Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance

Issue 29

October 2024

RESEARCH AND EVALUATION (PEER REVIEWED)

Strengthening Local Autonomy in Development: Composite Budgeting, Expenditure Planning and Implementation in Nanumba South District, Ghana

Wisdom N-yilyari

Faculty of Planning and Land Management, Simon Diedong Dombo University of Business and Integrated Development Studies, Upper West Region, Ghana, wisdom.nyilyari@yahoo.com

Maxwell Okrah

Faculty of Planning and Land Management, Simon Diedong Dombo University of Business and Integrated Development Studies, Upper West Region, Ghana, mokrah21@ubids.edu.gh

Fauster Agbenyo

Faculty of Planning and Land Management, Simon Diedong Dombo University of Business and Integrated Development Studies, Upper West Region, Ghana, fagbenyo@ubids.edu.gh

Corresponding author: Wisdom N-yilyari, Faculty of Planning and Land Management, Simon Diedong Dombo University of Business and Integrated Development Studies, Upper West Region, Ghana, wisdom.nyilyari@yahoo.com

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi29.8431

Article History: Received 31/10/2022; Accepted 22/05/2024; Published 09/10/2024

Citation: N-yilyari, W., Okrah, M., Agbenyo, F. 2024. Strengthening Local Autonomy in Development: Composite Budgeting, Expenditure Planning and Implementation in Nanumba South District, Ghana. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, 29, 41–58. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi29.8431

© 2024 by the author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercial, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Abstract

Including local citizens in decision-making about the use of local resources is crucial to improving the generation of locally raised funds. This study illustrates the positive effects of composite budgeting – a participatory process – in meeting local people’s development interest and needs, and in promoting expenditure autonomy. Using a case study approach and drawing on both qualitative and quantitative data, the study found that Ghana’s system of district assemblies – which are largely made up of elected members – appears to be relatively successful in delivering the capacity and independence required to make funding decisions that benefit local people and the development of their area. The paper suggests a link between citizens’ confidence in the working of their assembly and their willingness to contribute to locally generated funds.

Keywords

Ghana; Composite Budgets; Participation; Expenditure Autonomy; Development; Local Autonomy

Introduction

Under Ghana’s decentralisation arrangements, the country’s local governments – known as metropolitan, municipal and district assemblies (MMDAs) – are deemed to be the development authorities of their respective jurisdictions. Thus, these local-level bodies are supposed to oversee the development of their populations through the delivery of goods and services that meet the interests of the people (Scutariu and Scutariu 2015). However, the ability to fulfil this mandate requires a balance between the devolved tasks and the capacity of the local authorities to generate financial resources locally (Ministry of Finance 2012). However, it is commonly reported in the literature that in reality local governments generally depend on central government for development resources (Institute for Fiscal Studies 2017; Kapidani 2018).

In Ghana, the level of reliance on central government or external funding by the MMDAs stands at 80%, which is above two-thirds of total annual revenues (Boateng 2014). Some of the local areas generate far less – even below 5% of their total annual revenue (N-yilyari et al. 2023). Despite the differences in resource endowments between local government areas, research shows that MMDAs all seem to have limited capacity for internal revenue mobilisation (Akudugu and Oppong-Peprah 2013; Institute for Fiscal Studies 2017), which affects the fiscal strength of the MMDAs. This, therefore, prevents them from being autonomous.

Previous research has found that a local government’s internal revenue strength is the driver of all other forms of fiscal autonomy (Beer-tóth 2009) – for example autonomy in making financial and development decisions. This makes the fiscal autonomy of local-level government a principal component of the decentralisation discourse, as is noted in the fiscal decentralisation literature (Assefa 2015; Psycharis et al. 2016; Rao et al. 2021; Nirola et al. 2022). ‘Autonomy’ in this context can be defined as the liberty of action of sub-national governments to carry out their tasks and manifest their competencies in an independent manner (Psycharis et al. 2016). Fiscal autonomy (ie the ability to raise and retain local taxes) is the tool that endows local governments with the necessary power and means to effectively deliver their services and allocate resources in a way that reflects the needs of their citizens (Kapidani 2018). Local authorities also have revenue-raising rights in areas such as property rates, licences, investment etc (Darison 2011).

Therefore, fiscal autonomy is the sustaining force of any type of local autonomy, and if financial decentralisation does not provide for it then the decentralisation is only partial (Daudi 2017). The determining variables of fiscal autonomy include the competency of legislation, the level of decision-making power over expenditure, the power to regulate taxes, and autonomy over debt servicing (Stegarescu 2005).

The typology of fiscal autonomy proposed by Guengant and Uhaldeborde (2003) and cited in Beer-tóth (2009) gives a good summary:

• revenue autonomy – the capacity to determine sources, frequency and quantum of financial resources and their use;

• expenditure autonomy – control over public expenditure to meet the demands of local constituents and manage local property; and

• budgetary autonomy – streamlining revenue and spending levels for various projects and activities.

In the Ghanaian context, local governments’ internal revenue has always been low, so it is necessary to examine the level of discretion that local people have in the use of available funds to deliver their desired development. This paper seeks to examine this question, using a case study approach. It focuses on the expenditure autonomy of the Nanumba South District Assembly (NSDA), based on interviews with participants in the district’s composite expenditure planning and management process, and analysis of expenditure performance from 2012 to 2019.

Composite budgeting in Ghana is a system that provides new and better ways of controlling how Ghana’s district assemblies (DAs) plan and budget for their activities, use their resources and account for their spending. It is the process of bringing all the funds available to the decentralised departments into one basket (Quansah 2012). The composite budget process allows for the integration of the assemblies’ central administration budget and the departmental budgets to ensure better coordination, ownership, control and accountability of the budgeting process at the MMDA level (Ministry of Finance 2012). The composite budgeting system (CBS) allows for transparent utilisation and accounting for funds as all stakeholders get to know the various allocations for each of the activities and programmes being budgeted for. The system also provides for collaborative decision-making on planning to enhance the generation of internal revenue: this is done through meetings with representatives of departments to fix rates and fees in consultation with taxpayers. It is also worth noting that Ghana’s CBS policy has named the general assemblies of the various MMDAs (made up of the people’s representatives, mostly elected) as the final authority for decisions on budgeting and funds utilisation. These provisions within the CBS policy have the potential to increase internally (ie locally) generated funds, tighten control over the use of MMDAs’ financial resources and improve the balance between MMDA revenue and spending levels – as proposed by Katongo (1993) over 30 years ago. The consultation process, involving local people in setting financial priorities for each year at the planning stage, enhances the understanding and willingness of the people to contribute to the development of the district.

When citizens are well represented in decision-making concerning the use of their resources for development, the utilisation of the funds is far more likely to meet their interests and needs, thereby enhancing fiscal autonomy. However, in light of the gross dependence of Ghana’s local governments on external funding for development, there is the question of what level of control/discretion they exercise over the funds at their disposal. Previous studies have focused on the mobilisation difficulties MMDAs have encountered in raising local revenue (Akudugu and Oppong-Peprah 2013; Biitir and Assiamah 2015; Puopiel and Chimsi 2015). However, using the Nanumba South district of Ghana as a case study, this paper instead examines firstly the effect of composite budgeting on decisions taken in the district and secondly the effect of composite budgeting on the expenditure autonomy of the district. The period studied is 2012 to 2019.

After this introduction, the paper is organised into six further sections. The second section contains a literature review on related concepts; section three presents the conceptual framework for the study; the fourth section gives background information on the study district; section five covers the research design for the paper; section six deals with the results and discussion; and the last section presents conclusions and recommendations from the findings of the paper.

Literature review

Composite budgeting system

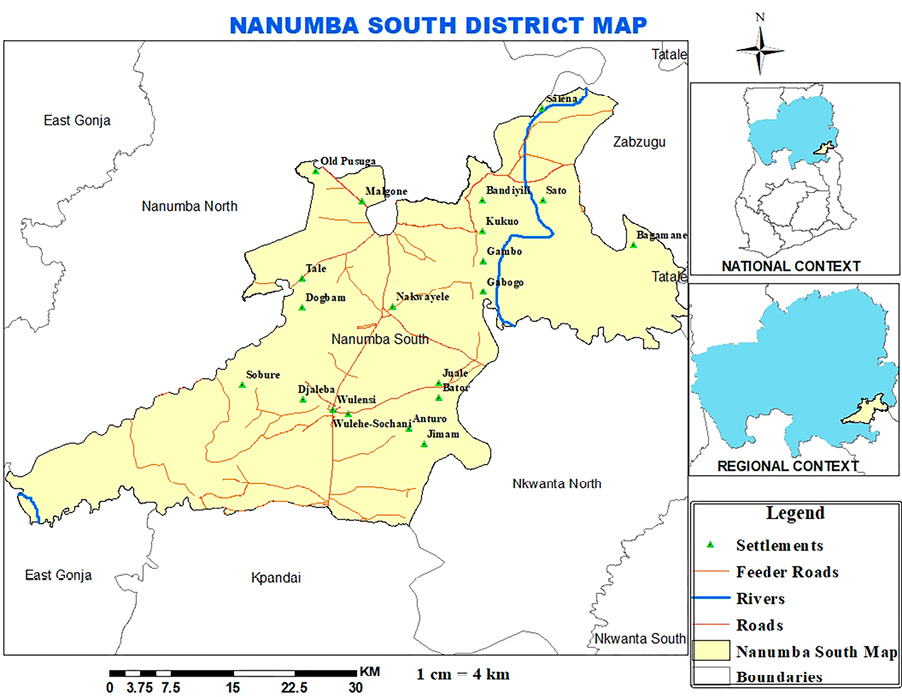

The CBS is a tool adopted in Ghana for financial resource management at the MMDA level (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Composite budgeting cycle

Source: Ministry of Finance (2012)

It is regarded as the improved medium for planning, budgeting and allocating funds, as well as for accounting for expenditures. After being proposed by Katongo (1993), the piloting of the system started in 2003 in three MMDAs (Dangme West, Dangme East and Akuapim North). In 2011, a framework was designed by the Ministry of Finance to roll out the implementation of composite budgeting, which eventually commenced in 2012 nationwide (Quansah 2012). The operationalisation of composite budgeting goes through a five-stage cycle as illustrated in Figure 1.

Capacity, independence and financial management

With regard to the capacity of MMDAs, Yeboah (2014) found, in a study on the financial discipline of MMDAs, that there were issues with the management of financial resources. A later study by the Institute for Fiscal Studies (2017) similarly found that MMDAs’ capacity to develop revenue-generating points, and mobilise the planned revenue, was weak. Another study, on human resource needs in Ghana’s districts by Odoom et al. (2014), revealed that critical roles in the study districts were occupied by people with insufficient qualifications. This finding was supported by Otchere-Ankrah (2018) in a study which specifically found that some districts lacked the critical staff to implement composite budgeting. They attributed the challenge of human resource needs to ineffective institutional arrangements. However, findings from the work of Seim (2015) on the administrative capacity of DAs indicated an improvement in the capacity of the assemblies since the Local Government Service was established to assist with the posting of staff.

The CBS helps in achieving the overall goal of public financial management practices in the country.

In terms of financial management, Ghana has implemented a framework called the Public Financial Management (PFM) system to engender both national-level and sub-national responsiveness, accountability and effectiveness (Institute for Fiscal Studies 2017). For MMDAs, this system allows them to operate within the budgeting and PFM process. Thus, the CBS helps in achieving the overall goal of public financial management practices in the country. In line with this, the Budget and Public Expenditure Management System (BPEMS) was used, which according to Ametefe (2019) was characterised by weak budget preparation, and poor accounting and monitoring. As a result, it has been replaced by the Ghana Integrated Financial Management System (GIFMIS) which was introduced in May 2009 (Duffour 2020). This is an information system that summarises financial transactions through computerised procedures (Attiogbe 2019) and aims to address some of the challenges of the BPEMS. Attiogbe notes that the GIFMIS encompasses budget preparation, implementation and reporting within a central electronic platform, which integrates all ministries, agencies and sectors. It is said to have facilitated, among other improvements, aggregation of financial data, quick public accounting, and improved transparency; although it is not without some challenges (Kwakye 2015; Yeboah 2015). The GIFMIS is the financial management tool currently being used by MMDAs in Ghana.

Fiscal expenditure autonomy

Expenditure autonomy concerns sub-national governments’ capacity to determine the allocation of local funds to pay for the goods and services demanded by local constituents, including local asset management (Beer-tóth 2009). The focus is on the management of the buildings, other assets and funds of the local area in a way that reflects the interest of the people within the area. Thus, the goods and services provided should meet the demands of the people. Another aspect is the freedom to determine the type of goods and services to be funded from the local purse and the amount of money to be expended on each proposed item. In addition, it is the freedom to chart a plan for delivering the various goods and services. Beyond this, the ability of the sub-government authority to effectively carry out the needed action resulting from those decisions is also key.

Expenditure autonomy looks at how much external funding has been used to execute the sub-national governments’ development interventions compared with the total expenditure. In Ghana’s MMDAs, this typically correlates with their degree of dependence on central government transfers (Psycharis et al. 2016; Kopańska 2022). This measure has a direct relationship with revenue autonomy. That is, a sub-national government with low internally generated funds (IGF) will have low expenditure autonomy and one with high IGF will have high expenditure autonomy – as central government policies do not usually give instructions on how IGF should be spent. In this paper, the focus is on the use of MMDAs’ discretionary spending, as well as how accurately spending at the assembly reflect the interest of the people in the district.

Citizen participation and empowerment

The importance of local people’s participation in local development cannot be overemphasised (Agyemang-Duah et al. 2018). The success of decentralisation hinges on inclusiveness and the closeness of local people to information on issues that affect their development (White 2011). For this paper, the World Bank’s (1992) definition of participation has been adopted. It is said to be a “process through which stakeholders influence and share control over the development initiatives, decisions and resources, which affect them”. Citizen participation can result in empowerment outcomes both in specific projects/initiatives and general development dimensions (Babajanian 2014). Benefits of citizen participation in local development include awareness creation, responsiveness to local needs, improvement in leaders/management accountability and transparency, and wider acceptance of decisions and government legitimacy (Babajanian 2014; Sileshi 2017). But to realise these benefits, there is the need for willingness on the part of citizens, fair and effective redress of citizen concerns: including integration of citizens’ feedback into service planning and service delivery by government bodies and other providers (Babajanian 2014). Babajanian opines that platforms for participation should be created through outreach work, information sharing and social mobilisation. Other required conditions suggested are nominating representative groups, a clear definition of authority, trustworthy decision processes and effective facilitation (Irvin and Stansbury 2004).

Conceptual framework

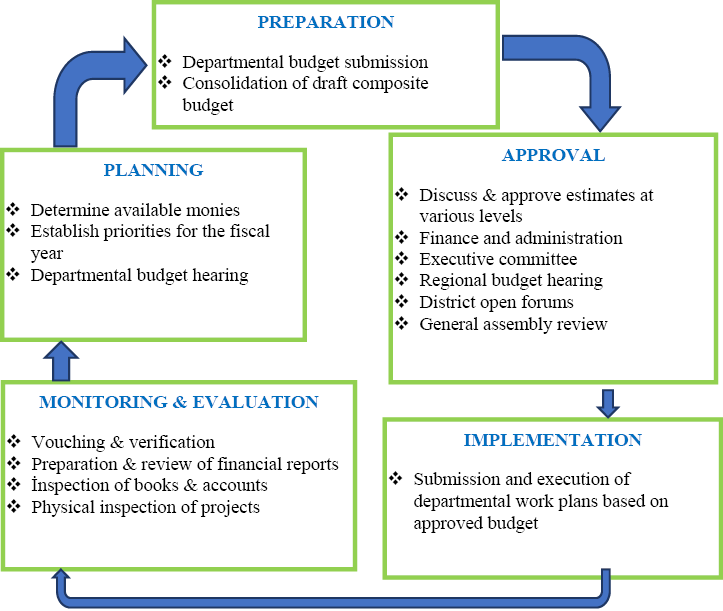

The conceptual framework for this paper is an illustration of the interaction between the means of participation provided by the composite budgeting policy, the capacity and independence of district management staff, and a district’s available resources to achieve local autonomy (fiscal/expenditure autonomy). For expenditure autonomy to be realised, the interest of the people needs to be reflected in the planning and use of the district’s resources. That can only be possible if the people are given the platform to participate in decisions concerning their development, usually through their elected local representatives. Like Arnstein’s (1969) ladder, many models of participation have emphasised mechanisms for citizens’ control over decisions concerning their development (Agbenyo et al. 2021). However, in the context of the composite budgeting process, local people are represented through elected members.

Figure 2 illustrates this three-way interaction. On the horizontal axis, the stages of the fiscal expenditure process are ordered according to degrees of influence and control over decisions, from left to right. On the vertical axis, the representational participation is captured – with the top-most being a local general assembly’s approval of all decisions.

Figure 2. Conceptual framework used in the study

Source: Adapted from Arnstein (1969)

Capacity and independence are also crucial. Given that planning for resource use needs to reflect the interest of citizens to realise expenditure autonomy, when the people’s representatives participate and give a final say on the use of their available resources, then if there is adequate capacity and independence of the management staff, local expenditure autonomy will be enhanced.

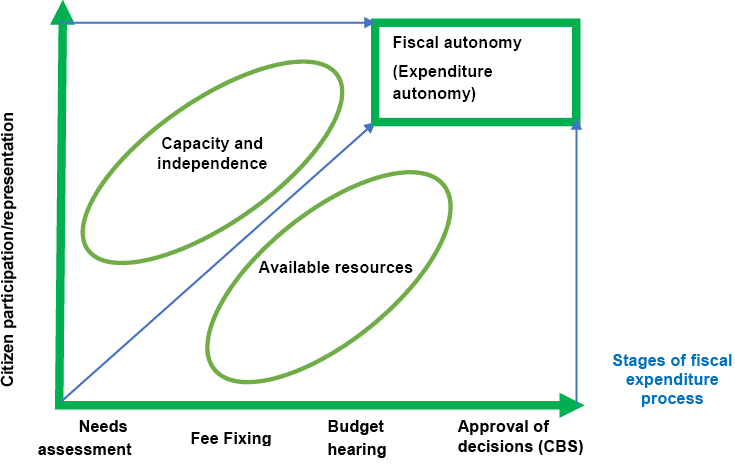

Background of study area

The Nanumba South district was chosen for this study as one of the MMDAs with very low IGF (less than 3%). The district is located southeast of the northern regional capital (Tamale) at a distance of 211km. The district was carved out of the then Nanumba district (which had Bimbilla as the capital town) through Legislative Instrument LI 1763 and inaugurated in August 2004 (Ghana Statistical Service 2014). The district is situated between latitude 8.50N & 9.00N and longitude 0.50E & 0.50W. It occupies 1,789.2 square kilometres, which is about 7% of the Northern Region and about 0.3% of the area of the Republic of Ghana. The district is bordered to the east by Togo and Zabzugu district, and to the west by East Gonja municipality; Nkwanta North district lies in the southeastern, Kpandai district to the south-west and Nanumba North district to the north (Ghana Statistical Service 2014). The geographical location of the Nanumba South district is depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Map of Nanumba South district

Source: Authors’ construct (2022)

With regard to governance, the district has three area councils, made up of 28 electoral areas and 38 unit committees. Each of the electoral areas is represented by an assemblyperson – making a total of 28 assemblypersons, who work alongside government appointees (NSDA 2019). The local economy of the district is dominated by agriculture (Ghana Statistical Service 2014). Other economic activities include service and sales workers, crafts and related trade, formal sector workers (managers, professionals, technicians and clerical support workers), and machine operators, assemblers and elementary occupations. A total of 85% of the working population is in agriculture, and 15% of the workforce is shared among the other occupational engagements in the district (NSDA 2020). This gives a picture of the representation of the citizens through assembly members and the nature of fiscal resources available in the district.

Research design

This paper adopted a mixed-methods approach to enable the collection of both qualitative data on the experiences of the participants and quantitative (statistical) evidence of the district’s expenditure decisions. The qualitative and quantitative strands of the data were collected separately, both were fully mixed and the qualitative strand dominated the quantitative in weight (Leech and Onwuegbuzie 2009). Twenty-nine participants were interviewed for the qualitative data; the interviews were done one-on-one and on a face-to-face basis, with audio tape recordings and handwritten notes. The participants comprised 13 interviewees from various decentralised departments, including the district coordinating director and the finance, planning, and budget officers of the central administration; four assembly members; the presiding member; three revenue collectors, as well as eight community members from the sampled electoral areas. All participants were purposively selected based on their role and engagement with the planning and implementation of the composite budget in the district, except community members who were selected at random. The data collected from all groups were on their experience and role in the composite budgeting process. For the quantitative data, trend analysis was used to assess the district’s expenditure performance over the first eight years (2012–2019) of the composite budget implementation. Interview guides were used to collect the qualitative data from 21 participants while data extraction sheets were used to extract the required expenditure performance statistics from the district’s composite budgets for the quantitative data. Qualitative analysis was done through thematic and content analysis; both handwritten notes and audio tapes were transcribed verbatim and merged for the analysis. With the thematic analysis, after transcription, codes were assigned to units of the data and grouped according to emerging themes for the discussion (Braun and Clarke 2006; Erlingsson and Brysiewicz 2017). The content analysis involved an exploration of the experiential context of interviewees in order to make true meaning of their voices as contained in the data (Vaismoradi et al. 2013). The quantitative data was analysed using Microsoft Excel and presented with descriptive statistical tools (frequency and percentage tables).

Results and discussion

Expenditure autonomy/control over spending

The study set out to examine the effect of composite budgeting on decisions for fund utilisation in the NSDA and to assess the effect of composite budgeting on the expenditure autonomy of the NSDA. It is clear that funding for the NSDA’s development is external as only a minute amount of IGF has been raised by the NSDA over the years (less than 3% of total revenue). However, it is the discretion in the use of these available funds that is the focus of this section.

Independence of district management

In order to make decisions freely, the district must be devoid of external influence and coercion. In contrast to findings on the limited human resource capacity of some MMDAs as identified by Odoom et al. (2014) and Otchere-Ankrah (2018), the management of the NSDA felt they did have independence in deciding on their financial matters. The finance officer noted:

For independence, there is no direct interference from anywhere in the management of the financial resources available to the district. What I can talk about is the oversight responsibility of other bodies such as the Regional Coordinating Council who are also performing their rightful duties. So, when they come around to do their monitoring and make recommendations, we just have to do it. Other areas worth mentioning are the decisions on some parts of the monies disbursed to the MMDAs that are being taken at the national level; that, the assembly has no say in. Some of those include the percentage deductions for some specific purposes as the MP [Member of Parliament] Common Fund, the People Living with Disabilities, etc. and deducting monies to procure certain things for the districts such as trucks at the national level (Interview: finance officer, 2021).

This view was shared by other management officials. The district budget officer, who also serves as secretary to the budget committee, commented that although there are various decisions and instructions on particular expenditure items flowing from the national level, the NSDA management still oversees the allocation of the larger share of the funds. He said:

Even though we don’t determine how much we get from the grants in terms of quantity, and the Common Fund comes with instructions on how to use some of the money, we have control over the allocation of the larger share of the money (70.5%), after the various deductions are made. The donor funding is strictly project-based; so, they decide what their funds are to be used for and not the most pressing need in the district [sic]. The performance-based funds are also project-based, such that they are given to address certain pre-identified developmental issues in the district, like water, electricity, health, education, etc. (Interview: budget officer, 2021).

Table 1 gives statistics on the 29.5% of funds ring-fenced for various items as cited by interviewees, compared to the total amount of District Assemblies’ Common Fund (DACF)1 and other external funds available to the district, over the first eight composite budgeting years.

Source: Nanumba South District Assembly (2014, 2017a & b, 2018, 2019, 2020)

The information in Table 1 confirms the views shared by interviewees that, although there are deductions and instructed use of some percentages of the DACF, the larger portion of the fund’s use is decided by the district’s management. It can be seen from Table 1 that the amounts deducted or instructed are far less than the remaining DACF and that of other external funds (District Development Facility (DDF),2 other Government of Ghana transfers and donor funding).

The district coordinating director (DCD) added his voice to the issue of independence in the use of the district’s resources, as he stated the impossibility of interference in the district’s management due to laid-down structures. Like the finance officer, the DCD acknowledged the role of other external bodies in the operation of NSDA but distinguished their role from interference. He said:

No, the structures are such that nobody will come and interfere because the highest decision-making body is the GA [general assembly] and they approve of whatever we are doing. So, strictly, whatever you are doing must come from your plan. The external person that is coming is only here for monitoring: to see whether you have done what you said you were doing. Certainly, we are also operating within the context of law and policy so you cannot just sit down and be doing what you want, no. There are guidelines as to what you should operate, [but] those you don’t call interference (Interview: DCD, 2021).

The comment of an NSDA member who serves as the finance and administration chair supported the views of the DCD, finance and budget officers. He said: “When people sit outside and [they feel] like they are not seeing development, they think it is the management of the assembly who are denying them. No. The NSDA members have a final say.”

From the views of the interviewees, it is clear that various deductions and instructions affect the regular flow and quantum of DACF to the NSDA; and this is also reported in the literature (Institute for Fiscal Studies 2017; Adamtey et al. 2020). These deductions that are made to fund bulk purchases, but which do not necessarily reflect the needs of the MMDAs, violate the purpose of the allocations, which were meant to be locally managed funds. However, the larger portion of the funds is still controlled by the district’s management. In terms of donor funding and performance-based funds, it is also acknowledged that they will typically be project-based (Boateng 2014); but the choice of specific need areas within the target is decided by the district management. The DCD also clarified that the district is operating within a law and policy framework; so national guidelines and instructions are aimed at streamlining various efforts towards the attainment of broader goals, and it would be unfair to characterise monitoring, supervision or oversight from other bodies in the pursuit of these goals as interference. This finding counter the general view held by the public that there is undue interference in MMDAs’ expenditure choices and financial management. The NSDA member who was finance and administration chairman also stressed the power of decision-making given under devolution and the control of development decisions by the local people, in line with findings by Quansah (2012). He said: “there is no activity in terms of budgeting, planning, and other things that will not be put forward to the assemblypersons for approval and once we reject it, it is rejected…”.

Approval of decisions

A key goal of the CBS is to give power to local people to determine their development (Quansah 2012); that is, putting an end to the practice of transplanting projects from an office far away to a local area without knowing what the people need. Interviewees were united in stating that, in the operationalisation of composite budgeting in the district, programmes, projects and activities are initiated from the community levels. Here, the NSDA members, departments and units of the assembly meet with the communities to conduct assessments and gather evidence of their needs and aspirations. These needs and aspirations of the people are then streamlined through prioritisation according to available resources by the GA to form the District Medium-Term Development Plan, from which annual action plans are teased out and costed in the draft budget.

After the drafted budget has been composed, it is then taken through the regional budget hearing and district budget hearing (where a cross-section of local people has the opportunity to make inputs and seek clarifications). For the public, geographical areas are chosen (randomly), and local people are invited to come and listen and make inputs on a set date. The budget is then sent to the GA for consideration by the NSDA members. Information from the interviews with participants indicated widespread knowledge and acceptance that the owners and decision-making body of the district are the assemblypersons, who represent the people. The management of the district stated emphatically that every decision requires approval from the GA: “the highest decision-making body is the GA and they [must] approve of whatever we are doing. So, strictly, whatever you are doing must come from your plan” (Interview: DCD, 2021). This view was supported by the budget officer:

the owners of the district are the elected members. The annual action plans, they will have to approve them: even in the preparation of the plans, they make inputs. It starts with community action plans where each community brings their action plans or engagement which we compile and use to come out with the budget. So, top decisions are always made at the GA, they make decisions for the district (Interview: district budget officer, 2021).

The staff of the assembly acknowledged and accepted that they carried out their duties based on the decisions of the GA as the owners and highest decision-making body in the district. The NSDA members affirmed this view, namely that every decision taken by the assembly is the handiwork of members, not the staff:

there is no activity in terms of budgeting, planning and other things that will not be put forward to the assemblypersons for approval; once we reject it, it is rejected; and once we approve of it, it becomes a working document. When people sit outside and [feel] they are not seeing development … they think it is the management of the assembly who are denying them. No. The NSDA members have a final say. The coordinating director is just a secretary to the assembly, and the district chief executive is a member; it is the presiding member, who is one of the NSDA members, that leads the house (Interview: finance and administration chair, 2021).

These affirmatory words point to the central place of the GA in decisions concerning use of the district’s financial resources. Furthermore, another member of the NSDA noted that it is only after the GA accepts/approves the budget that it can be implemented as a working document:

the budget remains a draft until NSDA members meet in an assembly sitting to approve it; we do so to ensure that all issues are well attended to before approval is made to the budget as a valid document (Interview: NSDA member, 2021).

The consensus among both members and staff that decisions are taken and/or approved by NSDA members, who are elected representatives recognised as owners of the district, indicates that in Nanumba South at least execution of the budget does reflect the interest of the people. Consequently, it can be said that the people are in charge of their development decisions. This confirms the expectation of the CBS (Quansah 2012; Ministry of Finance 2012) and delivers expenditure autonomy (Beer-tóth 2009).

Expenditure performance of the district

This section covers the categorisation of the expenditure items in the NSDA and how they have performed over the years of composite budgeting. The statistics of expenditure categories over the composite budgeting years and the trend analysis of the expenditure are presented in Table 2. It represents the expenditure performance of the Nanumba South district over the first eight years of composite budgeting. The results show that, over the period, spending on goods and services and assets or capital expenditure – which covers infrastructure and development interventions for the people – have always been on the high side. On average assets, goods and services take up over 80% of the NSDA’s spending each year. It is worth noting that this trend holds a positive for the future development of the district as investment in infrastructure and assets will help to open up growth opportunities. Similarly, goods and services are very essential for the smooth running of the assembly’s day-to-day business. Compensations or personnel emoluments, which are majorly governed by external decisions, occupy on average less than 20% of the spending.

| Fiscal year | Compensation (GH₵) | Goods and services (GH₵) | Assets (GH₵) | Compensation (%) | Goods and services (%) | Assets (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 180,811.36 | 769,779.42 | 1,184,372.19 | 8.5 | 36.1 | 55.5 |

| 2013 | 407,130.65 | 274,633.47 | 2,618,091.60 | 12.3 | 8.3 | 79.3 |

| 2014 | 720,400.00 | 1,365,145.71 | 6,112,657.92 | 8.8 | 16.7 | 74.6 |

| 2015 | 642,620.89 | 1,644,152.48 | 5,635,152.70 | 8.1 | 20.8 | 71.1 |

| 2016 | 792,504.00 | 2,376,926.56 | 6,096,557.93 | 8.6 | 25.7 | 65.8 |

| 2017 | 943,012.58 | 2,774,712.55 | 779,583.18 | 21.0 | 61.7 | 17.3 |

| 2018 | 862,887.28 | 3,457,475.91 | 1,950,947.12 | 13.8 | 55.1 | 31.1 |

| 2019 | 998,933.50 | 3,007,326.90 | 1,588,622.57 | 17.9 | 53.8 | 28.4 |

Source: Nanumba South District Assembly (2014, 2017a & b, 2018, 2019, 2020)

Participants (central administration and NSDA members) agreed that every intervention has received approval from the people. As the budget officer put it: “The owners of the NSDA are the elected members. So, top decisions are always made at the general assembly; they make decisions for the district.” This has been confirmed by an NSDA member: “The budget remains a draft until NSDA members meet in an assembly sitting to approve it … as a valid document.” This indicates that there is a public perception of control over how the available funds are utilised. This also supports the conclusion of Scutariu and Scutariu (2015) that when there is greater fiscal autonomy a sub-national government will better meet the needs of the people to enhance their living conditions. It also implies that the potential of decentralisation in delivering development that meets the interest of local constituents is being realised. It seems clear that where there is greater local control over the expenditure by MMDAs, development in general will be enhanced.

The trend of the various expenditure components in the later years has been attributed to certain factors that characterise the revenue of the NSDA at such points. The key factor, according to the district finance officer and district budget officer, is the funding the NSDA got from the USAID Resilience in Northern Ghana (RING) project from 2017 to 2019. In the words of the budget officer: “The NSDA received huge funding from the RING project which was more [to cover] recurrent expenditure; classified as goods and services.” Also, the district did not receive DDF for the 2017 fiscal year, which typically is focused on capital projects. Regarding the rise in the share of expenditure on compensation, interviewees attributed it to new posts, as well as upgrading and promotion of officers.

These dynamics have implications for the development of the district. Firstly, they reveal the important contribution of donor funding to meeting the needs of local people: since donor support has been directed at social interventions. It also highlights the need for the NSDA to improve its IGF, in order to be able to continue delivering desired development in the absence of donors (Institute for Fiscal Studies 2017). Separately, the gap felt by the absence of DDF monies in 2017 points to the importance of meeting the conditions to qualify for this type of funding, as this fund has been acknowledged as Ghana’s most reliable (Abdul-Kadir et al. 2017). It also means that if the NSDA’s revenue autonomy does not improve, charting a direction for growth will be difficult. As discussed earlier in this paper, IGF is a critical element in the expenditure autonomy of MMDAs. Yet, despite NSDA getting many things right, local people are still reluctant to pay.

Members and staff at NSDA agree that the planning and implementation of IGF has been participatory: “There is no activity in terms of budgeting, planning and other things that will not be put forward to the assemblypersons for approval” (Interview: finance and administration chair, 2021). The NSDA members have also affirmed that the district’s management spends strictly according to the planned budget: “To spend outside the budget, I think is impossible; it is highly impossible …. They spend strictly based on the budget: they cannot spend outside” (Interview: NSDA member, 2021). And furthermore, although as shown in Table 1 the district’s IGF is minute, according to this study’s interviewees its use follows planned protocols. Nevertheless, NSDA members reported that their constituents are not satisfied with the accountability on utilisation of funds, especially the IGF:

An elector even asked in a forum whether there is a project in Nanumba South that has been put up with IGF. That is because the person thinks that money ends up in some individuals’ pockets. When they can boast that the assembly can account accurately for the IGF, I think they will have no problem: they will pay quickly (Interview: NSDA member, 2021).

Another NSDA member reported that the assembly has tried channelling some IGF into physical projects, yet the people are reluctant to pay their taxes. This they attributed to ineffective engagement of some members with their electorates to communicate the activities of the assembly.

Conclusions and recommendations

Empowerment of citizens in relation to decisions regarding their development has been a motivating factor for decentralisation across the globe. It is widely agreed that if decision-making is brought closer to the people, they can take charge of their development. Ghana’s CBS provides for local participation at all stages: determining their needs and aspirations, setting fees and rates for each fiscal year, making inputs to draft budgets and, eventually, giving approval via the general assembly, which comprises mainly the people’s representatives.

In parallel, capacity and independence within district management are essential in deploying the available resources in the best interest of the people and towards the overall development of the district. Despite some constraints due to operational guidance, participants in this study felt that such capacity and independence were present in NSDA. The district’s expenditure pattern presents a positive picture for future development, because over 80% goes into assets, goods and services that facilitate the growth of the local economy. Participatory structures, including the authority of a final say (via assembly meetings) on how resources are used to execute the budget and promote development, ensure a good level of expenditure discretion/autonomy in the NSDA.

As these structures appear to be working relatively well, this paper calls for greater expenditure autonomy from Ghana’s central government and its ministries, departments and agencies, to allow the assemblies to propel more local development. The authors recommend that assemblypersons, in collaboration with the national Information Services Department and civil society organisations, should both strengthen accountability mechanisms and ensure citizens are fully aware of how resources are used. The authors believe that doing this would enhance citizens’ willingness to contribute to IGF.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship or publication of this article.

References

Abdul-Kadir, M., N-yilyari, W. and Suleman, N. (2017) The challenges and prospects of Ghana’s composite budgeting, the case of Wa Municipal Assembly. Tamale, Ghana: University for Development Studies.

Adamtey, R., Obeng, G. and Sarpong, T.E. (2020) A study towards deepening fiscal decentralization for effective local service delivery in Ghana. Accra: Good Governance Africa.

Agbenyo, F., N-yilyari, W. and Akanbang, A.A.B. (2021) Stakeholder perspectives on participatory monitoring and evaluation in educational projects in Upper West Region, Ghana. Journal of Planning and Land Management, 2 (1), 50–64. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.36005/jplm.v2i1.34

Agyemang-Duah, W., Kafui Gbedoho, E., Peprah, P., Arthur, F., Kweku Sobeng, A., Okyere, J. and Dokbila, J.M. (2018) Reducing poverty through fiscal decentralization in Ghana and beyond : A review. Cogent Economics & Finance, 6 (1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2018.1476035

Akudugu, J.A. and Oppong-Peprah, E. (2013) Local government revenue mobilisation and management: the case of Asante Akim South District Assembly, Ghana. Journal of Public Administration and Governance, 3 (2), 98–120. https://doi.org/10.5296/jpag.v3i2.3977

Ametefe, R.K.Y. (2019) Evaluation of Ghana Integrated Financial Management Information System (GIFMIS) of financial reporting quality of Ghana education service. Accra, Ghana: University of Ghana.

Arnstein, S. (1969) A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of American Planning Association, 35 (4), 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225

Assefa, D. (2015) Fiscal decentralization in Ethiopia: achievements and challenges. Public Policy and Administration Research, 5 (8), 27–40. https://www.iiste.org/Journals/index.php/PPAR/article/viewFile/24944/25547

Attiogbe, D.A. (2019) Assessment of the implementation of integrated financial management information system on financial accountability among municipal and district assemblies in the volta region of Ghana. University of Cape Coast. https://ir.ucc.edu.gh/xmlui/handle/123456789/4622

Babajanian, B. (2014) Citizen empowerment in service delivery. Asian Development Bank Economic Working Paper Series, 396. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781784715571.00020

Beer-tóth, K. (2009) Local financial autonomy in theory and practice: the impact of fiscal decentralisation in Hungary. Fribourg, Switzerland: University of Fribourg Switzerland.

Biitir, S.B. and Assiamah, J.K. (2015) Mobilising sustainable local government revenue in Ghana: modelling property rates and business taxes. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, (16–17), 224–241. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.v0i0.4496

Boateng, M. (2014) Rethinking fiscal decentralization policies in developing economies: a case study of Ghana Brock University. http://hdl.handle.net/10464/5458

Braun, V. and Clarke, V. (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3 (2), 77–101. https://doi.org/DOI: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Darison, A.B. (2011) Enhancing local government revenue mobilization through the use of information communication technology: a case-study of Accra Metropolitan Assembly. Kumasi, Ghana: Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology.

Daudi, M.H. (2017). Fiscal autonomy of local government authorities: reflection on the Constitution and the Local Government Finances Act. Journal of Law, Policy and Globalization, 63 (2003), 256–264.

Duffour, E. (2020) An examination of implementation of Ghana Integrated Financial Management Information System (GIFMIS). PhD thesis, University of Cape Coast, Ghana.

Erlingsson, C. and Brysiewicz, P. (2017) A hands-on guide to doing content analysis. African Journal of Emergency Medicine, 7 (3), 93–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.afjem.2017.08.001

Ghana Statistical Service. (2014) 2010 Population and housing census, district analytical report for Nanumba South district. Accra, Ghana: Ghana Statistical Service.

Institute for Fiscal Studies. (2017) Mobilizing adequate domestic revenue to support Ghana’s development (No. 8, Fiscal Alert). Accra, Ghana: Institute for Fiscal Studies.

Irvin, R.A. and Stansbury, J. (2004) Citizen participation in decision making: is it worth the effort? Public Administration Review, 64 (1), 55–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2004.00346.x

Kapidani, M. (2018) A comparative analysis of local government financial autonomy in Albania. Journal of Business, Economics and Finance, 7 (1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.17261/pressacademia.2018.790

Katongo, M.C. (1993) Budgeting for development at the district level: an examination of the composite budgeting system with reference to Ahanta West District. Kumasi, Ghana: Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology.

Kopańska, A. (2022) Local governments’ revenue and expenditure autonomy as a determinant of local public spending on culture. An analysis for Polish rural municipalities. European Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies, 7 (2), 16–35. https://doi.org/10.26417/ejms.v5i1.p222-233

Kwakye, A.K. (2015) Benefits and challenges of Integrated Financial Information Management System (case study G.E.S Obuasi Municipal). Kumasi, Ghana: Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology.

Leech, N.L. and Onwuegbuzie, A.J. (2009) A typology of mixed methods research designs. Quality and Quantity, 43 (2), 265–275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-007-9105-3

Ministry of Finance. (2012) Composite budget manual for metropolitan/municipal/district assemblies (Issue November). Accra, Ghana: Ministry of Finance.

N-yilyari, W., Okrah, M. and Agbenyo, F. (2023) The contribution of composite budgeting to sustainable fiscal autonomy in the Nanumba South district of the Northern Region of Ghana. Journal of Environment and Sutstainable Development, 1 (2), 11–24. https://doi.org/10.55921/tooo5668

Nanumba South District Assembly. (NSDA) (2014) District medium term development plan (DMTDP) for 2014–2017. Accra, Ghana: National Development Planning Commission.

Nanumba South District Assembly. (NSDA) (2017a) Composite budget for 2018-2021: programme based budget estimates for 2018. Accra, Ghana: National Development Planning Commission.

Nanumba South District Assembly. (NSDA) (2017b) District medium term development plan (DMTDP) for 2018–2021. Accra, Ghana: National Development Planning Commission.

Nanumba South District Assembly. (NSDA) (2018) Composite budget for 2019–2022: programme based budget estimates for 2019. Accra, Ghana: National Development Planning Commission.

Nanumba South District Assembly. (NSDA) (2019) Composite budget for 2020–2023 programme based budget estimates for 2020. Accra, Ghana: National Development Planning Commission.

Nanumba South District Assembly. (NSDA) (2020) Composite budget for 2020–2023 programme based budget estimates for 2021. Accra, Ghana: National Development Planning Commission.

Nirola, N., Sahu, S. and Choudhury, A. (2022) Fiscal decentralization, regional disparity, and the role of corruption. The Annals of Regional Science, 68, 757–787. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-021-01102-w

Odoom, D., Kyeremeh, C. and Opoku, E. (2014) Human resource capacity needs at the district assemblies: a study at Assin South District Assembly in Ghana. International Journal of Sustainable Development, 7 (5), 177–188. https://doi.org/10.5539/jsd.v7n5p177

Otchere-Ankrah, B. (2018) The implementation of the composite budgeting system in Ghana – using three local governments (Issue 10329844). Accra, Ghana: University of Ghana.

Psycharis, Y., Zoi, M. and Iliopoulou, S. (2016) Decentralization and local government fiscal autonomy: evidence from the Greek municipalities. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 34 (2), 262–280. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263774X15614153

Puopiel, F. and Chimsi, M. (2015) Mobilising internally generated funds to finance development projects in Ghana’s northern region. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, (18), 147–160. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.v0i18.4848

Quansah, O. (2012) Local government composite budget in Ghana. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=woBIx5KTbHs&t=251s

Rao, M., Mukherji, A. and Swaminathan, H. (2021) Trends in rural fiscal decentralisation in India’s Karnataka state: a focus on public health. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, (25), 56–78. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi25.7583

Scutariu, A.L. and Scutariu, P. (2015) The link between financial autonomy and local development. the case of Romania. Procedia Economics and Finance, 32, 542–549. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2212-5671(15)01430-6

Seim, P. (2015) Building the administrative capacity of district assemblies in Ghana; examining the role of staff postings. Accra, Ghana: University of Ghana.

Sileshi, L. (2017) Assessment of community participation on local development projects: the case of Oromia Regional State. International Journal of Research in Social Sciences, 7 (10), 47–67. http://www.ijmra.us

Stegarescu, D. (2005) Public sector decentralisation: measurement concepts and recent international trends. Fiscal Studies, 26 (3), 301–333. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5890.2005.00014.x

Vaismoradi, M., Turunen, H. and Bondas, T. (2013) Content analysis and thematic analysis: implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing and Health Sciences, 15 (3), 398–405. https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12048

White, S. (2011) Government decentralization in the 21st Century. Washington, DC: Center for Stategic & International Studies. https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/legacy_files/files/publication/120329_White_Decentralization_Web.pdf

World Bank. (1992) Participatory development and the World Bank. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Yeboah, P.A. (2014) The extent of financial discipline in district assemblies in Ghana. a case study of the Birim North District Assembly, Eastern Region. Kumasi, Ghana: Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology:

Yeboah, S. K. (2015) Public sector financial management reforms in Ghana: The case of Ghana Integrated Financial Management Information System (GIFMIS). Accra, Ghana: University of Ghana.

1 DACF is MMDAs’ main external revenue source (Ghana Constitution, Art. 252 and DACF Act 2003). It guarantees (currently) 7.5% of national revenue annually, disbursed quarterly.

2 The DDF is a pool fund from development partners and the Ghana government which was established in 2006 to support MMDAs’ development. Allocation of the fund is guided by District Assembly Performance Assessment Tool.