Construction Economics and Building

Vol. 25, No. 3/4

December 2025

RESEARCH ARTICLE

The Fourth Industrial Revolution Technologies and the Construction Industry in Ghana

Hayford Pittri1, Kofi Agyekum2, Burcu Salgin3,*, Annabel Morkporkpor Ami Dompey2, Rhoda Gasue2, Samuel Adjei Anderson2

1 Institute of Sustainable Built Environment, School of Energy, Geoscience, Infrastructure and Society, Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh, UK

2 Department of Construction Technology and Management, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana

3 Department of Architecture, Erciyes University, Kayseri, Türkiye

Corresponding author: Burcu Salgin, bsalgin@erciyes.edu.tr

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v25i3/4.9408

Article History: Received 22/10/2024; Revised 30/05/2025; Accepted 03/07/2025; Published 05/12/2025

Citation: Pittri, H., Agyekum, K., Salgin, B., Dompey, A. M. A., Gasue, R., Anderson, S. A. 2025. The Fourth Industrial Revolution Technologies and the Construction Industry in Ghana. Construction Economics and Building, 25:3/4, 231–253. https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v25i3/4.9408

Abstract

Given the Ghanaian construction industry’s continued reliance on conventional practices, understanding its readiness for digital transformation is essential to enhance productivity, efficiency, and competitiveness. This study investigates the level of awareness and extent of utilization of Industry 4.0 technologies within the Ghanaian construction industry (GCI). A quantitative approach was adopted using a structured questionnaire administered to 100 built environment professionals through convenience and snowball sampling. Descriptive and inferential statistical tools, including one-sample t-tests, independent samples t-tests, and analysis of variance (ANOVA), were used to analyze the data. The results revealed low overall awareness and utilization of Industry 4.0 technologies across the GCI. Drone technology showed the highest awareness and usage, while technologies such as 3D printing, artificial intelligence, and big data analytics recorded the lowest. Significant differences were observed in utilization based on respondents’ awareness, profession, and years of experience. This study fills a critical gap by providing baseline data necessary for understanding the sector’s digital maturity. The findings offer valuable insights for policymakers, industry stakeholders, and educators aiming to promote digital innovation. The study concludes that enhancing awareness through training, curriculum reforms, and supportive policies is vital for driving the digital transformation of the GCI.

Keywords

Industry 4.0 Technologies; Internet of Things; Building Information Modeling; Artificial Intelligence; Construction 4.0

Introduction

The fourth industrial revolution (4IR), also known as Industry 4.0, represents a paradigm shift in the integration of human, physical, and digital systems, unifying people, products, data, and machines to create smart, interconnected production environments. Unlike previous industrial revolutions, the pace of technological advancement under Industry 4.0 is unprecedented, reshaping everyday life and redefining how businesses operate across sectors (Bakar et al., 2024). From intelligent automation to real-time data analytics, this transformation is driving efficiency, customization, and innovation on a global scale (Aryal et al., 2023; Bakar et al., 2024).

The notion of “Construction 4.0” epitomizes the adoption of Industry 4.0 technologies in the construction industry, where information and digitital technologies are revolutionizing decision-making and management processes. This transformation is primarily driven by the potential for improving project performance and management (Perrier et al., 2020). Embracing advanced manufacturing and digital technologies not only enhances construction quality but also increases productivity and safety. It has been established that Construction 4.0 plays a pivotal role in streamlining operations within the construction industry (Aryal et al., 2023). A wide range of Construction 4.0 technologies—such as augmented reality, laser scanning, Building Information Modeling (BIM), the Internet of Things (IoT), wearable sensors, and automated equipment—are transforming the construction industry (Forcael et al., 2020). For instance, IoT-based safety systems have been shown to reduce on-site safety costs by up to 78% compared to conventional methods (Chung et al., 2020), while additive manufacturing enhances both energy efficiency and occupant comfort in buildings (Pessoa et al., 2021). Despite these advantages, only 6% of architecture, engineering, and construction firms currently adopt these technologies in most developing countries, largely due to entrenched reliance on traditional practices (You and Feng, 2020; Begic and Galic, 2021).

Maisiri and Van Dyk (2019) postulated that although noticeable progress has been made in the use of Industry 4.0 technologies, systems, and processes in developed countries, there is uncertainty about the preparedness of businesses and industries in developing countries to adopt Industry 4.0, and Ghana is not an exception. Given that emerging markets like Ghana’s can ill afford the inefficiencies often associated with traditional construction methods, leveraging Industry 4.0 technologies could usher in substantial improvements in both project quality and safety standards. Emerging research in nearby contexts, such as Nigeria, has shown that the awareness and implementation of Construction 4.0 technologies can significantly expedite construction processes and reduce costs, indicating a fruitful path for investigating similar technologies in Ghana (Opawole et al., 2022). Knowledge gained from examining successful case studies of technology utilization can be instrumental in breaking down the barriers identified in the Ghanaian construction industry (GCI), such as financial constraints and limited technological infrastructure (Bakar et al., 2024).

Oke et al. (2022) postulated that many construction practitioners are familiar with certain Industry 4.0 technologies but have not engaged with them effectively, which makes the evaluation of the level of awareness and understanding of such technologies among industry professionals crucial. This gap in utilization suggests a pressing need for further education and training tailored to Construction 4.0 technologies, which could potentially improve project outcomes in the GCI. Dosumu and Uwayo (2023) indicated that a lack of understanding regarding the impact of Construction 4.0 technologies, such as the IoT, on construction processes significantly hampers their adoption in developing economies. Hence, assessing the level of awareness and utilization of Industry 4.0 tools can illuminate the critical factors that influence their uptake, thereby facilitating targeted interventions to overcome identified barriers (Ibrahim et al., 2024). The socio-economic implications of embracing Construction 4.0 technologies extend beyond the construction industry; they hold the potential to impact the broader economic growth of the nation. The integration of advanced technological systems contributes to the country’s development goals by enhancing job creation, improving service delivery, and fostering innovation (Isayev, 2023). Thus, a comprehensive study on the awareness and utilization of these technologies is vital, as it can inform policymakers and industry leaders about the necessary steps to support the digital transition and ensure sustainable construction practices aligned with global standards.

The application of Industry 4.0 has not been adopted in many countries, especially developing economies; thus, studies on these technologies are narrow (Agyekum et al., 2018; Anitah et al., 2019; Manda and Dhaou, 2019). Despite the growing relevance of Industry 4.0, no empirical study has assessed the awareness and extent of its adoption within the GCI. Establishing baseline knowledge and utilization levels is essential for identifying critical gaps and informing targeted strategies to drive digital transformation. This study investigates the awareness and utilization of Construction 4.0 technologies within the GCI, offering insights to inform policy, research, and industry strategies for improved global competitiveness. Specifically, it addresses the following questions:

1. What is the level of awareness of Construction 4.0 technologies among construction professionals in the GCI?

2. To what extent are these technologies being utilized?

Literature review

Industry 4.0 technologies and the construction industry

Since its inception in 2011, Industry 4.0 has garnered increasing scholarly attention, with research highlighting its transformative potential across industries (Liao et al., 2017; Culot et al., 2020). The construction sector, characterized by its complexity and socio-economic significance (Williams et al., 2020; Paliwal et al., 2021), faces persistent challenges in meeting infrastructure demands while addressing inefficiencies tied to conventional practices (Li et al., 2019). Industry 4.0 technologies, collectively termed Construction 4.0, offer solutions by enhancing design, safety, automation, and sustainability (Bai et al., 2020; Begic and Galic, 2021). The United Nations Environment Programme underscores its role in mitigating environmental impacts through reduced waste and optimized workflows (IEA, 2018). Schönbeck et al. (2020) classified Construction 4.0 technologies into three domains: information and communication (e.g., BIM, IoT, cloud computing, and mixed reality), automation [e.g., artificial intelligence (AI), drones, sensors, and radio-frequency identification (RFID)], and industrialization (e.g., robotics and 3D printing). The benefits of integrating these tools in construction processes and practices are well-documented. BIM combined with the IoT creates digital twins for operational optimization (Shahzad et al., 2022), while AI and machine learning enhance scheduling, risk management, and data-driven decisions (Forcael et al., 2020; Abioye et al., 2021). Technologies like 3D printing and robotic systems offer automation, cost reduction, and safety improvements (Krupík, 2020; Tankova and da Silva, 2020). Augmented reality (AR) supports immersive safety training (Delgado et al., 2020; Babalola et al., 2023), and cloud computing facilitates scalable IT infrastructure with real-time data access, reducing costs and improving coordination (Lu and Cecil, 2016; Maqbool et al., 2023).

Similarly, the IoT enables real-time communication between devices, enhancing operational efficiency through machine-to-machine and human-to-machine interactions (Patel and Patel, 2016; Rghioui and Oumnad, 2017). Autonomous robots accelerate processes, reduce errors, and improve collaboration (Jayani Rajapathirana and Hui, 2018), while big data analytics enhances decision-making and performance by leveraging vast datasets from multiple construction inputs (Erboz, 2017; Wang and Hajli, 2017). RFID systems further optimize material tracking and supply chain logistics (Anitah et al., 2019).

Despite these opportunities, adoption remains limited in the construction sector due to cultural resistance, high costs, lack of expertise, and fragmented implementation strategies. A summary of some of the key Industry 4.0 technologies identified from the literature is presented in Table 1.

Source: Table created by authors.

Awareness of Industry 4.0 technologies in the construction industry

Research has linked numerous environmental and operational inefficiencies, such as global warming, pollution, excessive waste, project underperformance, and low labor productivity, to the persistent use of traditional construction methods (You and Feng, 2020; Pittri et al., 2025). These challenges have heightened global interest in digital solutions, thereby increasing awareness of Industry 4.0 technologies across various industrial sectors. Industry 4.0 has demonstrated transformative potential in enhancing operations in manufacturing, agriculture, international trade, and the built environment, including construction (Schwab and Davis, 2018; Bongomin et al., 2020). While sectors such as manufacturing and banking have integrated these technologies into their core operations (Oesterreich and Teuteberg, 2016), the construction industry is often characterized by slow technological uptake (Brous et al., 2020).

However, growing interest among construction professionals in adopting digital innovations suggests that a paradigm shift is underway (Kozlovska et al., 2021). Studies from countries such as Denmark, France, and South Korea have highlighted the practical applications of AI, additive manufacturing, and the IoT in construction (Attoue et al., 2018; Jo et al., 2019; Tankova and da Silva, 2020). A comparative study in Malaysia identified weak Industry 4.0 exposure among recent graduates and uneven familiarity among practitioners, underscoring the urgent need for enhanced education and training (Adepoju and Aigbavboa, 2021; Zabidin et al., 2024). These deficiencies often stem from limited practical experience, which hampers the transition to digital construction practices and slows innovation (Zabidin et al., 2024). Opawole et al. (2022) emphasized that awareness of 4IR technologies in Nigeria remains low, with limited practical engagement. In Ghana, efforts to integrate BIM–AR and simulation tools are emerging (Addy et al., 2023; Koranteng et al., 2023), although awareness remains low compared to developed regions (Newman et al., 2021; Pittri et al., 2025). Agyekum et al. (2022a) concluded that the awareness of 4IR technologies for health and safety management remains low, even though professionals are aware of the benefits they present. Pittri et al. (2024a) added that 4IR, such as drone technologies, have proven benefits for health and safety management, but their awareness and adoption remain low in the GCI, underscoring the need for educational reforms, capacity building, and training to align with the demands of a rapidly evolving construction ecosystem.

Utilization of Industry 4.0 technologies in the construction industry

Although awareness of 4IR is gradually improving, actual utilization in the construction industry, particularly in developing contexts, remains minimal. Despite growing recognition of the need for innovation, the actual utilization of Industry 4.0 technologies in the construction industry, such as BIM, IoT, and automation, remains limited (Ribeiro et al., 2022). This is largely due to entrenched reliance on traditional methods, high initial investment costs, lack of technical expertise, and resistance to change (Ribeiro et al., 2022). While the potential benefits of these technologies are well acknowledged, their operational application continues to lag, particularly in areas that could significantly improve project delivery, like the IoT and data analytics (Zabidin et al., 2024). Moreover, skepticism over return on investment and the inertia of conventional practices persist, often undermining government-led digitalization initiatives and placing firms at a disadvantage in an increasingly competitive, tech-driven construction environment (Venter et al., 2021). Research has indicated that developed countries have made significant strides in implementing technologies such as robotics, AI, big data analytics, and cloud computing (Maisiri and Van Dyk, 2019; Dhamija, 2022). In contrast, many developing economies—including Ghana, Nigeria, South Africa, and Kenya—struggle with issues such as technological readiness, infrastructure, and workforce capability, which limit full-scale adoption (Müller et al., 2018; Anitah et al., 2019).

Case studies from Kenya have shown that the application of Industry 4.0 technologies improves demand forecasting and decision-making, yet adoption rates remain low due to limited awareness (Anitah et al., 2019). Similarly, in the GCI, the actual deployment of technologies like the IoT, drones, and 3D printing is still in its infancy, hindered by financial constraints, limited technical skills, and resistance to change (Agyekum et al., 2022a; Pittri et al., 2024a). Gbolagade et al. (2022) emphasized that entrepreneurs who have embraced these technologies report significant performance improvements, reinforcing the need for broader industry-wide digital transition. To bridge the gap between awareness and practical application, stakeholders must invest in implementation frameworks, workforce upskilling, and supportive policy instruments to accelerate the integration of Industry 4.0 in construction (Maskuriy et al., 2019; Pittri et al., 2024a).

Methodology

Survey strategy/approach

This study examined the awareness and utilization of Construction 4.0 technologies within the GCI using a quantitative research approach. This methodology was appropriate, as it facilitated the use of structured questionnaires and statistical tools such as descriptive analysis and hypothesis testing to assess the relationships between key variables (Agyekum et al., 2022a). The questionnaire survey offered a systematic and efficient means of collecting data from a broad sample of construction professionals, enabling a comprehensive analysis of perceptions and practices. Furthermore, the structured nature of the survey supported the empirical testing of the study’s hypotheses, as presented in the subsequent section.

Survey design and administration

Following a review of the pertinent literature, a questionnaire was prepared to gather data from construction professionals in the GCI. Prior to data collection, a two-stage pilot testing process was undertaken to ensure the validity and reliability of the questionnaire. Validity in this context refers to the extent to which the instrument accurately captures the constructs it is designed to measure (Agyekum et al., 2023a). This process was essential for enhancing the accuracy of the study’s findings and the robustness of the conclusions drawn (Agyekum et al., 2022b). In the first stage, the questionnaire was reviewed by an expert in Industry 4.0 research to assess its content relevance and clarity. Following this, a pilot test was conducted with 10 purposively selected construction professionals from diverse built environment disciplines who possessed experience with Industry 4.0 technologies. Their feedback was instrumental in confirming the feasibility and comprehensibility of the questionnaire items, ensuring that the instrument was appropriately aligned with the study’s objectives. After a few clarifications and grammatical corrections, both phases of piloting were approved. The respondents were given the final version of the questionnaires online using Google Forms. This form of data collection was deemed sufficient since, unlike other methods like face-to-face communication, it guarantees respondents’ anonymity, and the respondents can complete the form at their convenience, reducing the need for scheduling meetings or face-to-face interviews. It is also more cost-effective and often comes with built-in data analysis tools that can help one quickly and easily generate reports and insights from the collected data (Agyekum et al., 2022a; Botchway et al., 2023a).

Respondents were required to reveal their background information in the first section of the questionnaire. This included their profession, years of experience, and the highest level of education. From the literature review and questionnaire piloting, 10 technologies under Industry 4.0 were revealed to be utilized in the GCI. In the second part of the survey, respondents were asked to rate their familiarity with these technologies on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = highly unaware, 2 = not aware, 3 = moderately aware, 4 = aware, and 5 = highly aware). Subsequently, the third section sought information on utilizing Industry 4.0 technologies in the GCI. Respondents were required to indicate their level of usage of the technologies on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not used, 2 = least used, 3 = moderately used, 4 = used, and 5 = highly used).

The study’s population was construction professionals working in various built environment organizations in Ghana, irrespective of their familiarity with Industry 4.0 technologies. Even though there was a recognized sampling frame for some of the construction professionals, such as architects and engineers, a sampling frame for construction managers and quantity surveyors was difficult to produce due to a lack of a database for these professionals (Kumah et al., 2022; Botchway et al., 2023b; Pittri et al., 2024b). Given the challenge of determining the actual sampling frame, compounded by their diverse occupational profiles, geographic dispersion, and time constraints, the sample size was determined using Cochran’s formula, a method widely applied in research involving large or indeterminate populations. This approach has been adopted in similar regional studies (Oduro et al., 2024; Pittri et al., 2024a) to ensure statistical validity. Based on a 95% confidence level, 10% margin of error, and a conservative population proportion of 0.5, the minimum required sample size was calculated to be approximately 96 using Equation 1:

Equation 1

Equation 1

where n0 is the minimum required sample size. Z is the Z-score, which corresponds to the desired confidence level. For a 95% confidence level, the Z-score is 1.96. P is the estimated proportion of the population that has the attribute of interest (usually set to 0.5, as this maximizes the sample size). ‘e’ is the margin of error set at 10% to ensure higher accuracy of the survey and study results.

A total of 100 responses were collected using convenience and snowball sampling techniques. Convenience sampling enabled access through established networks, while snowball sampling extended outreach to harder-to-reach professionals, mitigating coverage bias. Although these approaches may introduce selection bias, safeguards such as targeting a cross-section of roles (e.g., architects, engineers, and contractors), achieving geographic spread, and applying eligibility screening (minimum 1 year of experience) helped enhance representativeness and data quality. The large sample size further offsets limitations by capturing broader perspectives across the industry. Exploratory studies in the same jurisdiction have used a similar approach, as it is nearly impossible to list the actual number of participants in this population (Kissi et al., 2023; Oduro et al., 2024; Pittri et al., 2024a).

Analyses of data

Following a thorough data assessment and verification for completeness in Microsoft Excel, the data were entered into IBM SPSS version 26 for statistical analysis. The data were retrieved, sorted, and coded systematically in preparation for analysis. The study employed a combination of descriptive and inferential statistical techniques to interpret the data. Descriptive statistics, including frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations, were used to summarize the central tendencies and distribution of the responses. Mean score ranking provided insight into the awareness of the variables under investigation, while the standard deviation assessed the extent of variability in the responses. Inferential statistics, including one-sample t-tests, independent samples t-tests, and one-way ANOVA, were applied to examine differences in perceptions and usage levels of Industry 4.0 technologies among different respondent groups, thereby enabling robust statistical inferences.

The data’s reliability (i.e., consistency of responses) from the filled-out questionnaires was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha. The alpha values for the GCI’s experts’ knowledge of Industry 4.0 technologies and the level of usage of these technologies were 0.936 and 0.931, respectively, suggesting the reliability of the data for the analysis.

The one-sample t-test is a statistical hypothesis test used to determine whether the mean of a single sample significantly differs from a predefined reference value. In this study, the one-sample t-test was employed to evaluate whether the mean scores for the usage of various Industry 4.0 technologies differed significantly from a test value of 3.50, which was selected to represent the threshold for moderate usage on a 5-point Likert scale. This analysis aimed to determine whether the technologies were being used above, below, or at an average level by construction professionals. The hypotheses for the test were formulated as follows: the null hypothesis (H01) posited that the sample mean is equal to the reference value (i.e., μ = 3.50), indicating no significant difference in usage. The alternative hypothesis (H1) suggested that the sample mean differs from 3.50, indicating a statistically significant deviation. The test was conducted at a 95% confidence level, with statistical significance established at p < 0.05. If the p-value was less than 0.05, H0 was rejected in favor of H1, indicating that the level of usage of a given technology was significantly different from the reference point. This analysis was crucial in identifying which Industry 4.0 technologies are underutilized or well-integrated in the GCI.

To assess differences in perceptions and usage patterns among groups of construction professionals, this study employed two key inferential statistical tools: the independent samples t-test and the one-way ANOVA. The independent samples t-test is used to compare the means of two independent groups to determine if a significant difference exists between them (Pittri et al., 2024b; Kotei-Martin et al., 2025). It was used in this study to evaluate whether there was a statistically significant difference in the level of Industry 4.0 technology utilization between respondents who reported awareness of the concept and those who did not (H02: there is no significant difference in the utilization of Industry 4.0 technologies between professionals who are aware and those who are not aware of the concept).

The one-way ANOVA, in contrast, is a statistical technique used to compare the means of two or more independent groups to determine whether there are statistically significant differences among them (Agyekum et al., 2023b; Kent State University, 2024). In the context of this study, the one-way ANOVA was applied to examine whether respondents’ professional background and years of experience significantly influenced their reported frequency of using Industry 4.0 technologies. This helped to identify whether particular demographic subgroups were more inclined to adopt these technologies, which has practical implications for training and policy targeting. Two hypotheses were set. (1) H03: There is no significant difference in the utilization of Industry 4.0 technologies based on respondents’ professional roles. (2) H04: There is no significant difference in the utilization of Industry 4.0 technologies based on years of experience. Both tests were conducted at a 95% confidence level, with statistical significance determined at p < 0.05. These analyses were essential in uncovering the underlying factors influencing the uptake of Industry 4.0 technologies across different categories of construction professionals.

Results

Demographic background

This section presents the demographic information of the respondents (Table 2). This section was expedient because the respondents’ demographic frequency analysis clarifies the background history of the study’s participants and formed the basis for the independent samples t-test and the one-way ANOVA. The respondents performed various professional roles, such as contractors (12%), construction managers (40%), quantity surveyors (36%), architects (4%), and engineers (8%). The qualifications of these professionals were in the order of Master of Philosophy (MPhil) (4%), Master of Science/Architecture (MSc/MArch) (64%), bachelor’s degree holders (24%), and, lastly, Higher National Diploma (HND) holders (8%) in related disciplines. The work experience revealed that 28% of the professionals had between 1 and 5 years of work experience in their respective professions. 24% of the professionals had between 6 and 10 years of work experience, 4% had between 11 and 15 years of work experience, and 44% had more than 15 years of work experience in their respective professions.

Note(s): HND, Higher National Diploma.

Source: Table created by authors.

Awareness levels of Industry 4.0 technologies in the Ghanaian construction industry

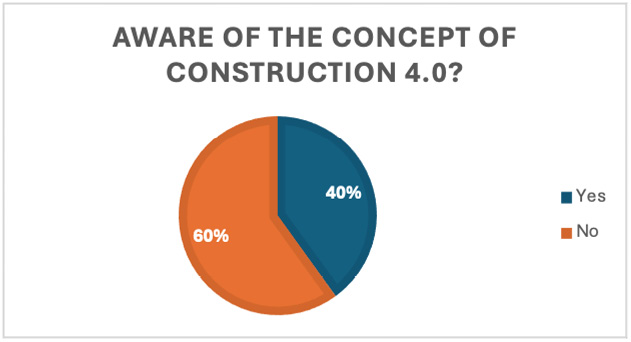

This objective aimed to assess respondents’ level of awareness regarding the concept of Construction 4.0 and its technologies. Descriptive frequency analysis was conducted to determine the extent to which participants were familiar with the concept. The results, presented in Figure 1, revealed that only 40% of the respondents indicated awareness of the concept, while the majority—60%—reported no prior knowledge. These findings highlight a significant knowledge gap within the GCI, suggesting the need for increased sensitization and education on Construction 4.0 concept and its technologies.

Figure 1. Awareness of the concept of Construction 4.0.

Source: Figure created by authors.

To further examine the level of awareness of the 10 Construction 4.0 technologies among professionals, a mean score ranking and a one-sample t-test were conducted. As shown in Table 3, drone technology emerged as the most familiar to respondents, with a mean score (MS) of 3.80 and a standard deviation (SD) of 1.449, indicating statistical significance (p = 0.041). This suggests that drone applications have gained some traction within the GCI, likely due to their increasing visibility in site surveying and monitoring. The IoT and BIM followed, each with a mean score of 3.36, but statistically not significantly different from the stated mean of 3.5. While these results suggest moderate awareness, the mean values indicate that knowledge of these technologies is not yet widespread or deeply embedded in practice.

Note(s): IoT, Internet of Things; BIM, Building Information Modeling; RFID, radio-frequency identification; AI, artificial intelligence; AR, augmented reality.

a One-sample t-test result is significant at 0.05 significance level, p-value < 0.05 (two-tailed); Cronbach’s alpha = 0.936, test value = 3.50.

Source: Table created by authors.

All other technologies assessed, including AI, big data, augmented reality, and robotics, recorded mean scores below 3.5, signifying limited awareness among construction professionals. This underscores a critical knowledge gap and the need for deliberate capacity-building initiatives, including continuous professional development, targeted training programs, and curriculum enhancements (Agyekum et al., 2022a; Kissi et al., 2023; Pittri et al., 2024a). The findings reveal a fragmented understanding of Construction 4.0 technologies, which may hinder their broader adoption and integration. Therefore, increasing industry-wide sensitization and strategic policy interventions are essential for accelerating digital transformation in the GCI (Agyekum et al., 2022a; Kissi et al., 2023; Pittri et al., 2025).

This finding aligns with those of Osunsanmi et al. (2018), who observed that awareness levels among construction professionals on emerging technologies remain suboptimal, largely due to limited understanding of the Industry 4.0 paradigm and insufficient investment in technological research and development (R&D). Similarly, Brous et al. (2020) emphasized that the potential benefits of emerging technologies are often under-communicated within the construction sector, leaving many professionals unaware of their practical applications for improving performance. Dalenogare et al. (2018) further argued that the sector’s low innovation culture and inadequate R&D expenditure contribute significantly to professionals’ limited knowledge of Construction 4.0 technologies. The absence of structured exposure to digital advancements hinders the industry’s ability to adapt to evolving demands. As Maskuriy et al. (2019) contended, effective technology adoption is closely linked to iterative training and institutional support. Without targeted upskilling and knowledge dissemination, the transformative potential of Construction 4.0 technologies will remain largely unrealized, especially in resource-constrained construction environments such as Ghana.

Utilization of Industry 4.0 technologies in the Ghanaian construction industry

This section presents the results of the mean score ranking (MSR) and the one-sample t-test of the level of utilization of the Construction 4.0 technologies. As shown in Table 4, all technologies recorded negative t-values, indicating that their mean scores were significantly below the hypothesized benchmark of 3.5. This suggests that, overall, these technologies are infrequently used within the GCI. Drone technology (MS = 2.92, SD = 1.203, p = 0.00), the Internet of Things (MS = 2.88, SD = 1.513), and Building Information Modeling (MS = 2.64, SD = 1.202) emerged as the most utilized, albeit still under the threshold for moderate usage. Conversely, technologies such as RFID, artificial intelligence, big data analytics, cloud computing, robotics, and 3D printing recorded even lower mean scores, highlighting their minimal integration in practice in the GCI.

Note(s): IoT, Internet of Things; BIM, Building Information Modeling; RFID, radio-frequency identification; AI, artificial intelligence; AR, augmented reality.

a One-sample t-test result is significant at 0.05 significance level, p-value < 0.05 (two-tailed); Cronbach’s alpha = 0.931, test value = 3.50.

Source: Table created by authors.

These findings are consistent with those of Nnaji and Karakhan (2020), who argued that although Industry 4.0 technologies have garnered growing attention in construction discourse, their practical implementation remains at a nascent stage. Originally introduced to enhance efficiency, reduce costs, and improve quality in construction processes, these technologies have yet to be fully integrated into mainstream operations. Despite this, certain technologies such as drones, BIM, and the IoT are beginning to gain traction in specific applications such as site surveying, design simulation, and basic data collection (Suleiman et al., 2022). However, their use remains fragmented and largely superficial, reinforcing the need for strategic efforts to improve awareness, provide hands-on training, and embed digital tools within core project workflows.

Maqbool et al. (2023) highlighted that despite the growing importance of smart technologies like the IoT and BIM, their implementation in Ghana remains minimal due to inadequate skills, limited awareness, and resistance to change. Similarly, Kissi et al. (2023) noted that construction stakeholders in Ghana often encounter barriers such as high costs, lack of training, and poor infrastructure, which constrain the effective deployment of digital solutions like robotics, 3D printing, and cloud computing.

Pittri et al. (2024a) and Mustapha et al. (2024) added that Construction 4.0 technologies, such as unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), are still significantly underused for safety management and monitoring in Ghana, primarily due to technical limitations, lack of policy support, and insufficient industry training. The findings of this study highlight a higher awareness level of UAVs, indicating that although the awareness of UAVs/drones may be growing, practical implementation across firms remains fragmented.

Similarly, in Nigeria, Opawole et al. (2022) found low adoption of 3D printing, attributing it to high initial investment, limited practical exposure, and a weak innovation culture—barriers equally relevant to the GCI. Overall, the low utilization rates confirm a pressing need for strategic investment in skills development, regulatory frameworks, and infrastructure to facilitate meaningful adoption of Construction 4.0 technologies in Ghana.

Independent samples t-test for the level of utilization of Industry 4.0 technologies

Statistical differences in the utilization of Construction 4.0 technologies based on respondents’ awareness were examined using the independent samples t-test. As shown in Table 5, significant differences (p < 0.05) were found in the usage of nine out of the 10 technologies, indicating that low utilization of Construction 4.0 technologies in the GCI is largely driven by limited awareness. Robotics was the only exception, suggesting that its low adoption may be attributed to other barriers such as high costs and technical complexity. These findings support the assertions of Newman et al. (2021) and Müller et al. (2018), who noted that while Construction 4.0 research is emerging, its practical application in developing contexts remains limited. The results underscore the critical role of awareness in driving adoption and highlight the need for strategic interventions, such as curriculum reforms, targeted training, and innovation-friendly environments, to foster technological readiness in the GCI (Maskuriy et al., 2019).

Note(s): AR, augmented reality; AI, artificial intelligence; BIM, Building Information Modeling; RFID, radio-frequency identification; IoT, Internet of Things.

*Independent samples t-test result is significant at 0.05 significance level, p-value < 0.05 (two-tailed).

Source: Table created by authors.

One-way ANOVA for the level of utilization of Industry 4.0 technologies

Statistically significant differences in the means of the level of utilization of the Industry 4.0 technologies in the GCI were assessed under this section based on the profession (categorized as contractors, construction managers, architects, quantity surveyors, and engineers) and experience (i.e., 1–5, 6–10, 11–15, and over 15 years) of the respondents. This was carried out using one-way ANOVA statistics as presented in Tables 6 and 7. The results based on both the profession and experience of respondents revealed that there were significant differences in the views of the construction professionals. All the Industry 4.0 technologies emerged as significantly different among the groups [p (two-tailed) ≤ 0.05]. This indicates that the professional roles and experience of the respondents influence the utilization of Industry 4.0 technologies in the GCI.

Note(s): AR, augmented reality; AI, artificial intelligence; BIM, Building Information Modeling; RFID, radio-frequency identification; IoT, Internet of Things.

Source: Table created by authors.

Note(s): AR, augmented reality; AI, artificial intelligence; BIM, Building Information Modeling; RFID, radio-frequency identification; IoT, Internet of Things.

Source: Table created by authors.

Studies have shown that professionals, such as architects and engineers, who typically possess specialized training and technological competence, are more likely to integrate digital tools into their workflows (Nnadi and Akabudike, 2024). Nguyen et al. (2023) emphasized that practitioner expertise directly impacts risk perception and willingness to adopt innovation. While experience can enhance decision-making, it does not always equate to proficiency with emerging technologies, particularly in contexts where digital tools are still evolving (Nguyen et al., 2023). Gong et al. (2024) further highlighted that organizational size and employee experience levels are critical to technology uptake, especially for complex systems like big data. Additionally, professionals aligned with sustainability goals tend to adopt innovative tools more readily, whereas resistance often stems from rigid traditional practices (Wafai and Aouad, 2023).

Conclusions

This study aimed to assess the awareness and utilization of Industry 4.0 technologies within the GCI, focusing on how professional role, experience, and awareness levels influence adoption. Drawing on data from 100 construction professionals, the findings revealed a generally low level of awareness and utilization, with drone technology emerging as the most recognized and moderately used tool, while technologies such as AR, robotics, and 3D printing showed the least usage. One-sample t-tests confirmed that the mean utilization scores for all technologies fell significantly below the expected threshold. Furthermore, independent samples t-tests and one-way ANOVA demonstrated that awareness, profession, and experience significantly influenced usage patterns. These results suggest that adoption remains limited, not due to a lack of access alone but because of gaps in the training, exposure, and role-specific applicability of these technologies within the GCI. Table 8 provides a summary of the study’s hypotheses, the statistical tests employed, and the corresponding decisions regarding their acceptance or rejection based on the analysis results.

Source: Table created by authors.

Practical implications

The study highlights an urgent need for targeted interventions to drive digital transformation in the GCI. Industry practitioners should collaborate with academic institutions to develop continuous professional development programs tailored to different roles within the industry. Construction firms must also invest in onboarding and upskilling initiatives to bridge technological gaps, particularly in underutilized areas such as AI, AR, and big data. Policymakers are encouraged to provide incentive frameworks such as tax reliefs or grants to support digital innovation adoption, especially among small and medium-sized enterprise. Furthermore, integrating Construction 4.0 technologies into university curricula will equip future professionals with the skills needed for a tech-driven construction landscape. Construction firms are recommended to improve the integration of Industry 4.0 technologies in their operations by developing a new or updated Industry 4.0 implementation plan and communicating the information to employees to improve their readiness for the change.

Theoretical implications

This study contributes to the growing body of literature on Construction 4.0 by providing empirical evidence from a developing country context. It reinforces the argument that awareness and professional characteristics are critical determinants of technology adoption. The results support further theory-building around technology acceptance and digital readiness frameworks in low-resource settings.

Limitations and directions for future research

A key limitation of this study is its reliance on non-probabilistic sampling, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. While steps were taken to ensure diversity in roles and regional representation, future studies should consider stratified or random sampling techniques where feasible. Additionally, the study adopted a descriptive and comparative statistical approach using t-tests and ANOVA, which, although appropriate for identifying group differences, did not model causal relationships. Future research could employ Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to examine the structural relationships between awareness, perceived benefits, organizational factors, and technology utilization. Longitudinal studies are also recommended to capture changes in adoption patterns over time as digital infrastructure and training improve in the GCI.

The study relied solely on quantitative data, which, while effective for identifying patterns and group differences, does not capture the nuanced, context-specific barriers and motivations influencing technology adoption. The absence of qualitative insights restricts a deeper understanding of organizational culture, behavioral resistance, and structural limitations. Future research should consider adopting a mixed-methods approach, incorporating interviews or focus groups to explore subjective experiences, perceptions, and institutional barriers to adoption. Expanding the research to other developing countries would also support comparative analysis and strengthen the global discourse on Construction 4.0 adoption in low-resource settings.

Additionally, the study focused on only 10 commonly cited Industry 4.0 technologies, potentially overlooking emerging or context-specific innovations; future research could expand the scope to include a broader and evolving set of technologies relevant to diverse construction environments.

References

Abioye, S.O., Oyedele, L.O., Akanbi, L., Ajayi, A., Delgado, J.M.D., Bilal, M., Akinade, O.O., & Ahmed, A. (2021). Artificial intelligence in the construction industry: A review of present status, opportunities, and future challenges. Journal of Building Engineering, [e-journal] 44, 103299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2021.103299

Addy, M.N., Kwofie, T.E.E., Agbonani, D.M., & Essegbey, A.E. (2023). Using the TOE theoretical framework to study the adoption of BIM-AR in a developing country: the case of Ghana. Journal of Engineering, Design and Technology, [e-journal] Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEDT-02-2022-0096

Adepoju, O.O., & Aigbavboa, C.O. (2021). Assessing knowledge and skills gap for construction 4.0 in a developing economy. Journal of Public Affairs, 21(3), p.e2264. https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.2264

Agyekum, A.K., Fugar, F.D.K., Agyekum, K., Akomea-Frimpong, I., & Pittri, H. (2022b). Barriers to stakeholder engagement in sustainable procurement of public works. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, [e-journal] Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/ECAM-08-2021-0746

Agyekum, K., Amudjie, J., Pittri, H., Dompey, A.M.A., & Botchway, E.A. (2023a). Prioritizing the principles of circular economy among built environment professionals. Built Environment Project and Asset Management, [e-journal] Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/BEPAM-04-2023-0077

Agyekum, K., Dompey, A.M.A., Pittri, H., & Botchway, E.A. (2023b). Design for maintainability (DfM) implementation among design professionals: empirical evidence from a developing country context. International Journal of Building Pathology and Adaptation. Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBPA-06-2023-0078

Agyekum, K., Pittri, H., Botchway, E.A., Amudjie, J., Kumah, V.M.A., Kotei-Martin, J.N., & Oduro, R.A. (2022a). Exploring the current technologies essential for health and safety in the Ghanaian construction industry. Merits, [e-journal] 2(4), pp.314-330. https://doi.org/10.3390/merits2040022

Agyekum, K., Simons, B., & Botchway, S.Y. (2018). Factors influencing the performance of safety programmes in the Ghanaian construction industry. Acta Structilia, 25(2), pp.39-68. https://doi.org/10.18820/24150487/as25i2.2

Anitah, J.N., Nyamwange, S.O., Magutu, P.O., Chirchir, M., & Mose, J.M. (2019). Industry 4.0 technologies and operational performance of Unilever Kenya and L’Oreal East Africa. Noble International Journal of Business and Management Research, 3(10), pp.125-134.

Aryal, B., Chapagain, D., Dhakal, B., & Aryal, B. (2023). Application of Information Technology in Construction: A Case from Nepal. Apex Journal of Business and Management, 1(01), pp.91-102. https://ssrn.com/abstract=4609055. https://doi.org/10.61274/apxc.2023.v01i01.007

Attoue, N., Shahrour, I., & Younes, R. (2018). Smart building: Use of the artificial neural network approach for indoor temperature forecasting. Energies, [e-journal] 11(2), 395. https://doi.org/10.3390/en11020395

Babalola, A., Manu, P., Cheung, C., Yunusa-Kaltungo, A., & Bartolo, P. (2023). A systematic review of the application of immersive technologies for safety and health management in the construction sector. Journal of Safety Research, 85, pp.66-85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsr.2023.01.007

Bai, C., Dallasega, P., Orzes, G., & Sarkis, J. (2020). Industry 4.0 technologies assessment: A sustainability perspective. International Journal of Production Economics, [e-journal] 229, 107776. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2020.107776

Bakar, M.R.A., Razali, N.A.M., Ishak, K.K., Ismail, M.N., & Sembok, T.M.T. (2024). Adoption of Industry 4.0 with cloud computing as a mediator: Evaluation using TOE framework for SMEs. JOIV: International Journal on Informatics Visualization, 8(2), pp.554-563. https://doi.org/10.62527/joiv.8.2.2205

Begić, H., & Galić, M. (2021). A Systematic Review of Construction 4.0 in the Context of the BIM 4.0 Premise. Buildings, 11(8), p.337. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings11080337

Bongomin, O., Gilibrays Ocen, G., Oyondi Nganyi, E., Musinguzi, A., & Omara, T. (2020). Exponential disruptive technologies and the required skills of industry 4.0. Journal of Engineering, [e-journal] 2020(1), pp.1-17. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/4280156

Botchway, E.A., Agyekum, K., Kotei-Martin, J.N., Pittri, H., Dompey, A.M.A., Afram, S.O., & Asare, N.E. (2023b). Achieving healthy city development in Ghana: referencing sustainable development Goal 11. Sustainability, [e-journal] 15(19), 14361. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914361

Botchway, E.A., Asare, S.S., Agyekum, K., Salgin, B., Pittri, H., Kumah, V.M.A., & Dompey, A.M.A. (2023a). Competencies driving waste minimization during the construction phase of buildings. Buildings, [e-journal] 13(4), 971. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13040971

Brous, P., Janssen, M., & Herder, P. (2020). The dual effects of the Internet of Things (IoT): a systematic review of the benefits and risks of IoT adoption by organizations. International Journal of Information Management, [e-journal] 51, 101952. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.05.008

Chung, W.W.S., Tariq, S., Mohandes, S.R., & Zayed, T. (2020). IoT-based application for construction site safety monitoring. International Journal of Construction Management, 23(1), pp.58-74. https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2020.1847405

Culot, G., Nassimbeni, G., Orzes, G., & Sartor, M. (2020). Behind the definition of Industry 4.0: Analysis and open questions. International Journal of Production Economics, 226, 107617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2020.107617

Dalenogare, L.S., Benitez, G.B., Ayala, N.F., & Frank, A.G. (2018). The expected contribution of Industry 4.0 technologies for industrial performance. International Journal of Production Economics, 204, pp.383-394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2018.08.019

Dawood, N., Rahimian, F., & Sheikhkhoshkar, M. (2022). Industry 4. 0 applications for full lifecycle integration of buildings. 21st International Conference on Construction Applications of Virtual Reality. Middlesbrough, UK, 08-10 December 2021. North Yorkshire: Teesside University.

Delgado, J.M.D., Oyedele, L., Demian, P., & Beach, T. (2020). A research agenda for augmented and virtual reality in architecture, engineering and construction. Advanced Engineering Informatics, [e-journal] 45, 101122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aei.2020.101122

Dhamija, P. (2022). South Africa in the era of Industry 4.0: An insightful investigation. Scientometrics, [e-journal] 127(9), pp.5083-5110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-022-04461-z

Dosumu, O.S., & Uwayo, S.M. (2023). Modeling the adoption of Internet of things (IoT) for sustainable construction in a developing economy. Built Environment Project and Asset Management, 13(3), pp.394-411. https://doi.org/10.1108/BEPAM-08-2022-0123

Erboz, G. (2017). How to define Industry 4.0: main pillars of Industry 4.0. 7th International Conference on Management. Nitra, Slovakia, 01-02 June 2017.

Forcael, E., Ferrari, I., Opazo-Vega, A., & Pulido-Arcas, J.A. (2020). Construction 4.0: A literature review. Sustainability, [e-journal] 12(22), 9755. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229755

Gbolagade, O.L., Alao, B.B. & Mashi, M.S. (2022). Contributions of Industry 4.0 to the performance of entrepreneurship in Katsina State, Nigeria. World Review of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development, 18(5-6), pp.581-591. https://doi.org/10.1504/WREMSD.2022.125636

Gong, D., Zhao, X., & Yang, B. (2024). Big Data Adoption in the Chinese Construction Industry: Status Quo, Drivers, Challenges, and Strategies. Buildings, 14(7), p.1891. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14071891

Ibrahim, K., Simpeh, F., & Adebowale, O.J. (2024). Awareness and adoption of wearable technologies for health and safety management in the Nigerian construction industry. Frontiers in Engineering and Built Environment, 4(1), pp.15-28. https://doi.org/10.1108/FEBE-11-2022-0041

IEA, U. (2018). Global Status Report: Towards a zero-emission, efficient and resilient buildings and construction sector. [online] Available at: https://www.iea.org/reports/2018-global-status-report [Accessed 20 October 2024].

Isayev, J. (2023). The importance of the digital economy in the development of the construction industry. In E3S Web of Conferences (Vol. 460, p. 03008). EDP Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202346003008

Jayani Rajapathirana, R.P., & Hui, Y. (2018). Relationship between innovation capability, innovation type, and firm performance. Journal of Innovation and Knowledge, [e-journal] 3(1), pp.44-55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2017.06.002

Jo, B.W., Lee, Y.S., Khan, R.M.A., Kim, J.H. & Kim, D.K. (2019). Robust Construction Safety System (RCSS) for collision accidents prevention on construction sites. Sensors, [e-journal] 19(4), 932. https://doi.org/10.3390/s19040932

Kazemzadeh, D., Nazari, A., & Rokooei, S. (2021). Application of augmented reality in the life cycle of construction projects. 21st International Conference on Construction Applications of Virtual Reality. Middlesbrough, UK, 08-10 December 2021. North Yorkshire: Teesside University.

Kent State University. (2024). SPSS tutorials: one-way ANOVA. [online] Available at: https://libguides.library.kent.edu/spss/onewayanova#:~:text=One%2DWay%20ANO VA%20(%22analysis,One%2DFactor%20ANOVA [Accessed 20 October 2024].

Kissi, E., Aigbavboa, C., & Kuoribo, E. (2023). Emerging technologies in the construction industry: challenges and strategies in Ghana. Construction Innovation, 23(2), pp.383-405. https://doi.org/10.1108/CI-11-2021-0215

Koranteng, C., Simons, B., Gyimah, K.A., & Nkrumah, J. (2023). Ghana’s green building assessment journey: An appraisal of the thermal performance of an office building in Accra. Journal of Engineering, Design and Technology, [e-journal] 21(1), pp.188-205. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEDT-02-2021-0109

Kotei-Martin, J.N., Agyekum, K., Pittri, H., Opoku, A., Atuahene, B.T., & Gasue, R. (2025). Design professionals’ awareness and engagement in design for adaptability (DfA) practices. Journal of Responsible Production and Consumption, 2(1), pp.83-109. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRPC-12-2024-0072

Kozlovska, M., Klosova, D., & Strukova, Z. (2021). Impact of industry 4.0 platform on the formation of construction 4.0 concept: a literature review. Sustainability, [e-journal] 13(5), 2683. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052683

Krupík, P. (2020). 3D printers as part of Construction 4.0 with a focus on transport constructions. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, [e-journal] 867, 012025. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/867/1/012025

Kumah, V.M.A., Agyekum, K., Botchway, E.A., Pittri, H., & Danso, F.O. (2022). Examining built environment professionals’ willingness to pay for green buildings in Ghana. Buildings, [e-journal] 12(12), 2097. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings12122097

Li, J., Greenwood, D., & Kassem, M. (2019). Blockchain in the built environment and construction industry: A systematic review, conceptual models and practical use cases. Automation in Construction, [e-journal] 102, pp.288-307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2019.02.005

Liao, Y., Deschamps, F., Loures, E.D.F.R., & Ramos, L.F.P. (2017). Past, present and future of Industry 4.0-a systematic literature review and research agenda proposal. International Journal of Production Research, [e-journal] 55(12), pp.3609–3629. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2017.1308576

Lu, Y., & Cecil, J. (2016). An Internet of Things (IoT)-based collaborative framework for advanced manufacturing. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, [e-journal] 84, pp.1141-1152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-015-7772-0

Maisiri, W., & Van Dyk, L. (2019). Industry 4.0 readiness assessment for South African industries. South African Journal of Industrial Engineering, 30(3), pp.134-148.

Manda, M.I. and Ben Dhaou, S., 2019. Responding to the challenges and opportunities in the 4th Industrial Revolution in developing countries. 12th international conference on theory and practice of electronic governance. Melbourne, Australia, 03–05 April 2019. https://doi.org/10.1145/3326365.3326398

Maqbool, R., Saiba, M.R., & Ashfaq, S. (2023). Emerging industry 4.0 and Internet of Things (IoT) technologies in the Ghanaian construction industry: sustainability, implementation challenges, and benefits. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, [e-journal] 30, pp.37076–37091. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-24764-1

Maskuriy, R., Selamat, A., Ali, K.N., Maresova, P., & Krejcar, O. (2019). Industry 4.0 for the construction industry-How ready is the industry? Applied Sciences, [e-journal] 9(14), 2819. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9142819

Müller, J.M., Kiel, D., & Voigt, K.I. (2018). What drives the implementation of Industry 4.0? The role of opportunities and challenges in the context of sustainability. Sustainability, [e-journal] 10(1), 247. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10010247

Mustapha, Z., Akomah, B.B., Kwaku, O.E., & Tieru, C.K. (2024). Enhancing Safety Management in the Ghanaian Construction Industry: Evaluating the Role of UAV Implementation and Construction Managers Understanding. Journal of Civil Engineering Frontiers (JoCEF), 5(2). file:///C:/Users/hayfo/Downloads/FullManuscript-312-2-10-20240821%20(4).pdf

Newman, C., Edwards, D., Martek, I., Lai, J., Thwala, W.D., & Rillie, I. (2021). Industry 4.0 deployment in the construction industry: a bibliometric literature review and UK-based case study. Smart and Sustainable Built Environment, [e-journal] 10(4), pp.557-580. https://doi.org/10.1108/SASBE-02-2020-0016

Nguyen, H.D., Do, Q.N.H., & Macchion, L. (2023). Influence of practitioners’ characteristics on risk assessment in Green Building projects in emerging economies: a case of Vietnam. Engineering, construction and architectural management, 30(2), pp.833-852. https://doi.org/10.1108/ECAM-05-2021-0436

Nnadi, E.E., & Akabudike, P.O. (2024). Mitigating Professional Interference for Sustainable Growth in the Nigerian Construction Industry: A Comprehensive Review. Journal of Engineering, Technology, and Applied Science (JETAS), 6(2), pp.49-56. DOI: 10.36079/lamintang.jetas-0602.640

Nnaji, C., & Karakhan, A.A. (2020). Technologies for safety and health management in construction: Current use, implementation benefits and limitations, and adoption barriers. Journal of Building Engineering, [e-journal] 29, 101212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2020.101212

Oduro, S., Pittri, H., Simons, B., Baah, B., Anteh, E.D., & Oduro, J.A. (2024). Awareness of net zero energy buildings among construction professionals in the Ghanaian construction industry. Built Environment Project and Asset Management. https://doi.org/10.1108/BEPAM-01-2024-0001

Oesterreich, T.D., & Teuteberg, F. (2016). Understanding the implications of digitisation and automation in the context of Industry 4.0: A triangulation approach and elements of a research agenda for the construction industry. Computers in industry, [e-journal] 83, pp.121-139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compind.2016.09.006

Oke, A.E., Atofarati, J.O., & Bello, S.F. (2022). Awareness of 3D printing for sustainable construction in an emerging economy. Construction Economics and Building, 22(2), pp.52-68. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.715146401831631

Opawole, A., Olojede, B.O., & Kajimo-shakantu, K. (2022). Assessment of the adoption of 3D printing technology for construction delivery: A case study of Lagos State, Nigeria. Journal of Sustainable Construction Materials and Technologies, 7(3), pp.184-197. https://doi.org/10.47481/jscmt.1133794

Osunsanmi, T.O., Aigbavboa, C., & Oke, A. (2018). Construction 4.0: the future of the construction industry in South Africa. International Journal of Civil and Environmental Engineering, 12(3), pp.206–212.

Paliwal, S., Choi, J.O., Bristow, J., Chatfield, H.K., and Lee, S. (2021). Construction stakeholders’ perceived benefits and barriers for environment-friendly modular construction in a hospitality centric environment. International Journal of Industrialized Construction, 2(1), pp.15–29.

Patel, K.K., & Patel, S.M. (2016). Internet of things-IOT: definition, characteristics, architecture, enabling technologies, application and future challenges. International Journal of Engineering Science and Computing, 6(5), pp. 6122-6131.

Perrier, N., Bled, A., Bourgault, M., Cousin, N., Danjou, C., Pellerin, R., & Roland, T. (2020). Construction 4.0: a survey of research trends. Journal of Information Technology in Construction, 25, pp.416-437. https://doi.org/10.36680/j.itcon.2020.024

Pessoa, S., Guimarães, A.S., Lucas, S.S., & Simões, N. (2021). 3D printing in the construction industry-A systematic review of the thermal performance in buildings. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, [e-journal] 141, 110794. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2021.110794

Pittri, H., Godawatte, G.A.G.R., Agyekum, K., Dompey, A.M.A., Botchway, B., & Narh, E. (2024a). The application of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) for health and safety management in the construction industry. International Journal of Building Pathology and Adaptation. Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBPA-10-2024-0209

Pittri, H., Agyekum, K., Ayebeng Botchway, E., Opoku, A., & Bimpli, I. (2024b). Design for deconstruction (DfD) implementation among design professionals: empirical evidence from Ghana. International Journal of Construction Management, [e-journal] 24(13), pp.1387-1397. https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2023.2174663

Pittri, H., Godawatte, G.A.G.R., Esangbedo, O.P., Antwi-Afari, P., & Bao, Z. (2025). Exploring barriers to the adoption of digital technologies for circular economy practices in the construction industry in developing countries: A case of Ghana. Buildings, 15(7), p.1090. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15071090

Rghioui, A., & Oumnad, A. (2017). Internet of Things: Visions, technologies, and areas of application. Automation, Control and Intelligent Systems, [e-journal] 5(6), pp.83-91. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.acis.20170506.11

Ribeiro, D.B., Coutinho, A.D.R., Satyro, W.C., Campos, F.C.D., Lima, C.R.C., Contador, J.C., & Gonçalves, R.F. (2022). The DAWN readiness model to assess the level of use of Industry 4.0 technologies in the construction industry in Brazil. Construction Innovation, 24(2), pp.515-536. https://doi.org/10.1108/CI-05-2022-0114

Schönbeck, P., Löfsjögård, M., & Ansell, A. (2020). Quantitative review of construction 4.0 technology presence in construction project research. Buildings, [e-journal] 10(10), 173. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings10100173

Schwab, K., & Davis, N., 2018. Shaping the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Geneva: World Economic Forum.

Shahzad, M., Shafq, M.T., Douglas, D., & Kassem, M. (2022). Digital twins in built environments: an investigation of the characteristics, applications, and challenges. Buildings, [e-journal] 12(2), 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings12020120

Sisinni, E., Saifullah, A., Han, S., Jennehag, U., & Gidlund, M. (2018). Industrial Internet of things: challenges, opportunities, and directions. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics, [e-journal] 14(11), pp. 4724-4734. https://doi.org/10.1109/TII.2018.2852491

Suleiman, Z., Shaikholla, S., Dikhanbayeva, D., Shehab, E., & Turkyilmaz, A. (2022). Industry 4.0: Clustering of concepts and characteristics. Cogent Engineering, [e-journal] 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311916.2022.2034264

Tankova, T., & da Silva, L.S. (2020). Robotics and additive manufacturing in the construction industry. Current Robotics Reports, [e-journal] 1, pp.13-18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43154-020-00003-8

Venter, B., Ngobeni, S.P., & du Plessis, H. (2021). Factors influencing the adoption of Building Information Modeling (BIM) in the South African Construction and Built Environment (CBE) from a quantity surveying perspective. Engineering Management in Production and Services, 13(3). 10.2478/emj-2021-0027

Wafai, M.H., & Aouad, G. (2023). Innovation transfer in construction: Re-interpreting factor-based research from the perspective of the social construction of technology (SCOT). Construction Innovation, 23(5), pp.1323-1344. https://doi.org/10.1108/CI-08-2017-0070

Wang, Y., & Hajli, N. (2017). Exploring the path to big data analytics success in healthcare. Journal of Business Research, [e-journal] 70, pp.287-299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.08.002

Williams, J., Fugar, F., & Adinyira, E. (2020). Assessment of health and safety culture maturity in the construction industry in developing economies: a case of Ghanaian construction industry. Journal of Engineering, Design and Technology, [e-journal] 18(4), pp.865-881. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEDT-06-2019-0151

Xu, X., Lu, Y., Vogel-Heuser, B., & Wang, L. (2021). Industry 4.0 and Industry 5.0-Inception, conception and perception. Journal of Manufacturing Systems, [e-journal] 61, pp.530-535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmsy.2021.10.006

You, Z., & Feng, L. (2020). Integration of industry 4.0 related technologies in construction industry: a framework of cyber-physical system. Ieee Access, [e-journal] 8, pp. 122908-122922. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3007206

Zabidin, N.S., Belayutham, S., & Che Ibrahim, C.K.I. (2024). The knowledge, attitude and practices (KAP) of Industry 4.0 between construction practitioners and academicians in Malaysia: a comparative study. Construction Innovation, 24(5), pp.1185-1204. https://doi.org/10.1108/CI-05-2022-0109