Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance

Issue 26

May 2022

RESEARCH AND EVALUATION (PEER REVIEWED)

Visualising the Invisible: Collaborative Approaches to Local-Level Resilient Development in the Pacific Islands Region

Rebecca McNaught

Cities Research Institute, Griffith University, Queensland, Australia 4222,

rebecca.mcnaught2@griffithuni.edu.au

Kalara McGregor

Centre for Planetary Health and Food Security, Griffith University, Queensland, Australia 4111, kalara.mcgregor@griffithuni.edu.au

Matthew Kensen

Pacific Centre for Environment and Sustainable Development, The University of the South Pacific, Suva, Fiji Islands, kensen60@gmail.com

Rob Hales

Griffith Business School, Griffith University, Southport, Australia 4215, r.hales@griffith.edu.au

Johanna Nalau

Cities Research Institute, Griffith University, Queensland, Australia 4222, j.nalau@griffith.edu.au

Corresponding author: Rebecca McNaught, Cities Research Institute, Griffith University, Queensland, Australia 4222, rebecca.mcnaught2@griffithuni.edu.au

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi26.8189

Article History: Received 06/02/2022; Accepted 01/05/2022; Published 31/05/2022

Citation: McNaught, R., McGregor, K., Kensen, M., Hales, R., Nalau, J. 2022. Visualising the Invisible: Collaborative Approaches to Local-Level Resilient Development in the Pacific Islands Region. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, 26, 28–52. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi26.8189

© 2022 by the author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

(CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties

to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the

material for any purpose, even commercial, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Abstract

The Pacific Islands region has made strong progress on the integration of climate change, disaster management and development frameworks, particularly via the Pacific Urban Agenda and the Framework for Resilient Development in the Pacific. These frameworks highlight the need for local- level collaboration in achieving ambitious pathways for climate- and disaster-resilient development. However, to date little research has investigated the role that local-level collaboration plays in implementation. Additionally, there is a lack of guidance on how to design and implement local-level collaboration that is informed by in-country practitioner experiences. This study addresses those gaps. Its findings indicate that in the Pacific collaborative attributes span individuals, institutions, collaborative arrangements, and broader governance systems. They also suggest that the skills needed to undertake collaboration well at the local level are, in part, already manifest in Pacific cultures as invisible skill sets. More can be done to make the invisible visible by documenting and developing the ‘soft skills’ that are necessary to achieve climate- and disaster-resilient development. This action could contribute to bridging the gap between ambition and reality.

Keywords

Collaborative Governance; Pacific; Disaster; Climate Change; Local Governance; Resilient Development

Introduction

In 2015, a range of global agreements and frameworks emerged that highlighted the need for integrated, collaborative and localised approaches to implementing sustainable development.1 These policy advances demonstrated a growing movement towards utilising sustainable development ‘pathways’ as the starting point for integrating disaster and climate change considerations (Goklany 2007; Singh and Chudasama 2021). However, their goals also represent a global burden of expectation on sub-national actors to work collaboratively to ‘leave no-one behind’ and essentially, to deliver an effective form of climate- and disaster-resilient development.

The Pacific Islands region has been at the forefront of efforts to better integrate climate change and disaster risk management with broader development planning and implementation (Hay 2021; Nalau et al. 2016). Pacific policy documents at regional and national levels highlight the need for local-level collaboration to achieve these ambitious pathways for resilient development. For example, the Framework for Resilient Development in the Pacific (FRDP) states that the achievement of its goals will depend upon good governance and effective partnerships (Pacific Community et al. 2016, p. 3). In addition, participants of the 2019 Pacific Urban Forum committed through the Pacific Urban Agenda to forming a ‘coalition of the willing’ and noted that “forming action-oriented partnerships at all levels should be considered” (UN-Habitat et al. 2019, p. 3). These global and regional policies are reflected nationally through urban development, joint climate change and disaster risk management, and national sustainable development plans.

Local governance actors have an important role to play in implementing these national, regional and global policies (United Nations Development Programme 2016), yet they often remain resource-poor, especially in the Pacific Islands (Kiddle et al. 2017). Local governance is by no means limited to local governments: civil society and private sector actors also bring strengths that can be harnessed for ‘bottom up’ climate- and disaster-resilient development, especially in Pacific urban spaces (Phillips and Keen 2016; Jones and Sanderson 2017). Foukona (2017) argues that in the Pacific context “the starting point is to find ways to forge partnerships, negotiation platforms, and more inclusive processes between the states, other stakeholders, and customary landowners to address pressing planning and development issues” (p. 2).

Collaborative forms of governance, hereafter referred to as ‘collaborative governance’, emerged out of practice-based experiences of managing complex environmental and public policy issues (Ansell and Gash 2007). While there are many definitions and frameworks for collaborative governance (eg Ansell and Gash 2007; Emerson et al. 2012; Feiock 2013), the concept encapsulates public policy-making across “public, private and civic spheres” to achieve public outcomes that could not otherwise be achieved (Emerson et al. 2012, p. 2). Collaborative governance provides a promising option for pooling resources and reducing funding dependence (Kalesnikaite 2019), yet little is ever systematically captured about how collaboration unfolds in practice, especially in the Pacific Islands region. As a result, the region has limited representation in the collaborative governance literature (see Eldridge et al. 2018). Additionally, little is known about how collaborative approaches enhance the effectiveness of local-level climate- and disaster-resilient development, particularly in such culturally rich and geographically diverse settings as small island states. Likewise, there is a lack of context-specific guidance, based on the experiences of in-country practitioners, on options for the design and implementation of local-level collaboration for resilience. While there is a broad existing literature on de-centred and community governance of climate change and disasters in the Pacific, this paper explicitly centres on investigating an inclusive approach to governing public policy. It therefore aims to fill the gap in the local governance, resilience and collaborative governance fields of research through a cross-country study on local-level collaborative practice across the Pacific Islands, and to answer the following key research question:

What are the characteristics and outcomes of collaborative governance in local-level climate- and disaster-resilient development in the Pacific Islands region, and which factors enhance its effectiveness?

In answering this question, the study seeks to expand collaborative governance theory based on broader geographical and cultural contexts and provide a basis for extending the application of policy and collaborative practice in the region. Using local governance as the centre of analysis and combining notions of collaborative governance and climate- and disaster-resilient development, it aims to understand how local governance actors use collaboration to achieve policy outcomes. In doing so, the researchers seek to determine the specific conditions, design, processes and outcomes of localised collaborative governance (Ansell and Gash 2007).

Locating this research within the Pacific Islands region

The Pacific Ocean is the largest body of water in the world and the combined Exclusive Economic Zones of all Pacific Island states and territories cover an area of 30 million km2 (Hay 2021; see Figure 1). This ocean represents interconnected histories of transport, cultural ties, spirituality and large ocean resources such as fisheries (Mailelegaoi 2017). The Pacific Islands region is highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change and disasters. Four Pacific Island countries are listed within the top ten most at-risk countries in the world, with Vanuatu the most at-risk of all (Comes et al. 2016). The region also faces growing climate and disaster risks through changes to average conditions and increasing extreme events such as heavy rainstorms and more intense cyclones (Australian Bureau of Meteorology and Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation 2014). A shifting climate has far-reaching implications for economies, health, agriculture, security, tourism and infrastructure (IPCC 2022).

Figure 1. The Pacific Islands region, comprising 14 independent states and 8 dependent territories

Source: Pacific Community (2022) (reproduced with permission)

Trends in local governance

Currently up to 50% of Pacific Island populations live in urban areas and towns (Hassall et al. 2019). In many of the larger Pacific Island countries, citizens reside on insecure land holdings on the urban periphery with inadequate access to basic services, resulting in minimal economic opportunities and increasing exposure to natural hazards such as cyclones and floods, as well as poor air quality (Keen and Connell 2019; Trundle et al. 2019; Campbell 2019; McEvoy et al. 2020). Despite a range of issues confronting urban dwellers, urban and peri-urban areas are economic hubs for countries and are the centre for medical, political, and administrative needs (Hassall et al. 2019). Much of this economic activity is informal. In Papua New Guinea for example, the informal sector produces up to 80% of GDP (Government of Papua New Guinea 2019). As the impacts of climate change increase in magnitude and frequency, impacts such as sea level rise and strong cyclones may intensify the push towards living in urban centres.

This urban drift has been a concern for island administrations. For example, the Fijian government has enacted policies to decentralise services and create ‘growth centres’ (Government of Fiji 2017) to encourage populations to remain in rural areas. While rural development policies in the Pacific Islands have had variable effect, the global COVID-19 health pandemic has had the most dramatic impact in reversing rural–urban migration, particularly in tourism-dependent island economies. For example, Fiji and Vanuatu have seen a rapid outflux of urban residents, either formerly employed in the tourism sector (Connell 2021) or studying at tertiary institutions (Kuruleca 2021, personal communication), returning to home islands and villages. Scholars highlight a range of impacts on rural communities of this influx, from increased pressure on communally held resources (Connell 2021), to opportunities to rejuvenate relationships with culture and land (Scheyvens and Movono 2020).

Local governance is extremely varied across the region. It has been examined from a range of perspectives, including themes of land tenure (Foukona and Allen 2017), gender and social safeguards (Fairbairn-Dunlop 2005; Tuimaleali’ifano 2006; Hukula 2017), locally managed marine areas (Jupiter et al. 2017) and community-based climate change adaptation (Dumaru 2010). Governing at a scale other than the local level is a relatively new concept in the Pacific Islands. Before colonisation and state governance, traditional governing structures occurred mostly at the village/tribe/family level (Wairiu 2006; Hassall et al. 2019). Since the designation of nation states, a variety of statutory local governance mechanisms have been instigated across the region, sometimes fusing with traditional systems. The duality of state and traditional governance in the Pacific Islands has been dubbed a ‘bird with two wings’ (Forsyth 2009). This intersection is complex, with influences such as globalisation, religion and migration all playing a part (Madraiwiwi 2006; Wairiu 2006).

Status and roles of local governance actors in the region

Despite policy expectations on local-level actors, many cities and local governments in the Pacific Islands are severely resource-constrained (Kiddle et al. 2017; Keen and Connell 2019; Nunn and McNamara 2019). There are also significant institutional and resource-related barriers for local government across the region. Local governments often lack technical skills, such as urban planners in towns and cities, to implement their obligations (UN-Habitat et al. 2019). This skills shortage can be compounded by forced retirement, overseas work prospects and the lure of higher paid jobs outside government. Moreover, the flow of donor funding to local governance development has decreased markedly in the past decade as development partners increasingly prioritise the capacity development of central governments (Manley et al. 2016). In addition, “few Pacific leaders have come to terms with the reality of an urban Pacific and the need to manage cities” (Keen and Barbara 2015, p. 1). Perhaps as a result, urbanisation has also failed to gain traction as an issue at the regional level and lacks a formal place in regional governance architecture (Taylor 2019). In essence, there is a mismatch between the policy emphasis on local governance and the current status and capacity of local governments and urban management.

Despite these constraints, local-level governance plays an important role in realising global goals. Local governance actors are key duty-bearers for ‘on-the-ground’ implementation of central government policies and, increasingly, sustainable development (Meadowcroft 2011). They are also the level of governance most likely to interact closely with citizens (Stout and Love 2017; Kalesnikaite 2019). Many of the responsibilities of local government also intersect with realising climate- and disaster-resilient development. Town and city marketplaces, often administered by local governments, present the opportunity for a ‘trifecta’ of climate change adaptation, economic development and disaster risk reduction, especially for women (McNamara et al. 2020). Local government roles also include: facilitating the interface between customary/traditional governance and state governance arrangements; creating and maintaining green spaces; planning-related responsibilities (such as building permits); and undertaking waste management (UN-Habitat et al. 2019). Urban governance issues also need to be addressed to minimise social tensions (Keen and Barbara 2015).

In summary, mobilisation of local-level governance actors is an important factor in realising climate- and disaster-resilient development, yet there are severe constraints, including economic, regulatory and technical barriers to local actors undertaking this role. Manley et al. (2016) highlight the priority of investing in strengthening local government and community leadership and governance. The need for scholarly attention at this level has been noted (Hassall and Tipu 2008).

Defining climate- and disaster-resilient development

For some time, a significant body of academic literature has supported the need to integrate sustainable development with climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction (Schipper and Pelling 2006; Hay and Mimura 2013; Kelman et al. 2015; Fankhauser and Stern 2016), and has advocated for a more “climate-compatible” form of development (Mitchell and Maxwell 2010, p. 1). Recent reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC (2022) also highlight governance as a key determinant of collective capacity to adapt to a changing climate. From an international development perspective, researchers note the prevalence of describing the intersection between climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction, poverty reduction and development as ‘climate- and disaster- resilient development’ – a “catch-all for tackling climate change impacts in a development context” (Bahadur et al. 2013, p. 2).

More recently, Singh and Chudasama (2021) conceptualise climate-resilient development (CRD) as an approach that embraces mitigation, adaptation and inclusive sustainable development to advance planetary health and wellbeing for all. Singh and Chudasama highlight four enabling conditions for advancing climate-resilient development: a) ethics, values and worldviews; b) partnerships and commitment to finance and technology by governments; c) actors and arenas of engagement (across local to global scales); and d) innovations. While these findings do not offer anything particularly new in terms of solutions, the research is an important demonstration of how an integrated development approach can be conceptualised, and the interdependence of sectors, stakeholders and levels of governance in achieving it. As mentioned in the introduction, both the Framework for Resilient Development in the Pacific and the Pacific Urban Forum have embodied climate- and disaster-resilient development as a defining concept and goal.

Methodology

The ‘embedded’ ethnographic approach underpinning this study (Yin 2003) is recommended by collaborative governance theorists Ansell and Gash (2007) to develop “greater insight into the nonlinear aspects of the collaborative process” (p. 562). As such, the research drew upon a range of methods to enable the triangulation of findings, including an extensive narrative literature review, semi-structured interviews, and involvement in online and in-person events. Also, this study benefitted greatly from the involvement of two Pacific Island co-authors (Kalara McGregor and Matthew Kensen), whose combined knowledge and experience of Pacific culture, local governance and disaster resilience contexts assisted in designing and undertaking interviews, coding and analysis. The first author also kept a research diary for the period 2019–2021, drawing upon academic and practice reflections on the subject matter of this paper (Sharpe 2004).

The narrative literature review was undertaken on the separate topics of local governance in the Pacific context, collaborative and adaptive governance (in order to provide a theoretical framework), and climate and disaster resilience. Academic literature was consulted via a cross-section of online databases – EBSCO Host (Business Source Complete), The Web of Science (Core Collection) and Scopus – reflecting an interdisciplinary approach to investigating intersecting topics.

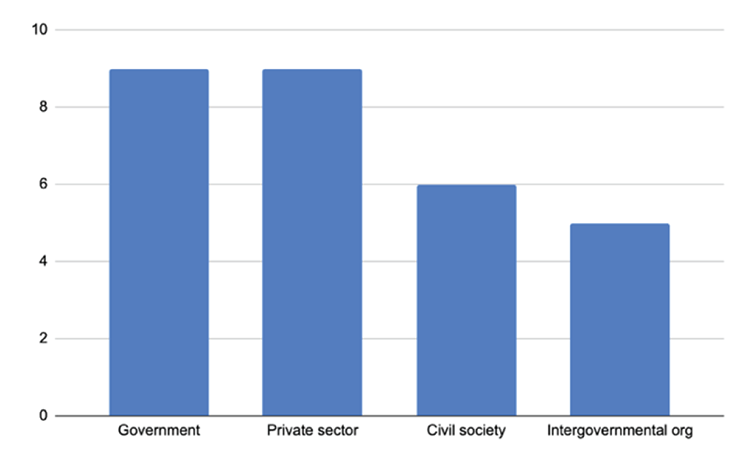

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 17 key informants, all of whom have a long association with local governance in the Pacific Islands region: a form of elite interviewing (Marschan-Piekkari et al. 2004). Rather than investigate one example or country, interviewees were selected based on geographical and gender diversity, stakeholder types, country contexts and levels of governance. To adapt to a severely constrained COVID-19 environment, most interactions took place online (Archibald et al. 2019), drawing upon author networks and a snowballing sample selection method. Interviewees were from a range of Pacific Islands Forum countries from Melanesia, Polynesia and Micronesia (Fiji, Vanuatu, Samoa, Kiribati and Cook Islands), as well as Australia. In addition to these countries, webinars also collected reflections from participants in the Marshall Islands, Solomon Islands and Tuvalu. The interviewees represented a cross-section of stakeholders from the private sector, civil society and different levels of government (national and local). Many have held positions across multiple stakeholder groups (Figure 2). To maintain confidentiality,2 interview participants are indicated as ‘P’, webinar contributions as ‘W’ and insights gleaned from in-person events as ‘E’, with a number indicating the specific person/webinar/event that the information refers to.

Figure 2. Breadth of past and present experience from 17 interviewees (29 occurrences)

Interviews and events were captured using Zoom and Microsoft Teams and transcribed using Otter.ai. Thirteen interviews were undertaken in English given the high English proficiency of interviewees. Four were undertaken in Bislama and translated by the third author. Qualitative data analysis involved a process of data reduction, data display and conclusion drawing/verification during and post data collection (Miles and Huberman 1994). This process was supported by NVIVO 12 qualitative data analysis software, including inductive and deductive coding (Fereday and Muir-Cochrane 2006). Interviews were undertaken by three researchers using a detailed interview guide derived from the framework outlined in Table 1 (below) and coded by the first two authors using the same framework, who shared and cross-checked results. All interview participants were given the opportunity to verify preliminary findings.

Analytical framework: adaptive and collaborative governance

This research draws upon theories of both adaptive governance (Dietz et al. 2003; Folke et al. 2005) and collaborative governance (Ansell and Gash 2007; Emerson et al. 2012) as a lens through which to investigate the practice of local-level collaboration. Broadly speaking, public administration and governance-related disciplines provide a useful foundation for research on climate- and disaster-resilient development because they have a longer history than disaster and climate-change-related fields (Catrien et al. 2017). Adaptive governance theory emerged from considering cross-border challenges such as natural resource management and climate change (Folke et al. 2005), but is now being applied to disaster risk management and health disciplines (Ruane 2020). These challenges share complexity, inter-jurisdictional relevance, and the need to engage a broad range of stakeholders in creating solutions. Adaptive governance incorporates at least four dimensions: social learning or knowledge co-production; multiple levels and scales (polycentricity); self-reflective practice (reflexivity); and collaboration or co-management (Boyd and Folke 2011; Ruane 2020). It also emphasises adopting information and learning from previous management responses (such as disasters) as a means of adaptivity (Juhola 2011; Ruane 2020). This paper frames collaborative governance through a detailed examination of the ‘collaboration’ subset of adaptive governance.

The collaborative governance model of Ansell and Gash (2007) includes identification of the starting conditions, design, process and outcomes of collaborative governance. This framing matches well with the particular problem of this research project, in that there is a lack of collaborative governance literature in the Pacific Islands region and this study aims to reveal the basic mechanics of collaborative processes that are currently being used, who is using them and why, and their perceived effectiveness. A summary of the key elements of this framework, with the addition of a ‘systems’ component outlined by Emerson et al. (2012), is outlined in Table 1. Further detail has been added based on this study’s literature review.

Although Ansell and Gash’s (2007) theory was developed based on 137 collaborative governance case studies from a range of disciplines, the authors themselves note the overrepresentation of the United States of America in their sample, and there is underrepresentation of developing countries in their reference list. This reflects the broader collaborative governance literature in that many studies are based on resource-rich countries. This research seeks to address that gap in the literature in the results and discussion that follow.

| Key components of collaborative governance | Key considerations emerging from the literature review |

|---|---|

| 1. Starting conditions |

|

| 2. Design |

|

| 3. Process |

|

| 4. Outcomes |

|

| 5. System |

|

Results

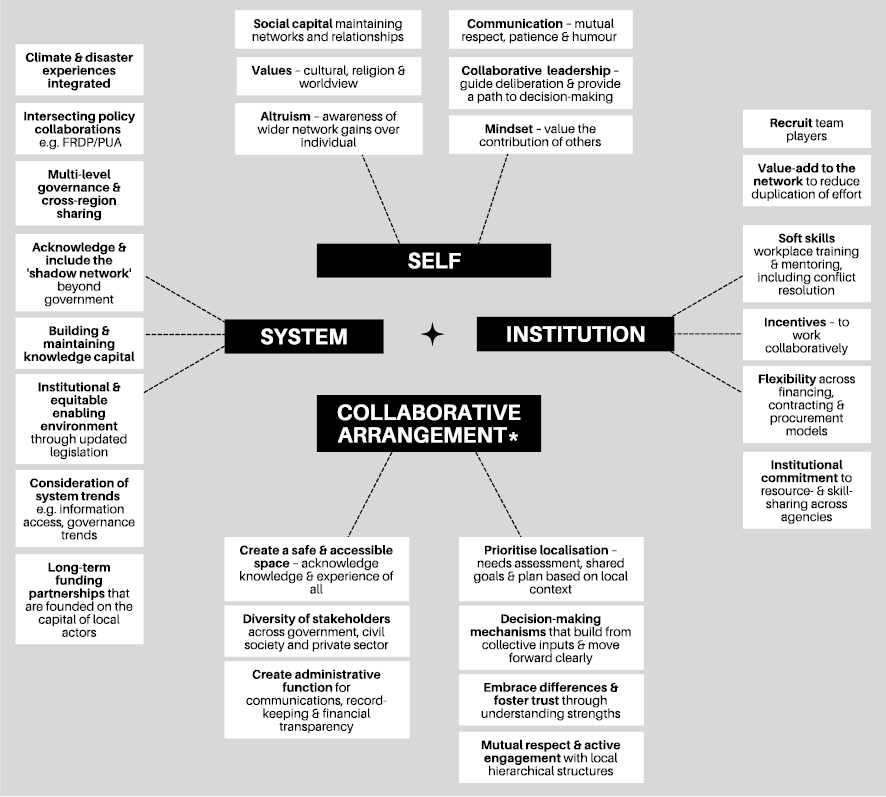

Using collaborative governance theory as an analytical framework, the following results summarise the key characteristics and outcomes of local-level collaboration for resilient development in the Pacific Islands region. Results also reveal a range of factors that are key to enhancing the effectiveness of local-level collaboration and are demonstrated in Figure 3.

Starting conditions

Motivations

Respondents highlighted that collaborative partners were motivated by a common goal or shared belief in outcomes, such as co-creating solutions to a shared problem, while simultaneously holding their own organisational self-interests or motivations (P3, P4, P6, P16). Self-reliance (P14, P16) and benefits of shared expertise (P8, P9) were also motivations. One respondent noted that some organisations need to see ‘proof of concept’ before being motivated, which requires a visionary to begin the process (P13). Specific examples of motivations include addressing the needs of vulnerable groups (P6), reaching remote villages (P7), supporting community development (P10), “getting things moving” (E1), and enhancing “how development is done” (P4).

Power

The ‘power’ category had the highest number of responses under the ‘starting conditions’ component. In some cases, power is used ‘wisely’ and for a purpose that links back to achieving the vision and core values of an organisation or collaboration (P8, P16). For example, civil society organisations that are embedded within formal disaster management arrangements use this power for improving the distribution of resources to those most in need (P12).

In some cases, the ‘vertical’ use of power has detrimental impacts on local-level collaboration. For example, in some Pacific Island countries the national government’s desire for control renders local governments inactive due to fear of making a mis-step (P1). National governments were also seen as absorbing a large amount of funding from donors, which denied local initiatives access to funds and stripped them of power to act. This lack of funding-related power has led local-level food security collaborations to innovate (P15). Another respondent emphasised that sharing of power can be challenging, but that there was a need for governments to ‘let go’ and empower the private sector and civil society to contribute to public policy solutions (P3).

Some stakeholder groups can dominate others in local-level collaborations; for example women may be less likely to speak up at the local level than the national level (P4, W1). Facilitators have found ways to balance the need to respect traditional authority (which is often male-driven) with enabling the inclusion of women’s perspectives. Examples include ‘redesigning the table’ by creating small women-only breakout groups (P2, P13, P14, W3, or empowering women to navigate and support existing decision-making mechanisms (P9, W3). Another facilitator noted that by splitting members of a town-based coalition into smaller groups participants got to know each other and the younger participants could start to feel confident to voice their opinions (P2). Others noted that having representation of men and women on collaborative teams has helped bring together different working and leadership styles (P3, P9, P15). Women responded that they have grown their ability to influence partnership settings through broadening their network, gaining trust from experience in senior roles, and demonstrating commitment and passion for the issue being addressed (P13, P15).

Prehistory3

Prehistory can be a determinant of success at the community and local level. For example, one person’s previous negative history with a community can undermine the collaborative efforts of all organisations involved in a partnership. In the longer-term historical context, the impact of colonial interruption continues to permeate the organisation and structures of cities and partnerships in the Pacific Islands region (P11, W1), though re-examination of these dynamics is evident (W1, W3).

Design

Types and participation

There are a multitude of approaches and experiences that are being drawn upon with the aim of increasing resilience and enhancing the participation of stakeholders and citizens in the Pacific Islands region. These include coalitions; city–citizen interactions; private/public or private/civil society partnership; more permanent and formally legislated platforms; informal and more temporary groupings that are geographically based (such as within a particular city or island); and arrangements focused on specific problems, policy development and/or implementation. Examples also included private sector businesses working with traditional governance to address common problems and religious organisations partnering with the local private sector. Many of these arrangements contained working groups which enabled a select number of organisations to work together in a more targeted way. Many collaborations begin informally, shifting to formal over time.4

Ground rules

Respondents emphasised the need to clarify roles in a collaboration through understanding each organisation’s expertise and unique contribution (P9). Objective-setting (P17, W3), measuring impact and enabling inclusion (W3) were all seen as important precursors to successful collaboration.

Process

Leadership or meta-governance

Leadership was defined as including the ability to bring different groups/perspectives together to understand needs and resources; and as treating everyone equally and helping people resolve issues (P2, P3, P5, P7). Leadership was also seen to require a deep understanding of context and culture (P9) and to be guided by local expertise and experiences: “You need someone who’s well connected on all levels” (P15). In some cases, it was recommended that a coordinator be employed to ensure that collaboration is effective (P6). The importance of leaders having strong communication skills, including being able to hold conversations with a diverse range of people, was mentioned often (P9, P7, P5, P4, P3, P12, W3). One webinar participant highlighted that Pacific leaders are very skilful at managing different interest groups and a diversity of partners: “It is part of life in the Pacific. You build relationships, you build obligations, you receive, you give, and we build long-term relationships” (W1). One respondent noted that having leaders home in-country during COVID-19 led to prompt decision-making, progressing collaborative efforts (P13).

Key components of the process – ‘what they did’

Approaches used by partners to achieve their collective aims were analysed by the authors and divided into six categories presented in Table 2.

| Overarching approach | Examples of approaches used by partners |

|---|---|

| Participation |

|

| Formal decision-making |

|

| Planning |

|

| Knowledge/communication |

|

| Resource-sharing |

|

| Implementation |

|

Outcomes

Benefits/positive outcomes

Broadly speaking, beneficial or positive outcomes fell into five categories, each illustrated by examples from respondents below. Interestingly, no interviewees spoke of individual benefits from collaboration. This is in stark contrast to the broader collaborative governance literature and reflects the Pacific tendency to think and act communally (Rhodes 2014).

| Outcome category | Specific outcome examples given by respondents |

|---|---|

| Contributing to addressing the focus issues |

|

| Sharing/inspiring others |

|

| Enhancing relationships |

|

| Organisational benefits |

|

| Social equity |

|

Challenges/negative outcomes

Challenges or negative outcomes of collaborative processes were divided into three broad categories, elaborated in Table 4 below. The challenge category attracted the greatest frequency of responses under broader outcomes.

Conflict

Respondents were largely in agreement that although some form of conflict or disagreement was inevitable, it could be worked through. Respondents offered a myriad of solutions for resolving differences, including compromise to avoid paralysis, getting to know each other through listening to each other’s perspectives, having an ‘umpire’ who is a good moderator, using traditional governance and church leaders to address conflict, careful preparation before going out to communities to work collaboratively, having clear roles and responsibilities, using evidence-based decision-making, and respecting the authority of higher-ranking team members.

System interactions

Almost all respondents highlighted the interaction between collaborative practice and Pacific Island cultures and religions. The study findings confirmed their ability to draw upon and value their own knowledge, experiences, values and traditions (P9, P12, P16). “We have the land, we have the sea, we have our faith. And we have a lot of traditional knowledge. So, for me, it was using that and marrying it with new information, new training, new concepts. I believe that we had all the core ingredients to start with” (P16). Respondents also stressed the importance of knowledge of local context to work creatively on collaboration: “If you know how to work within that cultural setting, you have the opportunity to try new things” (P17). Faith-based organisations were also seen as very influential in local development planning, vaccinations, food security and humanitarian assistance.

Donors were reported to be highly variable in their approaches to partnerships in the region. Respondents emphasised the lack of sustainability brought about by ‘fly in fly out’ solutions – projects led by staff in capital cities or international consultants who may not always have the appropriate contextual understanding. These approaches tended to be associated with funding modalities that have predetermined priorities, tight timeframes, low flexibility and an unwillingness to invest in organisations already in outer island or provincial locations (P11, P12, P15). Shifts in donor priorities can result in organisations at the national and regional levels chasing funds rather than pursuing issues (P16). A lack of donors interested in engaging with informal settlements and urban issues was seen as problematic (P11, E1, W4, W6). However, donors who placed value on Pacific culture in interactions and partnerships were seen to “get it right time and time again” (P14).

Past geological and weather-related disasters such as tsunamis and cyclones have generated lessons and evolved collaborative disaster governance within the Pacific Islands region. “It takes a lot of disasters for us to learn together, to work together. The only way to become successful in our response is to work together and depend on one another” (P12). In other words, climate change is expediting collaborative practice out of necessity. The COVID-19 pandemic has also highlighted the complexity and challenges associated with local governance responding to rapidly changing needs, but also the resourcefulness of the Pacific Islands region (P13): “COVID-19 has demonstrated the importance of local decision-making, drawing upon the resources that are there – the spiritual, social, financial; the land – and using it efficiently to keep families healthier” (P16).

Factors enhancing the effectiveness of local-level collaboration in the Pacific Islands region

Respondents placed a high degree of emphasis on discussing the skills and approaches that are necessary to facilitate local-level collaboration for resilience. The study’s findings suggest that in the Pacific Islands region these key components exist under four domains of scale: self, institution, collaborative arrangement and system (represented in Figure 3). Each domain contains sub-components of factors that were deemed by research participants to be necessary for enhancing the success of collaborative efforts. Figure 3 exemplifies why individuals who are practising and upskilling themselves and others in collaborative leadership at a local level also need to be supported by wider institutional and systems-based measures to maximise impact. Yet, these results also reveal that despite an absence of Pacific-specific guidance on local-level collaboration for resilience, the region is rich in experience, knowledge and practice.

Figure 3. Factors deemed to enhance the effectiveness of local-level collaboration for resilience

*The phrase ‘collaborative arrangement’ denotes a formal or informal mechanism that enables diverse stakeholders to address a common issue/goal.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to determine the characteristics and outcomes of collaboration in local-level climate- and disaster-resilient development in the Pacific region. It also sought to determine which factors enhance the effectiveness of such collaboration. This discussion highlights key insights from the research results, compares these insights to existing theory, and suggests practice implications and study limitations. Consequently, collaborative governance theory is expanded according to broader geographical and cultural contexts.

Previous participatory governance literature (eg Mansuri and Rao 2013) cautions that collaborative governance arrangements may be redundant approaches in fledgling states due to a lack of well-resourced state governance infrastructure. However, despite weaknesses in state infrastructure in the Pacific Islands, the broad range of systemic attributes outlined in the results of this research demonstrates that the region is practising a version of collaborative governance that draws upon a vast ‘shadow network’ of support (Olsson et al. 2006). Collectively, civil society, international organisations, citizens and private sector actors at multiple levels represent a vast network beyond the state that shapes, influences, innovates, resources, and creates impact at the local level. This polycentricity confirms the attributes of adaptive governance in the Pacific Islands region. This finding is supported by the recent work of Trundle in the Solomon Islands (2020) and earlier work of Aylett (2010) in South Africa, who argue the need for greater interactions between the formal and informal governance of urban centres.

‘Self’-related attributes of cultural and religious values, collaborative leadership and maintaining networks and relationships align with the findings of existing climate- and disaster-related scholarship in the Pacific (eg Warrick et al. 2017; Parsons et al. 2018). However, some respondents cautioned that trends in individualism are drawing people away from community collaboration, indicating the importance of documenting practices. Culture-based social capital is not emphasised in Ansell and Gash’s (2007) collaborative governance theory. More recently, however, collaborative governance has been explained through a broader cultural lens in Korea, entwined with Confucian teachings (Lee and Bae 2019). This study demonstrates that collaborative governance is highly influenced by cultural context, which is likely to determine the key attributes of collaborative theory place by place.

Collaborative governance theory, to date, also fails to acknowledge the gendered dimensions influencing collaborative practice (Johnston 2017). By contrast, this study highlights the importance of ensuring diverse voices are heard in collective decision-making. Culturally sensitive solutions to women’s engagement in decision-making have been found in the Pacific literature to increase community resilience outcomes (McNamara et al. 2020; Singh et al. 2022). Existing collaborative governance literature also emphasises that being sensitive to and creating spaces for the participation of diverse groups is a necessary attribute of collaborative leadership (Lindsay 2018; Schneider et al. 2020). Advancing gender equality while being respectful of customs, hierarchies, values and religion is characteristic of the Pacific (Fairbairn-Dunlop 2005; Spark et al. 2021).

Another significant finding of this study is that many collaborations were funding- or project-based, rather than long-term arrangements. Donor and international organisation approaches to supporting local-level collaboration for resilience varied significantly. This divergence was often highlighted by respondents who valued long-term and localised partnership approaches. Previous Pacific-based literature has found that a focus on short-term, reactive adaptation can detract from longer term, more sustainable and transformational outcomes (Nunn and McNamara 2019). This points towards the need for longer-term partnerships and resourcing. Donors also have a duty to act ethically, and work towards improved localisation and ownership of solutions.

Respondents emphasised options for how institutions, including governments, can support the practice of collaborative leadership through the incorporation of collaborative practice into key performance indicators for staff. Building the confidence of local government staff (including urban planners) to apply a range of community engagement approaches would work towards ensuring a more participatory form of governance. Respondents emphasised that this is particularly important for designing public spaces and infrastructure that reflect diverse needs. Skills gaps in the public service could also be addressed through collaboration with local consultants, as recently advocated by Nailatikau and Goulding (2021).

The interview results demonstrate that there is in fact a complex body of polycentric collaborative governance practice in the Pacific Islands that draws heavily on the existing social capital of the region. This is occurring with the support of a shadow network featuring a multitude of actors and a rich, context-specific cultural and religious practice of collaboration. Pacific Island knowledge, experiences, values and traditions are significant assets to collaborative practice. Nevertheless, challenges raised by respondents indicate the need for greater deliberate reflection on collaborative practice in the region.

Limitations of this study and future research areas

Despite yielding a wide range of findings, this study reflects only a limited sample of perspectives across Pacific Island countries. Similar studies need to be undertaken at a national scale in a broader range of Pacific Island contexts. Specific sector- and gender-related lenses on collaborative governance may also yield deeper results. The navigation of research during a global pandemic affected the ability of authors to travel and interview respondents in person and prevented access to some in-country events. Authors needed to be sensitive to respondents’ availability due to compounding disasters (such as COVID-19 outbreaks and cyclones), which ruled out some planned interviews.

Conclusion

This study has examined local-level collaborative governance in the Pacific Islands region using a range of methods. It concludes that the broad characteristics of collaborative governance for local-level resilient development in the Pacific Islands region span the domains of self, institutions, collaborative arrangements and systems. The study’s findings also indicate that individuals who are practising and upskilling themselves in collaborative leadership at a local level also need to be supported by wider institutional and system measures to maximise their impact. Personal mindsets, institutional structures and principles for collaborative practice (such as those shown in Figure 3) all have a role to play in improving the effectiveness of local-level collaboration for resilience. This calls for partnerships that integrate these characteristics to leverage action and accelerate the scale and results of resilient development.

Current resilience policies are built on an assumption that local stakeholders across the Pacific Islands region have the inherent ability to create cross-sector and multi-stakeholder partnerships. This research confirmed that such an ability is already evident to some extent amongst Pacific Island practitioners and networks, but more could be done to make the invisible visible through documenting and building upon the region’s rich collaborative problem-solving experiences. Attempts to enhance collaborative ‘soft skills’ would be most beneficial if they consider first, and build on, the existing collaborative capital of Pacific Islanders. And a strongly articulated collaborative framework would provide the opportunity to connect human resources across public, private and civil society realms in innovative ways. This would work towards advancing the call to action for a “model collaborative, inclusive and effective action on sustainable urbanisation” as a key priority for discussion at the 2022 Commonwealth Heads of Government meeting in Kigali, Rwanda (Commonwealth Local Government Forum 2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the conceptual and review inputs of Professor John Hay. Thank you to those who participated in the research during a global pandemic; your willingness to share your insights and time is appreciated.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The first two authors are financially supported by the Griffith University scholarships fund via the Australian Government’s Post-graduate Awards programme. The fifth author is supported by the Discovery Early Career Research Award

References

Ansell, C. and Gash, A. (2007) Collaborative governance in theory and practice. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 18 (4), 543–571. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mum032

Archibald, M.M., Ambagtsheer, R.C., Casey, M.G. and Lawless, M. (2019) Using Zoom videoconferencing for qualitative data collection: perceptions and experiences of researchers and participants. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 18. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919874596

Australian Bureau of Meteorology and Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation. (2014) Climate variability, extremes and change in the Western Tropical Pacific: new science and updated country reports. ABoM & CSIRO, Melbourne, Australia. Available at: https://www.pacificclimatechangescience.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/PACCSAP_CountryReports2014_WEB_140710.pdf [Accessed 3 December 2021].

Australian Council for International Development & Research for Development Impact Network. (2017) Principles and guidelines for ethical research and evaluation in development. Canberra, Australia. Available at: https://rdinetwork.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Updated-Aug-2021_ACFID-RDI-Network-Ethical-Principles_Accessible.pdf [Accessed 5 December 2021].

Aylett, A. (2010) Participatory planning, justice, and climate change in Durban, South Africa. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 42 (1), 99–115. https://doi.org/10.1068/a4274

Bahadur, A.V., Ibrahim, M. and Tanner, T. (2013) Characterising resilience: unpacking the concept for tackling climate change and development. Climate and Development, 5 (1), 55–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2012.762334

Boyd, E. and Folke, C. (2011) Conclusions: adapting institutions and resilience. In: Boyd, E. and Folke, C. (eds.) Adapting institutions: governance, complexity and social-ecological resilience, (pp. 264–280). Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Brink, E. and Wamsler, C. (2018) Collaborative governance for climate change adaptation: mapping citizen–municipality interactions. Environmental Policy & Governance, 28 (2), 82–97. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.1795

Campbell, J.R. (2019) Urbanisation and natural disasters in Pacific Island countries. Tokyo, Japan. Available at: https://toda.org/assets/files/resources/policy-briefs/t-pb-46_campbell-john_urbanisation-and-natural-disasters-in-pics.pdf [Accessed 5 December 2021].

Catrien, J.A.M., Termeer, A.D. and Biesbroek, G.R. (2017) Transformational change: governance interventions for climate change adaptation from a continuous change perspective. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 60 (4), 558–576. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2016.1168288

Clarke, A. and Fuller, M. (2010) Collaborative strategic management: strategy formulation and implementation by multi-organizational cross-sector social partnerships. Journal of Business Ethics, 94, 85–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0781-5

Comes, M., Dubbert, M., Garschagen, M., Lee, Y., Grunewald, L., Lanzendorfer, M., Mucke, P., Neuschafer, O., Pott, S., Post, J., Schumann-Bolsche, D., Vandemeulebroecke, B., Welle, T. Birkman, J. (2016) World risk report 2016. Bonn, Germany: Bundnis Entwicklung Hilft and United Nations University. Available at: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/WorldRiskReport2016_small.pdf [Accessed 3 February 2022].

Commonwealth Local Government Forum. (2021) Home [Facebook] Available at: https://www.facebook.com/CLGFhq/?ref=page_internal. [Accessed 2 February 2022].

Connell, J. (2021) COVID-19 and tourism in Pacific SIDS: lessons from Fiji, Vanuatu and Samoa? The Round Table, 110 (1), 149–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/00358533.2021.1875721

Dietz, T., Ostrom, E. and Stern, P.C. (2003) The struggle to govern the commons. Science, 302 (5652), 1907–1912. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1091015

Dumaru, P. (2010) Community-based adaptation: enhancing community adaptive capacity in Druadrua Island, Fiji. WIREs Climate Change, 1 (5), 751–763. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.65

Eldridge, K., Larry, L., Baird, J. and Kavanamur, D. (2018) A collaborative governance approach to improving tertiary education in Papua New Guinea. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 38 (1), 78–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2018.1423949

Emerson, K., Nabatchi, T. and Balogh, S. (2012) An integrative framework for collaborative governance. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 22 (1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mur011

Fairbairn-Dunlop, P. (2005) Gender, culture and sustainable development – the Pacific way. In: Hooper, A. (ed.) Culture and sustainable development in the Pacific, (pp. 62–75). Canberra, Australia: Australian National University. Available at: http://press-files.anu.edu.au/downloads/press/p99101/pdf/ch0416.pdf [Accessed 3 February 2022].

Fankhauser, S. and Stern, N. (2016) Climate change, development, poverty and economics. London, United Kingdom. Available at: https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/728181464700790149-0050022016/original/NickSternPAPER.pdf [Accessed 3 February 2022].

Feiock, R.C. (2013) The institutional collective action framework. Policy Studies Journal, 41 (3), 397–425. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12023

Fereday, J. and Muir-Cochrane, E. (2006) Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5 (1), 80–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500107

Folke, C., Hahn, T., Olsson, P. and Norberg, J. (2005) Adaptive governance of social-ecological systems. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 30, 44–473. http://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.energy.30.050504.144511

Forsyth, M. (2009) A bird that flies with two wings: the Kastom and state justice systems in Vanuatu. Canberra, Australia: ANU E Press. http://doi.org/10.22459/BFTW.09.2009

Foukona, J.D. (2017) Solomon Islands’ urban land tenure: growing complexity, In Brief: 2017/05. Canberra, Australia: Australian National University. Available at: https://dpa.bellschool.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/publications/attachments/2017-03/ib_2017_05_foukona_final_1.pdf [Accessed 3 February 2022].

Foukona, J. and Allen, M. (2017) Urban land in Solomon Islands: powers of exclusion and counter-exclusion. In: McDonnell, S., Allen, M. and Filer, C. (eds.) Kastom, property and ideology: land transformations in Melanesia, (pp. 85–110). Canberra, Australia: Australian National University Press.

Goklany, I.M. (2007) Integrated strategies to reduce vulnerability and advance adaptation, mitigation, and sustainable development. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 12 (5), 755–786. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11027-007-9098-1

Government of Fiji. (2017) 5-year and 20-year National Development Plan: transforming Fiji. Suva, Fiji. Available at: https://www.fiji.gov.fj/getattachment/15b0ba03-825e-47f7-bf69-094ad33004dd/5-Year-20-Year-NATIONAL-DEVELOPMENT-PLAN.aspx [Accessed 3 February 2022].

Government of Papua New Guinea. (2019) National audit of the informal economy. Papua New Guinea: Government of Papua New Guinea.

Hassall, G., Kensen, M., Takeke, R., Taoba, K. and Tipu, F. (2019) Local government in the Pacific Islands. In: Kerley, R., Liddle, J. and Dunning, P.T. (eds.) The Routledge handbook of international local government, (pp. 110–130). London, England: Routledge.

Hassall, G. and Tipu, F. (2008) Local government in the South Pacific Islands. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, (1), 7–29. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.v1i0.766

Hay, J.E. (2021) On the frontline: climate impacts and responses in the Pacific Islands region. In Lectures in climate change, our warming planet: identifying and managing the impacts and risks. Rosenzweig, C., Parry, M. and De Mel, M. (eds.) Our warming planet climate change impacts and adaptation, (pp. 321–355). World Scientific Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1142/9789811238222_0015

Hay, J.E. and Mimura, N. (2013) Vulnerability, risk and adaptation assessment methods in the Pacific Islands region: past approaches, and considerations for the future. Sustainability Science, 8 (3), 391–405. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-013-0211-y

Hukula, F. (2017) Kinship and relatedness in urban Papua New Guinea. Journal de la Société des Océanistes, 159–170. https://doi.org/10.4000/jso.7756

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (IPCC). (2022) Climate change 2022: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Working Group II contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (eds.) Pörtner, H.O., Roberts, D.C., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E.S., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., Craig, M., Langsdorf, S., Löschke, S., Möller, V., Okem, A., Rama, B. Cambridge University Press, In Press. Available at: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/sixth-assessment-report-working-group-ii/ [Accessed 10 December 2021].

Johnston, K. (2017) A gender analysis of women in public-private-voluntary sector ‘partnerships’. Public Administration, 95 (1), 140–159. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12288

Jones, P. and Sanderson, D. (2017) Urban resilience: informal and squatter settlements in the Pacific region. Development Bulletin, 78, 11–15. Available at: https://bellschool.anu.edu.au/experts-publications/publications/5667/development-bulletin-urban-development-pacific [Accessed 3 February 2022].

Juhola, S. (2011) Food systems and adaptive governance: food crisis in Niger. In: Boyd, E. and Folke, C. (eds.) Adapting institutions: governance, complexity and social-ecological resilience, (pp. 148–170). Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Jupiter, S.D., Epstein, G., Ban, N.C., Mangubhai, S., Fox, M. and Cox, M. (2017) A social–ecological systems approach to assessing conservation and fisheries outcomes in Fijian locally managed marine areas. Society & Natural Resources, 30 (9), 1096–1111. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2017.1315654

Kalesnikaite, V. (2019) Keeping cities afloat: climate change adaptation and collaborative governance at the local level. Public Performance & Management Review, 42 (4), 864–888. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2018.1526091

Keen, M. and Barbara, J. (2015) Pacific urbanisation: changing times. In Brief 2015/64. Canberra, Australia. Available at: https://dpa.bellschool.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/publications/attachments/2016-07/ib2015.64_keen_and_barbara.pdf [Accessed 3 February 2022].

Keen, M. and Connell, J. (2019) Regionalism and resilience? Meeting urban challenges in Pacific Island states. Urban Policy and Research, 37 (3), 324–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/08111146.2019.1626710

Kelman, I., Gaillard, J.C. and Mercer, J. (2015) Climate change’s role in disaster risk reduction’s future: beyond vulnerability and resilience. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science, 6 (1), 21–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-015-0038-5

Kiddle, G.L., McEvoy, D., Mitchell, D., Jones, P. and Mecartney, S. (2017) Unpacking the Pacific Urban Agenda: resilience challenges and opportunities. Sustainability, 9 (10), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9101878

Lee, Y. and Bae, S. (2019) Collaboration and Confucian reflexivity in local energy governance: the case of Seoul’s one less nuclear power plant initiatives. Journal of Contemporary Eastern Asia, 18 (1), 153–174. https://doi.org/10.17477/jcea.2019.18.1.153

Lindsay, A. (2018) Social learning as an adaptive measure to prepare for climate change impacts on water provision in Peru. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, 8 (4), 477–487. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-017-0464-3

Madraiwiwi, R. J. (2006) Keynote address – governance in Fiji: the interplay between indigenous tradition, culture and politics. In: Firth, S. (ed.) Globalisation and governance in the Pacific Islands: state, society and governance in Melanesia, (pp. 289–296). ANU Press. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt2jbj6w.19 [Accessed 3 February 2022].

Mailelegaoi, T.S. (2017) Hon. Prime Minister of Samoa, opening address by Prime Minister Tuilaepa Sailele Mailelegaoi of Samoa to open the 48th Pacific Islands Forum 2017. Paper presented at the Pacific Islands Forum, Apia, Samoa. https://www.forumsec.org/2017/09/05/opening-address-prime-minister-tuilaepa-sailele-mailelegaoi-samoa-open-48th-pacific-islands-forum-2017/ [Accessed 30 December 2021].

Manley, M., Hay, J., Lal, P., Bennett, C., Chong, J., Campbell, J.R. and Thorp, W. (2016) Research and analysis on climate change and disaster risk reduction. Working Paper 1. Needs, priorities and opportunities related to climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction. Wellington, New Zealand. Available at: https://www.mfat.govt.nz/assets/Aid-Prog-docs/Research/Climate-Change-and-Disaster-Risk-Reduction-Working-Paper-1-Needs-priorities-and-opportunities.pdf [Accessed 12 December 2021].

Mansuri, G. and Rao, V. (2013) Localizing development: does participation work? United States: World Bank Publications. Available at: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/11859/9780821382561.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [Accessed 3 February 2022].

Marschan-Piekkari, R., Welch, C., Penttinen, H. and Tahvanainen, M. (2004) Interviewing in the multi-national corporation: challenges of the organisational context. In: Marschan-Piekkari, R. and Welch, C. (eds.) Handbook of qualitative research methods for international business, (pp. 244–263). Cheltanham, United Kingdom: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

McEvoy, D., Mitchell, D. and Trundle, A. (2020) Land tenure and urban climate resilience in the South Pacific. Climate and Development, 12 (1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2019.1594666

McNamara, K., Clissold, R. and Westoby, R. (2020) Marketplaces as sites for the development‐adaptation‐disaster trifecta: insights from Vanuatu. Asia Pacific Viewpoint. https://doi.org/10.1111/apv.12293

Meadowcroft, J. (2011) Sustainable development. In: Bevir, M. (ed.) The Sage handbook of governance. London, UK: Sage Publications Ltd. https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781446200964.n34

Miles, M.B. and Huberman, A.M. (1994) Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, United States: Sage Publications.

Mitchell, T. and Maxwell, S. (2010) Defining climate compatible development. Policy Brief. London, United Kingdom: Climate and Development Knowledge Network. Available at: https://cdkn.org/sites/default/files/files/CDKN-CCD-Planning_english.pdf [Accessed 4 February 2022].

Morse, R.S. and Stephens, J.B. (2012) Teaching collaborative governance: phases, competencies, and case-based learning. Journal of Public Affairs Education, 18 (3), 565–583. https://doi.org/10.1080/15236803.2012.12001700

Nailatikau, M. and Goulding, N. (2021) Localising Pacific consulting. Dev Policy blog, 8 November. Available at: https://devpolicy.org/localising-pacific-consulting-20211108/?print=print [Accessed 2 February 2022].

Nalau, J., Handmer, J., Dalesa, M., Foster, H., Edwards, J., Kauhiona, H., Yates, L. and Welegtabit, S. (2016) The practice of integrating adaptation and disaster risk reduction in the south-west Pacific. Climate and Development, 8 (4), 365–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2015.1064809

Nunn, P.D. and McNamara, K.E. (2019) Failing adaptation in island contexts: the growing need for transformational change. In: Klock, C. and Fink, M. (eds.) Dealing with climate change on small islands: towards effective and sustainable adaptation, (pp. 19–44). Gottingen, Germany. Gottingen University press. https://doi.org/10.17875/gup2019-1210

Olsson, P., Gunderson, L.H., Carpenter, S.R., Ryan, P., Lebel, L., Folke, C. and Holling, C.S. (2006) Shooting the rapids: navigating transitions to adaptive governance of social-ecological systems. Ecology and Society, 11 (1), 18. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-01595-110118

Pacific Community. (2022) The Pacific Islands region. Suva, Fiji: Geoscience, Energy and Maritime Division.

Pacific Community, Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme, Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat, United Nations Development Programme, United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, and University of the South Pacific. (2016) Framework for resilient development in the Pacific: an integrated approach to address climate change and disaster risk management 2017–2030. Suva, Fiji. Available at: https://www.forumsec.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/FRDP_2016_Resilient_Dev_pacific.pdf [Accessed 4 February 2022].

Parsons, M., Brown, C., Nalau, J. and Fisher, K. (2018) Assessing adaptive capacity and adaptation: insights from Samoan tourism operators. Climate and Development, 10 (7), 644–663. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2017.1410082

Phillips, T. and Keen, M. (2016) Sharing the city: urban growth and governance in Suva, Fiji. SSGM Discussion Paper. Canberra, Australia: Australian National University. Available at: https://bellschool.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/publications/attachments/2016-09/dp_2016_6_phillips_and_keen.pdf [Accessed 4 February 2022].

Purdy, J.M. and Jones, R.M. (2012) A framework for assessing power in collaborative governance processes [with commentary]. Public Administration Review, 72 (3), 409–418. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2011.02525.x

Rhodes, D. (2014) Capacity across cultures: global lessons from Pacific experiences. Melbourne, Australia: Inkshed Press Pty Ltd.

Ruane, S. (2020) Applying the principles of adaptive governance to bushfire management: a case study from the South West of Australia. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2019.1648243

Scheyvens, R. and Movono, A. (2020) Development in a world of disorder: tourism, COVID 19 and the adaptivity of South Pacific people. Palmerston North, NZ: Massey University. Institute of Development Studies. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10179/15742 [Accessed 4 February].

Schipper, L. and Pelling, M. (2006) Disaster risk, climate change and international development: scope for, and challenges to, integration. Disasters, 30 (1), 19–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9523.2006.00304.x

Schneider, P., Lawrence, J., Glavovic, B., Ryan, E. and Blackett, P. (2020) A rising tide of adaptation action: comparing two coastal regions of Aotearoa-New Zealand. Climate Risk Management, 30, 100244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2020.100244

Scott, T.A. and Thomas, C.W. (2017) Unpacking the collaborative toolbox: why and when do public managers choose collaborative governance strategies? Policy Studies Journal, 45 (1), 191–214. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12162

Sharpe, D.R. (2004) The relevance of ethnography to international business research. In: Piekkari, R. and Welch, C. (eds.) Handbook of qualitative research methods for international business. Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, United Kingdom: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

Singh, P., Tabe, T. and Martin, T. (2022) The role of women in community resilience to climate change: a case study of an Indigenous Fijian community. Women’s Studies International Forum, 90, 102550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2021.102550

Singh, P.K. and Chudasama, H. (2021) Pathways for climate resilient development: human well-being within a safe and just space in the 21st century. Global Environmental Change, 68, 102277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.glonvcha.2021.102277

Spark, C., Corbett, J. and Fairbairn-Dunlop, P. (2021) Tomorrow’s woman? The Journal of Pacific History, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223344.2021.1988846

Stout, M. and Love, J.M. (2017) Integrative governance. The American Review of Public Administration, 47 (1), 130–147. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074015576953

Taylor, M. (2019) Secretary General, Opening speech, Pacific Urban Forum, 1 July 2019, Nadi, Fiji.

Trundle, A. (2020) Resilient cities in a sea of islands: informality and climate change in the South Pacific. Cities, 97, 102496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2019.102496

Trundle, A., Barth, B. and Mcevoy, D. (2019) Leveraging endogenous climate resilience: urban adaptation in Pacific Small Island Developing States. Environment and Urbanization, 31 (1), 53–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247818816654

Tuimaleali’ifano, A.M. (2006) Matai titles and modern corruption in Samoa costs, expectations and consequences for families and society. In: Firth, S. (ed.) Globalisation and governance in the Pacific Islands, (pp. 363–372). ANU Press. Available at: http://press-files.anu.edu.au/downloads/press/p55871/pdf/ch191.pdf [Accessed 6th February 2022].

United Nations Development Programme. (2016) An integrated framework to support local governance and local development. New York, United States: UNDP. Available at: https://www.undp.org/publications/integrated-framework-support-local-governance-and-local-development [Accessed 10 December 2021].

United Nations Human Settlement Programme (UN-Habitat), United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNEASCAP) and Commonwealth Local Government Forum Pacific. (2019) Fifth Pacific Urban Forum Declaration. Pacific Urban Forum, Nadi, Fiji. Available at: http://www.clgf.org.uk/default/assets/File/Fifth%20Pacific%20Urban%20Forum%20Declaration.pdf [Accessed 12 August 2021].

Wairiu, M. (2006) Governance and livelihood realities in Solomon Islands. In: Firth, S. (ed.) Globalisation and governance in the Pacific Islands: state, society and governance in Melanesia, (pp. 409–416). ANU Press. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt2jbj6w.27 [Accessed 12 January 2022].

Warrick, O., Aalbersberg, W., Dumaru, P., McNaught, R. and Teperman, K.J.R. (2017) The ‘Pacific adaptive capacity analysis framework’: guiding the assessment of adaptive capacity in Pacific Island communities. Regional Environmental Change, 17 (4), 1039–1051. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-016-1036-x

Yin, R.K. (2003) Case study research: design and methods. Thousand Oaks, United States: Sage Publications Pty. Ltd.

1 Examples include the New Urban Agenda, Sustainable Development Goals, Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction, and Paris Agreement.

2 Research was undertaken in accordance with Griffith University’s research ethics protocols and guided by the ‘Principles and Guidelines for Ethical Research and Evaluation in Development’ (Australian Council for International Development and Research for Development Impact Network, 2017).

3 The term ‘prehistory’ is used here as in Ansell and Gash’s (2007) collaborative governance framework to refer to the pre-existing relationships and history between collaborating stakeholders.

4 ‘Types and participation’ was previously published within a blog by the first author: https://blogs.griffith.edu.au/asiainsights/is-there-an-art-to-multi-stakeholder-collaboration-for-resilient-development-in-the-pacific-region/