RESEARCH and EVALUATION

Challenges to implementing of development plans at local-level government in Papua New Guinea

Benjamin Saimbel Barcson

Graduate School of International Development

Nagoya University

Japan

Abstract

The 1995 local-level government reforms undertaken in Papua New Guinea (PNG) were largely in response to increasing concern that the public service was failing in its responsibility towards the people. As a result, the 1995 Organic Law on Provincial and Local Governments (OLPLLG) was established. The prime purpose of this was to address this issue through deeper engagement of the lower levels of government, particularly local-level governments (LLGs). Almost two decades on, poor socio-economic conditions and deterioration in infrastructure/services suggest that the proposed change has not materialised. The purpose of this paper is to address the question of whether the lower tiers of government are capable of implementing the development plans under the reforms. The paper finds that the 1995 reforms have made LLGs dependent upon their Joint District Planning and Budget Priorities Committee (JDP & BPC) and their district administration, which have become the main impediment to local government effectiveness. This in turn has greatly hindered LLG capacity and has reinforced unequal relations, rather than assisting service delivery in PNG. There is therefore a need to make LLGs more effective players.

Key words: local-level government, development planning, Joint District Planning and Budget Priorities Committee, district administration

Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance

Issue 16/17: June 2015

http://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/ojs/index.php/cjlg

Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance 2015. © 2015 Benjamin Saimbel Barcson. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Citation: Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance 2015, 0, 4492, http://dx.doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.v0i0.4492

Introduction

States all over the world have attempted to usher in socio-economic change via planned efforts, which are basically organised attempts to identify the most effective strategies to achieve targeted goals (Turner and Hulme 1997: 134). This activity implies the creation and formulation of policies to achieve effective development outcomes for citizens. These efforts have come to be known as development strategies/plans. Plans however are mere words on paper. Effective implementation to achieve the desired results requires reliable implementing agencies. In most cases, it is the state’s public service/bureaucracy which is designated as implementing agent. The effectiveness of this agent’s work will determine the final output of the plan.

Papua New Guinea (PNG) as a nation has established a variety of development plans since independence. The current socio-economic indicators however reveal very poor performance. For instance, it has been indicated by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) that PNG shows very little progress in achieving most of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) by 2015 (UNDP 2011: 6). Furthermore the Asian Development Bank (ADB) has found that social indicators in PNG are far below those of similar income-per-capita countries (ADB 2010: 5). Access to vital services such as health, education and transport infrastructure has deteriorated quite rapidly in recent years (Cammack 2008: 6). Indeed, in 2009 participants at a conference in Sydney on the theme ‘tackling extreme poverty’ noted that conditions had in recent years seen a drastic decline in PNG (Hayward-Jones and Copus-Campbell 2009: 1). This is all taking place at a period when the country is experiencing a resource boom. The state however, has failed to effectively translate these gains into sound development outcomes (AUSAID 2008: 23). The inability to effectively implement development agendas has had a disproportionate impact in rural areas of PNG (UNESCO 2007: 9). This negative consequence is grave, as 85% of the country’s population live in rural areas.

It is against this backdrop that this paper raises the following question: How effective is the state in implementing national development strategy and plans at the LLG level? Indications of decline in rural service delivery, deteriorating infrastructure and low income earning opportunities call into question whether LLGs are effective implementers. This article therefore focuses on the LLG arena.

This paper is drawn from the author’s PhD research looking into the reasons for the failure of LLG decentralisation to achieve effective rural development outcomes in PNG. In the process, the problems behind the establishment and implementation of development plans were identified. The research was undertaken in Dreikikir, East Sepik Province. Dreikikir LLG was selected as the study site as it was one of the most remote, rural and underdeveloped areas in the country. It thus provided a good test of whether development plans were being developed and implemented effectively in rural areas. It is hoped that the study of Dreikikir will offer insight into the plight of many rural districts in PNG.

The study used two main sources: primary interviews and secondary information (namely published literature). Interviews were conducted with seven district officials in Ambunti-Dreikikier District Administration and ten ward members. All interviews were carried out on a one-to-one basis at various locations in Ambunti-Dreikikir District and Dreikikir LLG area, between September 2012 and October 2013. The seven Ambunti-Dreikikir District officials interviewed were selected according to the different administrative functions they performed in the district and LLG. The wards from which they were selected were chosen based on two primary factors: distance from the local government outpost and population size. Thus Ward 7 had only 300 citizens whilst Ward 1 had 1,200 citizens. Ward 7 also was located over three hours (by foot) from the government outpost of Dreikikir, whilst Ward 2 was only 30 minutes. However, the distance to access main services such as roads, health centres and services provided by the local government station of Dreikikir were the main factors in selecting the wards. Among its questions, interviews with ward members looked at whether the wards in Dreikikir LLG had local development plans targeting these access issues.

Secondary sources such as published literature were primarily used to complement the findings of the interviews. This included the Ambunti-Dreikikir District Plan, which offered vital information about the district. Other works were used to relate this experience to other areas of the country. The findings were then analysed and are presented in this paper.

Importance of local-level governments

The role of local-level governments as a public service delivery mechanism and agent of state functions is of critical important within a decentralised state. The theory is that through devolution1 of powers, functions and responsibilities, lower levels of government will become more efficient and responsive to local needs (Arun and Ribot 2002; Omar, Kähkönen and Meagher 2001). This approach is seen as strengthening accountability and increasing participation of local citizens in the decision-making process, as well as resulting in implementation of strategies best suited for their localities (Scott 2009; Ahmad et al 2005; Brenton 1999; Smoke 2003). The aspiration is that local-level governments will deliver more effectively in areas where the national government may lack insight, and that they will become an essential mechanism for the roll-out of state services and programmes.

According to Kimura (2011: 19-20), five features determine the effectiveness of a local government. These are:

- the relation between central government and local governments

- the relationships between the various levels of government

- the capacity development of local governments

- local systems for building local economic development

- participation mechanisms for citizens

Kimura’s features will be used in this paper’s analysis; the capacity development of local governments, local systems for building local economic development, and the relationships between central governments and local governments. A proper understanding of how local governments function in relation to these features is essential to appreciate the constraints they experience. However, Kimura (2011: 17) notes two further problematic issues affecting efforts to decentralise to lower tiers of government. These are reluctance by central governments to delegate powers to lower levels, and the capture of benefits by local elites when power is shared. In the PNG context these are very evident. As this paper will show, the 1995 reforms have reinforced the role of national politicians and ultimately have led to heavy politicisation in the districts.

PNG’s 1995 reforms were a response to general frustration at the state’s inability to deliver much-needed services to the people (Kalinoe 2009: 2). The reforms therefore aimed to deliver services effectively to the rural population, increase citizen participation and devolve more functions and responsibilities, together with more funding, to lower levels of government (Kalinoe 2009: 4).

Development planning in Papua New Guinea

As at the date of this paper, PNG has undertaken ten different development plans. The first from the Australian colonial administration in 1963 (Yala and Sanida 2010: 45). Since then there have been nine others, including the current one launched in 2011.

For the co-ordination of various development plans, the Department of National Planning and Monitoring (DNPM) was established in 1992 (Dobie and Nirody 1996: 2). The DNPM has since assumed responsibility for overall strategy and guidance on all development initiatives. Political links to the plans however remain weak, because political parties do not create plans to be implemented. Unlike other countries, where party policies and platforms influence the direction of planning, PNG lacks this political party linkage. Although there are political parties, all signs of ideology are absent from them. They operate on fluid ideologies and policies and realign whenever the situation requires. As a result, the planning process in PNG is largely co-ordinated by technocrats with no particular affiliation to any political party (Yala and Sanida 2010: 45).

Preparation of plans

Provincial governments, districts (electorates), LLGs, and wards are mandated by law to produce development plans based on national priorities and targets customised to their localities (Kalinoe 2009: 31). Hence provincial plans are created by the provincial planning office, to establish the province’s goals in line with the national development plan targets and priority areas for the province. Meanwhile each LLG is required to use all their wards’ plans to create their LLG plan. The district then incorporates all its LLG plans into the district plan. The district’s key role is to integrate the ‘top-down’ planning of the province and nation with the ‘bottom-up’ planning of the LLGs (Barcham 2009: 15). The aim is to merge bottom-up planning with a top-down strategy approach, thus creating a realistic plan which addresses development challenges effectively at each level. It is the responsibility of the district administrator to ensure that the planning capacity of LLGs and wards in their district is adequate to discharge their mandated responsibilities from plan design to eventual implementation. The provincial hierarchy has ultimate responsibility for overseeing all the districts within its jurisdiction, which includes LLGs and wards.

Political and administrative background in the provinces

Under the 1995 reforms the previous provincial government system was abolished with the introduction of the OLPLLG. This system, trialled between 1995-1997, entailed profound changes in provincial government systems, operation and structure (Kalinoe 2009: 3).

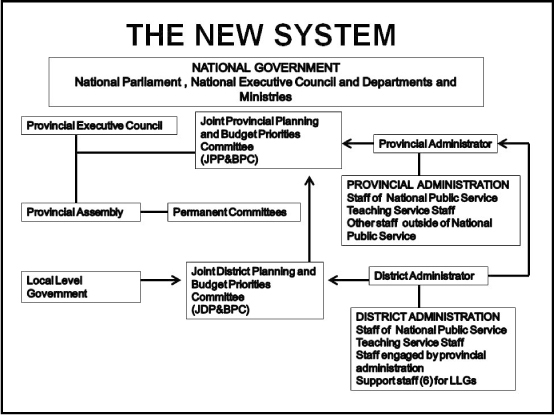

Figure 1: Provincial Political and Administrative Outline

Source: modified by author from Edmiston 2002: 5)

| Political structure | Administrative structure |

| a) Provincial executive council | a) Provincial administration |

| b) Provincial assembly | b) District administration |

| c) Local-level governments | |

| d) Wards |

A notable feature of the 1995 reforms was the establishment of a Joint Provincial Planning and Budget Priorities Committee (JPP & BPC) and a Joint District Planning and Budget Priorities Committee (JDP & BPC) at the provincial and district levels respectively. The purpose of these two committees is to co-ordinate all planning and assess/approve funding priorities for development projects. The committees were intended to be forums for the political and administrative sectors to meet at their relevant levels.

Each provincial executive council is responsible for setting up a JPP & BPC. By contrast, however, the JDP & BPC is established by the 1995 Organic Law on Provincial and Local-Level Governments and hence requires no establishment by any committee. It comprises the local MP (who is the chairperson), the presidents/mayors2 of LLGs in the electoral area, representatives for women, business and religious sectors, and the district administrator.

The administrative head of the province is the provincial administrator,3 who is also the chief executive officer of the provincial government, with district administrators under him. The provincial administrator’s role is to supervise all public service functions and administrative services within the province. At the district level, the district administrator performs this role in co-ordination with their district administration. Their main duties involve discharging their public service functions and implementing plans and policies established by the provincial and district administrations.

Within each province there are smaller electorates. Each electorate has an administrative centre, often referred to as the district, and within the district there are between four to six LLGs. The LLGs in turn are made up of wards – 30-40 wards per LLG. Wards are usually a grouping of one or more villages, depending upon population. Wards elect a ward member to their local LLG every five years. The LLG president/mayor however is directly elected by all citizens in the LLG.

District administration structure

District administrations are not politically elected bodies; rather they are administrative units made up of local public service sectoral heads and other officials. The main function of these officials is to co-ordinate and ensures the delivery of public services to their designated local areas. However, all public service officials are paid by the national government, not the provincial, district or local-level government. Nor do sectoral heads participate in the JDP & BPC.

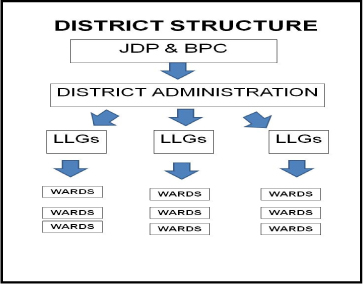

Figure 2: District Structure (Source: Author)

Under the structure introduced in 1995, greater responsibility over health, education, agriculture, upkeep of infrastructure and local programmes was transferred to district level. The provincial administrations’ role was reduced to mainly technical advice and support. However, each department within the districts still receives departmental funds, depending on the departmental programmes undertaken. All matters in relation to the district also still go through the district management team meeting – which brings together all district divisional heads and the district administrator – and which later conveys its issues/concerns to the JDP & BPC. As a result the JDP & BPC has become the main co-ordinating centre from which the district organises public service delivery in its area (including LLGs and wards).

Under the 1995 structure, LLGs came to find themselves with greater responsibility in a number of areas: health (rural health centres); education (elementary and primary schools4); local economic development (in co-operation with the district administration); the maintenance of feeder roads; and other issues affecting local people. The reforms envisaged that the LLGs would be an essential mechanism for delivering the anticipated improved outcomes.

Development planning, implementation and monitoring at the district level

The JDP & BPC, in partnership with the district administration, is responsible for overall co-ordination of planning, implementation and monitoring, as well as allocation of funding for priority areas within the district. It is responsible for the district’s five-year development plans, complete with financial estimates; and for the review of ongoing plans (Cammack 2008: 16; Axline 2008: 19). In theory implementation now occurs according to resolutions passed at JDP & BPC meetings, and it is now the responsibility of the district administrator to implement those resolutions. This involves, for example, processing cheques through the district/provincial treasury and supervising planned projects.

Revenue sources and funding for provincial and local-level governments

Under the 1995 reforms, the OLPLLG identifies various funding streams to be made available to each level of government to implement initiatives (Independent State of Papua New Guinea 1998). The following are the types of funding available by law to both provincial and local-level governments (wards are included within LLGs):

- Provincial/district Service Improvement Programme grants

- Provincial/district support grants

- Administrative support grants (province and LLG)

- Development grants (province, LLG and ward)

- Taxable revenue where applicable (province and LLG)

- LLG Service Improvement Program (LLGSIP)5.

It has now been over 15 years since the implementation of the 1995 reforms. However the anticipated outcomes have not eventuated. Instead, conditions are actually deteriorating. This suggests that the development plans are not being implemented effectively.

The remainder of this paper looks at the challenges local-level governments face in implementing development plans, using Dreikikir LLG as a case study. The study was based on interviews conducted with ten ward members (known as ward councillors) in Drekikier LLG – one each from Wards 1 to 10 – together with seven officials from the Dreikikir district administration. It is acknowledged that a case study cannot be taken as representative of all areas in PNG; but findings from available literature, which have been used to complement the present research, indicate that many of the issues faced by Dreikikir are common to other LLGs.

The case of Dreikikir local-level government

Dreikikir LLG is one of the four LLGs located in the Ambunti-Drekikier Open Electorate (ie ‘constituency’) in PNG’s East Sepik Province (National Research Institute) 2010: 114). Administratively, the electorate has two district centres: Ambunti, where certain offices such as the district treasury are located; and Dreikikir, where other offices such as the Department of Agriculture, Livestock and Wildlife (DALW) are located. This anomaly is a consequence of the realignment of boundaries associated with the 1995 reforms (Kalinoe 2009). Under the 1995 reforms the JDP & BPC for Ambunti-Dreikikir District is the main co-ordinating body, under which are the Ambunti-Dreikikir district administration, followed by the four LLGs – of which Drekikier LLG is one – and finally, at the most local level, the wards.

Geographically, Dreikikir LLG is located in the foothills of the Torricelli mountain range and benefits from fertile agricultural land. It covers an area of 1,200km2 and has a population of 19,000 spread over 33 wards. Its population density is 3.6/km2 (Ambunti-Dreikikir District Office 2008: 17). The population of the wards studied ranged from 300 (Ward 7) to 1,200 (Ward 1). The majority of the population own land via customary land tenure and are subsistence farmers who produce staple food crops of taro, banana and yams, mainly for their own consumption. Their main source of income is the production of cash crops such as coffee, cocoa, vanilla and betel nut (Hanson et al 2001: 213). Earnings, however, are very low and heavily dependent on international commodity prices. As a result the average income in the area is about 41-100 kina (US$15.1-US$36.8) a year per person (Hanson et al 2001: 209). There are also a few successful business people who operate small trading stores offering basic goods such as rice, tinned fish, salt, sugar etc. However, most local enterprises in the wards, such as cocoa bean drying facilities and transport services, are primarily clan-based projects, utilising family ties to raise any funds needed as well as provide physical manpower when required.

There is, however, a lack of credit facilities, co-operative structures and proper markets for local food crops. Extension activities and advice are unreliable and are not provided by DAWL officers. A good example is the problem of cocoa pod borer moth, which is currently ravaging the area. Most citizens have received no assistance from the officials tasked to help them address such difficulties. As a result, people do their best within their capacities.

Deficits in basic services

Drekikier LLG has a total of 30 educational facilities: 11 lower primary schools, 13 upper primary schools, four elementary schools (elementary preparatory to elementary 2), one high school, and one technical vocational centre (Ambunti-Dreikikir District Office 2008: 24). The responsibility for the upkeep and maintenance of elementary schools and lower primary schools falls to Dreikikir LLG. However, most of these schools operate in facilities made from bush materials; very few have a classroom or staff house made from durable materials. There is high student retention problem in the schools in the area (Ambunti-Dreikikir District Office 2008: 39). Staff shortages are also a problem, as teachers often do not want to take up posts in such a remote area. However, the main problem has been to effectively maintain the quality of education. Currently, the majority of students do not progress to upper secondary.

There is no access to electricity in the LLG and wards, apart from via portable generators. The district administration in Dreikikir does have a large generator, but it only provides a reliable service when funds are made available by the provincial administration for the purchase of fuel. Even then it only runs for 5-6 hours a day, at night-time.6 Although the generator may be adequate to deliver rural electrification to nearby wards, this has yet to happen.

Piped water is non-existent within the LLG. Wards in the area rely on water catchment tanks and traditional water wells. AUSAID (the Australian Agency for International Development) has recently initiated a water catchment project in certain wards to address supply problems but this project is reliant upon rainfall.

Dreikikir LLG has a total of 15 health facilities: one main health centre and 14 rural health centres (Ambunti-Dreikikir District Office 2008: 25). Responsibility for the 14 rural health centres/aid posts lies with the LLG. However, of these 14 centres nine have shut down – principally due to poor physical condition and the remaining health facilities are also run down. On the whole the Dreikikir LLG health sector suffers from: a lack of proper infrastructure or equipment; a lack of capacity to undertake rural extension work or maintain current facilities; and an absence of control strategies to address malaria and other infectious diseases.7 The average life expectancy in the area is 54, with an infant mortality rate of 84 per 1,000. Leading causes of death have been pneumonia (8 per 1,000), prenatal conditions (8 per 1,000), tuberculosis (5 per 1,000) and malaria (Ambunti-Dreikikir District Office 2008: 5). Most of these deaths take place in the wards, where the rural health centres are supposed to assist but are either unable do so or not operational.

Roads are also problematic. Like most LLGs in PNG, Dreikikir is a rural LLG. Access to the nearby township of Maprik and the provincial capital of Wewak is by road. The main mode of transport is by public motor vehicles operated by individuals in the area. The LLG is responsible for three main feeder roads with a total length of 49.5km. The current state of these feeder roads is that they have deteriorated into bush tracks. This makes it hard for wards both to transport cash crops and to bring in goods for small store owners. Some 45% of wards in the LLG are located near the roads, but the remaining 55% are less fortunate and are even more cut off (Ambunti-Dreikikir District Office 2008: 27). Accessibility to reliable health services and good schools is also affected by the road network, as most functioning health centres and schools are located along the main Sepik Highway. The further from the highway residents are, the more unreliable the services they receive (Hanson et al 2001: 211). This study noted, however, that many public service officials in remote areas of the LLG do their best to try to deliver despite these difficulties.

Dreikikir LLG’s problems can therefore be grouped into five areas. Firstly, it has a problem addressing rural healthcare effectively. Secondly, it faces the challenge of how to develop the local economy. Thirdly, it needs to improve the quality of education, as well as the services provided in its elementary schools and lower primary schools. Fourthly, it needs to improve rural electrification and water supply. And finally, the LLG has failed to maintain its feeder roads.

These wide-ranging problems call into question the ability of Dreikikir LLG to meet its targets. This paper will now consider the factors hindering effective implementation of development plans in Dreikikir LLG.

As identified above, Kimura (2011) notes five features essential to determining the capacity of local governments. The following three will be used to analyse Drekikier LLG’s challenges:

- the capacity development of local governments)

- systems for building local economic development

- the relationships between the various levels of government.

In Dreikikir LLG’s case, the specific challenges encountered can be described as:

- the capacity of Dreikikir LLG to address its mandated functions

- the ability of Dreikikir LLG to develop a system for local economic development

- the nature of power relations between Dreikikir LLG, its local district administration and local JDP & BPC.

Capacity of Dreikikir LLG to address its mandated functions

Dreikikir LLG is mandated to deliver district-level services which include health (rural centres), education (elementary schools/lower primary schools), infrastructure development/feeder road maintenance, and agriculture extension activities. Its capacity to deliver these depends upon three main elements: funding, human resources and the ability to make independent administrative decisions. If these three attributes are lacking or inadequate, capacity to deliver the required services will be severely impaired.

However, all these elements seem to be in deficit within Dreikikir LLG. Firstly, most essential funding is not directly delivered to Dreikikir LLG. Under the OLPLLG, Ambunti-Dreikikir JDP & BPC is responsible for determining the budget breakdown of Dreikikir LLG. Dreikikir LLG is required to submit funding proposals to the JDP & BPC and to district officials for its planned targets. However, as noted by the Dreikikir District finance administration officer8 funds can only be allocated to an LLG if they are requested following a resolution at an LLG meeting and submitted to his office for processing. Failure to do this will mean non-payment of funds. This puts Dreikikir LLG in a very difficult position, as the JDP & BPC is often manipulated by the local MP (see section ‘Politics and manipulation’ below). Furthermore, LLG funding from the provincial administration is unreliable. The acting LLG manager9 noted that often such funding arrives late, and is diverted or reduced by the district administration and JDP & BPC before reaching the LLG. Finally, the local revenue base10 for Dreikikir LLG from taxes, the LLGSIP and licences is not sufficient to undertake large projects.

Examples of these difficulties can be seen in several sectors in Dreikikir LLG. For instance, the maintenance and upkeep of rural health centres is the responsibility of Dreikikir LLG. However, the present study’s interview with the district health extension officer11 (HEO) revealed that the district had had to take over the health centres as the LLG was unable to maintain them adequately leading to deterioration of the infrastructure and closure of several centres. The HEO also noted that the LLG realised what was happening, but was handicapped by the administration and the JDP & BPC due to organisational issues. The education sector of Dreikikir LLG provides another example. Most major funding for schools is controlled by the district education advisor (DEA) and requires verification by him/her before disbursement to school accounts. This leaves room for manipulation of funds by the DEA. At Arkwemb Lower Primary School in Ward 7 (Misim Village), for instance, the local ward member12 attempted on numerous occasions to secure necessary funds for this school, located in his ward. The provincial education office referred him to his DEA, but despite prolonged discussion with the DEA the money was never received. A former DEA interviewed13 also noted that LLG funds for education matters were often diverted from the LLG by the district administration and the JDP & BPC. LLG feeder roads, electricity supply and water supply systems offer yet more examples of the fiscal deficiency of Dreikikir LLG.

A former president14 of the LLG stressed in interview that he had intended to address these issues, but was handicapped as he had no control over the funds. It seems clear that Dreikikir LLG’s financial capacity is weak, unreliable and controlled by district administration officials and the JDP & BPC.

The second aspect of Dreikikir LLG’s lack of capacity relates to human and technical resources. According to the structure outlined above, Dreikikir LLG must produce a development plan incorporating all the individual plans of its wards and aligning them with provincial and national priorities, but customised to meet the needs and priorities of the locality. However, Dreikikir LLG does not have an LLG development plan,15 nor do its wards have ward development plans. All ten of the ward members16 interviewed stated that they had no ward plans, ward books or ward development committees in place. They were aware that the district had a development plan, but they had not seen it or understood its main goals and targets, nor how it would be applicable to them. When asked if ward members and the general public were consulted during the planning process, the district finance administration officer17 claimed that wide consultation was undertaken. However, a common sentiment expressed by ward members was that the district administration never engaged them in consultation. Furthermore, they noted that district officials never offered any skills training to educate them in the process of plan formulation, data collection or goal identification. The acting LLG manager18 for Dreikikir LLG commented that, due to incompetent officers being hired as a result of cronyism, the relevant district officer could not effectively assist the LLG or ward members in such matters as he was not qualified for the job. Simultaneously, a former LLG president19 noted that the LLG had no development plan in place, nor had it undertaken extensive data collection exercises, or kept effective records. A former LLG manager20 commented that when he had worked for Dreikikir LLG, in 2009, most administrative activities were based on guesswork rather than data, as there was no proper data collection system or qualified personnel to collect the data. This author would argue however that blame does not lie only with the LLG, as the JDP & BPC and district administration officials have failed to develop LLG capacity.

A final consideration is the capacity of Dreikikir LLG for independent decision-making. As illustrated above, fiscal decisions are largely in the hands of the district administration and the JDP & BPC, leaving little scope for the LLG to influence the process. As far as administrative decisions are concerned there seems to be very little clarity about what the functions and responsibilities of LLGs are for instance, two or more wards may share a common facility, such as a rural health centre or elementary school. However, it is not clear from the OLPLLG how exactly they should work together to maintain the quality of these joint facilities. Five21 ward members, whose wards shared a rural health centre, also noted that the managers of the facility had no accountability towards them as local leaders – but only towards their departmental and district administration superiors. The health extension officer interviewed22 confirmed this: namely that accountability was mostly on departmental and district administration lines, leaving the local leaders on the sidelines. A similar situation prevails in the case of elementary schools in the area.

It therefore appears that the decision-making capacity of Dreikikir LLG over both financial and administrative issues in sectors such as health and education is weak. Once again power is concentrated in the hands of district administration officials, leaving little room for the LLG to take effective decisions on essential issues such as non-performing teachers/health workers, or funding matters.

Ability of the LLG to develop a system for local economic development

As Dreikikir is a rural area, the most viable form of local economic development is endogenous development – ie utilising local resources. The main local resources in Dreikikir LLG are cash crops and food produce. Labour, capital and land also need to be available, supported by good infrastructure (facilities and roads), support organisations (eg co-operatives) and access to good markets. However, while land and labour are abundant, there is a big problem in delivering infrastructure such as roads, which is difficult to remedy given the fiscal capacity of the LLG. Secondly, decision-making over agricultural issues is largely in the hands of district officials with little involvement of LLG officials. For instance, the ward members interviewed23 claimed it was difficult to gain access to staff at the district office. As a result, they were not aware of any specific projects that would involve them or how they could incorporate the DALW’s activities into their own plans. They also commented the staff was not in their offices most of the time, and there was little the LLG could do to address this problem.

Developing a successful local economy would require Dreikikir LLG to have effective agricultural outreach programmes, good co-operative agencies, good feeder roads and micro-credit facilities within its jurisdiction. However the LLG lacks both the fiscal capacity to develop these essential components and the decision-making capacity to develop suitable plans on its own.

Power relations between Dreikikir LLG, the district administration and the JDP & BPC

Dreikikir LLG and its ward members exemplify a situation in which the LLG is largely prevented from effectively carrying out its duties, and is highly dependent on the district administration and the JDP & BPC. In turn, the district administration and the JDP & BPC are heavily manipulated by the local MP, with JDP & BPC members and the general public unable to exert much influence. Under the OLPLLG, the local MP automatically chairs the JDP & BPC, and there should be effective co-ordination and guidance from the JDP & BPC to all levels under it. This has not happened. Instead, there has been an abuse of power by the MP. Six24 of the seven district officials interviewed said that the JDP & BPC was much politicised and was not effectively discharging its responsibilities. A former president of Dreikikir LLG, Mr Manarip, noted that the JDP & BPC was only good at making resolutions, not implementing them. According to Mr Manarip, there was no good management or effective direction from the JDP & BPC. This affected the district administration and created large gaps between the MP, the JDP & BPC, the district administration and the LLG over funding and implementation priorities. The district finance and administration officer noted that projects were never discussed, but rather were controlled and allocated along cronyism lines, often highly influenced by politics. Three25 of the officers interviewed strongly hinted that such politicisation had rendered the district administration largely ineffective and weak, and staff was simply puppets of the MP. As a result, working relations between these levels were not good.

Capacity constraints of LLGs

As seen above, Dreikikir LLG’s capacity as a local partner institution has been severely hindered by the district administration and the JDP & BPC. Reviewing these challenges, four main impediments to the LLG’s effectiveness can be identified: lack of planning, inequality of funding arrangements, politics and manipulation, and marginalisation.

Lack of planning

In order for outcomes to be achieved, effective planning practices are required. These however do not exist in Dreikikir LLG and its wards, largely due to a failure by the district administration and the JDP & BPC to develop local planning capacity. This problem is replicated throughout the country. A study undertaken by Zahid, Keefer and Menzies (2011: 4) indicated that 50% of LLG wards had no plan of any type. Another study, conducted by the Constitutional Law Reform Commission and covering six provinces, also found this to be a recurring issue (Kalinoe 2009: 13). Allen and Hasnin (2010: 14) further note that LLGs’ roles in PNG have largely been stifled due to ineffective planning, while Barter26 (2004) points out that state has failed at the lower levels of government to put in place effective planning components, such as staffing and essential funding, which would enable capacity to be developed. The main constraint in this area is a lack of human resources and proper co-ordination by those responsible for developing the required skills within LLGs and wards. As a result, planning processes are non-existent in the majority of LLGs and wards in PNG.

Inequality of funding arrangements

Drekikier LLG is financially reliant upon its district administration, its JDP & BPC and its provincial administration. Its revenue-raising capacity is limited to certain taxes, which are insufficient to fund, undertake and sustain large-scale projects. Also, as a result of inequitable fiscal regulations, Drekikier LLG has suffered diversion of funds and manipulation by those officers who do have fiscal control. This finding is replicated in most LLGs across the country. For instance, Allen and Hasnain (2010: 14) comment that provincial governments have been seen to starve most LLGs in the country of funds, rather than effectively assist them. There is also no proper funding structure to support facilities which are shared between wards; or, according to Ketan (2007), to allocate funds between districts and LLGs. LLG funding arrangements are thus profoundly problematic, and LLGs are dependent rather than self-reliant. As a result most LLGs become victims, as funding processes are hijacked by leading local officials (Hegarty 2009).

Politics and manipulation

The case study of Dreikikir LLG reveals significant politicisation and manipulation within essential structures such as the JDP & BPC and the district administration. These problems have led to a decline in the productivity of Dreikikir LLG, because when a JDP & BPC becomes dysfunctional it renders LLGs dysfunctional also. This has happened quite frequently in PNG. For instance, Allen and Hasnain (2010: 22) note the case of Southern Highlands, Mendi and Koroba Lake Kopiago, where the JDP & BPC never even met, but instead the MPs appropriated local funds for ‘pork barrel’ politics. In another example, a New Ireland provincial governor used political cronyism to bypass district and LLG officials via his ‘Limus Structure’ (Kalinoe 2009: 34). In this case, bypassing the normal system and instead allocating resources through local political strongmen nearly brought the province to its knees and had profound negative consequences for the provincial administration and local service delivery. In this environment, the role of LLG presidents has been significantly reduced, whereas the MP and district administrator now possess significant powers (Cammack 2008: 37). A further irony is that district administrators and MPs are not accountable to LLGs, and thus are easily able to manipulate them.

Marginalisation of LLGs

It seems clear that the main reason for Dreikikir LLG’s weak capacity to address local, provincial and national development agendas is that it is prevented from doing so by the JDP & BPC and the district administration. Those responsible for developing and co-ordinating Dreikikir LLG’s plan formulation and skills development - namely the JDP & BPC and the district administration – are not doing their jobs. A second reason is that fiscal control by those in authority has made the LLG financially reliant upon them. As a result the LLG cannot undertake the activities it wishes, where and how it wishes to do so. A third reason is the lack of horizontal accountability to Dreikikir LLG by public service officials. Local officials are thus unreliable, but Dreikikir LLG lacks the independent decision-making capacity to address issues on its own. As a result Dreikikir LLG is now a spectator to what it should be implementing.

As can be seen from the case study of Dreikikir LLG, and incidences from across PNG, LLGs face great difficulties in trying to deliver effectively to their wards and ultimately their local people. Priorities are unlikely to be aligned if there are no plans and no co-ordination by local officials with the LLG and local ward leaders. Failure by the district administration to develop skills and awareness of the roles of ward members has left members sidelined. In the final analysis, blame must fall onto the district administrator, as the district’s chief executive officer, and the district’s JDP & BPC and provincial administration. All have failed in their duties as mandated by the 1995 OLPLLG.

The 1995 reforms sought to make local-level government more effective. However, it failed to make it fiscally independent; instead it made it dependent upon upper levels of government. Whilst the district does practise vertical accountability, there is no horizontal accountability towards LLGs. Hence when constrained by limited resources, unreliable funding, unqualified personnel and political manipulation (which is reinforced by the new structure) LLGs become helpless. This makes it very difficult for them to implement national development agendas via a top-down and bottom-up approach whilst at the same time addressing their local issues. The bottom line is that LLGs in PNG are simply rubber stamps, given the huge marginalisation they face.

Conclusion

LLGs in PNG seem to be in quite a predicament, if the case of Dreikikir LLG is typical. Whilst the 1995 reforms envisaged change and success, this has not been forthcoming. The system has facilitated widespread abuse by the MP, the district administration and the JDP & BPC, preventing LLGs from effectively implementing national and local development agendas. There is therefore a great need to free LLGs from this straitjacket and make them independent, fiscally self-reliant, amply resourced and staffed with qualified personnel on the ground. If national and local development agendas are to be addressed effectively, the existing scenario must change – otherwise the current constraints will continue to impede effective development at the LLG level.

The 1995 OLPLLG should be revisited and provisions made to remedy these difficulties. Strengthening LLGs’ legal position will certainly make them more effective, but this strengthening needs to include funding structures, power relations with the JDP & BPC and the district administration, and measures to ensure these personnel are accountable to LLGs. It is only through such an approach that local and national plans can be developed and targeted more effectively.

However it must also be noted that LLGs too must be made accountable. Vertical accountability is not sufficient; there must also be horizontal accountability to local people, enabling them to see for themselves that their LLG has become more effective. Finally, if development strategies are to be implemented effectively, then LLGs must cease to be ‘rubber stamps’ and instead become actual implementers of national and local development agendas.

References

Ahmad, J, Shantayanan D, Stuti K and S Shah, 2005, Decentralisation and service Delivery, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 3603, May 2005, World Bank, New York

Allen, M. and Hasnain, Z. (2010) Power, pork and patronage: Decentralisation and the Politicisation of the development budget in Papua New Guinea, Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance (6) 7 - 31

Ambunti Dreikikir District Office, (2008) Ambunti-Dreikikir District Ten Year Development Plan, Ambunti-Dreikikir District Office, Dreikikir

Arun .A and Ribot, J.C. (2002) Analysing Decentralisation : A Frame Work with South Asian and East African Environmental Cases, Environmental Governance in Africa: Working Paper Series, World Resource Institute, Washington DC

Asian Development Bank, (2010) Development Effectiveness Brief Papua New Guinea Building Solid Physical and Social Infrastructure, Asian Development Bank, Philippines

Australian Agency for International Development. (2008) Annual Program Performance Report for Papua New Guinea 2009, Australian Agency for International Development, Canberra

Axline, A .W. (2008) The Review of Intergovernmental Financing Arrangements and The Restructure Of Decentralised Government In Papua New Guinea, Paper Prepared for Presentation at the Workshop: Reforming Decentralisation and Sub-National Fiscal Policy in Papua New Guinea 28-30 April 2008, Workshop Location: Port Moresby

Barcham, M. (2009) Knowledge Notes: Building the Capacity of Local Level Government in Papua New Guinea: Strengthening the Machinery of Government, Synexe, New Zealand downloaded from internet at; www.synexe.com, on the 13, 2012 at 6:11pm

Barter, P. (2004) Blunt assessment, hope and direction: lower level government in Papua New Guinea, in: Sullivan .N (ed) Governance Challenges for Papua New Guinea and the Pacific Islands, Divine Word University Press, Madang

Brenton, A. (1999) An Introduction to Decentralisation Failure, International Center for Economic Research, Turin

Cammack, D. (2008) Chronic Poverty in Papua New Guinea, Background paper for the Chronic poverty report 2008-09, Chronic Poverty Research Center, United Kingdom

Dobie, P. and Nirody, A. (1996) A Capacity 21 Initiative for Papua New Guinea, Report on a Mission to Initiate A Capacity 21 Process In Papua New Guinea, UNDP, Port Moresby

Edmiston.K.D,2002, Fostering Subnational Autonomy and Accountability In Decentralized Developing Countries: Lessons From The Papua New Guinea Experience, Public Administration And Development. Vol:22, pp:221–23

Hegarty. David, 2009, “Governance at the local level in Melanesia - Absent the state,”Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, Issue 3,pp:1 -19

Hanson. L.W. et al. (2001) Papua New Guinea Rural Development Handbook, Land Development Group, Canberra

Hayward-Jones, J and Copus-Campbell, S. (2009) Tackling Extreme Poverty in Papua New Guinea Outcome Report, Lowy Institute for International Policy, Australia

Independent State of Papua New Guinea (1998) The Organic Law On Provincial Governments and Local-Level Governments, http://Www.Igr.Gov.Pg/Olaw.Pdf, accessed on 06/10/12 at 08:29 am

Ketan, J. (2007) The Use and Abuse of Electoral Development Funds and their Impact on Electoral Politics and Governance in Papua New Guinea, CDI Policy Papers on Political Governance 2007/2. Canberra: Centre for Democratic Institutions, The Australian National University.

Kimura, H. (2011) Ideal and Reality of Local Governance, in Kimura, et al (eds), Limits of Good Governance in Developing Countries, Gadjah Mada University Press, Jogjakarta

Kalinoe, L. (ed) (2009) Constitutional and Law Reform Commission of Papua New Guinea Monograph 1-Review Of The Implementation of The OLPG & LLG On Service Delivery Arrangements: A Six Provinces Survey, Constitutional and Law Reform Commission, Port Moresby

May, R.J. (2005) SSGM Project Report on Workshop: District Level Government in Papua New Guinea, Australian National University, Australia

National Research Institute. (2010) Papua New Guinea District and Provincial Profiles, National Research Institute, Port Moresby

Omar, A., Satu Kähkönen, S. and Meagher, P. (2001) Conditions for Effective Decentralised Governance: A Synthesis of Research Findings, IRIS Center, University of Maryland, USA

Smoke, P. (2003) Decentralisation in Africa: Goals, Dimensions, Myths and Challenges, Public Admin Dev (23): 7–16

Turner, M. and Hulme, D. (1997) Governance, administration & development: Making the State Work, Palgrave New York

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) (2007) Country Programming Document Papua New Guinea 2008 – 2013, UNESCO, Apia

Yala, C. and Sanida, O. (2010) Development Planning, in: Webster. T and Duncan, L. (ed), 2010, The National Research Institute Papua New Guinea Monograph No. 41, 2010, Papua New Guinea’s Development Performance 1975–2008, The National Research Institute, Papua New Guinea

Zahid, .H, Keefer, P. and Menzies, N. (2011) How Capital Projects are Allocated in Papua New Guinean Villages: The Influence of Local Collective Action, Local-level Institutions, and Electoral Politics, World Bank, Port Moresby

FOOTNOTES

1 Decentralisation may be in the form of either devolution or deconcentration.

2 The title of president is given to heads of rural LLGs, whilst heads of urban LLGs are known as mayors.

3 The provincial administrator is the highest ranking public official in a province.

4 PNG Education System: Elementary Schools comprise of Elementary Prep, Elementary One and Elementary Two. Primary School consists of grades 3 - 8.

5 The LLGSIP is a recent addition to the list of funds and is specifically designated for LLGs.

6 Information supplied by Dreikikir District Administration finance and administration officer, October 2013, Dreikikir.

7 Health extension officer, October 2013, Dreikikier Sub Health Center, East Sepik Province, Papua New Guinea.

8 Dreikikir District Administration finance and administration officer, October 2013, Dreikikir District Office, East Sepik Province, Papua New Guinea.

9 Acting LLG manager, Dreikikir LLG, October, 2013, Drekikier LLG Chambers, East Sepik Province, Papua New Guinea. (LLG managers generally perform the function of administrative officer for an LLG.)

10 Interviewee confidential, October 2013, Drekikier, East Sepik Province, Papua New Guinea.

11 Health extension officer, Drekikier Sub Health Center, October 2013, Drekikier Sub Health Center, East Sepik Province, Papua New Guinea.

12 Interviewee confidential, October 2013, Drekikier, East Sepik Province, Papua New Guinea.

13 Former district education advisor for Ambunti-Drekikier, October 2013, Dreikikir District Office, East Sepik Province, Papua New Guinea

14 Former district education advisor for Ambunti-Dreikier, October 2013, East Spipik Province, Papua New Guinea

15 Interviewees confidential, September 2012, Drekikier, East Sepik Province, Papua New Guinea.

16 Interviewees confidential, September 2012, Drekikier, East Sepik Province, Papua New Guinea.

17 Interviewee confidential, October 2013, Dreikikir, East Sepik Province, Papua New Guinea.

18 Interviewee confidential, October 2013, Dreikikir Council Chambers, East Sepik Province, Papua New Guinea.

19 Former LLG president, Dreikikir LLG, Dreikikir Station, October 2013, Drekikier, East Sepik Province, Papua New Guinea.

20 Former LLG manager, Dreikikir LLG, Drekikier Council Chambers, October 2013, Drekikier, East Sepik Province, Papua New Guinea.

21 Interviewees confidential, September 2012, Drekikier, East Sepik Province, Papua New Guinea.

22 Health extension officer, Drekikier Sub Health Center, October 2013, Drekikier Sub Health Center, East Sepik Province, Papua New Guinea.

23 Interviewees confidential, September 2012, Drekikier, East Sepik Province, Papua New Guinea.

24 Health extension officer Drekikier Sub Health Centre, former district education advisor for Ambunti-Drekikier, Dreikikir District Administration finance and administrative officer, acting LLG manager for Dreikikir LLG, former KKG president Drekikier LLG, Dreikikir agriculture extension officer, Drekikier, East Sepik Province, Papua New Guinea.

25 Health extension officer Drekikier Sub Health Centre, former district education advisor for Ambunti-Drekikier, acting LLG manager for Dreikikir LLG, Drekikier, East Sepik Province, Papua New Guinea.

26 A former government minister who held the ministerial portfolio of minister of intergovernmental relations.