Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance

Issue 27

December 2022

COMMENTARY

Decentralisation, Revenue and the Capital City: The Case of Kampala, Uganda

Infrastructure Institute, School of Cities, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada, and, Department of Economics, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

Corresponding author: Astrid Haas, Infrastructure Institute, School of Cities, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada, and, Department of Economics, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa, astridrnhaas@gmail.com

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi27.8445

Article History: Received 16/10/2021; Accepted 05/11/2022; Published 20/12/2022

Citation: Haas, A. 2022. Decentralisation, Revenue and the Capital City: The Case of Kampala, Uganda. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, 27, 158–169. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi27.8445

© 2022 by the author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercial, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Abstract

This commentary examines the demise in 2010 of the Kampala City Council, and the factors that led to its replacement by the Kampala Capital City Authority (KCCA). It outlines some of the different institutional arrangements associated with the establishment of KCCA and resulting changes in the overall management of the city, the outcomes of those changes, and the implications for Uganda’s decentralisation processes, as analysed through the specific lens of the city’s revenues. Finally, it discusses how many of these reforms may be, perhaps necessarily, short-lived as a result of the tensions they created.

Keywords

Urbanisation; Kampala; Decentralisation; Local Revenue

Introduction

Uganda has undergone what has been characterised as one of the most radical and ambitious decentralisation reforms in Africa (Asiimwe and Musisi 2007). In addition to fostering economic growth and development, decentralisation was intended to play an additional critical role as a path to national unity after decades of brutal dictatorships and civil conflict. The top-down reform process pursued by President Museveni and his National Resistance Movement (NRM) party began when he came to power in 1986. It included, amongst other factors, local empowerment (Bird and Ebel 2007), enabling grassroots participatory democracy (Kauzya 2007) and consolidating the overall, but fragile, peace (Eaton and Connerley 2010).

This transfer of decision-making authority and functional responsibilities, as well as revenue collection, to local governments was specifically enshrined in Uganda’s Constitution (1995). The Constitution stipulates more generally that the central government is responsible for regulation and policy-setting across all sectors, as well as having the exclusive remit over foreign, immigration and monetary policy. Conversely, local governments are responsible for the direct provision of local infrastructure and public services. Thus, through its comprehensive reform programme the Ugandan government concurrently devolved political, administrative and fiscal responsibilities to local levels of government, although arguably the impetus for each set of reforms differed slightly.

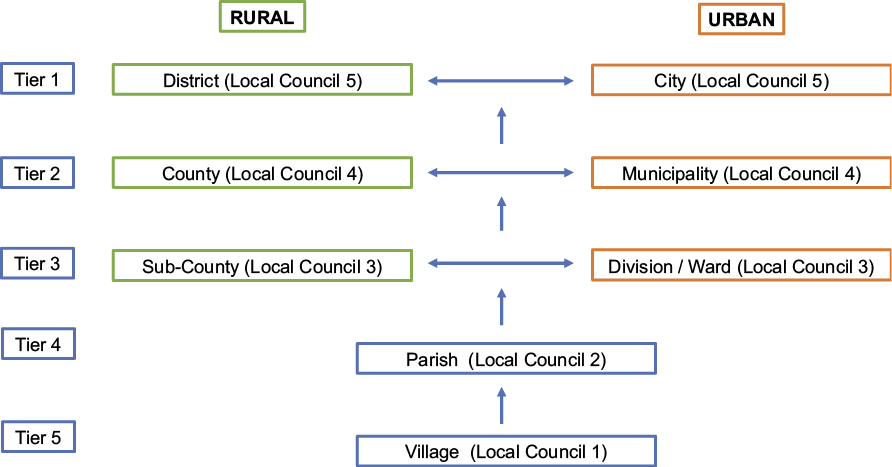

Administrative decentralisation was undertaken with the explicit aim to bring service delivery closer to the people and, through this, to foster economic growth, development and poverty reduction. In addition, following the civil war between 1980 and 1986, the government’s lack of resources and growing debt burden meant that, from a central level, it was not able to adequately provide services across the country. To enable administrative decentralisation, a five-tier structure (see Figure 1) was set up that directly reflected the revolutionary structures, the so-called Resistance Councils, established during the war for local governance purposes (Green 2015). Following the ascent to power of Museveni in 1986 – first as rebel commander and then as president – the Resistance Councils were transformed into the local councils that still exist as the administrative structures for service delivery across Uganda’s 136 districts. Until 2010 this system included the capital city, Kampala.

Figure 1. Uganda’s five-tier local governance structure

Fiscal decentralisation arrangements are also embedded in the Constitution, but their subsequent operationalisation, particularly through the Local Government Act 1997, was in part dictated by conditions imposed by the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF) under their Structural Adjustment Programme (Cheema and Rondinelli 2007). Uganda, like several other developing countries at the time, was required to undertake neo-liberal economic reforms to qualify for assistance from international financial institutions. Fiscal decentralisation was therefore enshrined in the Local Government Act 1997, which still governs revenue generation in Kampala today. The Act details specific, and relatively extensive, provisions for own-source revenue generation for local governments. In addition, the Constitution mandates a system of unconditional and conditional inter-governmental fiscal transfers to support local governments.

Political decentralisation, as noted, was seen as a means to foster peace through encouraging national unity by creating forums where every citizen could have a say in the future direction of their country. From the outset, there was a commitment for direct election of representatives to all tiers of local government every five years. Importantly, to strengthen the voice of otherwise marginalised groups, the Constitution mandated a specific proportion of elected positions for women, youth, and persons with disabilities (Devas and Grant 2003; Kauzya 2007).

There were some initial successes across all the three spheres of decentralisation, notably in encouraging local participation, an important element of democratic governance. This was illustrated by the substantial voter turnout in the initial local council elections (Mutibwa 1992; Golooba-Mutebi 1999). However, these early advances were significantly reversed over time, particularly with the move from a one-party state to national multi-party elections at all levels of government in 2005. This resulted in heightened political contestation, especially in urban areas, and a degree of recentralisation of power.

An indisputable example of this recentralisation was the creation of the Kampala Capital City Authority (KCCA) in 2010. This new institutional structure weakened accountability of the leadership in Uganda’s capital and biggest city towards its electorate – but to some observers the reforms were necessary to institute much-needed changes to unlock Kampala’s economic productivity. To others, however, it has meant that Kampala has become an increasingly undemocratic space where decisions are taken that do not reflect the needs or preferences of the average citizen.

The demise of Kampala City Council

Kampala is the capital city of Uganda and the main seat of government. As a primate city, a circumstance very typical among African Commonwealth countries, its urban population is disproportionately larger than any other place in Uganda (Ades and Glaeser 1994). It is estimated that Kampala currently has a resident population of about 1,68,600 people, around 4% of Uganda’s population (Uganda Bureau of Statistics 2020). With a population growth rate of 5.2%, Kampala is expected to reach the status of a ‘mega-city’, ie a city with a population of over 10 million, by the year 2040 (Government of Uganda 2012).

Administratively, until July 2020 Kampala was the only legally designated city in Uganda, and before the KCCA Act 2010 came into force in 2011 it was treated similarly to other urban local councils (ie the city councils shown in Figure 1) and governed under the Local Government Act 1997. Kampala City Council (KCC) was headed by an elected mayor and local council members were elected by, and therefore accountable to, the city’s citizens. The KCC was responsible for overall decision-making and implementation of local infrastructure and service provision. In fact, 80% of all local services were devolved to the council. This included all services except for national roads, and secondary and tertiary education. The KCC was empowered by the provisions in the Constitution and supporting legislation to handle its own affairs and thus, legislatively, it had ample scope to raise own-source revenues.

Translating these provisions into practice did, however, result in significant challenges. For example, KCC’s own-source revenue was curtailed because a large portion of the population worked in the informal sector, from which it is difficult to generate tax revenue. According to an International Labor Organization study, during the 1990s 83.7% of employment across Uganda was in the informal sector, which in turn accounted for 43.1% of GNP (Schneider 2002).

Then, in 2005, two directives by the President placed even greater constraints on KCC’s, and other local governments’, revenue-raising powers. The first was the abolition of the ‘graduated tax’, which until then was one of the KCC’s most important sources of own-source revenue (Byaruhanga 2011). The graduated tax, a form of local income tax, had existed since Uganda’s independence, when it replaced the colonial ‘hut tax’. Although the tax and its administration were fraught with challenges, it was an important means for KCC to derive some tax income from the large informal economy (Livingston and Charlton 1998). The second directive was a blanket exemption on owner-occupied residences with respect to property tax payments. This meant that suddenly most residential buildings, which formed most of the property roll, fell out of the tax net. Both these provisions were evidently political moves to garner popular support for the President and his NRM party in the lead-up to the country’s first multi-party elections, held in 2006.

But the KCC’s restrictions on own-source revenue also had other implications – particularly with respect to the council’s ability to borrow to finance investments, as there is a provision in the Local Government Act 1997 that local governments are only allowed to borrow up to 25% of the value of their own-source revenue. Given the negligible amounts of tax being collected, KCC was never able to go to the market to borrow. Additionally, because Kampala was generating a large proportion of GDP and revenue for Uganda as a whole, it did not receive sufficient intergovernmental transfers from the national treasury to cover the shortfall in the council’s funding.

The KCC therefore remained chronically underfunded. Coupled with significant governance challenges, which included high levels of corruption and successive, seemingly arbitrary interventions by the President and national government, it struggled to provide the necessary local infrastructure and services for a rapidly growing urban population. As a result, Kampala became notorious as a place mired in crime, congestion, corruption and growing poverty and inequality.

The KCCA Act: the recentralisation of Kampala

Prior to 2005, Uganda was officially a one-party ‘democratic’ system. However, when it transitioned constitutionally to a multi-party system, opposition political parties started to form and quickly gain traction, particularly in urban areas and, most significantly, in Kampala (Goodfellow and Titeca 2012). As with many cities across the world, Kampala is a highly politicised urban setting, and this atmosphere was arguably heightened by the introduction of political decentralisation reforms which opened contested spaces to new actors, both state and non-state, to compete for both economic and political power. When multi-party elections were conducted, the NRM lost significant ground in Kampala, which was then, and at every election since, comfortably won by the opposition parties.

Kampala’s strong association with opposition has shaped the President’s handling of the city, which has been driven by two main factors. On the one hand, its dysfunction arguably worked in the NRM’s favour as the party has used this to emphasise the inability of the opposition to manage the city. This has, at times, led the President to ignore Kampala overall and rather focus his efforts, and patronage, on his strong rural base. On the other hand, Kampala is the economic core of Uganda, including the site of 80% of the country’s overall industrial activity, and contributing 50–60% of Uganda’s GDP (Delbridge et al. 2022). As such its dysfunction has had wider and consequential effects, hampering the overall economic growth of the country. During KCC’s time, these competing pressures of being a centre of increasing political opposition, yet at the same time being the much-needed economic engine for development, led to a haphazard approach with respect to the management of Kampala and the President’s interventions into its affairs. However finally, and arguably in an effort to stem the loss of political control, the President started a drive towards recentralisation to re-consolidate his power (Tripp 2010; Gubser 2011; Lambright 2011; Lewis 2014). In Kampala, this culminated in the passing of the Kampala Capital City Act (‘KCCA Act’) in 2010.

KCC’s dysfunction provided the President with a formal reason to recentralise the city’s institutional structures, which he officially did on the basis that it was not delivering on its service delivery mandate. The new arrangements, outlined in the KCCA Act, gave Kampala special status as a capital city and, on paper, more power to manage its affairs. In practice, however, the Act brought Kampala more firmly within the President’s ambit. For example, as the KCCA was now an authority, structurally it had to be placed under the remit of a ministry. Instead of placing it under an existing ministry, however, the Act created a new ministry, the Ministry of Kampala and Metropolitan Affairs (MoKMA), which was in turn placed directly under the Office of the President. Moreover, the KCCA Act created a new top-level city leadership position of Executive Director, a role which is largely independent of the elected political arm of the Authority and has full technocratic and managerial power over running Kampala. Although this postholder officially reports to the Minister of MoKMA, their appointment as well as their dismissal, as per the Act, is in the hands of the President. The parallel political leader of the authority remained the popularly elected Lord Mayor, but the KCCA Act significantly curtailed his or her powers. As a result, the person directly accountable to the populace of Kampala effectively became more of a ceremonial figure rather than being actively involved in the day-to-day running of the city’s affairs.

Increasing own-source revenue collection

The establishment of KCCA did result in initial successes in improving the management and delivery of services and infrastructure in Kampala. More specifically, when Dr Jennifer Musisi was appointed the first Executive Director of Kampala, she of course had the full support and backing of the President. This allowed her to undertake relatively radical reforms, which might otherwise not have been possible, to clean up the ailing governance situation within the city and, rapidly, institute new policies and procedures for enhancing service delivery. One of her areas of focus, as well as her notable success, was with respect to how the city managed to transform and improve its own-source revenue collection.

Some of the reforms that were instituted under her auspices could also be implemented by many other local governments across Uganda, given the right capacity and political will, as they lie within their own powers (Andema and Haas 2017; Delbridge et al. 2022). Examples include fully digitising the tax registration system by developing KCCA’s in-house, city-wide system called ‘e-Citie’. Through this system, each taxpayer in Kampala was provided with their own individual tax identification number, which enabled the KCCA to track their payments and monitor any non-compliance. It also helped reduce errors associated with the manual administration system. Other reforms were simply to reduce corruption and associated revenue leakages. For example, when Dr Musisi took office, she discovered that the KCCA had 151 bank accounts, the majority of which were beyond her oversight. These were streamlined into eight accounts over which the Executive Director had full control.

There was also an organisation-wide shift in terms of how taxpayers were viewed and therefore treated: rather than seeing them as, by default, wanting to avoid paying taxes, this was reframed as seeing the taxpayer as a client to whom the KCCA was providing a service. This meant that systems were changed to make it easier for taxpayers to pay their dues, and through this the KCCA increased voluntary compliance. For example, revenue centres were decentralised to make payment more accessible and payment methods were automated and diversified, such as including the option of mobile money payments using phones. Efforts were made to undertake wide-ranging stakeholder consultations to ensure that the KCCA was meeting the taxpayers’ needs.

There were other important reforms, however, that could only be undertaken given the fact that KCCA had special status, including some that were only possible with Presidential support. For example, one of the important institutional changes implemented with the advent of the KCCA was the creation of a revenue directorate as a separate entity from the city’s treasury (Kopanyi 2015; Delbridge et al. 2022). This meant that the directorate’s staff could focus solely on raising revenues. An associated reform, again only possible with the backing of the President, was that the staff chosen both to fill the newly created directorate and roles at KCCA more broadly were able to be recruited outside the conventional, and usually legally mandated, mechanism of the Ministry of Public Service, which normally assigns all civil servants to their posts. In KCCA’s case Dr Musisi received special permission from the President to appoint her own staff, which she did primarily by drawing on highly qualified staff from the Uganda Revenue Authority and Ministry of Finance, amongst others (Kopanyi 2015). Furthermore, the KCCA was exempted from the official government pay structures and allowed to pay significantly higher salaries than those for similar civil servant posts, with the objective of incentivising good performance. In this way the KCCA became the second highest paying government institution. All of this contributed to the impacts seen in revenue collection, which as one researcher notes led to the Directorate of Revenue Collection having “…capacities and procedures today [that] are comparable to capacities and procedures of revenue administrations in developed countries” (Kopanyi 2015, p. 6).

As a result of these reforms, between the fiscal years 2011–12 and 2014–15, own-source revenues increased by over 100% to over USD25 million (Kopanyi 2015). In addition, there have been commensurate increases in transfers from the central government, and renewed enthusiasm for KCCA’s structures have meant that development partners have shown increasing interest in financially contributing to the city. For example, in 2018–19 USD45.6 million of KCCA’s budget was coming from central government grants, and a further USD42.1 million from World Bank support (Delbridge et al. 2022). These increases in revenue coupled with the wider reforms undertaken during Dr Musisi’s time at KCCA also translated into improved local infrastructure and service delivery across the city. Amongst other examples, since the establishment of KCCA 210 km of city roads have been upgraded and a further 54.1 km have been constructed; two local referral hospitals were constructed and operationalised; and infrastructure was upgraded in the 79 city-run primary schools.

It is important to note, however, that even with the passing of the KCCA Act, the ability of KCCA to generate further revenue was still curtailed by the fact that, in most respects, it continued to be treated like a local government, as per the Local Government Act 1997. This had the greatest impact with respect to borrowing. As a result of all the financial management reforms Dr Musisi and her team undertook, including the aforementioned ones with respect to own-source revenue generation, in 2015 KCCA was able to obtain an investment-grade local credit rating (Global Credit Rating 2015). However, it was still subjected to the 25% borrowing cap and therefore, until today, has not been able to borrow from capital markets or float a municipal bond. This cuts across fiscal decentralisation.

Tensions: increased service delivery vs decreased accountability

Although the visible transformation of both the KCCA as an institution and Kampala as a city received many accolades, both nationally and internationally, there were also notable dissenting voices. These focused especially on the manner in which the reforms were carried out. It was widely known that the Executive Director, Dr Musisi, and the populist Lord Mayor, Erias Lukwago, clashed on many aspects of the direction of the reforms in Kampala. Arguably, Dr Musisi was only able to push through her reform agenda as quickly and as comprehensively as she did once the Lord Mayor was impeached in 2013 (he was found guilty by a government tribunal of inciting the public not to pay KCCA’s taxes). This rendered an already weakened political wing of the KCCA nearly wholly ineffective, which in turn practically removed any direct accountability of the government to the electorate. Many therefore argue that the establishment of the KCCA severely weakened the link between service provision and accountability, and that the reforms did not reflect what the average citizen of Kampala wanted or needed (Madinah et al. 2015). Yet at the same time, as highlighted in this paper, the KCCA was engaging the citizenry directly in other ways, and especially with respect to tax collection, which in some ways may reflect a contradictory approach with respect to the broader social contract.

Additionally, the parallel lines of responsibility enshrined in the KCCA Act, through separate technical and political wings, have not only led to effectively three leaders of the city (the Executive Director, the Lord Mayor, and the Minister of MoKMA – as well as, arguably, the President) but have also further blurred the lines of accountability to citizens. An amendment to the KCCA Act, signed into law in 2022, tried to streamline some of the responsibilities between the different actors, but it has not satisfactorily resolved the issue of accountability to citizens. The Executive Director remains the most powerful decision-maker in KCCA and is accountable to the Minister of MoKMA, and through them to the President; whilst the elected Lord Mayor continues to have a secondary role with respect to the running of the city.

Furthermore, the President continues to intervene in haphazard yet significant ways in KCCA’s affairs, including when it comes to raising revenue. This matches his increasing tendency towards personalised political rule, a situation in which “the connection between leader and followers is based mostly on direct, quasi-personal contact, not on organizational intermediation” (Weyland, 2001, p. 13). A recent example was the President’s intervention on behalf of the owners of ‘taxis’ (in this context, 14-seater minibuses) who were complaining about the hike in fees they pay the KCCA for operating within the city’s boundaries. They complained directly to the President who subsequently issued a directive that mandated a reduction in fees, which again severely impacted an important revenue source for the KCCA. This follows a similar pattern to the President’s other interventions on behalf of important urban voter bases, in order to increase his political support in the city (Goodfellow and Titeca 2012). Such Presidential directives, which are becoming increasingly frequent, further widen disparities between legal provisions with respect to decentralisation and their de facto implementation.

Further recentralisation

When Uganda held an election in 2015, it was the first time that the President’s NRM party lost all parliamentary seats in Kampala to the opposition. This was a major blow to the President’s ambitions as well as his intended vision behind the creation of KCCA, which was predicated on improving service provision to the extent that it would regain votes for the NRM in the most densely populated area of Uganda. In addition, the same Lord Mayor was re-elected, despite his impeachment in 2013, albeit this time as an independent candidate. Given his discontent with how the city was being run, coupled with his brief removal from power, he re-emerged on an even stronger populist platform. This was founded on strong opposition to what he termed an autocratic approach to the reforms being undertaken by the KCCA, rendering him even more hostile to the Executive Director’s undertakings. The President outwardly blamed the poor election results on what he termed the Executive Director’s ‘heavy-handed’ approach to managing the city. As a result, his support for subsequent reforms waned significantly, leading to a hiatus in further progress. This culminated with the very public resignation of Dr Musisi in 2018, through a letter shared with the media, that not only outlined all the successes the Authority achieved under her tenure, but also highlighted that she no longer felt able to carry out reforms for want of political support.

Compounding these challenges has been the further recentralisation of fiscal structures since the passing of the Public Financial Management Act 2015. Although this Act had the aim of strengthening accountability and transparency in expenditure management, it has effectively reversed fiscal decentralisation (Mushemeza 2019) by removing local governments’ (including KCCA’s) control over their own-source revenue. Anything collected at a local level must now be remitted to a single treasury account administered by the Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development (MoFPED). To retrieve these funds, local governments and the KCCA must submit their requests for approval of expenditure to MoFPED. This has not only removed fiscal authority and autonomy from KCCA, but it also further undermines transparency and accountability, as well as reducing the incentive for KCCA to increase local revenue collection when it lacks control over how these funds are spent. Although the provisions in the Public Financial Management Act conflict with those in the Local Government Act 1997, MoFPED has argued that the former takes precedence precisely because the majority of local government budgets are centrally funded and as such, need to be centrally administered (Mushemeza 2019).

A positive or negative move for Kampala?

The initial years of the KCCA have starkly split opinion. There are many who felt that the period from 2011, when the Authority was first inaugurated, until Dr Musisi’s resignation in 2018, were Kampala’s heyday when the city finally seemed to be on a positive development trajectory. There were visible changes to city’s infrastructure and service delivery and, as highlighted above, notable changes in systems and processes that reduced corruption, increased transparency, and raised overall revenue collection. They argue that in the case of a city like Kampala, which is urbanising at such a fast rate, and where investments need to be made now to avoid the challenges of retrofitting in the future, urban governance structures that are more centralised, and thus allow for quicker decision-making, are more suitable given that the alternative options will move too slowly.

There are, however, others who feel that the changes made, including for example improvements to roads, disproportionately benefited the upper and middle classes in Kampala, and that most of the population, the low-income earners, were neglected by Dr Musisi’s reforms. Those opposed to the KCCA’s approach further point to policies that were suggested, and in some case implemented, to ‘clean up the city’, including frequent arrests of informal street vendors in an effort to get them to move to more organised, dedicated marketplaces, as well as periodic threats to ban boda-bodas (motorbike taxis) from the city. Protecting the interests of the ‘ordinary Kampala citizen’ was the platform on which the Lord Mayor ran, and continues to run, his very successful campaigns.

Decentralisation has by no means been a linear process in Uganda, but especially in recent years there have been significant reversals. Changes in incentives for the President and his ruling NRM party, with the advent of multi-party democracy in 2005, have seen a shift away from the initial positive steps towards empowering local levels of government to take decisions and making them more accountable to their citizens. As highlighted in this paper, the overall recentralisation is perhaps most evident in the case of Kampala, with the passing of the KCCA Act in 2010, which was adopted both to improve the management and service delivery in the city but, importantly, also to increase the President’s control over an opposition stronghold. It has produced successes, as in the case of own-source revenue collection, but it also has had significant drawbacks with respect to citizen accountability. Therefore, whether these institutional reforms will, on balance, positively impact the overall success of Kampala on its path to becoming a mega-city, still remains to be seen.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

Ades, A. and Glaeser, E. (1994) Trade and circuses: explaining urban giants. NBER Working Paper No. 4715, New York: National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). https://doi.org/10.3386/w4715

Andema, F. and Haas, A. (2017) Efficient and effective municipal tax administration: a case study of Kampala Capital City Authority. London: International Growth Centre.

Asiimwe, D. and Musisi, N. (2007) Decentralisation and the transformation of Uganda. Michigan: Fountain Book Publishers.

Bird, R.M. and Ebel, R.D. (2007) Chapter 1: Subsidiarity, solidarity and asymmetry: Aspects of the problem. In: Bird, R.M. and Ebel, R.D. (eds.) Fiscal fragmentation in decentralized countries: subsidiarity, solidarity and asymmetry, (pp. 3–25). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Byaruhanga, J. (2011) Impact of graduated tax suspension to local level service delivery in Uganda. BA dissertation, Uganda Christian University. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/4095912/Impact_of_Graduated_Tax_Suspension_to_Local_Level_Service_Delivery_in_Uganda

Cheema, G.S. and Rondinelli, D.A. (2007) Decentralizing governance: emerging concepts and practices. Washington DC: Brooking Institution Press.

Delbridge, V., Haas, A., Harmann, O. and Venables, T. (2022) Enhancing the financial position of cities: evidence from Kampala. Nairobi: UN-Habitat.

Devas, N. and Grant, U. (2003) Local government decision-making, citizen participation and local accountability: some evidence from Kenya and Uganda. Public Administration and Development, 23 (4), 307–316. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.281

Eaton, K. and Connerley, E. (2010) Chapter 1 Democracy, development and security as objectives of decentralization. In: Connerley, E., Eaton, K. and Smoke, P. (eds.) Making decentralization work: democracy, development and security, (pp. 1–24). Boulder CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781626373822-002

Global Credit Rating Co. (2015) Kampala Capital City Authority. Available at: http://www.kcca.go.ug/uDocs/KCCA%20credit%20rating%20report.pdf

Government of Uganda. (1995) Constitution of the Republic of Uganda 1995. Kampala: Uganda Printing and Publishing Corporation

Government of Uganda. (1997) Local Government Act 1997. Kampala: Uganda Printing and Publishing Corporation

Government of Uganda. (2010) The Kampala Capital City Act 2010. Kampala: Uganda Printing and Publishing Corporation.

Government of Uganda. (2012) Kampala Physical Development Plan 2012. Kampala: Kampala Capital City Authority.

Government of Uganda. (2015) Public Financial Management Act 2015. Kampala: Uganda Printing and Publishing Corporation

Golooba-Mutebi, F. (1999) Decentralisation, democracy and development administration in Uganda, 1986-1996: limits to popular participation. PhD thesis, London School of Economics, London.

Goodfellow, T. and Titeca, K. (2012) Presidential intervention and the changing ‘politics of survival’ in Kampala’s informal economy. Cities, 29 (24), 264–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2012.02.004

Green, E. (2015) Decentralization and development in contemporary Uganda. Regional and Federal Studies, 25 (5), 491–505. https://doi.org/10.1080/13597566.2015.1114925

Gubser, M. (2011) The view from Le Château: USAID’s recent decentralisation programming in Uganda. Development Policy Review, 29 (1), 23–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7679.2011.00512.x

Kauzya, J-M. (2007) Chapter 5: Political decentralization in Africa: experiences from Uganda, Rwanda and South Africa. In: Cheem, G.S. and Rondinelli, D.A. (eds.) (2007) Decentralizing governance: emerging concepts and practices, (pp. 75–91). Washington DC: Brooking Institution Press.

Kopanyi, M. (2015) Local revenue reform of Kampala Capital City Authority. London; International Growth Centre.

Lambright, G.M.S. (2011) Decentralization in Uganda: explaining successes and failures in local governance. Boulder, USA: Lynne Rienner Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781935049999

Lewis, J. (2014) When decentralization leads to recentralization: subnational state transformation in Uganda. Regional and Federal Studies, 24 (5), 571–588. https://doi.org/10.1080/13597566.2014.971771

Livingston N.G. and Charlton, R. (1998). Raising local authority district revenues through direct taxation in a low-income developing country: evaluating Uganda’s GPT. Public Administration & Development, 18 (5), 499–517. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-162X(199812)18:5<499::AID-PAD39>3.0.CO;2-M

Madinah, N., Boerhannoeddin, A., Noriza Binti Raja Ariffin, R., and Michael, B. (2015) Recentralization of Kampala City administration in Uganda: implications for top and bottom accountability. SAGE Open, 5 (3). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244015591017

Mushemeza, E.D. (2019) Decentralisation in Uganda: trends, achievement, challenges, and proposals for consolidation. ACODE Policy Research Paper No. 93. Kampala: ACODE.

Mutibwa, P. (1992) Uganda since independence: a story of unfulfilled Hopes. London: Hurst & Co. Publishers.

Schneider, F. (2002) Size and measurement of the informal economy in 110 countries around the world. Paper presented at a Workshop of Australian National Tax Centre, ANU, Canberra, Australia, July 17, 2002.

Tripp, A.M. (2010) Museveni’s Uganda: paradoxes of power in a hybrid regime. Boulder, USA: Lynne Rienner Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781685856939

Uganda Bureau of Statistics. (2020) World population day celebrations. Kampala: Uganda Bureau of Statistics

Weyland, K. (2001) Clarifying a contested concept: populism in the study of Latin American politics. Comparative Politics, 34 (1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.2307/422412