Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, Issue 23, 2020

ISSN 1836-0394 | Published by UTS ePRESS | https://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/journals/index.php/cjlg

RESEARCH AND EVALUATION (PEER REVIEWED)

Promoting inclusive urban economies in a world of changing technology and patterns of trade

Glen Robbins

Urban Futures Centre

Durban University of Technology

and

Policy Research in International Services and Manufacturing (PRISM)

University of Cape Town

South Africa

Email: robbinsdgd@gmail.com

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi23.7547

Article History: Received 15/07/20; Accepted 10/11/20; Published 23/12/20

Citation: Glen Robbins 2020. Promoting inclusive urban economies in a world of changing technology and patterns of trade. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance 2020, 23: 7547, https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi23.7547

© 2020 by the author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Abstract

This paper is a shortened version of a ‘think-piece’ prepared as a contribution to the dialogue at the 2018 Kigali meeting of the Commonwealth Sustainable Cities Network. Its purpose is to highlight both challenges and emerging practices in mobilising local governments, and other stakeholders, including those in other spheres of government and the private sector, towards advancing the scale and scope of local economic development outcomes around critical dimensions of inclusion. The paper is not intended to be an exhaustive report covering all the aspects of contemporary local economic development approaches, but rather to offer selective insights that might contribute to deepening relevant policy and implementation processes in an increasingly urban world.

Introduction

Matters of local economic development (LED) have, for some time, been the subject of enquiry and policy initiatives by a wide range of stakeholders engaged in local and national governance and business. Whilst local actors have always collaborated to improve local economic circumstances, it has really been since the 1960s that local governments have started to try and cohere these efforts into actionable LED plans (Nel 2001). Moreover, the delayed evolution of a local government sphere in many countries contributed to the still modest take up of LED over the last couple of decades. Today, however, there is a diverse global range of LED experiences that can be drawn on, with more and more local governments finding ways to work with partners to secure improved economic outcomes (Rodriguez-Pose and Tijmstra 2005). These LED efforts have in turn increasingly been recognised in local government and urban development policy and have been widely adopted as areas for capacity development. As noted by Rogerson and Rogerson, “planning for local economic development (LED) is now a widespread facet of development planning, particularly in the context of trends towards decentralisation – the deliberate and planned transfer of resources away from central state institutions – and of shifting structures of government and governance” (2010, p. 465).

More recently, local initiatives and policy dialogues1 have displayed a sustained commitment to encouraging collaborative and sustainable practices in evolving urban environments. The growing body of experience, cultivated in many different contexts, has demonstrated an ambition to empower urban actors to achieve levels of impact necessary to help societies make progress (Rodriguez-Pose and Tijmstra 2007). The 2030 Agenda on Sustainable Development and its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs),2 provides a clear indication of the necessity for consistent action to meet goals for more inclusive and sustainable urban environments in the world’s growing cities.

This paper explores how dynamics in trade, the growing spread of digital technologies and changes in finance systems at the local level, might interact with pressures for more sustainable and inclusive LED approaches in cities. It views LED as a dynamic space which must respond to changing economic environments to tackle social and economic exclusion and inequality, and assesses emergent policy frameworks, case studies and a range of academic texts. It draws from a report prepared for the Kigali meeting of the Commonwealth Sustainable Cities Network (CSCN) in late 2018 (Robbins 2018), with a particular focus on experiences across the Commonwealth.3

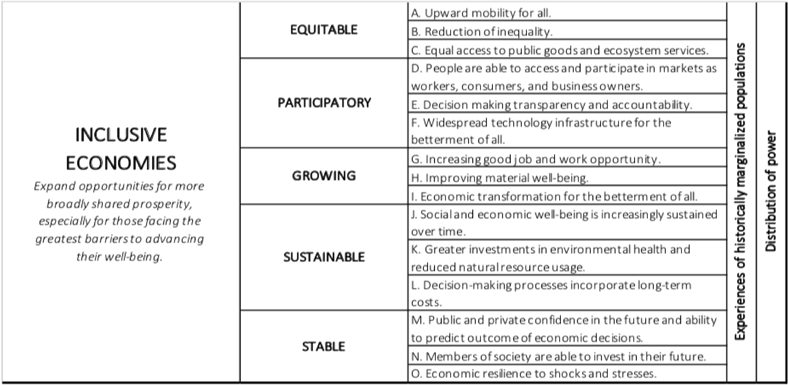

Challenges of inclusion and cities

An inclusive economy is one that “expands opportunities for more broadly shared prosperity, especially for those facing the greatest barriers to advancing their well-being” (Rockefeller Foundation cited in Benner et al. 2018, p. iv). Drawing on experience from around the globe, recent research identifies five features most likely to lead to more inclusive economies (Benner et al. 2018; Benner and Pastor 2016). These relate to the degree to which actors are able to contribute to an environment that is equitable, participatory, growing, sustainable and stable (Benner et al. 2018, p. iv). Figure 1 below sets these out and provides suggestions of indicators that could be used to measure progress. Whilst not developed specifically for urban environments, the framework can be useful in testing whether urban and general economic development programmes are likely to adequately address inclusion.

Figure 1 Framework for more inclusive economies Source: Benner et al. (2018, p. iv)

The push for more inclusive LED is informed by data showing that alongside growth in urbanisation, levels of both absolute and relative inequality remain high or are growing. Although the share of the world’s population living in poverty has shown some decline in recent decades (Beltekian and Ortiz-Ospina 2018), many urban dwellers live on the periphery of economic processes, especially in the global south. According to the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA), in 2018, urban areas across the globe contained 55% of the world’s population, up from 30% in 1950, and by 2050 this is projected to rise to 68% (2018). Whilst North and Latin America, Europe, Australia and New Zealand have the highest shares of population living in cities (between 68% and 82%), Asia is now estimated to have an urban population share of around 50% and is continuing to urbanise. Africa, although currently 43% urban, has experienced the highest rates of urbanisation in the period 1995–2015 (UN Habitat 2016, p. 7).

Changes associated with these processes bring challenges to both citizens living in urban areas and those responsible for the planning and management of cities around the world.4 Challenges include unsustainable patterns of development, accelerating climate change, and damage to the world’s environmental resource base; social pressures from rising urban populations, increased migration; increased demand for basic services and infrastructure; and economic difficulties associated with unemployment and economic volatility.

In many cities problems of exclusion particularly impact women (Chant 2013). Women often have a lower participation rate in the formal labour market, earn less than men for the same work, are more often exposed to vulnerable, informal work, and face structural barriers around access to land, finance and government programmes (Tacoli 2012). Many national, regional and local governments have developed policy responses to address these challenges ranging from reserving seats in local government structures for women,5 through to public sector procurement systems that seek to target women-owned and operated businesses for various public sector contracts.6

Recent migrants to cities may also face exclusion in accessing public services and opportunities for livelihoods, employment and entrepreneurial activity. Factors driving these forms of exclusion can be varied, including, but not limited to, unresponsive administrations and legal systems, barriers associated with societal factors such as those informing gender or other forms of discrimination, and inadequate planning and investment. For instance, Evans (2018) highlights how elites can act to create barriers to tackling forms of inequality, whilst Picketty (2014) points to the power of intergenerational wealth transfers and the associated rising shares of income from investments as generating and sustaining inequality (see also Glaeser et al. 2008).

As processes of urbanisation continue to transform regions, central and subnational governments have embarked on reforms that enable greater levels of decentralised decision-making and action around a wide range of urban matters. Whilst many of these reforms have been quite tentative, some countries have embraced a more significant role for local governments, especially in cities. Rwanda,7 India,8 the Bahamas,9 the United Kingdom (UK)10 and Nigeria (Cheeseman and de Gramont 2017) are examples of countries that have sought, in recent times, to sharpen the urban focus of their administrations and to strengthen local capacity and devolved power in local governments. Developing national policies to support and enable local actors to secure the economic agglomeration potential of urban settlements has also been seen as important, not just for national growth and employment prospects, but also to harness the potential of local actors to contribute to making outcomes more inclusive.

The reforms in these countries and others are dynamic and are not without their challenges, but nonetheless present opportunities for deepening the scope of local action to advance inclusion. For example, the recent adoption of an Integrated Urban Development Framework in South Africa has sought to mobilise improved performance around urban development outcomes in line with the SDGs through combinations of more effective local and national actions (Department of Cooperative Government and Traditional Affairs 2017, p. 8). Representative local government structures in South Africa, such as the South African Local Government Association and networks of local government such as the South African Cities Network were instrumental in building a case for this ambitious framework to guide local, provincial and national government.

Rising levels of inequality in cities have also been observed in more developed economies and in emerging economy countries (UN Habitat 2016). In these contexts, emerging economic dynamics such as those related to trade, information and communications technology (ICT) and finance require attention from local and national policymakers, not just to secure a sustainable local benefit, but also to try and encourage activities that reduce persistent forms of exclusion. To illustrate some of the issues at stake, the following section sets out some of the context of these challenges and highlights possible actions that a range of stakeholders can take, informed by commitments such as those in the New Urban Agenda and the ‘Cardiff Consensus’ of the Commonwealth Local Government Forum (CLGF).

The New Urban Agenda and Sustainable Development Goals

The New Urban Agenda (NUA) emphasises the imperative for urban actors to promote economic development and collaboration between national and local stakeholders to work together for, “inclusive and sustainable economic growth, leveraging urbanisation for structural transformation, high productivity, value-added activities and resource efficiency, harnessing local economies, and taking note of the contribution of the informal economy while supporting a sustainable transition to the formal economy” (UN 2017, p. 7). The NUA goes on to call for “appropriate steps to strengthen national, subnational and local institutions to support local economic development, fostering integration, cooperation, coordination and dialogue across levels of government and functional areas and relevant stakeholders” (UN 2017, p. 15).

The NUA must be seen within the wider Agenda 2030, and the Sustainable Development Goals. SDG 11 (Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable) sets out particular focus areas for urban settlements but it is important to appreciate that, “all of the SDGs have targets that are directly or indirectly related to the daily work of local and regional governments” (UCLG nd, p. 2). Therefore, urban actors need to consider the interactions between SDG 11 and SDG 8 (Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full productive employment and decent work for all). Care also needs to be taken, when considering inclusive urban economic development, to appreciate the scope for integrated action around a number of the SDGs to support deeper developmental impact. For example, SDG 10 (Reduce inequality within and among countries) provides some important target areas that actions in SDG 8 and 11 can contribute to. Equally, local government has a role in ensuring an enabling environment for economic development by providing safe water and sanitation, waste management and other services.

The importance of trade

“Cities have stronger economies when they facilitate international trade and connect to diverse economic clusters in the world, thereby boosting their own local markets and industries” (UN Habitat 2018, p. 14).

The period since the 1980s has seen substantial changes to patterns of global trade, through the process commonly called ‘globalisation’. The decades after World War II were dominated by bilateral arrangements, trading blocs and an array of multi-lateral preferential arrangements that were slowly brought into a common trade governance framework. Initially, protectionist trade policies were almost universally applied through tariffs and quotas or carried out through other policy instruments. Various rounds of multi-lateral trade negotiations led to the common global architecture for trade which concluded in a General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs. This ultimately led towards the generally more liberalised global trade regime that persists today, and is overseen by the World Trade Organisation Although elements of this process are encountering considerable challenges (Rodrik 2017), it has been associated with an unprecedented growth in absolute levels of global trade as well as significantly greater participation in global trade flows by many more countries. Following the major export growth of a number of countries such as South Korea, China and India, many other developing countries as diverse as Lesotho, Bangladesh, Kenya, Mauritius and Malaysia have developed significant export capacity in manufactured goods, albeit with very different levels of value added.11 A number of these countries have also been increasing their services exports in fields such as tourism, health, financial, engineering and technology (Loungani et al. 2017, pp. 7–8).

There is much evidence that growing levels of employment in much of the global south have been associated with rising exports and that improved access to a wider range of more affordable imported goods and services has been important in reducing poverty as well as in raising levels of economic productivity (UN Habitat 2018). However, these processes have also, at times, been somewhat disruptive and brought with them some complex economic adjustments, especially in much of Africa where productivity gains have not been as extensive (UNECA 2017). The participation of more countries in global trading processes has not always supported a move to improved inclusionary and sustainability outcomes and this continues to pose challenges, especially for those locations where trade-linked economic activity is dominant. Issues such as global sourcing standards in the garment sector or emissions requirements for vehicles are just two examples where trade reforms might need to more closely aligned with attaining the SDGs (UNCTAD 2016). This has led some policymakers to increasingly explore what can be done around concerns regarding the often highly uneven distribution of the benefits of production across global value chains (Kaplinsky 2005). However, there have also been examples of countries12 that have made steady progress to overcome these challenges. Working to better understand trade processes and their likely implications for urban areas is particularly important in light of recent moves to initiate new ‘free-trade’ agreements.13

Expanded trade and associated economic shifts have coincided with the growing significance of cities. So-called world/global cities have been identified as playing a critical role in the emerging global economic systems since they host critical infrastructure, systems and institutions that have a global reach and significance. Berube and Perilla (2012, p. 2) point out that “metro areas both facilitate trade, and are themselves an outcome of trade”. Today cities of all sizes play crucial roles as places where trade is facilitated, traded goods and services are consumed or produced and delivered, and services are dispatched. The networks of producers making goods and services, their labour force, suppliers and customers, institutions that enable trade (such as regulatory and financial bodies), and much of the critical infrastructure (airports, ports, major road or rail connections) are concentrated in or near cities. The scale of cities makes them critical market places in many countries and as such producers from surrounding rural areas as well as neighbouring countries keep a close watch on the market potential in cities. Countries with under-developed urban systems are likely to struggle to participate more effectively in trading processes and can also face asymmetries in trading arrangements without the benefits that thriving urban systems can bestow on economies (Lall et al. 2017; UN Habitat 2018). For instance, the UN Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) cites research demonstrating that “in Africa FDI has shown a preference for cities and countries with good access to the continent’s domestic markets” (2017, p. 107).

These connections between cities and trading processes are not without their complexities. Trade activities can also be fickle, with changing circumstances causing sudden shifts in products or services that can cause substantial disruption to established producers and markets. Higher levels of trade can also bring flows of people, not only from surrounding rural areas but also from nearby countries and those of trading partners. This can have a significant impact on demographics, notably in small island states where urbanisation has resulted in major disparities in infrastructure, employment opportunities and other services between communities/islands. Although migration within countries is not new, the rapid urbanisation seen more recently in many island states has also brought with it greater socio-economic and significant environmental challenges, compounded by the impacts of climate change. In addition, economies with a very high dependence on a narrow range of traded goods and/or services can face considerable economic risks unless they are able to encourage diversification. These risks can also be borne unevenly across urban areas and policymakers need to pay close attention to the nature of the threats posed and options for building improved economic resilience that enhances inclusion.

Mayors and city leaders have an important role to play in planning for city development, creating an enabling environment for business, and representing their communities in marketing their cities and towns as centres for investment and economic development.14 Economic development is a major focus for the newly elected Combined Authorities in the UK. Cities such as Manchester15 and Birmingham16 have internationalisation strategies to guide their engagement with strategically chosen countries. In South Africa, the national Department of Trade and Industry regularly invites mayors of cities and districts to participate in trade missions and also schedules visits to municipalities for potential investors. In New Zealand and Canada, mayors and council standing committee chairs regularly act as ambassadors for their communities to forge links and leverage investment internationally.

In most global regions there has been slow yet steady movement to develop better regional trade arrangements. For many countries, the trade experience has tended to be influenced by former colonial relations (UNECA 2017). Neighbouring countries have often had greater trade barriers between each other than they did with distant ex-colonial nations. For example, intra-African trade, whilst growing, remains low, only making up 16% of the share of trade for African countries in 2010–2015 (UNECA 2017, p. 19). As a result countries are starting to prioritise inter-country infrastructure, services and regulatory processes to allow access to each other’s markets and to support opportunities to build regional value chains that might not have been viable within individual countries (UNCTAD 2017).

Engagements on trade matters are often undertaken by national actors, such as central government and industry bodies, without sufficient appreciation of the specific impacts that might arise from place to place. Localities and their regions often have different competitive advantages and varied institutional and infrastructure arrangements (Davis and Dingel 2014, see also Ricardo 2004 [1817]), and some are more proximate to potential trading partners or trade routes than others. Often this gives cities particular trade characteristics that can be leveraged for national gain, but it can also render them exposed if not fully engaged in debates and processes around trade, whether it be something as apparently mundane as border post operations or the debates about reciprocal deals that might be entered into in bilateral or other trade pacts.

Beyond these issues of inter-country trade that dominate global debates, it is also important to appreciate that villages, towns and cities within countries are also increasingly seeing flows of goods and services between one another. Improvements in infrastructure, modernisation of communication systems, the delivery of services such as water and electricity and the growing scale and scope of businesses have seen domestic goods and services trade become critical to national economies. This has undoubtedly caused some disruption as new flows of goods and services might displace older ones, but has also presented growing opportunities for new livelihoods. In many cases secondary cities are playing a key role as they enable a degree of agglomeration of activities than can be very important in servicing this trade and the business processes taking advantage of it. For surrounding rural areas, opportunities exist to take advantage of the improved amenities and markets in these growing urban centres. National polices need to be responsive to the prospects for working with the diversity of formal and informal economic processes associated with internal trade, and seek ways to empower local government and other local actors to support steady improvements in access to economic opportunities as well as improving the productivity of associated businesses.

Key steps towards more inclusive outcomes

What then are some of the actions that policymakers and local actors could consider to support more equitably shared gains from trade-related opportunities?

Knowledge sharing, dialogue and awareness building

It is important that the many different stakeholders involved in local economic processes familiarise themselves with the dynamics of trade within their location, regions and countries, and with national policies that impact on these. National governments would do well to open/improve lines of dialogue with key local actors, especially through local government associations, around their intent and expectations on trade/economic development matters and related factors.

However, local stakeholders can also meet to share their own insights and seek to engage national stakeholders. Here it is important that local actors, including those in organised local government, build awareness around economic processes that are important to different stakeholders in their cities and are likely to be substantially impacted by trade-linked processes. City mayors and councils need appropriate capacity to offer technical support to effectively enable economic development. Initiating discussions with business and industry associations, commissioning research, engaging with their local university and interactions with a wide range of businesses that participate in trade-linked activities are all useful for generating and sharing knowledge and underpinning local planning processes.17 These endeavours should not be one-off events, but rather form part of a regular process of assessment and reflection. Local governments can contribute to improving communication with other spheres of government on challenges and opportunities and can also use the engagements to inform specific programmes and projects that might have wider support.

Information and communications technology

“We commit ourselves to adopting a smart-city approach that makes use of opportunities from digitalization, clean energy and technologies, as well as innovative transport technologies, thus providing options for inhabitants to make more environmentally friendly choices and boost sustainable economic growth and enabling cities to improve their service delivery” (UN 2017, p. 19).

The rapid ongoing evolution of ICT systems, their increasingly global reach, and the take up of the associated technologies by billions of people is a key factor. The World Development Report (World Bank 2016) notes that digital technologies can enhance inclusion by substantially lowering the barriers to access to information for both individuals and firms. A little over a decade or so ago, well over half the world’s population had only limited exposure to advanced telecommunications systems and the information sharing opportunities that are associated with them.

The World Bank estimates that “the number of internet users has more than tripled in a decade—from 1 billion in 2005 to an estimated 3.2 billion at the end of 2015” (World Bank 2016, p. 2). However, the UN’s International Telecommunication Union (ITU) cautions that only around 15% of households in Least Developed Countries (LDCs)18 have internet access at home (ITU 2017). Despite this, the World Bank reports that, “More households in developing countries own a mobile phone than have access to electricity or clean water, and nearly 70 percent of the bottom fifth of the population in developing countries own a mobile phone” (World Bank 2016, p. 2). Urban mobile phone use has driven much of the change in developed and developing countries. For example in Malawi, 20.8% of urban households had access to mobile phones in 2004 and this had risen to 74.7% in 2012, whilst in Nigeria 88.6% of households reported access to a mobile telephone in 2013 (UN Habitat 2016: Statistical Annex).

The unevenness of access and use of ICT is particularly acute when it comes to gender . The ITU reports that “the proportion of women using the internet is 12% lower than the proportion of men using the Internet worldwide”. This is particularly the case in Africa where “the proportion of women using the Internet is 25% lower than the proportion of men using the Internet. In LDCs, only one out of seven women is using the Internet compared with one out of five men” (ITU 2017, p. 2) In addition, almost 90% of youth without access to the internet are in Africa or Asia and the Pacific (ITU 2017). From these figures it is clear that although ICT is increasingly becoming a feature of daily life for most, significant digital divides persist and particular attention is required from policymakers to promote ICT access and literacy for all. For example, UNESCO (2013) points out that ICT offers the prospect for many of the world’s disabled people to connect to services and participate in economic activity.

For city councils, addressing barriers to ICT access is critical because of its potential to generate inclusive social and economic benefits. In environments where many businesses, especially smaller businesses in cities and towns, are disconnected from one another or from their suppliers or markets, ICT can enable local governments to play a coordination role to extend access and encourage take up of new technologies (UN Habitat 2018). However, much in the way of infrastructure for ICT and related services is in the hands of private companies. This requires local authorities to open lines of communication with those companies, who are now providing what is effectively an urban utility of critical importance to the delivery of services by the state, empowering citizens and enabling livelihood and business activities.

Finance

The process of decentralisation to local governments has been accelerated in places by an increasing awareness by central governments of the potential for more effective local administration through decentralisation. Moynihan (2007, p. 59) notes that “Fiscal decentralization is intended to reduce central control in favor of local preferences that foster allocative efficiency”. Demands from local actors in these areas, seeking far greater influence over decisions that affect their lives, has also contributed to driving reform. Key to these processes has been the reform of systems for resourcing local government (Smoke 2017). Although approaches differ substantially, the tendency has been to consider options for enhancing the potential of local revenue generation by municipal authorities as well as improving the funding of urban growth-responsive activities by national and subnational governments. However, as discussed at the Addis Ababa meeting on International Development Finance, many challenges remain in meeting the demands of resourcing activities in increasingly complex urban systems. Nonetheless, the commitments in the Addis Ababa Action Agenda on International Development Finance (UN 2015) provide a basis for developing dialogue between stakeholders through the acknowledgement of ongoing efforts in support of devolution of expenditures and investments. A role is set out for not just public finance reform, but also for cooperation with the private sector to support wider development objectives.

As cities’ contributions to national economic activity increases, and as urban settlements expand in response to this economic activity, the imperative for developing appropriate financing strategies also grows. The increasing complexity of economic activities, and their integration with the global economy, can often require a significant shift in both the focus and the size of local investment in infrastructure and services. Without this cities can encounter a weakening of their productivity and even enter crisis periods, for example in the absence of road maintenance or energy supplies.19 Intergovernmental division of revenue and increased revenue sources for local governments, as well as policies around public-private partnerships and municipal borrowing, are essential elements to help fully realise the potential of city governments to enhance opportunities and to achieve inclusive urban economies.

Recent years have seen the introduction of forms of policy-directed lending such as green bonds, the global environment facility and climate investment funds. These have been introduced to assist city authorities to invest in climate change mitigation/resilience projects and other environmental programmes.20 Innovative financing options may also involve efforts around cost-sharing of some infrastructure through public-private-partnerships with property developers, or build-operate-and-transfer schemes where initial capital costs are carried by the private entity. Enhancing both the financial health and technical capacity of local authorities is a critical step in enabling them to explore and realise some of these options. The NUA highlights the importance of a range of financial investment and support measures to help cities better respond to the demands on them.

Considerable care needs to be taken to consider the impacts of these processes on women and poor and marginalised communities. Fiscal devolution has often been inadequately matched with the required resources and local authorities can face pressure to increase their own revenues. As cities expand it is not uncommon for there to be drives to extend the net of revenue generation to cover more categories of business, often including small and informal businesses. Consideration needs to be given to ensuring that administrative cost burdens on these entities do not damage their prospects to support livelihoods, especially when economic inclusion is being sought. In this regard participatory engagement with an array of economic actors can help identify collaborative financing and operational activities that connect revenues collected with initiatives to improve the business environment and to secure decent working conditions, especially for informal workers (WIEGO nd).21 Mitlin et al. (2018) highlight the importance of community driven finance schemes, such as savings groups or housing associations, to achieving inclusionary outcomes and , such as those linked to savings groups or housing associations. Exploring innovative finance options should therefore also include these community-informed practices so as to more effectively address the needs of the urban poor. The authors point out that local government is often well placed to work with these programmes, highlighting the fact however that many urban local governments lack the funding to meet the needs of all citizens.

Conclusion

In a context where inequality in almost all cities is on the increase (UN Habitat 2016), urban local governments and other stakeholders need to seek out approaches that improve strategic responses to pressing new challenges, whilst also addressing the conditions that continue to reproduce forms of exclusion. Responding to new trading circumstances, promoting the broadening and deepening of ICT adoption, and improving financing opportunities can tackle some of the SDGs, but in the absence of a carefully constructed, collaborative strategy those responses may take cities further away from others. Especially in environments where many economic actors experience limitations on their participation in economic processes – whether this be the exclusion of women from high earning sectors of the economy or a lack of access to skills for smaller enterprises – action is needed to tackle persistent barriers to greater inclusion.

Elected municipal councillors and mayors need to play a particularly important role not only in ensuring innovative and effective local government, but also in advocating the importance of local economic development agendas as part of national policy frameworks. Building partnerships with other local actors and stakeholders in other spheres of government is essential. As noted in the UNECA report those responsible for “national policy levers and implementation instruments” will be crucial in ensuring that countries and local authorities are able to make “urban systems productive” (UNECA 2017, p. 94).

Over half the Commonwealth member states already have an urban population above 50% and over the next decade another handful of countries will reach that level. Most of this urban growth is projected to take place in cities in Asia and Africa. This shift will be deeply influenced by urban economic processes with significant shares of the new growth projected to take place in secondary and intermediary cities. For many fast-growing cities the imperative will be to develop governance structures at the local level to play a deeper role in supporting economic development and encouraging more inclusive outcomes, often with the support of national governments. In already largely urbanised countries, the maturing local government systems are also evolving as new challenges emerge, especially with regard to persistent and, in most cases, rising urban inequalities. Enabled by growing trading links, enhanced ICT platforms and innovative financing opportunities, the possibilities exist to build networks of cooperation across these cities to share knowledge and to learn from one another’s good practices (Lall et al. 2017).

Urban local governments and their leadership need to continue to assert the case for a greater role with respect to urban economic processes, as well as in informing the development of national frameworks that influence those processes. National economic actors should work closely with urban local governments as important development partners with key insights into local priorities and processes. As Satterthwaite points out in his co-authored paper with Mitlin et al. (2018), the current NUA, as a foundational framework for urban development internationally, is somewhat weak on the important leadership role city mayors and local governments will need to play in these processes. Organisations such as CLGF and the CSCN can play a critical role in supporting this essential leadership mandate and help urban local governments respond to the challenges of urban economic inclusion being faced the world over.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

This paper was commissioned by the Commonwealth Local Government Forum with the assistance of the UK Department for International Development (DFID) and Microsoft, and an earlier version was produced as the background paper to the 2018 Commonwealth Sustainable Cities Network meeting, held in Kigali, Rwanda, 18–19 September.

References

Bahamas Information Services. (2018) Public consultation continues for introduction of local government structure in new providence. Available at: www.bahamas.gov.bs/wps/portal/public/gov/government/news/public consultation continues for introduction of local government structure in new providence [Accessed 11 September 2018].

Beltekian, D. and Ortiz-Ospina, E. (2018) Extreme poverty is falling: How is poverty changing for higher poverty lines? Available at: https://ourworldindata.org/poverty-at-higher-poverty-lines

Benner, C., Giusta, G., McGranahan, G. and Pastor, M. (2018) Creating more inclusive economies: Conceptual, measurement and process dimensions. Final report for The Rockefeller Foundation. Available at: http://inclusiveeconomies.org [Accessed 12 August 2018].

Benner, C. and Pastor, M. (2016) Inclusive economy indicators. Report produced for The Rockefeller Foundation. Available at: https://everettprogram.app.box.com/s/1crotb17fvhg421xm0vk10ojaijldeiw [Accessed 12 August 2018].

Berube, A. and Parilla, J. (2012) Metro trade: Cities return to their roots in the global economy. Metropolitan Policy Programme at Brookings. Available at: www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/26-metro-trade.pdf [Accessed 3 June 2017].

Chant, S. (2013) Cities through a ‘gender lens’: A golden ‘urban age’ for women in the global South? Environment and Urbanization, 25 (1), 9–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247813477809

Cheeseman, N. and de Gramont, D. (2017) Managing a mega-city: Learning the lessons from Lagos. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 33 (3), 457–477. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/grx033

Cities Alliance. (2018) Public space as a driver of equitable economic growth: Policy and practice to leverage a key asset for vibrant city economies. Report produced for global policy dialogue organised by the Cities Alliance Joint Work Programme (JWP) for Equitable Economic Growth in Cities, 9th Session of the World Urban Forum, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 7–13 February 2018.

Commonwealth Local Government Forum. (CLGF) (2011) Cardiff consensus for local economic development. Available at: www.clgf.org.uk/default/assets/File/CLGF_statements/2011%20Cardiff%20consensus%204pp.pdf [Accessed 13 August 2018].

Commonwealth Local Government Forum. (CLGF) (2018) Commonwealth Local Government Handbook 2017–18. London: CLGF: Available at: www.clgf.org.uk/resource-centre/clgf-publications/country-profiles [Accessed 6 September 2018].

Davis, D.R. and Dingle, J. I. (2014) The comparative advantage of cities. NBER Working Paper No. 20602. Available at: www.nber.org/papers/w20602 [Accessed 11 September 2018].

Department of Cooperative Government and Traditional Affairs. (2017) Integrated urban development framework. Pretoria: CoGTA. Available at: www.cogta.gov.za/?programmes=the-integrated-urban-development-framework-iudf [Accessed 23 August 2018].

Economic Times. (2018) Delhi launches doorstep delivery of public services. 10 Sept 2018.

Evans, A. (2018) Politicising inequality: The power of ideas. World Development, 110, 360–372.

Garschagen, M., Porter, L., Satterthwaite, D., Fraser, A., Horne, R., Nolan, M., Solecki, W., Friedman, E., Dellas, E. and Schreiber, F. (2018) The New Urban Agenda: From vision to policy and action – will the New Urban Agenda have any positive influence on governments and international agencies?/Informality in the New Urban Agenda: From the aspirational policies of integration to a politics of constructive engagement/ Growing up or growing despair? Prospects for multi-sector progress on city sustainability under the NUA/Approaching risk and hazards in the New Urban Agenda: A commentary/Follow up and review of the New Urban Agenda. Planning Theory & Practice, 19 (1), 117–137, https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2018.1412678

Glaeser, E., Resseger, M. and Tobio, K. (2008) Urban inequality. National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Working Paper 14419. Available at: http://www.nber.org/papers/w14419 [Accessed 12 November 2018].

International Telecommunication Union. (ITU) (2017) ICT facts and figures 2017. Available at: www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/facts/default.aspx [Accessed 14 August 2018].

Kaplinsky, R. (2005) Globalisation, poverty and inequality. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Lall, S., Henderson, J. and Venables, A. (2017) Africa’s cities: Opening doors to the world. Washington DC: World Bank. Available at: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/25896?locale-attribute=es [Accessed 15 August 2018].

Loungani, P., Mishra, S., Papageorgiou, C. and Wang, K. (2017) World trade in services: Evidence from a new dataset. Available at: http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/815061480467907896/World-Trade-in-Service-February-2017.pdf [Accessed 22 December 2020].

Mitlin, D., Colenbrander, S. and Satterthwaite, D. (2018) Editorial: Finance for community-led local, city and national development. Environment & Urbanization, 30 (1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247818758251

Moynihan, D. (2007) Citizen participation in budgeting: Prospects for developing countries. In: Shah, A. (ed.) Participatory budgeting, (pp. 55–87).Washington DC: World Bank.

Nel, E. (2001) Local economic development: A review and assessment of its current status in South Africa. Urban Studies, 38 (7), 1003–1024. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980120051611

Piketty, T. (2014) Capital in the 21st Century. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Ricardo, D. (2004) [1817] On the principles of political economy and taxation. New York: Dover.

Robbins, G. (2018) Inclusive urban economies. A background paper for the Commonwealth Sustainable Cities Network meeting, Kigali, 18–19 September 2018. London: CLGF. Available at: http://www.clgf.org.uk/default/assets/File/CSCN/CSCN2018_Inclusive_Urban_Economies.pdf?

Rodríguez-Pose, A. and Tijmstra, S. (2005) Local Economic Development as an alternative approach to economic development in Sub-Saharan Africa. World Bank. Available at: http://knowledge.uclga.org/IMG/pdf/ledn_sub-saharan_africa.pdf

Rodriguez-Pose, A. and Tijmstra, S. (2007) Local economic development in sub-Saharan Africa. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 25, 516–536. https://doi.org/10.1068/c5p

Rodrik, D. (2017) Straight talk on trade: Ideas for a sane world economy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Rogerson, C. and Rogerson, J. (2010) Local economic development in Africa: Global context and research directions. Development Southern Africa, 27 (4), 465–480. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2010.508577

Mitlin, D., Colenbrander, S. and Satterthwaite, D. (2018) Editorial: Finance for community-led local, city and national development. Environment & Urbanization, 30 (1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247818758251

Smoke, P. (2017) Fiscal decentralisation frameworks for Agenda 2030: Understanding key issues and crafting strategic reforms. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, (20), 3–23. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.v0i20.6024

Tacoli, C. (2012). Urbanization, gender and urban poverty: Paid work and unpaid care work in the city. Urbanisation and Emerging Population Issues Working Paper 7. International Institute for Environment and Development and the United Nations Population Fund. Available at: https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/resource-pdf/UEPI%207%20Tacoli%20Mar%202012.pdf [Accessed 13 June 2018].

United Cities and Local Government. (No date). The Sustainable Development Goals: What local governments need to know. Available at: www.uclg.org/sites/default/files/the_sdgs_what_localgov_need_to_know_0.pdf [Accessed 31 August 2018]

United Nations. (UN) (2015) Addis Ababa action agenda of the third international conference on financing for development (Addis Ababa Action Agenda). Outcome document adopted at the Third International Conference on Financing for Development (Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 13–16 July 2015) and endorsed by the General Assembly in its resolution 69/313 of 27 July 2015. Available at: www.un.org/esa/ffd/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/AAAA_Outcome.pdf [Accessed 16 August 2018].

United Nations. (UN) (2017) New Urban Agenda. Adopted at the Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development (Habitat III). Available at: http://habitat3.org/the-new-urban-agenda [Accessed 12 August 2018].

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. (UNCTAD) (2011) Review of the technical cooperation activities of UNCTAD and their financing. Available at: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/wpd232_en.pdf

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. (UNCTAD) (2016) Trading into sustainable development: Trade, market access, and the Sustainable Development Goals. Available at: http://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/ditctab2015d3_en.pdf [Accessed 12 September 2018].

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. (UN DESA) (2018) World urbanization prospects: The 2018 revision (key facts). Available at: https://esa.un.org/unpd/wup/Publications/Files/WUP2018-KeyFacts.pdf [Accessed 15 August 2018].

United Nations Economic Commission for Africa. (UNECA) (2017) Economic report on Africa 2017: Urbanization and industrialization for Africa’s transformation. Addis Ababa: UNECA. Available at: www.uneca.org/publications/economic-report-africa-2017 [Accessed 10 August 2018].

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (UNESCO) (2013) UNESCO global report: Opening new avenues for empowerment: ICTs to access information and knowledge for persons with disabilities. Available at: www.unesco.org/new/en/communication-and-information/resources/publications-and-communication-materials/publications/full-list/unesco-global-report-opening-new-avenues-for-empowerment-icts-to-access-information-and-knowledge-for-persons-with-disabilities [Accessed 18 August 2018].

UN Habitat. (2016) World cities report 2016: Urbanization and development emerging futures. Nairobi:.UN Habitat.

UN Habitat. (2018) The state of African cities 2018: The geography of African investment. Available at: https://unhabitat.org/the-state-of-african-cities-2018-the-geography-of-african-investment

Vyas-Doorgapersad, S. and Kinoti, A. (2015) Gender-based public procurement practices in Kenya and South Africa. African Journal of Public Affairs, 8 (3).

Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing. (WIEGO) (No date) Accra. Available at: https://www.wiego.org/accra

World Bank. (2016) World development report 2016: Digital dividends. Washington DC: World Bank. Available at: www.worldbank.org/en/publication/wdr2016 [Accessed 12 August 2018].

World Bank. (2017) Reshaping urbanization in Rwanda: Economic and spatial trends and proposals. Available at: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/295261513850521418/pdf/122185-WP-P157637-PUBLIC-Note-4-Rwanda-Urbanization-12-08-17.pdf

1 Highlighted for example, by the 2011 Cardiff Consensus for Local Economic Development (see CLGF 2011: www.clgf.org.uk/what-we-do/local-economic-development).

2 Adopted by the United Nations members states in September 2015 www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals

3 See www.clgf.org.uk .

4 As is noted in the World Cities Report 2016, “although urbanization has the potential to make cities more prosperous and countries more developed, many cities all over the world are grossly unprepared for the multidimensional challenges associated with urbanization” (UN Habitat 2016, p. 5).

5 Countries making these shifts include Bangladesh, India, Kenya, Lesotho, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Uganda and Rwanda (CLGF 2018, p. vii) www.clgf.org.uk/default/assets/File/Country_profiles/Women_councillors2018.pdf

6 For example in Kenya and South Africa (Vyas-Doorgapersad and Kinoti 2015).

7 The Rwandan government, with assistance from development partners, have been providing significant investments in the country’s six secondary cities (see World Bank 2017).

8 The government of Delhi is initiating various innovations in local services, such as the move to deliver public services to citizens’ doorsteps (see Economic Times, 10 Sept 2018).

9 The Bahamas held a public consultation on the introduction of local government (see Bahamas Information Services 28 August 2018).

10 Combined Authorities; as of September 2018, nine combined authorities have been established, of which seven have secured devolution deals and six have in place directly elected mayors. For more information, see www.local.gov.uk/topics/devolution/combined-authorities

11 According to World Bank data (https://data.worldbank.org/) these countries grew their merchandise exports (current 2020 US Dollars) between 2000 and 2018 in the following manner: Bangladesh from USD 6,398 billion to USD 39,252 billion; Ghana from USD 1,671 billion to USD 14,943 billion; Malaysia from USD 98,229 billion to USD 218,130 billion; and Tanzania from USD 734 million to USD 4,041 billion.

12 For example, Ethiopia is often noted as providing important insights in how countries can start to secure important gains from processes of globalisation (UNECA 2017).

13 Such as those associated with Continental Free Trade Areas (CFTAs) in Africa and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership CPTPP.

14 With the support of a number of partners including UNCDF, Cities Alliance and a number of government agencies and departments, secondary cities in Uganda recently held their inaugural Uganda Urban Expo under the theme ‘Becoming investment ready: Unveiling the business and investment potential of secondary cities’ (Cities Alliance 2018).

15 www.marketingmanchester.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Internationalistion-Report.pdf

16 https://distinctlybirmingham.com

17 The eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality in South Africa is a unit of the municipality where programmes are jointly developed with a number of local tertiary institutions. Apart from an annual research conference, it organises, together with its partners – a series of special seminars and workshops to share the knowledge of the municipality and researchers within the municipality and with stakeholders outside the municipality – including outside South Africa. As an information and knowledge sharing platform it has reached out to other stakeholders in the city, including those in the private sector and in civil society. (Further case study information - http://www.mile.org.za/Pages/default.aspx)

18 Which includes Gambia, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia in the Commonwealth (ITU 2017).

19 See the example of Kigali, Johannesburg, Cairo, the Abidjan-Lagos corridor discussed in UN Habitat (2018).

20 The City of Cape Town raised R1bn (US$66m) through the auctioning of a green bond in 2017 to help finance projects ranging from the procurement of electric busses to water management projects. www.fin24.com/Economy/city-of-cape-town-pleased-with-success-of-first-green-bond-20170712

21 As part of targeted projects supported by various local and international organisations, street vendors in Accra carried out their own research on barriers to decent work conditions and improved incomes. The findings were tabled by representatives of the street vendors’ associations at the Accra Municipal Assembly to propose priority areas for action by the municipality. Further information, see http://www.wiego.org/wiego/focal-cities-accra