Construction Economics and Building

Vol. 25, No. 3/4

December 2025

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Procurement Integrity: Best Practices for PPP Projects in Iraq and Malaysia

Mundher Mohammed Alsamarraie1, Omar Sedeeq Yousif2,*, Farid Ezanee Mohamed Ghazali1

1 School of Civil Engineering, Engineering Campus, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, Malaysia

2 Department of Building Engineering and Projects Management, Al-Noor University, Nineveh, 41002, Iraq

Corresponding author: Omar Sedeeq Yousif, Department of Building Engineering and Projects Management, Al-Noor University, Nineveh, 41002, Iraq, omar.ameen93@gmail.com

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v25i3/4.9329

Article History: Received 06/09/2024; Revised 26/06/2025; Accepted 18/07/2025; Published 05/12/2025

Citation: Alsamarraie, M. M., Yousif, O. S., Ghazali, F. E. M. 2025. Procurement Integrity: Best Practices for PPP Projects in Iraq and Malaysia. Construction Economics and Building, 25:3/4,289–310. https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v25i3/4.9329

Abstract

The construction sector has undergone significant evolution with the widespread adoption of public–private partnership (PPP) models in various countries. The appeal of PPP lies in its ability to balance risk, improve efficiency through strategic bundling or unbundling of responsibilities, and enhance access to affordable private financing. For emerging economies such as Iraq, examining the experiences of more advanced implementers like Malaysia is essential to adapt best practices and avoid common pitfalls. This research employed a systematic literature review, using predefined inclusion criteria that focus on policy documents, empirical case studies, and peer-reviewed articles from 2000 to 2024, sourced from Scopus, Web of Science, and governmental databases. The comparison between Iraq and Malaysia is guided by key performance indicators, including risk allocation, regulatory frameworks, private sector participation, and institutional readiness. The findings reveal stark contrasts in governance structures, policy consistency, and institutional capacity that influence PPP outcomes. While Malaysia demonstrates a mature, centralised framework with proactive private engagement, Iraq exhibits fragmented governance, regulatory gaps, and a cautious policy environment. These results highlight the importance of legal reform, capacity building, and investment incentives in the Iraqi context. Theoretically, the study contributes to the literature by framing a context-sensitive model of PPP readiness for emerging economies, integrating institutional theory with procurement practice. The implications emphasise the need for Iraq to strategically enhance its legal and institutional frameworks, stimulate private sector confidence, and adopt adaptable PPP models to foster sustainable infrastructure development.

Keywords

Public–Private Partnership; Procurement; Developing Countries; Institutional Capacity; Governance

Introduction

The construction industry remains one of the most resistant to technological advancement, facing persistent challenges such as fragmented processes, limited collaboration, and outdated procurement methods (Li, Greenwood, and Kassem, 2019; Chan and Owusu, 2022; Alsamarraie and Ghazali, 2023c). Despite recent initiatives promoting digital transformation (Yousif et al., 2024), progress has been slow. In this context, public–private partnerships (PPPs) have emerged as a strategic response to infrastructure demands, particularly in countries grappling with fiscal constraints. PPPs allow governments to harness private sector capital, expertise, and efficiency while sharing project risks and responsibilities (Endo and Seetharam, 2021).

Globally, PPPs have gained traction as a viable model for delivering public infrastructure. Malaysia stands out for its structured and successful PPP projects, including light rail systems, expressways, hospitals, schools, and special economic zones (Hashim, Che-Ani, and Ismail, 2017). In contrast, Iraq has struggled to implement PPPs effectively despite formal policy endorsements. Key impediments include entrenched corruption, weak institutional capacity, inadequate legal frameworks, and a lack of stakeholder trust (Alsamarraie and Ghazali, 2023c). These issues are not solely administrative; they reflect broader systemic limitations that inhibit the development of a functional PPP ecosystem.

Although individual studies have addressed PPP challenges in either Iraq or Malaysia, comparative research remains limited. Few studies have systematically analysed how institutional maturity, governance quality, and risk management frameworks influence PPP outcomes across differing national contexts. To fill this gap, the current study employed a comparative analytical framework focused on three interrelated dimensions: institutional readiness, risk allocation strategies, and procedural transparency. This framework provides a structured lens through which to examine the divergence in PPP practices and outcomes between a developing country like Iraq and an emerging economy like Malaysia.

The objective of this study was to evaluate and compare the procurement approaches, risk landscapes, and implementation mechanisms of PPPs in Iraq and Malaysia. Through this comparison, the study aimed to extract actionable insights that can guide policy reform, reduce implementation barriers, and foster more transparent and resilient PPP models—particularly in post-conflict or resource-constrained environments.

The methodology is based on a structured literature review, synthesising findings from peer-reviewed studies, government reports, and institutional frameworks. To ensure a rigorous and systematic review, sources were retrieved from academic databases such as Scopus, Web of Science, and relevant governmental portals. The review focused on studies published between 2000 and 2024, with priority given to peer-reviewed journal articles, empirical case studies, and official policy documents related to PPP performance in Iraq and Malaysia. Studies were included based on their relevance to institutional theory, procurement frameworks, and risk assessment in PPPs, while non-English sources, studies without clear methodological grounding, or those with duplicated findings were excluded. A thematic analysis was conducted to categorise barriers and risks into six key domains. Secondary data triangulation enhanced the reliability of the findings. Furthermore, internationally recognised PPP performance models were reviewed and used as benchmarks to evaluate the two countries’ frameworks. Comparative insights were visualised through tables and diagrams to support clarity. By aligning with international standards such as those set by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the study contributes to the broader discourse on PPP reform, offering practical guidance for developing and emerging economies seeking to enhance infrastructure delivery through effective public–private collaboration.

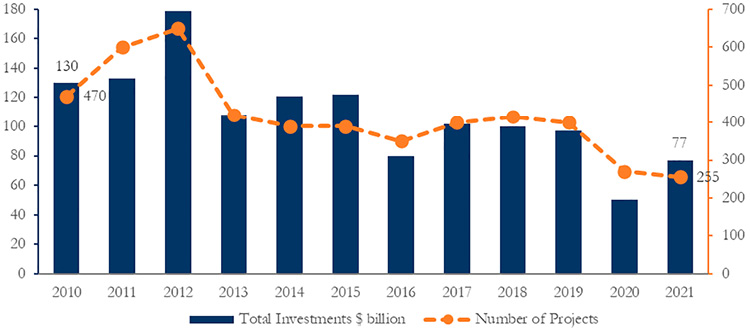

PPP world trend

In many countries, PPP has increased dramatically over the past three decades concerning the volume of contracts and investments (Rosell and Saz-Carranza, 2020). PPP has grown in favour especially concerning infrastructure projects because of the advantages they are anticipated to provide, including the accomplishment of projects on schedule and within budgetary constraints, the incorporation of private sector concepts to create innovative and excellent amenities, the combination effect’s ability to reduce the expenses associated with integration, and the ability to fill the funding shortage in facilities development by enlisting private funding (Endo and Seetharam, 2021). PPP is popular not just in affluent nations but also in emerging nations. More than 300 construction projects with private investment have been carried out annually in emerging economies since 2010, according to the “Private Participation in the Infrastructure (PPI)” Project directory of the World Bank, as illustrated in Figure 1. The average investment in the last 12 years was $108.25 billion across 417.5 projects, as shown in Figure 1. In the early 1990s, Latin America was the region with the fastest-growing PPP, which was accompanied by a period of prosperity in Southeast Asia, East Asia, and the Pacific region starting in the 2000s. In recent years, Latin America and Asia have been identified as key regions for PPP expansion in emerging nations. The PPP’s rise in these areas was not accidental; rather, development organisations promoted and instigated it (Bayliss and Van Waeyenberge, 2018). Developing organisations have responded to the interest of emerging nations in PPP by launching a wide variety of projects and programs.

Figure 1. Private infrastructure funding decisions in emerging nations, 2010–2021 (EPEC, 2022; WBG, 2022)

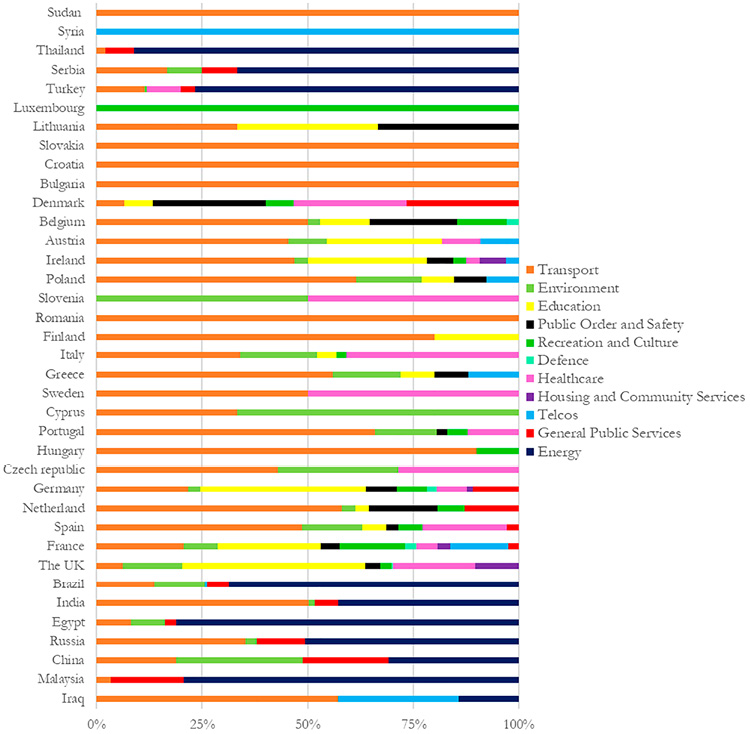

Nevertheless, despite the increased usage of PPP and the corresponding growth in their studies, there is still no definitive explanation of why and how authorities in different contexts establish distinct institutional frameworks, laws, and regulations for administering PPP. The global prevalence of PPP during the 1990s led to the identification of various governmental infrastructure initiatives, including the construction and renovation of highways, roads, tunnels, sewage treatment facilities, ports, airports, and sports arenas, as prime examples of PPP. According to the data from the World Bank Group and European PPP Expertise Centre 2022, the studies revealed that, in addition to transportation infrastructure initiatives, various service sectors, such as environmental protection, education, public safety and security, national defence, medical care, real estate, and the communications sector, have been implemented through PPP.

In Figure 2, it can be observed that the transportation industry proved to be the largest contributor when it comes to total PPP expenditures in European countries, as anticipated. It is noteworthy that the medical, educational, and environmental sectors exhibit a greater proportion of the total investment value of PPP in contrast to other industries. From a global standpoint, various nations across the Asian continent, Latin America, the Eastern Mediterranean region, and Africa have also undergone a comparable shift in governance toward PPP.

Figure 2. PPP industry structure worldwide (EPEC, 2022; WBG, 2022). PPP, public–private partnership

The PPI Project databases of the World Bank have documented more than 6,400 PPP projects across nearly 130 countries with low to middle income. The databases contain information regarding the quantity and monetary value of PPI projects, both collected and segmented by region or sector. Additionally, they document the historical fluctuations of these projects from 1990 to 2018 across six global regions, namely, East Asia and the Pacific, the European Union and Asia-Pacific, the Americas and the Caribbean, the Mediterranean region and Northern Africa, South Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa, as presented in Table 1.

Note: PPI, private participation in the infrastructure.

Based on the previously mentioned methods and descriptions of PPP, it may be inferred that PPP is being elucidated in varying manners by scholars. The fundamental underlying explanation of PPP has yet to be fully described and defined by any singular approach or dimension. In light of this, it is valuable to examine the conceptual priorities and identify shared characteristics inherent in the diverse definitions of PPP. Therefore, an examination of more than 2,000 scholarly works about PPP that have lately appeared in a variety of indexed journals was carried out. The key elements that are commonly associated with PPP are illustrated in Figure 3. To categorise diverse definitions of PPP as documented in the prior studies and analyse their root words, analytical software tools, namely, VOSviewer and Worditout, were employed. Figure 3 presents the precise and relative prevalence of the words through the utilisation of “word frequency queries” and the exportation of “word cloud visualisations”. It was discovered that “public”, “private”, “partnership”, “PPP”, “project management”, “risk assessment”, “investments”, “mergers and acquisitions”, “decision making”, “sustainable development”, and “infrastructure” are among the word groupings that are most commonly cited.

Figure 3. PPP output word cloud. PPP, public–private partnership

PPP is generally defined more broadly in the following ways: (1) the private and public sectors, (2) long-term implications, (3) government projects, (4) services and utility providers, (5) common risks and obligations, (6) legal connections, (7) partnerships, (8) joint venture, and (9) shared financing (Warsen, Klijn and Koppenjan, 2019; Casady et al., 2020).

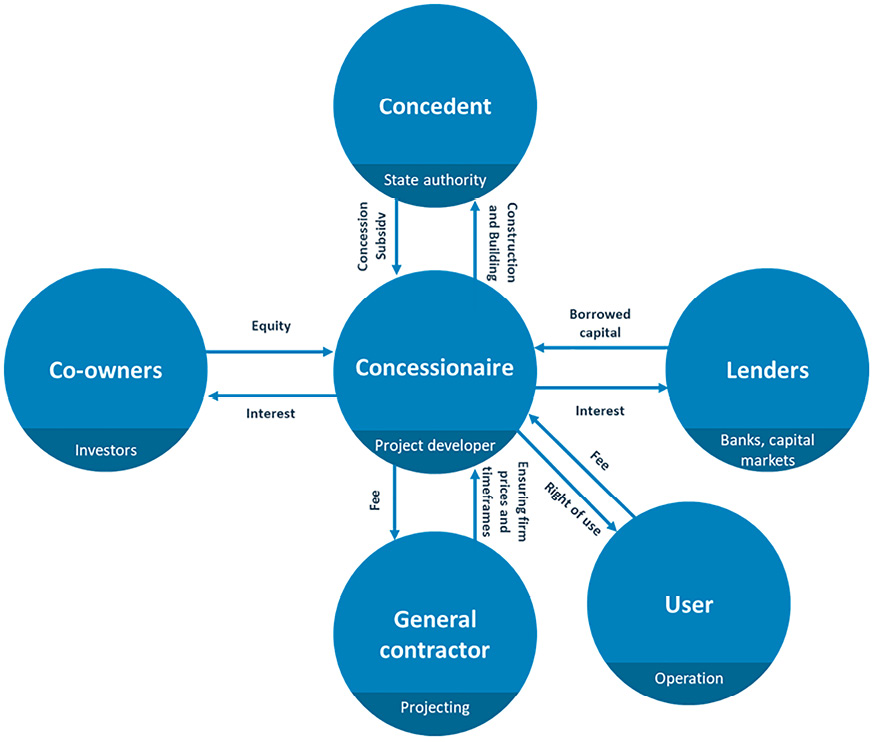

As previously stated, the intricacies of implementing collaboration between the governmental and private sectors are distinct and multifaceted. Therefore, a thorough examination of the interactions between the parties at various stages of the partnership project implementation is necessary. The conventional approach for PPP initiatives typically involves the primary partner engaging in a competitive bidding process to establish a contractual agreement with a private partner. Additionally, a distinct “direct agreement” is established between the primary partner and the lenders. It should be noted that a direct agreement refers to a legally binding contract that outlines the circumstances of interaction between two parties. In this scenario, the lending entities extend financial support to the private partner while securing their investment through the collateralisation of the partner’s assets, thereby ensuring the repayment of the financing. In addition, they engage in contractual arrangements with contractors designated by the private partner to undertake construction and upkeep activities. Figure 4 presents the primary stakeholders participating in a standard PPP initiative in Iraq and Malaysia, along with their respective motivations and obligations. The authors extracted Figure 4 from prior research findings.

Figure 4. Iraqi–Malaysian PPP model (authors’ compilation from earlier studies). PPP, public–private partnership

Public–private partnership model

Infrastructure projects are vital, as they are the backbone of countries, and they provide huge advantages for emerging nations. Unfortunately, the execution of this idea is frequently hampered in many nations by a lack of adequate resources and expertise within the government and public sector. PPP has emerged as a workable answer to this issue, allowing the private sector to contribute sufficient resources and expertise to infrastructure projects. Every government’s modernisation initiative currently relies heavily on the PPP idea, a reform in economic policy. The PPP model aids in bridging gaps in the effectiveness, efficiency, and speed of services provided by public bodies (Jayasuriya, Zhang, and Jing Yang, 2019).

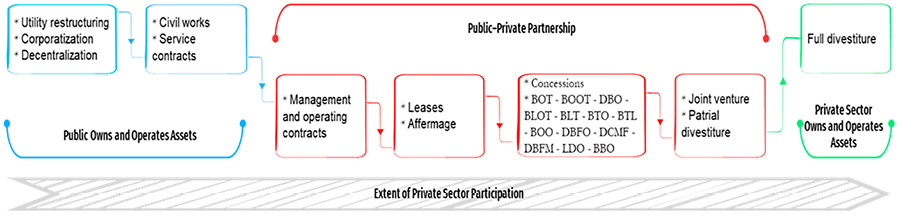

A PPP is a contract for the provision of services between the government and private entities or non-governmental organisations (NGOs) in exchange for a split of the venture’s risks and benefits. A government may work with a compatible company or an NGO under a PPP model to use its core competencies that enhance the capabilities of government institutions. PPP is a phrase that is frequently misused and used ambiguously. Overall, private participation may be restricted to a straightforward role in subcontracting, such as building projects and providing services (Ozorhon, Ozcan-Deniz, and Kir, 2021). However, a collaboration will only be classified as a PPP if the public and private parties have a well-defined risk-sharing agreement. Usually, the private investor shares most of the risk and uses experience and financial and technological assets to make a profit on its investment.

To improve the sustainability and financial viability of e-government projects, PPP is swiftly gaining popularity as an economic model. Depending on the requirements of a particular project, the government and the collaborating body may choose to collaborate in a variety of ways. There are several partnership models, most of which rely on the agreements that the government body and its collaborating body have made. Governments throughout the globe frequently utilise the paradigms “design-build-finance-operate” (DBFO), “build-transfer-operate”, “build-operate-transfer” (BOT), and “build-own-operate” (BOO) in their projects (Trebilcock and Rosenstock, 2015). The theory of privatisation (BOO), where the private proponent retains ownership of the asset upon the expiration date of the contract, is distinct from PPP. This viewpoint is shared by some scholars, while others hold differing opinions (Engel, Fischer, and Galetovic, 2013). PPP is classified into various kinds of contracts based on the respective responsibilities of the partnering entities involved in the implementation of projects, as illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5. PPP vs other arrangements (National Center for Public Private Partnership, 2019). PPP, public–private partnership

In PPP, the partnering entities work together to build up, finance, and operate a stand-alone business. The private body provides construction management, operation, and maintenance (Ozorhon, Ozcan-Deniz, and Kir, 2021). The project’s nature and several other elements have a role in the decision of which model to choose. Nevertheless, the overarching goal is to enable cooperative risk sharing and combine public sector responsibility with private sector efficiency (Dordevic and Rakic, 2020). In the past, governments have used PPP to contract with private bodies to provide services to fulfil one or more of the six roles depicted in Figure 6.

Figure 6. PPP functions (Abuzaineh, 2018). PPP, public–private partnership

Theoretical frameworks underpinning PPP implementation

• Value for money (VfM) in PPP procurement

A central justification for adopting PPPs lies in their potential to deliver VfM by optimising the balance between cost, quality, and risk over the project lifecycle. VfM is achieved when a PPP arrangement offers greater efficiency or better service outcomes than traditional public procurement models. This is typically assessed through tools such as the Public Sector Comparator or cost–benefit analysis frameworks, which evaluate whether private sector involvement leads to long-term economic gains for the public sector (Atmo and Duffield, 2014; Helby Petersen, 2019).

In the Malaysian context, formal mechanisms to evaluate VfM are more institutionalised, including performance-based output specifications, lifecycle costing, and transparent payment structures (Hashim, Che-Ani, and Ismail, 2017). Conversely, Iraq lacks formalised VfM assessment procedures, making it difficult to justify private investment or ensure accountability in PPP contracts. This absence of structured VfM frameworks contributes to inefficiencies and reduces investor confidence.

• Risk allocation and the PPP risk matrixEffective risk allocation is fundamental to PPP success. The PPP risk allocation matrix is a tool used to identify and assign specific risks—such as design, financial, operational, and political risks—to the party best positioned to manage them (Hwang, Zhao, and Gay, 2013; Loosemore and Malouf, 2019; Huque, 2021). In well-functioning PPP environments like Malaysia, risk is typically distributed through detailed contractual provisions, minimising ambiguity and dispute potential.

However, Iraq’s PPP arrangements often suffer from unclear or one-sided risk allocation, frequently placing a disproportionate burden on the public sector or failing to address potential risk events such as regulatory change, land acquisition delays, or payment guarantees. This undermines project bankability and discourages long-term private participation (Khudhaire and Naji, 2021; Alsamarraie and Ghazali, 2023b).

• Institutional theory and cross-national PPP performanceThe variation in PPP success across countries like Iraq and Malaysia can also be explained through institutional theory, which highlights how formal structures (laws, regulations, and governance mechanisms) and informal norms (trust, political culture, and stakeholder expectations) shape economic and policy outcomes (Quelin et al., 2019). For instance, Malaysia benefits from institutional maturity—evidenced by centralised PPP units, regulatory clarity, and sustained political support—allowing for more stable long-term engagement with private actors (Hashim, Che-Ani and Ismail, 2017; Mohamad, Ismail and Mohd Said, 2018).

In contrast, Iraq faces significant institutional voids, characterised by weak legal enforcement, fragmented authority, and limited stakeholder alignment (Alsamarraie and Ghazali, 2023c). According to Casady et al. (2020), such environments lack the “institutional capacity” necessary for effective PPP governance, leading to stalled or underperforming projects despite formal policy support. While institutional theory helps explain the broader structural and regulatory conditions that shape PPP outcomes, a closer examination of the specific barriers and risk factors at the project and policy levels is essential to understand the operational challenges that hinder successful PPP implementation—particularly in developing and transitional economies like Iraq.

Barriers and risk factors impacting PPP’s successful implementation

PPP frequently brings together institutions with radically distinct cultures, encompassing diverse priorities, beliefs, and perspectives, and this multi-dimensional cooperation between private and public sectors is complicated and time-consuming (Reich, 2018). PPP is noted as an uncommon environment where public and private objectives or moral and ethical standards merge (Paanakker and Reynaers, 2020). The private bodies have their own set of principles and beliefs that are distinct from those of the public bodies. As a result, there are often difficulties and inefficiencies in coordinating between the public and private bodies. The hierarchies of government organisations are often bureaucratic, while the formations of the private sector seem to be more flexible. Consequently, the contrasts in organisational characteristics make partnering extremely difficult (Alsamarraie and Ghazali, 2023a)

PPP has the most risk in the following categories: contracting (59%), funding (58%), divergent aims (45%), composition (40%), and commitment (39%) (Gobikas and Čingienė, 2021). Partners must have an upfront, honest conversation about their shared priorities and expectations. Next, the parties involved should keep talking about and re-evaluating their shared aims and objectives. In other words, better PPP collaboration will result from standardised methods of communication being put in place (Strasser et al., 2021). However, as every business has its purpose, vision, values, and culture, differences in these areas are unavoidable. As a result, PPP participants ought to establish mutually acceptable norms for cooperating productively toward shared objectives.

Recent studies have asserted that the PPP framework is significantly impacted by ineffective governance practices, such as ineffective procedural mechanisms, insufficient standards, an insufficient level of transparency, and discriminatory involvement in decision-making practices (Nuhu, Mpambije, and Ngussa, 2020). Many researchers concurred that a solid institutional context is essential for the effectiveness of PPP initiatives. In the absence of a robust organisational framework, PPP initiatives will fail. The organisational maturity of PPP is influenced by the maturity levels of legitimation, trustworthiness, and capability (Casady et al., 2020). Governments’ public bodies need to construct clear, predictable, and legal institutional arrangements by bolstering the PPP market and fostering legitimacy, confidence, and capability in the PPP framework. Political volatility hinders PPP’s planning and implementation. Organisations and authorities choose to delay and protect their rights because of uncertainty. The bureaucracy’s strong partisanship hinders PPP initiatives (Huque, 2021). Weak political and legislative frameworks represent one of the biggest obstacles to PPP adoption (Sadeghi, Bastani, and Barati, 2020). Countries like Bulgaria and Hungary did not even have PPP-specific regulations. Lack of administrative capacity and inadequate regulations restrict private sector activity in these nations (Delić, Šašić, and Tanović, 2021). Reforms to PPP should centre on the regulatory environment. It must provide extensive freedom in terms of the form and factual evidence of PPP. Table 2 shows some of the barriers and risk factors impacting PPP implementation.

| No. | Themes | Factors | Author |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Organisational | Absence of monitoring and performance auditing frameworks | (Delić, Šašić, and Tanović, 2021) |

| Tendering mechanism, accountability, and transparency issues | (Strasser et al., 2021) | ||

| Financing and implementation procedures | (Khaderi et al., 2019) | ||

| Lack of the recommended guidelines | (Hashim, Che-Ani, and Ismail, 2017) | ||

| Deficits in key performance indicators (KPIs) and insufficient instruction and training | (Alsamarraie and Ghazali, 2023a) | ||

| Life-cycle cost (LCC) calculation neglect | (Castelblanco et al., 2022) | ||

| Higher risk in the private sector | (Ismail and Azzahra Haris, 2014) | ||

| Uncertainty regarding government goals and assessment standards | (Ismail and Azzahra Haris, 2014) | ||

| The public sector’s centralisation | (Castelblanco et al., 2022) | ||

| Different cultures and goals | (Batjargal and Zhang, 2021) | ||

| Delays in project approvals | (Osei-Asibey et al., 2024) | ||

| High participation costs | (Hu et al., 2019) | ||

| 2 | Project | Reduce the project accountability | (Strasser et al., 2021) |

| Few plans have reached the contracting process (aborted before the contract) | (Ismail and Azzahra Haris, 2014) | ||

| High project costs | (Osei-Asibey et al., 2024) | ||

| Inadequate experience | (Osei-Asibey et al., 2024) | ||

| Lack of commitment | (Ismail and Azzahra Haris, 2014) | ||

| Level of demand | (Hu et al., 2019) | ||

| Competition risk | (Ahmadabadi and Heravi, 2019) | ||

| Uncompetitive tender | (Ahmadabadi and Heravi, 2019) | ||

| Similar project | (Ahmadabadi and Heravi, 2019) | ||

| Contractual risk | (Hu et al., 2019) | ||

| Land acquisition | (Hu et al., 2019) | ||

| Project delay | (Ismail and Azzahra Haris, 2014) | ||

| Contractor failure | (Dechev, 2015) | ||

| Design changes and deficiencies | (Dechev, 2015) | ||

| Poor quality of workmanship | (Dechev, 2015) | ||

| Fewer employment positions | (Ismail and Azzahra Haris, 2014) | ||

| 3 | Operational | Overly restrictive participation guidelines | (Osei-Asibey et al., 2024) |

| Long delays in agreements | (Osei-Asibey et al., 2024) | ||

| Risk of supporting facilities | (Huque, 2021) | ||

| Operation cost overruns | (Ismail and Azzahra Haris, 2014) | ||

| Residual value after the concession period | (Osei-Asibey et al., 2024) | ||

| Higher maintenance cost | (Ismail and Azzahra Haris, 2014) | ||

| Technology risk | (Parakhina et al., 2019) | ||

| Availability of labour | (Fabre and Straub, 2019) | ||

| 4 | External | Force majeure | (Casady et al., 2020) |

| Environment | |||

| Weather | (OECD, 2024) | ||

| 5 | Legal | Change in tax regulations | (Cepparulo, Eusepi, and Giuriato, 2019) |

| Corruption | (Schomaker, 2020) | ||

| Legislation changes | (Albalate, Bel, and Geddes, 2020) | ||

| 6 | Political | Inconsistencies in government policies | (Castelblanco et al., 2022) |

| Change in laws | (Albalate, Bel, and Geddes, 2020) | ||

| Poor public decisions | (Song, Hu, and Feng, 2018) | ||

| Strong political opposition | (Soomro, Li and Han, 2020) | ||

| Unstable government | (Sadeghi, Bastani, and Barati, 2020; Huque, 2021) |

Note: PPP, public–private partnership.

Operationalised analysis of barriers to PPP implementation

To enhance the systematic analysis of barriers to PPP implementation, this section operationalises barriers by defining their characteristics, categorising them thematically, and quantifying their prevalence. Operationalisation involves specifying barriers in terms of their nature (e.g., structural and procedural), impact (e.g., delays and cost overruns), and context (e.g., organisational and legal) to enable frequency and thematic categorisation (Strasser et al., 2021). Drawing on Table 2, which lists 36 barriers, this analysis categorises them into six thematic dimensions: organisational, project, operational, external, legal, and political. A frequency analysis quantifies the distribution of barriers across these categories, providing insights into their relative significance. The findings are summarised in Table 3 and elaborated in the following sections, enhancing the clarity and structure of the analysis.

Operationalisation of barriers

Barriers to PPP implementation are defined as obstacles that hinder the effective execution of PPP projects, impacting their efficiency, cost, or outcomes. Each barrier is operationalised by the following:

• Nature: The type of obstacle (e.g., lack of expertise and regulatory ambiguity).

• Impact: The consequence on PPP processes (e.g., delays and reduced investment).

• Context: The domain where the barrier occurs (e.g., public sector governance and project execution).

This framework allows for thematic categorisation and frequency analysis, addressing the need for systematic assessment.

Thematic categorisation

Based on Table 2, barriers were grouped into six thematic categories, adapted from the paper’s structure and aligned with prior research (Gobikas and Čingienė, 2021; Alsamarraie and Ghazali, 2023c):

• Organisational barriers: Issues within institutional structures, such as a lack of monitoring frameworks, transparency deficits, or cultural differences (Batjargal and Zhang, 2021; Delić, Šašić, and Tanović, 2021).

• Project barriers: Challenges specific to project planning and execution, including high costs, inadequate experience, or contractor failure (Dechev, 2015; Osei-Asibey et al., 2024).

• Operational barriers: Obstacles during project operation, such as cost overruns, technology risks, or labour shortages (Ismail and Azzahra Haris, 2014; Fabre and Straub, 2019).

• External barriers: Environmental or uncontrollable factors, such as force majeure or weather conditions (Casady et al., 2020).

• Legal barriers: Risks from regulatory frameworks, including tax changes or corruption (Cepparulo, Eusepi, and Giuriato, 2019; Schomaker, 2020).

• Political barriers: Challenges from governance instability, such as policy inconsistencies or unstable governments (Huque, 2021; Castelblanco et al., 2022).

Frequency analysis

To quantify the prevalence of barriers, the 36 barriers listed in Table 2 were assigned to one of the six thematic categories. The frequency count reflects the number of barriers in each category, providing insight into their relative significance. The results are as follows:

• Organisational barriers: 12 barriers (33.3%), e.g., absence of monitoring frameworks, transparency issues, and cultural differences.

• Project barriers: 14 barriers (38.9%), e.g., high project costs, contractor failure, and uncompetitive tenders.

• Operational barriers: eight barriers (22.2%), e.g., operation cost overruns and technology risks.

• External barriers: two barriers (5.6%), e.g., force majeure and weather.

• Legal barriers: three barriers (8.3%), e.g., corruption and tax regulation changes.

• Political barriers: five barriers (13.9%), e.g., inconsistent policies and unstable government.

The high frequency of project (38.9%) and organisational (33.3%) barriers suggests that PPP implementation is most hindered by planning, execution, and institutional challenges. Operational barriers (22.2%) are also significant, while external, legal, and political barriers are less frequent but critical due to their systemic impact.

Implications for PPP implementation

The thematic categorisation and frequency analysis reveal the following key insights:

• Project and organisational focus: The prevalence of project and organisational barriers indicates a need for improved planning, expertise development, and institutional coordination, particularly in Iraq, where capability deficits are noted (Alsamarraie and Ghazali, 2023c).

• Operational challenges: Operational barriers, such as cost overruns, highlight the importance of robust risk-sharing agreements, as seen in Malaysia’s performance-based contracts (Hashim, Che-Ani, and Ismail, 2017).

• Systemic risks: Legal and political barriers, although less frequent, pose significant risks due to their potential to disrupt entire projects, as evidenced in Iraq’s regulatory instability (Huque, 2021).

• External factors: The low frequency of external barriers suggests that they are less common but require contingency planning, as seen in global PPP practices (Casady et al., 2020).

This operationalised analysis enables targeted strategies to address barriers, such as capacity building for organisational issues, standardised contracts for project risks, and regulatory reforms for legal and political challenges.

Summary of barrier analysis

Table 3 summarises the thematic categorisation and frequency of barriers, providing a structured overview of their distribution and significance.

This operationalised analysis enhances the understanding of PPP barriers by providing a systematic framework for their categorisation and prioritisation. By addressing the most frequent barriers (project and organisational) and mitigating systemic risks (legal and political), countries like Iraq and Malaysia can improve PPP implementation outcomes.

Comprehensive comparative analysis of PPP procurement in Iraq and Malaysia

This section provides an in-depth comparison of PPP procurement in Iraq and Malaysia, analysing institutional maturity, procurement governance, regulatory risk mitigation, and financing approaches. Institutional maturity, as defined by Casady et al. (2020), encompasses legitimation (stakeholder acceptance), trustworthiness (reliability of arrangements), and capability (management effectiveness). Procurement governance, regulatory risk mitigation, and financing approaches further elucidate structural and contextual differences, as indicated by Reich (2018), Strasser et al. (2021), and Owolabi et al. (2019). Lines of evidence from Table 2 and Figure 4 clarify the analysis, highlighting implications for PPP outcomes.

Institutional maturity

1. Legitimation

• Iraq: PPP legitimation in Iraq is weak due to a history of economic nationalisation (1963–2003) and centralised public sector control (Alsamarraie and Ghazali, 2023b). Post-2003 regulatory reforms to attract private investment face stakeholder scepticism, as public and private sectors lack a shared understanding of PPP benefits (Khudhaire and Naji, 2021). This contributes to delays in project approvals (Osei-Asibey et al., 2024).

• Malaysia: Malaysia exhibits strong legitimation, formalised through the 9th Malaysia Plan (2006–2010) and reinforced by successful projects in transportation and healthcare (Hashim, Che-Ani, and Ismail, 2017). The PPP Unit (UKAS) fosters stakeholder acceptance, enabling faster contract negotiations.

• Distinction: Malaysia’s policy stability and PPP track record drive mature legitimation, while Iraq’s historical mistrust and political volatility hinder stakeholder buy-in.

2. Trustworthiness

• Iraq: Iraq’s PPP framework lacks trustworthiness due to inconsistent regulations and political instability (Huque, 2021). The absence of a PPP-specific law and reliance on international support (World Bank, UNIDO) for a PPP Unit signal unreliable arrangements (Motlag and Ghasemlounia, 2021). High risks like corruption deter investors (Schomaker, 2020).

• Malaysia: Malaysia’s framework is trustworthy, with clear regulations and standardised processes via the PPP Unit (Mohamad, Ismail, and Mohd Said, 2018). Performance-based contracts enhance reliability, although transparency gaps occasionally challenge trust (Ismail and Azzahra Haris, 2014).

• Distinction: Malaysia’s consistent regulatory environment fosters investor confidence, unlike Iraq’s fragmented framework, which increases uncertainty.

3. Capability

• Iraq: Iraq’s public sector lacks technical and managerial capability, as seen in poor electricity project performance since 2006 (Alsaffar and Altaay, 2014). Inadequate training and professional shortages cause tendering inefficiencies (Alsamarraie and Ghazali, 2023c).

• Malaysia: Malaysia demonstrates high capability, with skilled administration managing diverse projects (Mohamad, Ismail, and Mohd Said, 2018). Performance indicators reflect advanced practices (Idris, 2010), although political delays occur (Ismail and Azzahra Haris, 2014).

• Distinction: Malaysia’s robust capacity ensures efficient execution, while Iraq’s limited expertise impedes progress.

Procurement governance

Procurement governance involves institutional structures, decision-making, and accountability mechanisms (Reich, 2018; Strasser et al., 2021).

• Iraq: Iraq’s governance is fragmented, with decisions dispersed across various ministries, resulting in bureaucratic delays and political interference (Huque, 2021). The lack of a centralised PPP unit, as shown in Figure 4, hinders coordination. Weak accountability, with corruption and poor monitoring, undermines delivery (Schomaker, 2020).

• Malaysia: Malaysia’s governance is centralised through the PPP Unit, ensuring standardised processes and key performance indicators (KPIs) (Hashim, Che-Ani and Ismail, 2017). Political delays can occur (Ismail and Azzahra Haris, 2014), but structured oversight supports efficiency.

• Distinction: Malaysia’s centralised governance enhances coordination and accountability, while Iraq’s fragmented structure exacerbates inefficiencies.

Regulatory risk mitigation

Regulatory risk mitigation addresses risks from legal and policy frameworks (Owolabi et al., 2019).

• Iraq: Iraq’s underdeveloped regulatory environment, lacking a PPP law, increases risks like legislative changes and corruption, as shown in Table 2 (Albalate, Bel, and Geddes, 2020; Alsamarraie and Ghazali, 2023a). International support for legislation (Motlag and Ghasemlounia, 2021) highlights limited capacity, impacting projects like electricity PPPs (Alsaffar and Altaay, 2014).

• Malaysia: Malaysia’s mature framework, with clear guidelines and PPP Unit oversight, mitigates risks through standardised contracts (Štěrbová, Halík, and Neumannová, 2020). Transparency gaps exist (Ismail and Azzahra Haris, 2014), but regulatory stability has supported 28 projects since 2016 (Hashim, Che-Ani, and Ismail, 2017).

• Distinction: Malaysia’s structured regulations reduce risks, while Iraq’s regulatory gaps heighten uncertainties.

Financing approaches

Financing approaches involve funding models and risk-sharing mechanisms (Casady et al., 2020).

• Iraq: Iraq relies on government funds and international support, with $150 billion allocated by 2025 (Alsaffar and Altaay, 2014). Ad hoc financing models and unclear risk sharing limit private investment (Khudhaire and Naji, 2021), with high funding risks (58%) (Gobikas and Čingienė, 2021).

• Malaysia: Malaysia uses diversified models (e.g., BOT and DBFO), with clear risk-sharing via performance-based contracts (Hashim, Che-Ani, and Ismail, 2017). High participation costs can exclude smaller investors, as shown in Table 2 (Hu et al., 2019), but flexible financing attracts capital.

• Distinction: Malaysia’s structured financing attracts private investment, while Iraq’s reliance on public funds restricts scalability.

Implications for PPP outcomes

• Iraq: Weak institutional maturity, fragmented governance, high regulatory risks, and ad hoc financing lead to delays, high risks (59% contracting risk; Gobikas and Čingienė, 2021), and poor performance, notably in electricity projects.

• Malaysia: Strong institutional maturity, robust governance, effective risk mitigation, and diversified financing enable efficient execution (Hashim, Che-Ani, and Ismail, 2017). Political delays and costs suggest refinement areas.

• Comparative insight: Malaysia’s systems offer a model for Iraq, which could benefit from a centralised PPP unit, standardised regulations, and clear financing models.

Summary of comparative insights

Table 4 summarises distinctions in institutional maturity, procurement governance, regulatory risk mitigation, and financing approaches.

Notes: KPIs, key performance indicators; BTO, build-transfer-operate; DBFO, design-build-finance-operate.

This analysis highlights the critical role of institutional and structural factors in PPP procurement. Iraq can enhance outcomes by adopting Malaysia’s centralised governance, regulatory clarity, and financing strategies.

Discussion

The comparative findings between Iraq and Malaysia highlight not only differences in policy and regulatory implementation but also deeper structural and institutional contrasts that influence PPP success. While the results show Malaysia’s well-established PPP framework, this section goes further to analyse what these differences reveal about broader patterns in PPP adoption and performance, particularly in emerging and post-conflict economies.

Malaysia’s structured PPP procurement model, centralised oversight, and use of performance-based contracts reflect international trends seen in other upper-middle-income countries with similar governance capacities, such as Chile and South Africa (Bayliss and Van Waeyenberge, 2018). These countries typically demonstrate institutional readiness, legal clarity, and predictable enforcement mechanisms—factors closely associated with higher project completion rates and sustained private sector engagement. Malaysia’s implementation of KPIs, risk-sharing mechanisms, and private sector incentives confirms the effectiveness of these strategies in building long-term public–private trust and delivering infrastructure efficiently.

In contrast, Iraq’s fragmented regulatory environment, limited administrative capacity, and political instability mirror challenges faced by other post-conflict or fragile states. The findings indicate that while Iraq has formally adopted PPP legislation and policy frameworks, the lack of operational capacity, legal enforcement, and investor protections limits actual implementation. This gap between formal adoption and practical functionality is a common pattern in fragile states where institutions are weak or politically contested (Casady et al., 2020). As such, Iraq’s experience underlines the importance of sequencing PPP reforms in tandem with broader governance and capacity-building efforts.

Moreover, the comparative findings suggest that PPP performance is not only about adopting best practices but also about adapting them to context. Countries cannot simply replicate models from high-performing states without aligning them with local institutional realities. The presence of risk matrices and performance-based contracts, for instance, is effective only when accompanied by reliable enforcement mechanisms and competent oversight bodies. This insight aligns with institutional theory, which emphasises that successful policy implementation depends on the strength and compatibility of underlying institutions (Ensslin, Welter, and Pedersini, 2022).

Ultimately, the analysis reveals that institutional readiness, more than technical design, is the key differentiator between functional and non-functional PPP systems. Malaysia’s ability to align procurement policies with its legal and financial institutions contributes significantly to its PPP success. Iraq, however, must focus on reducing fragmentation, increasing stakeholder coordination, and enhancing administrative transparency to realise the full potential of PPP frameworks. These findings carry important implications for other emerging or post-conflict economies seeking to implement PPPs under constrained institutional settings.

These findings align with broader international patterns in PPP performance across emerging economies. Countries like Chile, Colombia, and South Africa demonstrate how sustained political support, institutional maturity, and transparent procurement systems contribute to stable PPP ecosystems (Bayliss and Van Waeyenberge, 2018; Fabre and Straub, 2019). Conversely, Iraq’s experience mirrors that of fragile or post-conflict nations such as Sudan, Afghanistan, or Egypt, where legal uncertainty, low institutional capacity, and political risk hinder PPP adoption despite donor interest and formal reforms. Malaysia’s trajectory also reflects the Southeast Asian regional trend, where structured regulatory environments and early public sector reforms have enabled better private engagement, similar to Indonesia and the Philippines. Thus, benchmarking Iraq and Malaysia within this wider landscape allows policymakers to better understand where reform priorities should lie and how peer learning can support more resilient PPP implementation.

Conclusion

This study examined the implementation of PPPs in both developed and developing contexts, with a particular focus on Malaysia and Iraq. It aimed to identify strategic approaches for strengthening public–private engagement, especially in developing economies where infrastructure investment gaps remain critical. PPPs offer viable solutions by leveraging private capital and expertise, but their effectiveness depends heavily on context-specific conditions. In many developing countries, private entities hesitate to engage in PPPs due to the burden of critical risks, such as demand uncertainty and political instability. To address this, development institutions must proactively use concessional finance and risk-sharing tools to attract investment. They should also broaden awareness campaigns that highlight PPPs not just as cost-saving mechanisms but also as tools for innovation, service improvement, and institutional capacity building.

Through comparative analysis, the study showed that procurement practices differ widely based on national priorities and institutional maturity. Developed countries often target social sectors, while transitioning economies emphasise transport and infrastructure. Malaysia has established centralised PPP units and performance-linked procurement mechanisms, contributing to greater private sector participation. Iraq, by contrast, struggles with regulatory fragmentation and governance limitations. This comparative lens uncovered several best practices, including the use of solicited proposals, third-party technical advisors, risk matrix frameworks, and continuous performance evaluation. Such practices form the basis for practical recommendations on how to enhance procurement integrity and public service delivery.

Theoretically, this study contributes a context-sensitive comparative framework rooted in institutional theory. It highlights three interdependent pillars—institutional readiness, risk allocation, and procedural transparency—as essential to understanding PPP outcomes. By integrating these dimensions, the study offers a clearer explanation for the divergent performance of similar PPP models across different governance settings, especially in emerging and post-conflict economies.

Future research should delve deeper into Iraq’s implementation challenges, particularly around stakeholder coordination and trust. Delphi-based expert panels can be used to identify critical policy reforms, while grounded theory can explore perceptions of institutional legitimacy and risk tolerance among PPP actors. Further inquiries may examine the alignment of control mechanisms between partners and investigate alternative funding strategies beyond traditional PPP structures. Comparative quantitative studies could also evaluate how different governance models impact PPP performance across sectors. These directions will add depth to the discourse and support the design of adaptive, resilient PPP frameworks in complex environments.

References

ABUZAINEH, N., BRASHERS, E., FOONG, S., FEACHEM, R., DA RITA, P. 2018. PPPs in healthcare: Models, lessons and trends for the future. Healthcare public-private partnerships, 4. https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/industries/healthcare/publications/trends-for-the-future.html

AHMADABADI, A. A. & HERAVI, G. 2019. The effect of critical success factors on project success in Public-Private Partnership projects: A case study of highway projects in Iran. Transport policy, 73, pp.152-161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2018.07.004

ALBALATE, D., BEL, G. & GEDDES, R. R. 2020. Do public-private-partnership-enabling laws increase private investment in transportation infrastructure? The journal of law and Economics, 63 (1), pp.43-70. https://doi.org/10.1086/706247

ALSAFFAR, A. & ALTAAY, M. R. 2014. Paving the Way for PPP’s to Infrastructure Projects in Iraq. Journal of Engineering, 20 (12), pp.32-60. https://doi.org/10.31026/j.eng.2014.12.03

ALSAMARRAIE, M. M. & GHAZALI, F. 2023a. Evaluation of organizational procurement performance for public construction projects: systematic review. International Journal of Construction Management, 23 (14), pp.2499-2508. https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2022.2070447

ALSAMARRAIE, M. M. & GHAZALI, F. 2023b. Cost-Benefit Analysis Of Using Bim Compared To Traditional Methods In Iraq’s Public Construction Projects. ASEAN Engineering Journal, 13 (2), pp.107-114. https://doi.org/10.11113/aej.v13.18982

ALSAMARRAIE, M. M. & GHAZALI, F. E. M. 2023c. Barriers and Challenges for Public Procurement Integrity in Iraq: Systematic Review Study. KSCE Journal of Civil Engineering, 27 (9), pp.3633-3645. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12205-023-1196-4

ATMO, G. & DUFFIELD, C. 2014. Improving investment sustainability for PPP power projects in emerging economies: Value for money framework. Built Environment Project and Asset Management, 4 (4), pp.335-351. https://doi.org/10.1108/BEPAM-10-2013-0051

BATJARGAL, T. & ZHANG, M. 2021. Review of key challenges in public-private partnership implementation. Journal of Infrastructure, Policy and Development, 5 (2), pp.1378. https://doi.org/10.24294/jipd.v5i2.1378

BAYLISS, K. & VAN WAEYENBERGE, E. 2018. Unpacking the Public Private Partnership Revival. The Journal of Development Studies, 54 (4), pp.577-593. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2017.1303671

CASADY, C. B., ERIKSSON, K., LEVITT, R. E. & SCOTT, W. R. 2020. (Re)defining public-private partnerships (PPPs) in the new public governance (NPG) paradigm: an institutional maturity perspective. Public Management Review, 22 (2), pp.161-183. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2019.1577909

CASTELBLANCO, G., GUEVARA, J., MESA, H. & HARTMANN, A. 2022. Social legitimacy challenges in toll road PPP programs: Analysis of the Colombian and Chilean cases. Journal of management in engineering, 38 (3), pp.05022002. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0001013

CEPPARULO, A., EUSEPI, G. & GIURIATO, L. 2019. Public Private Partnership and fiscal illusion: A systematic review. Journal of Infrastructure, Policy and Development, 3 (2), pp.288-309. https://doi.org/10.24294/jipd.v3i2.1157

CHAN, A. P. C. & OWUSU, E. K. 2022. Evolution of Electronic Procurement: Contemporary Review of Adoption and Implementation Strategies. Buildings [Online], 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings12020198

DECHEV, D. 2015. Public-private partnership-a new perspective for the transition countries. Trakia Journal of Sciences, 13 (3). https://doi.org/10.15547/tjs.2015.03.008

DELIĆ, A., ŠAŠIĆ, Đ. & TANOVIĆ, M. 2021. Preconditions for Establishing Public Private Partnership as a Model of Effective Management of Public Affairs. Uprava, 12 (1), pp.55-69. https://doi.org/10.53028/1986-6127.2021.12.1.55

DORDEVIC, A. & RAKIC, B. 2020. Comparative analysis of PPP projects sectoral structure in developed and developing countries. Facta Universitatis. Series: Economics and Organization, pp.187-202. https://doi.org/10.22190/FUEO200304014D

ENDO, K. & SEETHARAM, K. 2021. Public–Private Partnerships in Developing Asian Countries: Practical Suggestions for Future Development Assistance. ADBI Policy Brief, (No. 2021-5), pp.1 - 10. https://www.adb.org/publications/public-private-partnerships-developing-asian-countries-practical-suggestions-future

ENGEL, E., FISCHER, R. & GALETOVIC, A. 2013. The basic public finance of public–private partnerships. Journal of the European economic association, 11 (1), pp.83-111. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1542-4774.2012.01105.x

ENSSLIN, S. R., WELTER, L. M. & PEDERSINI, D. R. 2022. Performance evaluation: a comparative study between public and private sectors. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 71 (5), pp.1761-1785. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPPM-04-2020-0146

EPEC, E. P. P.-P. P. E. C. 2022. Review of the European PPP Market for 2010 to 2021. https://data.eib.org/epec

FABRE, A. & STRAUB, S. 2019. The economic impact of public private partnerships (PPPs) in infrastructure, health and education: A review. Toulouse School of Economics. https://www.tse-fr.eu/sites/default/files/TSE/documents/doc/wp/2019/wp_tse_986.pdf

GOBIKAS, M. & ČINGIENĖ, V. 2021. Public-private partnership in youth sport delivery: local government perspective. Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 21, pp.1185-1190. https://doi.org/10.7752/jpes.2021.s2149

HASHIM, H., CHE-ANI, A. I. & ISMAIL, K. 2017. Review of issues and challenges for public private partnership (PPP) project performance in Malaysia. AIP Conference Proceedings, 1891 (1), pp.020051. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5005384

HELBY PETERSEN, O. 2019. EVALUATING THE COSTS, QUALITY, AND VALUE FOR MONEY OF INFRASTRUCTURE PUBLIC-PRIVATE PARTNERSHIPS: A SYSTEMATIC LITERATURE REVIEW. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 90 (2), pp.227-244. https://doi.org/10.1111/apce.12243

HU, X., XIA, B., HU, Y., SKITMORE, M. & BUYS, L. 2019. What hinders the development of Chinese continuing care retirement community sector? A news coverage analysis. International Journal of Strategic Property Management, 23 (2), pp.108-116. https://doi.org/10.3846/ijspm.2019.7436

HUQUE, A. S. 2021. Infrastructure, Political Conflict, and Stakeholder Interests: The Case of a Public–Private Partnership in Bangladesh. Public Works Management & Policy, 26 (2), pp.75-94. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087724X19895281

HWANG, B.-G., ZHAO, X. & GAY, M. J. S. 2013. Public private partnership projects in Singapore: Factors, critical risks and preferred risk allocation from the perspective of contractors. International journal of project management, 31 (3), pp.424-433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2012.07.003

IDRIS, M. S. M. 2010. National asset planning in Malaysia. Journal of Retail & Leisure Property, 9 (1), pp.1-3. https://doi.org/10.1057/rlp.2009.24

ISMAIL, S. & AZZAHRA HARIS, F. 2014. Constraints in implementing Public Private Partnership (PPP) in Malaysia. Built Environment Project and Asset Management, 4 (3), pp.238-250. https://doi.org/10.1108/BEPAM-10-2013-0049

JAYASURIYA, S., ZHANG, G. & JING YANG, R. 2019. Challenges in public private partnerships in construction industry: A review and further research directions. Built Environment Project and Asset Management, 9 (2), pp.172-185. https://doi.org/10.1108/BEPAM-02-2018-0042

KHADERI, S. S., BAKRI, A. S., ABD SHUKOR, A. S., KAMIL, A. I. M. & MAHBUB, R. Tendering Issues and Improvement in Public Infrastructure Project Through Public-Private Partnerships (PPP)/Private Finance Initiative (PFI). IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 2019. IOP Publishing, pp.012048. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/267/1/012048

KHUDHAIRE, H. Y. & NAJI, H. I. 2021. Adoption PPP model as an alternative method of government for funding abandoned construction projects in Iraq. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 1076 (1), pp.012115. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/1076/1/012115

KIM, S. & KWA, K. X. 2019. Exploring public-private partnerships in Singapore: The success-failure continuum, Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429290701

LI, J., GREENWOOD, D. & KASSEM, M. 2019. Blockchain in the built environment and construction industry: A systematic review, conceptual models and practical use cases. Automation in Construction, 102, pp.288-307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2019.02.005

LOOSEMORE, M. & MALOUF, N. 2019. Safety training and positive safety attitude formation in the Australian construction industry. Safety Science, 113, pp.233-243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2018.11.029

MOHAMAD, R., ISMAIL, S. & MOHD SAID, J. 2018. Performance indicators for public private partnership (PPP) projects in Malaysia. Journal of Economic and Administrative Sciences, 34 (2), pp.137-152. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEAS-04-2017-0018

MOTLAG, M. H. & GHASEMLOUNIA, R. 2021. Method of Partnership with the Private Sector in Iraq. Available at SSRN 3822123. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3822123

NATIONAL CENTER FOR PUBLIC PRIVATE PARTNERSHIP, M. O. F. O. T. R. F., STATE DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION 2019. G20 IWG Report on the Results of the Survey on Public-Private Partnership Developments in the G20 Economies. pp.1 - 46. https://www.gihub.org/resources/publications/g20-iwg-report-on-the-results-of-the-survey-on-public-private-partnership-developments-in-the-g20-economies/

NUHU, S., MPAMBIJE, C. J. & NGUSSA, K. 2020. Challenges in health service delivery under public-private partnership in Tanzania: stakeholders’ views from Dar es Salaam region. BMC health services research, 20, pp.1-12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05638-z

OECD, W. B., & UN ENVIRONMENT 2024. Infrastructure for a Climate-Resilient Future. OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/infrastructure-for-a-climate-resilient-future_537a2c80-en.html

OSEI-ASIBEY, D., AYARKWA, J., BAAH, B., AFFUL, A. E., ANOKYE, G. & NKRUMAH, P. A. 2024. Impact of time-based delay on public-private partnership (PPP) construction project delivery: construction stakeholders’ perspective. Journal of Financial Management of Property and Construction. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMPC-07-2023-0044

OWOLABI, H. A., OYEDELE, L., ALAKA, H., EBOHON, O. J., AJAYI, S., AKINADE, O., BILAL, M. & OLAWALE, O. 2019. Public private partnerships (PPP) in the developing world: Mitigating financiers’ risks. World Journal of Science, Technology and Sustainable Development, 16 (3), pp.121-141. https://doi.org/10.1108/WJSTSD-05-2018-0043

OZORHON, B., OZCAN-DENIZ, G. & KIR, O. D. 2021. Challenges of Public Private Partnership (PPP) Healthcare Projects: Case Study in Developing Countries. In: LEATHEM, T., PERRENOUD, A. & COLLINS, W., eds. ASC 2021. 57th Annual Associated Schools of Construction International Conference, 2021. EasyChair, pp.136-145. https://doi.org/10.29007/nz4z

PAANAKKER, H. & REYNAERS, A.-M. 2020. Value Contextuality in Public Service Delivery. An Analysis of Street-Level Craftsmanship and Public–Private Partnerships. Public Integrity, 22 (3), pp.245-255. https://doi.org/10.1080/10999922.2020.1715128

PARAKHINA, V. N., VORONTSOVA, G. V., MOMOTOVA, O. N., BORIS, O. A. & USTAEV, R. M. 2019. Innovational Projects of Technological Growth on the Platform of Public–Private Partnership: Risks and Methods of Their Minimization. ed. Tech, Smart Cities, and Regional Development in Contemporary Russia. Emerald Publishing Limited. pp.15-27. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-78973-881-020191003

QUELIN, B. V., CABRAL, S., LAZZARINI, S. & KIVLENIECE, I. 2019. The Private Scope in Public–Private Collaborations: An Institutional and Capability-Based Perspective. Organization Science, 30 (4), pp.831-846. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2018.1251

REICH, M. R. 2018. The Core Roles of Transparency and Accountability in the Governance of Global Health Public–Private Partnerships. Health Systems & Reform, 4 (3), pp.239-248. https://doi.org/10.1080/23288604.2018.1465880

ROSELL, J. & SAZ-CARRANZA, A. 2020. Determinants of public–private partnership policies. Public Management Review, 22 (8), pp.1171-1190. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2019.1619816

SADEGHI, A., BASTANI, P. & BARATI, O. 2020. Identifying barriers to development of the public-private partnership in providing of hospital services in Iran: A qualitative study. Evidence Based Health Policy, Management and Economics. https://doi.org/10.18502/jebhpme.v4i3.4162

SCHOMAKER, R. M. 2020. Conceptualizing corruption in public private partnerships. Public Organization Review, 20 (4), pp.807-820. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-020-00473-6

SONG, J., HU, Y. & FENG, Z. 2018. Factors influencing early termination of PPP projects in China. Journal of management in engineering, 34 (1), pp.05017008. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0000572

SOOMRO, M. A., LI, Y. & HAN, Y. 2020. Socioeconomic and political issues in transportation public–private partnership failures. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 69 (5), pp.2073-2087. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEM.2020.2997361

ŠTĚRBOVÁ, L., HALÍK, J. & NEUMANNOVÁ, P. 2020. Traditional Procurement versus Public-Pivate Partnership: A Comparison and Synergies with Focus on Cross-border Contracts. Naše gospodarstvo/Our economy, 66 (1), pp.52-64. https://doi.org/10.2478/ngoe-2020-0005

STRASSER, S., STAUBER, C., SHRIVASTAVA, R., RILEY, P. & O’QUIN, K. 2021. Collective insights of public-private partnership impacts and sustainability: A qualitative analysis. Plos one, 16 (7), pp.e0254495. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0254495

TREBILCOCK, M. & ROSENSTOCK, M. 2015. Infrastructure public–private partnerships in the developing world: Lessons from recent experience. The Journal of Development Studies, 51 (4), pp.335-354. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2014.959935

WARSEN, R., KLIJN, E. H. & KOPPENJAN, J. 2019. Mix and match: How contractual and relational conditions are combined in successful public–private partnerships. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 29 (3), pp.375-393. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muy082

WBG, W. B. G. 2022. PPP projects in the countries of the world. https://ppp.worldbank.org/public-private-partnership/

YOUSIF, O. S., ZAKARIA, R., MOHSIN, I. N., AMINUDIN, E., SINGARAM, L., GARA, J. A. & KHALID, R. 2024. Iraqi construction industry digitalization: Trends, opportunities and challenges. AIP Conference Proceedings, 2944 (1), pp.020010. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0204869