Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance

Issue 28

September 2023

RESEARCH AND EVALUATION (PEER REVIEWED)

Filling the Gaps in Local Governance: An Analysis of the Structure and Process of Informal Community Governance in Ibadan, Nigeria

Femi Abiodun Olaniyan

Department of Geography, Faculty of the Social Sciences, University of Ibadan, Ibadan (200284), Nigeria

Corresponding author: Femi Abiodun Olaniyan, Department of Geography, Faculty of the Social Sciences, University of Ibadan, Ibadan (200284,) Nigeria, olaphem2004@yahoo.com

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi28.8233

Article History: Received 11/06/2022; Accepted 30/08/2023; Published 25/09/2023

Citation: Olaniyan, F. A. 2023. Filling the Gaps in Local Governance: An Analysis of the Structure and Process of Informal Community Governance in Ibadan, Nigeria. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, 28, 61–83. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi28.8233

© 2023 by the author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercial, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Abstract

The Nigerian local government system’s failure is widely documented, yet little is known about an alternative governance framework that communities have developed to tend to their needs. Using a case study methodology, this paper investigates the structure and process of informal community governance by which communities in Ibadan, Nigeria, fill in the gaps in local government. Documents and key informant interviews with community leaders provided qualitative data. The findings reveal that informal community governance systems are functioning well in Ibadan. Their governance process is open to all, participatory democracy is visible, and corruption is not tolerated. While Nigeria’s official local government structure lacks the governance and democratic culture essential for meaningful, long-term local development, this paper’s analysis shows that those features are being nurtured in the local community setting. The findings serve to draw attention to the need to institutionalise community governance as a form of local government capable of addressing a wide range of present and emerging community needs.

Keywords

Community Governance; Informal Governance; Local Government; Ibadan; Nigeria

Introduction

This paper reports on research conducted in Ibadan, Nigeria, that explored structures and processes used in informal local governance – ie non-statutory arrangements instigated and managed by communities themselves. There are huge performance gaps in formal local government in Nigeria. Ibadan communities address these gaps through arrangements for community governance that, although they lack formal legal authority, nevertheless function successfully and to a large extent replace the statutory system.

In developed countries, local governments are reasonably responsive to a wide range of existing and emergent community needs, in addition to their legislative tasks (Bush 2020). By contrast, local governments in Africa, particularly those in sub-Saharan Africa, tend to be dysfunctional and face many governance issues. Institutional incompetence (Dziva and Kabonga 2021), a lack of discretionary space (Olaniyan et al. 2020), a lack of financial transparency (Krah and Mertens 2020), incomplete political and administrative decentralisation (Lameck and Hulst 2021), and corruption (Mbandlwa et al. 2020) are among the many governance issues. This begs the question of how community needs can be served in the face of dysfunctional local government. In response, some communities in Nigeria have created alternative institutions to meet their basic needs. For example, they organise and manage security and crime prevention (Ojebode et al. 2016); are actively involved in the construction and maintenance of roads and basic health and education facilities (Oyalowo 2021); organise potable water (Fateye et al. 2021) and waste collection and disposal (Wahab 2012); and provide other infrastructure.

Given this essential role of communities in filling gaps in local governance, it is surprising that community governance in Nigeria has received so little attention from scholars and policy-makers. By contrast, in most countries community-level governance has received a lot of attention from academics and policy-makers, and in many places it has been mainstreamed into formal government processes (Acharya 2016; Putnam and Brown 2021). This is the consequence of a paradigm shift in ideas and goals about community problem-solving (Armstrong et al. 2004). The need to address a wide range of current and future community needs in more sustainable ways is growing, and this can only be realised by collective action (Shu and Wang 2021). Accountability and transparency are emphasised in community governance, as are collective action, civic involvement and local participatory democracy (Dare 2013). Thus, when it comes to promoting good governance, knowing the structure and process of local governing arrangements is critical. The governance structure and processes of a community are decisive: they can support or suppress a democratic culture, encourage or discourage citizen engagement and participation, and have a substantial impact on the distribution of decision-making authority (Van Veelen 2018).

While informal community governance in Nigeria is long-standing (Olowu and Erero 1996), little is known about its structure and process. Therefore, the objective of this study was to investigate informal community governance in Ibadan, Nigeria, and how communities there fill the gaps in local government. The term ‘informal’ is defined as referring to processes and structures which constitute a significant part of the local community context and play a substantial role there, but which are not endowed with formal legal or governmental authority.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section two presents the conceptual background, while section three describes the study area and methodology. Empirical findings are discussed in sections four and five, while section six concludes.

Conceptual framework

Meaning and unique characteristics of the community as a governance model

In the literature, there are various definitions of communities (see Cobigo et al. 2016; Cislaghi 2019). This study adopted the definition by Cobigo et al. (2016), which aims to coalesce fundamental features of communities into a single definition and reasonably depicts the notion of community in the present research context. According to Cobigo et al. (2016, p. 195), “a community is a group of people that interact and support each other and are bonded by shared experiences or characteristics, a sense of belonging, and often by their physical proximity”. This suggests that the bond among community members may be based on any or all of neighbourhood or geographical area, family connections, or other relationships (Bowles and Gintis 2002).

The community has been recognised as one of the three key governance models that have successfully managed human affairs across diverse contexts (Gu and Li 2020). Indeed, emerging scholarship suggests that communities of all kinds (including place-based neighbourhoods) now constitute important sites of political engagement in modern society (Vogl 2021). The centrality of relationships is one of the distinctive characteristics of communities as a mode of governance. Attitudes and norms, a sense of trust, a sense of belonging, and a willingness to contribute help define the community’s vertical and horizontal relations (Asteria and Herdiansyah 2022). ‘Community’ has emotional nuances, “implying familiarity, social and emotional cohesion, and commitment. It implies a degree of attachment and belonging that offers a common sense of identity” (Douglas 2010, p. 539). Members of the community are dedicated to common ideals and conventions, as well as the maximisation of collective interests through joint achievement and communal oversight of members’ actions (Gu and Li 2020). As a result, community members are aware of one another’s capacity, behaviour and needs and may hold each other accountable (Bowles and Gintis 2002). These distinctive features of the community enable it to function effectively and instil a sense of mission, resulting in a fulfilling experience for community members (VanderWeele 2019).

While the above paragraph highlights some of the remarkable traits of a community that enable it to function, the literature also identifies some characteristics that may jeopardise the community’s utility as a governance model. According to Halsall et al. (2013), communities are often homogeneous and operate on a small scale. As a consequence, it is impossible to harvest the benefits of economic diversity associated with complementarities between varied skills and other inputs (Bowles and Ginti 2002). Other researchers argue that community groups are not necessarily inclusive, and that they are more likely to be defined by selfish ambition and power tussles than by self-sacrifice and service (Van Veelen 2018; Gu and Li 2020). Nevertheless, there is strong evidence that communities continue to play an important role in addressing community needs in modern society (Wills and Harding 2021).

Understanding community governance

In its most basic form, community governance refers to government carried out by communities for the benefit of communities. It has been defined as a “process in which communities deliberate and pursue their preferred futures…” (McKinlay 1999, p. 2). This might mean that communities deliberate, determine and chart their future without external involvement. However, the term ‘governance’ implies collaboration. Fundamentally, governance is a multi-layered, multi-actor affair that has a comprehensive and integrated character (Lane and Hesselman 2017). For this reason, community governance has also been defined as “genuine collaboration between the public, private, and non-profit sectors to achieve desired outcomes for a jurisdiction, be it a neighbourhood or a whole local government area” (Pillora and McKinlay 2011, p. 14).

The extent to which formal government (central, state or municipal) and private sector interests are represented in the community governance process is a critical issue. According to the literature, community governance may or may not involve one or more of the several levels of government, civil society institutions, and private sector interests (McKinlay 1999; Totikidis et al. 2005). Governments are actively involved in community governance in most countries across Europe and America (Totikidis et al. 2005; Wills and Harding 2021), and across Asia (Acharya 2016; Zhang et al. 2021). However, in most sub-Saharan African countries, including Nigeria, community governance is essentially informal, with little or no engagement from the various levels of government (Olowu and Erero 1996; Tshishonga 2019).

While community organisations have been criticised for their lack of formality and for being small-scale and personalistic (Gallien 2020), emerging scholarship is shedding light on the positive contributions of informal community governance in addressing social needs (Urbano et al. 2021; Onuklu et al. 2021). The literature reveals that informal institutions carry out a range of governance-related tasks in various contexts, and they have immense potential to facilitate civic participation, inclusive decision-making and improved service delivery at the local level (Khan Mohmand and Mihajlovic 2014; Byrnes et al. 2016). As a result, informal community governance groups do determine development outcomes to a greater or lesser extent across many countries at the local level (Byrnes et al. 2016; Onuklu et al. 2021).

Community governance addresses a wide range of socio-economic concerns that have been largely neglected by both state and market solutions (Van Veelen 2018). It covers governance gaps caused by faults in the formal government structure (Bowles and Gintis 2002), and aims to improve community wellbeing by using human, material and social capital to address shared problems while also preparing for future demands (Armstrong et al. 2004; Totikidis et al. 2005). To summarise, the exercise of authority, accountability to the community represented, stewardship if finances are involved, leadership, and the direction and control exercised in a community are the key characteristics of community governance (Armstrong et al. 2004).

This is not to suggest that communal government does not have its flaws. The community, like the state and the market, is vulnerable to failure (Bowles and Gintis 2002). Scholars have identified social and economic marginalisation, economic differentiation, and lack of an enabling environment as factors limiting the effectiveness of community governance (Bowles and Gintis 2002; Waheduzzaman and As-Saber 2015; Acharya 2016). According to Acharya (2016), community governance in developing societies is impoverished since groups are poorly organised, have little technical resource capacity, and are economically fragile. Waheduzzaman and As-Saber (2015) found that political manipulation, clientelism and inadequate governance structures and processes are the key issues affecting communities and local governments in Bangladesh.

Study context and methodology

The city of Ibadan is found in Nigeria’s south-western region (see Figure 1). It is Nigeria’s third most populous city and the largest in terms of land area, with more than six million people living in the metropolitan region. The city’s growth is attributed to its proximity to Lagos, Nigeria’s economic nerve centre, as well as its administrative role as the capital of the former western region and the current Oyo State in Nigeria’s post-independence era (Olaniyan et al. 2020). Ibadan was founded by the Yoruba people, who dominated the western part of the country, but has since evolved into a cosmopolitan city.

Figure 1. Local government areas in Ibadan

Source: Olaniyan et al. (2020)

Ibadan lacks city-wide and metropolitan governance. As Figure 1 reveals, the core city is partitioned into five local government areas (LGAs) and the surrounding region into another six. Each LGA is further divided into wards for electoral, political and administrative purposes. Furthermore, the wards are made up of many communities, defined by common ties or shared experiences, and by identifiable geographical boundaries such as rivers, streams, roads, hills, signposts, survey lines and beacons. Given that Ibadan is a multicultural and multi-ethnic city, shared experiences among community members are mostly not based on beliefs and cultures but rather the need to address inadequate, or lack of access to basic services and social amenities. Literature suggests that such ties can bring about collective action when the needs of the community are not met (Poland and Maré 2005; Warr et al. 2017).

Methodology

In this study, the qualitative method was applied. Sixteen key informant interviews (KIIs) with community leaders were conducted in 15 purposefully chosen communities (see Table 1). One interview with a community leader was conducted in each of the 15 communities investigated, and a principal community development officer (CDO) in Akinyele LGA was also interviewed. Seven interviews were conducted in 2019, while an additional nine, including the interview with the principal CDO, were conducted in December 2022 and January 2023. As Table 1 reveals, the communities were selected across nine of the 11 LGAs that make up Ibadan. The need to capture possible variations in informal community governance structures and processes across poor, rich, and mixed-income communities informed the choice. Because of a lack of official, up-to-date population data at the community level, the estimated number of households reported by interviewees serves as a proxy for each community’s population. The lack of up-to-date, disaggregated population data is a major constraint to community-based studies in Nigeria.

Before the interviews, the author met with each of the interviewees to explain the goal of the study and how the data would be used. A semi-structured interview guide (see Appendix 1) was developed to collect information about administrative structure, leadership selection, participation, accountability and transparency, and service delivery. Information collected from documents (by-laws, constitutions, memoranda of understanding, project plans and proposals, receipts for project material and work etc) made available by interview participants supplemented the data from interviews. Such documents constitute secondary data that can be utilised to confirm or substantiate evidence from primary sources (Bowen 2009). The disadvantages of the qualitative method are widely known. Nonetheless, it is recognised as often the most suitable method for research aimed at acquiring a thorough understanding of local processes and contexts (Rivera et al. 2020). Qualitative approaches that foster stakeholder participation at smaller spatial scales, such as the community level, are particularly suggested (Feliciano and Rumbaut 2019).

*All are male, but some communities have a female vice-chair.

The context for informal community governance in Ibadan

Nigeria operates a three-tiered government structure: federal and state, plus local governments at the lowest level. These have been allocated crucial constitutional responsibilities, which include:

• the provision of appropriate services and development activities, responsive to local wishes and initiatives by devolving or delegating them to a local representative body;

• the facilitation of the exercise of democratic self-government close to the grassroots level of society, and encouragement of initiatives and leadership potential;

• the mobilisation of human and material resources through the involvement of members of the public in their local development; and

• the provision of a two-way channel of communication between local communities and government (Federal Government of Nigeria 1976; Ogunnubi 2022).

However, as previously mentioned, there is evidence that Nigerian local governments have to date failed in fulfilling their constitutional duties (Abe and Omotoso 2021; Nkwede et al. 2022), and the findings of the current study serve to bolster this claim. Growing disenchantment with the local government system is palpable across the studied communities. According to the interviewees, local governments play no significant role in community governance and are unresponsive to basic development demands. For the previous eight years, according to one interviewee, local government failed to provide any service or basic urban infrastructure in his community. Another community leader said his local government started a one-kilometre road development project in 2012, but it has yet to be completed. Interview extracts confirmed:

The local government doesn’t give us attention, except during elections. They do not provide the needed development infrastructure. Even for basic things like transformers, it’s the community that contributes money to buy them (Ifejolapo, assistant general secretary interview).

There is no benefit whatsoever from the local government. We only benefit from community self-government (Ogbere-Tioya, chairman interview).

These remarks support the conclusions reached in the literature cited above, whose authors noted that although local government in Nigeria is the closest government to the grassroots and was established to provide services needed by the people and to foster local development, the system has failed to accomplish those goals.

Alongside local governments, establishment of formal community development associations (CDAs) was pursued under Nigeria’s Third National Development Plan (1975–1988). They were to help local governments improve service delivery and quality of life by providing a means of organising and bringing the country’s communities into the fold of democratic governance (Oyalowo 2021). This included encouraging substantial physical development, acting as an institutional conduit for active citizen engagement in democratic governance, and supporting community self-reliance and the growth of social capital (Wahab 1996). CDAs become formal stakeholders in the system of government when they are recognised under State law, registered with the Ministry of Local Government and Chieftaincy, and mainstreamed into the local government structure.

As with most national policies in Nigeria, the federal government provides the broad framework for the establishment of CDAs, while the states, who are responsible for implementation, adopt the policy, and their respective legislative assemblies provide laws and guidelines for registration, duties and operations of CDAs across LGAs. For instance, in 2008 the Lagos State government passed the Community Development Associations Law to establish rules for the establishment of CDAs in each local government area in the state. The 16 sections of the law specify the minimum number of members, the registration procedures and documents, the responsibilities of local governments in relation to CDAs within their jurisdiction, the responsibilities of the anchoring ministry, and related regulations (Lagos State 2008; Oyalowo 2021). Nevertheless, despite this legislative provision, empirical evidence indicates that CDAs in Lagos State are not accorded their deserved formal status by local governments because they are seen as rivals (Muse and Narsiah 2015).

With respect to Ibadan, the present study found that Oyo State has adopted the national policy on CDAs: they are recognised by the Oyo State government, and community development offices have been established in all local governments. All forms of community associations, notably landlord associations, resident associations, or landlord and tenant associations, are regarded by the state and local governments as CDAs and may register as such. However, there was no documentary evidence (eg state laws specifying CDAs’ roles, functions and objectives) to show that CDAs are effectively mainstreamed into the local government structure in the state.

The interview with the principal community development officer (CDO) attests to this. When asked if there is any legislative act or framework for CDAs in the state, he remarked that:

I am not aware of anything like that. Maybe I can inquire about that. The only thing I know is that we have a body called the Community Development Council. The committee is recognised by the state (principal CDO interview).

Community development councils (CDCs) comprise representatives of CDAs and local government administrators. According to the principal CDO interviewed, the local government often acts on the instruction of the state government to conduct elections to choose some of the community representatives to serve as executives who coordinate the affairs of the CDC. The council meets monthly, and it is at this meeting that concerns of CDAs are tabled and discussed, while information from the state and federal governments is also communicated to community representatives. Nevertheless, this study found that 8 of the 15 communities studied are not represented at the CDC because they have not registered with the local government. The principal CDO (the only formal local government officer interviewed in this study) confirmed this fact. He explained the reason why many communities are not registered:

I have met some community leaders who wanted to buy transformers for their communities through their contributions. Some of their executives brought out their building plans as collateral to seek a loan from a bank to purchase a transformer. So what will I say to convince them to come and register with the local government? Most of them will say that for all they have been doing, they have not received any help from the government. It is through self-help. But we encourage them (principal CDO interview).

The principal CDO also mentioned, however, that communities may be obliged to register because proof of registration with the local government is a crucial prerequisite for opening bank accounts.

Given the apparent failure of statutory local governments and the lack of a legislated framework to formalise CDAs, a huge void in local governance exists which is largely being filled by informal arrangements across constituent communities, with virtually no meaningful support from their local government. The principal CDO confirmed this: “Even in this CDA, if you look at the arrangement, they have come together through their community effort; it’s not the government that organises them” (principal CDO interview).

Structures and processes of informal community governance in Ibadan

Administrative arrangements

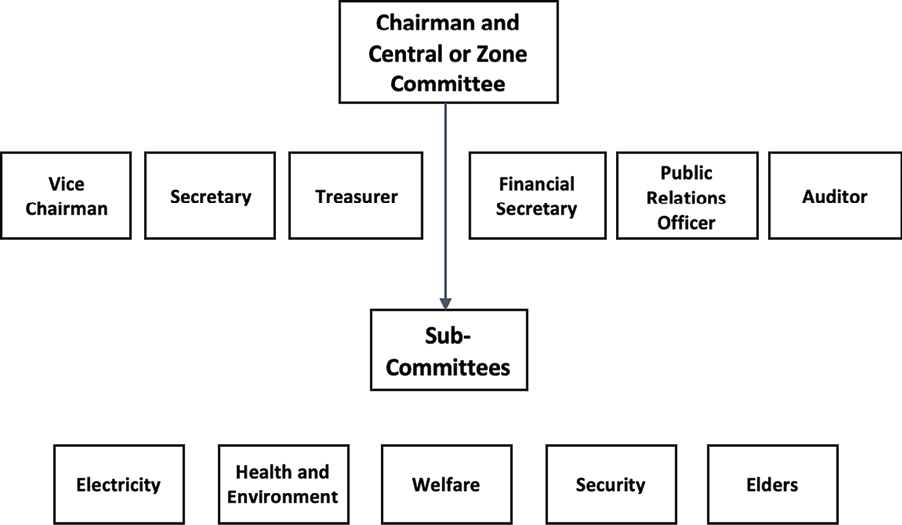

Figure 2 depicts the administrative structure of a typical ‘informal’ (ie non-statutory) community administration in Ibadan. In six of the communities studied (see Table 2), the structure is further decentralised into zones for ease of administration, with chairs and committees at both central and zone level. Each zone is typically made up of between 50 and 100 households, depending on community size. In large communities, a central working committee (CWC) is formed, consisting of an elected or appointed chairman, vice chairman, secretary, and two other community members from each zone. It may have several sub-committees, as also shown in Figure 2. The CWC is in charge of resource mobilisation and project implementation for large-scale, capital-intensive projects that are typically beyond the zones’ capacity to undertake independently.

Figure 2. Typical structure of informal community governance organisation

Source: Author’s interviews with community leaders

Exceptions: # Leaders are selected by a committee of elders * The governance structure does not exist or has collapsed + The local government is involved in the management of the estate

The CWC appears to have the highest authority in major decision-making, as the Boripe-Bashorun community chairman indicated:

We decentralise for ease of administration. In the past, we used to meet centrally. At the end of the month, we meet, but we now rotate the meetings. Each zone has executives. If anything happens in any zone, they solve it and settle it, but if it’s too knotty for them to handle, they come to the centre (Boripe-Bashorun, chairman interview).

Each zone’s administrative structure is similar to that at the central level. The chairman, vice chairman, secretary, finance secretary, treasurer, auditor and public relations officer (PRO) are community members elected or appointed to administrative positions. Membership of sub-committees is by request and is determined by professional skills and experience. Most of the communities investigated, for example, had an electricity committee led by engineers or other experts in the field; a health and environment committee led by medical experts; and a security committee led by active or retired security officers. The sub-committees are responsible for coordinating and managing the delivery and maintenance of basic community services and infrastructure. The elders’ committee, which may or may not include traditional rulers depending on whether the community is traditional or modern, gives counsel and encourages peace within and among communities. In the Ogbere-Tioya community, for instance, elders play the role of adjudicators, and all disputes are resolved by the elders within the community without the intervention of the police. The chairman of the community remarked: “We have elders in the community who settle disputes, so we don’t take dispute resolution to the police. Those who disobey this role are sanctioned” (Ogbere-Tioya, chairman interview).

Except for Mapo and Oje communities, where this type of governance structure does not exist or has collapsed, all of the communities assessed have full and functional administrative structures for informal community governance. The structure in Mapo crumbled when the executives were removed from office because they were found to be corrupt and no longer accountable to community members. At the time of the interviews the Mapo community was being run by a committee of elders made up of compound leaders. The eldest member of each compound is in charge of it, and also represents it at the general meeting of the committee of elders. In the study context, a ‘compound’ is defined as two or more households residing in the same building; or distinct flats inside a compound. One of the elders who was interviewed claimed that they were working hard to reconstruct the community governance structure that had disintegrated.

Rules and constitutions

To facilitate good governance, the majority of the researched communities have adopted constitutions or written rules. Communities write and ratify their own constitutions: neither the local government nor the state government participates in or aids the process. A typical constitution contains several articles including, among others: the declaration, name and location of the community; membership eligibility criteria; member rights and privileges; governance and operational structure; election procedures; executive composition and responsibilities; executive tenure; and discipline. Six of the studied communities have written constitutions; seven do not but do have written rules and regulations; and two have neither a written constitution nor rules and regulations. The Ifejolapo community’s assistant general secretary stated: “We don’t have written constitutions, but the rules are obeyed because it’s common knowledge for every member of the community” (Ifejolapo, assistant general secretary interview).

The research found that most communities that have written constitutions include serving and retired legal practitioners (lawyers, judges), serving and retired professors, civil servants, and other professionals as landlords or tenants. These capable members of the community are engaged in drafting and review of the constitution. Usually, draft copies are circulated among members of the community before a meeting is held to consider the constitution, and people are expected to make their observations and suggestions known at the meeting. Thereafter, if the content is agreed as satisfactory, the constitution is adopted. The research further revealed that compliance with community rules and regulations is enforced, and those who disobey are sanctioned. A former executive member of the Amuloko community indicated that the official police community relations council (PCRC) plays an important role in this regard. Most communities are members of the PCRC and meet monthly to discuss security issues. In most communities, erring members are reported to the PCRC, which helps in the enforcement of compliance and sanctions.

Leadership selection

Table 2 indicates that in most of the communities investigated informal community governance executives are elected by ballot. The exceptions are Oke-Ayo community, Federal Ministry of Works Quarters, Oke-Ibadan and Apapa Estate, where they are selected by a committee of elders. According to interviewees, proven integrity and a genuine willingness to assist in the growth of the community are the main selection criteria. In communities where executives are elected by ballot, all eligible members of the community can vote and be voted for. In these communities, the constitution mandates the formation of an electoral committee at least one or two months before the election. Two of the interviewees explained:

In our constitution, there is a provision for how leaders will be elected. By election, through a ballot. Two months before the election, we begin to remind ourselves that the tenure of the serving executives will soon end. At the central meeting, the outgoing chairman dissolves the excos and constitutes a three-man electoral committee. The committee will then call for nominations for the available positions, and those nominated will contest the election. This is how we have been doing it, and we’ve not had issues... It’s been smoothly coordinated (Boripe-Bashorun, chairman interview).

We select a transition committee two months before the election among community members. We also constitute an electoral committee that works with the transition committee to conduct elections. The committee then hands over to the winner after the election (Ogbere-Tioya, chairman interview).

All services rendered by elected or appointed executives attract no pecuniary benefit whatsoever. Services rendered are deemed voluntary, and as members’ contributions to the development of the community. An elected executive typically serves a two- to four-year term, but the constitution may provide for re-election based on performance. However, executives in the Oke-Ayo and Ifejolapo communities could serve for ten years or more if they continue to demonstrate proven honesty and accountability to the community. A dearth of competent community members with leadership skills emerged as an important reason why the tenures of selected or elected executives are elongated.

Participation, accountability and transparency

In all of the communities surveyed, the governing process encourages meaningful participation and engagement from all members of the community. Every member of the community is considered a stakeholder, and their participation is seen as crucial in deciding the community’s preferred future. Using a range of methods, including physical meetings and social media, members of the community are brought up to date on community developments. Each household is represented by a male or female adult at the weekly, monthly or bimonthly community meetings. The responsibility of the household representatives is to inform all members of the household of the meeting’s decisions. Furthermore, the PRO uses many forms of media, including social media, to communicate the specifics of any decision reached to the full membership of the community.

The formal weekly, monthly or bimonthly community meeting is a crucial platform for leaders to report on their work. The chairman and all sub-committees, including the financial secretary, provide reports for inspection and questioning by the members. The first meeting in January and the last meeting in December are crucial sessions during which more detailed reports are delivered. In January, the chairman submits annual plans and budgets for approval at the general meeting, while in December the financial secretary and treasurer provide an audited statement of account. In most communities, there are three signatories for every account, and approval has to be sought before any financial transaction is sealed.

Therefore, by and large, the governance process was found to ensure that leaders are accountable to the community that elected or selected them, and that in most communities their dealings are open and transparent. One of the interviewees commented:

We are accountable to the people. We audit our account every three months. Retired civil servants with experience handle the auditing. Before I came on board, we had issues because the accounts were not audited when they were due. An audit report is usually circulated for consideration at the zonal meeting before the central meeting. At the central meeting, each zone presents a report, questions are asked, and issues are addressed. As a result, there is no problem with accountability at all (Boripe-Bashorun, chairman interview).

Service delivery and funding sources

In the research area, inadequate or non-existent access to basic services and social amenities is a shared experience. Thus, effective coordination of essential service delivery by sub-committees is a top concern. Among other things, communities participate in waste collection and disposal in collaboration with private waste collection and disposal companies, as well as the supervision and delivery of health and security services, borehole and well drilling, road construction and maintenance, and the acquisition and installation of electricity transformers, poles and cables (Figures 3–6).

Figures 3-6. Community infrastructure funded and provided by community development associations

However, community-purchased electrical equipment (transformers, electric poles, wires and so forth) becomes the property of the power distribution company almost immediately it is erected. Interviewees voiced considerable concern about this phenomenon, but they are constrained by the fact that any attempt to resist will result in the entire community’s electricity being cut off by the power company:

Are we supposed to provide facilities for their services? All we pray for is an alternative to this comatose and dysfunctional electricity distribution company. The community buys poles, wires and cables, but they don’t refund the money to us. Don’t you see that we are being cheated? It’s serious cheating! (Boripe-Bashorun, chairman interview).

In most cases, community committee executives are responsible for contracting companies that render services. Typically, company representatives are invited to a meeting where issues are addressed before any deal is sealed. However, where the state government already has a working arrangement with contractors through public–private sector cooperation, companies are contracted through the relevant government agency. Waste collection and disposal is a case in point, where waste collection companies have been assigned to some communities by the state government.

In terms of revenue, a significant percentage of funds are generated internally, for example through security, electricity, and social and health levies. As mentioned earlier, all forms of community associations and organisations may be recognised as CDAs, although many are not registered with the state ministry and local government. Since CDAs have the authority to raise funds for the implementation of community projects and activities, informal community governance may leverage this authority to help finance its activities. Importantly, most community members show a real sense of commitment to the development of their communities. They willingly contribute monetary and other resources because of the positive impact the community governance arrangement has had on filling the local government gaps and meeting their basic needs for social services. In addition, the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund and the World Health Organization have assisted some communities with water and educational facilities. Politicians also make donations to promote development initiatives during election campaigns, presumably to entice voters.

Strengths and weaknesses of informal governance relative to local governments

Despite its many successes, several factors that undermine the effectiveness of informal community governance were identified during interviews. First, some communities suffer from a lack of competent people to take up leadership positions, which as noted earlier is one reason why they opt for selection of leaders rather than elections, and why some leaders serve for many years. An interviewee remarked that: “Many don’t merit leadership positions, and if people make the wrong choice, the community is done for” (Boripe-Bashorun, chairman interview). Selection, instead of election, of leaders goes against best democratic practices and may not be sustainable in the long run. Some of the studied communities have decided to revert to elections, Ogbere-Tioya being a case in point. The chairman said:

In the past, it was by selection. But the community saw the need for changes and then decided to go by election; it’s the process that led to my emergence as chairman [for my] first term in office, and my second term was also by election (Ogbere-Tioya, chairman interview).

The research also found that internal acrimony and cleavages may reduce cooperation among community members and undermine the effectiveness of informal community governance. For instance, in one of the studied communities, new members did not attend meetings regularly because of an allegation of sidelining by old members. They were angry because their suggestions at community meetings were often discounted. Also, discord between community members who are landlords and those who are tenants often ensues when funds are raised through levies. For example, in one of the studied communities, tenants saw landlords as more financially capable because they own properties, and believed they should therefore contribute more than tenants. In one case, this issue was delaying the purchase of a transformer.

Nevertheless, despite these weaknesses the governing process in most communities investigated was generally found to be transparent, with true participatory democracy and zero tolerance for corruption. Hence, leaders are accountable and responsive to their communities’ needs. By contrast, corruption and lack of a strong governance apparatus that can force leaders to accept responsibility and account for their actions have undermined the ability of statutory local governments to provide basic services to constituent communities. According to extant research, Nigeria’s statutory local government system is actually an enabler of corruption and corrodes the culture of accountability and openness (Hassan and Iwuamadi 2018; Nkwede et al. 2022). Huge sums have been allocated to local governments in the past three decades from central government, yet there has been no appreciable improvement in the wellbeing of the populace (Nwaodike and Ayodele 2016).

Therefore, even though Nigeria has experienced almost two decades of uninterrupted democratic rule, processes at all levels, and especially local government, often fail to reflect the ideal of good governance (Hyacinth 2021). The local government system has been in crisis for a long time, and studies have consistently linked previous reforms and their consequences to underlying structural problems (Hassan and Iwuamadi 2018; Olaniyan et al. 2020). Yet, despite the clear failure of Nigeria’s statutory local governments, no policy interest has been expressed in developing a future system based on a community governance model.

These issues are not confined to Nigeria. Previous research has found that Africa’s governance structures are typically top-down and elitist, with popular interaction and participation undervalued (Muna and Babamaragana 2021; Fateye et al. 2021). And Muna and Babamaragana’s (2021) recent empirical findings from both Nigeria and Kenya demonstrate that policy and legal frameworks for actively engaging communities in governance are not backed by actual actions. As a result, there is increasing dissatisfaction with governance processes at all levels, notably local government.

Conclusion

This study explored how communities in Ibadan, Nigeria, address the gaps in the formal local government system through informal community governance. By conducting the first empirical analysis of informal community governance in Ibadan, the research adds a fresh perspective to the growing body of literature on this topic. The KII interviews conducted with community leaders show that there is a functioning structure and process of informal community governance by which communities in the study area meet their needs. This form of governance is necessary because there is no framework for the effective operation of formal CDAs.

The study’s findings draw attention to the imperative of effectively institutionalising community governance in Nigeria, emphasising how crucial it is to give communities more opportunities to engage in local administration. Currently, CDAs have limited authority and are directly under the control of local governments that are themselves dysfunctional. If institutionalised, community governance as it operates in Ibadan offers a broad-based platform for collective action, participatory democracy, accountability and transparency – all of which are critical components of good governance for long-term local development. In the main, the analysis serves to demonstrate that, although good governance and the democratic culture needed to foster impactful, sustainable local development are lacking in the statutory local government system, they are being nurtured in the community context. Hence, the community governance model offers a potentially more viable framework for local governance in the longer term. However, moving in that direction would necessitate both constitutional reform and a major restructuring of the current local government system.

In drawing these conclusions, the present study has some limitations that must not be discounted. First, it was limited to a single city’s urban and peri-urban communities. Variations in informal community governance patterns between rural and urban areas, as well as within and across the regions of Nigeria, have not been taken into account. Further research is required to determine how other settings differ from or are comparable to the Ibadan situation, and the extent and significance of these variations. The study’s reliance on key informant interviews (KIIs) is its second weakness. Adding focus group discussions (FGDs) would have enabled a wider representation of diverse community demographics and perspectives. Using both KIIs and FGDs would strengthen future studies.

Finally, effective community governance requires a supportive institutional and political environment. Therefore, there is a pressing need for research into the formal and informal institutional factors that support or undermine community governance. Such studies are required to develop an appropriate framework for mainstreaming community governance into the broader system of government in Nigeria and ultimately to determine the most appropriate model. This would include investigations into the political will and capacity of national, state and local governments to carry out needed reform – not only to institutionalise community governance but also to address the contextual root causes of statutory local government’s current deficiencies, so that it can play a necessary complementary role when community governance is eventually institutionalised.

Acknowledgements

The editors of the Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance are greatly appreciated by the author for undertaking a preliminary evaluation of the paper’s early draft. The anonymous reviewers also provided very insightful comments, for which I am grateful. R.O. Adigun of the Department of Geography, University of Ibadan, who helped in establishing links with community leaders, and Emmanuel Ajiboye, my undergraduate student, who assisted during fieldwork, are both gratefully acknowledged. Many thanks to the community leaders who, in spite of their busy schedules, agreed to interviews.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship or publication of this article.

References

Abe, T. and Omotoso, F. (2021) Local government/governance system in Nigeria. In: Ajayi, R. and Fashagba, J.Y. (eds.) Nigerian Politics, (pp. 185–216). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-50509-7_9

Acharya, K.K. (2016) Determinants of community governance for effective basic service delivery in Nepal. Dhaulagiri Journal of Sociology and Anthropology, 10, 166–201. https://doi.org/10.3126/dsaj.v10i0.15885

Armstrong, A., Francis, R. and Totikidis, V. (2004) Managing community governance: determinants and inhibitors. Paper presented at the 18th ANZAM Conference, 8-11 December 2004, Dunedin, New Zealand (Unpublished).

Asteria, D. and Herdiansyah, H. (2022) The role of women in managing waste banks and supporting waste management in local communities. Community Development Journal, 57 (1), 74–92. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bsaa025

Bowen, A. (2009) Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal, 9 (2), 27–40. https://doi.org/10.3316/QRJ0902027

Bowles, S. and Gintis, H. (2002) Social capital and community governance. The Economic Journal, 112 (483), 419–436. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0297.00077

Bush, J. (2020) The role of local government greening policies in the transition towards nature-based cities. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 35, 35–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2020.01.015

Byrnes, L., Brown, C., Wagner, L. and Foster, J. (2016) Reviewing the viability of renewable energy in community electrification: the case of remote Western Australian communities. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 59, 470–481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2015.12.273

Cislaghi, B. (2019) The potential of a community-led approach to changing harmful gender norms in low- and middle-income countries. ALIGN: Advanced Learning and Innovation on Gender Norms. Available at: https://www.alignplatform.org/sites/default/files/2019-01/community_led_approach_report.pdf

Cobigo, V., Martin, L. and Mcheimech, R. (2016) Understanding community. Canadian Journal of Disability Studies, 5 (4), 181–203. https://doi.org/10.15353/cjds.v5i4.318

Dare, M. (2013) Localism in practice: insights from two Tasmanian case studies. Policy Studies, 34 (5–6), 592–611. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2013.863572

Douglas, H. (2010) Types of community. In: Anheier, H.K. and Toepler, S. (eds.) International encyclopedia of civil society, (pp. 539–544). New York: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1108/09504121011091015

Dziva, C. and Kabonga, I. (2021) Opportunities and challenges for local government institutions in localising sustainable development goals in Zimbabwe. In: Nhamo, G., Togo, M. and Dube, K. (eds.) Sustainable Development Goals for Society Vol. 1 (pp. 219–233). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-70948-8_15

Fateye, T.B., Odunfa, V.O., Ibisola, A.S. and Ibuoye, A.A. (2021) Basic residential neighbourhood infrastructure financing in Nigeria’s urban cities: a community development association (CDA)-based approach. Journal of Infrastructure, Policy, and Development, 5 (1), 1242. https://doi.org/10.24294/jipd.v5i1.1242

Federal Government of Nigeria. (1976) Guidelines for the reform of local government in Nigeria. Lagos: Federal Government Press.

Feliciano, C. and Rumbaut, R.G. (2019) The evolution of ethnic identity from adolescence to middle adulthood: the case of the immigrant second generation. Emerging Adulthood, 7 (2), 85–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696818805342

Gallien, M. (2020) Informal institutions and the regulation of smuggling in North Africa. Perspectives on Politics, 18 (2), 492–508. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592719001026

Gu, E. and Li, L. (2020) Crippled community governance and suppressed scientific and professional communities: a critical assessment of failed early warning for the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Journal of Chinese Governance, 5 (2), 160–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/23812346.2020.1740468

Halsall, J., Oberoi, R., Cooke, I.G. and Wankhade, P. (2013) Understanding community governance: a global perspective. International Journal of Asian Social Science, 3 (5), pp. 1111–1127.

Hassan, I. and Iwuamadi, K.C. (2018) Decentralization, governance, and corruption at the local level: evidence from Nigeria. Available at: https://www.africaportal.org/publications/decentralization-governance-and-corruption-local-level-evidence-nigeria [Accessed 17 February 2019].

Hyacinth, I.N. (2021) Party primaries and the quest for accountability in governance in Nigeria. Canadian Social Science, 17 (1), 30–37. https://doi.org/10.3968/11625

Khan Mohmand, S. and Mihajlovic, S.M. (2014) Connecting citizens to the state: informal local governance institutions in the Western Balkans. IDS Bulletin, 45 (5), 81–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/1759-5436.12106

Krah, R.D.Y. and Mertens, G. (2020) Transparency in local governments: patterns and practices of the twenty-first century. State and Local Government Review, 52 (3), 200–213. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160323X20970245

Lagos State. (2008) Community Development Associations Law. Nigeria. Available at: https://laws.lawnigeria.com/2019/04/03/community[Accessed 11August 2023].

Lameck, W.U. and Hulst, R. (2021) Upward and downward accountability in local government: the decentralisation of agricultural extension services in Tanzania. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, (25), 20–39. https//doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi25.6472

Lane, L. and Hesselman, M.M.E. (2017) Governing disasters: embracing human rights in a multi-level, multi-duty bearer disaster governance landscape. Politics and Governance, 5 (2), 93–104. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v5i2.899

Mbandlwa, Z., Dorasamy, N. and Fagbadebo, O. (2020) Leadership challenges in the South African local government system. Journal of Critical Reviews, 7 (13), 1642–1653. https://doi.org/10.31838/jcr.07.13.25

McKinlay, P. (1999) Understanding community governance. Special Interest Group on Community Governance at the 1999 Local Government New Zealand Conference, Wellington.

Muna, W. and Babamaragana, L.A. (2021) Governance without participation: a comparative perspective of the policies of Nigerian and Kenyan political parties. In: Tella, O. (ed.) A sleeping giant? (pp. 113–127). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-73375-9_9

Muse, S.A. and Narsiah, S. (2015) The politics of participatory budgeting in Nigeria: a case study of community development associations (CDAs). Journal of Human Ecology, 50 (3), 263– 269. https://doi.org/10.1080/09709274.2015.11906884

Nkwede, J.O., Moliki, A.O., Dauda, K.O. and Orija, O.A. (2022) The role of leadership in governance and development crises at the grassroots level: insights from Ijebu North local government area, Ogun State, Nigeria. In: Oloruntoba, S.O. (ed.) The political economy of colonialism and nation-building in Nigeria, (pp. 297–324). Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-73875-4_16

Nwaodike, N. and Ayodele, C. (2016) Corrupt practices in Nigeria’s local government: a critical perspective. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 21 (08), 6–11. https://doi.org/10.9790/0837-2108040611

Ogunnubi, O. (2022) Decentralisation and local governance in Nigeria: issues, challenges, and prospects. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, (27), 5–16. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi27.7935

Ojebode, A., Ojebuyi, B.R., Onyechi, N.J., Oladapo, O., Oyedele, O.J. and Fadipe, I.A. (2016) Explaining the effectiveness of community-based crime prevention practices in Ibadan, Nigeria. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies.

Olaniyan, F.A., Adelekan, I.O. and Nwokocha, E.E. (2020) The role of local governments in reducing disaster losses and vulnerabilities in Ibadan City, Nigeria. Urban Africa Risk Knowledge Working Paper. Available at: https://www.urbanark.org/role-local-governments-reducing-disaster-losses-and-vulnerabilities-ibadan-city-nigeria [Accessed 12 April 2021].

Olowu, D. and Erero, J. (1996) Governance of Nigeria’s villages and cities through indigenous institutions. African Rural and Urban Studies, 3 (1), 99–121.

Onuklu, A., Hill, T.T., Darendeli, I.S. and Genc, O.F. (2021) Poison or antidote: how subnational informal institutions exacerbate and ameliorate institutional voids. Journal of International Management, 27 (1), 100806. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intman.2020.100806

Oyalowo, B. (2021) Community development associations in low-income and informal communities in Nigeria. Available at: https://ng.boell.org/sites/default/files/2021-09/Community%20Development%20Associations%20in%20Low-Income%20and%20Informal%20Communities%20in%20Nigeria.pdf [Accessed 15 January 2022].

Pillora, S. and McKinlay, P. (2011) Local government and community governance: a literature review. Working Paper. Australian Centre of Excellence for Local Government.

Poland, M. and Maré, D.C. (2005) Defining geographic communities. Moto Working Paper. https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.911070

Putnam, T. and Brown, D. (2021) Grassroots retrofit: community governance and residential energy transitions in the United Kingdom. Energy Research & Social Science, 78, 1022–1022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2021.102102

Rivera, J., Ceesay, A.A. and Sillah, A. (2020) Challenges to disaster risk management in The Gambia: a preliminary investigation of the disaster management system’s structure. Progress in Disaster Science, 6, 100075. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pdisas.2020.100075

Shu, Q. and Wang, Y. (2021) Collaborative leadership, collective action, and community governance against public health crises under uncertainty: a case study of the Quanjingwan community in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18 (2), 598. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020598

Totikidis, V., Armstrong, A. and Francis, R. (2005) The concept of community governance: a preliminary review. Paper presented at the GovNet Conference, Monash University, Melbourne, 28–30th November, 2005. Available at: https://vuir.vu.edu.au/955/ [Accessed 23 August 2020].

Tshishonga, N.S. (2019) Youth participation and representation in community governance at Cato Manor Township, Durban. In: Kurebwa, J and Dodo, O. (eds.) Participation of young people in governance processes in Africa, (pp. 268–295). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-9388-1.ch013

Urbano, D., Felix, C. and Aparicio, S. (2021) Informal institutions and leadership behaviour in a developing country: a comparison between rural and urban areas. Journal of Business Research, 132, 544–556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.04.073

VanderWeele, T.J. (2019) Measures of community well-being: a template. International Journal of Community Well-Being, 2 (3), 253–275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42413-019-00036-8

Van Veelen, B. (2018) Negotiating energy democracy in practice: governance processes in community energy projects. Environmental Politics, 27 (4), 644–665. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2018.1427824

Vogl, T.M. (2021) Artificial intelligence in local government: enabling artificial intelligence for good governance in UK Local Authorities. Working Paper. Oxford Commission on AI & Good Governance. https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3840222

Wahab, B.O. (1996) Community development associations and self-reliance: the case of Isalu local community development union, Iseyin, Nigeria. In: Blunt, P. and Warren, M.D. (eds.) Indigenous organizations and development, (pp. 56–66). London: Intermediate Technology Publications.

Wahab, S. (2012) The role of social capital in community-based urban solid waste management: case studies from Ibadan metropolis, Nigeria. PhD thesis, University of Waterloo, Ontario, Canada.

Waheduzzaman, W. and As-Saber, S. (2015) Community participation and local governance in Bangladesh. Australian Journal of Political Science, 50 (1), 128–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/10361146.2014.989194

Warr, D., Davern, M., Mann, R. and Gunn, L. (2017) Diversifying experiences of community and the implications for addressing place-based poverty. Urban Policy and Research, 35 (2), 150–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/08111146.2015.1135791

Wills, J. and Harding, C (2021) Community town centres. Available at: https://centreforlondon.org/publication/town-centres [Accessed 18 September 2023].

Zhang, L., Zhao, J. and Dong, W. (2021) Street‐level bureaucrats as policy entrepreneurs: action strategies for flexible community governance in China. Public Administration, 99 (3), 469–483. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12730

Appendix 1

Key Informant interview guide

Thank you for taking the time to grant this interview today. The goal of this interview is to discuss the structure and process of informal community governance through which communities in Ibadan, Nigeria, fill in the gaps in local governance. The interview will take approximately 45 minutes. I would like to record this interview for data analysis and to ensure all your comments are captured correctly. Kindly speak up while the interview is being recorded so we do not miss your comments.

All your responses will be treated with the utmost confidentiality, and care will be taken to ensure that any information included in the articles to be published does not identify you as the respondent. Remember, you do not have to give any information you are not comfortable with. You are also free to end the interview at any time.

Please do not hesitate to ask any questions about the information I have just provided you regarding the interview.

Interview questions

1. Could you please introduce yourself? (Probe for education background, occupation, specific leadership role, etc.).

2. Please describe your community.

3. How are the affairs of your community coordinated? (Probe if through CDAs, traditional authority, both, or any other form of informal community governance arrangement).

4. If CDA, are you registered with the local government? If not, why are you not registered?

5. How were your community governance arrangements put in place? (Probe for whom and with what assistance; who provided the necessary support to set them up?) Were NGOs local or state governments involved or helpful at all?).

6. Do you have constitutions and other rules under which community governance operates in your community? (Probe for how the constitution was drafted and the key actors).

7. Please describe the structure of local governance in your community (probe for leadership positions, e.g., chairman, secretary, treasurer, committees, elders).

8. Kindly describe the process of community governance arrangements (probe for how and when meetings are held, how decisions reached meetings are communicated, and how members of the communities are carried along in the process of governance).

9. What specific role do elders or traditional rulers play in the community governance arrangement?

10. How are the leaders selected or elected? (Probe for who runs the ballot if leaders are elected by ballot).

11. Are the leaders accountable to the community? (Probe how and if there are sanctions for erring or corrupt leaders).

12. Who is responsible for the provision of basic facilities and services in your community? (Probe for the role of LG).

13. If your community, how do you raise resources, raise funds, and mobilise human resources to execute projects and provide facilities and services?

14. How are the companies that provide services (e.g., waste disposal, electricity, and water) for communities contracted, and by whom?

15. How would you describe the relationship between local governments and your community in local governance?

16. What are the challenges you are faced with in the running of the informal community governance arrangement?

Closing

Are there any other crucial issues I have not covered today that you would like to bring up?

I appreciate your time.