Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance

Issue 25

December 2021

RESEARCH AND EVALUATION (PEER REVIEWED)

Participatory Monitoring and Evaluation in Local Government: A Case Study of Lambussie District, Ghana

Bernard Afiik Akanpabadai Akanbang

Faculty of Planning and Land Management, SD Dombo University of Business and Integrated Development Studies, Box UPW 3, Wa, Ghana, bakanbang@uds.edu.gh

Anass Ibn Abdallah

Nanton District Assembly, Northern Region, Ghana, ibnanass.gh@gmail.com

Corresponding author: Bernard Afiik Akanpabadai Akanbang, Faculty of Planning and Land Management, SD Dombo University of Business and Integrated Development Studies, Box UPW 3, Wa, Ghana, bakanbang@uds.edu.gh

DOI: http://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi25.8037

Article History: Received 02/03/20; Accepted 07/11/21; Published 30/12/21

Citation: Akanbang, B. A. A., Abdallah, A. I. 2021. Participatory Monitoring and Evaluation in Local Government: A Case Study of Lambussie District, Ghana. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, 25, 40-55. http://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi25.8037

© 2021 by the author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Abstract

Ghana has pursued decentralisation since 1988, but its implementation continues to face challenges. Participatory monitoring and evaluation (PM&E) is one of the tools that can help local governments to be more effective in the planning and management of development projects. However, the issues involved in implementing PM&E in rural local governments operating within a rapidly changing sociocultural and political environment have not been sufficiently explored. To fill this gap in knowledge, this paper draws on project and policy documents and primary data on the application of PM&E in District Assemblies’ Common Fund projects implemented between 2013 and 2017 in Ghana’s Lambussie District. Six key informant interviews were held with district- and regional-level stakeholders, and eight focus group discussions were undertaken at the community level. The research found that inadequate provision for operationalising PM&E at the local level, and lack of accountability and feedback mechanisms, resulted in a tokenistic approach to PM&E. The authors suggest that research and advocacy on mechanisms for holding district authorities accountable is vital to the success of future PM&E initiatives at local government level.

Keywords

Participatory Monitoring and Evaluation; District Assembly Common Fund; Decentralisation; Local Government

Introduction and literature review

Participatory monitoring and evaluation (PM&E) has gained currency in decentralised local governance in the developing world. The driving forces behind its adoption are its potential to promote community empowerment, learning, accountability and effectiveness in the implementation of development interventions (Vernooy 2003; Akin et al. 2005; Jütting et al. 2005; Woodhill 2005; Göergens and Kusek 2010; Akanbang 2012; Porter and Goldman 2013; Kananura et al. 2017).

PM&E, as conceived by the World Bank (2010) and viewed in this study, is a process through which stakeholders at various levels take part in monitoring and/or evaluating a specific policy, programme or project, and share power and responsibilities over the substance, the procedure and the after-effects of the monitoring and evaluation action as well as any remedial activities required. PM&E is largely based on two perspectives – participation as a means (process of participation) and participation as an end (effect or benefits of participation) (Vernooy 2005). A review of the literature shows that PM&E builds the capacity of local people to analyse, reflect and take action (Estrella et al. 2000; Bartecchi 2016). It strives to be an internal learning process for project implementers and community-level stakeholders; it is flexible and adaptive to local contexts; it encourages stakeholder participation beyond data gathering; and it strengthens people’s capacities to take action and promote change (Estrella et al. 2000; Matsiliza 2012; Mascia et al. 2014). It is also adaptable, and quintessentially and methodologically eclectic (Rossman 2015). Nevertheless, for its effective application PM&E needs to be grounded in key standards including preferential involvement of the weak and vulnerable; empowerment and commitment of all stakeholders; open dialogue; and transparency and accountability in the use of resources (World Bank 2009, cited in Muriungi 2015, p. 61; Bartecchi 2016).

The regulatory and institutional framework within which PM&E takes place is one of the key factors affecting its implementation (Oloo 2011; Musomba et al. 2013), and building capacity at the policy, organisational and community level is an integral ingredient for success. Weak institutional capacity and lack of coordination among agencies pose significant challenges (Uitto 2006; Tengan and Aigbavboa 2016). At the same time, PM&E must respond to significant policy changes at global, national and local level that have occurred – notably, in the 21st century, in response to the Millennium and Sustainable Development Goals (MDGs and SDGs). These changes have influenced citizens’ access to social services and heightened political consciousness across the developing world. However, the effect of these changes on citizens’ participation in the monitoring and evaluation of programmes at the local level has not been given due attention. This paper aims to kick-start such a discourse. Thus, the research question explored in this study is: What emerging constraints affect the implementation of PM&E in decentralised rural local governments, within a rapidly changing socio-cultural and political environment?

The study explores stakeholders’ experiences of PM&E with a view to enriching the quality of knowledge and debate about how best to mainstream PM&E in local governance as a catalyst for poverty reduction. As underscored by Harnar and Preskill (2007), there is unanimity on the necessity for stakeholder participation in project and programme evaluation, but how best to implement PM&E in different settings is still unclear especially those with a weak evaluation culture and financial resource base (Estrella et al. 2000; Miller and Campbell 2006). Filling this knowledge gap is very important because, as acknowledged by Boissiere et al. (2014), Garcia and Lescuyer (2008) and Villasenor et al. (2016), not all PM&E activities are effective in enhancing the performance of programmes, or lead to capacity development at the community level.

The focus of this paper is on finding answers to emerging challenges facing effective citizen participation in monitoring and evaluation at the local level. Some research on PM&E to date has explored the benefits of PM&E for local governance (Ahwoi 2008; Naidoo 2011; Sulemana et al. 2018). More recently Akanbang (2021) examined the implications of integrated decentralised monitoring of water and sanitation services at the local level, while Akanbang and Bekyieriya (2020) examined benefits and constraining factors affecting decentralised monitoring of development projects. However, these studies did not closely examine how the PM&E processes actually worked at the grassroots level.

Study context

Ghana has been implementing a modern decentralised system of governance since 1988. Article 82, Section 1 of the Local Governance Act 2016 (Act 936) establishes three tiers of local government – metropolitan, municipal and district assemblies (MMDAs). As part of the central government’s efforts at strengthening fiscal decentralisation, it has been committing at least 7.5% of total annual revenue to an account known as the District Assemblies’ Common Fund (DACF). This is shared among all the MMDAs in the country to fund their development functions (Government of Ghana 2016). In recognition of the importance of evaluation of those activities, the National Development Planning Commission (NDPC), the central planning agency in Ghana, adopted PM&E in the early 2000s as the approach for monitoring and evaluation to be followed by all MMDAs (NDPC 2014).

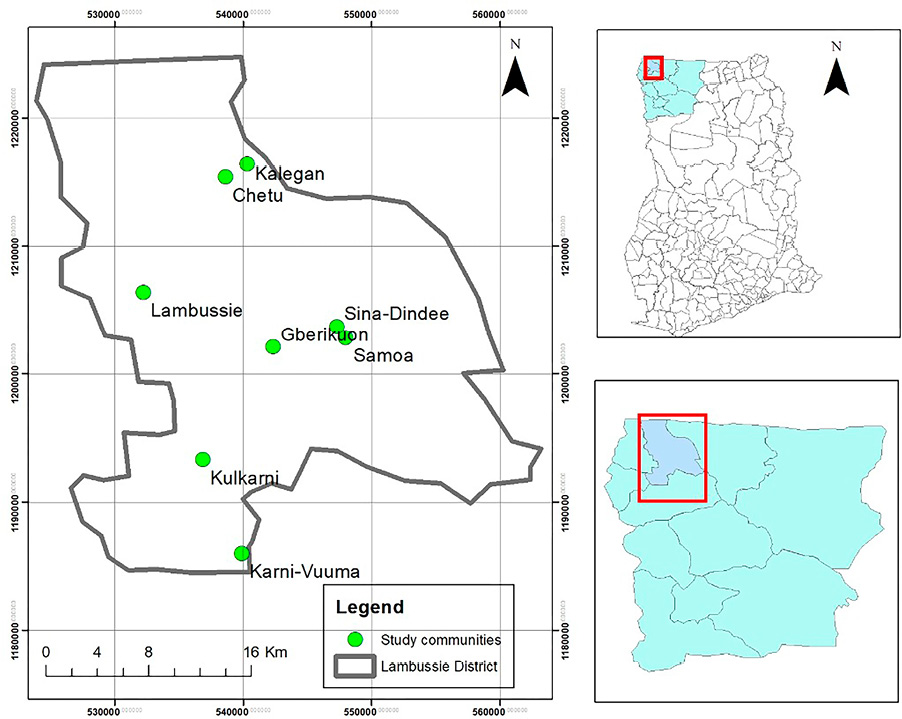

Lambussie District is one of 11 districts in the Upper West Region of Ghana, and was created in 2007. It has a total land area of 811.9 km2 and shares a boundary with the Republic of Burkina Faso (Lambussie District Assembly 2014). Figure 1 shows the location of the District in its regional and national context. It has an estimated population of 51,654 and is among the three most recent districts to be created in what is the poorest region of Ghana (Ghana Statistical Service 2014). The District is strategically located because of its proximity to Burkina Faso, which can be leveraged to enhance cross-border trade, promote cultural exchange and propel Lambussie’s development. It has an agrarian economy with the majority of its populace engaged in subsistence crop and animal husbandry, weaving, shea butter extraction and trading activities. It is one of the most deprived districts in the region and thus provides a fertile ground for exploring the application of PM&E in a resource-constrained local government context.

Figure 1. Lambussie District in regional and nationl context

Source: Authors’ construct, 2021

The general assembly is the highest decision-making body of an MMDA, made up of elected representatives and appointed members, with deliberative, legislative and executive functions. Lambussie District has 36 members – 27 elected members and 9 government appointees. Within the district there are four area councils: Lambussie, Samoa, Karni and Hamile (Lambussie District Assembly 2014). Area councils are the bridge between the district and local communities. They work with the district planning coordinating unit (DPCU) of the assembly to coordinate and harmonise planning and plans of communities under their jurisdiction. There are two groups of technocrats to help in the efficient running and provision of services at the local level: those who work in the departments of the assembly (eg agriculture, health, education etc), and those working in the district administration (DPCU, budget unit, administrative unit, finance unit, internal audit and human resources unit). The district administration is the secretariat of the assembly and coordinates the work of its line departments, which also function as decentralised arms of central government. Departments report to the district chief executive (DCE, political head) through the district coordinating director (DCD), who is the technical head of the assembly.

In Ghana, MMDAs are planning authorities and are responsible for the delivery of services geared towards enhancing the quality of life of their inhabitants (Government of Ghana 2016). In the pursuit of their planning functions, MMDAs are obliged by Article 240 (2) (e) of the 1992 Constitution to involve their citizens in the planning, implementation and management of services. The Article states that “to ensure the accountability of local government authorities, people in particular local government areas shall, as far as practicable, be afforded the opportunity to participate effectively in their governance”.

The planning process to meet developmental needs is systematic and includes multiple stages: constitution of a district medium-term development plan (DMTDP) team; performance review of the previous plan; data collection, collation and analysis with stakeholders including traditional authorities, communities, sub-structures and decentralised departments; public hearings to present the current situation and ascertain development priorities; preparation of a draft plan consisting of policies, programmes and projects; a second round of public hearings to review development proposals and strategies; submission of the draft plan to both the regional coordinating council (RCC, an arm of central government that oversees several districts and aims to harmonise plans and service delivery in accordance with national policies and priorities) and to the NDPC for vetting; review of the draft plan based on their comments; approval of the plan by the district assembly; and submission of copies of approved plans to the RCC and NDPC (NDPC 2014).

The next step towards implementation of the DMTDP is the extraction of annual action plans, a process intended to be carried out with active community involvement. At the community level, there are elected members who form a unit committee alongside their local assembly member. Implementation of selected projects is then undertaken by the responsible district department. In most cases, especially infrastructure projects, work is contracted out to a private service provider or contractor. The responsible department monitors and supervises implementation in collaboration with the assembly administration and community-level stakeholders (comprising the above-mentioned unit committees and assembly members).

These processes apply to all projects including those financed from the DACF.

Methodology

A case-study design was adopted for this research. The rationale was to enable the authors to gain an ‘insider’ perspective and an in-depth, comprehensive and holistic understanding of the topic by focusing on a relatively small number of respondents and using multiple data sources (Flyvbjerg 2011; Creswell 2014; Yin 2014; Harrison et al. 2017, all cited in Akanbang 2021). Fieldwork was conducted between January and June 2018, while the timeframe of the case study was 2013 to 2017. The choice of that period was to cover all completed DACF civil works projects rolled out for implementation in the 2013–17 Lambussie District Medium-Term Development Plan, as well as to ensure that most of the key actors were still in post and that recall of their experiences and perspectives on the subject was fresh. Table 1 shows the area councils, communities and projects from which the results for this paper were derived.

Key informants who were interviewed individually comprised the regional economic planning officer, the district planning officer, the district works engineer, the district director of health, the district director of education, and the chairperson of the development planning sub-committee. Other targeted respondents – assembly members, traditional chiefs, chairpersons and secretaries of the unit committees – were participants in focus group discussions (FGDs). All these respondents played key roles in the PM&E process at the community level. Participants for the FGDs were drawn from two communities in each of the four area councils of the district, where civil works projects had been implemented during the study period. The choice of civil works projects was because they have strong monitoring requirements, and the consequences of effective or ineffective monitoring can be easily observed. Each FGD involved eight people (Morgan and Krueger 1997), namely the assembly member, chairman and secretary of the unit committee, one person living with a disability, two local resident women, a local resident man, and one head of a local beneficiary institution.

Primary data from interviews, FGDs and observation focused on the practical application of PM&E in a developing country setting. The FGDs explored issues around community involvement in the monitoring and evaluation of projects; the roles community members played; factors that affected their effective participation; and ways of enhancing local stakeholder involvement. The discussions were audio-recorded with the permission of respondents and then translated into English before transcribing.

The six in-depth key informant interviews explored mechanisms for involving stakeholders in the monitoring and evaluation of projects; factors that affect the implementation of PM&E; and the effectiveness of PM&E at the local level of governance. All the interviews were recorded with the permission of respondents, and thereafter transcribed.

Secondary data from both project reports and monitoring and evaluation reports was used in the initial stages of the study to refine the research design, methods and interview questions. In the latter part of the study, the secondary data also enabled triangulation and interpretation of results.

Primary data was organised into themes in line with the key issues explored in the study. The detailed process of analysis included compiling, disassembling, re-assembling, interpreting and concluding (Castleberry and Nolen 2018). The secondary data was subjected to content analysis and integrated into the primary data. This involved expanding, collapsing, merging and creating themes that best represented initial interpretations of meaning (Miles and Huberman 1994; Ibrahim et al. 2020). Quotations from respondents were then incorporated into the results to illustrate key points of policy relevance and those which required critical analytical attention.

Background characteristics of study participants

Only two out of 14 ‘senior’ informants (six key informants at the district and eight heads of community-level institutions who participated in FGDs) were female. The implication of this observation is that female perspectives on monitoring and evaluation will likely not be fully reflected. It also raises doubt as to the level of inclusiveness of the district’s PM&E process. The ‘senior’ female informants were the district director of health and the head of the social welfare and community development department. However, there was greater female participation in FGDs. Out of the total community-level participants of 56 (64 less the 8 heads of institutitons), there were 22 women (39.3%).

The level of education of participants has been identified as a key requirement for the effective application of PM&E to development initiatives (Cracknell 2000). In this study, all respondents at the district level and head of institutions at the community level had attained a minimum of degree-level education in a relevant field. Also, the actors involved in PM&E at the district level had an average of five years’ working experience in monitoring and evaluation.

Educational attainment of community participants was as follows: 61% tertiary, 15.6% secondary, 10.9% basic and 12.5% no formal education. This relatively high level overall was the result of purposive sampling in which a greater number of respondents were staff of service delivery institutions located at the community level. The underlying requirement for an educated community to support effective implementation of PM&E remains a challenge, given typically low levels of educational attainment in many rural communities. To ensure inclusivness in PM&E, investments in basic education and adult education and conscientisation through radio programmes are still fundamental in many resource constraint settings.

Results and discussion

Table 2 shows the two themes and the associated issues that emerged from the analysis of data. This section presents and discusses observations under each of the themes.

| Area of operationalisation | Observations |

|---|---|

| Processes for operationalisation of PM&E at district and community levels |

|

| Distribution of power |

|

Processes for putting into effect PM&E

Under this theme, four main challenges were cited by participants: inadequate provision for community involvement; inadequate guidelines on how to operationalise PM&E at district level; a low level of involvement by stakeholders; and weak transparency and accountability systems. Participants felt there were no clear systems and procedures for involving stakeholders, especially community-level stakeholders, in monitoring the DACF projects. For example, there were no PM&E clauses in contractual agreements mandating service providers who implemented DACF projects to cooperate with community-level stakeholders in monitoring projects. Furthermore, project or contract documents were not available to service departments and community-level stakeholders to enable them to track project implementation effectively. Yet the literature suggests (Crawford 2004; Hilhorst and Guijt 2006) that having written agreements that detail communication mechanisms between all stakeholders, including the contractors, and ensuring that all stakeholders are fully aware of what is included in the contract and what is not, are essential to ensure the effectiveness of PM&E.

One community member gave the following example: “I once prompted a contractor that his artisans were not executing quality workmanship and he shut me down by retorting to me in the following way: ‘Who are you to meddle in my work?’” (interview with community member, May 2018).

The issue of operational clarity was not limited to the local level. It also emerged from the interviews that policy and operational guidelines for PM&E provided by the NDPC were not detailed enough to inform practice at the district level. As one informant said: “In the absence of clear instructions, we applied PM&E on the DACF projects we implemented as we understood it from reading the NDPC’s M&E guidelines” (interview with district-level stakeholder, June 2018).

Having adequate guidelines to regulate practices is critical to the effectiveness of local governance. However, very detailed and specific guidelines have both pros and cons. Flexible guidelines, as are currently used in Ghana, give local governments space to be innovative in their application, but they may not be implemented effectively, especially in a context where participatory governance is still evolving and capacity for its operationalisation is weak. The need for mimumum conditions for participatory monitoring and evaluation to be effective at the local is captured by a key informant as follows:

There is the need for PM&E guidelines to specify a minimum standard of participation that must be met by every local authority. These minimum standards need to include: non-negotiable roles and responsibilities, especially at community level; tools and techniques to be employed for PM&E; provisions in contractual agreements to ensure community-level stakeholders’ involvement in monitoring of project progress; development of checklists and templates for community-level monitoring and reporting; and creation of anonymous complaints reporting systems at district, regional and national levels (interview with district-level stakeholder, June 2018).

On the issue of weak systems for transparency and accountability, the World Bank (2009, cited in Muriungi 2015, p. 61) notes that transparency and accountability in the use of resources is critical to effective PM&E. Brinkerhoff (2001) posits that within the continuum of accountability, answerability refers to the obligation to provide information and explanations concerning decisions, actions and inactions, while enforcement is the ability of overseers to apply sanctions when actors give unsatisfactory answers.

In the case of DACF projects in Ghana, the successful application of PM&E depends on the effective supervision of the staff of the assembly by the DCD, backed by oversight from the DCE. The DCE is the political head of the assembly, and the DCD is its administrative head and the principal advisor to the DCE, so both should be held accountable for the quality of projects. Assigning this accountability to them would re-orient their thinking and priorities to give attention to PM&E, ensuring that there is effective answerability and enforcement within the local governance system. However, at present this does not usually happen, due to failures on the part of overseeing institutions to identify weaknesses in PM&E practices, sanction DACF project contractors for non-compliance, and build the capacity of staff.

One informant had this to say on oversight responsibility: “Ever since I joined the Local Government Service years ago, no study has ever been conducted to objectively assess our capacity gaps to help us implement PM&E effectively” (interview with district-level stakeholder, June 2018). Another district-level informant suggested that key assembly managers were not always committed to PM&E: “I can show you copies of memos that the DCD and DCE have failed to approve to enable us involve our stakeholders in our M&E exercises” (interview with district-level stakeholder, May 2018).

Low levels of participation in PM&E projects were ascribed by participants to both inadequate clarity in protocols for engaging stakeholders and weaknesses in accountability measures within districts. Participants reported that the core staff in the district administration were the main actors involved in monitoring. Staff of decentralised line departments and local-level stakeholders did not play meaningful or decision-making roles in choosing indicators for monitoring, monitoring procedures, or frequency of monitoring actions. Stakeholders were neither involved in the design of the PM&E checklists nor provided with opportunities to meaningfully participate in either the PM&E exercises or the analysis and interpretation of PM&E data. One member of staff had this to say on their involvement in the PM&E process: “We occasionally were part of a team that went out on field monitoring. However, we often did not receive adequate briefing on the purpose of the monitoring, what we were to be on the look[out] for among others” (interview with service department, May 2018). The chiefs and assembly members who were involved in monitoring had similar views to the decentralised departments: they also saw themselves as observers rather than active participants in the monitoring process.

Several studies have made similar observations of a low level of participation by stakeholders in the decentralised PM&E of local governments (Sulemana et al. 2018; Akanbang and Bekyieriya 2020; Akanbang 2021). It is almost axiomatic that the quality of PM&E depends on the quality of citizen input, and many researchers have highlighted various facets of this issue: the degree of citizen participation (Danielsen et al. 2010; Fernandez-Gimenez et al. 2008); the level of direct citizen involvement in the design and supervision of community development projects (Wong and Guggenheim 2005); and the quality of information exchange (Helling et al. 2005; KIT and World Bank 2006). Therefore, a low level of participation has negative implications for community empowerment. As noted by Biekart (2005) and Cornwall (2006), for people to be empowered they should be actively involved in decision-making processes, have power to influence a project’s outcome, and participate actively in project implementation.

Distribution of power

Another key issue raised by informants was that projects focused on human and social development – as opposed to capital projects – were given a low priority, and that this weakened citizen power and control. The emphasis on physical projects by the political class at local and national levels undermines investment in the ‘soft’ aspects of development, including investments in PM&E. Excessive partisanship in politics, within a context of generally low levels of education among a significant portion of the citizenry, orients the political class towards physical projects because they provide ‘quick wins’ and political gains. A key informant conveyed the limited attention to ‘soft’ projects in the following terms: “A former DCE once told me that he would never release resources to implement projects he cannot point to as his achievement” (interview with district-level stakeholder, June 2018).

Consequently, informants reported that limited attention was given to capacity development for PM&E and related activities. The unwillingness of decision-makers at the district level to appreciate the potential value of PM&E in the district governance process, especially for decentralised departments and community-level stakeholders, contributed to the weak development of PM&E. The wider literature indicates that an organisational culture that rewards innovation, openness and transparency, and local authorities and service providers that acknowledge and value PM&E processes, have been identified as critical to the ability of PM&E to positively influence local governance (Hilhorst and Guijt 2006). Similarly, Tengan and Aigbavboa (2016) and Jili and Mthethwa (2016) highlight the commitment of financial resources as key to the operationalisation of PM&E. These findings suggest that senior decision-makers should receive tailored training on PM&E to enable them to understand, appreciate and become champions of PM&E in their districts.

Weak citizen power and control emerged as a key factor undermining the effectiveness of PM&E. The top-down approach which has marked the history of development in many developing countries has made many communities over-dependent on external solutions to their problems. This orientation is only deepened by social interventions which are prefixed with the word ‘free’. A district-level stakeholder shared his frustration with the state and level of dependency of communities as follows: “After providing DACF projects for our communities, they still depend on us to maintain them when they break down” (interview with district-level stakeholder, June 2018).

This dependency, apart from entrenching the poverty of communities, weakens their capacity to demand their rights and to hold public servants accountable. This feeling was vividly captured by an informant as follows: “Because we depend on the assembly for many things, we are afraid to do anything that may annoy them” (interview with community stakeholder, May 2018). This situation is compounded by weaknesses in feedback processes from communities on the quality of project delivery. Concerns about the implementation of projects were not brought to the attention of the contractor or the district assembly because of fear of victimisation either individually or as a community. As another community-level informant put it: “I failed to approach and complain to the contractor because I was afraid that if I did that I would have been victimised at the instance of the contractor because he has strong political connections” (interview with community stakeholder, May 2018). In the absence of systems of anonymous reporting of complaints, and where there is a strong perception of contractors as powerful people who are connected to the political elite, non-adherence to contract provisions for project implementation at the community level is likely to continue to be the order of the day.

In line with the rights-based approach to development (Kyohairwe 2014), there is the need to build the capacity of communities to recognise and claim their rights, and to make staff of local authorities honour their responsibility to involve them in monitoring and evaluating projects. This approach advocates shifts from needs-based to rights-based, from service delivery to capacity development and advocacy, and from charity to duties (D’Hollander et al. 2013). Essential elements are participation, accountability, non-discrimination, empowerment and linkage to human rights norms (Cornwall and Nyamu-Musembi 2004). From the perspective of the rights-based approach, poverty is the result of disempowerment and exclusion. Consequently, advocates seek to empower citizens to recognise and claim their rights and make service providers accountable (Harris-Curtis 2003; Cornwall and Nyamu-Musembi 2004; Uvin 2007; D’Hollander et al. 2013). In Ghana, this will help to address the dependency syndrome in communities as well as make the district assembly and service providers, both public and private, more accountable. Specifically, community-level stakeholders should be informed about the terms of contracts, with particular regard to indicators, targets and work schedules, and relevant documentation should be made available to them, so that they can participate in monitoring projects.

Conclusion and recommendations

PM&E is here to stay within local government systems in the developing world, as witnessed by its incorporation in policy guidelines for decentralised monitoring at local level. A wealth of conceptual and theoretical literature demonstrates that PM&E has the ability to enhance the local capacity and skills of project partners as well as to promote downwards, lateral and upwards accountability (Estrella et al. 2000; Vernooy 2003; Akin et al. 2005; Jütting et al. 2005; Woodhill 2005; Göergens and Kusek 2010; Akanbang 2012; Matsiliza 2012; Porter and Goldman 2013; Mascia et al. 2014; Rossman 2015; Kananura et al. 2017; Akanbang and Bekyieriya 2020). Generating evaluation results helps citizens to address challenges in project implementation to their own advantage, while simultaneously increasing ownership and therefore commitment to ensuring successful outcomes.

However, this study has reaffirmed the factors hindering effective PM&E in local government systems highlighted by the empirical literature (low prioritisation and budgetary support for PM&E, and low levels of participation by community-level stakeholders). It has also identified emerging inhibitors in the Ghanaian context (although probably not unique to Ghana): weaknesses in procedures and processes at district level for involving local-level actors in the PM&E process; lack of clarity in policy guidelines and manuals; weak systems for transparency and accountability; and weak citizen power and control. These all need to be taken into consideration in efforts to enhance the practice of PM&E in local governance.

Thus, despite the enormous potential benefits that PM&E offers for the development of Ghanaian communities through better local governance, it faces many challenges. There is a need for concerted collaboration by all stakeholders with an interest in PM&E (policy-makers, researchers, implementers and project beneficiaries) to provide a practical response to these challenges, taking local context into account. Further research should focus on the roles and accountability of PM&E stakeholders, as well as the scope for success through simplification and clarification of decentralised PM&E arrangements. This should be linked to strengthening the rights-based approach to development at the community level, which is critical to building community capacity for self-organisation, confidence, determination and fulfilment in the developing world.

At the policy level, best practice guidelines are needed to provide clarity on minimum conditions for PM&E; and those conditions should not be difficult to implement. In the Ghanaian context, the following key stakeholders should be involved in and held accountable for the quality of decentralised government projects: the district head of the beneficiary institution (eg district director of health); the head of the local/community beneficiary institution (eg headmaster of an existing school, officer in charge of a CHPS compound etc); the assembly member of the beneficiary community or the chairperson/secretary of the beneficiary community’s unit committee; the responsible officer from the public works department; and relevant staff of the DPCU and district finance office. Thus a minimum of six district-level and community-level stakeholders should play a role.

Further capacity development for PM&E is also required, at both district and community levels. Critical areas for improvement include mechanisms for giving and receiving complaints at community and district levels; development of protocols for collecting, analysing, reflecting on and reporting monitoring data and information; and needs assessment to inform a training programme for stakeholders in monitoring. More broadly, further empirical research is required to uncover the causes of the limited involvement of citizens in decentralised democratic local government systems – where in principle participation should be a key pillar of governance.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

Ahwoi, K. (2008) Monitoring and evaluation in participatory governance. Local Governance & Development Journal, 2 (2), 65–74.

Akanbang, B.A.A. (2012) Programme implementers experiences of process use in three programme evaluation contexts in Northern Ghana. Accra: University of Ghana.

Akanbang, B.A.A. (2021) Monitoring of water and sanitation services within an integrated decentralized monitoring systems: experiences from Ghana. Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development, 11 (3), 461–473. https://doi.org/10.2166/washdev.2021.261

Akanbang, B.A.A. and Bekyieriya, C. (2020) Decentralised monitoring in emerging local governments: an analysis of benefits and constraining factors in the Lawra municipality, Ghana. Ghana Journal of Development, 17 (2), 72–94. https://doi.org/10.4314/gjds.v17i2.4

Akin, J., Hutchinson, P. and Strumpf, K. (2005) Decentralisation and government provision of public goods: the public health sector in Uganda. The Journal of Development Studies, 41 (8), 1417–1443. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380500187075

Bartecchi, D. (2016) The role of participatory monitoring and evaluation in community-based development Armenia: Village Earth Participatory Strategic Planning Workshop.

Biekart, K. (2005) Latin America policies of European NGOs: recent trends and perspectives. Institute of Social Studies (ISS). Available at: https://repub.eur.nl/pub/32242/

Boissiere, M., Bastid, F., Basuki, I., Pfund, J.L. and Boucard, A. (2014) Can we make participatory NTFP monitoring work? Lessons learnt from the development of a multi-stakeholder system in Northern Laos. Biodiversity and Conservation, 23 (1), 149–170. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-013-0589-y

Brinkerhoff, D.W. (2001) Taking account of accountability: a conceptual overview and strategic options. Washington: Abt Associates Inc.

Castleberry, A. and Nolen, A. (2018) Thematic analysis of qualitative research data: is it as easy it sounds? Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning, 10 (6), 807–815. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cptl.2018.03.019

Cornwall, A. (2006) Historical perspectives on participation in development. Commonwealth & Comparative Politics, 44 (1), 62–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/14662040600624460

Cornwall, A. and Nyamu-Musembi, C. (2004). Putting the ‘rights‐based approach’ to development into perspective. Third World Quarterly, 25 (8), 1415–1437. https://doi.org/10.1080/0143659042000308447

Cracknell, B.E. (2000) Evaluating development aid: issues, problems and solutions. New Delhi, Thousands Oak, London. Sage Publications.

Crawford, S. (2004) Lessons learned so far: a guide to RBD in practice. Consultancy Report. Malawi: Participatory rights assessment (PRAss) and rights-based development in the Education Sector Support Programme (ESSP).

Danielsen, F., Burgess, N., Jensen, P.M. and Pirhofer-Walzl, K. (2010) Environmental monitoring: the scale and speed of implementation varies according to the degree of people’s involvement. Journal of Applied Ecology, 47 (6), 1166–1168. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2010.01874.x

D’Hollander, D., Pollet, I. and Beke, L. (2013) Promoting a human rights-based approach (HRBA) within the development effectiveness agenda. Leuven: KU Leuven, Research Institute for Work and Society.

Estrella, M., Blauert, J., Campilan, D. and Gaventa, J. (2000) Learning from change: issues and experiences in participatory monitoring and evaluation. London and Ottawa: Intermediate Technology Publications Limited and the International Development Research Centre. https://doi.org/10.3362/9781780441214

Fernandez-Gimenez, M.E., Ballard, H.L. and Sturtevant, V.E. (2008) Adaptive management and social learning in collaborative and community-based monitoring: a study of five community based forestry organizations in the western USA. Ecology and Society, 13 (2). https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-02400-130204

Garcia, C.A. and Lescuyer, G. (2008) Monitoring, indicators and community-based forest management in the tropics: pretexts or red herrings?. Biodiversity and Conservation, 17 (6), 1303–1317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-008-9347-y

Ghana Statistical Service. (2014) Ghana living standard survey round six. Accra: Government of Ghana.

Göergens, M. and Kusek, J.Z. (2010) Making monitoring and evaluation systems work: a capacity development toolkit. Washington, DC: World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-0-8213-8186-1

Government of Ghana. (1992) Constitution of the Republic of Ghana. Accra: Ghana

Government of Ghana. (2016) Local Government Act, Act 936, Accra: Ghana.

Harnar, M.A. and Preskill, H. (2007) Evaluators’ descriptions of process use: an exploratory study. New Directions for Evaluation, (116), 27–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/ev.241

Harris-Curtis, E. (2003) Research round-up. Rights-based approaches – issues for NGO’s. Development in Practice, 13 (5), 558–564. https://doi.org/10.1080/0961452032000125956

Helling, L., Serrano, R. and Warren, D. (2005) Linking community empowerment, decentralised governance and public service through a local development framework. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Hilhorst, T. and Guijt, I. (2006) Participatory monitoring and evaluation: a process to support governance and empowerment at the local level. A Guidance Paper. Amsterdam: KIT.

Ibrahim, A.S., Akanbang, B.A., Nunbogu, A.M. and Kuusaana, E.D. and Ahmed. A. (2020) Collaborative customary land governance: motivations and challenges of forming land management committees (LMCs) in the upper west region of Ghana. Land Policy Use, 99, 105051. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.105051

Jili, N.N. and Mthethwa, R.M. (2016) Challenges in implementing monitoring and evaluation: the case of Mfolozi municipality. African Journal of Public Affairs, 9 (4), 102–113.

Jütting, J., Corsi, E., Kauffmann, C., Mcdonnell, I., Osterrieder, H., Pinaudand, N. and Wegner, L. (2005) What makes decentralisation in developing countries pro-poor? The Europena Journal of Development Research, 17 (4), 626–648. https://doi.org/10.1080/09578810500367649

Kananura, R.M., Ekirapa-Kiracho, E., Paina, L., Bumba, A., Mulekwa, G., Nakiganda-Busiku, D., Oo, H.N.L., Kiwanuka, S.N., George, A. and Peters, D.H. (2017) Participatory monitoring and evaluation approaches that influence decision-making: lesson from a maternal and newborn study in Eastern Uganda. Health Research Policy and Systems, 15 (2), 107. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-017-0274-9

KIT and World Bank. (2006) Community driven development: a national stocktaking and review toolkit. Washington DC: KIT and World Bank Africa Region.

Kyohairwe, S. (2014) Local democracy and public accountability in Uganda: the need for organisational learning. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, (15), 86–103. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.v0i0.4064

Lambussie District Assembly. (2014) 2013–2014 District medium term development plan. Lambussie, Upper West Region: Ghana.

Mascia, M.B., Pailler, S., Thieme, M.L., Rowe, A., Bottrill, M., Danielson, F. and Burgess, N.D. (2014) Commonalities and complementarities among approaches to conversation monitoring and evaluation. Biological Conservation, 169, 258–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2013.11.017

Matsiliza, N. (2012) Participatory monitoring and evaluation: reviewing an inclusive approach in South Africa. Africa’s Public Service Delivery and Performance Review, 1 (2), 67–83. https://doi.org/10.4102/apsdpr.v1i2.31

Miles, M.B. and Huberman, M.A. (1994) Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. California: Sage.

Miller, R.L. and Campbell, R. (2006) Taking stock of empowerment evaluation: an empirical review. American Journal of Evaluation, 27 (3), 296–319. https://doi.org/10.1177/109821400602700303

Morgan, D.L. and Krueger, R.A. (1997) The focus group guidebook. Oregon: Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483328164

Muriungi, T.M. (2015) The role of participatory monitoring and evaluation programmes among government corporations: a case of Ewaso Ngi’ro north development authority. International Academic Journal of Social Sciences and Education, 1 (4), 53–76.

Musomba, S.K., Muthama, F., Nicholas, M. and Kilika, S. (2013) Factors affecting the effectiveness of monitoring and evaluation of constituency development fund in Changamwe constituency, Kenya. Journal of International Academic Research for Multidisciplinary, 1 (8), 175–216.

Naidoo, I.A. (2011) The role of monitoring and evaluation in promoting good governance in South Africa: a case of Department of Social Development. Johannesburg: University of Witwatersrand.

National Development Planning Commission. (NDPC) (2014) Guidelines for the preparation of 2013–2014 district monitoring and evaluation plans: Ghana Shared Growth Development Agenda (GSGDA I). Accra: NDPC.

Oloo, D.O. (2011) Factors affecting the effectiveness of monitoring and evaluation of constituency development fund projects in Likoni constituency, Kenya. Nairobi: University of Nairobi.

Porter, S. and Goldman, I. (2013) A growing demand for monitoring and evaluation in Africa. African Evaluation Journal, 1 (25), 1–9.

Rossman, G.B. (2015) Participatory monitoring and evaluation. Amherst: University of Massachusetts.

Sulemana, M., Musah, A.B. and Kaba, S.K. (2018) An assessment of stakeholder participation in monitoring and evaluation of district assembly projects and programmes in the Savelugu-Nanton Municipality Assembly, Ghana. Ghana Journal of Development Studies, 15 (1), 173–195. https://doi.org/10.4314/gjds.v15i1.9

Tengan, C. and Aigbavboa, C. (2016) Evaluating barriers to effective implementation of project monitoring and evaluation in the Ghanaian construction industry. Procedia Engineering, 164, 389–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2016.11.635

Uitto, J.I. (2006) Monitoring and evaluation challenges: from projects to development results. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysian Evaluation Society-Second Evaluation Conference.

Uvin, P. (2007) From the right to development to the rights-based approach: how ‘human rights’ entered development. Development in Practice, 17 (4-5), 597–606. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614520701469617

Vernooy, R. (2003) Learning by doing in Guizhou and Yunnan provinces. In: Vernooy, R., Qiu, S., Xu, J. and Jianchu, X. (eds.) Voices for change: participatory monitoring and evaluation in China, (pp 1-21). Ottawa: International Development Research Center.

Vernooy, R. (2005) Participatory monitoring and evaluation: readings and resources. 2nd ed. Ottawa: The Rural Poverty and Environment Program Initiative, IDRC.

Villasenor, E., Porter-Bolland, L., Escobar, F., Guariguata, M. R. and Moreno-Casasola, P. (2016) Characteristics of participatory monitoring projects and their relationship to decision-making in biological resource management: a review. Biodiversity Conservation. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-016-1184-9

Wong, S. and Guggenheim, S. (2005) Community driven development: decentralization’s accountability challenge. In: World Bank (ed) East Asia decentralizes: making local government work, (pp. 253–267).Washington DC: The World Bank.

Woodhill, J. (2005) M&E as learning: rethinking the dominant paradigm. Wageningen: World Association of Soil and Water Conservation.

World Bank. (2010) Challenges in monitoring and evaluation: an opportunity to institutionalize M&E system. Washington, DC: World Bank.