Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance

Issue 28

September 2023

RESEARCH AND EVALUATION (PEER REVIEWED)

Fiscal Decentralisation and Public Service Delivery: Evidence and Lessons from Sub-National Governments in Kenya

Justa Wawira Mwangi

Kenyatta University, PO Box 43844-00100, Nairobi, Kenya, justamwangi@gmail.com

Gitile Naituli

Multimedia University, PO Box 15653-00503, Nairobi, Kenya, gnaituli@gmail.com

James Kilik

Kenyatta University, PO Box 43844-00100, Nairobi, Kenya, jmkilika@gmail.com

Wilson Muna

Kenyatta University, PO Box 43844-00100, Nairobi, Kenya, wmunah2007@gmail.com

Corresponding author: Justa Wawira Mwangi, Kenyatta University, PO Box 43844-00100, Nairobi, Kenya, justamwangi@gmail.com

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi28.7712

Article History: Received 13/05/2021; Accepted 24/06/2023; Published 25/09/2023

Citation: Mwangi, J. W., Naituli, G., Kilika, J., Muna, W. 2023. Fiscal Decentralisation and Public Service Delivery: Evidence and Lessons from Sub-National Governments in Kenya. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, 28, 5–23. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi28.7712

© 2023 by the author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

(CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties

to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the

material for any purpose, even commercial, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Abstract

This paper provides empirical evidence on the effects of fiscal decentralisation on public service delivery in devolved systems of government in Kenya. A qualitative study interviewed 126 respondents and held two focus group discussions with key stakeholders from within two of Kenya’s 47 counties: Kiambu and Nairobi City. The paper focuses on key elements of fiscal decentralisation, namely: expenditure responsibilities, revenue autonomy and borrowing powers. Public service delivery was examined using affordability as a key measure of the quality of services. Results show that fiscal decentralisation did not necessarily lead to more affordable public services as there were significant contextual factors such as corruption, legal structures, cultural values, belief systems, pressure to conform and change agents that moderated this relationship. Corruption made public services less affordable in both counties, while Nairobi Metropolitan Services emerged as a change agent that improved the affordability of specific public services within Nairobi City county. The paper outlines a conceptual framework for further research into implementation of fiscal decentralisation in Kenya and elsewhere, especially in Africa, and calls for more qualitative studies, especially longitudinal studies, case studies and ethnographic approaches to enrich knowledge in this field.

Keywords

Fiscal Decentralisation; Public Service Delivery; Devolved Systems of Government; Local Governments

Introduction

Devolution, in the form of constitutional provisions whereby political, administrative and fiscal responsibilities are vested in regional or local governments, has gained traction globally over the last three decades: over 35% of the world is currently fully devolved, while over 60% is under some form of devolution (Sujarwoto 2017). This trend seems to be influenced by new public management theory, which proposes that governments should decentralise responsibilities to improve public services and counter inefficiency (Martinez-Vazquez et al. 2017).

Devolution typically comprises a blend of political, administrative and fiscal decentralisation, with varying degrees to which authority is either vested in devolved governments, or simply delegated to subordinate units or agencies of central governments (Salinas and Sole-Olle 2018). This paper focuses on fiscal decentralisation, which involves the vesting of expenditure responsibilities, revenue autonomy and borrowing powers in devolved governments, and which was identified from the literature as one of the key factors affecting public service delivery in devolved governments (Martinez-Vazquez et al. 2017). This paper looks specifically at fiscal decentralisation in Kenya, in light of the country’s 2010 Constitution that created devolved systems of government in a bid to improve public services (Wagana 2017).

A critical examination of the literature points to several difficulties in explaining the current status of fiscal decentralisation in the Kenyan context. First, the literature on the relationship between fiscal decentralisation and public service delivery is inconclusive and contradictory (Diaz-Serrano and Meix-Llop 2019). There is hardly any information on the strengths and weaknesses of alternative models and it appears that the effect of fiscal decentralisation on the quality of public services is not well understood (Novi et al. 2019). This paper argues that how fiscal decentralisation is construed and the specific geographical and cultural settings of its implementation impact public service delivery outcomes.

Second, there is a preponderance of literature on fiscal decentralisation and public service delivery from developed countries, but an inadequate interrogation of the issue in Africa (Kyriacou et al. 2017). Given cultural, economic and political differences, the results coming from western countries are unlikely to apply to developing countries such as Kenya. Further, challenges facing developing countries, such as high poverty and unemployment rates, may not respond to western models (Gustafsson and Scurrah 2019).

Thirdly, the few studies conducted in developing countries and Africa face limitations of design and conceptualisation. In terms of design, they are mainly case studies (Wagana 2017) and suffer methodological limitations as they do not offer cross-country evidence on the relationship between fiscal decentralisation and public service delivery (Novi et al. 2019). In terms of conceptualisation, previous studies have concentrated on the accessibility dimension of public services without delving into other aspects of quality (Wagana 2017). In Kenya specifically, studies have mainly been quantitative (Finch and Omolo 2015). The few qualitative studies available have focused on the merits and demerits of fiscal decentralisation without delving into its effects on service delivery (Barasa et al. 2017). Thus, there is an epistemological gap in this area that needs to be filled. The authors responded by undertaking an empirical study and desktop review into the extant literature on the experience of fiscal decentralisation in Kenya and how it has (or has not) enhanced service delivery. The desktop review involved looking at documented literature in government publications, including the Constitution of Kenya (2010), textbooks on public policy and administration, and research on devolution in different counties in Kenya presented in theses, dissertations and peer-reviewed journal articles.

The remainder of this paper presents the conceptual framework for the research; developments in fiscal decentralisation in Kenya; the research design; study findings and discussion; and the conclusion.

Theoretical and conceptual framework

Fiscal decentralisation is a relatively new construct and phenomenon in Kenya, and a sound conceptual and theoretical basis is required upon which it can be rigorously examined to provide the empirical evidence on how it is working and how it relates to service delivery. This section provides a discussion of relevant theories that shed light on how the concept of fiscal decentralisation and the context of its implementation in Kenya needs to be understood. Three theories are seen as particularly relevant to the analysis: social learning theory, positive deviance theory, and institutional theory.

Social learning theory is anchored in the assumption that all behaviour is learned through observation (Garduno 2019). Therefore, as countries adopt fiscal decentralisation, they tend to copy each other, and social learning continues to influence how fiscal decentralisation is implemented. This typically consists in ceding expenditure responsibilities for specific public services, granting revenue autonomy, and vesting borrowing powers in devolved governments to varying extents, drawing on established practices elsewhere (Sujarwoto 2017). If fiscal decentralisation practices are learned, this has implications for the accessibility and quality of public services, as institutional practices known to hinder service delivery may be replicated from one jurisdiction to another (Dunlop and Radaelli 2019). In Kenya, fiscal decentralisation models have been borrowed mainly from western countries and the Bretton Woods institutions (the World Bank and International Monetary Fund), and the social learning that has taken place has not been uniform or consistent (Barasa et al. 2017). The policy transfer that saw fiscal decentralisation implemented in 2010 adopted a ‘big bang’ approach: political, administrative and fiscal decentralisation were introduced simultaneously, causing teething problems which the country is still grappling with (Finch and Omolo 2015; Mbau et al. 2020).

Social learning theory has been criticised for its inability to predict whether interventions would bring positive or negative impacts. In the case of fiscal decentralisation, this may include failure to predict impacts on the accessibility and quality of public services (Salinas and Sole-Olle 2018; Kyriacou and Roca-Sagales 2019). This study may be the first time the theory has been used to discuss the relationship between fiscal decentralisation and public service delivery.

Positive deviance theory originated in the field of nutrition in the 1970s when nutritionists discovered that amongst severely malnourished children in specific communities, there were a few families with children who were well fed and healthy, despite facing similar challenges such as extreme poverty (LeMahieu et al. 2017). These positive deviants or outliers were carefully studied to evaluate what they did differently, and this information was used to plan nutrition intervention programmes (Baxter et al. 2016). Thus, positive deviance, as an approach to social and behavioural change, presupposes that in any given space or society there are individuals, groups or organisations whose behaviours or strategies will deviate from the norm of what is expected in an advantageous way (LeMahieu et al. 2017). These outliers are able to deliver solutions to a problem better than their peers – despite facing similar challenges, including having no extra resources and encountering resistance to their ideas (Banerjee et al. 2018) – and can become powerful change agents in society (LeMahieu et al. 2017). In this study the theory suggests there may be positive deviants within devolved governments who are critical change agents in salvaging failing fiscal decentralisation policies – especially in Africa where the literature is riddled with policy failures (Andersen et al. 2020). Such outliers would help us understand why the majority fail while a few succeed, and how we can leverage the latter’s successes to improve the accessibility and quality of public services (Baxter et al. 2016).

Despite its touted successes in various fields, our current understanding of how the positive deviance approach works, and evidence regarding its effectiveness, is limited (Baxter et al. 2016). There is little guidance on how to operationalise its fundamental tenets, with positive deviants being identified by different scholars using different methods, some of which have been seen to lack validity or reliability (Kyriacou and Roca-Sagales 2019). Although the theoretical and empirical analysis of positive deviance is a discipline still in its infancy, this paper views positive deviants as key game changers who can offer solutions to the challenges faced by fiscal decentralisation and its quest to provide accessible and quality public services in Kenya. However, the possible enablers and drivers of positive deviance in fiscal decentralisation are still unknown and, as in the case of social learning, this may be the first time the theory has been used in that context.

Institutional theory seeks to explain how institutions arise and how they affect organisational behaviour (Berthod 2018). As government is a key institution within society, its nature and behaviour is a critical factor in implementing fiscal decentralisation and understanding its bearing on the accessibility and quality of public services, particularly in developing countries such as Kenya where fiscal decentralisation has often been touted as the answer to the failures of centralised governance (Muna 2016). In terms of government as an institution, the theory suggests that fiscal decentralisation will bring forth new structures of government and de-institutionalise those entities no longer considered necessary (Gustafsson and Scurrah 2019). However, some of the practices of these abolished entities may be carried over during transitional periods and then become part and parcel of the new structures (Scott 2013). In the case of Kenya, such inherited practices may have adversely impacted implementation of fiscal decentralisation and service delivery when previous local government structures were scrapped and replaced (Boone et al. 2019).

Although institutional theory has been credited with illuminating how institutions constrain or support organisational actions and decisions, critics have argued that it fails to account adequately for the roles of power and self-interest (Lammers and Garcia 2017). Thus, even though devolved governments might be expected to perform in a certain way, outcomes may prove contrary to expectations due to the actions of those able to exercise power in their own interests (Peterson and Peters 2020).

Conceptual model

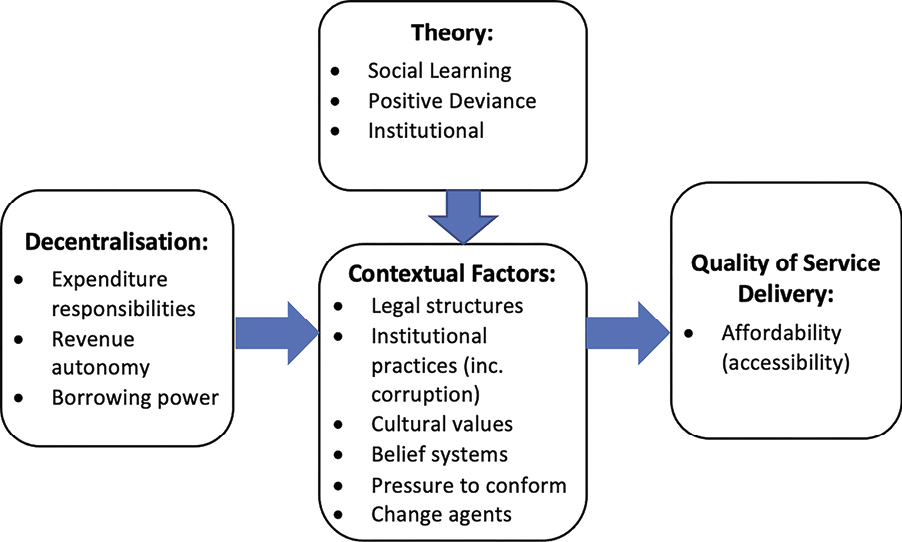

To guide this research, and based on the above theories and the literature on fiscal decentralisation referenced in the Introduction, the authors adopted a conceptual model that articulates the relationship between fiscal decentralisation and public service delivery. This is shown in Figure 1.

Fiscal decentralisation is defined in terms of expenditure responsibility, revenue autonomy and borrowing powers, while public service delivery covers the quality of services in terms of affordability (which also relates to accessibility). The model also identifies a number of contextual factors linked to social learning, positive deviance and institutional theories, that may moderate the relationship between fiscal decentralisation and public service delivery.

In Kenya, expenditure responsibility is construed as a constitutional function bestowed on the counties which gives them authority to expend public resources for service delivery within their jurisdiction. This covers their own resources and revenues, as well as grants or loans received from central government, commercial sources and donations. Revenue autonomy refers to the county’s power to levy taxes without interference from the national government, and to make independent decisions on how such revenue will be utilised for service delivery within the county. Borrowing power refers to the counties’ ability to raise loans to meet service delivery goals.

Developments in fiscal decentralisation in Kenya

Devolution in Kenya began right after independence in 1963, at which time the country had an upper house, a lower house, regional governments and provincial assemblies (Finch and Omolo 2015). However, the law was changed in 1969, scrapping the legislative assemblies and the regional governments and establishing the country as a unitary state (Wagana 2017). It was not until 2010, when Kenya enacted a new Constitution re-establishing devolution, that two levels of government were created: national and local (the counties) (Fonshell 2018).

The approach adopted involved devolving political, administrative and financial powers simultaneously to the 47 county governments that came into being after the 2013 general elections (Wagana 2017). These counties are distinct but interdependent as they derive their powers from the 2010 Constitution, not from the national government. Citizens elect their own governor, deputy governor and county assembly representatives: the assemblies carry out legislative functions and sit as a parliament (Wagana 2017). Additionally, they exercise executive power through the county executive committee, which is headed by the governor and consists of the governor, the deputy governor and ten other appointed public officials who sit as a cabinet (Finch and Omolo 2015). This team is responsible for service delivery within the county. The governor enjoys considerable independence as he or she is directly answerable to the electorate and cannot be sacked by the president of Kenya (Kaburu 2013).

Counties are required to adhere to the principle of separation of powers, where the governor and their executive team implement policies and provide services while the county assemblies oversee and legislate (Wagana 2017). Further, the Constitution limits the powers of the president over the county governments as he or she cannot suspend county governments without setting up an independent commission, whose decisions must be supported by the senate, the upper house of parliament established to safeguard devolved governments. The senate additionally has powers to terminate such suspensions at any time (Kaburu 2013).

The counties have the power to appoint and manage all their employees and to mobilise resources through administrative decentralisation, covering a wide range of specific functions including healthcare, pre-primary education and vocational education (Fonshell 2018). As noted earlier, through fiscal decentralisation, they have been given expenditure responsibility for devolved functions as well as the power to impose taxes and generate other own-source revenues, and to borrow money in accordance with the Constitution (Wagana 2017).

Although the counties enjoy autonomy, this power is not absolute as they are bound by the Constitution to cooperate with the national government. The Constitution envisages interdependence between the two levels of government and provides for consultations as the basis for mutual relations and cooperation (Kaburu 2013). Thus, parliament has set up permanent structures for this consultation to take place, through the Council of Governors and the Intergovernmental Relations Technical Committee, which provide avenues for policy discussions and consensus-building. Such cooperation is evident in the preparation of annual budgets, where the county governments are guided by the Division of Revenue Act that governs the mode of sharing revenues raised by the national government. There is also a County Allocation of Revenue Act, which governs distribution of the money allocated by the Division of Revenue Act to individual counties. On the basis of these two Acts, the counties prepare their own budgets and appropriation bills, which when passed by their assemblies and signed by the governors authorise the withdrawal of monies from the County Revenue Fund (Kaburu 2013).

It is important to note the progress of devolution in Kenya has not been uniform, as counties have tended to implement their functions differently, depending on the idiosyncratic leaning of their elected leaders (Wagana 2017). For instance, some counties have devolved services to the grassroots through the establishment of village administrators and village elders, as stipulated in the County Government Act 2012. Variations have emerged in the performance of counties: Makueni is an example of positive deviance, in that despite facing similar challenges to other counties, it has emerged as a centre of excellence in governance, public participation and service delivery, with others using it as a benchmark as part of social learning (Wagana 2017).

Although the counties derive their fiscal decentralisation powers from the 2010 Constitution, the nature and extent of those powers are limited in practice because the national government still controls the fiscal transfer process and allocations (Wagana 2017). The government has created a legal framework to guide the exercise of counties’ powers, comprising the County Government Act 2012, the Intergovernmental Relations Act 2012, and the Public Finance Management Act 2012. Also, updated Division of Revenue Acts and County Allocation of Revenue Acts have to be passed by the national parliament every year before the counties can access their monies. This often causes delays and lapses in service delivery when funds are not disbursed in time or when there are disagreements on the allocations. Further, while the national government has devolved around 70% of functions it still raises and retains the bulk of tax revenues, such that counties are essentially underfunded (Khamisi 2018). When it comes to revenue autonomy, counties have been left to levy the same taxes as previous local authorities, which are low in yield and difficult to collect (Kaburu 2013).

Similarly, even though the Kenyan counties are vested under the Constitution with borrowing powers, the regulations under the Finance Management Act and the national policy framework for county borrowing are cumbersome (Otieno 2018). For example, the counties are limited to borrowing a maximum of 5% of their audited revenues, and only from the central bank, with a caveat that such monies must be repaid within one year from the date of borrowing. Also, requests to borrow have to be passed by relevant county assemblies before submission to the central bank (Otieno 2018). This has left many counties unable to exercise their power to borrow. However, some scholars argue that the hurdles involved ensure devolved governments do not engage in wasteful spending, which could result in over-borrowing and cause macroeconomic instability (Wagana 2017). This is relevant as counties have often been accused of not meeting their revenue targets, due to over-ambitious budgeting and leakages in revenue collection (Oluoch 2016). Thus, while cumbersome, the processes for borrowing may be seen as a necessary constitutional oversight mechanism.

Among the key objectives for fiscal decentralisation in Kenya was to improve public services. It was assumed that county governments would have local knowledge of community problems and could address these problems by taking services closer to the people. The services to be delivered by counties are derived from the Fourth Schedule of the Kenya Constitution, which delineates the functions of both national and county governments (see Table 1).

Source: Fonshell (2018)

The 2012 County Government Act outlines the principles of public service delivery and vests counties with the legal mandate to provide public services within their geographical jurisdictions. The principles include the responsibility to offer accessible and quality services, bearing in mind the principle of subsidiarity between the two levels of government and also bearing in mind the need to progressively improve the standards and quality of all public services. Counties are expected to adhere to standards which stipulate that all citizens must have access to essential services, and that services shall be of good quality and delivered efficiently, effectively and sustainably. Moreover, priority must be given to the basic needs of the people at all times). The standards further require that county governments have tariffs and pricing policies that are friendly to poor households, in accordance with their right to access essential services.

It can be seen that upon implementation of the functions in the Kenyan Constitution’s Fourth Schedule, the devolved governments have become the largest providers of public services in Kenya. Yet since the process of implementation began in 2013, there is little empirical evidence about the impact of fiscal decentralisation on public service delivery (Mbau et al. 2020). This raises concern from both the public service and academic viewpoints as to which functions have been fully implemented and what effect this has had on service delivery in different counties. The few government reports available deal mainly with the legal and institutional frameworks for fiscal transfers that enable counties to provide public services (Wagana 2017). Evidently, those fiscal transfers have not always translated to improved public services and the counties are still entangled in cumbersome procedures when exercising their revenue autonomy and borrowing powers (Wagana 2017).

Research design

Previous studies have been largely quantitative, providing a plethora of data but not digging deeply into the topic (see for example Diaz-Serrano and Meix-Llop 2019; Arends 2020). The present research is qualitative: it involved the administration of in-depth interviews with 126 respondents, plus two focus group discussions with nine key stakeholders each from Kiambu and Nairobi City counties. Public officials in strategic county functions such as supply chain, finance, revenue, payroll, human resources, authority to incur expenditure, communications, sub-county administration, public participation and information communication technology were targeted for interviews as specified in Table 2. They were selected because studies showed that they had a public-facing role when it came to service delivery and played a key role in the implementation of fiscal decentralisation within the county governments. Suppliers of county services were also included as the literature showed they faced certain vulnerabilities when it came to accessing tenders and receiving payments for their supplies. Additionally, members of the public at various service delivery points were interviewed in a bid to get their perspectives on fiscal decentralisation and public service delivery. They were seen to offer first-hand information on their experiences as recipients of services (Barasa et al. 2017).

*Note: Another 18 key stakeholders participated in the focus groups.

Source: Mwangi et al. (2022)

Focus group participants included business, religious and political leaders; representatives of youth, women and minority ethnic groups; professionals; persons living with disabilities; and non-government organisations. They were targeted to ensure diversity of voices in the data and to capture the critical voices of vulnerable groups who face unique challenges while accessing public services.

The research questions covered the effect of expenditure responsibility, revenue autonomy and borrowing powers on public service delivery in the two counties. The research was carried out over a period of six months, from September 2021 to February 2022, and the data collected from interviews and focus groups was subjected to thematic analysis using Nvivo software. All respondents and focus group participants were asked the same questions (see Table 3).

| Questions | Probe for… | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | What is your view of the expenditure responsibility of the county government? | Whether it has made public services more accessible and improved the quality of public services |

| 2. | What is your experience with revenue autonomy in the county? | Whether it has made public services more accessible and improved the quality of public services |

| 3. | How would you describe your experience with borrowing powers in the county? | Whether it has made public services more accessible and improved the quality of public services |

| 4. | How would you describe the services you receive from the county government? | Whether the services have been geographically accessible, affordable and of good quality |

| 5. | Wrap-up question: is there anything else you would like to add? |

Study findings

As noted above, the data reported in this study capture the opinions of a wide variety of respondents in the counties of Kiambu and Nairobi City: public officials, suppliers to both county governments, other stakeholders, and members of the public. This data is subjective but offers important insights into the effect of fiscal decentralisation on public service delivery and factors that may impact this relationship.

No general improvement to services

Overall, the data suggests that to date, implementation of fiscal decentralisation since 2013 has not brought about an improvement in public services. In fact, there was a widespread view amongst respondents that services had deteriorated in the two counties, and a number pointed to corruption as a key factor. One member of the public put it this way:

Now, these counties, there is no visible work they are doing for us. Service delivery has gone so low due to corruption, it is better if we did not have them.

These views contrast with those of scholars who argue that public services improve when expenditures are planned and managed at the local level (Arce and Hendricks 2019). They assume devolved governments will be more sensitive to community needs, especially those of the most vulnerable, leading to better services that are more accessible in terms of geographical reach and affordability (Kyriacou and Roca-Sagales 2019). Thus, they view decentralisation of expenditure responsibilities as an essential tool for public service delivery, particularly in Africa, where the poor depend on public services for their daily survival (Martinez-Vazquez et al. 2017).

Respondents also stated that siting expenditure responsibilities at the county level has not reduced the cost of public services for ordinary citizens. In the words of one of the suppliers:

…this money that came to the county for public service has been utilised to employ people… we see no development, it is workers and bureaucratic procedures increasing, not improvement of public services… cost of services at the devolved government has increased and the national government services are still cheaper. The cost of services would have been lower if this county money was given to the national government.

Need to increase funding while tackling corruption

Respondents proposed that Kenya needs to increase the level of fiscal transfers and deal with contextual factors such as institutional practices that allow corruption to thrive, if services are to improve. A public official from the executive arm of Kiambu county captured it this way:

The money given to counties from the national government is too little. We want that money to be increased so that services can improve. And corruption needs to be eradicated.

Contrary to the views of some scholars (Blöchliger and Akgun 2018), the data suggests that decentralisation of expenditure responsibilities did not encourage transparency or lead to any major economic gains.

Another respondent, representing women as one of the stakeholder groups, reported that:

…theft of public money has increased, we have not received any improved service since devolution of expenditure in this county, it was better when we were under the municipality. The members of the county assembly do not perform their work of safeguarding our money.

Thus, corruption in the form of embezzlement of public funds is perceived to have increased in the two counties since expenditure responsibilities were decentralised. Residents feel they would be better off under the defunct municipal authorities that were scrapped when the 2010 Kenya Constitution introduced fiscal decentralisation. According to them, the members of the county assemblies who are supposed to oversee the county governments have not been fulfilling their role, as they are supposed to ensure public funds are not stolen. This view supports the stance of fiscal decentralisation critics who assert that the theory does not offer appropriate models to counter the problem of the ‘tragedy of the commons’ and the externalities it creates, especially in countries like Kenya with weak oversight mechanisms and rampant corruption. All these factors limit potential gains in the provision of accessible and quality public services (Hao et al. 2020).

From an institutional theory point of view, the presence of practices that allow corruption to thrive is an important moderating variable in the relationship between fiscal decentralisation and public service delivery. A respondent from the business sector stated that:

…lack of coordination between the county and national governments on alcoholic control has increased my cost of doing business. I pay for a 24-hour licence from the county but the national government which enforces the law says my bar is not supposed to operate 24 hours and the police end up fining me or taking me to court for operating outside the national government’s authorised hours. To survive, I have to bribe them and they in turn look the other way when I don’t pay my county licences… When the county officials come, I also bribe them… That’s why you see the county budgets having big figures for revenue income which is never collected from us...

The businessman was being inconvenienced and incurring high operational costs due to lack of policy coordination between the national and county governments in regulating the alcoholic drinks sector, and experienced corruption as revenues are not collected in exchange for bribes. The data echoes similar studies in Zimbabwe which found that increasing revenue autonomy led to inaccessible and deteriorating public services due to corruption (Chigwata 2017).

Lack of revenue autonomy

A number of respondents blamed deteriorating public services on the cumbersome procedures that counties encounter when trying to raise their own revenues to meet financial shortfalls when central government transfers do not meet their service delivery needs. A public official from the legislative arm of Kiambu county argued that:

…money from the national government is not adequate for service delivery. Counties should be empowered to raise revenues for service delivery without following too many procedures.

The data affirms that decentralising expenditure responsibilities without reducing the bureaucracy around revenue autonomy may make it difficult for counties to provide accessible and good quality public services. This matches previous studies that have showed devolved governments increasingly relying on locally raised revenues to supplement fiscal transfers (Xu and Warner 2016), and that decentralising expenditure responsibilities without adequate revenue autonomy may actually worsen the accessibility and quality of public services, as found in Asia and Latin America (Sujarwoto 2017).

A related Kenyan study on three county hospitals found that the legal structures that accompanied the decentralisation of expenditure responsibilities to the counties had reduced the autonomy of county hospitals over critical functions such as finance and human resources. This resulted in weakened hospital management, leading to compromised quality of care and unavailable services (Barasa et al. 2017).

Borrowing

The data suggests that devolution of full borrowing powers to the Kenyan counties might portend economic disaster due to unbridled spending. Several respondents highlighted the problem of pending bills due to over-expenditures by county governments and revenue leakages through corruption. They argued that if counties cannot be trusted to spend the money they receive from fiscal transfers and own-source revenues wisely, they cannot be entrusted with uncontrolled borrowing. One representative from the non-government organisations, had this to say:

…counties end up over-borrowing from commercial banks to cover for… their inefficiency in collecting revenue and to cover up their corruption.

Thus, counties are seen to borrow excessively to meet the cost of corruption, in addition to plugging budget deficits brought about by their inefficiency in collecting local revenues. This view is supported by critics who argue that decentralising borrowing powers could lead to macroeconomic instabilities as devolved governments’ fiscal policies may run counter to those of the national government (Prud’homme 1995; Xu and Warner 2016).

On the other hand, a similar number of respondents blamed deteriorating public services on the cumbersome procedures counties face when borrowing, arguing that simplifying the procedures would enable counties to borrow money to plug service delivery gaps and provide seamless services. This position is supported by studies that show decentralisation of expenditure responsibilities and revenue autonomy alone do not improve public services in the absence of borrowing powers that enable devolved governments to mobilise resources to meet service delivery goals (Salinas and Sole-Olle 2018; Diaz-Serrano and Meix-Llop 2019). Studies carried out in both developed countries and the developing countries of Asia and Latin America show that those that have devolved expenditure responsibilities, revenue autonomy and borrowing powers have reported improvements in the accessibility and quality of public services (Arce and Hendricks 2019; Hao et al. 2020). Similarly, studies in China have shown that devolution of expenditure responsibilities and revenue autonomy without borrowing powers reduces the quality of primary education services and, more broadly, the accessibility of devolved services at the municipal level (Hess 2020; Hao et al. 2020).

Positive deviance

Despite the widespread perceptions among respondents of ineffective oversight and institutional corruption, this study also found evidence of positive deviance, within Nairobi City county. One respondent (a member of the public) reported:

Since these people of NMS [Nairobi Metropolitan Services] started running Nairobi, we have seen good things. Their service is high level. They have brought improvements in cleanliness, roads and hospitals have been built, and there is medicine. Even in the slums, we have hospitals, and cleanliness has improved, and roads are being built.

This points to NMS as an example of successful implementation of fiscal decentralisation, despite facing similar challenges to those faced by the Nairobi City government before the transfer of functions. NMS was created in March 2020 through an agreement between the national government and Nairobi City, whereby four core functions – county health services; transport; public works, utilities and ancillary services; and physical planning and development – were officially transferred to the national government (Nairobi Metropolitan Services 2023). The new entity was unique as it operated under the executive office of the president and was fully empowered in that way through an executive order. It was also unique in institutional terms as it was a civilian organisation under military leadership. The director general was a lieutenant general, assisted by several military personnel who occupied the top management positions. In the context of positive deviance theory, NMS would be viewed as a powerful change agent, from which other counties could learn. This confirms previous studies in Kenya where some counties (for example, Makueni) have been lauded as models of successful implementation of fiscal decentralisation and used for benchmarking (Wagana 2017). Fiscal decentralisation may not solve the problem of poor service delivery which plagues most countries in Africa without more examples of positive deviance in devolved systems to act as ‘game changers’ and demonstrate new ways forward (Diaz-Serrano and Meix-Llop 2019).

Discussion

In contrast to centralised fiscal systems that have long been blamed for having bureaucratic layers that cause inefficiencies in public service delivery, fiscal decentralisation through devolved expenditure responsibilities, revenue autonomy and borrowing powers has been cited as the means to achieve improved public services in countries such as Chile and Nepal, and has often been recommended to African countries that are struggling with service delivery (Olowu and Wunsch 2004; Okolo and Akpokighe 2014; Finch and Omolo 2015; Adamtey et al. 2020).

Although the views of the respondents in this Kenyan study suggest that fiscal decentralisation within the two selected counties has not improved public service delivery, it must be noted that Kenya has only devolved specific expenditure responsibilities through fiscal transfers, and that the counties have faced cumbersome procedures when exercising their revenue autonomy and borrowing powers (Wagana 2017). Previous studies on the exercise of devolved expenditure responsibilities by Kenyan counties have reported mixed, rather than uniformly negative, results in terms of the accessibility and quality of public services (Mbau et al. 2020).

Contextual factors play an important role in the relationship between fiscal decentralisation and public service delivery. In terms of social learning theory and institutional theory, cultural values, belief systems and the pressure to conform have been carried over from the previous local authorities to the new counties. As a result, excessive bureaucratic procedures have been retained and financial resources that were decentralised have been utilised to employ more staff and set up more bureaucratic structures. This has led to a bloated workforce, which has increased the cost of public services. In the same vein, the cultural value of creating additional jobs even when they are not necessary, and the pressure to conform to what other counties are doing in terms of employing more staff and creating more bureaucratic structures, has adversely affected public service delivery.

This position supports the view of fiscal decentralisation critics who argue that decentralisation of expenditure responsibilities leads to wastage of scarce financial resources (Hess 2020). These critics posit that economies of scale are lost when money is transferred to local authorities and the central government can no longer procure services and goods in bulk and get cheaper rates, an approach which promotes accessible and quality public services (Novi et al. 2019). Others argue that the management and provision of public services becomes fragmented amongst devolved governments as more bureaucratic layers are added, thus increasing costs of service provision. Moreover, they posit that decentralisation of expenditure responsibilities can lead to significant inequalities in service provision due to the differing approaches of independent governments, making policy coordination among levels of government more difficult (Kyriacou and Roca-Sagales 2019). Scholars such as Remy Prud’homme are doubtful that benefits of production efficiency are indeed realised when fiscal decentralisation is implemented, as the real challenge lies in organising for the joint production of a service, and believes more research is needed in this area (Prud’homme 1995).

It appears that decentralisation of expenditure responsibilities and revenue autonomy may improve the quality and accessibility of public services but only under certain conditions (Salinas and Sole-Olle 2018). These conditions include a sufficient level of funding and/or revenue autonomy that would enable the devolved governments to mobilise resources to meet public service delivery goals (Novi et al. 2019; Diaz-Serrano and Meix-Llop 2019). This view is supported by studies of partially devolved expenditure responsibilities in Spain, which showed that the accessibility and quality of educational services improved with devolution, but the effects were much stronger for regions that had devolved both expenditure responsibilities and adequate powers to raise revenues (Salinas and Sole-Olle 2018). Other studies point to the need to combine a sufficient degree of revenue autonomy and borrowing powers with a suitably enabling political and institutional environment (Kyriacou and Roca-Sagales 2019).

Conclusion

The findings of this study confirm that fiscal decentralisation does not automatically lead to improved public services. On the one hand, decentralisation of expenditure responsibilities in Kenya’s Kiambu county has yet to make a positive impact on public service delivery there, while on the other Nairobi Metropolitan Services offers an example of positive deviance that has led to improved services in certain functions in Nairobi City – albeit under an arms-length central government agency rather than a devolved sub-national government.

The findings also reveal that corruption increased the cost of providing services and made them less affordable to citizens, due to lack of accountability and weak oversight of financial management by the county assemblies. Cumbersome bureaucratic practices inherited from the former local authorities or imposed by central government were another key factor in increasing costs.

Views on decentralisation of borrowing powers were mixed, as some respondents felt it could lead to uncontrolled spending at the county level and increase corruption, while others blamed the lack of appropriate borrowing powers for the counties’ inability to provide better services.

At the conceptual level, the framework adopted for this study enables us to make connections between the various indicators of fiscal decentralisation (expenditure responsibilities, revenue autonomy and borrowing powers) and their relationship with public service delivery (in terms of quality of services as indicated by their affordability). The framework has highlighted the importance of the moderating factors that impact this relationship: institutional practices, cultural values, legal structures, belief systems, pressure to conform and change agents. Interrogation of these variables and their relationships was facilitated by applying institutional, positive deviance and social learning theories. The authors recommend further empirical studies to establish how fiscal decentralisation has been theoretically and practically constructed within Kenyan counties, the different contexts in which it has been implemented, and how such construction and contexts explain variations in the levels of service delivery to the public. There is also a pressing need to focus on Africa, as the available literature is skewed towards developed western countries and developing countries in Latin America and Asia (Sujarwoto 2017). In addition, more research is required to explore dimensions of quality in public services, as the current literature dwells largely on accessibility (typically defining it as affordability) (Wagana 2017). Further studies could also do more to incorporate moderating variables such as corruption when interrogating the relationship between fiscal decentralisation and service delivery (Alfano et al. 2019). Finally, since the current epistemology is skewed towards a positivist tradition, the authors call for more qualitative studies, especially longitudinal studies, case studies and ethnographic approaches, to enrich knowledge in this field.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship or publication of this article.

References

Adamtey, R., Sarpong, E.T. and Obeng, G. (2020) A study towards deepening fiscal decentralization for effective local service delivery in Ghana. Final Research Report, Good Governance Africa.

Alfano, M.R., Baraldi, A.L. and Cantabene, C. (2019) The effect of fiscal decentralisation on corruption: a non-linear hypothesis. German Economic Review, 20 (1), 105–128. https://doi.org/10.1111/geer.12164

Andersen, J.J., Johannesen, N. and Rijkers, B. (2020) Elite capture of foreign aid: evidence from offshore bank accounts. Washington DC: World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-9150

Arce, M. and Hendricks, M. (2019) Resource wealth and political decentralisation in Latin America. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics, 30 September. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.1661

Arends, H. (2020) The dangers of fiscal decentralization and public service delivery: a review of arguments. Polit Vierteljahresschr, 61, 599–622. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11615-020-00233-7

Banerjee, E.S., Herring, S.J., Hirley, K., Puskarz, K., Yeberpetsky, K., LaNoue, M. (2018) Determinants of successful weight loss in low income African American women: a positive deviance analysis. Journal of Primary Care and Community Health, 1 (6). https://doi.org/10.1177/2150132718792136

Barasa, E.W., Manyara, A.M., Molyneux, S. and Tsofa, B. (2017) Recentralisation within decentralisation: county hospital autonomy under devolution in Kenya. PLOS ONE, 12 (8). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0182440

Baxter, R., Taylor, N., Kellar, I. and Lawton, R. (2016) What methods are used to apply positive deviance within healthcare organisations? A systematic review. BMJ Quality & Safety. 25. 190–201. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004386

Berthod, O. (2018) Institutional theory of organisations. In: Farazmand, A. (eds.) Global encyclopedia of public administration. public policy and governance, (pp. 3306–3310). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20928-9_63

Blöchliger, H. and Akgun, O. (2018) Fiscal decentralisation and economic growth. In: Kim, J. and Dougherty, S. (eds.) Fiscal decentralisation and inclusive growth. OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264302488-4-en

Boone, C., Dyzenhaus, A., Manji, A., Gateri, C.W., Ouma, S., Owino, J.K., Gargule, A., Klopp, J.M. (2019) Land law reform in Kenya: devolution, veto players, and the limits of an institutional fix. African Affairs, 118 (471), 215–237. https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/ady053

Chigwata, C. (2017) Fiscal decentralisation: constraints to revenue-raising by local government in Zimbabwe. In: Schoburgh, E. and Ryan, R. (eds.) Handbook of research on sub-national governance and development, (pp. 218–240). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-1645-3.ch010

Diaz-Serrano, L. and Meix-Llop, E. (2019) Decentralisation and the quality of public services: cross-country evidence from educational data. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 37 (7), 1296–1316. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654418824602

Dunlop, C.A. and Radaelli, C.M. (2019) Regulation and corruption: claims, evidence and explanations. In: Massey, A. (ed.) A research agenda for public administration, (pp. 97–113). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. Elgaronline.com. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781788117258.00012

Finch, C. and Omolo, A. (2015) Building public participation in Kenya’s devolved governments. Nairobi: Kenya School of Government, Centre for Devolution Studies.

Fonshell, J. (2018) Corruption devolved: people’s perceptions on devolutions impact on transparency, accountability and service delivery by the Government of Kisumu County, Kenya. Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 2815. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/2815

Garduno, L. (2019) Explaining police corruption among mexican police officers through a social learning perspective. Deviant Behavior, 40 (5), 602–620. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2019.1593293

Gustafsson, M. and Scurrah, M. (2019) Strengthening subnational institutions for sustainable development in resource-rich states: decentralised land-use planning in Peru. World Development, 119, 133–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.03.002

Hao, Y., Chen, Y.F., Liao, H. and Wei, Y.M. (2020) China’s fiscal decentralisation and environmental quality; theory and empirical study. Environment and Development Economics, 25 (2), 159–181. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355770X19000263

Hess, S. (2020) Plunder and paradiplomacy: the corruption of China’s decentralised state in Yunnan Province. China. An International Journal, 18 (2), 77–98. https://doi.org/10.1353/chn.2020.0017

Kaburu, F.N. (2013) Fiscal decentralisation in Kenya and South Africa: a comparative analysis. Africa Nazarene University Law Journal (ANULJ), 1 (1),76–106.

Khamisi, J. (2018) Kenya: looters and grabbers: 54 years of corruption and plunder by the elite, 1963-2017. Texas. USA: Jodey Book Publishers.

Kyriacou, A.P., Muinelo-Gallo, L. and Roca-Sagales, O. (2017) Regional inequalities, fiscal decentralisation and government quality. Regional Studies, 51 (6), 945–957. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2016.1150992

Kyriacou, A.P. and Roca-Sagales, O. (2019) Local decentralisation and the quality of public services in Europe. Social Indicators Research, 145, 755–776. . https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-019-02113-z

Lammers, J.C. and Garcia, M.A. (2017) Institutional theory approaches. In: Scott, C.R., Barker, J.R., Kuhn,T., Keyton, J., Turner, P.K. and Lewis, K.L. (eds.) The international encyclopedia of organisational communication. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118955567.wbieoc113

LeMahieu, P.G.L., Nordstrum, L.E. and Gale, D. (2017) Positive deviance: learning from positive anomalies. Quality Assurance in Education, 25 (1), 109–124. https://doi.org/10.1108/QAE-12-2016-0083

Martinez-Vazquez, J., Lago-Penas, S. and Sacchi, A. (2017) The impact of fiscal decentralisation: a survey. Journal of Economic Surveys, 31 (4), 1095–1129. https://doi.org/10.1111/joes.12182

Mbau, E.P., Iraya, C.M., Mwangi, M. and Njihia, J.M. (2020) An empirical study on the moderating effect of public governance on the relationship between fiscal decentralisation and performance of county governments in Kenya. Journal of Finance and Investment Analysis, 9 (2), 37–58.

Muna, W.K. (2016) Fiscal decentralization in Kenya: an analysis of the implementation of the constituency development fund in the Naivasha and Gatanga constituencies. PhD Thesis, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa. Available at: https://researchspace.ukzn.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10413/13512/Muna_Wilson_Kamau_2016.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [Accessed 4 April 2022].

Mwangi, J., Muna, W., Naituli, G. (2022) Corruption in public awareness and public service delivery: evidence and lessons from County Governments in Kenya. Strategic Journal of Business and Change Management, 9 (2).

Nairobi Metropolitan Services. (2023) About NMS – mandate and functions of Nairobi Metropolitan Services. Available at: https://www.nms.go.ke/?page_id=11 [Accessed 12 July 2023].

Novi, C.D., Piacenza, M., Robone, S. and Turati, G. (2019) Does fiscal decentralisation affect regional disparities in health? Regional Science and Urban Economics, 78 (C). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2019.103465

Okolo, P.O. and Akpokighe, O.R. (2014) Federalism and resource control: the Nigerian experience. Public Policy and Administration Research, 4 (2), 99–109.

Olowu, D. and Wunsch, J.S. (2004) Local governance in Africa: the challenges of democratic decentralization. Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Oluoch, V. (2016) Impact of corruption and bad governance on Kenya’s National Security. Institute of Diplomacy and International Studies, University of Nairobi. Available at: https://paperzz.com/doc/7957130/impact-of-corruption-and-bad-governance-to-kenya-s-national [Accessed 12 July 2023].

Otieno, D.C. (2018) Corruption risk mapping report. [Online] Available at: https://www.cipe.org/resources/corruption-risk-mapping-in-kenyas-private- [Accessed 12 July 2023].

Peterson, M.J. and Peters, B.G. (2020) Institutional theory and method. In: Curini, L. and Franzese, R. (eds.) Sage handbook of research methods in political science. Sage Publishers. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526486387.n13

Prud’homme, R. (1995) Dangers of decentralization. World Band Research Observer, 10 (2), 201–210. https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/10.2.201

Salinas, P. and Sole-Olle, A. (2018) Partial fiscal decentralisation reforms and educational outcomes: a difference-in-differences analysis for Spain. Journal of Urban Economics, 107, 31–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2018.08.003

Scott, W. (2013) Institutions and organisations: ideas, interests, identities. London: Sage.

Sujarwoto, S. (2017) Why decentralisation works and does not work. Journal of Public Administration Studies, 1 (3), 1–10.

Wagana, D.M. (2017) Effect of governance decentralisation on service delivery in county governments in Kenya. PhD Thesis, Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology.

Xu, Y.S. and Warner, M.E. (2016) Does devolution crowd out development? A spatial analysis of US local government fiscal effort. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 48 (5), 871–890. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X15622448