RESEARCH and EVALUATION

Amalgamation of South Africa’s rural municipalities: is it a good idea?

Mkhululi Ncube

Local Government Unit

Financial and Fiscal Commission

South Africa

Jabulile Monnakgotla

Development Policy Research Unit

University of Cape Town

South Africa

Abstract

The majority of South African municipalities facing the challenges of unemployment, poverty and weak infrastructure are in rural areas. To fulfil their mandate, they depend significantly on financial transfers. This is something that the government is focused on minimising as evidenced by the recent Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs proposal of amalgamating many municipalities to make them self-reliant and functional. This paper asks the question: ‘will amalgamations of rural municipalities correct for financial viability and functionality’? Using case studies of amalgamated municipalities, the paper observes that amalgamations will not make all rural municipalities self-sufficient and functional.

Keywords: Amalgamations, financial viability, local government

Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance

Issue 19: December 2016

http://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/ojs/index.php/cjlg

© 2016 Mkhululi Ncube and Jabulile Monnakgotla. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Citation: Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance 2016, 19: 5487, - http://dx.doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.v0i19.5487

Introduction and problem statement

Local government in South Africa is facing a myriad of challenges that include poor economic growth and high levels of unemployment and poverty. According to the South African Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs (COGTA), a third of municipalities were classified as dysfunctional and unviable (whatever the definition), while another third are at risk, and the remaining third are functional and viable (Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs 2015).

The majority of unviable municipalities are in rural areas and depend significantly on grants to fulfil their mandates. The government is aiming to minimise this dependency, as evidenced by the recent proposal by COGTA to amalgamate many municipalities to make them self-reliant.

The COGTA sought to correct for dysfunctionality and financial unviability through the redrawing of municipal boundaries or simple amalgamation of some municipalities. In other words, the 2016 amalgamations were partly motivated by the desire to eliminate dependency and improve municipal functionality. According to the government proposal, financial viability equated to self-reliance or self-sufficiency. Dependency on grants is considered to be an indicator of lack of financial viability and a problem that can be addressed through demarcation, i.e. dividing the country into spaces that have roughly even revenue bases.

The idea of amalgamating municipalities to correct for dysfunctionality and improve their financial municipalities raises a number of research questions. First, is there a common understanding of what constitutes a viable municipality, and will merging municipalities create financially viable or self-reliant rural municipalities? Furthermore, is there a link between functionality and boundary changes, and can a boundary change or amalgamation solve functionality challenges? The main objective of this paper is to empirically evaluate the substance of the argument that the 2016 amalgamations will create ‘viable’ or self -sufficient/self-reliant or functional rural municipalities.

Thus, the purpose of this study is to assess whether municipalities which were due for demarcation during the 2016 local government elections will be viable and functional, at least according to the COGTA definition of viability and functionality. The data used in this paper is mainly secondary, and was sourced from National Treasury databases.

Background

Historical context of municipal demarcation in South Africa

Demarcations and amalgamations in the local government sphere are not a new phenomenon in South Africa. Between 1948 and 1994, the country’s decentralisation demarcated jurisdictions and organised governance on the basis of race, rather than on the basis of functional linkages or similar criteria (van Ryneveld 1996). The racially-driven, decentralised governance system consisted of two main categories – white local authorities (WLAs) and black local authorities (BLAs).1

WLAs represented the earliest example of fiscal decentralisation in South Africa. Established in the early 1900s, they covered most of the country’s urban areas, and were primarily responsible for providing services to urban white, Coloured and Indian citizens living in areas outside of the homelands. Access to relatively wealthy social groups meant that WLAs enjoyed a high degree of fiscal autonomy. In fact the notion of a viable municipality comes from the era of WLAs. WLAs were ‘viable’ in the sense that they were self-sufficient. They had all the tax bases (property taxes and fees) and so relied entirely on own revenues but served only a small section of the population. In contrast, post-1994 municipalities have a fundamentally different mandate, do not have all the tax bases, rely significantly on transfers and cover entire populations, including rural areas. Therefore, it is difficult to subscribe to the same notion of viability.

Initially administered by adjacent WLAs, the BLAs evolved from the community councils that were introduced in response to the uprisings of June 1976. The BLAs enjoyed very little political legitimacy, as they were regarded as a façade set up by the apartheid regime to give some form of democracy to black South Africans, while entrenching segregation (Bahl and Smoke 2003). The BLAs were unable to develop productive tax bases because of apartheid restrictions on economic development in black areas, insufficient socio-economic infrastructure that could generate service fees, and lack of access to property, quality education and formal employment among black South Africans. As a result, BLAs generated very little own-revenue, operated inefficient fiscal systems, and lacked the capacity to provide the necessary socio-economic services (Amusa and Mabugu 2016).

For much of the late 1980s and early 1990s, public anger over appalling service levels and attempts to impose rents and service charges in the BLAs led to violent rent boycotts, and fuelled the drive by civic organisations and activists to link local grievances to internal efforts to overthrow apartheid. As part of political efforts to end apartheid, a Local Government Negotiating Forum (LGNF) was established in 1992, and tasked with negotiating local settlements to rent and service boycotts, and amalgamating racially divided local authorities into a new local government system that would be more widely accepted. By 1993, negotiations at the LGNF resulted in the enactment of the Local Government Transition Act (LGTA) which outlined three phases – the pre-interim, interim and final phases as steps towards completing the formal role of local governments under a democratic dispensation (Smoke 2001; Powell 2012).

The pre-interim phase covered the period between the democratic election of 1994 and the first local government democratic elections held in 1995/96. In terms of the LGTA, local government was organised through locally negotiated transitional councils that were established via “negotiating transitional forums” within each municipal area. Representation on these transitional councils took the form of members appointed in equal proportions from statutory institutions (such as the WLAs, BLAs and designated Indian and Coloured administrations), and non-statutory bodies (mainly civic organisations, trade unions and previously unrepresented political parties). This phase concluded with 1995/96 local government elections which ushered in the interim phase. A major prerequisite for the 1995/96 local government elections was to amalgamate the inherited apartheid-era local government structures. To facilitate this, the LGTA provided for the establishment of a Local Government Demarcation Board in each of the nine provinces, and granted these boards advisory powers to make recommendations on matters relating to boundary and ward delimitation to their respective provincial Ministers of Local Government.

The process of boundary and ward delimitation for the interim phase led to the creation of three types of municipalities: metropolitan, urban and rural. The six large urbanised areas of the country (four in the Johannesburg–Pretoria area plus one each in Durban and Cape Town) were administered within a two-tier system consisting of transitional metropolitan councils (TMCs) and transitional metropolitan substructures, while transitional local councils (TLCs) were established to govern urban areas. For rural areas not included within TLCs, local governance structures took one of three types: transitional representative councils, transitional rural councils (TRCs) and district councils (Schroeder 2003; Cameron 2006).

Chapter 7 of the 1996 Constitution made provision for three categories of municipalities: (i) Category A municipalities (metropolitan councils) that exclusively covered large urban areas; (ii) Category B municipalities (local councils) that administer non-metropolitan areas, which vary in size and extent of urbanisation, and (iii) Category C municipalities (districts councils).2 The Local Government Demarcation Act (No. 27 of 1998) became the major policy instrument for dismantling locally segregated local government and ushering in the final phase of the local government transformation process (Government of South Africa 1998). In line with the Constitution, which stipulates that municipal boundaries are demarcated by an independent body, the Act merged the nine provincial demarcation boards into a single entity: the Municipal Demarcation Board (MDB). Unlike provincial boards, which had played a largely advisory role, the MDB was granted the status of the final decision-making body over matters of municipal demarcation and delimitation of municipal borders.3

In preparation for the 2000 local elections, which commenced the final phase of transforming the local government sphere, the MDB initiated two important changes to the composition of local governments. First, it established “wall-to-wall” municipalities, in accordance with the Constitution that called for municipalities to “be established for the whole of the territory of the Republic”4 (De Visser 2005, p.75). Second, the MDB consolidated the former TLCs into a single local jurisdiction, which meant that a number of former TLCs would be included within the boundaries of Category B municipalities. As a result of the MDB’s demarcation process, by the 2000 local elections, the complex system of 843 transitional municipalities had been consolidated into 284 municipalities. The country’s six largest urbanised and industrialised centres made up the Category A municipalities. Outside the metropolitan areas, a two-tier structure was established with 231 Category B municipalities falling within 47 Category C district councils. Then, in preparation for the 2006 local elections, the MDB consolidated the number of municipalities to 283. This reconfiguration resulted in the disappearance of cross-boundary municipalities. Ahead of the 2011 local elections, the number of municipalities was further reduced to 278: Category A municipalities (Metropolitan or Metros) increased from 6 to 8, while the number of local municipalities (LMs) and district municipalities (DMs) decreased to 226 and 44, respectively.

The motive underpinning the demarcations in the 1990s was to de-racialise municipalities that were segregated along apartheid spatial lines and, to an extent, redistribute resources from affluent municipalities to poor municipalities. White municipalities had clear tax bases, capacity and other resources but were only serving very small populations, whereas the black authorities consisted of mainly townships, tended not to have strong tax bases, and were characterised by a culture of poor services and non-payment for services. For example, in Cape Town, the main rationale for amalgamation in 1996 was to redistribute from rich municipalities to poor municipalities. The Western Cape Demarcation Board deliberately drew the boundaries of Cape Town to amalgamate the former black and white municipalities. This resulted in a one-tier municipality with geographic boundaries that cover the economic region. However, amalgamating the previously black and white local authorities created problems, such as collapsing infrastructure (e.g. water and sewerage systems) because of the increasing number of people that now had to be serviced. Other challenges included financial stress due to increasing salaries, limited experience and lack of capacity.

In 2002, financial viability became a demarcation issue after The Presidential Coordinating Council (PCC) passed a number of resolutions on local government, including the need to build financially viable municipalities. The issues of municipal financial viability are not new but has still not been resolved 15 years after developing local government.

Demarcations in 2016

In 2015 the Minister of COGTA proposed further boundary changes that would see more municipalities becoming even larger. As noted above, the principal motivation for these changes was to ensure that municipalities are financially viable and functional. This study addresses the question of whether these amalgamations will result in viable (self-sufficient/self-reliant) or functional municipalities. The 2015 boundary redeterminations will reduce the number of municipalities by 21, from 278 to 257. Table 1 shows the distribution of municipalities affected by demarcations due in 2016.

Table 1: Municipalities affected by boundary redeterminations for 20165

| New municipality | Affected municipalities (amalgamations) |

| Eastern Cape | |

| Camdeboo LM, Baviaans LM and Ikwezi LM | |

| EC129 | Nxuba LM and Nkonkobe LM |

| EC139 | Inkwanca LM, Tsolwana LM and Lukanji LM |

| EC145 | Gariep LM and Maletswai LM |

| KwaZulu Natal | |

| KZN212 | Vulamehlo LM and Umdoni LM |

| KZN216 | Ezinqoleni LM and Hibiscus Coast LM |

| KZN237 | Umtshezi LM and Imbabazane LM |

| KZN238 | Emnambithi/ Ladysmith LM and Indaka LM |

| KZN276 | Hlabisa LM and The Big Five False Bay LM |

| KZN282 | uMhlathuze LM and Ntambanana LM |

| KZN285 | Mthonjaneni LM and Ntambanana LM |

| KZN436 | KwaSani LM and Ingwe LM |

| Free State | |

| MAN | Mangaung Metro and Naledi LM |

| Limpopo | |

| LIM341 | Musina LM and Mutale LM |

| LIM343 | Thulamela LM and Mutale LM |

| LIM345 | Makhado LM and Thulamela LM |

| LIM351 | Blouberg LM and Aganang LM |

| LIM353 | Molemole LM and Aganang LM |

| LIM354 | Polokwane LM and Aganang LM |

| LIM368 | Modimolle LM and Mookgopong LM |

| LIM476 | Fetagomo LM and Gretaer Tubatse LM |

| Mpumalanga | |

| MP326 | Umjindi LM and Mbombela LM |

| Northern Cape | |

| NC087 | Mier LM and //Khara Hais LM |

| North West | |

| NW405 | Tlokwe LM and Venterdorp LM |

Source: MDB Circular 2015

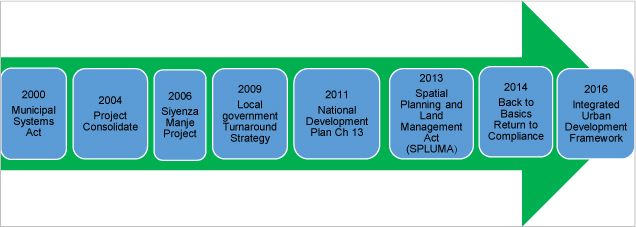

Amalgamation of municipalities was not the only instrument used to improve the performance of the local government. Government and other entities have initiated a number of projects and programmes aimed at improving the performance of the sector (Figure 1). After the 2000 local government elections, the government introduced project consolidate in 2004 (COGTA 2004). This initiative was a hands-on programme to support local government. In 2006, the Development Bank of Southern Africa (DBSA) initiated the Siyenza Manje project; a capacity building initiative jointly funded by DBSA and National Treasury (DBSA 2009). In 2009 a local government turnaround strategy was launched by the Department of Cooperative Governance (Department of Cooperative Governance 2009). Another milestone in the development of the local government sector was the launch of the National Development plan in 2011, which sought the creation of a capable local government (National Planning Commission 2011). In 2013 the government enacted the Spatial Planning Land Management Act, followed by the Back to Basics programme in 2014, and the Integrated Urban Development Framework in 2016.

Figure 1: Other local government initiatives since 2000

Source: Authors’ illustrations and South African Cities Network (2016)

Literature review

South Africa’s local government sector within a global context

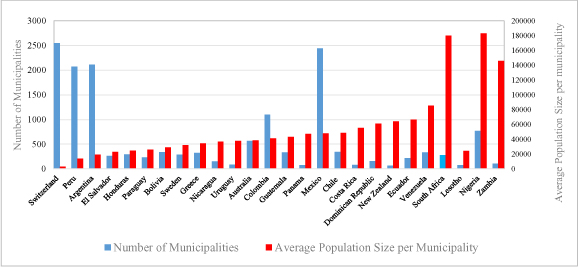

With the reduction in the number of municipalities, from 278 to 257, a comparison with other countries is pertinent. International literature is clear that no standard size of a municipality exists, whether by geographical space, population size or political representation. South Africa has one of the lowest number of municipalities in the world, but the country has (a) one of the largest average populations per municipality (Figure 2), and (b) one of the highest number of citizens per councillor (Table 2). This situation has far-reaching implications for political representation, and democratic and governance accountability. When a local government structure is large, access to authority through public hearings, meetings, elections or direct contact is difficult; political representatives are far removed from the electorate; and citizen participation is weaker.

Figure 2: Number of municipalities and average municipal population sizes

Source: Financial and Fiscal Commission (2016)

Table 2: Number of citizens per councillor

| Number of councillors | Number of citizens per councillor | |

| Namibia (2010) | 323 | 6929 |

| Botswana (2014) | 589 | 3660 |

| Republic of Ireland (2014) | 949 | 4861 |

| Mozambique (2014) | 1196 | 20937 |

| Lesotho (2011) | 1276 | 1502 |

| New Zealand (2000) | 1892 | 2039 |

| Zimbabwe (2013) | 1962 | 6854 |

| Philippines (2000) | 2102 | 37075 |

| Malaysia (2000) | 2921 | 7654 |

| Nepal (2000) | 3344 | 7099 |

| Australia (2000) | 6637 | 2886 |

| South Africa (2011) | 9090 | 5671 |

| Madagascar (2008) | 9608 | 2335 |

| Canada (2014) | 19534 | 1819 |

| Japan (2000) | 62452 | 2031 |

| China (2000) | 653244 | 1933 |

NB: The date in brackets indicates the year during which data was collected

Source: Financial and Fiscal Commission (2016)

Why amalgamate municipalities?

Literature cites a number of reasons for amalgamations including that of economies of scale and scope. Bigger municipalities are considered far much effective for service delivery than smaller fragmented municipalities. In South Africa literature cites four reasons for municipal amalgamations: (a) to deracialise local government, (b) to achieve equity; (c) create efficiencies and economies of scale; (d) promote integration of rural and urban municipalities, (e) improve the financial and administrative capacity of smaller municipalities by combining existing capacities and (f) improve service delivery and broaden revenue bases of municipalities (Government of South Africa 1998; Peterson and Annez 2007; Kanyane and Koma 2006.). The municipal mergers immediately after the new democratic dispensation were largely focused on integrating different races and redistributing resources from more affluent municipalities to poor ones, while later mergers put emphasis on improving service delivery and broadening the revenue base.

International literature abounds with literature on municipal mergers and reasons for such amalgamations. Slack and Bird (2013a, 2013b) have noted that bigger municipalities perform better than fragmented ones. The argument is that “bigger is better” and “bigger is cheaper” because larger municipalities result in improved productivity, cost savings, enhanced quality and mix of public goods, increases administrative and technical capacity and promotes effective lobbying with other spheres of government (Dollery and Robotti 2008). Municipal amalgamation eliminates some duplication, for instance, the number of politicians and bureaucrats could be reduced. Bigger municipalities are more often able to provide an extensive array of services than small fragmented municipalities (Dollery et al. 2007; Slack and Bird, 2013a).

On the other hand, international literature also puts across very strong arguments against consolidation. Slack and Bird (2013a) argue that amalgamations of municipalities with different service levels and wage scales often translate into increased expenditures. According to these authors, salaries and benefits tend to equalise up to the level of the former municipality with the highest expenditures. This upward harmonisation of wages and salaries generally outweighs any cost savings. Consequently, in smaller municipalities, those employees who become part of the amalgamated municipality could demand wage parity with their counterparts at the larger municipality thus pushing its operating costs higher. Faguet (2004, 2011) argues that many smaller municipalities stimulate competition, which is sometimes an incentive for them to be efficient, responsive and accountable to community needs.

However, despite all the strong arguments for and against consolidation, empirical evidence is at best mixed (Lago-Penas and Martinez-Vazquez 2013) and suggests that there is no optimal municipal size (Boyne 1998; Oakerson 1999; Bish 2000; Dollery et al. 2012). After reviewing research in the UK and USA on economies of scale, Byrnes and Dollery (2002) concluded that only 8% of the studies found evidence of economies of scale, 24% found evidence of diseconomies of scale, 29% found evidence of U-shaped cost curves and 39% found no evidence of economies of scale. On the other hand, a study of the amalgamations of Canadian municipalities found no evidence of economies of scale post 2005–2008 boundary changes (Found 2012). In the USA, Boyne (1995) found evidence that consolidation is associated with higher spending while in Canada, Kushner and Siegel (2005) found that amalgamations of local governments improved efficiency in some municipalities while inefficiencies increased after some amalgamations. Cowley (2009) further argues that service delivery and administrative efficiencies are achieved with high-density developments, but are compromised with spread-out, low-density developments that are more costly to serve. Therefore, amalgamation may not achieve the economies of scale hoped for, but merely avoids insolvency for the dissolving municipality by spreading its operating costs over a wider tax base.

Table 3 summarises this literature. The main message from this literature is that boundary changes can either have positive or negative fiscal consequences on municipalities as well as on their fiscal/financial viability. It is an issue that can be answered empirically as it depends on a number of contextual issues.

Table 3: Summary of literature on the impact of municipal boundary changes

| Author | Country | Findings |

| Dollery et al. (2007) | South Australia | The study looked at the impact of municipal amalgamation on financial viability of the south Australian local government; focusing on whether a size of a municipality improves its viability. The results indicate that there is no correlation between the municipal size and its viability. It further suggests that alternative methods to improve viability and effectiveness of local authority be pursued. |

| Forsyth (2010) | America | The question asked in this study is: “Is a county’s post consolidation (boundary change) economic development significantly better than reconsolidation development?” Using time series regression analysis the study concluded that consolidations have significant impact on the distribution of economic burdens within a county, while impacts on economic development are not significant and limited on social development. The study also concludes that there are no efficiency gains that result from consolidation of counties. |

| Savitch and Vogel (2004) | America | The study tests the hypothesis that city-county consolidation promotes efficiency, equity and accountability. The study found that mergers reduce efficiency, costs associated with transition and harmonising employment and wages increases, minimal cost savings, inequities continue and accountability problems worsen. |

| Fleischmann (1986) | America | The study looks at the benefits and costs of local boundary changes and who are the losers or winners. The study uses a case study methodology. The findings note gains such as new revenues sources (increased tax base). Areas that were poor before boundary changes benefited in the form of improved service delivery. The study notes also political and social costs/benefits. The study also found that in boundary changes the winners are largely the private actors. |

| Ncube and Vacu (2014) | South Africa | This study looked at the fiscal and financial impacts of municipal boundary changes. The case studies and the econometric models in this study suggest that demarcation processes in South Africa have resulted in unintended economic consequences and significant transaction costs, especially during the transition phase. |

| City of Tshwane Budget Office (2013) | South Africa | This study sought to quantify the costs of the merger between the City of Tshwane and two local municipalities (Nokeng tsa Taemane and Kungwini). The findings of this study suggest that the costs related to this amalgamation were close to R1 billion. |

| Reingewertz (2012) | Israel | The study assessed the fiscal outcomes of municipal amalgamation using the difference in differences method. The results indicate that amalgamation leads to a decrease in municipal expenditures but at the same time, it causes no decrease on the quality of services provided. Based on this, the study concludes that amalgamation may have a positive impact on municipal viability. |

| Fritz (2013) | Germany | The study examined whether the large scale municipal amalgamations had an impact on the fiscal outcomes of the municipalities in Germany, using differences in difference approach. The results suggest that it has a significant effect, indicating a positive impact of municipal amalgamation on debt per capita and expenditure per capita and a negative impact on expenditure for administrative staff. |

Methodology

According to COGTA, a third of municipalities are dysfunctional and unviable (whatever the definition) while another third are at risk, and the remaining third are functional and viable. The motivation underpinning the COGTA proposal is the elimination of dysfunctional and non-viable municipalities. This section explains how viability, functionality and revenue-raising capacity are evaluated.

Functionality

Functionality refers to how badly or how well a municipality operates, delivers services and accounts for the money it spends. The functionality of rural municipalities scheduled for amalgamation in 2016 will be assessed by looking at the functionality indicators of management stability, fiscal stress levels and audit profiles.

Viability

The self-sufficiency or self-reliance (viability) of a municipality can be measured by its ability to raise own revenues to pay for basic public services (as per its constitutional mandate). One way of assessing the ability of demarcated municipalities to fulfil their constitutional mandate is to compare the gap between expenditure needs and revenue-raising capacity (Bandyopadhyay 2013). This gap is often referred to as the need-capacity gap or fiscal gap. Expenditure needs refer to the amount of money needed to provide minimum acceptable levels of public goods (water, electricity, refuse removal, roads, etc.), while revenue-raising capacity refers to revenues that the municipality can raise from own sources (own revenues) when exerting a standard amount of effort.

A municipality’s revenue-raising capacity depends on its fiscal capacity, which can be measured using many variables. These variables range from a municipality’s tax and revenue base, to its socio-economic framework and all other political and legal constraints that may prevent its full revenue potential being realised. The most important component of a municipality’s fiscal capacity is its economic base. Fiscal capacity will be assessed using the following measures:

- Per capita income (the wealth or income of a municipality divided by its population) captures a municipality’s ability to handle a tax burden, or ability of individuals within a municipality to meet the financial needs of the community. The measure is simple and easier to understand.

- Per capita gross value added (GVA) captures the value of goods and services produced by a municipality over a given period. A higher per capita GVA value signifies a larger revenue base and greater ability to pay taxes.

- Employment (and unemployment) rates are indicators of a municipality’s fiscal capacity. A higher employment rate implies a bigger tax base, as employed people pay taxes and fees, whereas a high unemployment rate means a smaller revenue base for a municipality.

- Property rates per capita are an important measure of fiscal capacity for local governments. These taxes are significant in many municipality governments. A municipality with many properties/estates is likely to raise more revenues. Similarly when property values increase, revenue yields are likely to increase.

The following section tackles the issue of whether amalgamated municipalities will be viable in the COGTA sense.

Amalgamation and municipal viability

In the COGTA proposal, viability refers to the ability of municipalities to fulfil their constitutional mandates using their own resources. In other words, demarcations will result in municipalities that are self-reliant and self-sufficient, have a strong fiscal base to support their constitutional mandates and minimum dependency on intergovernmental transfers. Fiscal capacity is crucial for a municipality to be viable/self-sufficient or self-reliant, and so the fiscal capacities of the soon-to-be-demarcated municipalities were evaluated using a number of indicators, including revenue-raising capacity. As with other studies (Bandyopadhyay 2013; Yilmaz et al. 2007), all measures of fiscal capacity were indexed to the average, i.e. the average for each measure of fiscal capacity drawn from the whole of South Africa was equated to 100 and this was used as a base, against which individual municipality indicators were compared. These indicators are not measures of the fiscal health of a municipality but a relative gauge of whether or not a particular municipality can sustain all the assigned mandates using its own resources without intervention from national and provincial governments. Furthermore, the South African average is not necessarily the optimum but, in the absence of norms or standards, gives an indication of where an average municipality is operating in South Africa. The reader is also reminded that these measures evaluate a municipality’s fiscal capacities relative to the national average, not their absolute fiscal capacities.

Dependency on transfers

Self-sufficient municipalities do not need to depend on transfers for their basic needs and are capable of delivering a range of services using own revenues. A simple dependency ratio (transfers/operating revenues) can reveal whether municipalities can sustain their mandates without significant assistance from national and provincial governments. The ratios used are the local government equitable share (LGES) as a share of total municipal operating revenue and transfer capital funding as a percentage of total capital funding.

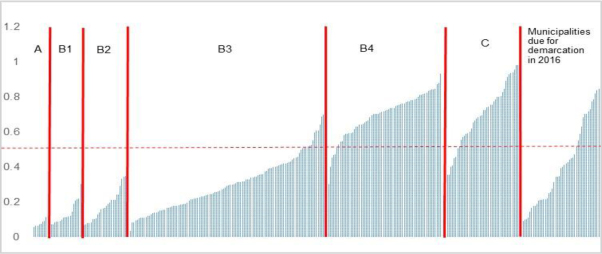

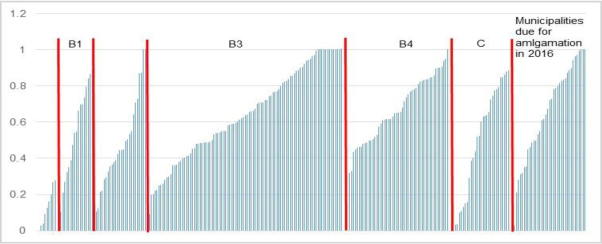

As Figure 3 shows, the dependency ratios vary widely, from metros (A) that derive less than 10% of their revenues from transfers, to district municipalities (C) that rely on transfers for almost 90% of their total revenues. The majority of rural municipalities (B3s and B4s)6 virtually all depend on transfers for more than 20% of their revenues, with most B4s relying on transfers for more than 50% of revenue. These municipalities are unlikely to be self-reliant and will always be dependent on transfers. In the case of the municipalities that are due for demarcation, a majority of them depend for more than 50% of their operational revenues on the LGES. A similar picture emerges for capital funding (Figure 4).

Figure 3: LGES as a percentage of operating revenue

Source: Authors’ calculations

Figure 4: Total transfer capital funding as a percentage of total capital funding

Source: Authors’ calculations

What Figures 3 and 4 show is that, given the present configurations, rural municipalities and municipalities due for demarcation will never sustain their activities without transfers. Therefore, amalgamation will never make them self-reliant because of their limited revenue base and high levels of dependency. This implies that the funding model for rural municipalities and those due for demarcation should always consist of transfers.

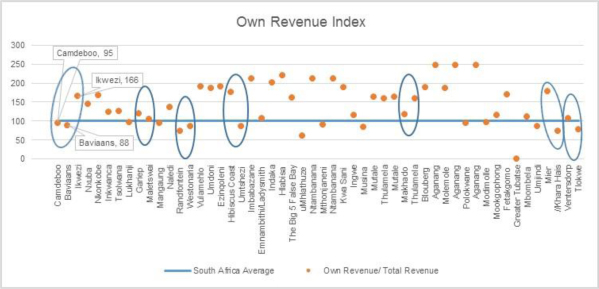

Own revenue index

The own revenue index (Figure 5) is used to measure grant dependency of the 52 municipalities to be amalgamated. The index is generated from a municipality’s own revenue to total revenues ratio. For illustrative purposes, seven examples of municipal clusters for amalgamation are shown in the oval shapes in Figure 5. According to the index, own revenue is the main source of income for 35 out of the 52 municipalities due for amalgamation (i.e. their own revenues are above the South African average). Figure 5 shows that most of the municipalities due for amalgamation will always be reliant on transfers.

In other words, for many municipalities, a significant degree of dependency will disappear through amalgamations, while for some clusters, grant dependency is likely to intensify. This means that transfers will continue to be the main funding window for many rural amalgamated municipalities.7

Figure 5: Own revenue index

Source: Authors’ calculations

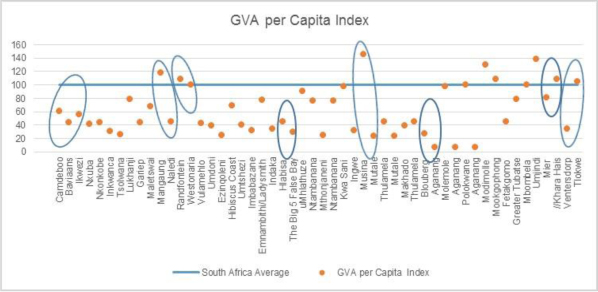

Per capita gross value addition (GVA) index

This per capita GVA index measures the value of goods and services produced by a municipality over a given period. A municipality with a higher per capita GVA value has a potentially larger revenue base and greater ability to pay taxes than one with a low GVA value.

All municipalities due for demarcation were compared to the average for all municipalities (Figure 6), and oval shapes show some (not all) amalgamation combinations. It is quite clear that the majority of municipalities due for demarcation in 2016 are below the South African GVA average, implying that a significant number have a weak potential revenue base. Examples of amalgamations that consist of municipalities with GVA per capita indices below average include Camdeboo, Baviaans and Ikwezi; Hlabisa and The Big Five False Bay; and Blouberg and Aganang. This suggests that some of the proposed amalgamations will not necessarily result in municipalities with a better revenue base.

Figure 6: GVA index

Source: Authors’ calculations

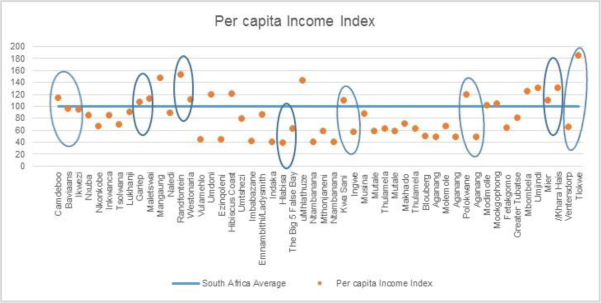

Per capita income

Another well-known indicator of fiscal capacity is per capita income (Tannernwald 1999; Bandyopadhyay 2013; Yilmaz et al. 2006). Like per capita GVA, the per capita income measure captures the wealth or income potential of a municipality through a community’s ability to meet its financial needs. As Figure 7 shows, around 70% of the municipalities to be demarcated in 2016 fall below the South African average for per capita income. This is a further indication that, other things being held constant, the communities of such municipalities (e.g. the Hlabisa and Big Five False Bay amalgamation) would be hard pressed to meet their financial needs.

Figure 7: Per capita income index

Source: Authors’ calculations

Employment

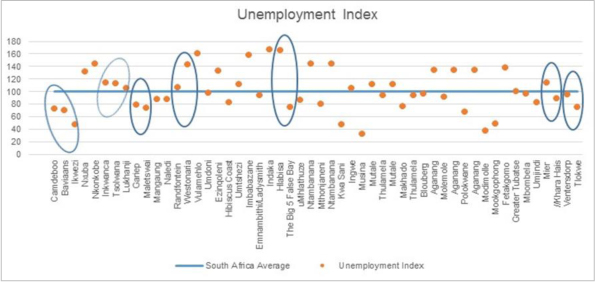

A municipality’s revenue base also depends on the employed population within its jurisdiction. The likelihood of a municipality generating a steady stream of revenues is high when a significant proportion of its population is employed. Conversely, the tax base is constrained when the unemployment rate is high. Figure 8 shows that almost half of the municipalities due for amalgamation in 2016 have below-average unemployment rates, indicating a weak revenue base. Clusters with above average unemployment rates include Camdeboo, Baviaans and Ikwezi; Inkwanca, Tsolwana and Lukhanji; and Ventersdorp and Tlokwe.

Figure 8: Unemployment index

Source: Authors’ calculations

Poverty index

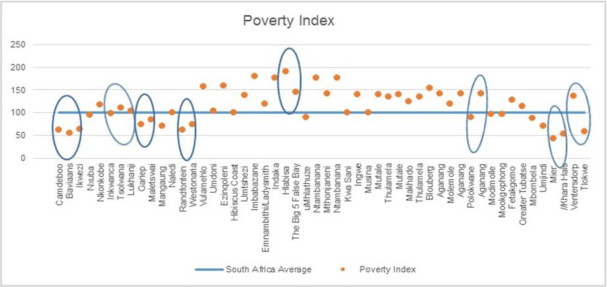

Poverty is another variable that explains a municipality’s fiscal capacity, with high levels of poverty implying a weak revenue capacity. Poverty levels for all municipalities due for demarcation were compared with the average poverty level for all South African municipalities. Figure 9 indicates that over 60% of municipalities fall below the average poverty level. This suggests that for many municipalities (e.g. Hlabisa and The Big Five False Bay), the mergers will not improve their poverty levels nor their revenue base.

Figure 9: Poverty index

Source: Authors’ calculations

The above analysis suggests that a significant number of municipalities due for amalgamations in 2016 have weak revenue-raising capacities. This implies that amalgamations will not make many municipalities viable or self-sufficient or self-reliant. With weak revenue bases, most of the municipalities will continue to depend on transfers. Besides transfers, alternative revenue sources are required for such municipalities. The focus should also be on increasing or developing tax bases through economic development rather than amalgamating municipalities.

Viability and demarcation

Can amalgamations correct for municipal dysfunctionality?

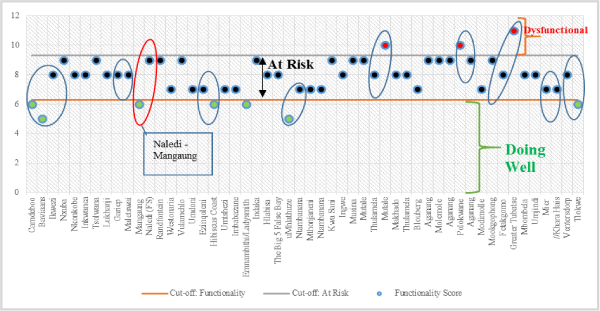

The functionality of a municipality is a function of many factors, within and outside a municipality’s control. The functionality of the municipalities due for amalgamation in 2016 were assessed using four factors: (i) institutional management, (ii) financial management, (iii) governance and (iv) service delivery. Figure 10 shows that most municipalities (80%) are at risk of being dysfunctional and 6% are dysfunctional. Amalgamating municipalities that are at risk of being dysfunctional may actually worsen the problem. An interesting result concerns the amalgamation of a functional metro (Mangaung) and a dysfunctional rural area (Naledi). While this merger may achieve financial viability/self-reliance, two important elements of municipal viability - governance and democracy - may be compromised. With the amalgamation, political representation for marginalised communities in Naledi virtually disappear, and in many ways rural governance of these communities becomes less functional, as an urban core governs and administers rural areas. Although Naledi may not be able to achieve financial viability, it could serve a critical constitutional and democratic role.

Figure 10: Municipal functionality

Source: Authors’ calculations

Given that many municipalities due for demarcation are not functioning well, the question becomes whether demarcation is the appropriate instrument for addressing their challenges and whether functionality can be a criterion for demarcating municipalities. In reality, many factors can cause a municipality to be dysfunctional. They include service delivery, institutional management, financial management, community satisfaction, and governance or political stability. Furthermore, such factors do not have a direct bearing on (or can be influenced by boundary changes). For example, using demarcation to correct for financial mismanagement is akin to providing a patient with a wrong pill, which may do more harm than good. The primary mandate of the Municipal Demarcation Board (MDB) is to demarcate municipal boundaries, delimit wards and carry out municipal capacity assessments, as spelt out in the Local Government: Municipal Demarcation Act (No. 27 of 1998). Correcting for dysfunctionality in municipalities is clearly not part of the MDB mandate, but that of national and provincial governments, which have a range of monitoring, support, regulatory and intervention powers at their disposal. As there are no apparent connections between municipal boundaries and municipal functionality, elevating the issue of functionality to a demarcation criterion may simply raise expectations that will never be fulfilled by demarcation. Furthermore, problems of dysfunctionality are often temporary and transient, and cannot be solved by a long-term drastic measure such as demarcation.

Conclusions and implications

Government seeks to make rural municipalities self-sufficient and less dependent on transfers. In 2015, it proposed using demarcations to achieve financial viability or self-sufficiency, and to improve functionality among rural municipalities. However, an analysis of municipalities to be demarcated in 2016 found that amalgamations will not necessarily result in financially viable municipalities and may worsen the situation of some of the demarcated municipalities. The dependency ratio of many demarcated rural municipalities is too high to be reversed by amalgamations. Many rural municipalities will continue to be transfer dependent, as their revenues bases are fragile and weak. Transfers will remain the mainstay of rural local government. The transfer system must also cater for the Constitution’s acknowledgement of transfer-dependent municipalities (the Constitution sets no financial viability requirement for all municipalities but makes provision for some municipalities to be transfer dependent) (Government of South Africa 1996). Some municipalities should exist to serve other equally important roles, such as ensuring that communities are politically and democratically represented. Amalgamations should carefully be studied, and benefits of amalgamations should be based on sound empirical evidence.

On functionality, the study noted elevating this to a demarcation criterion is problematic as there is no direct nor indirect link with municipal boundaries. Municipalities can be dysfunctional for a variety of reasons that have no relationship with boundary demarcation. Amalgamations are a long-term measure that cannot correct for short-term operational problems associated with municipal dysfunctionality.

The foregoing analysis has demonstrated that many rural municipalities will continue to be transfer dependent. The analysis also suggests that demarcations are a weak instrument for pursuing financial viability of rural municipalities and a wrong one for improving the functionality of municipalities. The foregoing analysis lends itself to the following recommendations:

- Rural municipalities with a low revenue base should be allowed to exist and funded through the transfer system and not forced to amalgamate as such municipalities could be serving other crucial constitutional imperatives such as democratic representation and community participation. For rural municipalities, the funding model should allow for the existence of municipalities with a low revenue base rather than forcing amalgamations. This funding model should differentiate among rural municipalities, in terms of their revenue base.

- To achieve financial viability, government should focus on increasing or developing tax bases through economic development rather than amalgamating municipalities.

- Functionality should not be elevated to a demarcation criteria as it has no direct nor indirect link with boundary changes. Functionality should be corrected through legislative, policy and capacity building measures than through amalgamations.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to the editor and the anonymous referees for many valuable comments. The generous funding for this study from the Financial and Fiscal Commission is hereby acknowledged. This article is an expanded and updated version of the paper written for the Financial and Fiscal Commission. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Financial and Fiscal Commission.

References

Amusa, H. and Mabugu, R. (2016) The contribution of fiscal decentralization to regional inequality: Empirical results for South African municipalities. ERSA working paper 597. Available at: http://www.econrsa.org/system/files/publications/working_papers/working_paper_597.pdf [Accessed December 2016].

Bahl, R. and Smoke, P. (2003) Overview of the local government revenue system. In: Bahl, R. and Smoke, P. (eds) Restructuring local government finance in developing countries: Lessons from South Africa (pp. 1–22). Chelternham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Bandyopadhyay, S. (2013) Estimating fiscal health of cities: A methodological framework for developing countries. Working Paper Series No. 49. New Dehli, India: International Center for Public Policy.

Bish, R. (2000) Local government amalgamations: 19th century ideas for the 21st century. Toronto, Canada: Howe Institute.

Boyne, G.A. (1995) Population size and economies of scale in local government. Policy and Politics, 23 (3), 213–222. doi: https://doi.org/10.1332/030557395782453446

Boyne, G.A. (1998) Public choice theory and local government. Basingstoke, UK: Macmillan. doi: https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230373099

Byrnes, J. and Dollery, B. (2002) Do economies of scale exist in Australian local government? A review of the research evidence. Urban Policy and Research, 20 (4), 391–414. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/0811114022000032618

Cameron, R. (2006) One city, one tax base. In: Pillay, U., Tomlinson, R. and du Toit, J. (eds) Democracy and delivery: Urban policy in South Africa (pp. 76–106). Cape Town: HSRC Press.

City of Tshwane Budget Office. (2013) Submission on the costs incurred for the merger of the municipalities of Metsweding, Kungwini and Nokeng tsa Taemane into the City of Tshwane. Pretoria: South Africa: City of Tshwane Budget Office.

Cowley, B. (2009) Surviving and thriving in an irrational world. Commentary based on a talk to the Alberta Urban Municipalities Association, Red Deer, Alberta, Canada. Available at: http://aims.wpengine.com/site/media/aims/MunicipalGovernment.pdf [Accessed December 2016].

De Visser, J.W. (2005) Developmental local government: A case study of South Africa. Antwerp-Oxford, London: Intersentia.

Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs. (2004) Project ‘consolidate!: A hands-on local government engagement. Programme for 2004–2006. Pretoria, South Africa: COGTA.

Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs. (2009). State of local government in South Africa. Pretoria, South Africa: COGTA.

Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs. (2015). Framework for municipal functionality and viability. Pretoria. South Africa: COGTA.

Development Bank of Southern Africa. (2009) Making local government work. Johannesburg, South Africa: DBSA.

Dollery, B.E., Byrnes, J.D. and Crase, L. (2007) Too tough a nut: Determining financial sustainability in Australian local government. Australasian Journal of Regional Studies, 13 (2), 110–132.

Dollery, B.E., Grant, B. and Kortt, M. (2012) Councils in cooperation: Shared services and Australian local government. Sydney: Federation Press.

Dollery, B.E. and Robotti, L. (eds) (2008) The theory and practice of local government reform. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Faguet, J.P. (2004) Does decentralization increase responsiveness to local needs? Evidence from Bolivia. Journal of Public Economics, 88 (4), 867–894. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-2727(02)00185-8

Faguet, J.P. (2011) Decentralization and governance. Economic Organisation and Public Policy Discussion Papers, EOPP 027. London, UK: London School of Economics and Political Science. doi: https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1892149

Financial and Fiscal Commission. (2016) Financial and Fiscal Commission annual submission 2017/18. Johannesburg, South Africa: FFC.

Fleischmann, A. (1986) The goals and strategies of local boundary changes: Government organization or private gain? Journal of Urban Affairs, 8 (4), 63–76. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9906.1986.tb00155.x

Forsyth, G. (2010) Municipal economies of scale and scope and post-consolidation economic performance: A literature review. Monograph No. 15. Washington: Institute for Public Policy and Economic Analysis, Eastern Washington University, Washington DC, United States of America.

Found, A. (2012) Scale economies in fire and police services. IMFG Paper No. 12. Toronto: Institute on Municipal Finance and Governance, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada.

Fritz, B. (2013). Fiscal effects of municipal amalgamations: Evidence from a German state. Paper prepared for the 15th Annual Conference of the International Society for New Institutional Economics, Walter Eucken Institute, Freigburg, Germany.

Government of South Africa. (1996) Constitution of the Republic of South Africa. Pretoria, South Africa.

Government of South Africa. (1998) Local Government: Municipal Demarcation Act, 1998. Pretoria, South Africa: Government Gazzette, Government of South Africa.

Kanyane, M.H. and Koma, S. (2006) A decade of making local government an effective, efficient and viable agent of service delivery in South Africa: A post-apartheid perspective. Teaching Public Administration, 26 (1), 1–12. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/014473940602600101

Kushner, J. and Siegel, D. (2005) Citizen satisfaction with municipal amalgamations. Canadian Public Administration, 48, 73–95. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1754-7121.2005.tb01599.x

Lago-Penas, S. and Martinez-Vazquez, J. (eds) (2013) The challenge of local government size. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Press.

Lemon, A. (1992) Restructuring the local state in South Africa: Regional services councils, redistribution and legitimacy. In: Drakakis-Smith, D. (eds) Urban and regional change in Southern Africa (pp. 1–32). London: Routledge.

Municipal Demarcation Board. (2015) MDB Circular 12/2015. Pretoria: Municipal Demarcation Board.

National Planning Commission. (2011) National Development Plan: Vision for 2030. Available at: http://www.gov.za/sites/www.gov.za/files/devplan_2.pdf [Accessed December 2016].

Ncube, M. and Vacu, N. (2014). The impact of demarcations on the financial performance and sustainability of municipalities. In FFC (2014) Submission for the 2015/16 Division of Revenue. Johannesburg, South Africa.

Oakerson, R.J. (1999) Governing local public economies: Creating the civic metropolis. Oakland: ICS Press.

Peterson, G.E. and Annez, P.C. (2007) Financing cities: Fiscal responsibility and urban infrastructure in Brazil, China, India, Poland and South Africa. Washington, DC: The World Bank. doi: https://doi.org/10.4135/9788132101314

Powell, D. (2012) Imperfect transition – local government reform in South Africa, 1994–2012. In: Booysen, S. (ed) Local elections in South Africa: Parties, people, politics. Bloemfontein: Sun Press.

Reingewertz, Y. (2012) Do municipal amalgamation work? Evidence from municipalities in Israel. Journal of Urban Economics, 72 (3), 240–251. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2012.06.001

Savitch, H.V. and Vogel, R.K. (2004) Suburbs without a city: Power and city county consolidation. Urban Affairs Review, 39 (6) (July), 758–790. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087404264512

Schroeder, L. (2003) Municipal powers and functions: The assignment question. In: Bahl, R. and Smoke, P. (eds) Restructuring local government finance in developing countries: Lessons from South Africa. (pp. 23–61). Massachusetts: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Slack, E. and Bird, R. (2013a) Does municipal amalgamation strengthen the financial viability of local government? A Canadian example. International Center for Public Policy Working Paper. Atlanta, Georgia, United States of America: Andrew Young School of Public Policy, Georgia State University.

Slack, E. and Bird, R. (2013b) Merging municipalities: Is bigger better? IMFG Papers on Municipal Finance and Governance, No. 14, Institute on Municipal Finance & Governance. Ontario, Canada: Munk School of Global Affairs, University of Toronto, Toronto.

Smoke, P. (2001) Fiscal decentralisation in developing countries: A review of current concepts and practice. Technical Report 2. Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations Research Institute for Social Development.

South African Cities Network (2016) State of South African cities report. Johannesburg: South Africa Cities Network.

Tannenwald, R. (1999) Fiscal disparity among the states revisited. New England Economic Review, July/August, 3–25.

Van Ryneveld, P. (1996) The making of a new structure of fiscal decentralization. In: Helmsing, B., Mogale, T. and Hunter, R. (eds) Restructuring the state and intergovernmental fiscal relations in South Africa (pp. 4–24). Johannesburg, South Africa: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung & Graduate School of Public and Development Management, University of Witwatersrand.

Yilmaz, Y., Hoo, S., Nagowski, M., Rueben, K. and Tannenwald, R. (2006) Measuring fiscal disparities across the US states. A representative revenue system/representative expenditure system approach. Fiscal year 2002. Working Paper 06-2. Massachusetts, United States of America: New England Public Policy Center, Federal Reserve Bank of Boston.

Yilmaz, Y., Hoo, S., Nagowski, M., Rueben, K. and Tannenwald, R. (2007) Fiscal disparities across states, in fiscal year 2002. Tax policy issues and options, No. 16, January. Washington, DC, United States of America: Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center The Urban Institute.

FOOTNOTES

1 “The development of segregated local government bodies for Coloureds and Indians followed a separate path from that for Africans. Under the Group Areas Amendment Act of 1962, provincial administrators constituted ‘Local Affairs Committees’ or ‘Management Committees’ in designated Coloured and Indian areas. In their initial phases, these committees were intended to act in a purely consultative capacity in relation to WLAs, which retained administrative control over their areas. These committees would subsequently be granted full local authority status in terms of the criteria set out by provincial administrators in relation to a prescribed range of local issues. Despite their transformation into wholly elected entities, very few attained full local authority, as the majority of the committees status remained mere advisory bodies with little powers beyond granting trading licenses” (Lemon 1992).

2 These district councils succeeded joint structures between local authorities that had been established via the Regional Services Council Act of 1985 and named “Regional Services Councils” (RSCs) and “Joint Services Boards” (JSBs). The main function of the RSCs and JSBs was to operate a regional system for providing “bulk” infrastructure services in larger urban areas, especially poor black areas, as well as some rural areas.

3 Where applicable, these powers were subject to a process that afforded any aggrieved parties or stakeholders the right to appeal decisions by the MDB, and for the MDB to consider such appeals.

4 There was one exception, namely the District Management Areas; i.e. sparsely populated areas such as Kruger National Park which were not under any local municipality, but were governed by a district municipality as spelt out in Section 6 of the Municipal Structures Act.

5 The three tier local government consists of metropolitans (Metros), district municipalities (DMs) and local municipalities (LMs). The DMs overlay a number of local municipalities

6 In addition to metropolitan municipalities, South Africa has the following municipal categories: B1s are municipalities dominated by secondary cities; B2s are municipalities with a large town as its core; B3s are municipalities dominated by small towns, and B4s are municipalities that are predominantly rural.

7 For example, first oval shows an amalgamation of three municipalities (Camdeboo, Baviaans an Ikwezi), which includes a combination of two municipalities (Baviaans and Camdeboo) with a very low revenue base and one (Ikwezi) with a good revenue base. Such an amalgamation may not give viable outcome at the end. Thus the ovals represent examples of amalgamated municipalities, but for clarity not all amalgamations are shown.