Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance

Issue 30

December 2025

POLICY AND PRACTICE

Evaluating the Service Quality of Bangladesh’s Open Market Sale Food Security Programme

Nure Alam

Public Administration and Governance Studies, Jatiya Kabi Kazi Nazrul Islam University, Trishal, Mymensingh, 2220, Bangladesh, mdnurealam93@gmail.com

Maruf Hasan Rumi

Department of Public Administration, University of Dhaka, Dhaka-1000, Bangladesh, marufhasanrumi@du.ac.bd & Department of Political Science, Texas Tech University, Lubbock-79409, Texas, United States

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/8xts4p20

Article History: Received 27/05/2025; Accepted 04/11/2025; Published 31/12/2025

Citation: Alam, N., Rumi, M. H. 2025. Evaluating the Service Quality of Bangladesh’s Open Market Sale Food Security Programme. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, 30, 92–110. https://doi.org/10.5130/8xts4p20

© 2025 by the author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercial, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Abstract

Bangladesh has implemented numerous safety net programmes since 1971 in an effort to fight against persistent and long-term poverty. Although most of these programmes are geared towards rural areas, urbanisation has led to an increase in the number of urban poor during the past 40 years. Open Market Sale (OMS) is the oldest, biggest and priciest metropolitan social protection programme, aiming to provide low-cost rice and flour to the urban poor. This study seeks to evaluate OMS’ service quality, using a qualitative, exploratory research design. It finds that the OMS programme is beset by numerous issues including poor targeting, political interference, leakages, loss of food grains, and low-quality goods – all of which impede its service quality. Moreover, it is significantly underfunded, local authorities are not always supportive, and corruption is very common among both programme administrators and local dealers. The study suggests that the government should regulate the operation of the OMS programme more efficiently, as its effectiveness largely relies on its service quality.

Keywords

Open Market Sale; Social Safety Net; Service Quality; Food Programme; Food Security; Urban Poverty; Bangladesh

Introduction

Every individual is entitled to sufficient nourishment and freedom from hunger. The right to food has been recognised by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights since 1948 as a part of the right to an adequate standard of living (Mechlem 2004). At the national levels, the governments must ensure food security, since its absence can cause economic, social and political issues that lower productivity and growth. In extreme cases, food shortages can cause political and societal turmoil as well (Koren et al. 2021). Since independence, Bangladesh has made great progress in food production and poverty alleviation, despite facing several obstacles to economic development (Mohajan 2018). However, food insecurity persists as the cost of food has increased beyond the financial means of the impoverished population. This problem is exacerbated by various obstacles faced by the country, such as rapid population expansion, political instability and natural disasters (Ahmed et al. 2025). In addition, the production of rice and other crops is regularly affected by natural disasters, while global price hikes disproportionately cause food insecurity for vulnerable people. For example, as of November 2025, Bangladesh is facing significant food insecurity challenges due to persistently high inflation, with the official food inflation rate standing at 7.36% (Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics 2025).

The World Food Summit held in 1996 defined four dimensions of food security: physical availability of food; economic and physical access to food; food utilisation; and stability of the other dimensions over time (Aziz et al. 2023). In developing countries like Bangladesh, safety net programmes are essential in order to ensure access for people impacted by poverty (Begum et al. 2014; Shahabuddin et al. 2018). Since independence in 1971, the government of Bangladesh has provided a wide range of relief to people impacted by natural calamities and economic difficulties. As a part of this safety net, Open Market Sale (OMS) was inaugurated in the 1980s as a tool to stabilise the price of food for vulnerable people. Later, the OMS programme pivoted to providing subsidised rice and flour in towns and cities, where poverty and rapid urbanisation have expanded the need for food assistance (Dorosh and Shahabuddin 2002). More recently, Bangladesh’s National Food and Nutrition Security Policy was approved in August 2020 to ensure that the country achieves food and nutrition security as it works towards the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 2.1

However, the efficiency of the OMS programme is a subject of concern, particularly in terms of its delivery and the quality of food grains. Challenges identified include limited resources, inadequate monitoring and weak grievance redress mechanisms (Wu et al. 2023); administrative complexity, high costs, leakages, mistargeting, weak governance, lack of transparency, political capture, and corruption in programme implementation (Masud-All-Kamal and Saha 2014; Sifat 2021); weaknesses in policies, a lack of integration and coordination, political instability, corruption, and budget shortages (Sarker and Nawaz 2021).

Although existing studies on the OMS programme and comparable social safety net interventions in Bangladesh have documented implementation challenges such as weak monitoring, governance deficiencies, and incentive misalignment among service providers etc much of this literature tends to evaluate how the programme is designed and managed rather than how it is experienced by beneficiaries (Kaiser et al. 2023). Beneficiary perspectives are often treated descriptively or as secondary outcomes, with limited systematic assessment of how service quality is experienced at the point of delivery. Moreover, prior research tends to focus either on material aspects of programme delivery or on institutional efficiency in isolation, offering insufficient integration of tangible service attributes (eg food quality, accessibility) with systemic performance dimensions (eg delivery timeliness, resource allocation). This study therefore aims to evaluate the current service quality of the OMS programme in Bangladesh by analysing beneficiary satisfaction with both tangible aspects and systemic efficiency. It is hoped that the findings will benefit policymaking and programme reform and thereby improve OMS service delivery for those facing food insecurity and poverty.

Literature review

Social Safety Net Programmes (SSNPs) are widely accepted as a method of offering protection to the economically vulnerable population. Their history dates back to Ancient Egypt and the Roman Empire (World Bank 2014). These programmes were very much in the spotlight after the financial crisis caused by the breakup of the Soviet Union and East Asian countries in the 1990s. Eastern and Central Europe also experienced economic and political instability after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Later, the World Bank came forward to assist Eastern European countries in establishing safety net programmes (Rahman 2012). SSNPs are mainly categorised into two groups: social protection and social empowerment. Social protection is divided into categories such as social insurance, social assistance, and labour market/pension policies and programmes. However, nations across the globe implement various public measures to address the issue of hunger (Begum et al. 2014). Here are just a few examples:

• In the United States, around 41 million people, constituting approximately one-twelfth of the total population, derive advantages from the national food voucher initiative known as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) (CBPP 2025).

• In the Middle East there is substantial expertise devoted to implementing safety net initiatives, specifically consumer price subsidy programmes, with a special emphasis on targeting food-related needs (Alderman 2002).

• In response to the 2008 crisis, Italy launched the Carta Acquisti, a targeted support scheme enabling low-income households to buy essential food and utilities, thereby mitigating the impact of rising economic hardship (Madama et al. 2014).

• In India, receiving free food in the community is a typical way to obtain a social security number.

Yet, although SSNPs have expanded worldwide, their outcomes have often fallen short of expectations. As Ahmed et al. (2014) note, many countries struggle with ineffective targeting, administrative inefficiencies, insufficient funding, and leakages or corruption, all of which prevent benefits from reaching the most vulnerable populations.

Studies reveal that OMS is a crucial food distribution mechanism, which has similarities with safety net programmes such as India’s Public Distribution System (PDS) and the US SNAP in terms of combating food insecurity and supporting vulnerable populations during economic distress. However, they face challenges posed by targeting errors, leakage and beneficiary satisfaction (Baijal et al. 2017; McDaniel et al. 2023; Hossain and Simi 2024). For example, India’s PDS often faces targeting errors due to flawed beneficiary identification and lack of reliable poverty mapping. Nearly 40% of food grains fail to reach intended beneficiaries due to inclusion and exclusion errors (Jha et al. 2013). The OMS programme in Bangladesh is similarly criticised for inefficiency in reaching the truly needy people, often due to political manipulation and faulty targeting mechanisms. The lack of comprehensive data on the urban poor and inadequate poverty assessments further hinder the accurate allocation of benefits (Sarker and Nawaz 2021). The US SNAP programme also faces issues with targeting, particularly among households who do not accurately report their income or fall through the cracks in eligibility verification (Gundersen 2019). As a result, the US Department of Agriculture (2021) revealed that 3.5 million individuals ineligible for SNAP still received benefits, while 1.5 million eligible beneficiaries were excluded due to administrative errors. Leakage, the loss of programme benefits due to inefficiencies in the distribution chain, is another common issue. In India, the PDS is criticised for poor service delivery, including inconsistent food availability, long wait times, and poor grain quality (Ray and Subramanian 2022). Comparatively, SNAP, an electronic and cash-based programme, has higher beneficiary satisfaction due to its flexibility and accessibility (Brown and Best 2017).

The Government of Bangladesh operates the OMS programme to stabilise food prices and support low-income households by distributing subsidised rice and wheat flour nationwide. Under the current scheme, eligible individuals may purchase up to five kilograms of rice per person at a subsidised rate – often around Tk 30 per kg depending on market conditions (Dhaka Tribune 2025). OMS also supplies wheat flour (atta) at a subsidised price, typically around Tk 24 per kg, with the government allocating one tonne of flour per upazila (local authority) per working day to ensure adequate local availability (The Business Standard 2025). OMS centres operate across hundreds of upazilas and urban locations, including district and city corporation areas, with daily allocations of one tonne of rice at each designated outlet (Dhaka Tribune 2025). The programme is administered by the Directorate General of Food, which oversees market monitoring, determines pricing standards, and regulates supply to ensure food grains reach vulnerable groups such as low-income earners and those experiencing temporary economic hardship.

However, the SSNPs are not without controversy (Ahmed et al. 2014). Though these programmes primarily try to address the demands and needs of economically vulnerable people, they have not always been able to effectively target the real beneficiaries, due to selection errors. Moreover, the cost of the products associated with transactions, political involvement leading to extortion, excessive administrative rules, and corruption, have resulted in beneficiaries getting inadequate services (Conning and Kevane 2002; Bloom et al. 2011). In addition, these programmes are beset with numerous implementation challenges, such as low coverage due to lack of adequate resources, poor design, political obstacles and poverty (Barrientos and Hulme 2008).

Despite all these, however, SSNPs in Bangladesh have shown positive impacts. For instance, they mitigate seasonal and non-seasonal food deprivation in the Northwest region of Bangladesh, although they are not a reliable tool for Monga2 eradication (Khandker 2012). Nevertheless, there is evidence that SSNP transfers do not reach the poor and vulnerable in their full amounts, with only about 60% of the programme budgets spent on purchasing food. This highlights the need for revising and monitoring the beneficiary selection process. In addition, beneficiary perspectives are vital in assessing the effectiveness of these programmes. Many beneficiaries in Bangladesh have expressed dissatisfaction with monitoring and existing rates in SSNPs, suggesting the need for improved governance practices (Kaiser et al. 2023). While there is extensive literature on SSNP challenges and best practices in Bangladesh, there is a notable lack of specific, in-depth research focusing on OMS’s service delivery programme, particularly in the context of urban Bangladesh. Existing studies often discuss SSNPs in a broader context only, and the literature reviewed contains minimal discussion on the evaluation of the OMS distribution system by the Ministry of Food. This study addresses this knowledge gap by exploring how the OMS programme, as a significant urban social safety net initiative, navigates these challenges and what specific strategies can be employed to enhance its effectiveness, transparency and responsiveness to the urban poor.

Theoretical framework

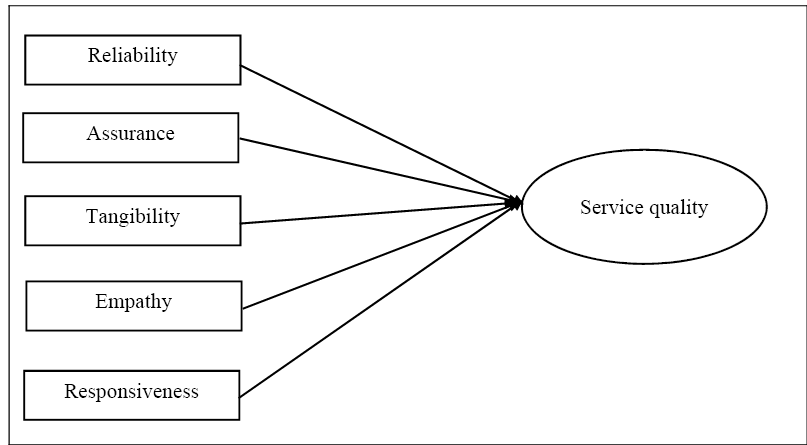

The SERVQUAL model offers a robust framework for assessing the performance of the OMS programme because it captures the multidimensional aspects of service delivery that shape beneficiaries’ experiences. Developed by Parasuraman et al. (1985), SERVQUAL evaluates service quality by measuring the gap between users’ expectations and their actual perceptions across five key dimensions: reliability, assurance, tangibility, empathy and responsiveness. These dimensions are particularly relevant for a public distribution scheme such as OMS, where consistent supply, staff conduct, clarity of information and responsiveness to beneficiary needs directly affect programme effectiveness.

As a social safety net intervention designed to support economically vulnerable populations, the OMS programme must be evaluated not only on its operational coverage but also on the quality and consistency of its service delivery. The SERVQUAL approach has proven useful in various public sector contexts, enabling authorities to identify service gaps and improve policy implementation (Ray 2020; Shi and Shang 2020). In Bangladesh, recent applications of SERVQUAL such as Rumi et al. (2021) in healthcare settings and Hoque et al. (2023) in higher education demonstrate its capacity to assess service performance in complex public service environments. Applying the model to OMS thus provides an evidence-based method to evaluate beneficiary experiences and highlight areas requiring administrative and operational reforms. In operationalising the model for this study, the dimensions are defined as follows:

• Reliability: the service provider’s capacity to deliver services accurately and dependably.

• Assurance: the competence and professionalism of service providers, and their ability to generate trust and confidence among beneficiaries.

• Tangibility: the physical condition and appearance of the service environment, including infrastructure, equipment and the distributed goods themselves.

• Empathy: the degree of personalised attention and concern shown to beneficiaries.

• Responsiveness: the promptness and willingness of service providers to assist beneficiaries and address their needs.

Figure 1. The SERVQUAL model source: adapted from Parasuraman et al. (1985)

Under these dimensions, SERVQUAL provides a relevant and evidence-based method for evaluating whether the OMS programme is meeting its objectives and where service improvements are most needed.

Methodology

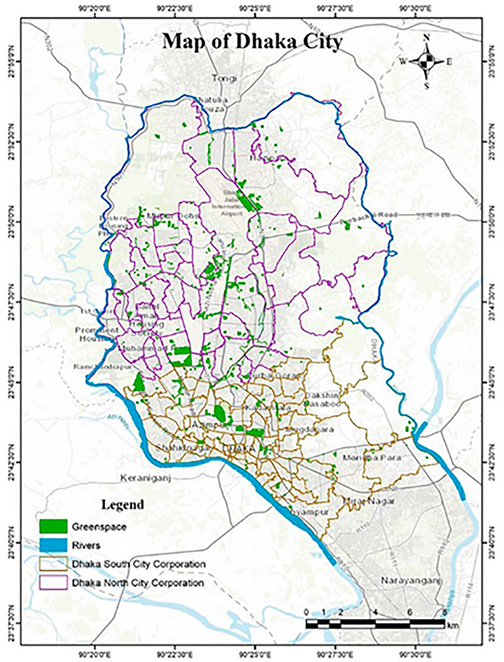

This study adopted an exploratory research design and qualitative approach to investigate the service quality of the OMS programme and gain insights into citizens’ perceptions of its operation. Dhaka, located in the central region of Bangladesh, is the capital of the country and has the largest urban population living below the poverty line – a group considered to be the main beneficiaries of the OMS programme. Therefore, the researchers selected Dhaka as the study area. Data was collected between February 2022 and May 2022.

Source: Survey of Bangladesh 2021

Primary data was collected using a purposive sampling technique which ensured representation from diverse stakeholders including beneficiaries, programme administrators, local vendors and community leaders. It also allowed the authors to identify participants who had experienced the service of the OMS programme. Initially, 30 in-depth interviews (IDIs) with beneficiaries were planned, but after completing 20 IDIs showing similar findings, the researchers decided the final 10 interviews were not needed. The IDIs used a semi-structured questionnaire and open-ended questions, which elicited detailed responses from beneficiaries regarding programme effectiveness, accessibility, affordability and customer satisfaction. In a second phase, key informant interviews (KIIs) were carried out with five government officials from the Ministry of Food and 10 other stakeholders (journalists, academicians, local leaders, NGO activists). The average interview length was 30–40 mins. Two respondents did not complete their interview due to time constraints, representing circa 5% of the total respondents. Finally, in the third phase, four additional participants were interviewed to check the validity of the information and explore emerging themes.

This approach aimed to enhance accessibility for participants and foster open and constructive conversations pertaining to service delivery of the programme. Data collectors discouraged non-participants’ presence during the interviews. Audio recording and field notes were utilised, with the consent of the participants, to capture the actual interviews. Field notes were then provided to the participants to check the accuracy of the information and allow them to offer additional information.

One caveat is that, although this study employs purposive sampling to select participants with relevant experiences and perspectives on the OMS programme, this method may unintentionally exclude certain groups, particularly those who are marginalised or hard to reach. To mitigate such potential biases, the study employed multiple data sources, supplementary interviews, and transparency in data interpretation.

Secondary data was gathered from several sources, including government offices, selling locations and community centres. Additionally, the study analysed content related to SSNPs and the OMS programme found in government reports, published journal articles, NGO reports and credible website sources.

Thematic analysis was carried out on the qualitative data gathered. The interview transcripts were systematically examined for recurrent themes, patterns and categories as a part of this procedure. Text fragments were coded, and these codes were arranged into broader themes to establish the findings of the study. Ethical considerations were fully maintained throughout the entire data collection process, and every effort was made to ensure the anonymity of the respondents. The research was granted ethical clearance by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Exeter [ERC/07/2022]. This study is part of a graduate thesis by one of the authors submitted to the University of Exeter.

Findings and discussion

Bangladesh’s OMS programme is a government-funded initiative that aims to provide essential goods to underprivileged people in the country. It aims to provide affordable access to essential food items, such as rice and flour, for low-income families living in urban areas. However, the quantity available per beneficiary is often limited: eg a maximum of 5 kilograms per household per month. Under the food distribution system, the Directorate of Food, part of the Ministry of Food, procured food through a tendering process, and the OMS programme was used to distribute it. The most competitive bidders supply rice and flour at pre-determined rates, and the subsidised food is distributed to local dealers, who sell it at designated points in urban areas.

The programme is organised in several phases:

1. The government agrees to support the urban poor population by running the programme.

2. The assessment team at the Ministry of Food selects the highest-priced products (those to be subsidised), and the Food Directorate estimates the budget and invites bidders.

3. The Directorate proposes a stakeholder to co-run the programme, and contracts with suppliers from rural areas via its Upazila Food Office.

4. The Upazila Food Office collects and tests the crops, after which the Food Directorate transfers them to the Ministry of Food for storage.

5. The programme itself then commences, with the selection of official dealers, who must register and pay for a Tk300 non-judicial stamp.

6. Local dealers receive the food, and then sell it in shops, trucks and temporary stores.

The performance of the OMS programme can be measured by analysing the specific populations who benefit, the size and scope of coverage (ie the total number of households or persons), and the extent of benefits recipients receive. In this regard, prior studies explored that the programme faced a range of criticisms from academics and policy practitioners including poor targeting, due to institutional limitations and the existing sociopolitical situation (Sarker and Nawaz 2021); and significant ‘leakage’ of food grains, for reasons including poor affordability, low quality, and bad practices in the supply chain (Ray and Subramanian 2022). The present study also finds that service quality in the OMS programme is below standard. Its findings are grouped here under several headings.

Practical problems for beneficiaries

Recipients are dissatisfied with the process of buying products from the trucks provided by the dealers, in several ways. The severe problems highlighted by the beneficiaries are discussed below.

Excessively long queues: There is typically a huge queue in front of each truck, as so many people in each area are in poverty, so need to buy products from the OMS truck to save money. Sometimes the queue is so long that people who arrive late are unable to buy at all. This is a long-standing problem identified by several earlier studies (Ahmed et al. 2004; Alderman and Hoddinott 2007; Nahid 2017). A beneficiary stated that:

The OMS trucks are evenly dispersed in the underdeveloped section of the urban area... however, there is no guarantee of obtaining products from there if you arrive late in the queue in the early hours of the morning (IDI participant 8, Personal Communication 22 March 2022).

Insufficient supply: The quantity of goods sold by the OMS trucks is insufficient to meet the needs of the beneficiaries, and the allocation of food is extremely small, particularly for large families. They continue to be reliant on regular store purchases as well, which creates further financial strain for them. Some beneficiaries reported having to cut the number of food products they bought, or purchase them on loan. It was clear from the IDIs that the limited quantity and selection of products available through the OMS can give consumers temporary support but does not offer them any long-term remedy. This finding is supported by Alam and Hossain (2016): the amount of food received by beneficiaries is insufficient to meet their basic needs. A beneficiary stated that:

We are a big family, and the amount of goods we get from the OMS truck isn’t enough for us. There is huge corruption in the overall OMS distribution channel... Local politicians have a lot of power over what we get and how it gets delivered (IDI participant 5, Personal Communication, 10 March 2022).

Impersonal service: This study also found a lack of individual emphasis and care for beneficiaries of the OMS programme. The authorities running the programme do not exercise sufficient care, and this is the case throughout the entire process: from the warehousing of the food all the way through to its delivery in the OMS trucks. The programme is not delivered in a timely manner, nor do authorities respond to complaints or issues raised. This echoes earlier findings by Uddin (2013) and Nahid (2017). However, when asked about this point a government official countered that:

We are diligently striving to mitigate inflation and cater to the underprivileged segment of the urban population. With numerous constraints in the field, we consistently monitor the market and intervene as needed to dismantle the corrupt syndicates operating in the local market (KII participant 2, Personal Communication, 8 February 2022).

Institutional factors

The existing administrative structure and poor management cause targeting errors in the OMS programme. For example, the Food Planning and Monitoring Unit is the specialised research unit of the Directorate of Food, but it has not undertaken any effective attempts to ensure the OMS programme becomes more citizen centric. Moreover, the unit has no information regarding the number of people eligible for OMS services, or records of the operational difficulties and limitations of the OMS programme. Typically, the government distributes annual funds based on assumptions and the country’s economic condition. In years with a larger budget, the OMS programme expands food grain sales to more people through more stores; in years with a relatively small budget, food grain sales are reduced, and go to fewer individuals. As a result, many eligible recipients are excluded from this programme’s benefits due to institutional weaknesses.

Issues of political loyalty

The OMS is tasked with the coordination of local government and field administration; but decisions are made by a committee designated by the implementing ministry or agency. Dealer appointments and shop locations are the two most crucial aspects at field level. Most committee members are government officials: legally neutral, but in practice affiliated to the ruling political party and likely to favour local political leaders in all decisions. They may even provide illegal privileges to the leaders and activists of the ruling party, in violation of the law. For instance, according to the guidelines, people with prior business expertise or those with designated shops should be appointed dealers. The committee, however, typically appoints instead local incumbent political leaders or people recommended by them as dealers. This study’s findings support those of Morshed (2009), namely that local political dynamics play a crucial role in implementing the OMS.

Many dealers violate the law, for example, charging higher prices, by not maintaining store hours, and selling subsidised products on the black market. But the committee does not pursue administrative action against them; instead, the problem is resolved through the intervention of local political leaders. For example, Chowdhury et al. (2020) found that the committee chooses the location of OMS shops based on members’ personal experience and local information rather than any scientific data, survey or census report. Similarly, Razzaque et al. (2020) found that OMS shops are positioned in areas loyal to the ruling political party in local and national elections or considered likely to vote for them in the future. Consequently, the OMS programme does not accomplish its intended objective. Most of the poor do benefit from it, even though it is intended for them. A beneficiary stated that:

Local people get easily frightened of complaining against the local distributor as most of them are politically powerful and can do harm to us. There is projected a [telephone] number in the food truck to call for remedy but mostly the number is found off or out of reach (IDI Participant 4, Personal Communication, 9 May 2022).

Quality of food grains

The findings of this study indicate that the majority of beneficiaries are dissatisfied with the quality of OMS food grains, even though they purchase them because their prices are significantly lower than those of other food grains. Respondents reported that the food they are offered is not carefully checked, and has been stored for several months, causing its quality to suffer. As a pre-disaster measure, the government hoards food grains. It then sells previously accumulated grains when the new harvesting season begins. Unfortunately, most government warehouses have severe structural flaws. If food grains are stored for an extended period in these deficient warehouses, their quality is typically degraded or diminished (Ahmed et al. 2009). In this regard, a beneficiary stated that:

The government distributors provide low-quality products and delay in loading the trucks for which they didn’t get any illegal money. Sometimes they also cheat in weighing the food grains and we had to bear the loss of that evil deed (IDI Participant 10, Personal Communication, 14 April 2022).

Loss of food grains

According to government procedures, all OMS food grains are tested at the Institute of Food Science and Technology (IFST) of the Bangladesh Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (BCSIR). Two sorts of testing are conducted: physical tests and laboratory tests. During the physical examination, the grain is analysed for its levels of foreign matter (such as dust and stem particles), fragmented grain, grain size, grain degradation, grain colour and grain odour. The laboratory tests show the levels of protein, carbohydrates, fat, humidity and fibre in the food grain samples. They sell some of the subsidised food grains through the OMS shops at prices fixed by the government, but others on the black market at high prices to recover their losses. Typically, dealers do not give full weight at the time of selling. They use manual scales or faulty weighing machines. Another problem, observed by Ahmed et al. (2009), is that transport/shipping agencies tend to claim high grain losses from transit, even when the actual loss is less. Additionally, Tabassum (2016) showed that most dealers claim they never receive the total amount of food grains allocated to them from the central storage depot or local supply depot. Some consumers reported getting 3 kg instead of the 5 kg they were entitled to receive under the OMS programme (Tabassum 2016). The end result of all these losses is that the beneficiaries do not get their correct amount of food. There is also a related financial loss, as revealed by Chowdhury et al. (2020): for every Tk1 spent on the OMS programme by the government, only an average of Tk0.88 reaches the intended beneficiaries (Chowdhury et al. 2020). When asked about this point, a government official stated that:

We immediately take actions from the central offices whenever we get news of irregularities at local distribution or in the local food storage. A computerised system is developed here so that we can easily track, monitor and resolve the grievances as soon as possible (KII Participant 5, Personal Communication, 3 May 2022).

In this context another government official highlighted that:

Due to limited awareness and inadequate access to the internet, underprivileged individuals seldom utilise these mechanisms to lodge complaints. In many cases, they are not even aware that such grievance-reporting mechanisms exist (KII Participant 7, Personal Communication, 15 April 2022).

Targeting errors

The practice of selecting households or people who satisfy the requirements to obtain programme benefits is known as household or individual targeting. This can be accomplished through means testing or by utilising a set of indicators, including geographic targeting (Sumarto and Suryahadi 2001). However, according to several studies in recent decades, targeting errors (both exclusion and inclusion errors) are common in the OMS programme, due to corruption and nepotism (Islam 2015). They can result in food subsidies going to better-off sectors of society rather than people who are starving. This makes the OMS programme inefficient and of limited effectiveness (Razzaque and Rahman 2019).

In this regard, a government official said:

The control of corruption is not a single-handed job of the government; rather it’s a team effort for all the important stakeholders in the market. Awareness of the consumers and strict monitoring by the government will be the key to ensure equitable distribution of OMS products to the citizens who actually need this social protection (KII Participant 8, Personal Communication, 25 April 2022).

However, targeting errors in the OMS programme pose a persistent challenge, hindering its ability to reach its intended beneficiaries. The OMS programme often excludes a significant portion of the urban poor, especially those in marginalised areas or outside the formal system, due to inaccurate data and inefficient poverty mapping. Political elites also often prioritise supporters of ruling parties or local leaders over those in genuine need. Historically, Bangladesh has experienced persistent patterns of biased selection in government-supported projects. Even for this programme, there are claims that beneficiaries are frequently selected by local officials and politicians based on personal connections, leaving many deserving individuals excluded.

A beneficiary reported that:

Political leaders heavily influence the targeting process for food distribution, highlighting the skewedness of resource distribution (IDI Participant 10, Personal Communication, 14 April 2022).

A local community leader said:

I was unaware of eligibility criteria and political affiliation played a significant role in determining who received benefits (KII Participant 7, Personal Communication, 15 April 2022).

Corruption

Corruption is a significant issue in the OMS programme, hindering its ability to serve vulnerable populations and causing inefficient resource use, thereby exacerbating food insecurity in urban areas. Local politicians and government officials often divert food to political allies or sell it at higher prices on the black market. Dealers and local distributors frequently engage in illegal activities like bribery and selling food outside OMS outlets, due to weak monitoring and enforcement systems, resulting in ‘leakage’ and depriving the intended beneficiaries of essential resources. The lack of robust oversight mechanisms allows these corrupt practices, including misreporting food quantities and weights, to continue.

A government official acknowledged that:

Corruption at the local level, often involving political leaders, hinders effective distribution of the OMS programme (KII Participant 5, Personal Communication, 3 May 2022).

A beneficiary reported:

Receiving less than promised, highlighting the scale of political capture within the system and eroding trust in its implementation (IDI participant 5, Personal Communication, 10 March 2022).

Resource constraints

Even though OMS is the most expensive and extensive social protection programme in urban areas, most of the poor people for whom it was initially intended are excluded due to the lack of supply compared to the enormous demand. Mahmuda (2015) found that almost 50% of beneficiaries claimed that those who received food grains did not meet the programme’s criteria, and almost 20% stated that they had received a lower amount than was promised. They are also typically required to wait in a long queue to purchase the food grains – but poor people are busy, with several jobs, and cannot spend a long time in OMS shops. Mahmuda also concluded that the government does not provide enough food grains or enough OMS shops to meet recipients’ preferences and needs.

The OMS programme’s financial and logistical constraints limit its ability to provide adequate coverage to all intended beneficiaries, especially in urban areas where food insecurity is most pronounced. It struggles to meet the needs of the urban poor, with only a small fraction of beneficiaries being covered, insufficient food quantities, long queues at distribution points, and access difficulty for many beneficiaries, particularly in densely populated areas. Poor food storage and transportation infrastructure, coupled with poorly maintained warehouses and inadequate transportation systems, also contribute to ineffectiveness through the long-term loss of food grains and reduced quality.

A beneficiary highlighted that:

The food we get from the OMS trucks is always limited, and there are so many people trying to buy that not everyone gets a share (IDI Participant 4, Personal Communication, 9 May 2022).

A local government official explained:

We are doing our best with limited resources, but the demand far exceeds what we can provide (KII participant 2, Personal Communication, 8 February 2022).

Overall, OMS contributes towards achieving SDG 2 (zero hunger) and SDG 11 (sustainable cities and communities). The OMS programme aims to reduce food insecurity in urban areas by addressing low income and high food prices, contributing to Target 2.1 of SDG 2 (Aziz and Moniruzzaman 2023). It focuses on improving nutritional outcomes, primarily via distribution of rice and flour, to help vulnerable households meet their basic needs and eradicate malnutrition (Target 2.2). However, this study suggests strongly that the inherent deficiencies of the current system pose a clear obstacle to OMS’s ambitions, as does severe underfunding. In principle, OMS should be an effective tool for tackling the problem of food insecurity, and there is a strong case for raising the per-head food allocation (Rahman 2012) – but an improved monitoring system, new strategy and enhanced budget are required. It is also essential to reduce the amount of system leakage and improve targeting (Masud-All-Kamal and Saha 2014).

Conclusion and policy recommendations

Bangladesh has experienced significant economic growth and advances in food production, but poverty and malnutrition persist. Over 10 million people struggle to purchase enough food due to acute urban poverty. The country’s social safety net programmes, which originated in food rations and relief operations, have evolved into a national development priority. Notably, the OMS initiative has been praised for improving food security for the urban poor despite challenges in implementation – but it has operated for nearly 40 years without significant revisions or new thinking. Its service delivery is beset by numerous issues and challenges that require to be fixed.

This study recommends rethinking and redesign of the OMS structure. The following recommendations are based on the discussion above, and the authors’ evaluation of the current OMS service quality:

• Since the main objective of this programme is to offer food security to vulnerable people living in urban areas, the process of choosing beneficiaries should be carried out in a fair and transparent manner. In Bangladesh, proposed strategies for improvement include digital systems for beneficiary verification, real-time distribution monitoring, and accurate poverty mapping to reduce targeting errors and leakage.

• Expanding the programme’s scope to cover the urban poor and addressing seasonal food insecurity would be beneficial.

• Partnering with local research institutions for third-party monitoring and incorporating innovative governance mechanisms such as mobile feedback systems could improve beneficiary satisfaction.

• Therefore, the OMS programme should select beneficiaries based on a poverty map that displays the incidence of poverty by geography.

• Given the significant disparity between the current coverage and the size of the vulnerable population in metropolitan regions, it is imperative to broaden the programme’s scope.

• Excessive leakage affects the OMS programme, so the government should implement measures to reduce loss. As the transportation cost varied highly on the purchase rate, the transaction system can be transferred to the private sector to prevent transit losses.

• Bangladesh should adopt India’s third-party monitoring model for use in the OMS programme to enhance government accountability and improve service delivery in areas beset by local corruption and political influence.

• Independent auditors or NGOs should conduct regular audits and beneficiary surveys, and make public reports on monitoring activities, financial allocations and food distribution outcomes.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Md Limon Bhuiyan and Md Akram Hossain for helping in the proofreading and referencing process as this manuscript was developed.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship or publication of this article.

References

Ahmed, A.U., Rashid, S., Sharma, M.P. and Zohir, S. (2004) Food aid distribution in Bangladesh: leakage and operational performance. Available at: https://hdl.handle.net/10568/158040

Ahmed, A.U., Quisumbing, A.R., Nasreen, M., Hoddinott, J. and Bryan, E. (2009) Comparing food and cash transfers to the ultra-poor in Bangladesh. FCND Discussion Paper No. 192. International Food Policy Research Institute. https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/92803/files/comparing%20food%20and%20cash%20transfers%20to%20the%20ultra%20poor%20in%20bangladesh.pdf

Ahmed, I., Jahan, N. and Zohora, F.T. (2014) Social safety net programme as a mean to alleviate poverty in Bangladesh. Developing Country Studies, 4 (17), 46–54.

Ahmed, Z., Kadir, A., Alam, R. and Laskor, M.A.H. (2025) The impact of staple crop price instability and fragmented policy on food security and sustainable development: a case study from Bangladesh. Discover Sustainability, 6 (1), 79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-025-00878-7

Alam, M.A. and Hossain, S.A. (2016) Effectiveness of social safety net programs for poor people in the government level of Bangladesh. International Journal of Social Sciences and Management, 3 (3), 153–158. https://doi.org/10.3126/ijssm.v3i3.14953

Alderman, H. (2002) Subsidies as a social safety net: effectiveness and challenges. Social Protection Discussion Paper 224. Washington, DC: The World Bank. Available at: https://ideas.repec.org/p/wbk/hdnspu/25299.html

Alderman, H. and Hoddinott, J. (2007) Growth-promoting social safety nets. 2020 Vision Brief No. BB16, Special Edition. International Food Policy Research Institute. https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:fpr:2020br:bb16

Aziz, A.H. and Moniruzzaman, M. (2023) Challenges in achieving SDG 2-zero hunger in Bangladesh: an analytical study on food certainty in Bangladesh from Zakat Perspective. International Journal of Zakat, 8 (1), 43–63. https://doi.org/10.37706/ijaz.v8ii.398

Baijal, S., Kumar, D. and Kumar, A. (2017) A study on the efficacy of the public distribution system in India. The Creative Launcher, 2 (1), 58–67. https://doi.org/10.53032/tcl.2017.2.1.10

Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. (2025) General point to point inflation reaches to 8.29pc in November. Available at: http://nsds.bbs.gov.bd/en#:~:text=2024%2D2025p,)%20%7C%20Gross%20domestic%20product%20%2D%20GDP

Barrientos, A. and Hulme, D. (eds.) (2008) Social protection for the poor and poorest: concepts, policies and politics. London: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-0-230-58309-2

Begum, I.A., Akter, S., Alam, M.J. and Rahmatullah, N.M. (2014) Social safety nets and productive outcomes: evidence and implications for Bangladesh. Mymensingh, Bangladesh: Bangladesh Agricultural University. https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.1392.7041

Bloom, D.E., Jimenez, E. and Rosenberg, L. (2011) Social protection of older people. PGDA Working Paper No. 83. Programme on the Global Demography of Aging, Harvard Initiative for Global Health. https://content.sph.harvard.edu/wwwhsph/sites/1288/2013/10/PGDA_WP_83.pdf

Brown, H.E. and Best, R.K. (2017) Logics of redistribution: determinants of generosity in three US social welfare programs. Sociological Perspectives, 60 (4), 786–809. https://doi.org/10.1177/0731121416656843

Centre on Budget and Policy Priorities. (CBPP) (2025) The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). Available at: https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/the-supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program-snap [Accessed 25 November 2025].

Chowdhury, S.K., Hoque, M.M., Rashid, S. and Bin Khaled, M.N. (2020) Targeting errors and leakage in a large-scale in-kind transfer program: the food friendly program in Bangladesh as an example. IFPRI Discussion Paper. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). https://doi.org/10.2499/p15738coll2.133761

Conning, J. and Kevane, M. (2002) Community-based targeting mechanisms for social safety nets: a critical review. World development, 30 (3), 375–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(01)00119-X

Dhaka Tribune. (2025) OMS rice to be sold from February, 28 January 2025. Available at: https://www.dhakatribune.com/bangladesh/government-affairs/372130/rice-to-be-sold-in-open-market-from-february

Dorosh, P.A. and Shahabuddin, Q. (2002) Rice markets in Bangladesh: a study of price stabilization and efficiency. MTID Discussion Paper No. 46. International Food Policy Research Institute. https://cgspace.cgiar.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/fa71d151-911d-477c-b810-7b3fc85b306c/content

Gundersen, C. (2019) The right to food in the United States: the role of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 101, 1328–1336. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aaz040

Hoque, U.S., Akhter, N., Absar, N., Khandaker, M.U. and Al-Mamun, A. (2023) Assessing service quality using SERVQUAL model: an empirical study on some private universities in Bangladesh. Trends in Higher Education, 2 (1), 255–269. https://doi.org/10.3390/higheredu2010013

Hossain, M.J. and Simi, R.A.F. (2024) Transformation for sustainable and nutrition sensitive food systems in Bangladesh: current status and future strategies. In: Acharya, G.D. and Rashid, Md. H. (eds.) Accelerating the process of transformation for sustainable and nutrition sensitive agri-food systems in South Asia. Dhaka, Bangladesh: SAARC Agriculture Centre, pp. 12–38. https://www.sac.org.bd/transformation-for-sustainable-and-nutrition-sensitive-agri-food-systems-in-south-asia/

Islam, M.M. (2015) The politics of the public food distribution system in Bangladesh: regime survival or promoting food security? Journal of Asian and African Studies, 50 (6), 702–715. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021909614541082

Jha, R., Gaiha, R., Pandey, M.K. and Kaicker, N. (2013) Food subsidy, income transfer and the poor: a comparative analysis of the public distribution system in India’s states. Journal of Policy Modeling, 35 (6), 887–908. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpolmod.2013.01.002

Kaiser, Z.A., Uddin, N. and Yaqub, M. (2023) Governance of the social safety net in Bangladesh: a study on the employment generation programme for the poorest. Indian Journal of Public Administration, 69 (2), 330–344. https://doi.org/10.1177/00195561221141508

Khandker, S.R. (2012) Seasonality of income and poverty in Bangladesh. Journal of Development Economics, 97 (2), 244–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2011.05.001

Koren, O., Bagozzi, B.E. and Benson, T.S. (2021) Food and water insecurity as causes of social unrest: evidence from geolocated Twitter data. Journal of Peace Research, 58 (1), 67–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343320975091

Madama, I., Jessoula, M. and Natili, M. (2014) Minimum income: the Italian trajectory: one, no one and one hundred thousand minimum income schemes. LPF Working Papers, 1. https://air.unimi.it/retrieve/dfa8b99a-9a98-748b-e053-3a05fe0a3a96/WP-LPF_1_2014_Madama-Jessoula-Natili.pdf

Mahmuda, I. (2015) Social safety nets for development: poverty reduction programmes for the provision of food security in Bangladesh. PhD Thesis, Aalborg University, Denmark. https://doi.org/10.5278/vbn.phd.socsci.00030

Masud‐All‐Kamal, M. and Saha, C.K. (2014) Targeting social policy and poverty reduction: the case of social safety nets in Bangladesh. Poverty & Public Policy, 6 (2), 195–211. https://doi.org/10.1002/pop4.67

McDaniel, M., Karpman, M., Kenney, G.M., Hahn, H. and Pratt, E. (2023) Customer service experiences and enrollment difficulties vary widely across safety net programs. Washington, DC: Urban Institute. Available at : https://www.urban.org/research/publication/customer-service-experiences-and-enrollment-difficulties

Mechlem, K. (2004) Food security and the right to food in the discourse of the United Nations. European Law Journal, 10 (5), 631–648. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0386.2004.00235.x

Mohajan, H.K. (2018) Analysis of food production and poverty reduction of Bangladesh. Annals of Spiru Haret University. Economic Series, 18 (1), 191–205. https://doi.org/10.26458/1819

Morshed, K.A.M. (2009) Social safety net programmes in Bangladesh. Bangladesh: UNDP.

Nahid, S.M. (2017) Achieving sustainable social safety nets in Bangladesh. Bangladesh Journal of Administration and Management, 28 (2).

Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A. and Berry, L.L. (1985) A conceptual model of service quality and its implications for future research. Journal of Marketing, 49 (4), 41–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224298504900403

Rahman, M.M. (2012) Estimating the effects of social safety net programmes in Bangladesh on calorie consumption of poor households. The Bangladesh Development Studies, 35 (2), 67–85. h https://doi.org/10.57138/KZBE8083

Ray, D. and Subramanian, S. (2022) India’s lockdown: an interim report. In: Dutta, M., Husain, Z. and Sinha, A.K. (eds.) The impact of COVID-19 on India and the global order: a multidisciplinary approach. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore, pp. 11–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-8472-2_2

Ray, K.K. (2020) Methodology for service quality assessment of social programmes: a framework. Parikalpana: KIIT Journal of Management, 16 (1 and 2), 11–24. https://doi.org/10.23862/kiit-parikalpana/2020/v16/i1-2/204555

Razzaque, A., Ehsan, S.M. and Bhuyian, I.H. (2020) Barriers of accessing social protection programmes for the poor and marginalized. In: A compendium of social protection researches. Dhaka, Bangladesh: Bangladesh Planning Commission, p. 523. Available at: http://socialprotection.gov.bd/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/A-Compendium-of-Social-Protection-Researches.pdf.

Razzaque, M.A. and Rahman, J. (2019) Targeting errors in social security programmes. Policy Insights, 1. Available at: https://policyinsightsonline.com/2019/04/targeting-errors-in-social-security-programmes/

Rumi, M.H., Makhdum, N., Rashid, M.H. and Muyeed, A. (2021) Patients’ satisfaction on the service quality of upazila health complex in Bangladesh. Journal of Patient Experience, 8, 23743735211034054. https://doi.org/10.1177/23743735211034054

Sarker, A.E. and Nawaz, F. (2021) Adverse political incentives and obstinate behavioural norms: a study of social safety nets in Bangladesh. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 87 (1), 60–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852319829206

Shahabuddin, M., Yasmin, M., Alam, A. and Khan, J.U. (2018) Socio-economic impacts of social safety net programs in Bangladesh: old age allowance and allowances for the widow, deserted and destitute women. Research report. Center for Research, HRD and Publication, Prime University. https://www.primeuniversity.ac.bd/file/crhp_details/1677642939.pdf

Shi, Z. and Shang, H. (2020) A review on quality of service and SERVQUAL model. In: Nah, FH., Siau, K. (eds.) Proceedings 22 of the HCI in Business, Government and Organizations: 7th International Conference, HCIBGO 2020, Held as Part of the 22nd HCI International Conference, HCII 2020, Copenhagen, Denmark, July 19–24, 2020, (pp. 188-204). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-50341-3_15

Sifat, R.I. (2021) Social safety net (SSN) programs in Bangladesh: issues and challenges. Journal of Social Service Research, 47 (4), 455–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2020.1839627

Sumarto, S. and Suryahadi, A. (2001) Principles and approaches to targeting: with reference to the Indonesian Social Safety Net Programs. MPRA Paper 58670. Munich: University Library of Munich, Germany. https://ideas.repec.org/p/pra/mprapa/58670.html

Survey of Bangladesh. (2021) Survey of Bangladesh. Government of Bangladesh. Available at: https://www.sob.gov.bd/site/page/85676324-125b-4877-83ae-2bbb4926f7b4/

Tabassum, Z. (2016) Open market sales – a supply side dynamics of two thanas in Dhaka. Master’s Thesis, North South University, Bangladesh. Available at: https://www.northsouth.edu/newassets/files/ppg-research/ppg-1st-3rd-batch/339_Tabassum%20-Open%20Market%20Sale.pdf

The Business Standard. (2025) One tonne wheat flour to be sold in each upazila, 26 August 2025. Available at: https://www.tbsnews.net/bangladesh/one-tonne-wheat-flour-be-sold-each-upazila-1220881

Uddin, M.A. (2013) Social safety nets in Bangladesh: an analysis of impact of old age allowance program. MA dissertation, BRAC University. http://hdl.handle.net/10361/3510

US Department of Agriculture. (2021) Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). Available at: https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program

World Bank. (2014) Social safety nets and gender: learning from impact evaluations and World Bank projects. Washington DC: The World Bank. https://hdl.handle.net/10986/21365

Wu, X., Liu, Q., Qu, H. and Wang, J. (2023) The effect of algorithmic management and workers’ coping behavior: an exploratory qualitative research of Chinese food-delivery platform. Tourism Management, 96, 104716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2022.104716

1 SDG 2: End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture.

2 ‘Monga’ denotes a seasonal episode of severe food insecurity and temporary unemployment in northern Bangladesh, occurring primarily before the Aman harvest.