Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance

Issue 29

October 2024

COMMENTARY

Implementation of Tanzania’s Development Vision 2025: Local Government Authorities’ Endeavours and Challenges

Rogers Rugeiyamu

Local Government Training Institute, PO Box 1125 Dodoma, Tanzania, rogerruge@gmail.com

Corresponding author: Rogers Rugeiyamu, Local Government Training Institute, PO Box 1125, Dodoma, Tanzania, rogerruge@gmail.com

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi29.8443

Article History: Received 06/11/2022; Accepted 13/09/2024; Published 09/10/2024

Citation: Rugeiyamu, R. 2024. Implementation of Tanzania’s Development Vision 2025: Local Government Authorities’ Endeavours and Challenges. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, 29, 113–129. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi29.8443

© 2024 by the author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercial, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Abstract

This paper contributes to the discussion of efforts made by local government authorities (LGAs) to execute Tanzania’s Development Vision 2025. LGAs’ endeavours have revolved around the following areas: establishment of the Women, Youth and People with Disabilities Revolving Fund; the ‘opportunities and obstacles to development’ planning process for increased participation; conducting elections to increase accountability; the furtherance of good governance; and education and health services improvements. Despite their efforts, however, LGAs face continuing dependency on central government, poor capacity for economic management (including mobilisation and administration of revenues), failure to put policies and programmes into practice, deficiencies in governance and inadequate human resources. These have resulted in LGAs’ meagre contributions to Vision 2025 realisation, which have contributed to the country’s limited progress overall. While there is still one year left before the Vision’s 2025 time limit, LGAs will likely only contribute minimally until then. However, the government of Tanzania is in the process of creating a new Vision for 2050, and must ensure that LGAs participate effectively, by granting them autonomy, and effectively boosting their capacity to realise the projected Vision’s goals.

Keywords

Local Government; Tanzania Development Vision 2025

Introduction

In 1999 Tanzania adopted its Development Vision 2025 (United Republic of Tanzania [URT] 1999) to guide economic and social development efforts. This was seen as necessary for Tanzania’s survival in the 21st century, since at the time competition seemed to be the key feature (Docquier and Machado 2016; World Bank Group 2021). International competition requires advanced technological capabilities, high productivity, modern and efficient transport and communications infrastructure, and a highly qualified workforce. Consequently, it was seen as essential that the country strive to achieve those attributes (Rutasitara and Aikaeli 2014; Edson 2019).

The Vision arose from a perceived failure of previous economic reforms – especially those pursued since 1986 – to overcome the economic crisis that had persisted in Tanzania, and most developing countries, since the early 1980s. The then government had adopted the view that prior development strategies and programmes did not include the fundamentals of a market-driven economy and technological advancement taking place elsewhere in the world. As a result, it developed three-year reform plans with strategies that concentrated on just a few economic and social areas, and regularly reviewed those areas of focus. This series of shorter-term ‘structural modification’ programmes was in place for roughly 15 years. Over this extended period, the nation’s vision, which had initially been founded on long-term development goals, was lost, along with the entire philosophy of working for the country’s and its people’s growth. Hence, by the late 1990s Tanzania needed a new long-term development strategy, which would be adopted by the government and society at large.

The government started the formulation exercise in 1995. Vision 2025 was developed under the direction of Tanzania’s Planning Commission, which assembled a team of experts from several societal sectors. Grassroots involvement was encouraged from the beginning, because it was recognised that a national consensus needed to be established over the goals of the Vision. Symposia, conversations and interviews, and gatherings with people in various social contexts, were some of the ways used to encourage engagement from the public. The mass media played a significant role by airing debates and discussions on radio and television programmes, as well as publishing special stories and features in newspapers (URT 1999).

The major question guiding the formulation of Vision 2025 was: What kind of society will have been made by Tanzanians by the year 2025? The inventive reply was that: Tanzanians will be living a high-quality life. This is to say, it was anticipated that Tanzanians would live in a well-developed country with a good standard of living. There would be no more extreme poverty. By 2025, Tanzania would have advanced from a ‘least developed’ to a middle-income country with a high degree of human development. A low-productivity agricultural economy would have given way to a semi-industrialised one driven by modernised, highly productive agricultural activities, successfully integrated and supported by auxiliary industrial and service activities in both rural and urban areas. A strong foundation for a dynamic, competitive economy with high productivity would have been established (URT 1999; National Environment Management Council 2017; Nyanza et al. 2019; Airey 2022).

To achieve all this, the Vision recommended five goals for Tanzanians by 2025. These are: high-quality livelihood; peace, stability and unity; good governance; a well-educated and learning society; and a competitive economy capable of producing sustainable growth and shared benefits (URT 1999; Kiyabo and Isaga 2019; Ndibalema 2022).

The Vision was arranged into six major areas (URT 1999):

• An elaboration of the concept and scope of a national development vision.

• A brief examination of past national development visions with an analysis outlining the successes and challenges experienced thus far, demonstrating why a new development vision was required.

• An introduction to the three principal objectives of the Vision: achieving quality and good life for all; good governance and the rule of law; and building a strong and resilient economy to effectively withstand global competition.

• The development of a culture of empowerment, competence, competitiveness, good governance and rule of law.

• Basic guidelines on the implementation of the Vision, including noting the importance of reforming various existing laws and structures in order to implement the objectives.

• And finally, the participation of the people in preparing and implementing plans for their own development.

Many stakeholders were envisaged in the realisation of the Vision. Ministries and other government institutions, the private sector, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), villages and other social groups are among those mentioned (URT 1999). However, local government authorities (LGAs) were mentioned only twice, and it is doubtful whether they were sufficiently involved in developing the Vision.

Nevertheless, LGAs are key to achieving it. There are several reasons for this. Firstly, almost 99% of the Tanzania population lives within LGAs, which are hence well placed to ensure opportunities for citizen participation and to disseminate the objectives of the Vision. Second, LGAs work in collaboration with sector ministries, for which they implement programmes. Third, LGAs work in particular to realise local economic development.

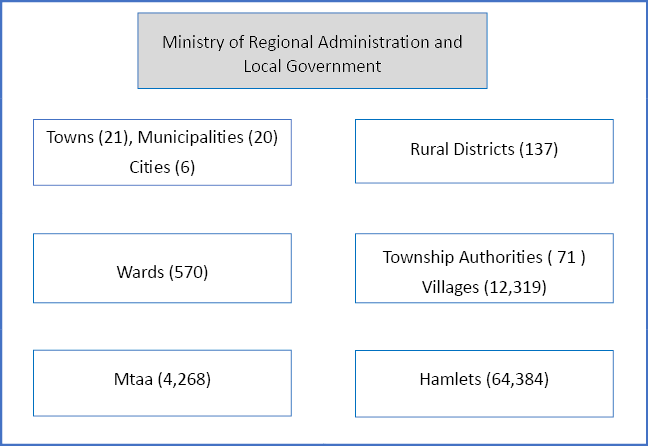

Figure 1 shows the current structure of local government in Tanzania. Currently, there are 184 LGAs on the Tanzania mainland (Association of Local Government Authorities of Tanzania [ALAT] 2020).1 This includes 137 rural districts, 21 towns, 20 municipalities and six cities. Rural districts are divided into townships or villages (shehias), and hamlets (vitongoji). Urban councils are divided into wards and neighbourhoods (mtaa). The number of LGAs has increased substantially in recent years and this has had an effect on the implementation of Vision 2025. LGAs are administered by the Ministry of Regional Administration and Local Government in the President’s Office (PO-RALG).

Figure 1. Local government authorities in Tanzania

Conceptual framework

This paper assesses the efforts of LGAs towards achieving the Vision, and highlights the challenges that LGAs face in effectively implementing its goals. The key questions are: What efforts have LGAs made to date to achieve the Vision? What challenges do LGAs face in realising the Vision? How have LGAs evolved as the implementation of the Vision has progressed? How can LGAs more effectively achieve the Vision in future? Answers to these questions offer lessons for the future prospects of implementing Vision 2025 and the new Vision that will be developed after 2025.

The study took the form of a literature review. This involved analysing numerous reports and research articles sourced from the internet, using selected word searches linked to the contribution of LGAs to the implementation of the Tanzania Development Vision 2025. Research terms included LGAs, the 2025 Development Vision, LGAs’ challenges, LGAs’ efforts, and implementation. In addition, several stakeholder websites were explored, including those of ALAT, the Ministry of Finance and Planning (MOFP), and PO-RALG.

The analysis is anchored in four major categories of factors, which are co-dependent (see Table 1). The first category is the Vision 2025 focus, mentioned above: high-quality livelihoods; good governance; an educated and learning society; a competitive economy; and peace, stability and unity. This forms a base for the second category, which assesses what LGAs have done to realise the Vision focus. So far, LGAs have: engaged with the Women, Youth and People with Disabilities Fund; introduced the improved ‘opportunities and obstacles to development’ (O&OD) participatory planning methodology; conducted local elections; improved the accountability of public officials; and established strategic revenue-generating projects and improved learning environments.

*O&OD: Opportunities and Obstacles to Development

Third, despite these efforts LGAs are confronted with a number of challenges to further realising the Vision. These include ‘central government financial dependency syndrome’ (Rugeiyamu 2022), weak economic management policies, insufficient human resources and ongoing lack of accountability. The fourth category of factors looks at what should be done, and changes needed to improve LGAs’ performance. These include ensuring their autonomy, strengthening revenue mobilisation, capacitating councillors and public servants, and ensuring the demand for and demonstration of accountability.

LGAs before Vision 2025

The Vision’s development began in 1995 and its implementation in 2000. It was catalysed by an extensive evaluation of the country’s politics and policies, failures, development planning framework, and implementation mechanisms. At that time, Tanzania’s mainland had a total of 102 LGAs. In the early 1990s, most mainland LGAs were new in governance, due to their history of abolition and re-establishment in 1982 (Rugeiyamu 2023). They were administered by the prime minister’s office. Nevertheless, as Babeiya (2016) explains, LGAs were attempting to bring governance closer to the people by advocating for citizen participation in development, better services in education, water, roads, health and agriculture, and security in their areas of jurisdiction.

However, LGAs had several shortcomings. The first was ‘central government financial dependency syndrome’. Most LGAs depended on intergovernmental transfers for 90% of their budget. At the same time, central government also depended on external assistance to fund its budget. This affected the implementation of LGA functions due to delays in government transfers (Tidemand and Msami 2010; Pastory 2014; Rugeiyamu 2023). Second, LGAs did not have enough capacity, resources or technical knowhow to mobilise and manage local revenues. Most employees lacked the skills and experience required. This resulted in a shortage of revenue to fund development projects (Ame et al. 2013).

Third, LGAs depended largely on the central government to recruit and supply staff, which meant that most were not answerable to the LGA. LGAs had to submit their human resource needs to the central government and then wait for supply. They often experienced delays in receiving staff and were therefore not in a position to implement their priorities (Kessy 2011).

Fourth, service provision was linked to the line ministries, meaning that councils had no power over service distribution or service levels. Fifth, councillorship was regarded as a prestige position; as a result, most councillors had little experience in actually running councils or capacity to make informed decisions. Sixth, there was a poor relationship between councillors and employees. For instance, councillors were not willing to participate in revenue mobilisation, but demanded allowances for themselves.

In developing the Vision, the government saw the need to change the way LGAs run their businesses to enable them to play a role in implementation. To do so, the government designed the Local Government Reform Programme (LGRP), based on the recommendations of a policy paper from 1998. The paper proposed that the system be based on political devolution and decentralisation of functions and finances, within the framework of a unitary state. It is questionable whether decentralisation can be attained by devolution within a unitary state, given that LGAs are often weak under that form of governance (Kahkhonen and Anthony 2001; Rugeiyamu 2023). However, the paper proposed making LGAs multi-sectoral government units with the status of independent bodies corporate, working within a statutory legal framework but with the ability to exercise discretion in undertaking their functions.

The policy therefore recommended changes across four dimensions of decentralisation:

1. Political decentralisation to integrate previously decentralised and centralised services into a holistic local government system in which councils are the highest political body.

2. Financial decentralisation, giving LGAs discretionary powers to levy taxes and pass their own budgets according to local priorities (the central government’s obligation being to provide both unconditional and other grants).

3. Administrative decentralisation, de-linking LGA staff from national ministries and establishing a local payroll, with LGAs able to recruit their staff in a way decided by the council (Likwelile and Assey 2018).

4. Changes to central–local relations, transforming command-and-control relations into consultation, with line ministries becoming supportive and capacity-building bodies; and regulatory, monitoring and quality assurance institutions added to the local government legislative framework (Kanju and Shayo 2022).

Implementing the policy paper required extensive legislative change – to the Local Government (District Authorities) Act 1982, the Local Government (Urban Authorities) Act 1982, the Local Government Finance Act 1982 and the Regional Administration Act 1997. However, these were only partially amended and to this date fail to fully accommodate the reform objectives and hence allow successful implementation of the policy paper. Hence, amendments made in these legislations still does not provide full autonomy to LGAs (Mnyasenga and Mushi 2015).

All LGAs in existence in 2001 were involved in such changes. The government also established the Local Government Training Institute as a leading institute for achieving decentralisation by offering training, research and consulting services to LGAs so that they can implement the policy and execute their functions effectively.

Evolution of LGAs since 1999

For more than two decades, therefore, LGAs have been striving toward Vision 2025 realisation. Three broad areas of improvement can be identified.

There is an improvement in the recruitment and management of staff in LGAs. LGAs can now recruit up to 22 lower-cadre positions, including village executive officers and ward executive officers, who are mostly trained at the Local Government Training Institute. This is done after approval by the Public Service Recruitment Secretariat. This has been a good first step in enabling LGAs to recruit their own staff, but it falls short of effective autonomy as other cadres including senior positions are still recruited by the central government. And, while in principle all other staff are accountable to each LGA’s elected council, the Council Director is appointed by and answerable to the president. This is contrary to the 1998 policy paper recommendation (Babeiya 2016).

There has also been some devolution of service provision: for example an extension of LGAs’ responsibility for education services, such as primary and secondary schools within their jurisdictions. Also, LGAs now administer district hospitals, dispensaries and health centres (Kapologwe et al. 2020). This promises a substantial improvement in service delivery (Lufunyo 2013; Haule 2014; Maluka et al. 2018; Rugeiyamu et al. 2021; Msacky 2024).

In terms of financial autonomy, LGAs are now developing their own budgets, though these are still fused to the national budget and dependent on central government transfers (Mgonja and Poncian 2019). Most LGAs are able to mobilise local revenues for up to 10% of their budget – but that percentage was achieved even before implementation of the Vision. Their own sources of income include fees, licences, rents, fines and loans. The remaining 90% of budgets is financed by central government transfers, but depends on the capacity of central government to mobilise its own revenues, which is variable and can severely impact LGAs.

Overall, the central government still exercises tight control over LGAs. Mnyasenga and Mushi (2015, p. 942) report that “the minister is mentioned 95 times in the 156 sections of the Local Government (District Authorities) Act 1982; 80 times in the 111 sections of the Local Government (Urban Authorities) Act 1982; and 60 times in the 65 sections of the Local Government Finance Act 1982”. All these provisions seek to control LGAs.

LGAs’ efforts to implement Vision 2025

This section explores what LGAs have done so far towards achievement of the Vision’s goals.

High-quality livelihood

The Vision asserts that the nation’s development should be people-centred and free from abject poverty. Also, it requires that popular participation and empowerment of all social groups should be achieved.

With only another one year to achieve the Vision’s goals, and despite some promising efforts, most people remain in poverty. However, through the Women, Youth and People with Disabilities (WYPD) Fund, LGAs play an important role by offering loans without collateral to enable targeted groups to establish small businesses. Although there have been no significant studies on the success of the fund, it appears to be a remarkable effort. The government started the fund in 1993 to provide seed money for economically disadvantaged populations who could not get loans from financial institutions because they lacked collateral. In 2019, Section 37A was added to the Local Government Finance Act requiring all LGAs to set aside 10% of their revenue collections to provide interest-free loans to registered groups of women, youth and people with disabilities, divided into 4% for women, 4% for youth groups and 2% for people with disabilities. It is noteworthy, however, that these changes were made by the government with only partial or no consultation with LGAs.

There are also concerns about poor management of the fund and the failure of target groups to understand its aims (Daily News 2022; Rugeiyamu 2023). In 2023, a report from the Controller and Auditor General (CAG) on the management of the fund revealed serious deficiencies (CAG 2023). For example:

• Loan beneficiaries in 180 LGAs failed to repay a total of TZS 88.42 billion.2

• 201 groups in eight LGAs had been loaned a total of TZS 774.66 million which, instead of funding approved projects, was distributed as loans among group members with no evidence that the funds were used for their intended purposes.

• In three LGAs TZS 895.94 million was loaned to 48 non-existent groups.

• Nine LGAs had unpaid loans totalling TZS 2.25 billion from 627 groups that stopped operating their businesses for various reasons: lack of customers for the goods or services offered; higher prices for the raw materials used in production; conflicts among group members; theft; members migrating to other locations; and suffering significant losses.

• 53 LGAs had failed to contribute to the fund the required 10% of their own-source earnings – a total of TZS 5.06 billion in unremitted contributions.

Rugeiyamu (2023) reports that most groups still lack sufficient knowledge on the aims of the fund, and suggests this is why they are not concerned about failure to repay loans: they see the money as a government handout. This undermines the performance of the fund and is detrimental to the goal of local economic development.

In terms of popular participation and empowerment, LGAs consist of councillors who are elected by the citizens to make decisions on their behalf, and people can submit their thoughts and attend council meetings to observe council decisions. However, many people are still not aware of these opportunities to improve accountability and ensure responsive government.

Also, LGAs are currently implementing the O&OD process as a planning methodology to empower and involve citizens in development plans (Linje et al. 2022). The process provides an opportunity for individuals or groups at the grassroots to identify challenges and to plan and implement joint community initiatives (CIs) with their own resources and with LGA support (financial, technical and moral). The LGAs must ensure that they accommodate CIs in their budgets. The methodology promises increased participation of people in local development. Maseyu village in Morogoro municipality is a good example of a community that has been successful in implementing the process, and several other LGAs are making good progress (Rugeiyamu et al. 2021).

Peace, stability and unity

Here, the Vision seeks to ensure that the spirit of peace, stability and unity the country has managed to instil since independence is maintained. Through peace and security committees, LGAs ensure that there is peace in their areas. These committees are established at council, village and mtaa (neighbourhood) levels. They are mostly composed of LGA officials and councillors who collaborate with police officers to ensure security in their areas of jurisdiction. Ward executive officers and village executive officers may also be involved in resolving small-scale disputes among citizens.

Good governance

The Vision aspires for people to be empowered and capable of holding political leaders and public servants accountable, with a high level of application of the rule of law in public institutions. In principle, through elections LGAs demonstrate vertical accountability, as citizens have the power to hold political leaders accountable by removing them from office. Tanzania has held five LGA elections (1999, 2004, 2009, 2014 and 2019) for village/mtaa/vitongoji chairpersons. Elections at these levels are conducted by LGAs themselves under the supervision of PO-RALG. Elections for ward councillors were held separately in 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015 and 2020. This is because councillors’ elections are managed by the National Electoral Commission. Elections in LGAs are guided by the Local Government Elections Act 1979 for councillor elections, and the Local Government Authorities Act No. 7 (District Authorities) and No. 8 (Urban Authorities) 1982 for village/mtaa and vitongoji elections. The minister responsible for LGAs is empowered to issue regulations for conducting the village, mtaa and vitongoji elections (National Electoral Commission 2006). The laws appoint city, municipal, town and district directors as returning officers for LGA elections.

Despite LGAs having a mandate to manage their elections, the process encounters several challenges. Firstly, returning officers are presidential/ministerial appointees. Hence, there is a high possibility that returning officers will follow the wishes of those who put them in power by favouring the political party of the president/minister. Evidencing this, in all the elections conducted in LGAs since 1999 the ruling party, Chama cha Mapinduzi (CCM) secured victory (Collord 2021). This appears to violate the democratic principle that the organ that manages elections must be impartial and enjoy the trust and confidence of all stakeholders. In Tanzania, opposition political parties do not trust the system: nearly all opposition parties boycotted the 2019 LGA elections, leaving CCM to emerge victorious.

Secondly, there are reports of failure to follow regulations, causing the postponement of elections. For instance in 2004, during elections in Tanga City, it was reported that there were violent scenes such as burning of ballot papers. In the same election, a legal decision barred the use of the city’s residents’ register in voting due to weaknesses found in it.

Thirdly, poor preparation still affects local government elections. For instance, in the 2004 elections there were too many activities scheduled for the polling day. Chaligha (2005) reported that, in many places, voters were supposed to register and vote on the same day. And, as noted above, in 2019 opposition parties did not participate in elections to express their dissatisfaction with election procedures. This is a result of the lack of an independent election management body better suited to oversee local government elections. Such a body is essential to enhance good governance, especially because the National Electoral Commission (NEC) has been criticised for its lack of transparency in conducting elections and its weak processes for appointing commissioners. NEC commissioners are appointed by the president, who at the same time is chairman of the ruling party and a candidate.

Alongside elections, LGAs are required to develop by-laws and codes of ethics for councillors to ensure they are accountable to the electorate. LGAs also hold their staff accountable through public service laws such as the Public Services Act of 2002, public service standing orders and public service regulations. Also, under the LGA Finance Act 1982, LGAs are supposed to be accountable to citizens for the use of public funds by publishing financial reports that can be accessed by citizens. Some LGAs are doing so, but there are doubts about the accuracy of such reports; nor does the public show much interest in reading them, or awareness of their significance. Moreover, although some LGAs have been sponsoring training for both councillors and officials on good governance and management, the level of accountability anticipated by the Vision has not been achieved (Rugeiyamu 2022).

A well-educated and learning society

LGAs have continued to set aside part of their own-source budget to establish and maintain learning infrastructure, such as classrooms and laboratories in primary and secondary schools. In addition, LGAs have enabled people to establish private schools by allocating land in their areas of jurisdiction, and are willing to allocate land for the construction of colleges and universities. These are good steps towards realising the Vision’s aspirations on education (Daily News 2022).

Strong and competitive economy

The Vision aspires to build a strong and competitive economy capable of meeting development challenges and adapting to changing technologies in regional and global economies. However, despite government efforts, Tanzania’s manufactured goods are still not able to compete in the global market, the level of imports is still higher than exports, and income per capita is low, resulting in continued financial dependency. For instance, the Tanzania Ministry of Finance and Planning (2017) reported that in 2016 gross national income (GNI) per capita was USD900: countries with GNI per capita less than USD1,005 are generally regarded as low income (Edson 2019; Tycholiz and Polus 2022).

LGAs’ efforts to strengthen the economy include supporting the construction of modern markets, eg Mwanjelwa market, and hotels such as the Dodoma City Hotel – setting aside the land for investment and providing building permits to investors (Moraes 2022). These hotels and markets are strategic revenue-generating projects constructed with own-source revenue with the goal of improving LGA revenue mobilisation. Also, the WYPD Fund, which provides loans to women, youth and people with disabilities to develop small businesses, aims to help build a competitive economy.

Ongoing impediments to LGAs’ efforts

There are four key impediments to LGAs playing a more effective role in realising Vision 2025: financial dependence on central government; weak capacity for financial and economic management; more broadly, inadequate human resources; and continuing failures in good governance.

Financial dependency

Most LGAs still depend on the central government to fund about 90% of their budget (Babeiya 2016). This has been the status since the commencement of the Vision. Despite central government and development partners’ efforts to strengthen LGAs’ revenue collection, most are unable to improve (Mgonja and Poncian 2019). Also, the central government has taken some detrimental steps, such as reallocating property tax from LGAs to the Tanzania Revenue Authority in 2016 (Kanju and Shayo 2022).

The logical question to ask is: What is wrong with revenue mobilisation in LGAs? The answer emanates from the 1998 policy paper, which maintained the central government’s role in providing grants to LGAs. Hence, LGAs are trapped in a ‘wait and see’ syndrome, since funding for plans and development projects depends on the capacity of the government to collect revenue or secure loans and grants – which in turn depends on solicitation and development partners releasing funds (Manwaring 2017).

Weak capacity for financial and economic management

Every year, the CAG’s audit of LGAs reports multiple anomalies related to revenue management in Tanzanian LGAs. Most still do not have sufficient capacity to mobilise revenue, implement budgets or manage the revenue-generating projects they are establishing. For example, the CAG’s report for 2021–2022 reported that own source revenue amounting to TZS 11.07 billion was collected through point-of-sale machines but not remitted to the respective LGAs’ bank accounts. Similarly, TZS 76.59 billion in expected revenue was not collected from different sources, such as rental charges for shops and houses located at LGAs’ bus stands and markets, market stalls, sale of plots, agriculture produce, liquor licences, levies for the extraction of construction materials, business licences, and service levies. Moreover, TZS 4.94 billion was not remitted by collecting agents, despite contractual agreements. At the same time, 111 LGAs had expenditures totalling TZS 11.78 billion that were inadequately supported by receipts (CAG 2023). Spending public funds without securing evidence of the goods and services provided raises doubts about the legitimacy of spending and encourages corruption.

Concerning economic management, LGAs have been investing considerable public funds in development projects which are still not operational. For instance, 10 LGAs reported projects worth TZS 3.31 billion that were completed but not operational in the financial year 2021–2022, and 87 LGAs had delayed completion of development projects (CAG 2023). Such delays are caused by a lack of expertise and weak contracts, which fail to build in sufficient accountability for contractors implementing the projects. This tendency results in corruption and causes delay in generating returns, revenue and consistent cash flows.

Again, some LGAs are establishing strategic revenue-generating projects, but failing to run and sustain them. This is experienced in many LGAs, but Kwimba DC (a rice market and warehouse) and Tarime DC (Tarime market) stand out as key examples of failed projects (CAG 2022). Again, some LGAs borrowed money from financial institutions for revenue-generating projects but failed to run the projects or plan how they would raise revenue. Moreover, the CAG (2022) report documents that in 2021 85 LGAs invested TZS 4.88 billion in the Local Government Loans Board, but this investment had not offered any substantial return.

All the above problems are associated with poor innovation skills in LGAs. These result from poor management capacity and inability to accurately forecast the return on projects being implemented.

Inadequate human resources

LGAs still lack sufficient human resources to implement their functions or realise the Vision’s objectives. Many do not have enough skilled middle-level and senior employees. According to the CAG (2023), 747 unqualified workers are now in charge of divisions and units in 106 of the current 184 mainland LGAs, following the adoption of a new council structure for technical staff approved in 2022.3 Similarly, as noted by Rugeiyamu (2023) and CAG (2023), LGAs do not have loan officers who could help, for example, in the management of the WYPD Fund. This is partly why LGAs fail to recover WYPD loans from beneficiaries (Rugeiyamu 2021; CAG 2022). Some do not even have permanent ward executive officers or village executive officers. Moreover, some revenue collectors have limited fiscal knowledge (Fjeldstad 2014).

These problems can be attributed to the centralisation of decisions on recruitment. Although LGAs do have a mandate to recruit lower cadres, they still have to apply for permits from the government. The permit is issued by the President’s Office Public Service Management (PO-PSM) ministry, under the Public Service Recruitment Secretariat (Lawrence and Kinemo 2019). This undermines the ability of LGAs to recruit lower-cadre employees in a timely manner and in line with LGA priorities, as there can be delays by the government in issuing the permit. These are typically caused by the fact that most LGA employees are remunerated by central government, so the issuing of permits depends on the capacity of central government to pay. Additionally, the appointment of middle and senior positions remains in the hands of central government.

Governance failures

LGAs are confronted with accountability challenges on both the demand and supply sides (Hickey and King 2016; Kessy 2020). Citizens have the right to require accountability from LGAs (demand) and LGAs are also mandated to be accountable to citizens (supply). However, in Tanzania many LGAs are not communicating important decisions such as by-laws, financial reports and performance reports to citizens for scrutiny, and some LGAs have failed to implement the O&OD guidelines, which aim to involve community members in development plans. They maintain ‘business as usual’, without significant engagement of community members. Meanwhile, citizens do not demand information, as most have little awareness of what LGAs are supposed to report. Another reason may be that some members of society continue to adopt either a parochial political culture (ie they do not really know what is expected of the government) or a subject political culture (they feel they cannot hold the government accountable, for example because they are afraid of being punished).

Civil society organisations (CSOs) can play a transformative role in empowering citizens to become active participants in governance (Mdee et al. 2022). However, CSOs advocating for policy and legal changes in different aspects such as social services provision, human rights, accountability, good governance, democracy etc often face challenges in fulfilling this role effectively. Most are donor funded and limited or uncertain funding may cause financial difficulties. In some cases, cash flow may be interrupted. For example, the bank accounts of the Tanzania Human Rights Defenders Coalition (THRDC) were frozen for eight months in 2020 for alleged offences. Also, there may be delays in funding approval. All CSOs in receipt of financial donations exceeding TZS 20 million have to apply to the Registrar of NGOs for approval of those funds. Without approval, they cannot implement planned projects. Some CSOs have experienced delays in obtaining approval, especially if projects are concerned with promoting good governance or policy changes, and fear that they may be de-registered due to their advocacy (Rugeiyamu and Nguyahambi 2024).

Moreover, CSOs may experience threats from government leaders and ‘unknown people’ (Rugeiyamu and Nguyahambi, 2024). They may be labelled and named as troublemakers, or foreign agents, which can compromise their public image. And some CSO employees have been arrested due to their advocacy. For instance, in 2019, the programmes officer and ICT officer of the Legal and Human Rights Centre (LHRC) were arrested without being told of their charges.

Conclusion

It is approximately one year until the end of Tanzania’s Development Vision 2025. This paper’s assessment suggests that LGAs have to date hardly contributed to its realisation. This can be attributed to weak institutional capacity, lack of autonomy, huge dependency on central government resulting in poor revenue mobilisation, and a lack of effective strategies to realise the Vision. In light of these constraints, it seems likely that LGAs’ contribution in the Vision’s final year will remain limited, unless central government can empower and capacitate them.

The central government must strengthen LGAs’ autonomy and revenue mobilisation capacity, capacitate councillors and technocrats to manage LGAs, and ensure that decisions taken are consultative. For their part, LGAs need to strengthen their human resource capacity; improve citizen participation by institutionalising an improved O&OD approach; enhance revenue mobilisation and economic management by bringing non-operational projects on stream and undertaking economically viable projects; create environments conducive to investment and industrial development; draw citizens closer to their councils; and avoid a complacent ‘business as usual’ approach.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship or publication of this article.

References

Airey, S. (2022) Rationality, regularity and rule – juridical governance of/by Official Development Assistance. Canadian Journal of Development Studies, 43 (1), 116–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/02255189.2022.2026306

Ame, A., Chaya, P. and John, P. (2013) Under financing in local government authorities of Tanzania: causes and effects: a case of Bahi district council. Global Journal of Human Social Sciences Economics, 13 (1), 9–14.

Association of Local Authorities of Tanzania. (ALAT) (2020) Integration of Tanzania local government authorities in the European cooperation programming process 2021–2027. Available at: http://www.knowledge-uclga.org/IMG/pdf/alat_analytical_report_2020.pdf

Babeiya, E. (2016) Local government in Tanzania and the legacy of a faulty take off. African Review, 43 (1), 128–160.

Chaligha, A. (2005) Lessons from the 2004 grassroots elections in Tanzania. A paper prepared for the 8th East African workshop on democracy.

Collord, M. (2021) Tanzania’s 2020 election: return of the one-party state. France: French Institute of International Relations.

Controller and Auditor General. (CAG) (2022) Annual general report of the Controller and Auditor General for the local government authorities for the financial year ended 2020/21. Dodoma: National Audit Office.

Controller and Auditor General. (CAG) (2023) Annual general report of the Controller and Auditor General for the local government authorities for the financial year ended 2021/22, Vol. 22. Dodoma: National Audit Office.

Daily News. (2022) Tanzania: Dodoma allocates 7bn / - for construction of city headquarters. 11 March.

Docquier, F. and Machado, J. (2016) Global competition for attracting talents and the world economy. The World Economy, 39 (4), 530–542. https://doi.org/10.1111/twec.12267

Edson, M. (2019) Mapping the development progress in Tanzania since Independence. MPRA Paper No. 97534. Available at: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/97534/

Fjeldstad, O.-H. (2014) Tax and development: donor support to strengthen tax systems in developing countries. Public Administration and Development, 34 (3), 182–193. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.1676

Haule, M. (2014) Population, development and deforestation in Songea District. Tanzania. Journal of Natural Resources, 5 (1), 15–24. https://doi.org/10.4236/nr.2014.51004

Hickey, S. and King, S. (2016) Understanding social accountability: politics, power and building new social contracts. The Journal of Development Studies, 52 (8), 1225–1240. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2015.1134778

Kahkhonen, S. and Anthony, L. (2001) Decentralization and governance: does decentralization improve public service delivery? PREM Notes, No. 55 (June), Washington, DC: World Bank.

Kanju, S.D. and Shayo, D.P. (2022) Expect the unexpected? The poli-tricks of central-local government relationship in Tanzania. International Journal of Social Science Research and Review, 5 (8), 130–144. https://doi.org/10.47814/ijssrr.v5i8.388

Kapologwe, N.A., Meara, J.G., Kengia, J.T., Sonda, Y., Gwajima, D., Alidina, S. and Kalolo, A. (2020) Development and upgrading of public primary healthcare facilities with essential surgical services infrastructure: a strategy towards achieving universal health coverage in Tanzania. BMC Health Services Research, 20 (218), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-5057-2

Kessy, A.T. (2011) Local government reforms in Tanzania: bridging the gap between theory and practice. Democratic transition in East Africa: governance and development at the grassroots. Dar es Salaam: TUKI Publishers. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12661/2252

Kessy, A.T. (2020) The demand and supply sides of accountability in local government authorities in Tanzania. Public Integrity, 22 (6), 606–625. https://doi.org/10.1080/10999922.2020.1739361

Kiyabo, K. and Isaga, N. (2019) Strategic entrepreneurship, competitive advantage, and SMEs’ performance in the welding industry in Tanzania. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 9 (62). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-019-0188-9

Lawrence, M. and Kinemo, S. (2019) The myth of administrative decentralization in the context of centralized human resources recruitment in Tanzania. Journal of Public Administration and Governance, 9 (1), 209–218. https://doi.org/10.5296/jpag.v9i1.13798

Likwelile, S. and Assey, P. (2018) Decentralisation and development in Tanzania – Tanzania Institutional Diagnostic. Available at: https://edi.opml.co.uk/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/05-TID_Decentralization-development.pdf

Linje, A., Thakathi, D.R. and Maramura, T.C. (2022) Digital governance implementation: exploring challenges affecting councilors in Shinyanga Municipality and Nzega District Council. International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change, 16 (1), 250–164.

Lufunyo, H. (2013) Impact of public sector reforms on services delivery in Tanzania. International Journal of Social Science Tomorrow, 5, 26–49. https://doi.org/10.5897/JPAPR12.014

Maluka, S., Chitama, D., Dungumaro, E., Masawe, C., Rao, K. and Shroff, Z. (2018) Contracting-out primary health care services in Tanzania towards UHC: how policy processes and context influence policy design and implementation. International Journal for Equity in Health, 17 (1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-018-0835-8

Manwaring, P. (2017) Enhancing revenues for local authorities in Tanzania. International Growth Centre, IPS. Available at: https://www.theigc.org/sites/default/files/2017/10/ALAT-2-page-note-02.10.17v1.pdf

Mdee, A., Ofori, A., Mushi, A. and Tshomba, P. (2022) Indexing local governance performance in Tanzania: unravelling the practical challenges of data, indicators and indexes. Journal of Management and Development Dynamics, 31 (2), 1–35.

Mgonja, M.G. and Poncian, J. (2019) Managing revenue collection outsourcing in Tanzania’s local government authorities: a case study of Iringa Municipal Council. Local Government Studies, 45 (1), 101–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2018.1518219

Ministry of Finance and Planning. (2017) Annual report of Tanzania economic situation for 2016. Dodoma, Tanzania: Tanzania Government.

Mnyasenga, T.R. and Mushi, E.G. (2015) Administrative legal framework of central-local government relationship in mainland Tanzania: is it tailored to enhance administrative devolution and local autonomy? International Review of Management and Business Research, 4 (3), 931–944.

Moraes, C. (2022) Dodoma readies for construction of city headquarters in Tanzania. ConstructAfrica, 12 June 2022. Available at: https://www.constructafrica.com/news/dodoma-readies-construction-city-headquarters-tanzania

Msacky, R.F. (2024) Quality of health service in the local government authorities in Tanzania: a perspective of the healthcare seekers from Dodoma City and Bahi District councils. BMC Health Services Research, 24 (81) https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-10381-2

National Electoral Commission. (2006) Report on elections of the president, members of parliament and councilors. Dar es Salaam: NEC.

National Environment Management Council. (2017) Environmental consideration for sustainable industrialization in Tanzania. Available at: https://www.nemc.or.tz/uploads/publications/sw-1576226406-Environmental%20Consideration%20for%20Industrialization%20in%20Tanzania.pdf

Ndibalema, P. (2022) A paradox in the accessibility of basic education among minority pastoralist communities in Tanzania. Journal on Ethnopolitics and Minority Issues in Europe, 21 (1), 44–68. https://doi.org/10.53779/HPRM0030

Nyanza, I., Pei, Y. and Chang, J. (2019) Challenges of cross border e-commerce in Tanzania: a case study of Tanzania in comparison with China. WHICEB 2019 Proceedings, 42. Available at: https://aisel.aisnet.org/whiceb2019/42

Pastory, P. (2014) Responding to decentralization acrobatics in Tanzania: sub-national actors examined. African Review, 41 (2), 154–184.

Rugeiyamu, R. (2021) The role of improved O&OD methodology in promoting social economy in Tanzania: a solution to sustainable community social development projects? Local Administration Journal, 14 (3), 213–231.

Rugeiyamu, R. (2022) Impromptu decisions: Tanzania’s local government authorities’ challenge in establishing and managing the Women, Youth, and People with Disabilities Fund. Local Administration Journal, 15 (4), 345–361.

Rugeiyamu, R. (2023) Local government’s failure to recover loans from groups of women, youth, and people with disabilities in Tanzania. International Journal of Public Leadership, 19 (3), 210–228. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPL-08-2022-0045

Rugeiyamu, R. and Nguyahambi, A.M. (2024) Advocacy non-governmental organizations (NGOs) resiliency to shrinking civic space in Tanzania. Journal of Humanities and Applied Social Sciences, 6 (3), 258–279. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHASS-08-2023-0096

Rugeiyamu, R., Shayo, A., Kashonda, E. and Mohamed, B. (2021) Role of local government authorities in promoting local economic development and service delivery to local communities in Tanzania. Local Administration Journal, 14 (2), 123–144.

Rutasitara, L. and Aikaeli, J. (2014) What growth pattern is needed to achieve the objective of Tanzania’s Development Vision–2025? Economic and Social Research Foundation Discussion Paper 59.

Tidemand, P. and Msami, J. (2010) The impact of local government reforms in Tanzania 1998–2008. REPOA Special Paper 10/1. Dar es Salaam: Research on Poverty Alleviation.

Tycholiz, W. and Polus, A. (2022) Different times, same story: the (un)changing dynamics of structural dependence in Tanzania. Third World Quarterly, 43 (9), 2269–2288. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2022.2089649

United Republic of Tanzania. (URT) (1999) Tanzania Development Vision 2025. Dar es Salaam: Planning Commission.

World Bank Group. (2021) Raising the bar: achieving Tanzania’s Development Vision. Available at: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/803171614697018449/pdf/Tanzania-Economic-Update-Raising-the-Bar-Achieving-Tanzania-s-Development-Vision.pdf [Accessed 22 February 2024].

1 Since LGAs in Zanzibar do not fall under union jurisdiction as per the constitution of the United Republic of Tanzania of 1977, they are not captured here.

2 TZS 1 billion = approximately US $370,000.

3 The new LGAs structure requires heads of divisions and units to be graduate or above. The President’s Office, regional administration, and local government issued directives with Ref. No. CJB.262/317/01/108 of 16 June 2022, requiring all LGAs to adapt and implement the new approved functions and organisational structure.