Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance

Issue 28

September 2023

POLICY AND PRACTICE

The Impact of New Public Management Reforms on the Delivery of Secondary Education in Tanzania

Wilfred Lameck

School of Public Administration and Management, Mzumbe University, Morogoro, Tanzania, wlameck@mzumbe.ac.tz

Chagulani Shabiru

Mzumbe University, Morogoro, Tanzania, shabiruchagulani20@gmail.com

Corresponding author: Wilfred Lameck, School of Public Administration and Management, Mzumbe University, Morogoro, Tanzania, wlameck@mzumbe.ac.tz

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi28.8818

Article History: Received 23/06/2022; Accepted 23/08/2023; Published 25/09/2023

Citation: Lameck, W., Shabiru, C. 2023. The Impact of New Public Management Reforms on the Delivery of Secondary Education in Tanzania. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, 28, 122–131. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi28.8818

© 2023 by the author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercial, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Abstract

This article discusses the impact of adopting New Public Management (NPM) reforms in the delivery of education services via a case study of the experience of Mwanza City, Tanzania. The case study reveals that NPM reforms, which came with new guidelines for the delivery of education services, have reduced the capacity and discretion of education officers and teachers in the delivery of education services. Furthermore, education services are confronted with scarcity of teaching and learning resources including classrooms, teachers, textbooks and laboratory equipment. Despite the good intentions of the NPM reforms in the education sector, the authors argue that the discretion of education officers and teachers should be protected as an essential tool to translate policies into reality.

Keywords

New Public Management; Education; Street-Level Bureaucrats; Discretion; Tanzania

Introduction

In Tanzania, like other countries across the globe, New Public Management (NPM) reforms have been introduced over the past three decades to address problems of inefficiency, ineffectiveness and corruption in the public sector (Mukandala and Shellukindo 1994; United Republic of Tanzania [URT] 2013). They featured reductions in bureaucracy; decentralisation of authority to managers;and the use of private sector techniques such as public–private partnerships, competition among service providers, results-oriented approaches and performance measurement (Hughes 2003; Bach et al. 2007). However, Paulsen (2018) argues that the application of NPM has curtailed the exercise of discretion at different levels within organisations due to orders received ‘from the top’. In Tanzania’s education sector, NPM reforms involved new directives, guidelines and instructions to guide the implementation of public polices and in particular the work of teachers. This means that Tanzania’s teachers, who are ‘street-level bureaucrats’ needing to exercise significant discretion in the way they perform their role in order to achieve the best possible results (Gupta et al. 2022), may be hampered by excessive rules, regulations and direction from central government. They now face heavy workloads along with the need to comply with new regulations and performance standards. This raises questions about how the NPM reforms have affected and shaped the performance of teachers in the delivery of secondary education; and how they have responded to the changing demands of the central government.

Potential impact of New Public Management reforms

The New Public Management approach aims to transform traditional public administration by means of a market orientation in public services, increased flexibility and transparency, and a move to ‘small government’ including de-bureaucratisation, decentralisation and privatisation. It is a process of implanting the liberal market principles of efficiency and economy in the public sector to make it more effective (Biswas 2020). Key tenets are the philosophy of managerialism, which implies the adoption of private sector management techniques in the public service, along with organisational restructuring and new institutional economics featuring competition, public choice and principal-agent theories. The goal is to enhance efficiency in public sector management and position the economic market as a model for political and administrative relationships (Hood and Jackson 1991; Economic Commission for Africa 2004).

However, the literature on NPM reforms, particularly in developing countries, reveals negative impacts in public sector service delivery, specifically the limited autonomy and discretion of street-level bureaucrats such as teachers (Evans and Harris 2004; Brodkin 2011). Implementing the reforms has created new organisational environments that affect the way street-level bureaucrats respond to top-down demands and also their ability to preserve their needed autonomy as professionals (Ackroyd et al. 2007).

The public administration literature also suggests that the way members of an organisation respond to NPM reforms may be shaped by the organisation’s existing culture and prevailing work norms as well as the absence or presence of strong occupational and professional communities (Sandfort 2000; Riccucci 2005). This includes the development of new coping strategies (Durose 2009; Tummers et al. 2013). Overall, previous studies have found that the professional values and institutions of organised professions mediate top-down demands and may enable the preservation of professional autonomy under NPM reforms (Ackroyd et al. 2007).The discretion of street-level bureaucrats is determined not only by formal roles and structures but also by the informal structures and culture within bureaucracies which create an institutional context for maintaining professional norms and a client-focused approach to making the best decision (Lipsky 2022; Liljegren 2012; Lameck and Hulst 2019; Gupta et al. 2022).

Tanzanian context

National policy and local education plans

With the development of its NPM reforms, Tanzania’s national government adopted a new education policy in 2014 to replace the old policy of 1995. The purpose of the 2014 policy was to increase stakeholder participation in the delivery of education services, particularly the private sector, civil society organisations and development partners, alongside several other goals: implementation of policy and programmes with reliable performance indicators for education services; monitoring and evaluation of performance; building the capacity of the implementing ministries; and using the performance measurement results and research to increase efficiency in service delivery (URT 2014). The heads of schools and colleges have the responsibility to supervise implementation of the policy at the local level, subject to a local education plan (URT 2016b) (see below).

The case of Mwanza City

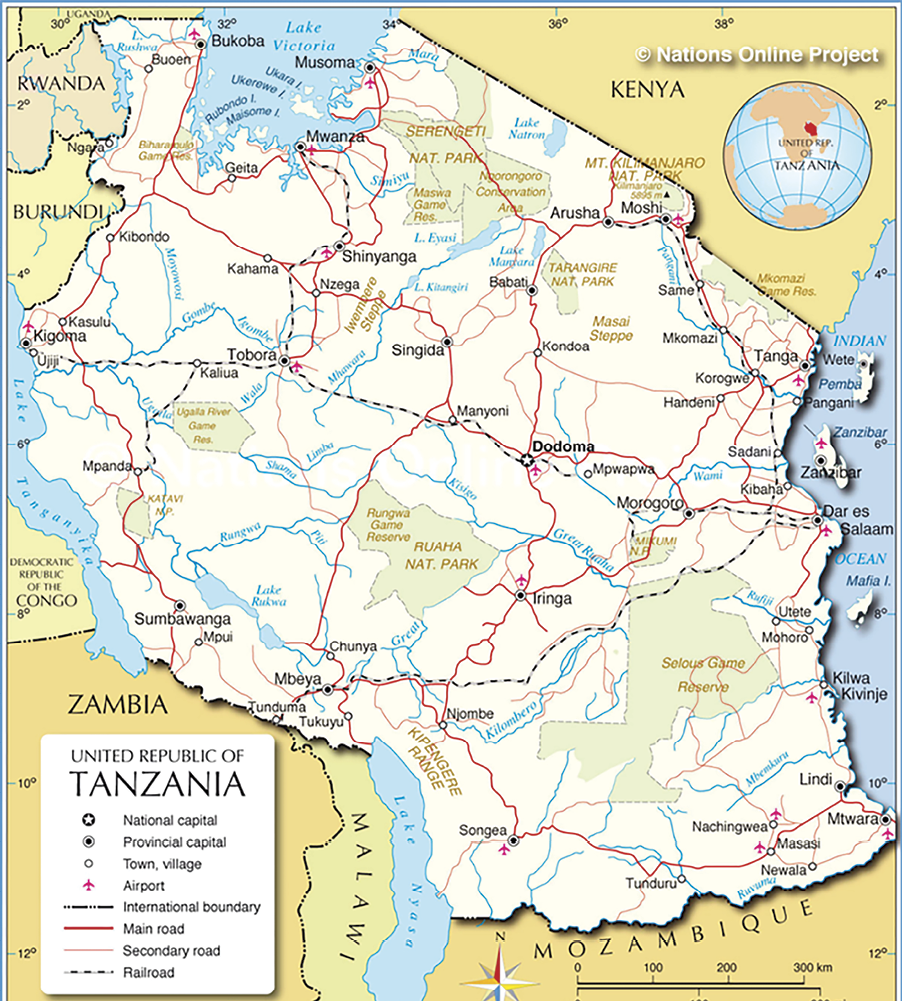

Mwanza, located in the country’s north-west on the shores of Lake Victoria (see Figure 1) is one of the largest cities in Tanzania. In 2012 the city had a population of about 2.8 million (it is now 11 years since the last census was conducted), with a huge enrolment of students in public secondary schools.

Figure 1. Location of Mwanza City

Source: https://www.nationsonline.org/oneworld/map/tanzania-political-map.htm

Politically, the council is under the leadership of a mayor elected every five years, while administratively it is managed by a city director who is appointed by the president under Tanzania’s Public Service Act 2002. In performing their duties, the city director works with 13 heads of department and six heads of unit. At a lower level, there are 18 wards; these are administrative sub-units under which are 175 ‘streets’ – the lowest level of local government.

In order to carry out its activities, like other cities Mwanza develops a five-year strategic plan (URT 2016a), which is required to be consistent with Tanzania’s national development plan (Tanzania Five Years Development Plan 2016/2017–2020/2021) and overall national direction (Tanzania Development Vision 2025; Long-Term Perspective Plan 2011/2012–2025/2026) (URT 2016b).

The secondary education department in Mwanza, which is the subject of this paper, has a wide range of functions and objectives including provision of quality education, increasing access to and equity in secondary education, improving the performance of students, ensuring student enrolment in each academic year, monitoring and evaluating the education syllabus, and coordinating examinations.

To achieve these objectives the functions of the department also extend to: preparing education plans consistent with the city’s strategic plan; providing seminars and workshops to teachers for capacity building; and ensuring timely disbursement of financial resources (URT 2016a). At the same time, the city is required to comply with directives and guidelines issued by the Ministry of Education, as well as the government’s free education policy, which instructs all ward secondary schools throughout the country to provide education without charging fees or contributions from parents or students (Lameck et al. 2019).

Mwanza City has 57 secondary schools of which 30 are public and 27 are non-government. The city’s Strategic Plan 2016–2021 showed a total of more than 36,000 enrolled students: about 26,000 in government secondary schools and 10,000 in non-government schools. According to the plan, Mwanza had 1,470 teachers teaching in secondary schools, but faced shortages of both teachers and facilities – classrooms, laboratories, furniture, toilets, dormitories, administration blocks and teachers’ houses (URT 2016a).

Study purpose and methodology

While Tanzania’s education sector reforms under its free education policy came with new guidelines and directives for the delivery of secondary education that sought to improve standards and outcomes, including in teacher numbers, infrastructure and facilities, as well as student performance (URT 2016b), questions remain about what has been achieved. This study explores whether the projected improvements are being made.

The research was conducted from June 2021 to January 2022. It began with a content analysis of relevant documents such as policy documents from both central and local governments, guidelines for education planning and administration, weekly schedules and monthly reports from education officials. This provided a rough picture of the formal rules, guidelines and directives that influence agency culture and performance.

In order to gain more insight into formal rules and the agency culture, and the way they affect the role and discretion of teachers, a total of 72 interviews were then conducted with a mix of education department officers based at the city council (involved in coordinating education services), head teachers, and senior academic teachers with both teaching and school leadership roles. Also, there were ten focus group discussions, including seven teachers drawn from each of the public secondary schools in the city’s Nyamagana division. The questions for interviews and data recorded were structured under three main themes:

• The nature of teachers’ jobs as ‘street-level bureaucrats’, including their workload and the way they develop their teaching schedule and organise delivery of learning to students;

• The impact of the plans, guidelines and directives that they are required to follow in the delivery of education services, and ways they are applying new guidelines and directives;

• Their relationship with the municipal council and central government bureaucracy, and the way the NPM-inspired guidelines and directives affect their discretion in delivering education services.

The tables below summarise the interviews and focus group discussions.

| Level of organisation | No. of respondents | No. of interviews | Job titlesof respondents |

|---|---|---|---|

| Municipal level | 4 | 7 | Municipal executive officer, municipal education officer/coordinator |

| Kishiri Ward | 4 | 8 | Ward education officer |

| Igoma Ward | 4 | 7 | Ward education officer |

| Mahina Ward | 3 | 6 | Ward education officer |

| Mkuyuni Ward | 4 | 7 | Ward education officer |

| Nyegezi Ward | 4 | 5 | Ward education officer |

| Fumagira Secondary School | 3 | 6 | Head teacher, senior academic teacher |

| Igoma Secondary School | 3 | 6 | Head teacher, senior academic teacher |

| Mahina Secondary School | 3 | 6 | Head teacher, senior academic teacher |

| Nyakurunduma Secondary School | 4 | 7 | Head teacher, senior academic teacher |

| Nyabulogoya Secondary School | 4 | 7 | Head teacher, senior academic teacher |

| Total | 40 | 72 |

| Level of organisation | No. of focus groups | Job titles of participants | No. of participants |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fumagira Secondary School | 2 | Teacher | 14 |

| Igoma Secondary School | 2 | Teacher | 14 |

| Mahina Secondary School | 2 | Teacher | 14 |

| Nyakurunduma Secondary School | 2 | Teacher | 14 |

| Nyabulogoya Secondary School | 2 | Teacher | 14 |

| Total | 10 | 70 |

Findings

Mwanza City’s 2016 education plan identified a number of targets to be reached. These included construction of 400 classrooms, 802 students’ latrines, 1,385 teachers’ houses and 45 teachers’ latrines; an improvement in the Form 4 examination pass rate from 72% to 90%; raising the advanced level of secondary education pass rate from 92% to 100%; recruiting 221 science teachers; and sourcing 9,032 students’ chairs, 10,345 students’ tables, 882 teachers’ chairs and 950 teachers’ tables. The targets set were expected to be achieved through the local government’s own budget plus mobilisation of funds from other educational stakeholders such as parents and donors (URT 2016a).

In order to guide the process of implementing the plan to realise education performance targets, the national ministry issues guidelines on key issues which should be addressed in the scheme of teaching and the step-by-step preparation of class sessions, based on time available and subject matter (URT 2021).

To finance the implementation of the plan and projects, the city council received funds through intergovernmental transfers from central government for the education sector, in particular secondary education development. For example, in the financial year 2020/2021 the council received a total of 180 million Tanzanian shillings1 (TZS) for laboratory construction and TZS 112.5 million for construction of classrooms. Then in the year 2021/2021 the council received a total of TZS 1.96 billion for the construction of 103 classrooms (URT 2021).

However, interviews with the officials responsible for budgeting show that in neither year did the allocated financial resources reach the council on time; in fact theywere not received until the last two quarters. This delay obstructed the implementation of projects on time. Apart from that, the allocated funds were sufficient for only a few of the planned projects. As a result, the numbers of constructed classrooms and recruited teachers do not meet current demands, and shortages of furniture, latrines and teachers’ houses have remained unaddressed challenges.

Teachers acknowledged the government’s efforts so far to improve the education sector, but confirmed that:

Despite the government’s commitment in improving [the] education sector, the sector is still confronted with challenges, especially the fund to renovate the old infrastructure (In-depth interview, head teacher – 10 April 2022).

On the other hand, the study showed that the government’s policies have increased the quality of, and access to, secondary education services for students. This improvement is also associated with decentralisation of management of education institutions to local governments, which have empowered teachers and parents to fully participate in education services delivery:

Basically, there have been reforms in [the] education sector, especially in secondary education. These reforms include policy reforms [free education policy] which have resulted in the increase of students’ enrolment in secondary schools (In-depth interview, ward education officer – 27 May 2022).

The impact on teachers has been mixed. While they welcome increased enrolments, in line with the city’s vision, this did not come with enough classrooms and teachers complained about the number of students exceeding their capacity to service them. In a focus group discussion, one teacher commented that:

On the question of [the] free education policy, there have been a large number of students who are enrolled. This has led to a significant increase of students in secondary schools, while teaching and learning resources are insufficient. In a nutshell, I can say the number of students is large while we are understaffed. Therefore, it becomes very hard for a single teacher to attend to all students (Focus group discussion, teacher – 12 April 2022).

Others said:

These reforms have affected the way I work here. You know, the number of students is large here. This has been attributed to [the] free education policy. Therefore, under this circumstance, I find myself unable to attend every student. Although I wish I could attend all of them.

…we teachers try our level best to fulfil our duties, even though we are overwhelmed by the number of students… This has been attributed to [the] introduction of [the] free education policy (Focus group discussion with teachers – 26 May 2022).

Moreover, the teachers are required to follow the standardised calendar for teaching developed according to national-level guidelines. This suggests that teachers may not be able to teach as they wish, instead having to follow an annual calendar developed by central government for the purpose of quality control. One of the ward education officers confirmed that:

In 2022, the President’s Office for Regional Administration and Local Government introduced new guidelines, including a guideline for preparing the teaching calendar. Therefore, teachers must follow them when teaching and not do otherwise (In-depth interview, ward education officer – 14th April 2022).

In a focus group discussion, one of the teachers added that:

It’s true that there are guidelines [that] require teaching to be carried out as prescribed in the calendar. To me, these guidelines do not provide me with an opportunity to teach as I want based on the nature of my class [students] so that I can achieve learning outcomes on the given topic (Focus group discussion with teachers – 13 April 2022).

Another said:

On [the] presence of the teaching calendar for the whole country, I see it as a challenge that limits my discretion. Therefore, I find myself unable to apply my own teaching methods depending on the nature and needs of students in the classroom (Focus group discussion with teachers – 12 April 2022).

Furthermore, the teachers are now required to report for their duties every day at the school and every month at the council, and any diversion from their formal duties must be explained. In this way they must follow a strict procedure and guidelines in the process of performing their duties, and be very careful to make sure that they follow guidelines to avoid punishment or threats for non-compliance. In an interview, a ward education officer commented that:

In the education sector, these new reforms have come up with new rules and regulations. For instance, previously teachers were required to prepare a lesson plan for teaching activities on a daily basis. But currently they have to prepare a lesson plan plus filling a form that shows number of lessons taught, exercises and tests administered to students on a given subject per month. And this form is submitted to the education department at a given council [local government]. (In-depth interview, ward education officer – 14 April 2022).

Teachers made similar comments in focus group discussions, while a ward education officer added that:

Schools are required to follow all guidelines issued including education, teaching calendars and guidelines for setting exams issued by the National Examination Council of Tanzania (In-depth interview, ward education officer – 13 April 2022).

From another perspective, local communities and especially parents need secondary students to receive quality education that will improve their lives. Students are expected to perform well, especially in their end-of-term examination and national examinations, but this goal may not be realised if teachers are unable to exercise sufficient discretion in how to do their job. One teacher shared his views in a focus group as follows:

There are many expectations. My students expect effective teaching from me, to be knowledgeable and perform well in their final exams so that they can realise their dream for a better life. Besides, the community wants teachers to set a good example from which students can learn, be inspired and motivated and so forth (Focus group discussion, teacher – 13 April 2022).

Conclusion

Tanzania’s NPM reforms in education were introduced with good intentions, but their implementation has come with serious problems of inadequate infrastructure, including numbers of teachers, to cope with increased enrolments of students as a result of the free education policy. Also, the reforms have come with additional guidelines and directives which education officers and teachers must follow, and their discretion has been considerably reduced as a result. Having to follow the standardised calendar for teaching limits their freedom to decide about teaching pedagogy, the teaching environment and how to accommodate the differing needs of students. National standards are not necessarily consistent with local realities, especially when the education sector is engulfed by a scarcity of teaching and learning resources. The government needs to engage education stakeholders, particularly teachers, by enabling them to share their insights about the realities of teaching and learning settings at ‘street level’. Additionally, the government in collaboration with development partners must do more to maximise resources for education, while giving teachers the freedom to adjust the use of available resources according to the needs of students and local realities. This will also increase the accountability of education services to their clients: students, parents and communities.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship or publication of this article.

References

Ackroyd, S., Kirkpatrick, I. and Walker, R.M. (2007) Public Management reform in the UK and its consequences for professional organization: a comparative analysis. Public Administration, 85 (1), 9–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2007.00631.x

Bach, S., Kessler, I. and Heron (2007) The consequences of assistant roles in the public services: degradation or empowerment. Human Relations, 60 (9), 1267–1292. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726707082848

Biswas, V. (2020) New Public Management: meaning, 10 principles, and features. Political Science, [Blog]. Available at: https://schoolofpoliticalscience.com/new-public-management/

Brodkin, E.Z. (2011) Policy work: street-level organizations under new managerialism. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 21 (2), 253–277. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muq093

Durose, C. (2009) Front-line workers and ‘local knowledge’: neighbourhood stories in contemporary UK local governance. Public Administration, 87 (1), 35–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2008.01737.x

Economic Commission for Africa. (2004) Public sector management reform in Africa. Addis Ababa: United Nations Economic Commission for Africa.

Evans, T. and Harris, J. (2004) Street level bureaucracy, social work and the (exaggerated) death of discretion. The British Journal of Social Work, 34 (6), 871–895. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bch106

Gupta, P., Thakur, M. and Chakrabarti, B. (2022) Betwixt agency and accountability: re-visioning street-level bureaucrats. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, (26), 94–113. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi26.8173

Hood, C. and Jackson, M. (1991) Administrative argument. Aldershot. Dartmouth: Cambridge University.

Hughes, O.E. (2003) Public management and administration: an introduction. 3rd ed. Australia: Palgrave Macmillan.

Lameck, W. and Hulst, R. (2019) Explaining coping strategies of agricultural extension officers in Tanzania: the role of the wider institutional context. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 86 (4), 749–764. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852318824398

Lameck, W.U., Kinemo, S., Mwakasangula, E., Masue, O., Lyatonga, I. and Anasel, M. (2019) Relationship between national and local government in Tanzania. Report prepared for Tanzania Urbanization laboratory. Dar es salaam: TU Lab.

Liljegren, A. (2012) Pragmatic profession: micro-level discourse in social work. European Journal of Social Work, 15 (3), 295–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2010.543888

Lipsky, M. (2022) A note on pursuing work on street‐level bureaucracy in developing and transitional countries. Public Administration and Development, 42 (1), 11–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.1969

Mukandala, R.S. and Shellukindo, W. (1994) Moving beyond the one-party state. In: Picard, L.A. and Garrity, M. (eds.) Policy reform for sustainable development in Africa, (pp. 67–80). Boulder, USA: Lynne Rienner. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781685858957-008

Paulsen, N. (2018) New public management, innovation and the non-profit domain: new forms of organizing and professional identity. In: Veenswijick, M. (ed.) Organizing innovation: new approaches to cultural change and intervention in public sector organizations, (pp. 15–28). Amsterdam: IOS Press.

Riccucci, N. (2005) How management matters: street-level bureaucrats and welfare reform. Washington: George Town University Press.

Sandfort, J. (2000) Moving beyond discretion and outcomes. examining public management from the front lines of the welfare system. Journal of Public Administration Research Theory, 10 (4), 729–756. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a024289

Tummers, L., Bekkers, V., Vink, E. and Musheno, M. (2013) Handling stress during policy implementation: developing a classification of ‘coping’ by frontline workers based on a systematic overview. Paper presented at the 2013 IRSPM Conference. 10–12 April, Prague.

United Republic of Tanzania (URT) (2012) The long-term perspective plan 2011/2012–2025/26. Dar es Salaam: President’s Office Planning Commission.

United Republic of Tanzania (URT) (2013) Reforming Tanzania’s public sector: an assessment and future direction. Dar es Salaam: President’s Office, State House.

United Republic of Tanzania (URT) (2014) Education and training policy. Dar es Salaam: Ministry of Education and Culture.

United Republic of Tanzania (URT) (2016a) Mwanza City Council strategic plan 2016–2021. Dar es Salaam: President’s Office Regional Administration and Local Government.

United Republic of Tanzania (URT) (2016b) Tanzania five years development plan 2016/2017. Dar es Salaam: Ministry of Finance and Planning.

United Republic of Tanzania (URT) (2021) President’s office regional administration and local government budget 2021–2022 Year. Dar es Salaam: The Office.

United Republic of Tanzania (URT) (n.d.) Tanzania Development Vision 2025. Dar es Salaam: President’s Office Planning Commission.

1 TZS 1,000,000 equals approximately USD 400.