Construction Economics and Building

Vol. 25, No. 3/4

December 2025

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Enhancing Flood Risk Governance in Australia: Challenges, Opportunities, and International Insights

Bao T. H. Nguyen1,*, Peter S. P. Wong2, Alireza Ahankoob3

1 School of Property, Construction and Project Management, RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia

2 School of Property, Construction and Project Management, RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia

3 School of Property, Construction and Project Management, RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia

Corresponding author: Bao T. H. Nguyen, tan.hoang.bao.nguyen@gmail.com

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v25i3/4.9663

Article History: Received 10/03/2025; Revised 04/06/2025; Accepted 08/22/2025; Published 05/12/2025

Citation: Nguyen, B. T. H., Wong, P. S. P., Ahankoob, A. 2025. Enhancing Flood Risk Governance in Australia: Challenges, Opportunities, and International Insights. Construction Economics and Building, 25:3/4, 254–271. https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v25i3/4.9663

Abstract

The substantial damage to homes and infrastructure in Australia rekindles the push for improved governance frameworks and adaptive policy measures. Coordinating efforts across federal, state, and local governments has proven challenging due to policy fragmentation, delayed responses, overlapping roles, and disparities in resource allocation. This study examines the strengths and weaknesses of Australia’s flood risk management (FRM) policies through a qualitative document analysis approach, comparing governance structures with international best practices from countries such as Japan, the Netherlands, and the United States. The findings highlight Australia’s strengths in collaborative governance, targeted funding mechanisms, and advanced technical resources such as flood mapping and real-time monitoring systems. However, key weaknesses include governance fragmentation, inconsistent policy implementation, and insufficient support for rural and regional councils. The study proposes a more integrated and adaptive governance framework incorporating cross-jurisdictional coordination, enhanced stakeholder engagement, and sustainable investment strategies. The results contribute to policy discussions on flood risk governance by offering recommendations for strengthening institutional resilience and improving disaster preparedness. By addressing governance inefficiencies and adopting international best practices, Australia can develop a more cohesive and adaptive FRM system to mitigate future flood risks.

Keywords

Flood Risk Governance; Policy Fragmentation; Climate Adaptation; Resilience; Disaster Management

Introduction

Major flood events have caused losses of lives, injuries, and damages to properties, infrastructures, and environments (Ladds et al., 2017; Ulubaşoğlu et al., 2018). Between 2011 and 2022, severe flooding events in Australia resulted in over 160 fatalities and caused economic losses exceeding $30 billion (Coates, 2022; ICA, 2024), with the 2022 Eastern Australia floods alone accounting for 22 fatalities and approximately $4.3 billion in damages (Royal Far West and UNICEF Australia, 2022). These events highlight the need for stronger governance frameworks and coordinated flood policymaking to manage flood risk and mitigate socio-economic impacts (Howes et al., 2015).

Effective flood governance involves multi-level coordination, disaster response frameworks, and stakeholder engagement. In this aspect, governance frameworks for flood risk management (FRM) can take various forms, each with different levels of stakeholder involvement and responsibilities. Some frameworks, like centralised government-led models, ensure strong leadership but may lack local adaptability, while decentralised community-based approaches empower local actors but require resource support. Others, such as collaborative partnerships, watershed-based management, and risk-based decision-making, integrate multiple stakeholders and scientific assessments to enhance resilience. Table 1 presents various forms of governance frameworks being used for FRM globally.

| Governance framework type | Key features | Examples | Relevance to flood risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Centralised government-led | A single government agency takes primary responsibility for planning, mitigation, and response activities. | China’s flood management system (Xu et al., 2018) | This approach ensures strong leadership and efficient resource allocation but may lack local knowledge and community engagement (Moynihan, 2009). |

| Decentralised community-based | Government agencies support local communities and play a significant role in managing flood risks. | Community flood response in Indonesia (Sijbesma and Verhagen, 2008) | This approach increases community ownership and allows for tailored solutions but may require strong capacity building within communities (Stark and Taylor, 2014). |

| Collaborative partnerships | Involves government agencies, businesses, NGOs, and communities working together to develop strategies. | Netherlands’ integrated flood risk governance (Van Popering-Verkerk and Van Buuren, 2017) | This approach brings diverse perspectives and shared responsibilities but can face complex coordination challenges (Foran et al., 2019). |

| Watershed-based management | Focuses on managing flood risk across an entire watershed, considering upstream and downstream impacts. | Japan’s river basin strategy (Fan and Huang, 2023) | This approach offers an integrated approach to water management but requires cooperation across jurisdictions (Kagaya and Wada, 2021). |

| Risk-based decision-making | Prioritises actions based on the level of risk posed to people, property, and infrastructure. | U.K. Environment Agency’s risk framework (Dale et al., 2014) | This approach ensures efficient resource allocation but requires robust risk assessment methodologies (Maskrey et al., 2022). |

Globally, countries usually consider their affordability and geographical vulnerabilities when deciding on FRM approaches. High-income countries, such as Japan, the United States, and most countries in Europe, focus on advanced flood infrastructure, legal frameworks, and multi-agency coordination (Ishiwatari and Hirai, 2024; Van der Keur et al., 2017). For example, Japan’s comprehensive river basin management strategy and the United States’ National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) showcase the importance of cohesive planning and community participation (Brown, 2016; Ishiwatari, 2024). Middle-income countries like Indonesia focus on stakeholder engagement and community-based disaster risk reduction. For example, Indonesia’s community-led initiatives have successfully enhanced flood resilience despite budget constraints (Sunarharum et al., 2020). In contrast, low-income countries like Cambodia emphasise early warning systems and disaster preparedness, supported by international aid (Plate, 2007).

In comparison, Australia adopts an FRM approach that stresses coordinated efforts by the federal, state, and local governments. The federal government offers disaster relief funding and establishes overarching policy guidelines (GA, 2020a). State governments implement FRM policies and coordinate mitigation strategies (NSW Government, 2022), while local councils handle on-the-ground disaster responses, such as flood mapping, land-use planning, and community engagement (Queensland Government, 2021). Key frameworks include the National Disaster Risk Reduction Framework and state-level flood mitigation plans (AIDR, 2017). However, reports highlight challenges in achieving a cohesive approach due to jurisdictional overlaps, data fragmentation, inadequate planning, unequal resource allocation across regions, and disengagement with the community (Parliament of Australia, 2024).

Research problem and objectives

Policy fragmentation and inter-agency coordination gaps remain detrimental to effective FRM (Lawrence et al., 2015; Lietaer et al., 2024). Moreover, disparities in resource allocation and differing policy priorities across jurisdictions exacerbate these challenges (AIDR, 2017; Chow et al., 2023; GA, 2020a). Begg (2018) highlights that local stakeholders seldom receive the necessary support and resources to effectively carry out flood reporting, prevention, and mitigation responsibilities. Cook et al. (2025) argue that participatory frameworks can transform disaster risk governance by fostering institutional change and empowering communities to take ownership of flood preparedness and response efforts. While prior studies have highlighted various gaps in flood governance in Australia, there has been a lack of holistic reviews, particularly regarding how Australia has learned from recent flood disasters and other countries’ experiences.

This study addresses the governance issues through the following objectives:

1. Analyse Australia’s current FRM frameworks.

2. Identify governance strengths and weaknesses within Australian institutional processes.

3. Compare Australia’s flood risk governance to international best practices, including frameworks from countries such as Japan, the United States, and Indonesia, which have implemented adaptive governance approaches in flood resilience.

This study focuses on governance frameworks at Australia’s national, state, and local council levels. This research contributes to understanding how governance frameworks may shape flood resilience efforts by examining policy-making processes and inter-agency collaborations. Additionally, comparing Australia’s governance structures to global practices highlights areas for policy improvement.

Research methods

This study adopts a qualitative document analysis approach to examine governance and policy processes related to FRM in Australia. Document analysis is a systematic procedure for reviewing and evaluating documents, making it suitable for research exploring governance-related frameworks where primary data collection may be limited or impractical (Bowen, 2009). This method identifies governance structures, processes, and outcomes by extracting and coding relevant text, facilitating an in-depth exploration of institutional decision-making processes (Kapucu et al., 2023).

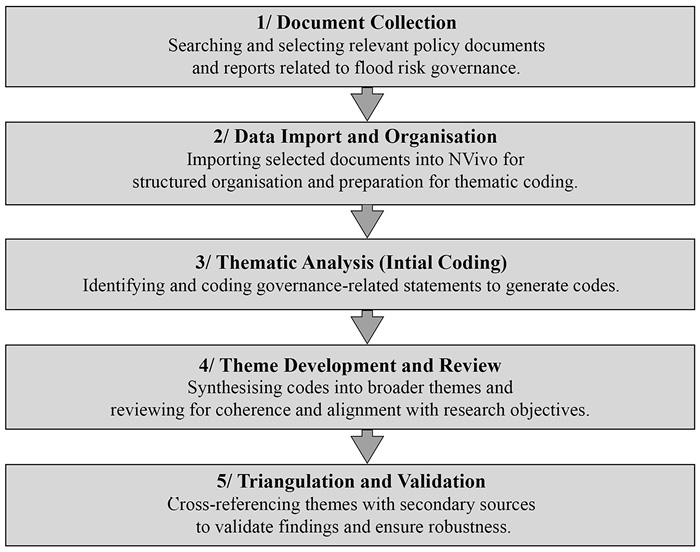

The analysis is informed by a governance framework that focuses on key dimensions such as coordination, resource allocation, stakeholder engagement, and decision-making processes (Biswas et al., 2019; Braganza and Lambert, 2000). This framework provides a lens to assess institutional strengths and weaknesses within multi-level governance systems. By comparing Australian governance approaches to international best practices, this research aims to generate insights into governance gaps and opportunities for policy improvement. Figure 1 illustrates the step-by-step workflow for the document analysis methodology, from data collection to triangulation and validation of findings.

Figure 1. Methodology workflow for governance and policy document analysis

The study relies on a comprehensive set of secondary data sources to capture governance structures and policy approaches related to FRM. Secondary data sources, such as government reports and policy documents, are commonly used in governance research due to their credibility and detailed documentation of institutional processes (Cumiskey, 2020; Ika et al., 2024; Kang, 2022).

Key data sources include the following:

• Government reports: Documents such as the Australian Disaster Resilience Index and state-level flood mitigation plans provide insights into current policy frameworks and resilience efforts.

• Policy documents: FRM strategies, inter-agency agreements, and emergency response guidelines outline the roles and responsibilities of various governance actors.

• International reports: Publications from organisations like the European Commission and case studies from regions like Japan, the Netherlands, and Indonesia offer comparative insights into effective flood risk governance.

These documents were selected because of the need to understand policy content and implementation processes. Recent reports and policy updates were prioritised to ensure that the data reflect current governance practices and emerging challenges. A structured search strategy was applied using Google Scholar, ProQuest, and Australian government repositories, with search terms including “flood governance Australia”, “adaptive policy frameworks flood risk”, “floodplain management plans”, and “state-level flood mitigation strategies”. After evaluation, a total of 26 Australian documents were identified, covering all seven Australian states and territories, ensuring national representation. These included state-level flood policies, disaster response frameworks, and inter-agency coordination reports. Furthermore, to enhance the study’s comparative component, an additional 10 international reports were identified from the Netherlands, Japan, the United States, England, China, Vietnam, and Indonesia—countries recognised for their flood governance frameworks. These were selected using the same search strategy but tailored to international flood risk management approaches. All 36 documents (26 Australian + 10 international) were imported into NVivo for thematic analysis, ensuring a consistent and structured qualitative assessment.

A qualitative thematic analysis approach was employed to analyse the above governance-related documents, following the six-phase framework proposed by Braun and Clarke (2006). The process began with familiarisation, where documents were thoroughly read to understand their content and context. Next, initial codes were generated by identifying key statements related to governance processes such as coordination, funding, and stakeholder engagement. These codes were then organised into broader themes during the theme search phase, reflecting patterns such as “resource and capacity limitations” and “community engagement strategies”. The themes were reviewed and refined to ensure coherence with the data, followed by defining and naming the themes to capture their scope and significance. The final phase involved synthesising the findings into a structured narrative that aligns with the research objectives.

Given the nature of this study, an interpretation-focused coding strategy was deemed most suitable. This approach involves interpreting the underlying meaning of governance-related statements and identifying implicit assumptions or challenges. It is particularly effective for uncovering hidden dynamics, such as policy inconsistencies or power imbalances, critical for understanding governance strengths and weaknesses.

As aforementioned, to ensure the robustness of the findings, triangulation was conducted by cross-referencing themes with secondary sources, including peer-reviewed articles and international reports. This reinforced the validity of the analysis and ensured that the themes were grounded in existing research.

Results

Flood risk management framework in Australia

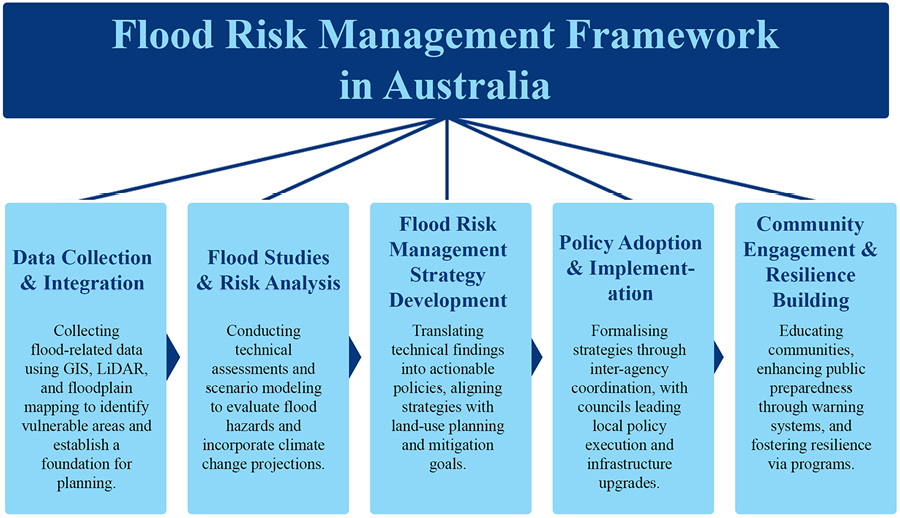

Several reports (NSW Government, 2022; Parliament of Australia, 2024; Queensland Government, 2021; South Australia Government, 2024; GA, 2020a) reveal that Australia’s FRM matches the key features of the decentralised community-based model. It can be presented as a five-stage framework emphasising the articulation of the responsibilities shared among the federal, state, and local governments and communities (refer to Figure 2).

Figure 2. Stages of the flood risk management framework in Australia

Stage 1. Data collection and integration: Accurate data collection underpins Australia’s flood risk governance. Advanced technologies such as Geographic Information Systems (GIS), Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR), and floodplain mapping are employed to identify vulnerable areas and prioritise interventions (South Australia Government, 2023; Victoria Government, 2016a). These tools ensure that stakeholders, including planners and emergency responders, have access to comprehensive flood risk information.

Stage 2. Flood studies and risk analysis: Building on data collection, detailed flood studies are conducted to evaluate hazards. Scenario-based modelling is integral to these analyses, incorporating climate change projections such as intensified rainfall and rising sea levels (Queensland Government, 2017; Victoria Government, 2016b). This stage provides a technical foundation for planning and decision-making.

Stage 3. Flood risk management strategy development: Strategies are developed to translate technical findings into actionable policies. For example, Victoria’s Floodplain Management Strategy aligns land-use planning with mitigation goals, ensuring a “do no harm” approach to infrastructure development in flood-prone areas (Victoria Government, 2019). Similarly, Western Australia uses statutory planning instruments to protect natural floodplain functions (Western Australia Government, 2006).

Stage 4. Policy adoption and implementation: Once strategies are formalised, they are adopted and implemented by local councils and agencies. This stage emphasises stakeholder coordination to ensure effective risk management plan application. Examples include the Brown Hill and Keswick Creek flood plan in South Australia, which highlights multi-agency collaboration (LCA of SA, 2018).

Stage 5. Community engagement and resilience building: Community participation is essential in ensuring the sustainability and acceptance of flood risk policies. Initiatives such as the Total Flood Warning System (TFWS) in Victoria enhance preparedness by providing tailored warnings and public education campaigns (Victoria Government, 2016b). Furthermore, programs like the Resilient Homes Fund in New South Wales strengthen local resilience through infrastructure updates and community involvement (Parliament of Australia, 2024). This five-stage framework, illustrated in Figure 2, highlights the interconnected processes of governance, technical assessment, and community engagement in managing flood risks in Australia.

However, results from the thematic analysis also suggest that the success of the above FRM stages depends heavily on the governance structures that underpin them. Governance strengths and weaknesses have been identified, focusing on collaborative mechanisms, technical resources, legislative support, and community engagement, as well as challenges in resource allocation, policy fragmentation, and land-use conflicts.

Governance strengths and weaknesses of Australia’s FRM framework

Strengths

1. Collaborative governance and coordination: Australia excels in fostering collaboration across all levels of government. Mechanisms like the National Flood Risk Advisory Group (NFRAG) and Flood Warning Consultative Committees ensure consistency in policies and resource sharing (COAG, 2018; GA, 2020a). Regional platforms like the Hazards Services Forum further promote unified planning and data sharing (Corangamite CMA, 2022). Cross-agency efforts, such as the Queensland Reconstruction Authority’s resilience projects, reinforce this coordination (Queensland Government, 2017).

2. Targeted funding and legislative support: Programs like the Disaster Ready Fund and the NSW Floodplain Management Program provide vital financial support for resilience projects (NSW Government, 2022; Parliament of Australia, 2024). Legal frameworks, such as the Land Use Planning and Approvals Act (LUPAA) in Tasmania, embed flood risk mitigation into development planning (LGAT and DEP, 2021).

3. Advanced data and technical resources: Advanced platforms like the National Flood Information Database (NFID) and FloodZoom enable precise flood mapping and real-time monitoring (GA, 2020a; Western Australia Government, 2024). Agencies like the Bureau of Meteorology and Geoscience Australia enhance governance capacity through scenario-based modelling and LiDAR data (Victoria Government, 2016b).

4. Community engagement and awareness: Programs such as Brisbane’s Flood Resilient Homes and the Get Ready Queensland initiative empower communities with education and tailored resources (Queensland Government, 2021). Transparent platforms like TasALERT provide real-time updates, enhancing public preparedness and trust (Tasmanian Government, 2016).

5. Integration of climate adaptation into governance: Flexible policies, such as scenario-based planning in Western Australia and Victoria’s flood-resilient building standards, integrate climate adaptation into governance (Victoria Government, 2019; Western Australia Government, 2024). Partnerships with research organisations further support informed decision-making (Tasmanian Government, 2013).

Weaknesses

1. Resource and capacity constraints: Resource disparities significantly affect FRM, especially in rural and regional councils. Limited budgets and technical expertise hinder essential activities such as flood mapping and adopting advanced technologies like LiDAR (Corangamite CMA, 2022; Wainwright and Verdon-Kidd, 2016). Smaller councils often rely on state or federal assistance, creating inequities in resilience across regions (GA, 2020a).

2. Policy fragmentation: Australia’s decentralised governance results in inconsistencies in flood mapping, hazard standards, and planning laws across states (NSW Government, 2022). Coordination challenges, particularly in cross-border floodplain areas, delay effective management strategies, while the absence of unified national legislation exacerbates fragmentation (GA, 2020a; Victoria Government, 2016a).

3. Information and communication gaps: Inconsistent data collection and sharing practices, along with unclear communication of risks like “1-in-100-year floods”, reduce public trust and preparedness (Victoria Government, 2016b; Wainwright and Verdon-Kidd, 2016). Communities remain unaware of updated flood maps and mitigation strategies, highlighting the need for targeted awareness campaigns (South Australia Government, 2024).

4. Land-use conflicts: Economic pressures and urban development often conflict with flood resilience goals. Legacy planning decisions have allowed developments in flood-prone areas, increasing vulnerabilities (Queensland Government, 2021). Public resistance to stricter land-use controls further complicates long-term mitigation efforts (Western Australia Government, 2024).

Comparison of Australia’s flood risk governance to international practices

In comparison, countries like the Netherlands, Japan, the United States, Indonesia, and Vietnam demonstrate strengths in governance, technology, and planning while revealing common challenges.

Integrated governance and collaboration across stakeholders are key strengths in international systems. The Netherlands’ Delta Programme aligns national, provincial, and private stakeholders through Adaptive Delta Management, fostering long-term resilience (MIWM, 2022). Similarly, Japan’s Basin Water Cycle Plans and Indonesia’s decentralised governance systems empower local authorities and communities to address region-specific flood risks (Clegg et al., 2020; JICA, 2022). These collaborative frameworks demonstrate the importance of coordination in achieving effective flood management.

Robust legal and financial mechanisms further enhance resilience. The Delta Fund in the Netherlands guarantees sustained investments, while Japan’s Basic Act on the Water Cycle embeds sustainable water management into law (JICA, 2022; MIWM, 2022). In the United States, FEMA’s Flood Mitigation Assistance program provides grants for reducing risks, and Vietnam’s hydraulic infrastructure improvements integrate flood control with socio-economic development (CRS, 2024; Garschagen, 2015).

Technological innovation also supports flood resilience. The Netherlands employs smart water management and sediment-based dikes, while Japan integrates multi-purpose dams with hydropower and irrigation (JICA, 2022; MIWM, 2022). In the United States, Flood Insurance Rate Maps guide floodplain standards and reduce financial losses (CRS, 2024).

However, these international systems face limitations. Fragmented governance often slows progress, as seen in Japan’s administrative divisions and coordination gaps in Indonesia and England (Clegg et al., 2020; JICA, 2022). Over-reliance on structural defences like dikes limits adaptability, with Vietnam and the Netherlands focusing heavily on maintenance rather than proactive social resilience (Garschagen, 2015; MIWM, 2022). Public awareness is another challenge, with inconsistent communication strategies reducing preparedness in the Netherlands, Vietnam, and Indonesia (Hung et al., 2010; Kaufmann et al., 2016).

These international cases provide valuable lessons, emphasising the importance of collaboration, innovation, and adaptive governance. Australia can draw from these examples to strengthen its FRM frameworks while addressing governance fragmentation and over-reliance on structural measures.

Implications of the findings

The above comparison reveals that Australia’s FRM system demonstrates notable strengths in areas of localised collaboration, targeted funding, advanced technical resources, and community engagement:

1. Collaborative governance and coordination: Australia excels in fostering collaboration through mechanisms like the National Flood Risk Advisory Group (NFRAG) and Flood Warning Consultative Committees (FWCCs), which streamline coordination among federal, state, and local governments. These platforms ensure consistent disaster response strategies, as exemplified by Queensland’s Reconstruction Authority (QRA), which leads multi-agency initiatives to manage flood resilience (Queensland Government, 2017). Such efforts reflect Australia’s strong localised governance model for specific flood risk scenarios.

2. Targeted funding and legislative support: Australia’s financial and legislative frameworks prioritise resilience. The Disaster Ready Fund commits $1 billion over 5 years to support proactive mitigation measures (Parliament of Australia, 2024). State-level initiatives like the NSW Floodplain Management Program reinforce resilience by integrating hazard planning into development processes (NSW Government, 2022). These mechanisms, which are effectively applied at localised levels, contrast with international struggles to maintain consistent funding or enforce legislation (MIWM, 2022).

3. Advanced data and technical resources: The NFID and tools like FloodZoom enhance real-time risk mapping, enabling evidence-based decision-making (GA, 2020a; Western Australia Government, 2024). These innovations mitigate global challenges related to data fragmentation and outdated modelling techniques, as seen in some international systems (South Australia Government, 2023).

However, governance and policy coherence gaps hinder Australia’s ability to deliver consistent and scalable FRM strategies.

1. Governance and policy fragmentation

Australia’s decentralised governance model creates inconsistencies in flood management across jurisdictions. The lack of unified national legislation leads to varying hazard standards and uneven application of mitigation measures (Victoria Government, 2019; Wainwright and Verdon-Kidd, 2016). For example, flood mapping and zoning standards differ by state, complicating cross-border coordination and reducing overall policy coherence. In contrast, the Netherlands’ Adaptive Delta Management aligns governance across national, provincial, and local levels, demonstrating the effectiveness of an integrated approach (MIWM, 2022).

2. Resource and capacity disparities

Rural and regional councils often lack the financial and technical capacity to adopt advanced flood mitigation measures, relying heavily on inconsistent funding from state and federal levels (McGregor et al., 2022; GA, 2020a). Addressing this disparity requires dedicated funding mechanisms, similar to the Netherlands’ Delta Fund, which ensures consistent investment in adaptive strategies (MIWM, 2022).

3. Information and communication gaps

Australia’s inconsistent data practices hinder decision-making and public engagement. Outdated flood maps and complex terminology alienate communities, reducing trust and preparedness (South Australia Government, 2024). By contrast, the UK integrates transparent flood risk maps into its governance frameworks, improving public understanding and trust (GA, 2020b). Therefore, a centralised data repository and simplified communication strategies could significantly enhance Australia’s resilience.

Towards developing a new FRM framework suitable for Australia

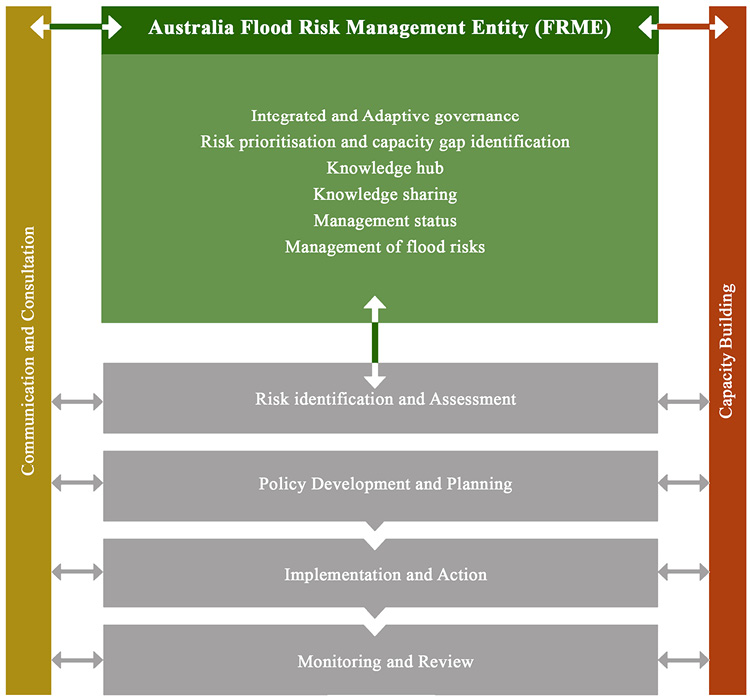

Findings from the review indicate that FRM in Australia can be significantly enhanced by leveraging existing strengths while addressing critical weaknesses identified in current practices. A new FRM framework that can prompt more proactive and inclusive actions while maintaining reliance on evolving risks is needed. Figure 3 illustrates the elements of the proposed framework for Australia.

Figure 3. Proposed adaptive FRM framework for Australia

The proposed framework emphasises collaboration, inclusivity, and sustainability, positioning Australia as a leader in global flood risk management practices.

At the core of this framework is establishing a centralised coordinating body, the Flood Risk Management Entity (FRME). This body would oversee sustainable governance arrangements, serve as a knowledge hub for FRM practices, and manage risk prioritisation and forward planning. Inspired by the Netherlands’ Delta Programme, which emphasises cross-regional alignment and sustainable investments (MIWM, 2022), the FRME would standardise policies and integrate national, state, and local efforts to ensure coherence across jurisdictions. It is recommended that the proposed FRME to be established through intergovernmental agreements in a model legislation framework taken up by different states to address national consistency. The reason is that Australia’s constitutional framework is very different from unitary systems like the Netherlands or the UK. Residual powers rest with the states, so a national entity cannot be unilaterally imposed by the Commonwealth government (PEO and AGS, 2023). Taking account of these limitations, the proposed FRME is not presented as a statutory authority pre-empting state power, but rather as a nationally coordinated, state-led arrangement aimed at harmonising standards, enhancing data sharing, and enabling cross-jurisdictional collaboration.

The framework’s first phase, 1) risk identification and assessment, relies on enhanced data collection and advanced modelling techniques. Australia can strengthen its data-driven decision-making processes by utilising real-time monitoring and predictive analytics (CSIRO, 2008). This phase would include socio-economic impact analyses to prioritise vulnerable communities and inform policy planning. The second phase, 2) policy development and planning, aims to address gaps in governance and standardisation. A unified FRM Act modelled after the Netherlands’ Adaptive Delta Management strategy and England’s Flood and Water Management Act (MIWM, 2022; GA, 2020b), would establish a clear regulatory framework. Inspired by Japan’s Basin Water Cycle Plans, participatory governance mechanisms would ensure that diverse stakeholders, including communities, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), and private sectors, are involved in decision-making processes (JICA, 2022). 3) Implementation and action form the third phase of the framework. Hybrid flood defences, such as combining levees with restored floodplains, could draw from Vietnam’s coastal management practices, which balance structural and non-structural approaches (Hung et al., 2010). Like the Netherlands’ Delta Fund, establishing a resilience fund would ensure consistent, long-term investments in FRM (Kaufmann et al., 2016). Property-level protection programs, inspired by England’s resilience grants, could also be scaled to address localised risks (GA, 2020b). The final phase, 4) monitoring and review, would incorporate adaptive governance principles to evaluate FRM measures’ effectiveness continuously. Lessons from Indonesia’s Integrated Water Resource Management approach highlight the importance of cyclical assessments and flexible policy updates to adapt to evolving risks (Clegg et al., 2020). These evaluations would ensure that the framework remains relevant and effective in mitigating flood impacts.

Cross-cutting processes, including communication and consultation, are integral to the framework. Continuous public education campaigns, similar to Japan’s awareness initiatives (JICA, 2022), and capacity-building programs for under-resourced councils are essential to enhance community preparedness and local governance capabilities (GA, 2020b).

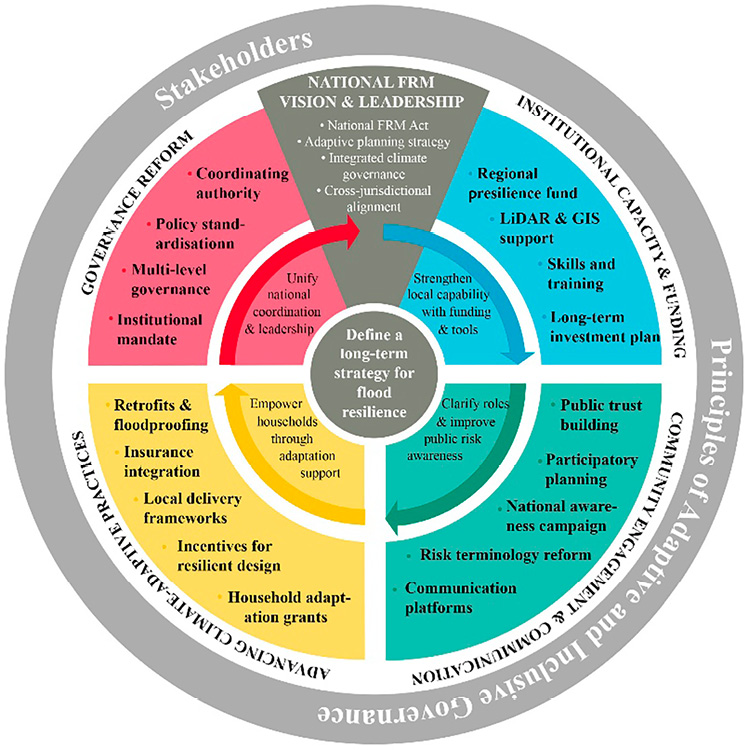

Actionable recommendations for enhancing flood risk governance in Australia

Drawing from the comparative analysis and the proposed adaptive FRM framework, this section presents a set of interrelated, actionable policy recommendations to address the identified governance challenges. These recommendations are organised into four thematic domains to reflect the systemic and interconnected nature of flood governance reform in Australia. Together, they form the basis of a governance wheel model (Figure 4, adapted from Co-operatives UK (2020)), indicating how each domain contributes to a cohesive and adaptive flood risk management system.

1. Governance reform

To overcome jurisdictional fragmentation, a national coordinating mechanism, such as an FRME, should be established through intergovernmental consent and harmonised state legislation. Owing to Australia’s federal constitution, this organisation would have to function with the collaboration of state governments and in a manner that provides national consistency. It would oversee coordination among federal, state, and local governments, ensure legislative consistency, and standardise flood risk planning across Australia.

2. Institutional capacity and funding

A dedicated resilience fund should be created to support local councils, particularly those in rural and regional areas, that currently face technical and resource constraints. This fund would ensure access to critical tools such as LiDAR, GIS, and flood modelling software, and enable investment in workforce training, local infrastructure, and hazard mapping initiatives. This approach mirrors long-term investment strategies seen in international cases such as the Netherlands’ Delta Fund.

3. Community engagement and communication

Improving public understanding and community participation is essential. A national flood risk communication strategy should be developed to clarify complex concepts (e.g., replacing “1-in-100-year flood” terminology) and enhance risk awareness. This should be supported by locally led education campaigns, participatory planning workshops, and capacity-building programs that empower communities to engage meaningfully in FRM decisions.

4. Advancing climate-adaptive building practices

Figure 4. Governance wheel for enhancing flood risk governance in Australia.

Source: Adapted from Co-operatives UK (2020)

To complement structural mitigation, scalable grants need to be introduced to support both household- and business-level resilience interventions. These may include incentives for elevating homes, installing waterproof materials, or retrofitting structures in high-risk areas. Delivered through existing platforms like the Disaster Ready Fund, this program is believed to target high-exposure zones and promote climate-adaptive building practices.

Concluding remarks

This study has provided critical insights into the governance challenges and opportunities in Australia’s FRM. The findings highlight persistent issues such as policy fragmentation, coordination gaps among federal, state, and local governments, and resource disparities, particularly in rural and regional areas. These challenges continue to hinder the efficiency of flood resilience efforts. At the same time, Australia demonstrates notable strengths, including collaborative mechanisms like the NFRAG, targeted funding programs like the Disaster Ready Fund, and advanced technical tools, including GIS and LiDAR-based flood mapping, which have significantly enhanced data collection and decision-making processes. The comparative analysis of international cases, including the Netherlands’ Adaptive Delta Management and Japan’s Basin Water Cycle Plans, underscores the potential for integrating adaptive and participatory governance approaches into Australian flood policy. Notably, the suggestion of a central coordinating body is nuanced to recognise Australia’s federal arrangement: such a body would necessitate interstate consensus and cooperative governance structures, rather than a statutory authority imposed unilaterally at the Commonwealth level. This keeps the proposal constitutionally viable while still remedying fragmentation and strengthening national consistency.

This research contributes to policy and theoretical discussions by identifying enablers and barriers that influence the effectiveness of Australia’s flood governance. From a policy perspective, it offers actionable recommendations, such as establishing a central coordinating entity to standardise flood risk policies and enhance cross-jurisdictional collaboration, addressing governance fragmentation, and developing unified national legislation. These reforms could ensure greater policy implementation and resource distribution coherence, particularly in under-resourced rural areas. Furthermore, increasing investment in capacity-building programs and technical tools could address disparities and empower local governments to adopt advanced flood mitigation measures. The findings also advance theoretical understanding by illustrating how collaborative and participatory approaches can mitigate policy fragmentation and enhance institutional resilience when integrated with adaptive governance frameworks. Comparative insights reveal that governance frameworks are not universally transferable but must be adapted to socio-economic and environmental contexts.

This study has some limitations. It relied on secondary data, which constrain the ability to capture real-time governance dynamics and stakeholder interactions during flood events. Additionally, the geographic scope of the analysis focuses solely on Australia, leaving room for broader cross-regional comparisons. Future research could address these gaps by conducting real-time evaluations of governance performance during flood events, providing a deeper understanding of dynamic policy responses and interactions. Expanding the scope to include regions such as South America or Africa would also enable a more comprehensive analysis of how governance frameworks can be adapted to different socio-economic and climatic conditions. Exploring the potential of digital technologies, such as artificial intelligence (AI)-driven flood monitoring and decision-making tools, could further enhance governance capacities and flood resilience (Zabihi et al., 2023). These areas of future research would not only complement the findings of this study but also contribute to global discussions on adaptive flood risk governance and its practical implementation.

References

Australian Institute for Disaster Resilience (AIDR). (2017). Managing the Floodplain: A Guide to Best Practice in Flood Risk Management in Australia (Australian Disaster Resilience Handbook Collection (2011 – ), Issue. https://knowledge.aidr.org.au/media/3521/adr-handbook-7.pdf

Begg, C. (2018). Power, responsibility and justice: a review of local stakeholder participation in European flood risk management. Local Environment 23(4), 383-397. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2017.1422119

Biswas, R., Jana, A., Arya, K., & Ramamritham, K. (2019). A good-governance framework for urban management. Journal of Urban Management, 8(2), 225-236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jum.2018.12.009

Bowen, G. A. (2009). Document Analysis as a Qualitative Research Method. Qualitative Research Journal, 9(2), 27-40. https://doi.org/10.3316/QRJ0902027

Braganza, A., & Lambert, R. (2000). Strategic Integration: Developing aProcess±Governance Framework. Knowledge and Process Management, 7(3), 177-186. https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-1441(200007/09)7:3<177::AID-KPM104>3.0.CO;2-U

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3(2), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brown, J. T. (2016). Introduction to FEMA’s National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP). https://biotech.law.lsu.edu/blog/Introduction-to-FEMAs-National-Flood-Insurance-Program-_-CRS-_-August-2016.pdf

Chow, E., Barnes, D., Blunden, J., Davidson, J., Pang, E., James, W. T. a., & Manton-Hall. (2023). Funding for Flood Costs: Affordability, Availability and Public Policy Options https://www.actuaries.asn.au/docs/thought-leadership-reports/funding-costs-for-floods.pdf

Clegg, G., Haigh, R., Amaratunga, D., & Rahayu, H. (2020). River Governance and Flood Management Arrangements in Indonesia (Mitigating hydro-meteorological hazard impacts through improved transboundary river management in the Ciliwung River Basin, Issue. https://gdrc.buildresilience.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/IndonesiaStudyReport.pdf

Co-operatives UK. (2020). What is good governance? https://www.uk.coop/support-your-co-op/governance/what-good-governance

Coates, L. (2022). A flood of rain events: how does it stack up with the previous decade? (Briefing Note 465, Issue. https://riskfrontiers.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/465-Briefing-Note.pdf

Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO). (2008). Water Availability in the Murray–Darling Basin (A report to the Australian Government by the CSIRO Murray–Darling Basin Sustainable Yields Project, Issue.

Congressional Research Service (CRS). (2024). Introduction to the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP). https://sgp.fas.org/crs/homesec/R44593.pdf

Cook, B. R., Cornes, I., Satizábal, P., & Zurita, M. d. L. M. (2025). Experiential learning, practices, and space for change: The institutional preconfiguration of community participation in flood risk reduction. Journal of Flood Risk Management, 18(1), e12861. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfr3.12861

Corangamite Catchment Management Authority (Corangamite CMA). (2022). Floodplain Development Guidelines: Guidelines for Development in Flood Prone Areas. https://ccma.vic.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/CCMA-FLOODPLAIN-DEVELOPMENT-GUIDELINES-2022_S.pdf

Council of Australian Governments (COAG). (2018). Intergovernmental Agreement on the Provision of Bureau of Meteorology Hazard Services to the States and Territories. https://federation.gov.au/about/agreements/intergovernmental-agreement-provision-bureau-meteorology-hazard-services-states

Cumiskey, L. R. (2020). Joining the dots: a framework for assessing integration in flood risk management with applications to England and Serbia (Publication Number M00611055) Middlesex University London].

Dale, M., Wicks, J., Mylne, K., Pappenberger, F., Laeger, S., & Taylor, S. (2014). Probabilistic flood forecasting and decision-making: an innovative risk-based approach. Natural Hazards, 70, 159-172. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-012-0483-z

Fan, J., & Huang, G. (2023). Flood risk management in Japan in response to climate change: shift from river channel-focused control to watershed-oriented management. Emergency Management Science and Technology, 3(23). https://doi.org/10.48130/EMST-2023-0023

Foran, T., Penton, D. J., Ketelsen, T., Barbour, E. J., Grigg, N., Shrestha, M., Lebel, L., Ojha, H., Almeida, A., & Lazarow, N. (2019). Planning in Democratizing River Basins: The Case for a Co-Productive Model of Decision Making. Water 11(12), 2480. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11122480

Garschagen, M. (2015). Risky Change? Vietnam’s Urban Flood Risk Governance between Climate Dynamics and Transformation. Pacific Affairs, 88(3), 599-621. https://doi.org/10.5509/2015883599

Howes, M., Tangney, P., Reis, K., Grant-Smith, D., Heazle, M., Bosomworth, K., & Burton, P. (2015). Towards networked governance: improving interagency communication and collaboration for disaster risk management and climate change adaptation in Australia. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 58(5), 757-776. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2014.891974

Hung, H. V., Shaw, R., & Kobayashi, M. (2010). Flood risk management for the riverside urban areas of Hanoi: The need for synergy in urban development and risk management policies. Disaster Prevention and Management, 19(1), 103-118. https://doi.org/10.1108/09653561011022171

Ika, L., Meredith, J., & Zwikael, O. (2024). Project governance: the impact of environmental changes on governance adaptations in large-scale projects. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, 17(4/5), 829-854. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMPB-03-2024-0056

Insurance Council of Australia (ICA). (2024). ICA Historical Catastrophe List (https://insurancecouncil.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/ICA-Historical-Normalised-Catastrophe-June-2024.xlsx

Ishiwatari, M. (2024). Strategic governance - the challenges of integrated flood risk management. In J. Lamond, D. Proverbs, & N. B. Mis (Eds.), Research Handbook on Flood Risk Management (pp. 291-303). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781839102981.00030

Ishiwatari, M., & Hirai, H. (2024). Challenges in Promoting All-Hazard Approach in Japan: Institutional Arrangements for Managing Cascading Effects. In T. Izumi, M. Abe, K. Fujita, & R. Shaw (Eds.), All-Hazards Approach: Towards Resilience Building (pp. 191–205). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-97-1860-3_13

Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). (2022). Japan’s Experience on Water Resources Management. https://www.jica.go.jp/english/our_work/thematic_issues/water/fh2q4d000000ruz4-att/theme_01_01.pdf

Kagaya, S., & Wada, T. (2021). The application of environmental governance for sustainable watershed-based management. Asia-Pacific Journal of Regional Science, 5, 643-671. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41685-020-00185-1

Kang, Y. h. (2022). The Political Dimension of Water Management in the Face of Climate Change. In Climate Change Adaptation in River Management (pp. 1-40). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-10486-2_1

Kapucu, N., Dougherty, R. B., Ge, Y., & Zobel, C. (2023). The use of documentary data for network analysis in emergency and crisis management. Natural Hazards, 116, 425-445. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-022-05681-5

Kaufmann, M., van Doorn-Hoekveld, W., Gilissen, H. K., & van Rijswick, M. (2016). Analysing and evaluating flood risk governance in the Netherlands (Strengthening and Redesigning European Flood Risk Practices: Towards Appropriate and Resilient Flood Risk Governance Arrangements, Issue. https://hdl.handle.net/2066/159329

Ladds, M., Keating, A., Handmer, J., & Magee, L. (2017). How much do disasters cost? A comparison of disaster cost estimates in Australia. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 21, 419-429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2017.01.004

Lawrence, J., Sullivan, F., Lash, A., Ide, G., Cameron, C., & McGlinchey, L. (2015). Adapting to changing climate risk by local government in New Zealand: institutional practice barriers and enablers. Local Environment 20(3), 298-320. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2013.839643

Lietaer, S., Nagabhatla, N., Scheerens, C., Mycroft, M., & Lombaerde, P. D. (2024). Blind Spots in Belgian Flood Risk Governance: The Case of the Summer 2021 Floods in Wallonia (UNU-CRIS Research Report, Issue. https://cris.unu.edu/blindspotsinbelgianfloodriskgovernance

Local Government Association of South Australia (LCA of SA). (2018). Review of stormwater management legislation and policy. https://www.lga.sa.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0039/469983/ECM_658270_v20_Review-of-stormwater-management-legislation-and-policy.pdf

Local Government Association of Tasmania (LGAT), & Derwent Estuary Program (DEP). (2021). Tasmanian Stormwater Policy Guidance and Standards for Development. https://tasman.tas.gov.au/download/policies/C-041-Tasmanian-Stormwater-Policy-Guidance-and-Standards-for-Development-2021.pdf

Maskrey, S. A., Mount, N. J., & Thorne, C. R. (2022). Doing flood risk modelling differently: Evaluating the potential for participatory techniques to broaden flood risk management decision-making. Journal of Flood Risk Management, 15(1), e12757. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfr3.12757

McGregor, J., Parsons, M., & Glavac, S. (2022). Local Government Capacity and Land Use Planning for Natural Hazards: A Comparative Evaluation of Australian Local Government Areas. Planning Practice & Research, 37(2), 248-268. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2021.1919431

Minister of Infrastructure and Water Management (MIWM). (2022). National Delta Programme 2023: Speed up, connect and reconstruct. https://english.deltaprogramma.nl/

Moynihan, D. P. (2009). The Network Governance of Crisis Response: Case Studies of Incident Command Systems. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 19(4), 895–915. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mun033

NSW Government. (2022). Flood Risk Management Manual: The management of flood liable land. https://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/-/media/OEH/Corporate-Site/Documents/Water/Floodplains/flood-risk-management-manual-220060.pdf

Parliament of Australia. (2024). Flood failure to future fairness: Report on the inquiry into insurers’ responses to 2022 major floods claims. https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/committees/reportrep/RB000297/toc_pdf/Floodfailuretofuturefairness.pdf

Parliamentary Education Office (PEO), & Australian Government Solicitor (AGS). (2023). Australia’s Constitution: With Overview and Notes by the Australian Government Solicitor. https://ausconstitution.peo.gov.au/index.html

Plate, E. J. (2007). Early warning and flood forecasting for large rivers with the lower Mekong as example. Journal of Hydro-environment Research, 1(2), 80-94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jher.2007.10.002

Queensland Government. (2017). Strategic Policy Framework for Riverine Flood Risk Management and Community Resilience. https://www.qra.qld.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019-02/Strategic%20Policy%20Framework%20for%20Riverine%20Flood%20Risk%20Management%20-%20update%202019.pdf

Queensland Government. (2021). Queensland Flood Risk Management Framework. https://www.qra.qld.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-06/queensland_flood_risk_management_framework_2021_qfrmf_0.pdf

Royal Far West, & UNICEF Australia. (2022). 2022 Flood Response and Recovery: Children’s Needs Assessment. https://www.royalfarwest.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/2022_FloodResponseRecovery_LoRes.pdf

Sijbesma, C., & Verhagen, J. (2008). Making urban sanitation strategies of six Indonesian cities more pro-poor and gender-equitable: the case of ISSDP. https://www.ircwash.org/resources/making-urban-sanitation-strategies-six-indonesian-cities-more-pro-poor-and-gender

South Australia Government. (2023). Flood Hazard Mapping and Assessment Project: Delivering more consistent and contemporary flood hazard mapping to better prepare for and minimise impacts arising from flood risks. https://plan.sa.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/1002368/Flood_hazard_mapping_and_assessment_project_-_Brochure.pdf

South Australia Government. (2024). Flood Hazard Risk Reduction Plan 2024 (Part 3 Supporting Plans, Issue. https://cdn.environment.sa.gov.au/environment/docs/2024-Flood-Hazard-Risk-Reduction-Plan.pdf

Stark, A., & Taylor, M. (2014). Citizen participation, community resilience and crisis-management policy. Australian Journal of Political Science, 49(2), 300-315. https://doi.org/10.1080/10361146.2014.899966

Sunarharum, T. M., Sloan, M., & Susilawati, C. (2020). Collaborative Approach for Community Resilience to Natural Disaster: Perspectives on Flood Risk Management in Jakarta, Indonesia the 12th KES International Conference on Sustainability and Energy in Buildings 2020 (SEB20), Split, Croatia. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-8783-2_23

Tasmanian Government. (2013). Principles for the consideration of Natural Hazards in the Planning System. https://www.dpac.tas.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0021/26841/Principles_for_the_consideration_of_natural_hazards.pdf

Tasmanian Government. (2016). Submission to the Independent Review into the June 2016 Tasmanian Floods. https://www.dpac.tas.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0018/64260/DPAC.pdf

The Geneva Association (GA). (2020a). Flood Risk Management in Australia: Building flood resilience in a changing climate. https://www.genevaassociation.org/sites/default/files/frm_australia_web.pdf

The Geneva Association (GA). (2020b). Flood Risk Management in England: Building flood resilience in a changing climate. https://www.genevaassociation.org/sites/default/files/flood-risk-management-england.pdf

Ulubaşoğlu, M. A., Rahman, M. H., Önder, Y. K., Chen, Y., & Rajabifard, A. (2018). Floods, Bushfires and Sectoral Economic Output inAustralia, 1978–2014. Economic Record, 95(308), 58-80. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-4932.12446

Van der Keur, P., Staugaard, L., Meyer, A. M., Mcinerny, T., Molnár, A., Hausmann, H. J., Berendt, S., Harjanne, A., & Hen-Riksen, H. J. (2017). An Overview of Institutional Structures and Good Practices in Northern Ireland, Hungary and Denmark based on Multi-Agency Workshops in the Three Countries and Supplementary Information from Nordic Countries (Sharing Good Practice and Multi-Agency Partnership Framework: Community Resilience with focus on flooding, Issue.

Van Popering-Verkerk, J., & Van Buuren, A. (2017). Developing collaborative capacity in pilot projects: Lessons from three Dutch flood risk management experiments. Journal of Cleaner Production, 169, 225-233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.04.141

Victoria Government. (2016a). Victorian Flood Data and Mapping Guidelines. https://www.water.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0036/661788/victorian-flood-data-and-mapping-guidelines.pdf

Victoria Government. (2016b). Victorian Floodplain Management Strategy. https://fvtoc.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/201604_Victorian_Floodplain_Management_Strategy.pdf

Victoria Government. (2019). Guidelines for Development in Flood Affected Areas. https://www.water.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0024/662325/guidelines-for-development-in-flood-affected-areas.pdf

Wainwright, D., & Verdon-Kidd, D. (2016). A local government framework for coastal risk assessment in Australia. https://coastadapt.com.au/sites/default/files/factsheets/RR5_Local_government_framework_coastal_risk_Australia.pdf

Western Australia Government. (2006). Western Australian Planning Commission: State Planning Policy No. 3.4. (Natural Hazards and Disasters, Issue. https://www.wa.gov.au/system/files/2021-06/SPP_3-4_natural_hazards_disasters.pdf

Western Australia Government. (2024). A Statewide Coastal Inundation Assessment for WA - Phase 2 Report. https://www.transport.wa.gov.au/mediaFiles/marine/MAC_P_Coastal_Inundation_Assessment_Phase_2_Report.pdf

Xu, J., Wang, Q., Xu, D., & Lu, Y. (2018). Types of community-focused organisations for disaster risk reduction in the Longmen Shan Fault area. Environmental Hazards 17(3), 181-199. https://doi.org/10.1080/17477891.2017.1383879

Zabihi, O., Siamaki, M., Gheibi, M., Akrami, M., & Hajiaghaei-Keshteli, M. (2023). A smart sustainable system for flood damage management with the application of artificial intelligence and multi-criteria decision-making computations. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 84, 103470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2022.103470