Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance

Issue 26

May 2022

RESEARCH AND EVALUATION (PEER REVIEWED)

Assessing the Impact of Sporting Mega-Events on the Social and Physical Capital of Communities in Host Cities: The Gold Coast 2018 Commonwealth Games Experience

Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney, PO Box 123, Broadway,

NSW 2007, Australia, michael.falla@student.uts.edu.au

Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney, PO Box 123, Broadway,

NSW 2007, Australia, jason.prior@uts.edu.au

Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney, PO Box 123, Broadway,

NSW 2007, Australia, brent.jacobs@uts.edu.au

Corresponding author: Michael Falla, Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney, PO Box 123, Broadway, NSW 2007, Australia, michael.falla@student.uts.edu.au

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi26.7683

Article History: Received 15/04/2021; Accepted 02/04/2022; Published 31/05/2022

Citation: Falla, M., Prior, J., Jacobs, B. 2022. Assessing the Impact of Sporting Mega-Events on the Social and Physical Capital of Communities in Host Cities: The Gold Coast 2018 Commonwealth Games Experience. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, 26, 5–27. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi26.7683

© 2022 by the author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

(CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties

to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the

material for any purpose, even commercial, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Abstract

Over the past decade there has been increasing research on how sporting mega-events such as the Olympic and Commonwealth Games are developing strategies, norms and rules to govern how they impact the host nation, city and communities, and in particular their impacts on economic, social, physical, human and cultural capital. This paper addresses a gap within these interconnected fields by examining how the strategies, norms and rules used to govern a mega-event may impact the social and physical capitals of communities in the host city during and following a mega-event. These associations are revealed through a novel methodology that combines the Institutional Grammar Tool developed by Crawford and Ostrom and the Community Capitals Framework devised by Flora and Flora, to analyse policy documentation, complemented by 11 in-depth interviews on the refurbishment of the Broadbeach Lawn Bowls Club as a venue for the 2018 Commonwealth Games in the City of Gold Coast, Australia.

Keywords

Mega-Event; Social and Physical Capitals; Governance; Community Impact; Commonwealth Games

Introduction

For this study sporting mega-events are defined by their scale, the size of their audience, the type of infrastructure they require, and their frequency (Hiller 1999; Kruger and Heath 2013; Horne 2015; What Culture 2017).

The study presented here builds on two related areas of research. The first examines the strategies, norms and rules – hereafter called ‘institutions’ – developed to guide how mega-events are managed and in turn impact on host countries, cities, communities and the wider environment. These institutions have emerged, in part, as a response to an increasing awareness of the positive and negative impacts of mega-events (Chalkley and Essex 1999; Tziralis et al. 2008; Hoff et al. 2020).

The second area of research examines how mega-events affect the physical capital (PC) and social capital (SC) of host communities. To date, few studies have examined capital impacts at the community level within a host city (Prior and Blessi 2012; Horne 2015; Santos et al. 2017). This study addresses that gap by examining the associations between the various ways a set of strategies, norms and rules are used to guide how mega-events impact the SC and PC of communities in the host city, both during and following the mega-event. These associations are revealed through a novel case study approach that uses the Institutional Grammar Tool (IGT), developed by Crawford and Ostrom (1995, 2005), and the Community Capitals Framework (CCF) (Flora and Flora 2008) to analyse policy documents, together with 11 in-depth interviews, related to the refurbishment of the Broadbeach Lawn Bowls Club (BLBC) to prepare it as a venue for the 2018 Commonwealth Games held in the City of Gold Coast, Australia. The focus on PC and SC stems from the claims of Games proponents about the impact of investment in local venues (Commonwealth Games Federation (CGF) 2020b) – in this case the physical infrastructure of the BLBC (ie PC) and its role as a hub for social activities (ie SC). The IGT provided a means of identifying and coding the institutions that governed the Games, and the CCF provided a means for understanding the impact on PC and SC. Documentary analysis and interviews identify both written and unwritten institutions that influenced how the Games affected the PC and SC of the local community.

The study developed a conceptual framework to guide its research. This framework is described in the next section, followed by an overview of the methodology and findings. The paper concludes with a discussion of the implications for the future governance of mega-events and local communities, an outline of the study’s limitations, and recommendations for future research.

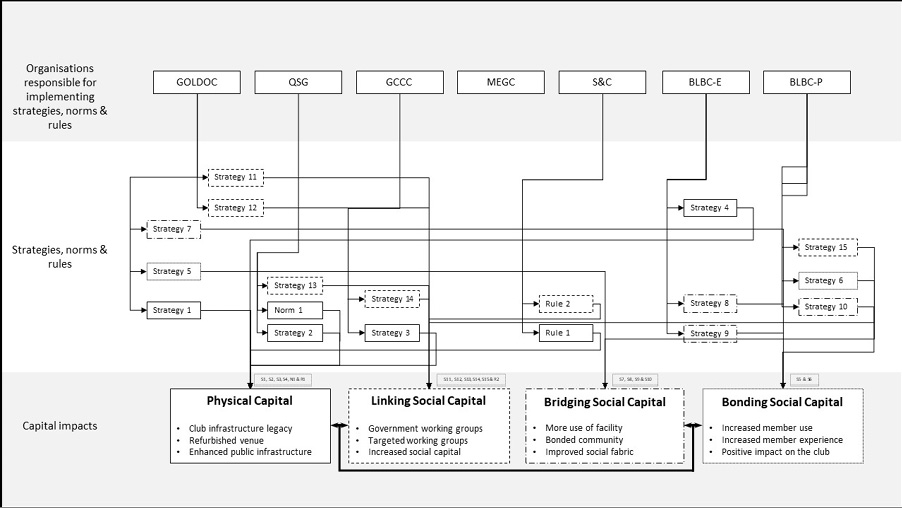

Conceptualising institutions and community capital

The study’s conceptual framework has two key dimensions: the institutions that are used to guide the implementation of sporting mega-events, and how the implementation of these institutions affects the capital of a community within the host city. Societal institutions, some specifically related to sporting mega-events and others operating more broadly, guide the ways in which mega-event funding, processes and policies are implemented. These factors affect the community capital of the host city, both during and following the mega-event (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Conceptualising institutions and community capital

Dimension 1: institutions and governance

Sporting mega-events take many years to plan and implement (Preuss 2015). These preparations are guided by complex governance systems that involve all levels of government and volunteers from local communities (Bovy 2013), and they involve a complex array of institutions.

This paper uses the IGT developed by Crawford and Ostrom (1995, 2005) to identify institutions that guided the 2018 Commonwealth Games process and, as a case study, the refurbishment of the BLBC (Dunlop et al. 2019; Gold Coast Commonwealth Games Corporation (GC) 2018a, 2018b). The IGT provides a language that can be used to identify institutions operating across complex governance systems such as those that are used to implement sporting mega-events, and to help reveal the structures of the systems involved, such as policy frameworks and procurement guidelines (McGinnis 2011; Basurto et al. 2011). Whilst the IGT has been shown to require a significant degree of competency and a specific coding method to derive meaningful data (Basurto et al. 2011; Lien 2020; Frantz and Siddiki 2020), it is also considered to be comprehensive and flexible, allowing for different levels of coding and expression (Frantz and Siddiki 2020). This study adopted a similar process of coding analysis to that of Prior (2016), which innovatively applied the IGT to interviews to analyse the institutions driving sustainable remediation of contaminated environments.

Within the IGT, key components of institutions are broken down into elements of a grammatical syntax known as ‘ADICO’: performer, also known as attribute (A), deontic (duty or obligation) (D), aim (I), condition (C) and or else (O) (Crawford and Ostrom 1995: Cooper 2016). Table 1 explains each component of the syntax in the sentence, ‘[The student] [must] [write paper] [by date], [or receive a lower final grade]’ (Basurto et al. 2011).

Text source: Basurto et al. (2011)

Different combinations arising out of this syntax form strategies, norms and rules. A strategy consists of a performer, an aim and a condition (AIC). A norm consists of those three components and the deontic (ADIC), while a rule needs to include the entire syntax, ADICO (Crawford and Ostrom 1995).

Whilst strategies can be created and implemented by one performer, norms and rules exist within mega-event decision-making only if they engender some collective understanding among participants: for example, more than one participant group being aware of a norm or rule (Crawford and Ostrom 1995). Norms and rules may not be exclusive to mega-event processes and may be shared across society. Good examples are laws and ordinances (Ostrom 2005; Lien 2020).

Several studies have shown that the institutional grammar described here can be used to analyse written legislation, regulations and policies (Basurto et al. 2011; Carter et al. 2015; Lien 2020). The approach was specifically designed to enable the collection of both formally documented institutions eg those found in guidelines, policies and implementation planning), and others that may only be shared by common understanding, such as a shared norm that is commonly understood and guides behaviour, but is not written down (Prior 2016).

Dimension 2: community capital

In this study we understand community to be both physical and social. As Flora et al. (2016) explain, a community provides a geographically defined locality, and the way people interact in that locality shapes its institutions. This study adopts a common conceptual language for capitals using the Community Capitals Framework (CCF) devised by Flora and Flora (2008). According to Washington State University (2011, p. 1):

[The CCF offers] us a new viewpoint to analyse holistic community changes. The framework encourages us to think systematically about strategies and projects, thus offering insights into additional indicators of success as well as potential areas of support.

Assessing changes in community capital can be a useful approach in the planning and assessment of a wide array of initiatives. Furthermore, an examination of the impact of investment in one type of capital on other types can reveal unintended consequences (Emery and Flora 2006). The CCF comprises seven classes of community capital: natural, cultural, human, social, political, financial and physical (built) (Washington State University 2011). Of interest to this study are PC (physical capital) and SC (social capital), the impacts of investment on these two types of capital, and their interactions at the local scale. An examination of these factors helps us to judge whether claims that the Games would improve the SC of the city’s communities were borne out. For this mega-event, public money was used to develop PC amid claims that it would enhance the city (CGF 2020a; GC 2018a). The present study was interested in understanding whether the physical refurbishment of a social hub enhanced the social dimensions of the surrounding environment.

SC has been defined as “connections among individuals – social networks and the norms of reciprocity and trustworthiness that arise from them” (Putnam 2001, p. 19). This study distinguishes between various types of SC, particularly bridging and bonding. Bridging SC refers to the social connections that cut across narrow groups and interests, connecting people in a community (Putnam 2000). Bonding SC refers to social connections that strengthen and perpetuate cohesion within particular groups, sometimes at the expense of cross-cutting social interactions, and thus reinforce exclusive identities and homogeneous groups (Putnam 2000). Woolcock (2001) argues that it is important to recognise a third key dimension of SC, linking SC, which refers to the relations within the hierarchical structures of society (Woolcock 2001). Linking SC may be provisionally viewed as a special form of bridging SC that concerns power – it is a vertical bridge across the asymmetrical distribution of power and resources. This paper treats bridging, bonding and linking SC as components of a common syntax for SC.

PC is the process by which a city invests in its physical infrastructure (Perry 1995). In this study, ‘infrastructure’ refers to physical facilities that form a systematic network (OECD 1991; Perry 1995).

Utilising the conceptual framework outlined above, the study aims to address two related research questions:

RQ1: What norms, rules and strategies guide how mega-events impact the PC and SC of the communities in the host city, both during and following the mega-event?

RQ2: How do mega-events impact the SC and PC of these communities, and how are the strategies, norms and rules associated with these impacts?

Methodology

As noted earlier, the study combined the IGT and CCF to explore how institutions within the 2018 Commonwealth Games guided SC and PC impacts in the Gold Coast local community through refurbishment of the BLBC. Table 2 provides an overview of the three-part methodology. The first part involved selecting BLBC as a case study; the second involved collecting and processing documents and interview data about the refurbishment; the third involved analysing this data using the IGT and CCF to address the research questions.

| Steps | Methodology | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Case study selection | Based on the following factors:

|

| Step 2 | Data collection | Types of data collected:

|

| Step 3 | Data analysis | Data analysis tools used to interpret the data:

|

Selection and overview of case study

The case study was selected based on both pragmatic reasoning (accessibility to data) and the definitional criteria for mega-events. The Gold Coast 2018 Commonwealth Games was chosen because it occurred in the researchers’ home country, and because the lead researcher was employed within the Games’ organising structure and had access to documentation on procurement, infrastructure planning and development processes.

The role of the Commonwealth Games Federation (CGF) is to direct and control the Games. It oversees the implementation of the Games every four years in a different host country. Once a mega-event is awarded, the host nation and city form an organisation tasked with designing, planning, and delivering the Games as set out in their bid document (CGF 2020a). The Gold Coast 2018 Commonwealth Games Corporation (‘GOLDOC’) was established in January 2012 and disbanded after the Games.

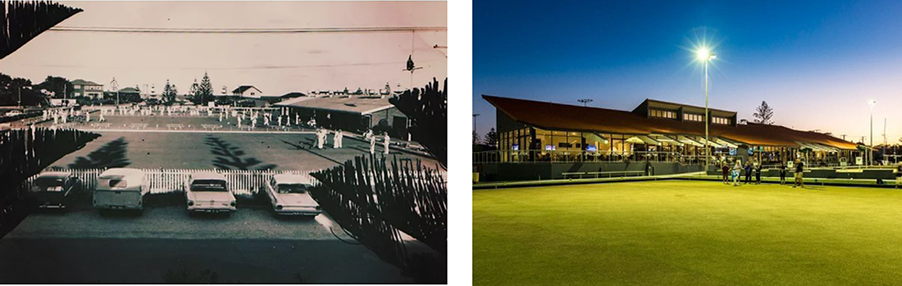

A total of 6,600 athletes from 70 nations participated in the Games, which took place at 18 venues over 11 days of competition across 23 sports (GC 2018b). One of the venues was the BLBC, which has hosted some of the biggest lawn bowls events in the world, but also maintains its accessibility to the public. The BLBC is located in the north of the suburb of Mermaid Beach-Broadbeach which has a population of 13,641 residents and a land area of 3 square kilometres, and is located in the centre of Gold Coast City which has a population of 643,461 residents and land area of 1,334 square kilometres (GCCC, 2021). The BLBC’s clubhouse was constructed in 1954, and until its replacement in 2016 the building had remained little changed. The venue’s refurbishment also included the construction of four international- standard greens (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. BLBC before (1954, left) and after (2018, right) the Games

Photo by Broadbeach Bowls Club (2020) (left). Photo by Australian Leisure Management (2020) (right)

Data collection

Data collection involved collating documents and conducting semi-structured interviews. Seventeen documents were used in the analysis and are available on the Gold Coast Commonwealth Games website (GC 2018c), and included guidelines and policies developed for the Games (Table 3).

Interviews were conducted on the Gold Coast during December 2019. The interviewees were: two former employees of the Games Organising Committee (GOLDOC1-2); two Gold Coast City Council employees (GCCC1-2); a mega-events games consultant (MEGC1); one BLBC executive (BLBC-E1); and five BLBC patrons (BLBC-P1-5), giving a total of 11 interview participants. Interviews lasted from 25 to 45 minutes.

The focus of the interviews was how the participants viewed the Games, and the impacts that the Games had on the local community of Broadbeach before, during and after the event.

The interviews included:

• general questions about the BLBC and the Games

• questions about institutions operating within the BLBC

• questions related to physical and social changes within the BLBC.

Data analysis

The data were systematically coded using the IGT and CCF. To maintain consistency, a single researcher coded data from both the documents and interviews. The coding process and outcomes were reviewed by two researchers who had previously used the IGT and CCF, a recognised good practice measure (Jacobs and Brown 2014; Prior 2016). The focus of the IGT coding was the identification of institutions related to PC and SC that were associated with the refurbishment of the BLBC. The focus of the CCF coding was the identification of the PC and SC of the BLBC and its communities during and following the mega-event. SC impacts were further broken down into three sub-categories: bonding, bridging and linking SC.

The steps used to code the documents and transcribed interviews were:

1. References to bonding SC, bridging SC, linking SC and PC were coded.

2. The names of the participants were replaced with codes for their performer types: 1. Gold Coast 2018 Commonwealth Games (GOLDOC), 2. Queensland State Government (QSG), 3. Gold Coast City Council Employees (GCCC), 4. Mega-Events Games Consultant (MEGC), 5. Suppliers and Contractors (S&C), 6. Broadbeach Lawn Bowls Club Executives (BLBC-E), and 7. Broadbeach Lawn Bowls Club Patrons (BLBC-P).

3. The IGT grammatical syntax was used to code strategies, norms and rules related to the different types of capital. This involved the following steps:

i) Aims performed were coded.

ii) The deontic associated with each aim was coded: must, must not, or may, either explicit or implicit (eg the verb ‘required’ or ‘shall’ suggests a ‘must’).

iii) Formal sanctions were coded for each aim, as were conditions.

iv) The IGT syntax, based on the presence of associated components (eg deontic or sanction) was then coded as a strategy, norm or rule.

v) The 87 identified strategies, norms and rules captured from audio transcripts and documents were further analysed, and duplicate/similar strategies, norms and rules were removed or grouped. Fifteen strategies, two rules and one norm remained after this process (see Tables 4 and 5). Rules and norms were recorded only if two or more performer holder groups identified them.

vi) Strategies, norms and rules that emerged from the coding were then nested into four categories: bonding SC, bridging SC, linking SC and PC.

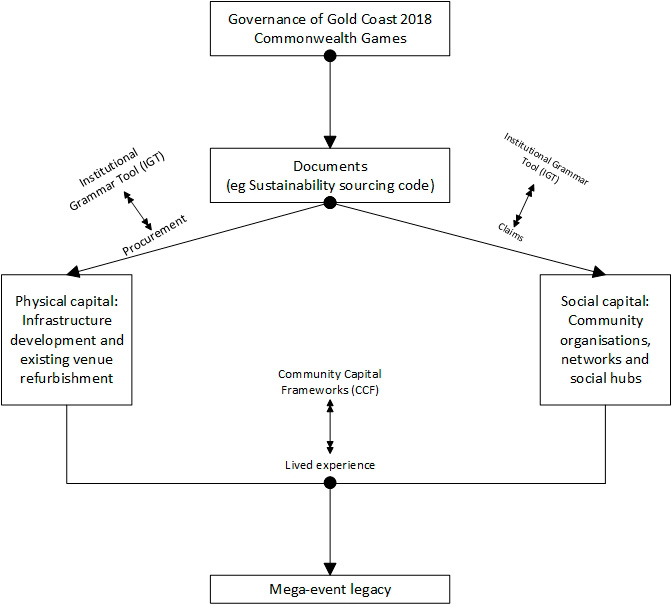

Findings

RQ1: What norms, rules and strategies guide how mega-events impact the PC and SC of the communities in the host city, both during and following the mega-event?

Table 4 shows the institutions for each of the Games organisations, associated with a type of capital. Of the 18 institutions, six governed PC, while six governed linking SC, four bridging SC and two bonding SC. Among the types of institutions, strategies were most common across PC and SC. The analysis also revealed that responsibility for institutions was relatively evenly spread across all organisations examined, except for MEGC. GOLDOC and BLBC-E were responsible for governing marginally more of the institutions. MEGC and BLBC-P were not responsible for institutions related to PC, reflecting their limited roles in the governance of infrastructure. BLBC-E and BLBC-P guided the two institutions associated with bonding SC, and three of the four institutions that governed bridging SC. Responsibility for the institutions associated with linking SC resided mainly with GOLDOC, QSG and GCCC – the organisations at the upper levels of the Games hierarchy.

| Frequency of units | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical capital | Bonding social capital | Bridging social capital | Linking social capital | Total | |

| Institutions identified: | |||||

| Strategies | 4 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 15 |

| Norms | 1 | - | - | - | 1 |

| Rules | 1 | - | - | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 6 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 18 |

| Performers of institutions: | |||||

| Gold Coast 2018 Commonwealth Games (‘GOLDOC’) | 1 | - | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| Queensland State Government (QSG) | 2 | - | - | 1 | 3 |

| Gold Coast City Council (GCCC) employees | 1 | - | - | 1 | 2 |

| Mega-Events Games Consultant (MEGC) Suppliers and Contractors (S&C) | - 1 | - - | - - | - 1 | - 2 |

| Broadbeach Lawn Bowls Club Executive (BLBC-E) | 1 | 1 | 2 | - | 4 |

| Broadbeach Lawn Bowls Club Patrons (BLBC-P) | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Total | 6 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 18 |

Table 5 provides details of the ADICO grammar for each of the institutions, categorised by types of capital. Four organisations had strategies relating to PC: GOLDOC, QSG, GCCC and BLBC-E (Table 5, Strategies 1–4). Strategies 1, 2 and 4 refer to the creation of legacy through infrastructure development. Strategy 3 refers to prioritisation of planning by GCCC.

* Gold Coast 2018 Commonwealth Games (GOLDOC), Queensland State Government (QSG), Gold Coast City Council (GCCC) employees, Mega-Events Games Consultant (MEGC), Suppliers and Contractors (S&C), Broadbeach Lawn Bowls Club Executive (BLBC-E) and Broadbeach Lawn Bowls Club Patrons (BLBC-P).

One norm (Table 5, Norm 1) was used by QSG for PC in the form of a commitment by the government to build infrastructure for the mega-event that would benefit local communities after the Games.

A formal rule (Table 5, Rule 1) was used for SC by GOLDOC. It imposed timeframes and quality controls on those carrying out the development of community facilities.

Two organisations had strategies for the development of bonding SC related to venue refurbishment. GOLDOC’s Strategy 5 and BLBC-P’s Strategy 6 (Table 5) aimed at establishing an environment where people were “thriving” and “having a good time” in the BLBC (BLBC-P4). As the people most likely to benefit under this strategy would be club members, it is categorised as contributing primarily to bonding SC, although non-member club users also benefited.

Four strategies (Table 5, Strategies 7–10) related to bridging SC. Three organisations were responsible for these strategies: GOLDOC, BLBC-E and BLBC-P. Strategy 7 relates to GOLDOC’s aim to increase international visitor traffic to the Gold Coast for the Games. Strategies 8–10 (BLBC-E and BLBC-P) refer to the benefits of refurbishing facilities at the bowls club so that it could better serve regional visitors during the Games and the local community subsequently, through the creation of new services.

Five strategies and one rule (Table 5, Strategies 11–15, Rule 2) related to linking SC were established through five organisations (GOLDOC, QSG, GCCC, BLBC-P and S&C). These strategies are categorised as linking SC since they describe social and economic benefits for the local community (GCCC, BLBC-P and S&C) sought through relationships with the Games’ governing hierarchy (ie GOLDOC and QSG) and venue refurbishment. Strategies 11 and 13 refer to building a more robust local economy. Strategies 12 and 15 refer to legacy benefits from the Games, and Strategy 14 refers to ensuring successful infrastructure delivery and community benefits. Rule 2 sought to ensure compliance when suppliers and contractors engaged with GOLDOC.

RQ2: How do mega-events impact the SC and PC of these communities, and how are the strategies, norms and rules associated with these impacts?

All participants reported impacts on PC and the three forms of SC for the BLBC and the local community. They attributed these impacts, at least in part, to the institutions – strategies, norms and rules – detailed in Table 5 above. Figure 3 presents an overview of the associations between the institutions discussed and the different types of PC and SC generated for the BLBC and local community. It also highlights those organisations responsible for governing each institution. GOLDOC, QSG and GCCC account for ten of the 18 institutions that participants indicated had tangible impacts on the PC and SC of the BLBC and local community. The MEGC did not guide any institutions, which implies that it had no direct impact on the PC and SC of the BLBC and local community.

Figure 3. Associations between the organisations governing institutions, their impact on the PC and SC of the BLBC and local community, and the interactions between institutions and capitals

What follows is a detailed description of the Games’ impact on the PC and SCs of the BLBC and the local community as reported by the participants, and the association between those impacts and the institutions.

Physical capital

The participants identified several institutions, including Strategies 1–4, Norm 1 and Rule 1, that were associated with the Games’ impact on the PC of the BLBC and local community. For instance, there was a plan to create a legacy through the development of social and cultural facilities. Interview data from GOLDOC, GCCC and BLBC-E point to the intentions of the plan and provide indications of its success. For example, a GOLDOC representative stated: “The focus was on creating a club-type environment that suited legacy” (GOLDOC1); and a GCCC representative stated that the role of GCCC in the BLBC refurbishment was to ensure: “The council were getting buildings that could be maintained, [and] that operationally suited their needs” (GCCC1).

BLBC patrons indicated that the plan for legacy creation was successful. One patron said the availability to the public of upgraded facilities was “Fantastic” (BLBC-P1); another said: “It’s just nicer in there, if you compare it to another bowls club on the coast … People would prefer to go to this one” (BLBC-P2). A council representative suggested that, given the success of the Games, public support was high for hosting further mega-events (GCCC1).

The refurbished venue was viewed as positive for BLBC patrons and for the surrounding community. Interviewees explained that the effects of the BLBC refurbishment were evident soon after the mega-event, and the venue was now more than a lawn bowls club (BLBC-P2, BLBC-P3).

Two years after the Games, benefits were apparent from the changes to PC, both in the club and in the surrounding area. One BLBC patron noted: “Lots of beautification went on, they [GCCC] have put in a lot of effort” (BLBC-P3).

Linking social capital

The participants identified several institutions, including Strategies 11–15 and Rule 2, that were associated with two types of linking SC impacts. The first was the desire to create social and cultural legacies for the community, and the second was the desire to create more jobs and have a more powerful economy. GCCC worked with other performers, for example QSG and GOLDOC, to ensure that the infrastructure handed over to the council was affordable with respect to future maintenance. GOLDOC interacted with GCCC during the early design stages of the refurbishment to ensure this: “Their [council’s] requirements had to be incorporated into the design” (GOLDOC1). GCCC2 explained that a unit was established within the council to engage with other institutions on infrastructure works to ensure successful delivery, alignment with statutory planning and building requirements, and that public funding was used appropriately.

The collaborative nature of the refurbishment promoted a positive legacy and enabled the council to ‘inherit’ buildings that were fit for purpose following the Games (GCCC2). Post event, interviewees suggested that the club had a better social atmosphere, and the venue was a more desirable destination (GOLDOC1, BLBC-P5).

Along with linking SC, bridging SC also became important in terms of collaborative efforts to refurbish the venue and create a mega-event that strengthened the local economy. One interviewee stated: “[The Games and refurbishment] definitely had a positive impact on the area … they get obviously more clients, you know, the more clients you get, the more revenue you get, and more tournaments you can get” (BLBC-P5).

Bridging social capital

The participants identified four strategies (7, 8, 9 and 10) associated with impacts on bridging SC that articulated an aspiration for the BLBC to better serve the surrounding community, and for the Games to be used as an opportunity to attract international visitors and improve the region’s social fabric.

The respondent who was a mega-event games consultant stated that: “There’s a much better facility, and it’s more than just a bowls club. It’s a community facility” (MEGC1).

BLBC patrons said refurbishment had improved social fabric (BLBC-P3, BLBC-P4). BLBC-E1 said the club’s ties to the community had strengthened since the refurbishment; BLBC-P1 said international visitors to the region had also increased.

This increased activity in the local and international marketplace boosted job creation and economic development. Both the interviews and documents analysed indicated a collaborative effort by organisations resulting in a strengthened local economy, ultimately increasing bridging SC. A BLBC executive spoke of a unified small business community following the Games: “I’ve never seen so many small businesses brought together since the Games to produce a new market” (BLBC-E1). BLBC-E1 elaborated that the refurbishment, combined with the club’s unique location, had resulted in business growth for the venue.

The overall positive impact of the Games was articulated by BLBC-P1: “[The Games] brought a lot of international visitors here and we’re seeing visitors coming from more destinations now than we used to before” (BLBC-P1).

BLBC-P5 commented: “[The refurbishment has] been a benefit in terms of the facilities – you can encourage more tournaments, obviously high-class tournaments with those facilities and in terms of the social aspects as well” (BLBC-P5).

Bonding social capital

Bonding SC impacts identified in this study included a strengthening of ties among BLBC membership, which participants associated with Strategies 6 and 7. BLBC-P5 said the refurbishment “definitely had a positive impact on the area”. The Games also seem to have stimulated BLBC members to re-engage with the refurbished club (BLBC-P5). BLBC-P1 said the club was busier than prior to refurbishment.

Discussion

This study aligns with Chalip’s (2006) assertion that when a community is part of something bigger than itself, social connections can be built and the social fabric of host communities can be strengthened (Thomson et al. 2010). The larger context of the Games provided mega-event governance bodies with the opportunity to improve the PC of the BLBC, and this promoted the development of bridging and bonding SC. These findings support studies that argue improving infrastructure can deliver real social benefits, and that sporting mega-events can enhance the social life of host cities (Horne 2015: McIntosh et al. 2018). The discussion below addresses each type of capital mentioned above in turn, commencing with PC, then linking SC, and, finally, bridging and bonding SC. Discussion of each type of capital is contextualised within the mega-event literature and the broader literature on capitals. The section concludes with a summary of the study’s strengths and limitations, and by offering recommendations for future mega-event research, policy and practice.

The IGT and CCF methodological tools provided a means to identify institutions operating within the Games’ administration and governance processes. These were supported by linking SC and led to the transformation of the BLBC (see Table 5). For example, the aspiration of GOLDOC was to upgrade facilities to enhance the local community (Strategy 1). This, combined with GCCC establishing departments to look after the infrastructure required for the Games (Strategy 14), generated ties that linked these organisations together with others representing local communities (BLBC Executives and Patrons) and enabled renovation of the BLBC. Linking SC thus facilitated the improvement of local PC – the renovated BLBC – that was needed to generate bridging SC (Strategy 8), and bonding SC (Strategies 5 and 6) within the community. These findings on linking SC align with those of Kromidha et al. (2017) for the London 2012 Olympics. Kromidha et al.’s (2017) report highlighted how the aspirations for local benefits from the London Games by high-level actors such as the International Olympic Committee, and mid-level actors such as the London 2012 Sustainability Group, helped generate ties (ie linking SC) with local communities and deliver impact at the local level. As Evans (2005) had also previously argued, actions by government bodies which are aligned with communities are a powerful tool in the development of mega-events.

Studies have long highlighted the important role that mega-events play in developing and enhancing local community infrastructure. For example, Prior and Blessi (2012) show how Sydney’s hosting of the 2000 Olympic Games saw additional community infrastructure built. Drummond and Cronje (2019) describe how the infrastructure for the 2010 FIFA World Cup in South Africa led to infrastructure legacies in the local and regional community. The present study found that the development of PC for the BLBC, enabled through Strategies 3 and 14 and Norm 1, contributed to the amplification of bonding SC (Strategies 5 and 6) and bridging SC (Strategies 9 and 10) within the local community. Such development was facilitated by the support of the BLBC members and executives. These findings complement Prior and Blessi’s (2012) study which emphasised the important role the new (and accessible) facilities at Sydney Olympic Park played in developing bridging and bonding SC within local communities.

In addition, the present study aligns with the findings of Van Wynsberghe et al. (2011) that facilities developed for the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver, Canada enhanced local community capacity. Unlike some broader research (see Prior and Blessi 2012), this case study found no negative impacts on bridging and bonding SC within local communities. Furthermore, its findings support those of Fedders (2018), who argues that SC is often grown through a city’s PC such as parks, churches and museums that build networks and connect people. Finally, and more broadly, the findings align with work on the development of infrastructure and SC by McIntosh et al. (2018) and Baum (2002). They identify sporting grounds, service clubs and pubs as important sites for facilitating social interactions.

In line with Misener and Mason (2006), who suggest that sporting mega-events can create SC in the host city and communities, this study found the linking SC generated by the Games, in combination with improved PC associated with the refurbishment of the BLBC, provided the foundation for enhanced bridging and bonding SC within the local community. These changes would not have occurred without Games investment. The lived experiences of BLBC executives and patrons confirmed improved SC as an outcome of the venue refurbishment and the Games. Their experiences suggest that local social fabric was enhanced. Massey (2005, p. 111) describes the concept of social fabric in his research:

Social capital is not a property that can be amassed, stored or owned, it inheres in social relations and is thus an effect of practice or how people engage in their social relations. The resulting fabric of social relations is thus an ‘arrangement in relation to each other that is the result of there being a multiplicity of trajectories’.

In the current study, the combination of bridging and bonding SC enhanced social fabric within the community. This was expressed as a sense of pride in the venue, region and Games. Feeling a part of, and being able to deliver on, such aspirations gave the local community a sense of gratification. As was explained by the BLBC executive, many local businesses banded together to pursue new opportunities because of the refurbishment and Games. Such findings support Ceschin (2014) who argues that local economies flourish when people within the local community invent new ways of using existing assets. In addition, this finding is also consistent with literature going back decades which has previously stated that improved urban sporting infrastructure creates benefits which ultimately flow to the local economy (property developers, stadium operators, etc) in the form of employment growth (Smith and Judd 1982; Jones 2001).

By combining the IGT with the CCF this study has piloted a unique research methodology that can be used to explore how institutions – strategies, norms and rules – associated with mega-events guide physical and social capital impacts. Future studies could use this methodology to gain a wider understanding of the relationship between institutions and capital impacts of other mega-event contexts, and the methodology also has the potential to be applied to other governance activities beyond mega-events. It might be enhanced by using a consensus process (eg Delphi1 process) with study participants involved in defining the institutions to develop an understanding of the relative importance and values of the roles played by the various ‘performers’, and the varying appropriateness and effectiveness of the different institutions (strategies, norms and rules) that they put in place. Furthermore, whilst this study only retrospectively explored how the institutions associated with the Games impacted community capital, it is possible that later studies could adapt the methodology in order to inform understanding of how institutions might be developed or altered to create more positive and sustainable changes in affected communities: for example, once institutions were identified, their impact could be the subject of ongoing evaluation and adjustment.

The study was, however, subject to several limitations. Firstly, the sample size for the qualitative analysis was small (11 people), which as DePaulo (2000) has noted may risk missing important details. Further studies might collect a more representative sample of community performers so as to develop a wider understanding of the broader social impacts on the Broadbeach community, as opposed to the bowling club itself. Secondly, the case study covered a single venue, which limits the scope to apply its findings elsewhere; and the type of community venue selected for this study may have affected the impacts on the surrounding community. Thirdly, the study was limited by its overall timeframe, in that it only captured PC and SC legacies arising during the Games and for four years afterwards. Further research is needed to identify longer-term PC and SC impacts. The fourth limitation is the considerable amount of documentation that was gathered to produce its findings, 17 documents and 11 interviews. An analysis on multiple, and/or larger cases could be carried out with a rigorous approach using selective documentary and interview data collection and analysis.

Despite these limitations, however, some key recommendations can be made for research, policy and practice:

• The IGT and CCF are valuable tools that can be used and refined in further studies. Such studies are needed to better understand how processes within mega-events impact local communities, and the types of impacts they have.

• Comprehensive frameworks are needed to identify and examine the tangible and intangible impacts arising from staging a mega-event.

• There is an opportunity to explore more deeply the dynamics of relationships between the key governing bodies of the Gold Coast 2018 Commonwealth Games in order to understand why the GOLDOC model was successful. This may assist in guiding the development of mega-events in other locations.

• The findings present opportunities for local councils and other organisations to build on this research to maximise the benefits of mega-events.

Conclusion

This study has provided empirical and methodological insights into how mega-events, and their governance, impact host communities, as well as methodologies that can be used to study them. This study indicates that the Gold Coast 2018 Commonwealth Games, through the refurbishment of the BLBC, enhanced PC and SC within the local community of Broadbeach. It also suggests the combined use of the IGT and CCF offers a useful framework to assess the impact of a mega-event on local communities.

The study suggests that the incorporation of stakeholders’ needs during early design and planning stages of a mega-event, coupled with close collaboration among governing organisations, can enhance selected dimensions of community capital with legacy outcomes for local communities through place-making in the host city. Local communities can benefit from improved physical infrastructure and enhanced social fabric. From a methodological perspective, the use of the IGT provided a systematic way to assess the institutions established to guide mega-event governance, while the CCF offered a method to understand how community capitals may be influenced within a mega-event setting.

The research demonstrated conceptual frameworks and methodological tools that could be applied to other mega-event case studies. In turn, those further studies would enable a wider understanding of how the significant investments put into mega-events are guided and implemented in a way that helps promote positive social, physical, environmental and economic benefits to the host countries, cities and communities. This was underlined by recent comments from Paralympics Australia officials on the proposed 2032 Summer Games in Brisbane, Australia, stating that: “The real key for us as custodians of the Paralympic movement in Australia is about the social impact that the 2032 Paralympic Games will bring” and that: “Long-term benefits will be realised across Australia, including in employment, skills, education, health and wellbeing outcomes, higher sporting participation rates, and in culture and community connection” (Brisbane Times 2021).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge all participants who took part in this study.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

Australian Leisure Management. (2020) Broadbeach bowls club upgrade inspires new generation of bowlers. Australia. Available at: https://www.ausleisure.com.au/news/broadbeach-bowls-club-upgrade-inspires-new-generation-of-bowlers/ [Accessed 22 June 2020].

Basurto, X., Siddiki, S., Weible, C. and Calanni, J. (2011) Dissecting policy designs: an application of the institutional grammar tool. Policy Studies Journal, 39 (1), 73–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2010.00397.x

Baum, P. (2002) ‘Opportunity structures’: urban landscape, social capital and health promotion in Australia. Health Promotion International, 17 (4), 351–361. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/17.4.351

Bovy, P. (2013) Mega event transport 2013. Available at: https://www.slideshare.net/PhilippeBOVY/mega-event-transport-2013 [Accessed 9 September 2017].

Brisbane Times. (Australia) (2021) Tokyo Olympics as it happened: Brisbane confirmed as 2032 hosts as Matildas play against New Zealand. Available at: https://www.brisbanetimes.com.au/sport/soccer/tokyo-olympics-live-updates-brisbane-2032-to-be-confirmed-as-matildas-prepare-for-new-zealand-20210719-p58axh.html?post=p52iqk [Accessed 20 August 2021].

Broadbeach Bowls Club Australia. (2020) Broadbeach Bowling Club. Available at: https://www.broadbeachbowlsclub.com.au/club-history [Accessed June 6, 2020].

Carter, D.P., Weible, C.M., Siddiki, S.N., Brett, J. and Chonaiew, S.M. (2015) Assessing policy divergence: how to investigate the differences between a law and a corresponding regulation. Public Admin, 93, 159–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12120

Ceschin, F. (2014) Innovation for sustainability: design research guest lecture. [Lecture]. London: Brunel University London.

Chalip, L. (2006) Towards social leverage of sport events. Journal of Sport and Tourism, 11 (2), 109–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/14775080601155126

Chalkley, B. and Essex, S. (1999) Urban development through hosting international events: a history of the Olympic Games. Planning Perspectives, 14 (4), 369–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/026654399364184

Commonwealth Games Federation. (CGF). (2020a) Gold coast city: candidate city file. Gold Coast Volume 1 Available at: https://thecgf.com/sites/default/files/2018-03/Gold_Coast_VOL_1.pdf [Accessed 1 May 2020].

Commonwealth Games Federation. (CGF). (2020b) The role of the CGF. (UK). Available at: https://www.thecgf.com/about/role.asp [Accessed 9 September 2020].

Cooper, R. (2016) Decoding coding via the coding manual for qualitative researchers by Johnny Saldaña. Qualitative Report. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2009.2856

Crawford, S. and Ostrom, E. (1995) A grammar of institutions. American Political Science Review, 89 (3), 582–600. https://doi.org/10.2307/2082975

Crawford, S. and Ostrom, E. (2005) A grammar of institutions. In Ostrom, E. (ed.) Understanding institutional diversity, (pp. 137–74). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

DePaulo, P. (2000) Sample size for qualitative research: the risk of missing something important. Quirk’s Marketing Research Review. Available at: http://www.quirks.com/articles/a2000/20001202.aspx

Drummond, R. and Cronje, J. (2019) Building a white elephant? The case of the Cape Town Stadium. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 11 (1), 57–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2018.1508053

Dunlop, C.A., Kamkhaji, C.J. and Radaelli, C.M. (2019) A sleeping giant awakes? The rise of the Institutional Grammar Tool (IGT) in policy research. Journal of Chinese Governance, 4 (2), 163–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/23812346.2019.1575502

Emery, M. and Flora, C. (2006) Spiraling-up: mapping community transformation with community capitals framework. Community Development, 37 (1), 19–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/15575330609490152

Evans, G. (2005) Measure for measure: evaluating the evidence of culture’s contribution to regeneration. Urban Studies, 42 (5/6), 959–983. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980500107102

Fedders, E. (2018) Quantifying the importance of social infrastructure in community resilience using social capital. MS Thesis, University of Kansas, Kansas, USA.

Frantz, C. and Siddiki, S. (2020) Institutional grammar 2.0 Codebook. Available at: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2008.08937.pdf

Flora, C.B. and Flora, J.L. (2008) Rural communities: legacy and change. 3rd ed. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Flora, C.B., Flora, J.L. and Gasteyer, S.P. (2016) Rural communities. Legacy + change. 4th ed. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429494697

Gold Coast City Council. (GCCC). (2021) Gold Coast City community profile. Available at: https://profile.id.com.au/gold-coast/population [Accessed 24 April 2022].

Gold Coast Commonwealth Games Corporation. (GC). (2018a) Sustainable sourcing code. Available at: https://gc2018.com/sites/default/files/2017-11/GC2018_Sustainable_Sourcing_Code.pdf [Accessed 2 May 2018].

Gold Coast Commonwealth Games Corporation. (GC). (2018b) About. Share the dream. Available at: https://gc2018.com/about [Accessed 11 January 2019].

Gold Coast Commonwealth Games Corporation. (GC). (2018c) Publications. Available at: https://gc2018.com/about/publications [Accessed 2 May 2018].

Hiller, H.H. (1999) Toward an urban sociology of mega-events. Constructions of urban space. Vol. 5, (pp. 181–205). https://doi.org/10.1016/S1047-0042(00)80026-4

Hoff, K., Leopkey, B. and Byun, J. (2020) Organizing committees for the Olympic Games and satellite host local organizing committees: examining their relationships and impact on legacy creation. Managing Sport and Leisure. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2020.1856710

Horne, J. (2015) Assessing the sociology of sport: on sports mega-events and capitalist modernity. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 50 (4–5), 466–471. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690214538861

Jacobs, B. and Brown, P.R. (2014) Drivers of change in landholder capacity to manage natural resources. Journal of Natural Resources Policy Research, 6 (1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/19390459.2013.869032

Jones, C. (2001) A level playing field? Sports stadium infrastructure and urban development in the United Kingdom. Environment and Planning, 33 (5), 845–861. https://doi.org/10.1068/a33158

Kromidha, E., Spence, L.J., Anastasiadis, S. and Dore, D. (2017) A longitudinal perspective on sustainability and innovation governmentality: the case of the Olympic Games as a mega-event. Journal of Management Inquiry, 28 (1), 77–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492617711585

Kruger, E.A. and Heath, E.T. (2013) Along came a mega-event: prospects of competitiveness for a 2010 FIFA World Cup host city. Current Issues in Tourism, 16 (6), 570–590. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2012.714748

Lien, A.M. (2020) The Institutional Grammar Tool in policy analysis and applications to resilience and robustness research. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 44, 1–5. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340632156_The_institutional_grammar_tool_in_policy_analysis_and_applications_to_resilience_and_robustness_research

Manley, R.A. (2013) The policy Delphi: a method for identifying intended and unintended consequences of educational policy. Policy Futures in Education, 11 (6), 755–768. https://doi:10.2304/pfie.2013.11.6.755

Massey, D. (2005) For space. London: Sage.

McGinnis, M.D. (2011) An introduction to IAD and the language of the Ostrom Workshop: a simple guide to a complex framework. Policy Studies Journal, 39, 169–183. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2010.00401.x

McIntosh, C., Alegría, Y., Ordóñez, G. and Zenteno, R. (2018) The neighborhood impacts of local infrastructure investment: evidence from urban Mexico. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 10 (3), 263–286. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20160429

Misener, L. and Mason, D.S. (2006) Creating community networks: can sporting events offer meaningful sources of social capital? Managing Leisure, 11 (1), 39–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/13606710500445676

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. (OECD). (1991) Urban infrastructure: finance and management. Paris: OECD.

Ostrom, E. (2005). Understanding institutional diversity. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Perry, D.C. (1995) Building the public city: an introduction. In: Perry, D.C. (ed.) Building the public city: the politics, governance and finance of public infrastructure, (pp. 1–20). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Preuss, H. (2015) A framework for identifying the legacies of a mega sport event. Leisure Studies, 34 (6), 643–664. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2014.994552

Prior, J.H. (2016) The norms, rules and motivational values driving sustainable remediation of contaminated environments: a study of implementation. Science of the Total Environment, 544, 824–836. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.11.045

Prior, J.H. and Blessi, G.T. (2012) Social capital, local communities and culture-led urban regeneration processes: the Sydney Olympic Park experience. Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 4 (3), 78–96. https://doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v4i3.2684

Putnam, R.D. (2000) Bowling alone: the collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon & Schuster. https://doi.org/10.1145/358916.361990

Putnam, R.D. (2001) Social capital: measurement and consequences. In Helliwell, J.F. (ed.) The contribution of human and social capital to sustained economic growth and well-being, (pp. 117–135). Ottawa, Canada: Human Resources Development Canada:

Santos, J.F., Vareiro, L., Remoaldo, P. and Ribeiro, J.C. (2017) Cultural mega-events and the enhancement of a city’s image: differences between engaged participants and attendees. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 9 (2), 129–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2016.1157598

Smith, M.P. and Judd, D.R. (1982) Structuralism, elite theory and urban policy. Comparative Urban Research, 9 (2), 127–144.

Thomson, A., Leopkey, B., Schlenker, K. and Schulenkorf, N. (2010) Sport event legacies: implications for meaningful outcomes. In Proceedings of the 2010 Leeds Event Legacy Conference, Leeds, UK.

Tziralis, G., Tolis, A., Tatsiopoulos, I. and Aravossis, K. (2008) Sustainability and the Olympics: the case of Athens 2004. International Journal of Sustainable Development and Planning, 3 (2), 132–146. https://doi.org/10.2495/SDP-V3-N2-132-146

Van Wynsberghe, R., Kwan, B. and Van Luijk, N. (2011) Community capacity and the 2010 Winter Olympic Games. Sport in Society, 14 (3), 370–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2011.557274

Washington State University (USA). (2011) Community capitals framework. https://s3.wp.wsu.edu/uploads/sites/2063/2015/07/REM.CommCaps.pdf [Accessed 14 July 2018].

What Culture (USA). (2017) Top 10 most-watched sporting events in TV history. Available at: http://whatculture.com/sport/10-most-watched-sporting-events-in-tv-history?page=2 [Accessed 17 April 2017].

Woolcock, M. (2001) The place of social capital in understanding social and economic outcomes. Canadian Journal of Policy Research, 2, 1–17.

1 A Delphi Process is a methodology used to arrive at a group consensus by surveying a panel of participants who have knowledge of a specific process. These participants respond to several rounds of questionnaires, and their responses are aggregated and shared with the group after each round. Delphi processes have been used in the policy context as a tool to help decision-makers (eg policy-makers, researchers) to make a well-assessed decision on who is currently implementing a policy, the usefulness of that policy, and identify its intended and unintended consequences (Manley 2013).