Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance

Issue 24

June 2021

POLICY AND PRACTICE

Examining Citizens’ Trust In Local Government Institutions: A Focus on Upazila Parishads (Sub-District Councils) In Bangladesh

Niaz Ahmed Khan

Department of Development Studies, University of Dhaka, Dhaka 1000, Bangladesh, niaz.khan@yahoo.com

Jannatul Ferdous

Department of Public Administration, Comilla University, Cumilla 3506, Bangladesh, jannat.lata@yahoo.com

Md Imran Hossain Bhuiyan

Department of Development Studies, University of Dhaka, Dhaka 1000, Bangladesh, imran.bhuiyan@du.ac.bd

Corresponding author: Md Imran Hossain Bhuiyan, Department of Development Studies, University of Dhaka, Dhaka 1000, Bangladesh, imran.bhuiyan@du.ac.bd

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi24.7275

Article History: Received 14/06/21; Accepted 30/05/21; Published 28/06/21

Citation: Khan, N. A., Ferdous, J. and Bhuiyan, M. I. H. 2021. Examining Citizens’ Trust In Local Government Institutions: A Focus on Upazila Parishads (Sub-District Councils) In Bangladesh. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, 24, 136–145. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi24.7275

© 2021 by the author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Abstract

Against a backdrop of strikingly limited research on the subject, this article examines citizens’ trust in upazila parishads (UzPs) – a historically significant form of local government institution (LGI) in Bangladesh. A set of indicators has been developed that help to evaluate citizens’ trust in these LGIs. Alongside secondary literature and official document reviews, a mixed-method approach was adopted for empirical data collection combining quantitative (a questionnaire targeting a cross-section of service recipients) and qualitative ( key informant interviews with LGI service providers) methods. The results revealed a poor level of citizen trust in UzPs, as the majority of respondents expressed dissatisfaction with their performance. This low level of citizens’ trust was attributable to such reasons as delays in service delivery, dishonest and unfair practices, and disrespectful treatment by service providers. From a ‘supply-side’ perspective, service providers mentioned many constraints to good performance including the challenge of meeting growing demand with inadequate resources, frequent staff transfers, limited scope for training on modern technologies, and pressure and interference from influential elites.

Keywords

Trust, Performance; Local Governance; Local Government Institution; Upazila Parishad; Bangladesh

Introduction

In recent years, government institutions in developing countries have undergone reforms spurred by factors and processes such as globalisation, financial reforms, democratisation, and pressure for increased participation in policy-making and implementation by actors from the private and third sectors (Mzee 2012). Government institutions are expected to develop trustful relationships with non-government actors to administer these transformations, reinforce legitimacy, and improve partnerships through which they can effectively execute public policies (Jamil and Askvik 2016). Against this backdrop, it is argued that raising citizens’ trust in government organisations is a prerequisite for good governance and fruitful execution of policies (Kim 2005). A well-performing democratic system is usually built upon citizens’ trust, without which social cohesion may decline. It is, therefore, widely accepted that trust is a significant indicator for revealing how well government institutions are dealing with the common issues they face (Jamil and Askvik 2013).

Among a wide array of public institutions, local government institutions (LGIs) are broadly responsible for delivering basic public services with the goal of ensuring citizens’ well-being at the local level (Makorere 2012). Across the multiple tiers of local government in Bangladesh in both rural and urban areas, LGIs deliver a wide range of public services to local citizens. This article explores the level of citizens’ trust in a significant form of LGI – the upazila parishad (sub-district council), by focusing on identifying and defining a critical factor that affects citizens’ level of trust, namely LGIs’ performance in service delivery.

Institutional trust and performance in service delivery

Trust can be described as an effective way of lessening transaction expenses in any societal, financial and political affiliation (Fukuyama 1995). It is considered one of the significant assets that an organisation can hold. Trust in public institutions promotes democratic involvement, financial sustainability and effective governance. In its absence, mistrust between the government and its people can lead to an absolute refusal by citizens to partake in or approve government activities (Parker et al. 2008). Good performance by government organisations is necessary to execute the preferred policies, ensure enhanced service delivery and, ultimately, gain citizens’ trust. If public services can be delivered efficiently and people’s living standards improved, citizens’ trust in government entities can simultaneously increase (Lame and Papa 2016).

From a theoretical perspective, trust in government organisations may be viewed as an outcome of government performance, and likewise institutional trust as an outcome of institutional performance (Baniamin et al. 2019). It may be argued, therefore, that trust and mistrust in government organisations are sensible reactions by people to the performance of those organisations (Liu 2015). Mistrust in government is frequently attributed to lower-than-expected performance by government agencies (Yang and Holzer 2006). At the sub-national and local level, citizens’ trust in government institutions is mainly affected by ‘micro’ performance issues related to variations in service delivery (Bouckaert and van de Walle 2003a). In this regard, researchers have used various indicators to evaluate the performance of an organisation. Evans (2012) focused on the quality aspect of performance, which can be measured through such indicators as excellence, reliability, reduction of waste, promptness of delivery, adequacy of policies and processes, delivering a good product, completion of tasks on time and client satisfaction. Looking from a different perspective, to consider personal attributes of government institution staff, Askvik and Jamil (2013) used indicators such as credible commitments, benevolence, honesty, competence and fairness to evaluate trust in public institutions. Parker et al. (2008) similarly emphasised individual characteristics, including the knowledge and capability of an administrator and their performance as a ‘duty-bearer’, to measure the trustworthiness of an organisation.

LGIs in the Bangladesh context

Bangladesh has a long and chequered history of forming and encouraging (or otherwise) LGIs (Khan 2016). The constitution of the country confirms the legal status of local government, and several Acts promulgated by parliament spell out mandates and pertinent features of LGIs (Khan 1997). Currently, there are two distinct groups of LGIs in Bangladesh: rural and urban. In the rural context, local government follows a hierarchical scheme involving three layers: the lowest tier union parishad, the sub-district upazila parishad (UzP), and the district-level zilla parishad. Meanwhile, urban local government consists of city corporations and pourashavas (municipalities) (Panday 2011).

This study is concerned with citizens’ trust in UzPs, based on their performance. This middle-layer local government unit was launched in the early 1980s by the non-democratic regime led by an army general. Subsequently, after the fall of that regime in 1990, the new politically elected government discontinued selected major policies of the erstwhile regime including the UzP. However, the UzP was reinstated by the next political government in 2009, after a break of some 18 years (Panday 2011). The UzP continues to be a significant layer of the political–administrative interface in delivering government programmes, as it provides a connection between central and local government (Rahman 2012). Currently, UzPs are headed by elected political representatives (Ahmed et al. 2011), while an administrative cadre officer is posted as the upazila nirbahi (sub-district executive) officer (UNO) and secretary to the UzP. The UNO monitors and coordinates various programmes and services of the ‘line departments’ (ie the service-providing agencies that sit under various ministries). In the UzP there are about 17 line departments providing various services to citizens (Yasmin et al. 2017). The UzP also has several standing committees which monitor the activities of the line departments and its core developmental activities. Key responsibilities of the UzP and the associated line departments include programmes related to infrastructure development; agricultural development; social protection; and social services – notably health and education (Habib 2009).

Methodological considerations

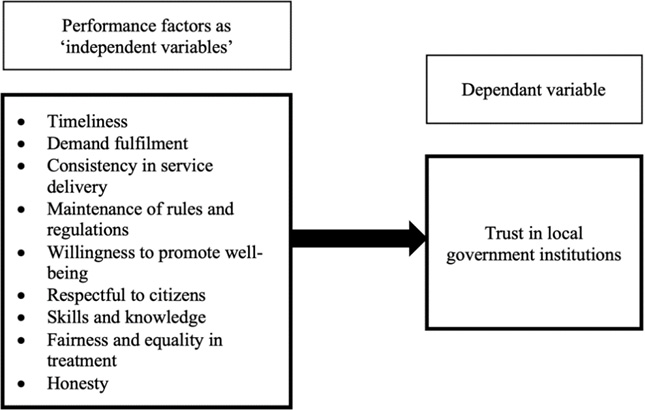

In this paper, ‘trust’ is assessed in relation to the performance of the participating LGIs in service delivery. In this regard, the study examined the activities and performance of each UzP studied along with its most prominent line departments in delivering and monitoring such major public services as health, education, family planning, land registry services, agriculture, fisheries work, livestock management and social protection. Drawing on the key literature (Mark and Nayyar-Stone 2002; Bouckaert and van de Walle 2003b; Aguinis 2009; Cheema and Popovski 2010; Evans 2012; Jamil and Askvik 2015), the authors judged the factors of timeliness, demand fulfilment, consistency, maintenance of rules and regulations, willingness to promote well-being, respectfulness to citizens, skills and knowledge, fairness and equality in treatment and honesty as the most significant in influencing the level of trust in LGIs. These factors were therefore used to draw up the study’s analytical framework (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Analytical framework of the study

Source: Developed by the authors based on Mark and Nayyar-Stone (2002); Bouckaert and van de Walle (2003b); Aguinis (2009); Cheema and Popovski (2010); Evans (2012); Jamil and Askvik (2015)

The study adopted a mixed-methods approach combining both qualitative and quantitative elements in the collection and analysis of primary data. A questionnaire survey was conducted to collect quantitative data from citizens who had recently solicited and received services from selected UzPs. Additionally, key informant interviews (KIIs) were conducted to capture qualitative data from the service providers and local government representatives to understand the ‘supply-side’ perspective. Respondents for the survey and the KIIs were chosen purposively from five selected UzPs. Survey respondents were selected based on their (reported) history and experience of recent interactions with their respective UzPs, and their willingness to respond. The research was conducted intermittently between September 2019 and January 2020.

The selected UzPs were Adarsha Sadar, Laksham, Chowddagram, Chandina and Sadar Dakshin, all within the Cumilla district in Bangladesh. They were selected on the basis of accessibility to the researchers, a relatively long history of establishment and consolidation, and variations in both geography and territorial size. A total of 100 respondents were surveyed from the selected UzPs, and 15 key informants were interviewed. In terms of gender composition, 70 of the survey respondents were male and 30 were female, while 10 of the key informants were male and five were female. Initially the questionnaire was distributed among 129 targeted respondents. Nine persons declined to respond citing ‘personal reasons’ while 12 questionnaires were found incomplete, and, among the rest, eight did not pass the quality control criteria. The response rate, thus, was about 78%. Following the principle of ‘methodological pluralism’ (Khan 2018), the data collected through both quantitative and qualitative methods was triangulated and checked for validity.

Key Findings

This section presents the major findings of the study in two sub-sections. The first sub-section focuses on observations from the questionnaire survey, while the second captures views arising out of the KIIs. Quantitative data, collected from the service recipients through the questionnaire survey, is presented statistically in the first sub-section.

Observations from the survey

To examine the level of citizens’ trust in their LGI, data was collected by developing a six-point Likert-type scale to record responses of service recipients for each of the variables identified in the analytical framework. The responses relate to the overall experience of the respondents regarding commonly received services, notably health, land registry activities, agriculture and social protection. The Likert-type scale allowed categorisation of responses as ‘excellent’, ‘very good’, ‘good’, ‘average’, ‘bad’, and ‘very bad’ with descending values of 6 to 1 respectively. The first three categories from ‘excellent’ to ‘good’ denote a positive evaluation, while the other three denote a negative evaluation against the variables. The six-point scale was developed after careful pre-testing of the survey questionnaire on two pilot groups in two selected rural locations. The purpose of the pre-testing exercise was to ensure that the respondents understood the questions and could complete the response within the stipulated time. The survey responses are presented in Table 2.

Based on the methodology described above, the survey results indicate the extent to which various performance factors may affect citizens’ trust. For example, to measure ‘timeliness’, the survey covered services such as national identity card registration, land registration and birth registration. The data shows that 40% of respondents rated the timeliness of service delivery from ‘good’ to ‘excellent’, while 60% rated it as ‘average’ to ‘very bad’.

| Criteria | Excellent | Very good | Good | Average | Bad | Very bad |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timeliness | 5% | 15% | 20% | 20% | 30% | 10% |

| Demand fulfilment | 5% | 19% | 14% | 33% | 7% | 22% |

| Consistency in service delivery | 5% | 10% | 25% | 40% | 15% | 5% |

| Maintenance of rules and regulations | 5% | 10% | 25% | 40% | 15% | 5% |

| Willingness to promote well-being | 15% | 30% | 20% | 17% | 13% | 5% |

| Respectfulness to citizens | 5% | 12% | 10% | 33% | 24% | 16% |

| Skills and knowledge | 10% | 17% | 22% | 28% | 20% | 3% |

| Fairness and equality in treatment | 7% | 12% | 10% | 29% | 27% | 15% |

| Honesty | 6% | 13% | 20% | 35% | 11% | 15% |

Unfair as well as corrupt practices and disrespectful behaviour towards service recipients emerged as the major reason for citizens’ dissatisfaction with the performance of their LGI, which over time are likely to erode trust. One critical concern expressed by most respondents was the lack of attention or sensitivity on the part of LGI service providers to the needs and voices of service recipients. Moreover, consistency in service delivery is often found to be lacking, and respondents candidly noted that many service providers do not have the skills or knowledge to deliver services in an efficient and consistent manner. Of all the indicators, however, the most negative rating went to the way service providers treat recipients. Getting fair and respectful treatment from service providers is what recipients are mostly concerned about, and in dire need of. Respondents mentioned that the standard rules and regulations are often not followed properly during the delivery of services and bypassed in dealings with influential local people. By contrast, a large segment of common people experience maltreatment by administrative officials.

With regard to fulfilling citizens’ demands for services, 62% of respondents rated the performance of the LGIs from ‘average’ to ‘very bad’. It is heartening to note, however, that the majority of the service recipients still remain optimistic about the willingness of the service providers to improve the standard of service delivery. Some 65% of respondents believe that the institutional actors at their LGI are committed to ensuring the well-being of the citizens if provided with sufficient resources.

Observations from the interviews

The qualitative data collected through the KIIs has been analysed by applying the narrative analysis method (Allen 2017) and is summarised in this sub-section to complement the findings from the quantitative data. The interview responses capture the ‘supply-side’ perspective of service providers and LGI representatives to explain their performance in service delivery. The findings reveal that LGIs are struggling to meet rising demand for services among citizens, whose awareness level has risen significantly in recent years. Key informants noted that this has been driven by exponential growth in the use of the internet and social media, awareness-raising activities by non-government organisations, and improved transportation facilities in rural areas. Service providers point to the insufficiency of financial and human resources in the operational sections and line departments of their UzPs, which thwarts their capacity to deliver various services in a timely and efficient manner. Moreover, the frequent transfer of government officials restricts their ability to maintain consistency in service delivery and causes poor performance. The service providers also refer to the undue influence of political elites, which often demand that in cases that affect them the local administration deviate from standard rules and procedures. Furthermore, the lack of training on modern technologies, and the difficulty in effectively integrating information and communication technologies (ICT) into the routine delivery of services, contribute to a low level of skills and knowledge.

The need to serve a vast and rapidly growing population with limited human, technical and financial resources creates a vicious cycle of ‘lower level of performance – lower level of trust’, in which service delivery becomes delayed, inconsistent and inequitable. Moreover, the pressure from locally influential people who demand preferential access to services further limits the capacity of LGIs to provide services to all citizens fairly, promptly and respectfully.

Responding to these key constraints facing service providers, the key informants suggested the following policy measures. First, the quantity and quality of human resources at the LGIs need to be enhanced through systematic strategic planning and review of needs and capacities. As well as LGIs recruiting more qualified staff, the existing service providers need to be trained in ICT and other relevant technologies to improve the service delivery process. Second, more ICT tools need to be deployed in relevant sections and line departments to ensure integration with modern technologies and allow timely and efficient delivery of services. Third, the allocation of resources between different offices within the LGIs needs to be rationalised through a central strategic planning and review process by the relevant ministries (especially those of local government, finance and public administration). Fourth, innovative means of recruiting and engaging more service providers need to be explored; this could include contract or fixed-term engagements based on specific skills and expertise, and/or partnerships with relevant non-government and private sector actors. Fifth, transferring provision of some basic services (notably primary health, agricultural extension and social welfare) to the village level, by setting up local offices at the union parishad, could offset the high demand for services from the UzP.

Summing-up

This study examined citizens’ trust in LGIs in the context of a developing country (Bangladesh), through the lens of local citizens’ (service recipients) satisfaction regarding the LGIs’ performance in delivering services. A set of performance factors was identified, and citizens’ trust in the LGIs was assessed by evaluating the responses of service recipients against those variables. The findings (following a careful triangulation of quantitative and qualitative data) show that a large segment of the population remains dissatisfied with the extent of the services and the manner of their delivery, the treatment of service recipients by providers, and the quality of the services. This dissatisfaction with the performance of LGIs is expected to be correlated with lower levels of citizen trust in those institutions.

The majority of survey respondents expressed dissatisfaction about delays in service delivery, dishonest and corrupt practices, and unfair and disrespectful treatment by service providers. From the ‘supply side’, service providers reported the challenge of serving a vast population with inadequate human, technical and financial resources as the critical constraint in meeting citizens’ expectations for effective service delivery. Furthermore, frequent transfers of officials at the LGIs, limited scope for training on modern technologies, and local pressure and interference from influential elites seeking preferential access to services also contribute to ineffective service delivery. As a result, there remains a considerable gap between the expectations of citizens and the performance of LGIs, which needs to be addressed. Systemic institutional reforms (including strategic review and planning) and improvements in human, financial and technological resources are needed to help enhance the performance of the LGIs.

The scope of this study was limited to a particular tier of local government. There is scope for further research concerning citizens’ trust in other tiers of LGIs (eg at the district and village levels) and in a variety of contexts (eg urban, rural, and diverse socio-economic and geographical settings). Moreover, this study was restricted to the evaluation of institutional trust in terms of the performance of UzPs in providing selected public services. The issues and implications of trust could be examined from other perspectives, and research regarding citizens’ trust in other public and parastatal organisations beyond LGIs may be very worthwhile. Overall, the authors recommend that questions concerning citizens’ trust in government institutions receive fuller and immediate attention from both academics and practitioners.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

Aguinis, H. (2009) Performance management. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall.

Ahmed, N., Ahmed, T. and Faizullah, M. (2011) Working of upazila parishad in Bangladesh: A study of twelve upazilas. Dhaka: UNDP.

Allen, M. (2017) The SAGE encyclopedia of communication research methods. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483381411.n368

Askvik, S. and Jamil, I. (2013) The institutional trust paradox in Bangladesh. Public Organization Review, 13 (4), 459–476. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-013-0263-6

Baniamin, H.M., Jamil, I. and Askvik, S. (2019) Mismatch between lower performance and higher trust in the civil service: Can culture provide an explanation? International Political Science Review,41 (2), 192–206. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512118799756

Bouckaert, G. and van de Walle, S. (2003a) Quality of public service delivery and trust in government. In: Salminen, A. (ed) Governing networks: EGPA yearbook, (pp. 299–318). Amsterdam: IOS Press.

Bouckaert, G. and van de Walle, S. (2003b) Comparing measures of citizen trust and user satisfaction as indicators of ‘good governance’: Difficulties in linking trust and satisfaction indicators. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 69 (3), 329–343. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852303693003

Cheema, G.S. and Popovski, V. (eds) (2010) Building trust in government: Innovations in governance reform in Asia. New York: United Nations University.

Evans, J.R. (2012) Quality and performance excellence: Management, organization and strategy. New Delhi: Cengage Learning India Pvt. Ltd.

Fukuyama, F. (1995) Trust: The social virtues and the creation of prosperity. New York: Free Press.

Habib, B.W. (2009) All about upazila parishad. The Daily Star. Available at: https://www.thedailystar.net/news-detail-72392

Jamil, I. and Askvik, S. (2013) Citizens’ trust in public officials: Bangladesh and Nepal compared. In: Jamil, I., Askvik, S. and Dhakal, T.N. (eds) In search of better governance in South Asia and Beyond, (pp. 144–163). New York: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-7372-5_9

Jamil, I. and Askvik, S. (2015) Citizens’ trust in public and political institutions in Bangladesh and Nepal. In: Jamil, I., Aminuzzaman, S.M. and Haque, T.M. (eds) Governance in South, Southeast, and East Asia (pp. 157–173). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-15218-9_10

Jamil, I. and Askvik, S. (2016) Introduction to the special issue. International Journal of Public Administration, 39 (9), 647–651. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2016.1177835

Khan, M.M. (1997) Urban local governance in Bangladesh: An overview. In: Islam, N. and Khan, M.M. (eds) Urban governance in Bangladesh and Pakistan, (pp. 7-26). Dhaka: Centre for Urban Studies.

Khan, N.A. (2016) Challenges and trends in decentralised local governance in Bangladesh (No. 222-22). ISAS Working Paper. Singapore: National University of Singapore.

Khan, N.A. (2018) A political economy of forest resource use: Case studies of social forestry in Bangladesh. Routledge Revivals Series. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429464522

Kim, S.-E. (2005) The role of trust in the modern administrative state: An integrative model. Administration & Society, 37 (5), 611–635. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399705278596

Lame, E. and Papa, A. (2016) Opinion poll: Trust in government 2015. Tirana: Institute for Democracy and Mediation.

Liu, H. (2015) Why is local government less trusted than central government in China? Doctoral dissertation, University of Birmingham.

Makorere, R. (2012) Towards understanding citizens trust in local government authorities in social service provision: A case of education service in Maswa district Tanzania. International Journal of Development and Sustainability, 1 (2), 225–239.

Mark, K., and Nayyar-Stone, R. (2002) Assessing the benefits of performance management in Eastern Europe: Experience in Hungary, Albania, and Georgia. Paper presented at NISPAcee Annual Conference, Cracow, Poland.

Mzee, P. K. (2012) The context of globalization and human resource need and strategy for developing countries – the case of African countries. In: Cuadra-Montiel, H. (ed) Globalization: Education and management agendas. IntechOpen, DOI: 10.5772/45615. Available at: https://www.intechopen.com/books/globalization-education-and-management-agendas/the-context-of-globalization-and-human-resource-need-and-strategy-for-developing-countries-the-case-

Panday, P.K. (2011) Local government system in Bangladesh: How far is it decentralised? Lex Localis - Journal of Local Self-Government, 9 (3), 205–230. https://doi.org/10.4335/9.3.205-230(2011)

Parker, S., Spires, P., Farook, F. and Mean, M. (2008) State of trust: How to build better relationships between councils and the public. London: Demos.

Rahman, M.S. (2012) Upazila parishad in Bangladesh: Roles and functions of elected representatives and bureaucrats. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, (11), 100–117. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.v0i0.3060

Yang, K. and Holzer, M. (2006) The performance–trust link: Implications for performance measurement. Public Administration Review, 66 (1), 114–126. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00560.x

Yasmin, R., Hasnayen, M.E. and Sultana, M.S. (2017) Strengthening the local government and effective role of upazila parishad in Bangladesh. Journal of Public Administration and Social Welfare Research, 2 (2), 10–29.