RESEARCH and EVALUATION

Assignment of functions to local authorities in Lesotho

Hoolo ‘Nyane

Faculty of Law

National University of Lesotho

Lesotho

Abstract

In Lesotho the adoption of the new constitution in 1993 made provision for local development. These constitutional provisions were only operationalised in 1997 through an Act of parliament (Local Government Act 1997). The question of how functions are assigned between the central and local governments has always been an area of dispute. The Act attempted to demarcate the assignments through the Schedules to the Act which embody the functions of local authorities at various levels – community councils, urban councils and district councils. However, local development and service delivery continue by and large to be undertaken by central government despite the demarcation. The purpose of this paper, therefore, is to critically analyse the challenges of assignment of functions to local authorities in Lesotho. The paper contends that as the assignment of functions is integral to decentralisation in Lesotho, intergovernmental relations and assignment of functions should be incorporated into the country’s constitution.

Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance

Issue 19: December 2016

http://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/ojs/index.php/cjlg

© 2016 Hoolo ‘Nyane. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Citation: Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance 2016, 19: 5449, - http://dx.doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.v0i19.5449

Introduction

There is arguably no aspect of decentralisation since the promulgation of the Local Government Act in 1997, which has been more daunting and complex than the process of assigning functions between central and local governments in Lesotho. This process has not been realised effectively in Lesotho except for a few line ministries that haphazardly conceded to hand some of their functions to local authorities. When the country enacted the Local Government Act, the process of the assignment of functions was short-circuited by annexing two Schedules to the Act which embody the purported functions of local authorities.

This has done little to assist in the decentralisation of certain formerly centralised functions. There are two main challenges with the Schedules. First, they are still too general to guide line ministries on the functions that rightfully belong to the sub-national level. Consequently, line ministries are largely left unguided on what functions to retain and what to relinquish. Secondly, and most importantly, the Schedules do not encompass revenue and expenditure functions. In turn, they have created empty hopes on the side of local government. Most of the developmental functions that have been envisaged remain without resources so that they largely constitute ‘unfunded mandates’. The adoption of the National Decentralisation Policy in 2014 (Government of Lesotho 2014), has injected fresh impetus to the decentralisation reforms in Lesotho. It provides another opportunity to attempt the exercise of assigning functions to local authorities under the broader new policy regime. The purpose of this paper is, therefore, to recast the whole notion of assignment of functions into the current reform processes. By so doing, the paper hopes to lay bare some of the challenges of this exercise in the past, and make some contributions on how it can be improved under the new policy regime.

Background to decentralisation in Lesotho

Decentralisation in Lesotho is arguably as old as the formation of the nation-state in the 19th century. Since then the country has experienced localised forms of democracy associated with traditional leadership under the system of chieftainship embedded in local governance processes (Mahao 1993). This system was disrupted with the advent of democracy in the 1930s when the institution of chieftaincy was gazetted (Machobane 1986), and later in the 1960s when an attempt was made at electing district councils, thereby infusing elective conceptions into the system of local governance. Since then, due largely to changing political situations in the country, local governance has oscillated between traditionalist, elective and appointive constructs.

Thus, Lesotho is traditionally a decentralised state where every village or ward has had a traditional administration of one form or another (Mofuoa 2005). The post-independence institutional designs placed a lot of pressure on traditional administration to the extent that it – perhaps in tandem with all other native processes – showed some signs of inadequacy. The introduction in the 1960s of the elective principle in local governance also confirmed that a new attitude towards local democracy in Lesotho was on the upsurge. However, the concept of democracy could not be sustained, largely because of its rudimentary stage at the time. Instead of re-energising traditional administration, the country introduced the appointive principle in local administration in the late 1980s to early 1990s at a stage when the country was en route to democracy again. The idea of development councils at village and ward levels in the 1990s underscored this particular trajectory.

When the country returned to electoral democracy in 1993, local democracy followed in 1997 when the country re-introduced the elective principle to local governance through the Local Government Act of 1997. There has been widespread disagreement about the model of decentralisation introduced by the

Act. The divergence of views has been whether the country, through this design, was devolving, delegating or de-concentrating functions to local governance. This debate has arisen largely out of a lack of clarity about the powers of the elected councils vis-à-vis the central government. While the Ministry of Local Government expects line ministries to devolve powers based on the Schedules to the Local Government Act, this belief has not necessarily been shared by ministries at central level. Most of the ministries continue to maintain ‘de-concentrated’ presence at district and, at times, community level.

At present, the country operates a local government structure which has four types of local authorities: community councils, district councils, urban councils and a municipal council (Table 1).

Table 1: Types and number of local authorities in Lesotho

| District | No. of District Councils | No. of Municipal Councils | No. of Urban Councils | No. of Community Councils |

| 1. Berea | 1 | 0 | 1 | 8 |

| 2. Butha-Buthe | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| 3. Leribe | 1 | 0 | 11 | |

| 4. Mafeteng | 1 | 0 | 1 | 7 |

| 5. Maseru | 1 | 1 (Maseru City Council) | 1 | 10 |

| 6. Mohale’s Hoek | 1 | 0 | 1 | 7 |

| 7. Mokhotlong | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| 8. Qacha’s Nek | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| 9. Quthing | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| 10. Thaba-Tseka | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| Total | 10 | 1 | 11 | 64 |

Source: Adapted from Lesotho Local Government Act 1997 (as amended)

The community council is the basic unit of local government in Lesotho and number 64 in total. The members of the community council directly represent a single-member electoral division (ED); however, the ED is not necessarily a local government structure despite the fact that it covers a sizeable population in a community council. District councils are indirectly elected and made up of members nominated from every community council in the district. All ten administrative districts in Lesotho have district councils. Urban councils govern the 11 selected urban centres across the country and unlike district councils, are directly elected. The last type of local authority is the sole municipality based in Maseru city.

The challenge with this structure is that it is still not ‘local enough’ (Kapa 2009). The community council which is the basic unit of the structure serves too many villages and some villages struggle to establish efficient relationships with the community council. The ideal situation would be for local government to have a local authority in every village.

Since the return of the country to electoral democracy, two local government elections have been held in 2005 and 2011. Throughout this period, emphasis has been placed on political decentralisation during the preliminary stages in the decentralisation process. Despite the large emphasis placed on ‘political processes’, there are some indications that local government in Lesotho is bracing for the second wave – the stage where local government would be given power to control its own resources, although population sizes differ (Table 2). This stage involves independent mobilisation of resources by local authorities, independent budgetary powers and control of facilities under which they would have the power to impose local taxes and collect local revenues (Hountondji and Fournier 2007) as accounting authorities in their own right. The local government regime in Lesotho has not yet reached this stage but there is every indication that this will soon be realised.

The Deepening Decentralisation Programme by the government of Lesotho in collaboration with European Union (EU), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and United Nations Capital Development Fund (UNCDF), has as one of its key outputs the establishment of a local development fund which will transfer revenue from central government to local government. While doing so, the programme aims to create capacity at the local level to collect, receive and manage revenue. Clearly it would seem that the government has already realised that in order to graduate to this stage certain macro reforms will be necessary. The government is responding by starting the process of developing the decentralisation policy which will be the bedrock for all the reforms.

While the country will be working on its move to the second stage of decentralisation, it will be imperative to concurrently consider the third stage – that of local economic development. This is clearly an advanced stage of decentralisation where there is economic activity at the local level – the regulation of markets, participation of the private sector, economic regulations and frameworks, and production etc. (Hountondji and Fournier 2007). This stage has its own reversals – negative tendencies like corruption, nepotism and cronyism are normally endemic during this period.

Table 2: Present local government structures by area and population

| District | Area (km2) | Population (2006 Census) | No. of Councils |

| 1. Butha-Buthe | 1,767 | 110,320 | 6 |

| 2. Leribe | 2,828 | 293,369 | 14 |

| 3. Berea | 2,222 | 250,006 | 10 |

| 4. Maseru | 4,279 | 393,154 | 13 |

| 5. Mafeteng | 2,119 | 192,621 | 9 |

| 6. Mohale’s Hoek | 3,530 | 176,928 | 9 |

| 7. Quthing | 2,916 | 124,048 | 7 |

| 8. Qacha’s Nek | 2,349 | 69,749 | 5 |

| 9. Thaba-Tseka | 4,270 | 129,881 | 7 |

| 10. Mokhotlong | 4,075 | 97,713 | 6 |

| Total | 30,355 | 1,876,633 | 86 |

Source: Adapted from Lesotho Decentralisation Policy (Government of Lesotho 2014)

The notion of functional assignment

Assignment of functions across various spheres of government is fundamental to any decentralisation programme. It is the precondition for decentralisation and an issue for both federal and unitary states. When a country considers decentralising, the first thing is to decide on the scale of sub-national units, setting organisational structures, and deciding on inter-governmental fiscal relationships (Ferrazzi and Rohdewohld 2009). The UN Guidelines on Decentralisation provide that “legislative provisions and legal texts should clearly articulate the roles and responsibilities of local authorities vis-à-vis higher spheres of government” (UN 2007, C.1.4). Assignment of functions generally happens in countries despite the model or typology of decentralisation. Countries choose to decentralise using various models, the most common of which are delegation, devolution and de-concentration.

There has been little disagreement with regard to the process of delegation. As Cohen and Peterson (1996, p. 11) pointedly argue, delegation refers to the “transfer of government decision-making and administrative authority and/or responsibility for carefully spelled out tasks to institutions and organizations that are either under its indirect control or independent”. In many cases delegation “is by the central government to semi-autonomous organizations not wholly controlled by the government but legally accountable to it”. Clearly, this type of decentralisation is not the one envisaged by the current local government regime in Lesotho. The contest is, rather, between devolution and deconcentration. Devolution is concerned more with the transfer of political power since authority is transferred by central governments to the local level. The sub-national or local authorities to which power has been transferred are governed by locally elected representatives – they are not necessarily agents of branches of central government (Conyers 1983). The process of devolution is normally more straightforward in federal or semi-federal states where the centre is clearly not in charge of the regions or communes. Unitary states like Lesotho do not normally provide good examples of government with devolved powers (Salmon 1999). On the other hand, de-concentration – which is common in British-based local government regimes – is not necessarily based on locally elected political representatives. Power is simply transferred from the centre to the local branches of government, and the centre has direct control over the localised branches (Schou and Haug 2005). This is commonly referred to as administrative decentralisation.

What becomes immediately apparent with the Lesotho design is that it does not fall squarely into either of these two designs. While indeed the local authorities are directly elected, there is still a lot of power and influence from the centre – which makes it hard for this process to be called devolution. The powers of local authorities according to section 106 of the constitution are determined not by the constitution but by central government at its own volition. Thus, by virtue of having locally elected representatives, Lesotho local government design could conveniently be styled semi-devolution – not de-concentration because it is not made up of branches or agencies of central government, strictly speaking. It should be noted however, that despite local authorities being elective in Lesotho they are largely viewed as, or indeed are, agents or branches of central government.

Assignment of functions to local authorities normally focuses on three basic typologies of function – administrative functions, political functions and fiscal functions. Administrative decentralisation mostly relates to human resource, planning and management. It deals largely with the administration of local authorities. Political decentralisation, on the other hand, gives political powers to sub-national levels of government. When a country decentralises political functions, “representative institutions at sub-national level exert some autonomous political role in undertaking functions and managing resources” (Ferrazzi and Rohdewohld 2009, p. 3). These sub-national institutions are oftentimes elected at the national level. The third typology of function pertains to fiscal decentralisation. It relates to assignment of revenue and expenditure functions to the sub-national level. In deciding which functions to relinquish several principles guide countries, such as economies of scale, externalities, equity, heterogeneity of demands etc. However, the widely applied principle in functional assignment is subsidiarity which dictates that the functions or tasks in question should be undertaken by the layer with the smallest jurisdiction that can do so efficiently and effectively (Ferrazzi and Rohdewohld 2009; UNDP 2005).

The state of functional assignment in Lesotho

The nature of the model of decentralisation and the corollary assignment of functions can best be understood from the constitution of the country. Section 106 of the constitution empowers parliament to establish local authorities in order “to enable urban and rural communities to determine their affairs and to develop themselves”. Unlike in other countries where the assignment of powers and functions to various spheres of government is a constitutional matter, the constitution of Lesotho does not necessarily deal with the assignment of functions to local authorities. Assignment of functions is a matter for legislation. The Local Government Act of 1997 is the organic piece of legislation on decentralisation and local governance in Lesotho. The Act establishes political structures in the form of councils that are elected directly by the citizenry. The legislative powers of these councils are limited to making by-laws (s 42) but subject to approval by the minister (s 44). Section 5 of the Act, although it is couched in fairly broad terms, is instructive on the powers of local authorities in Lesotho. Section 5(1) provides that:

...every local authority shall, subject to the powers reserved to or vested in any other authority by this Act or by any other written law, be the authority within its administrative limits charged with the regulation, control and administration of all matters as set out in the First Schedule.

In terms of section 5(2) of the Act, community councils perform exclusively the functions in the Second Schedule. The section is fairly permissive on what the local authorities can or cannot do. The functions are demarcated in terms of the two Schedules attached to the Act in section 5 (see Table 3 below).

Table 3: Assignment of functions to local authorities, section 5 of the Local Government Act 1977

| Schedule | Functions | Competent Council |

| 1 |

|

|

| 2 |

|

|

Source: Schedules to the Local Government Act, No 6 of 1997 (as amended)

There is an advantage in taking this general competence approach in constructing the powers of the local authorities – but there are also disadvantages. The advantage is that local authorities are given sufficient scope to do generally everything within their area of jurisdiction. However, the disadvantage is that when the functions of local authorities are assigned in general terms, it leaves room for misunderstanding and abuse. The net effect becomes stagnation in the process of decentralisation – the central government remain suspicious about the capabilities of the local authorities. Similarly, local governments become beholden to central government about what they can or cannot do. As it could be observed from Table 3 above, the Schedules do not specify the extent to which a local authority can deliver or execute a certain function. For instance, local authorities are empowered to administer education. The Schedules do not necessarily differentiate between various levels of education – university, secondary, primary or pre-school. In the end, the central government retains powers to control, administer and deliver education services in all these levels of education. The same applies with roads, agriculture, and forestry and even water resources.

This general competence approach used in the Lesotho design is normally juxtaposed with ultra vires (beyond legal limits). This approach provides a list of functions that can be executed by local authorities and those that can be executed by the central government with some level of specificity. The net effect is that no sphere of government can encroach into the jurisdictional authority of the other for that will be clearly be ultra vires or beyond the law (Ferrazzi and Rohdewohld 2009). In Lesotho’s design the disadvantage is that there are no clear legal boundaries to prohibit one sphere of government from encroaching into the jurisdiction of the other in as far as service delivery is concerned. The design allows concurrent functional assignment – the assignment of functions in which spheres of government share functions and competences. Concurrency in functional assignment is not necessarily a bad thing when properly managed. Based on the principle of subsidiarity, the two spheres of government can be given competences on one functional area such as roads or agriculture, and the lower level is given actual execution and delivery while the higher level is given regulation and standard-setting.

Another disadvantage with the Schedules, as shown in Table 3, is that they do not assign revenue and expenditure functions to local authorities. While the Act empowers the local authorities to collect revenue and expend it, functions are not assigned accordingly between the two spheres of government. As a result, revenue collection in all its forms still remains the function of central government. The mandates of local authorities, therefore, largely remain unfunded.

Despite this assignment of functions to local authorities by the Schedules, the central government departments have hitherto tenaciously held on to their functions. Central government departments still perform service delivery through their de-concentrated departments in the districts. Thus, this parallelism between local authorities and de-concentrated central government departments has largely stifled local government in Lesotho. Mindful of this reluctance on the side of central government departments, the Minister of Local Government in 2015 identified certain central government ministries and departments and their functions which would be transferred to local authorities within a period of six months, and published the announcement in the Government Gazette, Local Government (Transfer of Functions) Regulations, 2015. Table 4 indicates the ministries and the functions to be transferred. The only problem with this initiative by the Minister, benevolent as it may seem, is that it effectively amends the First Schedule to the principal Act. The Minister purportedly made transfer of functions by regulations in terms of sections 5 and 84 of the principal Act. While the Act empowers the Minister under section 84 to make regulations “generally for the purpose of giving effect to the principles and provisions of this Act”, it does not empower the Minister to amend the Schedules to the Act. That is still the vested function of parliament.

Table 4: Functions to be transferred by selected central government ministries to local authorities

| Ministry | Functional Area | Function to be Transferred |

| Health | Health education and promotion |

|

| Environmental health |

|

|

| Maternal health and child health |

|

|

| Adolescent health |

|

|

| Maternal and child health |

|

|

| Procurement and supply of medicines |

|

|

| Communicable and non-communicable diseases |

|

|

| Health legal frameworks and policy regulation |

|

|

| Health human resource management and information system |

|

|

| Quality assurance |

|

|

| Local Government and Chieftainship Affairs | Land tenure |

|

| Physical planning |

|

|

| Land use planning |

|

|

| Land surveying |

|

|

| Ministry of Social Development | Social assistance services |

|

| Community-based care services |

|

|

| Ministry of Forestry | Forestry development and outreach |

|

| Land management and water conservation |

|

|

| Management of rangeland resource |

|

|

| Ministry of Energy |

|

|

Source: Local Government (Transfer of Functions) Regulations No 138 of 2015

Despite this statutory intervention by the Minister, transfer of functions to the local authorities in Lesotho is still very low. Even in those ministries that are making some attempt to transfer functions, resources such as finances and human resources are still retained by the central government to the extent that transfer of these functions ultimately becomes an exercise in futility.

Overview of fiscal decentralisation in Lesotho

Conceptually, fiscal decentralisation is the concomitant of the now widely accepted wave of decentralisation across the globe. It therefore subscribes to the broader theories of decentralisation whose essence is that decentralisation leads to higher levels of political participation, accountability, administrative and fiscal efficiency (Falleti 2005; Inter-American Development Bank 1994). Countries have differed materially on how they decentralise public financial management. The difference has largely depended on the model of decentralisation which a country proposes. Other countries, mainly federal and semi-federal countries, have opted for much more devolved powers to the sub-national level while unitary states largely maintain vertical uni-polar fiscal relationships between tiers of government. Public financial management responsibilities are assigned to various tiers of government but largely managed through one central system. Irrespective of the model of decentralisation, every country in contemporary country designs has one form of fiscal decentralisation or the other (Faguet 2014).

In essence, fiscal decentralisation means empowering local and sub-national spheres of government to manage their fiscal resources. Due largely to weak local revenue in most instances, fiscal decentralisation has been erroneously equated to transfers from the central government to the periphery. Fiscal decentralisation does not exclusively embody intergovernmental transfers – it is broader. Indeed the modalities of intergovernmental transfers have occupied a significant space in discussions about fiscal decentralisation:

It is also about the extent to which local governments are empowered, about how much authority and control they exercise over the use and management of devolved financial resources, measured in terms of their control over (i) the provision of the basket of local services for which they are responsible; (ii) the level of local taxes and revenues (base, rates and collection); and (iii) the grant resources with which they finance the delivery of local public services (UNDP 2005, p. 2).

In the final analysis, fiscal decentralisation consists primarily of devolving revenue sources and expenditure functions to lower tiers of government (de Mello 2000). The four key tenets of fiscal decentralisation are: 1) the assignment of expenditure responsibilities to different government levels, 2) the assignment of tax and revenue sources to different government levels, 3) intergovernmental fiscal transfers and, 4) sub-national borrowing: local governments can borrow (in a variety of ways) to finance revenue shortfalls (UNDP 2005).

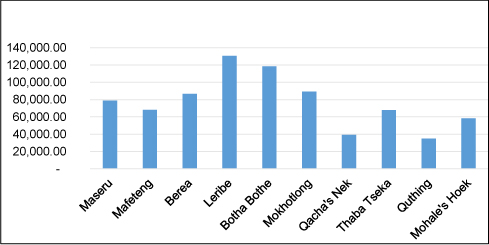

How a particular country assigns these functions across spheres of government has been difficult to resolve for most countries, including Lesotho. However, most countries largely use the principle of subsidiarity. This principle suggests that government functions should be assigned to the lowest level of government that is capable of efficiently undertaking this function (UNDP 2005). For instance, if fines for grazing on a reserved pasture can best be collected by local government than the central government, the principle provides that such a revenue function should be assigned to the local authorities. Similarly, the standard tax revenues such as income tax and other inter-country levies and taxes can best be collected by central government, and should therefore be assigned to central government. In Lesotho, the small amount of revenue collected by local authorities is transferred to the local government. Figure 1 above shows the revenue collected by district councils which in turn is not utilised at local level but transferred to the central government.

Figure 1: Non-tax revenue sources for the year 2013–2014 for district councils

Source: International Monetary Fund (2016)

Admittedly, fiscal decentralisation in Lesotho is still in its infancy and appears to be lagging behind administrative and political decentralisation. However, the Local Government Act (1997) empowers every council to collect revenue and manage it within its jurisdiction. The revenue collection powers of councils seem to be broad enough to include fines and penalties; inter-governmental transfers; rates and taxes (s 47). However, no council has been managing any revenue in Lesotho with the exception of Maseru City Council (MCC), perhaps because of several factors. The first one is that unlike other councils that were only established in 2005, MCC was established in 1989 under the Urban Government Act of 1983. So the MCC is older and much more experienced than others. Secondly and still related to the first, MCC has much more human resources than other councils. As the International Monetary Fund (2016, p. 6) notes:

With the exception of Maseru City Council LAs do not have a substantive source of own revenues. Community and urban councils collect revenues and Maseru City Council collects property rates. Only Maseru City Council retains revenues; all other revenues are transferred to the district councils and subsequently to the central government. Devolution usually entails devolved entities retaining all or part of their own revenues to finance their activities and to set/vary the standards (better roads, more nurses etc.) of these activities. The restriction on the use of autonomous revenues to 1 out of 86 LA’s is unusual. In addition the property tax collection rate for Maseru for 2014–2015 was Maloti 35 (collected)/60(owed) million due to the weak enforcement mechanism available to Maseru City Council.

Despite the historical advantage and the preferential treatment given to MCC on revenue sources, its management of finances does not seem to be any better than other councils. The MCC has not received ‘clean audits’ for the past three financial years at least. For the year ending 31st March 2012, the Auditor General criticised the MCC’s management of its finances stating that “there were serious deficiencies in Council’s accounting and internal controls system during the year” (Auditor General 2016, p. 5).

In that sense, MCC is arguably at the same financial management stage as the other councils. Under the Deepening Decentralisation Programme, which is a five-year (2013–17) project by the Ministry of Local Government undertaken with the support of its development partners, councils are assessed annually on compliance with certain minimum conditions as the qualification criteria for receiving local development grants. In 2015, six minimum conditions and six performance measures were covered. Councils were required to meet the following minimum conditions: i) a District Annual Development Plan for the current financial year (2015/16) approved by council; ii) a district council in place with a schedule of monthly meetings during the previous financial year (2014/15); iii) complete final accounts for the previous financial year produced and submitted to the Ministry of Local Government within three months after the end of the financial year; iv) unqualified reports on audited accounts for previous financial years; v) full-time key district staff with written job descriptions; and vi) an established cash book for the local development grant.

All the councils, including MCC, have not met the requirement of having “unqualified audited accounts” (Government of Lesotho 2015). This state of affairs is indicative of the weak financial management at local level. Hence, the new Decentralisation Policy (2014) laments that:

Financial management in Local Council is manual, making it difficult to create a credible PFM system. The treasury considers the current budgeting process in local councils as below the required threshold for public expenditure. Without a credible budgeting and public expenditure and accounting system, it is difficult to entrust local councils with public funds (Government of Lesotho 2014, p. 5).

For administrative and political decentralisation the country has developed a dedicated legislative framework. With the enactment of the Local Government Act in 1997 and Local Government Elections Act in 1998, the country has considerably enhanced political decentralisation in Lesotho. These two key political decentralisation instruments saw the election of political representatives at local level. In a similar manner, the country advanced administrative decentralisation with the promulgation of the Local Government Service Act in 2008 – thereby creating a separate service for the local level. The Act created the Local Government Service which oversees the recruitment, discipline and dismissal of local service staff. While both political and administrative aspects of decentralisation are yet to mature, there has been considerable progress; however, fiscal decentralisation has been slower to develop. The local authorities still look up to the central government for sources of revenue management, expenditure and budget management. This is largely because there is no statutory or policy framework governing fiscal decentralisation in Lesotho – unlike those for institutional and administrative aspects of decentralisation.

At most, fiscal decentralisation is scattered in various pieces of legislation which has created disharmony and incoherence (UNDP and UNCDF 2013). The Local Government Act 1997 contains some content of fiscal decentralisation. The Act empowers local authorities to generate local revenue in the form of levies, taxes, fines and grants, to manage expenditure of transfers from the central government and even to borrow capital. In this respect the councils are accorded quite broad powers by the Act. In a similar manner, the Public Financial Management and Accountability (PFMA) Act 2011, has some relevance to fiscal decentralisation.

Indeed, the ideal would be to have a dedicated Local Financial Management Act. However, the country is yet to enact a specialised law for local financial management. In the meantime, regulations operationalising both the Local Government Act and the PFMA Act would go a long way to enhance fiscal decentralisation. Notwithstanding this, the country is yet to develop local finance management regulations. In instances of inadequate legal infrastructure the central government is doing a lot to shore up local financial management in areas such as local revenue collection, grant allocation, major expenditure and accountability. Clearly these measures do little to support decentralisation in the bigger scheme of things because effectively the central government continues to control financial movements at the local level. Consequently, the challenges of accountability, absorptive capacity and inefficiency in service delivery still persist. Despite the existence of local authorities and district and sub-district level, the country continues with de-concentrated sub-accountancies at district level. There is little or no structural relationship between the councils and the sub-accountancies for the latter largely collect revenue and manage expenditures directly on behalf of the central government. Perhaps placing these sub-accountancies within the district councils would go a long way not only to enhance local financial management but even to buffer intergovernmental fiscal relations.

The new model proposed by decentralisation policy

In February 2014 the Government of Lesotho adopted the National Decentralisation Policy with the aim of deepening and sustaining grassroots-based democratic governance and promoting equitable local development by enhancing citizen participation and strengthening the local government system, while maintaining effective functional and mutually accountable linkages between central and local government entities. Specifically, the policy provides for the following key strategic reform actions: adoption of devolution as the model of decentralised governance and service delivery; establishment of local governments with autonomy and executive authority development and implementation of the strategic framework for participatory and integrated planning; establishment of fiscal decentralisation and prudent public financial management; development of a framework for exercising local autonomy and intergovernmental relations (Government of Lesotho 2014). The policy introduces a set of decentralisation reforms based on devolution. Whether devolution is an appropriate model for Lesotho as a unitary state remains to be seen, but what is clear about the new decentralisation policy is that it proposes a decentralisation dispensation where there is mutual respect between spheres of government and local autonomy. About nine principles are upheld by the policy with a view to envisage a much more autonomous local government. Those principles are participation, subsidiarity, separation of powers, local autonomy, non-subordination, government as a single system or entity, recognising diversity within uniformity, inclusive governance and accountability.

The policy is not specific on the model of assignment of functions, but it can only be deduced from the principles of the policy that local autonomy, a subject which has haunted decentralisation in Lesotho for a very long time, is central to the newly envisaged dispensation. The policy provides that “the government will devolve functions, responsibilities and resources relating to service delivery to local governments to the fullest extent possible” (Government of Lesotho 2014, p. 15). The policy makes a general division of responsibilities between central government and local government as thus:

Under devolution, line ministries in Central Government shall have responsibility for initiating and formulating policies and national strategies, work with local governments to set targets and prepare sectoral budgets, and provide technical support and monitoring of the implementation processes. Local Governments, on the other hand, shall be responsible for implementing national policies and strategies through local development plans, taking into consideration their unique local needs, priorities and resources (p. 15).

The policy broadly attempts to separate the competencies of the two spheres of government in that it reposes policymaking in central government and implementation in local government. This division is too simplistic and does not regard the possibility of concurrency of functions between the two.

Conclusion

The foregoing discussion highlights that the subject of assignment of functions to local authorities in Lesotho continues to be a fairly complex subject which will haunt decentralisation for quite some time. Assignment of functions to sub-national structures is essential to any decentralisation project which in turn becomes the key pillar of constitutional democracy. As it has been established, local government is not the integral theme of the constitution of Lesotho. Section 106 of the constitution only cursorily leaves it to parliament to establish local authorities. The weakness with this approach is that the separation of local and central spheres of government is a constitutional issue. Thus, the lofty principles identified in the Decentralisation Policy can gain better traction if they are elevated to constitutional status so changing the balance of power between central and local government. In that sense, assignment of functions would not depend on central government but on the constitution itself. This particular approach is vindicated by what has happened in Lesotho since the election of local authorities in 2005 under the Local Government Act 1997. Despite the two Schedules to the 1997 Act assigning functions to local authorities, no functions have been concretely transferred from central government to local level. Central government ministries still tenaciously hold on to those functions. Consequently, the Minister of Local Government in 2015 gazetted certain functions to be transferred by selected ministries. There are two problems with this approach; firstly, it is selective, affecting only a few ministries. Secondly, the Minister adds new functions on top of the ones already assigned through the Schedules to the Act. This is ultra vires as the Minister does not seem to have powers to change, vary or add to the schedules to an Act of parliament. Perhaps that is why central government is divided on that aspect.

Furthermore, it is apparent that the assignment of fiscal functions to local authorities is the most difficult part in the whole exercise of transferring functions to local authorities. It has been demonstrated above that with the exception of MCC, local authorities do not necessarily collect and manage local revenues. All the revenues collected locally are remitted to the centre. The central government in turn makes capital and recurrent transfers to local authorities. The annual assessments undertaken by the Ministry of Local Government in collaboration with development partners reveal a very weak state of fiscal decentralisation in the country. It is herein recommended that the country should have specific fiscal decentralisation law. The current fiscal decentralisation legal framework based on the Public Financial Management and Accountability (PFMA) Act, 2011 fails to adequately guide both spheres of government on fiscal decentralisation. As the International Monetary Fund (2016) pointedly argues:

Implementing fiscal decentralization in a devolved local government form will require, in addition to fiscal policy and legislative considerations, the redesign of local authority PFM systems. Specific issues that need to be addressed include: revision of Local Council PFM systems; where necessary aligning these PFM system with Central Government planning, budgeting, performance monitoring and reporting cycles.

Equally, the overhaul of the Local Government Act of 1997 following the adoption of the Decentralisation Policy (Government of Lesotho 2014) is a welcome development. The new Local Government Bill proposes to take the functions out of the Schedules to the Act into the Regulations. While the Bill proposes to deepen decentralisation in the country, it is criticisable for taking the functions from the Act into Regulations. That is tantamount to watering-down the provisions. Functional assignment is central to decentralisation and as such deserves space at constitutional level. With the mooted constitutional reforms, the country should recast central–local relations in the new constitution.

References

Auditor General. (2016) Audit report on the annual financial statement of Maseru City Council for the year ending 31st March 2016. Maseru: Auditor General Office.

Cohen, J.M. and Peterson, S.B. (1996) Methodological issues in the analysis of decentralization. Available at: http://www.cid.harvard.edu/hiid [Accessed 28 May 2013].

Conyers, D. (1983) Decentralization: the latest fashion in development administration? Public Administration and Development, 3 (1), 97–109. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.4230030202

De Mello, L.R. (2000) Fiscal decentralization and intergovernmental fiscal relations: A cross-country analysis. World Development, 28 (2), 365–380. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(99)00123-0

Faguet, J. (2014) Decentralization and governance. World Development, 53, 2–13. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.01.002

Falleti, T.G. (2005) A sequential theory of decentralization: Latin American cases in comparative perspective. American Political Science Review, 99 (3), 327–346. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055405051695

Ferrazzi, G. and Rohdewohld, R. (2009) Functional assignment in multi-level government: Conceptual foundation of functional assignment. Eschborn: Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ).

Government of Lesotho. (1993) The Lesotho Constitution (Commencement) Order No. 5 of 1993, Commencing the Constitution of Lesotho (as amended). Maseru: Government Printer.

Government of Lesotho. (1997) Local Government Act (as amended) of 1997 (Act No. 6). Maseru: Government Printer.

Government of Lesotho. (1998) Local Government Elections Act No. 9 of 1998. Maseru: Government Printer.

Government of Lesotho. (2008) Local Government Service Act No. 2 of 2008. Maseru: Government Printer.

Government of Lesotho. (2011) Public Financial Management and Accountability (PFMA) Act, 2011. Maseru: Government Printer.

Government of Lesotho. (2014) National decentralisation policy. Maseru: Government Printer.

Government of Lesotho. (2015) Local Government (Transfer of Functions) Regulations. Maseru: Government Printer.

Hountondji, M.M. and Fournier, C. (2007) Local authorities financial and institutional management system: LAFIAS, a support tool for decision making. New York: UNCDF.

Inter-American Development Bank (1994) Economic and social progress in Latin America: 1994 report. Washington, DC: Johns Hopkins University Press for the Inter-American Development Bank.

International Monetary Fund. (2016) Report on the Kingdom of Lesotho: Fiscal decentralization. Maseru (unpublished).

Kapa, M. (2009) Lesotho’s local government system: A critical note on the structure and its implications for service delivery. Maseru: Transformation Resource Centre.

Machobane, J. (1986) The political dilemma of chieftaincy in colonial Lesotho with reference to the administration and courts reforms of 1938. ISAS Occasional Paper No.1. Roma: ISAS.

Mahao, N.L. (1993) Chieftaincy and the search for relevant constitutional models in Lesotho. Lesotho Law Journal, 9 (1), 107–148.

Mofuoa, K.V. (2005) Local governance in Lesotho: In search of an appropriate format. EISA Occasional Paper Number 33, June. EISA.

Salmon, P. (1999) Vertical competition in a unitary state. Document De Travail. Université de Bourgogne. LATEC.

Schou, A. and Haug, M. (2005) Decentralization in conflict and post-conflict situations. NIBR Working Paper No 1. Oslo: NIBR available on http://www.gsdrc.org/document-library/decentralisation-in-conflict-and-post-conflict-situations/ [Accessed 15 November 2016].

United Nations. (2007) International guidelines on decentralisation and the strengthening of local authorities. Nairobi: UN-Habitat.

United Nations Development Programme. (2005) Fiscal decentralisation and poverty reduction. New York: UNDP.

United Nations Development Programme & United Nations Capital Development Fund. (2013) Diagnostic assessment of decentralisation in Lesotho. Maseru, Lesotho: UNDP.