Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance

Issue 27

December 2022

RESEARCH AND EVALUATION (PEER REVIEWED)

Designing and Implementing a Local Residential Property Tax from Scratch: Lessons from the Republic of Ireland

J E Cairnes School of Business and Economics, University of Galway, Galway, H91 YK8V, Ireland

Corresponding author: Gerard Turley, J E Cairnes School of Business and Economics, University of Galway, Galway, H91 YK8V, Ireland, gerard.turley@universityofgalway.ie

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi27.8464

Article History: Received 01/10/2022; Accepted 24/11/2022; Published 20/12/2022

Citation: Turley, G. 2022. Designing and Implementing a Local Residential Property Tax from Scratch: Lessons from the Republic of Ireland. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, 27, 83–101. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi27.8464

© 2022 by the author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercial, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Abstract

Assigning recurrent taxes on immovable property to cities, municipalities, and rural districts is a common practice around the world. The Republic of Ireland is no different, with its annual taxes on real property assigned to local government. Following the 2008 financial crisis and the austerity era that ensued, Ireland’s property taxes underwent major reform, most notably the design and implementation of a new residential property tax 35 years after abolition of the previous system of ‘rates’ on residential properties. In this paper the new or different features of Ireland’s residential property tax are outlined, including the use of self-assessment and valuation bands, innovative payment methods and also the multiple compliance mechanisms for taxpayers. While recognising the importance of country-specific and local circumstances in property tax design, the paper concludes that elements of Ireland’s new residential property tax have potential lessons for other jurisdictions contemplating similar tax reform. These relate to the key tax principles of simplicity and public acceptability, and on specific design features of assessment and valuation, and collection and compliance.

Keywords

Property Tax; Local Government; Tax Design; Lessons

Introduction

Worldwide, local governments (‘councils’ in Ireland) are typically funded by a combination of own-source revenues (mainly local taxes and charges) and grants or transfers from higher levels of government. The Irish system of local government is no exception as it is funded by a mix of local taxes, fees/charges, and central government grants.1 The only local tax is on immovable or real property, with annual taxes on the ownership and use of residential and non-residential properties fully assigned to Ireland’s local councils (Turley and McNena 2019).

One of the stylised facts of local property taxes worldwide is their diversity, both in terms of the amount of revenues that are raised and, more relevant for this paper, their design features and characteristics. Using the background of a country that is highly centralised, with an economy and property market that suffered enormously from the 2008 financial crisis, and whose public finances were subject to much austerity in the 2010s, this paper outlines the property tax reforms that were designed and successfully implemented at that time despite strong political and public opposition. Central to these reforms was the introduction of a new residential property tax in 2013: there had been no annual tax on residential properties since 1978 when the previous form of property tax (domestic ‘rates’) was abolished. In particular, a number of property tax design features were introduced that have “interesting peculiarities that makes it [ie the Irish system] relevant for countries that aim at implementing a reform nearly from scratch” (OECD 2021, p. 118). This study describes these features and, in doing so, identifies potential lessons for other jurisdictions contemplating property tax reform, albeit in different political settings and economic circumstances.

The paper begins with the theory of local government and tax assignment. The following section provides some country-specific context on local government finance in Ireland. The residential property tax reforms are then outlined, with a focus on the different or new system features. The paper ends with a discussion and some lessons from the Irish experience.

Local government and tax assignment: the theory2

Compared to central government provision of uniform services, local government achieves greater economic efficiency by facilitating the matching of public service outputs with local preferences. Using the benefit taxation model, in order to maintain the link between benefits received and taxes paid, those who benefit from local government expenditure should pay for it. Where benefits do not extend beyond definable local areas, allocative efficiency can be best achieved by providing public services at the lowest feasible level of government (Oates 1972).

As long as there are differing preferences for the outputs of local public goods and different costs in local public service delivery from place to place, there are welfare gains from fiscal decentralisation. Formalised by Oates (1972), this fiscal decentralisation theorem presents the economic case for local government. A summary of the theorem is that by “tailoring the outputs of local public goods to the particular tastes and costs of specific jurisdictions, the decentralised provision of local public goods promises higher levels of social welfare than a centralised regime with more uniform levels of outputs across all jurisdictions” (Oates 2010, p. 10).

An earlier and rather different perspective was presented by Tiebout in his theoretical model of consumer-voter choice. If citizens – seen as consumers – are faced with a choice of areas offering different types and levels of public services, as consumers they will choose the local area that best reflects their preferences, by ‘voting with their feet’ (Tiebout 1956). In this case, a political solution is not required to provide the optimal level of public goods as the market is said to be efficient.

Not altogether dissimilar, but more focused on the design of jurisdictions, Olson’s principle of fiscal equivalence assigns revenue-generation powers to central and local governments commensurate with expenditure responsibilities and, where possible, aims for a close match between benefit, tax and electoral areas. Adopting this approach, when citizens reside in several overlapping jurisdictions, they should pay taxes to each level corresponding to the benefits that they receive from each jurisdiction (Olson 1969).

Once expenditures have been assigned according to the fiscal decentralisation theory set out above, the next step is to assign appropriate revenues, in the form of taxes, transfers or borrowing. Together, these elements constitute the four pillars of intergovernmental fiscal relations.3 This paper focuses on the issue of tax assignment: who should tax what?

The decision as to which taxes should be assigned to which levels of government constitutes the tax assignment problem of intergovernmental finance. Although the traditional fiscal federalism model underlying expenditure assignment is straightforward, with local government primarily responsible for the efficient provision of local public services characterised by few spillovers and limited economies of scale, that is not the case for tax assignment (Musgrave 1983).

The taxes assigned to local government should meet certain criteria. As set out in Bird (2001), the characteristics of a good local tax are that the tax base should be relatively immobile and visible; the tax should be mainly borne by local residents and not easily exported; it should be relatively evenly distributed, perceived as reasonably fair and relatively easy to administer; and the tax yield should be adequate to meet local needs and be relatively stable and predictable. The tax that best meets these criteria is property tax.4

Relative to other potential sources of local tax revenues, a local property tax scores highly in several ways. First, land and/or buildings are obviously immobile and salient; second, the tax on such is borne primarily by local residents who benefit from the services supplied; third, information required is likely to be available locally; and fourth, the property tax yield is relatively stable and varies less with the business cycle than other taxes.5 In addition, a well-designed property tax is relatively neutral with respect to its impact on economic decision-making and behaviour (Bird 2006; Slack 2015).

Overall, property tax is a mainstay of municipal finance, with a majority of local governments worldwide relying on some form of recurrent property tax.6 Indeed, in this instance we can say that the public finance theory and practice coincide, as any rational assignment of taxing powers should see local government assigned a tax on real property. Bird (2006, pp. 181–184) writes that a “property tax is indeed an excellent local tax”, and “undoubtedly the pre-eminent local tax”. Similarly, the Mirrlees Review in the UK noted that: “The fact that land and property have identifiable and unchangeable geographic locations also makes them natural tax bases for the financing of local government” (Mirrlees 2011, p. 368).

Country context: local government finance in Ireland

Ireland, with a population of just over five million and a surface area of 70,000 km2, is a unitary country with two levels of government, central and local. The local government tier consists of 31 councils: three city councils, 26 county councils, and two combined city/county councils. The sub-county town governments were abolished in 2014 as part of a wider reform of the public sector, largely motivated by efficiency gains, cost reductions, and austerity measures (Government of Ireland 2014).

Ireland has a very centralised system of governance, with limited functions assigned to local government. This is partly due to the inherited British tradition, but also a general disdain by successive Irish governments for local administration, which was often perceived as inefficient and corrupt (Callanan 2018). In the early days of independence, there was a preference for central control, with national regulation of local government that has not diminished over time.

Local government’s narrow remit is in the provision of purely local services and social housing. The main functional responsibilities are in the area of local and regional roads, planning and land use, local economic and community development, fire and library services, local amenities, and the provision of housing services.7 Unlike many other sub-national jurisdictions, Irish local government has no role in the delivery of health, education or social care services.

Comprising a mix of transfers from central government and own-source revenues, the funding of local government in Ireland comes from three sources: grants, charges and fees for services, and local taxes. The local tax is a property tax, with two components: one tax on non-residential properties (commercial rates) and a separate one on residential properties (the Local Property Tax, or simply LPT).8 A breakdown of local government revenue sources is presented in Table 1. Although it is common worldwide for local authorities to tax non-residential properties relatively more than residential properties – often for political rather than economic reasons – the difference between the shares generated from commercial rates and from LPT as reported here is striking. The paper returns to this issue in the final section.

Source: Author’s calculations.

In sum, Ireland’s system of local government is relatively small – primarily a provider of local services; it is funded by a mix of central government specific-purpose grants and own-source revenues in the form of charges/fees and local property taxes; and it is limited in terms of autonomy as central–local relations are characterised by extensive regulatory, administrative and financial controls by central government (Turley and McNena 2019).

Another outstanding and rather unique feature of local government finance in Ireland at the outset of the 21st century, and until 2013, was the absence of a residential property tax.

The new residential property tax

The common design features of any residential property tax are the tax base, liability, rate, assessment, valuation, and collection/compliance. Property tax system features and the main options available to the Irish authorities at the outset of considering the new tax are outlined in Table 2.

| Elements | Tax base | Liability | Rate | Assessment | Valuation | Collection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Features/Options | Land and buildings or land only or buildings only |

Owner or occupier or both |

Central and/or local |

Area-based or value-based or hybrid |

Capital or rental | Central or local |

| Uniform or differentiated | Direct assessment or self-assessment |

Individual or bands | Payment options? | |||

| Exemptions, reliefs and deferrals? | Single or graduated | Central or local | Indexation and/or revaluation | |||

| Government (central/local) and agency type? |

Source: Author. The actual design characteristics chosen for the new LPT are in bold.

The design of any property tax system, however, is not simply a technical matter, but depends on other factors such as the economic and political circumstances of the time, as well as the history of property taxes pertaining to the specific jurisdiction. Prior to 1978, residential properties in Ireland were subject to property tax in the form of (domestic) rates, similar in design to the commercial rates regime that existed then and still applies to non-residential properties.9 The two common criticisms of the domestic rates system and the reasons for its abolition were a) the steep rises in rates largely attributable to rising health expenditures (that were at the time devolved to local authorities), and b) out-of-date valuations leading to inequities and a regime considered to be regressive and unfair (Callanan 2018).

Given the prevalence of residential property taxes in developed countries, the absence of a recurring tax on residential properties meant that Ireland was an outlier, with successive governments under pressure to correct this anomaly. Although there was a succession of reviews of local government funding and taxation that recommended a local residential property tax, it was the 2008 financial crisis that triggered its reintroduction. Given the booming property market and imprudent taxation decisions taken by national policy-makers leading up to the 2008/09 economic crisis, a condition of the financial support provided to Ireland by the European Commission, International Monetary Fund and European Central Bank was the introduction of a residential property tax as a means to widen the tax base.

At the outset, there were a number of problems to be addressed. There was much political and popular resistance to a new tax, and especially one on property given Ireland’s historical affinity to land and home ownership. There was also opposition due to the difficult economic environment of the time, dominated by years of austerity. On a more technical level, there were significant logistical challenges facing the authorities (and the national tax collection agency, known simply as Revenue) – and none more so than the absence of a single and comprehensive database with up-to-date information on property ownership and valuations.

In 2012, an Inter-Departmental Group was established to design a ‘local property tax’ – which later became the LPT. Guided by the usual tax principles of efficiency, equity, simplicity and transparency, the terms of reference were to consider the design of a tax that would, among other objectives, “provide a stable funding base for the local authority sector” and “ensure the maximum degree of fairness between and across both urban and rural areas” (Inter-Departmental Group 2012, pp. 116–117).10

As with any new property tax, and in this case one assigned to local government, the Group examined all the key design elements of a property tax. Its principal recommendations are reported in Table 3.

| Design features | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Liability, base and exemptions | Owners of residential properties be liable for the tax, but with certain exemptions permitted |

| Assessment and valuation | Market value (including improvements) of residential properties using valuation bands and the tax rate applied to the mid-point, with a system of self-assessment Development of a register of residential properties be undertaken as a priority |

| Local autonomy | All revenues accrue to the local authorities, incorporating a locally determined element |

| Administration agency | Revenue, the national tax collection agency, be given responsibility for all aspects of the local property tax |

| Payment methods | Provision for collection at source from payroll and from recurring and lump-sum payments made by government departments |

Source: Adapted from Inter-Departmental Group (2012).

With the Irish Government adopting the majority of the Inter-Departmental Group’s recommendations, including all of the above, this report formed the basis of the new LPT (Government of Ireland 2012).11 The timelines for the reform process are shown in Table 4.

| July 2012 | Inter-Departmental Group report published |

| 2012 | Interim €100 household charge |

| December 2012 | Finance (Local Property Tax) Act 2012 enacted |

| Announced on national 2013 Budget Day | |

| March 2013 | Launched, property register compiled, followed by taxpayers’ education and communication campaign |

| LPT return form and information issued | |

| May 2013 | Property valuation by self-assessment (and for the next three years) |

| LPT return to be filed | |

| July 2013 | Payment due |

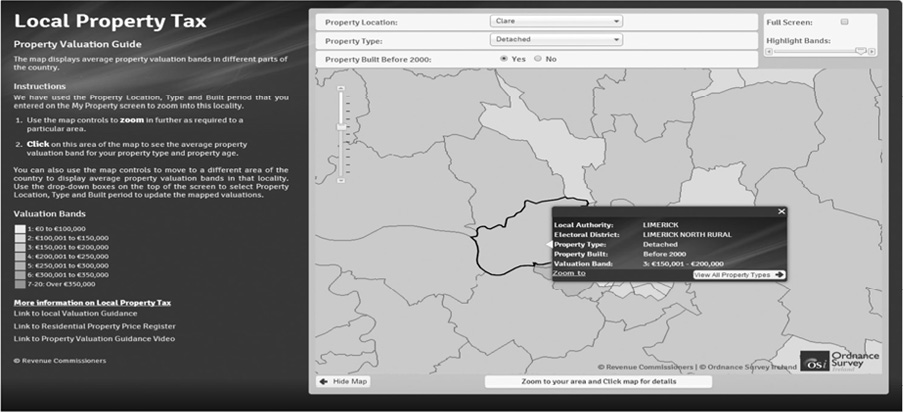

One of the biggest challenges in designing the new tax related to assessment and valuation, given the absence of an up-to-date database of residential properties. This may explain the decision to opt for self-assessment and the use of valuation bands. Revenue did provide guidance to taxpayers (see Figure 1), in the form of an online interactive guide (namely average property valuation bands in a locality, but not for individual properties); and a ‘Revenue estimate’ was used as a default liability in the absence of a LPT return.12

Figure 1. Property valuation guide

Source: Revenue; Kennedy and Walsh (2016).

Given the indicative nature of the guidance and the provision of average valuation bands only, Kennedy and Walsh (2016, p. 9) noted: “Where the guidance was followed honestly and where it indicates a reasonable valuation for a property, Revenue accepted the owner’s assessment based on the guidance but owners were advised to consider the specifics of their property when using Revenue’s guidance.” The liable person, namely the owner, was required to file an LPT return (essentially the valuation band, with no requirement to return any property characteristics or specific property value) and pay the tax, based on their own assessment of the property’s market value.

The valuation bands were initially €50,000 in width (for 18 of the 20 bands, the first band being from €0 to €100,000 and band 20 being greater than €1 million). The basic rate was 0.18% applied to the mid-point of the relevant band, with a higher rate of 0.25% applied to that portion of a property’s value in excess of €1 million.

From the perspective of local rate-setting powers that are meant to ensure a degree of autonomy and accountability for municipalities, there is a local adjustment factor (LAF) whereby local authorities can vary the basic rate by +/- 15% annually. If the LAF is applied, the tax rate reverts to the normal basic rate after the year has elapsed. Allowing +/- 15% created a potential minimum tax rate (or lower bound) of 0.153% and a maximum rate (or upper bound) of 0.207%. This is not uncommon in other European countries, as a compromise between an upper tier level of government retaining the power to set the rate, and local government having some flexibility to vary the rate to reflect local conditions and ensure a degree of autonomy. Initially local authorities were slow to use this discretion, with a majority of councils in the first few years opting to leave the basic rate unchanged (and those that did use this taxing power all implemented a cut in the rate). Over time, however, the number of local authorities exercising these powers increased, as did the number of councils that increased the rate.

Table 5 reports the number of local authorities that have used the LAF since 2015. The number that varied the rate, increasing from a low of eight in 2017 to 26 in 2022, is a measure of the willingness of local councils to use their autonomy, while the number of councils that have increased the basic rate can be viewed as an indication of both autonomy and responsibility. Whereas no local authority increased the basic rate in the first two years that these powers were in force, 22 used their taxing powers to increase the basic rate in the years 2021 and 2022 (largely to pay for increased spending due to the COVID-19 pandemic), with 11 of them opting for the full +15% variation.

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of councils that varied the basic rate | 14 | 11 | 8 | 11 | 9 | 23 | 25 | 26 |

| No. of those councils that increased the basic rate | 0 | 0 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 19 | 22 | 22 |

Source: Author.

The single biggest issue since the introduction of the LPT has been the rise in residential property prices since the first valuation in May 2013 (which coincided with the trough of property prices reached in early 2013). Property prices rose by an estimated 74% between May 2013 and December 2020, generating concerns about the impact that a revaluation would have on taxpayers’ liabilities. Revaluation was deferred in 2016, and again in 2019/20, finally taking place in November 2021, but only after changes were made to the bands (a widening of the intervals from €50,000 to €87,500 in most cases, equal to an increase of 75% to match the property price increases), and to the basic rate (a reduction to 0.1029%) to ensure that the majority of LPT payers would not see a rise in their liability (Thornhill 2015; Government of Ireland 2021).13

The rate and yield of the LPT (circa €500 million, equal to about 7% of local government revenues and less than 1% of total tax revenue, and diminishing) therefore remain relatively modest by international standards. Another criticism of the LPT is that it is a tax on land and buildings, and not a land or site value tax; with many experts viewing the latter as a better tax – at least in theory – if the objective is to improve urban development and land use.14

Notwithstanding such criticisms, there are many good features of the broad-based, low-rate LPT. From a local public finance and funding perspective, the local authorities have rate-setting powers at the margin. With about 1.9 million properties, compliance rates are very high, at over 95% for payment: no doubt due to the multiple payment options offered by Revenue combined with credible sanctions (see next section). Given the difficulty in introducing new taxes and the high visibility of property tax in particular, the outcome achieved is commendable (Turley 2022). For international comparative purposes, Table 6 reports the features of the LPT compared with residential property tax in selected Commonwealth countries.

Sources: Author; Almy (2013, 2014); Sansom (2020).

Although similarities exist, once again it is the differences in design features that are most striking about property tax, not only those between Commonwealth countries but between nations around the world (Franzsen and McCluskey 2005; Slack 2022). As Almy (2013, p. 3) writes in his global compendium of property tax systems, “There is tremendous diversity in the details of property tax systems, even when they share elements in common with other systems.”

Discussion and lessons

This section re-examines the ‘interesting peculiarities’ of the Irish residential property tax, most notably self-assessment and banding, as well as the issues of collection and compliance, and considers which aspects might be adopted elsewhere. It also suggests some additional lessons for other jurisdictions, relating to simplicity, speed and acceptability.

Assessment and valuation

Assessment is considered the most important feature of property tax design. In the Irish case, assessment has two elements that do not conform to the conventional approach. The first is self-assessment rather than the traditional direct assessment by a valuation agency.15 The second is the use of valuation bands rather than the more usual individual assessment with discrete values. On banding, Kennedy and Walsh (2016, p. 4), note: “It was recognised that property valuation is not an exact science and providing valuation bands eases the valuation challenge.” They also note, on the issue of self-assessment, that it “was seen as being more appropriate given the constraints that applied such as the tight timeframe for implementation and the lack of an existing valuation database of residential properties”. The arguments for and against self-assessment and valuation bands are presented in Table 7. Banding is used in England, Scotland and Wales for council tax, and self-assessment has been used in some cities in India (with Bangalore as the most cited example), and by municipalities in Colombia, most notably Bogotá (Plimmer et al. 2002; UN-HABITAT 2011; Ahmad et al. 2019). Whereas the British experience of a banded council tax may have influenced Ireland’s decision to recommend valuation bands, it is more likely that Revenue’s experience with self-reporting for income tax purposes influenced the decision to recommend self-assessment.

| Self-assessment | Valuation bands | |

|---|---|---|

| Arguments in favour | A low-cost option No need for professional assessors Quick and easy as data requirements are few Requires no appeals process | Simple, making valuation quicker and cheaper More acceptable than an individual valuation Equitable, in that properties of similar value have a similar tax burden Revaluations may be easier and required less frequently |

| Arguments against | Likelihood of incorrect valuations Under-valuations are common Can lead to regressive outcomes Possible high rates of non-compliance | Lacking in accuracy Arbitrary in terms of the number and size of bands Clustering at the threshold values Depending on the design, it can be regressive |

Source: Author; Adapted from McCluskey and Woods (2010).

In theory, banding and self-assessment may be considered second-best solutions compared with the more optimal, common forms of valuation and assessment. Yet the rationale for their selection in the Irish case was clear, given the absence of an up-to-date register of residential properties at the time of design, plus the need to facilitate assessment in a relatively short period, and to increase compliance by making property tax payments generally acceptable to the public. Some ten years on, the issue now is whether these features will be retained as part of a continuing transition, or whether pressure will build to transform them into a more conventional long-term design, and by so doing, address what the OECD (2021, p. 118) describes as “potentially problematic approaches”.16

However, banding is still used for Britain’s council tax 30 years after its introduction, although its structure is slightly different from LPT’s valuation bands (eight or nine bands as against 20 in the Irish case, and greater variation in intervals). The biggest difference between the two jurisdictions in terms of valuation and banding is that a re-banding has been implemented in Ireland whereas in England and Scotland no general re-banding or revaluation has taken place since the introduction of council tax in 1991. In Britain this has resulted in out-of-date valuations, likely inequities in residential property tax liabilities across regions and types of dwellings, and, given the time that has elapsed since the last valuation over 30 years ago and the subsequent property price changes, a tax that is now politically more difficult to reform.

As for their appropriateness for other countries, the argument for self-assessment and valuation bands is strongest when a new system is implemented from scratch and a tailored approach is required, rather than a reform of an existing property tax system where many of the more traditional design features are already likely to be in place. Therefore, although unconventional and second best, self-assessment and banding should not be completely dismissed for other countries, but should be considered on a case-by-case basis, and especially for the few remaining Commonwealth countries that currently do not levy a property tax, those whose property tax is in need of reform, or those whose administrative capacity to assess the valuation of residential properties is weak (Franzsen and McCluskey 2005; Collier et al. 2018). Writing over 20 years ago, Plimmer et al. (2002, p. 80) concluded that “value banding for property tax purposes could have a wider application in terms of international usage”. Ireland’s successful adoption of valuation bands (and the recent re-banding) is an example for others to consider and possibly replicate.

Collection and compliance

In designing the LPT, the Irish authorities prioritised the argument that ‘tax administration is tax policy’.17 While other system features were important, a significant weight was given to tax administration. The decision to focus on the tax administration element was evident in the 2012 Inter-Departmental Group report where six of the 18 recommendations were related to compliance, collection, enforcement and audit. The involvement of the central tax collection agency (Revenue) in the design of the tax, in conjunction with relevant government departments (most particularly Finance and Local Government), combined with the focus on tax administration, collection and enforcement were all evidence of a collection-led rather than valuation-led approach.

An example of this is the multiple payment methods made available to taxpayers aimed at enhancing the convenience of paying taxes (see Table 8). Alongside provision for instalments and other flexible payment arrangements, an unusual option for a property tax is withholding tax at source, integrated into the PAYE (Pay As You Earn) system. This also applies in the case of non-compliance, where Revenue uses its powers to instruct an employer or pension provider to deduct an outstanding LPT liability.18 Together with Revenue clearance on the sale or transfer of residential properties and the use of the aforementioned ‘Revenue estimate’, these features have helped to ensure a very high compliance rate, in excess of 95%. This is notably higher than the equivalent figure for commercial rates, which are collected locally. In this case, the arguments of local knowledge and greater incentives to collect that are usually cited in support of local collection are outweighed by the reputation, powers and economies-of-scale arguments that favour collection centrally.

The decision to assign the administration and collection of the LPT to Revenue was crucial “in gaining the public’s acceptance and in ensuring the legitimacy of a new tax on property” (Turley 2022, p. 22). In the Irish case, the argument for centralisation was strong, not only because of Revenue’s involvement in the design of the tax, but also due to its reputation in collection and enforcement. Although the local authorities have not objected to this centralisation of property tax collection, this design feature is an example of a solution tailored to specific circumstances and should not be taken as universally applicable to all countries and suitable for all property taxes. The normal trade-offs involved when deciding in favour of local versus central collection, such as balancing efficiency with local democracy, need to be considered carefully: one size does not fit all in property tax design and administration.

As well as normal debt collection mechanisms (eg use of Revenue sheriffs, powers of seizure, recourse to courts etc), other payment and enforcement sanctions were deployed, including: surcharges, interest and penalties; withholding of tax clearance certificates; and creation of a lien or charge on the property. Although many of these measures are not unique to Ireland, when combined they make for an administrative system that works well and that other jurisdictions could adopt. The same applies to Revenue’s use of online services for taxpayers, not just for payment but also for self-assessing property valuations and filing LPT returns; with, for example, 94% of returns filed online as of May 2022 (Revenue 2022).

| 2013 | 2021 | |

|---|---|---|

| Annual debit instruction | - | 19.4 |

| Credit card | 12.3 | 6.5 |

| Debit card | 31.6 | 19.1 |

| Direct debit | 11.0 | 23.3 |

| Single debit authority | 18.8 | 0.6 |

| Deduction at source | 6.7 | 14.5 |

| Service provider | 7.2 | 11.6 |

| Other | 12.4 | 5.0 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Sources: Author; Revenue (2021); Kennedy and Walsh (2016).

Given the self-assessed nature of LPT, regular monitoring and compliance checks are undertaken by the tax collection agency. According to Revenue’s latest analysis, over 90% of owners’ valuations are the same as or one band higher or lower than the Revenue guidance. Revenue uses its powers to challenge returns in cases of sizeable deviation from the ‘Revenue estimate’. For example, in the first 12 months of the LPT, 3,900 liable persons had corrected their property valuation bands upwards. By August 2022, just over 22,000 valuations had been increased, arising from a combination of self-correction and Revenue challenges. In 2021, Revenue published an analysis of valuations, comparing the average LPT valuations by property owners to average sales prices available from the national statistical office, and the national Residential Property Price Index. According to Revenue:

The analysis shows clearly that the LPT valuations by property owners track very closely to the prevailing average sales. In the vast majority of Local Authority areas, the Sales Price average falls within the average LPT band. Where they are not the same, the differences are marginal … This gives confidence that property owners filing their LPT returns have overall made reasonable and honest efforts to determine the appropriate valuation band for their property (Revenue 2021, p. 6).

Other lessons

McCluskey and Woods (2010) outlined a number of lessons based on the experience of residential property tax reform undertaken in Northern Ireland in the 2000s. Although the lessons learned were for a very different model of residential property tax, based on discrete capital values and a central valuation agency, they are still worth repeating here as some are relevant both in Ireland and beyond. They include the need for political buy-in and leadership, the importance of public consultation, the role of external inputs, and the importance of taxpayer notification (McCluskey and Woods 2010, p. 25).

Closer to home, in the early days of the LPT Revenue identified a number of lessons of its own from its experience with the new tax. In 2013, at an International Tax Dialogue Conference on tax and intergovernmental relations, the chairperson of Revenue addressed the administration and implementation of the LPT and listed the following lessons: political engagement is required; IT capability is essential; communication and leadership are needed; vested interests should not be underestimated; not all dimensions will be understood; and things will go wrong (Feehily 2013). Later, in a 2016 book chapter on the design and implementation of a new tax, two senior officers of Revenue involved in the LPT and in modelling property valuations identified three lessons, particularly for collection and enforcement. They were (1) keep it simple; (2) do not ignore the letter from Revenue; and (3) make it easy to pay, hard to avoid (Kennedy and Walsh 2016, pp. 14–15). Two further generic lessons from the Republic of Ireland’s experience are outlined below.

In property tax, and taxation in general, there is a common preference for a broad-based, low-rate tax regime. A broad tax base combined with a low tax rate is considered optimal in terms of its impact on the economy and the behaviour of taxpayers. These are indeed features of the Irish LPT, where exemptions and deferrals are few (and reduced in the 2021 revaluation) and the basic rate (equal to 0.18% before its reduction to 0.1029% in 2021) is very low by international standards. Although the revenue amounts are relatively small, in the Irish case this can be justified firstly by the limited role of local government and the relatively few public services assigned to and delivered by local authorities in Ireland, and secondly by the need to make the new property tax palatable to property owners and LPT payers. The lesson here for other countries is the appeal of a broad-based, low-rate regime at a rate acceptable to taxpayers (and public representatives), appropriate to the level of expenditure functions assigned to local government, and consistent with local fiscal discipline.

Another reason for the success of Ireland’s LPT, and a potential lesson for other jurisdictions reforming property tax, is the simplicity of the system. The LPT is relatively straightforward not only in design, but also in filing and compliance. Although the 2021 revaluation did cause some confusion among taxpayers, the LPT continues to meet the simplicity criteria of any good taxation system, and so helps to ensure high levels of compliance. Related to simplicity is the importance of speed. As evident in Table 4, the time between the publication of the Inter-Departmental Group report and the first LPT payment due was tight, just 12 months, but target dates were met without delay. This was made possible by a number of factors, including both the simple design and the tailored approach. Complexities in property tax systems elsewhere (for example different property classes, differential rates, multiple bases, various reliefs) are generally absent in the LPT, making for a property tax system that taxpayers can understand and tolerate.

Conclusion

When writing about property tax reform, Rosengard (2013, p. 174) noted that “leaders seldom have the opportunity to design property tax with a blank slate”. However, Ireland’s new residential property tax was an exception. In addition to the opportunity to adopt international best practice in property tax design, the introduction of a new tax rather than the reform of an existing system meant that the usual distributional impacts with the inevitable winners and losers were absent – or at least not a constraint that might have stalled the process. As for other trade-offs involved in property tax reform, an emphasis or preference in the Irish case for a revenue mobilisation measure over one aimed at housing activation, for speed over accuracy, for simplicity over sophistication, for collection over valuation, and for voluntary compliance over punitive sanctions, combined to produce a residential property tax that is generally accepted by both politicians and taxpayers.

Acknowledging the importance of the local context when designing a property tax combined with the political economy of property tax reform, Voltaire’s 18th-century quotation, ‘La perfection est l’ennemi du bien,’ or in English, ‘perfection is the enemy of the good,’ neatly captures the potential lessons from Ireland’s 21st-century tax design. Although the LPT is not perfect, and has some ‘second-best’ features, it is now, as Kennedy and Walsh (2016, p. 14) write, “part of the normal business of Revenue and of property owners”.19 Further evidence for this is provided by the 2021 property revaluations, a reform that countries including Britain and some central European states (Austria, Belgium and Germany, for example) have failed to undertake, at least to date (Slack 2022). Careful consideration of both the economic and political aspects of property tax is necessary for reform to succeed. Ireland’s new residential property tax is a good example of this, and provides lessons for other jurisdictions to learn.

Acknowledgements

My thanks to Enid Slack, Almos Tassonyi, Jerry Grad, Greg Martino, Aidan Carter, Lauren Birch, Keith Walsh, Katie Clair, Stephen McNena, participants at a seminar at the University of Toronto in May 2022, and delegates at the annual Conference of Valuation Agencies at the University of Oxford in December 2022, for their insights on property taxes.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

Ahmad, E., Brosio, G. and Jiménez, J.P. (2019) Options for retooling property taxation in Latin America. VIII Jornadas Iberoamericanas de Financiación Local, Ciudad de Mexico, October 1–2.

Almy, R. (2013) A global compendium and meta-analysis of property tax systems. Cambridge, Mass: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

Almy, R. (2014) Valuation and assessment of immovable property. Working Paper on Fiscal Federalism No.19. Paris: OECD.

Bird, R.M. (2001) Subnational revenues: realities and prospects. Working Paper. Washington DC: World Bank.

Bird, R.M. (2006) Local and regional revenues: realities and prospects. In: Bird, R.M. and Vaillancourt, F. (eds.) Perspectives on fiscal federalism, (pp. 177–196).Washington DC: World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-0-8213-6555-7

Callanan, M. (2018) Local government in the Republic of Ireland. Dublin: Institute of Public Administration.

Collier, P., Glaeser, E., Venables, T., Blake, M. and Manwaring, P. (2018) Land and property taxes for municipal finance. IGC Cities that Work Policy Paper. London: LSE.

Commission on Taxation. (2009) Commission on taxation report 2009. Dublin: Government of Ireland.

Commission on Taxation and Welfare. (2022) Foundations for the future. Report of the commission on taxation and welfare. Dublin: Government of Ireland. Available at: https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/7fbeb-report-of-the-commission/#foundations-for-the-future-report-of-the-commission-on-taxation-and-welfare

Feehily, J. (2013) The introduction of local property tax in Ireland. Presentation at the ITD Conference on Tax and Intergovernmental Relations, Morocco, December 3–5.

Franzsen, R. and McCluskey, W. (2005) An explanatory overview of property taxation in the Commonwealth of Nations. Working Paper. Cambridge, Mass: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

George, H. (1879) Progress and poverty. An inquiry into the cause of industrial depressions and of increase of want with increase of wealth: the remedy. New York: Robert Schalkenbach Foundation.

Government of Ireland. (2012) Finance (Local Property Tax) Act, 2012. Dublin: The Stationery Office.

Government of Ireland. (2014) Local Government Reform Act, 2014. Dublin: The Stationery Office.

Government of Ireland. (2021) Finance (Local Property Tax) (Amendment) Act, 2021. Dublin: The Stationery Office.

International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2013) Taxing times. World Economic and Financial Surveys, Fiscal Monitor. Washington DC: IMF.

Inter-Departmental Group. (2012) Design of a local property tax. Dublin: Government of Ireland.

Kennedy, J. and Walsh, K. (2016) The local property tax – a case study in designing and implementing a new tax. In: Tobin, G. and O’ Brien, C. (eds.) Irish tax policy in perspective, (pp. 173–190). Dublin: Irish Tax Institute.

McCluskey, W. and Woods, N.D. (2010) Property tax reform: the Northern Ireland experience. Working Paper. Cambridge, Mass: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

Mirrlees Review. (2011) Tax by design. Chapter 16. The taxation of land and property. London: Institute for Fiscal Studies.

Musgrave, R.A. (1983) Who should tax, where, and what? In: McLure, C.E. Jr. (ed.) Tax assignment in federal countries, (pp. 2–19).Canberra: Australian National University, Centre for Research on Federal Financial Relations.

Norregaard, J. (2013) Taxing immovable property – revenue potential and implementation challenges. Working Paper WP/13/129. Washington DC: IMF. https://doi.org/10.5089/9781484369050.001

Oates, W.E. (1972) Fiscal federalism. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Oates, W.E. (2010) Local government. An economic perspective. In: Bell, M.E., Brunori, D. and Youngman, J. (eds.) The property tax and local autonomy, (pp. 9–26). Cambridge, Mass: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

OECD. (2021) Making property tax reform happen in China. A review of property tax design and reform experiences in OECD countries. Fiscal Federalism Studies. Paris: OECD.

O’Leary, J. (2018) How (not) to do public policy: water charges and local property tax. Galway: Whitaker Institute, National University of Ireland Galway. Available at http://whitakerinstitute.ie/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/NUIG-Whitaker-Report-Water-Charges-LPT-Final.pdf

Olson. M., Jr. (1969) The principle of ‘fiscal equivalence’: the division of responsibilities among different levels of government. American Economic Review, 59 (2), 479–487.

Plimmer, F., McCluskey, W., and Connellan, O. (2002) Valuation banding – an international property tax solution? Journal of Property Investment & Finance, 20 (1), 68–83. https://doi.org/10.1108/14635780210416273

Revenue. (2021) LPT statistics. Dublin: Revenue.

Revenue. (2022) Annual report 2021. Dublin: Revenue. Available at https://www.revenue.ie/en/corporate/press-office/annual-report/2021/ar-2021.pdf

Rosengard. J.K. (2013) The tax everyone loves to hate: principles of property tax reform. In: McCluskey, W., Cornia, G.C. and Walters, L.C. (eds.) A primer on property tax: administration and policy, (pp. 173–186). Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118454343.ch7

Sansom, G. (2020) Recent trends in Australian local government reform. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, (23), ID 7546. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi23.7546.

Slack, E. (2015) How to reform the property tax: lessons from around the world. IMFG Papers No. 21. Toronto: Institute on Municipal Finance and Governance, University of Toronto.

Slack, E. (2022) The property tax in the real world. Canadian Tax Journal, 70 (supp), 1–26.

Thornhill, D. (2015) Review of the local property tax (LPT). Report for the Minister of Finance published as part of Budget 2016. Dublin: Government of Ireland.

Tiebout, C. (1956) A pure theory of local expenditures. Journal of Political Economy, 64 (5), 416–424. https://doi.org/10.1086/257839

Turley, G. (2022) The old and the new: a tale of two local property taxes in Ireland. IMFG Papers No.62, Toronto: Institute on Municipal Finance and Governance, University of Toronto.

Turley, G. and McNena, S. (2019) Local government funding in Ireland: contemporary issues and future challenges. Administration, 67 (4), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.2478/admin-2019-0024

UN-HABITAT. (2011) Land and property tax: a policy guide. Nairobi, Kenya: United Nations Human Settlements Programme. Available at: https://unhabitat.org/land-and-property-tax

Walsh, K. (2013) Property valuation. Developing, assessing and deploying a valuation model for local property tax. Dublin: Revenue.

1 Here we are referring to revenue budgets, and the funding of so-called current, recurring, operating or day-to-day expenditures. Capital budgets and their revenue sources are not discussed in this paper.

2 This section draws heavily from Turley (2022).

3 More formally, the four pillars are expenditure assignment, tax assignment, intergovernmental transfers, and borrowing and debt.

4 The International Monetary Fund (IMF) in its October 2013 Fiscal Monitor Taxing Times report concluded that “there is a strong case in most countries, advanced or developing, for raising substantially more from property taxes” (IMF 2013, p. viii). Ireland’s new residential property tax was introduced in the same year, with the support of the IMF as outlined later in this paper.

5 In supporting property tax but acknowledging that it is the tax that everyone loves to hate, Rosengard (2013, p. 173) describes property tax as “roughly progressive, loosely correlated with local government benefits [and] a relatively good proxy for a tax on multi-year income”.

6 Although there is considerable variation in the degree to which countries around the world levy revenues from property taxes, the yield is modest in most countries (Nooregaard 2013; Slack 2022).

7 Water services were reassigned from the local authorities to a national utility (Irish Water) in 2014. Although Irish Water is now primarily responsible for water services, there are service level agreements in place between the local authorities and the utility company so that the local authorities continue to act as its agents.

8 For more details on the funding of local government in Ireland, see Turley and McNena (2019). For a discussion on the non-residential property tax, see Turley (2022).

9 Not only is there a different regime for non-residential properties, but unlike many other property tax systems elsewhere there are no other property classes. Two distinct property tax regimes (rates and the LPT) rather than a single, integrated property tax, combined with no property classes, makes Ireland’s property tax rather unusual by international ‘norms’. It does, however, resemble the British system where residential properties are subject to ‘council tax’ whereas ‘business rates’ are levied on non-residential properties.

10 Initially envisaged as a site value tax (SVT), after careful consideration the Inter-Departmental Group recommended against an SVT, on the basis of the “likely difficulties in ensuring acceptance by taxpayers, i.e., arriving at values that are evidence-based, understandable and acceptable to the public, in addition to the complexities and uncertainties in the valuation effort necessary to put a SVT in place” (Inter-Departmental Group 2012, pp. 36–37). More generally, Almy (2014, p. 8) adds that the “empirical evidence of the efficacy of land taxes in spurring optimal land use is limited at best”.

11 An earlier report by the Commission on Taxation included many of the same recommendations (Commission on Taxation 2009). A decade on from its introduction, the 2022 Commission on Taxation and Welfare (p. 359) concluded that the “LPT system currently in place, while not perfect, achieves many of the policy objectives sought, represents a fair approach to raising taxes from residential property and is generally well-understood by the public”.

12 For more technical details of the actual Revenue valuation model used and the computer assisted mass appraisal (CAMA) approach, see Walsh (2013). Here we include the final statement from the paper, as a validation of the methodology employed. It says: “The model and the average valuations produced are good guides for the vast majority of properties, particularly in the context of the requirement of LPT for property owners only to assess the correct valuation band, not the precise value, of their property.” (Walsh 2013, p. 22)

13 A very large majority (over 75%) of the 2013 returns were in the first three bands (with the average liable property in band two), resulting from liable persons valuing their property at less than €200,000. Initial reports on the 2021 returns show a not-too-dissimilar breakdown. Even though there has been a big increase in average property prices since 2013, this is explained by the widening of the valuation bands with the result that the upper limit of band three is now €350,000.

14 The most famous version of land value taxation was espoused by Henry George in his 1879 classic Progress and Poverty, when he advocated replacing all taxes with a single tax, namely a land value tax (George 1879). For more on property tax and especially land tax in developing countries, including some member states of the Commonwealth where property taxes are often the largest source of untapped municipal revenues, see Collier et al. (2018).

15 Although self-assessment is not widely used for property tax, it has been adopted in Canada and elsewhere for taxing vacant property (including for Ireland’s new Vacant Homes Tax due in 2023). In these cases it is the responsibility of the property owner to declare if a property is vacant, and liable for vacancy tax.

16 Although Slack (2015, p. 20) also describes banding and self-assessment as “less promising approaches”, that is in the context of strategies for reform of existing property tax systems, rather than the building of a property tax from scratch as was the case in Ireland.

17 As Kennedy and Walsh (2016, p. 3) write: “… design must take account of implementation issues and implementation needs good design to be effective”.

18 For example, approximately 50,000 mandatory deductions from wages/pensions per annum were made in the first three years of the LPT.

19 In explaining the success of the LPT (as against the failed attempt to introduce household water charges) and the wider policy-making process, O’Leary (2018, p. 86) describes it as “characterised as lacking in intellectual purity, but […] a process that produced a workable solution”. O’Leary (2018) is only one of many reviews of the LPT, details of which can be found in section 7 of Turley (2022).