of the Medium-Term Development Plans is hardly organised by many DAs, mainly due to the unavailability of financial resources (High-profile national-level respondent, August 2024).

A major 2014 study (Armah-Attoh et al.) examined Ghanaian attitudes toward political accountability to assess ordinary citizens’ role in the democratic process. The study drew on evidence from Round 5 of the Afrobarometer survey regarding five key aspects of political accountability: associational activity and local political participation; citizen engagement with the state; access to information; accountability and responsibility; and perceptions of corruption. It found that associational activity and local political participation are weak at the local level, as many citizens are not willing to attend community meetings and join others to raise issues. In recent times social media has been used to make information available to a wider extent, but it has yet to be used in Ghana to hold public officials to account.

Illiteracy and poverty also prevent some citizens from holding public office holders to account. As noted by the Media Foundation for West Africa (2019, p. 12):

To be able to build a strong movement of citizens and enhance coalitions around accountability and participation, it requires having citizens who are knowledgeable and well informed on their rights and responsibilities and are able to demand for them. Unfortunately, Ghana’s relatively high level of illiteracy and poverty is a disincentive to participatory and accountable governance as the majority of the people are not well informed and empowered to be able to engage constructively with the government, especially at the local and sub-national level.

Finally, although new types of media have seen tremendous growth over the last two decades, their lack of professionalism and sharp polarisation along political lines are issues of concern. The media should in principle be neutral and objective in its presentation of public opinion and public policy, thereby creating a platform for citizens and government to engage. However, this is rarely the case. Additionally, the evidence suggests that many radio and television stations hardly prioritise local governance issues in a way that would promote citizen participation in the governance process, contributing to the general climate of apathy (Media Foundation of West Africa 2019).

Conclusions and recommendations

The concept of balancing authority has the potential to make Ghana’s decentralisation vehicle travel safely and comfortably to the expected destination, and thus achieve all the dimensions of development. However, this study finds that the roots of Ghana’s decentralisation have not penetrated deep enough into the ground for the saints, wizards and systems to be present and functional. The demons need to be cast out by committing to enforcing the law against administrative and bureaucratic behaviours and actions that can undermine the saints, wizards and systems in the decentralisation agenda.

Based on this substantial piece of qualitative research, the authors make the following recommendations:

Clear commitment on the part of the centre

Central government should deepen its commitment to balancing authority by allowing local people to elect their own DCEs. In addition, the people at the grassroots should be given the power to elect all DA members. This would require some amendments to the 1992 Constitution and the Local Governance Act 2016 (Act 936) to complete the process of devolution and make DAs truly autonomous. The amendments should also address conflicts and ambiguities existing between Act 936 and others such as Act 525, to bring all deconcentrated departments at the district level under the control of the DA.

Complete the business of decentralisation by implementing full fiscal decentralisation

Central government must complete the business of decentralisation by operationalising full fiscal decentralisation. The DAs should be given the power to decide how to use their share of the DACF. Government should be transparent with the DAs by publishing the full value of the 7.5% of national income which is set aside as the DACF-RFG. In addition, central government directives that tie the hands of the DAs and deductions at source must cease – and the administrator of the DACF-RFG should commit to regular releases of the fund every quarter as provided by law.

Strengthen the capacity of local government functionaries

Local government functionaries need to be effectively trained so they can become responsible and accountable in the performance of their duties. Notably, refresher courses in leadership and management for DCEs need to be pursued vigorously. Senior staff need to be equipped with skills to analyse, reflect and devise innovative strategies to implement programmes; and they also need to deepen their understanding of how to manage a DA. At the top, DCEs need to master executive and strategic leadership to build their confidence and capability to lead the transformation agenda at the local level. Meanwhile DA members, as potential future national politicians, need to acquire competence in representative, deliberative, legislative, executive and accountable governance.

Increase awareness campaigns for citizens on the implementation of decentralisation

The Ministry of Local Government, Chieftaincy and Religious Affairs needs to partner with the National Commission on Civic Education and the DAs to intensify awareness campaigns for citizens. Durbars and festivals of the many ethnic groups, mosques and churches should be the tools. Given the fact that many Ghanaians are highly religious, they are more likely to be receptive to ideas presented by their religious leaders. The DAs can also harness social media by regularly sharing information about what they are doing and how local people can participate in the process.

Open up the planning process to local influences

There is a need to open the planning process to local concerns and issues, making it more responsive to the local population and their distinct interests, problems and demands. This is key because the ultimate purpose of decentralisation is to locate decision-making power at the lower levels of the government hierarchy, so that local communities can generate and utilise budgets as they think best.

Strengthen horizontal coordination and collaboration

Horizontal coordination is vital for district-level planning, to take account of clusters of inter-related decisions that have an impact on the state and direction of regional development processes. Both the substantive and procedural dimensions of planning must be coordinated, and development activities must be set within a framework of common objectives for the district. Mechanisms for this coordination can include direct personal contact, coordinating committees, inter-agency task forces, staff secondments, joint workshops, standardised work procedures, and joint staff training. Each of these instruments has its own unique strengths and weaknesses. It is therefore essential that the appropriate ones are selected and applied based on local contexts.

The working relationship between central governments and local government authorities is critical for the proper functioning of any system of decentralisation. As this paper has demonstrated, the case of Ghana after over three decades of decentralisation experience rather shows poor commitment by central government to share authority with local authorities that do not even have the capacity to wield such authority effectively. The many structural and practical obstacles which prevent decentralisation in Ghana from flourishing are likely to persist in Ghana’s local governance architecture unless there is clear commitment on the part of the centre; implementing full fiscal decentralisation; strengthening the capacity of local government functionaries; more awareness-raising campaigns to promote citizen engagement; making the planning process responsive to local needs; and strengthening horizontal coordination and collaboration.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship or publication of this article.

References

Afrobarometer. (2017) Election of MMDCES and other aspects of local governance: What do Ghanaians say? Evidence from Afrobarometer Round 7 Survey in Ghana. Available at: https://www.afrobarometer.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/gha_r7_presentation_27022018.pdf [Accessed 6 December 2024].

Amanor-Lartey, E.T. (2019) A model of saints, wizards and demons: the dynamics of public policy implementation. Ghana Social Science Journal, 16 (2), 140–153.

Antwi-Boasiako, K.B. (2010) Administrative decentralization: should districts and regions elect their own leaders in Ghana? African Social Science Review, 4 (1), 35–51. https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/government/19

Armah-Attoh, D., Ampratwum, E. and Paller, J. (2014) Political accountability in Ghana: evidence from Afrobarometer Round 5 Survey. Afrobarometer Briefing Paper No. 136. Available at https://www.afrobarometer.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/afrobriefno136.pdf

Ato-Arthur, N.S. (2012) The unfinished business of decentralisation: political accountability of local government in Ghana: A case study of the Komenda-Edina-Eguafo-Abrem (KEEA) Municipality. Doctor of Philosophy thesis, Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhems-Universität. Bonn.

Audit Service. (2021) Management letter on the Audit of District Assembly Common Fund and other statutory funds of the Sagnarigu Municipal Assembly for the period January 2020 to September 2020. Audit Report with reference NR/LA/DC/2/vol. 1/12.

Auditor General. (2021) Report of the Auditor-General on the management and utilisation of the District Assemblies Common Fund (DACF) and other statutory funds for the year ended 31 December 2021. Audit Report with reference number AG.01/109/Vol.2/173.

Ayee, J.R.A. (2000) Saints, wizards, demons and systems: explaining the success or failure of public policies and programmes. Accra: Ghana Universities Press.

Ayee, J.R.A. (2008) The balance sheet of decentralization in Ghana. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-7908-2006-5_11. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/226576803_The_Balance_Sheet_of_Decentralization_in_Ghana

Commonwealth Local Government Forum. (2022) Country profile: Ghana. Available at: https://www.clgf.org.uk/resource-centre/clgf-publications/country-profiles/

Duffy, J. (2015) Game theory and Nash equilibrium A project submitted to the Department of Mathematical Sciences in conformity with the requirements for Math 4301 (Honours Seminar), Lakehead University. Available at: https://www.lakeheadu.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/77/images/Duffy%20Jenny.pdf [Accessed 6 November 2024].

Flores, M.G. (2019) What is Nash equilibrium? Available at: https://math.osu.edu/sites/math.osu.edu/files/What_is_2019_Nash_Equilibrium.pdf [Accessed 6 November 2024].

Ghana Health Service. (2004) Collaboration with District Assemblies for a healthy population: a manual for district workers. Accra: Ghana Health Service.

Gulf of Guinea Northern Regions Social Cohesion Project. (2024) Gulf of Guinea Northern Regions Social Cohesion Project Conference held at the Conference Hall, Institute of Local Government Studies, Tamale Campus, 27 March 2024.

Gyampo, R.E. (2008) Direct election of District Chief Executive Mayors: A tool for effective decentralization and political stability. Ghana Policy Journal, (2), 70–92.

Hershovitz, S. (2011) The role of authority. Philosopher’s Imprint, 11 (17), 1-19. Available at: www.philosophersimprint.org/011007/

Institute of Local Government Studies and Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. (2010) A Guide to District Assemblies in Ghana. Accra: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung.

Institute of Local Government Studies. (ILGS). (2021) A ray of hope! Resilient and focused on the transformation agenda. Annual Report. Accra: Institute of Local Government Studies.

Institute of Local Government Studies (ILGS). (2022) In awe about the new ILGS. Annual Report. Accra: Institute of Local Government Studies.

Laski, H.J. (2000) Authority in the modern state. Kitchener: Batoche Books.

Media Foundation for West Africa. (2019) Barriers to citizens’ engagement & participation in governance in Ghana: the critical role of the media. Media & Governance Series, May 2019.

Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development. (2014) Operational manual on local economic development for District Assemblies in Ghana. Accra: Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development.

Peterson, S.B. (1998) Saints, demons, wizards and systems: why information technology reforms fail or underperform in public bureaucracies in Africa. Public Administration and Development. 18 (1), 37–60. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-162X(199802)18:1<37::AID-PAD990>3.0.CO;2-V

Rana, M. (2019) Game theory and John Nash. DOI:10.13140/RG.2.2.17543.55204

Republic of Ghana. (1992) 1992 Constitution of the Republic of Ghana. Accra: Ghana Publishing Company Limited.

Republic of Ghana. (2010) Local Government (Urban, Zonal and Town Councils and Units Committees) (Establishment) Instrument, 2010 (L.I. 1967). Accra: Ghana Publishing Company.

Republic of Ghana. (2014) Intergovernmental Fiscal Transfer Review (Final Report). Accra: Ministry of Finance and Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development.

Republic of Ghana. (2016a) Local Governance Act, 2016 (Act 936). Accra: Ghana Publishing Company

Republic of Ghana. (2016b) Land Use and Spatial Planning Act, 2016 (Act 925). Accra: Ghana Publishing Company.

Republic of Ghana. (2017) Local Governance (Amendment) Act, 2017 (Act 940). Accra: Ghana Publishing Company.

Sanja, N. (2019) Appointment of Ghana’s local government chief executives: a setback on accountability? Journal of Public Administration, 1 (1), 5–16. https://doi.org/10.22259/2642-8318.0101002

Spours, J. (2020) The dynamics of governance and system change: the case of local collaborative relations to support adults with complex needs. PhD thesis, Nottingham Trent University. Available at: https://irep.ntu.ac.uk/id/eprint/44630/1/N0689667%20Thesis%20Revisions-%20Final.pdf [Accessed 6 December 2024].

UNDESA, UNDP and UNESCO. (2012) Governance and development (Thematic Think Piece). Available at: https://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/pdf/Think%20Pieces/7_governance.pdf [Accessed 6 December 2024].

Williams, J.G. (1968) The concept of authority. Journal of Educational Administration, 6 (2), 152–161. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb009625

1 This may be understandable given the background to the 1992 Constitution: it came from a military government metamorphosing into civilian government after over ten years of rule. The tendency to recentralise power was high. As has been noted by Ato-Arthur (2012, p. 226) “Ghana’s decentralisation history since the colonial days is a story of repeated and usually successful efforts to (re)centralise power instead of decentralising power and resources to the sub-national level”.