Construction Economics and Building

Vol. 25, No. 2

July 2025

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Gender’s Moderating Effect on Perceived Organizational Politics and Withdrawal Dimensions Among Construction Professionals

Yuvaraj Dhanasekar, Anandh KS*

Department of Civil Engineering, Faculty of Engineering and Technology, SRM Institute of Science and Technology, Kattankulathur, India

Corresponding author: Anandh KS, anandh.ks@gmail.com

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v25i2.9358

Article History: Received 24/09/2024; Revised 11/11/2024; Accepted 02/02/2025; Published 08/08/2025

Citation: Dhanasekar, Y., Anandh, K. S. 2025. Gender’s Moderating Effect on Perceived Organizational Politics and Withdrawal Dimensions Among Construction Professionals. Construction Economics and Building, 25:2, 69–88. https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v25i2.9358

Abstract

The current study, supported by equity theory of motivation, explores how gender moderates perceived organizational politics effects on psychological and physical organizational withdrawal behaviors of professionals within the construction sector, a field characterized by a challenging work environment and high employee turnover. Quantitative data were collected from 318 construction professionals and analyzed using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). The findings reveal that perceived organizational politics significantly and positively impacts both psychological and physical withdrawal behaviors among construction professionals. Further, gender moderates this relationship, with female professionals showing a greater tendency to disengage compared to their male counterparts. This research contributes to the construction management literature by highlighting the gender effects of organizational politics on employee withdrawal, a previously underexplored area. The study underscores the critical need for organizations to address political dynamics in the workplace to foster a fair and supportive environment, ultimately enhancing employee well-being and organizational performance.

Keywords

Perceived Organizational Politics; Organizational Withdrawal; Psychological Withdrawal; Physical Withdrawal; Construction Industry

Introduction

The construction industry (CI), a key contributor to global economic and infrastructure development, is structured by complex dynamics and strenuous working conditions (Rajprasad, Thamilarasu and Mageshwari, 2018; Anandh, Gunasekaran and Mannan, 2020). Despite its significance, the industry grapples with high employee turnover, which is often assessed by attrition rates or intention to leave and is defined as the rate at which individuals voluntarily leave an organization. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics report, the average attrition rate of employees in the United States during 2022 was 53% (Hansen, 2024). Similarly, the sector in India experienced a 13.3% voluntary turnover rate in 2017–2018 (Pathan and Vinay, 2021). This trend is further exacerbated by factors such as gender bias, low work-life balance, and hazardous conditions, making it even more crucial to address these concerns in order to retain talented workforce in this competitive sector (Morello, Issa and Franz, 2018).

Despite extensive research on employee turnover intention (Abdolmaleki, et al., 2024), a significant gap exists in construction management literature on organizational politics (OP), an antecedent of employee turnover (Burakova, McDowall and Bianvet, 2022). This study thus aims to address this gap by focusing on how perceived organizational politics (POP) influences organizational withdrawal (OW) among Indian construction professionals, with an emphasis on gender. With its extensive and diverse workforce (Dhanasekar, Anandh and Szóstak, 2023), the Indian CI provides a distinctive setting for investigating these dynamics. Despite being a substantial employment generator and on track to become the third-largest construction market globally (Edison, 2020), there is a lack of empirical evidence in the Indian setting, necessitating further research to understand the relationship between organizational withdrawal behaviors and OP perceptions of construction professionals.

OW, which encompasses absenteeism, tardiness, and turnover intention (Laczo and Hanisch, 1999), is a pressing concern across industries, including construction. These behaviors impact individual well-being and significantly affect organizational productivity and performance (AbouRizk, et al., 2010; Zhang, et al., 2023). While research has linked OW to stress, pay dissatisfaction, organizational support, and limited growth opportunities (Beehr and Gupta, 1978; Park, et al., 2016; Pepple, Akinsowon and Oyelere, 2023), the role of OP in the construction context remains under-explored. POP, the subjective perception of OP (Ferris and Kacmar, 1992), can create feelings of injustice, mistrust, and job insecurity, influencing OW behaviors (Chang, Rosen and Levy, 2009; Meisler, Drory and Vigoda-Gadot, 2020). Thus, knowledge about the role of POP in OW is significant for a healthy and efficient work climate acquisition.

Despite substantial evidence linking POP to turnover intention (Harris, Harris and Harvey, 2007; Sexton and Zhang, 2022; De Clercq, Khan and Haq, 2023), focusing solely on turnover intention may not fully capture disengagement. OW offers a broader perspective by identifying disengagement behaviors that precede turnover, encompassing physical and psychological withdrawal dimensions (Erdemli, 2015). Examining POP’s influence on OW provides a more comprehensive understanding, enabling early intervention to prevent turnover. Therefore, the study’s first objective is to investigate how POP impacts physical and psychological OW dimensions among construction professionals.

Given the CI’s male-dominated nature (Norberg and Johansson, 2021), gender is considered a potential moderator in the POP–OW relationship. Research indicates that women may be more sensitive to political environments and perceive OP more strongly than men (Rosen, Levy and Hall, 2006; Snipes, et al., 2023), potentially due to societal norms, organizational culture, and power dynamics. These gender differences may lead to varied experiences and responses to OP. Acknowledging these nuances is crucial for developing strategies to mitigate POP’s effects. Thus, the second objective is to determine whether gender moderates the relationship between POP and physical and psychological OW.

Prior research on POP has employed various theoretical frameworks, including equity theory, perceived organizational support theory, conservation of resources theory, and social exchange theory (Rashid, Islam and Ahmer, 2019; Jeong and Kim, 2022; Rughoobur-Seetah, 2022; Kaur and Kang, 2023). The current study is supported by Adams’ equity theory of motivation (Adams, 1963) in examining how employees’ fairness perceptions affect organizational politics and disengagement with gender moderation. The theory explains how perceived unfairness, especially in politically sensitive circumstances, might cause employees to disconnect psychologically or physically.

The subsequent sections provide a detailed theoretical background, hypothesis development, methodology, analysis, and interpretation of results, along with practical implications, limitations, and suggestions for future research.

Theoretical background and hypotheses development

Perceived organizational politics

OP is common in the workplace, where individuals or organizations employ power and influence to achieve their objectives (Mintzberg, 1983). According to Goo, et al. (2019), it refers to the deliberate actions or behaviors that promote or safeguard one’s self-interest at the expense of others or organizational goals in the workplace. The concept of POP arises from the perception of the workplace as inequitable and discriminatory by employees in political environments (Cho and Yang, 2018; Dhanasekar and Anandh, 2025). It refers to the individual’s subjective perception of the self-serving behaviors occurring within their workplace. These self-serving behaviors frequently involve using power, influence, and manipulation to achieve personal or organizational goals (Kacmar and Carlson, 1997; Ferris and Treadway, 2012). It substantially impacts employees’ attitudes and behaviors toward the organization (Ferris, et al., 1989).

POP includes three primary dimensions: General Political Behavior (GPB), Go Along to Get Ahead (GAGA), and Pay and Promotion Policies (PPP) (Kacmar and Ferris, 1991; Kacmar and Carlson, 1997). GPB involves perceived politically motivated behaviors, fostering a sense of workplace politics, leading to stress and reduced trust (Ferris, et al., 1989; Kacmar and Ferris, 1991; Vigoda, 2000). GAGA reflects conforming to political norms for career advancement, even compromising personal values (Kacmar and Carlson, 1997; Landells and Albrecht, 2019). PPP emphasizes political influence in professional progression and rewards, which can lower satisfaction and raise turnover intentions (Kacmar and Carlson, 1997; Vigoda, 2000).

Understanding the consequences of POP is of both academic and practical importance, as it significantly influences an employee’s emotional, mental, and behavioral responses. Previous studies have consistently demonstrated a negative association between POP and key organizational metrics, including, job satisfaction, commitment, work engagement, performance, and employee well-being (Karatepe, 2013; Asrar-ul-Haq, et al., 2019; Ullah, et al., 2019). Conversely, a positive correlation has been observed with turnover intention (De Clercq, Khan and Haq, 2023).

Organizational withdrawal

OW is an essential facet of organizational behavior encompassing behaviors indicative of an employee’s disengagement (Spendolini, 1985; Hanisch and Hulin, 1990). It is explained in two primary forms: physical and psychological withdrawal (Lehman and Simpson, 1992; Mirsepasi, et al., 2012; Erdemli, 2015). Physical withdrawal (PW) is a condition that is defined by absenteeism and turnover, which leads to the physical separation of an employee from their employment (Lehman and Simpson, 1992; Mirsepasi, et al., 2012; Erdemli, 2015). In contrast, psychological withdrawal (PSW) is the process by which employees mentally disengage from their work despite their physical presence. This encompasses non-work-related activities and minimal effort in allotted duties, which suggest that personal interests are prioritized over organizational objectives (Lehman and Simpson, 1992; Erdemli, 2015; Aggarwal, et al., 2020).

Withdrawal behaviors often stem from job dissatisfaction, low commitment, and perceived injustice (Brunetto, et al., 2012; Khalid, et al., 2022). Organizational factors also exacerbate disengagement, including inadequate communication, recognition, and development opportunities (Kanungo and Mendonca, 2002; Newman, et al., 2020). Furthermore, the susceptibility to OW is influenced by work-life imbalance and individual characteristics such as personality and stress management capabilities, which significantly influence how employees respond to workplace stressors (Peng and Li, 2023). The consequences of OW are significant, affecting both individuals and organizations through decreased productivity, increased costs, and decreased job satisfaction (Alexander, 2016). Apart from the loss of investment, existing employees may be demotivated, and their morale may be adversely affected by the withdrawal of an employee (Asrar-ul-Haq, et al., 2019).

Perceived organizational politics and organizational withdrawal

The association between POP and OW is well-established, with research suggesting that increased political perceptions may exacerbate withdrawal behaviors (Ferris, et al., 1989; Vigoda, 2000). Employees who perceive their work environment as unjust or dominated by politics frequently disengage, demonstrating behaviors such as turnover intentions, absenteeism, and psychological withdrawal (Cropanzano, et al., 1997; Abbas, et al., 2014; Landells and Albrecht, 2019; Atshan, et al., 2022; Singh and Randhawa, 2022). Recent research has shed light on the nuanced ways POP impacts OW. Meisler (2022) underscores the role of fear in the exacerbation of OW due to POP, particularly within the public sector. The study implies that employees’ fear of negative consequences resulting from political maneuvering can elicit withdrawal behaviors. Additionally, Sabo Bello, et al. (2021) found a negative correlation between POP and organizational commitment, implying that a political climate can erode employees’ sense of loyalty and belonging, potentially contributing to withdrawal. Furthermore, while POP has been linked to both physical and psychological withdrawal, Vigoda (2000) posits that psychological withdrawal is more prevalent in environments with high exit costs, such as the public sector. This implies that employees may choose psychological disengagement as a coping mechanism in response to perceived political behavior when they anticipate that leaving the organization will be difficult or expensive.

Drawing upon the extant literature, the following hypotheses are put forth.

Hypothesis 1:

Null Hypothesis (H0): There is no significant positive relationship between POP and PSW among construction professionals.

Alternate Hypothesis (H1): A significant positive relationship exists between POP and PSW among construction professionals.

Hypothesis 2:

Null Hypothesis (H0): There is no significant positive relationship between POP and PW among construction professionals.

Alternate Hypothesis (H2): A significant positive relationship exists between POP and PW among construction professionals.

Gender as a moderator

The role of gender in moderating the POP–OW relationship is crucial, especially in the male-dominated CI (Norberg and Johansson, 2021). Research suggests that POP may adversely affect women due to societal expectations, gender stereotypes, and potential discrimination (Eagly and Karau, 2002; Landells and Albrecht, 2019). Snipes, et al. (2023) found in a recent study that female employees’ job satisfaction is significantly impacted by political actions compared to their male counterparts. This heightened sensitivity to perceived injustice can lead to stronger withdrawal behaviors among women, particularly psychological withdrawal, as a coping mechanism in response to perceived inequities (Vigoda, 2002; Sabo Bello, et al., 2021). Moreover, the greater perceived costs of changing jobs in male-dominated industries such as construction may encourage women to opt for psychological rather than physical withdrawal (Vigoda, 2002). It is important to comprehend these gender dynamics to create interventions to reduce this phenomenon’s negative effects on female employees in the CI.

Given these considerations, the following hypotheses are framed for the current study.

Hypothesis 3:

Null Hypothesis (H0): Gender does not significantly moderate the positive relationship between POP and PSW among construction professionals.

Alternate Hypothesis (H3): Gender significantly moderates the positive relationship between POP and PSW among construction professionals.

Hypothesis 4:

Null Hypothesis (H0): Gender does not significantly moderate the positive relationship between POP and PW among construction professionals.

Alternate Hypothesis (H4): Gender significantly moderates the positive relationship between POP and PW among construction professionals.

Theoretical support: equity theory of motivation

Adams’ equity theory of motivation (Adams, 1963), provides a framework for understanding the relationship between POP and OW. According to this theory, individuals evaluate fairness in the workplace by comparing what they contribute, such as effort and skill, with the rewards or recognition they receive, especially in relation to others (Adams, 1963; Griffeth and Gaertner, 2001). In environments where POP is prevalent, rewards and promotions may appear unmerited, disturbing this balance and violating fairness principles. Such perceived inequity can result in diminished job satisfaction, decreased productivity, and increased voluntary turnover (Greenberg, 1990; Snipes, et al., 2023). When employees perceive inequitable treatment, they may opt to disengage from their positions to cope with the resultant stress (Adams, 1963, 1965). Griffeth and Gaertner (2001) emphasize that employees’ perceptions of equity substantially impact their job satisfaction and turnover intentions, which further supports the relevance of equity theory in the comprehension of withdrawal behaviors in politicized work environments.

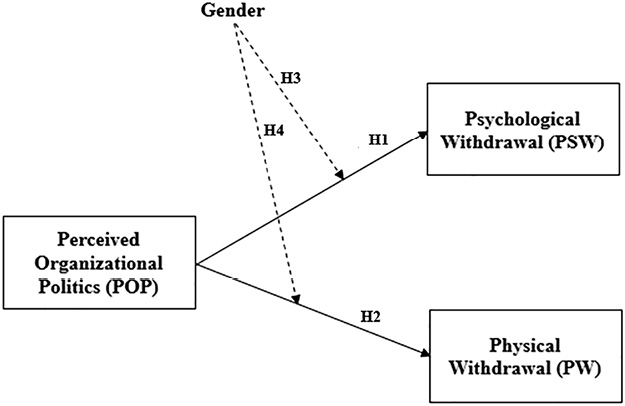

Figure 1 depicts the conceptual model, which proposes that POP, the independent variable, impacts the withdrawal dimensions PSW and PW, the dependent variables. Hypotheses H1 and H2 propose that POP positively influences PSW and PW. Additionally, the model introduces gender as a moderating variable. Hypotheses H3 and H4 examine the interaction effects of gender in the relations of POP and each of the two withdrawal dimensions. The conceptual framework provides a clear perspective on the direct and moderated relationships among variables.

Methodology

The study employed a quantitative survey methodology to collect data from full-time construction professionals in private construction firms across India, covering on-site and office roles. A quantitative survey method was chosen as it allows for efficient data collection from large and diverse samples, enabling robust statistical analyses to uncover significant relationships (Adhikari and Timsina, 2024). This sample was selected to capture the diverse experiences of construction professionals and provide a comprehensive understanding of workplace dynamics across different roles. Full-time professionals, being directly influenced by organizational policies and workplace politics, were ideal respondents for investigating how POP influences OW dimensions. By including respondents regardless of their current involvement in withdrawal behaviors, the study ensured a broader and more inclusive understanding of the impact of POP on employees in the CI.

Survey instrument

Survey questionnaires are a valuable tool for systematically collecting data from diverse respondents. Within the field of construction management, these questionnaire surveys are particularly effective in capturing industry practitioners’ opinions and perspectives (Radzi, et al., 2024). The questionnaire is divided into two sections: the first assesses POP and OW dimensions, while the second collects demographic information of the respondents. POP is evaluated using 12 items from Kacmar and Ferris’s (1991) Perceptions of Organizational Politics Scale (POPS), covering GPB, GAGA, and PPP. The current study used the scale as a unidimensional measure, a method validated in several studies (Malik, et al., 2019; Riaz, Batool and Saad, 2019; Karim, et al., 2021). An example item from this scale is, “Sometimes it is easier to remain quiet than to fight the system”. Participants indicated their responses using a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 represented strong disagreement and 5 represented strong agreement.

OW dimensions, PSW and PW, were measured using the withdrawal behavior scale developed by Erdemli (2015). The scale consists of six PSW items and nine PW items, with responses ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). The items of the original scale were modified to fit the context of the CI. Sample items include “Being occupied with irrelevant things during working hours” and “Constantly checking the time”.

Sample and data collection

Snowball sampling, a nonprobability approach employed in construction management research, was used to acquire target samples through referrals (Prakash and Phadtare, 2018; Rastogi and Singla, 2023; Radzi, et al., 2024). Questionnaires were circulated to 400 professionals chosen through this method, and 318 responded, resulting in a 79.5% response rate above the average of 68% (Holtom, et al., 2022). The respondents represent a range of professional roles within the Indian CI, including senior project managers, engineering managers, project managers, site engineers, design engineers, detailing engineers, modelers, and quality control engineers. Hair, et al. (2021) recommend that a sample size of at least 150 is sufficient for models with up to seven constructs, each with more than three items. Therefore, the 318 responses were adequate for structural equation modeling.

Ethical considerations were addressed with approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee (EC No. 8776/IEC/2024). Respondents were informed about the purpose of the study, nature of the data, and intended use. The study adhered to the guidelines of Podsakoff, et al. (2012) to reduce common method bias (CMB) by assuring confidentiality, clarifying that no responses were correct or incorrect, and reverse-scoring specific items. Harman’s single-factor test indicated that CMB was not a significant issue, as a single factor accounted for only 32.5% of the variance below the 50% threshold (Podsakoff and Organ, 1986).

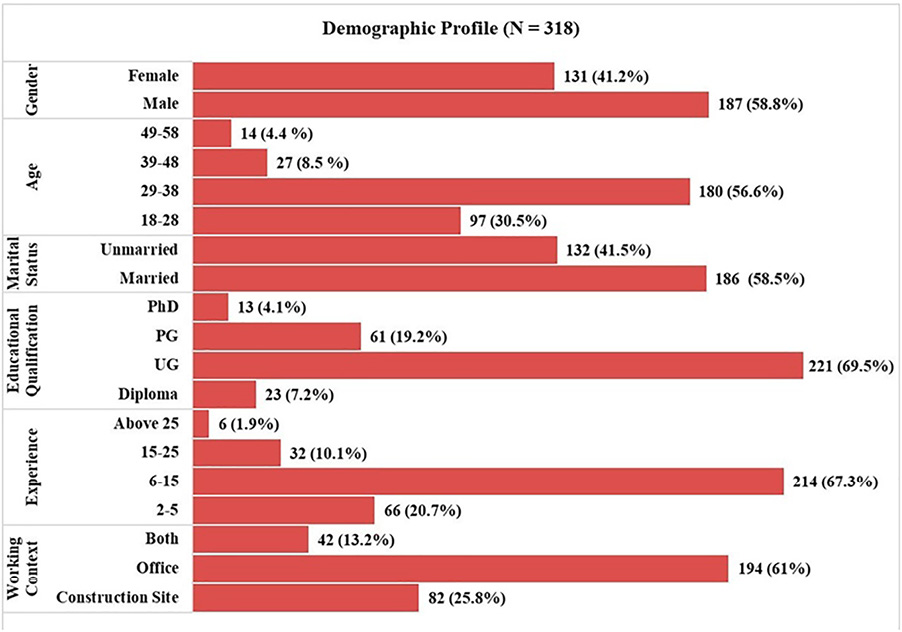

The demographic profile in Figure 2 shows a diverse sample with 58.8% male and 41.2% female. The majority, 56.6%, are aged 29–38, indicating experienced yet youthful professionals. Nearly 70% hold undergraduate degrees, highlighting an educated workforce.

Figure 2. Demographic profile of the respondents.

Analysis and results

The study utilized SPSS v23.0 for descriptive statistics and correlation analysis. SmartPLS 4.1.0.0 was used for instrument validation and hypothesis testing. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) is a statistical technique well-suited for complex models, which are characterized by multiple latent variables, a high number of observed indicators and moderating or mediating relationships. It applies particularly to studies with small to medium sample sizes, where conventional covariance-based SEM may be unsuitable (Akter, Fosso Wamba and Dewan, 2017). The conceptual model in this study is classified as complex due to the presence of three latent variables, POP, PSW, and PW, each of which is measured by multiple observed indicators, with gender as the moderating variable. Also, with a sample size of 318, PLS-SEM proved appropriate, as it can yield reliable results even with samples as low as 100 to 150 participants. It minimizes unexplained variance in dependent variables while maximizing explained variance from independent variables (Hair, et al., 2021). The PLS-SEM process involves two stages: assessing the measurement model and evaluating the structural model to analyze and interpret research findings.

Descriptive statistics and correlation matrix

The descriptive statistics, including the mean and standard deviation (SD) of the study variables and the correlation matrix between them, are presented in Table 1. The mean values for POP, PSW, and PW are 3.155, 2.586, and 2.268, respectively. The data reveal a strong positive correlation between POP and the withdrawal dimensions, PSW (r = 0.655, p < 0.01) and PW (r = 0.705, p < 0.01). This suggests that an increase in the level of POP is associated with an increase in both psychological and physical withdrawal behaviors. Moreover, a strong positive correlation exists between PSW and PW (r = 0.817, p < 0.01), suggesting that these two dimensions of withdrawal are closely interrelated.

| Variable | Mean | SD | POP | PSW | PW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POP | 3.155 | 0.741 | 1 | ||

| PSW | 2.586 | 0.624 | 0.655** | 1 | |

| PW | 2.268 | 0.652 | 0.705** | 0.817** | 1 |

Note: **correlation is significant at the 0.01 level.

Measurement model

The reliability and validity of the model’s items concerning their constructs were calculated and are shown in Table 2. All item loadings surpassed the threshold value of 0.6 (Chin, Gopal and Salisbury, 1997; Karim, et al., 2021). The composite reliability estimates (CR), average variance extracted values (AVE), and alpha coefficients (CA and rho_a) exceeded their respective threshold values of 0.7, 0.5, and 0.7 (Hair, et al., 2021). The uniqueness of the constructs was evaluated using discriminant validity, which was assessed through the heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT). The HTMT values between the constructs were below the maximum threshold value of 0.85 (Hair, et al., 2019), satisfying the criteria for discriminant validity.

Structural model

The study’s structural model was assessed using bootstrapping with 5,000 resamples to analyze path coefficients (β) and coefficient of determination (R²) (Hair, et al., 2021). The model fit indices indicated a good model fit, with the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) at 0.0748, the d_ULS at 0.628, the d_G at 0.944, and the normed fit index (NFI) at 0.984. These values align with established standards, wherein an SRMR below 0.08 and NFI above 0.90 indicate a good model fit (Henseler, et al., 2014).

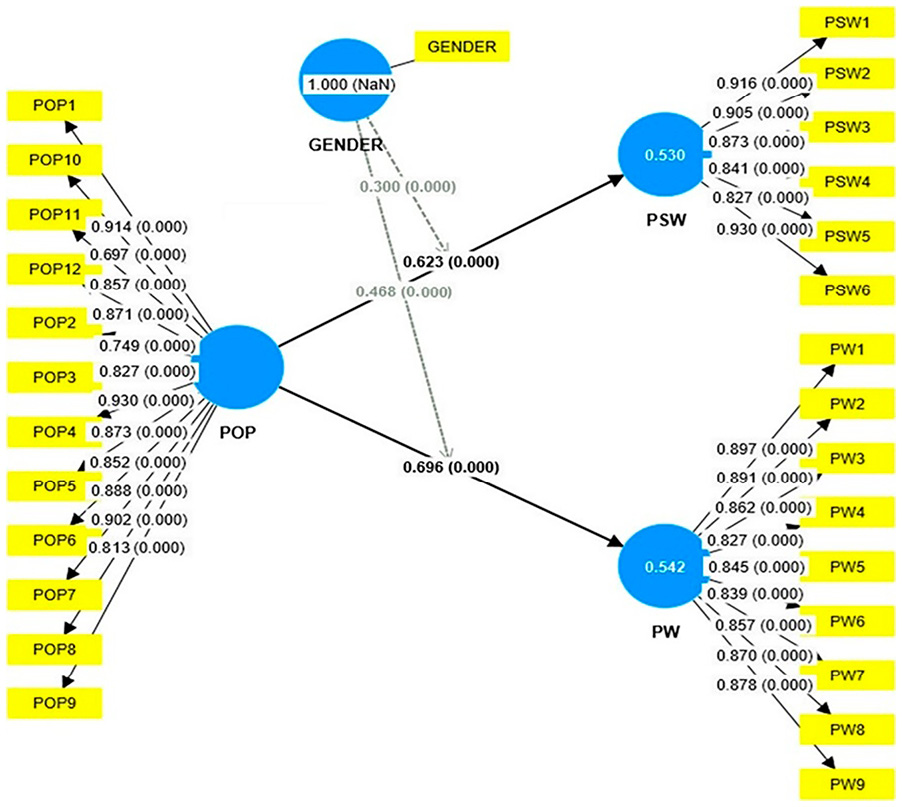

Table 3 indicates that the null hypotheses (H0) for H1 and H2 were rejected, whereas the alternate hypotheses were accepted. For H1, which tested the relationship between POP and PSW, the path coefficient (β) was 0.623 (T = 14.617, p < 0.01), indicating a significant positive association. For H2, which examined the relationship between POP and PW, the path coefficient was 0.696 (T = 16.903, p < 0.01), also showing a significant positive association. From the R² values of 0.530 and 0.542, POP explains 53.0% and 54.2% of the variation in PSW and PW, respectively. This significant variation shows the model’s strong explanatory power for these variables (Cohen, 1992). Further, the large effect sizes (f ²) of these paths, 0.522 and 0.668 (Cohen, 1992), confirm the significant impact of POP on both PSW and PW.

Note: **p-value significance at the 0.01 level.

Furthermore, hypotheses H3 and H4 explored the moderating role of gender on the relationship between POP–PSW and POP–PW, respectively. The null hypotheses (H0) for H3 and H4 were also rejected and the alternate hypotheses were accepted with significant path coefficients of 0.300 (T = 4.275, p < 0.01) and 0.468 (T = 6.493, p < 0.01), indicating that gender moderates the relationship between POP and PSW and POP and PW. The interaction effect of gender and POP on PSW yielded a medium effect size (f² = 0.136) (Cohen, 1992), indicating that this interaction explains a moderate amount of additional variance in PSW. The interaction effect of gender and POP on PW had a smaller effect size (f² = 0.091) (Cohen, 1992), suggesting a less pronounced but still significant moderating role of gender in the POP–PW relationship. The structural model in Figure 3 shows the path coefficients, their p-values, and the factor loadings of the indicators.

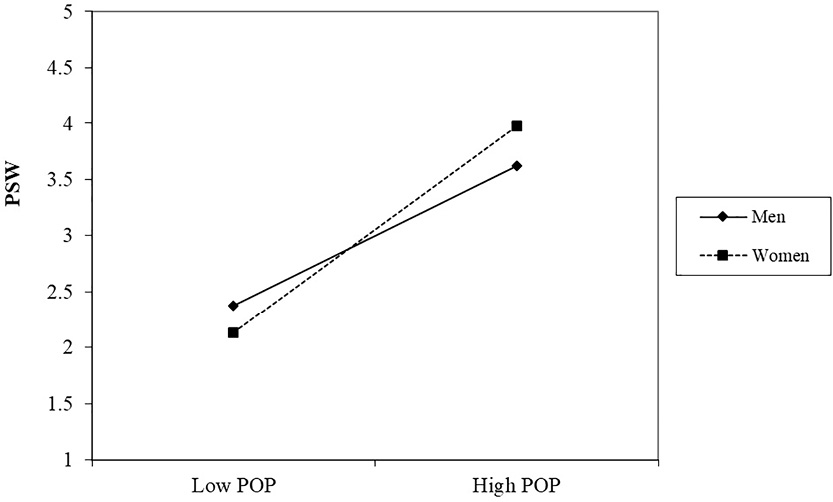

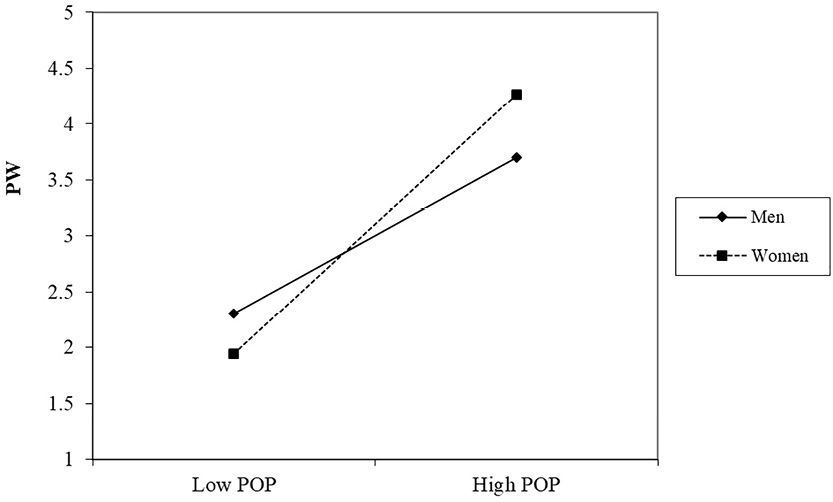

The slope analysis shown in Figures 4 and 5 was conducted using the recommendations by Aiken and West (1991) and Dawson (2014), where low POP refers to one standard deviation below the mean (-1 SD) and high POP refers to one standard deviation above the mean (+1 SD). The path coefficients of the indicators were used to perform the analysis. The study reveals that PSW and PW increase for both genders as the POP level increases from low to high, with a notably steeper rise for female professionals. This suggests that females are more sensitive to POP changes, highlighting gender-specific dynamics in CI where OP disproportionately affects women.

Figure 4. Moderation effect of gender on POP and PSW.

Figure 5. Moderation effect of gender on POP and PW.

Discussion

In the CI, characterized by hierarchical structures and traditionally male-dominated environments (Fielden, et al., 2000), the interplay of POP and its impact on OW represents a critical yet underexplored area of research. This study addresses this gap by investigating the influence of POP on OW among construction professionals such as project managers, site engineers, and design engineers, including both psychological and physical withdrawal behaviors, while also determining the moderating role of gender in these relationships.

Consistent with prior research (Ferris and Kacmar, 1992; Cropanzano, et al., 1997; Rosen, Levy and Hall, 2006; Chang, Rosen and Levy, 2009; Landells and Albrecht, 2019; Sabo Bello, et al., 2021), the current study supports the positive relationship between POP and both psychological and physical withdrawal behaviors. The acceptance of the alternate hypotheses of H1 and H2 underscores the significance of OP perceptions as a stressor contributing to psychological and physical withdrawal behaviors among construction professionals.

Drawing upon Adams’ equity theory of motivation (Adams, 1963), the study demonstrates that employees’ perceptions of OP generate feelings of unfairness and inequity, prompting them to resort to withdrawal behaviors as coping mechanisms (Griffeth and Gaertner, 2001; Lau and Scully, 2015). In construction, where project success often hinges on collaborative effort and trust (Soundarya, et al., 2024), POP can be especially destructive. When employees perceive that political maneuvering, rather than merit, dictates rewards and recognition, it breeds frustration and dissatisfaction (Vigoda, 2002), resulting in them withdrawing both psychologically and physically from the organization. PSW manifested through decreased motivation, commitment, and job satisfaction, can lead to reduced productivity and increased turnover intention (Kiazad, Seibert and Kraimer, 2014). Similarly, PW, such as absenteeism and tardiness, can occur when employees choose to physically disengage from the workplace to cope with the stress and negativity associated with OP (Cropanzano, et al., 1997). In construction, where tight deadlines and high-pressure environments are common, these behaviors can affect productivity, morale, and ultimately, project outcomes (AbouRizk, et al., 2010).

POP has the potential to negatively impact workplace equity by encouraging self-serving behaviors that are detrimental to peers within the CI. This may decrease employee engagement and increase employee withdrawal (Rughoobur-Seetah, 2022). When promotions or rewards are granted on political grounds without transparency, employees experience feelings of injustice, which diminishes their motivation and accelerates turnover rates. This political climate also exacerbates feelings of exclusion and disengagement by fostering the perception that management prioritizes certain individuals’ ideas or input (Atshan, et al., 2022).

Additionally, the study examined the potential influence of gender on the relationship between POP and OW, which is especially pertinent in the traditionally male-dominated CI. The findings confirmed that gender significantly influences the POP–PSW and POP–PW relationships (H3 and H4), with female professionals in the CI being more susceptible to the adverse effects of POP on their withdrawal dimensions. This is consistent with the existing literature indicating that women perceive OP as a masculine strategy that impedes their career advancement, exacerbating feelings of alienation and discouragement (Snipes, et al., 2023; Dhanasekar and Anandh, 2025). Numerous factors contribute to the increased susceptibility of female professionals to the adverse effects of POP. The impact of POP on women’s withdrawal behavior is exacerbated by the gender stereotypes and biases that are prevalent in the CI, which contribute to increased scrutiny, exclusion, and marginalization of women (Galea and Chappell, 2022). Furthermore, the perception of OP among female construction professionals is substantially enhanced by political maneuvering, resulting in biased promotions and rewards. This is worsened by the industry’s extant gender disparities, including the persistent pay gap and limited career advancement opportunities (Blau and Devaro, 2007). The lack of female representation and support networks in leadership positions increases feelings of powerlessness and disillusionment (Norberg and Johansson, 2021), thereby worsening the detrimental effects of POP on job satisfaction and commitment.

Furthermore, female professionals in the CI found themselves in a double bind due to societal norms that dictate varying expectations for men and women. Men are characterized by assertiveness and competition, whereas women are characterized by collaboration and nurturing (Dalton, 2019). The pressure to exhibit masculine traits to achieve career success while adhering to traditional feminine norms further increases women’s sensitivity to POP. This internal conflict between professional aspirations and societal expectations exacerbates the perceived inequity of OP, which ultimately results in disengagement from work through withdrawal behaviors.

Practical implications

The results of this study provide valuable guidance for policymakers and practitioners in the CI to mitigate the adverse effects of POP and reduce OW. To mitigate the detrimental effects of POP, organizations should prioritize transparency in their decision-making processes, guaranteeing that rewards and recognitions are equitable and based on objective performance indicators, including safety standards, client satisfaction, and project milestones. This can be accomplished by implementing transparent communication of performance criteria, regular feedback sessions, and anonymous surveys to assess employees’ perceptions of fairness. Managers must be consistent and equitable in their decision-making to mitigate the perceptions of bias and favoritism. Open communication channels, in which employees feel comfortable expressing their concerns without fear of retribution, can also mitigate the adverse effects of POP. Further, targeted interventions such as mentorship and leadership programs, especially for women, can help them traverse political environments. Diversity and inclusivity measures, such as leadership equity and diversity training, help balance power and develop a sense of belonging among all employees. These proactive initiatives can boost employee engagement, prevent withdrawal, and make the industry more sustainable and prosperous.

Limitations and future research directions

This study, while insightful, has limitations. The current study, centered on India’s CI, investigates the influence of gender on the relationship between POP and OW dimensions. However, its regional focus and cross-sectional design, which collects data at a single point in time, may limit the findings’ generalizability and causal interpretation. Future research could expand to diverse cultures and employ longitudinal designs that track changes in perceptions and behaviors over time for deeper insights. Moreover, while quantitative data provide valuable insights, qualitative methods like interviews could offer a richer and more comprehensive understanding. Additionally, the complex POP–OW relationship could be better understood by incorporating a multidimensional POP measure and additional demographic variables. This dynamic could be further elucidated by examining potential mediators such as job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

Conclusion

The current study illustrates the significant influence of POP on the behaviors of OW among construction professionals, with a more pronounced effect on female employees. These results indicate that addressing gender-specific vulnerabilities is vital to establishing a more inclusive and equitable work environment. The study not only confirms the negative impact of POP on psychological and physical withdrawal but also highlights the necessity of a gender-sensitive approach toward managing political climates. Organizations can mitigate the detrimental consequences of POP by cultivating open communication and setting up transparent, merit-based reward systems. Moreover, gender disparities can be mitigated through targeted mentorship and leadership programs designed for female professionals. Thus, this study promotes proactive organizational interventions that mitigate employee withdrawal and improve overall productivity and gender equity in the construction industry.

References

Abbas, M., Raja, U., Darr, W. and Bouckenooghe, D. (2014) ‘Combined Effects of Perceived Politics and Psychological Capital on Job Satisfaction, Turnover Intentions, and Performance’, Journal of Management, 40(7), pp. 1813–1830. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206312455243

Abdolmaleki, G., Naismith, N., Ghodrati, N., Poshdar, M. and Babaeian Jelodar, M. (2024) ‘An analysis of the literature on construction employee turnover: drivers, consequences, and future direction’, Construction Management and Economics, 42(9), pp. 822–846. https://doi.org/10.1080/01446193.2024.2337084

AbouRizk, H., Lee, S., Gellatly, I.R. and Fayek, A.R. (2010) ‘Understanding Withdrawal Behavior in the Construction Industry’, in Construction Research Congress 2010. Reston, VA: American Society of Civil Engineers, pp. 809–816. https://doi.org/10.1061/41109(373)81

Adams, J.S. (1963) ‘Towards an understanding of inequity’, Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67(5), pp. 422–436. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0040968

Adams, J.S. (1965) Inequity In Social Exchange, Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Edited by L. Berkowitz. New York: Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60108-2

Adhikari, R. and Timsina, T.P. (2024) ‘An Educational Study Focused on the Application of Mixed Method Approach as a Research Method’, OCEM Journal of Management, Technology & Social Sciences, 3(1), pp. 94–109. https://doi.org/10.3126/ocemjmtss.v3i1.62229

Aggarwal, A., Chand, P.K., Jhamb, D. and Mittal, A. (2020) ‘Leader–Member Exchange, Work Engagement, and Psychological Withdrawal Behavior: The Mediating Role of Psychological Empowerment’, Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00423

Aiken, L.S. and West, S.G. (1991) ‘Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions.’, Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA, US: Sage Publications, Inc, pp. xi, 212–xi, 212.

Akter, S., Fosso Wamba, S. and Dewan, S. (2017) ‘Why PLS-SEM is suitable for complex modelling? An empirical illustration in big data analytics quality’, Production Planning & Control, 28(11–12), pp. 1011–1021. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2016.1267411

Alexander, J.F. (2016) Mitigating the effects of withdrawal behavior on organizations. Available at: https://proquest.com

Anandh, K.S., Gunasekaran, K. and Mannan, M.A. (2020) ‘Investigation on The Factors Affecting Lifestyle of Professionals in The Construction Industries (Kerala and Tamil Nadu)’, International Journal of Integrated Engineering, 12(9). https://doi.org/10.30880/ijie.2020.12.09.029

Asrar-ul-Haq, M., Ali, H.Y., Anwar, S., Iqbal, A., Iqbal, M.B., Suleman, N., Sadiq, I. and Haris-ul-Mahasbi, M. (2019) ‘Impact of organizational politics on employee work outcomes in higher education institutions of Pakistan: Moderating role of social capital’, South Asian Journal of Business Studies, 8(2), pp. 185–200. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAJBS-07-2018-0086

Atshan, N.A., Al‐Abrrow, H., Abdullah, H.O., Khaw, K.W., Alnoor, A. and Abbas, S. (2022) ‘The effect of perceived organizational politics on responses to job dissatisfaction: The moderating roles of self‐efficacy and political skill’, Global Business and Organizational Excellence, 41(2), pp. 43–54. https://doi.org/10.1002/joe.22141

Beehr, T.A. and Gupta, N. (1978) ‘A note on the structure of employee withdrawal’, Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 21(1), pp. 73–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-5073(78)90040-5

Blau, F.D. and Devaro, J. (2007) ‘New Evidence on Gender Differences in Promotion Rates: An Empirical Analysis of a Sample of New Hires’, Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, 46(3), pp. 511–550. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-232X.2007.00479.x

Brunetto, Y., Teo, S.T.T., Shacklock, K. and Farr‐Wharton, R. (2012) ‘Emotional intelligence, job satisfaction, well‐being and engagement: explaining organisational commitment and turnover intentions in policing’, Human Resource Management Journal, 22(4), pp. 428–441. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-8583.2012.00198.x

Burakova, M., McDowall, A. and Bianvet, C. (2022) ‘Are organisational politics responsible for turnover intention in French Firefighters?’, European Review of Applied Psychology, 72(5), p. 100764. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erap.2022.100764

Chang, C.H., Rosen, C. and Levy, P. (2009) ‘The relationship between perceptions of organizational politics and employee attitudes, strain, and behavior: A meta-analytic examination’, Academy of Management Journal, 52(4), pp. 779–801. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2009.43670894

Chin, W.W., Gopal, A. and Salisbury, W.D. (1997) ‘Advancing the Theory of Adaptive Structuration: The Development of a Scale to Measure Faithfulness of Appropriation’, Information Systems Research, 8(4), pp. 342–367. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.8.4.342

Cho, H.-T. and Yang, J.-S. (2018) ‘How perceptions of organizational politics influence self-determined motivation: The mediating role of work mood’, Asia Pacific Management Review, 23(1), pp. 60–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmrv.2017.05.003

De Clercq, D., Khan, M.A. and Haq, I.U. (2023) ‘Perceived organizational politics and turnover intentions: critical roles of social adaptive behavior and emotional regulation skills’, Journal of Management & Organization, 29(2), pp. 247–265. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2021.26

Cohen, J. (1992) ‘A power primer.’, Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), pp. 155–159. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155

Cropanzano, R., Howes, J.C., Grandey, A.A. and Toth, P. (1997) ‘The relationship of organizational politics and support to work behaviors, attitudes, and stress’, Journal of Organizational Behavior, 18(2), pp. 159–180. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379(199703)18:2<159::AID-JOB795>3.0.CO;2-D

Dalton, D. (2019) How double bind bias impacts women leaders. Available at: https://3plusinternational.com/2019/08/how-double-bind-bias-imapcts-women-leaders/ (Accessed: 20 July 2024)

Dawson, J.F. (2014) ‘Moderation in Management Research: What, Why, When, and How’, Journal of Business and Psychology, 29(1), pp. 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-013-9308-7

Dhanasekar, Y. and Anandh, K.S. (2025) ‘Deciphering the role of age and gender in perceiving organizational politics in construction’, Built Environment Project and Asset Management, ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/BEPAM-01-2024-0011

Dhanasekar, Y., Anandh, K.S. and Szóstak, M. (2023) ‘Development of the Diversity Concept for the Construction Sector: A Bibliometric Analysis’, Sustainability, 15(21), p. 15424. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115424

Eagly, A.H. and Karau, S.J. (2002) ‘Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders.’, Psychological Review, 109(3), pp. 573–598. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.109.3.573

Edison, J.C. (2020) ‘Infrastructure Development and Construction Management’, Infrastructure Development and Construction Management [Preprint]. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781003055624

Erdemli, Ö. (2015) ‘Teachers’ Withdrawal Behaviors and their Relationship with Work Ethic’, Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 15(60), pp. 201–220. https://doi.org/10.14689/ejer.2015.60.12

Ferris, G.R., Harris, J.N., Russell, Z.A. and Maher, L.P. (1989) ‘Politics in Organizations’, in R.A. Giacalone and P. Rosenfeld (eds) Impression management in the organization, pp. 143–170. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473914957.n21

Ferris, G.R. and Kacmar, K.M. (1992) ‘Perceptions of organizational politics’, Journal of Management, 18(1), pp. 93–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639201800107

Ferris, G.R. and Treadway, D.C. (2012) ‘Politics in organizations: Theory and research considerations’, Politics in Organizations: Theory and Research Considerations, pp. 1–656. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203197424

Fielden, S.L., Davidson, M.J., Gale, A.W. and Davey, C.L. (2000) ‘Women in construction: The untapped resource’, Construction Management and Economics, 18(1), pp. 113–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/014461900371004

Galea, N. and Chappell, L. (2022) ‘Male‐dominated workplaces and the power of masculine privilege: A comparison of the Australian political and construction sectors’, Gender, Work & Organization, 29(5), pp. 1692–1711. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12639

Goo, W., Choi, Y. and Choi, W. (2019) ‘Coworkers’ organizational citizenship behaviors and employees’ work attitudes: The moderating roles of perceptions of organizational politics and task interdependence’, Journal of Management & Organization, 28(5), pp. 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2019.26

Greenberg, J. (1990) ‘Employee theft as a reaction to underpayment inequity: The hidden cost of pay cuts’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 75, pp. 561–568. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315193854-6

Griffeth, R.W. and Gaertner, S. (2001) ‘A Role for Equity Theory in the Turnover Process: An Empirical Test.’, Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 31(5), pp. 1017–1037. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2001.tb02660.x

Hair, J.F., Hult, G.T.M., Ringle, C.M. and Sarstedt, M. (2021) A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling. 2nd edn. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications Inc. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-80519-7

Hair, J.F., Risher, J.J., Sarstedt, M. and Ringle, C.M. (2019) ‘When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM’, European Business Review, 31(1), pp. 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

Hanisch, K.A. and Hulin, C.L. (1990) ‘Job attitudes and organizational withdrawal: An examination of retirement and other voluntary withdrawal behaviors’, Journal of Vocational Behavior, 37(1), pp. 60–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-8791(90)90007-O

Hansen, J. (2024) Understanding Employee Turnover Rates (And How to Improve Them). Available at: https://www.award.co/blog/employee-turnover-rates (Accessed: 21 February 2024).

Harris, R.B., Harris, K.J. and Harvey, P. (2007) ‘A Test of Competing Models of the Relationships Among Perceptions of Organizational Politics, Perceived Organizational Support, and Individual Outcomes’, The Journal of Social Psychology, 147(6), pp. 631–656. https://doi.org/10.3200/SOCP.147.6.631-656

Henseler, J., Dijkstra, T.K., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C.M., Diamantopoulos, A., Straub, D.W., Ketchen, D.J., Hair, J.F., Hult, G.T.M. and Calantone, R.J. (2014) ‘Common Beliefs and Reality About PLS’, Organizational Research Methods, 17(2), pp. 182–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428114526928

Holtom, B., Baruch, Y., Aguinis, H. and A Ballinger, G. (2022) ‘Survey response rates: Trends and a validity assessment framework’, Human Relations, 75(8), pp. 1560–1584. https://doi.org/10.1177/00187267211070769

Jeong, Y. and Kim, M. (2022) ‘Effects of perceived organizational support and perceived organizational politics on organizational performance: Mediating role of differential treatment’, Asia Pacific Management Review, 27(3), pp. 190–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmrv.2021.08.002

Kacmar, K.M. and Carlson, D.S. (1997) ‘Further validation of the perceptions of politics scale (pops): A multiple sample investigation’, Journal of Management, 23(5), pp. 627–658. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639702300502

Kacmar, K.M. and Ferris, G.R. (1991) ‘Perceptions of Organizational Politics Scale (POPS): Development and Construct Validation’, Educational and Psychological Measurement, 51(1), pp. 193–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164491511019

Kanungo, R.N. and Mendonca, M. (2002) ‘Employee Withdrawal Behavior’, in, pp. 71–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-0599-0_4

Karatepe, O.M. (2013) ‘Perceptions of organizational politics and hotel employee outcomes’, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 25(1), pp. 82–104. https://doi.org/10.1108/09596111311290237

Karim, D.N., Abdul Majid, A.H., Omar, K. and Aburumman, O.J. (2021) ‘The mediating effect of interpersonal distrust on the relationship between perceived organizational politics and workplace ostracism in higher education institutions’, Heliyon, 7(6), p. e07280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07280

Kaur, N. and Kang, L.S. (2023) ‘Perception of organizational politics, knowledge hiding and organizational citizenship behavior: the moderating effect of political skill’, Personnel Review, 52(3), pp. 649–670. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-08-2020-0607

Khalid, S., Hashmi, H.B.A., Abbass, K., Ahmad, B., Khan Niazi, A.A. and Achim, M.V. (2022) ‘Unlocking the Effect of Supervisor Incivility on Work Withdrawal Behavior: Conservation of Resource Perspective’, Frontiers in Psychology, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.887352

Kiazad, K., Seibert, S.E. and Kraimer, M.L. (2014) ‘Psychological contract breach and employee innovation: A conservation of resources perspective’, Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 87(3), pp. 535–556. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12062

Laczo, R.M. and Hanisch, K.A. (1999) ‘An Examination of Behavioral Families of Organizational Withdrawal in Volunteer Workers and Paid Employees’, Human Resource Management Review, 9(4), pp. 453–477. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-4822(99)00029-7

Landells, E.M. and Albrecht, S.L. (2019) ‘Perceived Organizational Politics, Engagement, and Stress: The Mediating Influence of Meaningful Work’, Frontiers in Psychology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01612

Lau, C.M. and Scully, G. (2015) ‘The roles of organizational politics and fairness in the relationship between performance management systems and trust’, Behavioral Research in Accounting, 27(1), pp. 25–53. https://doi.org/10.2308/bria-51055

Lehman, W.E.K. and Simpson, D.D. (1992) ‘Employee Substance Use and On-the-Job Behaviors’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 77(3), pp. 309–321. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.77.3.309

Malik, O.F., Shahzad, A., Raziq, M.M., Khan, M.M., Yusaf, S. and Khan, A. (2019) ‘Perceptions of organizational politics, knowledge hiding, and employee creativity: The moderating role of professional commitment’, Personality and Individual Differences, 142, pp. 232–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.05.005

Meisler, G. (2022) ‘Fear and emotional abilities in public organizations: a sectorial comparison of their influence on employees’ well-being’, International Public Management Journal, 25(4), pp. 544–565. https://doi.org/10.1080/10967494.2020.1720051

Meisler, G., Drory, A. and Vigoda-Gadot, E. (2020) ‘Perceived organizational politics and counterproductive work behavior: The mediating role of hostility’, Personnel Review, 49(8), pp. 1505–1517. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-12-2017-0392

Mintzberg, H. (1983) Power in and around organizations. Prentice Hall.

Mirsepasi, N., Memarzadeh, G., Alipour, H. and Feizi, M. (2012) ‘Citizenship and Withdrawal Behaviors in Contingency Cultures’, Journal of Basic and Applied Scientific Research, 2(9), pp. 9398–9406. Available at: www.textroad.com

Morello, A., Issa, R.R.A. and Franz, B. (2018) ‘Exploratory Study of Recruitment and Retention of Women in the Construction Industry’, Journal of Professional Issues in Engineering Education and Practice, 144(2). https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)EI.1943-5541.0000359

Newman, A., Le, H., North-Samardzic, A. and Cohen, M. (2020) ‘Moral Disengagement at Work: A Review and Research Agenda’, Journal of Business Ethics, 167(3), pp. 535–570. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04173-0

Norberg, C. and Johansson, M. (2021) ‘“Women and ‘Ideal’ Women”: The Representation of Women in the Construction Industry’, Gender Issues, 38(1), pp. 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12147-020-09257-0

Park, J.H., Newman, A., Zhang, L., Wu, C. and Hooke, A. (2016) ‘Mentoring functions and turnover intention: the mediating role of perceived organizational support’, The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 27(11), pp. 1173–1191. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2015.1062038

Pathan, S.S. and Vinay, R. (2021) ‘Employee Turnover and Attrition in India: An Overview’, Allana Management Journal of Research, Pune, 11, pp. 19–21.

Peng, P. and Li, X. (2023) ‘The hidden costs of emotional labor on withdrawal behavior: the mediating role of emotional exhaustion, and the moderating effect of mindfulness’, BMC Psychology, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01392-z

Pepple, D.G., Akinsowon, P. and Oyelere, M. (2023) ‘Employee Commitment and Turnover Intention: Perspectives from the Nigerian Public Sector’, Public Organization Review, 23(2), pp. 739–757. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-021-00577-7

Podsakoff, P.M., MacKenzie, S.B. and Podsakoff, N.P. (2012) ‘Sources of Method Bias in Social Science Research and Recommendations on How to Control It’, Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), pp. 539–569. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

Podsakoff, P.M. and Organ, D.W. (1986) ‘Self-Reports in Organizational Research: Problems and Prospects’, Journal of Management, 12(4), pp. 531–544. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920638601200408

Prakash, A. and Phadtare, M. (2018) ‘Service quality for architects: scale development and validation’, Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 25(5), pp. 670–686. https://doi.org/10.1108/ECAM-03-2017-0046

Radzi, A.R., K. S., A., Alias, A.R., Algahtany, M. and Rahman, R.A. (2024) ‘Modeling the factors affecting workplace well-being at construction sites: a cross-regional multigroup analysis’, Journal of Engineering, Design and Technology [Preprint]. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEDT-07-2023-0322

Rajprasad, J., Thamilarasu, V. and Mageshwari, N. (2018) ‘Role of Crisis Management in Construction Projects’, International Journal of Engineering and Technology(UAE), 7, pp. 451–453. https://doi.org/10.14419/ijet.v7i2.12.11515

Rashid, M.A., Islam, T. and Ahmer, Z. (2019) ‘How organizational politics impact workers job related outcomes?’, Journal of Political Studies, 26(1), p. 205.

Rastogi, A. and Singla, H.K. (2023) ‘Exploration of exhaustion in early-career construction professionals in India’, Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management [Preprint]. https://doi.org/10.1108/ECAM-10-2022-0938

Riaz, A., Batool, S. and Saad, M.S.M. (2019) ‘The missing link between high performance work practices and perceived organizational politics’, Revista de Administração de Empresas, 59(2), pp. 82–94. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0034-759020190202

Rosen, C.C., Levy, P.E. and Hall, R.J. (2006) ‘Placing perceptions of politics in the context of the feedback environment, employee attitudes, and job performance.’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(1), pp. 211–220. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.1.211

Rughoobur-Seetah, D.S. (2022) ‘Assessing the Outcomes of Organizational Politics on Employees Work Behaviors’, Journal of African Business, 23(3), pp. 676–693. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228916.2021.1910785

Sabo Bello, M., Gaji, A.A., Madaki, A.A. and Hussaini, I. (2021) ‘Antecedents of Perceived Organisational Politics and Psychological Withdrawal’, Original Research Article [Preprint], (August). https://doi.org/10.36349/easjebm.2021.v04i07.001

Sexton, C. and Zhang, J. (2022) ‘Reducing Harassment for Women in the Professional Construction Workplace with Zero- Tolerance and Interventionist Policies’, Construction Research Congress 2022: Health and Safety, Workforce, and Education - Selected Papers from Construction Research Congress 2022, 4-D(5), pp. 376–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/01446193.2016.1277026

Singh, S. and Randhawa, G. (2022) ‘Do perceptions of organizational politics influence turnover intentions? Organizational cynicism as a potential mediator’, Development and Learning in Organizations: An International Journal, 36(1), pp. 8–10. https://doi.org/10.1108/DLO-02-2021-0025

Snipes, R.L., Pitts, J.P., Bryant, P.C., Huning, T.M. and Snipes, A. (2023) ‘Job Satisfaction and Politics in the Modern Workplace: An Empirical Examination of the Moderating Effects of Gender and Age on the Perception of Organizational Politics-Job Satisfaction Relationship’, Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal [Preprint]. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10672-023-09449-2

Soundarya, S.P., K.S, A., Rajendran, S. and Sen, K.N. (2024) ‘The role of psychological contract in enhancing safety climate and safety behavior in the construction industry’, Journal of Engineering, Design and Technology [Preprint]. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEDT-07-2023-0315

Spendolini, M.J. (1985) Employee withdrawal behavior: Expanding the concept (Turnover, Absenteeism). University of California, Irvine.

Ullah, S., Hasnain, S.A., Khalid, A. and Aslam, A. (2019) ‘Effects of Perception of Organizational Politics on Employee’s Well-Being: The Mediating Role of Trust and Interpersonal Conflicts’, European Online Journal of Natural and Social Sciences, 8(1), pp. 1–14. Available at: http://european-science.com/eojnss_proc/article/view/5637

Vigoda, E. (2000) ‘Organizational Politics, Job Attitudes, and Work Outcomes: Exploration and Implications for the Public Sector’, Journal of Vocational Behavior, 57(3), pp. 326–347. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1999.1742

Vigoda, E. (2002) ‘Stress-related aftermaths to workplace politics: The relationships among politics, job distress, and aggressive behavior in organizations’, Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23(5), pp. 571–591. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.160

Zhang, J., Su, D., Smith, A.P. and Yang, L. (2023) ‘Reducing Work Withdrawal Behaviors When Faced with Work Obstacles: A Three-Way Interaction Model’, Behavioral Sciences, 13(11), p. 908. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13110908