Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance

Issue 30

December 2025

RESEARCH AND EVALUATION (PEER REVIEWED)

Assessing the Effectiveness of Ghana’s District Performance Assessment Tool: The View from Local Government

Wisconsin International University College, Ghana, Legon, Accra, Ghana, kwesi.addei@wiuc-ghana.edu.gh

Ministry of Local Government, Chieftaincy and Religious Affairs, Accra, Ghana, venyellugh@yahoo.com

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/2y499277

Article History: Received 15/04/2025; Accepted 04/11/2025; Published 31/12/2025

Citation: Mensah, K. A., Venyellu, A. 2025. Assessing the Effectiveness of Ghana’s District Performance Assessment Tool: The View from Local Government. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, 30, 62–78. https://doi.org/10.5130/2y499277

© 2025 by the author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercial, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Abstract

This study investigates the successes and challenges of Ghana’s District Performance Assessment Tool (DPAT) for local governments, and offers recommendations to inform future policy. A descriptive qualitative research design was employed, and 24 staff were purposively sampled. The study found that DPAT has enabled local governments to improve their performance, and acts as a check to ensure that they follow good governance principles and comply with legal regulatory frameworks. The challenges of DPAT include the practicability of indicators, lack of an equitable system of assessment, inadequate understanding of indicators, composition of the national-level steering committee, human resource challenges, and inadequacy and delay in the release of funds. Furthermore, it was found that stakeholder engagement, equity in the assessment of performance, strict compliance with relevant laws, regular monitoring by regional consultative committees, and prompt disbursement of required funds are key factors that can help make DPAT more effective.

Keywords

Performance; Assessment; Local Government; Governance; Ghana; District Assemblies

Introduction

This study investigates the effectiveness of Ghana’s District Performance Assessment Tool (DPAT), which is a nationwide performance assessment instrument for local governments – known in Ghana as metropolitan, municipal and district assemblies (MMDAs). Good local governance is the foundation of successful decentralisation, but it requires strict systems to ensure accountability and performance. The necessity of measures to ensure effective local governance cannot be overemphasised. Citizens, civil society, the media, think tanks and other stakeholders have all reiterated the need for close performance monitoring to ensure the effectiveness and efficiency of Ghana’s MMDAs (Akanbang and Abdallah 2021).

Ghana’s Local Governance Act 2016 (Act 936) puts MMDAs at the forefront of development in their respective areas. Therefore, ensuring their effective performance is core to the development of the country (Akanbang 2024). This explains why the Government of Ghana, in partnership with other agencies has over the years instituted several measures to assess and improve the performance of MMDAs. These include the Community Score Card (CSC), the Citizen Report Card (CRC), the District League Table (DLT), the Functional Organisation Assessment Tool (FOAT), and currently, DPAT (Akolgoma 2019).

The CSC and the CRC were instituted to give citizens the opportunity to assess their assemblies’ performance. These were supposed to report on a quarterly and annual basis. However, they were not effectively implemented, due to both operational problems and apathy on the part of the citizenry. The DLT, an independent tool to enhance social accountability, was initiated by UNICEF and the Centre for Democratic Development in collaboration with Ghana’s Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development1 (MLGRD) in 2014. It ranks districts in terms of education, health, governance, security, water and sanitation (UNICEF and MLGRD 2020).

Prior to the launch of the DLT, the Government of Ghana introduced the FOAT. The FOAT, unlike the DLT, focuses on checking MMDAs’ compliance with the administrative procedures that they are required to follow in performance of their functions (Gourley 2010). The FOAT commenced in 2010 (MLGRD 2010) and information for this assessment was provided by the MLGRD’s District Planning and Coordinating Unit (Gourley 2010). The FOAT later metamorphosed into the DPAT, whose implementation commenced in 2020 using 2019 as the baseline year – despite being officially launched in 2018 (MLGRD 2020).

After a few years of implementation, the DPAT looks promising, but there is not enough documentary evidence on its effectiveness. Considering the key role of decentralisation in the development of Ghana, there is a need for empirical research to evaluate DPAT’s real impact and any problem areas of implementation. Even though it was introduced as an overall framework for evaluating MMDAs (MLGRD 2018), its existence does not necessarily guarantee better local governance. An assessment is needed to determine its effectiveness, capacity constraints and operational challenges. Otherwise, the DPAT may end up as another bureaucratic habit, never realising the accountability and performance gains that it was meant to achieve, and jeopardising the broader goals of Ghana’s decentralisation regime as prescribed under the Local Governance Act. It is therefore imperative to undertake this study, which the authors consider makes a special contribution to the decentralisation literature on monitoring and assessing the performance of sub-national governments. The findings are meant to provide useful policy lessons to enhance DPAT, thereby strengthening a key institution within Ghana’s recentralised local government system.

Literature review

Theoretical review

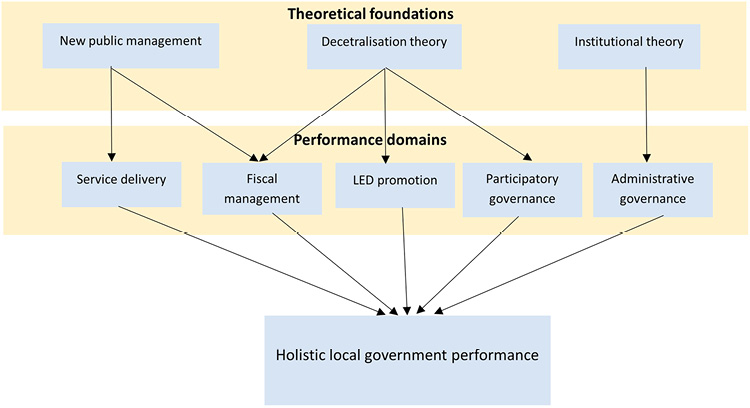

This study employs a tripartite theoretical framework of decentralisation theory, new public management (NPM), and institutional theory to deconstruct DPAT holistically. This three-way perspective enables examination of political, managerial and organisational variables affecting the implementation and performance of the tool within the local government context in Ghana.

Decentralisation theory provides the political context, positing that empowering sub-national governments increases responsiveness and accountability (Bardhan and Mookherjee 2019). From this perspective, DPAT constitutes a logical accountability framework for MMDAs. However, recent literature reveals a paradox: recentralised performance measurement can enable de facto recentralisation (Grossman and Pierskalla 2021), where nuanced data gathering is used as a system for central government control and could be used to curtail local autonomy. The paradox provides the context for the following crucial question: does DPAT empower local governments or enable central control?

New public management provides the design logic of the tool, promoting private-sector philosophies such as results-based management and performance measurement (Hood 1991). As a paradigmatic NPM tool, DPAT seeks to shift MMDA culture from proceduralist compliance to a focus on outcomes (Bouckaert and Halligan 2020). This perspective enables evaluation of the development of a performance culture, while emphasising threats such as ‘goal displacement’ (a situation in which the desire to maximise ‘scores’ outweighs substantive development).

Institutional theory explains organisational responses in terms of legitimacy-seeking action (DiMaggio and Powell 1983). ‘Ceremonial adoption’ (Meyer and Rowan 1977) suggests that MMDAs might adopt DPAT only superficially, to gain resources without internalising its aims. Moreover, ‘institutional complexity’ (Micelotta et al. 2021) is a useful lens to examine how MMDAs navigate conflicting pressures between formal DPAT obligations and informal institutions like political patronage.

Collectively, these theories provide complementary accounts: NPM accounts for DPAT’s design logic, decentralisation theory situates its power dynamics in context, and institutional theory accounts for implementation reality. Together, these theories enable a nuanced analysis beyond technical appraisal to take stock of DPAT’s broader implications for Ghana’s system of decentralised government.

Figure 1. Theoretical foundation of the study (authors’ construct)

Approaches for assessing local government performance

Three general methods are prevalent in measuring the performance of local governments: results-based management (RBM), the balanced scorecard (BSC), and participatory or citizen-centric evaluations.

RBM is widely applied within African public sector organisations with an aim to link inputs, activities, outputs and outcomes to measurable results. It promotes transparency and accountability, but is hindered by weak capacity, flawed data systems, and political interference (Matlala 2025). In the Local Government Service in Ghana, RBM principles are applied via annual performance contracts between the Office of the Head of Local Government Service (OHLGS) and MMDAs, promoting standardisation of performance monitoring as well as service delivery improvement (OHLGS 2023).

The BSC approach connects financial and non-financial metrics by assessing performance from multiple viewpoints such as internal processes, learning, and customer satisfaction. Evidence from Tanzania shows that it encourages clarity of performance, strategic focus and organisational learning, but can be limited by data quality and administrative inertia (Duwe et al. 2023).

Finally, participatory or citizen-centric evaluations – such as Ghana’s 2023 Local Governance Index – place the most importance on citizen views of the effectiveness, transparency and quality of local government services (Institute of Local Government Studies 2024). This method increases accountability and participation but may be skewed by biases or hampered by low levels of civic literacy.

All these methods contribute complementary insights: RBM ensures measurable results, BSC aligns strategy with performance, and participatory assessment ensures accountability is citizen-lived.

The local government system in Ghana

Local government in Ghana after independence in 1957 was bedevilled by several problems, including restricted participation and lack of accountability, which negatively impacted the interest of the general populace in local administration (Bawole and Ibrahim 2017). Local government was perceived as a front to further the interests of central government authority. However, when the Provisional National Defence Council (PNDC) took control of the nation, the system was given a new breath of life (Zakaria 2013). The introduction of local governments, which were to act as the vehicles through which actual authority would be passed to the people, followed the enactment of PNDC Law 207 in 1988 (Bawole and Ibrahim 2017).

The writers of the 1992 Republican Constitution recognised the necessity for a resurrection of local governance under the country’s new democratic political system, and thus they allocated Chapter 20 of the Constitution to local government and decentralisation. However, it should be remembered that the local government structure established by the 1992 Constitution was a rehash of what the PNDC already had in place. According to Article 240(1) of the Constitution, Ghana should have a system of local government and decentralisation that is, as much as possible, decentralised. Article 240(2) of the Constitution directs Parliament to pass the necessary legislation to guarantee that “functions, powers, responsibilities, and resources are at all times transferred from the Central Government to local units in a coordinated manner” (Republic of Ghana 1992).

Currently, the primary statute governing local government in Ghana is the Local Governance Act 2016 (Act 936), which replaced the Local Government Act 1993 (Act 462). The system consists of regional coordinating councils (RCCs), a three-tier municipal/district structure, and a four-tier metropolitan structure.

Assessment of the performance of sub-national governments

Measuring the performance of sub-national governments is not new; it is as old as the concept of local government itself. However, over time governments in many countries have increasingly focused their attention on performance measurement, budgetary output and outcome evaluation (Alibegović and Slijepčević 2010). Performance measurements became very popular during the NPM era (Hood 1995; Pollitt and Bouckaert 2004), and Melkers and Willoughby (2005) suggest that performance measurements become increasingly important as fiscal decentralisation is strengthened and local governments take responsibility for significant budgetary decisions.

Several countries have instituted performance assessment schemes for their sub-national governments. Croatia, for instance, instituted the Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability Public Financial Management Performance Measurement Framework, which worked very well for them (Alibegović and Slijepčević 2010). In Vietnam, there is the Vietnam Provincial Governance and Public Administration Performance Index, which according to Malesky et al. (2022) has led to improved governance. The EPPD (Evaluasi Penyelenggaraan Pemerintahan Daerah) of Indonesia, which was supported by USAID, is another successful performance evaluation framework (USAID-ERAT 2023). There are similar schemes across the developing and the developed world that have improved the performance of sub-national units. In Africa, mention can be made of the performance management system developed by the Government of South Africa to improve productivity and effectiveness in local government, aiming to address inefficiency, unproductiveness and incompetence among public servants (Mdleleni 2023).

The District Assembly Performance Assessment Tool

In Ghana, DPAT is a diagnostic instrument for assessing the performance of MMDAs and for determining their funding allocations under the District Assemblies Common Fund (DACF) Responsive Factor Grant (RFG) (MLGRD 2018). MLGRD and its partners have considerably revised the DPAT indicators since DPAT’s launch in 2018. The focus of the new indicators is now on evaluating each MMDA’s efforts to enhance service delivery to the public. The redesigned DPAT indicators and structure have been developed in accordance with a new formula, which identifies three components for a successful performance-based grant system: performance indicators, service delivery indicators, and compliance indicators (MLGRD 2019).

Methodology

This study employed a descriptive qualitative research design for data gathering and analysis. This enabled the researchers to gain better insights into the issues, answer the research questions more fully, and gather rich description (Creswell and Poth 2018; Islam and Aldaihani 2022) – in this case, in relation to DPAT’s performance and challenges. The study targeted the district planning coordinating units (DPCUs) of the 261 MMDAs across the country, whose key officials include the district coordinating director, district planning officer/assistant, district budget officer/analyst/assistant, district finance officer/assistant and development planning sub-committee chair. Sampling was multi-staged. Twenty-four MMDAs were randomly selected using the lottery method, to ensure a fair representation of the districts. However, interview respondents were then purposively selected. Only DPCU members were selected, since their activities directly relate to the implementation of DPAT.

An interview guide was designed and used as the primary data collection tool. The guide had 16 questions within three themes: performance assessment at the local level and use of DPAT; effectiveness of DPAT; and implementation challenges of DPAT. A voice recorder, notebook and pen were also employed in the data collection process. First, participants were introduced to the purpose of the study through an email and asked to sign a consent form if they wished to participate. Following receipt of the consent form, interviews were scheduled and undertaken over the phone. Each interview lasted approximately 35 minutes and the entire data collection process spanned a period of three and a half weeks (1–25 April 2023). Data gathered was initially transcribed and coded and then analysed. Although there were some a-priori codes, additional codes were generated from the transcripts. The coded elements were then grouped into three main themes: performance assessment at the local level and use of DPAT; effectiveness of DPAT; and implementation challenges of DPAT.

Ethical safeguards such as informed consent, confidentiality and respondent anonymity were strictly adhered to. Permission was sought from respondents before recording and they were assured that recorded information would only be handled by researchers. Respondents were referred to as ‘Officer 1’ through to ‘Officer 24’ to maintain anonymity and confidentiality.

Findings

The study involved 24 interviewees. Respondents were drawn from 14 of the 16 regions in the country.

Source: Authors’ field survey report (2023)

The two regions with the highest number of participants were the Eastern region (5), followed by the Ashanti region (4). The majority of participants were stationed in municipal assemblies, compared to district and metropolitan assemblies with nine and one participant(s) respectively. Twenty of the participants, a clear majority, were male while four were female. The age distribution of participants ranged from 38 to 53. Furthermore, participants had a range of years’ experience, with four years being the minimum and 21 the maximum.

Performance assessment in local government and the use of DPAT

This section addresses the first of the three main themes under which the study’s findings are presented. The areas of focus regarding the findings are knowledge of DPAT, its objectives, and the role of assemblies; and the effectiveness of DPAT as an enabler of performance improvement.

Knowledge of DPAT, its objectives, and the role of assemblies

The findings revealed that all participants had an appreciable knowledge of DPAT and its objectives, and they felt that assemblies have a role to play to ensure the successful implementation of DPAT. They understood DPAT as an assessment tool and indicated that its foremost objective is to promote the effective delivery of the mandate of assemblies. Some participants had this to say:

The purpose of DPAT is to assess MMDAs in terms of their core mandates. To see whether we are really, uh, doing our work in terms of service delivery, and the performance and compliance deliverables, all that. And the funding they give to assemblies who are scored well in the assessment is also to help the assemblies implement their activities in their action plan and to strengthen the assembly in terms of development and capacity building (Officer 9).

DPAT is a performance assessment tool. The objective is one, build the capacity of the assemblies at the end of the day. There’s also a capacity grant component and when the assembly is able to pass and receive the funds, they can use part of the fund to build their capacity and also for investment purposes for developmental issues of the assembly (Officer 6).

The study found that, beyond participants perceiving assemblies as key stakeholders in the implementation of DPAT, they also see DPAT as a process rather than an event. The assemblies have to ensure that the necessary requirements are met, as explained by these participants:

An important role of assemblies in the implementation of DPAT Is to ensure that our mandate as enshrined in the Local Governance Act is performed to the letter so as to satisfy the assessment requirements.

I believe that the assembly is supposed to partake or prepare adequately in terms of preparing its documentation and ensuring that the activities that are outlined in the various Acts, laws and work plans that we are supposed to undertake during the year under review are done and records are adequately available for us to prove such. … It is also mandated on us to attend stakeholders’ engagement to make known our reservation or issues, if any.

DPAT as an enabler of performance improvement

The study found that participants have high expectations of DPAT and accordingly set high targets for every new DPAT assessment. While some respondents indicated that assemblies perceive DPAT as a competition and wish to stand out as high performers when the results are published, others indicated that assemblies were more financially motivated; they want to improve performance in order to receive more funding. Also, respondents reported that the thought of DPAT keeps assemblies on their toes and gets them to work extra hard, because the indicators on which they are assessed change from time to time.

Besides promoting enthusiasm and high performance goals, the study found that DPAT has encouraged assemblies to adhere to good governance principles and comply with regulatory frameworks such as holding general assembly, management and executive committee meetings; organising ‘townhall’ forums; and setting up and empowering sub-committees. The study also found that the majority of participants felt their department’s performance in relation to their mandate under the Local Governance Act had improved, particularly around service delivery:

By providing financial resources and capacity building, [DPAT] has improved promptness and completion of projects, and enabled the district assembly to provide improved services to the citizenry (Officer 3).

DPAT has enhanced efficiency and prioritisation in service delivery by the assembly to the people. It has provided finance for the provision of especially physical projects which would have been difficult for the assembly to do with IGF [internally generated funds]. These have encouraged the assembly to be up to the task and to go the extra mile to enhance service delivery. I dare say that within a year if we depend solely on IGF, it would be very, very difficult for us to undertake any meaningful project when it comes to the assembly’s activities in terms of service provision (Officer 4).

However, the findings also revealed that, although DPAT has improved the performance of assemblies in the delivery of their mandate, it has not led to a significant improvement in overall productivity or widespread development at the local level. The two main reasons stated by participants as responsible for this situation are lack of adequate funds, and the limited technical and administrative capacity of some assembly staff. Respondents reported, for example, that MMDAs are being starved of funds by central government and sometimes struggle to meet even basic statutory requirements such as organising ordinary or general assembly meetings. It appears that assemblies have limited resources to finance their annual action plans and meet citizen expectations:

When you are expected to carry out certain monitoring or supervisory activities within your jurisdiction, you are required to have logistics such as vehicles to be able to do that. But most assemblies, if I’m not wrong, about 40% of our assemblies lack the adequate logistics such as vehicles to go on such exercises. IGF helps some assemblies, but for poor assemblies like mine we rely on the District Assemblies Common Fund (DACF).2 However, Common Fund is no more common (Officer 12).

Some assemblies are not even able to fund general assembly meetings; usually they have to do so on credit. If you come to an assembly such as mine that has a large number of over 30 assembly members, and you are supposed to fund general assembly meetings at least three to four times a year, we struggle to organise it because we have to pay allowances and feed these people (Officer 6).

An important insight from this study is the perceived potential of DPAT to improve public sector performance in ways relevant to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Stakeholder perceptions indicate that DPAT may enhance performance monitoring and evaluation, strengthen accountability mechanisms, and facilitate more efficient resource allocation. By providing timely performance-related information, DPAT is considered capable of supporting evidence-informed decision-making within the public sector. However, these findings are based on respondents’ experiences and perceptions rather than direct measurement of SDG outcomes. Therefore, DPAT is positioned as a promising institutional tool whose alignment with national development objectives requires further investigation using SDG-specific indicators and outcome-based measures.

Implementation challenges of DPAT

Under this theme, the challenges identified include the practicability of indicators, lack of an equitable system of assessment, inadequate understanding of indicators, composition of the national-level steering committee, human resource challenges, and inadequacy and delay in the release of funds.

Practicability of indicators

Respondents reported that some DPAT indicators are not practical. For example, some assemblies are newly created, so lack experience, while others have a low level of development – in both cases meaning they are not able to meet the requirements of some indicators. The study also found that in some cases it is difficult for the assemblies to collaborate with Electricity Company of Ghana and the Ghana Water Corporation as they are mandated to, because these agencies are not obliged to report to the assembly:

Some of the indicators are good on paper but are not really practical on the ground. For some, their practicality is a bit difficult. For example, at my place like this, most of the institutions that you are expected to collaborate with for you to make the mark for DPAT don’t exist in my jurisdiction. So, you must go far for you to collaborate. And that’s one key issue that troubles us (Officer 20).

Lack of an equitable system of assessment

The majority of participants felt there was a lack of equity in the implementation of DPAT. They complained that rural assemblies, for example, are disadvantaged by the practice of assessing all assemblies with the same indicators, irrespective of their size or level of development. Some specifically mentioned the performance and service delivery indicators, which make resource-rich and urban districts appear better than their rural and resource-deficient counterparts. They argued that assemblies should be assessed on the basis of their relative strengths:

You know, assemblies are not the same. The capacities are different, but we’re assessed using the same indicators. A district in Upper West compared to a district in say, Ashanti Region or even Tamale, you know that it varies. Yeah. So, sometimes it is not fair. From my point of view, it’s not fair enough (Officer 7).

To address this, some respondents proposed that MLGRD3 should group assemblies into three sets (developed, developing, and underdeveloped assemblies) according to an established standard and develop different indicators for assessing each group.

They suggested the ministry should strive to achieve equality of outcome, by ensuring that all assemblies have an equal opportunity to access the funds needed to develop their communities:

The ministry should consider a new way of assessing the different categories of assemblies. At the ministry level, they know that assemblies are into categories. We have Category A assemblies, we have Category B assemblies, and we have Category C assemblies, so all of us should not be assessed on the same templates (Officer 8).

Inadequate understanding of indicators

The study identified that ambiguous descriptions of performance indicators contribute to misunderstandings between MMDAs and assessment teams. For example, the definition of a ‘functional committee’ was frequently disputed. Assessors required recent meeting minutes as evidence of functionality, whereas some assemblies maintained that the committee’s existence alone was sufficient. Additionally, some consultants misinterpreted assessment guidelines, which was attributed to limited familiarity with the Local Governance Act 2016, or, in some cases, to a perceived bias. One respondent asserted that:

The quality assurance team intentionally broadened indicator requirements, such as requesting additional years of documentation, to lower assessment scores. This undermines the credibility and fairness of the evaluation process (Officer 11).

Composition of the national-level steering committee

MMDA coordinating directors are not currently members of the DPAT steering committee. Some respondents felt this poses a challenge to the successful implementation of the programme, as coordinating directors have vast local governance experience and their input at the planning stages could help shape the assessment process. Currently, however, everything is usually decided before assessors engage with the assemblies. Participants claimed that this situation hampered the programme, as it makes it difficult for the ministry to incorporate their suggestions early enough:

If a body like NALAG [National Association of Local Authorities of Ghana] is represented, that’s for the assembly members, [then] why are coordinating directors who are at the centre of the administration of district assemblies not being given representation at the steering committee? If coordinating directors have representation on the committee, some of the decisions could be critiqued and made practical (Officer 12).

Human resource challenges

Another challenge identified by the study is human resources. Some MMDAs experience challenges with DPAT because they do not have staff with the required training or capacity. This is a long-standing concern within the assembly system. Many assemblies have high staff numbers, but not in the roles where they are needed most:

We seem to have overstaffed most of the assemblies, but what happens is that you get an assembly that’s about 200 staff, but the problem is that the staffing norm is not being adhered to. So, you see an assembly having about 18, 20 administrators and there’s just one or no physical planning officer. So, it would look like they have the numbers, but as to whether they are in the right places or the right department, that is where the human resource challenge comes in (Officer 15).

Inadequacy and delay in the release of funds

Respondents reported delays in the disbursement of DACF-RFG funds to MMDAs for the execution of projects and programmes, and also reductions in amounts transferred. Additionally, some participants stated that they no longer receive funds for capacity training:

It is, like, ‘Some of the donors are not contributing again’. I wonder. Last October, for example, we did our plan and budget, I think the ceiling was 1 million plus, but the actual allocation was around GHS700,000 from the publication that came. We don’t understand why. The capacity building requirements too, when they come to assess you, they look at areas that you need improvement and then they will recommend in consultation with the assembly so that you can use that money to build those capacities. That one too is not coming again (Officer 1).

Study participants recommended that funds should be disbursed promptly, noting that delays always have repercussions for project implementation, which in turn impacts compliance and performance indicators:

The ministry should always try as much as possible to make resources available to the assemblies promptly because every resource is tied to a budget. And then the budget, if you have your budgetary allocation, you can effectively implement whatever programme that you are supposed to do within the particular timeframe (Officer 22).

Key factors for the implementation of efficient performance assessment

This section focuses on the third objective of the study: factors that can help make DPAT more effective as a performance management tool. The key factors identified were stakeholder engagement, strict compliance with relevant laws in the performance of functions, and regular monitoring by RCCs.

Stakeholder engagement

The study findings suggest that stakeholder engagement is essential to guarantee effective performance management. Stakeholder involvement should start as soon as a revision to the indicators is being considered, and it should include, among other things, asking assemblies for their opinions on suggested adjustments or the reliability of indicators. Respondents felt this would help MLGRD to proactively consider the needs and concerns of assemblies, which in turn will foster trust, and promote their buy-in and confidence in the indicators:

My recommendation is that, before or prior to the development of the indicators, there should be stakeholder engagement with the assemblies. The scope of the engagement should be on the functions of assemblies as it relates to DPAT, and the laws regulating our mandate (Officer 5).

Strict compliance with relevant laws in the performance of functions

It was recommended that, to achieve and sustain success in performance assessments, assemblies must endeavour to always comply with the laws and policies that regulate the performance of their mandate:

Religiously following regulatory policies and laws that guide our mandate is a critical factor in ensuring success in performance assessments. The best practice is to comply with all laws governing the things we are mandated to do. Sadly, we do not refer to such laws until maybe there is an issue. Knowing the laws about your work makes you an efficient and effective worker. We must religiously update ourselves with our mandate, I believe so (Officer 18).

Regular monitoring by RCCs

Participants reported that it would be helpful if RCCs undertook regular monitoring of assemblies, as they would then be able to identify staff skill gaps more efficiently, and close them with new training programmes. This would guarantee that the training assembly workers receive is appropriate for their current skill set and the objectives of the assembly. Additionally, respondents felt it would help if RCCs could undertake ‘test’ performance assessments, at least twice a year, to boost assemblies’ performance or delivery.

I believe RCCs should be more proactive in supervising and monitoring the activities of their assemblies. So, their constant monitoring of our activities would help us always be ready for any form of assessment, including that of the DPAT, and make sure that we are always in good standing in terms of that. These measures will go a long way in helping the assemblies to improve our performance and pass the assessment (Officer 3).

Having RCCs undertake DPAT-like assessments twice a year will help assemblies improve service delivery. This is because anytime that DPAT is coming, you begin to peer review yourself. So, when it comes off once a year, then people relax until when it’s coming off again, then we will begin to do things right and make sure that we produce the records to cover the work done (Officer 13).

Discussion

The importance of local governments to national development cannot be overemphasised. They are crucial. Their role in making development responsive and participatory has contributed to good governance at the local level. This study complements other studies on the same topic. For example, Jurnali and Siti-Nabiha (2015) assessed the effectiveness of the performance management system for Indonesian local governments, and realised that one major reason the system has not been very effective is that local actors were not involved in its development and thus do not ‘own’ it. By contrast, the current study shows that, to a large extent, in Ghana the MMDAs do ‘own’ DPAT because they were involved in the development of the indicators (see also Mensah et al. 2024). Respondents are well aware of the tool as well as its importance. Although there were suggestions made to improve the indicators, such suggestions are to be expected, and a positive development, in an era of continuous improvement.

Nevertheless, this study did reveal that some indicators were contested and considered not to be properly targeted. This mirrors findings in Indonesia by Jurnali and Siti-Nabiha (2015), and also by Ahenkan et al. (2018) when they studied Ghana’s Sefwi Wiawso Municipal Assembly. At the theoretical level, Andersen and Nielsen (2020) have emphasised the need to properly align indicators so they do not lead to a situation where the metric supersedes the underlying objective of the assessment.

These design issues are compounded by the capacity constraints which are ubiquitous at both central and local level. The observation that some consultants do not have comprehensive knowledge of the Local Governance Act 2016 indicates a major flaw in the human resources needed for DPAT implementation. The situation at the assembly level is worsened by the severe logistical and financial constraints reported. These resource limitations have over the years created a vicious cycle of underperformance; a phenomenon well documented in the literature on African public administration (Owusu and Ohemeng 2012; Ahenkan et al. 2018; Ayee 2020). This finding corresponds directly to the severe logistical constraints identified in Ghana’s Ada East District by Sosu (2019), suggesting that this is a systemic, rather than localised, problem.

It is worth noting that if the aforementioned technical and capacity problems are not appropriately addressed, this could lead to a considerable reduction of trust and ownership. If stakeholders consider a system to be unfair or punishing, they either become only symbolically compliant, or simply resist it, thus preventing organisational learning (Moynihan 2018). The ‘rebuttals’ and the frustrations that participants in this study have expressed indicate that for some DPAT might not be seen as an improvement tool, but rather as a mechanism for central control and sanction, thereby stifling the very innovation and accountability it aims to promote (Grossman and Pierskalla 2021).

Implications for policy and practice

These findings suggest the need for a participatory reworking of the DPAT indicator framework with joint input from assemblies, central government and other stakeholders. It is also essential that all consultants are required to be certified, and must receive mandatory and continuous training on DPAT’s relevant laws and documents as well as its assessment protocols, in order to maintain consistency and fairness. The focus of DPAT should be collaboration and not competition – for example through pre-assessment support visits and the establishment of a knowledge-sharing platform for best practices. Additionally, fundamental resource gaps must be tackled so that assemblies receive more regular and direct fiscal transfers, enabling them to, as a minimum, execute the functions which are being evaluated.

Conclusion

It seems clear that DPAT is a well-known performance assessment tool among district assemblies, its objectives are valued, and it enjoys the support of MMDAs. The authors believe therefore that it will remain relevant as a performance assessment tool in Ghana for a long time. One of the findings that reinforces this conclusion is the evidence from stakeholder perceptions suggesting that DPAT may support institutional practices that are aligned with the broader objectives of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

However, although DPAT has improved the performance of assemblies in the delivery of their mandate, it has not translated into significant improvements in overall productivity or widespread local development. The two main reasons identified for this are the lack of adequate funds and the poor capacity of staff.

Nevertheless, DPAT has enormous potential if the identified implementation challenges can be effectively addressed. Stakeholders must work together to promote stakeholder engagement, equity in the assessment of performance, strict compliance with relevant laws in the performance of functions, regular monitoring by RCCs, and prompt disbursement of required funds. If these can be achieved, DPAT has a very bright future.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship or publication of this article.

References

Ahenkan, A., Tenakwah, E.S. and Bawole, J.N. (2018) Performance management implementation challenges in Ghana’s local government system. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 67 (3), 519–535. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPPM-06-2016-0124

Akanbang, B.A.A. (2024) Local government monitoring system’s design and implementation in Ghana from the lens of the project life cycle. SAGE Open, 14 (4). https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440241293884

Akanbang, B.A.A. and Abdallah, A.I. (2021) Participatory monitoring and evaluation in local government: a case study of Lambussie District, Ghana. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, (25), 40–55. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi25.8037

Akolgoma, A.F. (2019) Performance of the Sekyere Kumawu District Assembly from the communities’ perspective. M.Phil. thesis, University of Cape Coast.

Alibegović, D.J. and Slijepčević, S. (2010) Performance measurement at the subnational government level in Croatia (EIZ Working Paper No. 2). Croatia: Institute of Economics, Zagreb.

Andersen, S.C. and Nielsen, H.S. (2020) Learning from performance information. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 30 (3), 415–431. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muz036

Ayee, J.R.A. (2020) Manifestations of administrative weaknesses in Africa’s public sector: implications for reform. The Round Table, 109 (3), 301–317.

Bardhan, P. and Mookherjee, D. (2019) Local governance and accountability in developing countries. Annual Review of Economics, 11, 301–327. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-economics-080218-025823

Bawole, J.N. and Ibrahim, M. (2017) Value-for-money audit for accountability and performance management in local government in Ghana. International Journal of Public Administration, 40 (7), 598–611, https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2016.1142999.

Bouckaert, G. and Halligan, J. (2020) Performance management in the public sector. (4th ed). London, England: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429029780

Creswell, J.W. and Poth, C.N. (2018) Qualitative inquiry and research design choosing among five approaches. (4th ed). Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc.

DiMaggio, P.J. and Powell, W.W. (1983) The iron cage revisited: institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48 (2), 147–160. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095101

Duwe, A.B., Barongo, F. and Mallya, E. (2023) Effectiveness of balanced scorecard: experience from selected public organizations in Tanzania. National Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Development, 8 (2), 165–169.

Gourley, G. (2010) Evaluating the Functional & Organisational Assessment Tool (FOAT) process. Briefing paper. EWB West Africa Operations – Ghana. Available at: https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/view/34841660/evaluating-the-functional-organizational-assessment-tool-process

Grossman, G. and Pierskalla, J.H. (2021) Decentralization and development. Annual Review of Political Science, 24, 311–334. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-041719-101841

Hood, C. (1991) A public management for all seasons? Public Administration, 69 (1), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.1991.tb00779.x

Hood, C. (1995). The ‘new public management’ in the 1980s: variations on a theme. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 20 (2–3), 93–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/0361-3682(93)E0001-W

Institute of Local Government Studies. (2024) 2023 Local Governance Index (LOGIN): residents’ assessment of their local government authorities in Ghana. Institute of Local Government Studies. https://ilgs.edu.gh/media/ckimages/2024/05/04/4ilgs-login-reportfinal-3-5-2024.pdf

Islam, M.A. and Aldaihani, F.M.F. (2022) Justification for adopting qualitative research method, research approaches, sampling strategy, sample size, interview method, saturation, and data analysis. Journal of International Business and Management, 5 (1), 01–11. https://doi.org/10.37227/JIBM-2021-09-1494

Jurnali, T. and Siti-Nabiha, A.K. (2015) Performance management system for local government: the Indonesian experience. Global Business Review, 16 (3), 351–363. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972150915569923

Malesky, E., Phan, T.-N. and Le, A.Q. (2022) Do subnational performance assessments lead to improved governance? Evidence from a field experiment in Vietnam. Fulbright Review of Economics and Policy, 2 (2), 117–135. https://doi.org/10.1108/frep-02-2022-0006

Matlala, L.S. (2025) Barriers to the institutionalisation of outcome-based approaches in South Africa’s public sector. Africa’s Public Service Delivery & Performance Review, 13 (1). https://doi.org/10.4102/apsdpr.v13i1.939

Mdleleni, L. (2023) The advancement of Sustainable Development Goal 16: an analysis of performance management systems in South African local government. Journal of Public Administration, 5 (1), 18–24. https://doi.org/10.22259/2642-8318.0501003

Melkers, J. and Willoughby, K. (2005) Models of performancemeasurement use in local governments: understanding budgeting, communication, and lasting effects. Public Administration Review, 65 (2), 180–190. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.15406210.2005.00443.x

Mensah, J.V., Aikins, A.E. and Essaw, D.W. (2024) Analyzing the District Performance Assessment Tool in local governments in Ghana. R-Economy, 10 (3), 302–313. https://doi.org/10.15826/recon.2024.10.3.019

Meyer, J.W. and Rowan, B. (1977) Institutionalized organizations: formal structure as myth and ceremony. American Journal of Sociology, 83 (2), 340–363. https://doi.org/10.1086/226550

Micelotta, E.R., Lounsbury, M. and Greenwood, R. (2021) Pathways of institutional change: an integrative review and research agenda. Journal of Management, 47 (1), 122–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206320903215

Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development. (MLGRD) (2010) Functional & Organisational Assessment Tool (FOAT) – operational manual. Accra: MLGRD.

Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development. (MLGRD) (2018) Operational manual for the District Assembly Performance Assessment Tool (DPAT), 1st cycle (Baseline year: 2016, implementation year: 2018). Accra, Ghana: MLGRD.

Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development. (MLGRD) (2019) Operational manual for the District Assembly Performance Assessment Tool (DPAT), 2nd cycle (Baseline year: 2017, implementation year: 2019). Accra, Ghana: MLGRD.

Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development. (MLGRD) (2020) Ministry completes integration of District Development Facility; DPAT replaces FOAT. Accra, Ghana: MLGRD.

Moynihan, D.P. (2018) Performance management: the state of the art. In: Ongaro, E. and Van Thiel, S. (eds.) The Palgrave handbook of public administration and management in Europe. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 235–252.

Office of the Head of Local Government Service. (OHLGS) (2023) 2023 Annual local government service performance evaluation report of RCCs & MMDAs. Local Government Service. Available at: https://lgs.gov.gh/2023-annual-local-government-service-performance-evaluation-report-of-rccs-and-mmdas/

Owusu, F. and Ohemeng, F.L.K. (2012) The public sector and development in Africa: the case for a developmental public service. In: Hanson, K.T., Kararach, G. and Shaw, T.M. (eds.) Rethinking development challenges for public policy: insights from contemporary Africa. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 117–154. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230393271_5

Pollitt, C. and Bouckaert, G. (2004) Public management reform: a comparative analysis. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780199268481.001.0001

Republic of Ghana. (1992) Constitution of the Republic of Ghana. Accra: Assembly Press.

Sosu, J.N. (2019) Performance management in Ghana’s local government: a case study of Ada East District Assembly. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, (22), Article ID 7376. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi22.7376

UNICEF and Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development. (2020) District league table VII: Strengthening social accountability for improved service delivery in Ghana. Accra, Ghana: UNICEF Ghana.

USAID-ERAT. (2023) FY 2023 Annual report: improvement of evaluation of subnational government implementation [Evaluasi Penyelenggaraan Pemerintahan Daerah, EPPD]. USAID ERAT Indonesia.

Zakaria, H.B. (2013) Looking back, moving forward: towards improving local governments’ performance in Ghana. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, 13&14, 90–108. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.v0i13/14.3726

1 Now called the Ministry of Local Government, Chieftaincy and Religious Affairs.

2 DACF is a constitutionally mandated funding arrangement that requires the central government of Ghana to allocate not less than 5% of national revenues to MMDAs to support local development. It serves as a key instrument for fiscal decentralisation by providing predictable transfers for service delivery and infrastructure at the local level (Republic of Ghana 1992 (Article 252)).

3 Now called the Ministry of Local Government, Chieftaincy and Religious Affairs.