Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, Issue 21, December 2018

ISSN 1836-0394 | Published by UTS ePRESS | https://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/journals/index.php/cjlg

RESEARCH AND EVALUATION (PEER REVIEWED)

Legislating community engagement at the Australian local government level

Department of Public Policy and Governance, University of Technology Sydney, NSW 2007, Australia

Email: Helen.Christensen@uts.edu.au

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.v0i21.6515

Article History: Received 17/10/17; Accepted 04/07/18; Published 01/04/2019

Citation: Christensen, H. 2019. Legislating community engagement at the Australian local government level. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, Issue 21, December 2018, 6515. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.v0i21.6515

© 2019 Helen Christensen. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Declaration of conflicting interest The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Funding The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Abstract

Community engagement has assumed a more salient role in the operations of Australia’s local governments. A vast number of legislative instruments and reporting requirements are imposed upon local governments by the states and the Northern Territory across Australia’s seven local government jurisdictions. Consequently, a set of identifiable practices is solidifying as a core element of local government practice and state–local relations. However, while practices have recently proliferated, it is easy to forget that they are relatively new. This article examines the legislative frameworks of Australian local government systems by chronologically mapping the development of legislation and other reporting requirements. It is argued that community engagement now occupies a central place in local government, and that the jurisdictions use four different types of approaches, often simultaneously, which can fruitfully be described as ‘prescriptive’, ‘aspirational’, ‘empowering’ and ‘hedging’. The discussion draws comparative observations and identifies key issues and challenges for the future of community engagement.

Keywords:

Community engagement; Australia; local government; public participation; legislation

Introduction

The past decade has witnessed increased interest in, and a proliferation of, the practices of community engagement in Australian local governments (Aulich 2009; Grant and Drew 2017; Head 2007, 2011). This article argues that the legislation set by the states and territories, which dictates how local governments are to engage their communities, is one of the main drivers for this proliferation. In the Australian local government context, ‘community engagement’ is the popular term used to describe all levels of engagement and participation, from giving information to seeking feedback, and from inviting input right through to collaborative governance. Terms such as ‘consultation’ and ‘participation’ are often used interchangeably with ‘community engagement’ and, as discussed here, this is adding to confusion in legislation and practice. However, for the purposes of the legislative review presented here, the broad definition of community engagement is adhered to.

There are several reasons offered for the proliferation of community engagement practice in Australian local governments. First is the quest for better and more democratic outcomes resulting from participatory processes (Bell and Hindmoor 2009, p. 137). Second, governments seek increased legitimacy through these practices (Fung 2015), in an environment of community activism and increasing distrust of government (Head 2007; Smyth et al. 2005). Third, community engagement may be undertaken as a response to increasing demands from communities (Bishop and Davis 2002; Head 2007; Herriman 2011). Fourth, the advent of technology has made it easier and more cost-effective for governments to engage with their communities (Bell and Hindmoor 2009). Fifth – and perhaps less noble – is the desire of governments to broaden the base of their decision-making responsibilities – and thereby share the potential blame for poor decisions (Bell and Hindmoor 2009; Head 2007).

It is important to note, however, that while the reasons local government practises community engagement are proliferating, support for community engagement is not universal. For example, Pini and Haslam McKenzie (2006) report that community engagement in small rural populations can be perceived as irrelevant, as community members can easily access their elected representatives anyway, and community engagement is therefore perceived as unproductive and wasteful. Another concern is the fear of creeping privatisation: Grant and Drew (2017) have pointed to ambiguities surrounding the roles of private sector organisations in facilitating community engagement on behalf of local governments.

The article has the following structure. It first outlines the methodology. It then provides an overview of how local governments are positioned in Australian jurisprudence and explores what purposes legislating community engagement might serve. Following this it gives a chronological account of requirements in the local government acts from each of the states and the Northern Territory, highlighting changes and other relevant contextual developments. Next, the author presents a comparative discussion of the development of the legislative approaches to community engagement and identifies challenges and issues. Finally, the article concludes by reflecting on the past and current trajectories of community- engagement-related legislation.

Methodology

This article reviews historical and current legislation from the Australian states and the Northern Territory, where community engagement is either referred to or legislatively required of local governments. The review focuses predominately on local government acts, but includes other relevant historical legislation and regulations in order to map the introduction and repeal of engagement requirements. As mentioned, the widely accepted definition of ‘involvement of community in decision-making’ is used (see, for example, Rowe and Frewer 2005, IAP2 n.d.) to identify which references and requirements involve community engagement. This is interpreted as any instance where local governments are encouraged or required to communicate with their communities, and to invite or provide opportunities for their communities to give comments, input, feedback or direction to councils; or even to collaborate with local government. A total of 41 statutes were examined. The requirements for community engagement were investigated using the following search terms of the legislative documents, both individually and in combination which each other: ‘consultation’, ‘engagement’, ‘public’, ‘community’ and ‘participation’. It should be noted that some of the historic legislation is not available online in a searchable format, and in these instances every effort was made to identify the relevant sections of the acts. The review was conducted throughout 2017 and 2018.

This article is the first to conduct a chronological, comparative and national review of the legislation. Other similar reviews have focused either on single jurisdictions (Grant et al. 2012; Prior and Herriman 2010; Wiseman 2006) or on a point in time (Grant et al. 2011; Grant and Drew 2017; Herriman 2011). By taking an inductive, historical approach the analysis allows for close comparison. For instance, it provides answers as to which state first took a particular approach; which states followed which; which states have atypical approaches; and how engagement requirements have been prioritised or reprioritised by individual state and territory governments. From this inductive methodology, the article derives a typology of approaches to legislating for community engagement which is referred to throughout the timeframes presented.

Legislative frameworks of Australian local governments

The Commonwealth of Australia is a federation of six states: New South Wales (NSW), Queensland (Qld), South Australia (SA), Tasmania (Tas), Victoria (Vic) and Western Australia (WA). The Commonwealth also has authority over ten territories, including the Northern Territory (NT). Seven of the ten territories are adjacent to the continent of Australia. All the states and the Northern Territory (NT) legislate for local government. The number and size of local governments varies within each state; there are currently 537 across all states and the Northern Territory. Figure 1 shows a map of the states and current number of local governments for each.

Figure 1: Map of Australian states with number of local governments

Source: Adapted from Grant and Drew (2017, p. 360) and Office of Local Government NSW (2018)

The legislative frameworks within which Australian local governments operate have two defining features. First, the Australian Constitution outlines a two-level system of government which includes the federal and state governments, but not local governments. While national constitutional recognition has not been achieved (see Grant and Drew 2017), since 2005 local government has been recognised in the constitutions of all the states, although to varying degrees (see Aulich and Pietsch 2002; Grant and Drew 2017; Saunders 2005; Twomey 2012). This lack of recognition at a national level has relegated local government to a ‘lesser’ or subordinate level of government (Brackertz 2013, p. 3; Twomey 2012). This in turn has contributed to uncertainty in a number of areas, such as: whether, and if yes how, the principle of subsidiarity ought to apply in Australia (Aulich 2005; Grant et al. 2016); shifting roles and responsibilities in response to political changes at the state and federal levels (Aulich 2009; Brackertz 2013; Dallinger 2009); financial constraints and dependencies (Brackertz 2013; Productivity Commission 2008; Twomey 2012); and the ability of local governments to be democratically responsive (Aulich 2009, 2015; Brackertz 2013). Furthermore, this list of issues suggests that Australian local government is a unified, comprehensive system of government; however, this is misleading. Without national constitutional recognition, local governments are statutory bodies or ‘creatures of state’, with their powers granted by the state or territory governments. With each state and the territory having its own statutory and common law and (importantly) political culture, reform processes and statutes reflect the distinctiveness of these jurisdictions (Grant and Drew 2017; Marshall et al. 1999) – although there are some overarching similarities.

Australian local governments are bound by a significant number of legislative instruments (see, for example, Dollery et al. 2009 for a discussion). Each state and the Northern Territory has a principal local government act; all states except for Tasmania also have a separate capital city act; and Queensland and South Australia have separate electoral acts. South Australia also has a finance authority act – the Local Government Finance Authority Act 1983 (SA). These acts have numerous accompanying regulations for planning, the environment, building, health and many other areas. For instance, one Victorian Government web page (n.d.) states that Victorian councils have responsibilities under 126 different acts and regulations.

When legislating for local government, state and territory governments originally set the rules of operation by detailing what local governments could and could not do and, in many cases, exactly how they must do it. Therefore, these statutes were largely prescriptive (Marshall 1998) and followed the ultra vires doctrine, under which local governments were not permitted to act ‘beyond powers’; the exception being Queensland, which as early as the late 1920s granted powers of general competence (see Grant and Drew 2017). Aulich (2005, 2009) emphasises how the local government reforms of the 1990s and their consequent legislative changes saw a move away from the ultra vires doctrine to the current situation, in which local governments are empowered to undertake any activities they deem necessary to fulfil their role.

Without empirical evidence, it is difficult to know why Australian states and the Northern Territory have generally increased their requirements for local governments to engage their communities, or their reasons for taking a particular approach. Presumably it is a combination of factors, including the reasons outlined in this article’s introduction. However, there are several likely political reasons: to offset concerns that reforms to local government have been driven by economic imperatives (Marshall et al. 1999); to compensate for the diminished representation that has resulted from amalgamations (Marshall and Sproats 2000; Grant and Drew 2017); and to ensure local governments are accountable and responsive to their local communities (Aulich 1999) – which presumably eases the burden for the state government (Hawker Report 2003). Whatever the exact motivators, state and territory governments have made a commitment to ensure their local governments are engaging their communities. In doing so, they have taken a combination of different approaches, which this discussion has sorted into a typology.

The typology assists with analysis as it allows both for legislative approaches to be compared across jurisdictions and time, and for possible future impact measurement (see Collier et al. 2008, 2012; Kluge 2000). The types are defined by two categorical variables: to what degree the engagement methodology is stipulated in the legislation; and whether or not the point in time, or juncture, at which community engagement must be conducted is stipulated in the legislation. As shown in Table 1, this results in four common approaches by the states and territory for legislating local government community engagement. First is the aspirational type, where neither the methodology nor the juncture is stipulated in legislation. This approach is a normative declaration of why participation by the community is valued and is presented in the principles, purpose or intent of the act. Second is the prescriptive type, where the methodology and the juncture are clearly articulated in the legislation. Third is the empowering type, where the legislation stipulates the juncture when engagement must be undertaken but it does not specify a methodology for how the engagement is to be done. Fourth and last is the hedging type, which stipulates the juncture and partially stipulates the methodology. It does this by stating that the local government can choose how it engages but that certain activities must be undertaken. This type is ultimately a combination of the prescriptive and empowering types.

While the different approaches do not follow a linear progression through the developmental stages of the legislative approaches or time periods, trends can be seen. These will be highlighted throughout the paper.

The development of Australia’s local government community engagement legislation

Pre 1980s: from establishing authorities to establishing democracies

The historical origins of Australian local government are contested, with opposing views that local government either emerged as a response to local demand, or was the result of legislation from the colonial governments (Grant and Drew 2017; Power et al. 1981). This constitutionalist versus state-interventionist contestation, labelled ‘the history wars’ by Grant and Drew (2017, p. 15), highlights an ongoing issue within Australian local government: namely, whether it is a creature of state or a form of self-government – with the latter cited as the origin of community engagement in local government. These duelling narratives persist to the current day and affect the understanding and practice of community engagement in local government (Grant and Drew 2017). Yet for the purposes of mapping the development of public consultation and engagement requirements in Australian local governments from a legislative perspective, the journey begins in the early part of the twentieth century.

At the time of the first comprehensive local government acts in each jurisdiction, the statutes focused on services to land, even though after the world wars many local governments had increased their welfare and cultural offerings – such as childcare and recreational facilities – in response to greater community expectations and needs (Kelly 2011, p. 7). The long-standing local government acts of the Australian states were the Local Government Act 1919 (NSW), the Local Government Act 1934 (SA), the Local Government Act 1936 (Qld), the Local Government Act 1962 (Tas), the Local Government Act 1958 (Vic) and the Local Government Act 1960 (WA). Although there were multiple amendments to these large legislative instruments from the time of their enactment (see, for example, Grant and Drew 2017, pp. 15–79 for a discussion) they nevertheless stayed in place for many years (74 years in NSW, 65 in SA, 57 in Qld, 31 in Tas, 31 in Vic and 35 in WA). All these acts included stipulations that announcements and public notices were to be made at various junctures, by way of gazette and newspaper. However, they did not specify methods whereby citizens could be involved in local democracy in the sense denoted by the modern nomenclature of ‘community engagement’ described above. Nor were any of the regular amendments to these acts specifically concerned with community participation.

Three events took place in the 1970s which ultimately facilitated the inclusion of participatory requirements in later legislation. First was the increase in Commonwealth grants to local governments instituted during the Whitlam federal government, which allowed local governments to increase or introduce their social, recreational and educational services (Marshall et al. 1999; Reddel 2005). These programmes and services raised the importance and profile of local government, as well as strengthening the federal–local intergovernmental relationship.

Second was the passing of the Northern Territory (Self-Government) Act 1978 (Commonwealth), a statute that serves as a constitution, and which saw the Commonwealth grant the territory self-government. This statute was important not only because it meant the new Northern Territory parliament took on most of the responsibilities (although not the de jure status) of a state, including local government, but also because it led to the new parliament passing the Local Government Act 1978 (NT). While the Act was concerned primarily with the creation and administration of community government councils and a provision for Aboriginal communities to manage local affairs, it also provided the opportunity for “any person to make a submission … in relation to a draft community government scheme” (s.433) and stipulated that “the Minister shall cause consultation to be carried out with residents” (s.434). While this directive did not specifically instruct local governments to engage, it was the first to reference engagement.

The third event was a period of reforms arising from the citizen-led social and environmental justice movements of the 1960s. With the combination of “grassroots participation and the discovering of the urban problem” (Halligan and Wettenhall 1989, p. 80), reforms “focused on democratising local government [ie from a property-owning to a broader franchise] and making it more responsive to the communities it served” (Aulich 2005, p. 198). An example and effect of this was the increase in disputes between councils and communities over environmental and development matters (Kelly 2011) which resulted in the New South Wales Wran Labor Government passing the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 (NSW), the first dedicated land use statute in Australia. The objects of the Act include the declaration that it is “to provide increased opportunity for public involvement and participation in environmental planning and assessment” (s.5). The provisions for facilitating this centre on public submissions, where the community are invited to put forward in writing their objections or support for a proposal, to then be considered by decision-makers.

Arguably, these three events set the tone not only for the direction of local government, but also for how state and territory governments have legislated community engagement at the local level ever since.

Late 1980s through to mid-2000s: the first wave of reforms and a burgeoning role for communities

In the 1980s and early 1990s substantial reviews were conducted of all the local government acts. Theories on the reasons for these wide-ranging reforms include “introducing or widening transparent and open procedures for decision-making to better inform local communities about council action and decisions, and generally encouraging community participation” (Wensing 1997, p. 96) through to the less altruistic “economic concerns [which have been] offset to a considerable degree by a commitment to community involvement” (Marshall et al. 1999, p. 36). Regardless of the driving forces, the late 1980s and 1990s was a pivotal time for legislated community engagement. First, the Cain Labor government in Victoria passed the Local Government Act 1989 (Vic). This was two years after the Planning and Environment Act 1987 (Vic) identified “appropriate public participation in decision-making” for amending planning schemes (s.4). Both acts are still current and in force in Victoria, although they have been amended multiple times. While the Local Government Act 1989 (Vic) did not incorporate any mention of community consultation and engagement as a principle of the Act, it did incorporate what was intended to be a standardised “process for several types of decision” (DELWP Vic 2015a, p. 12): the prescriptive ‘Section 223’. Section 223 outlines a standardised public submission process: public notice in a newspaper; a specific window of time in which submissions are to be advertised and received; the right for submitters to appear in person at a meeting to speak in support of their submission; and the obligation for the committee or council to inform submitters of the outcome by writing. While it is claimed that the Local Government Act 1989 (Vic) was designed to be constitutional and empowering for individuals rather than an inflexible blanket local government statute (DELWP Vic 2015a), Section 223 of the Act in effect contradicts that approach, by stipulating what to engage on, and prescribing how to undertake the engagement. Prior to any amendments, the original Act listed the use of the Section 223 process in 14 different sections, related to: council powers and boundaries (ss.98, 206, 220), creation of local laws (s.119), loan projects (s.147), land valuations and ratings (ss.157, 182, 183), council property (ss.189, 222, 192), regional corporations (s.196), and drainage (ss.199, 200). Over the years small changes have been made to Section 223, such as increasing the submission period and tidying up minor administrative matters; however, the process itself has remained relatively unchanged.

Several years later, in 1992 in South Australia, the Local Government (Miscellaneous Provisions) Amendment Act 1992 (SA) amended s.197 of the Local Government Act 1934 (SA) and required that councils give notice and invite written submissions on major projects and major spending of councils. It was the first prescriptive requirement from the state and was introduced by the Arnold Labor administration, which was in power for three months after the resignation of Premier John Bannon. Despite this initial step, the state was one of the last to pass a revised local government act during this reform period.

A significant year for local government statutes in Australia was 1993, with New South Wales, Queensland, Tasmania and the Northern Territory all passing new local government acts – as we have seen, the first for many decades in all these jurisdictions. In New South Wales, the Fahey Liberal government introduced the Local Government Act 1993 (NSW) which, in its second chapter, made the aspirational declaration that one of the purposes of the Act was “to encourage and assist the effective participation of local communities in the affairs of local government” (s.7). The introduction to Chapter 4 of the Act, titled ‘How can the community influence what a council does?’ includes the prescriptive “making submissions, including comments on or objections to proposals” as an answer. At the time the Act was passed, councils were required to give public notice and invite and consider submissions in instances of land reclassification (ss.32, 34), draft plans of management (ss.38, 40), leases, licences and other estates in respect of community land (s.47), building approvals (s.105), local policies (ss.160, 161), policies concerning expenses and facilities (s.253), draft codes of meeting practice (ss.361, 362), and financial and auditor reports (s.420). Since the Act was passed some of these requirements have remained unchanged, some have been slightly updated, and the requirements around building approvals have been moved into another statute.

In Tasmania, the newly elected Groom Liberal government passed the Local Government Act 1993 (Tas). The Act listed “develop, implement and monitor procedures for effective consultation between the council and the community” as a way a council could discharge its functions (s.20). This was the first instance of an empowering approach to legislating community engagement, where engagement is required but a specific method is not required, allowing a local government to design and deliver the engagement as it sees fit. The Act also included providing “a statement of procedures to be carried out in relation to consultation with the community” when developing a strategic plan (s.67). This made Tasmania the first state to mandate engagement on strategic plans. A right to make submissions concerning proposed by-laws (s.159) was also included when the Act was passed. Over time minor changes were made to the wording of those clauses and additional requirements for engagement in relation to by-laws were added (ss.156A, 164, 170A and 170B), as well as requirements to provide the opportunity for public consultation on review procedures (ss.214C, 214J). In contrast to Victoria, New South Wales and Queensland, where a new planning act preceded a new local government act, in Tasmania the Land Use Planning and Approvals Act 1993 (Tas) was passed the same year. Unlike other states, where land use planning is often a complementary or, in some cases, more forceful instrument for embedding community engagement practices into local government, in Tasmania the planning act at that time was focused on public exhibition requirements rather than consultation or engagement.

Commensurate with these changes, in Queensland local government reforms were conducted following two related events. First was the Fitzgerald Inquiry (1987–1989), a Royal Commission inquiring into police misconduct which resulted in a number of high-profile police and politicians, including Premier Bjeilke-Petersen, being charged and convicted for perjury. This inquiry led to the downfall of the National Party after a 32-year reign. Second, the Goss Labor government elected in 1989 oversaw the passing of the Local Government Act 1993 (Qld) three years after the Local Government (Planning and Environment) Act 1990 (Qld), which excised planning matters from the Local Government Act 1936 (Qld) and transferred them into a dedicated statute. The Local Government Act 1993 (Qld) signalled the beginning of the state placing explicit statutory obligations on local governments to consult with their communities. One of the Act’s aspirational objects was “providing for community participation in the local government system” (s.3) and dictated that local governments “must consult with the public” by way of prescriptive public submissions when making local laws (ss.476–478) and local law policies (ss.485–487). There were no other requirements to consult in the Act.

At the same time, in the Northern Territory the Country Liberal Party was re-elected to lead the Legislative Assembly in 1974. Consequently, the Local Government Act 1993 (NT) reflected this conservative context and the Act focused more on administrative matters than on community engagement. However, the Act did include two requirements to consult: rate charges (s.70), with public submissions prescribed; and draft constitutions for community governments (s.104), with no method prescribed beyond the stipulation that “the minister shall consult with the residents”, an empowering approach.

From the tracing of these developments of 1989 to 1993, the differences between the ‘creatures of state’ become clearer, along with their appetites for participatory approaches to democracy.

In 1995 in Western Australia the Liberal Court administration introduced the Local Government Act 1995 (WA). The Act declared an aspirational commitment to community engagement as it explicitly aimed for “greater community participation in the decisions and affairs of local governments” (s.1.3(2)(c)). As with the acts from the other states, prescriptive public submissions were the participatory method of choice and applied to making local laws (s.3.12), closing thoroughfares to vehicles (s3.50), notification of proposals (s.3.51), property disposal (s.3.58), commercial enterprises by local government (s3.59c), rates (s.6.36), boundary inquiries (Sch. 2.1 cl.4) and ward changes and reviews (Sch. 2.2 cls.3, 4, 7). However, the Local Government (Administration) Regulations 1996 (WA), released the following year, had no relevant community engagement requirements when passed.

While South Australia did not reform its local government legislation in 1993, it did pass the Development Act 1993 (SA). The Act was not prescriptive in how to engage, but made several references to ‘public consultation’.1 In 1995, the Local Government (Boundary Reform) Amendment Act 1995 (SA) amended the Local Government Act 1934 (SA) with a number of provisions designed to facilitate the upcoming voluntary council amalgamations of 1997 and 1998 undertaken during the Olsen Liberal administration. One of these stipulated that a public submission and hearing process be incorporated into reform proposals (s.21). Upon completion of the voluntary amalgamations, the number of councils was reduced by 57% and the Local Government Act 1934 (SA) was completely revised. The new Local Government Act 1999 (SA) listed the aspiration of “participation by local communities in the affairs of local government” in its principles (s.3), and implicitly defined the role of a council as “represent[ing] the interests of its community” (s.6).

It was at this point that South Australia’s approach to legislating community engagement diverged from the other states and took a multi-pronged turn. The new Act required a consultation process for the development of strategic management plans (s.122), and it also required local governments to “prepare and adopt a public consultation policy” (s.50). Interestingly, the Act stipulated that any revisions to these policies must be undertaken via a prescriptive public submission process. The Act also specified the junctures at which the public consultation policy was to be followed: reclassification of land (ss.193, 194), land management plans (ss.197, 198), lease of community/council land (s.202), council meeting code (s.92), permits for using roads and footpaths for business purposes (s.223), and planting trees (s.232). By developing and then applying a policy, the South Australian Government was granting local governments more, although not full, independence in engaging their communities, thus demonstrating an empowering approach. Two elements of the Act required a ‘reasonable amount’ of public consultation: reform proposals (s.27) and major projects (s.48); another example of an empowering approach. In parallel, however, the Act required the familiar prescriptive public submissions in instances of public reform proposal (s.28) and ward composition (s.12). Finally, the Act contained one instance of “should consult” – for office locations and hours (s.45). This is the only example of a local government act merely suggesting community engagement at a juncture. Two years after the Act was passed, the Local Government (Consultation on Rating Policies) Amendment Act 2001 (SA) added another approach, with its requirements on community consultation for rates policy and variations (ss.151 and 156). The amendment act stipulated that councils were to follow their public consultation policies and that the policy must provide for a public submission process. This was the first time a state government had used the hedging approach, where a degree of independence was granted yet a minimum requirement was put in place. This ultimately sent a mixed message about how much trust the state has in its local governments.

The 1990s ended with the newly elected Labor Bracks administration passing the Local Government (Best Value Principles) Act 1999 (Vic) which stipulated that “a Council must develop a program of regular consultation with its community in relation to the services it provides” (s.208B). This amendment finally aligned Victoria with the other states, save Tasmania, by including an aspirational declaration of the intent and principles of the Act and the role of community engagement. A few years later, the same administration passed the Local Government (Democratic Reform) Act 2003 (Vic), concerned with reforming electoral processes and improving accountability and transparency. The Act required councils to produce council plans (s.125) and council budgets (s.129) that are subject to the prescriptive Section 223 public submission processes outlined above. The tightening of the requirements for a strategic council plan, and the inclusion of public consultation requirements, are similar conditions to those introduced by Tasmania in 1993 and South Australia in 1999. However, Victoria was the first state to introduce the requirement to consult on council budgets, albeit with the use of public submission processes.

Western Australia followed suit, with the Gallop Labor ministry making some changes to the Local Government Act 1995 (WA) in 2004. At the time the changes appeared quite small, such as the inclusion of Section 5.56, ‘Planning for the future’, which dictated that local governments were to plan for the future “in accordance with any regulations”. However, the following year, the Local Government (Administration) Regulations 1996 (WA) were updated considerably, introducing the requirement for strategic community plans, following South Australia and Tasmania’s examples. The two-year plans were to “set out the broad objectives of the local government” and “must ensure that the electors and ratepayers of its district are consulted during the development” (r.19D). Proof of this consultation was also required, but a process or method was not prescribed, demonstrating an empowering approach. That same year South Australia added a community consultation requirement for annual business plans and budgets (s.123), introduced with the passing of the Local Government (Financial Management and Rating) Amendment Act 2005 (SA). Like the rates amendment passed a few years earlier, the consultation requirement was to follow the public consultation policy but to also ensure a public submission process was included, once again utilising the hedging approach.

Also in 2005, the Tasmanian Labor government under David Bartlett passed the Local Government Amendment Act 2005 (Tas) which revised the functions and powers of councils to include the duty that “in performing its functions, a council is to consult, involve and be accountable to the community” (s.20) – thus bringing Tasmania into line with all other states by including an aspirational approach.

Mid-2000s to mid-2010s: the era of strategies, frameworks and reporting requirements

By 2005, community strategic plans and the community engagement processes that came with them were required in Tasmania, South Australia and Western Australia, with Victoria looking set to follow (see Grant et al. 2011). The 2005 Victorian state government initiative, A Fairer Victoria (DPC Vic 2005), was aimed at addressing disadvantage and listed community engagement as a key strategy. A year later, Strong Communities: Ways Forward was released by the Ministerial Advisory Committee for Victorian Communities (MACVC). This document presented several community planning and engagement recommendations, noted that community planning was being practised in more than half of Victoria’s local governments (MACVC 2006, p. 125), and stated that the importance of community plans should be further emphasised by the state government. Also in 2006, the Victorian Community Indicators Project released its final report aimed at “strengthening local government planning and local democracy” (VCIP 2006, p. 4) through the use of community well-being indicators. In mid-2007, Labor Premier Steve Bracks retired and was replaced by John Brumby. Perhaps because of this change, the mechanism to make community plans compulsory was revised. In 2007, the state government document Planning Together: Lessons from local government community planning in Victoria concluded that community planning approaches should be encouraged within council plans rather than in a plan of their own (West and Raysmith 2008).

Further to this, the Planning and Environment Act 1987 (Vic) amendment in 1996 requires councils to produce Municipal Strategic Statements (MSS) (s.12A). An MSS is a statement of the council’s strategic land use planning objectives for the municipality. Since 2007, the Act has stipulated that the MSS be consistent with council plans, therefore implying a requirement for community engagement without expressly declaring it. In May 2008 a practitioner body with financial support from the state government, the Local Government Professionals Corporate Planning Network (LG Pro), released Embedding Community Priorities into Council Planning: Guidelines for the Integration of Community and Council Planning. This document sought to bridge the gaps identified in the earlier Planning Together report by providing guidance and frameworks on community planning in Victorian local government. Later that year, the Public Health and Wellbeing Act 2008 (Vic) was passed, which put a requirement on local governments to also produce Municipal Public Health and Wellbeing Plans (MPHWPs). The plans were intended to set goals and priorities for community members to achieve maximum health and well-being. Section 26 of the Act states that it “must provide for the involvement of people in the local community in the development, implementation and evaluation of the … plan”. The addition of MPHWPs to MSSs and council plans has been interpreted as the final piece of the planning framework in Victoria. However, these frameworks vary between councils, with many choosing to develop community plans which they position above all other plans in their own strategic planning frameworks.

Strategic community plans gained a mention in the Northern Territory’s new local government statute, the Local Government Act 2008 (NT); however, they were not required to be implemented. The new Act was passed following the local government reforms of the Henderson Labor Chief Ministership, which saw 51 of the 55 community government councils amalgamated into eight shire councils that cover extraordinarily large geographical areas. The Act included in its preamble the aspirational statement that the legislation was designed to “promote and assist constructive participation by their local communities”. The Act also called for “municipal, regional or shire plans” (s.23), which were to include service delivery plans and budgets, as well as to contain or reference long-term community or strategic plans and long-term financial plans. The Act does not expressly require councils to consult or engage communities in the development of these plans, nor does it expressly require a long-term community or strategic plan. It does, however, require a prescriptive public submission process upon annual review of the plans (s.24).

The trend for councils to develop strategic community plans continued in subsequent years, and was joined by the financial sustainability and performance reporting wave – which would also have consequences for the community engagement requirements placed on councils.

In 2006 the Australian Local Government Association (ALGA) commissioned the National Financial Sustainability Study of Local Government report (PricewaterhouseCoopers 2006). This report highlighted issues relating to the financial sustainability of the sector and gained the attention of the Local Government and Planning Ministers Council (LGPMC).2 Consequently, the LGPMC decided to develop a series of national sustainability frameworks that the states agreed to adopt. These frameworks have been the impetus for the incorporation of long-term financial and asset management plans in councils across Australia. The first state to update its legislation to incorporate the standards outlined in the frameworks was New South Wales. The passing of the Local Government Amendment (Planning and Reporting) Act 2009 (NSW) saw updates to the Local Government Act 1993 (NSW) beyond the minor amendments to public consultation requirements that had so far occurred since the Act came into force. Receiving its assent under the short-lived Rees Labor ministry, the amendment focused on introducing a strategic planning framework to ensure good governance. Relevant to community engagement was the aspirational charter, which was expanded to include a directive that councils exercise their “functions in a manner that is consistent with and promotes social justice principles of equity, access, participation and rights” (s.8). The introduction to Chapter 4, on how communities can influence councils, was updated to include “by participating in council community engagement activities” – thus broadening the interpretation of participation to methods beyond public submissions and empowering councils to set their own engagement programmes. Community strategic plans formed the cornerstone of the new integrated planning framework outlined in the amendment, and came with the requirement that a community engagement strategy must accompany development of the plans (s.402). The Act also called for a public submission process: the same hedging approach as that used in South Australia. A public submission process was also extended to requirements for the updated delivery programme (s.404) and operation plan (s.405). A proviso that the integrated planning and reporting guidelines must be adhered to (s.406) followed four years later under the O’Farrell Liberal government (DLG NSW 2013). The guidelines provide greater detail on the framework and the requirements placed on councils, along with a considerable focus on community engagement.

In the same year, the Queensland Bligh Labor government passed the new Local Government Act 2009 (Qld), repealing the existing Act after a relatively short 16 years. The new Act identified “democratic representation, social inclusion and meaningful community engagement” (s.4) as one of five aspirational underpinning principles for local government. Following South Australia, Tasmania and Western Australia, Queensland also incorporated the requirement for local governments to develop a long-term community plan that “outlines the local government’s goals, strategies and policies for implementing the local government’s vision for the future of the local government area, during the period covered by the plan” (s.104). Surprisingly, there were no express requirements for community engagement in the development of the “local government’s vision”. The Act also had extensive detail on the requirements of the community forums to be used in the state’s indigenous local governments (ss.82–89).

Local government continued in the spotlight in Australia in 2009, with the Western Australian Barnett Liberal government releasing the Integrated Planning and Reporting (IPR) Framework and Guidelines (DLG WA 2010). The guidelines were developed after disappointing results from a 2009 reform programme aimed at increasing the level of strategic planning occurring in local governments in Western Australia (DLG WA 2010, p. 4). The framework referenced and built upon several other documents: the Local Government Sustainability Framework from the LGPMC; the NSW Planning and Reporting Framework outlined in the 2009 amendment to NSW’s 1993 Act; the Queensland planning and accountability documents outlined in that state’s 2009 Act; and the New Zealand planning and reporting requirements outlined in its 2002 Local Government Act. The Western Australian guidelines made community engagement the centrepiece, with the document providing considerable detail on how to design a tailored engagement process, thus taking an empowering approach rather than the now near-ubiquitous public submission process.

Just three years after the passing of Queensland’s Local Government Act 2009 (Qld), sections of the Act were repealed or amended, resulting in a reduction in community engagement requirements: a first for any of the states. After 23 years in power the Queensland Labor Party was defeated in the 2012 election, losing 44 of its 51 seats to the Liberal National Party (LNP) led by Brisbane’s former Lord Mayor, Campbell Newman. The LNP government claimed an “electoral mandate to implement its announced policy commitments” including the ‘Empowering Queensland Local Government’ election policy (Queensland Government 2012, p. 24). The resulting Local Government and Other Legislation Amendment Bill 2012 (Qld) saw two main changes to the Local Government Act 2009 (Qld) with respect to community engagement. First, the requirement for long-term community plans was repealed, with the explanatory notes describing the original requirement as “unnecessary red tape” and stating that the repeal was designed to allow “local governments to plan for the community in the way they know best” (Queensland Government 2012, p. 4). The requirement was changed to “a 5-year corporate plan that incorporates community engagement” (s.104). While this change moved Queensland away from the long-term community plan trend, it does include an example of an empowering approach to engagement. Second, the Bill clarified that public consultation was not required before making a local law (s.29), presumably in response to the confusion that had followed the 1993 Act, which included considerable requirements for public consultation in the creation of local laws and local law policy. After just one term in office, Newman’s LNP government was defeated in the February 2015 state election, returning Labor to power, albeit with a majority dependent on the support of independents. The Labor government led by Annastacia Palaszczuk has since made some minor amendments to Local Government Act 2009 (Qld), but none of these changes have concerned any of the previously repealed engagement requirements.

The introduction of the Local Government (Planning and Reporting) Regulations 2014 (Vic) saw Victoria align with the planning and reporting approaches that emerged from the LGPMC frameworks and complemented the work the state had commenced in this arena in previous years. In 2008, the Victorian Auditor-General’s Office (VAGO) undertook an audit of performance reporting in local government which led to the state’s Essential Services Commission (ESC) developing a performance monitoring framework for local government service delivery (DPCD Vic 2012). This work, and further work by VAGO, resulted in the introduction of planning and reporting regulations which, along with the accompanying Better Practice Guide 2014–2015: Performance Reporting Framework Indicator Workbook (DTPLI Vic 2014), prominently feature community engagement. The regulations require councils to report on the status of their community engagement policy as well as community engagement guidelines “to assist staff to determine when and how to engage with the community” (Sch. 1). They also incorporate the reporting of community satisfaction scores on the “consultation and engagement efforts of council” (Sch. 2). The scores from this rating and others from the framework are available online so that citizens can compare the performance of Victorian councils. While the regulations do not specifically require community engagement policies and guidelines, they do communicate to Victorian local governments that community engagement is a state priority, and which documents are expected to be in place to facilitate this. The regulations and guidelines were followed in January 2015 by VAGO’s release of the Public Participation in Government Decision-making Better Practice Guide. Aimed at state and local governments, the guide provides a framework and principles aimed at improving practice, given the focus on community engagement in performance audits going forward (VAGO 2015, p. 1). This framework was used by VAGO to conduct audits of six Victorian councils. The recommendations arising from these audits, aimed at all Victorian councils, were: the need to assess policies and resources against the International Association for Public Participation model; that reporting and evaluation activities be incorporated into activities; and that comprehensive plans and outcomes be recorded (VAGO 2017, p. xii). These regulations and guides thus represented a change of direction for the state, in enhancing the community engagement practices of local governments beyond the prescriptive Section 223 public submission processes.

Mid-2010s to today: more reforms and changing landscapes as the wheel spins faster

The local government acts of the states stayed in place for an average of 48 years during the twentieth century; however, in the twenty-first century the landscape has become peppered with reforms, as well as new approaches to local democracy and local government community engagement practices. In South Australia, experiments in democracy continued against the backdrop of a long history of partnership between the state and local governments, fostered by a series of agreements dating from 1990, 1994, 2004 and 2011. The ‘Better Together’ programme, led by 2011 elected Labor Premier Jay Weatherill, sought to improve the state government’s engagement practices with local government. The ‘Reforming Democracy’ strategy (South Australian Government 2015) set the bold vision of making the state a leader in democratic reform. In March 2018, South Australia elected Liberal Premier Steven Marshall and while there is evidence that the ‘Better Together’ programme will continue, it is unclear if the government intends to make changes.

In 2013 the O’Farrell Liberal New South Wales Government attempted an update of its planning legislation from 1979 with the release of a White Paper (NSW Government 2013a) on planning reform and the introduction of the Planning Bill 2013 (NSW). The Bill, like many planning statutes made considerable mention of “community participation” however the Bill failed to pass and is considered lapsed. Meanwhile in Queensland, the state turned its focus to planning matters with the passing of Planning Act 2016 (Qld). The Act and its associated instruments, such as Planning Regulation 2017 (Qld), now require planning legislation to include public consultation by local governments in a way that is aspirational and prescriptive, although not overly extensive.

In Victoria, the Andrews Labor government commenced a review of the Local Government Act 1989 (Vic), and released a discussion paper (DELWP Vic 2015b) and response (DELWP Vic 2016). The discussion paper cites “frustration about levels of engagement with communities by councils about key decisions” (2015b, p. 15) as an area to be addressed, and notes that approaches to consultation are inconsistent across the sector and that councils face criticism and leave themselves open to legal challenges to their decisions when they do not engage adequately (DELWP Vic 2015b, p. 52). The response paper, or ‘reform directions’ paper preceding consultation made strong reference to councils needing to use deliberative community engagement.3 This is an interesting development, as deliberative community engagement methods are a group of engagement methods based on the theory of deliberative democracy and are generally considered to be more resource intensive than traditional engagement methods. Deliberative community engagement has been omitted in the Local Government Bill Exposure Draft 2018 (Vic), presumably in response to feedback from councils. The Bill includes five aspirational community engagement principles. These principles are more substantial than those previously seen in the acts, which typically outlined the importance of engagement. The principles in the Bill specifically address how the engagement should be supported and enabled and include: the need for a clearly defined objective and scope; the need for timely information for participants; the need for participants to be representative of those affected; the right for participants to have support to enable participation; and the need for participants to be informed of how their participation influenced the decision. The bill is ultimately empowering in its approach as it calls for a community engagement policy to be developed and followed, without many exact stipulations of when this should be. At the time of publication, the Bill was waiting to be passed by the newly re-elected Andrews government.

The other states are also dealing with amalgamations and reforms, or the fall out of these, the most topical at the time of publication being those in New South Wales, led by the Liberal government.4 With the failure of the Planning Bill 2013 (NSW), the Environmental Planning and Assessment Amendment Act 2017 (NSW) was passed which has seen the 1979 Act overhauled considerably. The act now requires planning authorities, inclusive of local governments, to produce Community Participation Plans (CPPs). CPPs are to outline when and how authorities will engage on their various planning functions. They include minimum requirements inclusive of public displays and submissions, making them an example of a hedging approach.

In Tasmania in 2014, the Labor government of 16 years was ousted and Liberal Premier, Will Hodgman was elected. He made early mention of inviting councils to consider amalgamations and resource-sharing. In 2016 a media release from the Department of Premier and Cabinet, Tasmania (2016a) declared a “targeted review of the Local Government Act 1993” in response to “current community concern over how some councils are managing their affairs”. A discussion paper was released (Tasmanian Government 2016b), followed by a consultation feedback report (Tasmanian Government 2016c). Ultimately, a new act was not developed and in its place was the Local Government Amendment (Targeted Review) Act 2017. Despite the mention of community engagement in the discussion paper and consultation feedback report, however, there is no reference to it in the Amendment Act. The Hodgman government was re-elected in March 2018 and in June of that year, it was announced, once again, that a review of the Local Government Act 1993 would be undertaken. At the time of publication, a terms of reference had been confirmed and discussion paper imminent.

In Western Australia, the reform programme commenced in 2009 was put on hold by the Barnett government in 2015, presumably in response to the negative reception of the 2014 announcement to reduce the number of Perth councils from 30 to 16 (O’Connor 2015). The Labor McGowan government elected in March 2017 announced a review of the Local Government Act 1995 (WA) and at the time of publication consultation had commenced by way of discussion papers and surveys around nine key reform areas, including community engagement. Regardless of the changeable climate for local governments in all states and the Northern Territory, it can be said that community engagement is an increasingly key feature of the legislation, even though the approaches to it vary.

Comparative observations and discussion

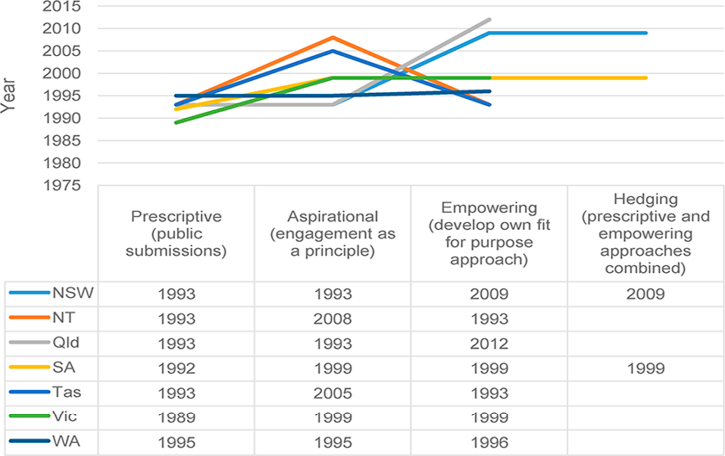

The foregoing account of the development of community engagement legislation leads to a number of observations. First is the overall trajectory of the local government acts. As a general rule, each of the states and the Northern Territory have followed the same four main developmental stages which align with the typology presented and are summarised in Figure 2. The first stage saw the introduction of prescriptive public submission requirements, with all states incorporating this requirement between 1989 and 1999. The second stage was the introduction of aspirational declarations of community engagement as a key principle, either in the preamble, purpose, intent or principles of the acts. These declarations were made in all the acts between 1993 and 1999. The third empowering stage allowed for local governments to choose their own methodologies, through development of their own engagement programmes or the following of their own engagement policies. Tasmania and the Northern Territory were the first in this regard in 1993 and South Australia and Victoria followed in 1999, although Victoria’s stipulation exists in the regulation, rather than the Act. New South Wales and Queensland followed in 2009 and Western Australia in 2011. The most recent approach, which has thus far only emerged in South Australia and New South Wales is the hedging approach, where state governments have stipulated a specific methodology (prescriptive) to be used in combination with a non-stipulated methodology (empowering): an approach which seems indicative of trying to ensure state-wide standards while at the same time attempting to give local governments autonomy.

Figure 2 Developmental stages in Australian Local Government Acts as pertaining to community engagement

Source: Local Government Acts

The use of regulations and guidelines rather than parliamentary acts highlights another important observation: that of the preferred legislative instrument. The passing of parliamentary acts is an involved and lengthy process in all states and, while the process of passing subordinate legislation such as regulations and guidelines does vary, it is a faster and simpler one where amendments can often be made by the executive branch rather than by parliament. The author does not draw any inferences from this practice, but simply notes that it provides a potential pathway for policy-makers to effect quicker and more responsive adjustments – in all policy areas, not just community engagement.

In the same vein, it would appear that planning legislation often serves as the catalyst for legislating greater involvement of communities in local decision-making. In several states planning legislation and its engagement requirements preceded the local government acts. This was first seen in New South Wales, with its Environment and Planning Assessment Act 1979 (NSW), which featured the first occurrence of public submission requirements. Other examples include the Planning and Environment Act 1987 (Vic), which introduced engagement requirements prior to the Local Government Act 1989 (Vic), and the Local Government (Planning and Environment) Act 1990 (Qld), which preceded the Local Government Act 1993 (Qld). Without further research it is difficult to ascertain whether the prioritisation of the community engagement requirements in planning legislation is the result of a more progressive, or merely a more political approach by land use policymakers; nevertheless, it is an important and relevant trend.

Issues and challenges

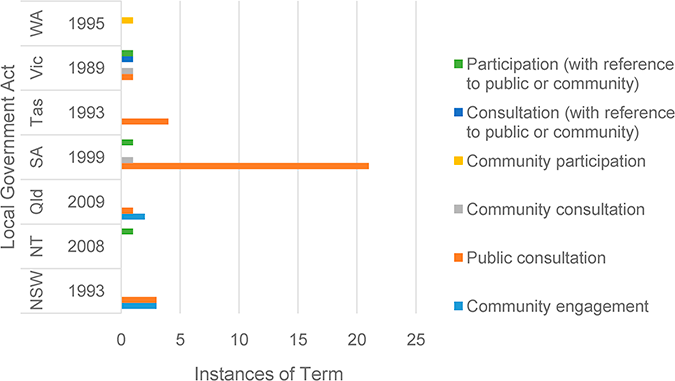

These comparisons provide an overview of how legislated community engagement has developed; they also raise a number of issues. The first is nomenclature and definitions. This paper has given preference to the term ‘community engagement’ due to its increasing use in the Australian local government sector; however, it is not reflective of the legislation, which presents a more complex picture. In the current versions of the local government acts, reference is made to ‘community engagement’, ‘public consultation’, ‘community consultation’, ‘community participation’, ‘consultation’ and ‘participation’.

Figure 3 Community engagement terminology in Australia’s Local Government Acts

Source: Local Government Acts

As Figure 3 illustrates, some jurisdictions, such as the Northern Territory, Tasmania and Western Australia, use one consistent term; the other states use two, three, or – in the case of Victoria – four. Some of this inconsistency is the result of amendments to the acts. For instance, in New South Wales, ‘community engagement’ has been used in recent amendments whereas ‘public consultation’ was used when the Local Government Act 1993 (NSW) was passed. The fact remains that none of the present, nor superseded acts have presented a definition for any of these terms. While it appears that the terms are used interchangeably, definitions and/or consistency would be of great assistance to those attempting to interpret the acts.

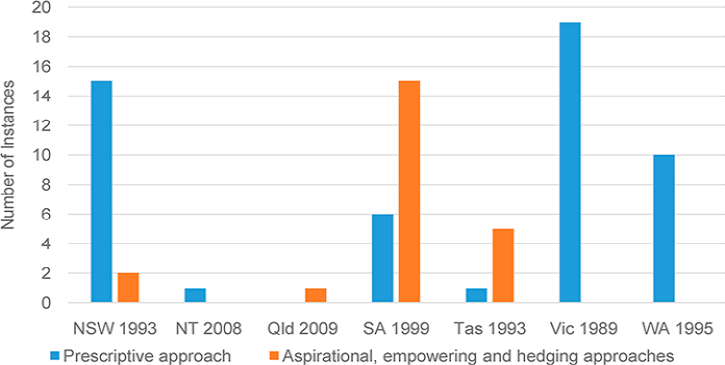

Figure 4 Public submission versus non-stipulated methods in core Australian Local Government Acts

Source: Local Government Acts

The second issue is the prevalence of prescriptive methods, in particular public submissions, in the current acts. Their use in the acts has grown and, as Figure 4 illustrates, has become so pervasive that they are the prescribed methods in just over two-thirds of all junctures that stipulate engagement be undertaken. This is of concern, as research shows that effective engagement is designed to meet a purpose, rather than being forced to conform to a methodology, and that to prescribe a methodology risks the integrity of the process and increases the likelihood of being tokenistic (Arnstein 1969; Cameron and Grant-Smith 2014; Cameron and Johnson 2006; Head 2007). In his discussion of public participation laws in the USA, Leighninger (2014) argues that outdated public participation laws, such as public meetings, perpetuate discord between communities and government and are examples of “small-minded participation”. Leighninger (2014) from the United States cites the resource ‘Making Public Participation Legal’ (Working Group on Legal Frameworks for Public Participation 2013) as an example of how to help public policymakers understand the limitations of prescriptive methods and develop alternative ideas to deliver more meaningful engagement. This argument is mirrored in the review by Bryson et al. (2013) of over 250 articles and books on the same topic. The review provides evidence-based guidelines for planning engagement processes that articulate the importance of assessing both contextual factors and the purpose of the engagement as necessary and precursory steps to identifying a suitable method for engagement. The alternative to these prescriptive methods is to utilise empowering approaches, which will not only improve the quality of engagement between local governments and their communities, but are also likely to improve the relationship between state and local governments.

Finally, it is also difficult to know exactly how the legislative requirements are being interpreted. Are councils taking them as minimum or maximum requirements? For example, are they undertaking just the prescribed requirement for public submission, or are they incorporating additional engagement activities in an attempt to provide a more robust and meaningful engagement opportunity? This is an area of enquiry which merits further study.

Conclusion

This paper has provided an overview of both historic and current legislative requirements for community engagement by local governments. The course of development originated with the stipulation of prescriptive public submissions, followed by a stage of making aspirational legislative statements. In more recent years there has been experimentation with both empowering approaches, in which councils are granted permission to design their own engagement strategies, and alternatively a more conservative hedging approach, where prescriptive and empowering approaches are combined. There has also been a broadening of the scope of community engagement, with the more recent requirements focusing on community strategic plans and, in some instances, budgets. Notably, however, the original prescriptive approach remains dominant in nearly half of states. Reflecting on this, questions remain: Which approach is the most effective? What will the future trajectory look like? The most likely answer to the first question is that it depends entirely on what the states are trying to achieve. As discussed earlier, the motivations of the states at their most virtuous can be to foster local democracy and ensure accountability, but at their least virtuous may be merely to ingratiate themselves with communities to lessen the perceived negative impacts of various reform programmes.

Legislating participatory democracy can and should be an opportunity for councils and communities. Currently, however, the opportunity in Australia is limited by a dominance of prescriptive and dated methods, which are often counter-productive of what is, assumedly, their original aim. As for what the future may hold, the hedging approach first used by South Australia and later adopted by New South Wales may continue to prove popular, as it is likely to be perceived as a way for the states to give some independence to local governments while maintaining a degree of control. It can also be expected that the aspirational overtones are likely to persist. The most interesting development, in the author’s view, will be to see whether state-level policymakers accept the growing body of evidence that purpose-driven (empowering) engagement is more effective than method-driven (prescriptive) engagement. It is hoped that the typology presented in this paper can assist with this decision.

References

Arnstein, S.R. (1969) A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35 (4), 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225

Aulich, C. (1999) From convergence to divergence: Reforming Australian local government. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 58 (2), 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.00101

Aulich, C. (2005) Australia: Still a tale of Cinderella? In: Denters, B. and Rose, L.E. (eds.) Comparing local governance: Trends and developments (pp. 193–210). Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-230-21242-8_12

Aulich, C. (2009) From citizen participation to participatory governance in Australian local government. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, 2, 44–60. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.v0i2.1007

Aulich, C. (2015) Recognising the local government sector. In: Dollery, B. and Tiley, I. (eds.) Perspectives on Australian local government reform (pp. 162–175). Sydney: Federation Press.

Aulich, C. and Pietsch, R. (2002) Left on the shelf: Local government and the Australian constitution. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 61 (4), 14–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.00296

Australian Government. (1978) Northern Territory (Self-Government) Act 1978. Available at: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_act/nta1978425/ [Accessed 16 October 2017].

Bell, S. and Hindmoor, A. (2009) Rethinking governance: The centrality of the state in modern society. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511814617

Bishop, P. and Davis, G. (2002) Mapping public participation in policy choices. Journal of Public Administration, 61 (1), 14–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.00255

Brackertz, N. (2013) Political actor or policy instrument? Governance challenges in Australian local government. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, (12), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.v12i0.3261

Bryson, J.M., Quick, K.S., Slotterback, C.S. and Crosby, B.C. (2013) Designing public participation processes. Public Administration Review, 73 (1), 23–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2012.02678.x

Cameron, J. and Grant-Smith, D. (2014) Putting people in planning: Participatory democracy, inclusion and power. In: Byrne, J., Sipe, N. and Dodson, J. (eds.) Australian environmental planning: Challenges & future prospects (pp. 197–205). Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

Cameron, J. and Johnson, A. (2006) Planning public involvement: A step-by-step guide. Urban Research Programme Practice & Policy Paper No. 1, Griffith University. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10072/12661 [Accessed 14 May 2018].

Collier, D., LaPorte, J. and Seawright, J. (2008) Typologies: Forming concepts and creating categorical variables. In: Box-Steffensmeier, J.M., Brady, H.E. and Collier, D. (eds.) Oxford handbook of political methodology (pp. 217–232). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Collier, D., LaPorte, J. and Seawright, J. (2012) Putting typologies to work: Concept formation, measurement, and analytic rigor. Political Research Quarterly, 65 (1), 217–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912912437162

Dallinger, D. (2009) Local government in the Australian Federation. (No. 07-2009) CLG Working Paper Series. Armidale, New England: UNE Centre for Local Government.

Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning Victoria (DELWP Vic). (2015a) Local Government Act review – background paper 2 History of 1989 Act. Available at: http://www.yourcouncilyourcommunity.vic.gov.au/16855/documents/35857 [Accessed 16 October 2017].

Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning Victoria (DELWP Vic). (2015b) Review of the Local Government Act 1989. East Melbourne: State of Victoria.

Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning Victoria (DELWP Vic). (2016) Act for the future: Direction for a new Local Government Act. Available at: http://www.yourcouncilyourcommunity.vic.gov.au/16888/documents/37297 [Accessed 12 October 2017].

Department of Local Government Western Australia (DLG WA). (2010) Integrated planning and reporting framework and guidelines. Available at: https://www.dlgsc.wa.gov.au/resources/publications/Publications/Integrated%20Planning%20and%20Reporting%20(IPR)%20-%20Framework%20and%20Guidelines%20-%20A%20Short%20Guide/IPR_StrategicPlanningFramework_ShortGuide.pdf [Accessed 25 November 2018].

Department of Planning and Community Development Victoria (DPCD Vic). (2012) Local government performance reporting framework: Directions paper. Available at: https://www.localgovernment.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0022/47551/Directions_Paper_-_Local_Government_Performance_Reporting_Framework_December_2012.pdf [Accessed 16 October 2017].

Department of Premier and Cabinet (DCP Vic). (2005) A fairer Victoria: Creating opportunity and addressing disadvantage. Melbourne: Department of Premier and Cabinet.

Department of Transport, Planning and Local Infrastructure, Victorian Government (DTPLI Vic). (2014) Local government better practice guide 2014–2015 performance reporting framework indicator workbook. Melbourne: Local Government Victoria.

Division of Local Government, Department of Premier and Cabinet NSW (DLG NSW). (2013) Integrated planning and reporting manual for local government in NSW: Planning a sustainable future. Available at: https://www.olg.nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/Intergrated-Planning-and-Reporting-Manual-March-2013.pdf [Accessed 16 October 2017].

Dollery, B., O’Keefe, S. and Crase, L. (2009) State oversight models for Australian local government. Economic Papers, 28 (4), 279–290. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-3441.2010.00047.x

Fung, A. (2015). Putting the public back into governance: The challenges of citizen participation and its future. Public Administration Review, 75 (4), 513–522. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12361

Grant, B., Dollery, B.E. and Kortt, M. (2011) Australian local government and community engagement: Are all our community engagement plans the same? Does it matter? (Working Paper Series 05-2011). Armidale, New England: Centre for Local Government, University of New England.

Grant, B., Dollery, B. and van der Westhuizen, G. (2012) Locally constructed regionalism: The City of Greater Geraldton, Western Australia. Public Policy, 7 (1), 79–96.

Grant, B. and Drew, J. (2017) Local government in Australia: History, theory and public policy. Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-3867-9

Grant, B., Ryan, R. and Kelly, A. (2016) The Australian Government’s ‘White Paper on reform of the federation’ and the future of Australian local government. International Journal of Public Administration, 39 (10), 707–717. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2015.1004088

Halligan, J. and Wettenhall, R. (1989) The evolution of local governments. In: The Australian local government handbook (pp. 77–87). Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service.

Hawker Report [House of Representatives Standing Committee on Economics Finance and Public Administration]. (2003) Rates and taxes: A fair share for responsible local government. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

Head, B.W. (2007) Community engagement: Participation on whose terms? Australian Journal of Political Science, 42 (3), 441–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/10361140701513570

Head, B.W. (2011) Australian experience: Civic engagement as symbol and substance. Public Administration and Development, 31 (2), 102–112. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.599

Herriman, J. (2011) Local government and community engagement in Australia. Working Paper No. 5, Sydney: Australian Centre of Excellence for Local Government, University of Technology Sydney.

International Association of Public Participation (IAP2). (n.d.) About IAP2 – International Association for Public Participation. Available at: http://www.iap2.org/?page=A3 [Accessed 16 October 2017].

Kelly, A.H. (2011) The development of local government in Australia, focusing on NSW: From road builder to planning agency to servant of the state government and developmentalism. Presented at the World Planning Schools Congress, Perth.

Kluge, S. (2000) Empirically grounded construction of types and typologies in qualitative social research. Forum, Qualitative Social Research, 1 (1). Available at: http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/1124/2499 [Accessed 12 May 2018].

Leighninger, M. (2014) Want to increase trust in government? Update our public participation laws. Public Administration Review, 74 (3), 305–306. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12208

Local Government Professionals Corporate Planning Network (LG Pro). (2008) Embedding community priorities into council planning. Guidelines for the integration of community and council planning. Available at: http://www.chs.ubc.ca/archives/files/Embedding-Community-Values-Council-Planning.pdf [Accessed 16 October 2017].

Marshall, N. (1998) Reforming Australian local government: Efficiency, consolidation – and the question of governance. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 64, 643–662. https://doi.org/10.1177/002085239806400407

Marshall, N. and Sproats, K. (2000) Using strategic management practices to promote participatory democracy in Australian local government. Urban Policy and Research, 18 (4), 495–514. https://doi.org/10.1080/08111140008727853

Marshall, N., Witherby, A. and Dollery, B. (1999) Management, markets and democracy: Australian local government reform in the 1990s. Local Government Studies, 25 (3), 34–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003939908433956

Ministerial Advisory Committee for Victorian Communities (MACVC). (2006) Strong communities: Ways forward. Available at: https://www.ourcommunity.com.au/files/WaysForward_FullReport.pdf [Accessed 16 October 2017].

New South Wales Government. (1919) Local Government Act 1919 (NSW). Available at: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/nsw/num_act/lga1919n41209.pdf [Accessed 16 October 2017].

New South Wales Government. (1979) Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 (NSW). Available at: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/nsw/consol_act/epaaa1979389/ [Accessed 16 October 2017].

New South Wales Government. (1993) Local Government Act 1993 (NSW). Available at: https://www.legislation.nsw.gov.au/~/view/act/1993/30 [Accessed 16 October 2017].

New South Wales Government. (2009) Local Government Amendment (Planning and Reporting) Act 2009 (NSW). Available at: http://www5.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/nsw/num_act/lgaara2009n67497.pdf [Accessed 16 October 2017].

New South Wales Government. (2013a) A new planning system for NSW: White Paper. Available at: https://majorprojects.accelo.com/public/50e8717a9968716223532455eb67e51e/White-Paper-full-document.pdf [Accessed 4 December 2018]

New South Wales Government. (2013b) Planning Bill 2013 (NSW). Available at: https://www.legislation.nsw.gov.au/bills/f779d670-218a-606a-a98d-8874159f0807 [Accessed 16 October 2017].

New South Wales Government. (2017) Environmental Planning and Assessment Amendment Act 2017 (NSW). Available at: https://www.legislation.nsw.gov.au/acts/2017-60.pdf [Accessed 25 November 2018].

Northern Territory Government. (1978) Local Government Act 1978 (NT). Available at: http://foundingdocs.gov.au/resources/transcripts/nt9_doc_1978a.pdf [Accessed 16 October 2017].

Northern Territory Government. (1993) Local Government Act 1993 (NT). Available at: https://legislation.nt.gov.au/api/sitecore/Act/PDF_History?id=18401 [Accessed 25 November 2018].

Northern Territory Government. (2008) Local Government Act 2008 (NT). Available at: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/nt/num_act/lga200812o2008228/ [Accessed 16 October 2017].

O’Connor, A. (2015) WA Government faces mounting pressure to dump council mergers. ABC News, 9 February 2015. Available at: http://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-02-09/local-government-peak-body-withdraws-support-for-council-amalga/6081382 [Accessed 16 October 2017].

Office of Local Government New South Wales. (2018) All New South Wales council contact details. Available at: https://www.olg.nsw.gov.au/content/download-council-contact-details [Accessed 24 May 2018]