Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance

Issue 24

June 2021

POLICY AND PRACTICE (PEER REVIEWED)

Enhancing Youth Participation in Local Governance: An Assessment of Urban and Rural Junior Councils in Zimbabwe

Paradzai Munyede

College of Business, Peace, Leadership and Governance, Africa University, Zimbabwe, munyedep@africau.edu

Delis Mazambani

College of Business, Peace, Leadership and Governance, Africa University, Zimbabwe, mazambanid@africau.edu

Jakarasi Maja

Cultural Anthropology and Development Studies, KU Leuven University, Belgium, maja.jakarasi@student.kuleuven.be

Corresponding author: Paradzai Munyede, College of Business, Peace, Leadership and Governance, Africa University, Zimbabwe, munyedep@africau.edu

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi24.7734

Article History: Received 18/01/20; Accepted 02/04/21; Published 28/06/21

Citation: Munyede, P., Mazambani, D. and Maja, J. 2021. Enhancing Youth Participation in Local Governance: An Assessment of Urban and Rural Junior Councils in Zimbabwe. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, 24, 124-135. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi24.7734

© 2021 by the author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Abstract

Over the years, youth participation in local decision-making across Africa has been minimal, despite the existence of enabling human rights frameworks on youth participation as well as institutions such as junior councils. This research aimed to compare the efficacy of Zimbabwe’s urban and rural junior councils in enhancing youth participation in local governance, which in turn would promote reform of the current participation frameworks, the realisation of children’s rights and ultimately productive community development. This paper is a product of qualitative research, combining desk research and key informant interviews with 22 council and ministry officials as well as eight focus group discussions with sitting and former junior councillors in Harare, Bulawayo, Bindura, Mutare, Masvingo, Rushinga, Makonde and Mbire. It was found that junior councils lacked adequate funding and technical support, resulting in tokenistic participation in local governance. Their legal status is unclear as both government ministries and local governments claim ownership. The research findings suggest that junior councils could be strengthened through the enactment of a specific legal framework to regulate their activities.

Keywords

Youth Participation; Junior Councils; Efficacy; Local Governance; Human Rights

Introduction

The African Union’s Agenda 2063 (African Union Commission 2015) and the African Youth Charter (African Union Commission 2006) both present frameworks which aim to fundamentally reinvigorate and prioritise youth participation in Africa’s contemporary and future development dynamics. Consequently Zimbabwe, as a member state of the African Union, is obliged to promote, protect and fulfil real and active youth participation. Aspirations 48 and 58 of Agenda 2063 provide that:

All the citizens of Africa will be actively involved in decision-making in all aspects of development, including social, economic, political and environmental. Young men and women will be the path breakers of the African knowledge system and will contribute significantly to innovation and entrepreneurship. The creativity, energy and innovation of Africa’s youth shall be the driving force behind the continent’s political, social and cultural transformation (African Union Commission 2015).

In 2017 the annual Youth Forum of the United Nations Economic and Social Council noted that Africa has the largest youth population in the world. It is estimated that Africa has approximately 226 million youths, aged between 15 to 24 years, constituting 20% of her population. Projections show that this proportion is likely to grow to 42% by 2030 (United Nations 2017). This demographic reality presents immense opportunities for the continent to achieve sustainable development through the infusion of fresh ideas and innovations. Therefore, youth participation needs to become an integral component in influencing decision-making not only at the local level but also across diverse portfolios of governance. A key challenge, however, has been the limited space available for youth to influence and participate in decision-making at the local level – despite the fact that restricted participation of youths in the socio-economic activities of their communities is contrary to the principles of democracy, as enshrined in the African Union Agenda 2063 (Kirby and Bryson 2002).

One significant youth participation initiative at the local level in Zimbabwe is the junior council, where youths aged between 16 to 18 years get the opportunity to participate in local governance. Its governance structure mirrors that of the senior council,1 but its mandate is restricted to child rights issues. In Zimbabwe urban junior councils have been in existence for several decades, but in rural areas they are a recent creation. In view of the above, the aim of this paper is to make a comparison of the efficacy of urban and rural junior councils in enhancing youth participation in delivering local governance, reforming current participation frameworks and promoting realisation of children’s rights with the ultimate goal of realising robust community development.

Methodology

This research employed a comparative case study approach to interrogate the efficacy of junior councils in a sample of four urban and four rural local authorities. The urban councils studied were Harare Metropolitan, Bulawayo Metropolitan, and the cities of Mutare and Masvingo. The rural local authorities studied were Rushinga, Mbire, Makonde and Bindura. All were purposively selected due to their geographical proximity and availability of information for the researchers. Review of related literature was carried out to form a basis for the research and to supplement primary data. Key informant interviews were held with officials to gather primary data from local governments’ perspective (four Chief Executive Officers of rural district councils, three Chamber Secretaries from urban councils and eight focal persons who are senior council officials responsible for coordinating all activities of junior councillors). Also, seven interviews were held with district heads of government departments from the Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education as well as the Ministry of Youth, Sport, Arts and Recreation to capture the policy position of central government. Additionally, eight focus group discussions with current and past junior councillors were used to gather information from the respondents.

Local government and junior councils in Zimbabwe

Local governments in Zimbabwe are the lower tier of government responsible for the provision to communities of services such as safe drinking water, education and health. Decisions to deliver particular services are arrived at through the participation of local communities or institutions such as junior councils. Munyede and Mapuva (2020) have highlighted that local governments in Zimbabwe are constitutional bodies established under Chapter 14 of the Constitution. There are two distinct categories of local government: urban councils and rural district councils. Urban councils are concentrated in well-developed areas with reasonable levels of modern infrastructure, while rural district councils occupy remote and partially developed landscapes. The two types of council operate under different Acts of Parliament: namely the Urban Councils Act (Chapter 29:15) of 1995 and the Rural District Councils Act (Chapter 29:13) of 1988 respectively. In terms of population distribution, 67% of Zimbabweans reside in rural areas and 33% in urban areas (Chigwata and Marumahoko 2017).

According to the National Junior Councils Association (NJCA), junior councils were established in the 1950s in what was then known as Salisbury,2 and subsequently spread to other towns (NJCA 2014). In an effort to promote inclusivity, the NJCA was formed in 2011 to advocate for the establishment of junior councils in rural district councils.

Sakala (2018) and Musarurwa (2019) posit that the mandate of the junior councils is the promotion of good local governance and community development through the sharing of ideas between youth and elders in the context of deliberations on sustainable development. However, in spite of the fact that junior councils have been in existence for around 70 years in urban areas of Zimbabwe, there has been limited evaluation of their efficacy as a participation mechanism, whether in urban or rural areas.

Conceptualisation of youth participation

Youth participation is a multi-faceted concept (Sakala 2018). There are several ways in which youth can participate in and influence decision-making, including debates, religious clubs, sporting activities and participation in governance systems. Musarurwa (2019) maintains that in Zimbabwe junior councils are the strongest platform through which youth can influence decisions, policies and legislation, as they allow interaction between youth and elected officials, thereby creating a forum for cross-pollinating inter-generational ideas.

However, despite the merits of junior councils, it has been argued (in the Tanzanian context) that their operations are hampered by paradoxes and controversies (Couzens and Mtengeti 2012). In this case the problems were attributed, inter alia, to the traditional view of the position that youth occupy in society – ie that junior councils lack the knowledge and skills to influence substantive governance decisions, and are instead viewed as only recipient objects of local governance. Sakala (2018) supports this view when she points out that, in Zimbabwe, the link between youth participation and local governance has not been fully explored and there is little published evidence which shows inclusion and effective participation of youth in decision-making. Moreover, this study also found some interviewees (senior councillors, government officials and council employees in Rushinga, Makonde, and the cities of Mutare and Masvingo) arguing that junior councils lack the capacity to comprehend the intricacies of governance in general and policy-making in particular.

Another issue of concern is whether senior councils are actually allowing young people to influence decision-making at the local level, especially in rural areas where junior councils were introduced only recently, in 2011. Some critics of the junior council initiative view the participation of young people in local government as mere tokenism. In their view, the outcomes of youth participation in policy-making, for both the participants and the constituency they purport to represent, have been insignificant.

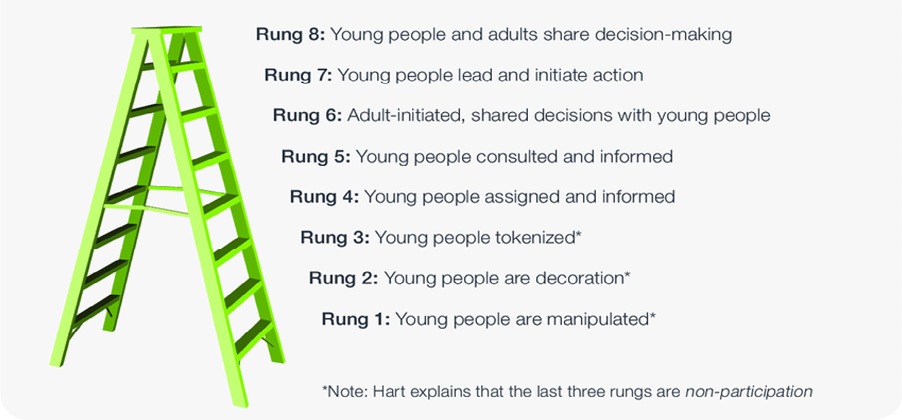

Roger Hart (1992) proposed a ladder of young people’s participation, which is presented below in Figure 1. Hart’s ladder suggests that levels of participation may range all the way from manipulation and tokenism at the bottom, to full citizenship at the top. This research seeks to locate the current participation level of rural and urban junior councils in Zimbabwe on the ladder.

Figure 1. Roger Hart’s ladder of young people’s participation

Normative frameworks for youth participation in local governance

The following human rights standards contextualise youth participation in governance.

Universal declaration on democracy

Participation is a basic tenet of democracy and the inclusion of youth in local governance is a means of promoting democratic governance. Articles 4, 11 and 19 of the Universal Declaration on Democracy provide for the right of everyone to take part in the management of public affairs (Inter-Parliamentary Union 1997). Youth should have the same rights as adults to participate in the management of public affairs. According to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), when governance is democratic it is infused with respect for human dignity, justice and equity as well as adherence to principles of participation, the rule of law, transparency and accountability (UNDP 2014).

United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child

International, regional and domestic human rights frameworks are in unison that participation is a human right, to which children are also entitled. Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) asserts a child’s right to express an opinion and to have that opinion taken into account, in any matter or procedure affecting the child, in accordance with his or her age and maturity. Prompted by Article 12, many institutions, including schools and parliaments, are now involving young people in the policy-making process.

United Nations Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development

Zimbabwe is a signatory to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (United Nations 2015) which ushered in the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The central transformative promise of the SDGs is to ‘leave no one behind’ – so youths should not be left behind in local governance issues. The SDGs provide a comprehensive framework encompassing the three dimensions of sustainable development: economic, social and environmental. These dimensions also form the governing framework of service delivery, which is the main mandate of local authorities. Participation of youths in local governance increases the likelihood of inclusion of their needs in policies, thereby promoting the realisation of their rights.

African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child

The African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (African Union Commission 1990) also reinforces the obligation of both primary and secondary duty-bearers to facilitate the participation of children in decision-making at all levels of society, including local governance. Articles 4 and 7 state that children have the right to express their opinions freely and these opinions should be heard and taken into account when decisions affecting them are made. Article 31 of the Charter provides that children have responsibilities towards their families and societies: to respect their families, superiors and elders; and to preserve and strengthen African values in association with other members of their communities. It is through participation in community life that they can promote the African value of ubuntu (humanity), as is also emphasised by Critical Area 1 of the African Union Agenda 2063, which highlights African identity and renaissance as important aspects of African development.

Constitution of Zimbabwe (2013)

The Constitution of Zimbabwe places emphasis on non-discrimination and equality. Section 2 of the Constitution outlines the founding principles and values which guide Zimbabwe. It highlights good governance as one of the key principles. Good governance also entails recognition of the rights of women, the elderly and youth. Sections 20 and 81 of the Constitution of Zimbabwe (2013) specifically provide for the rights of youth and children. On the issue of participation, section 20 provides for the right to have opportunities to associate and to be represented and participate in political, social, economic and other spheres of life. Section 81 states that a child’s best interests are paramount in every matter concerning the child. It seems self-evident that it is in the best interests of young people to take part in decision-making that affects them.

Findings: challenges and opportunities for Zimbabwe’s junior councils

The findings emanating from this research are twofold. They include both challenges to and opportunities for participation of junior councillors from urban and rural areas in local government.

Access to resources

Some urban junior councils, such as the one for the City of Harare, had access to funding from corporate bodies, which made it possible for them to hold meetings once every month to deliberate on service delivery issues affecting children. In addition, the rapport created with the corporate world over the years has helped the Harare junior council to raise funds for the drilling of a borehole in Hopley, a peri-urban area in Harare which has perennial water challenges. The junior council has also been spearheading distribution of sanitary wear to young women in both Harare and surrounding rural communities. Further, the junior council regularly carries out advocacy work in schools highlighting children’s rights issues such as child abuse, early marriages, cyber-bullying and drug abuse. Similarly, in the City of Masvingo the junior council has been raising funds for better marking of roads at pedestrian crossings near schools so as to ensure road safety for children. Further, they have been assisting children’s homes and the Zimcare Trust for children with learning difficulties by providing food items, using funds generated from various fund-raising activities.

However, unlike their urban counterparts which can source funding from the corporate sector, most rural junior councils mainly rely for funding on the rural district councils, which are poorly resourced, and to some extent on non-governmental organisations. In most rural district councils, like Mbire, Rushinga and Makonde, the junior councils are still in their infancy and have yet to register any meaningful achievements due to limited experience and resources.

Also, junior councillors from rural areas were disgruntled by what they saw as preferential treatment afforded to junior councillors from urban areas in terms of capacity-building opportunities such as seminars, workshops and conferences, as well as by their lack of representation at national events organised by the NJCA.

Contested ownership of junior councils

From discussions with officials from government ministries and councils, it was noted that there was disagreement as to who should be the custodian of junior councils. For example, the Ministry of Youth, Sport, Arts and Recreation was actively involved in organising debates for children in liaison with the Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education, but local authorities were not included in the planning processes for these events. Councils were only approached when there was a need for them to support participation of junior councils in the debate competitions.

Most importantly, local authorities did not play any part in the selection of junior councillors, which alienated them from the institutions that they are supposed to supervise. Instead, the selection process is based on poetry and speech competitions organised by teachers and youth officers from the Ministry of Youth, Sport, Arts and Recreation, who act as judges. Because of this, the council-based interviewees argued that the junior councils were giving their allegiance to the two ministries responsible for their appointment rather than to the councils which host them.

The selection process for junior councillors was widely viewed as being undemocratic. It was highlighted that in some cases schools nominated students who were favoured by the education authorities, and not those preferred by their peers. Also, while the selection process involved nominees writing essays and/or being interviewed, the topics covered had little bearing on children’s rights such that most of the candidates who were selected had limited knowledge of the issues on which they were supposed to advocate.

Lack of legal framework for junior councils

Local junior councils are loosely linked to the national Youth Council, which is established under the Zimbabwe Youth Council Act (Chapter 25:19) of 1983, and by policy directives such as a circular dated 16 November 2017 from the Ministry of Local Government and Public Works which encouraged all local governments to establish junior councils for the purpose of empowering youth in decision-making. However, the lack of a specific legal framework regulating junior councils creates an opportunity for duty-bearers in local governments to evade their responsibilities to afford the junior councillors platforms to participate in decision-making.

Tokenistic participation in local governance

It was a common sentiment amongst interviewed junior councillors, especially those from rural district councils, that the junior council in its current form is tokenistic in nature. The youths indicated that they were not being afforded enough opportunity to fully execute their mandate due to underfunding and irregular meetings. The junior councillors said they were randomly called for meetings, including on occasion during school hours, thus disturbing their learning process. This random convening of meetings also affected the continuity and implementation of resolutions made by the junior councils, which remained in abeyance to the detriment of the rights of the children they represented. Junior councillors also complained that their meetings were used as cash cows by officials from government ministries, councils and civil society organisations, who attended only to get travel and subsistence allowances. It was observed that workshops with minimal financial support had few representatives from the said institutions, such that the meetings ended up being just unproductive forums without any deliverables.

These meetings therefore appear to fall under rungs 1, 2 and 3 of Hart’s ladder – tokenism at best. While in both urban and rural councils the objectives of meetings appeared to promote youth participation, in practice the adults were prioritising their own personal interests and benefits.

Operational restrictions by the Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education

Junior councillors further reported that their workplans and priorities were often disrupted by the Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education, which refused to authorise them to conduct activities relating to their duties. Also, while in urban areas junior councillors were able to travel to council chambers for meetings on their own, in rural areas they were supposed to be always accompanied by a student mentor for security reasons. This increased operational costs which local governments were expected to fund, but the councils lacked budgets for such costs. Even where funding was available, councils viewed such expenditure as a waste of resources which they felt should be channelled to service delivery. Given the above dynamics, senior councils ended up excluding the junior councillors from council activities due to delays by the Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education in providing participation authorisations or clearances to take part in planned activities.

Geographical spread and travelling challenges

In rural areas, junior councillors often live in locations far from the council chambers. The discussions highlighted that it was relatively easy to invite junior councillors to meetings in urban areas as this could be done through phone calls, social media, emails and physical visits. However, in rural areas coordinating junior councillors was usually complicated as means of communication were poor. Also, travelling costs in rural areas were high, making it difficult to hold frequent meetings.

Lack of transparency in management of junior council funds by senior councils

Some junior councillors reported that while senior councils engaged them when developing workplans and prioritising activities, budget issues were not shared and there was limited disclosure pertaining to the allocation of financial resources to junior councillors by senior councillors. In some instances when junior councils requested to conduct certain activities using their budget allocation, they were informed that the funds had been utilised for other related activities. This was difficult to verify due to gatekeeping of information and lack of accountability by those in charge of finances in senior councils. The junior councillors viewed such conduct as suspicious, since they were not given any breakdown of expenditures made on their behalf by the senior councils.

Lack of visibility and community support for junior councils

Junior councillors highlighted that they lacked visibility, and claimed they were only given recognition at commemorations of children’s rights such as the annual Day of the African Child. They highlighted that they were excluded from other important national activities such as budget consultations and the annual National Junior Council symposium, both of which have significant implications for the participation rights of youth.

Opportunities for enhancing youth participation in junior councils

The research identified three important frameworks and opportunities to enhance youth participation in junior councils.

Firstly, as discussed above, there is a plethora of normative frameworks which place an obligation on the state to facilitate and promote youth participation in local governance. These include the Universal Declaration on Democracy; the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child; United Nations Security Council Resolution (2250) of 2015 on Youth, Peace and Security; the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Children; and the African Union Agenda 2063.

Secondly, there are legislative frameworks such as the Constitution of Zimbabwe Amendment Act (No 20) of 2013, the Urban Councils Act (Chapter 29:15) of 1995 and the Rural District Councils Act (Chapter 29:13) of 1988 which recognise the importance of youth participation in decisions relating to service delivery, but which are currently silent on the establishment of junior councils. This lacuna continues to render junior councillors ‘third parties’ in local government structures, leading to the financial problems they face and indirect reporting to both the Ministry of Youth, Sport, Arts and Recreation and the Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education. Correction of this legal anomaly could enhance the effective functioning of junior councils. Similarly, as noted earlier, central government has issued circulars affirming its support for junior councils and directing that senior councils prepare budget lines for their activities. This provides a rallying point to advocate for inclusion of such provisions in local government legislation.

Thirdly, institutions like the National Youth Council and NJCA, which are already recognised by government authorities, need to be strengthened so that they become forceful in advancing and promoting the active participation of youth in local governance matters. There is also scope to build on the commitment to support junior councils by non-governmental organisations such as Save the Children, World Vision and Gender Links in terms of technical advice, financial support and capacity-building.

Conclusion and recommendations

From the review of literature and findings uncovered by this study, it can be concluded that youth participation in governance through junior councils in Zimbabwe is still at the tokenistic stage of Hart’s ladder of participation. This is due to minimal government and community support to ensure that junior councils can effectively perform their mandate of mainstreaming children’s rights in service delivery. While all the junior councils surveyed experienced a range of obstacles to their successful operation, the problems were especially acute in rural areas where resources are scarce, communications are often poor, and junior councils have only recently been established.

The following opportunities and recommendations for improvement are proffered:

• If junior councils are to be effective in the discharge of their mandate, the government ministries directly responsible for youth affairs, education and local councils must collaborate and come up with a ‘coherent’ legal framework for effective participation of youth at local government level.

• The selection process for junior councillors carried out by the Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education in conjunction with the Ministry of Youth, Sport, Arts and Recreation needs to be reviewed so that they adopt a transparent nomination process – for example through a secret ballot by young people. Further, local governments must be part of the selection team and should lead the selection process, which would encourage them to take ownership of the junior councils.

• Mentoring of junior councillors by their senior councillors through regular joint full council sittings and community meetings is recommended, to facilitate holistic dialogue on community development issues.

• The Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education should not be too restrictive when junior councillors seek authorisation or clearance to perform their duties as councillors.

• Local governments, as the primary duty-bearers on service delivery issues, must involve youth in both planning and budgeting and desist from incurring expenses related to junior councils without consulting them. Their spending should conform to financial principles relating to the transparent and accountable utilisation of public financial resources.

• Funding for junior council activities must not be left to local governments to shoulder alone; schools should also budget for such activities from revenue raised through fees and development levies.

• Senior councils should take practical steps to ensure that resolutions made by junior councils are implemented, so that issues relating to children and youth are properly taken into account when service delivery programmes are implemented.

• Councils, especially in rural areas, need to plan meetings for junior councils taking into account realistic timeframes needed between notification and the date of the meeting, as well as the costs associated with convening of meetings.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

African Union Commission. (1990) African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child. Available at: https://www.au.int/en/documents-45

Africa Union Commission. (2006) African Youth Charter. Available at: https://www.au.int/treaties/african-youth charter

African Union Commission. (2015) Agenda 2063: The Africa we want. Available at: https://au.int/en/agenda2063/overview

Chigwata, T.C. and Marumahoko, S. (2017) Intergovernmental planning and budgeting in Zimbabwe: Learning the lessons of the past. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance. (20), 172–186. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.v0i20.6140

Couzens, M. and Mtengeti, K. (2012) Creating space for child participation in local governance in Tanzania: Save the children and children’s council. Tanzania: Research on Poverty Alleviation.

Government of Zimbabwe. (1983) Zimbabwe Youth Council Act of 1983, Chapter 25:19. Harare: Government Printers.

Government of Zimbabwe. (2013) Constitution of Zimbabwe Amendment (No.20) Act 2013. Harare: Government Printers.

Hart, R.A. (1992) Children’s participation: From tokenism to citizenship. Florence: UNICEF International Child Development Centre.

Inter-Parliamentary Union. (1997) Universal Declaration on Democracy. Available at: https://www.ipu.org/file/7135/download

Kirby, P. and Bryson, S. (2002) Measuring the magic? Evaluating and researching young people’s participation in public decision-making. London: Carnegie Young People Initiative.

Munyede, P. and Mapuva, J. (2020) Exploring public procurement reforms in rural local authorities in Zimbabwe. Journal of Public Administration and Governance, 10 (1), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.5296/jpag.v10i1.15156

Musarurwa, H.J. (2019) Exploring social entrepreneurship as a youth peace building tool to mitigate structural violence: Action research using mixed methods in Zimbabwe. (Doctoral dissertation, Durban University of Technology, South Africa).

National Junior Councils Association of Zimbabwe. (NJCA) (2014) A guide to junior councils in Zimbabwe. (Unpublished).

Sakala, M. (2018) Child participation and community development in Zimbabwe. A case study of Kadoma junior city council (2011–2017). Available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/33373253

United Nations. (2015) Transforming our world:The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. New York: United Nations. Available at: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld/publication

United Nations. (2017) ECOSOC youth forum concept note regional breakout session Africa. Available at: https://www.un.org/ecosoc/sites/www.un.org.ecosoc/files/files/en/2017doc/CN-Regional-Breakout-Session-on-Africa.pdf

United Nations Development Programme. (UNDP) (2014) Discussion paper. Governance for sustainable development. Integrating governance in the post -2015 development framework. Available at: https://www.google.com/search?q=UNDP+Governance+for+Sustainable+Development+Integrating+Governance+in+the+Post-2015+Development+Framework

United Nations, General Assembly. (1989) United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Available at: www.unicef.org.au

United Nations Security Council. (2015) Resolution 2250 (2015) on youth, peace and security. Available at https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/s_res_2250.pdf

1 The senior council comprises elected ward councillors who are the policymakers for both urban and rural councils.

2 Salisbury was the capital of the former State of Rhodesia. It was renamed Harare when Zimbabwe attained independence in April 1980.