Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance

Issue 26

May 2022

RESEARCH AND EVALUATION (PEER REVIEWED)

The Implications of COVID-19 and Brexit for England’s Town Councils: Views from the Town Hall, and Beyond

Gordon Morris

Centre for Rural Policy Research, University of Exeter, and Bournemouth University, United Kingdom, g.r.morris@exeter.ac.uk

Corresponding author: Gordon Morris, Centre for Rural Policy Research, University of Exeter, and Bournemouth University, United Kingdom, g.r.morris@exeter.ac.uk

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi26.7755

Article History: Received 08/06/2021; Accepted 27/03/2022; Published 31/05/2022

Citation: Morris, G. 2022. The Implications of COVID-19 and Brexit for England’s Town Councils: Views from the Town Hall, and Beyond. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, 26, 114–138. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi26.7755

© 2022 by the author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

(CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties

to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the

material for any purpose, even commercial, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Abstract

Town and parish councils are the English government bodies closest to local people. Hierarchically, they are subordinate to both national and higher tier local governments (unitary, county and borough/district councils). Town councillors represent approximately 11,000,000 people; one-fifth of the population of England. Their mainly small towns will be affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and the United Kingdom’s departure from the European Union (‘Brexit’). To what extent is not known, but councillors will have roles to play in determining how their towns respond. This paper presents and discusses the views of 156 respondents to an online survey, some of whom were also interviewed. Councillors, town clerks, academics, and interested individuals with policy and practical experience of the sector contributed. Although respondents’ views differ (eg, as to whether town councils should have more powers), most believe they will have to do more. Indeed, they want to do more, especially in relation to planning, housing and transport. They are, however, uncertain about how to achieve their aims, given the constraints of time and resources on a mainly volunteer body, their partial dependence on higher-tier authorities, and the need for, as some strongly believe, effective monitoring of standards, performance, transparency, and accountability.

Keywords

Rural England; Market Towns; Small Country Towns; Town Councils; Local Government

Introduction

The purpose of this research1 was to explore the views of town councillors in England’s small towns about their councils’ roles in the post-COVID-19 pandemic and post-Brexit era.2 It was made clear to respondents in an introductory note that: “The project’s aim is to find out if town councils could, should, or want to take on additional roles in relation to local policy development and implementation in the post-COVID world.” In a final question, respondents were asked for their views in relation to the implications of Brexit for their council.

In summary, the majority of respondents want their councils to have a greater role in local policy development and implementation. A minority, however, have strong contrary opinions in relation to councils’ capacities and competencies. Views are tinged with scepticism and doubt that devolution on their terms will – or in the views of some, should – happen.

Background and literature review

Town councils3 are the direct, but generally less powerful, successors to England’s urban and rural district councils4 that were replaced in 1974 by larger districts and boroughs (Parr 2020, p. 6). This reorganisation was predicated on the desire for fewer, higher-calibre councillors, and a more corporate approach to government (Stevens 2006, pp. 30–31). However, from the outset there were concerns throughout England about the changes, possibly because many of the new district/borough councils “… contained several towns that anywhere else in Europe would be seen as separate communities requiring their own local authorities” (Stewart 2014, p. 838). Hierarchically, town councils are subordinate to the national government and to higher-tier local authorities (unitary,5 county and borough/district councils). They are the English government bodies closest to local people. Their councillors represent approximately 11 million people, one-fifth of England’s population.

These – mainly country – towns are the bedrock on which much of England’s governance structure has been built. Many are ancient settlements, their origins based on roles as market centres. Others grew as a consequence of industries such as milling and mining. Many are still service centres, while others, for example, are tourist destinations. They are, in the main, resilient places with their own spheres of influence (Morris 2003; Powe et al. 2007, pp. 29–31); their councils long predating today’s higher-tier authorities. Page (2002), notes that: “… local councillors – and indeed local government – have consistently remained more trusted than national politicians.” This suggests that town and parish councillors may well have an increasingly important role to play, both in getting things done locally and in providing trusted community leadership.

The current British government is committed to ‘levelling up’ Britain – ie reducing the development gaps and inequalities between different parts of the country (UK Government 2022). This is effectively the latest version of regeneration-led ‘localism’; ie devolution (DCLG 2006, 2011; Kruger 2020). It is a policy which could benefit town councils because, despite Davenport and Zaranko (2020, p. 329) suggesting that only higher-tier councils “… have some administrative capacity to manage levelling-up …”, some town councils are responsible for aspects of higher-tier roles such as planning, housing, regeneration and youth work (Local Government Chronicle 2016, 2017).

The Localism Act 2011 gave councils of all sizes considerable freedom, via the General Power of Competence (GPC),6 to do “… things that are unlike anything that a local authority – or any other public body – has done before, or may currently do” (DCLG 2011). The Local Government Association (LGA) has noted, however, that “… use of the [GPC] is limited by significant constraints set by central government” (LGA 2013a, p. 1).

The difference between these two statements explains why the GPC has been widely adopted, but not widely used. Nevertheless, according to Copus and Leach (2020),“There have … been some imaginative and effective uses of the [GPC] and such a power needs to be a major tool in responding to… crises, and in building devolution.” They also note that “… the centralised nature of our system has restrained local government by lack of funds and for the want of freedoms and powers to act without Government approval”. A report by Carr et al. (2020, p. 7) reflects this, recognising “… the challenges of uniting people in towns behind any particular vision of the future”. It recommends that town councils’ autonomy be preserved, so that they can “… implement decisions made at a combined authority7 level in the way they see fit” (p. 51).

The debate about where and how to devolve powers and responsibilities in England is long-standing (Pearce and Ellwood 2002; Owen et al. 2007; Commission for Rural Communities 2008; LGA 2019). The tendency of UK governments to talk of devolution whilst centralising control over lower tiers of government is well known (Hambleton 2017).

To take rural transport as an example, nearly 25 years ago Cullinane and Stokes (1998, p. 105) noted that provision was “ … increasingly being rationalised and centralised”. More than ten years later a report for the Commission for Rural Communities listed transport as the (rural) public’s top priority (Ipsos MORI 2010); as did the public in their responses to a UK government call for evidence in relation to the future of rural transport (Department for Transport 2021). Unsurprisingly, therefore, transport was one of the topics mentioned in the present study, conducted in 2020/21.

Centralisation remains the norm, for now at least. For example, in 2019, government ministers had the final say in allocating money to towns bidding for regeneration funds (Shearer and Shepley 2021). Similarly, according to the UK’s Local Government Chronicle trade journal, a recent White Paper about devolution appears to leave the government “… holding all the cards” (Hill 2022).

Irrespective of the above, it is recognised that some town councils will be willing and able to take on additional responsibilities,8 although, “… some counties will try to shift some … responsibilities to town … councils, with little understanding or concern for [their] desire or ability to carry them out” (Copus et al. 2020 p. 19). 9

In a wide-ranging exploration of citizen participation and engagement with town councils, Willett and Cruxon (2019, p. 325) concluded that, “… Towns … are ideally placed to reinvigorate representative democracy at a local level, but bringing these structures to fit the twenty-first century lives [sic] requires new ways of doing things.” Of potential concern for town councils is a recent study from Cornwall, which found that, post Brexit, some people do not “… imagine returning control over the local to the local level, but to a national tier of government” (Willett 2021, p. 7). However, as the last ten years have seen youth club and library closures, and the loss of shops and pubs, the need for the ‘local’ remains important at both political and individual levels (Malik 2021). Given the likely adverse impact of COVID-19 and Brexit on the UK’s finances (Nabarro 2021), there is a belief that town councils, working with community-led organisations, will have a role to play (Walker and Diamond 2020; Kruger 2020; Treadwell et al. 2021).

Interestingly, in response to Treadwell et al.’s report, the LGA expressed their “…concerns over the ‘organisation, planning and training’ of parish and town councillors, as well as a lack of diversity in their makeup and a democratic deficit in that one third of their members are co-opted rather than elected onto councils” (Hill 2021, p. 1). As the LGA represents higher-tier local authorities, it is likely that the concerns expressed, whilst valid, also have a political dimension to them.

Methodology

Research data was gathered via two online surveys10– primarily of councillors, but also of clerks, academics and other interested professionals.11 Telephone interviews were held with 15 participants who volunteered to be interviewed.12

The following steps were taken between August 2020 and February 2021:

1. a pilot online questionnaire, and three subsequent telephone interviews

2. the main questionnaire, developed from the pilot questionnaire

3. twelve further telephone interviews (ten councillors, two officers).

The questionnaires comprised:

• limited-choice multiple-answer questions (eg yes/no, more/less, selection lists), with free-text options available; and

• broader, wide-ranging questions designed to encourage free-text contributions.

The two surveys were combined for analysis.

The towns contacted for the research have populations between 2,000 and 34,000 and are well distributed geographically.13 The locations of the town councils approached are illustrated in Figure 1. Responses were received from the town councils identified by the blue pins. Councils identified by red pins were asked to participate, but did not.

Figure 1. Participating (blue) and non-participating (red) councils

In all, 1,484 emails were sent to as many individual councillors as were contactable by that means, plus each council’s clerk, in 133 towns.14 Responses were received from 78 councils. A total of 156 people contributed, including some non-council-affiliated respondents, and respondents to the pilot survey. This equates to a 10.5% response rate overall. Although a relatively low return, the number of contributors and their varied backgrounds, beliefs and experience was, as discussed next, sufficient for the purposes of the research.

Respondents’ roles and affiliations

Respondents’ roles and affiliations are summarised in Tables 1 and 2. Although 92 of the councillors are town councillors only, a further 31 also sit on other local and public authorities. The insights of ‘non-council’ respondents, all of whom have studied and/or worked in, or with, local/central government, offered further valuable perspectives and have broader contextual relevance.

*Although correctly self-described as parish councillors, they represent towns with populations between 4,000 and 16,000.

The majority of participating councillors stated that they are independent of all political parties (Table 2). However, although most town councils are not party-political (LGA 2018, p. 5), the right-of-centre Conservative party’s dominance in those that are (LGA 2013b) is consistent with the historical conflation of English ‘rural’ culture and conservatism (Woods 2005, p. 88).

The respondents’ views in relation to powers, policies, democracy and resources are analysed and summarised in the next section. Following this, their views concerning the things their councils might have to do in the aftermath of COVID-19, and their thoughts about the possible effects of Brexit on their towns, are presented and discussed.

Study findings

Respondents addressed the following questions, specifically in relation to the post-pandemic world:

• Should town councils have more powers in relation to policy development and implementation?

• Which policies are they well placed to develop and implement, if any?

• Would local democracy benefit if town councils had more powers?

• What resources would they need if given more powers?

• What might town councils have to do post COVID?

• Finally, what effect, if any, will Brexit have on their towns (ie wider, non-council-specific impacts)?

Approximately 25,000 words of text were contributed by 156 respondents.15 Therefore, the quotations used in this paper to illustrate the range of views expressed by the respondents are representative, rather than comprehensive.

Should town councils have more powers post-COVID?

The majority of councillors and council staff believed town councils should have more powers, with only 13 respondents opposed. Eight non-council-connected respondents were supportive (Table 3). As discussed below, however, there was a range of views

Of the 156 respondents, 18 explained their reasoning. Those in favour believed more could be done if councils were given commensurate responsibility, authority, money, time and experienced, qualified people. The most-mentioned powers relate to aspects of planning and car parks/parking. However, the same respondents also had concerns about accountability, experience/competence, limited time (most councillors are volunteers), doubts that higher-tier authorities would transfer the money needed to pay for devolved responsibilities, and the need for appropriate monitoring of council activities by a public body (the nature of this ‘public body’ was not defined).

The following give a flavour of the responses:

… if there are any major projects/monies to be spent on a Town the local community and Council should be consulted … always, but particularly during COVID when communication is so difficult (Independent).

… a review of how Town Councils are funded is required. Policy generated at Town level is far more targeted than projects instigated at county or national level. The capacity of volunteer Council members to fully represent their ward and work full-time in many cases excludes many good people from serving (Independent).

In keeping with the spirit of subsidiarity, I think that the idea of differentiated devolution to community level makes sense – and is entirely in keeping with the UK’s messy way of dealing with local government reform! So more powers AUTOMATICALLY for those communities which FULFIL CERTAIN CRITERIA WHICH INDICATE THAT THEY CAN EXERCISE those powers successfully. And a subset of those powers for those communities which can’t fulfil those criteria but which WANT to take them on anyway, as rubber-stamped by a local referendum (An academic who is also the CEO of a public governance body) (Respondent’s capitalisation).

One of 11 respondents who believed councils should not have more powers wrote: “As unpaid councillors they lack accountability and usually have little or no experience of the responsibilities they are elected for” (local charity chairman). This was a relatively commonly expressed, although possibly subjective, concern – because, as councillors must be elected (unless returned unopposed or co-opted), it is hoped that voters believe their representatives either have the necessary qualities, or the commitment and ability to acquire them.

A council clerk noted that “… the powers [councils] have … are sufficient. It is probably more a case of working in conjunction with local groups, charities, organisations and the community.” Four of the 19 clerks who answered this question made this point, suggesting that town councils are in a position to do more with the powers they have, subject to specified financial and legislative limits; and this view is supported by the National Association of Local Councils (NALC n.d.; Tharmarajah 2013), and the LGA (2013a).

On the other hand, a Labour councillor argued that: “Powers without the finance to implement them are purely notional. We can and do raise a precept but this comes on top of Council Tax. So we might dream but cannot realistically expect to implement.”

One district councillor who represents a town with a population of approximately 40,000, but without a town council of its own,16 wrote, “[No more powers] yet. Can only ever be based on a rigorous assessment of their competencies” (No affiliation given).

An academic with a background in local government research expressed uncertainty, writing: “I’m not sure they should [have more powers]. In my experience town councils are often very focused on a narrow set of issues and often not very dynamic.” However, a community development academic, while also uncertain about some councils’ potential to do more, was less negative, suggesting the following powers would be needed: “Fundraising, planning, housing for locals, environmental sustainability, relevant services development.”

Two councillors, from different counties, expressed both uncertainty and hope. A Liberal Democrat town and unitary county councillor with several years’ experience commented: “It is difficult to anticipate the detail but financial pressures are making it more likely that the local authority will devolve some functions and services to town and parish councils.” More optimistic was an Independent councillor with less than four years’ service, who noted: “The District Council will disappear in [2023, when a new unitary council will be created] so the … town council will be able to take responsibility for local issues previously dealt with by the District Council.” The sense of inevitability regarding devolution was expressed by the councillor from the established unitary authority, while the optimistic view came from a councillor in the area about to be reorganised. Only time will tell if the optimistic view persists post reorganisation.

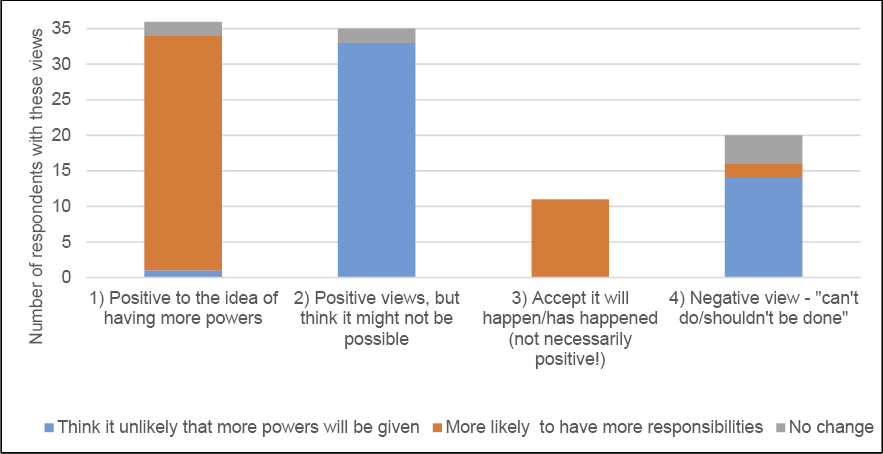

In addition to the above snapshot of broadly supportive, but nuanced, views, every comment was analysed thematically (see Brennon et al. 2018), as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Thematic summary of free-text contributions as to whether councils should have more powers post COVID

Although the majority view is positive (Bars 1 and 2), doubt and scepticism are evident. For example, the positive views in Bar 1 are dampened by the belief that responsibilities (orange colour), not powers, are more likely to be devolved. Respondents believe, therefore, that although they want more power (to decide and act in their own interests), only responsibilities will be devolved (ie work thrust upon them, perhaps without the money needed to enable the work to be done).

Others with positive views believe devolution might not be possible (Bar 2) or accept that devolution will happen (or has happened) but that the experience will be (or is) not wholly positive (Bar 3). Overall, there are doubts that additional powers (as opposed to responsibilities alone) will be granted. Nevertheless, despite doubts about some councils’ fitness to develop policy (Bar 4), many respondents believe, as discussed in the next section, that their councils could both develop and implement policies.

Which policies are councils well placed to develop and implement post-COVID?

Despite reservations, 133 respondents believe councils could develop and implement local policies. However, of the 22 who commented, only three were definite in their support. Two, a Labour councillor and an Independent councillor from different authorities, stressed the benefits of local knowledge. The third respondent gave the following examples: “The town council … has like other Dorset towns been busy in shaping its policies to meet the Climate Emergency. In our case by purchase of electric-powered vehicles, looking to install solar panels on buildings on the … [p]laying fields, energy-efficient flood lighting and … tree planting …” (Liberal Democrat).

Overall, respondents are clear about their priorities: planning/neighbourhood planning, transport (for example, local/public transport, road safety, parking, street cleaning, highways) and housing (Table 4a). These are familiar themes, featuring in evaluations of the then UK government’s Market Towns Initiative (MTI) from the early 2000s (Entec UK 2004; Moseley et al. 2005; Morris 2010, pp. 164–166), earlier research by the Rural Development Commission (RDC) (eg, RDC 1993, 1995, 1996) and a recent report calling for a rural strategy (Rural Services Network 2019).

Most respondents think their councils could, if given opportunity and resources, address new or expanded policy areas. Their suggestions, specific in terms of current and future needs (Table 4b), fit well with the topics listed in Table 4a.

A minority – 13 – of respondents oppose town councils having more powers, as this comment illustrates: “To give [councils] more powers without checks and balances is totally wrong. It is almost impossible to remove councillors. [Councils] should be in a position to have an overview of the community but this only works if those involved behave with integrity” (Independent). During telephone interviews, two other Independents emphasised the need for councillors and clerks to be aware of, and to adhere to, the Nolan principles of conduct in public life,17 especially accountability and leadership.18 The views of a Conservative town and district councillor were particularly trenchant in relation to councils’ fitness for purpose: “… town councils should in the main be abolished. Parish [ie, in this case, the smaller/village settlements] councils also need to be challenged in their usefulness. … Simply giving extra powers to parish and town councils is of no use if the will and competence to use those powers is not there.” Another Conservative identified the tension at the heart of this discussion: “I do not believe … they are in a position to take on more power and, locally, I think that this has been demonstrated during the COVID-19 outbreak. Against that they have demonstrated … an ability to deal with the more human element of government” [emphasis added].

Would local democracy benefit if councils were given more powers post COVID?

The majority of respondents, 122, believed democracy would benefit. Four believed nothing would change, 26 thought things would be more fractious (although that did not necessarily mean worse, simply more challenging), and five did not know. The following examples illustrate this diversity of opinion:

Local democracy would undoubtedly benefit, but while greater controversy is probable if not inevitable, this needn’t necessarily descend into fractiousness (Conservative).

Local democracy in a small town can mean ‘The usual suspects’ having a say. … Town Councillors come and go … . Services require committed attention and time (Labour).

Generally speaking there has always been a failure on the public’s part to distinguish which council does what. … However, as the now-gone districts pulled back from having a local presence leaving the town council as the only office where the public could drop in, towns have been assumed [mistakenly] to do everything … If the new unitary authority decides to delegate, more people may recognise the towns as important decision-makers … (Liberal Democrat).

If done well, then local democracy could definitely benefit because a Town Council can understand the views of the public better at the local level and councillors can play a role in involving local people more … (Independent).

Other respondents mentioned the following impacts: the need to avoid party politics, which can “… override local consensus” (Labour); the possibility that interest in local elections could increase (Independent); and the need to ‘educate’ the public and increase accountability and training (Independent). Additional comments which did not directly address the question nevertheless raised pertinent points such as long-standing concerns about levels of funding in rural areas (Rural Services Network 2019; Rural England 2022).

Resources councils would need if granted additional powers post COVID

Respondents were asked to identity the resources councils would need if given additional powers. They emphasised the need for more staff, training for staff and councillors, local support in terms of public understanding, and help for younger people to become involved. Tax-raising powers were considered to be less important, with only 41% of respondents wanting them. The fact that more than 80% wanted more powers to develop and implement local policies, suggests a continued need for external funding and/or alternative sources of local revenue. Comments reinforce this:

Compulsory training … stronger legislation for dealing with councillors who would, if in employment, be subject to disciplinary or dismissal due to their behaviour (Clerk).

Ability to raise finance other than from local council tax. For example, access to car park revenue, business rates and [Business Improvement District19] allocation, bigger [Community Infrastructure Levy20] allocation (Liberal Democrat).

The residents cannot support council tax as they are going to food banks and working (Independent).

… I’ve ticked anything which improves and encourages participation in local democracy … . If the plan is to do more then it’s likely to require more staff with well-trained decision-makers … the present tax-raising powers are fine as long as central government keeps out of it. At town level … there is benefit in keeping it a part-time evening activity where the whole council plays a full part in decision-taking. … trying to professionalise this tier of representation is quite difficult (Liberal Democrat).

Better IT support for councillors … . More training for Clerks to achieve a minimum standard with succession planning as standard (Independent).

An Independent from a popular tourism area noted the adverse financial effects on council budgets of holiday lets and second homes. Others called for control over, and revenue from: car parks/parking, planning, business rates, business improvement districts, and the community infrastructure levy (Liberal Democrat, two Independents, town market manager).

Taken together, the views expressed suggest councils have the powers to do more, and councillors could do more, but are limited by time, money, staff numbers, pressures on them as volunteers (usually), and doubts about skills, knowledge and accountability. Overall, however, respondents believe that given support more could, and perhaps should, be done locally, especially in light of the benefits that local knowledge brings. For example, a town mayor wrote: “In my pyramid of democracy national government is across the broad base, then there are … layers of local authority with [at] the tip town and parish councils which are the most in touch with local affairs.”

There were concerns, however. For example, there is a belief that councillors21 and councils should be independently and publicly audited to assess their competence, and worries that assets and responsibilities will be devolved without associated funding (mentioned by Independent councillors).

Another Independent councillor expressed concern about poverty, and the implications for the council arising from the (in)ability of residents to pay their council tax. Similarly, a clearly angry and disillusioned Conservative wrote: “Until we have total democracy in all Town, Parish and District Councils, the people will carry on suffering. … From experience alone in this council, it’s more about climbing the political ladder plus having a title: out of 16 Town Councillors only myself and one other Councillor are actively helping the residents …”.

Although, naturally, respondents’ views are diverse, and specific to their town’s circumstances, with COVID-19 endemic and Brexit’s consequences yet to be fully understood the world will be different. The study therefore also asked respondents to think about how the post-COVID/Brexit world will affect their council and town.

What might town councils have to do post COVID?

A word cloud program22 was used to identify the ‘top 20’ topics respondents believe they will have to address after COVID-19. They are presented – broadly related to the number of mentions – in Table 5. Support for businesses, the high street, key infrastructure and street furniture is to be expected. The inclusion of public toilets – a contentious topic – will surprise no one. Relief, however, may be at hand if the Non-Domestic Rating (Public Lavatories) Bill passes into legislation, because business rates (ie, tax) will no longer be levied on councils’ public lavatories (Clarke 2020).

Sixteen comments relate to the young, but only three to the elderly. This might reflect concerns about problems particular to the young, who have been badly affected by COVID lockdowns.23 For example, one councillor expressed concerns about young people’s mental health and the need for the council to improve coordination with schools, police and health services. Also noted was the need for related training for councillors. Whereas before the pandemic there was at least as much concern about the plight of (some) older people, for example in relation to health inequalities (Haighton et al. 2019), concern is now expressed for both young and old.

In addition to the familiar topics identified (eg planning), eight respondents referred to hinterland/local area relationships. This may be a reflection of, or a harking back to, the greater roles played by town councils before 1974, when some were higher-order district councils. One respondent (Independent) recognised this: “Some aspects of that old approach are now too large for a [town council] …”, but believed that “… most of what the [district] does could be passed to a [town council], and the remainder up to county.”

Respondents making this connection come from towns ranging in population from approximately 6,500 to 22,000. Although the views expressed are unrelated to town population, a council’s ability to take on greater responsibilities could vary with population. To explore this, nine towns in three population bands were selected, and their respondents’ contributions compared (Table 6).

| Location | Population | Policy areas identified by respondents (verbatim from survey) | Respondents* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Devon | 3,300 |

|

Two councillors & one community group chair |

| Warwickshire | 4,500 |

|

One councillor |

| Cumbria | 4,700 |

|

One councillor |

| Cornwall | 9,500 |

|

One councillor |

| Northamptonshire | 10,400 |

|

One councillor |

| Cheshire | 11,800 |

|

Two councillors |

| Lincolnshire | 17,000 |

|

Four councillors |

| Cornwall | 20,000 |

|

Two councillors |

| Somerset | 27,000 |

|

Two councillors |

*Three of the respondents were ‘double-hatted’: two are also county councillors, and the third a district councillor.

From the analysis above, it appears that planning, together with transport and traffic, local environments and economies, are important irrespective of population. Priorities are not limited, or defined, by population, but are shared across the range. Although no respondent recommended returning to the pre-1974 arrangements, the policy areas identified hint at past responsibilities, suggesting a desire, albeit cautious, and with little expectation, for more power/influence/recognition for councils.24

Respondents’ views about the possible effects of Brexit on their towns

Brexit effects have been masked to some extent by COVID-19. It seems likely, however, that they will become more apparent (Tetlow and Pope 2020), so respondents were asked for their views.

Comments (4,000 words) were analysed. Putting aside the twelve hard-to-classify and the non-answers, 50 respondents were broadly unclear as to the likely impact, while another 50 believed effects will be minimal. Of the rest, six respondents believe Brexit will be beneficial and 38 believe the opposite, as the quotations in Table 7 illustrate.

Views range from the succinct “Get it done” from a Conservative Brexit supporter to the following from a Liberal Democrat who believed Brexit would be bad, but made a broader point:

If we do not have a deal with the EU then I expect goods coming into the country will be delayed and more expensive. Likewise exporting will be … more bureaucratic … The time is limited and there are insufficient experienced people to do this in the UK. … If we do not have a deal with the EU then a deal with the US would be more necessary but I fear the poorer quality of food products (hygiene) and higher prices for pharmaceuticals from the US – crippling the NHS budget.

An Independent councillor thought some towns would be unaffected:

We are a rural community with 20% of our population comprising the staff and pupils of a well-known Public School 25 … our largest employer. Their pupils are drawn from all around the world so Brexit is unlikely to be that much of a negative impact. Our second largest employer imports mainly from China and sells in the UK so again little negative impact. Our local farmers may be negatively impacted on any exports but most seem to sell within the UK at present.

A Conservative councillor recognised potential adverse effects: “[Brexit] probably has more implications for the larger employers in the town regarding licences, logistics and import tax” – but supported the decision to leave the European Union, being “… a strong supporter of Brexit … [hence] … bring forth the day we cut away from the Apron Strings of Europe.”

| Respondents’ views and number of comments received under each heading | Comments (verbatim) |

|---|---|

| Beneficial Six comments made | Opportunities in tourism and community business support. Bring it on! (Rutland, no affiliation given) Pro-Brexit; give us more control of our small market town. (Conservative, Yorkshire) I am not aware of any implications for our council. Personally, the sooner the better! (Conservative, Worcestershire) |

| Minimal 50 comments | On the [council specifically] very little except maybe a need to reduce the precept and some of our more ambitious projects like improving the public realm. On the community it could be massive hitting employment hard – a vicious circle not helped by COVID-19. (Independent, Wiltshire) Possible increase in fuel prices but little change in Town Council activities as such. We have two large international employers here. They may be affected. (Liberal Democrat, Dorset) None of any immediate consequence, beyond the wider implications nationally. (Conservative, Warwickshire) |

| Damaging 38 comments | Nothing directly, though it will have an impact on the town’s main manufacturer and everyone else as the result of higher costs if deal or no deal. There is nothing better than what we had. (Liberal Democrat, Cumbria) I think the implications are the same for the whole country … more expensive foods and goods. Less jobs. (Labour, Derbyshire) Brexit will damage our local economy – the farmers are very concerned. My business (retail) is closing next month and Brexit has already had a negative impact on it and then COVID came …. So the impact will be indirect, ie the local economy being affected which then reduces the funds for the Council etc. (Independent, Cumbria) |

| Don’t know/Uncertain/Unclear 50 comments | Politically … Brexit is not a concern … the Town Council may have a part to play in supporting those … who will lose the most as a result of this extraordinary backward step. COVID-19 and Brexit will lead to a number of fundamental changes in how much can be done for whom and by whom. Keeping in touch with those we represent … and being ready to assist … will become a basic part of the Town Council’s role in the future. (Independent, Dorset) Who knows, but probably not positive. We were founder members of European Charter Towns but that has sadly gone. (Labour, Northamptonshire) If you can answer that you are a better man than me. Here we are [in 2020] with days to go [before we leave] and still nobody knows what is actually happening. Whichever way you voted it’s an absolute shambles. (Independent, Yorkshire) |

The polarised, binary nature of the UK’s Brexit debate is evident from these comments. The views of those in favour were expressed pithily and confidently, in contrast to the generally longer comments made by those who were uncertain/worried about the eventual effects on towns and country. References were made to the possibility of social unrest, the need to have to step in to help other parts of government, and potential damage to local economies (eg farming). However, the majority view, broadly one of uncertainty, is probably a fair summary – nearly six years after the referendum, still we wait and see.

Discussion and concluding remarks

As this research illustrates, the views of councillors and staff (together, the majority of respondents) were as varied as the towns they represent. Most believe their councils should have a greater role, and more powers, in relation to local policy development and implementation, with planning, housing and transport dominant. A minority believe both that democracy would benefit, and that locally things would become more fractious if councils assumed more powers/responsibilities – but not necessarily the worse for that.

There are concerns, however. Although keen to have more powers (and money and staff), respondents believe it more likely that only responsibilities will be devolved, especially in areas where unitary authorities have replaced county and district councils.26 Also recognised, and much mentioned, is the need for training and monitoring of performance and standards for councils, their councillors and staff.

The nearly 25,000 words of opinion contributed by respondents were a mix of ambition, hope, realism, and some scepticism/cynicism. Underlying it all, there is no obvious expectation of significant change, and an acceptance, from some, that this is as it must be, given the demands of the work, and the implications of the challenges. The potential for town councils to do more via the General Power of Competence is acknowledged – but so are its limitations, and the unwillingness of some to use it.

And yet the trend towards fewer, larger higher-tier local authorities, the centralised, top-down nature of English government, and complicated local governance structures (Morris 2018, p. 57), strongly suggests a need for accessible, accountable, relatable, elected local councillors.27 In similar vein, a recent report commissioned by the British Prime Minister aims to sustain “… the community spirit we have seen during the coronavirus pandemic” (Kruger 2020, p. 7). Its author Danny Kruger, a Conservative MP with a background in charity work, proposes that: “Decisions on what is done in local places should be taken by people as close to the ground as possible, ideally the people who actually live there” (p. 14).

Kruger’s report emphasises the important contributions that local volunteer-led organisations and charities can make to help achieve “… a more plural, local, bottom-up system …” (p. 7). It mentions, inter alia, a scheme that “… would multiply current community infrastructure investments by local authorities many times over, and put real power in the hands of local people to direct how that money (currently allocated by councils behind closed doors) is spent” (p. 46).28 The reference to ‘councils behind closed doors’ is revealing, suggesting a lack of confidence in (and/or support for) local government/councillors.

In this it is reminiscent of the Conservative-dominated coalition government’s community-orientated programme, the Big Society (Cabinet Office 2010), which was viewed by some in the UK (Coote 2010) and as far away as Australia (Whelan et al. 2012) as a mechanism to shrink the state. Although Kruger acknowledges the Big Society’s connection with austerity (Kruger 2020, p. 12), and is clear his proposals require state investment (p. 39), the implication that councils cannot (or should not?) lead their communities, remains.

Interestingly, the opposition Labour MP Ed Miliband takes a similar view to Danny Kruger in relation to localism. Although their political standpoints are different, both see a role for local government as facilitators/enablers of locally-led work (Kruger 2020, pp. 15, 36; Miliband 2021, Ch. 14). This suggests there is – among some political thinkers, at least – a degree of agreement about the need for devolution.

To add weight to this is the re-emergence of the idea of ‘double devolution’ (Treadwell et al. 2021), 16 years after Ed Miliband’s brother David spoke of “a double devolution of power from Whitehall to the town hall and from the town hall to citizens and local communities” (Weaver 2006, p. 1), again with the emphasis on citizens and – undefined – communities. However, in response to David Miliband’s speech, the Conservative party (then in opposition) criticised the government of which he was a member for “removing local control and accountability across the board, and diminishing faith in local democracy” (Weaver 2006, p. 1). Despite this professed outrage, successor governments, all Conservative-led, cut grants to local government by 37% in real terms between 2009-10 and 2019-20 (Institute for Government 2022).

There are, therefore, long-standing contradictions in many areas of this debate: intentions around devolution; encouragement to establish new parish councils (LGA 2021); the democratic processes and finances central to England’s tiered, but centralised, government structure; and the implicit preferences for non-elected volunteers over elected (but also essentially volunteer) councillors.

As an aside, this preference will strike a chord with anyone (including this author) who was involved with the previously mentioned Market Towns Initiative. Although a government programme (DETR/MAFF 2000, Ch.7), centrally and regionally funded, and led day-to-day by local people, there was a preference for the work to be community-led (ie not town-council-led). This resulted in tension between some town groups and their councils. Suffice to say, partnerships worked better when councils were involved and supportive (Morris 2010, pp. 166–168).

Today, however, town councils are preparing for the post-COVID world. For example in Frome, Somerset, the council’s recovery plan is designed to bring together businesses and community organisations in order to understand their needs, and to develop ways to support the town’s most vulnerable people (Wheelhouse 2020). Similarly, in Woodbridge, Suffolk, the council has an emergency response group of councillors and volunteers to help with “… collection/delivery of medicines, shopping, walking the dog or simply being a voice at the end of the phone …” (NALC 2021).

To turn now to Brexit. In a recent paper, Hadfield and Turner (2021, p. 19) note that there are doubts as to whether central government will centralise or devolve, and that only time will tell if “… Brexit will prove [to be good or bad] for English local authorities.”

Although there is recent research into the likely effects on local government of Brexit and COVID-19 (Hadfield and Turner 2021; Gore et al. 2021), this relates primarily to the higher tiers of local government. There is little, if any, research into the town (parish) level. Nevertheless, a recent survey of rural services “… indicates [that] smaller towns have proved more resilient [in relation to COVID-19] than might be expected …” (Rural England 2022, p. 3), so it is suggested that further research would cast useful light on the potential of England’s town councils to help overcome the challenges they are likely to face in the post-COVID and post-Brexit world.

The analysis in this paper suggests that change is needed, and wanted, by some. The question is, do those who want it have the determination and wherewithal to acquire it, and will those with greater powers ever allow it?

COVID-19 and Brexit were serious challenges for the United Kingdom government when the research explored in this paper began in August 2020. Today, they are still problematic, with COVID-19 endemic (at best), and legal and practical adjustments related to Brexit still outstanding (Husain 2022). Added to this are the all-too-obvious dangers associated with the war in Ukraine. Taken together these present considerable, possibly long-term, problems for central government.

In view of this, now could be a good time to use the government’s developing ‘levelling up’ policy to devolve to local authorities, including town councils, the powers, responsibilities and resources needed to enable them to address local policy priorities. There will be failures, but there will also be successes – and, from both, opportunities to learn.

To coin a phrase: if not now, when?

To conclude, an Independent councillor, an interviewee, asked, “Is this [research] going to be of any use to town councils?” My answer was that I don’t know, but, as the majority of the contributors to the research were councillors and clerks, my hope is that it will add something of value to the debate.

Acknowledgements

Many people contributed to this research: councillors, clerks, council staff, interested locals, academics/local government professionals, friends and colleagues. Thank you. It has been a challenge and a privilege to (attempt to) analyse, summarise and do justice to the views of such knowledgeable people. Thanks also to the peer reviewers who took the time and trouble to read and comment on this paper.

Any errors or admissions are the author’s.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

Bibby, P. and Brindley, P. (2017) 2011 Rural-urban classification of local authority districts and similar geographic units in England: a user guide (revised 2016 & 2017). London: Department of the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs.

Brennon, R., Metcalfe, C. and Barratt, M. (2018) How to analyse qualitative data for evaluation. NCVO Knowhow. Available at: https://knowhow.ncvo.org.uk/how-to/how-to-analyse-qualitative-data-for-evaluation#. [Accessed 4 February 2021].

Cabinet Office. (2010) Building the big society. London: Cabinet Office.

Carr, H., Glover, B., Phillipson-Brown, S., Smith, J., Essex, M. and Burt, S. (2020) The future of towns. London: Demos, Whitehall.

Carrington, R. (2020) Rural youth adapting to challenges presented by Covid-19. Coyote Magazine (Council of Europe & European Union). Available at: https://pjp-eu.coe.int/en/web/coyote-magazine/rural-youth-adapting-to-challenges-presented-by-covid-19 [Accessed 30 March 2021].

Centre for Towns. (2019) Our towns. Available at: https://www.centrefortowns.org/our-towns [Accessed 24 September 2019].

Clarke, L. (2020) Councils may soon not have to spend a penny on public loos. Community News, 24 July 2020. Available at: https://www.inyourarea.co.uk/news/councils-may-soon-not-have-to-spend-a-penny-on-public-loos/. [Accessed 29 March 2021].

Commission for Rural Communities. (2008) Views on the recommendations made by the Councillors Commission, ‘Representing the Future’. Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, UK: CRC.

Coote, A. (2010) Cutting it the ‘Big Society’ and the new austerity. London: New Economics Foundation.

Copus, C. and Leach, S. (2020) Six lessons for devolution from COVID-19. The Municipal Journal, 24 June 2020. https://www.themj.co.uk/Six-lessons-for-devolution-from-COVID-19/217972. [Accessed 10 January 2021].

Copus, C., Leach, S. and Jones, A. (2020) Bigger is not better: the evidenced case for keeping ‘ local ’ government. Leicester: District Councils Network.

Countryside Agency. (2004) The state of the countryside, 2004. Cheltenham, Glos., UK: The Countryside Agency.

Cullinane, S. and Stokes, G. (1998) Rural transport policy. Kidlington, Oxfordshire: Pergamon, Elsevier Science.

Davenport, A. and Zaranko, B. (2020) Levelling up: where and how? London: Institute for Fiscal Studies.

DCLG. (Department for Communities and Local Government.) (2006) Strong and prosperous communities. The Local Government White Paper. Pub. L. No. 6939–1. UK: DCLG.

DCLG. (Department for Communities and Local Government.) (2011) A plain English guide to the Localism Bill. London: UK Government.

Department for Transport. (2021) Future of transport: rural strategy – call for evidence - summary of responses. London: UK Government.

DETR/MAFF. (Department for Transport, Local Government and the Regions/Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries.) (2000) Our countryside: the future. London, UK: HM Government.

Entec UK. (2004) Assessment of the market towns initiative. Shrewsbury. Entec UK Ltd.

Gore, T., Dobson, J., Bimpson, E.A. and Parkes, S. (2021) Local government responses to the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK: a thematic review. Sheffield, UK: Sheffield Hallam University. https://doi.org/10.7190/cresr.2021.6172521344

Hadfield, A. and Turner, C. (2021) Risky business? Analysing the challenges and opportunities of Brexit on English local government. Local Governmemnt Studies, 47 (4), 657–678. doi:10.1080/03003930.2021.1895768

Haighton, C., Dalkin, S. and Brittain, K. (2019) An evidence summary of health inequalities in older populations in coastal and rural areas. Full report. London: Public Health England.

Hambleton, R. (2017) The super-centralisation of the English state – why we need to move beyond the devolution deception. Local Economy, 32 (1), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269094216686296

Higham, D. (2021) English devolution (and the mystery of the disappearing speech). London: The Constitution Society.

Hill, J. (2021) Concerns over proposals to devolve power to town and parish councils. Local Government Chronicle. Available at: https://www.lgcplus.com/politics/devolution-and-economic-growth/concerns-over-proposals-to-devolve-power-to-town-and-parish-councils-17-11-2021/ [Accessed 22 April 2022].

Hill, J. (2022) Analysis: Devo framework leaves the government holding all the cards. Local Government Chronicle, 8 February 2022. Available at: https://www.lgcplus.com/politics/devolution-and-economic-growth/analysis-devo-framework-leaves-the-government-holding-all-the-cards-08-02-2022/ [Accessed 8 February 2022].

Husain, E. (2022) Early insights into the impacts of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic and EU exit on business supply chains in the UK. Business, Industry and Trade Insights – Office for National Statistics. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/businessindustryandtrade/internationaltrade/articles/earlyinsightsintotheimpactsofthecoronaviruspandemicandeuexitonbusinesssupplychainsintheuk/february2021tofebruary2022#impacts-of-the-coronavirus-covid-19-pandemic-and-eu-exit-on-bu [Accessed 14 March 2022].

Institute for Government. (2022) Local government funding in England. Institute for Government Explainer Series. Available at: https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/explainers/local-government-funding-england. [Accessed 18 March 2022].

Ipsos MORI Social Reseach Institute. (2010) Rural insights – residents survey 2009. Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, UK: Commission for Rural Communities.

Kruger, D. (2020) Levelling up our communities: proposals for a new social covenant. A report for government by Danny Kruger MP. London.

Local Government Association. (LGA) (2013a) The general power of competence empowering councils to make a difference localism. London: LGA.

Local Government Association. (LGA) (2013b) Stand for what you believe in. Be a councillor. London: LGA (Conservative group).

Local Government Association. (LGA) (2018) A councillor’s workbook on working with town and parish councils. London: LGA.

Local Government Association. (LGA) (2019) Councils can. London: LGA.

Local Government Association. (LGA) (2021) Local service delivery and place-shaping: A framework to support parish and town councils. LGA Briefing. Available at: https://www.local.gov.uk/publications/local-service-delivery-and-place-shaping-framework-support-parish-and-town-councils [Accessed 3 March 2022].

Local Government Chronicle. (2013) The general power of competence – empowering councils to make a difference. Localism. London: LGC.

Local Government Chronicle. (2016) Power to the people. London: LGC.

Local Government Chronicle. (2017) Where next for localism? Special report on town and parish councils. London: LGC.

Malik. K. (2021) Full pubs are a sign of communities that work. Clubs, libraries and youth centres are vital to our lives as we move out of lockdown. The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2021/apr/11/full-pubs-are-a-sign-of-communities-that-work-lets-toast-their-return [Accessed 12 April 2021].

Miliband, E. (2021) Go big. 20 bold ways to fix our world. London: Penguin Random House, UK.

Morris, G. (2003) 2002, a spatial odyssey an investigation into the sphere(s) of influence of Sherborne, Dorset (an English country town). Seale Hayne, University of Plymouth, UK.

Morris, G. (2012) Leading communities: community-led development in England’s small towns: the market towns initiative. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, (11), 33–52. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.v0i0.3056

Morris, G. (2018) Rural policy, rural quangos – searching for clarity in West Dorset, south west England. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, (20), 44–70. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.v0i20.6022

Morris, G.R. (2010) People helping people – an assessment of the market towns and related initiatives, and the extent to which they addressed rural poverty. University of Exeter. http://encore.exeter.ac.uk/iii/encore/record/C__Rb2482913

Moseley, M., Owen, S., Clark, M. and Kambites, C. (2005) Local issues in rural England – messages from the parish plans and market towns health checks. Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, UK.

Nabarro, B. (2021) The future isn’t what it used to be. IFS Green Budget Chapter 2. London: Citi.

National Association of Local Councils. (NALC) (n.d.) What are local councils? (Section 1). London: NALC.

National Association of Local Councils. (NALC) (2021) Coronovirus – information for local councils. Available at: https://www.nalc.gov.uk/coronavirus#local-councils-supporting-their-communities [Accessed 19 May 2021].

Owen, S., Moseley, M. and Courtney, P. (2007) Bridging the gap: an attempt to reconcile strategic planning and very local community-based planning in rural England. Local Government Studies, 33 (1), 49–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930601081226

Page, B. (2022) Perceptions: the fact and fiction of trust and satisfaction. Local Government Association. Available at: https://www.local.gov.uk/our-support/leadership-workforce-and-communications/comms-hub-communications-support/futurecomms-1 [Accessed 9 February 2022].

Parr, J.B. (2020) Local government in England: evolution and long- term trends. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, (23), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi23.7382

Pearce, G. and Ellwood, S. (2002) Modernising local government: a role for parish and town councils. Local Government Studies, 28 (2), 37–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/714004139

Powe, N., Hart, T. and Shaw, T. (eds.) (2007) Market towns. roles, challenges and prospects. Abingdon: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group.

Rural Development Commission. (RDC) (1993) The rural housing problem. Salisbury, UK: RDC.

Rural Development Commission. (RDC) (1995) Planning for people and prosperity. Salisbury, UK: RDC.

Rural Development Commission. (RDC) (1996) Country lifelines – good practice in rural transport. Salsibury, UK: RDC.

Rural England. (2022) State of rural services 2021. Available at: https://ruralengland.org/state-of-rural-services-report-2021/ [Accessed 14 April 2022].

Rural Services Network. (2019) It’s time for a rural strategy. A call on government by the Rural Services Network. Tavistock, Devon, UK: RSN.

Shearer, E. and Shepley, P. (2021) Towns fund. Institute for Government Explainers Series. Available at: https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/explainers/towns-fund [Accessed 7 February 2022].

Shepherd, J. (2009) A typology of the smaller rural towns of England. London: Birkbeck College (Rural Evidence Research Centre).

Sherborne UDC and RDC. (1970) Annual Reports (1970) for Sherborne’s urban and rural district councils. Wellcome Collection. Available at: https://wellcomecollection.org/works?query=sherborne+council [Accessed 6 January 2021].

Stevens, A. (2006) The politico’s guide to local government. 2nd ed. London: Politico’s/Methuen.

Stewart, J. (2014) An era of continuing change: reflections on local government in England. Local Government Studies, 40 (6), 835–850. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2014.959842

Tetlow, G. and Pope, T. (2020) Brexit and coronavirus. Economic impacts and policy response. London: Insitute for Government.

Tharmarajah, M. (2013) Local councils explained (sample pages). London: National Association of Local Councils.

Treadwell, J., Tanner, W., Stanley, L. and Krasniqi, F. (2021) Double devo: extending town and parish councils. The case for empowering neighbourhoods as well as regions. Onward. Available at: https://www.ukonward.com/reports/double-devo-town-and-parish-councils/ [Accessed 18 March 2022].

UK Government. (2022) Levelling up the United Kingdom (CP 604). London: UK Government.

Walker, A. and Diamond, P. (2020) Power down to level up: resilient place-shaping for a post-Covid age. London: Local Governmemnt Information Unit.

Weaver, M. (2006) More power to the people, urges Miliband. The Guardian, 21 February 2006. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2006/feb/21/localgovernment.politics [Accessed 18 March 2022].

Wheelhouse, P. (2020) Towards a Covid-19 recovery plan for Frome. Frome, Somerset: Frome Town Council.

Whelan, J., Lyons, M., Wright, N.-N., Long, A., Ryall, J., Whyte, G. and Harding-Smith, R. (2012) Big society and Australia. How the UK Government is dismantling the state and what it means for Australia. Sydney (Haymarket): Centre for Policy Development.

Willett, J. (2021) The deep story of Leave voters affective assemblages: implications for political decentralisation in the UK. British Politics, 16 (2). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41293-021-00171-x

Willett, J. and Cruxon, J. (2019) Towards a participatory representative democracy? UK Parish councils and community engagement. British Politics, 14 (3), 311–327. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41293-018-00090-4

Woods, M. J. (2005) Contesting rurality. Aldershot, Hampshire, UK: Ashgate Publishing Ltd.

1 The research was conducted with the approval of the ethics committee of the University of Exeter’s College of Social Sciences and International Studies. For more information, please contact the author, G.R.Morris@exeter.ac.uk.

2 Brexit is a contraction of the words ‘British Exit’ (ie from the European Union). This exit has profound economic, political and social consequences for the UK, which may take many years to become fully clear.

3 Legally, town councils are ‘parish’ councils in England. For historical reasons some councillors of even relatively large settlements choose to refer to themselves as parish councillors; others use the term town councillor. Both are correct.

4 These, often based in the same ‘market’ town, were distinct – relatively small – authorities, although they could share staff, such as medical officers of health (see Sherborne UDC & RDC 1970).

5 Unitary councils are councils formed from mergers of county and district/borough councils.

6 “In simple terms, [the GPC] gives councils the power to do anything an individual can do provided it is not prohibited by other legislation” (Local Government Chronicle 2013, p. 8).

7 A combined authority is a legal body set up using national legislation that enables a group of two or more councils to collaborate and take collective decisions across council boundaries (https://tinyurl.com/y9rc7at2).

8 Town councils are in an interesting position relative to higher-tier authorities, in that their freedom to raise money from local taxation is relatively unrestricted. They have few duties, but relatively wide-ranging powers (LGA 2021).

9 The report draws on the work of the Centre for Towns (www.centrefortowns.org/about-us). This organisation, established in 2017, conducts research into settlements with populations between 5,000 and circa 75,000.

10 Hosted by https://www.onlinesurveys.ac.uk/.

11 As the research took place during the COVID-19 pandemic, face-to-face interviews were not possible.

12 All 15 interviews took the form of conversational discussions lasting 15-60 minutes. Interviewees’ strongly-held but diverse views and ambitions contrasted, in most cases, with their frustrations about ‘the system’ they operate in.

13 Many appear in the lists of Market Town Initiative participants, ‘hub towns’, and the Centre for Towns’ villages, communities and small towns categories (Morris 2012, p. 40; Bibby and Brindley 2017, p. 12; Centre for Towns 2019). Although there are about 1,600 settlements broadly classified as ‘small towns’, with populations between 1,500 and 40,000, this is not definitive (Shepherd 2009, p. 2).

14 Approximately 10% of England’s small, ‘market’, towns, as identified by the then Countryside Agency (2004, p. 217).

15 The respondents’ full answers to all questions can be found here: https://tinyurl.com/m932ryw6, as can the longer preprint (search for June 2021, Annexe, and Preprint, 8 June 2021).

16 Many small settlements are ‘unparished’, ie, have no parish/town council. Instead, they hold an annual parish meeting, a mechanism that allows residents to express their views and pass them on to the higher authority. The town referred to does not have a town council but is home to the area’s district council. It is relatively unusual for such a large town not to have its own parish/town council. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unparished_area.

17 Selflessness, integrity, objectivity, accountability, openness, honesty, leadership (https://tinyurl.com/lso4fnj).

18 Despite some concerns, one councillor (Independent) believed that local democracy would benefit if councils were given more powers, as they are potentially well placed to develop and implement policies.

19 https://www.gov.uk/guidance/business-improvement-districts

20 https://www.gov.uk/guidance/community-infrastructure-levy

21 A resident and two clerks suggested that councils, as organisations, be subject to some form of audit, or supervision, by a regulatory body.

22 https://monkeylearn.com/word-cloud/

23 For example, a Scottish online survey of 600 18-28-year-olds found that respondents felt anxious, worried and lonely (Carrington 2020).

24 Powers devolved by central government have mainly been to the regions. For example the Major and Blair governments (1990–1997 and 1997–2007 respectively) created government offices and regional development agencies, neither of which lasted. More recently, ‘metro mayors’ (Higham 2021) were introduced in 2017 but seem already to be set for change, with the UK Government’s recent ‘levelling up’ White Paper referring to a new model for “… counties with mayors or ‘governors’” (UK Government 2022, p. xxviii).

25 In the United Kingdom public schools are, counter-intuitively, schools which are privately funded and managed, often with international pupils.

26 See https://tinyurl.com/33t7v6yh

27 Achieving this might be difficult given that the majority of town councillors are volunteers.

28 For an example, see https://about.spacehive.com/case-studies/glyncoch-community-centre/.