Construction Economics and Building

Vol. 25, No. 3/4

December 2025

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Exhausted Employees Do Not Leave, Disengaged Employees Do: A Case of the Indian Construction Industry

Ashish Rastogi1,Harish Kumar Singla2,*

1 NICMAR University, Pune-411045, India, professorashish@gmail.com, ORCiD: 0000-0002-2412-6770

2 NICMAR University, Pune-411045, India, hsingla25@gmail.com, ORCiD: 0000-0003-0180-1515

Corresponding author: Harish Kumar Singla, hsingla25@gmail.com

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v25i3/4.9812

Article History: Received 10/07/2024; Revised 24/05/2025; Accepted 18/06/2025; Published 05/12/2025

Citation: Rastogi, A., Singla, H. K. 2025. Exhausted Employees Do Not Leave, Disengaged Employees Do: A Case of the Indian Construction Industry. Construction Economics and Building, 25:3/4, 143–162. https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v25i3/4.9812

Abstract

The purpose of this study is to examine the mechanisms that explain how burnout mediates the relationship between job demands and turnover intention. Responses on job demands [workload (WOL) and time pressure (TPR)], burnout [exhaustion (EXH) and disengagement (DIS)], and turnover intention (TOI) were sought, employing standard measures. The valid data (N = 199), thus collected, were analyzed using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). The significant mediating effects of TPR, i.e., WOL→TPR→DIS (H02) and WOL→TPR→EXH (H03), indicate that excessive workload on construction projects enhances time pressure, which in turn leads to disengagement and exhaustion. Similarly, the significant mediating effects of EXH, i.e., WOL→EXH→DIS (H04) and TPR→EXH→DIS (H05), indicate that workplace demands lead to exhaustion; disengagement sets in later. Furthermore, the significant mediating effects of DIS, i.e., WOL→DIS→TOI (H08), TPR→DIS→TOI (H09), and EXH→DIS→TOI (H10), suggest that in the wake of excessive demands and exhaustion, employees are likely to feel disengaged and eventually consider quitting the organization. With respect to the research implications, this study attempts a multi-theoretic conceptualization following it up with comprehensive mediation analyses. With respect to the practical implications, the study findings call for actionable strategies in the domains of work design, training, and supervisor support.

Keywords

Disengagement; Exhaustion; Workload; Time Pressure; Turnover Intention

Introduction

The construction industry is widely acknowledged as being characterized by extremely challenging working conditions (Enshassi et al., 2015, Wu et al., 2019). Construction professionals are expected to take up demanding and varied workload and deliver time-bound results in resource-constrained environments (Ayalp 2021, Lingard and Francis 2006). Thus, construction professionals experience a significant physical and mental workload coupled with immense time pressure (Leung et al., 2011, Wu et al., 2019).

Such factors create a demanding work environment for construction professionals (Leung et al., 2011, Yip and Rowlinson 2009), which leads to burnout. In fact, the prevalence of burnout in the construction industry is well documented. Extant research has identified a multitude of antecedents for the onset of burnout. These antecedents emerge from aspects such as the job role and work design, organizational interactions and policies, and, finally, the interface between work and personal domain. For instance, it has been found that irregular schedule coupled with long working hours is one of the prominent reasons for burnout (Leung et al., 2007, Yip and Rowlinson 2009). Construction professionals experience extremely high workload and time pressure in demanding conditions characterized by ambiguity and conflict vis-à-vis the assigned roles (see Avila et al., 2021, Bowen et al., 2014, Ibem et al., 2011, Pinto et al., 2014, Sun et al., 2020). Furthermore, organizational factors contributing to burnout include perceived injustice, job insecurity, unfair reward and recognition policies, poor interpersonal relationships at work, and challenging work environments despite limited resources (e.g., Enshassi et al., 2016, Janssen and Bakker 2001, Leung et al., 2008, Leung et al., 2009, Lingard and Francis 2005, Yang et al., 2018). Finally, the interface between work and personal domain has also been highlighted as a reason for burnout. For example, many studies have concluded the work–family conflict or work–life imbalance is a major predictor of burnout in construction professionals (see Lingard and Francis 2006, Zheng et al., 2021).

The harmful consequences of burnout have also been well researched. Construction professionals exposed to burnout suffer from poor health (Janssen and Bakker 2001, Yang et al., 2017, Wahab 2010). Furthermore, the negative impact of burnout on adherence to safety protocols has also been documented (see Ibem et al., 2011, Poon et al., 2013). Burnout is also known to have debilitating effects on job satisfaction, interpersonal relationships, and work performance (Leung et al., 2008, Leung et al., 2011, Love and Edwards 2005). Finally, burnout leads to turnover intention (see Chih et al., 2016, Yang et al., 2017, Yip and Rowlinson 2009).

As is evident, extant literature has made significant strides in cautioning the practitioners about the multifarious causes and adverse consequences of burnout in the construction industry. Nevertheless, some research gaps remain. First, existing studies on burnout in the construction industry have extensively employed either a job demands resources model (Demerouti et al., 2001) or the conservation of resources theory (Hobfoll 1989). The broader organizational and management literature has sought synthesis in both these theoretical frameworks (e.g., Bakker and Demerouti 2007). However, they are rarely employed in conjunction in the construction context. Second, in construction literature, burnout is often understood as an event. Contrarily, research in the broader organizational and management literature informs us that burnout ought to be seen as a process, wherein the antecedents first lead to exhaustion; disengagement and other consequences follow (see Bakker et al., 2004, Leiter 1993, Rastogi et al., 2018, Dierendonck et al., 2001). To the best of our knowledge, such a conceptualization of burnout has not been reported in construction literature. Third, lacking the consideration of burnout as a process, underlying mechanisms as to how the workplace demands lead to the onset of exhaustion, followed by disengagement and other negative consequences, remain unexamined empirically. Such empirical analyses are also hampered by the employment of theoretical lenses in isolation as explained above. Finally, the studies on burnout in construction have been carried out in scattered, yet limited geographies. For example, we found empirical examinations based in Australia (e.g., Lingard and Francis 2005, 2006, Moore and Loosemore 2014); China (e.g., Sun et al., 2020, Yang et al., 2017), African countries (e.g., Bowen et al., 2014, Ibem et al., 2011, Wahab 2010), the Middle East (e.g., Enshassi et al., 2015; Enshassi et al., 2016), and European countries (e.g., Janssen and Bakker 2001, Love and Edwards 2005). Nevertheless, we did not come across such empirical examinations in India, despite its demographic and economic standing (Rastogi et al., 2020). Not only is India the most populous country, but it is also fast emerging as a major economic power.

In this backdrop, our study seeks to uncover the mechanisms that explain how burnout mediates the relationship between job demands and turnover intention. To accomplish this, the study employs (1) the job demands-resources (JD-R) model, (2) the conservation of resources (COR) theory, and (3) the process model of burnout, thereby serving the purpose of theoretical integration. Furthermore, the study employs workload and time pressure (as job demands) leading to the onset of exhaustion and disengagement (the process of burnout), finally culminating in turnover intention. To the best of our knowledge, such a comprehensive mediation analysis employing similar variables has not been reported in the construction context. Finally, our research has been carried out in India. Our study therefore makes significant conceptual, methodological, and contextual contributions in simultaneous examination of antecedents and consequences of burnout in the Indian construction industry.

Theoretical background and hypotheses specification

Mediating effects of time pressure (hypotheses 01–03)

When employees experience a depletion of resources such as energy and time due to excessive workload (WOL) and time pressure (TPR), they are likely to exhibit withdrawal behaviors such as turnover intention (TOI) (H01) and disengagement (DIS) (H02). This is in accordance with the COR theory (see Halbesleben et al., 2014. Hobfoll 1989). Furthermore, according to the JD-R model, excessive job demands such as WOL and TPR are positively associated with exhaustion (EXH) (see Bakker and Demerouti 2017, Demerouti et al., 2001), thereby giving credence to H03. Inherent in these arguments is the assumption that often excessive WOL in construction projects results in TPR owing to strict deadlines in which construction projects operate (Leung et al., 2007, Pinto et al., 2014), thereby enhancing an employee’s TOI (H01), DIS (H02), and EXH (H03). Accordingly, we hypothesize the following:

H01: Time pressure mediates the relationship between workload and turnover intention.

H02: Time pressure mediates the relationship between workload and disengagement.

H03: Time pressure mediates the relationship between workload and exhaustion.

Mediating effects of exhaustion (hypotheses 04–07)

According to the JD-R model, persistent job demands such as WOL and TPR are likely to lead to EXH (see Bakker and Demerouti 2017, Demerouti et al., 2001). As per the COR theory, when employees experience excessive job demands such as WOL and TPR, they tend to lose resources such as energy and time. To prevent a continual depletion of these resources, they are likely to withdraw either through DIS or TOI (see Halbesleben et al., 2014, Hobfoll 1989). Furthermore, EXH will trigger withdrawal behaviors in the form of DIS and TOI as a coping mechanism to prevent further resource depletion (Thanacoody et al., 2014). Finally, demands leading to EXH till DIS sets in are in line with the explanation of burnout as a process (Bakker et al., 2004, Leiter 1993). In the construction project context, job demands such as WOL and TPR are likely to lead to EXH, which in turn will lead to DIS (H04 and H05, respectively). Similarly, enhanced EXH due to high WOL and TPR could also lead to withdrawal in the form on TOI (H06 and H07, respectively). Similar contentions have been supported in the construction project contexts (Chih et al., 2016, Leung et al., 2007, Pinto et al., 2014, Yang et al., 2017). Accordingly, we hypothesize the following:

H04: Exhaustion mediates the relationship between workload and disengagement.

H05: Exhaustion mediates the relationship between time pressure and disengagement.

H06: Exhaustion mediates the relationship between workload and turnover intention.

H07: Exhaustion mediates the relationship between time pressure and turnover intention.

Mediating effects of disengagement (hypotheses 08–10)

According to the COR theory, employees overwhelmed by job demands such as WOL and TPR are likely to experience a depletion of resources such as energy and time. To arrest the loss of resources, the employees may exhibit DIS, a withdrawal behavior. Similarly, EXH will trigger DIS as a coping mechanism (see Halbesleben et al., 2014, Hobfoll 1989). EXH leading to DIS is in consonance with the process model of burnout as well (Bakker et al., 2004, Leiter 1993). Nevertheless, if their resource reservoirs are not sufficiently replenished, disengaged employees may intend to quit as well, thereby closing the loop from DIS to TOI (Hobfoll 1989, Thanacoody et al., 2014). In the construction project context, job demands such as WOL and TPR are likely to lead to DIS, which in turn will lead to TOI (H08 and H09, respectively). Similarly, enhanced DIS due to high EXH could also lead to withdrawal in the form of TOI (H10). These contentions have been supported in the construction project contexts (Chih et al., 2016, Yang et al., 2017, Yip and Rowlinson 2009). Accordingly, we hypothesize the following:

H08: Disengagement mediates the relationship between workload and turnover intention.

H09: Disengagement mediates the relationship between time pressure and turnover intention.

H10: Disengagement mediates the relationship between exhaustion and turnover intention.

Methods

Sample and procedure

The Indian construction industry is highly fragmented and unorganized. Though the construction sector is one of the largest providers of employment, only a scant minority of skilled professionals are in regular employment of a few corporations (Dixit et al., 2017, Sakthivel and Joddar 2006, Tiwary et al., 2012). Accordingly, to carry out an empirical investigation across a scarce and geographically scattered sample of construction professionals, we decided to focus on some of the largest construction companies in India. These large corporations have institutional mechanisms for training the employees in technical and managerial aspects of their respective domains. Such trainings are conducted in the form of executive development programs of varied durations at India’s leading technical and management institutions. For this study, we approached successive groups of participants in various executive development programs of a prominent construction management institute in Western India, with a request to respond to our survey. This kind of data collection strategy can be termed as snowball sampling. The data were collected in person from the respondents during their visit to the above-mentioned institute over a period of 4 months (May 2023 to August 2023), allowing for heterogeneity in affiliations, backgrounds, age, education, gender, marital status, and work experience. It must be noted that snowball sampling has inherent limitations with respect to ensuring diversity and positional and locational heterogeneity. Though authors were careful of the fact to make sure that the sample is not concentrated geographically, the respondents mainly were working on operational profiles and very few were working in managerial positions. The respondents were given an initial briefing about the survey and its purpose. At the same time, the company and the respondents were assured of anonymity. Respondents were asked to complete the questionnaire responses in one sitting.

The data collection exercise sought to collect data from approximately 300 respondents. However, we could collect a total of 211 responses during the study period. At first, we measured the intra-individual response variability (IRV). It is a measure of within-person variability (standard deviation). If the IRV values are below 0.50, it indicates that the respondent was probably not engaged and made insufficient effort in responding to the survey (Hong et al., 2020). We found 12 such responses, which were dropped from further analyses, leaving us with 199 valid responses. The sample had 45.23% participants aged between 25 and 30, 37.18% aged between 31 and 40, 8.04% aged between 41 and 50, and 9.55% participants aged above 51. All the respondents were graduates, with over 55% reporting themselves to be post-graduate or above. The sample comprised 69.35% male and 30.65% female participants. Sixty-one percent of the participants reported to be married. Finally, work experience was skewed toward young professionals with over 72% reporting having less than 10 years of experience. The demographic profile of all the respondents is reported in Table 1.

Notes: AGE = Age, EDU = Education, GEN = Gender, MRS = Marital status, WEX = Total work experience. Source: Authors’ self-compilation.

Measures

The entire questionnaire was divided into four sections.

a. Demographics

The first section collected respondents’ demographic information such as age (AGE), education (EDU), gender (GEN), marital status (MRS), and total work experience (WEX).

b. Measuring workload, time pressure, disengagement, exhaustion, and turnover intention

A five-item workload scale developed by Kirby et al. (2003) was used for measuring workload. A sample item for workload is “The workload here is too heavy”. Furthermore, the five-item time pressure scale developed by Teng et al. (2010) was adapted to measure time pressure. A sample item for time pressure is “When working, I often have limited time to finish the assigned tasks”. We used four items each, which were sourced from Demerouti et al. (2001) to measure exhaustion and disengagement. A sample item for exhaustion is “After my work, I usually feel worn out and weary”. Similarly, a sample item for disengagement is “Over time, one can become disconnected from this type of work”. Following Meyer et al. (1993), we employed three items to measure turnover intention. A sample item for turnover intention is “I often think of quitting this organization”. Responses to all perceptual variables were obtained on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Control variables

In the model, we controlled demographic variables, namely, age, education, gender, marital status, and total work experience, to partial out their effects, if any. Notwithstanding their probable empirical importance, these were not the variables of central importance in the study (Nielsena and Raswanta 2018). The demographic variables were coded as follows: AGE (0 = 21 to 30, 1 = 31 to 40, 2 = 41 to 50, 3 = 51 and above), EDU (0 = Graduate, 1 = Post-graduate and above), GEN (0 = Female, 1 = Male), MRS (0 = Unmarried, 1 = Married), and WEX (0 = 0 to 10, 1 = 11 to 20, 2 = 21 to 30 years and 3 = 31 and above).

Analysis strategy

The data were analyzed in steps. First, we examined the prerequisites such as sampling adequacy and construct reliability. Following recommendations by Hair et al. (2010), we measured the sampling sufficiency using the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure (KMO) test and measures of sampling adequacy (MSA). To measure the internal consistency of constructs, we used Cronbach’s alpha.

This study aims to simultaneously examine the relationship between theoretical constructs by building nomological networks. According to Dash and Paul (2021), structural equation modeling (SEM) is a technique used to explain multiple statistical relationships simultaneously through visualization and model validation. Complex models can be discussed simply through this technique. SEM can be defined as a combination of factor analyses and multiple regression analyses simultaneously (Sarstedt et al., 2017; Hair Jr et al., 2017a; Haenlein and Kaplan, 2004) and aims to understand the relationship between latent constructs (factors) that are generally indicated by various measures. Hence, for the second step in data analyses, it was decided to use the SEM technique (see Bollen 1989).

Though numerous statistical packages are available to study the concept of SEM, IBM SPSS Amos (analysis of moment structures) and Smart PLS (partial least squares) are the most popular ones. “The philosophical distinction between CB-SEM and PLS-SEM is that if the research objective is theory testing and confirmation, then the appropriate method is CB-SEM. In contrast, if the research objective is prediction and theory development, then the appropriate method is PLS-SEM. Conceptually and practically, PLS-SEM is similar to using multiple regression analysis. The primary objective is to maximize explained variance in the dependent constructs but additionally to evaluate the data quality based on measurement model characteristics” (Hair Jr et al., 2017a). Considering the objectives of the present study, it was decided to use PLS-SEM. Variance-based PLS-SEM is a causal-predictive approach used for confirming measurement models (Dash and Paul 2021, Hair et al., 2021). The following steps are followed for PLS-SEM (Hair et al., 2019):

1. Specify the model and examine the measurement constructs.

2. Examine the convergent and discriminant validity of constructs.

3. Assess structural models path coefficients and their fitness.

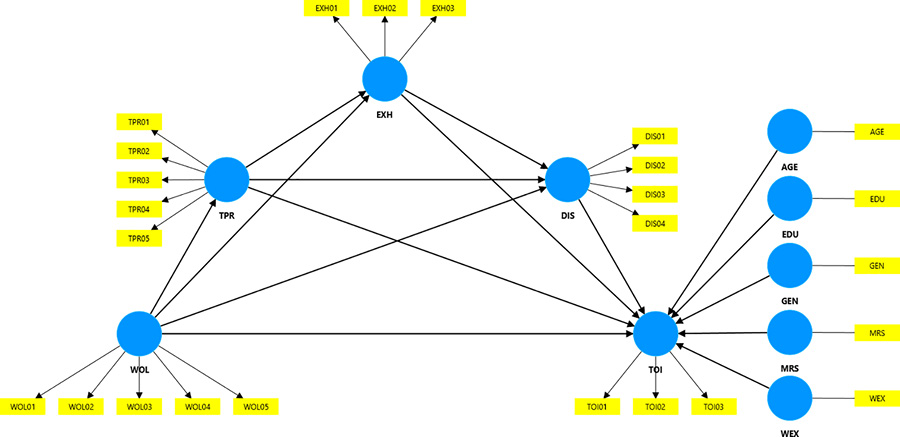

Accordingly, the model was specified based on the hypothesized relationships among the study variables (Figure 1) and measurement constructs were assessed through factor loadings. After model specification, the convergent and discriminant validity of constructs was examined. Convergent validity was examined using the values of composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE), while the discriminant validity was examined using the heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratio and the Fornell–Larcker criterion (Fornell and Cha 1994). Next, the structural model was assessed using path coefficients. Finally, we used the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) value, chi-square/df, normed fit index (NFI) value, and goodness-of-fit (GoF) index to assess model performance or fit.

Notes: WOL = Workload, TPR = Time pressure, EXH = Exhaustion, DIS = Disengagement, and TOI = Turnover intention, AGE = Age, EDU = Education, GEN = Gender, MRS = Marital status, and WEX = Total work experience.

Control variables: AGE, EDU, GEN, MRS, and WEX.

Results

Measuring sampling adequacy

As per extant guidelines, a KMO value of above 0.700 and an MSA value of above 0.500 are desirable to indicate the sampling adequacy (Hair et al., 2010). The KMO test extracted a value of 0.913 in our case. Furthermore, MSA values for all items were above the cutoff value of 0.500. A higher value of MSA indicates that an item is perfectly predicted by the other variable without error (Hair et al., 2010). Accordingly, we concluded sampling adequacy.

Measuring construct reliability

Thereafter, the initial reliability of the constructs was also measured using Cronbach’s alpha before proceeding for the PLS-SEM. The Cronbach’s alphas for the variables were as follows: workload (0.805), time pressure (0.831), exhaustion (0.775), disengagement (0.814), and turnover intention (0.889). The results are shown in Table 2.

Notes: WOL = Workload, TPR = Time pressure, EXH = Exhaustion, DIS = Disengagement, TOI = Turnover intention. Source: Authors’ self-compilation based on the output of SPSS-21.

Model specification

A minimum sample size of 150 is recommended by Hair et al. (2010), in case the model contains seven or fewer constructs and each construct has at least three items. Our data fulfill the above guideline as we have five constructs, and each construct has at least three items. Thus, a sample size of 199 is considered appropriate for data analysis using SEM. A conceptual model was specified and identified based on theoretical relationships in extant literature (Figure 1).

Assessing measurement constructs

The measurement constructs were examined through the factor loadings. Hair et al. (2019) recommend these loadings to be more than 0.708, so that the construct would explain more than 50.12% (0.708 * 0.708 = 0.5012) of the item’s variance. The factor loadings for each item were found to be more than 0.708 except for WOL03. However, for a sample greater than 100, the loading criteria can be relaxed up to 0.500 (Hair et al., 2010). Hence, we retained the item and concluded that the research constructs sufficiently explain the variance of their respective items. The results of factor loading for measurement model are shown in Table 2.

Examining construct validity

The validity of a construct can only be established if it fulfills the criteria of convergent and discriminant validity (Henseler et al., 2016). A construct is said to be convergent if it explains the variance of its items (Hair et al., 2019). The convergent validity of a construct is established if composite reliability (rho_a and rho_c) and average variance extracted (AVE) are 0.700 and 0.500, respectively, and rho_a and rho_c are greater than AVE (Hair et al., 2010). The results are reported in Table 3.

Notes: AVE = Average variance extracted, WOL = Workload, TPR = Time pressure, EXH = Exhaustion, DIS = Disengagement, TOI = Turnover intention. Source: Authors’ self-compilation based on the output of SmartPLS-4.

Examining discriminant validity

Two constructs can be refereed to be discriminant, if they exhibit low or no correlation (Hair et al., 2010). The HTMT ratio and the Fornell–Larcker criterion were used to examine the discriminant validity of constructs. The HTMT ratio is as an estimator for the correlation between two latent variables. If the HTMT value is high, discriminant validity problems are present. Thresholds of 0.850 (Kline 2011) and 0.900 (Gold et al., 2001) have been proposed. In our findings, all the values were found to be below the more conservative threshold, i.e., 0.850. The Fornell–Larcker criterion method discriminates two constructs on the basis of AVEs. If the AVE of two constructs is higher than that of the squared factor correlation between the scales, the constructs are said to be discriminant (Hair et al., 2014). We find that the values of AVE for all constructs are below the correlations with other constructs. Hence, we conclude that all the constructs are distinct and have confirmed the extant guidelines on the discriminant validity. The results are reported in Table 3.

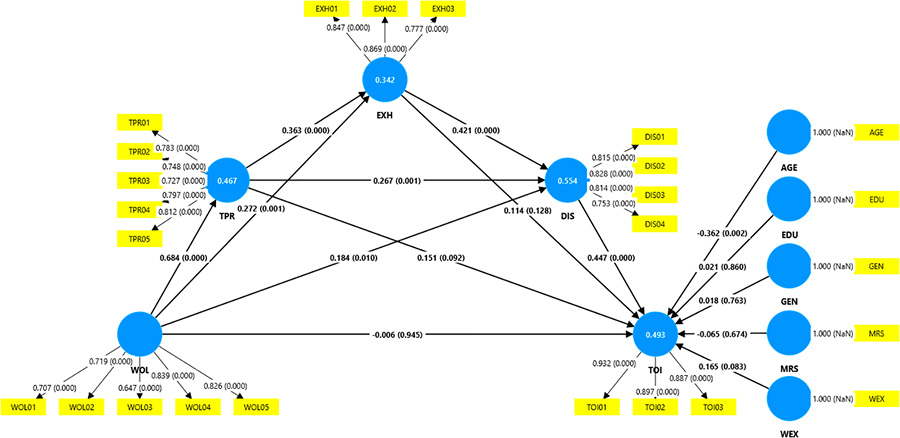

Hypothesis testing

After establishing the validity of constructs, we examined the model’s path coefficients (Table 4). As is evident, barring age, we found no effect of control variables on turnover intention. Age was found to have a significant negative effect on turnover intention, i.e., the lesser the age, higher the turnover intention. With respect to the study variables, an interesting pattern is observed. Even as workload positively predicted time pressure, exhaustion, and disengagement, it was not found to be associated with turnover intention. Similarly, time pressure was found to be positively associated with exhaustion and disengagement, but not with turnover intention. Finally, exhaustion was positively related to disengagement, but not to turnover intention. Only disengagement positively predicted turnover intention. In other words, none of the study variables barring disengagement predicted turnover intention. The structural model depicting path coefficients is presented in Figure 2.

Notes: AGE = Age, EDU = Education, GEN = Gender, MRS = Marital status, WEX = Total work experience, WOL = Workload, TPR = Time pressure, EXH = Exhaustion, DIS = Disengagement, TOI = Turnover intention. Source: Authors’ self-compilation based on the output of SmartPLS 4. **Significant at 1%; * Significant at 5%.

Notes: WOL = Workload, TPR = Time pressure, EXH = Exhaustion, DIS = Disengagement, TOI = Turnover intention, AGE = Age, EDU = Education, GEN = Gender, MRS = Marital status, and WEX = Total work experience.

Independent variables: WOL, TPR, EXH, and DIS.

Mediating variables: TPR, EXH, and DIS.

Dependent variables: TPR, EXH, DIS, and TOI.

Control variables: AGE, EDU, GEN, MRS, and WEX.

Table 5 documents the results of hypothesized mediations. Time pressure was found to mediate the relationship of workload with disengagement (H02) and exhaustion (H03), but the mediation was not supported for the relationship between workload and turnover intention (H01). Furthermore, exhaustion was found to mediate the relationships of workload and time pressure with disengagement (H04 and H05, respectively). However, no support was found for the hypothesized exhaustion mediation in the association of workload and time pressure with turnover intention (H06 and H07, respectively). Finally, disengagement was found to successfully mediate the relationships of workload, time pressure, and exhaustion with turnover intention (H08, H09, and H10, respectively). In summary, we found support for H02, H03, H04, H05, H08, H09, and H10, whereas H01, H06, and H07 were not supported.

Notes: WOL = Workload, TPR = Time pressure, EXH = Exhaustion, DIS = Disengagement, TOI = Turnover intention. Source: Authors’ self-compilation based on the output of SmartPLS 4. **Significant at 1%; * Significant at 5%.

Assessment of model fitness

A model that has the ability to reproduce the data and does not essentially necessitate re-specification (Barrett 2007) can be called a good fit model. Not attempting to optimize a unique global scalar function, PLS-SEM does not provide a comprehensive set of fit indices or measures (Henseler and Sarstedt 2013). The GoF index, which takes both the measurement and structural models’ performance into account, is a response to this limitation (Tenenhaus et al., 2004 p. 173) and makes sense in specific types of model validation (see Henseler and Sarstedt 2013). Owing to the limitations of the fit indices for PLS-SEM, fewer approximate measures like SRMR, NFI, and χ2 are reported. We used combination rules (see Hu and Bentler 1999) and reported the values of the SRMR (Henseler et al., 2014, absolute fit measure), the relative χ2 (χ2min/df; Wheaton et al., 1977), and NFI (Bentler and Bonett 1980) in Table 6. Table 7 reports the values of R2 and GoF index. PLS-SEM reports the output for both the models, i.e., the saturated model and the estimated model. The estimated model is a more restricted version, and even though there is no guideline for choosing values of saturated and estimated models, many researchers have suggested estimated model values for these measures in PLS (Hair Jr et al., 2017a, Hair Jr et al., 2017b). The fit indices for both saturated and estimated models were found to be within range. The results of Tables 6 and 7 suggest that the model is a good fit.

Notes: SRMR = Standardized root mean square residual; df = Degrees of freedom; NFI = Normed fit index. Source: Authors’ self-compilation based on the output of SmartPLS 4. *Range suggested by Hu and Bentler (1999).

| Dependent variable | R2 | GoF | Cutoff* | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DIS | 0.554 | 0.598 | 0.360 | Excellent |

| EXH | 0.342 | 0.486 | Excellent | |

| TOI | 0.492 | 0.635 | Excellent | |

| TPR | 0.467 | 0.529 | Excellent |

Notes: TPR = Time pressure, EXH = Exhaustion, DIS = Disengagement, TOI = Turnover intention. Source: Authors’ self-compilation. GoF cutoff values recommended by Wetzels et al. (2009).

Discussion and implications

This study attempted a simultaneous examination of antecedents and consequences of burnout in the Indian construction industry. A structural model rooted in (1) the JD-R model, (2) the COR theory, and (3) the process model of burnout was formulated to examine the said objective. In doing so, this research employed workload and time pressure as job demands; exhaustion and disengagement as components of burnout; and disengagement and turnover intention as withdrawal behaviors. Comprehensive mediation analyses were carried out, while controlling for the effects of demographic variables.

We found that the control variable age has a significant negative relationship with turnover intention. Other control variables, i.e., education, gender, marital status, and total work experience, were found to have no effect on turnover intention. The significant negative association of age on turnover intentions is on expected lines. Extant research has documented that younger professionals are more likely to consider quitting their jobs compared to their experienced counterparts (Borg and Scott-Young 2022). We found mixed results for the mediation hypotheses. The significant mediating effects of time pressure, i.e., workload → time pressure → disengagement (H02) and workload → time pressure → exhaustion (H03), are in line with the JD-R framework (Demerouti et al., 2001). In other words, excessive workload on construction projects enhances time pressure, which in turn leads to disengagement and exhaustion. Similarly, the significant mediating effects of exhaustion, i.e., workload → exhaustion → disengagement (H04) and time pressure → exhaustion → disengagement (H05), demonstrate the process model of burnout (see Bakker et al., 2004, Leiter 1993). In other words, workplace demands lead to exhaustion; disengagement sets in later. Furthermore, the significant mediating effects of disengagement, i.e., workload → disengagement → turnover intention (H08), time pressure → disengagement → turnover intention (H09), and exhaustion → disengagement → turnover intention (H10), are in line with conservation of resources theory (see Hobfoll 1989). In other words, in the wake of excessive demands and exhaustion, employees are likely to feel disengaged and eventually consider quitting the organization. Finally, the mediation hypotheses not supported were workload→ time pressure→ turnover intention (H01), workload → exhaustion → turnover intention (H06), and time pressure → exhaustion → turnover intention (H07). The significance of these results lies in the pattern that with the exception of disengagement, no other hypothesized mediator predicts the intention to quit of employees (see Thanacoody et al., 2014). In other words, while exhausted employees may not contemplate leaving, disengaged employees are likely to quit.

Implications for research

Our study has several implications for research. First, this study employs (1) the job demands-resources model, (2) the conservation of resources theory, and (3) the process model of burnout. This is significant because each of these models is extensively used to explain the phenomena of stress and burnout. However, they are rarely employed in conjunction. Our study therefore serves the purpose of theoretical integration. Second, employing representative variables, this study uncovers the mediation mechanisms that explain how burnout mediates the relationship between job demands and turnover intention. To accomplish this, the study employs workload and time pressure (as job demands), leading to the onset of exhaustion and disengagement (the process of burnout), and finally culminating in turnover intention. To the best of our knowledge, such a comprehensive mediation analysis employing similar variables has not been reported in the construction context. Thus, our study is both conceptually and methodologically robust. Finally, our research has been carried out in India. Not only is India the most populous country, but it is also fast emerging as a major economic power. However, despite its demographic and economic standing, studies rooted in the Indian context are few and far between (Rastogi et al., 2020). Results of our study are in line with the extant findings across various geographical contexts regarding the antecedents and consequences of burnout. Thus, our study also makes a contextual contribution by validating in the Indian context the findings of researchers in Australia (e.g., Lingard and Francis 2005), China (e.g., Sun et al., 2020), African countries (e.g., Bowen et al., 2014), the Middle East (e.g., Enshassi et al., 2015), and European countries (e.g., Janssen and Bakker 2001). Our empirical examination further highlights that the incidence of burnout is not subject to cross-cultural differences.

Implications for practice

Our findings unambiguously establish the debilitating effects of job demands on construction professionals. Workload coupled with time pressure causes both exhaustion and disengagement, separately as well as sequentially. Furthermore, the differential effects of exhaustion and disengagement on turnover intention are clearly established. While exhausted construction professionals are not likely to contemplate leaving, disengaged professionals are likely to quit. Accordingly, our research has the following practical implications. First, organizational leaders must strive to drastically improve the working environment. We add our voice to the call of Rastogi and Singla (2023) that construction leaders should seriously rethink the industry’s work design. They should consider introducing flexible work arrangements and regulating working hours in order to mitigate the negative influence of extreme workload and immense time pressure. While progress is already being made in select pockets in the developed world (see Dentons, 2024; Nichol, 2021; Rogers, 2023), such efforts must also be implemented widely across economic and geographic contexts. Second, construction leaders should actively work to provide training mechanisms to help the professionals cope with burnout. Dedicated training efforts should be made in technical, managerial, and personal effectiveness domains. For example, if construction professionals are specifically trained to manage stress and time, they are likely to be able to efficiently and effectively manage the job demands, while resisting the incidence of burnout. Finally, the supervisors must strive to maintain a cordial association with their subordinates. Support received from supervisors is likely to help the construction professionals to balance workload and well-being without compromising productivity. In other words, supportive supervisors are likely to act as a coping mechanism to exhausted professionals, possibly preventing the onset of withdrawal behaviors such as disengagement and turnover.

Limitations and future research directions

Even as this study attempted a comprehensive mediation analysis incorporating job demands, burnout, and turnover intention, it is not without its share of limitations. First, this study limited its scope only to job demands. It does not consider organizational (such as management of stakeholders) and personal demands (such as work–family conflict), which are known to cause exhaustion (see Rastogi and Singla 2023). Second, this study did not consider job, organizational, and personal resources that help employees cope with the demands in the workplace. Inclusion of resources (such as supervisor support and resilience) could have offered a more comprehensive explanation of the phenomenon. Finally, notwithstanding precedence, data collection employing the snowballing sampling technique is not a statistical sampling method. The sample size is relatively small and geographically concentrated. Accordingly, generalizability could be difficult. Furthermore, owing to the limitations of the fit indices for PLS-SEM, fewer approximate measures are reported to examine model fitness. Therefore, we call for validation studies across contexts and samples. Future research should employ a rich and varied combination of demands and resources to uncover the path mechanisms that determine the onset of burnout and its harmful consequences.

Conclusions

Burnout and its antecedents and consequences continue to remain issues of major concern for construction practitioners as well as researchers. The demanding and stressful working environment in the construction industry leads to the onset of burnout and consequent negative personal and organizational outcomes. In this backdrop, our research attempted comprehensive mediation analyses to simultaneously examine how workload and time pressure (job demands) lead to the onset of exhaustion and disengagement (the process of burnout), finally culminating in turnover intention.

In summary, our findings suggest that workload coupled with time pressure causes both exhaustion and disengagement, separately as well as sequentially. Furthermore, the differential effects of exhaustion and disengagement on turnover intention are clearly established. While exhausted construction professionals are not likely to contemplate leaving, disengaged professionals are likely to quit. Determined efforts on the part of construction leaders are required in order to arrest the incidence of burnout and prevent its detrimental consequences. Specifically, we have recommended flexible work arrangement and regulation of work hours in the construction industry. Furthermore, dedicated training efforts are needed in technical, managerial, and personal effectiveness domains, to enable construction professionals to perform their jobs effectively while managing the accompanying stress. Finally, we call for enhanced interaction and support from the concerned supervisors as a coping mechanism for exhausted construction professionals, thereby preventing withdrawal in the form of disengagement and turnover.

Data availability statement

Some or all data, models, or code that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Avila, J., Rapp, R., Dunbar, S., and A. Jackson. 2021. Burnout and Work life in Disaster Restoration: Maslach Burnout Inventory and Areas of Work life Survey. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 147 (2), 04020171. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0001986

Ayalp, G.G. 2021. Critical predictors of burnout among civil engineers at construction sites: a structural equation modelling. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 29 (9), pp. 3547-3573. https://doi.org/10.1108/ECAM-12-2020-1066

Bakker, A. B., and E. Demerouti. 2007. The Job Demands-Resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22 (3), pp. 309–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115

Bakker, A.B., and E. Demerouti. 2017. Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22 (3), pp. 273-85. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000056

Bakker, A.B., Demerouti, E., and W. Verbeke. 2004. Using the job demands‐resources model to predict burnout and performance. Human Resource Management: Published in Cooperation with the School of Business Administration. The University of Michigan and in alliance with the Society of Human Resources Management, 43 (1), pp. 83-104. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20004

Barrett, P. 2007. Structural equation modelling: adjudging model fit. Personality and Individual Differences, 42 (5), pp. 815-824. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.09.018

Bentler, P.M., and D.G. Bonett. 1980. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88 (3), pp. 588-606. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.88.3.588

Borg, J., and C.M. Scott-Young. 2022. Contributing factors to turnover intentions of early career project management professionals in construction. Construction Management and Economics, 40 (10), pp. 835-853. https://doi.org/10.1080/01446193.2022.2110602

Bowen, P., Edwards, P., Lingard, H., and K. Cattell. 2014. Predictive modelling of workplace stress among construction professionals. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 140 (3), 04013055. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0000806

Chih, Y.-Y., Kiazad, K., Zhou, L., Capezio, A., Li, M., and S. Restubog 2016. Investigating employee turnover in the construction industry: A psychological contract perspective. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 142 (6), 04016006. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0001101

Dash, G. and Paul, J. 2021. CB-SEM vs PLS-SEM Methods for Research in Social Sciences and Technology Forecasting. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 173 (3), 121092. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121092

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A.B., Nachreiner, F., and W.B. Schaufeli. 2001. The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86 (3), pp. 499-512. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.86.3.499

Dentons. 2024. Will a four-day week work for construction? [Online] 18 October. Available at: https://www.dentons.com/en/insights/articles/2024/october/18/will-a-four-day-week-work-for-construction (Accessed: 14 April 2025).

Dixit, S., Pandey, A.K., Mandal, S.N., and S. Bansal. 2017. A study of enabling factors affecting construction productivity: Indian scenario. International Journal of Civil Engineering & Technology, 8 (6), pp. 741-758.

Enshassi, A., Swaity, E. AL., and F. Arain. 2016. Investigating common causes of burnout in the construction industry. The International Journal of Construction Management, 8 (1), pp. 43–56.

Enshassi, A., El-Rayyes, Y., and S. Alkilani. 2015. Job stress, job burnout and safety performance in the Palestinian construction industry. Journal of Financial Management of Property and Construction, 20 (2), pp. 170-187. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMPC-01-2015-0004

Fornell, C., and J. Cha. 1994. Partial Least Squares. In: R. Bagozzi, Ed., Advanced Methods of Marketing Research, Blackwell, Cambridge, pp. 52-87.

Gold, A.H., Malhotra, A., and A.H. Segers. 2001. Knowledge Management: An Organizational Capabilities Perspective. Journal of Management Information Systems, 18 (1), pp. 185-214. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.2001.11045669

Hair, J. F., Jr., Babin, B. J., and N. Krey. 2017b. Covariance-based structural equation modeling in the Journal of Advertising: Review and recommendations. Journal of Advertising, 46 (1), pp. 163–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2017.1281777

Hair, J. F., Matthews, L., Matthews, R., and M. Sarstedt. 2017a. PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated guidelines on which method to use. International Journal of Multivariate Data Analysis, 1 (2), pp. 107–123. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMDA.2017.087624

Hair, J., Hult, G.T.M., Ringle, C., and M. Sarstedt. 2014. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling PLS-SEM. SAGE Publications, Incorporated, Los Angeles.

Hair, J., Black, W., Babin, B.Y.A., Anderson, R., and R. Tatham. 2010. Multivariate Data Analysis. A Global Perspective. Pearson Prentice Hall, New Jersey, NJ.

Hair, J.F., Hult, G.T.M., Ringle, C.M., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N.P., and S. Ray. 2021. An introduction to structural equation modelling. In: Partial least squares structural equation modeling PLS-SEM Using R. Classroom Companion: Business, Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-80519-7_1

Hair, J.F., Jeff, R., Marko, S., and R. Christian. 2019. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31 (1), pp. 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

Halbesleben, J.R., Neveu, J.P., Paustian-Underdahl, S.C., and M. Westman. 2014. Getting to the COR understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. Journal of Management, 40 (5), pp. 1334-1364, https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314527130

Haenlein, M., Kaplan, A.M. 2004. A beginner’s guide to partial least squares analysis. Understanding Statistics, 3 (4), pp. 283–297. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328031us0304_4

Henseler, J., Dijkstra, T. K., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., Diamantopoulos, A., Straub, D. W., Ketchen, D. J., Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., and R.J. Calantone. 2014. Common Beliefs and Reality about Partial Least Squares: Comments on Rönkkö & Evermann 2013. Organizational Research Methods, 17 (2), pp. 182-209. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428114526928

Henseler, J., Hubona, G., and P.A. Ray. 2016. Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: updated guidelines. Industrial Management and Data Systems, 116 (1), pp. 2-20. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-09-2015-0382

Henseler, J., and M. Sarstedt. 2013. Goodness-of-fit indices for partial least squares path modelling. Computational Statistics, 28 (2), pp. 565–580. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00180-012-0317-1

Hobfoll, S.E. 1989. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44 (3), pp. 513-524. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513

Hong, M., Steedle, J.T., and Y. Cheng. 2020. Methods of detecting insufficient effort responding: comparisons and practical recommendations. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 80 (2), pp. 312-345. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164419865316

Hu, L., and P.M. Bentler. 1999. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6 (1), pp. 1-55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Ibem, E., Anosike, M., and D.M.T. Azuh. 2011. Work stress among professionals in the building construction industry in Nigeria. Australasian Journal of Construction Economics and Building, 11 (3), pp. 45-57. https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v11i3.2134

Janssen, P., and A.J. Bakker. 2001. A test and refinement of the demand–control–support model in the construction industry. International Journal of Stress Management, 8 (4), pp. 315-332. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1017517716727

Bollen, K. 1989. A new incremental fit index for general structural equation models. Sociological Methods & Research, 17 (3), pp. 303–316. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124189017003004

Kirby, J. R., Knapper, C. K., Evans, C. J., Carty, A. E., and C. Gadula. 2003. Approaches to learning at work and workplace climate. International Journal of Training and Development, 7 (1), pp. 31-52. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2419.00169

Kline, R.B. 2011. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. Third Edition, New York: The Guilford Press.

Leiter, M.P. 1993. Burnout as a developmental process: consideration of models. in Schaufeli, W.B., Maslach, C. and Marek, T. Eds, Professional Burnout: Recent Developments in Theory and Research, Taylor & Francis, Washington, DC, pp. 237-250.

Leung, M., Chan, Y.-S., and J. Yu. 2009. Integrated model for the stressors and stresses of construction project managers in Hong Kong. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 135 (2), pp. 126-134. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9364(2009)135:2(126)

Leung, M., Chan, S.I.Y., and C. Dongyu. 2011. Structural linear relationships between job stress, burnout, physiological stress, and performance of construction project managers. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 18 (3), pp. 312-328. https://doi.org/10.1108/09699981111126205

Leung, M.Y., Chan, Y.S., and P. Olomolaiye. 2008. Impact of stress on the performance of construction project managers. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 134 (8), pp. 644-652. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9364(2008)134:8(644)

Leung, M.Y., Sham, J., and Y.J. Chan. 2007. Adjusting stressors–job-demand stress in preventing rust out/burnout in estimators. Surveying and Built Environment, 18 (1), pp. 17-26.

Lingard, H., and V. Francis. 2006. Does a supportive work environment moderate the relationship between work-family conflict and burnout among construction professionals? Construction Management and Economics, 24 (2), pp. 185-196. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697010500226913

Lingard, H., and V. Francis. 2005. Does work-family conflict mediate the relationship between job schedule demands and burnout in male construction professionals and managers? Construction Management and Economics, 23 (7), pp. 733–745. https://doi.org/10.1080/01446190500040836

Love, P.E.D., and D.J. Edwards. 2005. Taking the pulse of UK construction project managers’ health: Influence of job demands, job control and social support on psychological wellbeing. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 12 (1), pp. 88-101. https://doi.org/10.1108/09699980510576916

Meyer, J.P., Allen, N.J., and C.A. Smith. 1993. Commitment to organizations and occupations: Extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78 (4), pp. 538-551. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.78.4.538

Moore, P. and M. Loosemore. 2014. Burnout of undergraduate construction management students in Australia. Construction Management and Economics, 32 (11), pp. 1066-1077. https://doi.org/10.1080/01446193.2014.966734

Nichol, S. 2021. Making construction a great place to work: Can flexible working help? [PDF] London: Timewise. Available at: https://timewise.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/TW-Making-construction-a-great-place-to-work-report.pdf (Accessed: 14 April 2025).

Nielsena, B.B., and A. Raswanta. 2018. The selection, use, and reporting of control variables in international business research: a review and recommendations. Journal of World Business, 53 (6), pp. 958-968. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2018.05.003

Pinto, J. K., Dawood, S., and M.B. Pinto. 2014. Project management and burnout: Implications of the Demand-Control–Support model on project-based work. International Journal of Project Management, 32 (4), pp. 578–589. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2013.09.003

Poon, S.W., Rowlinson, S.M., Koh, T., and Y. Deng. 2013. Job burnout and safety performance in the Hong Kong construction industry. International Journal of Construction Management, 13 (1), pp. 69-78. https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2013.10773206

Rastogi, A., and H.K. Singla. 2023. Exploration of exhaustion in early-career construction professionals in India. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/ECAM-10-2022-0938

Rastogi, A., Pati, S.P., Kumar, P., and J.K. Dixit. 2020. Development of a ‘Karma-Yoga’ instrument, the core of the Hindu work ethic. IIMB Management Review, 32 (4), pp. 352-364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iimb.2019.10.013

Rastogi, A., Pati, S.P., Dixit, J.K., and P. Kumar. 2018. Work disengagement among SME workers: evidence from India. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 25 (3), pp. 968-980. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-07-2017-0189

Rogers, D. 2023. How Sir Robert McAlpine introduced flexible working to construction sites. [Online] 21 February. Available at: https://www.building.co.uk/building-the-future-commission/how-sir-robert-mcalpine-introduced-flexible-working-to-construction-sites/5121668.article (Accessed: 14 April 2025).

Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C.M., Hair, J.F., 2017. Partial least squares structural equation modeling. Handbook of Market Research, 26 (1), 1–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-05542-8_15-1

Sakthivel, S., and P. Joddar. 2006. Unorganised sector workforce in India: trends, patterns and social security coverage. Economic and Political Weekly, 41 (21), pp. 2107-2114.

Sun, M., Zhu, F., and X. Sun. 2020. Influencing factors of construction professionals’ burnout in China: a sequential mixed-method approach. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 27 (10), pp. 3215-3233. https://doi.org/10.1108/ECAM-02-2020-0106

Tenenhaus, M., Amato, S., and V. Esposito. 2004. A global goodness-of-fit index for PLS structural equation modelling. In: Proceedings of the XLII SIS scientific meeting, pp. 739–742.

Teng, C.I., Hsiao, F.J., and T.A. Chou. 2010. Nurse‐perceived time pressure and patient‐perceived care quality. Journal of Nursing Management, 18 (3), pp. 275-284. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2010.01073.x

Thanacoody, P.R., Newman, A., and S. Fuchs. 2014. Affective commitment and turnover intentions among healthcare professionals: The role of emotional exhaustion and disengagement. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25 (13), pp. 1841-1857. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.860389

Tiwary, G., Gangopadhyay, P.K., Biswas, S., Nayak, K., Chatterjee, M.K., Chakraborty, D., and S. Mukherjee. 2012. Socio-economic status of workers of building construction industry. Indian Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 16 (2), pp. 66-71. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5278.107072

Dierendonck, V. D., Schaufeli, W.B., and B.P. Buunk. 2001. Toward a process model of burnout: Results from a secondary analysis. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 10 (1), pp. 41-52. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320042000025

Wahab, A. 2010. Stress management among artisans in construction industry in Nigeria. Global Journal of Researches in Engineering, 10 (1), pp. 93-103.

Wetzels, M., Odekerken-Schröder, G., and C. Van Oppen. 2009. Using PLS path modeling for assessing hierarchical construct models: Guidelines and empirical illustration. MIS Quarterly, 33 (1), pp. 177-195. https://doi.org/10.2307/20650284

Wheaton, B., Muthén, B., Alwin, D.F., and G.F. Summers. 1977. Assessing reliability and stability in panel models. In: Heise D ed Sociological methodology, Jossey-Bass, Washington, DC, pp. 84–136. https://doi.org/10.2307/270754

Wu, G., Hu, Z., and J. Zheng. 2019. Role stress, job burnout, and job performance in construction project managers: the moderating role of career calling. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16 (13), pp. 1-20. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16132394

Yang, F., Li, X., Li, Y., Zhu, Y., and C. Wu. 2017. Job burnout of construction project managers in China: A cross-sectional analysis. International Journal of Project Management, 35 (7), pp. 1272–1287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2017.06.005

Yang, F., Li, X. Song, Z., and Y. Li. 2018. Job burnout of construction project managers: Considering the role of organizational justice. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 144 (11), 04018103. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0001567

Yip, B., and S. Rowlinson. 2009. Job Burnout among Construction Engineers Working within Consulting and Contracting Organizations. Journal of Management in Engineering, 25 (3), pp. 122-130. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0742-597X(2009)25:3(122)

Zheng, J., Gou, X., Li, H., Xia, N., and G. Wu. 2021. Linking work–family conflict and burnout from the emotional resource perspective for construction professionals. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, 14 (5), pp. 1093-1115. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMPB-06-2020-0181