Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance

Issue 28

September 2023

RESEARCH AND EVALUATION (PEER REVIEWED)

How Informal Ties Matter: Encroachment on Road Reservations Along the Kumasi–Accra Highway in Ghana

Ronald Adamtey

Department of Planning, College of Art and Built Environment, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana, radamteysekade@gmail.com

Florence Aburam

Department of Planning, College of Art and Built Environment, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana, aburamflorence@gmail.com

Benjamin Doe

Department of Planning, College of Art and Built Environment, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana, bdoe@knust.edu.gh

Clifford Amoako

Department of Planning, College of Art and Built Environment, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana, camoako.cap@gmail.com

Corresponding author: Ronald Adamtey, Department of Planning, College of Art and Built Environment, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana, radamteysekade@gmail.com

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi28.8260

Article History: Received 30/06/2022; Accepted 12/06/2023; Published 25/09/2023

Citation: Adamtey, R., Aburam, F., Doe, B., Amoako, C. 2023. How Informal Ties Matter: Encroachment on Road Reservations Along the Kumasi–Accra Highway in Ghana. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, 28, 84–104. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi28.8260

© 2023 by the author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercial, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Abstract

A failure of urban planning in many developing countries is evidenced by encroachment on road reservations. Urban planning literature suggests that such encroachment is largely explained by poverty and urban growth. But how do encroachers find space in the road reservations? This paper examines encroachment along the Anloga Junction to Ejisu section of the Kumasi–Accra highway in Ghana. It argues that formal rules are not effective in governing the road reservations: informal rules rooted in social networks of reciprocity matter more. The research involved interviews with encroachers, senior officials from government institutions and traditional authorities. It emerged that encroachers invoked mainly ethnic and political party ties with public officials to secure space in the road reservations. This occurred in an environment of non-enforcement of relevant laws, weak formal collaboration among public institutions, and inadequate political commitment. There is a need for effective application of the principles and methods of multi-stakeholder governance, linking improved legal regulation with informal processes, to achieve better outcomes.

Keywords

Encroachment; Informal Networks; Road Reservations; Urban Planning; Ghana

Introduction

Urban planning in many rapidly growing cities in Africa appears to be failing, and the need for resilient responses to the challenges involved has attracted public policy and scholarly interest globally (Pharoah 2016; World Bank 2016; Cobbinah 2021). One aspect of the general failure of urban planning is extensive encroachment on road reservations. This mainly impacts highways, which are typically planned with wide reserved areas along the corridor for future expansion of road infrastructure (Law Insider 2020). The reservation width varies from country to country. In Uganda, it is 40 metres on both sides of the highway (Independent News 2019); in Kenya also 40 metres (Government of Kenya 2007); and in Tanzania 60 metres (Tessema and Kahumbire 2019). In Ghana it is 45 metres on both sides.

Encroachment occurs when people use public lands for private activities without authorisation. In the case of road reservations, the public interest is compromised by developers who extend buildings or install other structures without proper authorisation within the space designated for transport purposes (Melbourne City Council 2003; Woollahra Municipal Council 2021). Encroachment along major highways is an issue for planning in many developing countries: the literature shows urban growth and expansion in recent times occurring along major infrastructure corridors linking large cities, and a significant part of that growth encroaching on road reservations (World Bank 2012; Balakrishnan 2013; Rodrigue 2020). But many local governments struggle to control encroachment, especially along road corridors that are beyond their jurisdiction (Balakrishnan 2013).

For Ghana, the evidence suggests that poverty and increased urban populations due to migration from rural areas into the cities is one of the most important factors explaining encroachment into road reservations. While many of the migrants do not have the skills for the few job opportunities in either the formal or informal sectors in the cities, and have little capital, there are opportunities to set up their own small businesses. The common space to set up such a business is the road reservation. Although their operations can be described as illegal, those businesses provide a means of livelihood for many families (International Labour Office 2004; Osei-Boateng and Ampratwum 2021). From that perspective, many of the business activities along the road reservations represent a significant focus of economic development.

However, as well as the loss of public space and opportunities to upgrade highways, private encroachments can pose problems such as exacerbating poor drainage, causing street obstructions and creating long-term safety risks. Globally, these issues have received a lot of scholarly interest (Owubah et al. 2000; Devika 2018; Tshering 2018; Lake Macquarie City Council 2020), and a number of cities have established mechanisms and planning arrangements to manage encroachment. In New Zealand, for example, New Plymouth District Council (2011) has a road reservation encroachment policy that enables transparent decision-making and management of encroachment through issuing licences. The City of Melbourne, Australia, also has guidelines which apply to the whole of the municipality in regard to structures or parts of buildings that project or encroach into the road space. In Tanzania, the imposition of fines on encroachers on the public right of way helps in controlling development on road reservations (Sundet 2005). Similarly, Uganda’s Road Act 2019 (Act 16) specifies the circumstances under which road reservations can be used and the consequences for any encroachment (Government of Uganda 2019); and strong formal rules govern the use of road reservations in Rwanda with serious penalties for encroachment (Government of Rwanda 2011). In all these examples, we find that the management and control of road reservations are governed by formal rules and regulations.

So which formal rules and regulations exist in the governance of road reservations in Ghana? How do people in practice find space in the road reservations along major roads? How can formal and informal rules and regulations work together to respond effectively to the needs and interests of multiple stakeholders in order to guide and successfully manage encroachment that appears inevitable? And given the role these activities play as livelihood support for many families in Ghana, should they be prevented, or instead regulated and taxed appropriately – rather than encroachments being threatened with removal or demolition by city authorities, and with their owners prosecuted for evading taxes?

This paper seeks to answer those questions by exploring the processes through which encroachers in the road reservations have found space, using the Anloga Junction to Ejisu section of the Kumasi– Accra highway as a case study. The paper’s core argument is that formal rules and regulations are not effective in governing the road reservations. Informal rules rooted in social networks of reciprocity matter more, yet these are not adequately understood or considered by public institutions whose mandate it is to prevent encroachment. Supporting this argument, the research addresses the following objectives:

(i) to identify and map the stakeholders and their interests in the road reservations;

(ii) to identify the formal and informal ties existing between the stakeholders and how those ties explain how people find space in the reservations;

(iii) to describe the challenges facing the public institutions in the governance of the case study road reservations; and

(iv) to make recommendations towards effective governance of the reservations along the Anloga Junction to Ejisu road.

The remainder of the paper is organised in seven sections. These cover examples of experiences with encroachment in selected African countries, including Ghana; a conceptual framework for the research; the study context, area, research design and methodology; findings; discussion; and conclusions and recommendations.

Experiences with encroachment in Kenya, Uganda, Nigeria and Ghana

In a study to understand the factors contributing to illegal occupation and developments on alienated public land for road corridors in Kenya, Kariko (2009) finds a weak legal framework and land administration system, poor enforcement of regulations, poverty, and population increase as some of the causes. In Uganda, Kaweesa’s (2015) study to assess and appraise the management of road reservations in Kampala District finds that most encroachers had limited knowledge about road reservations (New Vision 2020), and blames encroachment on flaws in the mechanisms used by road authorities to mark the extent of reservations. In Nigeria, studies have found that violation of development control guidelines championed by public and semi-public agencies typically occur because agencies have themselves broken the guidelines, or have deliberately allowed people to violate them, or have just turned a blind eye to encroachment. This has led to unlawful development along major highways (Sanusi 2006; Ubangari and Babarinsa 2012; Damina et al. 2016). In Ghana, the Ghana Highway Authority (GHA) has expressed grave concern over the continuing development of properties by developers in road reservations along the Kumasi–Accra highway, and has cautioned that such development constitutes illegal encroachment (Modern Ghana 2009; Republic of Ghana 2016).

Civil society organisations and human rights groups sometimes raise objections to the eviction of encroachers with the argument that the people involved earn their livelihoods from using the space. Encroachments therefore must be carefully assessed and controlled, to ensure appropriate and sustainable development in the best interests of the public (Melbourne City Council 2003). To be able to do this in Ghana will require management of the multiple stakeholders with their many interests along the highways.

Experiences in Kenya, Uganda, Nigeria and Ghana show that encroachers’ interests can broadly be categorised into business activities and housing. So how can these forces be managed?

Conceptual framework

This research rested on two broad theoretical concepts: multi-stakeholder governance and informal networks.

The practice of multi-stakeholder governance reflects the diverse distribution of power in society and a conception of democracy whereby a variety of stakeholders become central actors in the decision-making process. To balance their interests, actors from civil society, business and governmental institutions come together to find common solutions to problems that affect them. Governance of multi-stakeholder interests demands a comprehensive and interactive approach towards stakeholder management (Roloff 2008; Fransen 2012). One downside of multi-stakeholder governance is that, despite the procedural rules, stakeholders may experience anxiety concerning the motivation of others for participating and the possibility that their willingness to cooperate and share information will be abused (Bobrowsky 1999; Gleckman 2018; Schleifer 2019).

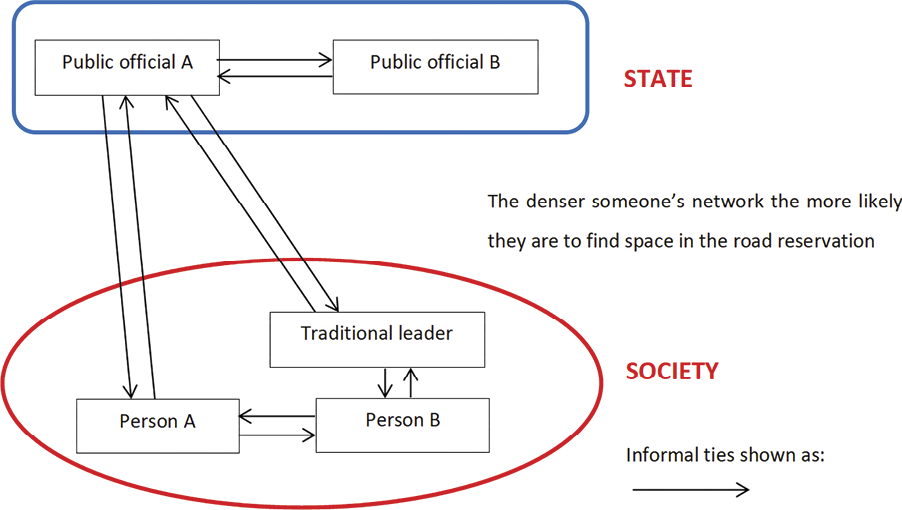

Informal networks may include friendship ties, family and kinship relations, ethnic and hometown networks, religious affiliations, and political parties; all of which are discussed later in this paper. These ties may come in the form of ‘embeddedness’ – ie ‘vertical’ relationships and networks that develop between public officials in governments and private actors in society such that both tend to develop shared aspirations and interests (Evans 1995). Informal ties constitute strong forces that shape the life and behaviour patterns of most people (Boone 1998; Mungiu-Pippidi 2006; Brinkerhoff et al. 2007; Hyden 2007). They reflect the need for societies to create systems of exchange and reciprocal support (World Bank 2001; Mungiu-Pippidi 2006; Crook and Hosu-Porbley 2008). The behaviour of public officers in such systems can shape the way in which formal processes operate to produce expected outcomes (Hellman and Ndumbaro 2002). Specifically, informal ties may influence whether or not public officers are able to enforce road reservation controls.

The extent of encroachments along the Anloga Junction to Ejisu section of the Kumasi–Accra highway points to ineffective formal rules and regulations, which may be said to be weak and not inclusive enough. Part of the difficulty in controlling encroachment is that we do not adequately understand the role of informal ties and social networks in the equation. Encroachers may use strong ‘vertical’ informal ties through embeddedness to find and protect space in the road reservation. Consequently, this research study applied theories of informal ties and networks and embeddedness to describe the key actors, their interests and their decision logics in the reservations along the study road corridor.

Figure 1 depicts informal ties as those between persons A and B in society, or between public officials A and B in the state. Embeddedness is when these ties exist between public officials in the state and citizens in society: the vertical relationships. Also shown is the intermediary role that may be played by traditional leaders.

Figure 1. Informal ties and embeddedness

Unlike Western countries, the family system practised in most African countries extends beyond the nuclear family to include the extended network of relatives, friends and neighbours. The mass movements of people into urban centres in countries such as Ghana causes some detachment from their immediate and extended families in rural areas. This has given rise to the need for a sense of belonging with friends, colleagues and neighbours in the cities who constitute their new family (Hanson 2004; Alesina and Giuliano 2007; Crook and Hosu-Porbley 2008). These ties can be invoked by encroachers in the road reservations to obtain and control space.

Additionally, most people across Africa are identified with their ethnic or tribal groups. Factors such as the desire for security and for power over resources and trade during the period of colonisation reinforced ethnic identities, and strong ethnic attachment or solidarity became a key factor in the structure of African politics (Cohen 1996; Malowist 1966; Leonard and Pitso 2009). Evidence also shows that many political parties have their roots in constituencies created by local leaders appealing to ethnic norms and solidarities. Consequently, most parts of Africa have seen ethnic groups pledging their allegiances to specific political parties (Chazan 1982; Tignor 1993).

Another important factor in Africa is religion, which appears to be one of the easiest ways to mobilise people. Religion enjoins dedication and commitment towards one’s deity and fellow adherents, and is spreading widely throughout Ghana. There are strong ties among public officers connected by common religious affiliations. They can obtain cooperation or assistance from one another by directly or indirectly invoking their religious links (Brempong 1997; Parra et al. 2016).

A dense network of various types of informal ties therefore brings great benefits to some people. The downside is that a lack of informal ties can exclude other people from having access to opportunities or prevent them benefitting from state resources (Hellman and Ndumbaro 2002; Kimenyi and Mbaku 2004; Grodeland 2005; Fagernäs 2006; Egwu et al. 2009).

Study context

Decentralisation and land management in Ghana

Ghana implemented decentralisation reforms in the mid-1980s to promote development at the local level, and collaboration and coordination between decentralised institutions (Saito 2003; World Bank 2004; Republic of Ghana 1993 and 2016). The reforms also aimed to encourage citizens whose lives are affected by policy decisions to participate in shaping the outcomes of policy (Olowu and Wunsch 2004; World Bank 2004). There are 16 administrative regions in the country. For each region, a regional coordinating council (RCC) forms the highest political authority. Regions are further divided into local government districts, for which the RCCs have responsibilities for monitoring, coordinating and evaluating performance. Each district has an elected district assembly1 and an administration of public officials. District chief executives and 30% of the councillors are political appointments made by the central government. The local member of parliament is also a member of the district assembly. The remaining 70% of the councillors are elected by the local people. District assemblies are the local planning authorities with overall responsibility for the development of areas under their jurisdiction.

Lands in Ghana are mainly under the control and management of traditional authorities (chiefs) who hold the land in trust for their subjects (Republic of Ghana 2008). As custodians of the land, chiefs allocate parcels to developers, subject to district planning schemes (Republic of Ghana 2016). There are also state lands owned by the government of Ghana, with specific state agencies responsible for their management and control. Highways and their reservations are government lands under the management of the Ghana Highway Authority together with MMDAs. However, many chiefs across the country claim customary rights over these lands.

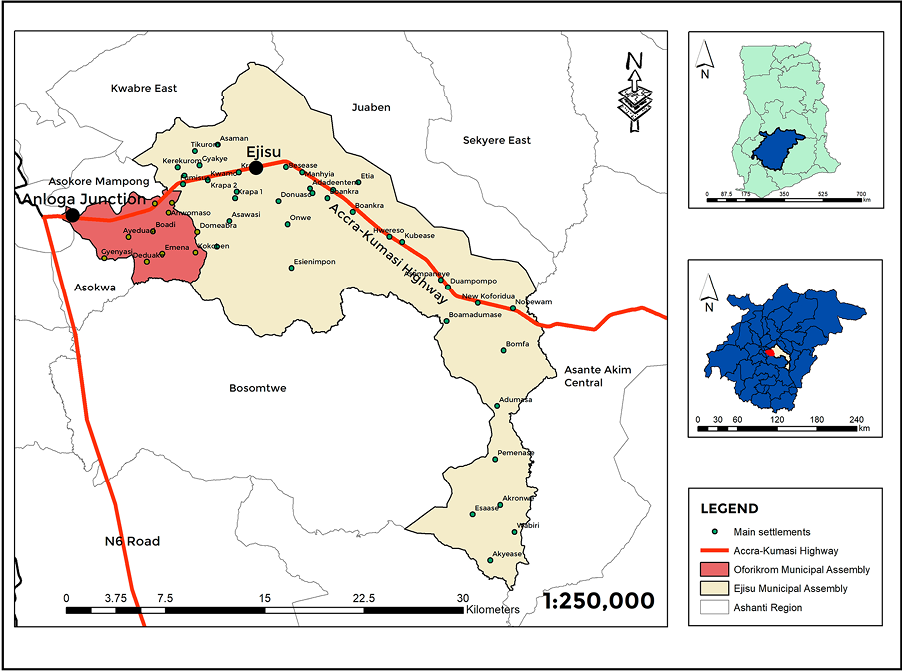

Study area

The study was focused on the Anloga Junction to Ejisu section of the N6 highway that runs from Kumasi to Accra (see Figure 2). The 11-kilometre stretch of road passes through a number of towns in two municipal areas: the Oforikrom Municipal Assembly (OfMA) and the Ejisu Municipal Assembly (EJMA), both in the Ashanti region of Ghana (Ghana Statistical Service 2014; EJMA 2018; OfMA 2018).

Figure 2. Map showing Anloga Junction to Ejisu section of the N6 highway

Sources: Ejisu Municipal Assembly (EJMA) (2018), Oforikrom Municipal Assembly (OfMA) (2018)

The selection of the Anloga Junction to Ejisu stretch was informed by heavy encroachment in road reservations by fruit vendors, fast-food vendors, mobile-money operators, used-clothing retailers, auto-mechanics and vulcanising shops. Some of them encroach on the carriageway, making the road narrow (see Figures 3a, 3b, 3c and 3d). There are also permanent structures such as fuel filling stations and residential accommodation, guest houses and hotels in the reservation. The attractiveness of the road reservation to encroachers is due to the growth of Ejisu, Oforikrom, Oduom, the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) and other settlements along the road that have created huge markets for local businesses. In addition, encroachment reflects the shortage of land for development in those settlements. As a result of the heavy encroachment, traffic and pedestrian conflicts on the highway are frequent, especially in festive seasons. Other effects of the encroachment include congestion, flooding and road accidents.

Figure 3a. Mixture of shops and accommodation in the reservation

Figure 3b. Mixture of wood processing and accommodation in the reservation

Figure 3c. Shops in the reservation

Figure 3d. Fuel station in the reservation

Methodology

The study used a mixed-methods design, with qualitative material supported by some quantitative data. Because the public authorities do not have data on the number of encroachments in the road reservation, all the activities/encroachers were identified and counted manually by research assistants. Activities were grouped in ten clusters as follows: wood processing; metal fabrication; hotel/tourism/restaurants; fuel stations; building/construction materials; accommodation/housing; personal products (eg sale of used clothing, used footwear, hairdressing/barbering, cosmetics); vehicle washing bays; automobile repairs/sales; and household products (plastic chairs and tables). A lottery method was used to randomly select five clusters, and then up to 10% of encroachments in each of those five selected clusters were randomly selected for in-depth interviews (see Table 1).

In all, 117 encroachers were selected for interviews about how they found a place in the road reservation. Additionally, there were in-depth interviews with one high-level official as a key informant from each of the following organisations: EJMA, OfMA, Ghana Highway Authority, the Urban Roads Department, the Ejisu Traditional Authority and the Oduom Traditional Authority. Interviews with these key informants were used to test and triangulate information obtained from all the other interviews.

In order to map the existing social ties, each of the business owners in the selected clusters were asked to indicate which of four types of connections they have with the senior public officials in the three types of government institution (combining EJMA and OfMA as a single category called ‘local government’) plus the two traditional authorities (also combined for analysis). The types of connections were: family ties (F); ethnic ties (E); political party affiliations (P); and religious relations (R). Each senior official was asked the same questions. For political party ties, the local registers of members of political parties were obtained using the key informants.

For each type of tie, the percentage of people in the clusters who had such a connection with public officials was calculated. The tie was determined as being ‘Strong’ (when over 50% of the people in the cluster had such connections with public officials) or ‘Weak’ (when fewer than 50% had such connections).2 For ties among the public officials, each was also asked to indicate whether they had each type of connection with the other officials, and the response sought was ‘Yes’ or ‘No’. In order to identify ties among the selected business operators (the encroachers), a simple random sampling technique was used to select one business operator from each of the clusters, who was asked to indicate which of the ties they have with one or more people in each of the other four clusters, but not necessarily the person who had been randomly selected in that cluster, by indicating ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ to the question. The number of ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ responses was used to determine the strength of ties overall.

The quantitative data was analysed using SPSS Version 20 by cross tabulating the ties as follows: those between the encroachers and the two traditional councils and four public institutions (see Table 3); those between the public institutions and the traditional councils (see Table 4); and those among the encroachers (Table 5). The qualitative data was categorised into themes and analysed using QSR Nvivo 10 software. This was supported by content analysis of the quotes obtained from the interviews.

Findings

The research identified a wide range of stakeholders with interests in the road reservation along the Anloga Junction to Ejisu road (see Table 2). Among these interests lie what can be described as both positive and negative implications for managing urban expansion.

| Stakeholders | Interests |

|---|---|

| Ghana Highway Authority | According to the Ghana Highway Authority Act 1997 (Act 540), the authority is responsible for the administration, control, development and maintenance of trunk roads and related facilities in Ghana. Section 4 of Act 540 requires the authority to delegate the maintenance and protection of all trunk roads to local district/municipal assemblies (Republic of Ghana 1997). |

| Oforikrom Municipal Assembly (OfMA) and Ejisu Municipal Assembly (EJMA) | Under the Local Government Act 2016 (Act 936), each municipal assembly is to ensure the overall development of its municipality. By this mandate, and supported by Section 4 of Act 540, the road reservation along this section of the Kumasi–Ejisu highway falls under the control of either OfMA or EJMA (Republic of Ghana 2016). |

| Urban Roads Department | The Urban Roads Department is one of the decentralised departments in each MMDA in Ghana. The department is responsible for the maintenance of existing urban roads, providing technical road services and participating in the development of future road networks (Republic of Ghana 2016). |

| Traditional Authorities | Under the Chieftaincy Act 2008 (Act 759), chiefs are custodians (protectors) of land (Republic of Ghana 2008). In practice, they informally control the use of space in the road reservation. |

| Encroachers (businesses and other activities within the five selected activity clusters) | To operate businesses for economic gain, provide housing etc. |

The data in Table 2 suggests that there should be adequate formal rules and regulations for public institutions to prevent or at least minimise encroachment in the road reservations. Section 4 of the Ghana Highway Authority Act also provides a framework for collaboration between the Ghana Highway Authority and municipal assemblies in the management and control of road reservations. However, as discussed in the next section, in practice there are significant gaps in the formal rules, and overall they appear to be weak compared with informal ties.

Table 3 shows that informal ties connecting the sampled encroachers with traditional authorities can be described as generally strong. The two most important connections that emerged are ethnic and political party ties, with ethnic ties being the more popular. Overall, interviewees working in wood processing, petroleum products and automobile repairs/sales had the strongest ethnic connections; and wood processors and hairdressing/barbering/cosmetics dealers had the strongest political party ties with their traditional authority. Family and religious ties were not as significant (see Table 3).

Note: F-family ties; E-ethnic ties; P-political party ties; R-religious ties

*Percentage of owners in this activity cluster with this type of informal tie

For the ties connecting municipal assembly staff with the selected encroachers, it emerged also that political party and ethnic identities were strong compared to family and religious ties. Again, political party links were most significant and the encroachers who stand out here were in petroleum products, metal fabrication and automobile repairs/sales.

Highway Authority officials were also found to be strongly embedded in local society through ethnic and political party ties, especially the latter. Once again, dealers in petroleum products, metal fabrication and automobile sales/repairs had the strongest political party connections (Table 3).

Officials in the Urban Roads Departments were as strongly embedded in society as their counterparts in the Highway Authority. Similarly, the most common ties were political party and ethnic relations. Ethnic connections stand out strongly amongst encroachers in petroleum products, automobile sales/repairs and metal fabrications being key.

The study also revealed that ethnic and political party ties were the two most important connections amongst public officials covered in the study. The data in Table 4 also shows that strong ties connected traditional authorities with senior Local Government, Highway and Urban Roads officers, and all those officers to each other. Thus, all the public officials can be described as collectively strongly bonded.

Ties existing between the sampled business operators were also found to be strong, supporting the hypothesis that people need these ties (and/or connections to a public official) in order to find a place in the road reservation (see Table 5). Once again, apart from a few cases where religious affiliations were found between some of the business operators, the two most important types of connection were ethnic and political party ties.

| Petroleum products | Hairdressing, barbering, cosmetics | Metal fabrication | Automobile repairs/sales | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | E | P | R | F | E | P | R | F | E | P | R | F | E | P | R | |

| Wood processing | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Petroleum products | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | ||||

| Hairdressing, barbering, cosmetics | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | ||||||||

| Metal fabrication | No | Yes | Yes | No | ||||||||||||

Overall, there is a clear pattern showing the importance of political party and ethnic links both vertically and horizontally among actors in society. Their significance in facilitating access to a place in the road reservations is discussed below.

Discussion

The study demonstrates that informal ties matter in finding space to use in the road reservations. In-depth interviews revealed that about 80% of encroachers never thought about going to the Department of Urban Roads or the municipal assemblies to request permission to use the road reservations. In their view, these institutions did not have any power or control over access to the reservations. As one respondent said:

The person who helped me to get this place did not mention the Urban Roads, GHA or the municipal assemblies. I was led to see an individual privately although that person is a public official. I do not think any of these people [pointing to the other encroachers] will tell you anything different from what I am saying (Encroacher, August 2020).

However, space in the road reservations is strongly controlled by informal rules and one cannot just move into any space. Another interviewee dealing in metal fabrications explained how a place was found for the business as follows:

I tried a number of times at different places to find space along this road but I was not successful. People came from the palace [the residence of the traditional authority leader or the chief] to harass me and asked me to move out. I spoke to the operator of this hairdressing salon, who is our political party chairman’s wife, so she got her husband to speak with the person in the traditional authority for me to move in here. You cannot just move in anyhow; it is not possible. You need to get someone who knows another person before you can get a place (Encroacher, October 2020).

When officials in the public institutions were interviewed, one of them explained that:

All these people who have encroached on the road reservations invoked political party and ethnic affiliations in order to move into the reservations. It is difficult to think about clearing them or demolishing these structures for many reasons. It is either we know some of them on personal levels or our colleagues in the assembly and Urban Roads know them. It is these complex informal relationships which make it difficult to stop the encroachment (Public Official, October 2020).

The two senior officials interviewed in the municipal assemblies blamed the encroachment issue on the lack of clear national legislation or by-laws made by the municipal assemblies specifically to control encroachment on road reservations. One of them noted that the provisions in the Land Use and Spatial Planning Act 2016 (Act 925) are not clear about MMDAs’ mandate in controlling road reservations. This officer explained that:

This law talks about encroachment of public lands but it does not say clearly that road reservations are included. In fact, the Act 540 is also not clear on this. So it is difficult for us to respond to this problem. The encroachers use all kinds of informal ties to get in rather than using formal approaches (Public Official, October 2020).

This finding of the importance of informal ties is consistent with a statement in Ghana’s National Urban Policy Framework and Action Plan that, in the absence of formal provision of infrastructure and services, the majority of the urban population resort to informal channels for obtaining urban services (Republic of Ghana 2012).

All the interviewees narrated similar stories about the process people need to go through to find space in the road reservations: one can only find space either through knowing an official in the state directly or through a neighbour in society. The stronger their ties, the more likely a person is to find space. This confirms findings by Brinkerhoff et al. (2007), Hyden (2007), Mungiu-Pippidi (2006) and Boone (1998) that informal ties can be a strong force to shape behaviours. Public officials may be seen to control and distribute resources in favour of people with whom they have strong connections. Bribery could also be seen to facilitate the process: all the respondents mentioned that a common practice is for one who has been granted a space in the road reservations to show appreciation with a ‘thank-you gift’ in kind or cash to the public officials, and a drink to the chiefs in the traditional authority. In Ghanaian culture chiefs are only thanked with drinks and not in cash. It is however common knowledge that many of the chiefs in recent times will request the ‘drink’ to be presented in cash.

According to public officials, the importance of informal networks in the control of space in the road reservations is reinforced by factors that undermine their capacity to keep encroachers out. These are weak enforcement of existing laws; weak formal collaboration and cooperation among public institutions responsible for the prevention of encroachment; and inadequate political support from ruling governments.

The study revealed that the public institutions were not collaborating effectively to adequately enforce relevant laws. According to the Ghana Highway Authority Act 1997 (Act 540), the road sector ministry is expected to work with the local government ministry and district assemblies to control, maintain and protect trunk roads including road reservations. There was consensus among all the high-profile public officers interviewed in these public institutions that, to a large extent, each of these public institutions works in isolation. All supported a statement that:

There is weak collaboration and cooperation among our institutions responsible for the protection of the road reservations. We do not share information about our plans and strategies, so it looks like there is nobody responsible for the road reservations at all (Public Official, September 2020).

Again, this concern about weak formal collaboration was flagged over ten years ago in the government of Ghana’s National Urban Policy Framework and Action Plan (Republic of Ghana 2012, p. 17).

Another public officer suggested this weakness is partly explained by ambiguities in the laws:

Existing pieces of laws that are applicable in the protection of road reservations are also quite ambiguous. The Local Governance Act 2016 (Act 936) makes the district assembly the highest political authority. What this means is that part of the assembly’s land use planning functions must cover the use of space in the road reservations along the sections of the highways in a particular district assembly’s jurisdiction. It is on the basis of this that the assembly issues temporary permits to developments in the road reservations. The Ghana Highway Authority Act 1997 (Act 540) also mandates that the authority shall be responsible for the administration, control, development and maintenance of trunk roads and related facilities. Both laws are not clear on who should manage that stretch of trunk road passing through the districts (Public Official, August 2020).

This view appears quite legitimate. Responsibility for managing the section of a trunk road that runs through an area swallowed by urban expansion is assumed to be taken by the municipal assembly, but the Local Governance Act is not clear on this point.

The study also found inadequate political commitment to protect road reservations and prevent encroachment. The view supported by all the public officials was that encroachers invoke political party ties to protect their interests. This partly explains why public institutions find it difficult to clear encroachers, especially those who were given temporary permits but later changed their temporary structures into permanent development (refer to Figures 3a, 3b, 3c and 3d). About 20% of the encroachers claimed that they were granted permits by the municipal assemblies to conduct their businesses in the road reservations. However, according to the key informants in the public institutions, about 90% of those who were given temporary permits did not comply with the permits and built permanent structures instead. The difficulty in managing such encroachers was explained in the following terms: “You give them the temporary permit but they change it and when you want to clear them then they invoke all sorts of ties to stop you” (Public Official, July 2020).

On the other hand, the views of encroachers can be summed up as follows:

I have a permit to build this structure here. They told me that this is for road expansion so I will move out after two years. It is over eight years now and nothing has happened, so I changed it from wood to concrete and I am living in it with my family (Encroacher, July 2020).

The other key factor here is economic reality. As mentioned earlier, finding space in road reservations to start a business offers many encroachers their best opportunity to secure a livelihood and support their families. This is why many invoke all available ties to pursue their interests. This reality of the road reservations providing livelihoods points to the need for all public agencies responsible for the enforcement of road reservations regulations to rethink. The purist approach to enforcing the regulations does not appear to be reasonable or indeed possible. This will require a review of the regulations to take on a more ‘human face’, considering socio-economic factors and not only engineering requirements.

Conclusion and recommendations

Non-enforcement of relevant laws, weak formal collaboration between public institutions, inadequate political commitment to protect public land, and the economic realities of the need for encroachers to find space to start businesses and provide a source of livelihood for families, have all contributed to undermining the role of formal rules and strengthening the importance of informal ties and decision-making in the governance of space in road reservations. In these circumstances, encroachment looks set to continue with its attendant problems of congestion on the roads, accidents and socio-cultural and political constraints that block road expansion plans.

However, another economic reality is that important road reservations should not be permanently taken over by encroachers, as future road expansion will be essential to support increased transportation needs and broader economic development. Therefore, effective legal regulation working in tandem with informal ties and processes should be the focus. This would facilitate temporary developments and activities that provide livelihoods for families until the space needs to be recovered for road expansion.

To make this work, the EJMA and the OfMA should take steps to improve enforcement of temporary permits issued for activities and development in the road reservations. This could include monitoring activities through monthly field visits, annual renewal of the permits, and reminder notices to check compliance. This should be done in a transparent manner to win people’s trust and might encourage many more to go through formal channels to find and use space in the road reservation.

At the same time, all public institutions responsible for the protection of road reservations should collaborate adequately in the discharge of their mandates. Such collaboration should include traditional authorities and the operators of businesses in the road reserves so that both formal and informal processes work in tandem. This needs to be supported by transparency in the sharing of information across institutions and stronger political commitment to enforce laws that seek to protect road reservations. This applies particularly to those holding political office at the local level, including the regional minister who has oversight responsibility of the region on behalf of the president and oversees municipal chief executives and assembly members (local councillors). Increased collaboration and transparency between public institutions and with traditional authorities may well help to secure political commitment.

Clearly, successful decision-making in a complex situation such as the protection of road reservations and the interplay between the different challenges involved, calls for application of the concepts, ideals and methods of multi-stakeholder governance. Decision-making processes must identify all the stakeholders involved, understand their needs, interests, relationships and power (both formal and informal), and influence and involve them equitably. With sufficient attention to these factors, it should be possible to achieve trade-offs of interests leading to a win–win situation in the management of road reservations.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship or publication of this article.

References

Alesina, A. and Giuliano, P. (2007) The power of the family. The Institute for Labour Studies-IZA Discussion Paper No. 2750. Bonn: Institute for Labour Studies-IZA.

Balakrishnan, S. (2013) Highway urbanization and land conflicts: the challenges to decentralization in India. Pacific Affairs, 86 (4), 785–811.

Bobrowsky, D. (1999) Creating a global public policy network in the apparel industry: the apparel industry partnership. Global Public Policy Case Studies. Geneva: Global Public Policy Institute.

Boone, C. (1998) State building in the African countryside: structure and politics at the grassroots. The Journal of Development Studies, 34 (4), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220389808422527

Brempong, O. (1997) Religious background of Ghanaian society: a general survey. Research Review, 13 (1 & 2).

Brinkerhoff, D.W., Brinkerhoff, J.M. and Mcnulty, S. (2007) Decentralization and participatory local governance: a decision space analysis and application in Peru. In: Cheema, G.S. and Rondinelli, D.A. (eds.) Decentralizing governance: emerging concepts and practices, (pp. 189–211). Washington DC: World Bank.

Chazan, N. (1982) Ethnicity and politics in Ghana. Political Science Quarterly, 97 (3), 461–485. https://doi.org/10.2307/2149995.

Cobbinah, P.B. (2021) Urban resilience as an option for achieving urban sustainability in Africa. In: Home, R. (ed.) Land issues for urban governance in sub-Saharan Africa. Local and urban governance, (pp. 257–268). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-52504-0_

Cohen, A. (1966) Politics of the Kola. Some processes of tribal community formation among migrants in West African towns. Africa, 36 (1), 18–36. https://doi.org/10.2307/1158126

Crook, R.C. and Hosu-Porbley, G. (2008) Transnational communities, policy process and the politics of development: the case of Ghanaian hometown associations. Non-Governmental Public Action Programme (NGPA) Working Paper 13. London: London School of Economics.

Damina, B.G., Baji, A.J., Ubangari, Y.A. and Babarinsa, D. (2016) Violation of development control provisions by public and semipublic developers along Kachia road, Kaduna Metropolis. IOSR Journal of Environmental Science, Toxicology and Food Technology, 10 (8), 146–151. https://doi.org/10.9790/2402-100802146151

Devika, S. (2018) Remove encroachment from lands reserved for public utility purposes: Rajasthan HC. Available at: https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2018/11/02/remove-encroachment-from-lands-reserved-for-public-utility-purposes-rajasthan-hc/ [Accessed 2 September 2020].

Egwu, S., Leonard, D. and Matlosa, K. (2009) Nigerian elections since 1999: what does democracy mean? Journal of African Elections, 8, 108–144. https://doi.org/10.20940/JAE/2009/v8i1a5

Ejisu Municipal Assembly. (EJMA) (2018) Medium-term development plan [2018-2021]. (Unpublished) Ejisu: Ejisu Municipal Assembly.

Evans, P. (1995) Embedded autonomy: states and industrial transformation. Princeton: Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400821723-004

Fagernäs, S. (2006) How do family ties, boards and regulation affect pay at the top? Evidence for Indian CEOs. Centre for Business Research. Cambridge: University of Cambridge.

Fransen, L. (2012) Multi-stakeholder governance and voluntary programme interactions: legitimation politics in the institutional design of corporate social responsibility. Socio-Economic Review, 10 (1), 163–192. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwr029

Ghana Statistical Service. (2014) District analytical report. Ejisu-Juabeng Municipal Authority. Accra: Ghana Statistical Service.

Gleckman, H. (2018) Multistakeholder governance and democracy: A global challenge. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315144740

Government of Kenya. (2007) Kenya Roads Act (No. 2 of 2007). Available at: http://kenyalaw.org/kl/fileadmin/pdfdownloads/Acts/KenyaRoadsAct_No2of2007.pdf [Accessed 30 June 2023].

Government of Rwanda. (2011) Law No 55/2011 of 14/12/2011 Governing Roads in Rwanda. Official Gazette No 04 of 23/01/201233. Available at: https://www.rtda.gov.rw/fileadmin/templates/publications/Rwanda_Road_Act.pdf [Accessed 1 April 2023].

Government of Uganda. (2019) Uganda Roads Act, 2019, Act 16. Available at: https://ulii.org/akn/ug/act/2019/16/eng%402019-09-25 [Accessed 4 April 2023].

Grodeland, A.B. (2005) Informal networks and corruption in the judiciary: elite interview findings from the Czech Republic, Slovenia, Bulgaria, and Romania. World Bank Conference New Frontiers of Social Policy. 12–15 December. Arusha.

Hanson, K.T. (2004) Landscape of survival and escape: social networking and urban livelihoods in Ghana. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 37 (1), 1291–1310. https://doi.org/10.1068/a3750

Hellman, B. and Ndumbaro, L. (2002) Corruption, politics, and societal values in Tanzania: an evaluation of the Mkapa administration’s anti-corruption efforts. African Association of Political Science, 7 (1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.4314/ajps.v7i1.27322

Hyden, G. (2007) Challenges to decentralization in weak states. In: Cheema, G.S. and Rondinelli, D.A. (eds.) Decentralizing governance: emerging concepts and practices, (pp. 212–228). Washington DC: World Bank.

Independent News. (2019) Physical infrastructure committee approved road reserve expansion. Available at: https://www.independent.co.ug/physical-infrastructure-committee-approves-road-reserve-expansion/ [Accessed 15 December 2020].

International Labour Office. (2004) Working out of poverty in Ghana. The Ghana Decent Work Pilot Programme. Available at https://www.ilo.org/public/english/bureau/dwpp/download/ghana/ghbooklet.pdf [Accessed 16 July 2022].

Kariko, M.E. (2009) Factors contributing to illegal occupation and developments on alienated public land for road corridors in Kenya: the case of Nairobi Northern Bypass. MA Dissertation, University of Nairobi. Available at: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.1009.5172&rep=rep1&type=pdf [Accessed 15 December 2020].

Kaweesa, F. (2015) Managing road reserves in Uganda: a case of Kampala District. MSc Dissertation, Maker University. Available at: http://dspace.mak.ac.ug/bitstream/handle/10570/7403/Kaweesa-cobams-mpim.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [Accessed 14 August 2020].

Kimenyi, M.S. and Mbaku, J.M. (2004) Ethnicity, institutions and governance in Africa. In: Kimenyi, M.S. and Meagher, P. (eds.) Devolution and development: governance prospects in decentralizing states (pp. 105–135). England: ASHGATE Publishing Limited.

Lake Macquarie City Council. (2020) Unauthorised structures and encroachments on public lands – council policy version 1 – Draft. Available at: https://shape.lakemac.com.au/57509/widgets/294441/documents/168601 [Accessed 16 January 2021].

Law Insider. (2020) Definition of road reserve. Available at: https://www.lawinsider.com/dictionary/road-reserve [Accessed 22 December 2021].

Leonard, D. and Pitso, T. (2009) The political economy of democratization in Sierra Leone. Journal of African Elections, 8 (1), 49–70. https://doi.org/10.20940/JAE/2009/v8i1a3

Malowist, M. (1966) The social and economic stability of the Western Sudan in the Middle Ages. Past and Present, 33, 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1093/past/33.1.3

Melbourne City Council. (2003) Road encroachment operational guidelines. Available at: https://www.melbourne.vic.gov.au/SiteCollectionDocuments/road-encroachment-guidelines.doc [Accessed 2 July 2023].

Modern Ghana. (2009) GHA alarmed by encroachment on road reservations. Available at: https://www.modernghana.com/news/202089/gha-alarmed-by-encroachment-on-road-reservations.html [Accessed 30 June 2023].

Mungiu-Pippidi, A. (2006) Corruption: diagnosis and treatment. Journal of Democracy, 17 (3), 86–99. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2006.0050

New Plymouth District Council. (2011) P11-004 policy on encroachments on road reserve. Available at: https://www.npdc.govt.nz/media/hcjjdjqn/encroachments-on-road-reserve-policy.pdf [Accessed 30 June 2023].

New Vision. (2020) Accidents blamed on road reserve encroachment. Available at: https://www.newvision.co.ug/news/1324516/accidents-blamed-road-reserve-encroachment [Accessed 14 August 2020].

Oforikrom Municipal Assembly (OfMA) (2018) Medium-term development plan [2018-2021]. (Unpublished) Oforikrom: Oforikrom Municipal Assembly.

Olowu, D. and Wunsch, J.S. (eds.) (2004) Local governance in Africa: the challenges of democratic decentralization. London: Lynne Rienner Publishers, Inc.

Osei-Boateng, C. and Ampratwum, E. (2021) The informal sector in Ghana. Accra: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung (Ghana Office). Available at: https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/ghana/10496.pdf [Accessed 10 July 2022].

Owubah, C.E., Donkor, N.T. and Nsenkyire, R.D. (2000) Forest reserve encroachment: the case of Tano-Ehuro forest reserve in Western Ghana. The International Forestry Review, 2 (2), 105–111. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/42610113 [Accessed 16 December 2020].

Parra, J.C., Joseph, G. and Wodon, Q. (2016) Religion and social cooperation: results from an experiment in Ghana. DOI: 10.1596/25324. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/351981024_Religion_and_Social_Cooperation_Results_from_an_Experiment_in_Ghana [Accessed 23 July 2022].

Pharoah, R. (2016) Strengthening urban resilience in African cities: understanding and addressing urban risk. ActionAid. Available at: https://actionaid.org/sites/default/files/actionaid_2016_-_strengthening_urban_resilience.pdf [Accessed 30 March 2023].

Republic of Ghana. (1992) 1992 Constitution of the Republic of Ghana. Accra: Government Printer.

Republic of Ghana. (1993) District Assemblies’ Common Fund Act (Act 455). Accra: Ghana Publishing Corporation.

Republic of Ghana. (1997) Ghana Highway Authority Act 1997 (Act 540). Accra: Government Printer.

Republic of Ghana. (2008) Chieftaincy Act, 2008 (Act 759). Accra: Government Printer.

Republic of Ghana. (2012) National urban policy framework and action plan. Accra: Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development.

Republic of Ghana. (2016) Local Governance Act, 2016 (Act 936). Accra: Government Printer.

Rodrigue, J.P. (2020) The geography of transport systems. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429346323

Roloff, J. (2008) A life cycle model of multi‐stakeholder networks. Business Ethics: A European Review, 17 (3), 311–325. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8608.2008.00537.x

Saito, F. (2003) Decentralization and development partnerships: lessons from Uganda. Tokyo: Springer.

Sanusi, A.Y. (2006) Patterns of urban land development control in Nigeria: a case study of Minna, Niger State. Journal of the Nigerian Institute of Town Planners, 14 (1), 125–142.

Schleifer, P. (2019) Varieties of multi-stakeholder governance: selecting legitimation strategies in transnational sustainability politics. Globalizations, 16 (1), 50–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2018.1518863

Sundet, G. (2005) The 1999 Land Act and Village Land Acts: technical analysis of the practical implications of the Acts. Available at: https://mokoro.co.uk/land-rights-article/the-1999-land-act-and-the-village-land-act-a-technical-analysis-of-the-practical-implications-of-the-acts/ [Accessed 3 February 2021].

Tessema, Z. and Kahumbire, E.B. (2019) East African coastal corridor development project: Bagamoyo–Tanga -Horohoro/Lunga Lunga-Malindi Road Project: phase 1 (Kenya and Tanzania). Available at: https://www.afdb.org/sites/default/files/documents/environmental-and-social-assessments/eastern_coastal_roads_-_esia_summary_kenya_-_en.pdf [Accessed 28 June 2023].

Tignor, R.L. (1993) Political corruption in Nigeria before independence. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 31 (2), 175–202. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X00011897

Tshering, K.C. (2018) Exploring the nature of encroachment of state land in the kingdom of Bhutan. MSc Dissertation, University of Twente, Netherlands.

Ubangari, A. and Babarinsa, D. (2012) Violation of development control provisions by public and semi-public developers along Kachia Road, Kaduna Metropolis. IOSR Journal of Environmental Science, Toxicology and Food Technology, 10 (8), 146–151. https://doi.org/10.9790/2402-100802146151

Woollahra Municipal Council. (2021) Encroachment on council reserves. Available at: https://www.woollahra.nsw.gov.au/services/roads_and_footpaths/encroachments_on_council_road_reserves [Accessed 26 January 2021].

World Bank. (2001) Attacking poverty. World Development Report 2000/2001. Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Bank. (2004) Making services work for poor people. World Development Report 2004. Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Bank. (2012) Indonesia – the rise of metropolitan regions: towards inclusive and sustainable regional development. Washington, DC: World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/27231

World Bank. (2016) Urban resilience: challenges and opportunities for African cities. Available at https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2016/01/21/urban-resilience-challenges-and-opportunities-for-african-cities [Accessed 30 March 2023].

1 Larger urban districts have ‘municipal’ or ‘metropolitan’ assemblies. Collectively, local authorities are known as ‘MMDAs’.

2 A more granular scale would be preferable in future research on this topic.