Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, Issue 23, 2020

ISSN 1836-0394 | Published by UTS ePRESS | https://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/journals/index.php/cjlg

RESEARCH AND EVALUATION (PEER REVIEWED)

When public spending goes local: agricultural expenditure at a key stage in Ghana’s decentralisation reform

Tewodaj Mogues

International Monetary Fund

(formerly, International Food Policy Research Institute)

1201 I St. NW

20005 Washington District of Columbia

United States

Email: tmogues@imf.org

Modernising Agriculture in Ghana Project

Ghana

Email: kwakuowusubaah@gmail.com

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi23.7560

Article History: Received 12/12/16; Accepted 7/10/20; Published 30/12/20

Citation: Tewodaj Mogues and Kwaku Owusu-Baah. 2020. When public spending goes local: agricultural expenditure at a key stage in Ghana’s decentralisation reform. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance 2020, 23: 7560, https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi23.7560

© 2020 by the author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Abstract

This paper provides a qualitative analysis that highlights the implications on agricultural services of a key stage in decentralisation reforms in Ghana. We assess the status of agricultural expenditure decentralisation and draw out the likely implications for agricultural service delivery and national strategies. The study finds that agricultural officers at all levels (national, regional and district) had concerns about the implementation of the new decentralisation reform. These included budget cuts and delays in releases that coincided with the reform period; the transfer of staff from the civil service to the local government service; and a sense that agriculture may receive less attention when allocation of government resources becomes the preserve of assemblies and district chief executives, rather than the central agricultural ministry. The structural changes also meant that agricultural local government staff now needed to learn to ‘market’ the value of their public services to local government leadership, in order to protect resources for agriculture. The decentralisation reform also necessitated new public expenditure reporting practices to ensure a clear overview of sectoral spending across government tiers.

Keywords:

Local government, public spending, fiscal reform, agriculture, Ghana

Introduction

Objectives

This paper provides an empirical analysis of a recent stage in Ghana’s decentralisation of agricultural service delivery. This stage began in 2011 and, as described below, devolved to the district level certain public funds for agriculture and other sectors which previously had been channelled through central ministries, such as the Ministry of Food and Agriculture.

The paper offers insights into the status of agricultural expenditure decentralisation in Ghana and draws out the likely implications for agricultural service delivery and national strategies. It describes the state of decentralisation of agricultural services and funds in 2013, and compares these conditions to those that prevailed before the reforms were initiated in 2011. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this paper is the only academic study that analyses the implications of this particular decentralisation reform for agricultural policy-making. In light of the scarcity of research on this topic, the authors also identify a range of issues for further research attention, and potential opportunities for carrying out such research.

Methods

The study offers a qualitative analysis based on field interviews undertaken in two different local authorities: Ga West Municipal Assembly (referred to as ‘GW’) and Shai-Osodoku District Assembly (referred to as ‘SO’). These represent two different types of local assembly, but are similar in their higher-tier (ie regional) context and environment, as both are located within the Greater Accra region.

The analysis is primarily based on key informant interviews conducted in 2013 by the authors and were structured to allow comparative analysis. The key informants included senior officers from both Ghanaian and international organisations based in Ghana with expertise in the fields of agriculture, public finance, decentralisation and local government affairs. Specifically, the interviews included senior officers of relevant stakeholder institutions, including the Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development (MLGRD); the Ministry of Food and Agriculture (MoFA) at national, regional and district levels; the Local Government Service (LGS) Secretariat; the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA), since amalgamated into Global Affairs Canada (Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development (DFATD)); the fiscal decentralisation unit of the Ministry of Finance (MoF); and the International Development Institute for Leadership, Management and Technology (IDILMAT). In addition to interviews, various government legislative instruments were examined, including legal Acts, and draft Bills.

Ghana’s decentralisation, past and present

Literature review providing a historical perspective

Decentralisation in Ghana has been part of both public debate and political, fiscal, and administrative processes over a long time period (Crook 2003; Mohan 1996), stretching back to the period immediately after independence in 1957 (Ayee 1996). It was not until 1989, however, that the then military government initiated action towards decentralising political governance (Crook 1994). The Provisional National Defence Council (PNDC) government which took power in December 1981 touted a political philosophy of devolving governance to the grassroots and placing power in the hands of ordinary people, and passed a law (Republic of Ghana Local Government Law 207) to start the process of transferring political and economic power to the districts: Ghana’s principal local administrative units, a legacy of colonial rule, at the time. The formally declared motivations for decentralisation reforms were, among others to place political and economic decisions in the hands of the citizenry at district level; to enhance community development in rural areas; and to reduce bureaucracy – including, by so doing, to eliminate or reduce corruption and promote transparency. The law was given a further boost by the 1992 Constitution, which in Chapter 20 states that parliament is to enact laws for the implementation of decentralisation. In 1993 parliament duly passed Local Government Act 462 (King et al. 2013) which, among other provisions, empowered the MLGRD to prescribe the date for the coming into force of new sections of the Act. These made provision for ‘composite budgeting’ (see below for discussion) at the district level, and created the Local Government Service (LGS), whose members would staff the decentralised departments of government.

However, it was not until a decade later in 2003 that the LGS was in fact established, through the Local Government Service Act (Act 656) (Koranteng and Larbi 2008), and 2004 before it began functioning. Act 656 also provided for the transfer of staff of district assemblies from the Civil Service (CS) to the LGS, and in 2009, Local Government Legislative Instrument (LI) 1961 was passed to convert the departments of central government ministries, departments and agencies located in the districts into departments of their local district assemblies (Asante and Debrah 2019). Further, it was only in 2011 that government finally implemented all aspects of Act 462, notably the ceding of affected staff from the CS to the LGS. As is apparent, the operationalisation of Act 462 and its related sections, since passage in 1993, has been rather slow.

Driving forces behind Ghana’s decentralisation

Decentralisation in Ghana has been a slow, incremental, and periodically stagnating process, with this gradual progress backed by the international community. The most active donor agencies in this regard have been the Danish International Development Agency (DIDA) and CIDA, alongside the World Bank and the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). These and other donors have channelled a significant part of their support to the country through the promotion of decentralised governance structures.

In 2010 Ghana’s Inter-Ministerial Coordination Committee for Decentralisation (IMCCD), chaired by the president, was established to provide greater political impetus to decentralisation in Ghana. In 2011 it was this committee, not MLGRD, which ordered staff identified in Act 656 to be ceded to the LGS from the CS. The IMCCD thus appeared to have a stronger role in this regard than MLGRD, even though it is the latter which is designated in the Constitution as the main body to steer decentralisation, a role that was confirmed in subsequent legislative instruments.

At the same time in 2011, Section 161(1) of the Local Government Act of 1993 became operational, meaning that some of the former central government departments in the districts ceased to exist. Instead, they were reconstituted and merged into 40 new departments: 16 at the metropolitan assembly level, 13 at the municipal assembly level, and 11 at the district assembly level. The offices of MoFA at district level were among those transferred to the local assemblies in this fashion. They were reconstituted into district-level departments of agriculture (DoAs) and made part of the local government structure.

This move by the IMCCD had four main objectives. First, affected staff were formally transferred from the CS to the LGS. Second, once staff were transferred, responsibility for their functions was transferred to the district. Third, all departments, as institutions, were made part of the local government structure. And fourth, Metropolitan, Municipal and District Assemblies (MMDAs) were to prepare ‘composite budgets’. This process involved all local departments preparing their own budgets, to be incorporated into an overall budget of each MMDA for submission directly to the MoF. Once these budgets were approved, MoF was to release the approved amounts directly to the MMDAs, bypassing the parent central ministries (namely MoFA in the case of agriculture).

In Ghana, the budget of each government ministry, department, or agency (collectively, ‘MDAs’) is sub-categorised by item. This is true both for central-level MDAs and for local-level MDAs. For example, the national budget for MoFA is categorised by item, and so are the budgets for each DoA. As shown in Table 1, before 2011 budgets were prepared under four main expenditure items: emoluments, administration, services and investment. However, since 2011, these budget expenditure items have been reclassified by the MoF into three by merging the former Items 2 and 3 into one item (the new Item 2, called ‘goods and services’), and by renaming the former Item 4 (now becoming Item 3) from ‘investment’ to ‘non-financial assets’. Subsequent references to the budget items in this report use the new classification system of three items, rather than the old four-item system.

By law, approved budgets and released funds for MMDAs under the decentralised system must include all three budget items. However, the study found this has not happened in practice. In 2012, only the funds for Item 2 (goods and services) were released directly to DoAs at district level. In 2013, at the time of the fieldwork for this report (mid-July), the MoF had yet to release any funds to the DoAs – despite the fact that Ghana’s fiscal year starts on 1 January. The central ministry continued to receive the funds for Item 3, and Item 1 funds continued to be transferred directly to personnel.

Ghana’s budget is invariably under-resourced, especially at the district level. Most resources go into emoluments (Item 1) through a ‘push’ mechanism; ie no request on the part of the recipient MDAs is needed for the release of these funds. Payments for staff salaries, including local government staff, are made by the controller and accountant-general’s department. For Item 3, however, a ‘pull’ mechanism is in place – MDAs are required to make requests for the release of these funds. However, frequently releases do not match requests – and in the case of MoFA, actual financial allocations to MoFA have usually been well below the ministry’s requests.

Serious shortfalls in the amounts of money released relative to the approved budgets, and significant delays in the releases, have been a severe problem not only for DoAs, but also for the regional agricultural development units (known as ‘RADUs’) and MoFA-national. It would be very useful for a future research project to investigate at exactly what stage in the budget process these delays and shortfalls occur.

Implementation of Legislative Instrument (LI) 1961

Before the transfer of staff from the CS to the LGS, there were 10,000 core staff physically employed at the MMDAs across the country. Most were in the deconcentrated1 departments that reported to the parent line ministries of central government, but some staff reported to the local assemblies. In March 2011, over 33,000 additional staff affected by LI 1961 were transferred from the CS to the LGS. This brought the number of staff employed within the local government structure to some 43,000 nationwide. The Danish International Development Agency provided funding support in 2012 for the LGS to carry out a human audit of the then 170 MMDAs to determine staffing gaps. The audit revealed a gap of 20,000 staff, and the LGS set out to recruit and fill the vacant positions at the MMDAs. In 2012, MoF gave clearance for the LGS to recruit 2,600 staff, who were subsequently posted to the MMDAs. However, in 2013, the number of MMDAs increased to 216 through the creation of an additional 46 districts, which are also staffed by members of the LGS.

Despite the legislative transfer of staff from the CS to the LGS in March 2011, some aspects of the arrangements did not change: for example, staff at the DoAs and other departments were still effectively handled administratively by the CS and not the LGS. Also, at the time of this study in 2013, after ten years of existence of the LGS, files and other documents on these local staff were still with the CS, since budget constraints prevented these files from being photocopied and a copy passed to the LGS. Therefore, the LGS did not have sufficient data on its staff for effective personnel administration. Our field research found that the District Assembly Common Fund (DACF) office had agreed to provide funding for the exercise of the transfer of these personnel files.

This discrepancy between the formal and the de facto arrangements for administrative decentralisation of civil servants was echoed in operational responsibilities and lines of reporting. Additionally, the functions of some departments in the MMDAs continued to be performed by the corresponding line ministries at the regional and national levels, because of lack of expertise at the MMDA level. Furthermore, in light of the sometimes cross-district aspects of certain subnational activities, works that could in principle be carried out jointly by district and regional authorities were at times managed only by the latter. An example is the Ministry of Roads and Highways, where feeder road construction and maintenance was retained as a responsibility of the regions.

Empirical findings on Ghana’s agriculture in the decentralisation process

This section of the paper focuses on findings from the fieldwork that shed light on how the relationship between MoFA and the district DoAs has evolved following the recent changes in decentralisation. The authors also examine the analogous region–district relationship, and assess the ways that the decentralisation reforms have affected district-level planning, fiscal and administrative processes. Findings from the field interviews corroborate some of the general descriptions of the previous section, as well as providing additional and deeper insights into the implications of the recent changes for the institutional organisation of agriculture in Ghana.

Relationship between the Ministry of Food and Agriculture of the central government and the district-level Departments of Agriculture

Up until 2012 the central ministry based in Accra, MoFA (hereafter referred to as ‘MoFA-national’), was responsible for budgetary preparation and funds releases to its regional, metropolitan, municipal and district offices – ie to the RADUs and the metropolitan, municipal, and district agricultural development units (known as ‘DADUs’). Administratively, the DADUs were housed within MoFA’s extension directorate. Field interviews revealed that until 2012, the process for budget preparation started with the organisation of an annual national strategic planning session to agree agricultural priorities and strategies for the year. The planning sessions were attended by regional, metropolitan, municipal, and district staff, as well as other stakeholders, such as farmer organisations, non-traditional exporters, relevant ministries, NGOs and donors. Agreements at these planning sessions provided guidelines for budget preparation at the metropolitan, municipal, district, regional and national levels. The national budget included that of the technical directorates of MoFA-national, the office of the minister, the office of the chief director, and other cost centres that receive funds directly from the national budget, such as agricultural training institutes. Strategic direction for Ghana’s agriculture, therefore, was led by MoFA-national.

At the end of the planning session, RADUs and DADUs were given a timeframe within which to prepare and submit their plans and related budgets to MoFA-national. MoFA-national then aggregated the plans and budgets from the ten regions and all MMDAs into a single MoFA strategic plan and budget for submission to the MoF for incorporation into the national budget. Budgets, at all levels, were prepared based on ceilings provided by the MoF to MoFA, which were circulated to all MoFA regional directors and to the MMDAs.2 The national budget was then presented to parliament for its approval. Once approved, MoF released funds quarterly to MoFA-national. These funds then were released by MoFA-national on a quarterly basis to the RADUs, including funds for onward release to metropolitan, municipal, and district offices. This arrangement meant that MoFA-national was in a position to influence the funding available to its technical, regional, metropolitan, municipal, district, and other cost centres in terms of adequacy, timeliness and use. The magnitude of this influence of course was subject to the quantity and timing of funds that MoFA-national received from MoF.

With the coming into force of LI 1961 in 2012, MoFA budgeting processes morphed into a blend of the old and a new system. What stayed the same is that MoFA’s 2012 budget document, prepared in 2011, was the product of aggregation across the government tiers and was submitted to MoF. Also, the funds for Item 3 continued to be transferred to MoFA, which allocated these to the agriculture agencies across all tiers. However, an important change was introduced in 2013: the implementation of ‘composite budgets’ at local level. Essentially, composite budgets provide a consolidated account of revenues and expenditures of MMDAs, including their decentralised departments, rather than departments’ resources and spending featuring only in the budgets of the corresponding central line ministries. With respect to agriculture, this meant that, for the 2013 financial year budget, DoAs prepared their own plans and budgets and integrated them into the plans and budgets of their respective MMDAs. An equally important change was that MMDAs then submitted the composite 2013 budgets directly to MoF, without recourse to line agencies at the centre, such as MoFA-national.

The 2013 national budget was approved in the last quarter of 2012.3 The release of funds, however, replicated the process in 2012: MoF was to directly release funds for Item 2 to the MMDAs, following which DoAs would receive from the MMDAs their portion of the Item 2 funds for operations in 2013. Item 3 funds were still to go through the central line ministries, as in 2012 and prior years, while Item 1 funds were transferred via direct deposit, again as in the past.

With the new composite budgeting system, two other key things did change. First, MoFA-national’s control over local-level agricultural priorities and strategies was somewhat reduced. To the extent that expenditures are a close reflection of budgets – arguably a questionable assumption, and one that can be analysed empirically – the composite budgeting system had implications for setting and achieving common national agricultural priorities and strategies. DoAs’ agricultural plans were generally still based on national agricultural policies.4 However, the composite budgeting system affected the balance between on the one hand adhering to national policies, and on the other meeting the core objective of decentralisation by tailoring investments to local needs. The 2013 changes mean the balance became more tilted towards local needs. Where the optimal balance lies, and how it can be assured through the assignment of fiscal control, monitoring and incentives across public agents in the different tiers, is an important issue deserving of future analysis.

Second, the changes meant that MoFA-national in principle now had less control over the allocation of funding for Item 2 expenditures within the local agricultural budget. However, MoFA-national continued to direct several major agricultural programmes that received funding through the Item 2 budget category. The ministry was not eager to decentralise these to the districts, in the sense of transferring substantive authority over resource allocation decisions for them.5 These MoFA-national controlled programmes include the fertiliser subsidy programme, the block farming programme, agricultural mechanisation centres, and the irrigation development programme. It is estimated that these national programmes together make up about 85% of the ministry’s capital budget – leaving less than 15% for RADUs and DoAs to utilise in carrying out their core activities.

Continuing importance of centrally controlled regional departments

RADU offices were not part of the decentralised structure. Accordingly, they continued to be tied to MoFA-national in terms of staff reporting lines, planning and budget preparation, and financial releases. In the case of Greater Accra region – where this study’s regional and district-level field interviews were undertaken – the 2013 Item 2 funds slated for the RADUs had already been released at the time of the interviews, and the amount was higher than in previous years.

In the past, RADUs were responsible for overseeing the activities of DADUs in their respective regions, including for the financial releases of quarterly budgets to them, providing technical backstopping, receiving their technical and financial reports, aggregating these reports into comprehensive reports on the activities of the RADUs and DADUs within the region’s jurisdiction, and ensuring financial discipline at the MMDA level. Based on field interviews conducted at regional level, here we describe the post-reform state of affairs.

Under LI 1961, the responsibilities of RADUs and, for that matter, regional administration offices have merely waned – as opposed to being drastically reduced. In 2013, at the time the interviews were undertaken, the effect of the new decentralisation regime for the scope of responsibilities for RADUs was not well known for two reasons. Firstly, the formal implications of LI 1961 implementation had yet to be crisply defined, and secondly no in-depth studies had yet been done on the de facto effect of LI 1961 on the RADUs.6 In the absence of clearly delineated new roles, RADUs continued to perform most of their traditional duties. For example, in 2012 and 2013, DoAs in the Greater Accra region still submitted a copy of their technical and financial reports to the regional directors, in addition to submitting them to the MMDA leadership. DoA accountants also continued to send monthly financial accounts to the RADUs, who retained their coordinating role on MoFA’s behalf. There was a change, however, in budget routing: in 2012, budgets of MMDAs no longer passed through the RADUs, as described above.

Overall, the study’s interviews found that, despite being integrated into the assembly structure, the DoAs continued to look towards the RADU and to MoFA-national for technical guidance and resources, as was to be expected in the short run and in a time of uncertain transition. For example, a request for staff replacement from GW Municipal Assembly DoA was made to the human resource development directorate of MoFA, instead of to the LGS through the assembly. Somewhat analogously, the same DoA submitted its 2012 technical and financial reports to MoFA-national, through the Greater Accra MoFA office, even though the DoA’s 2012 budget (at least for Item 2) was received directly from MoF through the assembly, as mentioned above.

District Departments of Agriculture: planning for, requesting, and receiving financial and human resources

In fiscal years 2012 and 2013, the budgets for the two DoAs of GW and SO, together with those of several other departments within the two assemblies, were incorporated into the composite budgets of each assembly. These budgets were submitted directly to the MoF. The process was as follows, using GW as an example. All departments submitted budget requests to the GW municipality budget office. These department budget requests were aggregated and submitted to the assembly’s executive committee for its deliberations.7 The budget, as agreed by the executive committee, was then presented to the full assembly for further discussion and approval. This approved GW composite budget was then sent to the MoF. It is noteworthy that more detail was available in GW’s 2013 composite budget than in that for 2012, as the 2013 budget includes details by sector (eg agriculture).

Aside from the funds received by the DoAs from the MoF via their assemblies (see below), the GW DoA also received limited funding from other sources. For example, MoFA projects still retained Project Implementation Units (PIUs) that released funds directly to participating districts. These funds were fully tied to specific projects managed by MoFA-central, and could not be used flexibly by the DoAs. The DoA in GW was participating in two MoFA projects: an export management and quality awareness project; and a statistics, research and information directorate project. In 2012, the DoA received GHC 9,660 from the export management and quality awareness project for training and another GHC 5,920 from the statistics, research and information directorate project to pay expenses of field officers engaged on the project. Another source mentioned by interviewees was international development institution funding to carry out specific assignments tied to particular projects. This suggests that international development institutions, as well as district-level government, MoFA-national, and the RADUs, could drive and influence DoA activities. Importantly, this interaction between NGOs and the DoAs usually did not involve MoFA-national and, thus, would not be visible in MoFA’s budget.8

The GW DoA also benefited from supplementary funds made available by the assembly. Typically, but not necessarily exclusively, these supplementary funds came out of the DACF. The DoA would make particular requests, such as for vehicle repair, to the assembly, and the assembly then arranged for the repair to be undertaken using DACF funds. Also, in preparing its annual plans and budgets, the assembly identified ‘special’ agricultural activities of particular interest to the assembly and budgeted for them in its own (assembly) budget. Sample activities in GW included funding for an anti-rabies campaign and for the district Farmers’ Day. For example, in 2012 the DoA received GHC 25,000 from the assembly budget for the organisation of the Farmers’ Day.

The situation in SO, however, was different. Here the DoA received no supplementary funds from the assembly. Even information about potential sources was scarce to nearly non-existent, nor was the district composite budget process clear to the DoA director or management staff. The DoA submitted its 2012 and 2013 budgets to the assembly for incorporation into the district composite budget, but was never invited to any meeting to discuss the budget requests. In the same vein, whenever there were budget cuts, re-prioritisation was done by the assembly with no input from the DoA. In consequence, the director and management staff of the DoA in SO asked for further training, for example at the Institute of Local Government Studies (ILGS), to better understand their roles and responsibilities within a decentralised structure. However, even to get as far as being trained, DoA staff in SO had to be proactive in taking an interest in how the district was technically and administratively administered – as a MoFA-national official respondent pointed out. This proactive approach was important to getting agriculture on the priority list of the assembly and to winning a larger slice of the budget for agricultural activities. The process through which the orientation and focus of DoA staff can be adjusted to take advantage of these new administration and resource allocation processes is an important question for those providing governance and capacity-building support to agriculture in the increasingly decentralised context.

One area where decentralisation was not yet effective was recruitment. For purposes of providing agricultural services, DoAs in GW zoned their coverage area into operational areas, with one agricultural extension agent (AEA) assigned to each operational area. Because there are fewer AEAs than operational areas in GW, some AEAs were assigned to more than one operational area. Due to the tight central government budget, there was a long-persisting staffing policy that has constrained MoFA from recruiting new staff – the ministry could only make replacements for retired, resigned, or deceased staff. But even the process for approving replacement staff was a long and frustrating one – for example, the GW DoA made a request in 2012 for staff replacement, but had not yet materialised over a year later.

Financial releases: too little, too late

As noted above, between 2011 and 2012 there was a shift in how DoAs accessed funds within the Item 2 (‘goods and services’) category. Funds for Item 2 slated for the DoAs were released from MoF directly to MMDAs as part of their budget allocations – instead of being channelled through MoFA. The MMDAs in turn released to the DoAs their share of the Item 2 MMDA budget for the DoAs’ planned activities. Although Item 2 constitutes a relatively small proportion of public expenditures in agriculture, it is a category crucial to the functioning and operations of the DoAs. As is apparent from Table 1 above, without Item 2 funds DoA staff were not able to undertake field demonstrations, train farmers, or travel to field sites to conduct any of their key activities with agricultural producers.

A positive finding of the research was that, although Item 2 funds were now being routed through the assembly rather than directly to DoAs, in both case study districts directors confirmed that they had the freedom to utilise the money for the department’s planned activities, without any interference from the assembly or from the higher tiers.

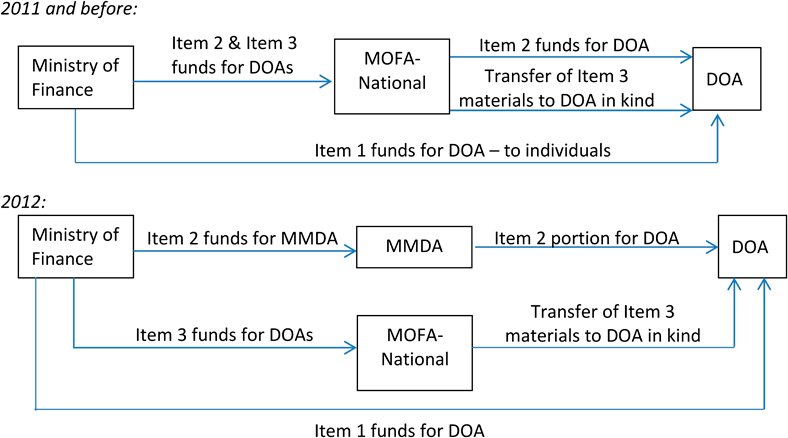

Figure 1 summarises the changes in fund releases to the district DoAs between 2011 and 2012. As noted above, funds for Items 1 and 3 continued to be provided through the central ministries.

Figure 1 Channel of resource provision to district departments of agriculture

However, respondents reported serious issues of inadequate budget and late releases that were affecting agricultural activities in the two local governments. Item 2 releases were supposed to be quarterly, coming in at the beginning of each quarter. Instead, in 2012, the two case study DoAs received only two releases of funds under Item 2 in total. Table 2 displays the planned versus the actual amount and flow of funds in 2012. In the case of both DoAs, two instead of the quarterly four disbursements actually took place, and the amount for the year also fell short: by one-third of the planned funds in GW, and by 40% in SO.9 The nature of ‘too little, too late’ funds apparently followed a rather consistent and similar pattern across different districts. In GW, before 2012, typical Item 2 releases to the district DoA in the municipality were GHC 10,000 per quarter or GHC 40,000 per annum. Thus, as Table 2 shows, the agricultural expenditures for the GW district were cut by more than 40% in 2012.

To illustrate the difficulties this caused, in GW field expenditures for DoA staff in 2012 amounted to GHC 21,600. The 2012 release of about GHC 25,000 was therefore just about enough to pay for these and other expenses of staff, leaving very little for other needs normally covered by Item 2 funds.

In both case studies, the situation had not improved for fiscal year 2013. As of July 2013, neither assembly had received fund releases for that year. Therefore, the DoAs had also not received funds for their activities. The GW DoA director was unable to use his official vehicle because there was no money for fuel, hampering his field supervisory role. The difficulty with inadequate funds and late releases may be particularly acute in the agriculture sector, as it is marked by pronounced seasonality. In critical moments, the two DoA directors were able to operate on credit from suppliers (stationery shops, petrol stations etc.); however, this arrangement was not sustainable because over time suppliers were increasingly reluctant to cooperate, or they raised their prices to accommodate the repayment risk and delays, increasing the cost to the DoAs. Furthermore, not all expenses could not be arranged in this way. The department in SO, for example, was anxiously waiting for money to carry out a vaccination exercise.

Budget inadequacy and delays are not uncommon in Ghana, and indeed many other developing countries. However, respondents perceived the Ghanaian situation as worsening. In the past, MoFA used to regularly release Item 2 funds to the districts for their operations. However, this did not seem to be the case anymore. In the absence of any official explanations, agricultural officials blamed the situation on decentralisation, since the worsening fiscal situation for DoAs and the latest decentralisation reforms coincided in time.

Further investigations may be required to unearth the factors contributing to the worsening budget situation for agriculture at local levels between 2012 and 2013. One possible (albeit speculative) determinant in the more pronounced difficulties of the 2012 and 2013 fiscal years could be related to central government’s election year overspending in 2012. Another possible factor may be the central government’s upward adjustment of public wages through a new personnel policy in 2011. This ballooned budget Item 1, which was estimated to have grown by about 200%. The increase in the wage bill likely negatively affected funds available for Items 2 and 3. Finally, the general finances of the government were facing critical challenges due to macroeconomic factors affecting revenue intake. This also may have contributed to deficiencies in the amount and timing of funds released to DoAs.

The problem of funding coming in ‘too little’ (relative to the approved budget) and ‘too late’ is not unique to district-level operations. Informants in our interviews stated that Item 2 releases of the government of Ghana in 2012 for the entire agricultural sector were only adequate to pay the statutory subscriptions of the ministry, such as Ghana’s annual subscriptions to the Food and Agriculture Organization and the International Fund for Agricultural Development, and for the organisation of the 2012 National Farmers’ Day. Review of government records showed that, therefore, funds released to DoAs through their respective MMDAs principally came from the Can$7 million support from CIDA, which was a subset of CIDA’s approximately Can$18 million support for agriculture in Ghana in 2012. There was apparently no government component in these releases to the DoAs.10 Donor support to Ghana’s agriculture has been quite significant over the years; but relying on donor funding for a critical sector like agriculture is likely to be both unsustainable and risky. The government of Ghana itself should adequately fund the public agriculture sector, so that any donor support is additional rather than a substitute.11

Discussion

This study found that agricultural officers at all levels (national, regional and district) had concerns about the implementation of LI 1961. They stressed that it was important for the relevant government agencies to work together to address these concerns and ensure smooth implementation of LI 1961. Perhaps the key concern was the budget cuts and delays in budget releases. As the deterioration in the timing and the quantity of funds released coincided with the implementation of LI 1961, respondents perceived – rightly or wrongly – a causal link. Secondly, concerns were repeatedly expressed about the transfer of staff from the CS to the LGS. Most informants feared some adverse implications of this transfer for the staff concerned. Thirdly, district DoA staff worried that agriculture would receive less attention after greater prioritisation powers over resources were transferred to assemblies and MMDA chief executives.

These three major concerns were evident in nearly all interviews. The LGS did not act quickly to calm the nerves of its members. It was perceived that staff worries over conditions of service could reduce motivation (possibly from an already low base) and the work ethic of local government staff. In the CS conditions of service, including lines of promotion and succession, had been relatively clear and publicly known to staff, but this was not the case under the LGS. Evidence on the ground also suggested that the orientation and training given by the LGS to ceded staff were inadequate, leaving doubts about their terms of service in the minds of DoA staff.

From the perspective of DoAs, the reality that MMDAs would have to choose between competing priorities (including the district chief executives), especially in the case of the newly created MMDAs, was a source of concern. The DoA officers feared that agriculture could lose out. Whereas in the past DoAs would receive their funds from MoFA and the RADUs, who were already committed to agriculture, DoAs suddenly found themselves having to proactively and repeatedly make the case for increased funding for agricultural activities to their assembly, in competition with other sectors. This appeared to be particularly salient in SO municipality, because the DoA there did not receive any supplementary funds from the assembly, while the DoA in GW municipality did. Lobbying and advocating for one’s sectors, although standard in many budget processes, appeared to be a relatively new necessity for DoAs. Careful consideration is therefore needed of what it takes for DoA staff to become more proactive and oriented to ‘selling’ and advocating the value of agricultural programmes to their assembly, and also what it takes for MMDA leaders, such as the district chief executive, to become more cognisant of which agricultural activities most improve the welfare of district residents.

At the time of this research, some interventions were already underway, such as agriculture-related technical training for DoA staff by MoFA-national. However, this required relevant training modules to equip staff adequately. Beyond technical training, also, it appears critical that DoAs be equipped to assert themselves in budget processes with the MMDAs so that agriculture can be prioritised appropriately. Proactive work by DoA staff would be one approach, to prevent agriculture being short-changed by decentralisation in government resource allocations.

Ghana’s composite budgeting process, after many delays, was finally instituted at district level in 2012. The budgeting is composite in the horizontal sense, in that a comprehensive budget is established across all sectors within a district; however, the 2012 budgeting reform did not also deliver a composite budget in the vertical sense – that is, it did not deliver information on, say, the aggregate budget of the agriculture ministries and departments across all tiers.

Thus from a sectoral, eg agriculture, perspective, the 2012 composite budgeting scheme did not help policy-makers and analysts understand the total amount of funding going to MoFA and its departments, or how this total amount breaks down along administrative and functional lines. The authors acknowledge that the composite budgeting process was promoted primarily to deepen decentralisation, rather than to provide better sectoral information. However, the absence of a full sectoral overview of budgets and funds remained an informational challenge to overcome for those interested in how decentralisation may affect the allocation of resources to agriculture.12 One informant proposed that there was, in fact, a vertical composite budget as of 2013, with Ghana’s gradual adoption of the International Public Sector Accounting Standards through the Ghana Integrated Financial Management and Information System (GIFMIS). The authors were not able to evaluate this assessment in the short period of fieldwork. However, it would be useful to do so and to analyse the nature of this new composite budget structure and the type of breakdowns within a sector that it provides. It will also be important to ascertain the nature of financial accounts (ie of actual expenditures), and whether these are structured in a vertically composite fashion with horizontal breakdown. This is because there is typically a wide gulf between budget amounts and actual expenditure amounts, and thus even a fully composite budget would not be very informative about aggregate agricultural expenditures and their allocation across administrative units and functions.

Concluding remarks and future research agenda

The extent of anxiety of central ministry and DoA staff about the implications of this new chapter in the decentralisation process in Ghana seemed substantial when compared with the magnitude of the reform to date – at least as concerns its fiscal dimensions. Only funds in the Item 2 category of the new three-item system were being transferred directly from the MoF to the MMDAs, with the MMDAs then distributing the amounts received across the district departments. Item 2 funds are those for ‘keeping the lights on’, ie utility payments, stationery, fuel, and other administrative and overhead costs. Nothing about the transfer mechanism of funds for personnel compensation (Item 1) or for project or capital expenditures (Item 3) changed in 2012. Moreover, even though the amounts of Item 2 funds for the DoAs are now channelled through the assemblies along with the Item 2 funds for other district departments, it is not up to the assemblies or district chief executives to decide which department gets what proportion of Item 2 funds. In other words, these funds are not lump-sum unconditional grants to the assemblies for the assembly body, executive committee, or district chief executive to allocate at their own discretion.13

Thus, the anxiety of DoAs seems to reflect not the change in the new fiscal transfer mechanism, but rather the coincidence of the deterioration in the timing and amounts of the Item 2 funds releases with changes in budget processes associated with decentralisation. Our field interviews confirmed that the delays are not due to funds being held up by the assemblies. The delays and the cuts in funding are primarily a result of serious fiscal problems at the central government level.

Generally, the developments in decentralisation in Ghana since the implementation of LI 1961 have heightened interest and fears among government officials and other stakeholders, especially in agriculture, about how the policy shift may affect Ghana’s agricultural performance going forward. With every new implementation step in Ghana’s decentralisation process, there will invariably be teething problems, and time will be needed to assess whether steps impact positively or negatively on agricultural performance. Meanwhile, however, it is important to identify unanswered questions and issues that need further research to better understand the decentralisation policy and to provide direction for its successful implementation, so that it strengthens the quality and quantity of public investments in the agricultural sector.

Acknowledgements

Very helpful comments for this manuscript were received from Todd Benson, Janine Cocker, Shashidhara Kolavalli, and anonymous reviewers for the Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance. Any errors are solely those of the authors.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors acknowledge financial support from the Ghana Strategy Support Programme funded by the United States Agency for International Development, and by the CGIAR research programme Policies, Institutions and Markets.

References

Asante, R. and Debrah, E. (2019) The pitfalls and prospects of decentralisation in Ghana: Implications for the national mobilisation for development agenda. In: Ayee, J.R.A. Politics, governance, and development in Ghana. Lanham/Boulder/New York/London: Lexington Books.

Ayee, J.R.A. (1996) The measurement of decentralisation: The Ghanaian experience 1988–92. African Affairs, 95 (378), 31–50. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a007712

Crook, R.C. (1994) Four years of the Ghana district assemblies in operation: decentralisation, democratisation and administrative performance. Public Administration and Development, 14, 339–364. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.4230140402

Crook, R.C. (2003) Decentralisation and poverty reduction in Africa: The politics of local–central relations. Public Administration and Development, 23, 77–88. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.261

King, R.S., Owusu, A. and Braimah, I. (2013) Social accountability for local government in Ghana. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, (13/14), 61–76. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.v0i13/14.3724

Koranteng, R.O. and Larbi, G.A. (2008) Policy networks, politics and decentralisation policies in Ghana. Public Administration and Development, 28, 212–222. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.497

Mohan, G. (1996) Adjustment and decentralisation in Ghana: a case of diminished sovereignty. Political Geography, 15 (1), 75–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/0962-6298(95)00009-7

1 Deconcentration refers to a phenomenon in which local (or lower-government-tier) departments or offices are established but are still directly affiliated to higher-tier agencies and report to the latter. In contrast, decentralisation describes a situation in which the local departments have some degree of autonomy from higher-tier agencies in political, administrative or fiscal processes (see e.g. http://www.ciesin.org/decentralization/English/General/Different_forms.html).

2 The budget ceiling is the maximum Cedi amount that will be allocated to a ministry under the national budget. These ceilings are usually determined by the cabinet, as officials clarified during field interviews.

3 Because the new government was not elected until mid-December, the 2013 full budget was not approved until March. However, parliament approved the first-quarter budget at the end of 2012.

4 These are contained in the Ghana Shared Growth and Development Agenda 2010–2013 of the central government, and MoFA’s Medium Term Agriculture Sector Investment Plan (2011–2015) and Support to Food and Agriculture Sector Development Policy Programme (2009–2013).

5 However, the ministry may perhaps describe the programmes as ‘decentralised’ in that, for example, fertiliser is submitted to the districts in the context of fertiliser subsidisation schemes.

6 Our field study focused more on the central and district levels, and we conducted only very limited interviews at the regional level.

7 The committee is chaired by the chief executive and has as members the coordinating director, heads of department, and chairpersons of the assembly’s sub-committees.

8 Our interviews did not provide insights on whether such NGO resources are itemised in district budgets. If not captured there, depending on the extent of such engagements, these NGO transfers could constitute a ‘black box’ component in the districts’ resources, potentially leading to an underestimate of those resources. Further investigations are needed to determine the extent local budgets include such transfers from NGOs.

9 A similar pattern obtained in another district in the Greater Accra region, namely Dangbe East. One informant who was posted in that district’s agriculture department stated that there, too, the 2012 financial releases of Item 2 funds for agriculture were made in two tranches instead of the prescribed four. The first release arrived as late as September 2012 (nine months into the fiscal year), and the second in December of that year. The total funds received by Dangbe East’s DoA were only slightly more than half the budgeted amount.

10 At the time of writing, CIDA’s budget support to Ghana’s agriculture has amounted to a total of Can$210 million since 2004, an average of Can$21 million per annum.

11 Donors themselves are doing their part to ensure that the government dedicates adequate funds to agriculture out of its own resources. For example, doing so was a trigger in the support agreement between the government and CIDA, in that the share of government of Ghana discretionary budget going to agriculture in any given year could not be lower than that of the previous year if continued CIDA funding was to be provided. In 2012, this share increased by 2.1% compared to 2011. However, in 2013, the government initially did not meet the target, and MoF had to allocate more government funds to agriculture in order to do so.

12 A public expenditure review, financed by the World Bank with supplemental support from the Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ), was finalised in September 2013, and uses a functional classification of public expenditures. Donors and government are exploring possible ways of conducting an annual expenditure survey, as a follow-up to the public expenditure review. Furthermore, the government of Ghana is developing its charts of accounts to report public spending by functional, as opposed to only economic and administrative, classifications.

13 However, district discretion may be affected by this transfer mechanism if the MMDAs adjust their financing of agriculture out of their local funds, eg DACF or IGF, depending on the amount and timeliness of Item 2 funds to DoAs.