Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, Issue 21, December 2018

ISSN 1836-0394 | Published by UTS ePRESS | https://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/journals/index.php/cjlg

RESEARCH AND EVALUATION (PEER REVIEWED)

Municipal finance for housing: local government approaches to financing housing in cities

Christopher Feather

Kalamu Consulting, Nevada 89138, United States of America. Email: CF@KalamuConsulting.com; Twitter: @KalamuConsult

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.v0i21.6517

Article History: Received 08/03/18; Accepted 31/10/18; Published 01/04/2019

Citation: Feather, C. 2019. Municipal finance for housing: local government approaches to financing housing in cities. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, Issue 21, December 2018, 6517. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.v0i21.6517

© 2019 Christopher Feather. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Declaration of conflicting interest The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Funding The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Abstract

Housing policy is usually seen as the domain of national governments, and in many countries local authorities have relinquished direct engagement in the promotion of adequate housing. High costs associated with related policies and programmes are often cited as justification for minimal involvement, leading to fewer community-level interventions on affordable formal housing. This article presents financial approaches for local government leaders and decision-makers to consider in furthering affordable access to adequate housing for their citizens. The article argues that when local governments engage on housing with innovation and financial pragmatism, the housing needs of the urban poor and vulnerable can be better served.

Keywords:

Municipal finance, local government, affordable housing, fiscal policy, cities, capacity-building

Introduction

Close to one billion people live in informal housing (PSUP 2016). Living conditions include overcrowding, the absence of permanent walls, and sufficient living area, running water or toilets. The reality of one-eighth of the global population being housed in slum conditions underscores the magnitude of the global adequate housing shortage (OHCHR/UN-Habitat 2010). Access to affordable formal housing presents one of the most formidable challenges for sustainable urban development, requiring the mobilisation of both international and national actors.1

The United Nations (UN) has developed an international urban framework to “make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable” as established in Sustainable Development Goal 11 (UN ECOSOC 2017, p. 11). Nation-states further committed to a ‘New Urban Agenda’ following the UN Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development known as Habitat III (UNGA 2017). These international protocols underscore the interests of national governments to collectively overcome local problems and promote sustainable urban development (Mitlin et al. 2018; Ladner et al. 2018). Key among the national stakeholders are cities, since municipalities lead the way in serving urban citizens and providing local services.

National and sub-national governments2 throughout the world have started to adopt the UN’s ‘housing at the centre’ approach to their development planning (UN-Habitat 2015). However, limited financial resources pose a central challenge to the goal of adequate housing for all. The costliness of housing has discouraged many leaders and policymakers in city governments from prioritising engagement on affordable housing. Understandably, given their greater financial resources, housing and issues of affordability have primarily become the responsibility of national governments (Datta and Jones 2001). Yet the lack of input by municipalities has limited the success of housing interventions in communities. Without localised expertise and substantive local involvement, large-scale and standardised national housing programmes have limited impact in meeting housing needs, especially for the urban poor and most vulnerable – threatening to make formal housing ever more inaccessible and unaffordable.

This article argues that city leaders can no longer remain idle on housing policy due to financial constraints. The essential role of local governments continues to grow, with the majority of the global population now living in cities (54% in 2014, and rising). Pressure will intensify, as over two-thirds of the world population will likely be urban by 2050 (UN DESA 2018). City leaders must consequently act on housing and its affordability to advance sustainable urban development for all current and future urban dwellers.

The article presents five approaches to financing affordable formal housing for city governments to consider. The research methodology utilised here derives the five approaches from public finance principles enumerated in academic, government and civil society studies (Stiglitz 2002; De Mello Jr. 2002; Hamilton 1975; Hansen and Perloff 1944). These principles are then illustrated through geographically diverse case studies selected from analysis of practitioner literature. While these approaches do not constitute definitive solutions, and it may be difficult to achieve the balance of policy interests with revenues and expenditures, this research provides a starting point for local government to reassess its role on a topic fundamental to the future of socio-economic development.

Municipal budget shortfall for housing

Often, financial resources for housing are limited at the local level (Collier et al. 2017). Municipal fiscal resources are commonly only enough to run local services such as waste management, sanitation systems, policing, fire protection and social services (Slack 2009). Furthermore, many cities encounter difficulties in compensating their own employees, much less finding the financing for housing.

On average a city spends 30% of its total municipal budget on salaries and only 1.35% on housing programmes.3 The high concentration of city expenditure on personnel emoluments and administrative expenses, followed by provision of local services, limits resource allocation for capital expenditure, including housing programmes. As a result, municipalities under-resource housing policies; too frequently human settlements are merely a formal line item in city budgets, with little, if any, funding allocated.

The limited nature of municipal fiscal resources has led to a tendency for housing providers to bypass city government decision-making. Although private and non-profit residential developers work with cities on urban development and building design, especially in terms of zoning and permits, municipalities have been unable to promote the provision of affordable housing due to lack of financial resources (Brueckner 1981). The consequence of insufficient municipal finance is that those city-led affordable housing projects which do exist are small-scale, and operate in what can be best described as a “fragmented policy landscape” (Lawson et al. 2010, p. 5; Pugh 2001). It is true that cities have been able to encourage affordable housing through mixed-use development mandates and zoning legislation to promote infill, densification and the conversion of non-residential buildings. However, financial approaches have been inadequately integrated with city planning and regulations to effectively promote affordable access to formal housing.4

To overcome the housing bottleneck, cities have the potential to contribute innovative policy solutions supported by feasible and financially pragmatic implementation strategies. It is possible for municipalities to change the status quo and assert a leadership role in housing, given their unique authority and local expertise (Province of Ontario 2011; UCLG 2010). And, with sustainable financing alongside city-level leadership on housing, local governments will be better positioned to serve the needs of their communities.

However, proactive city-level involvement on housing, backed by sustainable financing, requires local authorities to develop the fiscal architecture needed to support this financing. An effective large-scale affordable housing response supported by cities has essentially two components (Milligan et al. 2009). It requires local authorities to have committed public funds for housing programmes and policies; and they need to attract cost-effective private and non-governmental financing (Milligan et al. 2009). It is also recommended that cities seek ways to actively generate capital from public and private sources. Strengthening municipal finance for housing requires strategic approaches which can develop sustainable funding and then apply it effectively, to skilfully serve the housing needs of citizens at the local, community level.

Five strategic approaches for cities to sustainably finance housing

In order to strengthen municipal finance for housing, cities must at a minimum develop recurrent funding (Lawson et al. 2010). Regularised financing helps cities promote access to affordable housing to meet the needs of their communities. Although local budgets account on average for 25% of public expenditure in European Union states, in many developing countries the figure is less than 5% (UCLG 2010). Cities must accordingly improve financing to support the effectiveness of housing policies and programmes.

The following section of the article presents five strategic approaches (summarised in Table 1) for city leaders to consider in strengthening financing to effectually provide adequate housing for lower-income and vulnerable residents.5 The presented approaches are supported with global case studies from developed and developing states in different regions of the world. Although these five strategic approaches are not exhaustive of the potential solutions, they intend to stimulate greater dialogue on the role of local authorities and ways to improve municipal finance for housing. The approaches may not necessarily comport with every municipality and its circumstances, but they can help towards building local government capacities towards resolving outstanding housing issues. The outcome can be increased discussion and debate on ways to make unaffordable adequate housing an outmoded phenomenon of the past rather than an inevitability in the future.

i. Co-finance housing programmes and projects with regional and national governments

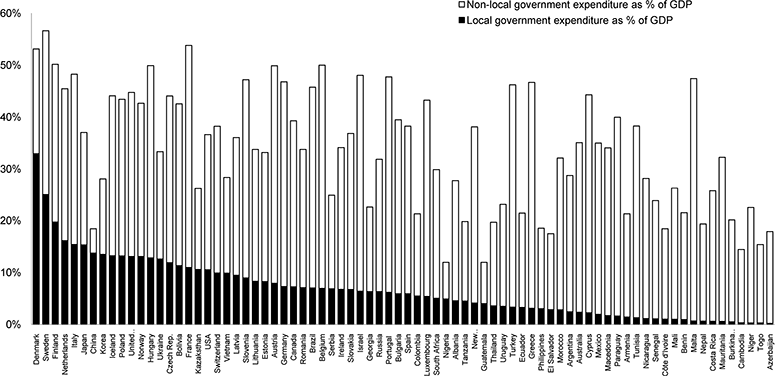

On their own, municipalities customarily have neither the resources nor powers to create a large-scale financing model for affordable housing (Lawson et al. 2010). Compared to national and regional governments, local authorities commonly have fewer resources. Figure 1 illustrates the extent to which higher-level government entities typically have greater financial resources than municipalities. In these instances, close collaboration between local, national and regional levels has proved critical to financing affordable housing programmes (UCLG 2010).

Figure 1 Comparing local and non-local* government expenditure as percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Source: UCLG and Dexia (2007). *Non-local government expenditure is defined as expenditure by national, provincial and state entities

Joint mobilisation of funds to finance housing can benefit both municipalities and their housing stakeholders, by uniting local community expertise from city government with technical housing support from the national and regional levels. Moreover, merging resource pools through intergovernmental transfers, such as subsidies or grants, enables cities to have greater financial resources for meeting local housing needs.

Municipal use of intergovernmental transfers is widespread (Banful 2011; Saiegh and Tommasi, 2000; Ma 1997). There are multiple mechanisms cities use to access such funds, which include financing for housing. In many countries, city governments and their housing departments receive an annual allocation from the national government to help lower-income households and vulnerable persons, such as those with disabilities, with their housing needs.

Rental subsidies supplement incomes and assist the less fortunate by making housing more affordable (Hulchanski 2003). Subsidy transfers are typically distributed to local authorities based upon a formula agreed between city officials and their national government counterparts, and then applied equitably to each regional and local government. For example, in France social housing is a shared responsibility. Local authorities co-finance social rental housing supply with funding from the central government through upfront subsidies.

Co-financing by different levels of government can be characterised by intense bargaining, sometimes resulting in conditions placed on city administrations (Basolo 2000; Schneider and Logan 1985). National and regional governments can mandate municipalities to make fiscal reforms as a condition of receiving housing subsidies. Further, local governments can be required to use non-local grants for specific purposes. Local governments might, for example, compete and apply for funding from the central government to contribute towards a national housing priority such as ending chronic homelessness. Alternatively, city leaders might identify grassroots housing issues, perhaps unique to their communities, and appeal directly to regional and national governments to determine their interest and the feasibility of accessing funds.

ii. Strengthen taxation mechanisms to improve revenue for housing programmes

Financing for housing is often derived from national government funding sources. At the highest level, the national government can frequently call on a wider range of taxation mechanisms, such as value-added tax (VAT) or income tax, than local governments can (Tanzi and Zee 2001). Consequently, central governments usually have deeper fiscal pools, which currently make them the logical choice for financing housing. Local authorities may seek to replicate this strong tax base and consider measures to optimise taxation in their municipalities so they can finance housing at the community level. Ultimately, strengthened taxation can contribute to municipal needs for recurrent funding for affordable housing programmes and projects.

Because of their tax structure, local governments commonly have fewer resources than national and regional governments, partly due to a smaller taxpayer base and partly due to the types of tax mechanisms employed. Local governments tend to rely on property taxes to fund most of their budget (Slack 2009). After property taxes, municipalities use, to a lesser extent, consumption taxes such as VAT and sales taxes to provide an elastic source of revenue that grows with the urban economy (UCLG 2010). In addition, municipalities also employ payroll taxes to ensure non-resident commuters pay for services (Slack 2009).

And finally, cities can implement local income taxes. Although rarer, municipal income taxes are commonly collected in Europe as a proportion of central and provincial income taxes (Slack 2009). A separate locally administered income tax is less common because it is difficult to implement and expensive to administer. Together, these property, consumption and income taxes constitute the main sources of tax revenue for municipalities

Understanding the relationship between tax modalities and revenue is an important first step in overcoming municipal government revenue challenges to finance housing programmes. Some tax experts believe property tax is not the optimal mechanism to fund housing policies, since it is a regressive tax6 (Kim 2017) and therefore reliance on it generally results in fewer funds for municipalities, which in turn means limited funding for housing. By comparison income taxes, which have a more redistributive effect, may be considered better suited for financing affordable housing programmes and policies that support lower-income and vulnerable residents (Tanzi and Zee 2001).

Many of the challenges municipalities confront in financing housing stem from having too small a tax base. Cities must therefore optimise both ‘what’ and ‘who’ is, or should be, taxed. Tax modifications should be assessed from a holistic perspective based on the effectiveness of the range of taxes – covering goods, services, incomes and assets, including housing. Effective taxes must also take into consideration their impact in promoting social equity and inclusive economic development at the neighbourhood level (Basolo 2000; Hansen and Perloff 1944).

Municipalities may also consider actions to optimise tax administration. Strengthening tax collection and controlling expenditure can maximise tax efficiency and help ensure there are greater tax revenues for allocation to housing programmes and projects. Equally, cities can also implement approaches to increase tax compliance, both domestically and internationally, to make certain taxpayers and evaders pay their fair share to the local government.

Lastly, it is advisable for local authorities to consider structuring taxation mechanisms so that they both incentivise affordable housing developers and financiers, and draw informal economy wages into the formal economy. Such incentives and inducements may change government revenues, negatively for the incentives and positively for the informal wages. The added incentives may potentially encourage affordable housing development and recognise the informal sector as a source of economic activity, which in turn can increase affordable housing opportunities and formal economic participation respectively (TJN-A 2012).

iii. Explore enhancements to non-taxation revenues to fund city housing policies

Non-taxation revenues for municipalities are typically concentrated in user charges (e.g. fines, and fees for business permits and licences). Through user charges, customers pay for the services they receive from local authorities. For example, persons using recreational facilities, such as a park or swimming pool, may pay a fee upon entrance, which then goes to the maintenance and servicing of the city-provided amenity (Bird 2003).

For affordable housing, however, user charges may not be a good choice for municipal financing. Requiring low-income tenants to pay user fees in accessing affordable housing would add to their income burden. Should tenants have the capital, they would already be able to access housing at prevailing market rates. Additionally, the overuse of such charges to finance housing can be considered regressive, as it asks low-income residents to pay the most for affordable housing. This is why tenant rents for affordable rental units are often supported with a mix of co-financed subsidies to help close the affordability gap.

Although user charges may not be optimal for direct financing of affordable housing in cities, they can nevertheless supplement municipal financing in other areas: potentially freeing up municipal and citizen funds for housing. For example, user fees for transportation can contribute to the development of better infrastructure, and improved roads can also boost household incomes by shortening commute times, which in turn reduces petrol consumption so citizens have more money to spend on housing. In Istanbul, for instance, the revenues from İSPARK, the municipal parking organisation, are higher than the combined budgets of 52 provincial municipalities, earning ₺ 40m per year (Hürriyet Daily News 2013). These revenues likely do not directly support municipal housing programmes, but do demonstrate the potential of non-taxation revenues. Revenues from user charges can reduce strains on the city budget and minimise other municipal expenses.

Local housing authorities also engage in cross-subsidisation to overcome the difficulties faced in financing affordable housing developments. Cross-subsidisation provides a useful non-taxation means for city leaders to finance housing initiatives targeting the poor and vulnerable. By charging a premium to the higher-income in market-level housing units, municipalities can channel the extra funds acquired into affordable rental housing.

Cross-subsidisation mechanisms, however, can be difficult to implement. The progressive fee structure can alienate those with higher incomes and limit their willingness to participate in these schemes. Moreover, it is possible that the provision of a mixed-income environment may be a disincentive for higher-income households who may avoid such projects altogether.

Beyond user charges and cross-subsidisation, cities can also harness non-financial means to mitigate the high cost of housing programmes and projects. Municipalities can donate, lease or sell public land at below-market rates to encourage affordable rental or ownership developments (Province of Ontario 2011).

Donation of land is a popular tool for municipalities to employ, since housing development costs are much higher than what can be charged through rent to low-income tenants. Developers can use free land as an in-kind contribution to enable affordable housing provision (Zhou and Ronald 2017; Morrison et al. 2012; Firman 2004). Hence, land-use planning provides a non-financial means that can be used to promote housing development accessible to lower-income households. Nevertheless, additional subsidies and investment are also needed. Municipalities should be fully committed to ensuring land donations are properly used to achieve their intended objective.

Land contributions do have their disadvantages. Such actions in effect remove these real estate assets from the municipal balance sheet (Lin 2014). Moreover, it is a once-only solution that can limit the decisions of future city leaders. In addition, these arrangements could risk exploitation of local authorities from developers seeking excessive profits, thereby corrupting local officials in the process (Ren 2018; Butler et al. 2009). As such, the sole provision of land does not necessarily benefit the community in terms of promoting affordable housing. Municipalities must exert strict enforcement on land transactions to ensure development actually delivers the intended benefits for the community (Berrisford et al. 2018).

Besides land donations and discounts, cities can also use legal instruments to require developers to provide affordable housing: another non-financial tool to reduce strain on municipal coffers and promote access to affordable housing in urban areas. The city government of Munich, for example, requires private developers to allocate 20% of new housing units on large sites to social and affordable housing (Scanlon et al. 2014). In Denmark, municipalities have the legal right to assign tenants to at least 25% of unused housing units (Scanlon et al. 2014).

The above examples of non-taxation sources illustrate the creativity and flexibility local authorities can apply as they seek to supplement municipal financing in support of city housing policies. Many other alternatives can be formulated to amplify sources of funding. But local authorities should be attentive that prospective non-taxation mechanisms are developed in a responsible manner. City leaders and policymakers nonetheless may consider harnessing non-taxation approaches as a financial tool to strengthen municipal finance of housing.

iv. Assess debt financing to serve municipal housing needs

When municipalities do not have the fiscal resources to finance housing, they can consider debt financing.7 Cities can develop housing bonds to generate the needed cash flow, and debt financing can be an important instrument to support housing programmes at the municipal level. The proceeds can be used to improve affordable access for many groups: lower-income borrowers, first-time homebuyers, persons in vulnerable situations etc.8 (Rieman 2013). In addition, debt-derived proceeds can be used to fund the development of multi-family housing. Once completed, these apartments can be let at lower rents, as they have been less costly to produce. As a result, debt financing can be an important tool in delivering housing affordable to lower-income groups (Rieman 2013).9

Cities employ two common approaches to debt financing for housing (Lawson et al. 2009; Zhang 2000). The first mechanism is direct public lending from financial institutions to municipalities. Often, depending upon the city’s underlying financial state, municipalities have bargaining power to access cheaper capital through loans with the financial sector. Usually loans, especially those related to infrastructure, are evaluated on a project-by-project basis. Once approved, the municipality agrees to pay back the principal and interest over a period based on the timeline for the project. However, it should be noted that accessing capital through public loans requires developed financial institutions to be agreeable to, and capable of, providing municipalities the necessary liquidity for housing. Without such capital, lending at acceptable terms becomes an option of limited viability.

Second, municipalities can issue bonds to finance housing development. Bond issuance10 may attract investor capital rather than requiring a municipality to engage bilaterally with financial institutions. The development of housing bond debt instruments allows cities to access domestic, and potentially international, capital markets to finance affordable housing. However, the issuance of municipal bonds to finance housing requires cities and their projects to have demonstrable credibility with investors, and to develop a product with a competitive advantage compared to similar investment class products. But, if a municipality’s bonds are well received by the market, the borrowed capital can be a significant source of financing for housing.

Debt financing to support municipal financing for housing is an important approach, although city leaders must be alert to potential problems, and realistic and fully committed to this type of financing if they choose to undertake it. It is important for leaders to understand the terms and conditions of the bond, and honour their debt obligations. The borrowed capital comes with principal and interest repayments that must be managed, while bond instruments need to compete successfully with other types of investment. When properly executed with complete responsibility from the municipality, debt financing can be a sustainable approach to the development of affordable housing units for lower-income and vulnerable citizens.

v. Leverage public–private partnerships to encourage private capital and non-governmental expertise

Local governments do not generally have the capacity alone to finance, deliver and manage comprehensive affordable housing programmes. Therefore municipalities must work with non-governmental housing actors, including the private sector and civil society, to use participatory processes11 to develop strategic institutional partnerships with non-governmental housing actors (Christensen and Gabe 2018).

Engaging actors outside of government through public–private partnerships (PPPs)12 to finance housing does not just supplement municipal fiscal resources (Moskalyk 2011). PPPs also better align civil society and business partners towards delivering desired housing outcomes. As city resources are limited, partnering with private businesses and non-governmental organisations can be effective in both financing and delivering affordable housing. Thus, PPPs merit strong consideration from city governments as they consider approaches to promote the financing of affordable housing in their communities.

Under PPPs, the private sector produces affordable housing with oversight from the public sector. PPPs are well documented for generating efficiency gains in infrastructure construction and financing. (Moskalyk, 2011) They are able to bring private capital into developments which are socially needed, but not commercially viable independently

Partnerships between city governments and the private sector have been proven to significantly contribute to lower costs and increased operating efficiencies for affordable housing projects. Besides cost savings and optimised infrastructure delivery, PPPs enable risk-sharing on affordable housing projects with the private sector. However, PPPs do require significant efforts and coordination to be effective and beneficial for both sides of the partnership. Local authorities should be vigilant in overseeing developments throughout the lifecycle of PPPs. Strong supervision can ensure contractors are meeting local authority standards. It is also advisable that municipal governments strategically adapt their requests to the changing needs and ongoing priorities of the community as they develop.

Although municipalities are constrained in financing housing due to limited public resources, they still have a mandate to meet basic human needs, and they are also under increasing public pressure for greater accountability. These factors have led many local authorities to consider PPPs for housing, with these arrangements becoming increasingly permanent and comprehensive (Abdul-Aziz and Kassim 2011; Tang et al. 2010). PPPs can replace confrontation with collaboration, by building innovative alliances between municipalities and housing developers and financial institutions. These can ensure the most efficient use of public and private resources in the pursuit of mutual gains.

The PPP approach to housing projects has typically included the creation of a joint venture company within which the private sector and municipal government jointly finance, own and operate a housing development. Risk is shared according to predetermined contractual provisions, based on each partner’s respective strengths and weaknesses. In this model, the municipal government often contributes significant fiscal resources and maintains overall control of the planning and development stages, but draws on the private sector’s resources and expertise in construction and design.

PPPs for financing housing merit consideration from municipalities. As government subsidies become increasingly limited, PPPs present a growing opportunity to engage a diverse range of housing actors and leverage capital and expertise. The advantages of this approach have the potential to make the difference in promoting access to affordable, formal housing for all.

The way forward: sustainably developing city financing for housing

As the world continues to urbanise, local governments will be required to increase their engagement on affordable access to adequate housing. Cities will encounter financial constraints in meeting local housing needs while concurrently developing municipal housing policies that serve their communities. Municipalities should not retreat from this challenge, but instead find innovative and pragmatic solutions to finance affordable formal housing in their cities.

Municipal leaders can consider the presented financial approaches to help finance the housing needs in their neighbourhoods. Depending on the circumstances, the municipality should first have a comprehensive understanding of present housing conditions in its constituency. Once these are well understood, the local government should develop a practical strategy to achieve its desired housing policies.

After sufficiently quantifying the financial requirements to deliver the housing strategy, the local government can then consider the financial approaches discussed in this article. Should subsidies or grants be available from national and regional governments, the local government can assess the merit of these funding sources, especially in terms of the future sustainability of these funds and the conditions that accepting monies may impose. The local government can also evaluate its fiscal standing in terms of municipal taxation and expenditure. Specifically, the municipality can examine ways to raise revenue or cut expenditure to meet the funding needs required for the desired housing programmes. This fiscal evaluation can even extend to examining non-taxation options, such as discounted land provision, strategic introduction of user fees or cross-subsidisation. In scenarios where these approaches are not sufficient, or income can be generated from investment, debt financing can be considered – either via financial sector loans or by issuing bonds, depending on the credit standing of the municipality. Additionally, PPPs can be considered as an important tool for a local government to harness private sector expertise and work in a collaborative and mutually beneficial manner.

Regardless of a local government’s circumstances, the five approaches outlined provide a starting point for city leaders and local policymakers to consider as they seek to expand access to adequate housing for their neighbourhoods. While these approaches are neither exhaustive nor applicable to each and every situation, they serve to provoke a dialogue on the role of cities in promoting affordable, formal housing accessible to the urban poor and the vulnerable.

Through improvements and innovations in revenue collection and coordination between different levels of government, private and other non-governmental actors, local governments can deepen financing for housing policies and programmes at the community level. The approaches detailed here provide an opportunity to reappraise the current system of public finance (Pugh 1994), where local government can develop a financial way forward on housing to fulfil their mandate of inclusive and sustainable urban development for all.

Acknowledgement

The author is grateful to the editor and the anonymous referees for their valuable feedback.

References

Abdul-Aziz, A.R. and Kassim, P.J. (2011) Objectives, success and failure factors of housing public–private partnerships in Malaysia. Habitat International, 35 (1), 150–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2010.06.005

Adamsen, P. (2014) IFHP presents: Voices from The Hague Housing Conference. International Federation for Housing and Planning (IFHP). Available at: https://www.ifhp.org/ifhp-blog/ifhp-presents-voices-hague-housing-conference-1.

Andersen, H.S. (2002) Can deprived housing areas be revitalised? Efforts against segregation and neighbourhood decay in Denmark and Europe. Urban Studies, 39 (4), 767–790. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980220119561

Baitu, J. (2010) The organisation, management and finance of housing cooperatives in Kenya. Nairobi, Kenya: United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat).

Banful, A.B. (2011) Do formula-based intergovernmental transfer mechanisms eliminate politically motivated targeting? Evidence from Ghana. Journal of Development Economics, 96 (2), 380–390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2010.08.012

Basolo, V. (2000) City spending on economic development versus affordable housing: Does inter-city competition or local politics drive decisions? Journal of Urban Affairs, 22 (3), 317–332. https://doi.org/10.1111/0735-2166.00059

Berrisford, S., Cirolia, L.R. and Palmer, I. (2018) Land-based financing in Sub-Saharan African cities. Environment and Urbanization, 30 (1), 35–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247817753525

Bird, R. (2003) User charges in local government finance. Washington DC, United States of America: The World Bank Group (World Bank).

Brueckner, J.K. (1981) Zoning and property taxation in a system of local governments: Further analysis. Urban Studies, 18 (1), 113–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420988120080091

Butler, A.W., Fauver, L. and Mortal, S. (2009) Corruption, political connections, and municipal finance. The Review of Financial Studies, 22 (7), 2873–2905. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhp010

Centre for Affordable Housing Finance in Africa (CAHF). (2017) Housing finance in Africa yearbook 2017. Available at: http://housingfinanceafrica.org/app/uploads/2017_CAHF_YEARBOOK_14.10-copy.compressed.pdf.

Christensen, P.H. and Gabe, J. (2019) Public regulatory trends in sustainable real estate. In: Walker, T., Krosinsky, C., Hasan, L.N. and Kibsey, S.D. (eds.) Sustainable real estate (pp. 35–76). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-94565-1_4

City of São Paulo. (2010) Municipal housing plan 2009–2024. São Paulo, Brazil: City of São Paulo.

City of Vancouver. (2016) How we fund the budget. Available at: https://vancouver.ca/your-government/funding.aspx.

Clos, J. (2015) UN-Habitat policy statement at the twenty-fifth session of the Governing Council. United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat). Available at: https://unhabitat.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/EDs-Policy-Statement_GC25_FOR-DELIVERY.pdf.

Collier, P., Glaeser, E., Venables, A., Manwaring, P. and Blake, M. (2017) Land and property taxes for municipal finance. London: International Growth Centre.

Datta, K. and Jones, G.A. (2001) Housing and finance in developing countries: Invisible issues on research and policy agendas. Habitat International, 25 (3), 333–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0197-3975(00)00038-2

De Mello Jr., L.R. (2002) Public finance, government spending and economic growth: The case of local governments in Brazil. Applied Economics, 34 (15), 1871–1883. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036840210128726

Eisenbud, D.K. (2016) Bill to double property tax on Jerusalem’s ‘ghost apartments’ approved. The Jerusalem Post 4 January 2016. Available at: https://www.jpost.com/Israel-News/Bill-to-double-property-tax-on-Jerusalems-ghost-apartments-approved-439361.

Fahy, M. (2016) Abu Dhabi introduces 3% municipal fee on expat home rentals. The National 12 April 2016. Available at: https://www.thenational.ae/business/property/abu-dhabi-introduces-3-municipal-fee-on-expat-home-rentals-1.139449.

Firman, T. (2004) Major issues in Indonesia’s urban land development. Land Use Policy, 21(4), 347-355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2003.04.002

Fischer, A. (2016) City of Vancouver: It’s a housing emergency. The Columbian 11 April 2016. Available at: http://www.columbian.com/news/2016/apr/11/city-vancouver-housing-emergency-low-income-households/.

French, M. and Hegab, K. (2010) Condominium housing in Ethiopia: The integrated housing development programme. United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat). Available at: https://www.humanitarianlibrary.org/sites/default/files/2013/07/3104_alt.pdf.

Gruis, V.H. and Nieboer, N. (2006) Social housing investment without public finance: The Dutch case. Public Finance and Management, 2006 (1).

Hamid, G. (n.d.) Incremental housing in Khartoum: A paradigm shift? Khartoum, Sudan: Global University Consortium Exploring Incremental Housing.

Hamilton, B.W. (1975) Zoning and property taxation in a system of local governments. Urban Studies, 12 (2), 205–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420987520080301

Hansen, A.H. and Perloff, H.S. (1944) State and local finance in the national economy. New York: WW Norton and Company.

Hulchanski, J.D. (2003) What factors shape Canadian housing policy? The intergovernmental role in Canada’s housing system. Conference on Municipal-federal-provincial relations in Canada. Kingston: 9–10 May.

Hürriyet Daily News. (2013) Istanbul parking income exceed budgets of 52 cities. 15 March 2013. Available at: http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/istanbul-parking-income-exceed-budgets-of-52-cities-43014.

International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2013) Government finance statistics yearbook, 2012. Washington DC, United States of America: IMF.

Kim, Y. (2017) Limits of property taxes and charges: City revenue structures after the Great Recession. Urban Affairs Review, 55 (1), 185–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087417697199

Ladner, A., Keuffer, N., Baldersheim, H., Hlepas, N., Swianiewicz, P., Steyvers, K. and Navarro, C. (eds.) (2018) Conclusions: Local autonomy – patterns, dynamics and ambiguities. In: Patterns of local autonomy in Europe (pp. 333–348). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham.

Lawson, J., Berry, M., Milligan, V. and Yates, J. (2009) Facilitating investment in affordable housing – towards an Australian model. Housing Finance International, 24 (1), 18–26.

Lawson, J., Gilmour, T. and Milligan, V. (2010) International measures to channel investment towards affordable rental housing. Melbourne, Australia: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI).

Li, X., Hui, E.C., Chen, T., Lang, W., Guo, Y. (2019) From Habitat III to the new urbanization agenda in China: Seeing through the practices of the “three old renewals” in Guangzhou. Land Use Policy, 81, 513–522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.11.021

Lin, G.C. (2014) China’s landed urbanization: Neoliberalizing politics, land commodification, and municipal finance in the growth of metropolises. Environment and Planning A, 46 (8), 1814–1835. https://doi.org/10.1068/a130016p

Lonardoni, F., Acioly, C. and French, M. (2013) Housing supply in Brazil: The “my house my life” programme. United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat). Available at: http://mirror.unhabitat.org/pmss/getElectronicVersion.aspx?nr=3453&alt=1.

Ma, J. (1997) Intergovernmental fiscal transfer: A comparison of nine countries (cases of the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia, Germany, Japan, Korea, India and Indonesia). World Bank Working Paper. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Magnusson, L. and Turner, B. (2008) Municipal housing companies in Sweden – social by default. Housing, Theory and Society, 25 (4), 275–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036090701657397

Milligan, V., Gurran, N., Lawson, J., Phibbs, P. and Philipps, R. (2009) Innovation in affordable housing in Australia: Bringing policy and practice for not-for-profit housing organisations together. Melbourne, Australia: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI).

Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Urban Development National Council for Physical Development and the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (MEFUD and UN-Habitat). (2014) Sudan’s report for United Nations’ third conference of housing and sustainable urban development (Habitat III) 2016. Khartoum, Sudan: MEFUD & UN-Habitat.

Mitlin, D., Colenbrander, S. and Satterthwaite, D. (2018) Finance for community-led local, city and national development. Environment and Urbanization, 30 (1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247818758251

Mombasa Budget Office. (2014) Mombasa county annual development plan: 2015–2016 financial year. Mombasa, Kenya: County Government of Mombasa.

Morrison, T.H., Wilson, C. and Bell, M. (2012) The role of private corporations in regional planning and development: Opportunities and challenges for the governance of housing and land use. Journal of Rural Studies, 28 (4), 478–489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2012.09.001

Moskalyk, A. (2011) Public-private partnerships in housing and urban development. United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat). Available at: https://unhabitat.org/books/public-private-partnership-in-housing-and-urban-development/.

New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA). (2015) NextGeneration NYCHA. New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA). Available at: https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/nycha/downloads/pdf/nextgen-nycha-web.pdf.

Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and the United Nations Human Settlements Programmer (OHCHR and UN-Habitat). (2010) The right to adequate housing. OHCHR and UN-Habitat. Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/FS21_rev_1_Housing_en.pdf.

Participatory Slum Upgrading Programme (PSUP). (2016) Slum almanac 2015/2016: Tracking improvement in the lives of slum dwellers. United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat). Available at: https://unhabitat.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02-old/Slum%20Almanac%202015-2016_EN.pdf.

Province of Ontario. (2011) Municipal tools for affordable housing handbook. Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing (MMAH). Available at: http://www.mah.gov.on.ca/AssetFactory.aspx%3Fdid%3D9270.

Pugh, C. (1994) Housing policy development in developing countries: The World Bank and internationalization, 1972–1993. Cities, 11 (3), 159–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/0264-2751(94)90057-4

Pugh, C. (2001) The theory and practice of housing sector development for developing countries, 1950–99. Housing Studies, 16 (4), 399–423. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673030120066527

Rating and Investment Information Inc. (R&I) (2016) R&I Affirms AA-, Stable: Tokyo Metropolitan Housing Supply Corp. Rating and Investment Information Inc. (R&I). Available at: https://www.r i.co.jp/en/news_release_cfp/2017/03/news_release_2017-A-0256_01.pdf

Ren, X. (2018) Governing the informal: Housing policies over informal settlements in China, India, and Brazil. Housing Policy Debate, 28 (1), 79–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2016.1247105

Republic of Ghana (RoG). (2015) The composite budget of the Accra Metropolitan Assembly for the 2015 fiscal year. Accra, Ghana: Government of Ghana.

Rieman, G. (2013) Housing bonds. Washington, DC: National Council of State Housing Agencies (NCSHA). Available at: http://nlihc.org/sites/default/files/2016AG_Chapter_5-6.pdf.

Saiegh, S. and Tommasi, M. (2000) An ‘incomplete-contracts’ approach to intergovernmental transfer systems in Latin America. In: Burki, S.J., Perry, G.E. and Eid, F. (eds.) Decentralization and Accountability of the Public Sector. (pp. 127–144). Washington, DC: World Bank.

Scanlon K., Whitehead C. and Arrigoitia, M.F. (eds.) (2014) Social housing in Europe. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118412367

Schneider, M. and Logan, J. (1985) Suburban municipalities: The changing system of intergovernmental relations in the mid-1970s. Urban Affairs Quarterly, 21 (1), 87–105. https://doi.org/10.1177/004208168502100108

Servicio de Administración Tributaria de Lima (SAT). (2016) Impuestos [Taxes]. Lima: Servicio de Administración Tributaria de Lima (SAT).

Slack, E. (2009) Guide to municipal finance. United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat). Available at: https://unhabitat.org/books/guide-to-municipal-finance/

Stiglitz, J.E. (2002) New perspectives on public finance: recent achievements and future challenges. Journal of Public Economics, 86 (3), 341–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-2727(01)00193-1

Tambun, L.T. (2015) Jakpro to build low-cost apartments, athlete housing complex. JakartaGlobe, 27 August 2015.

Tang, L., Shen, Q. and Cheng, E.W. (2010) A review of studies on public–private partnership projects in the construction industry. International Journal of Project Management, 28 (7), 683–694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2009.11.009

Tanzi, V. and Zee, H. (2001) Tax policy for developing countries. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Tax Justice Network Africa (TJN-A). (2012) Taxation and the informal sector. Nairobi, Kenya: TJN-A.

The Jakarta Post. (2015) Greater Jakarta: Jakpro cooperates with PP for city projects. 5 December 2015. Available at: http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2015/12/05/greater-jakarta-jakpro-cooperates-with-pp-city-projects.html

United Cities and Local Governments (UCLG). (2010) Local government finance: The challenges of the 21st century. Barcelona, Spain: UCLG.

United Cities and Local Governments and Dexia (UCLG and Dexia). (2007) Local governments in the world: Basic facts on 82 selected countries. Barcelona, Spain: UCLG and Dexia.

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA). (2018) World urbanization prospects: The 2018 revision. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA). Available at: https://population.un.org/wup/

United Nations Economic and Social Council (UN ECOSOC). (2017) Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals: Report of the Secretary-General. United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC). Available at: http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=E/2017/66&Lang=E

United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). (2017) Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 23 December 2016: 71/256 New Urban Agenda. United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). Available at: http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_71_256.pdf

United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat). (2015) Housing at the centre of the New Urban Agenda. United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat). Available at: https://unhabitat.org/housing-at-the-centre-of-the-new-urban-agenda/

Urban, F. (2015) Myth #7 Only immigrants still live in European public housing. In: Bloom, N.D., Umbach, F. and Vale, L.J. (eds.) Public housing myths: Perception, reality and social policy (pp. 154–174). Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Vereniging van Woningcorporaties (AEDES). (2013) Hoe financieren woningcorporaties de sociale woningbouw [How do housing corporations finance social housing]. Vereniging van Woningcorporaties (AEDES). Available at: https://www.aedes.nl/feiten-en-cijfers/geld-en-investeringen/hoe-financieren-woningcorporaties-de-sociale-wonin/hoe-financieren-woningcorporaties-de-sociale-woningbouw.html

Wilson, C. (2016) Vancouver declares affordable housing emergency. Oregon Public Broadcasting. Available at: https://www.opb.org/news/article/vancouver-washington-housing-affordable-emergency/

Zhang, X.Q. (2000) The restructuring of the housing finance system in urban China. Cities, 17 (5), 339–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0264-2751(00)00030-5

Zhou, J. and Ronald, R. (2017) The resurgence of public housing provision in China: The Chongqing programme. Housing Studies, 32 (4), 428–448. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2016.1210097

1 For housing to be adequate, at a minimum it must meet the following seven criteria: security of tenure; availability of services, materials, facilities and infrastructure; affordability; habitability; accessibility; suitable location; and cultural adequacy. This article focuses on cities’ role in promoting financing for affordable formal housing.

2 Sub-national governments in this paper are defined as regional (state, provincial and county levels) and local authorities. Local governments are defined as the public administration entities of cities and municipalities, including rural settlements.

3 Figures are based on author’s own calculations from municipal budgets for a selection of cities in Africa, Asia Pacific, Europe, Latin America, the Caribbean and North America.

4 The framework aligns with UN-Habitat’s three-pronged approach emphasising urban legislation, urban planning and design, and urban economy and municipal finance (Li et al. 2019; Clos 2015).

5 For success it is essential for local governments to be accountable to all constituents and to act in a fiscally responsible manner.

6 Compared to a progressive tax, a regressive tax takes a larger percentage from low-income people than from those with higher incomes.

7 Debt financing may not be legally permitted or allowed in certain jurisdictions. However, this approach is still presented for consideration depending on the circumstances of the local authority.

8 Through mortgage revenue bonds (MRBs), the borrowed cash flow proceeds can be credited to housing finance lenders to offer below-market rate housing loans (Rieman 2013). MRBs can target borrowers who earn no more than the area median income and have been proven to make homeownership possible for lower-income families (2013).

9 Multi-family housing bonds provide rental housing through the creation of multifamily units. These units are made more affordable to lower-income families that can qualify if their income is below area median income (Rieman 2013).

10 Municipalities have commonly used two classes of bonds: general obligation bonds and revenue bonds. Typically, general obligation bonds guarantee that investors will receive timely payment of principal and interest no matter what the cities’ financial circumstances. By contrast, revenue bonds carry the risk of not being repaid should the local authority not have the means to pay back investors.

11 Historically, political entities with non-existent or underperforming fiscal systems have required or encouraged labour, as part of their participatory process, to support infrastructure and housing construction. The Inca Empire institutionalised mandatory service through the mit’a system whereby a majority of the year was devoted to community-driven projects performed by Incan citizens. Alternatively, in communities throughout sub-Saharan Africa, members voluntarily come together to build housing for themselves and the community. Each member brings the required building materials and the focus is on construction of one housing unit at a time. This process has been reported to promote belonging and togetherness among communities, as group members who do not need a house also participate in the construction process (Baitu 2010).

12 Although public–private partnerships take many forms, they may be defined as “a private consortium to assume the financing risk [in] two or more phases of the project’s life-cycle, include[ing] design and construction as well as maintenance and operation” (Moskalyk 2011, p. 2).