Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance

Issue 26

May 2022

RESEARCH AND EVALUATION (PEER REVIEWED)

Participation of Chiefs in Decentralised Local Governance in Ghana

Emmanuel Debrah

Department of Political Science, University of Ghana, PO Box LG64, Legon, Ghana,

edebrah@ug.edu.gh

Corresponding author: Emmanuel Debrah, Department of Political Science, University of Ghana, PO Box LG64, Legon, Ghana, edebrah@ug.edu.gh

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi26.8150

Article History: Received 06/12/2020; Accepted 03/04/2022; Published 31/05/2022

Citation: Debrah, E. 2022. Participation of Chiefs in Decentralised Local Governance in Ghana. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, 26, 53–73. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi26.8150

© 2022 by the author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

(CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties

to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the

material for any purpose, even commercial, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Abstract

This article examines the lack of participation of chiefs in Ghana’s decentralised local governance. After analysing data from interviews with 280 respondents, personal observations and relevant literature, the study found that chiefs are core members of neither Ghana’s district assemblies (DAs) nor their subsidiary structures, and have no formal role in local development. Chiefs’ formal exclusion from the current local government system has been attributed to the idea that the chieftaincy institution is at variance with democratic decentralisation. Also, the protracted communal conflicts that have devastated many communities, and the disputes, accusations of fraud and litigation which have characterised land sales and acquisitions in the country, have their roots in chieftaincy rivalries. Nevertheless, given that chieftaincy is entrenched in Ghanaian society, chiefs’ closeness and familiarity with rural people in their area, and their cooperation with DA members to aid the performance of the DAs (albeit with some challenges), the study concludes there is a need to re-examine the current decentralisation policy to enable chiefs’ participation. Options proposed include reserving for chiefs the 30% of DA seats currently nominated by the president; appointing paramount chiefs as ceremonial heads of the DAs with the right of address; or ceding some of the non-representation functions of elected DA members to chiefs in order to support local democracy and development.

Keywords

Decentralisation; Chiefs; District Assemblies; Local Development; Ghana

Introduction

There is no doubt that decentralisation is increasingly favoured by many developing countries as the mode of governance through which grassroots democracy can best be nurtured and consolidated. In many African countries such as Nigeria, South Africa and Democratic Republic of Congo, participation by local people in decision-making has become a central feature of their governance architecture (Wunsch 2001; Englebert and Kasongo 2016). Interest in democratic decentralisation has been associated with donor agencies’ pressure on African governments for political and economic reforms since the early 1990s, but the movement goes back further than that: the slogan ‘Power to the people’ already formed part of the political rhetoric of some regimes in the mid-1980s (Ayee 1994). However, in Ghana where the Provisional National Defence Council (PNDC) regime had adopted democratic decentralisation to bolster its legitimacy, the implementation process nevertheless actually resulted in recentralisation (Ayee 1994). Therefore, in their determination to force a departure from previous centralised decision-making regimes, Western governments and their donor agencies made decentralisation a key condition for financial assistance in the developing world (Dickovick 2014; Debrah 2014). They argued that decentralisation would facilitate greater participation of communities in problem analysis, and in project identification, planning and implementation, which in turn would increase ownership of local development in the neo-democracies (Grindle 2007). African governments that needed funds to reinvigorate their ailing economies acceded to this pressure, despite traditional authorities (chiefs) often agitating for restoration of their historical role in local governance (Taabazuing 2010: Smoke and Matthew 2011).

In Ghana, local democracy was enshrined in the 1992 Constitution and the subsequent Parliamentary Act 462 of 1993 (amended in 2016 as Act 936). A key objective of the country’s decentralisation policy is the fostering of close and cordial interactions between the central government and citizens to advance local development. Also, because decentralisation is rooted in the principle of subsidiarity, it was expected that its practice would stimulate grassroots accountability, equitable distribution of resources, power-sharing and inclusive participation by all socio-economic groupings in the local decision-making process (Ayee 1994; Antwi-Bosiako 2010; Asante and Debrah 2019). A key goal of democratic decentralisation is to bring together local institutions and differing actors and interests to accomplish community-determined objectives (Debrah 2016). However, after more than two and a half decades of decentralisation practice, it is timely to assess the extent to which grassroots participatory democracy has flourished. Has the decentralisation policy, framed on the basis of the Western local government’s elective principle and Weber’s ‘legal-rationality’1 (Guzmán 2015), effectively integrated all identifiable groups and local actors, notably traditional leaders who derive their authority from sacred oral traditions and customs, into decentralised local governance? Or have chiefs played no formal role in the local decision-making and development process and if so, what factors influenced the decision to exclude them from the district assemblies (DAs) set up under the 1992 Constitution? Should chiefs be allowed to play a role in decentralised local governance? What lessons have been learned?

Against this backdrop, this article is structured into six sections. The first outlines the scope and methodology of the research. The second is devoted to the conceptual imperatives of decentralisation to provide a context for the analysis. The third examines chieftaincy and decentralisation in historical perspective to ascertain whether chiefs have played any role in previous local government reforms. The fourth analyses the nature and dynamics of the current decentralisation policy in order to determine whether or not chiefs are able to participate in the DAs. The fifth examines the justifications for denying chiefs a formal role in the DAs. The last considers reasons why chiefs should participate in decentralised local governance and the lessons derived from this study.

Scope and methodology

This study sought to obtain new insights about the participation (or otherwise) of chiefs in Ghana’s decentralised local governance. It is based on primary data collected from January 2019 to February 2020, with follow-ups in May 2020 and July–August 2021. The study employed a qualitative method to analyse interactions between key variables and answer ‘how’ and ‘why’ questions concerning chiefs’ participation. In particular, the in-depth interviews and ethnographic approach created room to follow up and probe for clarification of ambiguous responses (Lavrakas 2008). The researcher made follow-up contacts with several key respondents to clarify opinions on issues at various phases of data collection, processing and analysis.

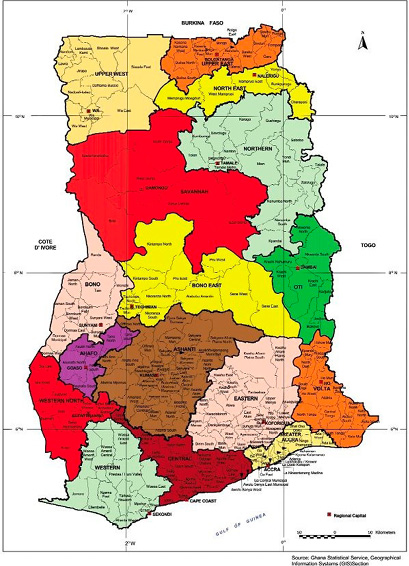

In all, 300 respondents2 were selected from 12 DAs in six of Ghana’s 16 regions, namely Ashanti, Eastern, Volta, Northern, Central and Greater Accra (see Figure 1 and Table 1). These regions reflect the geopolitics of the country: the Ashanti and Eastern, and Volta and Northern, regions are the respective strongholds of the ruling New Patriotic Party and opposition National Democratic Congress; while the Central and Greater Accra regions swing between the two. Geographically, the Greater Accra, Volta and Central regions are on the coast in the south, the Eastern and Ashanti regions are in the central forest belt, and the Northern region is in the dry savannah zone of the country.

Figure 1. Map of Ghana showing its 16 administrative regions and districts

* Ga South was recently elevated to a municipality, but apart from the size of the population, its level of development makes it a relatively rural district.

DAs were then chosen from rural areas under the traditional jurisdiction of divisional chiefs and sub-chiefs, who regularly interact with local people. Two were randomly selected in each region by blindfolding a research assistant to select from the gazetted lists of DAs published by the Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development (see Table 1). The same procedure was followed to pick the particular communities (towns and villages) to be studied in each DA, although due to issues of remoteness, poor accessibility (road networks and telephone/internet connectivity) and inadequate funds, the choice of communities was restricted to those that were accessible by road and telephone. Nevertheless, effort was made to ensure that the choice of communities included those headed by divisional chiefs (ahenfo) in the case of towns, and sub-chiefs (adikuro) for villages.

As well as chiefs, respondents included members of parliament3 (MPs), DA members, local government and chieftaincy secretariat officials, academics, civil society activists, and ordinary citizens4 resident in the selected communities.

Initially, 120 chiefs from towns and villages in the districts (ten each from the 12 DAs) were chosen for interviews. However, only 100 chiefs availed themselves of the opportunity for interview and interactions with their elders,5 due to customary and personal engagements. In addition, 12 district chief executives (DCEs), 12 assembly members (AMs) and 12 MPs were selected – the AMs randomly, because there are many in each DA. DCEs, MPs and AMs all have direct contact with chiefs at the community level.

Another 24 respondents included academics, representatives of civil society organisations (CSOs), and officers of Ghana’s Local Government Service (LGS) and Chieftaincy Secretariat. While the CSOs are many and diverse in their focus, only well-known think-tanks and advocacy groups with an active role in the governance sphere, and a deeper knowledge of chieftaincy and DAs, were selected, namely: the Centre for Democratic Development (CDD), the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA), the Institute of Democratic Governance (IDEG), the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung (KAS) and the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung (FES).

In the case of the academics, the respondents were selected from accredited tertiary institutions in Accra where all were engaged in teaching or research in the areas of decentralised local governance, traditional governance, democratic governance, African politics, political science or public administration. Only officers of senior rank in the LGS and CS were identified for interview. Thus, all respondents from academia, CSOs, LGS and CS have in-depth knowledge and understanding of chieftaincy and local governance issues.

To balance this set of interviewees, and in order to ascertain views from those at the grassroots whose lives are affected by chiefs’ activities, 120 ordinary residents (10 from each DA) were also selected for interview from the Electoral Commission (EC) published lists of registered voters as at January 2019 (see Table 1). Again, the same simple random technique was applied to choose five respondents each from a town and village. More than two-thirds (76) of the respondents were males while 44 were females. Even though approximately 51% of the population is female, only a few bold women volunteered to participate in the interviews.

The primary information for this study was collected through face-to-face and telephone interviews, using semi-structured questions to explore whether chiefs have been involved in the DAs or not, why they have been excluded (if that is the case), and views on the need or otherwise for their participation in local governance, as well as the value and nature of their daily interactions with local people. The data obtained through the in-depth interviews and field notes (personal observations/direct contacts) were transcribed and organised into salient analytical themes. Secondary data included reviews of theoretical and empirical literature on chieftaincy and decentralisation.

The theoretical imperative of decentralisation

Despite decentralisation’s prominence in the field of governance, navigating its practicalities has often proved problematic. In the discourse of public policy and administration, decentralisation is understood as the shifting of authority to plan, make decisions and manage public functions from a higher level of government to organisations or agencies at a lower level (Smith 1985; Mawhood 1993; Cheema and Rondinelli 2007). In the realm of politics, decentralisation refers to the transfer of decision-making powers from central government to sub-national bodies (Smith 1985; Wunsch 2014).

Scholars have observed that decentralisation is a hydra-headed concept because it manifests in varying forms. One dimension is devolution, which refers to the transfer of specified responsibilities and resources from the central government to local governments or communities that are represented by their own lay or elected officials (Turner and Hulme 1997; Conyers 2007; Wunsch 2014). Devolving powers to lower levels often involves the creation of a realm of decision-making in which a variety of lower-level actors can exercise some autonomy.

A second dimension, administrative decentralisation, is viewed as the shifting of responsibility in the provision of public services within or between different levels of government (Turner and Hulme 1997; Ribot 2002; Cheema and Rondinelli 2007). Two aspects have been identified, namely de-concentration and delegation. The former is the transfer of state responsibilities and resources from central ministries and agencies in the nation’s capital to their peripheral institutions within the same administrative system. The latter, delegation, involves shifting decision-making responsibilities from superior authorities to subordinates with a substantial degree of autonomy, but which remain subject to ‘upward’ accountability (Smith 1985; Cheema and Rondinelli 2007). De-concentration is often considered to be the weakest form of decentralisation, because it does not involve any real transfer of power; and devolution is perceived as more robust than decentralisation generally in that it does grant additional powers to local governments.

A third dimension, fiscal decentralisation, is the transfer of financial resources from the central government to local government bodies. In fiscal decentralisation, local governments are given powers over taxation, development planning, budgeting and spending of revenues generated within their jurisdictions (De Mello et al. 2001; Smoke 2015). Smith (1985) notes that the various forms of decentralisation are not mutually exclusive but provide a matrix of potential relationships; while Manor (1999) argues that achieving successful decentralisation entails a mixture of all dimensions.

Decentralisation is often assumed to produce important outcomes such as greater popular participation in local decision-making, efficiency in service delivery, effective local resource mobilisation, rural development, and oversight of public office holders (Mawhood 1993; Wunsch 2001; Conyers 2007) The empirical literature also posits that decentralisation leads to effective checks against corruption (Fisman and Gatti 2002; Fjeldstad 2004), poverty reduction (Dillinger 1994; Crook and Sverrisson 2001; Braathen 2008; World Bank 2008), and conflict prevention (Sasaoka 2007). On the other hand, it has also been said to engender elite capture, inequality in development and clientelism (Wunsch 2001; Dickovick and Riedl 2014).

Importantly, it has been argued that the creation of elected structures at the local level helps to nurture democratic norms and values among the citizenry, which then grow into national democracy (Mawhood 1993; Debrah 2014). This way, decentralisation is believed to foster democratisation by giving citizens and local political actors access to decision-making processes (Hadiz 2004; Green 2015), and by promoting inclusivity in local decision-making.

Chieftaincy and decentralisation in historical perspective

Until the British conquest of the Gold Coast and introduction of a Western local government system, local governance was firmly entrenched under the tutelage of chiefs: “persons who, hailing from the appropriate families and lineages, have been validly nominated, elected or selected and enstooled/enskinned/installed as chiefs or queen-mothers in accordance with the relevant customary law and usage” (Republic of Ghana 1992, p. 153). In the centralised fiefdoms such as the Asante kingdom that had a formalised system of political authority, power to govern localities flowed downward from the supreme ruler (asantehene) to the paramount chiefs (amanhene) at the state (oman) level; further to the divisional chiefs (ahenfo) who exercised authority over small communities; and then down to the sub-chiefs (adikuro) and heads of villages (Busia 1968; Assimeng 1996; Hutchful 2002). The source of authority of the chiefs to govern localities was derived from custom and sacred traditions. In 1887 when the British passed the Native Jurisdiction Ordinance to legitimise their role under indirect rule – a colonial policy that entrusted British local administration to the hands of existing native authorities under close supervision – chiefs carried out duties such as collection of taxes and maintenance of law and order in their traditional areas (Busia 1968; Ayee 1994).

Over time, chiefs were allowed to execute minor public works like the construction of village markets, feeder roads, public toilets and school buildings (Busia 1968; Ayee 1994). To enforce law and order, chiefs maintained native courts or tribunals to adjudicate on matrimonial disputes, family feuds, and disagreements relating to land ownership. In recognition of the usefulness of the native authorities to its administration, the British colonial government went as far as appointing ‘warrant chiefs’ in communities that did not have pre-existing traditional authorities (Awedoba 2006; Tonah 2012).

However, in local government reforms that preceded independence, the passage of the Native Authority Ordinance of 1944 (a measure to transform local government from a chieftaincy-based to a democratically-elected system) made the enstoolment of chiefs dependent on the approval of the Governor of Ghana. In other words, the ordinance mandated that the exercise of native jurisdiction by chiefs would be dependent upon prior recognition by the Governor and the willingness of the former to act in conformity with the policies of the latter (Gold Coast, 1944). Although chiefs were still selected according to customary practices, the ordinance undermined their authority and their ability to mobilise the local people for development because their subjects came to perceive them as stooges of the Governor. As a result, chiefs lost some of the respect and confidence of their people, despite receiving support for their involvement in local development (Ayee 1994; Ray 2003; Taabazung 2010).

After Ghana’s independence on 6 March 1957, chiefs’ ability to participate in local government reforms was greatly circumscribed due to two inter-related factors: the adoption of one-party rule with its concomitant centralised decision-making, and the ‘anti-chief’ stance taken by some of the subsequent regimes (Chazan 1983; Rathbone 2000). For instance, soon after independence Kwame Nkrumah’s government embraced the single-tier state structure – a centralised governance system that was justified as a necessary measure for the rapid socio-economic transformation agenda (Ayee 1994; Conyers 2007). Nkrumah contended that grassroots participation in unitary states such as Ghana works best for the people when the central government controls the process with support from technocrats rather than chiefs (Ray 2003; Adjei et al. 2017). Consequently, he passed the Local Government Act 54 of 1961 which stripped chiefs of their positions (previously one-third of the total number of seats) in district councils, and appointed civil servants (who were largely party yes-men) to manage local governments even though, unlike chiefs, they lacked direct contact with the people (Rathbone 2000; Ray 2003; Taabazung 2010).

Although the civilian regimes of the Progress Party and People’s National Party of the Second Republic (1969–1972) and Third Republic (1979–1981) endeavoured to restore chiefs to the local councils, the subsequent PNDC government led by Jerry Rawlings (1982–1992) removed their ability to control local governance – only the statutory recognition of their ceremonial authorities remained intact (Ayee 1994; Crawford 2004). The PNDC’s attacks on chiefs claimed they were a rural elite who had denied citizens’ rights at the grassroots. The PNDC therefore created ‘Committees for the Defence of the Revolution’ (CDRs) to take over local government functions. The ensuing conflicts deepened the alienation of chiefs from local governance: while the CDRs regarded chiefs as the embodiment of traditional power and arrogance that must be confronted, the chiefs saw the CDRs as opportunists who should be prevented from overturning the established order (Ayee 1994; Ray 2003; Taabazung 2010). Therefore, the decision to return Ghana to constitutional rule in 1992 was greeted with great enthusiasm by the chiefs because of their optimism that they would regain their lost glory (interview: lecturers in African studies and political science, Accra, February 2019). However, this optimism was to prove ill-founded.

Nature and dynamics of decentralisation in Ghana

This section examines the structure and composition of Ghana’s district assemblies (DAs) in order to explore the extent to which chiefs have played a role in the present system of decentralised local governance. The decentralisation policy adopted in 1993 under Act 462 (amended under Act 936 of 2016) is a three-tier system, comprising regional coordinating councils (RCCs), DAs and unit committees (UCs). This reflects the regional, district and sub-district complexion of the unitary state (interview: lecturer in public administration, Accra, March 2019). The RCC is at the apex of the local government structure and performs administrative responsibilities of central government rather than exercising devolved powers. It is composed of the regional minister as chairperson, a deputy, the presiding member and the chief executive officer of each district in the region, and two chiefs nominated by the regional house of chiefs. It is responsible for monitoring the use of allocated funds, reviewing all activities of DAs and public service institutions, managing and resolving conflicts among the agencies of the central government, and settling disputes in the region (Republic of Ghana 1993). It coordinates district development plans and integrates the spatial and sectoral plans of ministries and sector agencies by ensuring that they are compatible with national development objectives, and also has power to evaluate the performance of DAs in respect of the formulation of plans for the provision of basic infrastructure (Republic of Ghana 1993).

Below the RCCs are metropolitan, municipal and district assemblies (MMDAs). The type of assembly for a given area is based on demographic conditions, settlement characteristics and levels of socio-economic development. For instance, a locality is designated as a metropolitan assembly when it has a population of over 250,000, well-developed infrastructure, and industrial and commercial activities. A municipal assembly is a one-town assembly having a population of 95,000 or more, plus relatively well-developed infrastructure and commercial activities. On the other hand, a DA is a group of settlements in a more-or-less rural area with a minimum population of 75,000. Despite these distinctions, the three types are essentially equal in power and functions (Republic of Ghana 1993). The DAs – the focus of this paper – constitute the hub of political decentralisation in rural areas and are therefore the key institutions for decision-making at the local level. They have deliberative, legislative and executive powers and are responsible for the promotion of local cohesion, for integration, and for keeping the peace and maintaining law and order. They have authority to initiate and implement development programmes (Republic of Ghana 1993, 2016). To this end, they are empowered to mobilise human and fiscal resources, prepare composite budgets and spend funds. Each DA is composed of a chief executive, 70% elected members, and 30% members appointed by the president, plus the MP who represents the constituency in the national legislature6 (Republic of Ghana 1993).

DAs are further subdivided into area councils comprising not more than five AMs and ten members drawn from UCs in the area. The UC is the basic building block of the local government system. It consists of a group of settlements with a population of 500–1,000 in rural areas, and 1,500 in urban areas. Each UC is made up of five members who are directly elected by the people (Republic of Ghana 2010). These lower structures are the rallying points of popular support for local governance. They keep records of all rateable persons and properties in their locality; assist any person authorised by the DA to collect revenues; name streets, number buildings, and plant trees to protect streets; prevent and control fire outbreaks; enforce by-laws; and mobilise people for development (Republic of Ghana 2010).

Exclusion of chiefs from the DAs

The composition of the DAs examined does not include chiefs. No provision is made for the mandatory inclusion of chiefs among the 30% of DA members appointed by the president, even though the theoretical criterion for recruitment is persons with the experience and competence to contribute to local government; and few chiefs have been appointed by successive presidents (see Table 2).

By contrast, the majority of appointees have been party supporters (‘yes-men’). This suggests that political (partisan) considerations rather than experience and organisational capabilities (peculiar qualities chiefs often possess) are the dominant influence. Even at the sub-district levels (area councils and UCs) where communal deliberations have taken place, the chiefs have not been included (interview: chiefs – Doryumu, Fotobi, Nyarkrom, Adiembra and Asuso, April 2019).

Even where there is a legal basis for chiefs’ involvement in aspects of local decision-making, they have been side-lined. For instance, Acts 462 and 936 provide that the appointment of 30% of DA members should take place after consultations with traditional rulers (Republic of Ghana 1993, 2016). Despite this legal provision, however, “the appointments have always proceeded without prior consultations with chiefs” (interview: chief, Asamanya, September 2019). Interactions with chiefs indicated that the government had notified them about who were appointed after they have been sworn into office.6 Also, the intense lobbying that typically precedes the nominations of DCEs had to date, occurred mainly in the chambers of regional ministers and the sector minister, political party headquarters and constituency party offices rather than the palaces of chiefs (interview: chiefs – Kunkpano, Sambu, Akuase and Kotwea, September 2019).

A = Chiefs

B = Party supporters

Source: Field interviews, January 2019–February 2020

In the performance of their statutory functions and as necessary for community development, the 70% of DA members who are directly elected based on universal adult suffrage are required by law to engage in broad consultations with all local constituents (Republic of Ghana 1993, 2016). For instance, an elected AM is mandated to hold periodic public meetings to solicit opinions of the electorate and other interest groups on community needs and concerns before they are forwarded to the DA for resolution (interview: official of local government service, Accra, June 2019). However, the law is silent on the accountability of the 30% appointed members: and respondents in this study believed that, due to the nature of their recruitment, in practice they are individually accountable to the president rather than to local people (interviews: MP for Ashanti Akim North and CDD programme officer, Accra, July 2021).

Among the local constituents whose opinions must be considered by the elected AMs are traditional authorities/chiefs. However, in practice, community engagements have failed to capture chiefs’ particular concerns (interview: chiefs – Vokpo, Kunkpan, Kasuliyili, Tali, Aveme, Ziofe, September 2019). Across several communities, the researcher learned that the chiefs have not been part of the groups the AMs have mobilised in the community decision-making process, albeit the AMs claim that the neglect is not deliberate. Despite the fact that, by custom, chiefs cannot attend gatherings that are controlled by their subjects, AMs have not treated chiefs as a priority constituency that should be given ‘special’ attention (interview: retired teacher, Doryumu; farmers – Apoli and Fotobi, April 2019). Also, whereas in the past announcements about community gatherings had been disseminated from chiefs’ palaces, AMs in some cases now resort to modern technology such as social media or publication of written notices, thereby de-emphasising the use of the gong-gong7 (chiefs’ traditional mechanism to rally and assemble the people for community activities), although it does persist in some areas (interview: chiefs – Asuso, Nyarkrom, Odumase and Adiembra, April 2019).

Under the current decentralisation, the DAs are responsible for the promotion of peace, unity, social cohesion and general security of the community. To this end, district security committees (DISECs) have been created (Republic of Ghana 2016). While members are drawn from several state agencies and departments, there is no reference to the inclusion of chiefs in the promotion of unity, social and civil order. Instead, the DISEC, which is headed by the DCE, sits within the DA bureaucracy.8 Consequently, the consultations that have taken place with other state institutions regarding how to manage conflicts and crimes, and promote general security in communities, have “overlooked chiefs’ expertise in security matters and the promotion of peace” (interview: CDD programme officer – Accra, October 2019). Similarly, other sub-structures of the DAs for local decision-making such as the executive committee9 and its sub-committees10 that are responsible for problem identification, aggregation and processing have no representation from chiefs (Republic of Ghana 1993, 2016), and critical deliberations and decisions in respect of community development are made without their participation (interview: Islamic imam – Tali; teachers – Kasuliyili and Kunkpano, September 2019).

Furthermore, it has been argued that the assignment of two representatives from the regional house of chiefs to the RCC does not address this marginalisation of chiefs. This is because the RCC is a body that performs administrative responsibilities rather than a chamber for grassroots participatory decision-making, even though it oversees the DAs. Therefore, the inclusion of chiefs on the RCC only makes for effective regional administration. Besides, in the traditional establishment, paramount chiefs who make up the regional and national houses of chiefs tend to influence society and policy at the highest (national) levels, while the daily lives of local people are shaped and directed by the divisional, sub-chiefs and village heads (ahenfo and adikro) whose operational jurisdictions form part of the DAs but who have been largely excluded at that level (interview: retired civil servant – Hwidiem; headmaster of basic school – Kokrobitey, April 2019).

Why have chiefs been excluded from the district assemblies?

What has informed the decision to circumscribe chiefs’ role in the current decentralised local governance? What reasoning has led to the relegation of chiefs to the background? Part of the answer relates to the customs, traditions and norms governing chieftaincy. The consensus among respondents is that chiefs have been pushed away from local governance because chieftaincy is incompatible with demands of modern local government. This view is captured by a respondent, “Ghana’s local government is pivoted on democratic decentralisation that, in turn, thrives on the elective principle – but as you know, our customs frown on chiefs’ engagement in open contests for public office positions” (interview: lecturer in African studies, Accra, February 2020). Despite Drah’s (1987) view that the selection of chiefs in Akan society conforms to democracy, many respondents alluded to the fact that the chieftaincy customs do not permit chiefs to engage in elections in which they would compete with their subjects for vacant positions (interview: lecturer in political science; MP for Birim South, Accra, February 2020). According to a respondent, “[in] a scenario where chiefs compete with their subjects in the DA elections and lose the contest, the humiliation would undermine chiefs’ ability to continue to occupy the stool/skin” (interview: catechist, Kasuliyili, September 2019). Furthermore, given that “chieftaincy is structurally patriarchal, and does not sustain democratic principles of equality and equity that form the basis of modern local government, if chiefs had to elect representatives to the DAs, queen-mothers11 would be marginalised as well” (interview: lecturer in African studies, Accra, February 2020).

Similarly, some respondents perceive chieftaincy to be at variance with democratic accountability – sanctions, checks, dissents and control that are the pillars on which the DAs thrive (interviews: MPs for Tolon and Asante Akim North; FES programme officer, Accra, February 2020). This view has been echoed by a key respondent: “The issue of ‘infallibility’ of chiefs would undermine the enforcement of accountability of local leaders to the people” (interview: lecturer in political science, Accra, February 2020). On the other hand, Logan (2011) and Williams (2010) have noted that chieftaincy in Africa fosters local accountability.

Another factor is the involvement of chiefs in Ghana’s protracted communal conflicts. Interactions with respondents suggest that chiefs are directly or indirectly linked to the communal conflicts that have engulfed the country for many years (interview: teacher, Akwasa; church pastor, Zandor; AM Kunkpano; carpenter, Kokrobitey, September 2019). For instance, expressing an opinion on this issue, a key respondent noted: “Most of the recent inter-ethnic rivalries that involved opposing groups vying for control over traditional sacred sites have their roots in chieftaincy succession disputes” (interview: CDD programme officer, Accra, February 2020). Examples cited spanning the past 30 years included: renewed intra-ethnic conflicts linked to chieftaincy in the Northern region of the country, including the Konkomba-Nanumba war of 1994–1995; the Nawuri-Gonja and Mamprusi-Kussasi conflicts; and the Dagomba intra-clan disputes that peaked in 2002 and led to the gruesome murder of the Ya-Na (paramount chief of the Dagombas). Similarly, chieftaincy succession disputes involving the Ga Mantse, Alavanyo, Anlo and Akim Kotoku groups have been recorded in the southern sector of the country (interview: lecturers in African studies and political science, Accra, February 2020).

Regrettably, it is ordinary citizens who suffer the consequences of these conflicts – deaths, impoverishment of the rural poor including vulnerable women and children, internal displacements and destruction of property (villages, houses and farmlands), damage to local economies, and political and social tensions. However, not all chiefs are oblivious to the harm they have caused to themselves and their communities. Some of them recognised the fact that they have abused the customs, practices and traditions of their ancestors. They would even blame themselves for inflicting suffering and destruction on their own people through the chieftaincy-related conflicts (interview: chiefs – Doryumu, Kokrobitey, Fotobi and Abaase, Accra, July 2021). Because these communal conflicts have been inextricably linked with chieftaincy issues, a respondent described chiefs as “perpetrators of conflicts against their own people/subjects” (interview: lecturer in African studies, Accra, February 2020). Therefore, the exclusion of chiefs from the DAs may be seen as a deliberate attempt to prevent a situation where they could create communal conflicts and then seek to resolve them in the DAs (interview: KAS and FES officers; MP, Tolon, Accra, July 2021). Hence a respondent believes that: “Chiefs’ alienation from the DAs is geared towards creating an environment that would enhance the ability of the latter to promote peace and maintenance of law and order in the communities” (interview: KAS programme officer, Accra, July 2021).

In a similar vein, the exclusion of chiefs from the DAs has also been attributed to their role in land disputes by observers beyond the scope of this study (for instance, see Ghana News Agency 2021). While the customary laws of Ghana bestow upon chiefs the control of all communal/stool lands, they are expected to manage them for the benefit of the present and posterity (interview: farmers – Vokpo, Kunkpano, Aveme, Torda, Tali and Sambu, April 2019). Yet, over the years, due to increased pressures on lands because of population growth, migration, urbanisation and estate developments, chiefs in certain parts of the country have engaged in illegal and multiple sales of lands (interview: businesswoman, building contractor, Mason, Kokrobitey and Zandor, June 2019). Consequently, a respondent blamed chiefs for “the growing land litigations and frauds as well as the land-guard menace that has involved the mobilisation of thugs to intimidate and even kill opposing litigants over land ownership” (interview: estate developer, Kokrobitey, June 2019; see also Udry and Aryeetey 2010). This situation has led to a wider problem such as poor management of stool lands, corruption and general insecurity over land acquisitions (interview: estate developer, masons, businesswoman, Doryumu and Kokrobitey, June 2019). Therefore, according to a respondent, “the absence of chiefs in the DAs is to enable the latter to deal with land disputes in the communities without fear or favour” (interview: AM, Doryumu, June 2019).

Why should chiefs be involved in decentralised local governance?

Nevertheless, even though some of chiefs’ activities have not always upheld peace and order in communities (Arhin 2006; Ayee 2008; Asamoah 2012), some pro-chieftaincy advocates believe that involving chiefs in local government is overdue (interview: lecturer in political science; CDD and KAS programme officers, Accra, February 2020). The chiefs’ position about their participation in local governance has centred on their conviction that the chieftaincy institution is an enduring one with a track record of performance before and during colonial rule as well as the immediate post-independence era and, therefore, have a lot to offer in the DAs (interview: chiefs – Hwidiem, Apoli, Odumase, Asuso, Asamanya, Fotobi and Abaase, December 2019). Similarly, some key informants would like chieftaincy to be integrated into the DAs because of the understanding that despite its informal nature, the sacred institution has shared habits and practices of the people, and the fact that chiefs have demonstrated capacity to promote their wellbeing (interview: official of CS, lecturers in African studies and political science, Accra, December 2019). In the opinion of one of them, “the extent to which the DAs have been able to effectively execute their responsibilities largely depended on the support they received from chiefs” (interview: AM, Asamanya, Accra, December 2019). For instance, in many typical rural communities where the use of modern communication systems is a challenge,12 chiefs’ platforms have remained the channels used to mobilise the people to implement the DAs’ development programmes (interview: DCEs – Birim South, Mion, Tolon, Assin South and Adaklu, October 2019). In these areas, chiefs caused the local gong-gong to be beaten to rally the people to carry out the community self-help projects that had been initiated by the AMs. In the same vein, some local government officials acknowledged the fact that the smooth execution of DAs’ development projects had been enhanced by the willingness of the local chiefs to release stool lands for the construction of markets, public toilets and school buildings, among others (interview, DCEs and AMs – Birim South, Ashanti Akim North, Mion, Tolon, Adaklu, October 2019).

Indeed, cooperation between traditional authorities and local government has been recognised as an important precondition for decentralisation success in Africa. Kelsall (2008) and Myers and Fridy (2017) have argued that a functioning local institution such as chieftaincy that operates in the daily lives of the citizens should be recreated/reinvented to promote the work of formal institutions such as DAs. This collaborative local development argument has been echoed by some respondents. These respondents think that assigning chiefs a formal role in the local governance process would enhance the legitimacy of the DAs for accelerated rural development in the country (interview: officials of Chieftaincy Secretariat; MPs for Assin South, Tolon, Adaklu and North Dayi, Accra, June 2019).

Furthermore, while acknowledging that chieftaincy has been tarnished by many anti-development activities, some key informants also noted that chiefs have been able to positively affect the lives of people in rural communities because of long-standing, intimate relationships. In the opinion of a respondent, “since time immemorial, chieftaincy is the legitimate local institution that has given meaning to the identity of the African people” (interview: lecturer in African studies, Accra, February 2020). Also, there is a general view that in rural communities, chiefs are very close to and familiar with the people. The people also know the ways, times and place to see their chiefs (interview: farmers, teachers, lay-preacher, hairdresser – Hwidiem, Adiembra, Akuase, Odumase, Asuso, April 2019). This familiarity has given chiefs an advantage over the elected AMs: regular interactions between chiefs and the local people have enabled them to know and understand the needs of their subjects and, unlike the AMs (some of whom are only temporary residents in their electorates), chiefs have made themselves available to the people for regular consultations. Similarly, many respondents believed that chiefs have listened to them on a daily basis to address their particularistic concerns (interviews: officials of CS and LGS, Accra, December 2019).

In some cases where the DAs could not readily fix particular community problems, chiefs have been able to mobilise the people to solve them. Whenever the people had problems, the chiefs were the first and immediate points of call (Fridy and Myers 2019). This is because the chiefs are approachable: they open their courts to the people to table their individual concerns and deliver quick responses to them. Many respondents feel the chiefs’ interventions bring emotional and psychological relief to the people, albeit temporary (interview: farmers – Hwidiem, Kotwea, Asamanya, Adiembra, Akuase, Odumase, Asuso, April 2019). Hence some respondents believe that governmental action to formalise chiefs’ communal activities rather than the bureaucratic and representation functions of the elected DA members would be to their collective benefit/interest (interview: farmers – Ziofe, Vokpo, Torda, Aveme, Kasuliyili Tali, Sambu, Kunkpano, September 2019).

Conclusion

Despite its inherent challenges, decentralisation is widely regarded as a necessary condition for the success of developing countries’ governance and development agendas. Based on the implicit benefits, Ghana began to implement democratic decentralisation in the early 1990s. The DAs were created as the institutional mechanism not only to promote development but also to enable individuals and other actors to participate in decision-making processes at the local level. Through the DAs, the grassroots have elected their own representatives to provide leadership in their communities. However, some critics of Ghana’s decentralisation policy (Arhin 2006; Ayee 2008; Antwi-Bosiako 2010; Adjei et al. 2017; Fridy and Myers 2019) have contended that the country’s decentralised local governance must not proceed solely based on the Western ideals of democratic election that may sideline actors who largely derive their authority from custom, and traditional norms and practices. This reflects a realisation that it is impossible to attain the goals of sustainable development of human societies without creating enduring partnerships that draw traditional leadership (chiefs) into local government’s orbit (Arthur and Nsiah 2011). Also, integrating traditional institutions “that work with the grain” – rather than suppressing them through Western-style practices and standards of local governance – is crucial for effective local development (Booth and Cammack 2013, p. 99).

However, the present study did find that certain dimensions of chieftaincy are at odds with democratic decentralisation, notably the selection of chiefs based on customary practices which conflicts with the requirement to stand for election to DAs. Also, the many and protracted communal conflicts and land sales controversies, litigation and corruption that have destroyed lives and properties, and undermined local development, community unity and peace, have their roots in chieftaincy power struggles. Nevertheless, many chiefs have well-established intimate relationships and familiarity with local people that have enabled them to provide continuing support to rural communities.

On balance, given that chieftaincy is entrenched in the socio-cultural fabric of rural communities, and that continuing cooperation from chiefs would aid the work of the DAs, the findings of this study support calls for a re-examination of the current local government system to include chiefs as one of the important local actors (Logan 2011; Adjei et al. 2017; Fridy and Myers 2019). The author suggests that there is a need for flexibility in institution development based on how people experience and interact with those institutions (Berk and Galvan 2009; Fridy and Myers 2019), rather than a rigid approach that has pushed chiefs away from local government. Chieftaincy needs to be harnessed in cooperation with DAs to facilitate the attainment of the objectives of decentralisation – in contrast to the current approach that promotes only the DAs, even though on their own they lack the required capacity to handle developmental challenges. While the debate about whether chieftaincy is ready to be integrated into modern local government, or how to reinvent it for relevance in today’s decentralised local governance, is a complex and long-standing one, this research has found popular perspectives to be that inclusivity is the way forward for effective decentralisation in Ghana.

The author proposes that promoting inclusivity, cooperation and responsibility-sharing could be pursued in three ways in any future local government/decentralisation reform. The first option is that chiefs could be made legitimate members of the DAs by reserving the 30% of seats currently appointed by the president for traditional authorities (chiefs and their elders). Each traditional area would nominate chiefs to fill the vacancies. This option is likely to receive the overwhelming support of the principal stakeholders, because there is a precedent for it: when the council system replaced the native authorities from the 1940s, the colonial government and subsequent Ghanaian governments allocated one-third of council seats to chiefs – and this tradition continued until PNDC Decree 4 abolished it (Ayee 1994).

In the same spirit of inclusivity, those nominated should include queen-mothers. As the principal person responsible for nominating a royal as chief, especially in Akan society, the queen-mother is highly revered as the legitimate mobiliser of women around salient community issues. Therefore, as the moral, spiritual and social guardian of women, the inclusion of queen-mothers could ensure that concerns such as cruel widowhood rites, female circumcision, child marriages, and other forms of spousal abuse that are often perpetrated against women in rural areas receive due attention by the DAs.

A second option would be for the paramount chief of the traditional area or his representative to be appointed as the ceremonial head of the DA with the right of address. This option resonates with the view of the committee of experts that drafted the 1992 Constitution (Republic of Ghana 1991).

A third possibility is that the functions of DAs could be divided into two, with representation functions such as policy-making remaining with elected members but those relating to grassroots mobilisation, enforcement of by-laws and supervision of the implementation of development projects being ceded to chiefs. On several platforms, chiefs have complained that they are totally neglected in the local development process and the findings of this study corroborate earlier research on the need to make them relevant actors (Yankson 2000; Arhin 2006). This option would capitalise on people’s emotional and psychological attachments to chieftaincy, and their belief that chiefs are effective agents of local development whose role has stood the test of time (Republic of Ghana 1991; Ayee 1994; Seini 2006).

Given the evident eagerness of rural people to see their chiefs resume their role in community development, their inclusion through one or more of these three avenues would bolster their image as leaders in local development and bring back the traditional honour accorded to the chieftaincy institution in Ghanaian society.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

Adjei, Osei-Wusu, P., Busia, A.K. and Bob-Milliar, G.M. (2017) Democratic decentralization and disempowerment of traditional authorities under Ghana’s local governance and development system: a spatio-temporal review. Journal of Political Power, 10 (3), 303–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/2158379X.2017.1382170

Antwi-Boasiako, K.B. (2010) Public administration: local government and decentralization in Ghana. Journal of African Studies and Development, 2 (7), 166–175.

Arhin, N.B. (2006) Chieftaincy: an overview. In: Odotei, I. and Awedoba, A. (eds.) Chieftaincy in Ghana: culture, governance and development, (pp. 5–12). Accra: Sub-Saharan Publishers.

Arthur, J.L. and Nsiah, M.K. (2011) Contemporary approaches to sustainable development: exploring critical innovations in traditional leadership in Ghana. African Journal of Political Science and International Relations, 5 (5), 245–253.

Asamoah, K. (2012) A qualitative study of chieftaincy and local government in Ghana. Journal of African Studies and Development, 4 (3), 90–95. https://doi.org/10.5897/JASD11.089

Asante, R. and Debrah, E. (2019) The pitfalls and prospects of decentralization in Ghana: implications for the national mobilization for development agenda: In: Ayee, J.R.A (ed.) Politics, governance and development in Ghana, (pp. 235–259). London: Lexington Books.

Assimeng, M. (1996) Traditional leaders’ capability and disposition for democracy: the example of Ghana. Paper presented during an International Conference on Traditional and Contemporary Forms of Local Participation and Self-Government in Africa, Organised by Konrad Adenauer Foundation in Nairobi, Kenya, 9–12 October.

Awedoba, A.K. (2006) Modes of succession in the Upper East Region of Ghana. In: Odotei, I. and Awedoba, A. (eds.) Chieftaincy in Ghana: culture, governance and development, (pp. 409–428). Accra: Sub-Saharan Publishers.

Ayee, J.R.A. (1994) An anatomy of public policy implementation. Aldershot: Avebury.

Ayee, J.R.A. (2008) Decentralization and governance in Ghana. Regional Development Dialogue, 29 (2), 34–52.

Berk, G. and Galvan, D. (2009) How people experience and change institutions: a field guide to creative syncretism. Theory and Society, 38 (6), 543–580. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-009-9095-3

Booth, D. and Cammack, D. (2013) Governance for development in Africa: solving collective action problems. London: Zed Books. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350220522

Braathen, E. (2008) Decentralization and poverty reduction: a review of the linkages in Tanzania and the international literature. Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD). Discussion Report Number 22.

Busia, K.A. (1968) The position of the chief in modern political system of Ashanti. London: Oxford University Press.

Chazan, N. (1983) An anatomy of Ghanaian politics: managing political recession, 1969-1982. Boulder: Westview Press.

Cheema, G.S. and Rondinelli, D.A. (2007) From government decentralization to decentralized governance. In: Cheema, G.S. and Rondinelli, D.A (eds.) Decentralizing governance: emerging concepts and practices, (pp.1–20). Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Conyers, D. (2007) Decentralisation and service delivery: lessons from Sub-Saharan Africa. Institute of Development Studies (IDS) Bulletin, 38 (1), 18–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.2007.tb00334.x

Crawford, G. (2004) Democratic decentralization in Ghana: issues and prospects. Working Paper 9. Leeds: School of Politics and International Studies, University of Leeds.

Crook, R. and Sverrisson, I. (2001) Decentralization and poverty alleviation in developing countries: a comparative analysis, or is West Bengal unique? Brighton: Institute of Development Studies.

Debrah, E. (2014) The politics of decentralization in Ghana’s fourth republic. African Studies Review, 57, 49–69. https://doi.org/10.1017/asr.2014.5

Debrah, E. (2016) Decentralization, district chief executives, and district assemblies in Ghana’s fourth republic. Politics & Policy, 44 (1), 135–164. https://doi.org/10.1111/polp.12146

De Mello, L., Luiz, R.J. and Barenstein, M. (2001) Fiscal decentralization and governance: a cross country analysis. World Development, 28 (2), 365–80. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.879574

Dickovick, T.J. (2014) Foreign aid and decentralization: limitations on impact in autonomy and responsiveness. Public Administration and Development, 34 (3), 194–206. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.1691

Dickovick, T.J. and Riedl, B.R. (2014) African decentralization in comparative perspective democracy. In: Dickovick, T. and Wunsch, J. (eds.) Decentralization in Africa: the paradox of state strength, (pp. 249–276). London: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Dillinger, W. (1994) Decentralisation and its implications for urban service delivery, urban management and municipal finance. World Bank Discussion Paper 16. Washington, DC: World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/0-8213-2792-5

Drah, F.K. (1987) Aspects of the Akan state system: precolonial and colonial. In: Ninsin, K.A and Drah, F.K. (eds.) The search for democracy in Ghana: a case study of political instability in Africa, (pp. 33–54). Accra: Asempa Publishers,.

Englebert, P. and Kasongo, M.E. (2016) Misguided and misdiagnosed: the failure of decentralization reforms in the DR Congo. African Studies Review, 59 (1), 5–32. https://doi.org/10.1017/asr.2016.5

Fisman, R. and Gatti, R. (2002) Decentralization and corruption: evidence across countries. Journal of Public Economics, 83 (3), 325-345, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-2727(00)00158-4

Fjeldstad, O.-H. (2004) Decentralisation and corruption: a review of the literature. CMI Working Papers, 10, 1–12.

Fridy, S.K. and Myers, W.M. (2019) Challenges to decentralisation in Ghana: where do citizens seek assistance? Commonwealth & Comparative Politics, 57 (1), 71–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/14662043.2018.1514217

Ghana News Agency. (2021) Deputy Minister warns authorities against multiple land sales. General News of Saturday, 31 July.

Gold Coast. (1944) Native authority ordinance of 1944. Accra: Government of the Cold Coast.

Green, E. (2015) Decentralization and development in contemporary Uganda. Regional & Federal Studies, 25 (5), 491–508. https://doi.org/10.1080/13597566.2015.1114925

Grindle, M.S. (2007) Going local: decentralization, democratization, and the promise of good governance. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Guzmán, S.G. (2015) Substantive-rational authority: the missing fourth pure type in Weber’s typology of legitimate domination. Journal of Classical Sociology, 15, 73–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468795X14531695

Hadiz, V.R. (2004) Decentralization and democracy in Indonesia: a critique of neo‐institutionalist perspectives. Development and Change, 35 (4), 697–718. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0012-155X.2004.00376.x

Hutchful, E. (2002) The fall and the rise of the state in Ghana. In: Samatar, A.I. and Samatar, A.I. (eds.) The African state: reconsiderations, (pp.101–129). Portsmouth: Heinemann.

Kelsall, T. (2008) Going with the grain in African development? Development Policy Review, 26 (6), 627–655. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7679.2008.00427.x

Lavrakas, J.P. (2008) Encyclopaedia of survey research methods. London: Sage https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412963947

Logan, C. (2011) The roots of resilience: exploring popular support for African traditional authorities. Afrobarometer Working Paper, 128, 1–25.

Manor, J. (1999) The political economy of democratic decentralization. Washington DC: The World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/0-8213-4470-6

Mawhood, P. (ed.) (1993). Local government in the third world: experience of decentralization in tropical Africa. Johannesburg: Africa Institute of South Africa.

Myers, W.M. and Fridy, K.S. (2017) Formal versus traditional institutions: evidence from Ghana. Democratization, 24 (2), 367–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2016.1184247

Rathbone, R. (2000) Nkrumah and the chiefs: the politics of chieftaincy in Ghana 1951–60. Oxford: James Currey.

Ray, D.I. (2003) Rural local governance and traditional leadership in Africa and the Afro-Caribbean: policy and research implications from Africa to the Americas and Australia, In: Ray, D.I. and Reddy, P.S. (eds.) Grassroots governance? Chiefs in Africa and the Afro-Caribbean, (pp. 1–30). Calgary: University of Calgary Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv6gqrhd.5

Republic of Ghana. (1991) Report of the committee of experts (Constitution) on proposals for a draft constitution of Ghana. Tema: Ghana Publishing Corporation.

Republic of Ghana. (1992) Constitution of Ghana. Tema: Ghana Publishing Corporation.

Republic of Ghana. (1993) Local Government Act 462. Tema: Ghana Publishing Corporation

Republic of Ghana. (2010) The legislative instrument 1967: the local government (urban, zonal and town councils and unit committees) established. Accra: Assembly Press.

Republic of Ghana. (2016) Local Government Act 963. Accra: Assembly Press.

Ribot, J.C. (2002) African decentralization: local actors, powers and accountability, democracy, governance and human rights. Working Paper No.8. Geneva: UNRISD and IDRC.

Sasaoka, Y. (2007) Decentralization and conflict. Tokyo: Japan International Cooperation Agency.

Seini, W.A. (2006) The role of traditional authorities in rural development. In: Odotei, I. and Awedoba, A. (eds.) Chieftaincy in Ghana: culture, governance and development, (pp. 547–565). Accra: Sub-Saharan Publishers.

Smith, B. (1985) Decentralisation: the territorial dimension of the state. London: George, Allen and Unwin.

Smoke, P. (2015). Rethinking decentralization: assessing challenges to a popular public sector reform. Public Administration and Development, 35 (2), 97–112. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.1703

Smoke, P. and Matthew, W. (2011) Donor program harmonization, aid effectiveness and decentralized governance. Local Governance & Decentralization. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265424328_Donor_Program_Harmonization_Aid_Effectiveness_and_Decentralized_Governance_January_2011

Taabazuing, J. (2010) Towards effective participation of chiefs in Ghana’s decentralization process: the case of Wenchi district. An unpublished PhD Thesis submitted to the University of South Africa.

Tonah, S. (2012) The politicisation of a chieftaincy conflict: the case of Dagbon, Northern Ghana. Nordic Journal of African Studies, 21 (1), 1–20.

Turner, M. and Hulme, D. (1997) Governance, administration and development: making the state work. London: Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-25675-4

Udry, C.R. and Aryeetey, E. (2010) Creating property rights: land banks in Ghana. American Economic Review, 100 (2), 130–34. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.100.2.130

Williams, J.M. (2010) Chieftaincy, the state and democracy: political legitimacy in post-apartheid South Africa. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

World Bank. (2008) Decentralization and local democracy in the world. First global report by United Cities and Local Governments. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Wunsch, J. (2001) Decentralization and local governance and ‘recentralization’ in Africa. Public Administration and Development, 21, 277–288. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.185

Wunsch, J. (2014) Decentralization: theoretical, conceptual, and analytical issues. In: Dickovick, T. and Wunsch, J. (eds.) Decentralization in Africa: the paradox of state strength, (pp. 1–22). London: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Yankson, P.W.K. (2000) Decentralization and traditional authorities in Ghana. In: Thomi, W., Yankson, P.W.K. and Zanu, S.Y. (eds.) A decade of decentralization in Ghana: retrospect and prospects. Accra: EPAD Research Project/Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development.

1 A system of administration where authority is exercised based on formal or codified rules or laws.

2 The initial target of 300 was not achieved because about 20 chiefs could not participate in the interviews, reducing the actual total to 280 respondents. The researcher and his assistant visited each district at least twice throughout the period of data collection. The researcher also engaged in several pre-interview contacts with officers of DAs and other individuals in order to obtain the consent of the chiefs to participate in the study. Following all traditional protocols paved the way for smooth and cordial interactions with the chiefs and their elders.

3 Section 5(2) of Act 936 makes the MP of the district an ex-officio member of the DA. Normally, a rural DA would have one MP (Republic of Ghana 2016; Local Government Act, 936).

4 The majority of these respondents were farmers, drivers, artisans, teachers, small traders, business persons and members of local professional associations.

5 Except for a few occasions, the chiefs gathered their elders for interaction with the researcher during the arranged interview, turning the sessions into more-or-less group discussions.

6 This finding is consistent with the account of Yankson (2000).

7 This has the shape of a metal bell; usually a stick is used to make a loud sound to draw attention.

8 Membership of the DISEC comprises the DCE as chairperson, district police commander, crime officer, customs officer, national investigation bureau officer, immigration service officer, fire service officer, National Disaster Management Organisation (NADMO) officer, and two persons nominated by the DCE in consultation with the national security coordinator and the district coordinating director as secretary.

9 Both Acts 462 and 963 mandate the EC as the policy chamber of the DA. Its members consist of the DCE, chairpersons of the statutory sub-committees and two AMs elected from among their peers (Republic of Ghana 2016, p. 26).

10 Section 23 of Act 963 establishes five sub-committees of the EC (Republic of Ghana 2016, p. 28).

11 A relative of the chief – mother, sister or niece – responsible for nominating a royal male to be elected as chief. While traditional governance guarantees the position of queen-mothers, they are never elevated above chiefs. Customarily, chiefs have served as the representative of the people in all important activities whether national or local; and since the inception of the Fourth Republic all paramount chiefs have been males even though in some cases queen-mothers may be granted observer status at such events.

12 Despite the reduction in the use of the gong-gong as a mode of rallying the local people, in many rural communities AMs have had to rely extensively on it to mobilise the electorate because of lack of access to social media and high levels of illiteracy.