Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance

Issue 27

December 2022

POLICY AND PRACTICE

Supporting Local Councillors: Learnings from Post-Election Interviews in New South Wales, Australia

The Centium Group, Sydney, NSW 2000, Australia

Corresponding author: Sarah Artist, The Centium Group, Sydney, NSW 2000, Australia, sarah.artist@centium.com.au

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi27.8465

Article History: Received 30/10/2022; Accepted 17/11/2022; Published 20/12/2022

Citation: Artist, S. 2022. Supporting Local Councillors: Learnings from Post-Election Interviews in New South Wales, Australia. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, 27, 181–187. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi27.8465

© 2022 by the author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercial, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Introduction

Local councillors play a fundamental role at the community level in our democracy. They help to shape the places they live and work in, and in so doing they come to understand many of the most difficult and most critical pressures facing their communities. Communities expect their elected councillors to listen to their ideas, take their complaints seriously, and ensure that decisions about planning, policies and resourcing priorities are made in their best interests. Moreover, local government is often a training ground for further leadership roles, whether in government at other levels or in other walks of life.

Methods

This practice note summarises information collected from 56 interviews with outgoing and newly elected councillors across four municipalities in New South Wales, Australia, following the local elections held in December 2021. The aim was to harness that information to shape and direct the support new councillors need to fulfil their roles. Verbatim quotes from the interviews are indented and italicised, as they are the voices of the participants.

The process allowed all councillors to speak freely knowing that all interviews were de-identified and anonymous. In a ‘thinking out loud’ environment, talking one-on-one away from the rigours and restrictions of public debate, councillors were empowered to express their own aspirations and priorities, and to consider the most important issues facing constituents and their communities. Outgoing councillors, for whom this was like an ‘exit interview’, were also able to articulate the challenges and difficulties they experienced during their term on council.

Local government in New South Wales

There are 128 municipalities (commonly called ‘councils’) in New South Wales (NSW), constituted under the NSW Local Government Act 1993 (subsequently referred to as ‘the Act’). The districts they govern are diverse and include metropolitan centres and suburbs, the urban fringe, regional towns and villages, and rural and remote areas. Populations within each council area range from the smallest with 1,553 people (Brewarrina Shire in the remote far west of the state) to the most populous with 382,831 (Blacktown City in the rapidly growing western suburbs of metropolitan Sydney). NSW councils also vary in staff numbers: from the smallest, the suburban municipality of Hunters Hill in Sydney, with only 30 staff, up to the central City of Sydney with 1,730.1 The four councils that are the subject of this article are all in metropolitan Sydney, though they range from small to large organisations and include both inner city and urban fringe areas.

The functions of NSW councils vary depending on historic and community factors as well as legislative provisions and funding pressures. Unlike local governments elsewhere in the world, they do not as a general rule control policing, public transport, health, education, social housing or major infrastructure planning and provision. Also, their role in shaping development within their areas has diminished due to recent state government reforms that have increasingly centralised control. Nevertheless, all these issues are still of vital interest to people elected to councils, so priority concerns for individual councillors span subject areas both within and outside their control.

Individual councillors make-up the council’s ‘governing body’, whose role is defined in the Act (Section 223) as being principally:

• to direct and control the affairs of the council

• to provide effective civic leadership to the local community

• to develop and endorse the strategic plans, programmes and policies of the council

• to keep under review the performance of the council, including service delivery

• to make decisions necessary for the proper exercise of the council’s regulatory functions.

The Act places ‘day-to-day’ management of municipal affairs in the hands of the appointed general manager and senior staff, albeit subject to council policies. To facilitate agreement on a shared agenda, including extensive engagement with the local community, a strategic planning framework – known as Integrated Planning and Reporting (IP&R) – was added to the Act in 2009. This includes a review of existing plans after the election of each new council, in order (among other things) to allow newly elected councillors to frame their strategic directions. IP&R is seen as a key process by which Councillors can exercise their responsibilities as a governing body, but it is a demanding one, both conceptually and in terms of the effort involved.

The 2021 elections

After being postponed twice due to the impact of COVID-19, NSW council elections were held in December 2021 rather than September 2020. The extended council term from 2016 to 2021 had been particularly challenging for a number of reasons, including natural disasters such bushfires and floods, COVID-19 lockdowns, as well as an additional mandatory year in the role for councillors. This may have contributed to many councillors deciding not to stand for re-election. In the councils that participated in the interviews that are the subject of this practice note, there was a turnover rate of 44%: of the 54 elected member positions across the four councils, 24 were filled by newly elected councillors.

The 2021 post-election induction process was also particularly challenging because the second delay in holding the elections, from September to December 2021, compressed the timeframe within which to meet legislative deadlines, including those for reviewing strategic plans, policies and budgets. Newly elected councillors and their councils had to complete mandatory tasks during the normal summer break. Moreover, because the next elections are scheduled for September 2024, the upcoming council term is considerably shorter than the usual four years, so new Councils have less time to pursue their goals and priorities. All this placed heavy pressure on councillors, many of whom were ill prepared and needed more guidance:

There needs to be a better process in bringing councillors along in designing the budget. We’re only getting high-level advice, and many don’t understand it. We need a better process to unpack the detail, to understand and have input. We need a proper discussion about allocating priorities and resources.

Induction and professional development

A good post-election induction process is essential to ensure that the new council understands the legal responsibilities of its role, builds a sense of camaraderie and willingness to work together, and sets up parameters to guide future decisions about priorities and programmes. It is easy for staff to imagine that new councillors know more than they actually do. One new councillor commented:

We need to work harder to make sure the councillors understand better. We need so much more education – not just about the programmes, but about how to work together.

In particular, new councillors need to appreciate the numerous constraints on their role and behaviour, which are heavily regulated by the Act, and the regulations prescribed for elected officials including the Code of Conduct and Code of Meeting Practice. Newly elected councillors may not fully anticipate this before they are elected. It can be a significant source of frustration and disengagement when people nominate for and are elected into a position with the intention to make changes that they find later are not within their powers. In addition, most individual councillors do not have any formal duties beyond that of collective decision-making within the structure of formal council and committee meetings.2 This lack of individual autonomy and authority can easily become disempowering and frustrating.

New councillors therefore need to learn quickly how the council actually operates in practice and how they can exercise influence. They need legislative training on Code of Conduct requirements, particularly to understand conflicts of interest and how to identify and manage those. Code of Meeting Practice training is also important:

We needed Code of Meeting practice training: what our role is and how to conduct ourselves in a meeting. It could cover the rules of debate, points of order, chairing meetings. How do you write a notice of motion? When should it be a motion rather than general business? It took me ages to work out why you get the same information for different kinds of meetings.

Another key area is land use planning and control of development. New councillors need to be educated on issues such as terminology, potential impacts of development, the level of control the council can exercise (given close oversight and involvement by state agencies), and how to get better solutions to resolve community conflict. Site visits are a good way of giving new councillors a sense of what’s going on and where, as well as the scope of development projects.

Ongoing training is required for all councillors to ensure they keep up to date during their time on council. Councils could be more proactive about anticipating the skills and knowledge for councillors’ continuing professional development:

We need better ways of accessing training options, better standard councillor training every 12 months that’s relevant, and that’s opt in, especially when there are changes to legislation. What about staff briefings on webinars, so we can access them when we need them?

Guidelines have been issued in NSW which prescribe the preparation of individually tailored professional development plans for each elected member and for the full term of the council. This requirement is intended to embed the ongoing assessment of capability gaps and provision of training options. Although compliance with these guidelines is not monitored or reported, it is hoped that they provide some momentum and energy towards a more rigorous approach.

Accessing information

New councillors are contacted immediately after their election by constituents with issues, concerns and complaints, and a few key staff should be nominated as contacts to help with the most common of these and also to explain constraints and realities in dealing with them. New councillors should learn to understand and trust the broader prioritising process that usually exists to handle specific complaints and requests, so that they can maintain a strategic overview of quality and direction without getting inappropriately involved in individual matters:

If we have oversight at a high level then we can trust the systems to handle our requests too.

Timeframes for responses are an important part of the equity of the complaints handling system, and councillors need clear and reliable information about how requests will be processed and what are reasonable timeframes for responses.

There are many community events that councillors may choose to attend, and an effective council calendar will allow them to see everything coming up and enable them to plan their attendance.

After decisions are made by the governing body, councillors look for reports on where resolutions are up to: what’s the status of each matter, what’s in train, and what’s been enacted. To manage all the information that they receive, including often lengthy business papers, many councils are moving to an intranet-type system:

We need something a bit more refined so that critical, timely and relevant documents can be accessed quickly. We need this to counteract councillors’ complaints that they didn’t receive something - if it’s on the portal then people can go and refresh their own memory rather than making an issue of it. The portal needs a file structure and an index.

Working relations with council staff

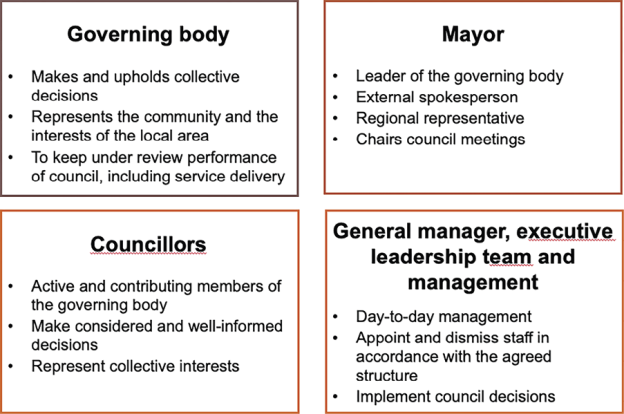

As noted earlier, the Act prescribes particular roles for the mayor, councillors, general manager and other staff. Key points are summarised in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. Roles and responsibilities within NSW councils

The interface between elected members and professional staff is unique in local government, and the Act contains within the role statements a number of references to working in a collaborative way. There are various factors which sometimes combine to make the relationships difficult to navigate:

I’ve experienced senior staff who worked very hard to show that they were here for all of us. We had a serious level of respect for those staff. There were people who made sure it was a ‘no embarrassment’ council. The trust needs to be developed to have an exchange of views with councillors in a non-adversarial way.

Different councillors work in different ways; they are busy people and so are staff. Communication between councillors and staff needs to adapt to their respective needs – including appropriate use of emails or phone calls and making contact at times that suit all parties.

Some of us have day jobs, and I try to phone staff in my lunch hour and leave a message, but they ring back when we’re at work too.

At its best the communication between councillors and staff is a genuine engagement, building a common knowledge base and a stronger consensus:

There need to be more briefings with councillors before issues come to council, and actually with enough time to have an influence and in the shaping process. Councillors should be taking an active role; not to take away from the role of the specialists [but] we shouldn’t be left till the end of the process with something we don’t want to support.

Building and maintaining a productive culture

The culture of the governing body plays a crucial role in a high-functioning council, and specific strategies can be introduced to ensure that councillors are guided and supported to enhance the reputation and performance of their councils. There are various ways to create and build a positive culture amongst the governing body:

We need to build the capacity for robust debate, that is based on respect and good humour, and helps to develop good relationships.

Social occasions like supper after a council meeting or celebrating special days and events can offer councillors informal opportunities to get to know each other.

On the other hand, the behaviour of some ‘difficult’ councillors can derail the culture and cause churn at the senior staff level. One or two people can do considerable damage, and councils need better strategies for dealing with them. Politically-motivated dislike, one-upmanship, lack of respect, a councillor’s wish to win extra benefits for their local ward – all these attitudes and behaviours may cause divisions, destroy consensus and jeopardise collective decisions. Firm but respectful action is required throughout the organisation to deal with difficult councillors so that the focus is always on the best interests of the whole community:

The strategic retreats were quite good. They didn’t need to be so salubrious, but it was a strategic meeting together and an opportunity to talk things through. They could substitute the briefings with more strategic meetings, it needs to happen more frequently. Say check-ins quarterly – around the bigger issues and having more input as councillors. Otherwise it’s not genuine dialogue, it doesn’t feel like we’re coming together to have genuine input.

Conclusion

In summary, to fulfil their democratic role elected members require more and better information when they come onto council, as well as an ongoing programme of targeted professional development throughout their term. Professional staff need to ensure that councillors receive the information that they need in a way that they can access, and in enough time for careful consideration and to inform better decisions. The various players within the council should work in a collaborative way to support the decision-making role of the governing body, and individual councillors need to work together to set a common agenda and shared strategy that reflects camaraderie and consensus.

But in a complex, demanding and often tense operating environment none of that is easily achieved. During the interviews some of the councillors who had been on council for a long time were feeling quite disillusioned and disempowered. This evidently reflected a view that the role of local government in general and of councillors in particular had been weakened by legislative change and state interventions:

Decision-making has been taken away from councillors,[so] it’s so much harder to make a difference. We can’t provide genuine input, but we are responsible for our community who look to us for certain things. We used to facilitate things and get things to happen but we’ve lost the capacity to make decisions for our local people.

This article has focused on ways that councils can support their elected members to fulfil their responsibilities, but it also points to systemic factors which may be making their role more difficult. State government oversight bodies such as the NSW Office of Local Government could provide better definition, support and consideration for the role of democratically elected local representatives. A greater effort is needed to ensure that people elected to local councils can deliver strong and effective civic leadership for the places and communities that matter to all concerned.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

1 2020–2021 NSW Office of Local Government comparative information (see https://www.olg.nsw.gov.au/public/about-councils/comparative-council-information/your-council-report/).

2 The mayor has additional responsibilities for leadership and liaising with the general manager, and some councillors may be appointed to chair committees or represent the council on other organisations and forums.