Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance

Issue 25

December 2021

RESEARCH AND EVALUATION (PEER REVIEWED)

Indigenous Peoples’ Human Rights, Self-Determination and Local Governance – Part 2

Ed Wensing

Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, Australian National University,

Canberra ACT 2601, Australia, edward.wensing@anu.edu.au

Corresponding author: Ed Wensing, Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, Australian National University, Canberra ACT 2601, Australia, edward.wensing@anu.edu.au

DOI: http://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi25.8025

Article History: Received 06/11/21; Accepted 14/12/21; Published 30/12/21

Citation: Wensing, E. 2021. Indigenous Peoples’ Human Rights, Self-Determination and Local Governance – Part 2. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, 25, 133-160. http://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi25.8025

© 2021 by the author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Abstract

Part 1 of this article explored the relevance of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples of Australia, particularly the key principles of self-determination and free, prior and informed consent; how the international human rights framework applies in Australia; and Australia’s lack of compliance with it. Part One concluded by discussing the Uluru Statement from the Heart, presented to all the people of Australia in 2017, and how it marked a turning point in the struggle for recognition by Australia’s Indigenous peoples.

Part 2 explores recent developments since the release of the Uluru Statement, especially at sub-national levels, in relation to treaty and truth-telling. It draws some comparisons with Canada and New Zealand, discusses the concept of coexistence, and presents a set of Foundational Principles for Parity and Coexistence between two culturally distinct systems of land ownership, use and tenure.

Introduction – coexistence and land

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ grievances with the Australian nation have been summarised by Professor Mick Dodson, a Yawuru man from Broome in the Kimberley region of Western Australia and Australia’s first Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, as follows:1

No consent was given to the colonisers to occupy and settle this land. What the colonisers did was wrong in so many ways. And the nation-state continues to refuse to address these wrongs comprehensively within a human rights framework. … We can fix your problem. Sit down and talk to us about it. Let’s negotiate our way through this.

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples of Australia have long accepted the need for coexistence between their system of land ownership, use and tenure and that devised by the British Crown. Indeed, coexistence is now deeply embedded in Aboriginal peoples’ perceptions of how those systems should interact with each other (Howitt 2006, p. 64; Brigg and Murphy 2011, p. 26). They seek coexistence on equal terms between the two systems of law and custom, not one always prevailing over the other.

There are two laws. Our covenant and white man’s covenant, and we want these two to be recognised… We are saying we do not want one on top and one underneath. We are saying that we want them to be equal (David Mowaljarlai, Elder, Ngarinyin people, Western Australia, 1997).2

First Nations peoples are clearly not satisfied with the form of coexistence introduced by the High Court of Australia in Wik Peoples v State of Queensland.3 It predicated recognition of native title on the basis of “remnant possibilities” (Walker 2015, p. 19) left after priority was given to the Crown’s land tenures, merely because the two sets of rights and interests could not be exercised simultaneously (Strelein 2009, p. 35).

According to Howitt (2019, p. 7) “coexistence is foundational in the ongoing challenge of recognising, respecting and accommodating human diversity”. People and cultures all bring different sorts of claims, relationships and understandings to the same lands and spaces, and with each other, and all of these factors have implications for just, equitable and sustainable decision-making about ownership, occupation and use of land (Howitt and Lunkapis 2010, p. 109).

Application of this concept of coexistence demands that we confront the realities of our mutual responsibilities – those of colonial-settler societies and Indigenous societies – for land justice: “responsibilities that arise from living together in shared spaces that demand an unsettling of deep colonial power relations” (Porter and Barry 2016, p. 19). It also requires “an acceptance of multiple and overlapping jurisdictions” where our “plural relations to and governance of place all have relevance and standing” (Porter and Barry, pp. 5–6). Furthermore, coexistence is about a “mediation on discomfort” (Watson 2007, p. 30), in that it means “acknowledging uncomfortable questions” about how lawful Australia’s sovereign status is and how Australia established its legal and land administration systems which Brennan J in Mabo (No. 2) held “cannot be destroyed” or the “skeletal principles of which cannot be fractured”.4

Establishing a mutually respectful coexistence with respect to property in land between First Nations peoples and the Crown involves challenging the power asymmetry between the parties, respecting the parity of two distinctly different approaches to land ownership and governance, and negotiating their interaction through agreements on matters of mutual concern (Wensing 2016, p. 51). It must include recognition of First Nations’ pre-existing sovereignty, the integrity of their law and custom, and their right to self-determination and governance over their affairs, especially their ancestral lands and waters.

And therein lies the need for a treaty or ‘Makarrata’, a Yolngu word from north-eastern Arnhem land in the Northern Territory of Australia, sometimes translated as “things are alright again after a conflict” or “coming together after a struggle” (Hiatt 1987, p. 140).5

The Uluru Statement’s ‘Guiding Principles’

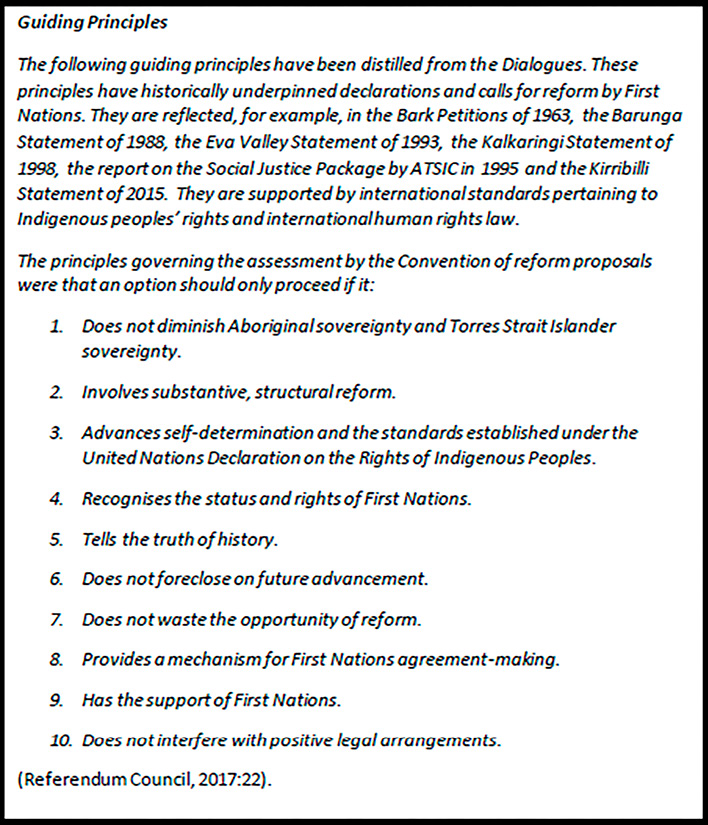

As outlined in Part 1 of this paper, the Uluru Statement from the Heart (Figure 1) emerged from a series of regional Dialogues which culminated in a National Constitutional Convention held at Uluru in central Australia on the land of the Aṉangu People in May 2017. The Dialogies and Convention were organised by a Referendum Council appointed by the then prime minister and leader of the opposition to lead a process of national consultations about constitutional recognition of Australian’s First Nations Peoples (Referendum Council 2017a). Significantly, the Uluru Statement was deliberately issued to all the people of Australia rather than their political leaders because “the people of Australia… understand the current climate of policy inertia and it is they who ultimately can change the Constitution’s text” (Davis 2017, p. 132).

Figure 1. Uluru Statement from the Heart, May 2017

Source: Referendum Council (2017b)

Reforms that had emerged with the highest level of support from the Dialogues were “the Voice to Parliament, Agreement-making through Treaty, and Truth-telling” (Referendum Council 2017a, p. 15). However, the Australian (federal) government’s negative response to the Uluru Statement (Turnbull et al. 2017) was “a stunning repudiation of the historic Indigenous agreement painstakingly reached at Uluru” (Lino 2018, p. 67). It was very clear that the conservative government would not go down the path of a national treaty or truth-telling. Also, while the government subsequently initiated a co-design process for a legislated Voice to Parliament and to improve local and regional decision-making (Wyatt, K. 2019), this does not satisfy the Referendum Council’s (2017a) call for a constitutionally enshrined Voice that cannot be abolished by a future government. At the time of writing, the government was yet to indicate precisely how it intends to proceed.

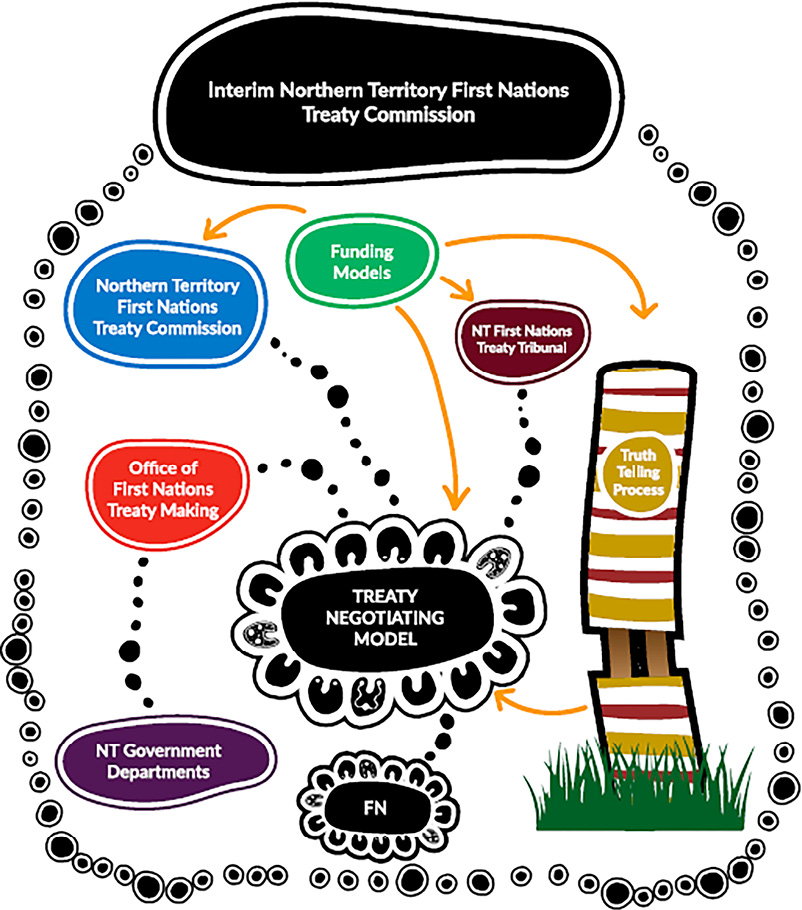

In the course of conducting the Dialogues, the Referendum Council developed a set of Guiding Principles for assessing and deliberating on reform proposals. These were discussed and adopted by consensus at the Uluru Convention (Referendum Council, 2017a, p. 22) and are reproduced in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Guiding Principles developed by the Referendum Council, 2017

Source: Referendum Council (2017a, p. 22)

The first principle concerns Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander sovereignty. Centring sovereignty in the Uluru Statement was deliberate, reflecting historic grievances with the Crown: “Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples were the first sovereign Nations of the Australian continent and its adjacent islands, and possessed it under our laws and customs” (Referendum Council 2017b). To convey the meaning of sovereignty, the Statement invoked international law on decolonisation and self-determination.

This sovereignty is a spiritual notion: the ancestral tie between the land, or ‘mother nature’, and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who were born therefrom, remain attached thereto, and must one day return thither to be united with our ancestors. This link is the basis of the ownership of the soil, or better, of sovereignty. It has never been ceded or extinguished, and co-exists with the sovereignty of the Crown (Referendum Council 2017b).

The need for truth-telling emerged from the Dialogues because “the true history of colonisation must be told: the genocides, the massacres, the wars and the ongoing injustices and discrimination” (Referendum Council 2017a, p. 32). Principle 5 therefore reflects the importance of truth-telling to heal the relationship between First Nations and Australia as a whole, echoing the United Nations (UN) Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (‘UNDRIP’, UN 2007); the resolution on the Right to the Truth adopted by the UN Human Rights Council (UN 2012); and the similar resolution passed by the UN General Assembly in 2013 (UN 2013).

Principle 8 is about agreement-making through treaty. The right to treaties, agreements and other constructive arrangements with nation states is enshrined in Article 37 of UNDRIP. Gover (2020 pp. 77–78) argues that Article 37 is a declaration that treaty guarantees are not to be diminished by other provisions in UNDRIP and therefore it “appropriately exemplifies the kind of priority that historical collective Indigenous rights must have if they are to be adequately protected from the competing claims of third parties”. Gover (2020) also asserts that Article 37 “conveys the correct (in this author’s view) understanding of appropriately concluded treaties as quasi-contractual constitutional agreements that are not subject to general norms of distributive justice, individual rights and non-discrimination principles”. Current treaty developments in Australia provide an excellent opportunity to include references to Article 37 in preambular paragraphs and also in any legislative and regulatory mechanisms implementing them.

The Uluru Statement represents a major turning point in Australia’s national conversation about First Nations’ rights precisely because it not only sets out Indigenous peoples’ outstanding grievances, but also invites the Australian people to engage with them through treaty and truth-telling. While the Australian government’s response has been at best disappointing, significant progress is being made in Australia’s states and territories.

Treaty developments

Since the release of the Uluru Statement, five of Australia’s eight sub-national jurisdictions have committed to treaty or treaties. In order of commencement, those are Victoria, the Northern Territory (NT), Queensland, the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) and Tasmania.6 Also, in Western Australia a recent native title settlement has several hallmarks of a treaty. Some of these sub-national developments are arguably world-class.

Victoria

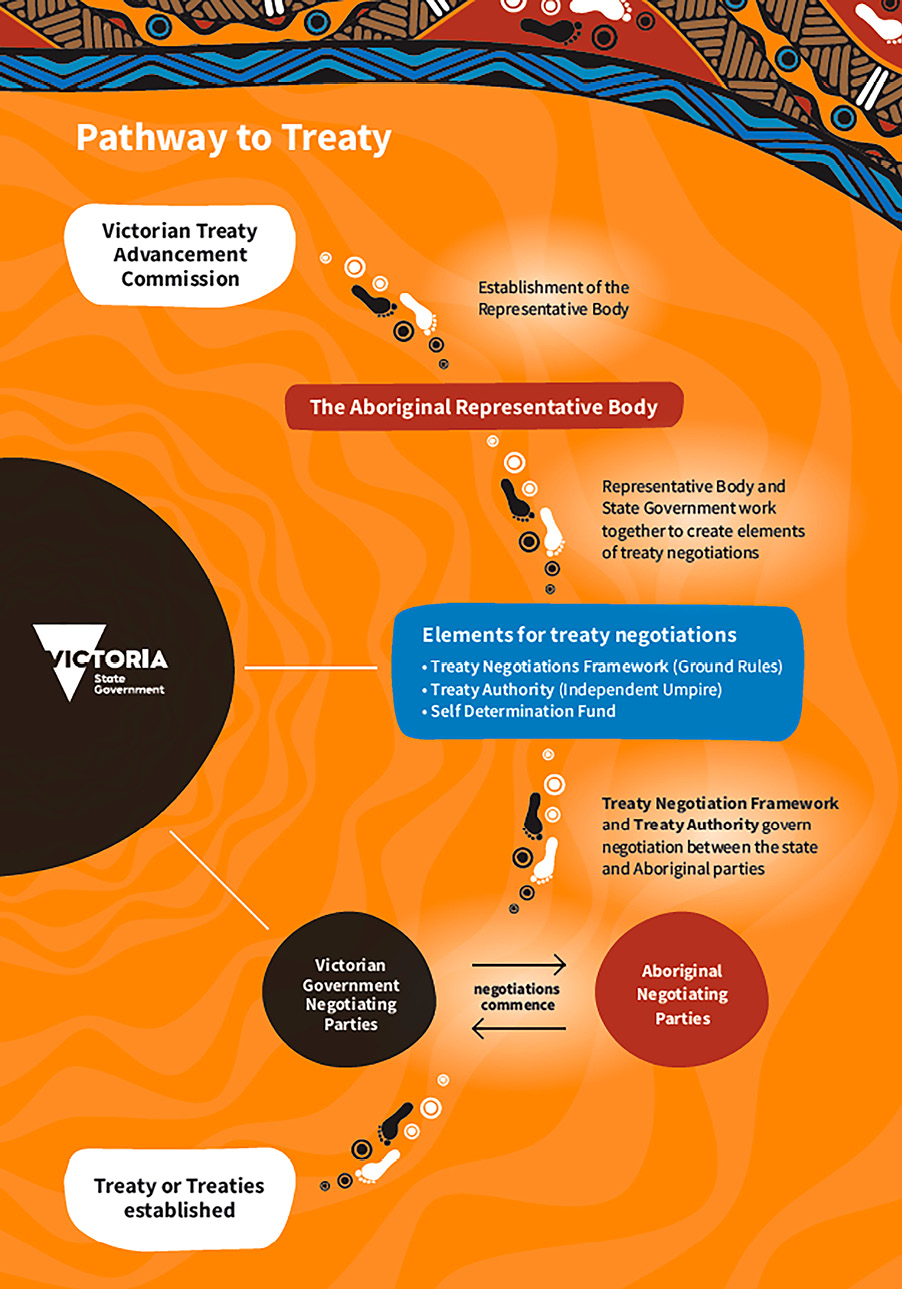

The ‘Aboriginal community’7 of Victoria and the Victorian government have been working toward a treaty since February 2016 (Government of Victoria 2016). The government has acknowledged the need for a state-wide Aboriginal representative body with which it could negotiate and that the process of self-determination “has to start with Aboriginal Victorians” (Hutchins 2016). It has adopted the pathway shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Pathway to Treaty in Victoria

Source: Victorian Treaty Advancement Commission (2018)

The first step was to enact the Advancing the Treaty Process with Aboriginal Victorians Act 2018, the first attempt to legislate a treaty process with Aboriginal Australians. Notably, the preamble states that Aboriginal Victorians maintain their sovereignty was never ceded, that they have long called for treaty, that these calls have gone unanswered, and that the time has now come for Aboriginal Victorians and the State to talk treaty. The Act established a Treaty Advancement Commission charged with creating an Aboriginal representative body and developing a treaty negotiation framework. This led to the establishment of the First Peoples’ Assembly of Victoria (FPAV) as the elected voice for Aboriginal people and communities in treaty discussions, and as the State’s equal partner in the next phase of the pathway.

The role of the FPAV is not to negotiate a treaty or treaties, but rather to work with the government to create a framework of rules and processes for reaching agreement. The Act requires the FPAV and the state government to establish four mechanisms to support treaty negotiations: a treaty authority; a treaty negotiation framework; a self-determination fund; and an ethics council (Victorian Parliamentary Library and Information Service 2018, p. 4). To reinforce its independence from the Victorian government, the FPAV is a company limited by guarantee. It has developed its own constitution (FPAV 2019) and a governance framework about decision-making and the respective roles of the members, board, co-chairs and committee (FPAV undated). Importantly, all decisions on treaty-related matters are to be made by the Assembly members.

The FPAV was initially designed to comprise 33 seats: 21 determined through a popular voting process, and 12 reserved for formally recognised Traditional Owner groups. The Act allows the number to increase if more groups are established. Among the outstanding issues to be resolved is the imbalance between residents as distinct from Traditional Owners and the disparity about speaking on or for someone else’s Country. There are also concerns that the government compromised its message about Aboriginal-led processes by legislating the treaty pathway before the FPAV was established.8

There is much to be learned from the Victorian experience: specifically, the government’s commitment to transparency and openness from the very outset; the annual public reporting requirements of the various institutions (see for example, Government of Victoria 2019); and the government’s considerable efforts to engage with Traditional Owner voices across Victoria about their aspirations, challenges and relationships with government (Aboriginal Victoria 2019). This engagement took place within the broader social and political context of advancing Aboriginal self-determination. Most significant of all is the acceptance that the State and Aboriginal parties will have equal status in treaty negotiations. This is truly ground-breaking for an Australian jurisdiction and consistent with many of the Articles in UNDRIP.

Another notable feature is the role being played by the Federation of Victorian Traditional Owner Corporations (FVTOC), which has issued a series of papers exploring the foundations of and scope for a Victorian treaty.9 These papers make a valuable contribution to the discussion about treaties not only in Victoria, but in other jurisdictions as well. Particularly pertinent is the paper on how the native title system has worked out in Victoria following the High Court of Australia’s negative determination concerning the Yorta Yorta10 claim in 2002, and the subsequent passing of the Traditional Owner Settlement Act 2010 (Vic). It concludes that the Act “has not delivered on much of its early promise” (FVTOC 2021, p. 5), pointing to the need for land matters to be top of the agenda when treaty negotiations commence.

Northern Territory

In 1988, at the annual Barunga Festival, Australian prime minister Hawke was presented with a statement calling for Indigenous rights to be recognised. This became known as the ‘Barunga Statement’ (AIATSIS 1988). Speaking at the Festival, the prime minister agreed to the statement’s request for a treaty-making process, but this met with hostile opposition from conservative parties and was “quietly shelved in 1991” (Hobbs and Williams 2019, p. 24).

Almost 30 years later, the Northern Territory government decided in early 2017 to establish an Aboriginal Affairs Sub-Committee of Cabinet as a voice for the Territory’s Aboriginal people (NT Government 2019a). The sub-committee is chaired by the chief minister and has majority Aboriginal representation including the Minister for Aboriginal Affairs, three other Aboriginal members of the Legislative Assembly, and five advisers from regions across the Territory. Its role is to advise and monitor a whole of government approach to the Aboriginal Affairs agenda, including progressing treaty discussions (NT Government 2019b).

In March 2018, the Territory’s four Aboriginal Land Councils11 wrote to the chief minister proposing a memorandum of understanding (MoU) to advance a treaty consultation process (NT Government et al. 2018, p. 5). At a meeting the following month, it was agreed to establish a Treaty Working Group to develop the MoU. Its purpose would be to capitalise on the 30th anniversary of the Barunga Statement by facilitating consultation with all Aboriginal people in the NT to agree a framework for treaty negotiations. The Land Councils were particularly concerned to reflect the wide range of Aboriginal interests in the Territory and also to involve the non-Aboriginal community and gain its commitment. The MoU, known as the ‘Barunga Agreement’ was signed later in 2018, paving the way for consultations to begin (NT Government et al. 2018).

The Agreement states that “the key objective of any Treaty in the NT must be to achieve real change and substantive, long term, benefits for Aboriginal people’ and that it ‘needs to address structural barriers to [their] wellbeing” (NT Government et al. 2018, p. 9). There would be an independent Treaty Commission and the treaty process rests on the government’s express acceptance of three foundational propositions:

• Aboriginal people were the prior owners and occupiers of the land, seas and waters that are now called the Northern Territory of Australia;

• the First Nations of the Northern Territory were self-governing in accordance with their traditional laws and custom;

• First Nations peoples of the Northern Territory never ceded sovereignty of their land, seas and waters.

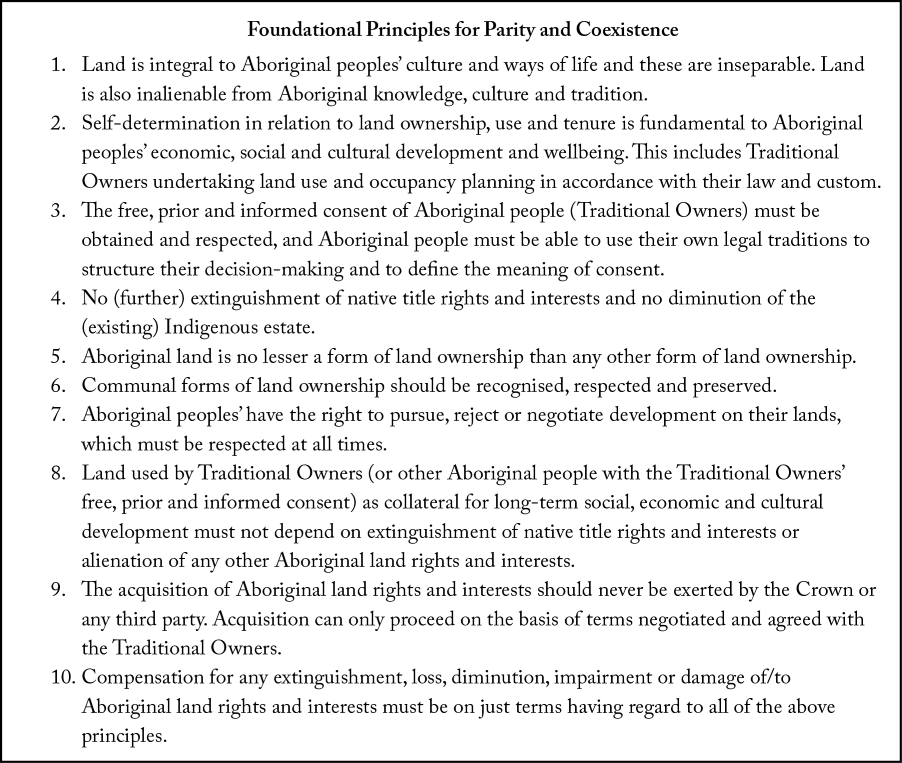

This provided “a great starting point for treaty discussions” (NT Treaty Commission 2020b, p. 9) and is consistent with many of the Preambular paragraphs of UNDRIP. In March 2020, the Treaty Commission released an Interim Report on Stage One (NT Treaty Commission 2020a) and in July 2020, a Treaty Discussion Paper (NT Treaty Commission 2020b). The paper provides a wealth of information about treaties and treaty-making, including national and international best practice, a possible framework for treaty-making and a model process for treaty negotiations, applying learnings from British Columbia in Canada, Aotearoa/New Zealand and Victoria (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Northern Territory Treaty Framework

Source: Northern Territory Treaty Commission (2020b, p. 66)

A potentially significant consideration for both the NT and the ACT (see below) is that under the Australian Constitution (Commonwealth of Australia 1901), the Australian Government can over-ride Territory laws on any subject. In a legal opinion to the NT Treaty Commission, Brett Walker SC (2020, p. 15) advised that “the support or acquiescence of the Commonwealth Executive and the Parliament would be useful reassurance throughout and after the process of negotiating a treaty or treaties”. The purpose would not be to involve the Commonwealth as a party, “but rather to keep it appropriately informed of the negotiations between the Northern Territory and its First Nations”.

Other jurisdictions

Queensland

In July 2019 the Queensland government committed to the Tracks to Treaty – Reframing the relationship with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Queenslanders initiative (Palaszczuk 2019). It established an Eminent Panel of Indigenous and non-Indigenous Queenslanders to engage with key parliamentary, government and non-government stakeholders; and a Treaty Working Group to lead the conversation with First Nations Queenslanders.

Reporting to the government in February 2020, the Working Group concluded there is broad support within the Queensland community for a treaty process, asserting that the Human Rights Act 2019 (Qld), a 2016 report Reconciling Past Injustice, and emerging conversations around treaty and truth-telling, all provided fertile ground to progress this issue (State of Queensland 2020a, p. 6). The Eminent Panel also presented its Advice and Recommendations in February 2020, confirming that the government should proceed on a Path to Treaty. This could:

• deal with the ‘unfinished business’ of the colonisation of Queensland and its devastating ongoing impact on First Nations;

• empower First Nations Peoples to deal with social and economic disadvantage that top-down government programmes have not, and never will be able to, address;

• advance reconciliation and justice between First Nations and all other Queenslanders;

• mark the maturity of Queensland to deal honestly with its history and provide the foundation for a path forward (State of Queensland 2020b).

In August 2020, the Queensland Government accepted, fully or in principle, the Eminent Panel’s recommendations and committed to a truth-telling and healing process, to supporting First Nations peoples to engage in treaty-making, and to raise awareness about Queensland’s shared history and the diversity of perspectives (Queensland Government 2020). In February 2021 a Treaty Advancement Committee was established to develop options and provide independent advice on how to progress treaty-making. It is expected to report by the end of 2021.

Australian Capital Territory

In October 2020 the ACT’s Labor and Greens government committed to “treaty discussions with traditional owners, informed by processes underway around the nation; supporting First Nations families with connections to country in the ACT to submit native title claims; and repealing and replacing the Namadgi National Park Agreement” (Barr and Rattenbury 2020, pp.18 and 24). The Namadgi Agreement, signed under a conservative government in 2001, had required the Aboriginal parties to withdraw all native title claims over any land in the ACT, and ruled out any new claims (ACT Government 2001). Its validity is doubtful (Wensing 2021a, pp. 29–30) and Aboriginal land rights and native title matters in the ACT remain unfinished business (Wensing 2021a, p. 58).

The ACT budget for 2021–22 provides $20m over ten years for a Healing and Reconciliation Fund, including funds to support a treaty process (ACT Government 2021a, p. 2). However, no further information is publicly available as to how this will proceed.

Tasmania

In June 2021 the Tasmanian Premier announced the appointment of a former state governor, Professor Kate Warner AC, “to facilitate a process to understand directly from Tasmanian Aboriginal people themselves how best to take our next steps towards reconciliation” (Gutwein 2021). Professor Warner was to report by October 2021 and make “recommendations outlining a proposed way forward towards reconciliation, as well as the views of Tasmanian Aboriginal people on a Truth Telling process and what a pathway to Treaty would consist of” (Government of Tasmania 2021, p. 7). The Tasmanian Government’s initiative is commendable, but the apparent haste in producing this first report is concerning, as other states and territories have taken much longer to develop their processes.

Western Australia

Following lengthy proceedings in both the Federal and High Courts and protracted negotiations over 18 years, the WA government and the Noongar people of the state’s south-west recently registered six Indigenous land use agreements under the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) as “full and final resolution of all native title claims … in exchange for a comprehensive settlement package” (Barnett 2015).12

The Noongar Settlement is by far the largest and most comprehensive reached to date in Australia and a “landmark and unprecedented outcome” (Jackson McDonald Lawyers 2016, p. 14). It involves some 30,000 Noongar people, covers approximately 200,000 square kilometres of land and waters, and includes agreements on rights, obligations and opportunities relating to land, resources, governance, finance, and cultural heritage (Hobbs and Williams, 2019, p. 31). The total value of the package is $1.3 billion. The Settlement requires recognition through an act of parliament, the establishment of a perpetual trust and six regional corporations, land transfers, joint management arrangements for the South West Conservation Estate, land and water access for customary purposes, heritage agreements, an economic participation framework, a housing programme, a community development programme, a capital works programme and a land fund.

The Settlement is intended to compensate the Noongar people “for the loss, surrender, diminution, impairment and other effects” levied on their native title rights and interests.13 In the words of the WA Minister for Aboriginal Affairs: “it’s as close as we’ve come in Australia to a treaty between a group of traditional owners and a government” (Wyatt, B 2018). However, it does not recognise self-government rights to the same extent as the modern treaties in Canada (Hobbs and Williams 2019, p. 204).

Truth-telling developments

There is now widespread understanding in Australia that genuine reconciliation cannot be achieved without confronting and acknowledging the legacy of the past through some form of truth-telling (Referendum Council 2017a; Coalition of Peaks 2020). Notably, the Uluru Statement called for a Makarrata Commission to “supervise a process of … truth-telling about our history” (Referendum Council 2017b). Once again, sub-national governments have responded positively, and the actions of two jurisdictions – the Northern Territory and Victoria – are consistent with the resolution on the Right to the Truth adopted by the UN Human Rights Council and later the General Assembly (UN 2013).

Northern Territory

In February 2021, the NT Treaty Commission (2021) released a paper discussing the role of truth-telling and truth-telling commissions, an overview of experiences in Australia and around the world, and truth-telling models that could work in the Territory. Truth-telling processes in other countries have played an important role in reconciliation by uncovering and acknowledging past human rights violations and ongoing injustices towards First Peoples. While there are diverse opinions about their successes or failures, Australia can learn from those experiences. Other countries examined by the NT Commission include Canada, South Africa, Guatemala, Mauritius, Peru and Timor-Leste. The Commission concludes that while “each place and its history is unique”, there are many common themes, “such as the impacts of colonisation, the forcible removal of children and intergenerational trauma” (NT Treaty Commission 2021, pp. 18–25).

The Commission also notes that while there has not been any official government-led truth-telling processes in Australia, truth-telling has occurred through land rights claims in the NT,14 Royal Commissions15 and one national inquiry16 (NT Treaty Commission 2021, p. 26). In the NT, the 2018 Barunga Agreement acknowledged the need for truth-telling and healing (NT Government et al. 2018). The Commission finds that “culturally appropriate structures and ownership of the truth telling process are integral to success” (NT Treaty Commission 2021, p. 33), and that while there is a need for swift action, there is an even greater need to get the process right: “…by tracing the journey back through these truths, we can start to weave a new story, what the Uluru Statement from the Heart terms a ‘fuller expression of Australia’s nationhood’” (p. 43). It thus recommended that a Truth Commission be established as soon as possible, and that consultation with Aboriginal people will be necessary to decide the specifics (NT Treaty Commission 2021, p. 5)

Victoria

One of the first resolutions of the FPAV in June 2020 was for the state government to establish a truth and justice process. The government responded positively, and in March 2021 the FPAV and the government announced the establishment of the Yoo-rrook Justice Commission (named for the Wemba Wemba/Wamba Wamba word for truth). It has been established under the Inquiries Act 2014 (Vic) with the powers of a Royal Commission to call evidence and to hold public hearings. This is the first formal truth-telling process about historical and ongoing injustices experienced by First Peoples in Victoria since colonisation (Williams 2020; Government of Victoria and Co-Chairs of the FPAV, 2021).

The Commission has been invested with the powers of a royal commission (Hobbs 2021). It will:

• Establish an official record and develop a shared understanding among all Victorians of the impact of colonisation, as well as the diversity, strength and resilience of First Peoples’ cultures.

• Make recommendations for healing, system reform and practical changes to laws, policy and education, as well as to matters to be included in future treaties (Yoo-rrook Commission 2021a, 2021b).

By establishing the Yoo-rrook Commission, Victoria is now the first and only jurisdiction in Australia to have begun implementing all three key elements of the Uluru Statement: Voice, Treaty and Truth.

Other jurisdictions

Commitments to truth-telling by other jurisdictions can be found in the Implementation Plans for the new National Agreement on Closing the Gap (NIAA 2020), the primary objective of which is to overcome the entrenched disadvantage still faced by too many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Those plans were released in September 2021.

The only commitment by the Commonwealth is in relation to its Stolen Generations Reparations Scheme in the NT and the ACT, where it retains jurisdictional responsibility for past wrongs. The Commonwealth’s Implementation Plan states that the truth-telling component of the Reparations Scheme sits “alongside the additional measures the Commonwealth is taking to progress truth-telling as part of the nation’s journey to reconciliation” (Commonwealth of Australia 2021, p. 18). However, no ‘additional measures’ about truth-telling can be found in the Plan, nor on any Australian government website about its policies and programmes relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

The ACT’s Implementation Plan states that truth-telling exposes the past, enables a better understanding of history and paves the way towards “authentic reconciliation” (ACT Government 2021b, p. 3). The Plan refers to the Healing and Reconciliation Fund mentioned earlier, but nothing further has been published about whether and how truth-telling will play a role.

Queensland’s Plan notes that the consultations for the Path to Treaty in Queensland identified truth-telling and healing as a crucial foundation, and that it has established a Treaty Advancement Committee to provide independent advice to the government on options to implement the recommendations of the Eminent Panel (Queensland Government 2021, p. 4).

South Australia’s Plan simply states that it supports truth-telling “to enable reconciliation and active, ongoing healing” in the context of government organisations identifying their history with Aboriginal peoples (Government of South Australia 2021, p. 27).

Western Australia’s Plan states that the government is developing a Strategy for Aboriginal Affairs which reflects the priorities expressed by Aboriginal peoples and requires each government agency “to contribute to truth-telling and incorporate it into their business” (Government of Western Australia 2021, p. 40).

While the NSW government has developed a comprehensive OCHRE programme (Opportunity, Choice, Healing, Responsibility, Empowerment) to support Aboriginal self-determination and priorities by progressively transferring control of programme design and delivery to Aboriginal communities, its Plan remains conspicuously silent on treaty and truth-telling (NSW Government 2021).

Comparisons with Canada and New Zealand

Part 1 of this paper noted that the four common-law CANZUS countries (Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the USA) originally voted against the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), but to varying degrees have subsequently reversed that position (Wensing 2021b, p. 102). However, notably at the national level, Australia’s level of compliance with UNDRIP’s principles and standards remains poor (Wensing 2021b, pp. 109–112), especially compared with Canada and New Zealand.

Canada

Canada has a long history of treaty-making. There are 70 historic treaties forming the basis of the relationship between the Crown and 364 First Nations, representing over 60,000 Indigenous people (Government of Canada undated). The modern treaty era began following the Supreme Court of Canada’s 1973 decision in Calder et al. v. Attorney-General of British Columbia, in which the Court recognised Aboriginal rights for the first time. Since then, 25 more treaties have been signed and treaty-making continues to this day (Government of Canada, undated). However, treaties in Canada have not been without their difficulties with respect to reconciling sovereignties (Hoehn 2012, pp. 2, 35).

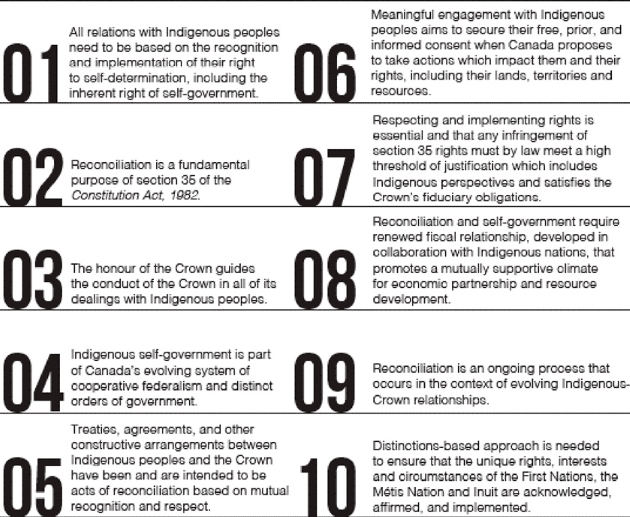

The Canadian government announced its support in principle for UNDRIP in 2010, and in 2016 re-endorsed the Declaration without qualification and committed to its full and effective implementation (Government of Canada 2016). Recognising that implementation requires transformative change, in 2018 it adopted a set of Principles respecting the government’s relationship with Indigenous peoples (Figure 5). The principles “reflect a commitment to good faith, the rule of law, democracy, equality, non-discrimination, and respect for human rights” and will guide the work required to fulfil the government’s commitment to renewed nation-to-nation, government-to-government, and Inuit-Crown relationships (Government of Canada 2018).

Figure 5. Principles for the Canadian government’s relationship with Indigenous peoples

Source: Government of Canada (2018)

In June 2021, the Canadian Parliament passed ‘An Act Respecting the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples’. The purposes of the Act are to:

(a) affirm the Declaration as a universal international human rights instrument with application in Canadian law; and

(b) provide a framework for the Government of Canada’s implementation of the Declaration.

The Act outlines measures to ensure that Canadian laws are consistent with UNDRIP. This specifically includes working with First Nations to set priorities and to identify laws that need to be changed. The Act states that the federal government “must… prepare and implement an action plan to achieve the purposes of the Declaration”. It also provides that the action plan must be created in ‘consultation and cooperation’ with Indigenous peoples, and requires regular reporting on the progress being made, including published reports to parliament (Assembly of First Nations, undated).

In 2019, the province of British Columbia passed its own statute to implement UNDRIP, the first sub-national jurisdiction in Canada to do so. The Act’s objectives are to affirm the application of Declaration to the laws of British Columbia, to contribute to the implementation of the Declaration, and to support the affirmation of, and develop relationships with, Indigenous governing bodies (British Columbia 2019). Unlike the Canadian statute, the British Columbia Act also includes provisions authorising the provincial government to enter into agreements with Indigenous governing bodies for joint decision-making or consent with respect to the use of statutory powers (Library of the Parliament of Canada 2021, p. 5).

Under the Act, the provincial government must develop an action plan in consultation and cooperation with Indigenous peoples. A draft has been prepared for consultation, outlining proposed actions to be taken in cooperation with Indigenous peoples between 2021 and 2026, with progress to be reviewed and publicly reported annually. Actions are grouped under the four themes of self-determination and inherent right of self-government; title and rights of Indigenous peoples; ending Indigenous-specific racism and discrimination; and social, cultural and economic well-being (British Columbia 2021).

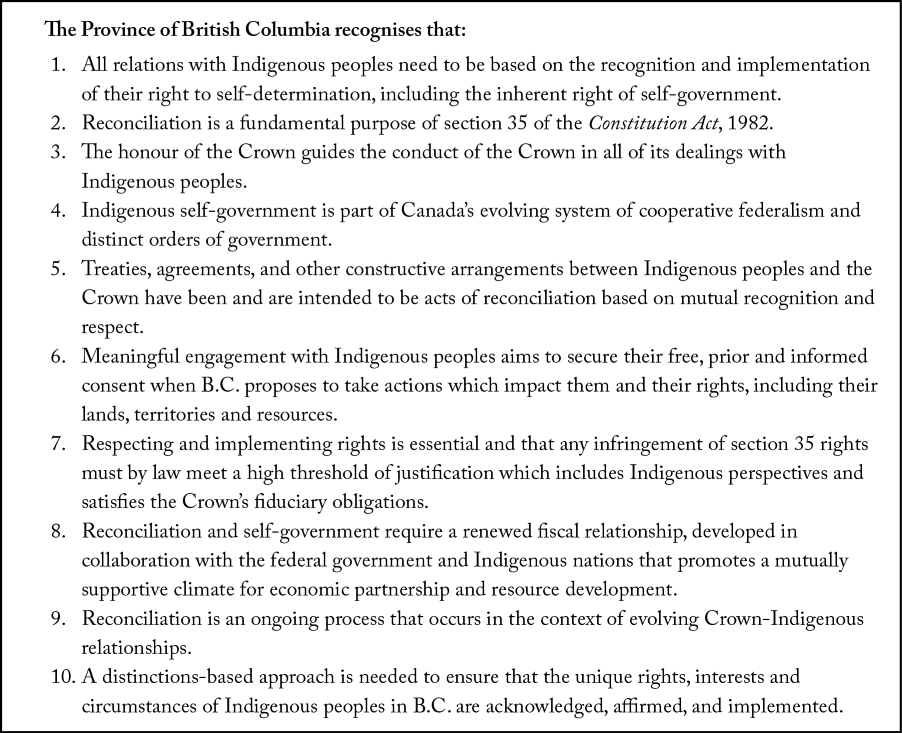

British Columbia has also developed ten draft principles, modelled on those introduced by the federal government in 2017, which provide high-level guidance on how provincial representatives engage with Indigenous peoples (Figure 6). As in Australia, it is notable that a sub-national government is playing a leadership role, albeit within a much more supportive national framework.

Figure 6. Draft Principles for British Columbia’s relationship with Indigenous peoples

Source: British Columbia (2018)

New Zealand

The Treaty of Waitangi, signed in 1840 by Māori Chiefs and representatives of the British Crown, continues to provide a framework for the relationship between Māori and the New Zealand government (Jones 2016, pp.7, 42). While there is some contention about differences between the Māori and English versions of the Treaty, the essential element is that “the Crown has the authority to establish some form of government in New Zealand and that the Māori property and other rights and the authority of the chiefs is protected” (Jones 2016, p. 7). Palmer (2008) maintains that the Treaty did not transfer sovereignty from the Māori to the British Crown.

The Treaty is not enforceable by the courts in New Zealand (Office of Treaty Settlements 2018, p. 6), but its principles have been given some legal effect by reference in specific legislation, such as s.8 of the Resource Management Act 1991 (New Zealand Government 1991). Professor Hirini Matunga from Lincoln University17 asserts that while these provisions have been laudable, they fail the Treaty responsiveness test because Māori planning, management and decision-making were not included in the Act in the first place.

When New Zealand endorsed UNDRIP in 2010, it did so “without a substantive commitment to the core rights it affirms in that process” (Te Aho 2020, p. 39). It was not until March 2019 that the New Zealand Attorney-General and Te Minita Whanaketanga Māori directed the Crown Law Office and Te Puni Kōkiri to start work on a Declaration Plan. A stocktake on the government’s response to the Declaration until that point identified low public sector understanding of the Declaration and of its connection with the Treaty of Waitangi.

In August 2019, the Declaration Working Group was established to provide advice on the form and content of a Declaration Plan and engagement process. It reported to government in November 2019, outlining a vision for realising the Declaration by 2040 – in particular advancing Māori self-determination/rangatiratanga, and ideas for constitutional transformation (New Zealand Government 2019). The government subsequently agreed to a two-step process including targeted engagement with key iwi and significant Māori organisations, as well as wider public consultations, with the intention of approving a Declaration Plan by the end of 2022 (New Zealand Government 2021). However, Te Aho (2020, p. 35) has expressed concerns that New Zealand’s actions can be characterised as “rights ritualism”. This was because when the government endorsed UNDRIP in 2010, it “made it clear that implementation of the declaration would occur within existing constitutional and legal parameters” (Te Aho 2020, p. 35).

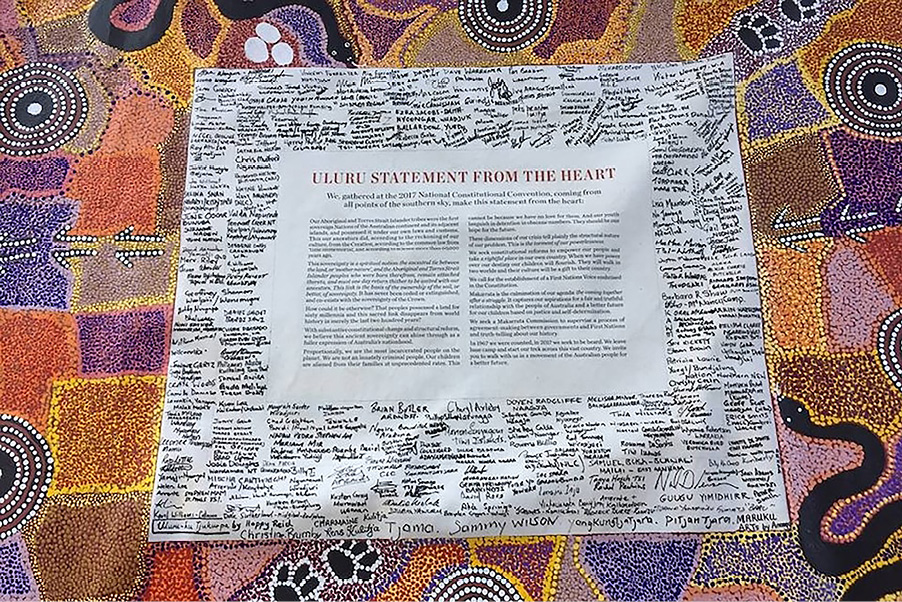

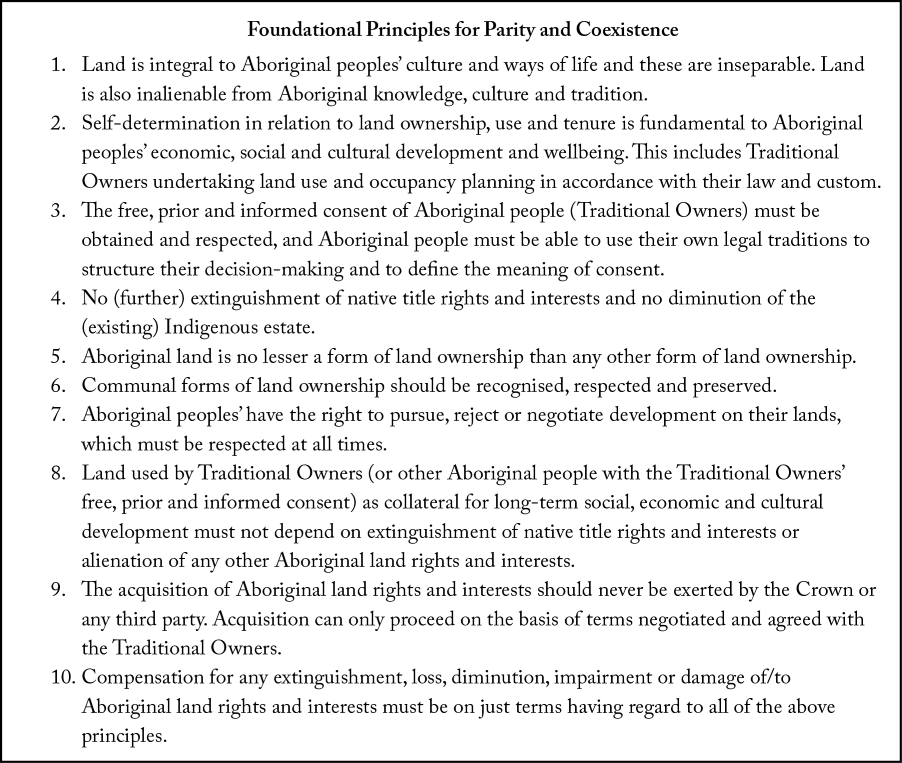

Foundational principles for parity and coexistence

Calls for a treaty in Australia are not new. Issues of prior ownership, continued occupation and sovereignty, and affirming their human rights and freedoms, including land rights, have been raised repeatedly since the 1930s in declarations by First Nations peoples (Table 1). And over the last 12 years, various key organisations in Australia have made clear statements of expectations or principles about Indigenous land reforms, each developed either directly by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples themselves or in close consultation with them (Wensing 2016, pp. 3–9).

Source: Wensing (2019, pp. 104–106)

Several key messages can be drawn from these statements:

• Land is central to First Nations peoples’ culture and way of life and these are inseparable;

• First Nations peoples’ right to pursue, reject or negotiate development on their lands should be respected, especially with respect to local decision-making;

• First Nations peoples want to be able to use their land as collateral for long-term social, economic and cultural development;

• There should be no extinguishment of their rights and interests or any diminution of the Indigenous estate; and

• International human rights standards are applicable, in particular the rights to self-determination and to free, prior and informed consent on matters affecting their interests, including their ancestral lands and waters (Wensing 2016, p. 6; 2019, p. 271).

The statements appear to reflect growing concerns by First Nations peoples that schemes of statutory land rights and the native title system are neither recognising their sovereignty nor providing appropriate self-determination over their land rights and interests. The current arrangements mostly fail to deliver tangible outcomes in terms of restoring, protecting and exercising Indigenous peoples’ unique knowledge, culture and world values, and to improve well-being on their terms (Wensing 2019, p. 273).

Drawing on UNDRIP, the declarations in Table 1 and the points listed above, Figure 7 proposes ten ‘Foundational Principles’ as the basis for parity and coexistence between Indigenous and Western forms of land ownership, use and tenure in Australia (Wensing 2019, pp. 274–287). The principles express important values that indicate how Indigenous forms can be regarded as being at least equal to their Western counterparts, if not superior (Wensing and Small 2012). All ten are inter-related and must be applied equally applied for the two systems to operate effectively side by side.

Figure 7. Foundational Principles for Parity and Coexistence

Source: Wensing (2019, p. 274)

Conclusion

The Uluru Statement will live on because it not only sets out the grievances of First Nations peoples that require Australia’s attention, but also includes three key mechanisms for addressing those grievances: Voice, Treaty, Truth.

Commitment to real constitutional reform in Australia continues to wax and wane. As Lino (2018, p. 68) observes, minimalist proposals for recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia’s Constitution have been about “including a symbolic, unenforceable reference”, this being “the model promoted by the Howard Government18 and now enshrined within all six State Constitutions”. On the other hand, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have become far more assertive in their bid for substantive recognition, seeking removal of remnants of racism from the Constitution together with amendments that safeguard Indigenous rights and go beyond mere symbolic gestures to “more expansive projects of reconciliation, rights, sovereignty, treaty and postcolonial reckoning” (Lino 2018, p. 68).

There are many different ways of addressing the longstanding lack of recognition of First Peoples’ prior ownership and occupation of the lands that comprise Australia, but history shows that such measures cannot be imposed, they must be negotiated (Hoehn 2016, p. 125). The challenge is for any negotiations over land rights to be based on parity between the parties, mutual respect and justice, rather than exploitation and domination by one or other party.

Four (possibly five) states and territories have now formally commenced efforts to negotiate treaties. Three have indicated they are willing to consider treaties at the Aboriginal language group or regional level, based on affiliations between clans or native title determinations that have established connections to Country. This is the path that South Australia was pursuing before the change in government from Labor to Liberal in 2018 when the process was ‘paused’ (Government of South Australia 2013).

What stands out here is that Australia’s sub-national jurisdictions have taken on treaty developments without the involvement of the Commonwealth. The COVID-19 crisis and the need to address climate change have revealed the potential for states and territories once again to play a more assertive role in the federation, and to work together without a Commonwealth presence. This may well continue and expand into other policy areas.

The sub-national approaches to treaty and truth telling are bold attempts to respond to calls by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples for voice, treaty, and truth, and are consistent with the principles embedded in UNDRIP. At this point, it is still too early to determine whether the states and territories can accomplish what really needs to be achieved: a resolution of past wrongs, and a path to a better future for Indigenous peoples that respects their rights and interests and their law and culture as Australia’s First Nations. The crucial test each jurisdiction will have to pass is whether they successfully adopt and apply the three critical ingredients of voice, treaty and truth-telling as the foundation for their negotiations.

In addition, negotiations between sub-national governments and First Nations peoples need to reflect and embrace the interests and potential contributions of the more than 500 local governments established and supervised under state and Northern Territory laws. Across the Northern Territory, northern Queensland and the Torres Strait a substantial number of those local governments are primarily Indigenous. Detailed discussion of local government issues is beyond the scope of this paper, but it is clear that the sector will need to play – and is already playing – an expanded role in advancing social justice for Indigenous Australians (Wensing 2021a).

Because of their place-based responsibilities, local governments are often seen as being ‘closest to the people’: they are therefore in a unique position to implement some structural and systemic reforms that central government cannot, and to reconfigure relationships at a local and regional scale. This can include meaningful consultations on matters that affect Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, ensuring their representation in all relevant forums and governance bodies, and entering into place-based protocols and agreements on matters of mutual concern. Such initiatives can be particularly valuable in metropolitan areas and regional cities where most of Australia’s Indigenous peoples live.

There is also scope for a ‘leadership from below’ or ‘building block’ role for local and regional action led by local government. Many municipalities have a solid track record of reaching agreements under the reconciliation agenda and native title legislation. With respect to truth-telling, local governments are often rich repositories of histories which can be re-told in partnership with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, especially with native title holder groups where they have been determined or have active claims in train, thus rebuilding relationships. This could be a really important starting point for regional treaties. The most significant challenge for local governments is understanding the opportunities and becoming involved from the outset and for the long term (Wensing 2021c, p. 24).

There is much at stake in all these sub-national and local and regional processes, especially given continuing inaction, or a lack of real commitment and effort, by the Australian government. If any of the initiatives discussed in this paper fail, it may well be some decades before they can be revisited. Ultimately, Australia must come to terms with how European settlement failed to seek the consent of the First Nations peoples who have lived here for so many thousands of years. Unequivocal respect for their human rights, including land rights, is long overdue.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

Aboriginal Victoria (2019) “To be heard and for the words to have actions” Traditional Owner voices: improving government relationships and supporting strong foundations. Available at: https://www.content.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019-11/Traditional-owner-voices-improving-government-relationships-and-supporting-strong-foundations.pdf

Assembly of First Nations (undated) Backgrounder: Bill C-15: An Act respecting the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Available at: https://www.afn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/C-15_Backgrounder_ENG.pdf

Australian Capital Territory (ACT) Government (2001) Agreement between the Australian Capital Territory and ACT Native Title Claim Groups. (Copy held on file by the author).

Australian Capital Territory (ACT) Government (2021a) Australian Capital Territory Budget 2021–22, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander budget statement. October. Available at: https://www.treasury.act.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/1870284/2021-22-Aboriginal-and-Torres-Strait-Islander-Budget-Statement.pdf

Australian Capital Territory (ACT) Government (2021b) ACT government closing the gap: jurisdictional implementation plan. Available at: https://www.communityservices.act.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/1815451/ACT-National-Closing-the-Gap-Agreement-Implementation-Plan.pdf

Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) (1988) Barunga Statement. Available at: https://aiatsis.gov.au/explore/barunga-statement

Barnett, C. (2015) (2015) Premier’s statement to Parliament – 14 October 2015. Extract from Hansard, WA Legislative Assembly. pp. 7313b–7314a.

Barr. A. and Rattenbury, S. (2020) Parliamentary and governing agreement. 10th Legislative Assembly for the Australian Capital Territory. Available at: https://www.cmtedd.act.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/1654077/Parliamentary-Agreement-for-the-10th-Legislative-Assembly.pdf

Brigg, M. and Murphy, L. (2011) Beyond captives and captors: settler-indigenous governance for the 21st century. (pp. 1-31). In Maddison, S. and Brigg, M. (eds.) Unsettling the settler state. creativity and resistance in indigenous settler-state governance, (Chapter 1). Leichhardt, Sydney: The Federation Press.

British Columbia (2018) Draft principles that guide the Province of British Columbia’s relationship with Indigenous peoples. Available at: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/careers/about-the-bc-public-service/diversity-inclusion-respect/draft_principles.pdf

British Columbia (2019) Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act, S.B.C. 2019, c. 44 (CanLII). Victoria, British Columbia, Canada: Queen's Printer.

British Columbia (2021) Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous peoples Act, draft action plan. Draft for consultation. Available at: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/government/ministries-organizations/ministries/indigenous-relations-reconciliation/declaration_act_action_plan_for_consultation.pdf

Coalition of Peaks (2020) A report on engagement with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to inform a new national agreement on closing the gap. Available at: https://coalitionofpeaks.org.au/download/2019-community-engagements/

Commonwealth of Australia (1901) Australian Constitution Act 1901 (Cth). Melbourne: Commonwealth of Australia.

Commonwealth of Australia (1976) Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth). Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

Commonwealth of Australia (1993) Native Title Act 1993 (Cth). Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

Commonwealth of Australia (2021) Commonwealth closing the gap implementation plan. July. Available at: https://www.niaa.gov.au/sites/default/files/publications/commonwealth-implementation-plan-130821.pdf

Davis, M. (2017) Self-determination and the right to be heard. In: Morris, S. (ed.) A rightful place. a road map to recognition, (pp. 119-146). Carlton, Vic: Black Inc.

Federation of Victorian Traditional Owner Corporations (FVTOC) (2021) A framework for Traditional Owner treaties: lessons from the Settlement Act. Discussion Paper No. 5. Available at: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5b337bd52714e5a3a3f671e2/t/617a299c3ebd5b1034ae9b05/1635396004539/1376_FVTOC+Treaty+Paper+%235.%C6%92+final.pdf

First Peoples’ Assembly of Victoria (FPAV) (2019) Constitution of the First Peoples Assembly of Victoria Limited. Available at: http://firstpeoplesvic.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/First-Peoples-Assembly-of-Victoria-Constitution-14-November-2019.pdf

First Peoples’ Assembly of Victoria (FPAV) (undated) Governance and decision making map. Available at: https://www.firstpeoplesvic.org/download/governance-and-decision-making-map/

Gover, K. (2020) Treaties and the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. The significance of Article 37. In UNDRIP implementation: comparative approaches, indigenous voices from CANZUS. Special Report, (pp. 77–86). Centre for International Governance Innovation. Available at: https://www.cigionline.org/static/documents/documents/UNDRIPIII_web_mar27.pdf

Government of Canada (2016) Canada becomes a full supporter of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. News Release, 10 May 2016. Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/indigenous-northern-affairs/news/2016/05/canada-becomes-a-full-supporter-of-the-united-nations-declaration-on-the-rights-of-indigenous-peoples.html

Government of Canada (2018) Principles respecting the government of Canada's relationship with Indigenous peoples. Available at: https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/csj-sjc/principles.pdf

Government of Canada (2021) An Act respecting the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, statutes of Canada 2021. Assented to 21 June. Ottowa, Canada: Published under authority of the Speaker of the House of Commons.

Government of Canada (undated) Treaties and agreements. Available at: https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1100100028574/1529354437231

Government of South Australia (2013) Aboriginal regional authorities. A regional approach to governance in SA, Phase 1, Summary Report. SA: Department of the Premier and Cabinet.

Government of South Australia (2021) South Australia’s implementation plan for the national agreement on Closing the Gap. Available at: https://www.dpc.sa.gov.au/responsibilities/aboriginal-affairs-and-reconciliation/closing-the-gap/south-australias-implementation-plan/South-Australias-Implementation-Plan-for-Closing-the-Gap.pdf

Government of Tasmania (2021) Closing the Gap Tasmanian implementation plan 2021– 023. Available at: https://www.communities.tas.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0028/180478/Closing-the-Gap-Tasmanian-Implementation-Plan-August-2021.pdf

Government of Victoria and the Co-Chairs of the First Peoples Assembly of Victoria (FPAV) (2021) Joint statement on Victoria’s truth and justice process. 9 March. Available at: https://www.firstpeoplesvic.org/media/joint-statement-on-victorias-truth-and-justice-process-9-march-2021/

Government of Victoria (2010) Traditional Owner Settlement Act 2010 (Vic). Melbourne: Government of Victoria.

Government of Victoria (2014) Inquiries Act 2014 (Vic). Melbourne: Government of Victoria.

Government of Victoria (2016) Victorian Government Aboriginal Affairs Report. Available at: https://www.firstpeoplesrelations.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019-09/Victorian_Government_Aboriginal_Affairs_Report_2016.pdf

Government of Victoria (2018) Advancing the Treaty Process with Aboriginal Victorians Act 2018 (Vic). Melbourne: Government of Victoria.

Government of Victoria (2019) Advancing the Victorian treaty process annual report and plan 2018-19. Available at: https://www.firstpeoplesrelations.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019-09/Advancing-the-Victorian-Treaty-Process-Annual-Report-and-Plan-2018-19.pdf

Government of Western Australia (2016) Noongar (Koorah, Nitja, Boordahwan) (Past, Present, Future) Recognition Act 2016 (WA). Perth: Government of Western Australia.

Government of Western Australia (2021) Closing the Gap jurisdictional implementation plan Western Australia. Available at: https://www.wa.gov.au/government/publications/closing-the-gap-was-implementation-plan

Graham, M. and Petrie, A. (2018) Advancing the treaty process with Aboriginal Victorians Bill 2018. No. 5. May 2018, Treaty Series. Melbourne: Parliamentary Library & Information Service, Department of Parliamentary Services, Parliament of Victoria.

Gutwein, P. Premier of Tasmania (2021) Official opening of the 50th Parliament of Tasmania. 22 June. Available at: https://www.premier.tas.gov.au/site_resources_2015/additional_releases/official_opening_of_the_50th_parliament_of_tasmania/official_opening_of_the_50th_parliament_of_tasmania

Hiatt, L.R. (1987) Treaty, compact, Makaratta …? Oceania, 58 (2), 140–144. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1834-4461.1987.tb02266.x

High Court of Australia (HCA) (1992) Mabo v the State of Queensland (No. 2). (1992) 175 Commonwealth Law Reports 1.

High Court of Australia (HCA) (1996) Wik Peoples v State of Queensland. (Pastoral lease case) [1966] HCA 40, (1996) 187 Commonwealth Law Reports 1.

High Court of Australia (2002) Members of the Yorta Aboriginal Community v Victoria. (2002) HCA 58 and 214 Commonwealth Law Reports 422.

Hobbs, H. (2021) Victoria’s truth-telling commission: to move forward, we need to answer for the legacies of colonisation. The Conversation, 9 March.

Hobbs, H. and Williams, G. (2019) Treaty-making in the Australian federation. Melbourne University Law Review, 43 (1), 178–232.

Hoehn, F. (2012) Reconciling sovereignties. Aboriginal nations and Canada. Saskatoon: Native Law centre, University of Saskatchewan.

Hoehn, F. (2016) Back to the future – reconciliation and indigenous sovereignty after Tsilhqot’In’. University of New Brunswick Law Journal, 67, 109–145.

Howitt, R. (2006) Scales of coexistence: tackling the tension between legal and cultural landscapes in post-Mabo Australia. Macquarie Law Journal, 6, 49–64.

Howitt, R. (2019) Unsettling the taken (-for-granted). Progress in Human Geography, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132518823962

Howitt, R. and Lunkapis, G.J. (2010) Coexistence: planning and the challenge of indigenous rights. In: Hillier, J. and Healey, P. (eds.) The Ashgate research companion to planning theory: conceptual challenges for spatial planning, (pp. 109–133). Farnham, UK: Ashgate Publishing Ltd.

Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (HREOC) (1997) Bringing them home: National Inquiry into the separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children from their families. Final report. HREOC, Sydney. Available at: https://www.humanrights.gov.au/publications/bringing-them-home-report-1997

Hutchins, the Hon Natalie (2016) Aboriginal Victorians talk treaty. Media Release, Monday, 18 July.

Jackson McDonald Lawyers (2016) Noongar governance structure manual. Available at: https://www.dpc.wa.gov.au/swnts/Documents/Noongar%20Governance%20Structure%20Manual%2020-12-2016-JacMac.pdf

Jones, C. (2016) New treaty new tradition. Reconciling New Zealand and Māori law. Wellington: Victoria University Press.

Library of Parliament of Canada (2021) Legislative Summary Bill C-15: An Act Respecting the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Publication No. 43-2-C-15-E. Parliamentary Information, Education and Research Services. Available at: https://lop.parl.ca/staticfiles/PublicWebsite/Home/ResearchPublications/LegislativeSummaries/PDF/43-2/43-2-c15-e.pdf

Lino, D. (2018) Constitutional recognition. First Peoples and the Australian settler state. Leichardt: The Federation Press.

Maddison, S. and Wandin, D. (2019) So much at stake: forging a treaty with authority and respect. Commentary. Australian Book Review, No. 413, August. Available at: https://www.australianbookreview.com.au/abr-online/archive/2019/371-august-2019-no-413/5658-so-much-at-stake-forging-a-treaty-with-authority-and-respect-by-sarah-maddison-and-dale-wandin

National Indigenous Australians Agency (NIAA) (2020) National agreement on Closing the Gap. July 2020. Available at: https://www.closingthegap.gov.au/national-agreement-closing-gap-glance

New South Wales Government (2021) NSW implementation plan for Closing the Gap. Available at: https://www.aboriginalaffairs.nsw.gov.au/closingthegap/nsw-implementation-plan/2021-22-implementation-plan/NSW-Implementation-Plan-2021-22.pdf

New Zealand Government (1991) Resource Management Act 1991. Wellington: New Zealand Government.

New Zealand Government (2019) HE PUAPUA, Report of the Working Group on a plan to realise the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Available at: https://www.tpk.govt.nz/en/a-matou-mohiotanga/cabinet-papers

New Zealand Government (2021) UNDRIP: next steps for a declaration plan. Cabinet Social Wellbeing Committee, Minute of Decision, 21 June. Available at: https://www.tpk.govt.nz/en/a-matou-mohiotanga/cabinet-papers

Northern Territory (NT) Government (2019a) Aboriginal Affairs Sub-Committee of Cabinet. Department of the Chief Minister, NT Government. (Held on file by the author.)

Northern Territory (NT) Government (2019b) Treaty in the NT government. Department of the Chief Minister, NT Government. (Held on file by the author.)

NT Government and Northern, Central, Anindilyakwa and Tiwi Land Councils (2018) The Barunga Agreement. 8 June 2018, A Memorandum of Understanding to provide for the development of a framework for negotiating a Treaty with the First Nations of the Northern Territory of Australia. Available at: https://dcm.nt.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/514272/barunga-muo-treaty.pdf

Northern Territory Treaty Commission (2020a) Interim report of the Northern Territory Treaty Commissioner, Stage One. March. Available at: https://treatynt.com.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0012/881697/nttc-interim-report.pdf

Northern Territory Treaty Commission (2020b) Treaty discussion paper. 30 June. Available at: https://treatynt.com.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/906398/treaty-discussion-paper.pdf

Northern Territory Treaty Commission (2021) Towards truth telling. 12 February. Available at: https://treatynt.com.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/982544/towards-truth-telling.pdf

Office of Treaty Settlements (2018) Healing the past, building a future. A guide to treaty of Waitangi claims and negotiations with the Crown. Wellington, New Zealand. Available at: https://www.govt.nz/assets/Documents/OTS/The-Red-Book/The-Red-Book.pdf

Palaszczuk, A. the Hon (2019) Historic signing of ‘tracks to treaty’ commitment. The Premier, Joint Media Statement (with other Queensland Government Ministers). 14 July 2019. (Held on file by the author.)

Palmer, M. (2008) The treaty of Waitangi in New Zealand’s law and constitution. Wellington: Victoria University Press.

Porter, L. and Barry, J. (2016) Planning for coexistence? Recognizing Indigenous rights through land-use planning in Canada and Australia. Oxon, UK: Routledge.

Queensland Government (2019) Human Rights Act 2019 (Qld). Brisbane: Queensland Government.

Queensland Government (2020) Treaty statement of commitment and response to recommendations of the Eminent Panel. August. Available at: https://www.dsdsatsip.qld.gov.au/resources/dsdsatsip/work/atsip/reform-tracks-treaty/path-treaty/treaty-statement-commitment-august-2020.pdf

Queensland Government (2021) Queensland’s closing the gap implementation plan. Available at: https://www.dsdsatsip.qld.gov.au/resources/dsdsatsip/work/atsip/reform-tracks-treaty/closing-gap/closing-gap-implementation-plan.pdf

Referendum Council (2017a) Final report of the Referendum Council and Uluru Statement from the Heart. Available at: https://www.referendumcouncil.org.au/sites/default/files/report_attachments/Referendum_Council_Final_Report.pdf

Referendum Council (2017b) Uluru Statement from the Heart, Statement on the First Nations National Constitutional Convention. 26 May 2017. Available at: https://www.referendumcouncil.org.au/sites/default/files/2017-05/Uluru_Statement_From_The_Heart_0.PDF

Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody (RCADC) (1991) Final reports – national and regional. Available at: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/other/IndigLRes/rciadic/

Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse (RCIRCSA) (2017) Final report. Available at: https://www.childabuseroyalcommission.gov.au/final-report

State of Queensland (2020a) Report from the Treaty Working Group on Queensland’s path to treaty. February. Available at: https://www.dsdsatsip.qld.gov.au/resources/dsdsatsip/work/atsip/reform-tracks-treaty/path-treaty/treaty-working-group-report-2020.pdf

State of Queensland (2020b) Advice and recommendations from the Eminent Panel on Queensland’s path to treaty. February. Available at: https://www.dsdsatsip.qld.gov.au/resources/dsdsatsip/work/atsip/reform-tracks-treaty/path-treaty/treaty-eminent-panel-february-2020.pdf

Strelein, L.M. (2009) Compromised jurisprudence: Native title cases since Mabo. 2nd edition. Canberra Aboriginal Studies Press.

Supreme Court of Canada (1973) Calder et al. v. Attorney-General of British Columbia. [1973] SCR 313.

Te Aho, F. (2020) Treaty settlements, the UN Declaration and Rights Ritualism in Aotearoa New Zealand. In: UNDRIP implementation: comparative approaches, Indigenous voices from CANZUS. Special Report, (pp. 33–40). Centre for International Governance Innovation. Available at: https://www.cigionline.org/static/documents/documents/UNDRIPIII_web_mar27.pdf

Thomas, R. (2017) Talking treaty. Summary of engagements and next steps. Treaty Commissioner. (Held on file by the author.)

Turnbull, the Hon M., Brandis, G. and Scullion, N. (2017) Response to Referendum Council’s report on constitutional recognition. Media Release 26 October 2017. Available at: https://www.nigelscullion.com/media+hub/Response+to+Referendum+Council%E2%80%99s+report+on+Constitutional+Recognition [Accessed 15 November 2017].

United Nations (2007) Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. General Assembly Resolution 61/295. Available at: http://legal.un.org/avl/pdf/ha/ga_61-295/ga_61-295_ph_e.pdf

United Nations (2012) Right to the truth. Resolution adopted by the Human Rights Council. A/HRC/RES/21/7. Available at https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/RESOLUTION/GEN/G12/173/61/PDF/G1217361.pdf?OpenElement

United Nations (2013) 68/165. Right to the truth. Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 18 December 2013. A/RES/68/165. Available at: https://undocs.org/pdf?symbol=en/A/RES/68/165

Victorian Parliamentary Library and Information Service (2018) Advancing the treaty process with Aboriginal Victorians Bill 2018. Treaty Series No. 5, May 2018. Parliamentary Library & Information Service, Department of Parliamentary Services, Parliament of Victoria. Available at: https://www.parliament.vic.gov.au/publications/research-papers/download/36-research-papers/13861-advancing-the-treaty-process-with-aboriginal-victorians-bill-2018 or https://www.parliament.vic.gov.au/publications/research-papers/send/36-research-papers/13861-advancing-the-treaty-process-with-aboriginal-victorians-bill-2018

Victorian Treaty Advancement Commission (2018) Pathway to treaty. Melbourne: Victorian Government.

Walker, B. (2015) The legal shortcomings of native title. In: Brennan, S., Davis, M., Edgeworth, B. and Terrill, L. (eds.) From Mabo to Akiba: a vehicle for change and empowerment? (pp. 14–28). Annandale, NSW: The Federation Press.

Walker. B. (2020) Legal context of a Northern Territory treaty – opinion. Unpublished paper. (Cited with permission of Professor Mick Dodson, NT Treaty Commissioner.)

Walquist, C. (2018) South Australia halts Indigenous treaty talks as premier says he has ‘other priorities’. The Guardian, 30 April. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2018/apr/30/south-australia-halts-indigenous-treaty-talks-as-premier-says-he-has-other-priorities

Watson, I. (2007) Settled and unsettled spaces: are we free to roam? In: Moreton-Robinson, A. (ed.) Sovereign subjects. Indigenous sovereignty matters, (pp. 15–32). Sydney: Allen & Unwin. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003117353-3

Wensing, E. (2016) The Commonwealth’s Indigenous land tenure reform agenda: whose aspirations, and for what outcomes? Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Research Publications. Available at: https://aiatsis.gov.au/sites/default/files/research_pub/the-commonwealths-indigenous-land-tenure-reform_2.pdf

Wensing, E. (2019) Land justice for indigenous Australians: how can two systems of land ownership, use and tenure coexist with mutual respect based on equity and justice? PhD Thesis, The Australian National University. DOI: 10.25911/5c9208e0d898a. http://hdl.handle.net/1885/157200

Wensing, E. (2021a) Unfinished business truth-telling about Aboriginal land rights and native title in the ACT. Discussion Paper 1053. The Australia institute, March 2021. DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.16608.61440. Available at: https://australiainstitute.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/P1053-Unfinished-Business-in-the-ACT-Wensing-2021.pdf

Wensing, E. (2021b) Indigenous peoples’ human rights, self-determination and local governance – Part 1. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, (24), 98–123. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi24.7779

Wensing, E. (2021c) Closing the Gap: roles for local government. SGS Economics and Planning and LGiU Australia. Available at: https://www.sgsep.com.au/assets/main/SGS-Economics-and-Planning_Closing-the-Gap.pdf

Wensing, E. and Small, G. (2012) A just accommodation of customary land rights in land use planning systems. Paper presented to the 10th International Urban Planning and Environment Association Symposium, University of Sydney, 24–27 July, pp.164–80. http://sydney.edu.au/architecture/documents/prc/UPE10/UPE10%20Proceedings.pdf

Williams, The Hon Gabrielle (2020) Delivering truth and justice for Aboriginal Victorians. Media Release, 11 July. Available at: https://www.premier.vic.gov.au/delivering-truth-and-justice-aboriginal-victorians

Wyatt, B. the Hon (2018) Joint Media Conference with the Chair of the South West Aboriginal Land and Sea Council, and the Minister for Aboriginal Affairs, WA on the Registration of the six ILUAs by the Native Title Registrar, National Native Title Tribunal, cited in The South West Native Title Settlement. News Bulletin, October 2018. (Held on file by the author.)

Wyatt, K. the Hon (2019) Walking in partnership to effect change. National Press Club Address, Canberra, 10 July. Available at: https://ministers.pmc.gov.au/wyatt/2019/national-press-club-address-walking-partnership-effect-change [Accessed: 31 July 2019].

Yoo-rrook Commission (2021a) Letters patent. Available at: https://yoorrookjusticecommission.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Letters-Patent-Yoo-rrook-Justice-Commission-signed-10-1.pdf

Yoo-rrook Commission (2021b) Letters patent summary. Available at: https://yoorrookjusticecommission.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Yoo-rrook-Letters-Patent-Summary.pdf

1 Professor Mick Dodson, Concluding Remarks at the National Centre for Indigenous Studies Research Retreat, 21 October 2016, Australian National University, Canberra. Notes of proceedings held on file by the author.

2 Personal communication with the author. See also http://kadomuir.wixsite.com/kadomuir

3 (1996) 187 Commonwealth Law Reports 1.

4 (1992) 175 Commonwealth Law Reports 1, Brennan J, pp. 30, 43.

5 Hiatt argues that perhaps ‘garma’ may have been a better choice because it means ‘getting together of minds in order to reach complete accord’.

6 The South Australia government embarked on treaty negotiations in February 2017, before the release of the Uluru Statement, as part of its commitment to building a better and stronger relationship with Aboriginal people. However, a state election in March 2018 produced a change in government from Labor to Liberal, which then ‘paused’ the treaty negotiations in favour of ‘other priorities’ on Indigenous matters (Walquist 2018; Thomas 2017).

7 While ‘Aboriginal community’ is often used to describe Aboriginal people, it is important to note that people who identify as Aboriginal Victorians cannot be seen as one entity who share a single ‘community’ (Graham and Petrie 2018, p. 10).

8 Maddison and Wandin (2019) and various free to air news reports.

9 https://www.fvtoc.com.au/treaty/discussion-papers-1?rq=Treaty%20Discussion%20paper%5C

10 Members of the Yorta Aboriginal Community v Victoria (2002) High Court of Australia 58, 214 Commonwealth Law Reports 422.

11 The Northern Land Council, the Central Land Council, the Anindilyakwa Land Council and the Tiwi Land Council are independent statutory bodies established under the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth) to express the wishes and protect the interests of traditional owners throughout the NT.

12 See also the Preamble to the Noongar (Koorah, Nitja, Boordahwan) (Past, Present, Future) Recognition Act 2016 (WA).

13 Preamble to the Land Administration (South West Native Title Settlement) Act 2016 (WA).

14 Under the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth) because claimants were required to demonstrate their traditional connection to the land in order to justify their claim.

15 The Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody (1987–1991) (RCADC 1991); Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sex Abuse (2013–2017) (RCIRCSA 2017).

16 Bringing Them Home: The National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families (1995–1997) (HREOC 1997).

17 Personal communications, 26 October 2021.

18 The conservative government in office from 1996 to 2007.