Construction Economics and Building

Vol. 25, No. 3/4

December 2025

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Evaluation of Variation Orders on Road Construction Projects in Rural Nepal

Madhav Prasad Koirala1,2,*, Nabin Thapa3, Om Prakash Giri1, Raj Kapur Shah4

1 Formerly: Pokhara University, Faculty of Science and Technology, School of Engineering, Pokhara Metropolitan City 30, Gandaki Provence, Nepal

2 Now: United Technical College, Bharatpur Metropolitan City-11 Bagmati Provence. Nepal

3 Mid-Western University, Graduate School of Engineering, Birendranagar, Surkhet, Karnali Provence, Nepal

4 Liverpool John Moores University, R307, Peter Jost Building, Byrom St, Liverpool, L3 3AF UK

Corresponding author: Madhav Prasad Koirala, mpkoirala@pu.edu.np,

m.koirala@unitedtechnicalcollege.edu.np

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v25i3/4.9756

Article History: Received 27/04/2025; Revised 21/05/2025; Accepted 15/09/2025; Published 05/12/2025

Citation: Koirala, M. P., Thapa, N., Giri, O. P., Shah, R. K. 2025. Evaluation of Variation Orders on Road Construction Projects in Rural Nepal. Construction Economics and Building, 25:3/4, 311–338. https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v25i3/4.9756

Abstract

Variation orders (VOs) contribute to time and cost overruns in Nepalese road projects and often trigger disputes. This mixed-methods study examined the causes of VOs on rural roads in Karnali Province using a targeted literature review, field observations, document review, case studies of 11 client–contractor–consultant projects (located for geographic spread, contractor size, and presence/absence of consultant oversight), and a closed-ended census survey of industry professionals across the three stakeholder groups. Quantitative analysis used the Relative Importance Index (RII) and descriptive statistics to compare stakeholder perceptions; qualitative evidence from site observations and documents triangulated the results. The findings identified variations in scope of work (additions, omissions, and alterations in employer requirements) as the primary cause (RII clients = 812; RII consultants = 780; RII contractors = 791). Secondary causes vary by stakeholder: clients and contractors rank “change in design and drawings by consultant” highly (RII 0.800), while consultants and contractors emphasize “errors and omissions in design” (RII consultants = 933; RII contractors = 864). Other contributors include inadequate site investigation, adverse site conditions, government intervention, and client-initiated changes. Stakeholders differ on causes but largely agree on effects and mitigation strategies. The study’s originality is its stakeholdercomparative mixed-methods focus on Karnali rural roads, producing empirically grounded, actionable mitigation measures. Improving scope definition, completing designs, and strengthening early site investigation can substantially reduce VOs. The paper recommends coordinated national research led by academic and professional bodies, in partnership with government and industry, to develop standardized guidance and capacity-building.

Keywords

Variation Order; Cost Variation; Time Variation; Causes; Impacts

Introduction

As Nepal transitioned to a federal system of government, the central government shifted political authority and development emphasis to the provinces, which accelerated road construction nationwide. Federalism empowered provinces to access local infrastructure requirements, and development has made uneven strides. Karnali Province, Nepal’s remotest and topographically difficult region, has fallen behind in rising investment. Its steep topography, loose soils, and weathered land are softened by the technical challenges that even the best plans cannot resolve easily. Limited institutional capacity and a lack of experienced project managers, engineers, and surveyors exacerbate the challenge faced by governments in planning, monitoring, and adjusting projects in low- and middle-income countries. Compounding it all is the prevalence of variation orders (VOs), formal changes to the contracted scope of work that are almost ubiquitous and regrettably widely considered as “normal”. Empirical research reveals continual unrestrained variations evidenced by cost overruns, project delay, and contractual problems (Borowy, 2013; Francis et al., 2022; Pillai et al., 2002). Although VOs are extensively studied throughout the world (Abd El-Karim et al., 2017), technical uncertainty, weak governance, and sociopolitical influence in remote, risk-prone zones like Karnali are still inadequately researched. This disparity is significant: strategies that work in lowland or urban emergencies where access to sites is stable, resources are relatively settled, and data sources are reliable fall short in settings experiencing the ever-changing hazards and the political realities of facility operations.

The Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and Urban Development (MoPIUD) is responsible for road development in Karnali. Institutional problems and environmental turbulence continue to plague MoPIUD projects. Poor feasibility studies, underestimating geotechnical risks, and inadequate supervision of site investigations lead to technical design problems that only become apparent during widespread implementation, often requiring costly mid-design revisions.

Political intervention may override technical counsel, altering alignments or scope enlargement without corresponding resource increases. Environmental hazards such as landslides, flash floods, and seasonal erosion threaten project progress. In such conditions, VOs help keep projects viable rather than serving only as corrective measures (H. K. Doloi, 2011; H. Doloi et al., 2012a; Sewell et al., 2019a). It is too great a risk; two districts are fully cut off from Nepal’s road network, underscoring the price of development in delay and inefficiency (Weingast, 2009).

Studies worldwide have identified various reasons for VOs, such as design errors, stakeholder-requested changes, or procurement problems (Aziz and Abdel-Hakam, 2016; Ghorasainee, 2019). Nonetheless, most of these studies examine settings with stable governance, similar site conditions, and stronger contract enforcement. Very few examine the interactions of geologic risk and governance weakness together. Recent literature highlights this gap. Heyns and Banick (2024) noted the lack of VO-based development research in South Asia to prevent the inappropriate transfer of irrelevant models. Mukherjee et al., (2023) advocated for a collaborative, technology-supported solution (e.g., remote sensing, digital progress monitoring, and online communication) that will develop resilience. With the road weaving over hills and down river valleys in Karnali, these tools could predict landslides, survey bank erosion, and give engineers a heads-up to respond.

In Nepal’s mountain provinces, locally limited empirical data create constraints on decision-making at policy and project levels. Without local data, contracts, contingency plans, and design standards may rely on assumptions that fail in practice. This study explored this gap by systematically investigating wants for VO causes and impacts and VO prevention in all 10 districts of Karnali Province. This research employed a mixed-methods approach that included a literature review to position the problem in the context of international and regional theory, case studies of 11 MoPIUD projects to reflect local realities, and a survey to garner responses from engineers, contractors, and administrators.

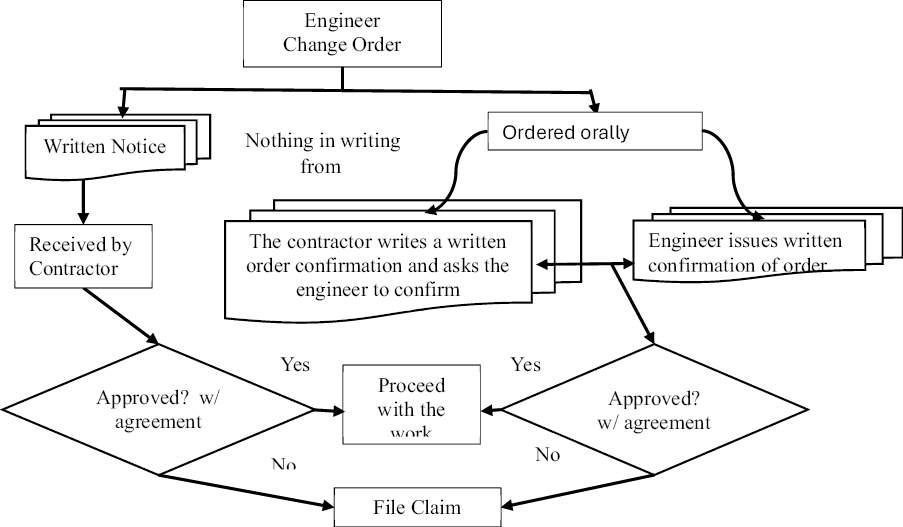

Karnali geophysical instability is a long-term cause of VOs. On the Karnali Highway and other trunk roads, rainstorms during the monsoons cause slope collapses and riverbank erosion, and flash floods sweep away partly built works. Such events necessitate rapid redesigning, reshaping road sections, enhancing drainage, or strengthening structures, all of which create VOs (Corominas et al., 2014). Nepal’s legal framework delineates sequential approval and conflict resolution processes as shown in Figure 1, but in practice, safety and continuity often require spontaneous field adjustments before formal authorization.

Figure 1. Conceptual flowchart of variation orders in construction project

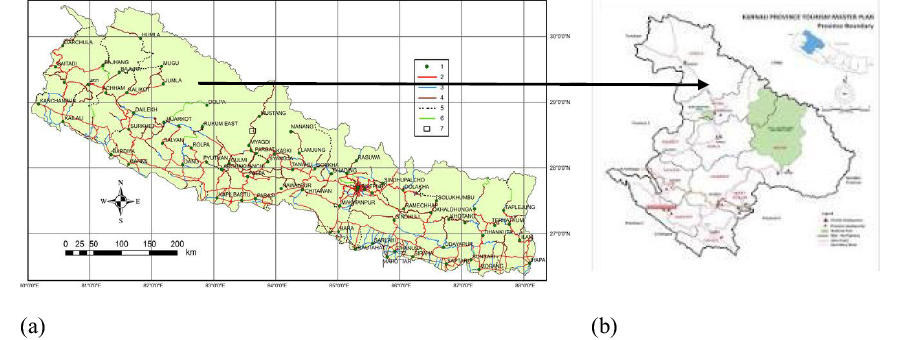

As mentioned in Figure 2, repeated natural disasters impact building times, severing access, inundating sites, and undermining foundations. With such a climate, VO management must be forward-looking and strategic rather than reactionary (Sidle and Ziegler, 2025). This involves incorporating flexibility into contracts, setting aside contingency budgets, and allowing site teams to implement swift, technically sound adaptations. Studying VO dynamics in one of Nepal’s most geophysical and institutionally challenging regions shows that VO management systems cannot be applied universally without adapting to the local context. The results are of dual significance: theoretically, they contribute to the understanding of how environmental ambiguity and limitations in governance structure interact to initiate project change; practically, they can be used to guide contract design, early warning systems, and institutional capacity-building for infrastructure delivery in similarly challenging environments around the world. The goal is not to eliminate change, an impossibility in Karnali, but to channel it as a controlled, open, and constructive process supporting public infrastructure successes.

Figure 2. (a) Karnali Highway obstructed due to landslides. (b) Karnali Highway blockade due to floods and landslides. (c) Karnali Highway blockade due to scoring. (d) Karnali Highway at the Rocky Mountains

Theoretical/literature review

On construction projects, the variation orders come more often with well-established consequences of delays in the scheduling, budget overruns, cash flow challenges, and defects in the quality (Koirala and Shahi, 2024a; Sobaih et al., 2024). Variation management has always played a major role in project success due to scarce resources, difficult logistics, and challenging site conditions on rural highway projects such as those in Karnali Province. In situations like building rural highways in Karnali Province, a rural area with scarce resources, logistical challenges, and difficult site conditions, effective VO management has a significant impact on the success of the project.

From the literature, this research identifies five essential factors that impact variation orders, namely (1) client and consultant behavior, (2) contractor capacity, (3) environmental and external factors, (4) project management processes, and (5) systemic and regulatory environments. All five factors work together to determine the occurrence and effect of variation orders on a project. In unison, they determine to what degree variation orders affect a project.

1. Client and consultant issues

Scope changes requested by the clients, design changes, or additional work requested, without conducting a rigorous technical evaluation in most cases, are the most frequent contributors to VOs (D’Astous et al., 2004; Maqbool and Rashid, 2017). Consultants can also produce incomplete or conflicting design documents or sometimes do not carry out investigations on-site. Failures in drawing coordination occur. These problems interfere with the planned work sequence and require variations (Oloo et al., 2014; Dosumu and Aigbavboa, 2017).

2. Contractor capability and management

The competence of contractors directly affects VO occurrence. Inadequate site supervision, defects in construction, and mismanagement of resources are usually accompanied by remedial work and contract variations (H. Doloi et al., 2012b; Koirala and Shahi, 2024b). Inefficient subcontractors and a low-skilled workforce can compound these deficiencies.

3. External factors and environmental conditions

Several external factors can affect construction contracts beyond the parties’ control. Unfavorable weather conditions, unanticipated ground conditions, political interference, budgetary uncertainty, material shortages, and price fluctuations can lead to spontaneous variation orders (Alshihri et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2024). All these issues create uncertainty, which increases the chance of variation orders.

4. Shortcomings in project management and planning

When planning for the project is poor, when there is weak communication between stakeholders, and when risk management is inadequate or ignored, variation orders will be high. Some studies have suggested that effective advance planning and evaluation could eliminate as much as 75% of variations (Harrison and Lock, 2017; Williams et al., 2019).

5. Systemic and regulatory issues

The construction manuals tend to be inadequately written at the organizational level. There are many fuzzy definitions of the performance-based constraints used. Weak enforcement of provisions is one of the other factors that contribute to ineffective VO avoidance (Arain and Pheng, 2005b; Sohail and Cavill, 2008; Pires, 2011). While performance-based design–build agreements can promote innovation, they can also help to take on too much specificity, making verification a challenge (Järvenpää et al., 2022). Methodologies such as the Last Planner System (LPS) may increase constructability, productivity, and scheduling reliability when properly supported (Shehab et al., 2023; Wangchuk et al., 2024).

This study used a multi-domain model where variation orders arise from interactions among stakeholder decisions, contractor characteristics, external pressures, management processes, and organizational rules, as shown in Figure 3. The integrative model provides a systematic way of seeing how individual factors combine to produce performance at the project level rather than just listing causes.

Figure 3. Proposed conceptual model of investigation

Materials and methods

This study investigated the causes and impacts of VOs in Nepal’s Karnali Province Road construction works. It utilized a mixed quantitative and qualitative approach through questionnaires, case studies, interviews, field visits, and document reviews to gather data from contractors, consultants, and government clients.

As shown in Figure 4, the research process proceeds from a problem statement and literature review to objectives, methodology design, sampling, data collection, data analysis, and data presentation. The research aimed to investigate the causes and impacts of VOs in Karnali Road projects, together with the extent of stakeholder agreement. A mixed-methods approach was employed: quantitative data from stakeholder questionnaires with scaled answers and qualitative data from interviews, site visits, and document analysis. Analysis focused on VO causes and effects as perceived by contractors, consultants, and public clients.

Karnali Province, one of Nepal’s seven provinces comprising 10 districts with Birendranagar as headquarters, served as the study setting. The MoPIUD implemented nine road projects in Karnali as contextual cases. A province map highlighting Karnali was used to orient readers to the setting, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Research study area. (a, b) Map of Nepal and Karnali Province. Source: Nepal Road Network, Government of Nepal (GoN).

Table 1 provides a summary of the nine road and infrastructure projects being conducted in the Dailekh, Jumla, Surkhet, Rukum, Mugu, and Salyan districts of the MoPIUD, which include culverts, gabion walls, roadside improvements, blacktop works, airport road packages, and rural road works. The implementing agencies were the Road Offices and Infrastructure Development Offices (IDOs) and different contractors, as well as subcontractors.

Note: MoPIUD, Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and Urban Development; IDO, Infrastructure Development Office.

Population, frame, and sampling representativeness

The population of interest includes stakeholders involved in the MoPIUD road projects under implementation during the study period in Karnali Province: (i) contractors/subcontractors working on these projects, (ii) consultants engaged in design or supervision, and (iii) public clients/owners overseeing projects at federal, provincial, and local levels.

The sampling frame was developed using MoPIUD rosters, IDOs, and project documents from nine focal projects, i.e., creating a line list of personnel and their respective titles in the projects. Using a census approach, 21 contractors/subcontractors, 28 consultants, and 17 clients/owners (exposed to VO-related work) were identified as shown in Table 2. The coverage against the rosters for the violations and meeting records was checked to ensure that coverage and follow-up (e-mail, telephone, and site visits) were conducted to ensure that there was no nonresponse. It was assured that the respondent profiles were as close to matching the frame as possible, with only slight imbalances that were adjusted using post-stratification weighting, which did not involve any shifting of rankings. Inclusion required more than 3 years of experience in that sector and any involvement in a VO-affected project that was formed.

Data collection

Primary data were collected using structured questionnaires with a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never to 5 = always) to capture perceived frequency/importance of VO causes and effects. Focused interviews and field visits were conducted to contextualize survey responses and clarify item interpretation. Secondary data comprised MoPIUD records and project documents, complemented by publicly available reports and academic literature, to describe the project context, verify VO incidence, and support triangulation, instrument development, quality control, and preprocessing. Questionnaire items were adapted from prior construction management studies that employed the Relative Importance Index (RII) for factor ranking, with alignment to Nepalese contract and practice contexts (Kometa et al., 1994; Sambasivan and Soon, 2007). Expert review and a pilot test refined wording and response scale clarity. Internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) was assessed by construct, and pilot debriefs were used to confirm item comprehension. Responses were screened for missingness, straight-lining, and outliers. Minimal missing data were managed by listwise deletion at the item level; simple imputation was explored in sensitivity checks to ensure robustness.

Data analysis

• Relative Importance Index

The RII is a method that ranks causes and effects using ordinal Likert responses. It is widely used in construction research to compare differences in perceptions both across stakeholder groups and within groups (Kometa et al., 1994; Sambasivan and Soon, 2007). Logically, let A denote the highest scale weight (A = 5), N the number of respondents for that item, W the Likert weight (Oloo et al., 2014; Dhakal, 2024), and f the frequency count of responses for weight W. Thus, RII was computed as RII = ∑ (W × f)/A × N, normalized. RII values range from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating greater perceived frequency or importance. The RII results were reported for the overall sample as well as by individual stakeholder groups, together with their respective item rankings. Where feasible, estimation uncertainty was quantified using 95% bootstrap confidence intervals (1,000 resamples).

The rationale and assumptions for RII are that ordinal Likert responses are treated approximately as an interval for purposes of averaging, that respondents interpret items consistently, and that item-level response counts are sufficient for reliable estimation. A recognized limitation of RII is sensitivity to group-specific scale use and potential masking of dispersion; to mitigate these concerns, we (i) report group-wise RII and ranks, (ii) complement mean-based indices with rank-based summaries, and (iii) conduct sensitivity checks using medians and post-stratified weights.

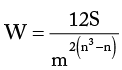

• Kendall’s coefficient of concordance (W)

To assess the degree of agreement in rankings of VO factors among contractors, consultants, and clients, Kendall’s coefficient of concordance (W) was computed. Let m be the number of rater groups (m = 3) and n the number of items (VO factors). For each item, the rank sums across groups were calculated, and the mean rank sum R̄ was obtained; tie corrections were applied where required. The resulting W ranges from 0 (no agreement) to 1 (perfect agreement) and provides a single omnibus measure of concordance across the three stakeholder groups. The formula is given as S = ∑(Rj−R̄)2 and  . Approximate significance tests for W were reported as df = (n−1) χ2 = m(n−1)W. Since a single concordance coefficient does not indicate which items contribute to the disagreement, W was examined and increased using pairwise Spearman’s rank correlations between stakeholder groups and subgroup rank tables to establish where divergence occurred. Assumptions underlying this procedure are that all groups rank the same item set, that ranks are ordinal and independent across groups, and that ties are handled appropriately. To further ensure robustness, sensitivity analyses were performed by re-ranking items using median-based ordinal scores and alternative tie treatments; these checks produced orderings consistent with the RII-based results. Representativeness was addressed through post-stratification by stakeholder group and district to reflect frame proportions; this adjustment did not materially change qualitative conclusions or the identity of top-ranked factors.

. Approximate significance tests for W were reported as df = (n−1) χ2 = m(n−1)W. Since a single concordance coefficient does not indicate which items contribute to the disagreement, W was examined and increased using pairwise Spearman’s rank correlations between stakeholder groups and subgroup rank tables to establish where divergence occurred. Assumptions underlying this procedure are that all groups rank the same item set, that ranks are ordinal and independent across groups, and that ties are handled appropriately. To further ensure robustness, sensitivity analyses were performed by re-ranking items using median-based ordinal scores and alternative tie treatments; these checks produced orderings consistent with the RII-based results. Representativeness was addressed through post-stratification by stakeholder group and district to reflect frame proportions; this adjustment did not materially change qualitative conclusions or the identity of top-ranked factors.

Data analysis and results

The questionnaire consisted of employees of the Infrastructure Development Directorate (IDD)/IDO of the Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and Urban Development, Karnali Province, and contractors and consultants operating in the province. The causes of variation orders were assessed using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never to 5 = always) and ranked according to their RII.

Figure 6 shows the ranked reasons for VOs from the perspective of owners and clients. The figure shows that incomplete drawings at the bidding stage, too little pre-construction planning, and unclear project briefs are consistently ranked as the most significant drivers. This indicates that deficiencies in project preparation on the part of the clients, in terms of providing the needed information, have direct consequences on scope changes and alterations in review and design. We are ultimately interpreting the rankings to mean that greater success in identifying improvement significance and priority will substantially reduce VO prevalence and project costs and schedule overruns. If we can improve project briefs, make sure our designs are complete and ready for tendering, and maximize early coordination, we will observe significant reductions in VOs and their associated costs.

Figure 6. Ordering reasons for variation related to owners and clients

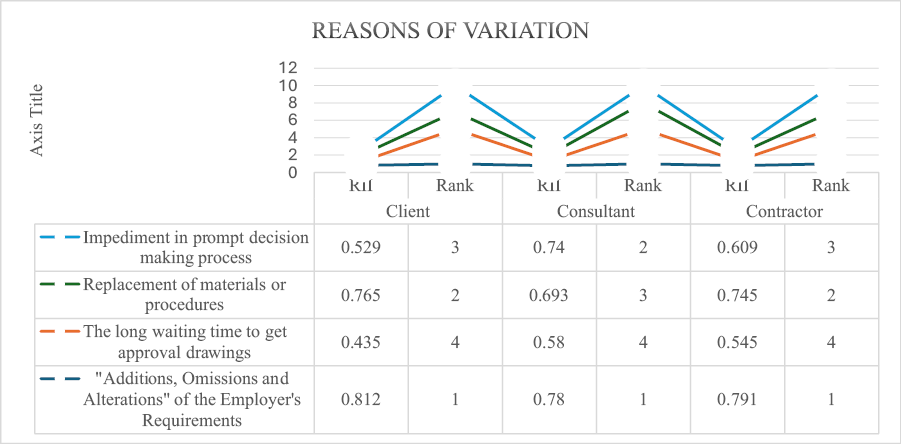

Table 3 shows agreement on two major sources of variation orders: design errors/omissions and inexperience of the design team. Contractors and clients prioritized change orders due to consultant-driven design changes, consultants pointed to conflicts in contract documents, and service contractors provided unique insights indicating that utility standards were compromised. Each stakeholder performs a specific function in the project.

In Table 4, contractor-related factors that change the construction process were rated the highest for both consultants and contractors, which reveals shared concern about inefficiencies within the process. Clients emphasized contractor profit and workmanship and connected them directly to quality control and cost overruns.

In Table 5, we observed that contractors and clients identified beneficiary initiatives as the primary external cause of variation, while consultants highlighted land and resettlement aspects, indicative of their greater involvement in pre-construction planning. All groups considered design errors and omissions, as well as lack of design team experience, to be important drivers of variation, reinforcing the importance of the quality of design in the project. Contractors and clients considered changes to design and drawings initiated by the consultant to be the most disruptive to construction, while consultants favored the incoherence of instructions in the contract documents, which was consistent with their contractual obligations. Stakeholders generally agreed on design-related causes, but their views varied by role, indicating the need for better coordination in design, documentation, and decision-making. Kendall’s W showed only moderate agreement, which reflects the disjointed thinking of the stakeholders.

Case studies

This research used case studies to identify the primary causes and impacts of variation orders on selected road projects under the MoPIUD, Karnali Province. Information was obtained from MoPIUD offices and double-checked with contractors’ and consultants’ reports.

As shown, nine projects across 17 packages were studied, with site variations occurring in 11 locations listed in Table 6, presenting 11 construction projects detailing their owners, contractors, causes of variations, and types of variations.

Note: IDD, Infrastructure Development Directorate.

Causal explanation of variation orders

Apart from descriptive reporting, the analysis indicates that variations were most frequently caused by (i) unforeseen site conditions such as landslides and high water tables, (ii) incomplete drawings and design revisions, (iii) scope variations due to land acquisition issues, and (iv) resource movement between overlapping projects. All these causative factors add up to systemic issues in the planning and design stages rather than to occasional project-specific anomalies. For instance, additional excavation and gabion works within Jumla projects were undertaken because of unexpected landslide risks, whereas the exclusion of walkway construction within Surkhet was directly linked to unresolved land acquisition disputes.

Triangulation with survey findings

The triangulation gap exists by connecting case study outcomes and survey evidence. The survey results given in Table 7 consistently ranked “preparation of drawings at the bidding stage” and “ensuring adequate pre-construction planning” as the first and second remedies, respectively. This is supported by the case studies, which detailed that inadequate designs and poor pre-site investigations were prevalent causes of VOs (e.g., Projects 4 and 5). Similarly, the survey ranked “resolving land acquisition issues prior to construction” as a concern, which aligns with the Surkhet case in which land disputes resulted in an altered project scope.

Again, cross-validation between methods increases our confidence in our results, and as shown in Table 7, there is consistency across both qualitative case data and quantitative survey perceptions that points to similar causal agents.

Impact of variation orders

Variation orders typically result in overrunning time delays, which push the project completion date back, and budget overruns, which increase the overall project cost.

The lines of evidence shown in Tables 8 and 9 indicate that variation orders typically lead to cost increases (up to 15%) and schedule extensions (up to 86%) on projects. Both the case study findings and survey opinions indicate “schedule delay” and “increase in cost” as the two largest impacts, which further strengthen our findings. Therefore, to remedy the above problems, appropriate management of VOs in Karnali Province should rely on addressing both technical and institutional gaps. Greater project pre-construction planning, including full designs, comprehensive site investigations, and leveraging technology [geographic information system (GIS) and light detection and ranging (LiDAR)], will assist in lessening design VOs. Institutional reform will be focused on empowering the provincial contemporary design offices, facilitating the approval process, and introducing transparent digital systems to inhibit political influence and development delays. Introducing standard VO clauses with fair risk-sharing, contractor incentives for effective VO use, and staff training on accountability will improve transparency and enhance VO management performance. At a policy level, an approach to prohibit provincial VO guidance consistent with national acts and a centralized VO database will assist evidence-based VOs. All these institutional and technical opportunities will assist in lessening unnecessary variations, monitoring cost and time overruns, and improving resilience around projects.

Source: Karnali Province, MOPIUD.

Note: VO, variation order.

Source: Karnali Province, MOPIUD.

Impact of variation orders on road projects in Karnali Province

A case study of MoPIUD road projects in Karnali Province indicated that variation orders led to increases in both costs (Table 8) and duration (Table 9). Stakeholders recommended solutions for these increases, including pre-tender drawings, enhanced pre-construction planning processes, designing with similar budget constraints, improved teamwork through the design and construction team, and ensuring communication effectiveness, along with some group-specific issues.

Schedule overruns occurred between 6.7% and 86%, as illustrated in Table 9. Notably, there were large delays with the remote, geologically unstable projects (for example, Pina Balai Gamgadi Jumla and Airport to Bulbule Mugu). There were smaller project delays in projects that were less remote or complex. These conclusions illustrate that terrain, site conditions, and capacity gaps within institutions result in project delays. The rest of the data suggest that project delays are due to complications and that value for money (VfM) depends on planned controls, full engagement by all stakeholders, and realistic contingencies, leading to delays that are process-based rather than purely number-based when considering the extent of technical issues involved or governance.

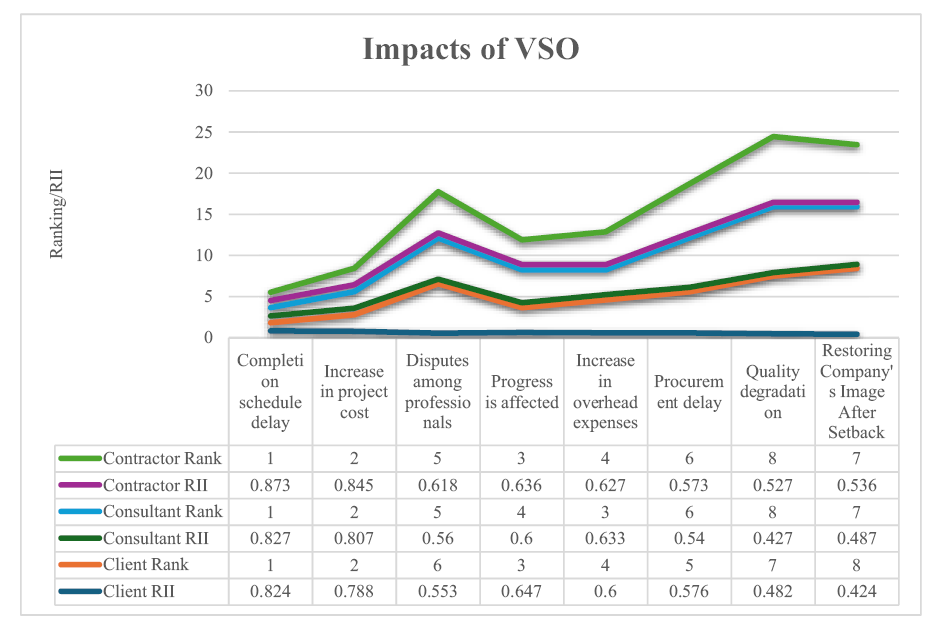

Impacts of variation orders

Figure 7 consolidates stakeholder perceptions (clients, consultants, and contractors) on the impact of VOs. In all stakeholder categories, participants ranked cost increase and time delay as two of the most significant effects, including resources and quality as lower priorities. The differences in contractor, client, and consultant stakeholder rankings likewise contribute to a richer understanding of priorities for the various stakeholders. For instance, contractors ranked constructability and labor management higher than other stakeholder groups. Conversely, consultants tended to rank compliance and coordination lower. Comparing rankings of different impacts shows that managing VOs means managing multiple stakeholders. In addition, it involves clearly defined risk-sharing mechanisms, transparency in communication, and a well-considered balancing of cost, time, and quality.

Figure 7. Impact and ranking of variation orders according to the opinions of clients, consultants, and contractors

Agreement test: Kendall’s coefficient of concordance assessed group-wise and overall rankings.

• H0: No agreement among respondent groups on the causes of variation orders.

• H1: Agreement exists among respondent groups.

Kendall’s W for the owners/clients, consultants, contractors, and external environment factors is reported in Table 10 and measures the extent of agreement in each respondent group. The strong agreement (W = 791–0.978) across groups on the ranking of factors associated with variation orders indicates areas of considerable agreement among stakeholder groups. Consultants had the strongest degree of consensus compared to owners and contractors. The findings displayed here illustrate where stakeholders largely hold the same perceptions on what identified factors are the most significant to variation orders, and likewise, there are minor distinctions in the item factors based on respondents’ corresponding roles. The move toward agreement quantification in the reporting of the results takes us a step further than just description, and the results clearly illustrate that even though agreement has been established, strategies to mitigate variation orders can be formed at a broader understanding of stakeholder priority while still addressing stakeholders’ concerns.

Agreement test on variation orders

Kendall’s coefficient of concordance was used to check agreement among groups of respondents with respect to both the impacts and causes of variation orders. All groups of respondents rated the completion of drawings at the tender stage as the most important impact, followed by sufficient pre-site planning, with the intention to reduce budget-aligned design/specifications. They also rated improvement in communication. Agreement was found to be lost for some of the other impacts. The same test was also performed with respect to the causes of variation orders and again showed both agreement and divergence among the groups. The null and alternative hypotheses being tested were as follows:

• H0: No agreement between groups.

• H1: Agreement does exist between groups.

From Table 11, we can observe that Kendall’s W (0.968) for the ranked impacts of variation orders shows a very strong agreement among clients, consultants, and contractors. This agreeableness suggests that all participants perceive the high-impact consequences of VOs to be the same elements, namely, cost increase, schedule delays, and resource issues. The implications of this simple descriptive reporting impact how mitigation strategies should target high-impact consequences and give us a mutual basis for coordinated strategic action across stakeholders.

• H0: There is no agreement on measures to minimize variation orders among groups.

• H1: Agreement on the measures exists among groups.

Rank-order correlation on measures to reduce variation orders:

Kendall’s W for clients, consultants, and contractors is shown in Table 12 and is 0.924, indicating that these groups of respondents agreed strongly in the ranking of measures to avoid variation orders. The value of the test statistic at 36.045 is greater than the tabulated value at 22.362, confirming sufficient statistical evidence that the level of concordance was significant. Concordance implied that all three stakeholder groups were able to agree on priority mitigations and, therefore, provide a shared understanding for coordinated actions. Furthermore, supplemental to a descriptive report of the data, these results signal that mitigation can be targeted and undertaken based on these topline high-priority initiatives that everyone has collectively recognized, which should improve the efficiency and value talked about in VO management.

Discussion

Rather than repeating descriptive rankings, this discussion explains why VOs endure in Karnali Province and what reforms they demand. We used a context, capability, coordination lens: (1) rugged topography and remoteness drive uncertainty, (2) institutional and technical capacity shape design and decision quality, and (3) multi-actor coordination determines responsiveness to change. This frame links local evidence to global scholarship and to practicable governance and procurement reforms.

• Scope volatility

Scope volatility in Karnali is not a generic “top cause” but a foreseeable consequence of mountainous terrain, geologic instability, and constrained access: frequent landslides, shifting ground, and weak logistics make ex ante information imperfect, enlarging contingencies and prompting additions, omissions, and design changes. This extends global findings that scope change fuels VOs (Halwatura and Ranasinghe, 2013; Alzubi et al., 2023) by showing that severe topography magnifies scope risk and that staged investigation and flexible designprocurement bundles (e.g., staged site investigations, GIS/LiDAR, and flexible specifications) are preferable to attempts to eliminate scope change entirely (Corominas et al., 2014; Gnyawali et al., 2020; Leijten, 2017).

• Consultant capacity

Consultant errors, omissions, and delayed design revisions reflect structural capacity shortfalls—compressed preparation periods and under-resourced provincial design offices—that produce incomplete designs, as documented in comparable settings (Enshassi et al., 2010; Carrillo et al., 2013; Nguyen et al., 2023). In Karnali, these capacity gaps compound terrain-driven uncertainty, increasing VO incidence and pointing to reforms such as independent design review for complex corridors, mandated geotechnical baselines, and procurement that rewards robust design.

• Coordination and governance

Divergent stakeholder priorities, contractors and clients stressing material substitution and constructability, and consultants highlighting decision bottlenecks signal coordination failures under Nepal’s decentralized governance (Giri et al., 2025). Local bodies often lack technical and digital capacity for timely approvals, while line agencies face incentive misalignment and political interference (Gnyawali et al., 2020; Noruwa et al., 2022). Fragmented accountability yields only moderate consensus (captured by Kendall’s W) (Sudusinghe and Seuring, 2025). Remedies include time-bound approval workflows, transparent digital clearance trails, and escalation protocols codified in the public procurement act (PPA)/public procurement regulation (PPR) to convert ad hoc engagement into enforceable decision rights.

• Contractororiginated variations

Contractor-originated VOs—method changes, workmanship defects, and profit-driven adjustments—arise from market imbalances. Governance should therefore shape the market: strengthen prequalification (financial capacity and staff retention), calibrate performance securities, adopt incentive-compatible payments (e.g., milestone payments tied to quality), and selectively use design–build or early contractor involvement on geotechnically uncertain corridors to share risk and reduce late variations (Oyewobi et al., 2016; Uzzi, 2020).

• Resettlement and social pressure

External pressures, resettlement disputes, and beneficiary interventions are central in Karnali. Complex land tenure and sociopolitical mobilization render a right of way fluid (Mahat, 2019). Front-loading social license through negotiated easements, realistic compensation, and community monitoring reduces later changes; institutionalizing these steps in project readiness gates aligns practice with international best practice and curbs construction-phase VOs (Notess et al., 2021; Panday et al., 2021; Abougamil et al., 2024).

• Planning and design quality (policy implication)

Strengthening planning and design is essential to curb VOs in transport projects. For mountainous corridors, agencies should adopt staged investigations supported by geotechnical baseline reports (Cascetta and Cartenì, 2014; Paudyal et al., 2023; Said et al., 2024). An independent designreview panel for Category A roads, adequate resourcing of provincial design offices, and wider use of quality and cost based selection (QCBS), with attention to long-term maintenance and design completeness, will raise standards and lower variation costs (Han et al., 2019; Roy et al., 2024).

• Decision rights and approval governance (policy implication)

Governance must clarify decision rights and impose time-bound processes. The PPA/PPR should specify VO approval timelines and mandate electronic VO modules with audit trails to limit political interference and boost transparency (H. K. Doloi, 2011; Sewell et al., 2019b). Defining provincial and local decision authority and maintaining a single, accessible decision log will streamline approvals and remove duplication.

• Procurement and contractor market development (policy implications)

Procurement reform should cultivate a stronger contractor market: stringent prequalification (financial standing, equipment, and in-house QA/QC), limits on cascading subcontracting, and performance-based incentives and penalties. For highuncertainty projects, risk-sharing contracts should be adopted (target price with pain/gain or new engineering contract (NEC)-style options), and VO clauses on admissibility and valuation should be standardized to reduce disputes (Ahmed, 2020; Akram et al., 2022; Pillai et al., 2002).

• Stakeholder engagement (policy implication)

Stakeholder engagement must be tied to project milestones, forums at design freeze, right-of-way readiness, and utility relocation before a notice to proceed, and resettlement governance strengthened with community verification and grievance redress timelines (Iskandarani, 2023). These measures align participation with readiness and reduce executionphase delays and conflicts.

• Conceptual contribution

This study advances VO literature by showing how extreme topography and decentralized governance jointly amplify VO likelihood and duration: terrain creates uncertainty, capacity shortfalls translate uncertainty into design defects, and weak coordination escalates defects into costly delays and variations. Addressing VOs in Karnali, therefore, requires better technical information and clarified decision rights (Arain and Pheng, 2005a; Narayanan et al., 2020; Amzafi et al., 2024; Shugran and Ghazali, 2024; Cadaval-Sampedro et al., 2025; Castañeda et al., 2025).

In sum, while global trends mirror the drivers of VOs in Karnali, Nepal’s distinctive geography, institutional capacity constraints, and governance arrangements render VOs more frequent and consequential. Integrating technical improvements with system-level governance reforms is therefore essential to minimize cost overruns and delays in provincial infrastructure development.

Ethics statement

The research described in the article adheres to ethical standards and guidelines. Any experiments involving human subjects or animals have been conducted with the necessary ethical approvals and informed consent.

Author contributions

The authors confirm significant contributions to the conception, design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation of this article.

Originality and plagiarism

This work is original, unpublished elsewhere, with all external sources properly cited. No plagiarism or unethical use of intellectual property is present.

Compliance with journal guidelines

The submission follows all editorial policies, and required permissions have been obtained.

Authorship order

The order of authorship reflects the relative contributions of each author to the research. The lead author takes responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the work.

Data availability statement

The authors will make data and supplementary materials available upon request, with any data restrictions outlined in the article.

Conclusions and recommendations

This study sought to assess the reasons for and implications of variation orders in road construction projects in Karnali Province, Nepal, through a review of the literature, a survey, and a case study. There are some lessons that can be replicated from the world and some that are province-specific.

Overall findings substantiate that variation orders usually arise from scope changes, design errors, and incoordination between the parties. These factors have been ongoing in foreign literature and were prominent in this study as well.

Site-specific lessons show how Karnali’s mountains, lack of connectivity, and lack of professional capacity create more variation orders. Unstable geology and frequent landslides require constant scope change, and decentralized governance means there are delays and sometimes roadblocks to decisions. Likewise, the limited small contractors influenced by local politics and limited institutional capacity within provincial offices increased issues around quality and resource management.

Karnali variation orders were observed to significantly increase costs and time overruns, which brings attention to the need for implementing targeted interventions.

Recommendations should therefore be based on an explicit priority framework, as follows:

• Improve design quality: Invest in provincial design staff training and resources to minimize drawing mistakes.

• Improve project governance: Simplify approvals and improve organizational decisions to reduce unnecessary project delays.

• Improve contractor performance: Improve contractor capacity, qualification, and monitoring to limit profit-motivated alterations.

• Minimize external risk: Conduct early community engagement, consultations, and resettlement planning to decrease additional risks of conflict.

• Improve integrated planning: Promote timely integrated interactions between clients, consultants, and contractors and develop accurate estimates that do not exceed the prescribed project scope.

• National collaboration: Develop national guidelines and conduct collaborative capacity-building research and development studies that involve government, industry, and academics.

References

Abd El-Karim, M. S. B. A., Mosa El Nawawy, O. A., & Abdel-Alim, A. M. (2017). Identification and assessment of risk factors affecting construction projects. HBRC Journal, 13(2), 202–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hbrcj.2015.05.001

Abougamil, R. A., Thorpe, D., & Heravi, A. (2024). A BIM Package with a NEC4 Contract Option to Mitigate Construction Disputes in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Buildings, 14(7), 2009. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14072009

Ahmed, M. N. (2020). The use of performance-based contracting in managing the outsourcing of a reliability-centered maintenance program: A case study. Journal of Quality in Maintenance Engineering, 26(4), 526–554. https://doi.org/10.1108/JQME-02-2018-0007

Akram, R., Thaheem, M. J., Khan, S., Nasir, A. R., & Maqsoom, A. (2022). Exploring the Role of BIM in Construction Safety in Developing Countries: Toward Automated Hazard Analysis. Sustainability, 14(19), 12905. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912905

Alshihri, S., Al‐gahtani, K., & Almohsen, A. (2022). Risk Factors That Lead to Time and Cost Overruns of Building Projects in Saudi Arabia. Buildings, 12(7), 902. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings12070902

Alzubi, K. M., Alkhateeb, A. M., & Hiyassat, M. A. (2023). Factors affecting the job satisfaction of construction engineers: evidence from Jordan. International Journal of Construction Management, 23(2), 319–328. https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2020.1867945

Amzafi, N. H., Ishak, S. A., Rahim, M. A., Amlus, M. H., Rani, H. A., Syammaun, T., Mokhtar, H., & Ayob, A. (2024). A Systematic Review of The Causes and Effects of Variation Orders in Sustainable Construction in Developing Countries. International Journal of Integrated Engineering, 16(4), 188–203. https://doi.org/10.30880/ijie.2024.16.04.023

Arain, F. M., & Pheng, L. S. (2005a). How design consultants perceive potential causes of variation orders for institutional buildings in Singapore. Architectural Engineering and Design Management, 1(3), 181–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/17452007.2005.9684592

Arain, F. M., & Pheng, L. S. (2005b). The potential effects of variation orders on institutional building projects. Facilities, 23(11–12), 496–510. https://doi.org/10.1108/02632770510618462

Aziz, R. F., & Abdel-Hakam, A. A. (2016). Exploring delay causes of road construction projects in Egypt. Alexandria Engineering Journal, 55(2), 1515–1539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aej.2016.03.006

Borowy, I. (2013). Defining sustainable development for our common future: A history of the world commission on environment and development (Brundtland Commission). Defining Sustainable Development for Our Common Future: A History of the World Commission on Environment and Development (Brundtland Commission), 1–261. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203383797

Cadaval-Sampedro, M., Herrero-Alcalde, A., Lago-Peñas, S., & Martinez-Vazquez, J. (2025). Extreme events and the resilience of decentralised governance. Regional Studies, 59(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2023.2255627

Carrillo, P., Ruikar, K., & Fuller, P. (2013). When will we learn? Improving lessons learned practice in construction. International Journal of Project Management, 31(4), 567–578. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2012.10.005

Cascetta, E., & Cartenì, A. (2014). A Quality-Based Approach to Public Transportation Planning: Theory and a Case Study. International Journal of Sustainable Transportation, 8(1), 84–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/15568318.2012.758532

Castañeda, K., Sánchez, O., Herrera, R. F., & Mejía, G. (2025). Deficiencies causes in road construction scheduling: Perspectives from construction professionals. Heliyon, 11(2), e41514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e41514

Corominas, J., van Westen, C., Frattini, P., Cascini, L., Malet, J. P., Fotopoulou, S., Catani, F., Van Den Eeckhaut, M., Mavrouli, O., Agliardi, F., Pitilakis, K., Winter, M. G., Pastor, M., Ferlisi, S., Tofani, V., Hervás, J., & Smith, J. T. (2014). Recommendations for the quantitative analysis of landslide risk. Bulletin of Engineering Geology and the Environment, 73(2), 209–263. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-013-0538-8

D’Astous, P., Détienne, F., Visser, W., & Robillard, P. N. (2004). Changing our view on design evaluation meetings methodology: A study of software technical review meetings. Design Studies, 25(6), 625–655. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2003.12.002

Dhakal, A. P. (2024). An Analysis on Domestic Tourism Development Prospective in Karnali Province, Nepal. NPRC Journal of Multidisciplinary Research, 1(4), 12–30. https://doi.org/10.3126/nprcjmr.v1i4.70941

Doloi, H. K. (2011). Understanding stakeholders’ perspective of cost estimation in project management. International Journal of Project Management, 29(5), 622–636. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2010.06.001

Doloi, H., Sawhney, A., Iyer, K. C., & Rentala, S. (2012a). Analysing factors affecting delays in Indian construction projects. International Journal of Project Management, 30(4), 479–489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2011.10.004

Doloi, H., Sawhney, A., Iyer, K. C., & Rentala, S. (2012b). Analysing factors affecting delays in Indian construction projects. International Journal of Project Management, 30(4), 479–489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2011.10.004

Dosumu, O. S., & Aigbavboa, C. O. (2017). Impact of Design Errors on Variation Cost of Selected Building Project in Nigeria. Procedia Engineering, 196, 847–856. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2017.08.016

Enshassi, A., Arain, F., & Al-Raee, S. (2010). Causes of variation orders in construction projects in the Gaza Strip. Journal of Civil Engineering and Management, 16(4), 540–551. https://doi.org/10.3846/jcem.2010.60

Francis, M., Ramachandra, T., & Perera, S. (2022). Disputes in Construction Projects: A Perspective of Project Characteristics. Journal of Legal Affairs and Dispute Resolution in Engineering and Construction, 14(2), 04522007. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)LA.1943-4170.0000535

Ghorasainee, S. (2019). Contextualizing alternative development perspectives in local governance systems and communities of Nepal. Journal of Advances in Humanities and Social Sciences, 5(6), 277–288. https://doi.org/10.20474/jahss-5.6.5

Giri, O. P., Pahari, A., & Lamichhane, B. D. (2025). An assessment of construction delay management: A Nepalese perspective. Edelweiss Applied Science and Technology, 9(5), 2157–2168. https://doi.org/10.55214/25768484.v9i5.7420

Gnyawali, K. R., Zhang, Y., Wang, G., Miao, L., Pradhan, A. M. S., Adhikari, B. R., & Xiao, L. (2020). Mapping the susceptibility of rainfall and earthquake triggered landslides along China–Nepal highways. Bulletin of Engineering Geology and the Environment, 79(2), 587–601. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-019-01583-2

Halwatura, R. U., & Ranasinghe, N. P. N. P. (2013). Causes of Variation Orders in Road Construction Projects in Sri Lanka. ISRN Construction Engineering, 2013(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/381670

Han, Y., Jin, R., Wood, H., & Yang, T. (2019). Investigation of Demographic Factors in Construction Employees’ Safety Perceptions. KSCE Journal of Civil Engineering, 23(7), 2815–2828. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12205-019-2044-4

Harrison, F., & Lock, D. (2017). Advanced project management: A structured approach. In Advanced Project Management: A Structured Approach. Taylor and Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315263328

Heyns, A. M., & Banick, R. (2024). Optimisation of rural roads planning based on multi-modal travel: a multi-service accessibility study in Nepal’s remote Karnali Province. Transportation, 51(2), 567–613. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11116-022-10343-3

Iskandarani, H. (2023). Improving Post-Conflict Housing Reconstruction Projects by Strengthening Stakeholder Engagement During the Project Planning Stage.

Järvenpää, A. T., Larsson, J., & Eriksson, P. E. (2022). How public client’s control systems affect contractors’ innovation possibilities. Construction Innovation, 24(7), 83–101. https://doi.org/10.1108/CI-03-2022-0054

Koirala, M. P., & Shahi, R. S. (2024a). Examining the causes and effects of time overruns in construction projects promoted by rural municipalities in Nepal. Evaluation and Program Planning, 105, 102436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2024.102436

Koirala, M. P., & Shahi, R. S. (2024b). Examining the causes and effects of time overruns in construction projects promoted by rural municipalities in Nepal. Evaluation and Program Planning, 105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2024.102436

Kometa, S. T., Olomolaiye, P. O., & Harris, F. C. (1994). Attributes of UK construction clients influencing project consultants’ performance. Construction Management and Economics, 12(5), 433–443. https://doi.org/10.1080/01446199400000053

Leijten, M. (2017). What lies beneath: Bounded manageability in complex underground infrastructure projet. In TU Delft University. https://doi.org/10.4233/UUID:82981CE2-E734-440F-91E6-061E568125DC

Mahat, K. B. (2019). Role of non-governmental organization in development of Nepal: the civil society index (CSI) perspective in Karnali Zone. http://archive.nnl.gov.np:8080/handle/123456789/209

Maqbool, R., & Rashid, Y. (2017). Detrimental changes and construction projects: Need for comprehensive controls. International Journal of Project Organisation and Management, 9(2), 154–170. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJPOM.2017.085291

Mukherjee, M., Abhinay, K., Rahman, M. M., Yangdhen, S., Sen, S., Adhikari, B. R., Nianthi, R., Sachdev, S., & Shaw, R. (2023). Extent and evaluation of critical infrastructure, the status of resilience and its future dimensions in South Asia. Progress in Disaster Science, 17, 100275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pdisas.2023.100275

Narayanan, S., Balasubramanian, S., Swaminathan, J. M., & Zhang, Y. (2020). Managing uncertain tasks in technology-intensive project environments: A multi-method study of task closure and capacity management decisions. Journal of Operations Management, 66(3), 260–280. https://doi.org/10.1002/joom.1062

Nguyen, F. B. T., Grigg, N., & Valdes-Vasquez, R. (2023). Electric utility construction: Causes and types of field change orders. Electricity Journal, 36(8), 107332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tej.2023.107332

Noruwa, B. I., Arewa, A. O., & Merschbrock, C. (2022). Effects of emerging technologies in minimising variations in construction projects in the UK. International Journal of Construction Management, 22(11), 2199–2206. https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2020.1772530

Notess, L., Veit, P., Monterroso, I., Andiko, Sulle, E., Larson, A. M., Gindroz, A. S., Quaedvlieg, J., & Williams, A. (2021). Community land formalization and company land acquisition procedures: A review of 33 procedures in 15 countries. Land Use Policy, 110, 104461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104461

Oloo, D. D., Munala, G., & Githae, W. (2014). Factors contributing to variation orders: A survey of civil engineering construction projects in Kenya. International Journal of Social Sciences and Entrepreneurship, 1 (12), 696-709. http://ijsse.org/articles/ijsse_v1_i12_696_709.pdf

Oyewobi, L. O., Jimoh, R., Ganiyu, B. O., & Shittu, A. A. (2016). Analysis of causes and impact of variation order on educational building projects. Journal of Facilities Management, 14(2), 139–164. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFM-01-2015-0001

Panday, U. S., Chhatkuli, R. R., Joshi, J. R., Deuja, J., Antonio, D., & Enemark, S. (2021). Securing land rights for all through fit-for-purpose land administration approach: The case of Nepal. Land, 10(7), 744. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10070744

Paudyal, P., Dahal, P., Bhandari, P., & Dahal, B. K. (2023). Sustainable rural infrastructure: guidelines for roadside slope excavation. Geoenvironmental Disasters, 10(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40677-023-00240-x

Pillai, A. S., Joshi, A., & Rao, K. S. (2002). Performance measurement of R and D projects in a multi-project, concurrent engineering environment. International Journal of Project Management, 20(2), 165–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0263-7863(00)00056-9

Pires, R. R. C. (2011). Beyond the fear of discretion: Flexibility, performance, and accountability in the management of regulatory bureaucracies. Regulation and Governance, 5(1), 43–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-5991.2010.01083.x

Roy, D., Kalidindi, S. N., & Menon, A. (2024). Economic and Institutional Factors Influencing the Selection of Project Delivery Models for Built Heritage Conservation in India. Historic Environment: Policy and Practice, 15(3), 281–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/17567505.2024.2381276

Said, D., Foda, A., Abdelhalim, A., & Elkhedr, M. (2024). Performance—Based Route Selection for Mountainous Highways: A Numerical Approach to Addressing Safety, Hydrological, and Geological Aspects. Applied Sciences (Switzerland), 14(13), 5844. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14135844

Sambasivan, M., & Soon, Y. W. (2007). Causes and effects of delays in Malaysian construction industry. International Journal of Project Management, 25(5), 517–526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2006.11.007

Sewell, S. J., Desai, S. A., Mutsaa, E., & Lottering, R. T. (2019a). A comparative study of community perceptions regarding the role of roads as a poverty alleviation strategy in rural areas. Journal of Rural Studies, 71, 73–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.09.001

Sewell, S. J., Desai, S. A., Mutsaa, E., & Lottering, R. T. (2019b). A comparative study of community perceptions regarding the role of roads as a poverty alleviation strategy in rural areas. Journal of Rural Studies, 71, 73–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.09.001

Shehab, L., Al Hattab, M., Khalife, S., El Samad, G., Abbas, Y., & Hamzeh, F. (2023). Last Planner System Framework to Assess Planning Reliability in Architectural Design. Buildings, 13(11), 2684. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13112684

Shugran, A. A., & Ghazali, F. E. M. (2024). Understanding the effects of variation orders on construction project success: insights from the Jordanian context. International Journal of Construction Management. https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2024.2337238

Sidle, R. C., & Ziegler, A. D. (2025). Balancing Development and Sustainability: Lessons from Roadbuilding in Mountainous Asia. Sustainability (Switzerland), 17(7), 3156. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073156

Sobaih, A. M. H. ; E. E., Shen, W., Xue, J., Ismaeil, E. M. H., Elnasr, A., & Sobaih, E. (2024). A Proposed Model for Variation Order Management in Construction Projects. Buildings, 14(3), 726. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14030726

Sohail, M., & Cavill, S. (2008). Accountability to Prevent Corruption in Construction Projects. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 134(9), 729–738. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9364(2008)134:9(729)

Sudusinghe, J. I., & Seuring, S. (2025). The practitioner perspective is more complete: analysing supply chain collaboration for the circular economy. Production Planning and Control. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2025.2484556

Uzzi, B. (2020). Social Structure and Competition in Interfirm Networks: The Paradox of Embeddedness. In The Sociology of Economic Life (pp. 213–241). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429494338-13

Wang, B., Osman, L. H., Palil, M. R., & Jamaludin, N. A. B. (2024). QUANTIFYING THE IMPACT OF SOCIAL AND POLITICAL INSTABILITY ON SUPPLY CHAIN OPERATIONS: A RISK ASSESSMENT FRAMEWORK. Operational Research in Engineering Sciences: Theory and Applications, 7(1), 109–130. https://doi.org/10.31181/oresta/070106

Wangchuk, J., Banihashemi, S., Abbasianjahromi, H., & Antwi-Afari, M. F. (2024). Building Information Modelling in Hydropower Infrastructures: Design, Engineering and Management Perspectives. Infrastructures, 9(7), 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures9070098

Weingast, B. R. (2009). Second generation fiscal federalism: The implications of fiscal incentives. Journal of urban economics, 65(3), 279-293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2008.12.005

Williams, T., Vo, H., Samset, K., & Edkins, A. (2019). The front-end of projects: a systematic literature review and structuring. Production Planning and Control, 30(14), 1137–1169. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2019.1594429