Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance

Issue 28

September 2023

RESEARCH AND EVALUATION (PEER REVIEWED)

Decentralisation and Political Empowerment of Citizens in Karamoja, Uganda

Jimmy Francis Obonyo

Faculty of Management Sciences, Department of Public Administration and Management, Lira University, PO Box 1035, Lira, Uganda, unclebonzu@gmail.com

William Muhumuza

School of Social Science, Makerere University, PO Box 7062, Kampala, Uganda, wmuhumuza2@gmail.com

Corresponding author: Jimmy Francis Obonyo, Faculty of Management Sciences, Department of Public Administration and Management, Lira University, PO Box 1035, Lira, Uganda, unclebonzu@gmail.com

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi28.8769

Article History: Received 28/10/2022; Accepted 06/08/2023; Published 25/09/2023

Citation: Obonyo, J. F, Muhumuza, W. 2023. Decentralisation and Political Empowerment of Citizens in Karamoja, Uganda. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, 28, 42–60. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi28.8769

© 2023 by the author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercial, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Abstract

For centuries, centralisation was the dominant model of governance in most parts of the developing world. However, since the mid-1980s many countries in Africa have adopted decentralisation owing to the failure of centralisation to deliver public goods to citizens. In 1992, Uganda adopted decentralisation policy reforms to give ordinary citizens more control over their own administration and development agenda. This article reports case study research conducted in Karamoja, Uganda to establish the extent to which decentralisation reforms have indeed empowered local people. Research findings revealed mixed results. Although decentralisation resulted in the creation of the local government system, which in principle offers representational governance for different interest groups in local communities, ordinary citizens have fallen short of being politically empowered. State–society power relations have remained unaltered in favour of local elites. The authors contend that for political empowerment of citizens to be achieved, there is a need to devolve a considerable amount of autonomy to local governments and review the law to make local elites subordinate to citizen representatives.

Keywords

Decentralisation; Political Empowerment; Accountability; Ordinary Citizens; Karamoja

Introduction

This research sought to establish whether or not decentralisation policy reforms have led to the political empowerment of citizens in Karamoja, a historically isolated and marginalised sub-region of Uganda. The end of the Cold War led to a wave of policy reform initiatives in Africa. Key among these was decentralisation of power to lower levels of government (Ndegwa and Levy 2003, p. 3). The intention was to reverse the negative effects of centralised governance which had stifled development. Advocates of decentralisation believe that it has diverse developmental benefits that include political empowerment of citizens, improvement of local accountability, and ease of access to information; and that it thereby stimulates development, especially in disadvantaged communities (Chambers 1983; Manor 1999, pp. 37–38; Sakyi 2013, p. 56). These supportive arguments notwithstanding, some scholars remain sceptical about the real impact of decentralisation on citizens at grassroots level. They cite several risks: that decentralisation may promote local elite interests rather than those of the ordinary citizens; it may reinforce gender discrimination; and it may undermine accountability and, consequently, promote corruption at the local level (Brosio 2000). However, in spite of these concerns, the assumed benefits of decentralisation are still considered to outweigh the shortcomings and it continues to be widely embraced as a better governance system. Indeed, the rationale of Uganda’s decentralisation programme included addressing regional development disparities and thus ethnic competition for power at the centre.

After the unsatisfactory experience of the post-independence centralised model of governance, which was characterised by dictatorship, state collapse, and failure to promote development or reduce poverty, in 1992 Uganda’s new National Resistance Movement (NRM) government pursued decentralisation reforms, claiming that these would democratically empower the people to take control of their development and governance agenda (Muhumuza 2008). The historical context was complex. Earlier decentralisation initiatives adopted towards the end of British colonialism in the mid-1950s and which were inherited by the post-independence government lasted until 1966 (Hicks 1961; Burke 1964; Muhumuza 2008, p. 61). In 1967, a new constitution was promulgated which enabled the national government to centralise power, greatly limiting the authority of local governments in all aspects. Local administrators became political appointees. Over time, in the absence of direct local accountability, services deteriorated, leading ultimately to the NRM government’s decentralisation policy reforms. Those reforms included returning administrative, financial and political autonomy to local authorities. This was expected to give discretion to local officials in decision-making, promote citizen participation and local ownership of development initiatives, and enhance fiscal responsibility and accountability; and consequently improve service delivery (Government of Uganda [GoU] 1993a, p. 1). All these advances were expected to translate into political empowerment of citizens – awareness of their political rights, access to information about public finances and programmes being implemented, participation in decision- making, and capacity to demand accountability from their leaders.

Implementation of the decentralisation reforms in the early years from 1993 to 1997 was heralded as exemplary (Francis and James 2003, p. 325). This was evidenced by a sound policy and legislative framework that gave local authorities autonomy to hire and fire their staff, collect taxes and receive sizeable grants from the central government. Some scholars have argued that those gains have since been eroded to the extent that decentralisation is now riddled with policy failures and reversals (Smoke et al. 2014). However, the NRM government – led by President Museveni for an unbroken 37 years – claims that the reforms are on track and performing well. It is in the context of this controversy that this article analyses whether or not decentralisation policy reforms have politically empowered the ordinary citizens of Karamoja.

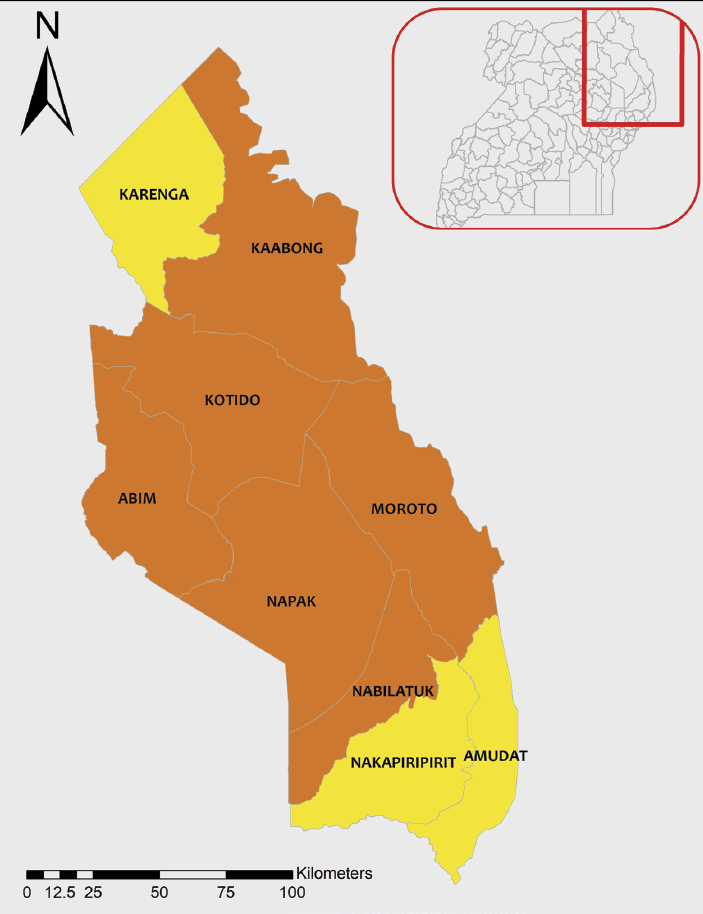

Figure 1. Map of Karamoja Region showing the study districts of Moroto and Kotido

Source: Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (2021, p. 9).

The Karamoja sub-region in north-eastern Uganda is composed of nine local government districts and is home to numerous ethnic sub-groups. It is characterised by a harsh semi-arid environment with an agro-pastoral economy. Development indicators are the worst in the country. For instance, the literacy rates for persons aged 18 years and above in the Kotido and Moroto districts (where this study was carried out) stand at 10.2% and 22.2% respectively, compared to the national average of 74% reported by the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS 2017). Also, in 2019/20, 65.7% of the Karamoja population lived in absolute poverty, which was the highest proportion in Uganda and nearly three times the national average of 23.5% (UBOS 2020).

Karamoja also has a history of isolation and marginalisation by governments both during colonialism and after independence (Mamdani 1982, p. 66). Colonialism not only used repression to govern the sub-region but also closed it off to the outside world. One needed a permit to visit it. Karamoja was referred to as a ‘special area’ or a ‘human zoo’ between 1911 and 1950 (Owiny 2006, p. 15). As well, the colonialists implemented hostile policies, such as destocking and gazetting of land for game parks (Mamdani 1982). After independence, successive governments continued to marginalise the sub-region. For instance Milton Obote, the country’s first prime minister, is reported to have said that “Uganda cannot wait for Karamoja to develop” (Närman 2003, p. 130), and later Idi Amin’s reign took a militaristic approach to governing Karamoja (Nsibambi 2014).

A change of attitude came with the NRM’s ascent to power in 1986. Not only did it pledge to address Karamoja’s problems in its Ten-Point Programme (GoU 1993b), but it also used the decentralisation policy initiative as a driver for development in Karamoja. As noted above, this was intended to empower people and to advance development and governance in order to better their standard of living. The idea was that citizens would engage in decision-making so as to identify their local problems, set their priorities, plan and budget, and demand results from political and administrative officials.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows: conceptual and theoretical perspectives; research methods; findings and discussion; and conclusion and policy recommendations.

Conceptual and theoretical perspectives

Citizens’ political empowerment is defined in various ways by different scholars. Some conceive it to be a process of transferring power to those who lack it (Budryte 2014). Others define it as a three- dimensional process of building people’s capacity so they can have more freedom of choice, agency and participation in society decision-making (Sundström et al. 2015). This article adopts the second definition. Choice refers to people’s freedom to identify their needs and interests; participation denotes involvement of people in public decision-making (Kabeer 1999, pp. 435–464); and agency is about capacity to shape political agendas or to publicly voice people’s policy preferences (Lukes 1974; Young 1993; Welzel 2013). Accordingly, being disempowered is being deprived of choice and the opportunity to decide. According to Sundström et al. (2015), political engagement is a key component of empowerment.

Political empowerment is anchored in power relations theory. The argument is that differential power exists between different levels of government, and the centre possesses more power than sub-national governments. Power at the centre is claimed to be controlled and exercised by the ruling elites who pursue vested interests (Kimengsi and Gwan 2017). Decentralisation is supposed to initiate a process through which power and resources are shared or redistributed from the centre to sub-national governments – although this paper argues that in Uganda’s case this is more theory than practice.

While power relations theory maintains that redistribution of power and resources will empower citizens and subsequently improve their livelihoods, and that the reverse is also true (Francis and James 2003, p. 326; Reyes-Garcia et al. 2010, p. 230), power-sharing through decentralisation between the centre and the locality is contingent on political circumstances (Manor 1999, p. 4; Eaton et al. 2011). So, when the circumstances are favourable to the ruling elite they may decentralise power, and when they deem that the political circumstances have changed they may recentralise it. This has been Uganda’s reality. A critical review of Uganda’s decentralisation reforms shows that from the inception period of 1992 up to 2006, decentralisation received huge political support from the ruling elite, demonstrated by considerable devolution of power and resources to districts (local governments), which accounted for about 25% of the national budget by 2006 (Kaaya 2016). However, from 2006 onwards the changing political circumstances – notably the NRM’s decision to allow multi-party politics – subverted political commitment and support from the existing elite as it sought to maintain its position. Consequently, the policy suffered reversals in the form of significant recentralisation of powers and resources (Muhumuza 2013, pp. 275–280; Smoke et al. 2014).

To establish whether Uganda’s decentralisation has empowered the people of Karamoja, this research applied the three concepts of choice, agency and participation. Using these as indicators for assessing political empowerment, it explored citizens’ participation in public decision-making, awareness of their rights and duties, access to information in the possession of government, control of public financial resources, and demand for accountability from public officials.

Research methods

The interpretivist paradigm served as the foundation for this study’s research technique. This paradigm emphasises the need to put analysis in context and the necessity of understanding events through the meanings that people attribute to them (Deetz 1996; Reeves and Hedberg 2003, p. 3). It seeks a deeper understanding of the phenomena under investigation based on the subjective experiences of individual participants (Hitchcock and Hughes 1989). Accordingly, detailed information was gathered from the perspectives of research participants via inductive qualitative research methods such as observations, interviews and focus group discussions (FGDs).

The study began with a field reconnaissance visit in April 2017 in Karamoja. The actual data collection occurred from April to August 2018. Gaps were filled during 2019 and 2020. Two sampling techniques were used to engage study participants: purposive sampling for those deemed to be knowledgeable or have expertise or rich experience based on positions held in the local authority establishment or community; and convenience sampling for ordinary citizens, given that the study location was in a ‘hard-to-reach’ and sparsely populated region, and local communities were not easily mobilised to participate due to their historic mistrust of outsiders.

Triangulation of key informant interviews (KIIs), FGDs and documentary review of published and unpublished materials were all used to gather data. In total, 17 key informants were interviewed from the two district local governments of Moroto and Kotido. These local governments were selected because they were within the first set of districts piloted for implementation of Uganda’s decentralisation policy reforms. The KIIs were supplemented by nine FGDs, four in Moroto and five in Kotido. Each FGD comprised eight participants drawn from homogeneous groups such as councils of elders, women, youth, local councillors, council executives and parish development committees (PDCs) so as to allow free exchange of ideas, views and opinions among study participants. The qualitative data collected from KIIs and FGDs was analysed using content analysis. The generative and interpretive phases involved reading through the transcripts iteratively so as to gain insights and understand the logic of the data. The representing and theorising phases sorted data into themes and sub-themes which were reported verbatim.

Findings and discussion

Participation in local decision-making processes

Citizen participation is a key ingredient of political empowerment (Manor 1999, pp. 7–38). It denotes active engagement in decision-making, and it is widely believed that promoting citizen participation is an important way of empowering the marginalised and the poor, improving government responsiveness to their needs and enhancing accountability (Combaz and Mcloughlin 2014). Citizen participation in development processes takes various forms, ranging from participating in meetings, the provision of resources, problem analysis, project initiation, identifying priorities, planning, and designing implementation and management arrangements (Marijani 2017, p. 637).

Uganda’s laws and policy on decentralisation provide for citizen involvement and inclusion in decision-making in order to encourage popular participation. According to Article 38(1) of the 1995 Constitution, every Ugandan citizen has the right to engage in governmental matters, either directly or indirectly. The policy mandates the citizens to give approval to local government plans and budgets through their elected councillors. (Article 35(1) of the Local Governments Act 1997 specifies that the district council is the district’s planning authority (Cap. 243), while Section 17 stipulates that a local government council shall develop, approve and carry out budgets and plans in accordance with Section 77 of the same Act.) However, despite a favourable legal and policy environment, local actions have tended to deviate from the legal provisions. Both the elected members and administrative staff of local governments, whom we refer to as ‘local elites’, manipulate the system to serve their vested interests rather than enabling ordinary citizens to set their own development priorities or even hold their leaders accountable (Muhumuza 2008, p. 426).

Under the 1997 Local Governments Act, decentralised participatory structures were established at the village, parish, sub-county and district levels (GoU 1997). However, in Karamoja citizen involvement in local government decision-making on matters of budgeting and planning for development remains stifled. Views from FGD and KII participants in Moroto and Kotido districts confirmed limited participation by ordinary citizens. This was a typical comment:

Secrecy in expenditures and accountability by sub-county government officials was the main reason for their hesitation to engage us in participatory planning and budget processes. They wanted us to remain uninformed about such activities so that we do not follow up and question them about expenditure and accountability (FGD, youth, Katikekile sub-county, Moroto, August 2018).

The same concern was echoed in a women’s FGD, where participants revealed that they had not been involved in planning, budgeting or monitoring of development projects:

It is a few individuals that are friends or relatives to the local council leaders who get involved and could possibly be aware of all these activities of government (FGD, women, Katikekile sub-county, Moroto, August 2018).

Interviews with district officials confirmed the low levels of citizen participation, but attributed these to financial limitations. They further alleged that public participation was thwarted by the fact that ordinary citizens demanded support in the form of a transport refund, drinks and lunch, a culture that was created and nurtured by NGOs for many years. One official observed that, to make community meetings successful:

…one needed to move with not only snacks but also some transport refund for participants of between USh5,000 to USh10,000 for each participant, which the local governments cannot afford because of budgetary constraints (KII, district planner, Kotido district headquarters, May 2018).

Accordingly, interviewee maintained that, owing to resource constraints, sub-county local government officials resolved to invite only members of parish development committees (PDCs), rather than organising village planning committees (VPCs) to represent all citizens. Yet this practice contravenes the law and excludes citizens at the grassroots from the decision-making process. Interviewees indicated that, in the end, it was the PDCs that did the planning on behalf of the people at the grassroots, and their meetings were dominated by officials (KII, district planner, Kotido, 30 May 2018). However, the allegation that ordinary citizens would not attend meetings without financial or in-kind support was disputed. In an FGD with council leaders and PDCs from Kotido district, participants reported that:

The sub-county chiefs do not call the LCIs [local councils] and PDCs to come and plan. They always plan on their own and then put everything on the noticeboard. They forge minutes of planning because they want to share allowances between themselves that were meant for people who would have come for meetings (FGD, Nakapelimoru, Kotido, June 2018).

The citizens feigned ignorance of what was happening with social service delivery in the whole sub-county. Our sample review of the minutes of Nakapelimoru sub-county technical planning committee meetings conducted on 25 March 2016 and 20 July 2017 found that the wording and content of these minutes were the same, which supports the claims of the VPCs and PDCs of Kotido that the officials forged minutes.

The limited involvement of citizens in decision-making was sometimes attributed to the top-down approaches used by the central government. In some cases, development projects initiated by the centre were imposed on the local people without their input. In such circumstances, a project formula was determined by the central government authorities. For instance, the restocking programme in Karamoja was not chosen by the local people but by the Office of the Prime Minister (OPM). As a result, most of the cattle breeds that were delivered died because the intended beneficiaries were not involved in making the right choices. The breeds delivered were exotic ones that did not suit the semi-arid climatic conditions of Karamoja.

A similar case was the off-season supply of cassava cuttings for planting. It was reported that the OPM distributed cassava cuttings during the dry season, and so they dried up. Again, the project concept was formulated without the participation and input of the beneficiary communities. The local governments were implementing centrally-determined development priority programmes because of their dependence on funding from the centre. This information was corroborated by the programme coordinator of the NGO Caritas in Kotido district, who commented that planning and budgeting were still top-down in nature. He argued that civil servants at the district level still determine inputs for inclusion in the sub-county and district development plans. Central government still possesses a lot of power over local government decisions and activities since it determines the indicative planning figures (IPFs) for budget allocations and gives guidance on planning for all local governments, a practice which restricts citizens’ role in identifying preferred plans based on local priority needs. When the central government sets the IPFs, it also issues a checklist of government priority areas for investment, which include health, education, roads, water and community development. This means that all central government grants to local governments must be in line with the centrally determined priority programmes: citizens’ priorities that happen to be different from those of the centre are not considered.

These findings concur with the argument by Smoke et al. (2014, p. 233) that local government functions have been usurped by central agencies to the extent that planning in local governments has been reduced to rubber-stamping the wishes of the centre. Local governments’ budgeting has taken on a central government character with no room or flexibility left for ordinary citizens to address their particular needs (Azfar et al. 2006, p. 10). Related studies on decentralisation reforms in Uganda by Francis and James (2003, p. 325) also suggested that decentralisation had done little to improve local participation by citizens. Despite the laws, structures and procedures created to politically empower ordinary people, citizens’ participation in decision-making on matters that affect their lives has remained low or limited compared to what advocates of the decentralisation policy had anticipated.

Citizens’ awareness of their rights and duties

One of the fundamental traits of a politically empowered community is citizens who are aware of their civic and political rights and obligations. Article 38 of Uganda’s constitution provides citizens with a right to participate in public decision-making and to elect their leaders (GoU 1995). Objective 29 of the constitution makes it clear that the exercise and enjoyment of rights and freedoms is inseparable from the performance of duties and obligations, and states that it is the duty of every citizen, among others, to: engage in gainful work for the good of that citizen, their family and the common good and to contribute to national development; to contribute to the wellbeing of the community where that citizen lives; to foster national unity and live in harmony with others; and to promote democracy and the rule of law (GoU 1995).

Notwithstanding the stipulation of citizen rights and duties in the constitution, the research findings of this study established that only a few people (mainly the elites) were aware of their rights and duties as citizens. For example, one of the FGDs for women revealed that ordinary citizens were not aware of their civil rights. This gap was echoed by one of the district officials in Kotido district who also noted that local people were not informed of their rights and roles as citizens, except for the elites. He explained that ordinary citizens were more preoccupied with matters concerning livestock as their major source of livelihood than with matters of civil rights and politics. It was also evident that some of the elected local leaders similarly lacked a proper grasp of their roles and responsibilities (KII, Kotido district official, May 2018).

In part, citizens’ lack of knowledge of their rights and responsibilities was also due to an absence of civic education. Many were not aware of the provisions of the constitution and the decentralisation policy for their rights and civil roles. Moreover, these two important documents were never translated from English into local languages so that the local people can read and understand them. The mandate to give Ugandans civic education lies with the Uganda Human Rights Commission (UHRC), but in its 2018 annual report the commission cited the lack of a national civic education policy and insufficient funds as major challenges (UHRC 2018, p. 246).

Access to government information

Another key strategy for empowering citizens politically is access to information. People should have the right to request and receive information kept by the government (Burgman et al. 2007). It is claimed that precise, clear and pertinent information can empower individuals by educating them about crucial life concerns like their basic rights and entitlements, the accessibility of essential services, and employment prospects with the government (Leach and Scoones 2007). The Government of Uganda, in a bid to enhance access to information, has put in place a number of enabling legal instruments. For instance, Article 41 of the constitution, the Access to Information Act 2005, the Access to Information Regulations 2011, and the Government Communication Strategy 2005 all guarantee the public’s right to access information and records held by the state or any public body, unless disclosing the information would jeopardise the state’s security and sovereignty or infringe upon another person’s right to privacy (GoU 2005, 2011).

The government has not only invested in information and communication technology (ICT) infrastructure for local governments, but also emphasised the need to display information for public consumption using the internet, noticeboards and posters where citizens can easily access information about government programmes. Despite the existence of all these avenues in both districts, FGD interviews suggested that only a few people had access to government-held information. It was mostly the supporters of local government political leaders who had access to information about local government programmes and funding. Even when community meetings were organised, only a few people would be invited to attend and therefore receive information (FGD, youth, Nakapelimoru sub-county, June 2018).

The situation was even worse regarding access to financial information, especially details of remitted central government grants and their utilisation. FGD interview sessions with ordinary citizens revealed that the leaders did not share financial information with them. Information on the amount of public funds received and how they were used was not disclosed but was kept confidential from the public by the sub-county leaders, perhaps for their own interests. It was further reported that when an ordinary citizen seeks information from local leaders, he/she is harassed because they are perceived to be intrusive (FGD, women, Katikekile sub-county, August 2018).

In an interview with the Kotido district information officer and the programme coordinator of Caritas Kotido in June 2018, they attributed the lack of access to information by citizens to the high rate of illiteracy in the community. Although it is true that illiteracy rates are high in Karamoja, as confirmed by the UBOS report, alternative information channels such as barazas (community dialogues) and radio programmes that used local languages would not require ordinary citizens to be literate. According to the study by Francis and James (2003, p. 325), the main problem with local governments in Uganda is the lack of a culture of openness and public access to information.

Access to and control of public financial resources

A number of scholars have argued that the main prerequisite for the empowerment of ordinary citizens is some degree of control over resources (Manor 1999, p. 37; Sundström et al. 2015, p. 5). Bearing in mind this idea, the Ugandan government granted authority to citizens to control local government financial resources through their elected representatives (Article 77 (1) of the Local Governments Act 1997 [as modified]). Local authorities have the mandate and responsibility to develop, adopt and carry out their plans and budgets, provided that they are balanced (revenue equals expenditure). This provision has, however, remained theory rather than practice. Neither the ordinary citizens nor their representatives have full authority to decide on how funds are to be utilised, since local authorities are dependent on central government transfers. As noted earlier, the fact that the priorities on which these funds are to be spent are predetermined means that citizens are left with no leverage. In an interview, the vice chairperson of Kotido district stated that although the decentralisation policy provided elected leaders with powers to control resources on behalf of the people, grants from the central government come with conditions that must be accepted (vice chairperson, Kotido district, May 2018). Importantly, 95% of the Kotido district budget came from the centre while development partners and locally generated revenue contributed only 3% and 2% respectively (Kotido District Budget for FY 2018/2019). The Chief Administrative Officer (CAO) of Kotido reiterated that while the district had the role of identifying local needs, in line with the principle of decentralisation, in practice:

…we are not very free with our financial resources. Our financial resources come already allocated by the central government to different priority areas. This gives very little flexibility to us and not even the citizens. The citizens will just present their challenges before us and then we work with them to prioritise against the pre-determined amount by the central government (KII, CAO, Kotido district, May 2018).

Similarly, in the case of Moroto district, more than 80% of the budget funds came from the centre (District Budget Speech for FY 2018/2019). Local revenue constituted only 4%, and development partner support stood at 16%.

Bainomugisha et al. (2020) confirm that the bulk of central funding comprises conditional grants, and that so-called unconditional grants are largely to be spent on salaries. Also, district officials revealed that some central government ministries, such as those responsible for water, works, agriculture and health, retained large proportions of funding intended for distribution to local governments. This matched findings by Ggoobi and Lukwago (2019), who noted that despite the financial difficulties local governments were experiencing, in FY 2018/19 central government ministries, departments and agencies retained up to one trillion Ugandan shillings that had been allocated for local government.

Studies conducted elsewhere in Africa have made similar findings. Despite having implemented significant decentralisation reforms, African states still display central government dominance in areas like planning and capital investment, budgeting and fiscal management, personnel systems and management, and finance and revenue. Evidence shows that the majority of them have resisted devolving power and management of resources to sub-national organisations in order to promote efficient local decision-making (Lambright 2011, pp. 28–31; Wunsch 2014, p. 2).

Political representation in decision-making

Effective citizen participation and representation in political decision-making is a central requirement for empowerment (Sundström et al. 2015; Manor 1999, p. 37). This means making citizens’ voices, opinions and viewpoints ‘present’ in the formulation of public policy (Dovi 2006). Political representation happens when actors in the political sphere talk, symbolise and act on behalf of others. A key factor is the frequency of interaction between political leaders and the general public with the aim of obtaining the latter’s views, ideas and perspectives for inclusion in public policy-making.

Although Uganda’s decentralisation reforms have been praised for building local council systems within which people can elect their leaders right from the village to the district level, on the assumption that elected leaders serve the best interests of the electorate, this study found that political representation fell short of that goal. Research findings established that political representation in the two districts under study did not necessarily advance citizens’ interests. There were reports of limited interface between councillors and the electorate apart from elections. Only during election seasons did citizen involvement with elected officials increase. Interviews with councillors attributed the reduced engagement with the electorate to the enormous demands they were making. During a FGD session in Kotido district, the traditional chiefs reported that:

Representation here is not effective. We have a problem with elected leaders because they do not organise public meetings to consult us and give information (FGD, council of elders, Panyangara sub-county, Kotido district, June 2018).

This accusation was corroborated by FGDs with minority groups (women, disabled people and youth) in both study districts. They reported that the moment the political leaders are elected:

They do not come back to the electorate to hold consultative meetings and collect the views of the electorate. They instead represent their own views. They are not concerned about other people’s problems. Even when they are telephoned, they do not call back (multiple FGDs, Kotido district, July 2018).

Although affirmative action for women, young people, people with disabilities, and older people is widely regarded as essential to achieve an inclusive society, this study found that representation of special interest groups remained symbolic rather than translating into actual political empowerment as intended by the decentralisation policy. For instance, interviews with participants in Kotido district revealed that some councillors from various sub-counties had settled in town and forgotten about the people who voted for them in their manyattas (villages). Consequently, the village electorates were not informed about the decisions of the sub-county councils and their views were not represented. It was also observed that although the Local Governments Act 1997 provides grounds for the removal of a councillor from office that inter alia include non-performance or lack of effective representation, no councillor has ever been recalled by the electorate. This was blamed on citizens’ lack of awareness of local government law. In defence of their inaction, the councillors interviewed cited lack of funds for facilitating meetings with the electorate as the main cause. However, this is questionable: community meetings have been held traditionally under a tree or in an open space. Perhaps the issue was much more about whether councillors were given allowances to visit their constituents, since being a councillor was perceived as getting a job in government. In any case, political representation remained ineffective in bringing the voices of ordinary citizens into the decision-making process and decentralisation has yet to translate into political empowerment of ordinary citizens.

In addition, there were continuing cultural barriers that marginalised some groups. Karamojong society still has strong patriarchal structures that favour men, and women were considered inferior. These contextual inequalities in power were found to impede women’s participation and effective political representation in decision-making in local councils. Some men continue to oppose women running for office, and some women still exhibit a negative mindset and don’t think other women can hold leadership positions (Chairperson, Moroto district, August 2018). Also, whereas constitutionally women are free to contest any political leadership position in the country, some women are still unwilling to run in seats against men because they fear they will be intimidated or will lose, and thus compete only for reserved affirmative action seats (KII, deputy Resident District Commissioner), Moroto district, July 2018).

Therefore, despite the symbolic increase in opportunities for political participation as a result of decentralisation reforms in Uganda, political empowerment continues to be elusive and a distant goal for many ordinary citizens, notably marginalised groups like women, the youth, older persons and people with disabilities. Crook and Manor (1998) concur that the symbolic increase in participation in general elections and local councils as a result of decentralisation has not had the expected outcomes. The primary cause appears to be the local elite and executives seizing control of local governments and effectively remaining cut off from the electorate while in office (Kakumba 2010, p. 184).

Accountability of elected leaders and technocrats

Accountability is characterised by answerability and enforceability. Therefore, public officials (elected and appointed) must explain and justify their behaviour and actions to the members of the public, who pay for and consume the public goods they manage. Accountability and empowerment are closely inter-related: the agendas for both concern how citizens might acquire the tools, resources and capacities to demand accountability from those in positions of authority. This requires not only social and political empowerment, which forms the basis of transformed relations with the state, but also economic empowerment, which enhances people’s ability to engage with power holders (Combaz and Mcloughlin 2014). The extent to which citizens are able to hold elected representatives and bureaucrats accountable is a fundamental measure of the political empowerment of the population (Reyes-Garcia et al. 2010, p. 230).

The Constitution of 1995 established numerous downward and upward avenues for local governments in Uganda to be held accountable to citizens directly or indirectly. Article 17(i) of the constitution gives authority to citizens to demand accountability from both central and local governments. They can file complaints about public officials’ misbehaviour and participate as witnesses in legal proceedings involving corruption. The District Public Accounts Committee (DPAC) and the district’s Internal Audit Department, which each district is mandated by law to establish, are additional instruments to enforce accountability of local officials. These institutional structures are charged with ensuring the proper use of funds. The Local Governments Act 1997 also includes processes for recalling local council members. Part II of the Third Schedule of the Act provides that a councillor can be recalled for neglect of duty or for actions that are not in line with the position of district councillor if a third of the electorate signs a petition and presents it to the Electoral Commission.

In addition, the central government releases information to the press on fiscal transfers to local authorities on a quarterly basis so that citizens can be made aware of the resources that have been received for service delivery. Districts and sub-counties are required to post financial reports on public noticeboards regarding the funds received and how they have been utilised. Councillors have an obligation to keep an eye on service delivery and enforce accountability, and the minutes of council meetings are by law to be open to public access. As well, decentralisation reforms envisage citizen-led monitoring committees and other processes at lower tiers of local government to provide a grassroots voice in service delivery and subsequently subject power holders to scrutiny and answerability (Smoke et al. 2014, p. 235).

However, while these mechanisms for enforcing accountability have been established, the study found that ordinary citizens did not (or could not) effectively take advantage of opportunities to demand accountability from their elected representatives and bureaucrats in local governments. This was said to be caused in part by the fear of authority. Moreover, participants in a FGD for youth reported that information about public funds was withheld by officials:

Leaders ask for reasons why citizens require accountabilities and take them to be ignorant so that they can be easily exploited. Citizens who demand for accountability can be side-lined or denied opportunities to benefit from government programmes. For example, if an NGO comes looking for school dropouts to be supported, the leader can leave out your child if you ever demanded for accountability from him or her. This drives people away from demanding for accountability (FGD, youth, Katikekile, Moroto district, August 2018).

These views were echoed by the women’s FGD. It was reported that in 2018 there was a programme for seed distribution to farmers under the National Agricultural Advisory Services, but only a few targeted groups benefited and many people were left out. Such acts by local government leaders could have made local people demand accountability but there was fear of revenge: holding leaders accountable on an individual basis prompted finger-pointing and could prevent people from benefiting from government programmes in future (FGD, women, Rupa sub-county, Moroto district, August 2018).

In 2015 the Ugandan cabinet approved the use of barazas (community dialogues) to enable citizens to hold those in authority accountable. All districts and sub-counties are required to hold annual barazas under the direction of RDCs to inform the public about what has been planned, implemented, and is still to be implemented, as well as to provide an opportunity for residents to ask questions. The study found, however, that the barazas were not a reliable mechanism because they were not regularly organised owing to insufficient resources:

We have budget constraints yet the holding of barazas requires mobilising people at least a week before, hiring a public address system, and a venue that can sit over 500 people. So, there are cost implications and we do not have it in the budget. Barazas are supposed to be funded by Office of the Prime Minister [OPM] but due to shortage of funding, sometimes we lobby from partners to fund those areas and yet some partners are also financially constrained (KII, senior community development officer, Kotido district, June 2018).

Even when they were organised, barazas were characterised by poor attendance by both ordinary citizens and government officials. As a result, as a citizen-driven accountability platform that was anticipated to bring citizens and leaders together they have not been effective.

On the other hand, while accountability was not easily achieved through administrative ‘enforcement’, answerability for leaders’ actions or inaction at elections was relatively effective. For instance, in Kotido district at the 2016 general elections, only four out of 18 councillors were re-elected to office. It seems that the main reason for non-election was poor performance: those who failed to deliver on their campaign promises were not returned (KII, clerk to council, Kotido district, 23 May 2018). However, the downside of this mechanism is that the electors have to wait five years before they can act. Over that time a lot of damage could be done.

Evidence from previous studies that looked at downward accountability in local governments in Uganda also identified significant gaps that needed to be addressed in order to enhance district council performance (Bainomugisha et al. 2020, p. 39). Studies on decentralisation reforms in other parts of Africa make similar findings. Wunsch (2014, p. 2), for instance, finds that whereas there has been some downward accountability by sub-national governments to local citizens through increasingly institutionalised elections, in many cases accountability continues to flow mostly upwards to actors at the centre. Dickovick and Riedl (2014, pp. 245–257) concur. They further note that limited fiscal autonomy in sub-national governments reduces downward accountability, because taxpayers cannot see a direct link between their local tax effort and the supply of public goods when there is heavy reliance on intergovernmental transfers.

Conclusion and recommendations

The research in this paper analysed the extent to which decentralisation policy reforms introduced in 1992 in Uganda have achieved the objective of politically empowering ordinary citizens in Karamoja, a sub-region that has historically been isolated and marginalised. The findings established that while excellent laws, structures and processes were created, implementation of the reforms did not measure up to expectations. State–society power relations have remained largely unaltered and in favour of the ruling political and bureaucratic elites, who control decision-making and in many cases use government as an instrument to satisfy their vested interests. They exercise power over resources to the detriment of ordinary citizens, who have been marginalised in the decision-making process by a failure to implement the various local mechanisms through which they could voice their demands, as well as by ingrained strong central control over local governments. In short, the intended power of citizens has been usurped by their representatives at both the national and sub-national levels of government.

This brings into question the conventional thinking and belief that decentralisation reforms can empower citizens regardless of political context. The reality is that in environments that are characterised by authoritarianism and weak civil societies, governance reforms that lack real support from political leaders may not achieve much. Also, citizens in countries that are deficient in civil society organisations may find it difficult to wrest power from the dominant elite power-holders.

For political empowerment of citizens to be achieved in Uganda, there is a need for transformation of state–society power relations by meaningful devolution of autonomy to local governments and to their communities. This can be achieved through (a) a reduction in conditional grants as a proportion of central government assistance, and enabling local governments to raise more revenue of their own; (b) making it mandatory for citizens to directly participate in all local government activities that involve planning, implementing and accounting for public programmes and projects; (c) decentralising further to the parish level, enabling government support often to be sent directly, rather than through the district, which may be too distant from the citizens’ access and control; (d) enhancing information access, including strengthening local mechanisms such as barazas which offer more participatory channels for citizens to hold government officials accountable; and (e) imposing serious penalties on those government officials (elected or administrative) who attempt to undermine public transparency and accountability. These measures must also be accompanied by mass education of citizens to enable them to claim their civic rights and to understand their own obligations under the constitution.

Acknowledgments

The MAKERERE-SIDA Bilateral Study Scholarship Programme 2015–2022 provided financial assistance to the authors for their research. Additional thanks are due to the study participants and the Karamoja districts of Moroto and Kotido for their assistance and cooperation during the fieldwork.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the publication of this article.

References

Azfar, O., Livingston, J. and Meagher, P. (2006) Decentralisation in Uganda. In: Bardhan, P. and Mookherjee, D. (eds.) Decentralisation and local governance in developing countries: a comparative perspective, (pp. 223–255). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/2297.003.0008

Bainomugisha, A., Mbabazi, J., Muhwezi, W.W., Bogere, G., Atukunda, P., Ssemakula, E.G., Otile, O.M., Kasalirwe, F., Mukwaya, R.N., Akena, W. and Ayesigwa, R. (2020) The local government councils scorecard FY 2018/19: the next big steps; consolidating gains of decentralisation and repositioning the local government sector in Uganda. ACODE Policy Research Paper Series No.96. Kampala: ACODE.

Brosio, G. (2000) Decentralisation in Africa. Paper prepared for the African Department of the IMF, Washington, DC.

Burke, F. (1964) Local government and politics in Uganda. Syracuse and New York: Syracuse University Press.

Budryte, D. (2014) Political empowerment. In: Michalos, A.C. (ed.) Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research. Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5_2196

Burgman, C., Gage, C., Cronin, C. and Mitra, R. (2007) Our rights our information: empowering people to demand rights through knowledge. New Delhi: Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative.

Chambers, R. (1983) Rural development: putting the last first. London: Longman.

Combaz, E. and Mcloughlin, C. (2014) Voice, empowerment and accountability: topic guide. Birmingham, UK: GSDRC, University of Birmingham.

Crook, R. and Manor, J. (1998) Democracy and decentralisation in South Asia and West Africa. participation, accountability and performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9780511607899

Deetz, S. (1996) Crossroads – describing differences in approaches to organization science: rethinking Burrell and Morgan and their legacy. Organization Science, 7 (2), 191–207. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.7.2.191

Dickovick, T.J. and Riedl, R.B. (2014) Comparative assessment of decentralisation in Africa: final report and summary of findings. Burlington, Vermont: United States Agency for International Development. USAID ARD, Inc.

Dovi, S. (2006) Political representation. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/political-representation/

Eaton, K., Kaiser, K. and Smoke, P. (2011) The political economy of decentralisation reforms: implication for aid effectiveness. Washington, DC: The World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-0-8213-8840-2

Francis, P. and James, R. (2003) Balancing rural poverty reduction and citizen participation: the contradictions of Uganda’s decentralisation program. World Development, 31 (2), 325–337. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(02)00190-0

Ggoobi, R. and Lukwago, D. (2019) Financing local governments in Uganda: an analysis of the proposed national budget FY 2019/2020. ACODE Policy Research Series No. 92. Kampala: Advocates Coalition for Development and Environment (ACODE).

Government of Uganda (GoU) (1993a) Decentralisation in Uganda: the policy and its implications. Kampala: Government of Uganda.

Government of Uganda (GoU) (1993b) The Local Governments (Resistance Councils) Statute 1993. Statute Supplement No. 8 of December 1993. Entebbe, Uganda: Uganda Government Printers and Publishers Corporation.

Government of Uganda (GoU) (1995) Constitution of the Republic of Uganda. Kampala: Government of Uganda.

Government of Uganda (GoU) (1997) The Local Governments Act Cap. 243. Kampala: Government of Uganda.

Government of Uganda (GoU) (2005) Access to Information Act 2005. Kampala: Government Printer.

Government of Uganda (GoU) (2011) The access to information regulations of 2011. Statutory Instruments Supplement No. 10 of 21st April, 2011. Entebbe: UPPC, Government of Uganda.

Hicks, U.K. (1961) Development from below: local government and finance in developing countries of the Commonwealth. Oxford: Clarendon.

Hitchcock, G. and Hughes, D.P. (1989) Research and the teacher: a qualitative introduction to school-based research. Oxfordshire, England, UK: Routledge.

Integrated Food Security Phase Classification. (2021) Uganda-Karamoja IPC acute food insecurity analysis. Kampala: Ministry of Agriculture Animal Industry and Fisheries (MAAIF).

Kaaya, S.K. (2016) Uganda: how decentralisation policy was killed in 10 Years. The Observer, 29 June 2016 Kampala. Available at: http://allafrica.com/stories/201606290713.html

Kabeer, N. (1999) Resources, agency, achievements: reflections on the measurements of women’s empowerment. Development and Change, 30, 435–464.

Kakumba, U. (2010) Local government citizen participation and rural development: reflections on Uganda’s decentralisation system. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 76 (1), 171–186. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852309359049

Kimengsi, J.N. and Gwan, S.A. (2017) Reflections on decentralisation, community empowerment and sustainable development in Cameroon. International Journal of Emerging Trends in Social Sciences, 1 (2), 53–60. https://doi.org/10.20448/2001.12.53.60

Lambright, G. (2011) Decentralisation in Uganda: explaining successes and failures in local governance. Boulder, CO: First Forum Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781935049999

Leach, M. and Scoones, I. (2007) Mobilising citizens: social movements and the politics of knowledge. IDS Working Paper No. 276. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies.

Lukes, S. (1974) Power: a radical view. London: Macmillan.

Mamdani, M. (1982) Karamoja: colonial roots of famine in North-East Uganda. Review of African Political Economy, 9 (25), 66–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/03056248208703517

Manor, J. (1999) The political economy of democratic decentralisation in developing countries. Washington, DC: World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/0-8213-4470-6

Marijani, R. (2017) Community participation in the decentralised health and water services delivery in Tanzania. Journal of Water Resource and Protection, 9, 637–655. https://doi.org/10.4236/jwarp.2017.96043

Muhumuza, W. (2008) Pitfalls of decentralisation reforms in transitional societies: the case of Uganda. African Development, 33 (4), 59–81. https://doi.org/10.4314/ad.v33i4.57343

Muhumuza, W. (2013) The performance of decentralization and public sector accountability reforms in Uganda. In: Chanie, P. and Mihyo, P.B. (eds.) Thirty years of public sector reforms in Africa: selected country experiences, (pp. 267–293). Addis Ababa: OSSREA.

Närman, A. (2003) Karamoja: is peace possible? Review of African Political Economy, (30) 95, 129–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/03056240308370

Ndegwa, S. and Levy, B. (2003) The politics of decentralisation in Africa: a comparative analysis. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Nsibambi, A. (2014) National integration in Uganda 1962–2013. Kampala: Fountain Publishers.

Owiny, C.D. (2006) Providing non-formal education to the semi-nomadic Bahima and Karimojong pastoralists in Uganda. Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of South Africa.

Reeves, T.C. and Hedberg, J.G. (2003) Interactive learning systems evaluation. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology Publications.

Reyes-Garcia, V., Vadez, V., Aragon, J., Huanca, T. and Jagger, P. (2010) The uneven reach of decentralisation: a case study among indigenous peoples in the Bolivian Amazon. International Political Science Review, 31 (2), 229–243. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512110364257

Sakyi, E.K. (2013) A critical review of the theoretical objectives and practical experiences of decentralisation from the perspective of developing African countries. Legon, Ghana: Department of Public Administration and Health Services Management, University of Ghana.

Smoke, P., Muhumuza, W. and Ssewankambo, E. (2014) Uganda: decentralisation reforms, reversals, and an uncertain future. In: Dickovich, T. and Wunsch. J. (eds.) Decentralization in Africa: a comparative perspective, (pp. 229–248). Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781626373266-012

Sundström, A., Paxton, P., Wang, Y.-T. and Lindberg, S. (2015) Women’s political empowerment: a new global index, 1900–2012. University of Gothenburg: Varieties of Democracy Institute, Working Paper 19. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2704785

Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) (2017) The national population and housing census 2014 – area specific profile series. Kampala, Uganda: UBOS.

Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) (2020) Statistical abstract. Kampala, Uganda: UBOS.

Uganda Human Rights Commission (UHRC) (2018) The 21st annual report on the state of human rights and freedoms in Uganda in 2018. Kampala. Uganda: UHRC.

Welzel, C. (2013) Freedom rising human empowerment and the quest for emancipation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139540919

Wunsch, J.S. (2014) Decentralisation: theoretical, conceptual, and analytical issues. In: Dickovick, J.T. and Wunsch, J.S. (eds.) Decentralisation in Africa: the paradox of state strength. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, Inc.

Young, K. (1993) Planning development with women: making a world of difference. London: Macmillan.