Construction Economics and Building

Vol. 25, No. 3/4

December 2025

RESEARCH ARTICLE

The Effects of Disasters on Construction Wages: Role Played by Spatial Proximity

Sooin Kim1,*, Mahmut Yasar2, Mohsen Shahandashti3

1 Construction Management, Division of Engineering Technology, Wayne State University, 4885 Fourth St., Detroit, MI 48201, sooin.kim@wayne.edu

2 Department of Economics, The University of Texas at Arlington, 701 S. West Street, Arlington, TX, 76019, myasar@uta.edu

3 Department of Civil Engineering, The University of Texas at Arlington, 416 S. Yates St., Arlington, TX 76010, mohsen@uta.edu

Corresponding author: Sooin Kim, sooin.kim@wayne.edu

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v25i3/4.9568

Article History: Received 22/06/2024; Revised 03/04/2025; Accepted 10/04/2025; Published 05/12/2025

Citation: Kim, S., Yasar, M., Shahandashti, M. 2025. The Effects of Disasters on Construction Wages: Role Played by Spatial Proximity. Construction Economics and Building, 25:3/4, 186–209. https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v25i3/4.9568

Abstract

Natural hazards significantly threaten the built environment and infrastructure, resulting in a sudden and significant increase in reconstruction demand. Such an unforeseen post-disaster demand surge for reconstruction can inflate costs up to 50%, impeding prompt and efficient reconstruction efforts. The current study aimed to quantify the effect of disasters on construction wages in three Gulf Coast states (Louisiana, Texas, and Florida). To accomplish this, spatial Durbin models were utilized with a difference-in-differences specification to allow for feedback and spillover effects across counties. The results show that the impact of a disaster on construction wages works with a lag. Natural disasters caused a decrease in construction wages in the impacted counties during the disaster quarter, compared to counties that were not affected. However, construction wages increased one quarter later in the disaster-affected counties compared to the non-affected counties. The direct, indirect, and total effects of disasters on the counties’ wages indicate significant feedback and spillover effects across counties when a county experiences a disaster. The findings of this study carry significant policy implications for the city’s policymakers and decision-makers.

Keywords

Demand Surge; Construction Wages; Difference-In-Differences; Spatial Durbin Models; Spatial Multiple Imputation

Introduction

Rapid climate changes over recent decades have led to a significant rise in catastrophic events, causing widespread devastation globally (Ripple et al., 2024). Each year, the United States faces over a hundred natural disasters, resulting in numerous deaths and billions of dollars in damage to property and infrastructure (Smith, 2024). The total cost of 400 weather- and climate-related disasters since 1980 in the United States has reached approximately $2.8 trillion (Smith, 2020). Timely and effective reconstruction and recovery efforts are crucial to ensuring a community’s safety, survival, and long-term resilience in the wake of disasters (McEntire, 2021; Zhou, Zhang, and Evans, 2022; Kim, 2023). However, the unanticipated rise in reconstruction costs following disasters often hinders recovery efforts, exacerbating both direct and indirect economic losses (Pradhan and Arneson, 2021; Kim and Shahandashti, 2022b; Li et al., 2022; Kim, Shahandashti, and Yasar, 2023).

The sudden and substantial reconstruction cost inflation in the aftermath of disasters is often explained by the demand surge phenomenon (Ahmadi and Shahandashti, 2020; Kim and Shahandashti, 2022a). Demand surge is a socioeconomic phenomenon indicating that the reconstruction demand exceeds the regional supply capacity, and subsequently, the reconstruction costs increase after a disaster (Olsen and Porter, 2013). After Hurricane Katrina, most construction materials experienced statistically significant price inflation (Khodahemmati and Shahandashti, 2020). Sewer and water tubing pipe costs have increased by 10% following the Texas winter storm in 2021 (Kim and Shahandashti, 2022b). After the 2006 Yogyakarta earthquake in Indonesia, the wages and employment rate in the construction industry increased the most among industries as the demand for construction labor increased (Kirchberger, 2017). Similarly, Zhu, et al. (2021) reported that meteorological disasters, including floods, typhoons, droughts, and snow, increased wages in China between 2010 and 2018. Quantifying the spatiotemporal impact of disasters on reconstruction costs can enhance the accuracy of disaster loss assessments and inform more effective post-disaster recovery planning (Markhvida et al., 2020; Yabe, Zhang, and Ukkusuri, 2020).

Post-disaster demand surges in the construction industry have often been exacerbated by the significant regional labor market disruptions that follow major disasters (Ginn, 2022). Disasters often create an urgent need for construction workers, resulting in labor shortages that drive up wages (Pradhan and Arneson, 2021). Particularly, the availability of skilled labor is one of the major determinants of post-disaster construction cost inflation (Charles, Chang-Richards, and Yiu, 2022). Following Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005, the influx of federal recovery funds and insurance payouts spurred high demand for construction labor, but a lack of local skilled workers led to significant wage inflation (Groen, Kutzbach, and Polivka, 2020). In addition, workforce migration patterns influence labor supply, as workers move to unaffected regions, exacerbating shortages in disaster-affected areas (Agarwal Goel et al., 2024). For example, after Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans in August 2005, more than 100,000 residents moved to Houston, Texas (Davis et al., 2023). Döhrmann et al. (2021) found that post-disaster labor market distortions vary by geographic and economic conditions. Empirical research has also emphasized that the magnitude and duration of post-disaster construction demand depend on factors such as the severity of damage (Mushtaha et al., 2025), government intervention (Zhu et al., 2021), and insurance payouts (Wedawatta et al., 2023).

Previous research has analyzed the effects of disasters on the construction industry using a two-step approach: measurement and quantification (Ahmadi and Shahandashti, 2020; Arneson et al., 2020). Ahmadi and Shahandashti (2020) measured the labor wage changes and then applied spatial panel data models using the measured labor wage changes to capture spatial interactions in the post-disaster wage changes across counties. However, this two-step approach can amplify errors or bias, increasing the complexity of the model specification (Vella and Verbeek, 1999). Moreover, Ahmadi and Shahandashti (2020) omitted missing data in the spatial analysis instead of imputing the missing values. Therefore, they consequently ignored many spatial relationships and complexities arising from the missing data (Buuren, 2018). The majority of disaster research has emphasized the static impact of disasters on the construction industry during the recovery phase. However, disaster recovery is a dynamic process that evolves over time, involving interactions with surrounding communities and broader economic market conditions both spatially and temporally. The lack of spatiotemporal analysis on the dynamic effects of a disaster on construction wages can challenge reconstruction engineers, policymakers, and disaster mitigation agencies to understand the spatiotemporal dynamics of post-disaster demand surges for construction labor and develop comprehensive disaster management and recovery plans.

This study employed spatiotemporal econometric models to analyze the dynamic impact of disasters on construction wages in the Gulf Coast states from 2015 to 2019. It utilized quarterly data spanning from the first quarter of 2015 to the fourth quarter of 2019 to isolate the effects of natural disasters on construction wages. While the 5-year data from 2020 to 2024 are available, the observed fluctuations in construction wages during the pandemic and subsequent economic recession may not be primarily attributed to weather-related disasters or shocks. Therefore, our primary analysis of the effects of weather-related disasters on post-disaster construction wages focuses on pre-pandemic years.

The research utilized fixed-effects spatial Durbin models with a difference-in-differences (DID) specification to assess the spatiotemporal effects on construction wages in a single framework. The DID approach examines these effects by comparing changes in average wages before and after the disaster in affected counties (treatment group) with those in unaffected counties (control group). Simultaneously, it accounts for time-invariant, county-specific factors, common influences, and spatial interactions involving the dependent variable, independent variables, and error terms (Hansen, 2022). In doing so, it is found that the wages of the disaster-affected counties (treatment group) depend on their own disaster experience (direct effect of treatment) and the neighboring counties’ disaster experience (indirect effect of treatment). Such analysis helps to accurately and reliably quantify the additional changes in wages resulting from both the direct and indirect impacts of disasters, assuming that both the treatment and control groups follow a similar trend (Imai and Kim, 2021).

To the best of our knowledge, this research is the first attempt to quantify the direct, indirect, and total spatiotemporal lag effects of disasters on construction labor wages. By employing spatial Durbin models with spatial lags and weight matrices, this study accounts for the dynamic interactions between disaster-affected regions and their neighboring areas over time. This approach allows us to quantify how wage increases in one region can spill over and influence wage patterns in adjacent regions, capturing the full extent of the spatial and temporal dynamics that traditional models may overlook (Elhorst, 2014). In addition to addressing spatial dependencies, the research method also controls for a range of endogenous and exogenous factors that could potentially bias the results. Using a DID specification, we controlled for time-varying factors such as national economic conditions and other external shocks, isolating and estimating the specific effects of disasters on post-disaster construction labor wages.

Methodology

Data collection

Construction industry variables: The magnitude of the demand surge has been estimated by the amount of post-disaster increases in reconstruction costs, such as labor wages and material costs, compared to the pre-disaster level (Olsen and Porter, 2011; Pradhan and Arneson, 2021; Kim and Shahandashti, 2022b; Kim, Shahandashti, and Yasar, 2023a). Construction wage inflation is a driving factor that increases construction costs after a disaster, highlighting the demand surge phenomenon (Olsen and Porter, 2013; Chang-Richards et al., 2017; Kim, Chang, and Castro-Lacouture, 2020). Construction wages vary more widely than material costs in post-disaster situations due to factors like annual labor agreements and relocation expenses (Olsen and Porter, 2013; Kim and Shahandashti, 2022a). Therefore, the average weekly wages in the construction industry were selected as a dependent variable for spatiotemporal analysis to estimate the effects of disasters on construction wages.

Construction wages can be impacted by various factors beyond the extent of post-disaster reconstruction demand growth. For instance, supply chain disruptions due to damaged infrastructure, transportation networks, and manufacturing facilities can lead to logistical challenges, higher transportation costs, and longer lead times, further escalating construction expenses. Regulatory and policy changes, such as anti-price gouging laws (Kim, Shahandashti, and Yasar, 2023a) and federal motor carrier safety regulation waivers (Kim, Shahandashti, and Yasar, 2023b), also play a critical role in post-disaster construction costs. Moreover, broader macroeconomic conditions, such as inflation, interest rates, and fluctuations in material and labor prices, can impact reconstruction expenses regardless of the disaster. (Kim and Shahandashti, 2022b; Castelblanco et al., 2025). If a disaster coincides with a period of economic downturn or supply chain disruptions at a national or global level, the cost of rebuilding may be significantly affected (Tang, Luo, and Walton, 2024).

To account for these confounding factors, we included other construction market variables, including the number of employees and the number of establishments in the construction industry, in the analysis (Busenbark et al., 2022). Additionally, the DID specification was implemented to accurately isolate and quantify the effects of disasters on construction costs while controlling for these confounding factors (Contat et al., 2024). This statistical technique compares changes over time between affected and unaffected groups, allowing researchers to separate the specific effects of disasters from other external influences (Roth et al., 2023). By controlling for endogenous and exogenous factors, such as pre-existing economic conditions and regional labor market variations, the spatial Durbin models with DID specification ensure a more precise and reliable assessment of the effects of disasters on construction cost fluctuations (Zhao and Wang, 2022).

Moreover, in our spatial DID specification, we included the county fixed effects, which control for time-invariant unobserved factors (e.g., geographic features or institutional factors), and the time fixed effects, which control for any factors that vary from time to time but are common to all counties (e.g., business cycles). Including these county fixed and time fixed effects controls for various time-invariant or county-invariant confounding factors, both observed and unobserved. It is noteworthy that including time fixed effects will also control for any observed variables that only vary across time (e.g., inflation). Thus, when we include these fixed effects, we must not include such variables, as the coefficient on them will be meaningless (Imai and Kim, 2021). Similarly, when we include the county fixed effects, we must not include and try to quantify the impact of observed time-invariant county-level variables.

Furthermore, we focused on the time period between 2015 and 2019, deliberately excluding data from 2020 onward, to isolate and quantify the weather-related effects of disasters on construction costs without the confounding influence of pandemic-related supply chain disruptions (Janz, Gassmann, and Gayoso de Ervin, 2024). The COVID-19 pandemic broke out in early 2020 and led to unprecedented supply chain disruptions, labor shortages, and economic volatility that significantly affected construction costs worldwide (Kim, Makhmalbaf, and Shahandashti, 2024; Castelblanco et al., 2025). By focusing our study on the pre-pandemic years, we aimed to measure the effects of disasters on construction costs without the confounding impact of pandemic-related external global shocks (Janz, Gassmann, and Gayoso de Ervin, 2024).

Table 1 shows the data collection of construction industry variables. The employment and establishment count data were included in the analysis as control variables to control for their confounding effects on construction wages (Blanchflower and Oswald, 1995; Barth and Dale-Olsen, 2011; Green, Heywood, and Theodoropoulos, 2021).

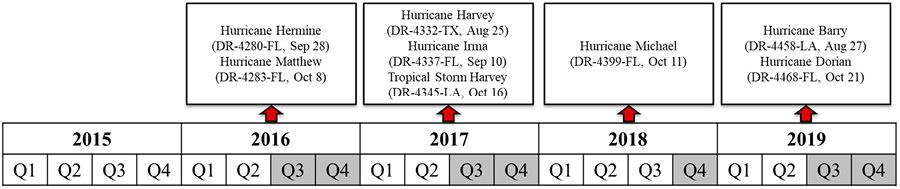

Disaster-related data: The independent dummy variable for representing a disaster occurrence was selected based on the major disasters declared by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Figure 1 describes all the major disaster declarations of hurricanes from 2015 to 2019 in three Gulf Coast states (Louisiana, Texas, and Florida) that are prone to hurricane strikes.

Figure 1. Major disaster declarations of hurricanes from 2015 to 2019 in the Gulf Coast states

Missing data handling

Data imputation methods have been implemented to resolve missing data problems in quantitative studies. The spatial multiple imputation was carried out in three sequential steps: (1) creating several complete sets by imputing plausible estimates to the missing observations, (2) analyzing the multiple complete datasets using a joint spatial distribution, and (3) aggregating the results from the multiple analyses.

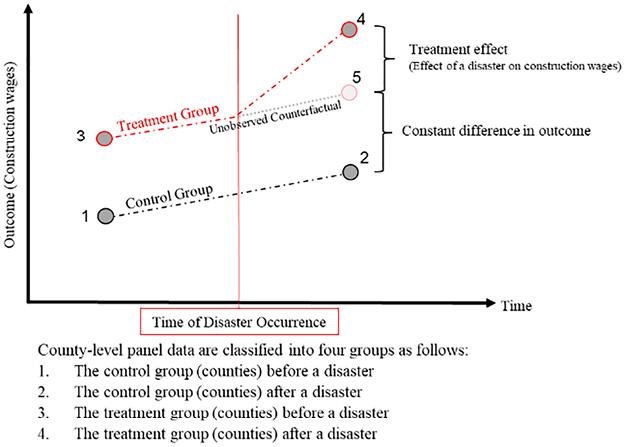

Difference-in-differences specification

The DID specification is widely used to estimate a treatment impact on an outcome variable by comparing the differences between the control and treatment groups before and after an intervention. Figure 2 illustrates the DID specification used in the current research.

Figure 2. Difference-in-differences specification

Spatial Durbin models with a difference-in-differences specification

The spatial Durbin models (SDMs) with a DID specification were developed to quantify the effects of disasters on construction costs. The SDM was chosen over other spatial econometric models because it effectively captures both the direct and spillover effects of disasters on construction costs (Zhao and Wang, 2022).

Unlike traditional regression models that assume spatial independence, the SDM accounts for spatial dependencies by incorporating both the spatial lag of the dependent variable and the spatially lagged independent variables (Nikolaou and Dimitriou, 2024). This is crucial in post-disaster construction markets, where cost increases are not confined to directly affected areas but often spread to neighboring regions due to factors such as material shortages, labor migration, and supply chain disruptions (Ahmadi and Shahandashti, 2020). By including spatial weight matrices and lags, the SDM allows us to measure how cost changes in one region influence cost variations in surrounding areas, providing a more comprehensive assessment of disaster-induced demand surges (Elhorst, 2014). Equation (1) presents the estimation model for examining the wage effect of disasters.

lnWAGEit = β0 + β1DISit + β2EMPit + β3ESTit + αi + αt + εit ,(1)

where WAGEit denotes the average weekly wage in the construction industry for county i at time t, and DISit denotes a binary indicator (dummy variable) set to one if county i experienced a hurricane declared as a major disaster by the FEMA at time t, and zero otherwise. EMPit denotes the number of employees in the construction industry in county i at time t, ESTit denotes the number of establishments in the construction industry in county i at time t, αi denotes the vector of the unobservable time-invariant fixed effects specific to each county, αt denotes the vector of the unobservable county-invariant fixed effects specific to each time period, εit denotes the time-varying idiosyncratic error at time t, and DISit denotes a binary indicator (dummy variable) set to one if county i experienced a hurricane declared as a major disaster by the FEMA at time t, and zero otherwise. EMPit denotes the number of employees in the construction industry in county i at time t, ESTit denotes the number of establishments in the construction industry in county i at time t, αi denotes the vector of the unobservable time-invariant fixed effects specific to each county, αt denotes the vector of the unobservable county-invariant fixed effects specific to each time period, and εit denotes the time-varying idiosyncratic error.

There are likely endogenous interaction effects between the counties’ dependent variables, exogenous interactions between the explanatory variables of interest, and interaction effects among the error terms (Elhorst, 2014). Thus, to incorporate these spatial dependencies, the dynamic SDM for Louisiana was used as presented by Equation (2):

lnWAGEit = β0 + τWAGEit–1 + φWijWAGEjt–1 + ρWijWAGEjt + β1DISit + β2EMPit + β3ESTit + δ1WijDISjt

+ δ2WijEMPjt + δ3WijESTjt + αi + αt + εit,(2)

i = 1, …, 64 and t = 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019,

where WAGEit is the average weekly wage in the construction industry in county i at time t, Wij is the 64 × 64 spatial weight matrix representing the queen contiguity relationships among the 64 counties in Louisiana, WAGEit–1 is the temporally lagged construction wage, WijWAGEjt–1 is the temporally and spatially lagged construction wages, WijWAGEjt is the spatially lagged construction wage, and DISit is a binary indicator (dummy variable) set to one if county i experienced a hurricane declared as a major disaster by the FEMA, and zero otherwise. EMPit is the number of employees in the construction industry in county i at time t, ESTit is the number of establishments in the construction industry in county i at time t, ρ is the spatial dependence parameter, αi is the vector of the unobservable time-invariant fixed effects specific to each county, αt is the vector of the unobservable county-invariant fixed effects specific to each time period, εit represents the time-varying idiosyncratic error, ρWijWAGEjt is the endogenous interaction effects, and δ1WijDISjt , δ2WijEMPjt , δ3WijESTjt are the exogenous interaction effects.

Disaster often has a lagged effect on the post-disaster construction industry (Capelle-Blancard and Laguna, 2010; Hallegatte et al., 2011; Higuchi et al., 2012; Naqvi and Rehm, 2014; Kajitani and Tatano, 2018). Thus, Equation (3) presents the dynamic SDM with a temporally lagged independent variable to examine the lagged effects of disasters on the county-level construction wages one quarter after the disasters occurred:

lnWAGEit = β0 + τWAGEit–1 + φWijWAGEjt–1 + ρWijWAGEjt + β1DISit–1 + β2DISit + β3EMPit

+ β4ESTit + δ1Wij l.DISjt + δ2Wij DISjt + δ3Wij EMPjt + δ4Wij ESTjt + αi + αt + εit ,(3)

i = 1, …, 64 and t = 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019,

where WAGEit is the average weekly wages in the construction industry in county i at time t, Wij is the 64 × 64 spatial weight matrix representing the queen contiguity relationships among the 64 counties in Louisiana, WAGEit–1 is the temporally lagged construction wages, WijWAGEjt–1 is the temporally and spatially lagged construction wages, WijWAGEjt is the spatially lagged construction wages, and DISit–1 is the temporally lagged disaster binary indicator (dummy variable) set to one if county i at time t − 1 experienced a hurricane declared as a major disaster by the FEMA, and zero otherwise. DISit is a binary indicator (dummy variable) set to one if county i at time t experienced a hurricane declared as a major disaster by the FEMA, and zero otherwise. EMPit is the number of employees in the construction industry in county i at time t, ESTit is the number of establishments in the construction industry in county i at time t, ρ is the spatial dependence parameter, αi is the vector of the unobservable time-invariant fixed effects specific to each county, αt is the vector of the unobservable county-invariant fixed effects specific to each time period, εit represents the time-varying idiosyncratic error, ρWijWAGEjt is the endogenous interaction effects, and δ1Wij l.DISjt , δ2Wij DISjt , δ3Wij EMPjt , and δ4Wij ESTjt are the exogenous interaction effects.

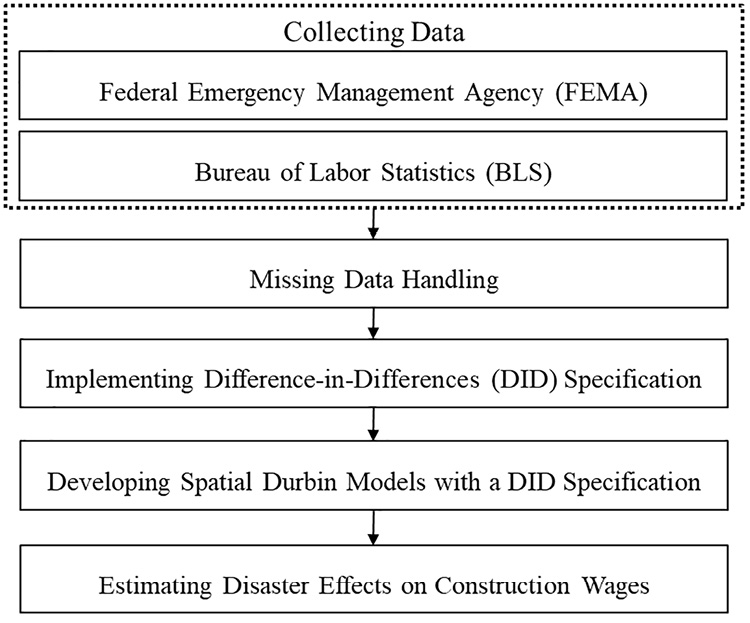

Figure 3 illustrates the research methodology, outlining the key steps involved in the analysis. It illustrates the process from data collection to the development of spatial Durbin models with a DID specification, highlighting how feedback and spillover effects across counties were accounted for in assessing the impact of disasters on construction wages.

Figure 3. Research methodology

Results

Results of linear fixed-effects models

Table 2 presents the results from estimating Equation (1) using linear fixed-effects models, both with and without imputing the missing data through spatial multiple imputation methods.

Notes: Robust standard errors in parentheses.

*** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, and * p < 0.1.

The disaster led to a 4% decrease in construction wages in the counties affected by the disaster compared to those unaffected, according to the imputed Louisiana dataset. When analyzing the Louisiana dataset without imputation, the disaster resulted in a 5% decrease in construction wages. The effect of disasters on construction wages in the quarter when the disaster occurred (hereafter, the disaster quarter) is not statistically significant in Texas and Florida. The significantly positive relationship between employment and wages in the construction industry holds for counties in all three Gulf Coast states. These findings align with the results of prior research studies (Blanchflower and Oswald, 1995; Barth and Dale-Olsen, 2011; Green, Heywood, and Theodoropoulos, 2021).

Results of spatial Durbin models

Table 3 presents the results of spatial Durbin fixed-effects models.

Notes: Robust standard errors in parentheses.

*** p < 0.01 and ** p < 0.05.

The effect of a disaster on construction wages in the disaster quarter was estimated to be negative at the 5% significance level based on the imputed panel datasets of Louisiana and Texas. The construction wages in the Louisiana counties struck by a disaster (i.e., disaster-affected counties) were estimated to be 4% lower than those in the non-disaster-affected counties in Louisiana. Similarly, the construction wages in the disaster-affected counties in Texas were measured as 3% lower than the wages in the non-disaster-affected counties in Texas. However, such an effect was not significant, both statistically and economically, for the counties in Florida.

A disaster’s direct, indirect, and total effects on the construction wage were investigated using fixed-effects dynamic SDMs in Table 4.

Notes: Robust standard errors in parentheses.

SR, short-run effects; LR, long-run effects.

*** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, and * p < 0.1.

The main effect of disasters on construction wages in the Louisiana panel dataset was estimated to be −4.02%. In other words, the construction wages in disaster-affected counties in Louisiana were 4.02% lower than the wages in non-disaster-affected counties in Louisiana. This negative effect of a disaster on construction wages can be attributed to the short-run direct effect of −3.69%, the short-run indirect effect of 8.23%, the long-run direct effect of −5.06%, and the long-run indirect effect of 13%. The Louisiana counties’ construction wages decreased by 3.69% in the short run and by 5.06% in the long run in the quarter when the county experienced a disaster. However, the Louisiana counties’ construction wages increased by 8.23% in the short run and by 13% in the long run in the quarter when the county’s neighboring county experienced a disaster. In short, the Louisiana counties’ own disaster experience (direct effect of treatment) decreased the construction wages in the disaster-affected Louisiana counties, while the neighboring counties’ disaster experience (indirect effect of treatment) increased the construction wages in the counties. Additionally, the findings indicate that the long-term impact on Louisiana counties is greater than the short-term effect. This indicates that the effects of disasters on construction wages, including direct and indirect effects, can be magnified in the long run.

The construction wages in disaster-affected counties in Texas were 2.59% lower than those in non-disaster-affected counties. The main effects of disasters of −2.59% in Texas can be attributed to the short-run direct effect of −2.68% and the long-run direct effect of −4.52%. The direct effect of a disaster on construction wages in the disaster-affected Texas counties was estimated to be negative. This negative direct effect of a disaster, which was consistently reported in both Louisiana and Texas, is probably due to the local market system crashing immediately after a disaster (Capelle-Blancard and Laguna, 2010; Hallegatte et al., 2011; Higuchi et al., 2012; Naqvi and Rehm, 2014; Kajitani and Tatano, 2018). However, the indirect effect of a disaster on construction wages in Louisiana counties was found to be statistically significantly positive. A disaster’s positive indirect effect indicates that the Louisiana counties’ construction wages increase when a disaster strikes their neighboring counties. This result seems plausible because the post-disaster surge in construction labor demand can be met by construction labor supply from the adjacent counties, inflating the construction wages in the neighboring disaster-affected county (Sadri et al., 2018). The main effect of a disaster on construction wages was not found statistically significant in the Florida counties.

Results of the spatial Durbin models with lagged disaster variables

The SDMs incorporating lagged disaster variables were constructed to investigate the delayed spatiotemporal impacts of disasters on construction wages, taking into account spatial interactions and dependencies between counties. Table 5 presents the results of the SDMs with the first-lagged disaster variable.

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses.

SR, short-run effects; LR, long-run effects.

*** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, and * p < 0.1.

While the disaster variable has a negative or insignificant effect on construction wages in three Gulf Coast states, the first-lagged disaster variable consistently demonstrates a statistically significant positive impact on wages. The disaster decreased the construction wages in the disaster quarter by 3.38% but increased the wages by 4.69% one quarter after the disaster in Louisiana. This lagged effect of a disaster on construction wage inflation is attributed to 3.96% of short-run direct effects, −16% of short-run indirect effects, 5% of long-run direct effects, and −23.1% of long-run indirect effects in Louisiana. The construction wage inflation one quarter after the disaster in Louisiana was influenced by both the positive direct effect of a disaster that occurred in a disaster-affected county and the negative indirect effect of a disaster that occurred in the adjacent counties in the short run and long run.

The lagged effect of a disaster on construction wage inflation was also reported consistently in the other two states, Texas and Florida. A disaster decreased the construction wages in the disaster quarter by 2.26% but increased the wages by 4.41% one quarter after the disaster in Texas. In Florida, a disaster did not significantly affect the wages in the disaster quarter but increased the construction wages by 1.79% one quarter after the disaster. A disaster’s direct and indirect effects were also found to positively influence construction wage inflation one quarter after the disaster in Texas and Florida.

Table 6 presents the results of the SDMs with the second-lagged disaster variable. The spatiotemporal analysis using the SDMs with the second-lagged disaster variable provides mixed results for estimating the effect of disasters on construction wages two quarters after the disaster.

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses.

SR, short-run effects; LR, long-run effects.

*** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, and * p < 0.1.

Table 7 presents the results of the SDMs with the third-lagged disaster variable. The SDMs with the third-lagged disaster variable were implemented for the spatiotemporal analysis to examine the effect of disasters on construction wages three quarters after the disaster. The disaster variable has a negative or insignificant effect on construction wages in the three Gulf Coast states in the disaster quarter. The third-lagged disaster variable shows an insignificant effect on wages in all three states. It can be implied that a disaster occurrence does not have a statistically significant impact on the construction wages three quarters after the disaster in Louisiana, Texas, and Florida.

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses.

SR, short-run effects; LR, long-run effects.

*** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, and * p < 0.1.

Discussions

This study examined the spatiotemporal impact of a disaster on construction wages across three Gulf Coast states to quantify how demand surges influence the post-disaster labor market. The findings revealed that the spatiotemporal impact on wages evolved over time following the disaster. In the immediate aftermath, during the quarter when the disaster hit, the effect on construction wages in affected communities was either negative or not statistically significant. However, the disaster increased construction wages one quarter after the disaster in all three Gulf Coast states. The effects of disasters on wages two quarters after the disaster were found to be negative or insignificant, varying across states. Three quarters after the disaster, there was no statistically significant impact on construction wages. This delayed positive impact of a disaster on wage inflation is consistent with the results found in earlier research. Kajitani and Tatano (2018) reported that price increases occurred 4 months after the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011. In a case study on Copenhagen, the storm surge immediately devastated the production capacity of the overall economic system, and the number of construction jobs started to increase 3 months after the storm (Hallegatte et al., 2011).

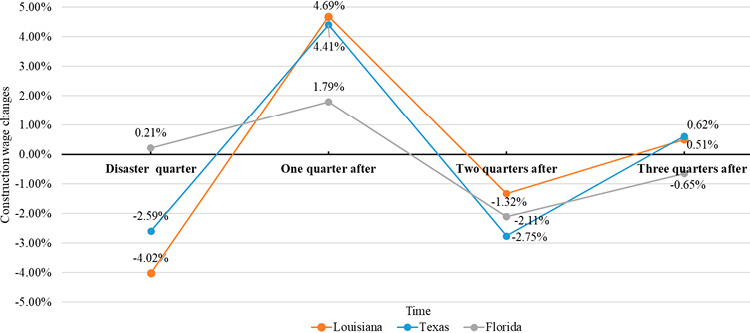

Table 8 summarizes the effects of disasters on construction wages over time in Louisiana, Texas, and Florida. The construction wages one quarter after the disaster in the disaster-affected counties were higher than the wages in the non-disaster-affected counties by 4.41%, 4.69%, and 1.79% in Louisiana, Texas, and Florida, respectively.

Notes: *** p < 0.01 and ** p < 0.05.

Figure 4 illustrates a consistent pattern of spatiotemporal dynamic effects of a disaster on construction wages in Louisiana, Texas, and Florida. In all three states, construction wages increased one quarter after the disaster. However, the effects of disasters on wages became insignificant three quarters after the disaster, implying that the post-disaster construction wages were no longer statistically significantly affected by the disaster (Lima and Barbosa, 2019).

Figure 4. The spatiotemporal dynamic effects of a disaster on construction wages

The spatiotemporal analysis, using dynamic SDMs, leverages spatial relationships among counties to estimate both short-term and long-term direct and indirect impacts of a disaster on construction wages. In Louisiana, one quarter after the disaster, construction wages in affected counties were 4.69% higher than those in unaffected counties. While the disaster’s direct impact in Louisiana led to an increase in construction wages one quarter after the event, its indirect impact resulted in a wage decrease in both the short term and the long term. This indicates that a disaster occurring in a specific Louisiana county i directly raised construction wages within that county, but if the disaster occurred in an adjacent county j, it led to a decrease in construction wages in county i one quarter after the disaster. This negative indirect effect of a disaster has been discussed in previous studies (Belasen and Polachek, 2009; Kellenberg and Mobarak, 2011; Hornbeck and Keniston, 2017; Zeenat Fouzia, Mu, and Chen, 2020; Tran and Wilson, 2022). Belasen and Polachek (2009) reported that the earnings in the neighboring counties of the disaster-affected counties decreased by 4.51% compared with the earnings in the directly affected counties due to the influx of workers to the neighboring counties from the affected counties. The long-run disaster impact on income per capita was estimated to be positive in the disaster-affected areas and negative in the broader region (Tran and Wilson, 2022).

The construction wage inflation one quarter after the disaster in the disaster-affected counties of Texas and Florida was attributed to the positive direct and indirect impacts observed in both the short term and the long term. The disaster increased the construction wages not only in the disaster-affected counties but also in the neighboring counties of the disaster-affected counties one quarter after the disaster. The positive direct and indirect effects of a disaster on wages align with the previous findings in disaster studies (Fu and Gregory, 2019; Zeenat Fouzia, Mu, and Chen, 2020; Tran and Wilson, 2022). The demand surge for post-disaster construction resources inflates the prices of reconstruction resources not only in the disaster-affected counties but also in the neighboring counties of the disaster-affected counties (Ahmadi and Shahandashti, 2020).

The findings of this study have several important practical implications for post-disaster recovery efforts, labor market planning, and construction cost management. Understanding the delayed impact of disasters on construction wages can help policymakers, contractors, and government agencies anticipate and address workforce shortages, labor cost inflation, and project delays more effectively.

One key implication is the potential for project delays due to the temporary stagnation or decline in wages in the immediate aftermath of a disaster. The results suggest that while disasters disrupt the labor market initially, by displacing workers, causing temporary job losses, or creating uncertainty in reconstruction efforts (Kim and Shahandashti, 2022a), wage increases do not occur until one quarter after the event. This lag in wage growth may indicate a period where construction activity is slower than expected due to difficulties in mobilizing resources, permitting delays, or uncertainty in funding for reconstruction projects. As found in previous studies on Japan and Denmark, post-disaster economic disruptions often take several months before construction employment and wages start rising (Hallegatte et al., 2011; Kajitani and Tatano, 2018).

From a cost estimation and budgeting perspective, these wage dynamics can significantly impact reconstruction costs (Kim, 2023). The increase in wages observed one quarter after a disaster suggests that contractors and developers should expect higher labor costs when bidding on projects in disaster-affected areas (Pradhan et al., 2023). For large-scale public and private rebuilding projects, failure to account for this delayed wage inflation may lead to underbudgeting, cost overruns, or project delays as labor becomes more expensive than initially projected (Kim, Abediniangerabi, and Shahandashti, 2021). Policymakers and funding agencies should consider adjusting financial assistance programs, subsidies, or wage stabilization policies to mitigate the financial burden on rebuilding efforts (Davlasheridze and Miao, 2021).

Furthermore, the study highlights the need for strategic workforce planning in disaster-prone regions. States and municipalities should consider policies that encourage the retention and rapid deployment of skilled labor in affected areas (Kim and Shahandashti, 2022a). For instance, state governments could offer temporary wage incentives or workforce training programs in anticipation of labor demand spikes. Additionally, construction firms could develop pre-disaster labor agreements or standby contracts to ensure that skilled workers are available immediately after a disaster, reducing delays in reconstruction efforts.

Finally, the spatial variations in wage impacts across Louisiana, Texas, and Florida indicate that disaster responses should be tailored to regional labor market conditions. The extent and duration of wage inflation may depend on factors such as the severity of damage, the availability of migrant labor, and the overall economic resilience of the affected region (Pradhan et al., 2023). Policymakers should consider implementing region-specific strategies to stabilize labor supply and prevent excessive wage inflation that could hinder equitable reconstruction efforts.

Conclusions

The disaster recovery process is highly associated with the post-disaster construction industry. Despite the significance of understanding the post-disaster construction industry to expedite the disaster recovery process, the effects of a disaster on construction wages have not been elucidated. Particularly, the spatiotemporal analysis of the effects of a disaster on construction wages is needed to clarify the endogenous and exogenous interaction effects between communities and enhance the understanding of the dynamic process of demand surge in the construction labor market. This study examined the short-term and long-term spatiotemporal dynamic impacts of a disaster on construction wages at the county level across three Gulf Coast states (Louisiana, Texas, and Florida) by utilizing dynamic SDMs with a DID framework.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the spatiotemporal dynamic effects of a disaster on construction wages by employing dynamic SDMs with DID specifications that enable us to examine the endogenous and exogenous multi-county interaction effects, controlling for the unobserved country heterogeneities at one stage. The dynamic SDMs with DID allowed us to quantify efficient and consistent estimates of the direct, indirect, and total impacts of a disaster on wages by comparing the changes in average construction wages before and after the disaster in affected counties (treatment group) with those in unaffected counties (control group). Simultaneously, the dynamic SDMs accounted for time-invariant county-specific factors, shared influences, and spatial dependencies in the dependent variable, exogenous variables, and error term.

Some caveats are noted to assist disaster recovery practitioners, reconstruction engineers, and disaster mitigation agencies in better understanding the post-disaster dynamics of construction wages and improving their reconstruction strategies and plans. First, the one quarter-lagged positive effect of a disaster on construction wages was consistently found in three Gulf Coast states, presenting recent empirical evidence to a line of disaster studies. It is recommended that disaster recovery practitioners take preemptive actions to increase the construction labor supply in response to the lagged demand surge that occurred one quarter after the disaster. Second, the lagged effect of a disaster on wage inflation was attributed to the direct and indirect effects of a disaster. Also, the endogenous spatial interaction effect of construction wages was positive in all three Gulf Coast states. The construction wages in county i are positively associated with the wages in the neighboring county j. These endogenous and exogenous spatial interaction effects between communities should be considered for planning and implementing an effective disaster recovery process.

Although the findings of this research provide detailed and practical insights into the spatiotemporal impacts of a disaster on construction wages, it is worthwhile to discuss the limitations of the research and suggest directions for future research. First, the results of this study are based on the hurricanes that occurred in the U.S. Gulf Coast states between 2015 and 2019. Various disaster types, regional industry compositions, and additional factors may lead to differing outcomes across disasters, regions, and time periods. Exploring whether the results of this study remain consistent in other post-disaster contexts would be a compelling area for future studies. Second, the indirect effects of a disaster on construction wages were found to be statistically significant but varied across the states. These variations may be influenced by a range of unobserved confounders, including government interventions and insurance policies, which were not fully accounted for in this study. For instance, the timing and scale of disaster relief programs, public spending on reconstruction, and local government wage subsidies could all affect the labor supply and the wages offered in affected areas. Similarly, insurance payouts may influence wage dynamics by affecting the speed and scope of reconstruction efforts. Disasters often trigger large-scale insurance settlements, which can create an influx of funds that drives up demand for construction workers and, consequently, wages. A promising avenue for future research would involve exploring the underlying factors that explain spatial variations in indirect or spillover effects and integrating those factors, such as government policies and insurance settlements, to better understand how these factors influence labor markets after a disaster. This would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the complex relationships between government actions, insurance coverage, and post-disaster wage fluctuations. Policymakers and reconstruction engineers could benefit from more granular insights into how construction labor market dynamics evolve over time following a disaster, which would allow for more effective recovery planning and reconstruction strategies. Despite the dataset ending in 2019, it is important to note that our findings remain highly relevant to current trends. The observed lagged effect of disasters on construction wages aligns with ongoing discussions about labor market resilience in the face of weather-related events (Basile et al., 2024; Demirci and Isik, 2024; Kukeli, 2025). The persistence of extreme weather events and their growing frequency due to climate change further highlight the importance of understanding these wage fluctuations.

While this study focused on pre-pandemic data, it can serve as a baseline for future research on the evolving impacts of disasters on construction wages in the context of the post-pandemic. Future research could expand upon our findings by incorporating post-2020 data to examine how the pandemic and more recent disasters have influenced construction wages. It would be interesting to examine whether the post-disaster cost inflation has been exacerbated in the post-pandemic era. Specifically, it would be important to explore whether the ongoing labor shortages and supply chain issues lead to even more pronounced wage increases in disaster-affected areas and how pandemic-related economic shocks have changed the trajectory of wage fluctuations after a disaster. Examining these research questions would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the evolving relationship between disasters and construction wages and offer valuable insights for policymakers and industry stakeholders as they manage recovery efforts in a post-pandemic world.

References

Agarwal Goel, P., Roy Chowdhury, J., Grover Sharma, C., & Parida, Y. (2024) Social Impacts of Disasters. In P. Agarwal Goel, J. Roy Chowdhury, C. Grover Sharma, & Y. Parida (Eds.), Economics of Natural Disasters (pp. 141–255). Springer Nature Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-7430-6_3

Ahmadi, N. and Shahandashti, M. (2020) ‘Characterizing Construction Demand Surge Using Spatial Panel Data Models’, Natural Hazards Review, 21(2), p. 04020008. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)NH.1527-6996.0000368

Arneson, E. et al. (2020) ‘Predicting Postdisaster Residential Housing Reconstruction Based on Market Resources’, Natural Hazards Review, 21(1), p. 04019010. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)NH.1527-6996.0000339

Barth, E. and Dale-Olsen, H. (2011) ‘Employer Size or Skill Group Size Effect on Wages?’, ILR Review, 64(2), pp. 341–355. https://doi.org/10.1177/001979391106400207

Basile, R., Giallonardo, L., Iapadre, P. L., Ladu, M. G., & Persio, R. (2024) The local labour market effects of earthquakes. Regional Studies, 58(1), 91–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2023.2187045

Belasen, A.R. and Polachek, S.W. (2009) ‘How Disasters Affect Local Labor Markets: The Effects of Hurricanes in Florida’, Journal of Human Resources, 44(1), pp. 251–276. https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.44.1.251

Blanchflower, D.G. and Oswald, A.J. (1995) ‘An Introduction to the Wage Curve’, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 9(3), pp. 153–167. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.9.3.153

Busenbark, J. R., Yoon, H. (Elle), Gamache, D. L., & Withers, M. C. (2022) Omitted Variable Bias: Examining Management Research With the Impact Threshold of a Confounding Variable (ITCV). Journal of Management, 48(1), 17–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/01492063211006458

Buuren, S. van (2018) Flexible Imputation of Missing Data, Second Edition. CRC Press.

Capelle-Blancard, G. and Laguna, M.-A. (2010) ‘How does the stock market respond to chemical disasters?’, Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 59(2), pp. 192–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2009.11.002

Castelblanco, G., Fenoaltea, E. M., De Marco, A., & Chiaia, B. (2025) Influence of macroeconomic factors on construction costs: An analysis of project cases. Construction Managemnt and Economics, 43(3), 196–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/01446193.2024.2410872

Chang-Richards, Y. et al. (2017) ‘Effects of a major disaster on skills shortages in the construction industry: Lessons learned from New Zealand’, Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 24(1), pp. 2–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/ECAM-03-2014-0044

Charles, S. H., Chang-Richards, A. Y., & Yiu, T. W. (2022) A systematic review of factors affecting post-disaster reconstruction projects resilience. International Journal of Disaster Resilience in the Built Environment, 13(1), 113–132. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJDRBE-10-2020-0109

Contat, J. C., Doerner, W. M., Renner, R. N., & Rogers, M. J. (2024) Measuring Price Effects from Disasters Using Public Data: A Case Study of Hurricane Ian. Journal of Real Estate Research, 1–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/08965803.2024.2391213

Davis, C., Elliot, D., Teles, D., Theodos, B., & Thomas, K. (2023) Labor Markets in Climate Migrant Receiving Communities. https://search.issuelab.org/resources/43675/43675.pdf

Davlasheridze, M., & Miao, Q. (2021) Does post-disaster aid promote community resilience? Evidence from federal disaster programs. Natural Hazards, 109(1), 63–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-021-04826-2

Demirci, F. S., & Isik, Z. (2024) Developing a community responsive resilient contractor selection model for post-disaster reconstruction projects: A build back better approach. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management. https://doi.org/10.1108/ECAM-06-2024-0802

Döhrmann, D., Gürtler, M., Hibbeln, M., & Metzler, R. (2021) Arising from the Ruins: The impact of natural disasters on reconstruction labor wages. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 59, 102210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102210

Elhorst, J.P. (2014) ‘Spatial Panel Data Models’, in Elhorst, J. P., Spatial Econometrics. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg (SpringerBriefs in Regional Science), pp. 37–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-40340-8_3

Fu, C. and Gregory, J. (2019) ‘Estimation of an equilibrium model with externalities: Post‐disaster neighborhood rebuilding’, Econometrica, 87(2), pp. 387–421. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA14246

Ginn, W. (2022) Climate Disasters and the Macroeconomy: Does State-Dependence Matter? Evidence for the US. Economics of Disasters and Climate Change, 6(1), 141–161. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41885-021-00102-6

Green, C.P., Heywood, J.S. and Theodoropoulos, N. (2021) ‘Hierarchy and the Employer Size Effect on Wages: Evidence from Britain’, Economica, 88(351), pp. 671–696. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecca.12364

Groen, J. A., Kutzbach, M. J., & Polivka, A. E. (2020) Storms and Jobs: The Effect of Hurricanes on Individuals’ Employment and Earnings over the Long Term. Journal of Labor Economics, 38(3), 653–685. https://doi.org/10.1086/706055

Hallegatte, S. et al. (2011) ‘Assessing climate change impacts, sea level rise and storm surge risk in port cities: a case study on Copenhagen’, Climatic Change, 104(1), pp. 113–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-010-9978-3

Hansen, B. (2022) Econometrics. Princeton University Press. Available at: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=UipXEAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=time+series+econometrics&ots=jDcIrpfdhD&sig=RS0s28js9Dfj39dwybGRsfRQ1eM (Accessed: 14 November 2024).

Higuchi, Y. et al. (2012) ‘The impact of the Great East Japan Earthquake on the labor market—need to resolve the employment mismatch in the disaster-stricken areas’, Japan Labor Review, 9(4), pp. 4–21.

Hornbeck, R. and Keniston, D. (2017) ‘Creative Destruction: Barriers to Urban Growth and the Great Boston Fire of 1872’, American Economic Review, 107(6), pp. 1365–1398. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20141707

Imai, K. and Kim, I.S. (2021) ‘On the use of two-way fixed effects regression models for causal inference with panel data’, Political Analysis, 29(3), pp. 405–415. https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2020.33

Janz, T., Gassmann, F., & Gayoso de Ervin, L. (2024) Weathering Shocks Unraveling the Effects of Short-Term Weather Shocks on Poverty in Paraguay. World Economic Outlook. https://www.imf.org/-/media/Files/Publications/WEO/2021/October/English/text.pdf. https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-10970

Kajitani, Y. and Tatano, H. (2018) ‘Applicability of a spatial computable general equilibrium model to assess the short-term economic impact of natural disasters’, Economic Systems Research, 30(3), pp. 289–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/09535314.2017.1369010

Kellenberg, D. and Mobarak, A.M. (2011) ‘The Economics of Natural Disasters’, Annual Review of Resource Economics, 3(1), pp. 297–312. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-resource-073009-104211

Khodahemmati, N. and Shahandashti, M. (2020) ‘Diagnosis and Quantification of Postdisaster Construction Material Cost Fluctuations’, Natural Hazards Review, 21(3), p. 04020019. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)NH.1527-6996.0000381

Kim, S. et al. (2022) ‘Improving Accuracy in Predicting City-Level Construction Cost Indices by Combining Linear ARIMA and Nonlinear ANNs’, Journal of Management in Engineering, 38(2), p. 04021093. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0001008

Kim, S. (2023) Disaster Management and Recovery: Estimating the Disaster Impacts on Construction Costs and Evaluating the Policy Effects on Disaster Recovery. https://doi.org/10.1061/NHREFO.NHENG-1865

Kim, S., Chang, S. and Castro-Lacouture, D. (2020) ‘Dynamic Modeling for Analyzing Impacts of Skilled Labor Shortage on Construction Project Management’, Journal of Management in Engineering, 36(1), p. 04019035. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0000720

Kim, S., Makhmalbaf, A., & Shahandashti, M. (2024) Diagnosing and quantifying post-COVID-19 fluctuations in the architecture billings indices. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 31(2), 681–695. https://doi.org/10.1108/ECAM-05-2022-0500

Kim, S. and Shahandashti, M. (2022a) ‘Characterizing relationship between demand surge and post-disaster reconstruction capacity considering poverty rates’, International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 76, p. 103014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2022.103014

Kim, S. and Shahandashti, M. (2022b) ‘Diagnosing and Quantifying Post-Disaster Pipe Material Cost Fluctuations’, in Pipelines 2022. Pipelines 2022, Indianapolis, Indiana: American Society of Civil Engineers, pp. 185–195. https://doi.org/10.1061/9780784484296.022

Kim, S., Shahandashti, M., & Yasar, M. (2023) Effect of anti-price gouging law on postdisaster recovery speed: Evidence from reconstruction in Virginia and Maryland after Hurricane Sandy. Natural Hazards Review, 24(4), 04023045.

Kirchberger, M. (2017) ‘Natural disasters and labor markets’, Journal of Development Economics, 125, pp. 40–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2016.11.002

Kukeli, A. (2025) The effects and the macroeconomic dynamics of natural disaster damages: Investigation of local evidence. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 12(1), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2025.2452524

Li, H. et al. (2022) ‘A dynamic disastrous CGE model to optimize resource allocation in post-disaster economic recovery: post-typhoon in an urban agglomeration area, China’, Environmental Research Letters, 17(7), p. 074027. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ac7733

Lima, R.C. de A. and Barbosa, A.V.B. (2019) ‘Natural disasters, economic growth and spatial spillovers: Evidence from a flash flood in Brazil’, Papers in Regional Science, 98(2), pp. 905–924. https://doi.org/10.1111/pirs.12380

Markhvida, M. et al. (2020) ‘Quantification of disaster impacts through household well-being losses’, Nature Sustainability, 3(7), pp. 538–547. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-020-0508-7

McEntire, D.A. (2021) Disaster response and recovery: strategies and tactics for resilience. John Wiley & Sons.

Mushtaha, A. W., Alaloul, W. S., Baarimah, A. O., Musarat, M. A., Alzubi, K. M., & Khan, A. M. (2025) A decision-making framework for prioritizing reconstruction projects in post-disaster recovery. Results in Engineering, 25, 103693. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2024.103693

Naqvi, A.A. and Rehm, M. (2014) ‘A multi-agent model of a low income economy: simulating the distributional effects of natural disasters’, Journal of Economic Interaction and Coordination, 9(2), pp. 275–309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11403-014-0137-1

Nikolaou, P., & Dimitriou, L. (2024) Spillover effects in transit networks: A parameterized weight matrix spatial lagged approach. Journal of Urban Mobility, 6, 100081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urbmob.2024.100081

Olsen, A.H. and Porter, K.A. (2011) ‘On the contribution of reconstruction labor wages and material prices to demand surge’, Structural Engineering & Structural Mechanics Report Series, 81. Available at: https://www.sparisk.com/pubs/Olsen-2011-SESM-Demand-Surge.pdf (Accessed: 14 November 2024).

Olsen, A.H. and Porter, K.A. (2013) ‘Storm Surge to Demand Surge: Exploratory Study of Hurricanes, Labor Wages, and Material Prices’, Natural Hazards Review, 14(4), pp. 247–257. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)NH.1527-6996.0000111

Pradhan, S. and Arneson, E. (2021) ‘Postdisaster Labor-Demand Surge in the US Highways, Roads, and Bridges Construction Sector’, Journal of Management in Engineering, 37(1), p. 04020102. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0000869

Pradhan, S. et al. (2023) How Construction and Socioeconomic Resource Availability Affected Housing Recovery after Hurricane Sandy. Natural Hazards Review, 24(3), 05023004. https://doi.org/10.1061/NHREFO.NHENG-1703

Ripple, W.J. et al. (2024) ‘The 2024 state of the climate report: Perilous times on planet Earth’, BioScience, p. biae087. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biae087

Roth, J., Sant’Anna, P. H. C., Bilinski, A., & Poe, J. (2023) What’s trending in difference-in-differences? A synthesis of the recent econometrics literature. Journal of Econometrics, 235(2), 2218–2244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2023.03.008

Sadri, A.M. et al. (2018) ‘The role of social capital, personal networks, and emergency responders in post-disaster recovery and resilience: a study of rural communities in Indiana’, Natural hazards, 90(3), pp. 1377–1406. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-017-3103-0

Smith, A.B. (2020) ‘U.S. Billion-dollar Weather and Climate Disasters, 1980 - present (NCEI Accession 0209268)’. NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information. https://doi.org/10.25921/STKW-7W73

Smith, A.B. (2024) 2023: A historic year of U.S. billion-dollar weather and climate disasters | NOAA Climate.gov. Available at: http://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/beyond-data/2023-historic-year-us-billion-dollar-weather-and-climate-disasters (Accessed: 28 June 2024).

Tang, T., Luo, T., & Walton, H. (2024) Resilience in complex disasters: Florida’s hurricane preparedness, response, and recovery amid COVID-19. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 102, 104298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2024.104298

Tran, B.R. and Wilson, D. (2022) ‘The local economic impact of natural disasters’, in. Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

Vella, F. and Verbeek, M. (1999) ‘Two-step estimation of panel data models with censored endogenous variables and selection bias’, Journal of Econometrics, 90(2), pp. 239–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4076(98)00043-8

Wedawatta, G., Wanigarathna, N., Vijekumara, P. A., & Tennakoon, M. (2023) Macro level insurance for financing post disaster recovery: The case of National Disaster Insurance Policy in Sri Lanka. Climate Economics and Finance, 1(1), 13–28.

Yabe, T., Zhang, Y. and Ukkusuri, S.V. (2020) ‘Quantifying the economic impact of disasters on businesses using human mobility data: a Bayesian causal inference approach’, EPJ Data Science, 9(1), p. 36. https://doi.org/10.1140/epjds/s13688-020-00255-6

Zeenat Fouzia, S., Mu, J. and Chen, Y. (2020) ‘Local labour market impacts of climate-related disasters: a demand-and-supply analysis’, Spatial Economic Analysis, 15(3), pp. 336–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/17421772.2019.1701699

Zhao, C., & Wang, B. (2022) How does new-type urbanization affect air pollution? Empirical evidence based on spatial spillover effect and spatial Durbin model. Environment International, 165, 107304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2022.107304

Zhou, B., Zhang, H. and Evans, R. (2022) ‘Build back better: a framework for sustainable recovery assessment’, International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 76, p. 102998. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2022.102998

Zhu, X. et al. (2021) ‘How meteorological disasters affect the labor market? The moderating effect of government emergency response policy’, Natural Hazards, 107(3), pp. 2625–2640. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-021-04526-x