Construction Economics and Building

Vol. 25, No. 3/4

December 2025

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Win–Win Approach to Subcontracting in Building Construction: Sri Lankan Perspective

Imasha R. Pasqual1,2,*, Lesly Ekanayake3

1 Department of Civil Engineering, University of Moratuwa, Sri Lanka, irpasqual@gmail.com

2 Department of Civil Engineering, Sri Lanka Institute of Information Technology, Sri Lanka, imasha.p@sliit.lk

3 Department of Civil Engineering, University of Moratuwa, Sri Lanka, lesly@uom.lk

Corresponding author: Imasha R. Pasqual, Department of Civil Engineering, Sri Lanka Institute of Information Technology, Sri Lanka, imasha.p@sliit.lk

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v25i3/4.9573

Article History: Received 29/01/2025; Revised 22/09/2025; Accepted 13/10/2025; Published 05/12/2025

Citation: Pasqual, I. R., Ekanayake, L. 2025. Win–Win Approach to Subcontracting in Building Construction: Sri Lankan Perspective. Construction Economics and Building, 25:3/4, 339–357. hhttps://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v25i3/4.9573

Abstract

Subcontracting has long been studied due to subcontractors’ critical role in construction. However, significant issues persist, especially in developing countries like Sri Lanka, impacting project performance. These issues between main contractors and subcontractors stem from a lack of mitigation methods incorporating relationship management into traditional practices. Furthermore, most prior mitigation strategies are not favorable to both parties. This research aims to develop a “win–win” approach to subcontracting, focusing on relationship and performance management, specifically applicable to building construction. A mixed-method research approach was employed, involving literature review, questionnaire survey, and semi-structured interviews. Quantitative data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, while qualitative data were analyzed thematically. Findings reveal that effectively managing critical factors that influence both subcontracting relationships and subcontractor performance can lead to mutually beneficial outcomes. The study identified critical factors affecting the subcontracting relationship as mutual trust, good communication, and a clear understanding of the work scope by the subcontractor, while for subcontractor performance, the critical factors include time and cost management capabilities of the subcontractor, the availability of finance and working capital for both parties, and issues such as material price increase and inflation rate when subcontractors supply materials. The findings emphasize that prioritizing mutual satisfaction throughout the subcontracting process is essential for implementation. Recommendations provided in this study aim to improve these critical factors, offering practical solutions to enhance project efficiency and individual performance. This research provides valuable insights for developing organizational policies or industry guidelines, particularly for the unique challenges being faced in developing countries.

Keywords

Developing Countries; Construction Project Management; Performance Management; Relationship Management; Subcontractor Partnership

Introduction

Subcontractors have emerged as pivotal stakeholders in the construction industry, with main contractors being increasingly reliant on their specialized expertise and resources. The complex and dynamic nature of modern construction projects renders it inefficient and economically impractical for general contractors to maintain a full-time workforce of skilled workers or possess the specialized equipment required for every task (De Graaf et al., 2023). As a result, subcontracting has become a strategic imperative to optimize resource allocation, reduce costs, and enhance operational flexibility (Mahmoudi and Javed, 2022).

The significance of subcontracting is particularly pronounced in contexts like Sri Lanka, where labor shortages pose substantial challenges to project timelines and budgets (Manoharan et al., 2020). Moreover, the inherent volatility of the construction sector necessitates strategic partnerships to mitigate risks associated with market fluctuations (Shishehgarkhaneh et al., 2024). Subcontractors have thus evolved into the most important resource available to main contractors, contributing significantly to project success over the past decade (Jin et al., 2013).

Given the increasing substantial role of subcontractors, many studies have examined the dynamics of the main contractor–subcontractor relationship in recent decades (Chiang, 2009; Tan et al., 2017). These studies have found numerous issues that continue to affect the subcontracting landscape in construction (Arditi and Chotibhongs, 2005; Martin and Benson, 2021). However, previous research has often proposed unilateral solutions that fail to adequately address the complex interplay of interests between the two parties.

Prior studies have established the critical influence of the main contractor–subcontractor relationship on overall project performance (Abeysekara and McLean, 2001; Choudhry et al., 2012; Inayat et al., 2015; Tan et al., 2017; Mudzvokorva et al., 2020). Consequently, comprehending and managing the factors that shape this relationship is essential for achieving project objectives. However, traditional performance management approaches have fallen short in fostering mutually beneficial subcontract relationships. This may explain why, despite extensive research on subcontract management since the early 1990s, significant grievances between the two parties persist in the construction industry to this date. Accordingly, recent research highlights the need for a balanced approach that integrates relationship management and performance management.

This study aims to address this gap by developing a win–win approach that prioritizes the interests of both main contractors and subcontractors. Drawing on a conceptual framework proposed in prior literature, the research investigates the critical factors influencing their relationship and performance to provide actionable insights for enhancing collaboration and project outcomes. In order to gain a more holistic understanding, a mixed-method research approach was employed for this study, encompassing a literature review, a questionnaire survey, and semi-structured interviews.

The findings of this study are expected to contribute to the advancement of construction management practices in developing countries like Sri Lanka, where the construction sector plays a vital role in economic growth (Lewis, 2008). By fostering stronger and more productive main contractor–subcontractor relationships, this research intends to enhance project delivery, reduce costs, and ultimately contribute to strengthening the national economy of developing countries through improvement in the construction sector.

Literature review

The complexities of subcontractor management

The construction industry has a long history of employing subcontractors, but the nature of these relationships has evolved over time. Traditionally, subcontracting was characterized by adversarial dynamics, with main contractors holding significant power over subcontractors (Shimizu and Cardoso, 2002). One of the earliest studies by Hinze and Tracey (1994) found that subcontractors often felt that the main contractors did not have the best interests of the subcontractors in mind. However, another perspective emerges in a subsequent study by Kale and Arditi (2001), who revealed that the main contractors have a favorable view of maintaining high-quality relationships with subcontractors. While these contrasting views highlight the complexities of subcontracting, the challenges are particularly pronounced in developing countries like Sri Lanka, where the subcontracting environment remains largely informal. A study conducted by Chamara, et al. (2015) revealed a significant gap existing between the required level of performance and the current performance level of subcontractors. More recently, Deep, et al. (2023) discovered that relationships between main contractors and subcontractors still remain at arm’s length. Accordingly, when proposing a “win–win” approach to subcontracting, it is pertinent to consider the complex nature of subcontract management.

The evolution of subcontractor management

Research has extensively explored various aspects of subcontractor management to address prevalent industry challenges (Olsson, 1998; Loosemore and Andonakis, 2007; Enshassi et al., 2008; Piasny and Pasławski, 2015; Rodrigo and Perera, 2016; Assaad et al., 2020). Traditionally, a performance-based approach dominated subcontractor management strategies. However, a growing body of research has emphasized the importance of relationship management alongside performance metrics (Manu et al., 2015; Fagbenle et al., 2018). Thomas and Flynn (2011) were among the first to propose a dual-pronged approach, encompassing both work and people management, to manage subcontractors effectively.

The construction industry has increasingly recognized the value of relationship management, particularly considering its correlation with project performance (Meng, 2012). While performance metrics remain crucial, relationship-driven management fosters collaboration and productivity. Meng (2012) further suggested that performance management is frequently used at the operational level, while relationship management is helpful at a strategic level. This integrated approach surpasses traditional project management methodologies.

Strategic partnering has emerged as a complementary strategy to relationship management to enhance project outcomes (Meng, 2012). Partnering is defined as a strategic, long-term collaboration focused on cost reduction and efficiency (Harris et al., 2021). While early research suggested a general industry willingness to embrace partnering (Black et al., 2000), challenges such as differing perspectives and traditional, arm’s length relationships have hindered its widespread implementation (Dainty et al., 2001; Greenwood, 2001). However, partnering has gained traction in the construction industry in recent years due to its perceived organizational advantages (Elsayegh and El-Adaway, 2021). Its effectiveness, nonetheless, remains dependent upon mutual trust and understanding. Despite these obstacles, the potential benefits of partnering make it a valuable component when developing a “win–win” approach to subcontracting.

Risk management in subcontracting

Risk management has emerged as a critical component of effective subcontractor management due to the inherent uncertainties within construction projects. Research has examined the relationship between risk management and subcontractor performance, highlighting its potential to mitigate challenges and foster positive relationships (Perera et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2018). A balanced approach that considers the perspectives of both main contractors and subcontractors is essential for equitable risk allocation.

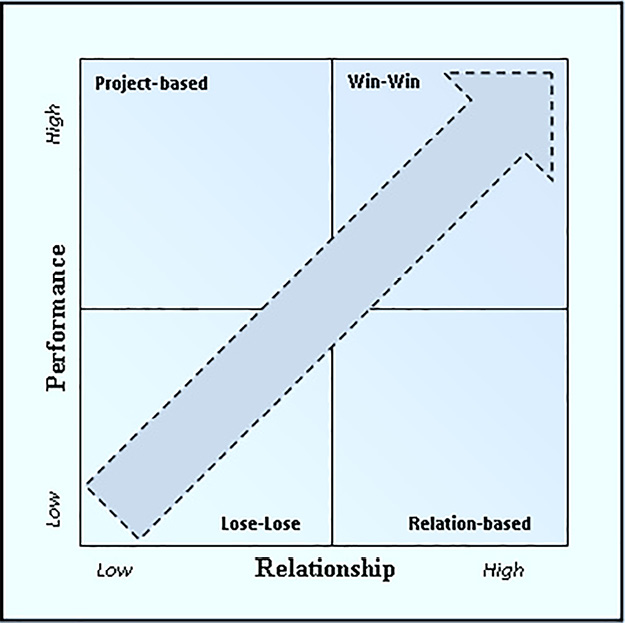

Lee, et al. (2018) proposed a win–win strategy for a sustainable relationship between the main contractor and the subcontractor based on the identified subcontracting risks related to the partnership and performance. The “win–win” strategy is a well-known negotiation philosophy in which all parties to an agreement or a deal stand to realize their fair share (<100%) of the benefits and/or profits. The x-axis of the proposed win–win strategy matrix was the partnership degree, while the y-axis was the subcontractor’s performance in terms of cost, time, and quality of a project. It was portrayed from this matrix that to achieve a “win–win” outcome, both the partnership and the performance need to be positive. This proposed strategy matrix also illustrated three other possibilities in addition to the “win–win” quartile. When both the performance and partnership were weak, it produced the worst-case scenario where both parties lost. If only the performance were strong, then the relationship would be project-based and would not last beyond the specific project. If only the relationship were strong, then the project performance would suffer. Therefore, Lee, et al. (2018) stated that both parties must focus on the lacking factor to improve both project-based and relation-based scenarios. However, this study has one significant limitation. It investigated a win–win strategy solely based on the view of the subcontractor. Since the main contractor traditionally holds the position of power in subcontracting (Jin et al., 2013), and still continues to do so a decade later, validating the findings from the main contractors is important for this study to be more meaningful and reliable.

Therefore, this research study intends to develop this existing concept built on the foundation of risk management by integrating key concepts discussed in this literature review, such as relationship management and performance management, while prioritizing the mutual benefits of both parties.

Research methodology

Scope of the study

Prior studies have employed diverse classification schemes for subcontractors (Shimizu and Cardoso, 2002; Tesha and Luvara, 2017). In this study, the term “subcontractor” is used to represent non-specialized civil subcontractors carrying out basic activities of a building project, such as formwork, masonry, and concrete work. No other distinctions, such as domestic, nominated, and named subcontractors, were made. As the findings of the study by Lee, et al. (2018) established the perceptions of the subcontractors for a “win–win” strategy in subcontracting, this study focused on the view of the main contractors to validate and further develop this concept for subcontracting.

In Sri Lanka, all contractors involved in construction are required to register with the Construction Industry Development Authority (CIDA), which grades them primarily on their financial capacity. Accordingly, Sri Lankan contractors with a high CIDA grading (C1 to CS2) for buildings were approached for the questionnaire on the basis that they were predominantly involved in building projects as main contractors. At the time of the study, 38 such organizations were eligible to participate. Since the representatives of the main contractor based in the head office and site may have varying opinions about subcontracting, this study tried to examine the opinions of both decision-makers at the head office and project managers at the site.

Research approach and design of study

To achieve the objective of this study, the survey method has been predominantly adopted in this mixed-method research design. First, an extensive review of prior literature was carried out.

Figure 1 presents the key concept of the “win–win” approach to subcontracting, adapted from Lee, et al. (2018) to the context of the Sri Lankan construction industry. Certain terms and labels were modified to reflect local terminology. As aforementioned, the three scenarios outside the win–win quadrant of the matrix are neither sustainable nor beneficial for the project and both parties: the main contractor and subcontractor. This framework guided the development of the questionnaire and semi-structured interview guide, particularly in identifying and categorizing factors affecting relationship and subcontractor performance.

Figure 1. Key concept of the “win–win” approach to subcontracting

Thereafter, the preliminary questionnaire was designed by referring to the previous research relevant to this study (Perera et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2018). The questionnaire was then refined through a pilot study involving five industry experts representing diverse roles in project management, quantity surveying, and civil engineering. Their feedback led to the removal of factors deemed irrelevant to the Sri Lankan context, rewording of items to reflect local terminology, and explicit clarification of terms such as “win–win outcome”, “bid shopping”, and “subcontractor”. To enhance comprehension, plain English was used, several items were combined to reduce respondent fatigue, and the questionnaire structure was reorganized for better flow. These refinements ensured clarity, contextual relevance, and practicality of the final questionnaire distributed in the study.

The finalized questionnaire was developed using Google Forms. It comprised four sections, including respondent demographics, the ranking of identified factors on a 5-point Likert scale separately for relationship and subcontractor performance, overall opinions on the win–win approach proposed in this study, and perceptions regarding its potential implementation in the industry. The questionnaire was distributed online via email to 38 eligible organizations. To minimize potential bias, decision-makers representing diverse backgrounds from the head offices of participating organizations were invited to respond to the questionnaire at this stage. Each organization was encouraged to nominate at least two employees, aiming for a total of 76 responses. Follow-up reminders were sent to maximize participation. Due to its anonymous nature, it was not possible to determine which organizations had responded; however, the number of responses indicated that some organizations submitted multiple entries while others did not respond. Data collection was closed when a 58% response rate was achieved, exceeding the 35% benchmark that Baruch (1999) suggested for studies involving top management. The responses were organized in Excel and analyzed using the SPSS software.

The questionnaire was administered before the semi-structured interviews to identify and prioritize key factors through quantitative ranking, thereby providing a structured basis for the subsequent qualitative phase. The ranking of the identified factors informed the flow of the interviews, where the interview guide was organized according to the relative criticality of factors revealed from the quantitative analysis. According to Saunders, et al. (2009), semi-structured interviews provide opportunities to “probe” answers and, therefore, can add significance and depth to the data obtained from the questionnaire. The outline of the semi-structured interview had open-ended questions, as they encouraged interviewees to provide developmental answers. Moreover, according to Easterby-Smith, et al. (2021), open questions can assist in avoiding bias. Interviewees were shown the categorization of the identified factors into least critical, less critical, critical, more critical, and most critical categories by the questionnaire respondents separately for relationship and subcontractor performance. Then, they were encouraged to give their opinion regarding the categorization, how these factors can be improved at the site, and any other remarks they may have. The overall opinion of the interviewee regarding the proposed “win–win” approach to subcontracting was also explored, together with their opinion on the possibility of implementation and ways to improve the implementation process. Although a common outline was followed, the semi-structured format allowed flexibility for deeper exploration, and both English and Sinhala were used based on interviewee preference.

Managers generally prefer to be interviewed rather than complete a questionnaire, especially when the interview topic is relevant and interesting to their current work (Saunders et al., 2009). Moreover, fewer participants are considered satisfactory when testing the applicability of an existing theory in order to develop it to better suit the testing surroundings through interviews (Saunders et al., 2009). Accordingly, the same 38 organizations were contacted to request interviews with their project managers. From the organizations that responded, five project managers were selected to represent the population, taking into account logistical considerations and time constraints. The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. The qualitative data were then analyzed using thematic analysis, a widely accepted method for identifying, coding, and categorizing patterns and themes within qualitative data (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Transcripts were manually reviewed, coded, and sorted to identify recurring themes and insights related to the research objectives. While the analysis was performed manually, it followed a systematic approach consistent with qualitative research standards. For transparency, coding was cross-checked and organized in Microsoft Excel, facilitating the grouping of responses under thematic categories.

Accordingly, both quantitative and qualitative data were collected and analyzed separately in this research study.

Results and discussion

Demographics

The demographic profiles of the questionnaire respondents and the interviewees of semi-structured interviews are presented in Table 1. This information helped understand the characteristics of study participants and how they may have impacted the findings while also indicating diverse backgrounds representative of the broader population of industry professionals.

Note: CIDA, Construction Industry Development Authority.

Questionnaire findings

First, a reliability analysis was conducted to find the internal consistency of factors included in the questionnaire by calculating Cronbach’s alpha (Cronbach, 1951) as shown in Table 2. Since the values of both questionnaire sections exceeded 0.7, the factors chosen for the survey were internally consistent (Nunnally and Bernstein, 1978).

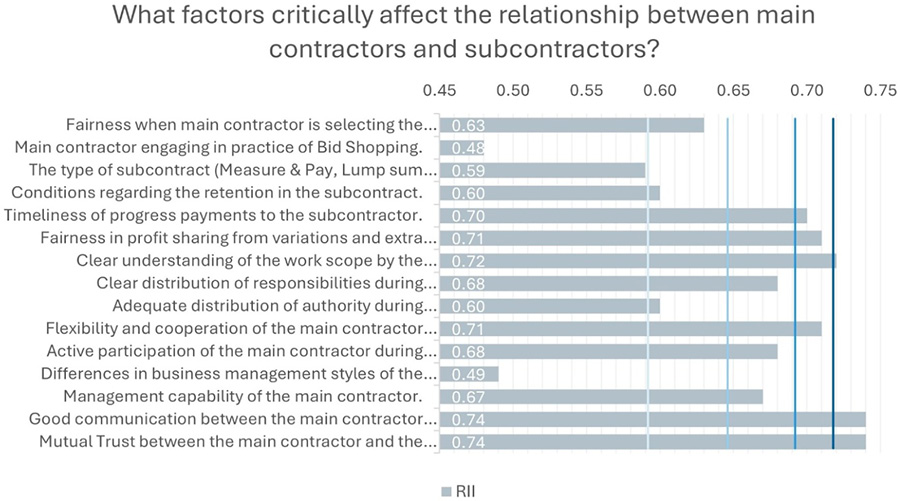

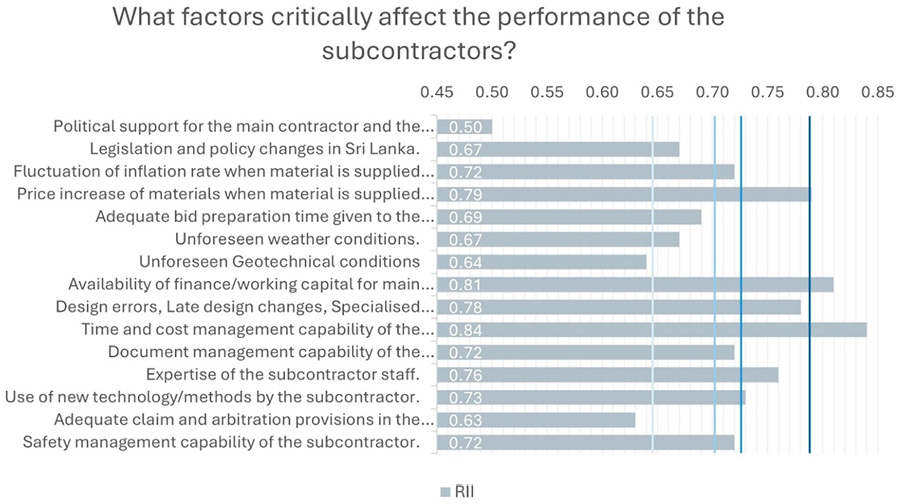

Thereafter, the relative importance index was calculated following the methodology adapted from Gündüz and Özdemir (2013). The factors were then categorized into five sections using quintile-based classification, as illustrated in Figures 2 and 3.

Figure 2. Relative importance index of factors critical for the subcontracting relationship

Figure 3. Relative importance index of factors critical for the performance of the subcontractor

Notably, the questionnaire respondents perceived the performance factors as more critical than the relationship factors. This quintile categorization of the 15 factors, as seen in Table 3, formed the basis for the outline of the semi-structured interview.

Note: RII, relative importance index.

All questionnaire respondents unanimously agreed that the management of factors affecting the relationship between the main contractor and subcontractor, as well as the performance of the subcontractor, would result in a “win–win” outcome, which validates the basis of this research study.

In the concluding remarks, questionnaire respondents stated that, according to their experience, it is possible to implement this approach in the building construction industry of Sri Lanka. However, two respondents noted that implementation is difficult because of the prevalent attitude in the industry and poor understanding among the main contractors and subcontractors. These statements were examined in detail during the semi-structured interviews to obtain a better understanding.

Semi-structured interview findings

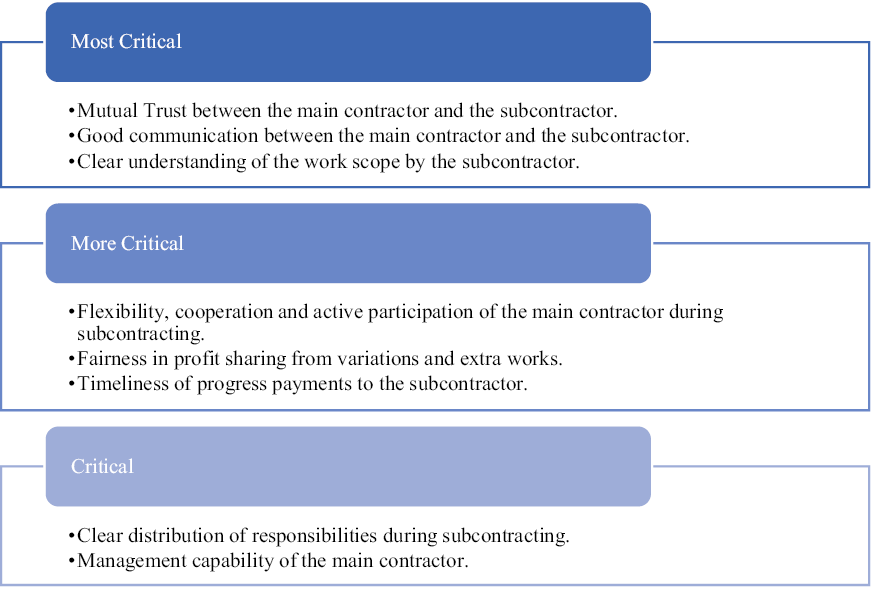

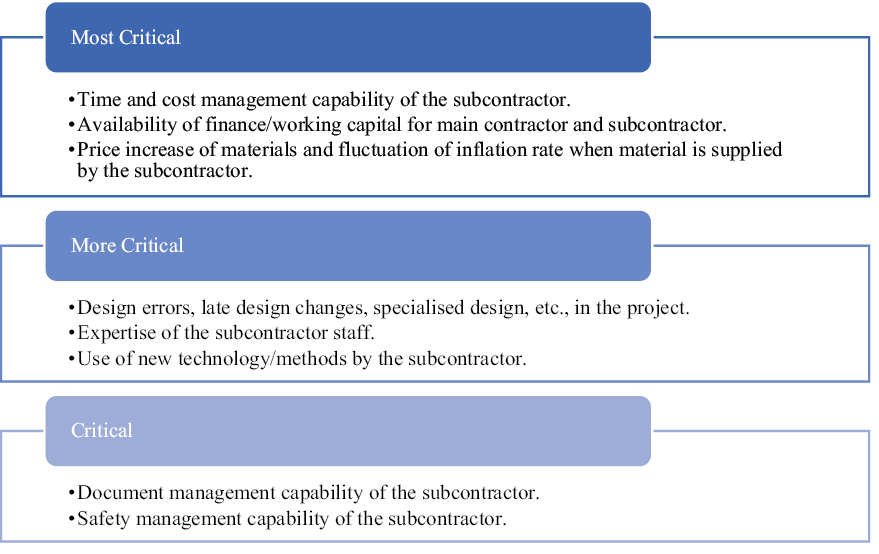

According to the comments made by the interviewees, the criticality of the factors was revised, as seen in Figures 4 and 5. Some factors deemed less than critical were excluded, while factors closely associated were combined after the interview findings.

Figure 4. Critical factors for the subcontracting relationship

Figure 5. Critical factors for the performance of the subcontractor

The subsequent sections of the semi-structured interviews included an in-depth exploration of these factors, along with recommendations from experienced project managers in the Sri Lankan construction industry on how they could be effectively managed at project sites. The recommendations obtained are summarized in Tables 4 and 5.

Apart from the aforementioned critical factors, project managers highlighted additional considerations for successful subcontracting in building construction projects in Sri Lanka. The importance of selecting a suitable subcontractor cannot be overstressed, as it is the first step in building a good relationship between the main contractor and the subcontractor. Once the relationship is initiated, top priority should be given to financial aspects when building a sustainable relationship, as it is a motivating factor for the subcontractors. Timely payments and fair compensation for idle time are crucial for fostering positive subcontractor relationships. While unforeseen circumstances can impact project timelines, subcontractors should not be expected to bear the financial burden disproportionately. Main contractors must prioritize the financial well-being of subcontractors, recognizing their limited capacity to absorb additional costs. This includes avoiding practices that shift costs to subcontractors, such as delaying payment claims, to maintain a cordial relationship with the client. A win–win approach necessitates mutual understanding and respect, with main contractors recognizing that their relationships with both the client and the subcontractor are equally important. Implementing regular rate adjustments for subcontractors can help mitigate the impact of inflation and encourage lasting relationships in developing countries like Sri Lanka. It is also critical to never assume that subcontractors have the same practices and the same level of knowledge as the main contractor. Many issues can be avoided throughout the project by clearly explaining what is expected from the subcontractor.

In developing countries, due attention must also be given to the contract between the main contractor and subcontractor. It can be observed that many subcontractors are not employed under a formal contract in Sri Lanka, although having a detailed contract is helpful to both parties. It may encourage the subcontractor to formalize the subcontracting relationship if a system is established by the relevant government institutions, departments in universities, and construction associations to provide free legal consultations for the subcontractor when drawing up contracts.

Furthermore, similar to the questionnaire respondents, interviewees also agreed that it is possible to implement a “win–win” approach to subcontracting to building construction projects in Sri Lanka if some challenges are overcome. They stated that the way main contractors treat the subcontractors in the industry is changing, primarily due to the high demand for subcontractors. Therefore, main contractors are trying to retain the subcontractors by building sustainable relationships. They also noted that it is important that the subcontractor reciprocates and makes an effort to maintain the relationship with the main contractor. Thus, the approach developed in this research study can be implemented step by step in the industry.

Conclusions

The findings of this study underscore the equally critical role of effective relationship management and performance management in achieving a win–win scenario for both main contractors and subcontractors in developing countries like Sri Lanka. The identified critical factors and the recommendations in the study contribute to the existing body of knowledge and can act as a catalyst to change the subcontracting landscape of developing countries like Sri Lanka.

By fostering strong, collaborative relationships, both main contractors and subcontractors can reap substantial benefits. This proposed approach not only enhances project efficiency but also drives individual performance improvement. Thus, it can be used not only as a framework for planning but also as an assessment tool for subcontracting. It can also be further developed as a policy to be adapted for subcontracting by an organization or as guidance for the relevant authorities to formalize subcontracting.

Main contractors must recognize the importance of subcontractor development as a catalyst for long-term success. Conversely, subcontractors must demonstrate reliability and a shared commitment to project success. This win–win dynamic is predicated on trust and respect. When taking any measures to manage any factor that affects the relationship or the performance of subcontractors, both the main contractor and the subcontractor must consider the other party’s satisfaction. This is the core principle of the proposed “win–win” approach to subcontracting. As discovered in this study, implementing this approach requires an attitude change and a cultural shift toward a collaborative relationship throughout the industry. While survey responses suggest that performance is still considered more important than relationships, it is also crucial to reiterate that this “win–win” approach necessitates equal emphasis on both parameters.

Since this study focused only on building projects in Sri Lanka, further studies are required to test the applicability of this approach to other sectors of construction. It is also important to conduct additional studies to gather the opinions of different types of subcontractors in construction regarding this approach. In addition, it would also be beneficial to conduct in-depth research on how to manage each identified critical factor in accordance with the proposed “win–win” approach and follow up with case studies that implement the recommendations given in this research study. Addressing these limitations in future studies would greatly benefit in further developing the practicality of the “win–win” approach proposed in this study for construction in developing countries like Sri Lanka.

References

Abeysekera, V., & McLean, C. (2001). Project success and relationships from a stakeholder perspective: a pilot study. In Proceedings of the 17th Annual ARCOM Conference, 5-7. Salford: Association of Researchers in Construction Management. https://www.arcom.ac.uk/-docs/proceedings/ar2001-485-494_Abeysekera_and_McLean.pdf

Arditi, D., & Chotibhongs, R. (2005). Issues in subcontracting practice. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 131(8), 866-876. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9364(2005)131:8(866)

Assaad, R., Elsayegh, A., Ali, G., El-Adaway, I., & Nabi, M. A. (2020). Understanding the sub-contractual relationship for proper management of construction projects. In Proceedings of Construction Research Congress 2020, 1119-1128. Reston: American Society of Civil Engineers. https://doi.org/10.1061/9780784482889.119

Baruch, Y. (1999). Response rate in academic studies: A comparative analysis. Human Relations, 52(4), 421–438. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872679905200401

Black, C., Akintoye, A., & Fitzgerald, E. (2000). An analysis of success factors and benefits of partnering in construction. International Journal of Project Management, 18(6), 423-434. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0263-7863(99)00046-0

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3(2), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Chamara, H. W. L., Waidyasekara, K. G. A. S., & Mallawaarachchi, H. (2015). Evaluating subcontractor performance in the construction industry. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Structural Engineering and Construction Management, 137-147. Kandy: International Conference on Structural Engineering and Construction Management.

Chiang, Y. H. (2009). Subcontracting and its ramifications: A survey of the building industry in Hong Kong. International Journal of Project Management, 27(1), 80-88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2008.01.005

Choudhry, R., Hinze, J., Arshad, M., & Gabriel, H. (2012). Subcontracting practices in the construction industry of Pakistan. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 138(12), 1353-1359. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0000562

Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297-334. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02310555

Dainty, A. R. J., Briscoe, G. H., & Millett, S. J. (2001). Subcontractor perspectives on supply chain alliances. Construction Management and Economics, 19(8), 841-848. https://doi.org/10.1080/01446190110089727

De Graaf, R., Pater, R., & Voordijk, H. (2023). Level of sub-contracting design responsibilities in design and construct civil engineering bridge projects. Frontiers in Engineering and Built Environment, 3(3), 192-205. https://doi.org/10.1108/FEBE-12-2022-0045

Deep, S., Gajendran, T., Jefferies, M., & Jha, K. N. (2023). Developing subcontractor–general contractor relationships in the construction industry: constructs and scales for analytical decision making. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 149(12), 04023136. https://doi.org/10.1061/JCEMD4.COENG-13630

Easterby-Smith, M., Jaspersen, L. J., Thorpe, R., & Valizade, D. (2021). Management and business research. Sage.

Elsayegh, A., & El-adaway, I. H. (2021). Holistic study and analysis of factors affecting collaborative planning in construction. Journal of construction engineering and management, 147(4), 04021023. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0002031

Enshassi, A., Choudhry, R. M., Mayer, P. E., & Shoman, Y. (2008). Safety performance of subcontractors in the Palestinian construction industry. Journal of Construction in Developing Countries, 13(1), 51-62.

Fagbenle, O., Joshua, O., Afolabi, A., Ojelabi, R., Fagbenle, O., Fagbenle, A., & Akomolafe, M. (2018). A framework for enhancing contractor-subcontractor relationships in construction projects in Nigeria. In Proceedings of Construction Research Congress 2018, 305-314. New Orleans: American Society of Civil Engineers. https://doi.org/10.1061/9780784481271.030

Greenwood, D. (2001). Subcontract procurement: Are relationships changing?. Construction Management and Economics, 19(1), 5-7. https://doi.org/10.1080/01446190010003380

Gündüz, M., Nielsen, Y., & Özdemir, M. (2013). Quantification of delay factors using the relative importance index method for construction projects in Turkey. Journal of Management in Engineering, 29(2), 133-139. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0000129

Harris, F., McCaffer, R., Baldwin, A., & Edum-Fotwe, F. (2021). Modern construction management. Wiley.

Hinze, J., & Tracey, A. (1994). The contractor-subcontractor relationship: The subcontractor’s view. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 120(2), 274-287. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9364(1994)120:2(274)

Inayat, A., Melhem, H., & Esmaeily, A. (2015). Critical success factors in an agency construction management environment. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 141(1), 06014010. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0000921

Jin, X. H. S., Zhang, G. K., Xia, B., & Feng, Y. (2013). Relationship between head contractors and subcontractors in the construction industry: A critical review. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Construction in the 21st Century: Changes in Innovation, Integration and Collaboration in Construction and Engineering, 1-8. North Carolina: East Carolina University. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/281236

Kale, S., & Arditi, D. (2001). General contractors’ relationships with subcontractors: A strategic asset. Construction Management and Economics, 19(5), 541-549. https://doi.org/10.1080/01446193.2001.9709630

Lee, J. K., Han, S. H., Jang, W., & Jung, W. (2018). Win-win strategy for a sustainable relationship between general contractors and subcontractors in international construction projects. KSCE Journal of Civil Engineering, 22(2), 428-439. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12205-017-1613-7

Lewis, T. M. (2008). Quantifying the GDP–construction relationship. In Economics for the modern built environment, (54-79). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203938577.ch2

Loosemore, M., & Andonakis, N. (2007). Barriers to implementing OHS reforms: The experiences of small subcontractors in the Australian construction industry. International Journal of Project Management, 25(6), 579-588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2007.01.015

Mahmoudi, A., & Javed, S. A. (2022). Performance evaluation of construction sub‐contractors using ordinal priority approach. Evaluation and Program Planning, 91, 102022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2021.102022

Manoharan, K., Dissanayake, P., Pathirana, C., Deegahawature, D., & Silva, R. (2020). Assessment of critical factors influencing the performance of labour in Sri Lankan construction industry. International Journal of Construction Management, 23(1), 144–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2020.1854042

Manu, E., Ankrah, N., Chinyio, E., & Proverbs, D. (2015). Trust influencing factors in main contractor and subcontractor relationships during projects. International Journal of Project Management, 33(7), 1495-1508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2015.06.006

Martin, L., & Benson, L. (2021). Relationship quality in construction projects: A subcontractor perspective of principal contractor relationships. International Journal of Project Management, 39(6), 633-645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2021.05.002

Meng, X. (2012). The effect of relationship management on project performance in construction. International Journal of Project Management, 30(2), 188-198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2011.04.002

Mudzvokorwa, T., Mwiya, B., & Mwanaumo, E.M. (2020). Improving the contractor-subcontractor relationship through partnering on construction projects in Zambia. KICEM Journal of Construction Engineering and Project Management, 10(1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.6106/JCEPM.2020.10.1.001

Nunnally, J. C. & Bernstein, I. H. (1978). Psychometric theory. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Olsson, R. (1998). Subcontract coordination in construction. International Journal of Production Economics, 56–57, 503-509. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0925-5273(97)00024-8

Perera, K.R.S., Gunatilake, S., Vijerathne, D.T., & Wimalasena, N.N. (2016). Risk allocation between main contractors and subcontractors in building projects in Sri Lanka. In Proceedings of the 5th World Construction Symposium 2016: Greening Environment, Eco Innovations and Entrepreneurship, Colombo: Ceylon Institute of Builders and Department of Building Economics, University of Moratuwa, 408-419.

Piasny, J., & Pasławski, J. (2015). Selection of subcontractors as the quality improvement tool in housing construction. Procedia Engineering, 122, 274-281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2015.10.036

Rodrigo, M.N.N., & Perera, B.A.K.S. (2016). Selection of nominated subcontractors in commercial building construction in Sri Lanka. In Proceedings of the 2016 Moratuwa Engineering Research Conference (MERCon), Moratuwa: Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineering, 210-215. https://doi.org/10.1109/MERCon.2016.7480141

Saunders, M., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2009). Research methods for business students. UK: Prentice Hall.

Shimizu, J.Y., & Cardoso, F.F. (2002). Subcontracting and cooperation network in building construction: a literature review. In Proceedings of the 10th Annual Conference of the International Group for Lean Construction, Gramado: The International Group for Lean Construction.

Shishehgarkhaneh, M. B., Moehler, R. C., Fang, Y., Aboutorab, H., & Hijazi, A. A. (2024). Construction supply chain risk management. Automation in Construction, 162, 105396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2024.105396

Tan, Y., Xue, B., & Cheung, Y.T. (2017). Relationships between main contractors and subcontractors and their impacts on main contractor competitiveness: An empirical study in Hong Kong. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 143(7), p.05017007. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0001311

Tesha, D.N.G.A.K., & Luvara, V.G.M. (2017). Main contractors’ strategies in managing construction quality of subcontracted works in Tanzania. International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology, 4(6), 1-17.

Thomas, H.R., & Flynn, C.J. (2011). Fundamental principles of subcontractor management. Practice Periodical on Structural Design and Construction, 16(3), 106-111. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)SC.1943-5576.0000087