Property rating potentials and hurdles: what can be done to boost property rating in Ghana?

Elias Danyi Kuusaana

University for Development Studies

Wa, Upper West Region

Ghana

Abstract

Population growth in many of Africa’s towns and cities has outpaced local authority capacity to provide efficient management, infrastructure and financing. There is already debate over the capability and capacity of urban local governments to provide basic services to a growing population, due to budget constraints and inability to raise the required local-level revenue. This paper looks at how the potential of property rating can be harnessed to generate the bulk of revenue needed for local-level development, despite the huge default rates across Ghana. Focusing on Wa Municipality as a case study, the study finds that the major hurdles to property rating are poor property data systems, political interference, non-enforcement of the law, low budget deficit in financing revaluation, insufficient staffing, and insufficient technical capacity of the few staff available at the municipal valuation and rating divisions. Despite these constraints, however, field data still indicates that property rating in Ghana, and especially in Wa Municipality, can generate up to 30% of local government revenue needed. This is conditional on streamlining current challenges and improving resources for the rating and valuation units. There is extensive non-payment of property rates in Wa Municipality due to lack of awareness of the purpose of this tax, of how to pay and of the penalties for defaulting payees.

Key words: property rates, local government, decentralisation, Wa Municipality.

Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance

Issue 16/17: June 2015

http://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/ojs/index.php/cjlg

Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance 2015. © 2015 Elias Danyi Kuusaana. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Citation: Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance 2015, 0, 4495, http://dx.doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.v0i0.4495

Introduction

Decentralisation, an approach to governance aiming to bring government close to the people and improve economic efficiency and accountability, is here to stay (Kelly 2000; FAO 2002: 28). However, an efficient and reliable local government revenue system is an essential pre-condition for successful fiscal decentralisation (Olowu and Wunsch 2003). Raising local-level revenue is critical to ensuring the smooth running of local government systems. However, local governments in developing countries have been unable to secure adequate funding from central governments, or to generate it locally. In sub-Saharan Africa they continue to battle resource constraints in their efforts to spearhead local development, function properly and provide proactive governance to local people. In the Ghanaian context, both Okrah and Boamah (2013) and Davey (2003) argue that local governments need fiscal empowerment in order to attain maximum efficiency.

Local governments have several possible sources of local-level revenue, and key among these is property taxation. The term ‘property taxation’ strictly speaking includes taxes on personal property such as inventories, automobiles and business equipment; however it is also used more generally to refer to the far more extensive system for taxation of land and buildings (Youngman and Malme 1994: 10). Property rates, as an annual tax on the ownership or occupation of immovable property (ie land and/or buildings), are an important source of local government revenue. The unique feature of property rating as a tax is that the local government decides how much revenue it seeks to obtain from property rates, and then distributes the liability across all rateable properties (Emeny and Wilks 1984). Examples of property taxes include: property rates, rent income tax, stamp duty, gift tax, inheritance tax, capital gains tax, and other levies premised on income from the sale, use of, acquisition of and alienation of immovable property (Franzsen 2003). Property taxes are popular ‘because they produce reliable, stable, independent revenue for the governments closest to the people and there is no clearly superior alternative for providing fiscal autonomy’ (Mikesell 2003).

There is a growing sense that local governments throughout the world are maturing (Bahl 1999) and much development discourse recommends bringing governance closer to the people. Keith and McCluskey (2004) claim that local governance will lead to the inclusion of local needs and conditions into national planning and public service delivery policies. It is also often argued that decentralisation will enhance the efficiency, effectiveness and legitimacy of central government programmes at grassroots level (McCluskey and Bevc 2007). Decentralised governments no longer require central government directives to assist with the provision and delivery of local services and to contribute to local-level sanitation, security, and social and physical infrastructure development (Bird and Slack 2003). Increasing urbanisation has further pressured local governments to provide physical infrastructure and social amenities for the exploding urban population. Jibao (2009) argues that as local governments begin to assume responsibility for local-level development, so they should also assume more responsibility for financing these services by generating local-level revenue from citizens – thus bringing governance closer to voters and thereby improving government efficiency, effectiveness and responsiveness. It is held that local governments which promote broad-based local participation in governance are more responsive to local needs and to tackling local challenges (Baldersheim et al 1995).

However in the Ghanaian context, to discharge these responsibilities the country’s metropolitan, municipal and district assemblies (MMDAs) require a significant, reliable financial resource base capable of resolving their recurrent annual budgetary constraints. Currently, the government of Ghana appears too cash-strapped to address all the financial needs of local governments. There have been many recent reports of central government grants to local government units being erratic, in arrears, and beset by serious managerial challenges, which compounds the challenges faced by local governments (Banful 2007). It is against this backdrop that MMDAs are encouraged to pursue all legally possible means of generating local-level revenue for their budgetary requirements and to finance local-level development.

The main legislative bases for property rating in Ghana are the Immovable Property Rate Amendment Regulations (LI 1049) and the Local Government Act 1993 (Act 462). Specifically, Section 94 of Act 462 makes MMDAs the rating authorities in their areas of jurisdiction. Act 462 assigns them powers of determining, levying and collecting property rate in Ghana. Section 95 (1) states that: ‘A district assembly (DA) shall make and levy sufficient rates to provide for that part of the total estimated expenditure to be incurred by it during the period in respect of which the rate is levied and which is to be met out of money raised by rates.’

Dependence on central government grants for local development is dangerous in Ghana because of recurrent national budget deficits. However, over the years grants from central government have formed the bulk of the local government finances, even though property taxes are considered appropriate to facilitate financial autonomy at sub-national levels (Bahl and Martinez-Vazquez 2006). Ghana’s central government District Assemblies Common Fund (DACF), which comprises just 7.5% of the total annual national revenue, is shared between all 216 district assemblies in Ghana according to a formula based on factors such as ‘need’, ‘responsiveness’, ‘service pressure’ and ‘equality’ (Banful 2007). However, this funding is never adequate for their ever-expanding financial requirements. It is therefore prudent for district assemblies to identify further sources of revenue and to ensure the efficient collection of identified revenue so as to supplement DACF allocations. Act 462 empowers MMDAs to raise revenue to support local development projects from sources such as market tolls, licences, fees and property rates. These avenues are known as ‘internally generated funds’ (IGF). Within IGF, property rates are the surest source of revenue and are a balancing factor in district assembly budgets (Asiama 2006)1.

Unfortunately, this potential ‘gold mine’ that property tax is for MMDAs has been underexploited, and many MMDAs merely await central government support to finance their development aspirations. Inefficiencies and ineffective collection in the tax administration system have also masked the potential of property rates in Ghana. Even more fundamentally, most Ghanaians have lost all enthusiasm to pay property rates, because over the years local governments have been unable to show any justification for it, however small, in the form of social services and physical infrastructure. Hence, though it has huge potential, property rating in Ghana is beset by extensive non-payment.

This paper focuses on urban property taxation as, according to Di John (2009: 13), the role of land and property taxes is especially important in urban areas as local governments seek to cover the cost of decentralisation refforms, and property taxation remains one of the most underused forms of taxation in developing countries, which could potentially provide fund the urban infrastructure investment which is central to improving the production and export capacity of light manufacturing plants, many of which are located in urban centres. Property taxes not only provide an impetus to create urban property databases – which could benefit urban planning as well as municipal taxation – but also provide one of the few mechanisms through which progressive taxation can be developed at local level. Di John also suggests that property taxation contributes to making property rights more secure.

In a recent study, Boamah (2013) looked at property rating in Ghana’s Offinso South Municipality and documented various constraining factors. However, this study was undertaken in an urban municipality where a vibrant property market exists. Petio (2013) studied Ghana’s Upper East region, which has similar characteristics to the Upper West Region. However, his study concentrated on the role of the national Land Valuation Division (LVD) and does not consider the roles and constraints of other institutions concerned with property rating in Ghana.

The present study examines the potentials and challenges of property rating in Ghana using Wa Municipal Assembly as a case study. In particular, it seeks to examine public perceptions of property rating and why the public is not keen to pay the tax. The potential contribution of property rates to public finance in Wa Municipality is also assessed.

The following sections of the paper will discuss the sources of local government revenue, the evolution of property rating in Ghana, the study methodology, and challenges to effective property rate mobilisation, before concluding and offering some policy recommendations.

Sources of local government revenue in Ghana

According to Meinzen-Dick et al (2008), three broad types of decentralisation can be identified, depending on the functions being transferred from central to local government. In their view, administrative decentralisation transfers responsibility for administrative procedures; political (democratic) decentralisation delegates electoral and legislative authority; and financial decentralisation transfers both resources and responsibility for financing government services. When only responsibility or authority is transferred, but not resources or local accountability, the process is termed ‘deconcentration’ (ie administrative decentralisation). When responsibility, authority and resources are transferred, but accountability still resides in the centre, the process that has occurred is ‘delegation’. When there is transfer – by law and other formal actions – of responsibility, resources and accountability, the result is ‘devolution’ (Adamolekun 1999).

Ghana’s decentralisation can best be described as devolution, since it seeks to transfer both power and resources to local governments to facilitate development at community level. The major source of revenue remains central government transfers through the DACF (District Assemblies Common Fund), even though local governments are empowered to raise their own locally-generated revenue under the Local Government Act 1993 (Act 462).

Locally-generated revenue has become a much greater source of revenue in developed countries than developing countries, notwithstanding its huge potentials (Bird and Slack 2003). According to Braid (2005), local tax revenue contributes 100% of local revenue in Australia and Ireland, 99% in the United Kingdom, 93% in Canada and 72% in the United States. Local property tax generates more than 2% of developed countries’ GDP (Bahl 2009). Yet, despite the immense contribution of property tax in developed nations, its potential is underexploited in developing and transitional countries, where it constitutes less than 4% of all tax revenues, and averages 0.42% and 0.54% of gross domestic product (GDP) of developing and transitional countries respectively (Bahl 2009).

For example in Kenya, locally-generated revenue forms only 22% of total recurrent revenues of local authorities, 1.3% of total government tax revenue, and 0.3% of GDP (Kelly 2000). According to Chitembo (2009), revenue sources for local governments in Zambia included 59% from local taxes, 18% from fees and charges, 20% from other receipts, and 3% from national support.

Financial resources are essential for local governments to provide the services that are legally required, and to implement their annual budgets. In the early years of Ghana’s current local government system, the need for locally-generated revenue was emphasised by various committees (the Coussey Committee, the Watson Commission, the Philipson Committee and the Sireboe Committee). These committees’ recommendations included the need for a financially viable local government unit, the abolition of basic rates and the introduction of district level taxes. However, not all these recommendations have been implemented as they were not deemed viable ways to finance local governance in a developing Ghana (Asare 1986).

District assemblies in Ghana are mandated with extensive powers and functions under the 1992 Constitution and the Local Government Act 1993 to provide political and administrative guidance and to supervise other administrative authorities in their district, as well as take responsibility for overall development in their areas of jurisdiction (Petio 2013). Section 10 of the Act empowers them with three sources of revenue: the DACF, ceded revenue, and locally-generated revenue raised through local taxation, rents and levies. The DACF is the main source, providing a constitutionally guaranteed minimum share of government revenue to local government (not less than 5%, and currently 7.5%). Ceded revenue refers to revenue received from a number of lesser tax fields that central government has ceded to district assemblies. Ceded revenues are collected by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), which is now part of the Ghana Revenue Authority, and transferred to district assemblies via the Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development. Examples of ceded revenue include entertainment tax, casino levies, betting tax, gambling tax and daily transport tax. Finally, there is locally-generated revenue, collected through property rates, basic rates, fees, fines, licences, rents from municipal properties, ground rents emanating from ‘stool’ (royal and tribal) land, and royalties from timber and mineral revenues. This study however concentrates on property rates, using evidence from Wa Municipality to assess their potential to generate revenue for local governments.

Evolution of property rating in Ghana

Prior to independence in 1957, property rates in what was then called the ‘Gold Coast’ were known as ‘ntokura tow’ (literally: ‘window tax’). This tax was proportional to the size of the building: the bigger the building, the greater the number of windows and hence the higher the tax. Rate assessment officials simply counted the number of windows in a house and multiplied it by a basic figure to determine the levy to be paid, but such an arbitrary method raised concerns. For example, it was argued that smaller houses with many windows for efficient ventilation could unfairly be paying more than bigger houses with fewer windows. It was also pointed out that the tax should be targeted not at windows, but buildings – according to their sizes and values.

These genuine concerns led to the introduction of the Municipal Council Ordinance 1951 and marked the beginning of the present rating system in Ghana. Under the Ordinance, four municipalities – Accra, Kumasi, Cape Coast and Sekondi-Takoradi – were empowered to impose a rate on buildings with annual rental values2 (ARVs) over six pounds. In 1954, the Local Government Ordinance was passed to similarly empower urban and local councils, again using ARVs as the basis for assessment. The Local Government (Immovable Property Rate) Regulations 1954 prescribed the method of assessing immovable property value and defined rateable premises as any house, hut structure, shed or roofed enclosure, whether used for the purpose of human habitation or otherwise. The rateable value was assessed as 10% of the replacement cost3 (RC) of the premises.

After independence in 1957, Ghana took the unique step of asking the United Nations (UN) to help it develop a uniform and workable system for immovable property rating and valuation. Following a review of Ghana’s existing systems, the UN’s representative recommended that replacement cost, rather than annual value, be used to calculate property rates. The reasoning was that this method was simpler and easily applicable to both cities and villages. He also recommended that land per se should not be rated, as it was already subject to ground rent.

Methodology

This study is an extract from previous studies conducted by the author in partial fulfilment of an MSc degree at the Technical University of Munich. It uses a case study approach featuring both quantitative and qualitative research methods. Taking Wa Municipality as a case study, primary data was obtained via questionnaires from 96 property owners (both owner-occupiers and landlords) and eight rate collectors from the municipal assembly. Interviews were also held with 13 officials drawn from the Wa Municipal Assembly, and the Land Valuation, Public and Vested Land and Survey and Mapping divisions of the Lands Commission. Finally, field observations were undertaken to obtain first-hand impressions of realities on the ground. The stratified sampling technique was used to select the properties and property owners for the study, while the purposive sampling method was used to select key informants for interviews. Tools employed in gathering primary data included semi-structured interviews, observation and closed questionnaires. Secondary data was obtained from policy papers, historical accounts, reports and legislation relating to property rating, decentralisation and good governance in Ghana.

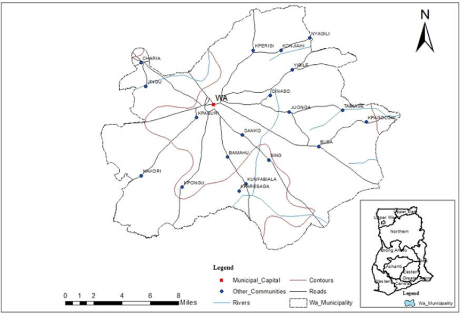

Figure 1: Map of Ghana showing Wa Municipality and some outlying communities

Source: Author’s Map, 2014

Wa Municipality is the political capital of the Upper West Region of Ghana, located in the north-west of the country (Figure 1). The municipality was established in 2004 under Legislative Instrument (LI) 1800. It was created from the previous Wa District, which was sub-divided into Wa Municipality, Wa-West District and Wa-East District. The municipality is located in the south of the region with an area of approximately 234.74 km2 (Wa Municipal Assembly, 2012). In 2004, the population of Wa Municipality was 98,675 at a density of 420/km2. It has since grown to 107,214 people at a density of 456/km2. Although in 2000 some 30% of the population was already urbanised, only the city of Wa was a designated urban locality. However, the 2010 Population and Housing Census reported a total urbanised population of 71,051 - 66% of the municipality’s total population. This compares with a national urbanised proportion of 51%, and a regional urbanised proportion of 16%. This implies that Wa Municipality alone accounted for 62% of the region’s urbanised population in 2010.

Wa Municipality is also reported as having an urban population growth rate of 4% as compared to the national urban growth rate of 3% (Wa Municipal Assembly 2012; Ghana Statistical Service 2005, 2012). The annual rates of population growth in Wa Municipality were 4%, 3.7%, and 3.8% respectively in the periods 1960-70, 1970-84, and 1984-2000 (Ghana Statistical Service 2005). The main inhabitants of the municipality are the Waala and the Dagaaba ethnic groups, and land use is primarily agricultural in rural areas and residential in urban and peri-urban areas. Figure 1 shows the location of Wa Municipality together with some of the peri-urban communities that will be discussed subsequently.

The main type of housing in the municipality is single-storey compound, with a few self-contained houses in peri-urban and developing residential areas. There are also a few higher buildings in Wa town. Building materials used include sandcrete blocks, corrugated aluminium or zinc roofing sheets, and tiles. However, in older residential areas atakpame (mud-house) housing stock dominates. Building materials here include red earth, sticks and thatch. The people of Wa are predominantly farmers and traders. Subsistence agriculture employs about 65% of the population. There are also small-scale agro-industrial crops such as shea-nut, cotton, soya beans and dawadawa, which could potentially become agro-industries. Residents’ activities include shea-butter extraction, pito brewing, pottery, weaving, dressmaking, soap-making, groundnut oil extraction, blacksmithing, carpentry, vehicle repairs and other artisan activities (Regional Planning Profile 2006).

Problems of property rating affect all 216 of Ghana’s MMDAs, to varying degrees. As property rating is generally confined to urban areas in Ghana, this study concentrated on Wa Township. Wa is both a municipal and regional head town. Since gaining municipality status in 2004, Was has experienced rapid urbanisation and remains the hub of administrative, economic and social activities in the Upper West Region. The area also lacks satellite towns to absorb some of the growing population. These circumstances have resulted in increasing pressure on the municipal assembly for provide social services and infrastructure.

Wa Municipality is a good case study subject for property rating and governance because it presents numerous opportunities for strengthening its property rating. Following the establishment of the University for Development Studies (UDS) and a Polytechnic in Wa, several housing developments have sprung up, raising the potential of increased property tax take. Most of these are rented to students and are of high quality. As commercial ventures, they are a good target for property rating. However, increasing property tax income may prove difficult until the structure of property rating is reviewed and re-based, on principles of good governance, improved efficiency and tax compliance.

The potential of property rates as a source of municipal finance

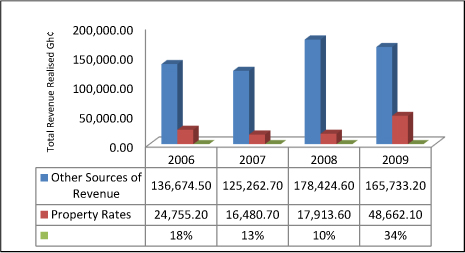

Nationally, property rates contribute less than 2% of local government revenue. According to the Government of Ghana’s 2011 Budget, property rating contributed 0.03% of GDP in 2010. According to Kwakye (2010) as cited by Boamah (2013), property rates constituted 0.21% and 0.19% of Ghana’s GDP in 1997 and 1999 respectively. In Offinso municipality property rates amounted to less than 9% of local government revenue between 2005 and 2009. However, in Wa Municipal Assembly (WMA), property rates now form a significant source of public finance. Figure 2 compares WMA’s total revenue from property rates to revenue from all other sources. In 2006, property rates formed 18% of WMA’s revenue.4 This fell to 13% in 2007, and further to 10% in 2008. However, in 2009 the assembly was able to secure a huge increase following successful claims against MTN, a local telecoms giant, for outstanding rates on their telecommunication masts and properties in the municipality. This boosted property rates’ share of WMA revenue to 30% for the year. The MTN example suggests that even more revenue can be realised with management commitment, investment in its rating unit, and the resolution of persistent rating challenges.

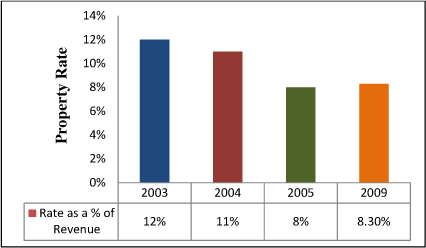

This trend contrasts with similar studies in Accra. As reported by Adem and Kwateng (2007), in 2003 Accra Metropolitan Assembly (AMA) generated 12% of its total revenue from property rates. In 2004 and 2005, the proportions were 11% and 8% respectively of total internally generated funds. The AMA is clearly not generating rating revenue at its full potential, for a number of reasons. Firstly, it has failed to undertake revaluation exercises to capture newly built properties for rating as well as uprate out-of-date rating values (which were last indexed in 1995). Secondly, it does not enforce the law against property owners who fail to pay, because the procedures involved are cumbersome and tedious. Finally, the property rate does not cover all properties adequately.

Figure 2: Comparison of Total Annual Revenue with Property Rates Collected (Gh¢)

Source: Wa Municipal Budgeting Unit, 2010

It is useful to put the statistics from Figure 2 into a broader national perspective. In 2011, Ghana’s National Budget revealed that property rating accounted for 15% of total IGF in Tema (Tema Municipality), 9% in Sekondi-Takoradi (Sekondi-Takoradi Metropolis), 8.3% in Accra (Accra Metropolis), and 6.3% in Kumasi (Kumasi Metropolis).

In the case of Accra Metropolis, the proportion of IGF coming from property rates has declined since 2003 – from 12% in that year, to 11% in 2004 and 8% in 2005. By 2009 the percentage had improved minimally to 8.3%. The widening gap between projected and realised revenues has been attributed to various challenges facing the metropolis, including high levels of property tax non-payment. Details of property rates for Accra Metropolitan Assembly (AMA) are summarised in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Property Rate as a Percentage of Total Annual Revenue for Accra Metropolitan Assembly

Source: Author, 2010 (figures compiled from the Budget of Ghana 2011)

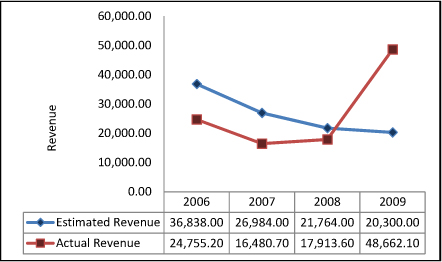

In Wa Municipality, actual revenue collected from rates, as opposed to projections, has also varied. Between 2006 and 2008 actual collections were less than annual projections: 33% less in 2006, 39% less in 2007, and 18% less in 2008. In 2009 however, collections exceeded projections due to the success in reclaiming outstanding rates from MTN. This has led the Wa Municipal Rating Unit to shift concentration from private property owners to corporate organisations and commercial properties.

The trends discussed above and actual funds collected are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Property Rates Collected for the Period 2006-2009 in Wa Municipality (Gh¢)

Source: Municipal Budgeting Unit, 2010

Challenges to effective rate revenue mobilisation in Ghana

From the data collected, the following main challenges were identified to property rating: poor cadastre and property registry systems; defective property value assessment and methodologies; difficulties with collection; lack of community support for how revenue is spent; and uncoordinated institutional and tax administrative structures.

Poor cadastre and property registry system

A fiscal cadastre, according to Whitall and Barry (2004: 2), ‘is an official inventory of land parcels that provides the necessary information to be able to determine the value of property (land and/or improvements) for the purposes of taxation’. The fiscal cadastre forms the information base for property taxation in every country, in the form of an electronic, digitised or paper-based map. A key problem affecting the efficiency and effectiveness of property tax administration in most developing countries is poor record-keeping. According to Mathur et al (2009), the first determinant of revenue performance is the percentage of properties that are on the municipal tax register; this drives the percentage of properties that are assessed for tax purposes, and hence the percentage of tax-paying properties. In their study of India, Mathur et al (2009) found that the absence of a formal count of properties for the purposes of property taxation was a major handicap in accurately estimating property tax potential.

Property tax registers are incomplete across most developing countries – including Ghana – with virtually no reliable estimate of the number of properties in the jurisdiction of local governments. Most cities and towns in Ghana are not covered by comprehensive cadastres. Even the few areas with cadastres are not regularly updated so most are obsolete. This could be one reason why many local taxpayers have successfully evaded property taxes. In Wa Municipality the most recent master, divisional and block plans date as far back as 1997, while in Accra they date back to 1995. In many instances, also, taxable properties are not adequately described in the fiscal cadastres and property owners may be difficult to identify.

There is also a common misunderstanding of the term ‘property’ for the purposes of property taxation (Mathur et al. 2009). As expressed by Kitchen (2003: 2): ‘The assessment roll should include the address of the property, its owner, building and lot size in square metres or hectares, the age of the building and information on renovations or improvements.’ Unfortunately this is not the case with cadastres in Wa Municipality, which show only plots and plot numbers for various residential areas without any detailed description of the property itself.

Property value assessment and methodologies

Methodologies used in calculating rateable values differ from country to country. Methods such as market value, rental value, site value or depreciated replacement cost are the most common. Generally, however, property valuation is subjective – even if it originates from an informed professional such as an estate valuation surveyor (EVS). Depending on the method used and the professional and technical competencies of the EVS, taxable property values may differ greatly. Furthermore, the choice of valuation method a particular country or local government authority adopts may pose its unique difficulties. Surmounting these challenges and developing realistic property values will be a great step towards ensuring equity and fairness in property taxes. Unfortunately Wa Municipality, like most local governments in developing countries, lacks the requisite human and logistical resources to regularly revalue and update its property list. Qualitative data from the present study indicates persistent budget deficits for financing revaluations in the municipality. Consequently, there is wide variation in annual property values and these do not enable substantial revenue generation through property tax. Adem and Kwateng (2007) found a similar situation in Accra Metropolis. According to the Wa Municipal EVS (qualitative interview, 2010), the municipal Valuation Division has only three staff. It also lacks adequate space, basic office equipment, transportation and attractive rates of remuneration. The work is often carried out with harsh and unyielding property owners and with minimal support from Wa Municipal Assembly.

Difficulties with property rate collection

This study also found property rate mobilisation to be affected by several billing and collection issues. For example, demand notices can be either posted or hand-delivered, depending on resources available. In Wa Municipality the tax bill is hand-delivered by authorised local revenue collectors and property owners either pay them directly, or pay at the municipal revenue unit by a specified date, which is a time-consuming process. Property rate mobilisation is also affected by poor rating information. There are also growing concerns about the non-enforcement of default penalties due to creeping ‘politicisation’ of the system and manipulation of the system by elites at community level.

A particular problem in Wa Municipality is the lack of cooperation in rate-payment by indigenous communities in Wa Township, as corroborated by Adem and Kwateng (2007: 8): ‘Penalty for non-payment is often a much politicised issue, which few tax administrators are willing to implement. Also, legal cases arising from non-payment can drag on for prolonged periods of time.’ For most parts of the municipality, but especially in the indigenous Waala sections, securing payment is very problematic. Properties are mostly in clusters without clear boundaries, and families own properties jointly. These characteristics make property valuation extremely difficult. Differentiating between ownership and occupation is tricky, leading to complexities in rating assessment. Interviews also indicated that in a number of cases some family members resist rate payment by other family members, fearing that this will be construed as evidence of ownership of a property. There is also an erroneous belief that indigenous people are not liable for the tax. High of levels poverty and poor housing quality create additional challenges.

Lack of community support for how revenue is spent

According to Adedokun (2006: 3), the ‘local government system, as the third tier of government, deserves adequate finances to enable it to cope with the numerous developmental activities within its jurisdiction.’ It is generally believed that local governments are better able to identify and tackle priority societal problems in their area, but to do this they need locally generated revenue and financial support from central government. In Wa Municipality, local needs have outpaced local resources. There is particular difficulty in reconciling property taxes collected and the social services provided to the community. This is one reason why most citizens refuse to honour their property tax obligations. It is very cumbersome and expensive to own a house in Ghana, where direct government support in housing provision for the poor is limited. Property owners face many difficulties in constructing a home, and therefore find property taxes hard to justify. There is much emphasis on community participation in deciding priority projects, but a huge gap exists between desired developments and those provided by local governments. Wa Municipal Assembly interviewees were quick to cite the street lighting and drainage systems they had provided, but local people wanted to see potable water, tarred roads, security and waste bins. At the end of the day, prime investments appear to be unappreciated.

Uncoordinated institutional arrangement and tax administration

According to Oldman (1992), there is considerable evidence that urban property tax revenues in developing countries have not kept pace with the growth of the tax base largely because of poor administrative systems. In Ghana, the national Land Valuation Division (LVD) for property rating was initially within the Ministry for Local Government, but has now moved to the Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources. As the LVD remains the sole valuation unit for property rating, it sits within a management structure which is detached from the mainstream of local government activities. It also makes it difficult for the LVD to access budgetary allocations by a municipal assembly to carry out its valuation functions. According to WA’s municipal valuation surveyor, every year annual estimates for valuation expenditures are submitted, but these budgets are never met. As the unit is also constrained by IGF shortfalls and other logistics, it is unable to deliver on its responsibilities. There is an urgent need to improve the structure of institutions tasked with bringing in local property tax revenue.

Property rate collection approach

The collection of property rates is the sole responsibility of the municipal assembly. Wa Municipal Assembly first approves the valuation list, then ascertains the rate payable per property. It then commissions rate collectors (cf Section 111 (2) of Act 462) to collect these rates by serving demand notices on property owners specifying how much they have to pay, together with the place, date and time for payment.

In Wa Municipality, property rate collectors are temporary workers, mostly high-school students or graduates engaged to distribute rate demand notices on behalf of the municipality. According to the municipal rating officer (field interview, 2010), the use of temporary workers is due to long-term staff constraints. The practice has both advantages and disadvantages. On the one hand, wage costs are kept down as the rate collectors are merely paid a commission, while the few permanent staff supervise and train them. On the other hand, these rate collectors lack basic map-reading skills and find it hard to locate rateable properties in the field. Past experience has also shown that some rate collectors have pocketed property rate monies in some municipalities where direct collection is allowed, and others have been accused of issuing fake receipts and collecting bribes from property owners in exchange for not serving demand notices on them. However, all eight rate collectors interviewed for this study refuted these claims in Wa Municipality (interviews with rate collectors, 2010).

Interviews with property owners identified a further problem. Some owners declared their willingness to pay, but said the mode of collection discouraged them. It is a statutory requirement to allow taxpayers three months’ grace before payment is due. Over these three months, 26% of property owners forget to honour their tax obligations.

It seems clear that the distribution of demand notices is not an effective method of bringing in property tax revenue.

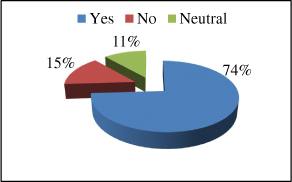

Public perceptions of property rating

In the present survey, a large number of respondents – 74% of the 96 property owners interviewed – claimed they paid their property rates (Figure 5). Payments were typically made upon receiving demand notices from rate collectors. Of the remaining respondents, 15% have never paid property rates and 11% did not respond to the question. Reasons given for non-payment of property rates included not being approached or not receiving a demand notice. Some respondents did not see the need to pay. After the concept was explained to them, they felt rating should be on properties rented out, not owner-occupied properties, since they did not receive income from their houses. In the Kpaguri area, the issue came up of properties belonging to families jointly, with no single identifiable owner. This also applied to most indigenous communities in Wa Township. The municipal rating officer (interview, 2010) revealed that rate demand notices distributed to indigenous people in Wa were vehemently opposed, and that some property owners also considered themselves too poor to pay. He also stated that most properties were not of a high enough quality to attract the rates charged. According to the municipal rating officer, some indigenes threatened to reoccupy all public lands acquired by the WMA, especially those with unpaid compensations.

Figure 5: Payment of Property Rate in Wa Municipality

Source Field Survey 2010

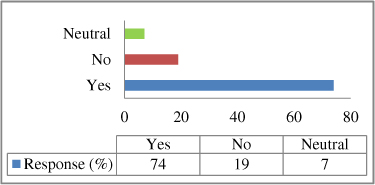

Knowledge about penalties for non-payment of property rates

Respondents were asked whether they were aware of the penalties for non-payment of property rates in Ghana, as stated in Section 108 of the Local Government Act 1993 (Act 462).5 Seventy-four per cent of respondents said yes, 19% said no, and 7% did not respond to the question posed (see Figure 6). Of private property owners, the majority did know there are penalties, and officials from Wa Municipal Assembly confirmed that property owners are regularly reminded of these penalties.

However, these reminders have not improved payment rates, suggesting it may be better to focus on educating people about why they should pay property rates, rather than issuing threats. It became clear from the survey that default is not pursued, beyond public radio announcements threatening to name and shame non-payers. As these efforts have not yielded the desired results, a stronger approach seems indicated, but it is not clear whether it should include actual prosecution and imprisonment for persistent default. This question may perhaps be answered by subsequent studies.

The awareness of respondents about property rating penalties is illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6: Knowledge of Penalties for non-Payment of Rates

Source: Field Survey, 2010

Conclusion and recommendations

Many challenges are hindering property rating from fulfilling its potential to serve as a major source of revenue for MMDAs in Ghana. The experience of Wa Municipal Assembly, however, shows that property rating can generate up to 30% of IGF – but to date the challenges identified in this study have prevented the contribution from being even higher. Although these challenges may be peculiar to Wa Municipality, they would seem to be no different from other municipalities in the Country (Boamah 2013 and Petio 2013). The difficulties include: non-enforcement of the law for defaulters, problems with funding revaluation surveys, insufficient staffing and low technical capacity of the few staff available. To improve the existing situation and influence policy directions, this study recommends a range of measures: the identification and mapping of all rateable properties; the classification and valuation of each property in accordance with agreed procedures by technically qualified and honest staff; the impartial identification of taxpayers; the preparation of a reliable and comprehensive valuation list; advance notification to property owners of their tax payable; the convenient collection of the appropriate taxes; fair appeal procedures in the case of disputes; and the regular publication of local government accounts and audit statements. District valuation divisions also need to work closely with the surveying and deed registration divisions of the Lands Commission to create improved methods of payment. It is only with these systems that property rating will generate the bulk of public finance needed at the local level to enhance decentralisation and advance local development.

The following recommendations are proposed.

Eliminate political interference in property rating

Property rating is politically sensitive because it concerns not just property owners, but also political elites, sympathisers and voters. Increasing taxation can be unpopular with politicians since the taxpaying electorate tends to threaten to vote them out. This means politicians have traditionally been very reluctant to review taxes. In Ghana’s case, the situation is even worse metropolitan, municipal and district chief executives (MMDCEs) are nominated by the government. Some MMDCEs have interfered with local taxation, protecting loyal supporters from having to pay taxes in return for political favours. It is recommended that property taxation be completely protected from political interference, by making ratings units made semi-autonomous with an independent budget to carry out its functions. It should also be acknowledged that, though all local taxes are politically determined, they require widespread public acceptance to be collectible.

Adopt information communication technology (ICT) in property rating

Computer-based rate administration would help the property rating sector greatly, although a high-quality paper-based back-up system is still recommended in case of power outages. ICT would enable easy capture, storage, updating and interrogation of data, and could also check for corruption and misappropriate of rating revenue. It would also facilitate quick and cost-effective revaluations and valuation list updates, by harnessing computerised appraisal and satellite-aided mapping software (Bird and Slack 2003). Despite high initial installation costs, the benefits are enormous and, by using computer-assisted mass appraisal techniques (FAO 2002), much of the work can be carried out by people with only basic IT and statistical skills. This would reduce workload yet increase efficiency, accountability and transparency. And, since a valuation list is a very large database, the fact that ICT will also allow for its data to be reproduced in several different formats is another benefit.

However, as emphasised by the FAO (2002: 35), ICT of itself does not ensure data quality or substitute for valuation and organisational skills. Local budgetary allocations are also needed for computers, networks, storage devices and staff training.

Send payment points closer to the tax payer

Property owners who stated they had paid property rates at one point or another complained that payment to rate collectors was risky, but payment at the municipal revenue office was inconvenient. They requested payment points closer to them, and this study consequently recommends decentralised rate collection, which will help minimise default and improve revenues realised. Frequent radio announcements or mobile-van reminders, and neighbourhood volunteer teams, could publicise this service. Property owners are more confident making payments to persons they trust and can easily relate with. Initiatives to encourage self-reporting, such as ensuring that revenue collected is earmarked for specific public services and amenities in the neighbourhoods in which the property tax was collected, would also be beneficial.

Mass public education

Apparently, no one wants to pay tax voluntarily. Ratepayers complain they do not see what their monies are been used for, and this acts as a disincentive. It is recommended that local governments demonstrate how taxes are transformed into development projects, by educating the public on projects underway and involving them in making local inputs and contributions (?). As pointed out by FAO (2002), nowadays citizens expect to be able to understand the issues that directly affect them, so it is important to keep the public well informed about processes and practices throughout the course of a development. This drive to demystify public offices and make them accessible for all can be driven by the Wa Municipal Assembly, the National Commission on Civic Education and the Information Services Department.

Reduce the tax burden on the poor

According to FAO (2002: 30), ‘an analysis of most valuation lists prepared on an ad valorem basis typically reveals that 40% or more of the total assessed value derives from less than 10% of the most valuable properties. On the other hand about half the population live in less valuable properties that account for less than 10% of the total value.’ This phenomenon is even more extreme in Wa Municipality, where 80% of people are poor, according to the Ghana Statistical Service. Property taxes should therefore be adjusted according to the ability to pay, with exemptions for the extremely poor. This would also save the assembly transaction costs for taxes which ultimately it will be unable to collect anyway.

Increasing the number of valuers and the capacity of field technicians

The shortage of certified estate valuation surveyors (EVS) remains a challenge in transitional economies and the public sector struggles to secure and retain these scarce skills. In Ghana, there is high demand for estate valuation services by private entities with better conditions of service. Strategies for combating this difficulty should include MMDAs sponsoring young graduates for further training in rating valuation, as well as in-house training of technicians on emerging methods of valuation to expand their horizons and build their competencies. Under the provisions of Section 111 (2) of Act 462, MMDAs could also hire private sector operators to assess property values, levy rates and collect taxes for them.

References

Adem, M. N. and Kwateng, A. O. (2007). Review of Real Property Tax Administration in Ghana. Master Thesis submitted to the Department of Real Estate and Construction Management Division of Building and Real Estate Economics Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden. Available at: http://www.pdfmeta.com/preview.php?url Last accessed 12/05/2010.

Adamolekun, L. (1999). Governance context and reorientation of government. Public Administration in Africa. Adamolekun, L. Boulder CO, Westview: 3-16.

Adedokun, A.A. (2006). Local Government Tax Mobilization and Utilization in Nigeria: Problems and Prospects. Department of Public Administration & Local Government. Studies The Polytechnic, Ibadan. Nigeria. Available at http://visar.csustan.edu/aaba/Adedokun.pdf. Last accessed 20/08/2010.

Asare, B. (1986). Planning and management of Local Government in Ghana. Research report, Land Administration Research Centre (LARC), KNUST, Kumasi.

Asiama, S. O. (2006). Land as a source of revenue mobilization for local authorities in Ghana. Journal of Science and Technology, 26, 116-122, KNUST, Kumasi.

Bahl, R. (1999). Fiscal Decentralization as Development Policy. Public Budgeting & Finance, Volume 19, Issue 2, pages 59–75, June 1999. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.0275-1100.1999.01163.x

Bahl, R. and Martinez-Vazquez, J. (2006). The Property Tax in Developing Countries: Current Practice and Prospects. International Studies Working Paper 06-37, December 2006.

Bahl, R. (2009). Property Tax Reform in Developing and Transition Countries, Fiscal Reform and Economic Governance Project, United States Agency for International Development.

Banful, A.B. (2007). Can Institutions Reduce Clientelism? A study of the District Assemblies Common Fund in Ghana. Harvard University.

Bird, R.M. and Slack, E. (2003). International Handbook of Land and Property Taxation Oxford University Press.

Boamah, N.A (2013). Constraints on Property Rating in the Offinso South Municipality of Ghana. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, Issue 13/14 November, 2013. www. http://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/ojs/index.php/cjlg. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.v0i13/14.3725

Braid, R. M. (2005) Tax Competition, Tax Exporting and Higher-Government Choice of Tax Instruments for Local Governments, Journal of Public Economics, 89, pp. 1789-1821. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2004.04.004

Chitembo, A. (2009). Fiscal Decentralisation: A Comparative Perspective. www.Iga-zambia.org.zm (Accessed: 11/01/2011)

Davey, K. (2003). Fiscal Decentralisation. www.unpan1.un.org

Di John, J. (2009). Taxation, Governance and Resource Mobilisation in Sub-Saharan Africa, Presentation for African Economic Outlook 2010, Expert Meeting Resource Mobilisation and Aid in Africa, 14 December, 2009.

Emeny, R. and Wilks, H. (1984). Principle and Practice of Rating Valuation. London, The Estate Gazette Ltd.

FAO (2002). Rural Property tax systems in Central and Eastern Europe, Land Tenure Studies No.5, Rome.

Franzsen, R.C.D. (2003). Property taxation within the Southern African Development Community (SADC): Current status and future prospects of land value taxation in Botswana, Lesotho, Namibia, South Africa, and Swaziland. Working Paper, Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. CMI Working Papers. No 25141.

Government of Ghana, The Local Government Act, 1993 (Act 462)

Government of Ghana, The Immovable Property Rate Regulations, 1975 (L.I 1049)

Jibao, S.S. (2009). Property Taxation in Anglophone West Africa: Regional Overview, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy Working Paper.

Kelly, R. (2000). Designing a Property Tax Reform Strategy for Sub-Saharan Africa: An Analytical Framework Applied to Kenya, Public Budgeting and Finance; Winter, 2000. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/0275-1100.00028

Kitchen, H. (2003). Property Taxation: Issues in Implementation. CEPRA II Project, AUCC Available at www.aucc.ca/_pdf/english/programs/cepra/PropertyTaxation Last accessed on 05/05/2010.

Mathur, O.P., Thakur, D., Bahl, R. and Rajadhyaksha, N. (2009). Urban Property Tax Potential in India. National Institute Of Public Finance And Policy, New Delhi.

McCluskey, W. J. and Bevc, I. (2007). Fiscal decentralization in the Republic of Slovenia: an opportunity for the property tax, Property Management, 25(4), 2007 pp. 400-419.

McCluskey, W., Franzsen, R., Johnstone, T., and Johnstone, D. (2003). Property Tax Reform: the Experience of Tanzania, Our Common Estate, July 2003.

Meinzen-Dick, R. S., and Knox, A. (2001). Collective action, property rights, and devolution of natural resource management: A conceptual framework. In Collective action, property rights and devolution of natural resource management: Exchange of knowledge and implications for policy, R. S. Meinzen-Dick, A. Knox, and M. Di Gregorio, eds. Feldafing, Germany: DSE/ZEL.

Mikesell, J. L. (2003). Fiscal Administration: Analysis and Applications for the Public Sector. Belmont, California: Thomson Learning, Inc.

Obeng-Odoom, F. (2010). Is Decentralisation in Ghana pro-poor? Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, Is. 6: July 2010. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.v0i6.1620

Okrah, M. and Boamah, N. A. (2013) Deepening Representative Democracy through Fiscal Decentralisation: Is Ghana Ready for Composite Budgeting?, AFRREV IJAH, Vol.2 (2), pp. 73-90.

Oldman, O (1992). Property Taxation in Latin America. In: M Ofori (ed.) (1992) Real Property and Land tax Base for Development. Taoyuan, Land Reform Training Institute Publication.

Olowu, D. and Wunsch, J. S. (2003). Local Governance in Africa: The Challenges of Democratic Decentralization (Boulder: Lynne Rienner).

Petio, M.K. (2013). Role of the Land Valuation Division in Property Rating by the District Assemblies in Ghana’s Upper East Region. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance. Issue 12, May 2013. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.v12i0.3265

Varanyuwatana, S. (1999). Property Tax in Thailand: In William McCluskey (ed), Property Tax: An International Comparative Review, Aldershot: Ashgate pp. 148-163.

Whittal, J. and Barry, M. (2004). Fiscal Cadastral Reform and the Implementation of CAMA in Cape Town, Paper presented at Session 5, Expert Group Meeting on Secure Land Tenure: ‘new legal frameworks and tools’ Nairobi, Kenya, November 10-12, 2004.

Youngman, J.M and Malme, J. H (1994). An international Survey of Taxes on Land and Buildings. Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, Deventer: Kluwer Law and Taxation Publishers.

FOOTNOTES

1 Mathur et al (2009: 5) in their study of India, describe property tax as a key ingredient of fiscal empowerment for municipal governments

2 Annual rental value is defined as the rent at which the premises can reasonably be expected to be let in the open market in an average year, taking into account all essential outgoings such as repairs, insurance and other expenses necessary to maintain the premises in order to command such a rent.

3 Replacement cost is the reasonable cost which would be incurred in building similar premises at the date of the preparation of the valuation.

4 Refer to section 86 (3) of the Local Government Act 1993, Act 462

5 Refer to Section 108 for penalties for refusal to pay rates and wilful misrepresentation, Section 109 penalty for inciting a person not to pay rates, Section 110 penalty for unauthorized collection of rates and Section 112 penalty in respect of offences by rate collectors. See also Section 118.