Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance

Issue 24

June 2021

RESEARCH AND EVALUATION (PEER REVIEWED)

Localising Democracy on an Uneven Playing Field: The Roles of Ward Councillors in the City of Cape Town

Vinothan Naidoo

Department of Political Studies, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch 7701, South Africa, vinothan.naidoo@uct.ac.za

Corresponding author: Vinothan Naidoo, Department of Political Studies, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch, 7701, South Africa, vinothan.naidoo@uct.ac.za

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi24.7065

Article History: Received 14/02/20; Accepted 20/01/21; Published 28/06/21

Citation: Naidoo, V. 2021. Localising Democracy on an Uneven Playing Field: The Roles of Ward Councillors in the City of Cape Town. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, 24, 40–59. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.vi24.7065

© 2021 by the author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Abstract

The democratic transition in South Africa was accompanied by large-scale institutional re-engineering at all levels of government. This was an extremely complex process in local government, where a racially fragmented system of municipalities underwent extensive reorganisation. Despite this, historical patterns of settlement based on race have entrenched socio-economic inequalities and highly uneven experiences of local democracy. Against this backdrop, this paper investigates the differing roles of ward councillors. It examines a stratified sample of low-, mixed- and high-income wards in the City of Cape Town, and finds general yet qualified support for a view that ward councillor roles are conditioned by the socio-economic character of the areas they represent. In broad terms, councillors in low-income wards play a service broker and conflict mitigator role; councillors in mixed-income wards act as reconcilers and integrators; and councillors in high-income wards perform a placeholder and maintainer role.

Keywords

South Africa; Ward Councillors; Cape Town; Local Democracy

Introduction

South Africa’s transition to democracy in the early 1990s ushered in an era of tremendous hope for racial reconciliation in state and society. A lengthy period of transitional arrangements led to sweeping changes to the structures and boundaries of local government councils, culminating in the first democratic elections of 2000. The centrepiece of a democratic municipal framework was the concept of a ‘developmental local government’, which tasks local councils with several roles: to prioritise services to their most vulnerable and marginalised citizens; to promote more participatory interaction with citizens; and to incorporate local forms of economic empowerment (Ministry for Provincial Affairs and Constitutional Development 1998).

Against this policy backdrop, the literature on ward councillors in South African municipalities portrays a largely disempowered group of actors caught between a centralised municipal executive and administration, and an increasingly assertive citizenry that may choose either to ignore, bypass or co-opt councillors, or to channel their frustrations through them in a bid to secure longed-for public services. This paper suggests that the roles played by ward councillors vary according to their ward income profile, the dynamics amongst and between their constituents and themselves, and the degree of influence they can exert over their senior political and administrative counterparts in councils. This characterisation implies that the generic description of councillor roles and responsibilities found in official policy and legislation can be no more than a rough guide to their actual conduct (SALGA GTZ 2006). Instead, de facto councillor roles might conform more closely to a set of heuristic categories outlined in Table 1, drawn from the author’s general impressions of how councillors have been depicted across South Africa’s diverse municipal landscape.

In high-income wards, councillors are considered most likely to play a ‘placeholder and maintenance role’, representing constituents who, by and large, have the capacity to self-organise and troubleshoot problems with municipal authorities. In this scenario, councillors serve either as conduits/intermediaries or advocates for relatively well-organised residents who seek to preserve and maintain their existing amenity and service levels. The composition of mixed-income wards is more complex, and councillors will confront the challenge of integrating and reconciling the needs and concerns of starkly differing socio-economic groups with widely different needs. At their best, they can foster improved understanding, reduced resentment and a peaceful co-existence between those groups, but at worst they may sustain those very resentments if they are perceived to advance sectional interests. In low-income wards, councillors will inevitably be thrust into the role of service broker and conflict mitigator, as these areas are characterised by more widespread discontent fuelled by high levels of service backlogs and heightened demand pressures. In some instances, councillors may even become the target of a community’s frustration.1 This article presents the findings of a research study carried out in 2019 that tested the validity of the heuristic model described above by investigating the differing roles that ward councillors play across a stratified sample of six wards in the City of Cape Town.

Political and research context: South African local government and the ward councillor

South Africa’s system of local government has undergone dramatic structural changes since the country’s democratisation in 1994. A myriad of racially divided local government structures were reorganised into 284 new, multi-racial municipalities, followed by country-wide democratic elections in December 2000, which have subsequently taken place on a five-year cycle. These new municipalities are classified as ‘metropolitan’ (category A), ‘local’ (category B), and ‘district’ (category C).

South Africa’s 1996 democratic constitution elevated the status of local governments by investing them with distinct powers and functions, which contrasted with their historically subordinate relationship to provincial and national authorities (Cameron 2001). The new municipalities, especially those in densely populated urban areas, have assumed responsibility for the direct delivery of a wide array of services such as water and sanitation, electrification, local health, public works and transport, and housing. However, apartheid-era spatial planning and labour regulations perpetuated a vicious cycle of entrenched income disparities which, in turn, exacerbated racially skewed access to public services at the local level, and spawned deep distrust between and amongst residents and municipalities. The scars of the past continue to be visible in South Africa’s metropolitan municipalities, which as a group exhibit levels of urban inequality2 well above cities elsewhere in Africa (South African Cities Network (SACN) 2016).

The present study focuses on the City of Cape Town metropolitan municipality (the ‘CoCT’). The socio-economic profile of the Cape metropole is complex and represents something of an enigma: it displays a lower level3 of income inequality than its counterpart metropolitan areas in South Africa, as well as relatively higher and more universal access to basic services. Yet, it also displays a high percentage of poor households and marked differences between the city’s Black, Coloured and White populations.4

In this context, ward councillors serve a crucial role in delivering the ‘developmental’ vision of post-apartheid local government. They are tasked with rebuilding trust with citizens at a neighbourhood level, and fostering a more bottom-up approach to municipal reconstruction and development. Ward councillors are directly elected members of a municipal council who represent geographically demarcated wards, and are therefore directly accountable to residents. They serve along with proportional representation councillors, who are drawn from political party candidate lists and are allocated seats based on a party’s share of the total vote.

Metropolitan local government administrations in South Africa have evolved complex governance frameworks in which decision-making power has become highly concentrated. This has often sat uncomfortably with the promotion of decentralised ward-based political representation (ie ward councillors). Decision-making power has gravitated towards a centralised political–administrative structure, with a municipal council’s political executive (mayor and executive committee) and its administrative leadership sharing statutory responsibility over functions such as development planning and the provision and oversight of municipal services (Thornhill 2008). De Visser (2009) notes that as a result non-executive (eg ward) councillors “… feel increasingly disadvantaged due to the lack of access to documentation and information flows” (De Visser 2009, p. 16). Paradza et al. (2010) similarly found that with the exception of one case, ward councillors had poor access to information on the progress of service programmes, and no decision-making influence on development projects in their wards. Interestingly, in the international context similar findings were reported in Askim and Hanssen’s (2008) study of citizen input into the setting of local policy agendas by municipal councillors in Norway.

Heller (2009, p. 134) discusses a scenario in which these trends have produced democratic deficits. He describes a local state, particularly at the metropolitan level, characterised by bureaucratised and corporatist methods of service delivery and managerially driven processes of accountability, which have narrowed the scope for meaningful citizen engagement, participation and influence. Copus et al. (2013) paint a similar picture in England’s local government system, describing a withering-away of councillors’ roles as local democratic representatives and political interest aggregators, which has seen councillors superseded and sidelined by a centralised and technocratic discourse that views local governments primarily as mechanisms for better managed public service delivery.

Millstein (2010) highlights the forces acting on ward councillors in the Cape metropole. She suggests that the demarcation of ward areas in the country’s new urban governance landscape has had to strike a delicate balance between councillors as political representatives and councillors as citizen engagers and community advocates. Councillors struggle with their roles in part because increasingly centralised and hierarchical processes of executive decision-making tend to homogenise the diverse and conflicting interests of citizens into ‘communities’, as a kind of managerial device. They become “caught up in the tension between obligations ‘from above’ and commitments to community” (Millstein 2010, pp. 8, 12–13). A similar tension is evident in Tan et al.’s (2016) study of how Australian local government councillors define their roles, which they find to be in wide and varying terms ranging from shaping and overseeing the strategic and financial governance of their council to ensuring that their constituents benefit from the council’s strategic policy planning agenda; and – importantly – continuing to serve as a channel for direct community liaison and as a citizen advocate and problem solver.

Working alongside councillors are statutory ward committees established under South Africa’s Municipal Structures Act (1998). These are meant to facilitate community engagement on policy and service priorities between the ward councillor, who chairs the committee, and representatives from local interest groups. Yet research on ward committees has revealed the limited impact these entities appear to have in taking forward local concerns to the central municipal executive. Smith and De Visser’s (2009, p. 5) research on six ward committees across three municipalities, including one metro, observed the minimal influence these structures had on council decision-making, which was partly attributed to the absence of ‘structured mechanisms’ of input into council deliberation. They added that councillors appeared to lack the authority to raise ward-level issues in council proceedings. Buccus et al.’s (2008, p. 307) study of public participation in a sample of district municipalities in KwaZulu-Natal described members of the public as feeling ‘powerless’ that their appeals to councillors would be channelled into municipal priorities. Moreover, Barichievy et al. (2005, p. 388) discounted the influence of ward committees, describing their status as mere “advisory committees to ward councillors”, rather than a forum for the expression of the independent voices of local interests.

A study of ward committees in the Bonteheuwel area of Cape Town by Esau (2007, pp. 19, 23) observed that some local issues of concern did appear more tractable for ward committees, such as visible policing and upgrading of sports fields. This was contrasted with deep-seated problems such as poverty and unemployment, which had a demoralising effect on levels of participation, exposing a gap between what councillors can achieve and the socio-economic conditions of their wards. Piper and Deacon’s (2009, p. 424) study of the Msunduzi municipality in KwaZulu-Natal made similar observations, explaining that issues in wealthier wards concentrated on narrower and more localised problems such as crime, lighting and traffic calming, whilst poorer wards contended with “broader issues of development, housing, sanitation and service delivery”.

A similar picture emerges from a study by Vivier and Wentzel (2013) of four suburbs5 in the CoCT with diverse demographic and living standards profiles. It found that in wealthier areas most residents were generally uninterested in engaging with local councillors so long as service levels were perceived as satisfactory. This suggested a widespread “contentment with the lack of engagement” (Vivier and Wentzel 2013, p. 245). In an extreme variant of this, ward councillors in affluent wards might be bypassed entirely by economically empowered ratepayers’ associations which elected which elected to communicate their demands directly to city authorities or resolve disputes via litigation (Bénit-Gbaffou 2008, pp. 7–8).

By contrast, in more impoverished suburbs, residents’ reluctance to interact and engage with local councillors was driven by deep-seated distrust and a lack of confidence in councillors’ genuine interest and commitment to improving their service standards and identifying with the needs of local people (Vivier and Wentzel 2013, p. 246). This revealed the disempowerment experienced by these residents, and the need for councillors to re-establish and repair strained relations with their constituents, and to “show interest in the community’s needs not only through responsiveness to problems, but also in a pro-active manner”. Failing to do so could be perceived as a sign of disrespect and lack of care (Vivier and Wentzel 2013, p. 248).

Methodology

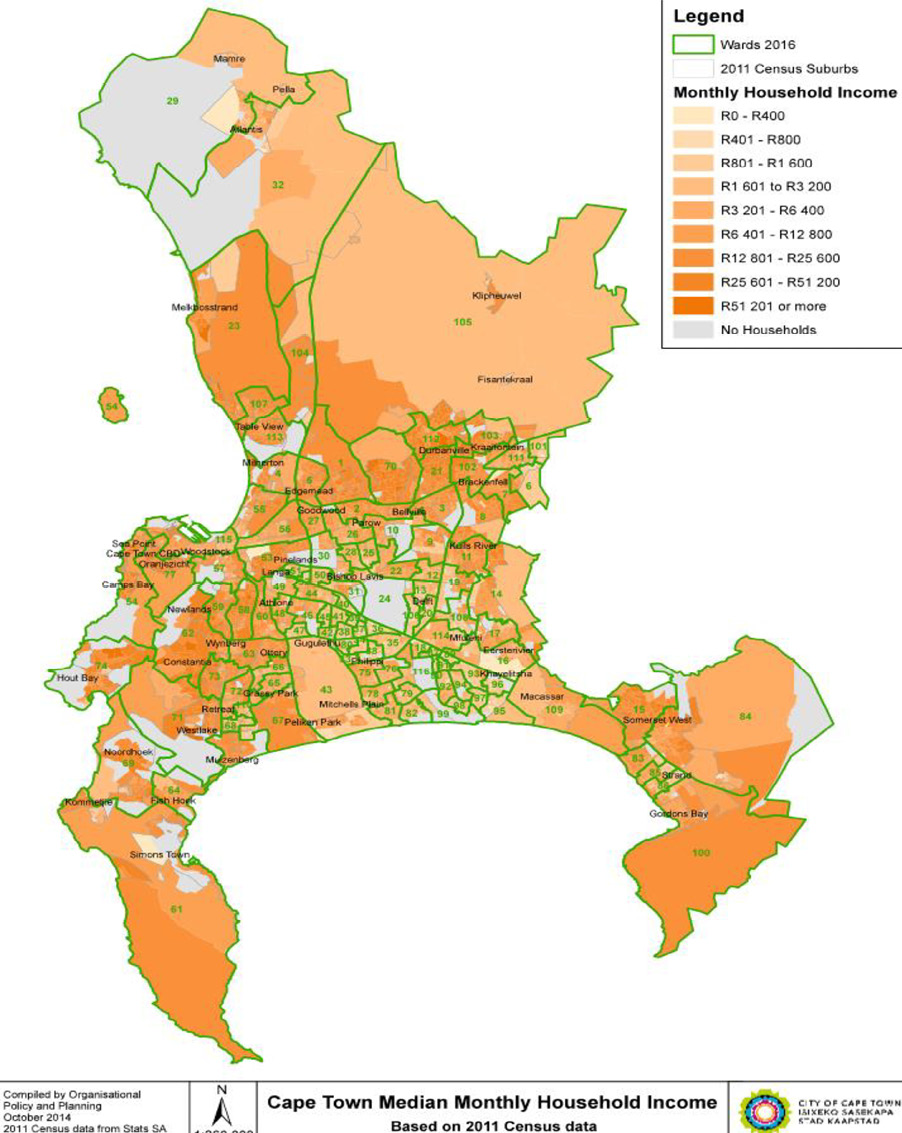

Data from a total of six wards is presented in this study. Two wards from each of three income groups (low, mixed, high) were sampled according to ward-level income profiles supplied by the CoCT’s Development Information and GIS department, based on the 2011 national census. Figure 1 illustrates the diverse patchwork of wards by median income profile in the CoCT. Convenience sampling was employed to ensure a geographically diverse sample of wards and to maximise data on ward-level activities from available community media sources. The sampled wards, which are usually designated with a number by the CoCT, were all anonymised by allocating a letter to each: ‘A’ – ‘F’. This was done in order to maintain a focus on how a ward’s socio-economic profile shapes the role performed by its councillor.

Figure 1. Median income by ward

The main source of data used to construct a profile of councillor roles in each ward was articles from community newspapers. These articles provided contextually-rich descriptions of how councillors were perceived by and interacted with their constituents; the issues they dealt with on a weekly basis; and how they interacted with their political and administrative counterparts in the city council. Articles were sourced from a stable of weekly community newspapers with a long history of covering local affairs across the six sampled wards. These included the following titles: Tabletalk, Athlone News, Northern News, Plainsman, and the Southern Suburbs Tatler.

A physical and electronic (via online editions) search of articles in each community newspaper title corresponding to a sampled ward was carried out for stories that explicitly mentioned ward councillors between 2015 and 2019. Articles were tabulated and coded according to topical theme (referred to hereafter as the ‘issue area’), and annotated with a description (including with meaningful quotes) of how councillor roles were characterised. This process yielded a total of 118 articles across all sampled wards. The results of this analysis are presented in Table 2.

The quoted extracts presented in the findings section of this article have all been sourced from a community newspaper article corresponding to a sampled ward. Interviews were also sought with the six councillors representing each sampled ward, to supplement and contextualise the data extracted from media articles. The interview schedule included questions about how councillors engaged with and managed the demands of their constituents, and their influence over ward-level activities in relation to their political and administrative counterparts in the city administration. Four of the six councillors agreed to be interviewed in person, with a fifth councillor submitting written responses to a questionnaire. Extracts presented from interviews with ward councillors have also been anonymised, and are attributable only to the sampled wards they represent.

Findings

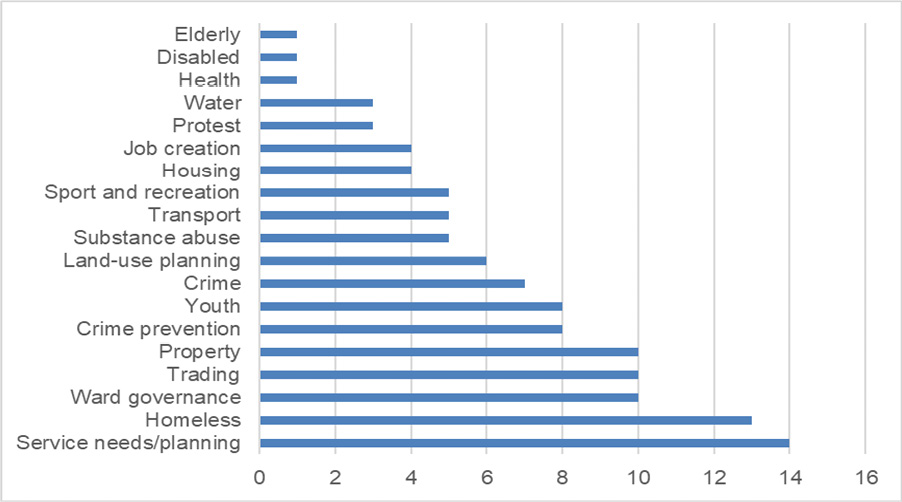

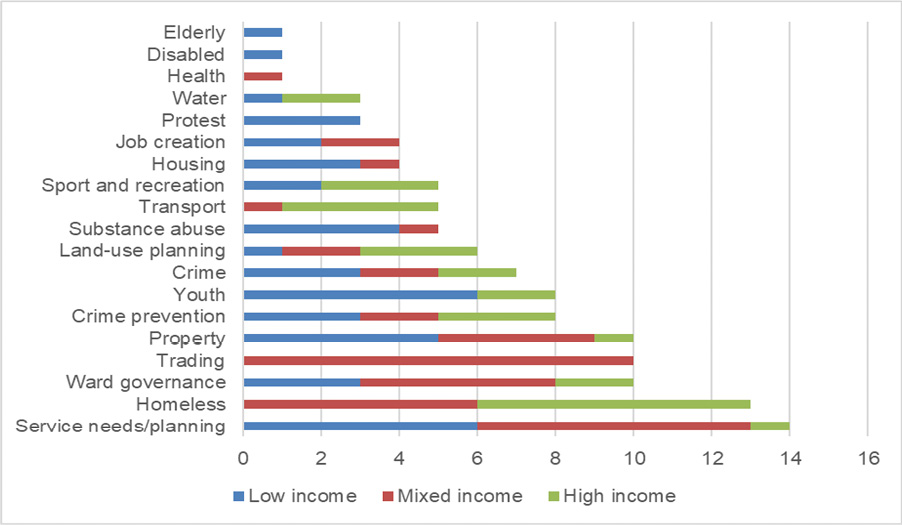

Figures 2 and 3 along with Table 2 show the results of the review of media reports. Issue areas provide a window into the de facto roles that councillors play; and also into how they engage with their political and administrative counterparts, as well as their constituents. The coding of issue areas produced 19 categories across a total of 118 articles.

Figure 2. Frequency of issue areas in wards in community media coverage

| Issue area | Ward C | Ward D | Ward A | Ward B | Ward E | Ward F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low income | Low income | Mixed income | Mixed income | High income | High income | |

| Ward governance | 2 | 1 | 5 | - | 1 | 1 |

| Service needs/planning | 3 | 3 | 5 | 2 | - | 1 |

| Trading | - | - | 5 | 5 | - | - |

| Land-use planning | - | 1 | 2 | - | 1 | 2 |

| Crime | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | - |

| Property | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | - | 1 |

| Crime prevention | - | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Substance abuse | 2 | 2 | 1 | - | - | - |

| Housing | 2 | 1 | - | 1 | - | - |

| Homeless | - | - | - | 6 | 4 | 3 |

| Health | - | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Job creation | 2 | - | - | 2 | - | - |

| Transport | - | - | - | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Protest | 3 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Youth | 4 | 2 | - | - | - | 2 |

| Disabled | 1 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Water | - | 1 | - | - | 2 | - |

| Sport and recreation | - | 2 | - | - | - | 3 |

| Elderly | - | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| TOTAL | 23 | 21 | 22 | 22 | 15 | 15 |

Issue areas included traditional local government functions such as land-use and municipal service planning, ward governance, trading, housing, transport, and sport and recreation, along with issues spanning wider inter-governmental and non-governmental spheres. The latter included crime and crime prevention, substance abuse, street homelessness, and the needs of specific groups such as youth and disabled persons.

The most frequently appearing issue concerned ‘service needs/planning’ (14 articles), which dealt with citizen concerns about the planning, prioritisation and implementation of municipal projects, services and budgets in ward areas. This is unsurprising given declining levels of public satisfaction in local government’s ability to manage the delivery of services (The Presidency 2016). There were also ten articles each about ward governance, trading, and property-related matters. Thirteen articles covered street homelessness, which is an issue that transcends the traditional tasks of local government but acutely affects municipalities. Similarly, criminal activity (‘crime’), crime prevention, youth (primarily empowerment and safety) and substance abuse also featured prominently. The remaining articles mostly concerned other municipal functions, with land-use planning being the most frequent.

A clearer image of how issue frequency shapes councillor roles emerges in Figure 3, which displays issues according to the income profile of the six wards.

Figure 3. Frequency of issue areas by ward income in community media coverage

Service needs and planning

The most frequently occurring issue, ‘service needs/planning’, was almost exclusively confined to low- and mixed-income wards, and in almost equal number. Examples included a planned infrastructure upgrade to ward C’s central business district, which the councillor claimed he had ‘resurrected’; and a similar commitment by both the mayor and the councillor to regenerate the town centre of ward D through planned infrastructure, cleaning and public safety spending. Despite the possible widespread benefits generated from these schemes, it was clear that councillors were limited in their ability to unlock and expedite resources for projects of this scale, and as a result the projects ran the risk of failing to satisfy raised expectations. In ward C, despite the holding of public information meetings presided over by the councillor, some residents criticised the city for not including the proposed central business district upgrade in its wider budget. In ward D, another article recounted the ward councillor’s dismay that funding for the planned refurbishment of the town centre was being hampered by bureaucratic delays:

The town centre is a mayoral programme. If there is no funding that means the department did not do proper planning as every year the fight is about funding for law enforcement officers.

Nevertheless, it was also evident that councillors believed they could exert influence over city bosses by highlighting the need for major infrastructural investment in their areas:

The biggest success in my time as ward councillor is that [name of area] Town Centre is the first township in Cape Town to be declared a Special Rated Area (Interview, councillor, ward D, low income).

I don’t think ward councillors realise the level of influence they actually have. They may not have decision-making ability, but they have the ability to influence decisions to benefit their communities … I think it’s fact-based … I think decision-makers generally appreciate the fact that people who do the graft, the hard work, the collection of the facts, because evidently when they are making the decision it’s based on facts as well … (Interview, councillor, ward C, low income).

Alongside general unhappiness with the planning and roll-out of large-scale service improvements in low-income wards, it was also evident that some issues, such as housing, sparked acute contestation between low-income residents. In some instances, this exposed councillors to considerable risk. In ward C, at a public meeting to discuss the city’s proposed budget, one resident queried why a significantly smaller amount of money was being allocated to erect houses compared to electrifying backyard dwellings, or informal (rental) structures erected within the backyard area of formal homes. It was clear in other media articles that the concern for many residents in this ward was not a lack of priority for the construction of houses, but the terms on which proposed housing projects were planned. This was revealed in an article reporting on a public meeting convened by the ward councillor, at which he was “verbally and physically attacked”. At the meeting, a group of residents denied that they objected to the roll-out of housing, but complained that the councillor along with his predecessor had failed to adequately consult residents on the site planning for housing schemes to ensure that overcrowding could be managed, space for recreational use be preserved, and preference given to local residents. In response, the councillor, along with other residents, argued that the protestors represented people who already had homes and that they were seeking to deny the same to others (backyard rental dwellers): “This is a very exciting project which will see almost 400 families be able to swop the street or backyard dwelling for a home.” In ward D, access to proposed housing developments also revealed latent tension amongst residents, with the mayor explaining to residents at a public meeting that “with regard to housing, there is a waiting list and no councillor has an influence on allocation of houses”.

Surprisingly, service needs/planning was the subject of slightly more articles in mixed-income wards. A common thread linking the two wards in this category was the gulf between residents in lower- versus higher-income areas, and the role councillors played to mediate that tension.

One article about ward A described how residents of a lower-income suburb complained of being inconvenienced by road repairs caused by a municipal project to upgrade sewerage infrastructure. One resident was quoted as saying that the real purpose of the project was “keeping water clean for the rich people of [a neighbouring suburb]” and not, as the councillor said, for the “good of the community” by increasing the area’s sewerage capacity in response to population growth. This councillor’s vulnerability to criticism by sections of the community was clearly evident in other articles about service needs/planning in the ward, with one recounting how residents of another low-income suburb complained about overcrowding and service neglect by the city and the councillor. In defence, the councillor claimed that his ward budget was “spread evenly” and included projects in their area, although he also conceded that resources in some instances were effectively being rationed between this community and a neighbouring low-income suburb to “optimise usage of city assets”.

In an interview, this councillor acknowledged the challenge he faced in reconciling the starkly differing needs of his constituents:

I was sometimes being put in the middle, where the guys on the other side of the … road would say to me, you are taking care too much of [informal settlement area], and the [informal settlement] guys will say you are spending more money over the … road [laugh]. Now, you had to reconcile the two ….

Despite this divide, another article about ward A showed that some residents of higher-income areas of the ward recognised that their destiny was intimately tied to improvements in the quality of services enjoyed by their lower-income neighbours. The chairperson of a residents’ association representing a mainly higher-income suburb resigned as a ward committee member and criticised the city for not prioritising the needs of neighbouring lower-income and informal settlement areas, explaining that:

What happens across the road affects us directly. Until there is peace and stability, clean streets, sanitation and security along with a sense of hope for our neighbours, we will not be able to enjoy our own community.

In ward B, public criticism of service needs/planning also exposed the income divide, with the ward councillor saying in an interview that:

A lot of the constituents don’t see how big the ward is, for them it is that you just need to concentrate on their section, so the [higher-income area] people feel that I spend too much time in [lower-income area], but then [lower-income area] kids are being killed by their parents …. So, where would my time be? It would be with that family.

Despite this, the councillor admitted that constituents in more affluent areas were becoming increasingly aware of the particular needs and challenges of their lower-income counterparts.

Trading and job creation

The issue of ‘trading’ also revealed the difficulty experienced by councillors in negotiating conflicting interests in mixed-income wards. Most articles concerned the difficulties faced by councillors in trying to reconcile and accommodate informal trading to enable income generation, whilst mitigating the wider risks and concerns that neighbouring residents and businesses perceived it to pose, such as crime, drugs, and spatial decay:

We need to address this issue; that is not a great street. This is a serious issue and we need to also look at the anti-social behaviour occurring in and around [reference to specific area]. (Councillor, ward B, cited as being ‘unhappy’ with the lack of monies available to lease a plot of land from a state-owned entity to accommodate an informal trading market.)

We should understand that this is a delicate matter, and the plan is not easy to implement. On the other side, though, I would love to help out because I know that this is how people make their living. (Councillor, ward A, in an article about informal traders being subjected to raids by city law enforcement officials, with traders criticising the city for failing to issue them with trading permits.)

The issue of ‘job creation’ was spread between mixed- and low-income wards, and reflected the sometimes fraught situation faced by councillors in facilitating and overseeing city-managed employment creation schemes. Articles included a councillor being accused of interfering in the allocation of job opportunities via a city-managed jobseekers’ database, in low-income ward C; and another of a councillor reporting complaints about the ill-disciplined conduct of temporary cleaning workers employed on a city-managed job creation programme, in mixed-income ward B. In the former case, it revealed heightened contestation for employment, which exposed councillors to risks associated with becoming directly involved in city-managed initiatives; and in the latter case, the situation clearly left the councillor torn: “We want people to grow and have an income, but we can’t have people in City of Cape Town uniforms behaving like this.”

Homelessness

The topic of ‘homelessness’ was confined to mixed- and high-income wards. It highlighted a familiar ‘not in my backyard’ image of the street homeless as a constituency at the periphery of even the low-income stratum, whose presence in mixed- and high-income areas needed to be policed.6 In these circumstances, councillors appeared to act as advocates and/or intermediaries supporting the efforts of residents’ associations to control the movement of homeless persons in their areas.7 The following quotes capture the approach of councillors in high-income wards:

Everyone must work together to save our area from deteriorating (Councillor, ward E).

Currently a request is for social development … to engage with them [the homeless] and offer appropriate assistance where possible. Law enforcement also steps in, responding to any complaints received … (Councillor, ward F, responding to concerns raised by ward committee members about the homeless sleeping in area parks and begging for food.)

All complaints are logged with the solid waste department to clean up the area … I can vouch that whenever we logged the request for cleaning, solid waste has responded. (Councillor, ward F, responding to concerns raised by residents’ groups and local businesses about the negative environmental impact of homeless persons in the area.)

In contrast to high-income wards, only one of the two mixed-income wards experienced sustained problems with the homeless (ward B). Residents’ associations representing higher-income constituents were the primary drivers behind complaints, and their frustrations with the homeless and with councillors were particularly acute, resulting in councillors struggling to satisfactorily resolve the issue:

When we go to ratepayers’ meetings, they [residents] come down hard on me … about street people in [area within ward] (Councillor, ward B).

The income-specific nature of the homeless problem in ward B was also evident in an interview with the ward councillor, who explained that:

If I look at the [name of suburb] area, the affluent side of the ward, the issues that we have on this side would be also crime that has escalated, because of vagrants that have moved into the area, and the criminal element has infiltrated the vagrants.8

Crime and crime prevention

Crime-related issues straddled all three ward categories, but varied in frequency and revealed how issues of common concern could manifest and affect councillors differently. Rebuilding dented trust and confidence between residents and law enforcement authorities was clearly needed in low- and middle- income wards, with councillors actively but not always satisfactorily troubleshooting criticisms and facilitating solutions. The severity and complexity of crime (including gangsterism, substance abuse and murder) and its related effects on councillor activities in lower-income areas was palpable. In ward D, the councillor explained in an interview how crime disrupted communication with his constituents:

… due to crime [holding] public meetings at night is challenging as the public do not want to attend the meetings … meetings on a Saturday have been the best option to get the community out to discuss challenges and service delivery matters.

In mixed-income ward B, when referring to the most impoverished area within the ward, the councillor similarly remarked on the secondary effects of crime, in an interview:

Now if I start at [name of area], that is the section of the ward that has the most challenges … crime is, it’s a red zone, services that are hampered … because a lot of the officials that go in get robbed, or they get shot at …

In contrast, in high-income wards, residents’ associations appeared to be driving efforts to combat mostly petty and property-related crime, and councillors were being called upon to facilitate and escalate crime-fighting efforts by law enforcement authorities. However, there were instances of some residents remaining passive bystanders of crime prevention initiatives, which sometimes raised the ire of councillors, as evident in one article:

We … are one of the wealthiest areas with an average income of R461,000 per annum, but our biggest challenge is that people don’t want to become involved with community activities … (Councillor, ward E, in relation to the unveiling of a community safety plan).

Ward governance

Articles on ward governance were heavily skewed by complaints directed at ward councillors representing ward A (mixed income). A previous councillor representing the ward was widely criticised by residents and local party officials for being unresponsive, which ultimately resulted in his removal. Other articles reported on criticisms directed at his successor by the ratepayers’ association of a lower-income area in the ward. This reinforced the complex cross-sectional demands made on councillors representing mixed-income wards, both between different low-income suburbs and between low-income and higher-income areas, as outlined earlier in articles about service needs/planning:

I and most of the people here tonight feel that the councillor is focused a lot on other areas besides [name of area], and we hardly see him here (Ward A, chair of a ratepayers’ association).

The councillor stated that he was involved in many projects in the area, and had proposed organising another meeting to discuss the residents’ concerns because he felt the meeting called by the ratepayers’ association was intended to attack him. In an interview, he explained that he had set up fora in various low-income suburbs of the ward:

I go to [name of area], for example … there’s a forum there that I set up, in [name of area] there’s a forum that I set up, in [name of area] there’s a forum that I set up … so they talk to me …

More broadly, interviews revealed the striking trust deficit in low-income wards and lower-income areas of mixed-income wards, which differed markedly from high-income wards in the way councillors engaged with community members, and their strenuous efforts to overcome this deficit and rebuild trust:

Just yesterday I popped into the office … I didn’t even get to the event, because there were so many people that just want to talk to you … I deal with people’s personal issues … wife/husband issues … because people trust you that way … you may not be able to solve their problem, but you are willing to listen to them … (Interview, councillor, ward C, low income).

In an interview with the councillor from ward B, a mixed-income area, several references were made to the councillor’s personal engagement with residents from the most impoverished section of the ward, which again signalled the importance of building trust:

When I came in as a councillor, a lot of them [referring to residents in a lower-income area] said that I don’t know their plight, and I don’t know what they’re going through, it’s because of what I wear now and what I drive, and where I live … The [name of lower-income] community will visit this office on a daily basis, it looks like a day hospital. And then you have your constituent who wants a meeting with you as well … that comes to the office that don’t just want to lodge their complaint but they want to see you as a councillor and you need to make time for that as well (Interview, councillor, ward B, mixed income).

In contrast, in high-income ward E, the councillor was primarily engaged in mobilising the initiative of empowered but largely passive constituents, rather than repairing dented trust:

When I started as a councillor there were no organisations in this area … there was only the one, the ratepayers … people are working, more than 85% of people have jobs, they are high-profile jobs … the people who don’t work now, it’s all retired people … in the beginning … people, they never complained, they thought that the municipality is still in [name of previous local council office], they thought they must know … so we took a long time … because people…don’t fight for what they want because in the olden days we were privileged, we just got what we wanted (Interview, councillor, ward E, high income).

Property and land-use planning

The wide variation in concerns raised in articles about ‘property and land-use planning’ across all three ward types showed how differently residents across income streams experienced and sought to regulate the use of space, and how this affected the actions taken by councillors. Articles about property ranged from the municipal regulation of problem buildings to maintenance of council rental stock, and damage to municipal and private property. This issue was most prevalent in low- and mixed-income wards, with only one article on high-income wards.9 A common property-related issue that was particularly acute in low-income wards, and also experienced in informal areas of mixed-income wards, was house fires that caused structural damage and loss of life. Councillors were often seen facilitating financial appeals to assist affected families and arranging relief services from the city. In these cases, the structures at risk of fire were often of modest or make-shift quality. Other articles highlighted residents’ concerns about the direct risks posed by problem buildings and council neglect in maintaining rental stock, which elicited frustration from both residents and councillors.

Articles on land-use planning revealed a very different cross-ward distributional pattern compared to property, with high-income wards accounting for the largest share. These typically covered residents’ concerns about the impact of planned developments on the quality and integrity of existing suburban and adjacent spaces, eg traffic congestion and ecological protection. Interestingly, a land-use planning article in mixed-income ward A exhibited similar features to those in high-income wards, in which residents objected to planning approval being granted to a housing development in a higher-income suburb of the ward. In all these cases, councillors appeared either reticent to give active support to residents’ objections, or frustrated by processes they felt powerless to control:

The developers will then have to apply for rezoning, a process that could take between 18 months to two years … the proposal has not even gone through any official city channels … it’s still very early days. Obviously the city would ensure that the ecology of the area would be looked after were the development to go ahead. (Councillor, ward F, high income, appearing to assuage the concerns and surprise expressed by some residents about the limited information available about a proposed development.)

I think the city needs to relook at the processes in which they approve these developments. More information should also be passed on to the councillors as well because we are the ones who have to face the community when these plans are approved. (Councillor, ward A, mixed income, seemingly dismayed at being placed in a situation of having to respond to objections by residents concerning an approved housing development in a suburban area.)

Youth, sport and recreation

Articles about ‘youth’ and ‘sport and recreation’ also straddled both high- and low-income wards and revealed how similar issues manifested differently across ward types, and shaped councillor roles in the process. In high-income suburbs (ward F), councillors encouraged or sponsored charitable initiatives to assist school-going youth in areas as diverse as artistic expression and sponsorship of sanitary pads for girls at a local school. In articles about youth in low-income areas (wards C and D), a more complex web of risks and challenges confronted youth, such as drug abuse,10 crime, building self-esteem, and gaining further education and employment. Councillors often facilitated the awareness and support efforts of civil society and government organisations, and viewed youth empowerment as a means of combating other social ills.

As with youth, issues concerning sport and recreation showed councillors playing starkly different roles. In high-income ward F, the councillor provided financial support via their ward allocations and in conjunction with fundraising by residents’ associations to refurbish and maintain suburban parks. The councillor also troubleshot residents’ concerns about drones causing a nuisance in local parks with city authorities. Similarly, in ward E the councillor was able to leverage the fundraising capacity of residents to unlock city funding for the upgrading and maintenance of leisure spaces:

So I told the people that, if we show the city that we are really desperate, that we must fence this thing in, and we start this, we will get the money, so we did this … so I applied for the money, and it was approved, and we got the R2.5 million for the fence … after the residents put in money to start the first [phase] (Interview, councillor, ward E, high income).

In contrast, in low-income ward D, the councillor was confronted with the abject scarcity of facilities and funding for sport and recreation, and concerns about safety, as explained in these articles:

I take exception to this – when the city wants to develop certain areas like the CTICC … they can find R557 million, but they can’t find a cent for the development of our athletics track … (Councillor for a ward adjoining ward D, lobbying for the combined area).

We were not informed about the park layout and structure. We would gladly have informed the city about the dynamics of the area … Eventually, they put equipment in the park, but the structure doesn’t make sense and most importantly it is unsafe. (A community worker in ward D criticising the layout of a children’s play park in the middle of a gang-infested area.)

Conclusion

The findings of this study confirm that a councillor’s agency and role are meaningfully affected by the socio-economic profile of their ward. This, in turn, shapes the dynamics between councillors and their constituents, and can influence the pace at which the larger bureaucratic machinery on which they depend moves. However, councillors are not captives of their circumstances. They were observed in many instances as proactive leaders working both with and within their socio-economic and institutional constraints, and in other cases as resourceful actors exploiting opportunities to unlock major public service investments in their areas.

Councillors in low-income wards were consistently thrust into the role of brokering service delivery, and also of mediating the consequences of their constituents’ frustrations over the pace of provision and availability of municipal services. They had to mitigate the detrimental impact that pervasive social ills within their constituencies had on their ability to interact with their residents and to facilitate services. Their brokering role also extended to mediating tensions sparked by competition to secure public services wrought by generalised economic depression, and most acutely experienced with public housing and job creation schemes. One aspect of this conflict mitigation role could be construed as more pre-emptive than mediatory: councillors engaging their constituents in a more personal and somewhat pastoral manner, akin to discharging a duty of care. These councillors were being expected to do more than simply broker municipal services: essentially they were being tasked to restore and sustain trust.

In mixed-income wards councillors experienced cross-cutting pressures to reconcile and juggle their time and resources to satisfy the competing interests of an economically diverse clientele, especially in lower-income suburbs. In both mixed-income wards, however, it was also evident that higher-income residents, typically self-organised through residents’ associations, were sensitive to and understanding of the depth of need amongst their lower-income neighbours. However, despite the relative success of councillors in mixed-income wards in raising awareness about the starkly different needs of their residents, there were also ‘wedge’ issues, notably the concerns of higher-income residents and businesses to contain informal activities (eg trading, homelessness/vagrancy), that maintained pressure on councillors to manage conflicting interests.

At the outset of the study, councillors in high-income wards were assumed to play a placeholder and maintenance role. This was largely although not completely borne out in the findings: councillors’ advocacy of prominent issues of concern to residents such as homelessness (vagrancy) and land-use planning highlighted the importance they attached to maintaining the spatial integrity of their wards. In other issue areas that high-income wards shared with low- and mixed-income wards (eg crime and crime prevention, youth, sport and recreation) it was evident that councillor roles in the higher-income wards were more confined and compartmentalised than those of their counterparts in lower-income wards, where councillors had to confront the cascading effect of wider social problems. It was also evident that the ability of residents’ associations in high-income wards to leverage private funding to expedite service delivery lessened their expectations of councillors. Nevertheless, councillors in high-income wards still had to play a civic mobilisation role – but unlike in low-income wards, this was not primarily driven by a trust deficit, but rather by complacency – to supplement the efforts of relatively empowered residents.

In conclusion, the study findings were consistent with previous research in this field, and largely validated the heuristic model of ward councillors’ roles presented in Table 1. They also offered important contextual understanding about how and why these roles are exercised in differing socio-economic contexts. The author acknowledges that the research in this study was limited, as it was confined to analysis of a single type of secondary data (media reports) and one-off interviews with a small number of ward councillors. It nonetheless offers fruitful avenues for additional rigorous testing of the validity of councillor role types, including more extensive on-the-ground and repeat11 observations of how ward councillors engage with and respond to the socio-economic interests of their constituents.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

Askim, J. and Hanssen, G.S. (2008) Councillors’ receipt and use of citizen input: experience from Norwegian local government. Public Administration, 86 (2), 387–409. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2008.00722.x

Barichievy, K.L., Piper, L. and Parker, B. (2005) Assessing “participatory governance” in local government: A case-study of two South African cities. Politeia, 24 (3): 370–393.

Bénit-Gbaffou, C. (2008) Are practices of local participation sidelining the institutional participatory channels?: Reflections from Johannesburg. Transformation, 66/67, 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1353/trn.0.0003

Buccus, I.D., Hemson, J., Hicks, J. and Piper, L. (2008) Community development and engagement with local governance in South Africa. Community Development Journal, 43 (3), 297–311. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bsn011

Cameron, R. (2001) The upliftment of South African local government? Local Government Studies, 27 (3), 97–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/714004109

Copus, C., Sweeting, D. and Wingfield, M. (2013) Repoliticising and redemocratising local democracy and the public realm: why we need councillors and councils. Policy & Politics, 43 (3), 389–408. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557313X670136

De Visser, J. (2009) Developmental local government in South Africa: Institutional fault lines. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, (2) 7–25. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.v0i2.1005

Du Toit, J.L. (2010) Local metropolitan government responses to homelessness in South Africa. Development Southern Africa, 27 (1), 111–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/03768350903519390

Esau, M. (2007) Deepening democracy through local participation: Examining the ward committee system as a form of local participation in Bonteheuwel in Western Cape. Occasional Paper No. 6. Cape Town: University of the Western Cape.

Heller, P. (2009) Democratic deepening in India and South Africa. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 44 (1), 123–149. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021909608098679

Mail and Guardian. (2017) SALGA survey reveals extent of violence against councillors: Service delivery suffers. Available at: https://mg.co.za/article/2017-10-20-00-salga-survey-reveals-extent-of-violence-against-councillors-service-delivery-suffers [Accessed 7 May 2019].

Millstein, M. (2010) Limits to local democracy: The politics of urban governance transformations in Cape Town. Working Paper No 2. Visby: Swedish International Centre for Local Democracy.

Ministry for Provincial Affairs and Constitutional Development. (1998) The white paper on local government. Pretoria: Ministry for Provincial Affairs and Constitutional Development.

Paradza, G.L., Mokwena, L. and Richards, R. (2010) Assessing the role of councillors in service delivery at local government level in South Africa. Research Report 125. Johannesburg: Centre for Policy Studies.

Piper, L. and Deacon, R. (2009) Too dependent to participate: ward committees and local democratisation in South Africa. Local Government Studies, 35 (4), 415–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930902992683

Provincial Treasury. (2018) Municipal economic review and outlook 2018. Cape Town: Western Cape Government.

Research Branch: Organisational Policy & Planning. (2018) State of Cape Town, 2018. Cape Town: City of Cape Town.

SALGA GTZ. (2006) Handbook for municipal councillors. Tshwane: SALGA.

Smith, T. and De Visser, J. (2009) Are ward committees working? Insights from six case studies. Cape Town: Community Law Centre, University of the Western Cape.

South African Cities Network. (SACN) (2016) State of South African cities report 2016. Johannesburg: SACN.

Tan, S.F., Morris, A. and Grant, B. (2016) Mind the gap: Australian local government reform and councillors’ understandings of their roles. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, (19), 19–39. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.v0i19.5447

The Presidency. (2016) Development indicators 2016. Pretoria: The Presidency.

Thornhill, C. (2008) The executive mayor/municipal manager interface. Journal of Public Administration, 43 (4.1), 725–735.

Vivier, E. and Wentzel, M. (2013) Community participation and service delivery: Perceptions among residents in Cape Town. Journal of Public Administration, 48 (2), 239–250.

1 A report by the South African Local Government Association documented instances of intimidation and killing of councillors (Mail and Guardian 2017).

2 Based on Gini coefficient scores for nine South African metropolitan areas (including Cape Town) and secondary cities, compared against selected African cities, based on UN-HABITAT data for 2008.

3 However, the CoCT’s Gini coefficient remains high, and according to the Western Cape Provincial Treasury (2018) the CoCT experienced rising inequality between 2012 and 2017.

4 Based on data presented in SACN (2016). Data for access to basic services and percentage of poor households tracks changes between 2001 and 2011. Data for 2012–2016 measures household poverty according to racial demographic group, and is contained in Research Branch: Organisational Policy & Planning, City of Cape Town, (2018).

5 The suburbs were Bellville, the central business district, Mitchell’s Plain, and Khayelitsha.

6 Du Toit’s (2010) survey of metro responses to the street homeless in Johannesburg, eThekwini, Cape Town and Tshwane observed a common pattern in the homeless being policed.

7 This was also apparent with public transport, which was most frequently cited in high-income wards. For example, in ward E, the councillor and residents challenged the legal right of a private bus company to operate a commuter bus service through the ward.

8 The ward councillor for the other mixed-income ward (A) also indicated, in an interview, that the issue of vagrancy or homeless people was a complaint confined to higher-income areas of the ward.

9 The property-related issue in ward F (high income) concerned a state-owned block of flats that had been the subject of complaints by neighbours for the unruly and disorderly behaviour of its residents.

10 Substance abuse overlapped considerably with the protection and empowerment of youth in both low-income wards.

11 The author was involved in an experimental research study in 2016/2017, where graduate students were recruited to track councillors in Cape Town, Johannesburg and Durban. The study was conducted in partnership with colleagues at MIT.