Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance

Issue 26

May 2022

RESEARCH AND EVALUATION (PEER REVIEWED)

Betwixt Agency and Accountability: Re-Visioning Street-Level Bureaucrats

Priyanshu Gupta

Business Sustainability Area, Indian Institute of Management Lucknow, Lucknow, India, priyanshu.gupta@iiml.ac.in

Manish Thakur

Public Policy and Management Group, Indian Institute of Management Calcutta, Kolkata, India, mt@iimcal.ac.in

Bhaskar Chakrabarti

Public Policy and Management Group, Indian Institute of Management Calcutta, Kolkata, India, bhaskar@iimcal.ac.in

Corresponding author: Bhaskar Chakrabarti, Public Policy and Management Group, Indian Institute of Management Calcutta, Kolkata, India, bhaskar@iimcal.ac.in

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi26.8173

Article History: Received 08/11/2020; Accepted 06/04/2022; Published 31/05/2022

Citation: Gupta, P., Thakur, M., Chakrabarti, B. 2022. Betwixt Agency and Accountability: Re-Visioning Street-Level Bureaucrats. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, 26, 94–113. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi26.8173

© 2022 by the author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

(CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties

to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the

material for any purpose, even commercial, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Abstract

This paper presents a critical assessment of the much-discussed tension between bureaucratic accountability and the contextual discretion of ‘street-level bureaucrats’ (i.e. front-line public sector workers). Based on an extensive literature review, the paper outlines the implications of the exercise of agency by street-level bureaucrats in everyday settings. It also looks at the challenges this agency engenders: loss of accountability and divergence from stated policy goals. The paper underlines the need for future research on institutional structures and organisational cultures around street-level bureaucracy. It suggests possible lines of enquiry to steer the debate in new, and hopefully productive, directions.

Introduction

As COVID-19 swept across India during the summers of 2020 and 2021, the role and importance of India’s lowest levels of bureaucracy, front-line workers who are often called ‘street-level bureaucrats’, came into sharp focus. When the rest of the country remained under extended lockdowns, these workers were tested as never before. Extremely stretched healthcare workers – doctors, nurses and paramedical staff – worked overtime to detect, trace and isolate infected patients, and subsequently coordinate a massive vaccination drive across the country. Thousands of police officials stepped out to enforce the stringent lockdown while simultaneously facilitating delivery of essential supplies and ensuring the movement of millions of migrant workers so that they safely reached their homes. Millions of teachers scrambled not only to adapt to online teaching but also to ensure the supply of vital educational materials to their now out-of-school and often uninterested students. Postal officials worked overtime to help the smooth running of the economy, and countless sanitation officials took up the now risky occupation of sifting through and managing increasingly bio-hazardous waste, often with limited safety equipment.

While there remain conflicting opinions on how well India managed the crisis, much of the analysis has focused on critiquing large-scale pandemic management and mitigation policies and economic recovery packages (Bharali et al. 2020; Nilsen 2021; The India Forum 2021). Yet the lasting images and stories in the public consciousness tend to be those of the millions of front-line, street-level bureaucrats who were called upon to implement those constantly changing policies in the most challenging circumstances. Policy implementation was hardly a simple matter in a high-stakes environment, as the everyday decisions of these street-level bureaucrats now had consequences of life or death for their clients. For example, front-line healthcare staff were called upon to allocate scarce healthcare resources like ventilators and oxygen cylinders among numerous clients with urgent needs. Local government officials – municipal and panchayat (rural local government) staff – had to decide whether to create isolation zones and conduct contact-tracing drives, or allow flexibility in order to ensure availability of essential goods and services.

Unsurprisingly, there were wide variations in performance across these workers. On the one hand, many nurses across India not only put in extra hours with no overtime payments, but also often stepped up to fill the gap left by a lack of qualified doctors (Mukhopadhyay 2021). On the other, there were regrettable incidences of avoidable deaths when scarce resources were reserved for influential persons (Aaj Tak 2021), or hospital staff abandoned patients in intensive care units at times of power outages. Similarly, the country saw some police officials coordinating relief distribution and safe passage for swarms of migrants, but others meting out inhumane and degrading treatment to people seeking essential supplies, in an effort to enforce the strict lockdown (Gupta and Hollingsworth 2020).

In other words, India’s pandemic response found many street-level bureaucrats going beyond the call of duty, but also some guilty of serious neglect, dereliction of duty and at times gross abuse of power. Ostensibly, these contrasting narratives occurred within the same policy apparatus and socio-cultural milieu.

This begs several questions:

• Is the divergence in outcomes a result of too much discretion or a valid exercise of agency by the street-level bureaucrat?

• Does their agency render street-level bureaucrats unaccountable in terms of implementing an envisaged policy?

• How does such agency get exercised and negotiated in the everyday work-life of street-level bureaucrats?

These questions assumed critical importance in the pandemic context, but the issues are by no means new.

The agency–accountability conundrum in democratic governance is a central feature of debates on bureaucracy across widely varying contexts (Tuohy 2003; Brandsma and Adriaensen 2017). In the case of India, a growing – albeit as yet thin – literature has been highlighting that street-level bureaucrats are not merely policy implementers, but instead “act as policymakers in the way they interpret policy text and represent it to the local people” (Pampackal 2019, p. 171). In effect, they orchestrate “the complex interplay between sarkari kaghaz, daftar and the asli (paper, office and the real)” by simultaneously developing a thick documentary trail of bureaucratic practice (evaluation, assessment, monitoring, audit etc), and interpreting often obscure official policies, thereby making them real (Mathur 2016, pp. 167, 172). There are even instances of intentional ‘silencing’ [disregarding] of selected bureaucratic norms and practices by bureaucrats and local politicians when “they consider [the practices]… as seemingly irrelevant and unusable for current organizational settings” (Bagchi and Chakrabarti 2021, p. 299).

Street-level bureaucrats’ influence has grown in the wake of rapidly expanding public services and the ever-increasing regulation of daily life through local levels of government over the last three decades (Aiyar and Walton 2015). Further, the expansion of local governments’ roles and functions has happened despite limited capacities (Pritchett et al. 2013). It has enabled street-level bureaucrats, alongside senior local government officials and political elites, to exercise greater discretion in mediating the delivery of various public services (Berenschot 2010). At the same time, citizens’ ability to hold local officials accountable for performance varies vastly with their socio-economic characteristics, such as gender and education levels (Brulé 2015). In line with other developing countries, and even though the Indian government makes rhetorical commitments to the contrary, citizens are not treated equally, bringing to the fore questions of the agency and accountability of local government officials (Lipsky 2021). The significant discretion being exercised by those officials, as well as wide divergence in policy outcomes across different regional contexts, calls for a serious investigation of the agency–accountability conundrum. Yet, to date, there has been limited theoretical or empirical work on street-level bureaucrats in India.

This paper attempts to systematically review the extant literature on street-level bureaucracy. Its central focus is on analysing the agency–accountability conundrum across various dimensions of street-level bureaucrats’ everyday work and performance. Consequently, the paper presents a qualitative systematic review (Grant and Booth 2009) of the literature on street-level bureaucracy around three pre-identified themes: ‘street-level discretion’, ‘principal-agent theory’, and ‘accountability’. The analysis explores the following central question: How do local government officials navigate their discretion and agency as part of their everyday work, and what are the implications for their accountability to policy-makers and the state?

The literature reviewed comprised articles published in leading journals of local governance and public administration, supplemented by an exhaustive keyword search for ‘street-level bureaucracy’. Theoretical literature on street-level bureaucracy in local governance in India remains thin. Hence, the paper’s key insights are drawn from scholarship on street-level bureaucracy in other contexts. However, it integrates a certain amount of research evidence and anecdotes from India to support key arguments. The paper’s insights are likely to be applicable not only to local governance in India, but also to other developing countries where local government officials are called upon to perform an ever-increasing role in mediating service delivery in a context of limited state capacity and resources, leading to wide variations in client experiences and service outcomes.

The paper is organised as follows:

1. Overview of the literature on street-level bureaucracy to contextualise the current study’s focus.

2. Discussion of specific local development contexts that make street-level discretion inevitable, and how such discretion manifests in everyday bureaucratic processes.

3. Exploration of how agency at the street level can help drive positive outcomes and ensure better policy compliance at the local level.

4. Discussion of contextual factors that influence such discretion, including sources of potential bias during policy implementation.

5. Summary of arguments and discussion of the essential contradictions and challenges in managing street-level discretion, including how street-level bureaucrats cope with these contradictions.

6. Development of a nuanced theory of managing street-level divergence by considering different organisational contexts that could influence the use and regulation of discretion.

7. Conclusion, which summarises the discussion and outlines a future agenda for productive research and ethnographic exploration of the manifold practices of street-level bureaucracy.

Understanding street-level bureaucracy

A desire to give due recognition to the work and lives of the millions of public service employees working away at the lower echelons of the machinery of government, making the state come alive to its citizens, motivated Michael Lipsky (1969, 2010) to coin the term ‘street-level bureaucracy’, and to develop an understanding of how front-line public service employees across a wide range of professions interact directly with the citizenry. Their jobs entail applying judgement and exercising significant discretion while providing government services, enforcing the law and distributing public benefits (Lipsky 1969, 2010). Lipsky’s work focused mainly on highlighting the important role of street-level bureaucrats and the difficult conditions of their work. He argued that they received almost no recognition or appreciation for their performance, which often led to their disillusionment. However, inadvertently, the discretionary aspect of their work attacked the very foundations of a bureaucracy that was trusted as a repository of expertise and specialised knowledge, and governed by ideals of “efficient, rational, and impartial decision-making” (Farazmand 2010, pp. 245–247). Lipsky’s (1969) work also came at a time when bureaucracy was being heavily criticised as “inefficient, corrupt, repressive”. It also, perhaps unintentionally, provided a theoretical explanation for prejudice and policy divergence; and as a result contributed to the advent of reforms that ushered in New Public Management (NPM)1 and collaborative network governance structures, leading to a reduction in traditional government functions characterised as a “hollowing of the State” (Flinders 2006, p. 245). Therefore, it is not surprising that Lipsky’s early work did not get due attention, and for the next three decades he remained almost a lone crusader for the cause of understanding street-level bureaucracy.

However, since the economic crisis of 2008, which highlighted regulatory failures and caused widespread distress in societies across the world, bureaucracies and welfare delivery functions are again becoming increasingly valued (Piore 2011). Moreover, the contentious results of NPM reforms, that seemed to prize efficiency above all else (Dan and Pollitt 2015; Hood and Dixon 2015), have led to an increased appreciation of traditional public sector values and calls to “bring public organizations and organizing back into the analysis” (Arellano-Gault et al. 2013, p. 157). There is also an increased realisation that even in the new forms of networked governance structures, the problems of balancing discretion and accountability are not eliminated; they merely take a different organisational form (Piore 2011). Efforts to eliminate discretion through regulation (Rice 2013) or the use of e-governance (Buffat 2015) have also been only partially successful.

There is also increasing evidence of street-level discretion’s positive impacts on enhancing client service outcomes and promoting more effective policy implementation (Rice 2013; Gofen 2014; Tummers and Bekkers 2014). There are opportunities to utilise such agency at the front line to bring about superior local development outcomes and overcome the challenges that made traditional public bureaucracy appear ineffective in catering to community needs: it can help foster adaptability, flexibility and responsiveness (Felts and Jos 2000). This understanding has led to a revival of scholarship on street-level bureaucracy, with a thriving literature that attempts to build a theory suited to the modern public management context (Hupe 2019).

The inevitability of street-level policy divergence

Policy divergence in the outcomes of the work of street-level bureaucrats is the inevitable consequence of roles and functions characterised by ambiguity in policy definition, difficulty in managing performance, and multiple resource constraints that lead to bounded rationality.

The complexity of local governance organisations often leads to ambiguity in policy. Local governments are required to manage two different production functions at the same time – efficiency and effectiveness. While efficiency is characterised by maximisation of outputs or minimising inputs, effectiveness is linked to the delivery of policy outcomes and societal impacts, which are often more ambiguous and complex to define (Arellano-Gault et al. 2013; Hansen and Ferlie 2016). Thus, discretion may result from the incompleteness of rules, indeterminacy of language, or failure to account for all possible contingencies (Piore 2011). Often, street bureaucrats are called upon to weigh a complex set of competing factors and moral principles in a context of multiple alternative possibilities (Gofen 2014). Further, these weights and considerations vary substantially with the local environment and context. As a result, street-level bureaucrats are required to adapt the policy to the local context to make it meaningful for their clients (Piore 2011; Tummers and Bekkers 2014). Moreover, bureaucrats are required to be responsive to their clients’ individual circumstances while still attaining the original policy objectives. And for many, such as classroom teachers, social workers or police officers, it is simply impossible to cover all the dimensions of their role in clear policy language, leaving considerable scope for professional judgement (Lipsky 2010).

Discretion also arises from the difficulty in managing street-level work. Owing to the multiple dimensions of objectives and public service values (Arellano-Gault et al. 2013), street-level bureaucrats are often expected to perform ambiguous roles, navigating contradictions, making it impossible for them to realise intended policy goals. As a result, exercising traditional managerial control over their work becomes particularly difficult (Evans 2011). Moreover, attempts to curb discretion through a clearer definition of policy may lead to a proliferation of rules to the point where they cannot all be enforced, leaving the bureaucrat to pick and choose what matters most (Evans 2011; Piore 2011). The intrinsically human nature of some street-level interactions, for example those of a social worker or police officer, also involves interpersonal dimensions of work that are often indeterminate and impossible to monitor (Buffat 2015).

Some recent studies argue that the exercise of discretion is directly proportional to longer tenure and greater experience in a particular role, especially amongst male street-level bureaucrats (Assadi and Lundin 2018). As older local government officials acquire experience in meeting their clients’ needs, their increasing confidence and skills make them less amenable to formal steering by policy tools. However, growing experience can also lead to dereliction, which Hoag (2014, p. 414) defines as the “liminal space” between the policy and the practice of that policy.

Further, street-level bureaucrats may need to make decisions under tremendous resource constraints – limited information, resources, processing capacities and time (Gofen 2014; Tummers and Bekkers 2014). These constraints lead to bounded rationality (Gofen 2014), whereby different bureaucrats’ decisions and the outcomes of those decisions under similar circumstances become uncertain. For instance, a budgetary shortfall that makes it impossible for the bureaucrat to conform fully to the policy will force her/him to prioritise functions or objectives for which resources are available, and/or to allocate scarce resources according to her/his judgement (Piore 2011).

The above discussion highlights how it is impossible to eliminate discretion from the role of street-level bureaucrats. They are routinely called upon to exercise their professional judgement, a process which Evans (2011, p. 370) describes as acting as the “lubricant in the public policy machine”. Control over the dispensation of resources and information gives them considerable power and flexibility to make decisions (Farazmand 2010). They make choices among multiple alternative courses of action or inaction (Tummers and Bekkers 2014), attempting to balance the demands of policy implementation with community or individual needs (Gofen 2014). They often interpret the eligibility criteria for services and hence determine various kinds of rewards and sanctions for their clients. For instance, Evans (2011) highlights how practitioners interpret, often differently, ‘need’ and ‘risk’ for elderly people to determine their eligibility for care. Similarly, he shows differences in care professionals’ application of the criteria for beneficiaries, with some interpreting them narrowly to include only severe mental problems, while others take a broader view of mental health issues (Evans, 2011). Similarly, teachers determine which students should be put on the ‘college track’ or allocated additional educational support. Police officers regularly decide when to penalise and when to look the other way, depending on the severity and intent of the crime (Lipsky 2010).

Street-level bureaucrats may also ration, restrict or target services by withholding or providing additional information about loopholes, eligibility requirements or poorly publicised benefits (Evans, 2011). Or they can increase the costs of a service for clients they regard as undeserving by increasing wait times, withholding information or imposing psychological burdens, thereby discouraging and restricting access (Hoag 2011). Thus they can “make choices concerning the sort, quantity, and quality of sanctions and rewards on offer” during policy implementation (Tummers and Bekkers 2014, p. 529).

It is possible to use such discretion to influence long-term changes in client behaviour, as highlighted by Piore (2011), who showed how labour inspectors in Europe exercise four kinds of discretion. Firstly, as part of ‘sanctioning and deterrence’, officers can pick particular violations and seek to correct them in ways that deter future malpractice. Secondly, using ‘pedagogical discretion’, officers can actively help the client revise strategies and practices to reduce the burden of compliance. Thirdly, using ‘conciliatory discretion’, officers can mediate between different individuals and groups affected by the policy. Fourthly, using ‘entrepreneurial discretion’, they can devise and promote better approaches to compliance while navigating economic and technical constraints (Piore 2011).

Street-level bureaucrats may even actively resist or subvert prescribed policies by playing with the rules to deliberately slow down certain initiatives and programmes, or by selectively exploiting policy loopholes and creating obstacles so that they can broker knowledge and access (Evans 2011; Farazmand 2010; Hoag 2011). This policy divergence, wherein actions of public servants are contrary to the wishes and intentions of their superiors and policy-makers, can be seen as a kind of “guerrilla government” (Gofen 2014, pp. 474–475). The degree of divergence is often dependent on individual use of discretionary power based on (a) knowledge of loopholes in the rules, (b) flexibility in interpreting the policy differently in the particular institutional context, (c) relationships with supervisors, and (d) the personality of the bureaucrat concerned (Tummers and Bekkers 2014).

The literature thus highlights all of the following: the inevitability of street-level discretion; the range of mechanisms and tactics that may be used for exercising discretion; and the scope for significant policy divergence that leads to destabilisation of intended outcomes. Hoag (2011, p. 86) notes that “bureaucratic practices appear not as the product of logics (a contextualized rational choice), orders of discourse, or super-ordinate powers, but as a tangle of desires, habits, hunches, and conditions of possibility”. Analysing these varied and seemingly unpredictable outcomes involves complex considerations of the motivation, ethics, responsibility and integrity of street-level bureaucrats (Gofen 2014). The authors stress, however, that in undertaking such analysis it is important to identify the positive as well as negative dimensions of divergence, for it is in these divergent public official–citizen interactions that the welfare state is produced and reproduced as a dynamic societal institution (Rice 2013).

Celebrating agency: the desirability of street-level discretion

The previous section showed how street-level workers have the autonomous capacity to deviate partially from institutionalised patterns in ways that can make the welfare state truly come alive through varied interactions with citizen-clients (Rice 2013). The prospects of such decentralised action have formed the basis for bottom-up policy-making and encouraging ‘management by enabling’, similar to modern corporate organisational theory. Numerous studies indicate how street-level discretion can influence positive outcomes for citizens. Tummers and Bekkers (2014) highlight how it can enable better adaptation to context. They also establish that it even increases street-level bureaucrats’ willingness to implement policy (Tummers and Bekkers 2014). Rice (2013) argues that if street-level bureaucrats are given partial responsibility for policy outcomes, they are more likely to support rather than sidestep national policy goals. She further asserts that this realisation has enabled front-line agents to engage in newer tasks such as participating in the formulation of the organisation’s goals, building policy networks with other organisations and client stakeholders, and developing new instruments for client treatment, among others (Rice 2013).

Evans (2011), based on empirical findings from social care management, highlights how professional discretion is making modern organisations work, while Gofen (2014) shows how street-level divergence could drive substantial changes to policy based on factors like collectivism, transparency and the ‘other-serving’2 motivation of bureaucrats in exercising discretion. She looks at the motivational factors behind ‘discretionary choice’, which she characterises in a number of ways, including ‘responsible subversion’, ‘positive deviance’, ‘creative insubordination’, and ‘dissent shirking’3.

Firstly, as an exercise of rational choice, street-level discretion may serve as a mechanism to overcome barriers to policy implementation by bending rules to get the job done. For instance, in Gofen’s (2014) study, family health nurses bent the rules to waive immunisation payments to overcome antagonism from parents, motivated by the objective of ensuring immunisation. Secondly, as an ethical choice, it can enable bureaucrats to weigh moral principles and values in order to provide justice to citizen-clients. For instance, local government social workers could be seen bending the rules to grant single mothers privileges they were not strictly entitled to. Thirdly, as a professional choice, it gives bureaucrats the legitimacy to utilise their professional expertise and abilities to address problems efficiently, fairly and equitably. In the modern automated and ICT-based public management environment, street-level bureaucrats can complement and often correct information systems by applying their human judgement and intimate knowledge of the local context, thereby supplying a vital feedback loop for policy designers (Buffat 2015).

Recognising the agency inherent in street-level bureaucracy, some recent studies have discussed how it could be used to overcome problems inherent in traditional bureaucratic structures, contributing to innovation, flexibility and adaptability (Piore 2011). Especially in modern local government contexts that rely on activation policies to help clients become self-sufficient, street-level bureaucrats can exercise discretion to play a major role in customising services to the needs and capacity of individual clients (Rice 2013): employment and skills development programmes, for example. They can even become ‘policy entrepreneurs’ by combining innovation and activism to address complex dilemmas in service delivery, for instance in urban renewal and redevelopment projects (Lavee and Cohen 2019).

Thus, instead of being seen as a problem, street-level discretion often appears desirable in order to give committed public servants opportunities to fulfil their public service goals. However, this proposition assumes that street-level bureaucrats embrace the public service values of ethical decision-making, compassion, the quest for justice, and seeking to make a difference to the world. But the degree to which this is actually the case is often dependent on the social and structural variables that determine and influence the use of discretion.

Determinants of street-level discretion: a cautionary note

A certain degree of discretion seems both inevitable (owing to the ambiguity and complexity of street-level work) and desirable (in providing agency to bureaucrats to better serve their policy goals). However, it would be naive to assume that all discretion is exercised with an ‘other-serving’ motivation and conforms to a model of responsible behaviour. Discretion may instead lead to undesirable effects in accentuating certain biases and facilitating the ‘self-serving’ goals of bureaucrats. Ultimately, street-level discretion is limited, to a greater or lesser degree, by a formal policy framework. However, given resource constraints street-level bureaucrats can often choose to prioritise among a specified set of policy goals while remaining within the ambit of the formal policy (Gofen 2014; Tummers and Bekkers 2014). One of the most important constraints would appear to be ‘time’, which the bureaucrat manages based on his or her personal judgement and priorities (Piore 2011).

The factors that impinge on street-level discretion are thus a crucial area of investigation. Lipsky’s model theorises that street-level bureaucrats’ behaviour is shaped by organisational context, the intrinsic capabilities, desires and biases of individual workers (Lipsky 2010). To this, we may add the broader social context within which client interactions are embedded; the characteristics of the clients being helped (Rice 2013); and the balance of power in the two-way interaction between bureaucrat and client. The balance of power, itself, is shaped by the social context and characteristics of clients – for instance, class and caste hierarchies can determine the balance of power in a client–bureaucrat interaction.

Organisational context: Individual discretion is greatly circumscribed within the broader organisational context that sets the goals, rules and limits of time and resources (Rice 2013). Besides these hard constraints, there are also softer elements of organisational culture that create tacit rules and norms which bind the individual worker. Culture is especially important because the individual’s identity often gets entwined in his/her organisational role (Piore 2011). To this, one may add the education and training provided by the organisation (Rice 2013).

Social context: Economic, political, cultural and social systems also have a strong impact on shaping the bureaucrat’s norms, values and attitudes. In many ways, they frame the social and cultural morality that competes with the formal legality prescribed by policy (Hunter et al. 2016). Accountability mechanisms for policy implementation often have to encounter other forms of behaviour regulation such as law, culture and social norms, which have their own internal logic (Murphy and Skillen 2015). Social structures like family patterns and characteristics, class divisions in the economy, cultural practices that create broader societal discourses and perform an agenda-setting role, as well as political influences, are known to shape how a street-level bureaucrat performs his/her role (Rice 2013; Laitinen et al. 2018). This societal context is often responsible for influencing biases like prejudice, stereotypes and racism in the bureaucrat’s decisions, which result in differential treatment for clients (Raaphorst and Groeneveld 2019). In light of these factors, one finding from recent studies is the need to have ethnic minorities among the local government workforce to achieve more inclusive client outcomes (Hong 2021).

Personal attributes and motivations of the worker: Given the personalised nature of much street-level work, individual attributes play a major role in shaping how discretion gets exercised, as inevitably the official’s inner nature is a key factor (Kjaerulff 2020). Perceptions of ‘deserving’ and ‘undeserving’ citizens may depend on the personal situation of the worker and his/her particular experiences, especially with specific client social groups (Rice 2013; Hunter et al. 2016).

Street-level bureaucrats may also be motivated to pursue individual goals which are contrary to policy objectives (Matland 1995; Tummers and Bekkers 2014). Gofen (2014) describes this as driven by ‘self-serving’ motivation and could take the shape of ‘leisure shirking’ (avoidance of responsibilities by street-level bureaucrats to pursue leisure), or ‘sabotage’ (deliberate undermining of policy goals in consideration of personal objectives, ideology and values). Such individual motivations also have a significant bearing on the use of discretion for personal gain. There is an extensive literature that highlights pervasive corruption among street-level bureaucrats, especially across several developing countries, and their collusion with clients or other intermediaries (Kencana 2017; Smart 2018). In the Indian case, such corruption and collusion even gets legitimised as jugaad (‘flexible’ use of limited resources for efficient problem-solving) which gives ‘provisional agency’ to clients in need of public services (Jauregui 2014). However, corruption impacts social groups differently, as the poor and marginalised are more likely to be the victims owing to their greater dependence on public services, as well as having limited powers to bring such corruption to light or to seek redress (Jauregui 2014; Justesen and Bjørnskov 2014). In developing countries, the dynamics of street-level implementation and tolerance to bribery is embedded within systemic corruption, particularly corruption among superiors and colleagues (Gofen et al. 2022). Given this rampant problem, bureaucratic reforms have focused on eliminating discretion and thereby the room for corruption at the lower levels of bureaucracy. However, precise formulations of what counts as ‘legal’ have often failed to stem collusion or deliberate subversion of policy, as paradoxically these exercises in codification may offer greater possibilities for gaming the system (Smart 2018).

Client characteristics: Various studies have shown that the gender, ethnicity, colour or social status of clients can affect the individual decisions of the street-level bureaucrats (Hunter et al. 2016). As a result, clients from socially influential groups or social groups with high social status are likely to get better treatment (Rice 2013). Thus, clients’ appearance, statements and status may sometimes have more influence than the duty to adhere to norms or regulations (Hoag 2011). Clients are often stereotyped into various profiles such as ‘trouble maker’, ‘bad guy’ or ‘nice lady’, thereby influencing differential treatment (Maynard-Moody and Musheno 2003, p. 154; Rice 2013). Categorisation into such stereotypes is also inherently subjective, and will vary according to the individual worker’s moral standards (Rice 2013). Further, workers tend to be more responsive to cooperative or helpful clients, who are seen as better investments of time and resources (Rice 2013). The frequency of interaction, and hence level of shared understanding, between clients and workers also influences how discretion is exercised.

Given these multiple influences on the street-level bureaucrat, it is inevitable that discriminatory practices may creep into policy implementation, leading to the undermining of policy goals and objectives. Often, this forms the basis for commentary that rejects the bureaucracy’s claims of neutrality and fairness and paints bureaucrats as “nefarious, self-interested, rent-seeking obstructionists” (Hoag 2011, p. 82). Instead of being seen as an instrument of ‘social and class levelling’, bureaucrats are viewed as repressive agents of class rule and domination (Farazmand 2010). Moreover, street-level bureaucracy may become a substantial barrier to legitimate change demanded by a new political dispensation, due to its essential preference for the status quo (Farazmand 2010). The tensions between policy and practice, objectivity and subjectivity, formal and informal thus threaten to undermine the legitimacy of bureaucratic action (Hoag 2011). While street-level discretion can be celebrated for its emancipatory potential, it may also undermine necessary accountability and legitimacy. This contradiction has significant implications for management styles and leads to inherent difficulties in the way street-level bureaucrats can be held to account.

The agency–accountability conundrum and its impact on street-level bureaucrats

We have seen that there is “an irreducible core of discretion” in street-level work that is crucial to successful policy implementation (Evans 2011). However, the exercise of this street-level discretion is at the heart of the agency–accountability conundrum (Tuohy 2003; Brandsma and Adriaensen 2017): local officials are seen on the one hand as positive agents of effective service delivery and client satisfaction, but on the other as prejudiced, ineffective or corrupt actors that are the cause of governance failure.

Managing this conundrum may take two different directions: one is the ‘curtailment thesis’, which would imply a reduction of discretion available to local officials, and the other is the ‘enablement thesis’, which would attempt to provide local officials with greater resources and information to enable them to take more effective and equitable decisions (Buffat 2015). In the example of India, local governance officials are caught between these two contradictory trends: a plethora of rules, notices and circulars try to circumscribe their discretion even as the greater adoption of ICT tools enables them to exercise their judgement more effectively. This dichotomy has significantly affected the nature of their work and their professional identity.

Street-level bureaucrats are faced with the challenge of adhering to rules and routines to ensure fairness and equality of treatment for all citizens, whilst also being responsive to unique, individual circumstances that may require deviation from established policy. Often, such deviations may not have been sanctioned by their managers (Lipsky 2010). Amidst these contradictions, recognition of high-quality service is seldom forthcoming since performance is often difficult to measure (Lipsky 2010). Besides, working directly with the public leaves the bureaucrats vulnerable to criticisms, accusations and complaints of partisanship if they deviate too far from the script (Murphy and Skillen 2015). This makes them vulnerable to physical/psychological threats and hostility from clients (Lipsky 1969). At the same time, the proliferation of accountability and regulation mechanisms makes it more difficult for street-level bureaucrats to employ professional discretion (Murphy and Skillen 2015), and resource constraints like time and budget, amidst soaring public demand, make their job even harder to execute successfully (Lipsky 2010). All this undermines their ability to exercise public service values, which would likely have motivated these bureaucrats to join the service in the first place. As a result, Lipsky predicts that employees will, in the long term, become jaded, apathetic and disillusioned (Lipsky 2010).

To manage the agency–accountability conundrum and work pressure highlighted above, street-level bureaucrats use a variety of coping mechanisms (Tummers and Bekkers 2014; Hunter et al. 2016). The most common is to develop tacit knowledge and simplified, informal routines, practices and processes to guide everyday action and decision-making (Lipsky 1969; Gofen 2014; Piore 2011). This leads to a degree of standardisation of action responses that results in power of precedence (Rice 2013). Bureaucrats resort to ‘changing role expectations’ or ‘changing clientele definitions’ by segmenting their clients and choosing which situations to address or leave unaddressed (Lipsky 1969). Also, they often adapt their performance to meet formal accountability targets within resource constraints while leaving aside the unaccountable aspects of their work, a phenomenon termed ‘task suppression’ (Murphy and Skillen 2015). To ensure accountability, bureaucrats resort to risk avoidance and impression management while also developing practices for imposing unquestioned authority on their clients (Lipsky 1969; Murphy and Skillen 2015). Also, they seek to hide their divergent actions by making them opaque and inscrutable (Hoag 2011).

These coping mechanisms may have disastrous consequences for policy implementation. Bureaucrats’ routines, institutions and precedents present barriers to adaptability and change (Rice 2013). They can also create an ‘accountability trap’ in which targets may seemingly be met, but policy objectives are undermined (Murphy and Skillen 2015). Task suppression, risk avoidance or impression management can become part of the professional identity and organisational culture (Murphy and Skillen 2015), while routines and stereotypes can lead to systemic and self-reinforcing bureaucratic bias, marginalising certain client groups (Lipsky 1969).

In summary, the essential contradictions inherent in the work of street-level bureaucrats can lead to a disillusioned workforce and the use of coping mechanisms that generate criticism of traditional bureaucratic structures. In turn, this creates challenges in harnessing the intrinsic agency of street-level bureaucracy for enhanced policy outcomes. A tailored management policy, or rather management style, is needed to resolve this agency versus accountability trade-off and ensure the organisation’s goals are met.

Towards a theory of resolving agency–accountability contradictions

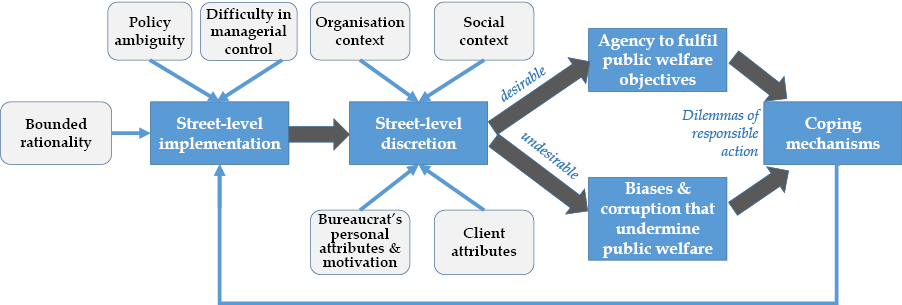

Having established the inevitability of street-level discretion and looked at both its positive and negative dimensions, the paper is now in a position to outline a broad understanding of the way street-level discretion works at the grassroots level (see Figure 1). To summarise the core argument of this paper thus far: the intrinsic ambiguity in policy definition that often arises from the complexity of policy goals, the bounded rationality of workers, and the difficulty of exercising managerial control, makes street-level discretion an essential element of policy implementation. This discretion is moderated by contextual factors and variables, such as organisational and social context, bureaucrats’ personal attributes and client characteristics. It can lead to desirable consequences in giving street-level bureaucrats the requisite agency to adapt policy to the specific context and achieve policy goals in spirit. But it can also result in undesirable outcomes and biases that undermine policy goals. The potential conflict between the need for street-level discretion and the imperative of ensuring accountability cannot be addressed without analysing the normative dimensions of the work of street-level bureaucrats. Street-level bureaucrats “inhabit their spaces of discretion” and apply their “moral dispositions” to decide between merely following envisaged policy or expressing their personal preferences (Zacka 2017, pp. 31, 12–14).

Figure 1. Theorising street-level discretion

Source: Authors

Thus, resolving this agency–accountability trade-off is an essential managerial task in organising street-level work. There has to date been limited research on public management situations and organisational contexts where discretion is desirable and exercising judgement is important. Clearly, however, different roles and professions display different characteristics and potential for discretion. The work of waste management workers or post office clerks seems to be less ambiguous and more routine than that of caregivers, teachers, police officers or judges. Richard Matland (1995) argues that roles with low ambiguity and low conflict need much less discretion and are amenable to top-down management. But roles in healthcare or education, where the quality of services assumes ever greater importance, and where individual decision-making is an integral aspect of work, require much greater discretion and possibly a more bottom-up approach (Laitinen et al. 2018).

While there are no wide-ranging studies that outline the levers available to managers to reduce or manage discretion, recent empirical studies of street-level bureaucracy have attempted to trace the impact of various factors in managing discretion and ensuring adequate compliance with overall policy goals. Where a bottom-up perspective is favoured, there is likely to be limited usefulness in controlling discretion. Rather, the policy definition must leave considerable room for professional judgement. In such cases, street-level bureaucrats’ organisational culture and training can assume particular importance in aligning them towards policy goals. Management by relevant professionals, rather than generalists, could help prioritise the quality-of-service outcomes, and conversely an excessive focus on costs or removing the ‘professionals’ from managerial functions could well undermine service delivery (Evans 2011). Similarly, the use of key performance indicators to channel street-level bureaucrats’ decisions has been found to be counter-productive as it disrupts their initiative and nudges them towards a narrow, procedural approach, thereby reducing effectiveness (Malbon and Carey 2021).

A range of options to ensure appropriate use of discretion has been put forward. Rice (2013) argues that education and training can significantly influence the sensitisation of workers and ensure alignment with policy goals. Piore (2011) suggests that bureaucrats’ coping mechanisms could be tapped to refine policy objectives. He talks about how stimulating conversations within the organisation can uncover hidden stories and learnings, which can lead to necessary innovation and adaptation. Zacka (2017) emphasises the need for strong organisational cultures to ensure that discretion is exercised with the right moral values. Flinders (2006) offers the possibility of utilising newer forms of accountability and information flows like open meetings, user surveys, public hearings etc. that create mechanisms for downward, citizen-focused accountability instead of the traditional channels of upward-focused scrutiny.

Local governments could reduce or enlarge the room for discretion on the part of their street-level bureaucrats by controlling the resources available to them in the form of time, money, human resources and skills (Rice 2013). They could also adjust internal budget structures, making them either programme- or client-centred (Rice 2013). Better policy definition could also help to resolve the problems of divergence. Hunter et al. (2016), in the context of UK homelessness benefits, highlight how more straightforward and client-sensitive policy provisions, coupled with ensuring bureaucrats have adequate skills in analysing the various dimensions of decision-making, can vastly improve compliance. Buffat (2015) outlines the potential role of ICT in curtailing discretion by reducing bureaucrats’ capacity to manipulate information streams. However, he also acknowledges that the use of ICT in this way is limited to particular organisations and tasks: it is unlikely to hold for organisations that need to make complex judgements or resolve human conflicts.

Conclusion

Research has shown how the complex nature of street-level bureaucrats’ work inevitably gives them discretionary power. In a classic Weberian bureaucracy, this would send alarm signals, and attempts would be made to eliminate such discretion by clarifying the rules (Piore 2011). However, recent empirical evidence points towards the positive dimensions of discretion in providing agency to street-level bureaucrats to adapt policy to the local context and thereby become responsible, adaptable and flexible in addressing client needs. Given that these were the very grounds on which NPM reforms led to the reconfiguring and outsourcing of traditional state welfare functions, re-purposing bureaucracies as ‘street-level organisations’ offers an attractive possibility for today’s local governments. Such street-level organisations could allow ‘sociological’ imagination to re-enter the public policy arena, 40 years after it was largely hijacked by ‘economic imagination’ under NPM reforms (Piore 2011). However, this calls for discussion on how to empower street-level bureaucrats while retaining the strengths of democratic accountability. These debates are likely to characterise much of the public sector over the short to medium term: a revival of ‘government’ appears to be taking place, but in a conceptual vacuum that has forgotten the theoretical issues that occasioned the retreat from its traditional role in the first place.

This underscores the importance of the growing literature on street-level bureaucracy, which has picked up pace over the last few years. While the extant literature has laid out the various issues and implications of street-level divergence, further research is required to develop a theory of street-level bureaucracy suited for the post-NPM local governance context.

Firstly, research is required to identify areas and contexts where street-level divergence is beneficial as against situations where it could undermine policy goals. While Zacka’s (2017) work has provided a useful starting point for a normative theory of street-level bureaucrats, its application to different contexts and the multifarious roles of local government officials needs to be explored. Secondly, there is a need for further empirical work on processes for managing street-level divergence and aligning discretion to policy goals; specifically, how organisational culture and context can orient street-level bureaucrats towards necessary policy compliance. There is also room for empirical research to establish how organisational resources can be leveraged to increase the agency of street-level bureaucrats. Thirdly, there is a need to explore how the use of networks and collaborative governance structures has shifted the problem of policy divergence beyond the traditional boundaries of the state, raising new challenges for street-level bureaucrats who are now supposed to manage the agency–accountability conundrum with an array of third-party, non-governmental, private sector and civil society stakeholders. Fourthly, there is scope for further research on the role ICT and e-governance networks could play in reducing street-level divergence. Finally, there is a need to formulate models and theories to account for all the varied dimensions of street-level divergence. Such theories could propose a decision matrix for managers to resolve the inherent dilemmas and attune performance management systems towards specific organisational contexts and goals.

Through recent research, a start has been made towards understanding how agency–accountability trade-offs in local governance might be resolved. However, empirical evidence to inform strategies that local government officials could use in different contexts remains scarce. Without more evidence, conclusions around how best to curtail or enhance discretion in particular organisations and circumstances must remain tentative.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors wish to thank the Indian Institute of Management Calcutta for providing financial support for this study.

References

Aaj Tak (2021) Woman dies after hospital refuses bed reserved for VIP. Aaj Tak, 27 May 2021. Available at: https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x81js8m. [Accessed 28 March 2022].

Aiyar, Y. and Walton, M. (2015) Rights, accountability and citizenship: India’s emerging welfare state. In: Deolalikar, A.B., Jha, S. and Quising, P.F. (eds.) Governance in developing Asia, (pp. 260–295). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Arellano-Gault, D., Demortain, D., Rouillard, C. and Thoenig, J.(2013) Bringing public organization and organizing back in. Organization Studies, 34 (2), 145–167. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840612473538

Assadi, A. and Lundin, M. (2018) Street-level bureaucrats, rule-following and tenure: how assessment tools are used at the front line of the public sector. Public Administration, 96 (1), 154–170. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12386

Bagchi, S. and Chakrabarti, B. (2021) Organizational forgetting in local governments: a study from rural India. Journal of Organizational Ethnography, 10 (3), 289–302. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOE-11-2020-0049

Berenschot, W. (2010) Everyday mediation: the politics of public service delivery in Gujarat, India. Development and Change, 41 (5), 883–905. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.2010.01660.x

Bharali, I., Kumar, P. and Selvaraj, S. (2020) How well is India responding to COVID-19? Brookings: Future Development, 2 July 2020. Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2020/07/02/how-well-is-india-responding-to-covid-19/ [Accessed 28 March 2022].

Brandsma, G.J. and Adriaensen, J. (2017) The principal–agent model, accountability and democratic legitimacy. In: Delreux, T., Adriaensen, J. (eds.) The principal agent model and the European Union, (pp. 35–54). Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-55137-1_2

Brulé, R. (2015) Accountability in rural India: local government and social equality. Asian Survey, 55 (5), 909–941. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26364318

Buffat, A. (2015) Street-level bureaucracy and e-government. Public Management Review, 17 (1), 149–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2013.771699

Dan, S. and Pollitt, C. (2015) NPM can work: an optimistic review of the impact of New Public Management reforms in central and eastern Europe. Public Management Review, 17 (9), 1305–1332. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2014.908662

Evans, T. (2011) Professionals, managers and discretion: critiquing street-level bureaucracy. British Journal of Social Work, 41 (2), 368–386. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcq074

Farazmand, A. (2010) Bureaucracy and democracy: a theoretical analysis. Public Organization Review, 10, 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-010-0137-0

Felts, A.A. and Jos, P.H. (2000) Time and space: the origins and implications of the New Public Management. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 22 (3), 519–533. https://doi.org/10.1080/10841806.2000.11643469

Flinders, M. (2006) Public/private: the boundaries of the state. In: Hay, C., Lister, M. and Marsh, D. (eds.) The state - theories and issues, (pp. 223–247). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gofen, A. (2014) Mind the gap: dimensions and influence of street-level divergence. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 24 (2), 473–493. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mut037

Gofen, A., Meza, O. and Chiqués, E.P. (2022) When street‐level implementation meets systemic corruption. Public Administration and Development, 42, 72–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.1970

Grant, M. J. and Booth, A. (2009) A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 26, 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

Gupta, S. and Hollingsworth, J. (2020) They were arrested for breaking lockdown rules. Then they died in police custody. CNN, 2 June 2020. Available at: https://edition.cnn.com/2020/07/01/asia/tamil-nadu-deaths-custody-intl-hnk/index.html [Accessed 28 March 2022].

Hansen, J.R. and Ferlie, E. (2016) Applying strategic management theories in public sector organizations: developing a typology. Public Management Review, 18 (1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2014.957339

Hoag, C. (2011) Assembling partial perspectives: thoughts on the anthropology of bureaucracy. Political and Legal Anthropology Review, 34 (1), 81–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1555-2934.2011.01140.x

Hoag, C. (2014) Dereliction at the South African Department of Home Affairs: time for the anthropology of bureaucracy. Critique of Anthropology, 34 (4), 410–428. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308275X14543395

Hong, S. (2021) Representative bureaucracy and hierarchy: interactions among leadership, middle-level, and street-level bureaucracy. Public Management Review, 23 (9), 1317–1338. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2020.1743346

Hood, C. and Dixon, R. (2015) What we have to show for 30 years of new public management: higher costs, more complaints. Governance: An International Journal of Policy, Administration, and Institutions, 28 (3), 265–267. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12150

Hunter, C., Bretherton, J., Halliday, S. and Johnsen, S. (2016) Legal compliance in street-level bureaucracy: a study of UK housing officers. Law & Policy, 38 (1), 81–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/lapo.12049

Hupe, P. (ed.) (2019) Research handbook on street-level bureaucracy. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Jauregui, B. (2014) Provisional agency in India: Jugaad and legitimation of corruption. American Ethnologist, 41 (1), 76–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/amet.12061

Justesen, M.K. and Bjørnskov, C. (2014) Exploiting the poor: bureaucratic corruption and poverty in Africa. World Development, 58, 106–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.01.002

Kencana, N. (2017) ‘Street-level bureaucracy: bureaucratic reform strategies initiated from bottom level’. Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, 163, 207–211.

Kjaerulff, J. (2020) Discretion and the values of fractal man. An anthropologist’s perspective on ‘street-level bureaucracy’. European Journal of Social Work, 23 (4), 634–644. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2018.1553150

Laitinen, I., Kinder, T. and Stenvall, J. (2018) Street-level new public governances in integrated services-as-a-system. Public Management Review, 20 (6), 845–872. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2017.1340506

Lavee, E. and Cohen, N. (2019) How street‐level bureaucrats become policy entrepreneurs: the case of urban renewal. Governance, 32 (3), 475–492. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12387

Lipsky, M. (1969) Toward a theory of street-level bureaucracy. IRP Discussion Papers. Madison, WI: Institute for Research on Poverty (IRP), University of Wisconsin.

Lipsky, M. (2010) Street-level bureaucracy: dilemmas of the individual in public service. 30th Anniv ed. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Lipsky, M. (2021) A note on pursuing work on street‐level bureaucracy in developing and transitional countries. Public Administration and Development, 42, 11. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.1969

Malbon, E. and Carey, G. (2021) Market stewardship of quasi‐markets by street level bureaucrats: the role of local area coordinators in the Australian personalisation system. Social Policy & Administration, 55 (1), 18–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12607

Mathur, N. (2016) Paper tiger: law, bureaucracy and the developmental state in Himalayan India. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Matland, R.E. (1995) Synthesizing the implementation literature: the ambiguity-conflict model of policy implementation. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 5 (2), 145–174. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a037242

Maynard-Moody, S. and Musheno, M. (2003) Streetwise workers: enacting identities and making moral judgment. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Mukhopadhyay, A. (2021) Nurses in Indian villages struggle to cope with pandemic-related pressures. DW.com, 8 June 2021. Available at: https://www.dw.com/en/india-covid-nurses-under-pressure/a-57813736 [Accessed 28 March 2022].

Murphy, M. and Skillen, P. (2015) The politics of time on the frontline: street level bureaucracy, professional judgment, and public accountability. International Journal of Public Administration, 38 (9), 632–641. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2014.952823

Nilsen, A.G. (2021) India’s pandemic: spectacle, social murder and authoritarian politics in a lockdown nation. Globalizations, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2021.1935019

Pampackal, A.J. (2019) Implementers of law or policymakers too? A study of street-level bureaucracy in India. In: Pellissery, S., Mathew, B., Govindjee, A. and Narrain, A. (eds.) Transformative law and public policy, (pp. 171–188). London: Routledge.

Piore, M.J. (2011) Beyond markets: sociology, street-level bureaucracy, and the management of the public sector. Regulation & Governance, 5 (1), 145–164. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-5991.2010.01098.x

Pritchett, L., Woolcock, M. and Andrews, M. (2013) Looking like a state: techniques of persistent failure in state capability for implementation. The Journal of Development Studies, 49 (1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2012.709614

Raaphorst, N. and Groeneveld, S. (2019) Discrimination and representation in street-level bureaucracies. In: Hupe, P. (ed.) Research handbook on street-level bureaucracy, (pp. 116–127). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Rice, D. (2013) Street-level bureaucrats and the welfare state toward a micro-institutionalist theory of policy implementation. Administration & Society, 45 (9), 1038–1062. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399712451895

Smart, A. (2018) The unbearable discretion of street-level bureaucrats. Current Anthropology, 59 (18), 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1086/695694

The India Forum (2021) India and the pandemic: the first year. Orient BlackSwan.

Tummers, L. and Bekkers, V. (2014) Policy implementation, street-level bureaucracy, and the importance of discretion. Public Management Review, 16 (4), 527–547. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2013.841978

Tuohy, C.H. (2003) Agency, contract, and governance: shifting shapes of accountability in the health care arena. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 28 (2–3), 195–216. https://doi.org/10.1215/03616878-28-2-3-195

Zacka, B. (2017) When the state meets the street: public service and moral agency. Harvard: Harvard University Press.

1 Introduced in the 1980s, the New Public Management (NPM) is an approach to running public service organisations in a business-like manner by borrowing private sector management models in order to improve efficiency, customer service and accountability.

2 ‘Other-serving’ divergence is motivated by the bureaucrat’s desire to serve/benefit the clients more effectively than explicitly allowed by the policy.

3 Dissent shirking refers to the behaviour of street-level bureaucrats who may shirk not only to minimise work but also as a tool of resistance to policy goals or the specific policy approach.