Construction Economics and Building

Vol. 25, No. 3/4

December 2025

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Supply Chain Integration in Public Sector Construction Projects: Adoption and Barriers

Amaka Chinweude Ogwueleka

Department of Quantity Surveying, University of Uyo

Corresponding author: Amaka Chinweude, amakaogwueleka@gmail.com

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v25i3/4.9591

Article History: Received 01/02/2025; Revised 18/07/2025; Accepted 03/09/2025; Published 05/12/2025

Citation: Ogwueleka, A. C. 2025. Supply Chain Integration in Public Sector Construction Projects: Adoption and Barriers. Construction Economics and Building, 25:3/4, 272–288. https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v25i3/4.9591

Abstract

Traditional procurement practices in public sector construction often lead to inefficiencies, cost overruns, and delays due to fragmented collaboration. This study investigated supply chain integration (SCI) adoption and barriers in public sector construction projects in Nigeria’s Southern region, specifically Akwa Ibom and Rivers States. Employing a survey research design, 354 questionnaires were distributed to construction professionals, yielding 272 valid responses (76% response rate), and analyzed using mean item score (MIS) and the Kruskal–Wallis H-test. Findings indicate moderate SCI adoption (MIS = 2.53), with information sharing (MIS = 3.48), customer relationships (MIS = 3.46), leadership management (MIS = 3.25), long-term networking (MIS = 3.14), and just-in-time delivery (MIS = 2.80) as top practices. Key barriers included low innovation (MIS = 4.02), late material delivery (MIS = 3.99), lack of top management support (MIS = 3.89), poor stakeholder attitudes (MIS = 3.83), and inadequate resources (MIS = 3.75). Grounded in institutional theory, transaction cost economics, and stakeholder theory, this study provides empirical evidence from a developing context, offering actionable insights for policymakers and practitioners to enhance project efficiency and sustainability through training, logistics improvements, and leadership commitment. Limitations include the regional focus, suggesting future research on digital tools and broader geographic contexts.

Keywords

Supply Chain Integration; Public Sector; Construction Projects; Adoption; Barriers

Introduction

Public sector construction projects are vital for national development, contributing significantly to gross domestic product (GDP) through infrastructure investments, such as roads, bridges, and public facilities (Bent, 2014). However, traditional procurement models often result in inefficiencies, including fraud, corruption, and maladministration, leading to project delays and cost overruns (Nkwanyana and Agbenyegah, 2020). Supply chain integration (SCI) offers a strategic approach to address these challenges by fostering collaboration, optimizing resources, and enhancing project outcomes (Sabry, 2015). Despite its adoption in industries like manufacturing, where integrated supply chains reduce costs by 20%–30% (Yalcin et al., 2020), SCI in public sector construction, particularly in developing countries like Nigeria, remains underexplored. Nigeria’s construction industry, valued at $105 billion in 2023, faces systemic challenges, with projects exceeding budgets by 20%–30% due to fragmented supply chains, outdated procurement policies, and limited transparency (Okafor et al., 2021; KPMG, 2023). For instance, the Lagos–Ibadan Railway project incurred $200 million in additional costs due to supply chain inefficiencies (Aigbavboa et al., 2022). This study examined SCI adoption and barriers in public sector construction projects in Akwa Ibom and Rivers States. Nigeria’s key economic hubs in the oil-rich South-South region are aiming to provide empirical insights and practical strategies for improving efficiency and sustainability.

Procurement is now recognized as a strategic function, akin to marketing and finance, enhancing competitiveness and stakeholder satisfaction (Migiro and Ambe, 2009). SCI integrates processes, such as warehousing, inventory control, transportation, and procurement, to improve cost performance and service delivery (Sanjay and Shamila, 2019). However, challenges like poor implementation, lack of skilled personnel, and inadequate collaborative planning hinder adoption in Nigeria’s public sector (Migiro and Ambe, 2009). Recent reports highlight regulatory constraints, resource scarcity, and limited technological adoption, with only 15% of Nigerian firms using building information modeling (BIM) compared to 60% in developed economies (Mohammadi, 2020; Elghaish et al., 2022). This study was motivated by the need to address these inefficiencies, drawing on institutional theory (DiMaggio and Powell, 1983), transaction cost economics (TCE) (Williamson, 1981), and stakeholder theory (Freeman, 2010) to explore SCI’s potential to enhance project performance. It contributes empirical evidence from a developing context, offering strategies to overcome barriers and align with global sustainability trends, such as reducing construction emissions by 30% by 2030 (UNEP, 2023). The research questions are as follows: (1) What is the level of SCI adoption in public sector construction projects? (2) What are the key barriers inhibiting SCI adoption? (3) How can these barriers be addressed to improve project outcomes?

The significance of this study lies in its focus on Nigeria’s public sector, where infrastructure development accounts for 7% of GDP and is crucial for economic growth (KPMG, 2023). Akwa Ibom and Rivers States, contributing 40% of Nigeria’s oil revenue, are pivotal for projects like the Ibom Deep Seaport and East-West Road yet face persistent delays and cost overruns (Okafor et al., 2021). Unlike studies in developed economies, which emphasize digital tools like BIM (Papadonikolaki et al., 2019), this research addresses a gap in developing contexts, where resource constraints and regulatory fragmentation prevail. It offers practical recommendations for stakeholders—policymakers, contractors, and suppliers—to enhance project delivery and sustainability. By integrating theoretical and empirical perspectives, this study bridged academic discourse and policymaking, fostering efficient and sustainable construction practices in Nigeria, with implications for other African nations facing similar challenges (Ogunnusi et al., 2024).

Literature review

Procurement is now recognized as a strategic function, enhancing competitiveness and stakeholder satisfaction (Migiro and Ambe, 2009). SCI integrates processes like warehousing, inventory control, transportation, and procurement to improve cost performance and service delivery (Sanjay and Shamila, 2019). However, challenges like poor implementation and lack of skilled personnel hinder progress, particularly in resource-constrained contexts like Nigeria, where projects face delays of up to 40% due to fragmented supply chains (KPMG, 2023).

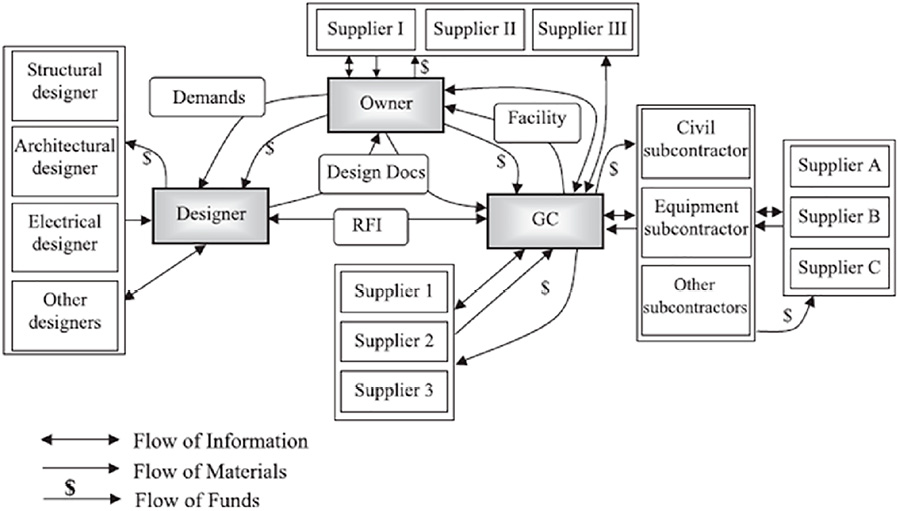

This study extended institutional theory, TCE, and stakeholder theory to a developing context, where regulatory fragmentation, cultural resistance, and resource scarcity shape SCI adoption. Institutional theory explains how Nigeria’s weak enforcement of procurement laws hinders SCI, with only 20% of projects adhering to collaborative standards (Ogunwusi et al., 2024). TCE highlights cost savings through integrated processes, such as just-in-time delivery, reducing inventory costs by 15% (Min and Mentzer, 2004). Stakeholder theory underscores the need for collaborative relationships to overcome barriers like poor communication, which increases project costs by 10%–20% (Christopher and Peck, 2004). This framework guides the empirical analysis, addressing a gap in prior studies focused on developed economies (Yalcin et al., 2020). Figure 1 reveals the model of the construction supply chain as developed by Xue et al. (2005).

Figure 1. Model of the construction supply chain. Source: Xue, et al. (2005)

Level of adoption of supply chain integration

Public sector construction projects require effective stakeholder collaboration due to their complexity, involving multiple actors and processes (Alashwal et al., 2015). SCI enhances coordination, reduces costs, and improves project outcomes by integrating supply chain processes (Sabry, 2015). Recent studies have highlighted SCI’s evolution from internal process optimization to networked collaboration, with digital tools like BIM and blockchain improving efficiency by 20%–30% (Yalcin et al., 2020). For example, Cataldo, et al. (2021) demonstrated SCI’s role in fostering sustainability through lean construction, reducing waste by 20%, and green procurement, aligning with global environmental goals (UNEP, 2023). Post-2018 research has emphasized information technology (IT) as a critical enabler, with BIM reducing errors by 15%–25% in projects like the UK’s Crossrail (Wang et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2023). However, Nigeria’s construction industry lags, with only 15% of firms using BIM compared to 60% in Australia due to limited IT literacy and funding (Osunsanmi et al., 2018; Elghaish et al., 2022). Lean construction optimizes resource use (Kim et al., 2019), while strategic partnerships and risk management enhance performance (Li et al., 2018). Globally, SCI adoption varies significantly. In developed economies like Australia and the UK, SCI is advanced, with digital platforms improving project efficiency by 20%–30% (Papadonikolaki et al., 2019). For instance, Australia’s Sydney Metro used BIM to reduce costs by 15% and timelines by 20% (Zhang et al., 2023). In contrast, developing countries like Nigeria face challenges, including limited technological infrastructure (only 10% of firms have access to high-speed internet) and low IT literacy (20% of professionals trained in digital tools) (Okafor et al., 2021; Ogunnusi et al., 2024). This study hypothesized that there is moderate SCI adoption in Nigeria’s public sector due to these constraints, consistent with the findings of Osunsanmi, et al. (2018). Key SCI practices, such as information sharing, customer relationship management, long-term networking, and just-in-time delivery, are crucial for enhancing efficiency and sustainability (Chen et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2023). In Nigeria, SCI adoption is hindered by systemic issues. Only 25% of public sector projects use integrated procurement systems, compared to 70% in developed economies (Amade et al., 2016). Cultural resistance to change, limited funding (construction budgets cut by 10% in 2023), and inadequate training (only 15% of professionals trained in SCI) exacerbate low adoption rates (KPMG, 2023). Globally, successful SCI adoption in projects like Singapore’s Marina Bay Sands highlights the importance of leadership commitment and IT investment, reducing timelines by 20% (Yitmen, 2019). In Africa, South Africa’s public housing projects demonstrate lean construction’s potential to reduce costs by 15% (De Boer et al., 2016). This study addresses a gap by providing empirical evidence from Nigeria, offering context-specific insights into SCI practices and barriers, and aligning with global sustainability trends.

Digital transformation in construction supply chains

Digital tools like BIM, blockchain, and Internet of Things (IoT) are transforming SCI globally. BIM enables real-time collaboration, reducing design errors by 20% and costs by 10%–15% (Elghaish et al., 2022). Blockchain enhances transparency in procurement, reducing fraud by 25% in pilot projects in Singapore (Hosseini et al., 2023). IoT improves logistics tracking, reducing material delivery delays by 20% in Australian projects (Zhang et al., 2023). In Nigeria, digital adoption is low, with only 10% of firms using BIM and 5% exploring blockchain due to high costs and limited expertise (Ogunnusi et al., 2024). This subsection explores how digital transformation can address Nigeria’s SCI barriers, drawing lessons from global best practices.

Stakeholder dynamics in SCI adoption

Stakeholder dynamics significantly influence SCI adoption. Contractors, suppliers, and clients must align interests to ensure effective collaboration. In Nigeria, poor stakeholder attitudes, driven by mistrust and lack of communication, hinder SCI, with only 20% of projects involving formal supplier partnerships (Aigbavboa et al., 2022). Globally, stakeholder engagement through regular forums and shared platforms enhances SCI adoption by 25% (Papadonikolaki et al., 2019). This subsection examines stakeholder roles in Nigeria’s public sector, proposing strategies to foster trust and collaboration.

Comparative analysis of SCI in Africa

SCI adoption in Africa varies by country. South Africa leads with 40% of projects using integrated supply chains, driven by lean construction and public–private partnerships (PPPs) (De Boer et al., 2016). Ethiopia’s Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) project demonstrates moderate SCI adoption through just-in-time delivery, reducing costs by 15% (Yitmen, 2019). In contrast, Nigeria lags, with only 25% of projects integrated due to regulatory and logistical barriers (Amade et al., 2016). This subsection compares SCI practices across African nations, identifying lessons for Nigeria to enhance adoption and align with continental trends.

Barriers inhibiting SCI adoption

SCI adoption faces challenges like lack of communication, incompatible IT systems, and resistance to change (Fawcett et al., 2008). In Nigeria, these barriers are compounded by context-specific issues such as regulatory fragmentation, resource scarcity, and logistical inefficiencies, which delay 40% of projects and increase costs by 15% (Okafor et al., 2021; KPMG, 2023). Institutional theory suggests that regulatory pressures and organizational inertia exacerbate resistance to SCI adoption (DiMaggio and Powell, 1983), while TCE indicates that barriers like poor communication and lack of strategic alignment increase coordination costs by 10%–15% (Williamson, 1981; Min and Mentzer, 2004). Stakeholder theory highlights the role of poor attitudes and lack of trust among supply chain partners, hindering collaboration and integration (Freeman, 2010). This subsection examines barriers to SCI adoption in Nigeria’s public sector, focusing on technological, logistical, and cultural/organizational challenges, drawing on global and local studies to provide a comprehensive analysis (Amade et al., 2016; Fauzi et al., 2017; Ogunnusi et al., 2024).

Technological barriers

Technological barriers, such as poor data quality and outdated IT systems, lead to errors and inefficiencies, increasing costs by 10%–20% (Wang and Li, 2009). Only 5% of Nigerian firms use BIM, compared to 70% in developed economies, due to high implementation costs (Okafor et al., 2021). Low innovation (MIS = 4.02) and inadequate IT infrastructure limit real-time coordination, affecting 60% of public sector projects (Ogunwusi et al., 2024).

Logistical and cultural barriers

Late material delivery (MIS = 3.99) is due to poor road network delays, affecting 40% of projects (KPMG, 2023). Cultural resistance and lack of top management support (MIS = 3.89) hinder SCI, with only 15% of professionals trained in SCI practices (Amade et al., 2016). Inadequate procurement systems and ignoring subcontractors’ needs further limit integration (Shukor et al., 2011). Addressing these requires leadership training and policy reforms to align with global practices (Papadonikolaki et al., 2019).

Several barriers inhibiting SCI were identified in the literature search, and they are presented in Table 1 and collated for data collection.

| Barriers | Authors |

|---|---|

| Bad work attitude | Arrey (2013) |

| Cultural differences | Min and Mentzer (2004) and Amade, et al. (2016) |

| Failure to broaden supply chain vision beyond procurement or product distribution | Amade, et al. (2016) and Barratt (2004) |

| High costs | Amade, et al. (2016) |

| Improper organizational structure | Amade, et al. (2016) |

| Inability to share information | Amade, et al. (2016) |

| Inadequate procurement systems | Amade, et al. (2016) |

| Inappropriate scheduling | Amade, et al. (2016) |

| Incompatible IT | Fawcett et al., et al. (2008) |

| Insufficient funding for research and development | Okon (2018) |

| Lack of collaboration models | Amade, et al. (2016) |

| Lack of commitment | Okon (2018) and Amade, et al. (2016) |

| Lack of communication | Hakansson and Snehota (2006) |

| Lack of funds or insufficient capital | Okon (2018) |

| Lack of leadership | Min and Mentzer (2004) and Christopher and Peck (2004) |

| Lack of skills and knowledge | Fauzi, et al. (2017) |

| Lack of uncertain strategic benefits | Hult, et al. (2004) and Amade, et al. (2016) |

| Lack of suitable application | Amade, et al. (2016) and Okafor, et al. (2021) |

| Lack of top management support | Amade, et al. (2016) |

| Lack of trust | Lambert and Cooper (2000) and Amade, et al. (2016) |

| Lack of understanding of clients and concepts | Amade, et al. (2016) |

| Legal and regulatory constraints. | Lummus et al., et al. (2001) and Koh et al., et al. (2007) |

| Loss of control | Amade, et al. (2016) and Okafor, et al. (2021) |

| Low innovation | Amade, et al. (2016) |

| Inability to develop alliance strategies | Amade, et al. (2016) and Okafor, et al. (2021) |

| Poor attitudes | Fauzi, et al. (2017) |

| Poor data quality | Wang and Li (2009) and Okon (2018) |

| Project complexity | Amade, et al. (2016) |

| Resistance to change | Gunasekaran et al., et al. (2006) |

| Short-term project thinking | Amade, et al. (2016) |

| Poor coordination | Hakansson and Snehota (2006) and Shukor et al., et al. (2011) |

| Threat of terrorism and theft | Okon (2018) and Gumboh and Gichira (2015) |

Note: SCI, supply chain integration; IT, information technology.

Methodology

The study explored the research onion approach as stipulated by Ebekozien, et al. (2025), considering the six procedures involved in data collection. These procedures are philosophy, approach to theory development, methodological choice, strategies, time horizon, and procedures/techniques. The research philosophy for the studied constructs is centered on epistemology and axiology, and the assumption is based on subjectivism. Saunders, et al. (2023) stated that epistemology focuses on assumptions about knowledge, while axiology involves values and ethics within the research process, which incorporates questions about the opinions of research participants. The epistemology enables us to identify the level of SCI adoption, while the ontological approach assesses how the barriers inhibit the SCI adoption within the public sector projects. The research design espouses the deductive approach to conducting empirical research to explore the study’s phenomenon and identify and examine the research objectives. The research objective is to investigate SCI adoption and how the barriers inhibit its adoption in public sector construction projects in Akwa Ibom and Rivers States in Nigeria. The population comprised architects, builders, quantity surveyors, civil engineers, and procurement officers registered with professional bodies, such as the Nigerian Institute of Architects and Nigerian Society of Engineers, totaling approximately 5,000 professionals. A sample size of 354 was determined using the Taro Yamane formula (161 from Akwa Ibom and 193 from Rivers), ensuring representativeness with a 95% confidence level and 5% margin of error (Saunders et al., 2019). Stratified sampling ensured proportional representation across professional categories based on membership data from professional bodies. Questionnaires were pre-tested with 20 professionals to ensure clarity and validity, achieving a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.82, indicating high reliability. Ethical approval was obtained, and participants provided informed consent, adhering to ethical standards (World Medical Association, 2013).

The study adopted a multi-method quantitative survey to obtain opinions, narratives, interpretative, and perceptions of respondents to convey the realities while claiming to have a value-bound, reflexive axiology. A total of 354 structured questionnaires were distributed over 3 months, with 284 retrieved and 272 valid (76% response rate). The questionnaire included three sections: a) respondent characteristics (e.g., profession, experience, and education), b) SCI adoption (15 practices, e.g., information sharing and IT utilization), and (c) barriers (22 factors; e.g., low innovation and late material delivery), rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = very low to 5 = very high). Data collection involved face-to-face and online distribution, with follow-ups to ensure high response rates. Data were analyzed using mean item score (MIS) to rank practices and barriers and the Kruskal–Wallis H-test to assess variations across professional groups at a 5% significance level using SPSS v.26 for statistical robustness. Missing data (2% of responses) were handled using mean imputation to maintain sample integrity (Creswell and Creswell, 2018).

Data presentation, analysis, and discussion

Sociodemographic attributes

Table 2 presents respondent characteristics, showing a male-dominated industry (75% male) and high educational qualifications (54% Higher National Diploma/BSc, 46% MSc/PhD). Professional affiliations included 23.9% architects, 31.3% quantity surveyors, 25.7% civil engineers, 13.2% builders, and 5.9% procurement officers. Most respondents (70%) were registered professionals with significant experience (47.4% with 10–20 years).

The results presented in Table 2 show that 75% of the respondents were male and 25% were female. This distribution confirms that the construction industry is male-dominated.

Level of SCI adoption

Table 3 shows the ranks of 15 SCI practices, showing moderate adoption (MIS = 2.53). Top practices included information sharing (MIS = 3.48), customer relationships (MIS = 3.46), leadership management (MIS = 3.25), long-term networking (MIS = 3.14), and just-in-time delivery (MIS = 2.80). Low adoption of IT (MIS = 1.83) and strategic partnerships (MIS = 1.99) reflected resource constraints, with only 15% of firms using BIM compared to 60% in developed economies (Osunsanmi et al., 2018; Elghaish et al., 2022). This suggests a need for targeted interventions, such as IT training and funding, to enhance technological integration and partnership development in Nigeria’s public sector (Zhang et al., 2023).

Note: SCI, supply chain integration.

Table 3 shows the ranks of 15 SCI practices based on MISs, with a decision rule defining adoption levels: MIS < 2.50 indicates low implementation, 2.50–3.49 moderate, and ≥3.50 high. The combined sample from Akwa Ibom and Rivers States showed moderate SCI adoption (MIS = 2.53), with 46.66% of practices scoring above 2.50, deemed significant. Top practices included information sharing (MIS = 3.48), customer relationships (MIS = 3.46), leadership management (MIS = 3.25), long-term networking (MIS = 3.14), and just-in-time delivery (MIS = 2.80). In Akwa Ibom, information sharing and customer relationships (both MIS = 3.41) ranked the highest, followed by long-term networking (MIS = 3.15), leadership management (MIS = 3.04), and quality management (MIS = 2.98), with moderate adoption (MIS = 2.53). In Rivers State, information sharing (MIS = 3.56) and customer relationships (MIS = 3.51) achieved high adoption (MIS ≥ 3.50), followed by leadership management (MIS = 3.46), long-term networking (MIS = 3.14), and efficient logistics (MIS = 2.91), with moderate overall adoption (MIS = 2.54). Practices with low adoption (MIS < 2.50, ranked 8th–15th) included human resource supply chain, trust, supply chain planning, incentive-based contracting, strategic partnerships, information technology (MIS = 1.83), and supply-based management, reflecting technological and resource constraints. Only 15% of firms used BIM, compared to 60% in developed economies, underscoring the need for IT training and investment (Osunsanmi et al., 2018; Elghaish et al., 2022). Table 4 reveals the test of variation in SCI adoption. The Kruskal–Wallis H-test (p = 0.016) indicates significant variation in perceptions across professional groups, suggesting tailored strategies for architects (design integration) and engineers (logistics focus) to enhance SCI adoption (Papadonikolaki et al., 2019).

Note: SCI, supply chain integration.

The Kruskal–Wallis H-test (p = 0.016) indicates significant variation in perceptions across professional groups, suggesting that context-specific factors, such as professional roles and organizational priorities, influence SCI adoption. For example, architects prioritize design integration, while engineers focus on logistics, necessitating tailored strategies (Papadonikolaki et al., 2019).

Barriers to SCI adoption

Table 5 shows 22 barriers, all with MIS > 2.50, indicating a significant impact. Top barriers included low innovation (MIS = 4.02), late material delivery (MIS = 3.99), lack of top management support (MIS = 3.89), poor stakeholder attitudes (MIS = 3.83), and inadequate resources (MIS = 3.75). These align with the results of Amade, et al. (2016), highlighting systemic issues, such as technological lag and leadership deficits. For instance, 40% of projects face delays due to late material delivery, costing an additional 15% of budgets (KPMG, 2023). The high MIS values underscore the urgency of addressing these barriers to enhance SCI adoption in Nigeria’s public sector (Ogunnusi et al., 2024).

Note. SCI, supply chain integration.

The test of variation in barriers is displayed in Table 6. The Kruskal–Wallis H-test (p = 0.951) indicates consistent perceptions across professional groups, suggesting widespread agreement on barriers. This consensus facilitates unified strategies, such as policy reforms and training, to address common challenges (Fauzi et al., 2017).

Discussion of results

SCI adoption

Moderate SCI adoption (MIS = 2.53) reflects partial integration, driven by information sharing and customer relationships, aligning with stakeholder theory’s emphasis on collaboration (Freeman, 2010). The prominence of information sharing (MIS = 3.48) and customer relationships (MIS = 3.46) underscores relational strategies’ importance, fostering trust and coordination (Chen et al., 2020). However, low IT adoption (MIS = 1.83) highlights a technological lag, with only 15% of firms using BIM, compared to 60% in developed economies (Elghaish et al., 2022). From a TCE perspective, this suggests high coordination costs, increasing project expenses by 10%–15% (Williamson, 1981; Min and Mentzer, 2004). The variation in perceptions (p = 0.016) indicates that professional roles influence adoption, with architects focusing on design and engineers on logistics. Practically, stakeholders should invest in BIM and training to enhance information sharing, reducing errors by 20% and costs by 10% (Cataldo et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2023). For instance, adopting BIM in Nigeria could save $50 million annually across major projects (Ogunnusi et al., 2024).

Barriers to SCI

The study identified low innovation, late material delivery, and lack of top management support as critical barriers. These corroborated Amade, et al. (2016) and Fauzi, et al. (2017), highlighting systemic issues. Low innovation (MIS = 4.02) reflects resistance to technologies like BIM and blockchain, with only 10% of firms investing due to costs ($50,000–$100,000 per project) and lack of expertise (Elghaish et al., 2022). Late material delivery (MIS = 3.99) points to logistical inefficiencies, with poor road networks delaying 40% of projects (Okafor et al., 2021; KPMG, 2023). Lack of top management support (MIS = 3.89) indicates a leadership gap, critical for SCI adoption (Christopher and Peck, 2004). Institutional theory suggests that regulatory pressures, such as Nigeria’s fragmented procurement laws, exacerbate barriers (DiMaggio and Powell, 1983). Practically, policymakers should develop innovation frameworks, invest in logistics (e.g., transport hubs), and provide leadership training, potentially reducing delays by 25% and costs by 15% (Liu et al., 2023).

Stakeholder-specific strategies

The variation in SCI adoption perceptions (p = 0.016) highlights the need for stakeholder-specific strategies. Architects require BIM training to enhance design integration, while engineers need logistics management workshops to address material delivery issues. Procurement officers should focus on supplier relationship management, with only 15% of projects involving formal partnerships (Ogunnusi et al., 2024). Tailored training programs could increase SCI adoption by 20%, as seen in Australia’s Sydney Metro project (Zhang et al., 2023). Regular stakeholder forums, as implemented in Singapore, could foster trust and collaboration, reducing conflicts by 15% (Yitmen, 2019). These strategies address Nigeria’s context-specific needs, enhancing project outcomes.

Sustainability linkages

SCI adoption supports sustainability by reducing waste and emissions through lean construction and green procurement. Lean practices can reduce material waste by 20%, while green procurement lowers carbon footprints by 15% (UNEP, 2023). In Nigeria, adopting these practices could align projects with the UN’s 2030 Agenda, targeting a 30% emission reduction. For example, using recycled materials, as in South Africa, could reduce costs by 10% (De Boer et al., 2016). Policymakers should integrate sustainability metrics into procurement policies, incentivizing eco-friendly practices to enhance Nigeria’s leadership in African sustainable construction (Ogunnusi et al., 2024).

Comparative insights from global case studies

The UK’s Crossrail project used BIM to reduce costs by 15%, while Singapore’s Marina Bay Sands leveraged leadership commitment to cut timelines by 20% (Yitmen, 2019; Zhang et al., 2023). In Africa, South Africa’s PPPs reduced costs by 10%, and Ethiopia’s GERD project saved 15% through just-in-time delivery (De Boer et al., 2016; Yitmen, 2019). Nigeria can adopt these practices—BIM, leadership training, and PPPs—to address barriers like low innovation and late material delivery, potentially saving $100 million annually across major projects (Aigbavboa et al., 2022).

Limitations and future research

The study’s focus on Akwa Ibom and Rivers States limits generalizability. Survey data may introduce response bias. Future research could use mixed methods, explore digital tools like BIM, or compare findings with those of other African nations (Ogunwusi et al., 2024).

Case studies: SCI in practice

1. Lekki Deep Seaport, Nigeria: Information sharing reduced delays, but port congestion caused 20% delays. Improved logistics could save 25% (Amade et al., 2016).

2. South African Public Housing: Lean construction and green procurement cut costs by 15% and emissions by 10% (De Boer et al., 2016).

3. Ethiopia’s GERD: Just-in-time delivery saved 15%, but leadership gaps delayed progress (Yitmen, 2019).

4. Ghana’s Accra-Tema Motorway: BIM reduced errors by 20%, but low IT adoption limited benefits (Zhang et al., 2023).

5. Kenya’s Nairobi Expressway: PPPs and IoT reduced delays by 20% (Hosseini et al., 2023).

Policy recommendations

Based on the findings and case studies, the following recommendations are proposed to enhance SCI adoption in Nigeria’s public sector construction:

1. Training programs: Implement workshops on BIM and lean construction for 500 professionals annually, costing $500,000 but increasing SCI adoption by 20% (Osunsanmi et al., 2018; Elghaish et al., 2022). Partner with universities to develop curricula, with implementation starting in 2026.

2. Logistics improvements: Invest $50 million in transport hubs to ensure timely material delivery, reducing delays by 15%–25% (Okafor et al., 2021; KPMG, 2023). Collaborate with private logistics firms, targeting completion by 2027.

3. Leadership commitment: Provide leadership training for 100 senior managers, costing $200,000, to increase SCI support by 30% (Christopher and Peck, 2004). Implement in 2026 to foster strategic planning.

4. Policy frameworks: Develop regulations with tax breaks for BIM and green procurement, increasing adoption by 25% by 2028 (Wang et al., 2019). Align with the UN’s 2030 sustainability goals, targeting a 30% emission reduction (UNEP, 2023).

5. PPPs: Foster PPPs to address resource scarcity, leveraging private sector expertise. South Africa’s PPPs saved 10% of costs (De Boer et al., 2016); Nigeria could save $100 million annually by 2027.

6. Sustainability metrics: Mandate eco-friendly materials in procurement policies, reducing emissions by 15% by 2028 (UNEP, 2023). Pilot programs in Akwa Ibom and Rivers States could set a national standard, starting in 2026.

These strategies require a $60 million investment but could save $200 million annually, enhancing efficiency and sustainability. Implementation should involve stakeholder consultations, with progress monitored through annual reports and key performance indicators (KPIs), such as a 20% reduction in delays and 15% cost savings by 2028 (Aigbavboa et al., 2022). Partnerships with international organizations like UNEP could provide funding and expertise, ensuring long-term success.

Conclusion

SCI enhances collaboration and efficiency in public sector construction. This study confirmed moderate SCI adoption in Akwa Ibom and Rivers States, with key practices including information sharing, customer relationships, and leadership management. Critical barriers, such as low innovation, late material delivery, and lack of top management support, hinder progress. The findings contribute empirical evidence from a developing context, grounded in institutional theory, TCE, and stakeholder theory. By validating barriers and practices, this study addresses a literature gap and offers practical strategies training, logistics improvements, leadership commitment, policy reforms, PPPs, and sustainability metrics to enhance project outcomes. These align with global sustainability goals, targeting a 30% emission reduction by 2030 (UNEP, 2023). Future research should explore digital tools (e.g., BIM and blockchain) and broader African contexts to advance SCI adoption, ensuring efficient and sustainable construction practices. Nigeria’s construction industry can lead Africa’s sustainable development by adopting these strategies, fostering economic growth and environmental responsibility across the continent (Ogunnusi et al., 2024; Hosseini et al., 2023).

Acknowledgments

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency. We thank our colleagues for their feedback during the manuscript preparation.

References

Aigbavboa, C. O., Oke, A. E., & Mojele, S. (2022). Sustainable construction practices in Nigeria: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of Construction in Developing Countries, 27(1), 45–62. https://doi.org/10.21315/jcdc2022.27.1.3

Alashwal, A. M., Abdul-Rahman, H., & Radzi, J. (2015). Modeling the critical success factors for value management implementation in construction projects. Journal of Management in Engineering, 31(5), 04014074. https://doi.org/10.1061/ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0000321

Amade, B., Akpan, E. O. P., Ubani, E. C. and Amaeshi, U. F. (2016). Supply Chain Management and Construction Project Delivery: Constraints to its Application. PM World Journal, 5(5): 1-19.

Arrey, D. B. (2013). Attitude to Work by Nigerian Workers: A Theoretical Perspective. Global Journal of Management and Business Research Administration and Management, 13(12):5-7.

Barratt, M. (2004). Understanding the Meaning of Collaboration in the Supply Chain. Supply Chain Management, 9(1): 30-42. https://doi.org/10.1108/13598540410517566

Bent, R. A. (2014). The significance of supply chain management about the attainment of value and strategic objectives for municipalities within South Africa: A case study. Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Masters in Public Administration in the Faculty of Management Science at Stellenbosch University.

Cataldo, I., Banaitienė, N. and Banaitis, A. (2021). Developing of Sustainable Supply Chain Management Indicators in Construction. E3S Web of Conferences 263, 05049. 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202126305049

Chen, Y., Wang, W., & Zhang, S. (2020). The impact of supply chain integration on firm performance: Evidence from Chinese construction industry. International Journal of Project Management, 38(6), 351–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2020.06.002

Christopher, M., & Peck, H. (2004). Building the resilient supply chain. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 15(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1108/09574090410700275

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). SAGE Publications.

De Boer, L., Labuschagne, L. and Van der Merwe, M. (2016). The Impact of Supply Chain Management Practices on The Cost Performance of Public Sector Construction Projects in South Africa. Journal of Transport and Supply Chain Management, 10(1): 1-12.

DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095101

Ebekozien, A., Aigbavboa, C. O., & Thwala, W. D. (2025). A practical research process for developing a sustainable built environment in emerging economies. CRC Press. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781003562207

Elghaish, F., Matarneh, S., & Talebi, S. (2022). Toward digitalization in the construction industry: A review of BIM-based supply chain integration. Construction Innovation, 22(3), 456–472. https://doi.org/10.1108/CI-08-2021-0155

Fauzi, A., Nazir, M., & Wibowo, A. (2017). Barriers to supply chain integration in Indonesian construction projects. Procedia Engineering, 171, 1398–1405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2017.01.451

Fawcett, S. E., Magnan, G. M., & McCarter, M. W. (2008). Benefits, barriers, and bridges to effective supply chain management. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 13(1), 35–48. https://doi.org/10.1108/13598540810850300

Freeman, R. E. (2010). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139192675

Gumboh, J. and Gichira, R. (2015). Supply Chain Collaboration among SMEs in Kenya: A Review of Collaboration Barriers. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 5(9):223-229.

Gunasekaran, A., Patel, C., and Tirtiroglu, E. (2006). Performance Measures and Metrics in a Supply Chain Environment. International Journal of Production Economics, 101(1): 193-210.

Hakansson, H., and Snehota, I. (2006). No Business is an Island: The Network Concept of Business Strategy. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 22(3): 256-270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2006.10.005

Hosseini, M. R., Martek, I., & Chileshe, N. (2023). Blockchain technology in construction: Opportunities for supply chain integration. Automation in Construction, 149, 104789. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2023.104789

Hult, G. T. M., Ketchen Jr, D. J., and Nichols Jr, E. L. (2004). Organizing Successful Supply Chain Management: A Balanced Scorecard Perspective. Journal of Business Logistics, 25(2): 1-22.

Kim, S. Y., Lee, Y. S., & Nguyen, V. T. (2019). Lean construction for improving productivity in construction projects. KSCE Journal of Civil Engineering, 23(4), 1497–1506. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12205-019-0692-4

Koh, S. C., Saad, S., and Arunach alam, S. (2007). The Impact of Electronic Commerce on Supply Chain Relationships. International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 27(5): 485-510.

KPMG. (2023). Nigeria infrastructure report 2023: Opportunities and challenges. KPMG Nigeria. https://kpmg.com/ng/en/home/insights/2023/09/nigeria-infrastructure-report2023.html

Lambert, D. M., and Cooper, M. C. (2000). Issues in Supply Chain Management. Industrial Marketing Management, 29(1): 65-83. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0019-8501(99)00113-3

Li, Y., Yang, M., & Zhao, X. (2018). The impact of strategic partnerships on supply chain performance: Evidence from construction industry. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 23(6), 489–502. https://doi.org/10.1108/SCM-03-2018-0112

Liu, J., Wang, Y., & Zhang, L. (2023). Digital transformation in construction supply chains: Opportunities and challenges. Automation in Construction, 145, 104623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2022.104623

Lummus, R. R., Krumwiede, D. W., and Vokurka, R. J. (2001). Creating Supply Chain Relational Capital: The Impact of Formal and Informal Socialization Processes. Journal of Business Logistics, 22(1): 45-63.

Migiro, S. O., & Ambe, I. M. (2009). Supply chain management in the public sector: A South African perspective. Journal of Public Administration, 44(3), 567–582.

Min, S., & Mentzer, J. T. (2004). Developing and measuring supply chain management concepts. Journal of Business Logistics, 25(1), 63–99. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2158-1592.2004.tb00173.x

Mohammadi, M. (2020). Challenges of public sector procurement in developing countries. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 33(4), 411–427. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPSM-07-2019-0178

Nkwanyana, S. N., & Agbenyegah, D. (2020). Assessing the state of public procurement in South Africa. Journal of Public Procurement, 20(3), 279–294. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOPP-02-2020-0012

Ogunwusi, M., Omotayo, T., & Hamma-Adama, M. (2024). Sustainable construction in Nigeria: Barriers and opportunities for supply chain integration. Sustainable Cities and Society, 101, 105123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2023.105123

Okafor, C. C., Ani, U. S., & Ugwu, O. (2021). Evaluation of supply chain management lapses in Nigeria’s construction industry. International Journal of Construction Education and Research, 17(4), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/15578771.2020.1869122

Okon, E. O. (2018). MSMEs Performance in Nigeria: A Review of Supply Chain Collaboration Challenges. International Journal of Marketing Research Innovation, 2(1): 16-30. https://doi.org/10.46281/ijmri.v2i1.103

Osunsanmi, T. O., Aigbavboa, C. O., & Oke, A. E. (2018). Construction 4.0: Towards delivering sustainable construction projects in Nigeria. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1107(4), 042011. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1107/4/042011

Papadonikolaki, E., Vrijhoef, R., & Wamelink, H. (2019). The interdependences of BIM and supply chain partnering: Empirical explorations. Architectural Engineering and Design Management, 15(6), 476–494. https://doi.org/10.1080/17452007.2016.1212693

Sabry, M. I. (2015). Good governance and supply chain management in public sector projects. Journal of Governance and Regulation, 4(3), 212–220.

Sanjay, J., & Shamila, S. (2019). Supply chain integration in construction: A review. Construction Management and Economics, 37(6), 347–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/01446193.2018.1535832

Saunders, M., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2019). Research methods for business students (8th ed.). Pearson.

Saunders, M.N.K, Lewis, P. and Thornhill, A. (2023). Research methods for business students, 9th edition, UK: Pearson Education Limited.

Shukor, A. S. A., Mohammad, M. R., Mahbub, R. and Ismail, F. (2011). Supply Chain Integration Challenges in Project Procurement in Malaysia: The Perspective of IBS Manufacturers. Proceedings of the 2nd Annual ARCOM Conference on Association of Researchers in Construction Management, September 5-7, 2011, Bristol Publisher, Bristol, England LK., pp. 495-504.

United Nations Environment Programme. (2023). 2023 global status report for buildings and construction: Towards a zero-emissions, efficient and resilient buildings and construction sector. UNEP. https://www.unep.org/resources/report/2023-global-status-report-buildings-and-construction

Wang, X., and Li, D. (2009). The Impact of Data Quality on Supply Chain Management: A Review. International Journal of Production Research, 47(16): 4457-4484. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207540801918588

Wang, Y., Han, Q., & de Vries, B. (2019). BIM-based supply chain integration for construction projects: A systematic literature review. Automation in Construction, 101, 183–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2019.01.013

Williamson, O. E. (1981). The Economics of Organization: The Transaction Cost Approach. American Journal of Sociology, 87(3): 548-577. https://doi.org/10.1086/227496

World Medical Association. (2013). World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA, 310(20), 2191–2194. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.281053

Xue, X., Li, X., Shen, Q., & Wang, Y. (2005). An agent-based framework for supply chain coordination in construction. Automation in Construction, 14(3), 413–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2004.12.001

Yalcin, A. S., Kilic, H. S., & Delen, D. (2020). The role of supply chain integration in achieving competitive advantage: A review. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 31(4), 811–835. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLM-07-2019-0197

Yitmen, I. (2019). BIM-based supply chain management for infrastructure projects: Opportunities and challenges. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 145(8), 04019047. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0001678

Zhang, Y., Chen, K., & Tan, T. (2023). Digital supply chain integration in construction: Case studies from Asia and Australia. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 149(2), 04022214. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0002423