Construction Economics and Building

Vol. 25, No. 3/4

December 2025

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Project High-Performance Work System for Enabling High-Performing Teams in Construction

Sarath Gunathilaka*, Dulanga Wijesekara, Shing Fung Kwok

Department of Construction Management, School of Architecture, Design and the Built Environment, Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, United Kingdom

Corresponding author: Sarath Gunathilaka, sarath_gunathilaka@yahoo.com

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v25i3/4.9322

Article History: Received 01/09/2024; Revised 19/01/2025; Accepted 20/04/2025; Published 05/12/2025

Citation: Gunathilaka, S., Wijesekara, D., Kwok, S. F. 2025. Project High-Performance Work System for Enabling High-Performing Teams in Construction. Construction Economics and Building, 25:3/4, 43–64. https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v25i3/4.9322

Abstract

Modern construction organizations demand high-performing teams (HPTs) in their projects in order to face increasing performance challenges. On the one hand, they face significant performance challenges due to the competition in the industry in many forms, such as competitive bidding to receive projects. On the other hand, they need to manage the performance challenges posed by the complexities of the uncertain and volatile construction project environment to deliver projects successfully and build up strong organizational profiles to face such issues. At the same time, they must also follow the legislative requirements of their countries, which are focused on the big issues and challenges that exist in the contemporary construction industry. In order to enable HPTs, they need a high-performance work system (HPWS) that can facilitate their projects. However, although literature shows numerous studies on organizational HPWSs that consist of human resource management practices, only limited attention has been given to identifying such a system for the project context. This study aimed to fill this knowledge gap through a quantitative research study. The project high-performance work system (PHPWS) was conceptualized using literature and tested using 221 responses to a questionnaire survey among team members in construction projects. The exploratory factor and confirmatory factor analyses were performed to analyze data to conclude this PHPWS. The findings facilitate the construction organizations to create the PHPWS for enabling HPTs in their projects and constitute a significant original contribution to the theory and practice in the construction management research domain.

Keywords

Construction Projects; High-Performing Teams; Human Resource Management; Project High-Performance Work System; Project Team Performance

Introduction

The construction industry has been rapidly moving forward with collaboration among project stakeholders (Daniel, et al., 2017), and collaboration among project delivery parties, such as teamwork, has become vital compared to other forms. Teamwork is still an evolving research theme, although its original contributions go back to the 20th century. Accordingly, research on high-performing teams (HPTs) has become prominent among academics and industry practitioners nowadays because construction organizations have been continuously demanding HPTs in their projects. In general, HPTs are the teams that have the capacity to generate superior performance beyond the average level. On the one hand, today’s construction organizations demand HPTs to help them face their performance challenges due to increasing competition in the industry. For example, they face competition in many ways, such as bidding for receiving projects (Ahmed, El-Adaway, and Caldwell, 2024), branding products and services (Anjomshoa, 2024), and improving performance with corporate social responsibility and innovation (Zheng, et al., 2024). The challenges also emerged in achieving sustainability requirements in the society (Blay Jnr, et al., 2023), receiving productive labor that leads to technological progress (Bellocchi and Travaglini, 2023), and maintaining green innovation as demanded by modern construction clients (López-Malest, et al., 2024). On the other hand, today’s construction organizations face significant complexity challenges from the uncertain and volatile project environment or the construction industry overall. For example, they face complexity in moving with the modern globalization and liberalization trends (Rani, et al., 2023), conflicts due to unsustainable construction practices (Omopariola, et al., 2024), digital transformation barriers (Chen, et al., 2024), and adverse carbon emissions in projects (Liu, et al., 2024). The complexity challenges also emerged due to project size and scope (de Valence, 2011), strict legal requirements on the drivers of construction productivity such as safety regulations (Chancellor, 2015), and the application of modern technology and methodology such as building information modeling and digital twin (Olatunji and Sher, 2014; Bolton, et al., 2018).

In addition to the competition and complexity challenges, today’s construction organizations also have to work in accordance with the legislative frameworks in their countries that are focused on addressing big issues and challenges in the contemporary construction industry. For example, cost minimization in construction projects becomes crucial for the project teams today. The construction industry’s worldwide spending was approximately USD12 trillion with an increasing rate of 3% per annum in 2019 and is anticipated to reach USD19.2 trillion in 2035 (Statista, 2019). Therefore, the construction industry is experiencing a revolution aimed at reducing cost (Deep, et al. 2021). Research evidence has shown that the industry needs to pay significant attention to improving the construction practices in terms of investment, project sizes, procurement, construction process, and technology (Deep, et al. 2021). Furthermore, literature evidence shows that both public and private sector organizations in the industry still have severe shortfalls in their initiatives to achieve the United Nations’ 17 sustainable development goals by 2030 (Sankaran, Müller, and Drouin, 2020). Therefore, most governments implement legislative requirements in their procurement practices with strict rules and regulations to be followed by the project teams. Moreover, if the construction project teams do not perform well, the risk of insolvency of their organizations will be higher because insolvency is a significant issue in the construction sector (Coggins, Teng, and Rameezdeen, 2016). This means that the construction organizations need HPTs in their projects in order to face these issues and challenges.

In order to enable HPTs in their projects, the construction organizations should create high-performance work systems (HPWSs) that consist of systems and practices to facilitate this process. Literature shows evidence of such an HPWS that consists of human resource management (HRM) practices in the organizational context (e.g., Huselid, 1995; Bowen and Ostroff, 2004; Boxall and Macky, 2009; Takeuchi, et al., 2009; Chiang and Hsu, 2012; Guest and Bos-Nehles, 2013; Kehoe and Wright, 2013; Pak and Kim, 2016; Shin and Konrad, 2017; Siddique, Procter and Gittell, 2019; Teo, Bentley and Nguyen, 2020; Estiri, et al., 2021; Farrukh, et al., 2021; Nassani, et al., 2023). However, among the plethora of such studies on the need to continuously develop HPWSs in the organizational context, only marginal attention has been given to exploring such a system in the project context. There are some noteworthy contributions to developing the project HRM system (e.g., Bellini and Canonico, 2008; Bondarouk and Ruel, 2008; Abuazoom, et al., 2017), but a clear HPWS in the project context is inadequately revealed. As the demand for HPTs grows in the modern construction industry, unveiling such an HPWS to facilitate the enabling process of HPTs in the project context is a significant knowledge gap that adversely affects the contemporary construction industry’s performance.

As such, this study aimed to fill this knowledge gap by conducting a quantitative research study with the objective of developing the project high-performance work system (PHPWS) that can enable HPTs. Accordingly, the paper is structured with the following sections: literature review, research methodology, results, discussion of the findings, and conclusions. The PHPWS has been developed as a contribution to the study in order to make a difference in the construction industry by indicating the importance of developing such a system in construction projects to enable HPTs.

Literature review

Organizational high-performance work system

As discussed in the introduction, HPWSs are needed to facilitate the enabling process of HPTs. Literature shows that the theory and practice in this research theme have been developing for several years. The high-performance paradigm was the theoretical juncture for starting a high-performance culture in the business industry (Danford, et al., 2005; Hughes, 2008). This was a managerial approach for driving high-performance outcomes, focusing on utilizing mutually reinforced production and labor management practices (Hughes, 2008). Such a high-performance work culture originated several decades ago with the Japanese influence in production and work organizations after World War II, although it has since been integrated into other sectors (Ashton and Sung, 2002; Danford, et al., 2005; Hughes, 2008). The literature shows evidence of research on high-performance work organization as the starting point for developing such a high-performance culture in the industry (Huselid, 1995; Hughes, 2008; Gong, et al., 2010; Pak and Kim, 2016). Thereafter, the idea has moved toward exploring high-performance work practices (HPWPs) that consist of HRM practices in terms of developing more effective organizations to achieve high performance (Huselid, 1995; Hughes, 2008; Ogbonnaya, et al., 2017; Shin and Konrad, 2017). Such HPWPs promote positive employee outcomes such as trust, commitment, psychological health, and job satisfaction to achieve high performance in organizational work settings (Van De Voorde, et al., 2012; Ogbonnaya, et al., 2017). Thereafter, research attention has moved toward HPWS in the organizational context.

Many authors defined the HPWS as a set of coherent HRM practices that organizations could implement to facilitate employee skills and motivation for achieving high performance and productivity (e.g., Huselid, 1995; Bowen and Ostroff, 2004; Boxall and Macky, 2009; Takeuchi, et al., 2009; Chiang and Hsu, 2012; Pak and Kim, 2016; Shin and Konrad, 2017; Siddique, Procter and Gittell, 2019). Generally, enhancing employee skills makes them comfortable to work with motivation, and, thus, better HRM practices facilitate high performance. Some researchers view that the HPWS in organizations is associated with employee behavior (Miao, et al., 2020), while others believe that it facilitates employees’ commitment and empowerment to perform (Para-González, Jiménez-Jiménez, and Martínez-Lorente, 2019). It is actually not only these aspects, but it is also linked with employee relations as HRM practices. However, although the HPWS facilitates the high performance of teams, research evidence shows that this can also exert negative effects (Han, Sun, and Wang, 2020). This may be due to negative HRM practices or the negative influence of HRM practices, but reviewing such practices was outside the scope of this paper.

Table 1 shows the HRM practices of the HPWS in the organizational context. According to this review, there are two categories of the characteristics of the organizational HPWS. The first category consists of the characteristics that are related to the general HRM system of the organizations such as job security (Teo, Bentley and Nguyen, 2020), better human resource outcomes (Estiri, et al., 2021), employees’ job satisfaction and work engagement (Ogbonnaya and Valizade, 2018), and employee resilience (Cooke, et al., 2019). The second category consists of specific HRM functions. The first HRM function is recruitment and selection, which includes practices such as job role design in terms of employee skills and capabilities (Takeuchi, et al., 2007; Teo, Bentley and Nguyen, 2020), selection based on collaboration and teamwork ability (Takeuchi, et al., 2007; Nassani, et al., 2023), and the job having an up-to-date description (Teo, Bentley and Nguyen, 2020). The second HRM function is training and development, which consists of HRM practices such as ensuring that training is continuous to support long-term employee potential (Takeuchi, et al., 2007; Teo, Bentley and Nguyen, 2020; Farrukh, et al., 2021), emphasizing on-the-job experiences (Takeuchi, et al., 2007; Farrukh, et al., 2021; Hassett, 2022), and a positive attitude to develop a committed and competent workforce (Farrukh, et al., 2021). The third HRM function is performance management, which consists of HRM practices such as performance appraisal based on quantifiable results (Takeuchi, et al., 2007; Teo, Bentley and Nguyen, 2020), compensations including high wages (Takeuchi, et al., 2007), and more than one potential position to promote employees (Teo, Bentley and Nguyen, 2020). According to this literature review focusing on research during the last three decades, the organizational HPWS is confirmed as a system of HRM practices. The next section reviews how this HPWS in the organizational context can be extended to develop the theory and practice of a similar HPWS for the project context to facilitate the enabling process of HPTs.

| Category | Characteristic(s)/variable(s) in literature with author(s) |

|---|---|

| General HRM system |

HPWS is an HRM system that: - enhances affective commitment and empowerment of employees to perform (Para-González, Jiménez-Jiménez, and Martínez-Lorente, 2019), - positively affects employees’ organizational citizenship behavior to perform (Zhang, et al., 2022), - plays a key role in the organization’s psychosocial safety climate for employees to perform (Miao, et al., 2020; Teo, Bentley, and Nguyen, 2020), - provides job security and guarantees to employees in the job (Teo, Bentley, and Nguyen, 2020), - allows employees in the jobs to make decisions and/or engage in decision-making participation (Teo, Bentley, and Nguyen, 2020; Nassani, et al., 2023), - keeps open communications with employees in this job (Teo, Bentley, and Nguyen, 2020), - enhances employees’ innovative behavior to perform (Miao, et al., 2020), - facilitates higher levels of customer orientation to enhance overall service performance (Jo, et al., 2023), - facilitates better human resource outcomes and enhances performance (Estiri, et al., 2021), - enhances customer satisfaction (Ogbonnaya and Valizade, 2018), - enhances return on investment (Katou, 2011; Estiri, et al., 2021), - enhances organizational coordination (Fu, et al., 2019; Estiri, et al., 2021), - enhances market share (Fu, et al., 2015; Bin Saeed, et al., 2019; Estiri, et al., 2021), - enhances workforce productivity (Huselid, 1995; MacDuffie, 1995; Guthrie, 2001; Datta, et al., 2005; Guthrie, et al., 2009; Estiri, et al., 2021), - influences employees’ job satisfaction and work engagement (Ogbonnaya and Valizade, 2018), and - facilitates employee resilience and engagement (Cooke, et al., 2019). |

| Specific HRM function |

HPWS is related to recruitment and selection to the extent of: - job role design is based on skills and capabilities and gives considerable importance to the staffing process (Takeuchi, et al., 2007; Teo, Bentley, and Nguyen, 2020), - having a comprehensive selection process with interviews (Takeuchi, et al., 2007; Teo, Bentley, and Nguyen, 2020; Nassani, et al., 2023), - selection is based on collaborative and teamwork ability (Takeuchi, et al., 2007; Nassani, et al., 2023), - selection involves screening many job candidates with very extensive efforts (Takeuchi, et al., 2007; Teo, Bentley, and Nguyen, 2020), - selection places priority on team member potential to learn (Takeuchi, et al., 2007), - job has an up-to-date description (Teo, Bentley, and Nguyen, 2020), and - the job description accurately describes the duties and responsibilities (Teo, Bentley, and Nguyen, 2020). |

| Specific HRM function |

HPWS is related to training and development to the extent of: - training is continuous to long-term employee potential (Takeuchi, et al., 2007; Teo, Bentley, and Nguyen, 2020; Farrukh, et al., 2021), - training programs are comprehensive and extensive (Takeuchi, et al., 2007; Teo, Bentley, and Nguyen, 2020; Farrukh, et al., 2021), - training programs emphasize on-the-job experiences and work engagement (Takeuchi, et al., 2007; Farrukh, et al., 2021; Hassett, 2022), - training programs are effective (Farrukh, et al., 2021), - transmitting a positive attitude about the organization’s desire to develop a committed and competent workforce (Farrukh, et al., 2021), and - training emphasizes employees’ mindset to motivate them to perform their tasks more flexibly (Nassani, et al., 2023). |

| Specific HRM function |

HPWS is related to performance management to the extent of: - performance appraisal is based on objectives and quantifiable results (Takeuchi, et al., 2007; Teo, Bentley and Nguyen, 2020; Zhu, Gao and Chen, 2022), - performance appraisals include management by objectives with mutual goal setting and quantifiable objectives (Takeuchi, et al., 2007; Teo, Bentley, and Nguyen, 2020), - performance appraisals include developmental feedback and learning from mistakes (Takeuchi, et al., 2007; Akhtar and Mittal, 2014; Nassani, et al., 2023), - incentives are based on team performance (Takeuchi, et al., 2007; Zhu, Gao, and Chen, 2022), - compensations have a reward system and high wages (Takeuchi, et al., 2007; Abugre and Nasere, 2020), - the incentive system is tied to skill-based pay (Takeuchi, et al., 2007; Zhu, Gao, and Chen, 2022), - having more than one potential position to promote employees to (Teo, Bentley, and Nguyen, 2020), - employee appraisals emphasize long-term development, career planning, and group-based achievements (Teo, Bentley, and Nguyen, 2020; Wang, et al., 2021), and - giving flexibility in performance appraisals (Ni, et al., 2020; Nassani, et al., 2023). |

Note. HRM, human resource management; HPWS, high-performance work system.

Project high-performance work system

As discussed above, the organizational HPWS consists of a system of HRM practices. Thus, the PHPWS can also be predicted as a system of project HRM practices due to the interchangeable nature of both contexts. However, three questions must be answered before conceptualizing this because the organizational and team contexts are two different team performance levels. These questions are as follows: (1) How do we consider a concept of a permanent organizational setting in a similar way to a temporary project setting? (2) Can we consider a concept that relates to a team performing in an organizational setting in a similar way to a team performing in a project setting? (3) How does the existing literature on project HRM practices support this argument?

The first and second questions can be answered together with the help of the literature on the definition of a project. According to the literature, a project is a temporary project organization (TPO) that has an internal temporary project environment that consists of actions in relation to time, tasks, and teams, as well as the external environment that is linked with making choices relating to the goals, expectations, and control of the permanent organization (Miles, 1964; Palisi, 1970; Goodman and Goodman, 1976; Goodman, 1981; Cleland and Kerzner, 1985; Lundin and Söderholm, 1995; Turner and Muller, 2003; Jacobsson, et al., 2013; Marchi and Sarcina, 2023). A project is temporary in reality, although both organizations and projects have organizational structures. A project also has the components or variables relating to communication, leadership, and motivation in a similar way to organizations in accordance with the organizational design theories (Cyert and March, 1963; Packendorff, et al., 1987). The general truth is that the HRM system facilitates employee performance in both organizational and project settings. Furthermore, the HRM system generally consists of HRM functions of recruitment and selection, training and development, and performance management in both organizational and project settings. Thus, if the HRM system is identified as the HPWS in the organizational context, extending the same idea to the project context is valid according to these analyses. Therefore, the same context of the organizational HPWS can be adapted to conceptualize the PHPWS, keeping the contextual-level difference.

The answer to the third question also supports the above conceptualization. For example, Bondarouk and Ruel (2008) indicated the influence of a project HRM system on improving the end-user behavior in terms of implementing new software to achieve high-performance information technology projects. Bellini and Canonico (2008) confirmed the role of the HRM system for the knowledge creation to perform in project settings. Furthermore, Abuazoom, et al. (2017) also confirmed the theoretical link between the HRM system and enhanced performance in construction projects. The project HRM system enhances performance according to this literature. Moreover, the literature provides evidence of three categories of HRM practices that support this argument: the opportunity-enhancing HRM practices, such as recruitment and selection; motivation-enhancing HRM practices, which comprise activities relating to compensation and incentives for motivating people to perform, such as performance management; and skill-enhancing HRM practices, which represent activities relating to enhancing people’s knowledge, skills, and competencies to perform, such as training and development (Takeuchi, et al., 2007; Jiang, et al., 2012; Chowhan, 2016; Nelson, et al., 2017). Thus, the PHPWS can be conceptualized as a system of HRM practices similar to the organizational context as the answers to the aforementioned three questions. The next section focuses on the research methodology adopted to test this concept empirically.

Research methodology

Research design and strategy

This study investigates the research question of what the PHPWS is for facilitating construction organizations to enable HPTs in their construction projects. Literature alone was insufficient to answer this question because of the limited available sources, and, thus, it was necessary to collect data from the practical construction industry. Generally, the design of a research study depends on the research questions (Bryman, 2015; Bryman and Bell, 2015; Saunders, et al., 2016). Therefore, it was helpful to identify the aforementioned research question clearly through gaps in the literature in order to adopt an appropriate research methodology. The PHPWS was adapted through the existing literature on organizational HPWSs, as discussed in the literature review section. For this purpose, the assumptions were made about the interchangeable nature of the organizational and project work environments. These assumptions indicate the ontological philosophical position of this study, that is, the nature of the reality of the interchangeable organizational and project environments in which the project teams perform (Saunders, et al., 2016). It was necessary to test the model fit of the PHPWS to confirm this adaptation to the construction project context. Accordingly, the variables of the PHPWS were needed to measure quantitatively for the analysis; hence, it was more appropriate to adopt a quantitative research approach (Creswell, 2014; Saunders, et al., 2016). Accordingly, the PHPWS variables were measured using a questionnaire survey, based on the belief that its complex teamwork environment in construction projects could be explored through a systematic and simplified approach. This means that the acceptable knowledge on project team performance in the PHPWS is constituted through direct observable variables that can be quantifiable (Bryman, 2015; Bryman and Bell, 2015). This shows the application of positivist perspectives in terms of the epistemological philosophical position of this research. Accordingly, a questionnaire survey among construction project team members was conducted.

Questionnaire development

In order to collect data using the questionnaire survey, the survey instrument had to be developed. If compatible survey instruments are available for the constructs in the related literature, the general research practice in the industry will be to use the existing item scales. Similarly, the existing survey instrument of the organizational HPWS used by Takeuchi, et al. (2007) was adapted. The authors’ 21-item scale was originally developed by Lepak and Snell (2002) for the HPWS in organizations. As discussed in the literature review, the nature of HRM practices in both organizational and project contexts is similar and interchangeable; thus, it was appropriate to adapt the item scales in the organizational context to the PHPWS by editing appropriate texts to retain the contextual-level differences. However, in order to adapt the survey instrument free from bias with validated psychometric properties to minimize the risk, the survey instrument was checked using three theoretical methods used in quantitative research (Field, 2009). The existing results of using this survey instrument in the literature were used for this purpose. The first method was to drop the item scales with loading factors below 0.5 using the available exploratory factor analysis (EFA) results. Accordingly, seven items out of 21 variables were dropped due to loading factors below 0.5 using the results of Takeuchi, et al. (2007). Generally, researchers used 0.3 or 0.4 as the threshold limit for the item reduction (Field, 2009), but 0.5 was used as the threshold limit for this purpose to minimize the risk of adapting the survey instrument from the organizational context to the project. The second test was dropping components for which Cronbach’s alpha was below 0.7, but no such components could be found. Cronbach’s alpha for the entire survey instrument was (α = 0.90) above the threshold limit of 0.7. The group of items with a negligible percentage of loading compared to the total survey instrument was reduced according to the third method, but no such cases were found either. The final survey instrument to measure the PHPWS consisted of 14-item scales. This was employed with a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) in the questionnaire. The final questionnaire also consisted of some demographic questions to collect information on respondents.

Sample selection

The sample selection is very important in a research study in order to have meaningful results to provide valuable implications to the industry. In this study, two selection criteria were used to select a strong sample. The first was the selection of survey respondents who were either working in the construction industry by the time of the survey or had worked in the industry previously, as the research investigation was for developing the PHPWS for the construction project context. In order to ensure this, the respondents were asked to answer the questions regarding a single construction project and the project team that they were working with at the time of the survey or had previously worked for. If the respondents were outside this scope, they were instructed not to complete the survey before the main questions. The second criterion was the selection of an appropriate sample size for the survey. Qualitative research typically focuses on in-depth study of relatively small purposeful samples, whereas quantitative methods typically depend on larger random samples (Patton, 1990). In terms of quantitative research, the sample size is very important because the strength of the output depends on it (Field, 2009). This study used two data analysis methods, the EFA and the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), as discussed in the next section. Accordingly, the minimum threshold of 150 responses for both the EFA and CFA was decided (Guadagnoli and Velicer, 1988; Field, 2009).

In the sample selection, no restrictions were placed on the nature, sector, and value of the projects, or the functions and sizes of the teams, as the research question did not depend on these factors. Snowball sampling was used to recruit respondents (Naderifar, Goli, and Ghaljaie, 2017) because no single place was available to undertake sampling of people working in the construction industry around the world. Hence, the participants were selected from anywhere in the world through known contacts and networking.

Results

Survey responses

By the time the survey closed, a total of 231 responses were received from the construction industry. Thereafter, data screening was conducted in Excel with the help of the facility provided by the online survey platform, and data were checked manually. After data preparation activities, as discussed below, the remaining sample for performing both the EFA and CFA tests was 221. The final sample consisted of 80% men and 20% women: 97% with educational attainment of a degree or above, 31% from the UK and Europe and 61% from Asian countries, 42% with more than 5 years of construction industry experience, and 46% working or had worked on projects with a budget of over USD10 million.

Data analysis strategy

The data analysis strategy in this study consisted of three stages. In the first stage, the initial data preparation was undertaken through data screening and missing data analysis. This was carried out manually as well as using the missing data analysis function provided in the IBM SPSS Statistics 28 software (Hair, et al. 2010).

The EFA was employed in the second stage. The EFA examines the underlying patterns and relationships of a large number of variables in a dataset and determines whether the information can be condensed or summarized in a smaller set of factors or components (Field, 2009). In this study, the PHPWS was measured using a 14-item scale, and 221 responses were used for this test. The item scales of the PHPWS were adapted from the organizational context. Thus, in order to investigate the suitability of variables for the construction project sector, it was appropriate to apply the EFA. The researchers also used the EFA for item reduction. Although the 14-item scale that had a reasonably good number of variables was used, the reduction of unloaded items that were not matched with the construction project context was a reason for applying the EFA. This test was performed using principal component analysis (PCA) with Varimax rotation in the IBM SPSS software. The PCA is used in quantitative research to extract important information from a large data table by means of a smaller set of new orthogonal variables called principal components. The displays of the patterns of similarity in these variables can be observed as points in maps in scatter diagrams (Abdi and Williams, 2010). Therefore, the PCA can be used to reduce cases by variables in a data table using principal components (Greenacre, et al., 2022). The important requirement is applying the PCA with appropriate rotation. Most researchers undertake factor loading using Varimax rotation to adjust the components in a way that makes the loadings either highly positive or negative, or zero, while components are kept uncorrelated or orthogonal (Corner, 2009). Similarly, the PCA with Varimax rotation was selected for this study, as it was compatible with the purpose. However, a number of statistical validation checks were conducted to ensure the data validity for drawing research conclusions. The first check was applying the threshold limit of 0.5 Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) to measure sampling adequacy to conduct the EFA (Field, 2009; Napitupulu, Kadar, and Jati, 2017). The second was checking the composite reliability of 0.7 Cronbach’s alpha, as this is the common threshold limit used in quantitative research. The communalities in the EFA provide information on how much variance the variables have in common or share and sometimes indicate how highly predictable the variables are from one another (Pruzek, 2005). The higher the communality value, the more the extracted factors will explain the variance of the item (Tavakol and Wetzel, 2020). The 0.4 communality threshold limit was used for the item reduction (Field, 2009).

The third stage of data analysis was conducting the CFA to test the model fit of the PHPWS with the final item scales remaining after performing the EFA. This was conducted using the IBM SPSS Amos 26 Graphics software. CFA is a method of uncovering the latent structure between an observed variable and hypothesized underlying constructs (Garson 2009). This often involves detecting which variables load onto which factors (Kim and Mueller, 1978). Using the above software, CFA was undertaken to assess the goodness of model fit of the PHPWS. Three indices recommended by Hu and Bentler (1999) and Nye (2023) were used to assess the model fit. First, the comparative fit index (CFI) was close to 1.00 (≥0.95), as given by Bentler (1990). Second, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) of Browne and Cudeck (1993) had a cutoff limit of ≤0.06 or was relaxed to ≤0.1. Third, the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) had a cutoff limit of ≤0.06 or was relaxed to ≤0.1.

Data preparation

After data screening with the help of an online survey platform, missing data analysis was conducted. The first step was to manually check in order to drop any response that was missing key demographic information or had a large amount of information. Through this manual audit, 10 responses were dropped, and six of them were totally empty. The reason for this may be that the respondents, after reading the initial instructions, abandoned the survey regarding a construction project to which they were linked or they might be from other project sectors. The second step was to use the Missing Value Analysis option in the IBM SPSS Statistics 28 software. In the results, the percentage of missing each item was checked with the threshold limit of dropping items that missed more than 10% of the required information (Hair, et al., 2010). None of the items had to be dropped, and the missing percentage was within the range of 0.5% to 1.4% where four items had shown 1.4%. The pattern of missing data was checked using the Missing Completely At Random (MCAR) test in the SPSS software. It was confirmed that the missing data pattern was MCAR because Little’s overall test of missing data was not significant (Little’s MCAR test: chi-square = 142.290, df = 120, Significance = 0.081), showing a score above 0.05 (Tabachnick and Fidell, 2007). Next, data imputation was undertaken using expectation maximization in SPSS. The remaining sample after completing data preparation for applying the EFA was 221 responses.

Exploratory factor analysis results

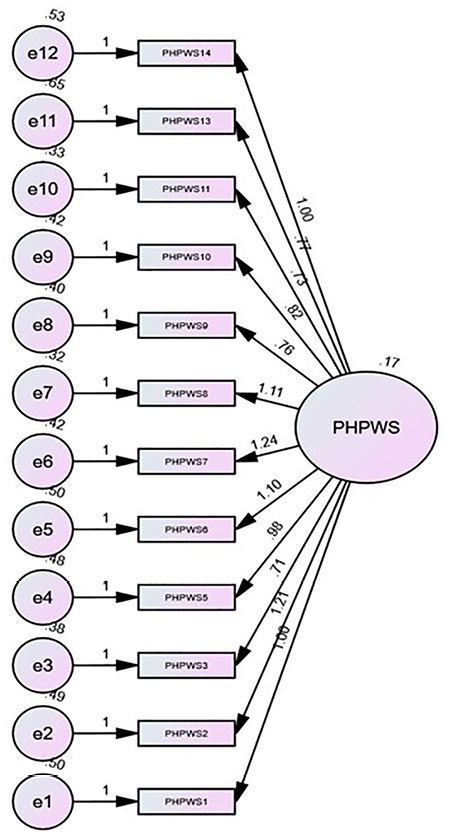

The EFA was conducted using PCA with Varimax rotation in the IBM SPSS software. The KMO measure of sampling adequacy for this PHPWS survey instrument was 0.820, and, thus, the selected sample fulfilled the threshold limit of 0.5 (Field, 2009). This means that the data collection sample was sufficient to draw valid conclusions in this study. The scree plot was also satisfactory, as shown in Figure 1. The EFA results indicated that all item scales were loaded meaningfully, as shown in Table 2. Two variables that had not been loaded properly were dropped using the threshold limit of 0.4 as used in many quantitative research studies (Field, 2009). The final survey instrument of the PHPWS consisted of 12-item scales for the construction project context. The final PHPWS survey instrument had Cronbach’s alpha of 0.804, and this was greater than the 0.7 threshold limit. According to the scree plot (see Figure 1), there may be a possibility to identify three components, although the diagram does not show significant differences from the second component onward. The results presented eigenvalues of 4.216 (30.1%), 1.462 (10.4%), and 1.276 (9.1%) for the initial three components in terms of using 1.0 as the threshold limit of an eigenvalue. However, none of them was loaded meaningfully, showing distinctively different components of the PHPWS due to overlaps between them in both the component matrix and the rotated component matrix, as shown in Table 3. Therefore, the survey instrument did not confirm meaningful components of the PHPWS applicable to the construction project sector. Thus, the PHPWS consisting of 12-item scales was taken as a single construct without components to test its model fit when applying the CFA.

Figure 1. PCA scree plot of the PHPWS. PCA, principal component analysis; PHPWS, project high-performance work system.

Note. EFA, exploratory factor analysis; PHPWS, project high-performance work system.

*Dropped due to the below threshold limit of 0.4 (Field, 2009).

Note. EFA, exploratory factor analysis; PHPWS, project high-performance work system.

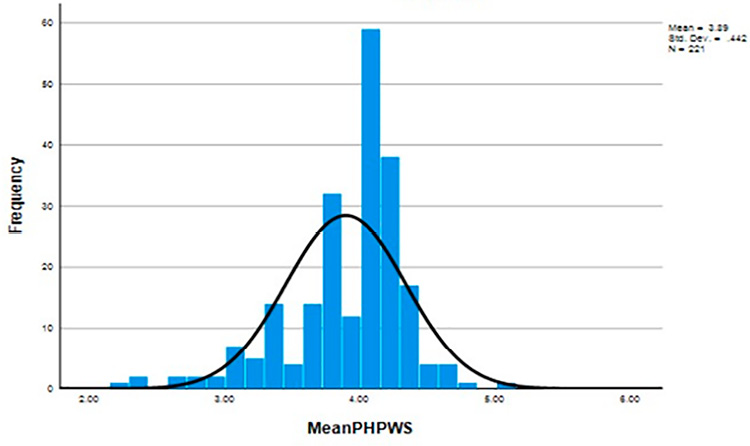

Confirmatory factor analysis results

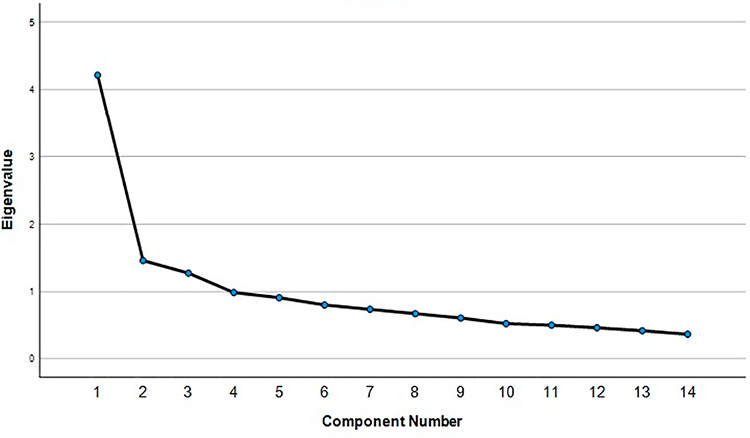

The CFA was performed using the IBM SPSS Amos 26 Graphics software to test the model fit of the PHPWS in accordance with the data analysis strategy described above. The test was carried out using the 12-item scale of the PHPWS that remained after the EFA. The model fit of the PHPWS was tested as a single construct because no components could be identified using the EFA. The histogram plot was also checked (see Figure 2) to confirm the normal distribution before conducting the CFA (Hair, et al., 2010).

Figure 2. Histogram of the PHPWS. PHPWS, project high-performance work system.

Table 4 and Figure 3 show the path diagram and the results of this test. According to the results, the degree of freedom was above zero (df > 0). This gave a good sign, indicating that the model could be estimated and that the model fit could be assessed (Hu and Bentler, 1999; Nye, 2023). Next, the results of a few model fit indices were checked, rather than being limited to one index (see Table 4). The results of the CFI and Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) were close to 1.00 in a reasonably satisfactory way but indicated 0.776 and 0.731, respectively, slightly below the cutoff limit of ≥0.95 or were relaxed to 0.90 (Hu and Bentler, 1999; Nye, 2023). However, the results of the RMSEA were marginally satisfactory, showing the value of 0.102, approximately fulfilling the cutoff limit of ≤0.06 or was relaxed to ≤0.1 (Hu and Bentler, 1999; Nye, 2023). The model fit was successfully satisfactory, showing the SRMR index value of 0.049, fulfilling the cutoff limit of ≤0.06 or was relaxed to ≤0.1 (Hu and Bentler, 1999; Nye, 2023). The model fit can be confirmed according to these indications. However, these results are further discussed in the discussion of findings section because the CFA model fit indices depend on many factors.

Figure 3. Path diagram of CFA. CFA, confirmatory factor analysis.

Note. CFA, confirmatory factor analysis.

Discussion of findings

The key finding of this study is the confirmation of the PHPWS as a single construct that consists of variables of HRM practices that are relevant to the construction project context. This lends credibility to the authors who have contributed to developing this concept in the literature (see Table 1 and literature review). As discussed in the introduction, there are a plethora of studies in the literature regarding the organizational HPWS, but only limited attention has been given to identifying the variables of the PHPWS, particularly for the construction project context. As such, this study developed the PHPWS, adapted from the organizational HPWS, to be further validated with primary data from practical projects while retaining the contextual-level difference. As discussed in the literature review, three questions were answered, supporting the concept for this adaptation and giving credibility for the authors who contributed to theory development in terms of TPOs and organizational design in the literature (e.g., Cyert and March, 1963; Miles, 1964; Palisi, 1970; Goodman and Goodman, 1976; Goodman, 1981; Cleland and Kerzner, 1985; Packendorff, et al., 1987; Lundin and Söderholm, 1995; Turner and Muller, 2003; Jacobsson, et al., 2013; Marchi and Sarcina, 2023). The findings in this study confirm the conceptualization of the PHPWS as the project HRM system as the same in organizations. This finding adds value to the noteworthy contributions in the literature (e.g., Takeuchi, et al., 2007; Bellini and Canonico, 2008; Bondarouk and Ruel, 2008; Jiang, et al., 2012; Chowhan, 2016; Abuazoom, et al., 2017; Nelson, et al., 2017). The EFA results confirmed the PHPWS as a single construct that consists of 12 variables, acknowledging the original authors who developed or further validated this survey instrument in the literature (Lepak and Snell, 2002; Takeuchi, et al., 2007). Although factor rotation through PCA indicated the possibility of identifying a few components according to EFA results, the factors were not meaningfully loaded to identify distinctively different components due to overlaps between components. This may be due to overlapping management contexts in HRM practices that could be further investigated through future research.

Although the PHPWS could be confirmed, the CFA results gave slightly contradictory results regarding the model fit of the PHPWS with the 12-item scale (see Table 4). The good indication showed df > 0 by confirming that the model could be estimated and the model fit could be assessed. The results also fulfilled at least two model fit indices, while others were approximately fulfilled or showed better indications. The χ2 = 000 (<0.05) was significant, indicating that the model did not fit the data well. Both the CFI and TLI were also not within the accepted cutoff limits but approximately close to them. However, both the RMSEA and SRMR fulfilled either accepted or relaxed cutoff limits, confirming the model fit. Although the requirements to fulfill the model fit according to the chi-square test were not met, in practice, this is not considered a very useful model fit index by most researchers because it can be affected by several factors, such as sample size, model size, distribution of variables, and omission of variables (Hayduk, et al., 2007). Therefore, the chi-square index cannot be taken as an indication to decide the model fit of the PHPWS because this study had a relatively small sample size of 221, although it was above the threshold limit. TLI is a relative fit index. According to the above discussion related to the chi-square, TLI may also not be a good index for this study because it also depends on the sample size. The CFI is a noncentrality-based index that depends on the sample size, but this is less sensitive to sample size than the chi-square. Although the CFI value did not fulfill the cutoff limit, it was approximately 0.9. Generally, the CFI value ranges from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating a better model fit. However, both the RMSEA and SRMR indices fulfilled the cutoff or relaxed cutoff limits, and thus, the model fit can be confirmed. The contradictory CFA results may be due to sample size or overlapping between variables, similar to the above discussion on component identification during the EFA, or other reasons, and this could be further investigated in future research.

The literature shows that the HPWS facilitates the enabling process of HPTs, and this is built up with a system of HRM practices in the organizational context. The above findings confirmed the same for the project context. This confirmation also adds value to the noteworthy views in the literature, indicating that the HPWS depends on employees’ behavior, commitment, empowerment, and relations because the HRM system is directly linked with these aspects (e.g., Para-González, Jiménez-Jiménez, and Martínez-Lorente, 2019; Miao, et al., 2020). However, investigating other aspects that can facilitate the enabling process of HPTs in a general project environment could be a future research direction.

Conclusions

This study concluded that the PHPWS is a single construct that consists of 12-item scales of HRM practices, and this study achieved its aims and objectives. This conclusion was made empirically, confirming the adapted PHPWS from the organizational HPWS in the literature. The EFA results supported this conclusion by meaningfully loading the factors. Although some model fit indices showed slightly unusual values—due to sample size limitations or other factors—the CFA results indicate that the PHPWS model has an acceptable fit based on reasonably satisfactory indices. In conclusion, the PHPWS makes a significant contribution to the construction industry. The construction project organizations can understand the importance of implementing the HRM systems with better HRM practices in their projects to facilitate the enabling process of HPTs. Thus, this finding provides clear evidence and much-needed clarity on the importance of a strong project HRM system for enabling HPTs in construction projects.

This research is one of the first studies confirming the PHPWS for the context of construction projects and, thus, makes a significant theoretical contribution. From the construction management research perspective, this is also an original contribution to the body of knowledge. Evidence of the PHPWS is no longer anecdotal, and the construction organizations and project team managers can identify what aspects are to be prioritized in their HRM system. This paper also contributes to knowledge on the methodological standpoint by providing an empirically validated PHPWS as a survey instrument with 12 variables. Future studies can employ this survey instrument to develop further theories and practices.

However, this study had two limitations. The first limitation was the reasonably small sample size for applying the EFA and CFA. However, extra care was taken to apply a sample size above the accepted threshold limit. Statistical validation tests to confirm the adequacy of the sample size were also checked and had satisfactory results. However, slightly unusual results in terms of a few model fit indices in the CFA, as well as in the process of identifying the components of the PHPWS through the EFA, were detected. This may be either an implication of the overlapping HRM practices between variables in terms of management perspectives or due to other reasons that are outside the scope of this paper. The second limitation was reviewing only the PHPWS, which consists of HRM practices to enable HPTs, as exploring other project environmental aspects for this purpose was outside the scope of this study. It is recommended that future studies explore the overlapping variables in the unsatisfied components of the PHPWS and identify other project environmental aspects to enable HPTs.

References

Abdi, H. and Williams, L.J., 2010. Principal component analysis. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Computational Statistics, 2(4), pp.433-459. https://doi.org/10.1002/wics.101

Abuazoom, M. M., Hanafi, H. B. and Ahmad, Z. Z., 2017. Influence of HRM practices on project performance: conceptual framework. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 7(3), pp.47-54.

Abugre, J.B. and Nasere, D., 2020. Do high-performance work systems mediate the relationship between HR practices and employee performance in multinational corporations (MNCs) in developing economies?. African Journal of Economic and Management Studies, 11(4), pp.541-557. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJEMS-01-2019-0028

Ahmed, M.O., El-Adaway, I.H. and Caldwell, A., 2024. Comprehensive understanding of factors impacting competitive construction bidding. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 150(4), p.04024017. https://doi.org/10.1061/JCEMD4.COENG-14090

Akhtar, M., Mittal, R.K., 2014. Strategic flexibility, information system flexibility and enterprise performance management. In Organizational Flexibility and Competitiveness;, Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, pp. 41-51. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-81-322-1668-1_4

Anjomshoa, E., 2024. Key performance indicators of construction companies in branding products and construction projects for success in a competitive environment in Iran. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 31(5), pp.2151-2175. https://doi.org/10.1108/ECAM-08-2023-0852

Ashton, D. N. and Sung, J., 2002. Supporting workplace learning for high performance working. International Labour Organization.

Bellini, E. and Canonico, P., 2008. Knowing communities in project driven organizations: analysing the strategic impact of socially constructed HRM practices. International Journal of Project Management, 26(1), pp.44-50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2007.08.007

Bellocchi, A. and Travaglini, G., 2023. A quantitative analysis of the European construction sector: productivity, investment, and competitiveness. In Digital Transitions and Innovation in Construction Value Chains, Edward Elgar, pp.18-48. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781803924045.00009

Bentler PM., 1990. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol Bull, 107(2), pp.238–246. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.107.2.238

Bin Saeed, B., Afsar, B., Shahjehan, A. and Imad Shah, S., 2019. Does transformational leadership foster innovative work behavior? The roles of psychological empowerment, intrinsic motivation, and creative process engagement. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istrazivanja, 32(1), pp.254-281. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2018.1556108

Blay Jnr, A.V.K., Kukah, A.S.K., Opoku, A. and Asiedu, R., 2023. Impact of competitive strategies on achieving the sustainable development goals: context of Ghanaian construction firms. International Journal of Construction Management, 23(13), pp.2209-2220. https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2022.2048343

Bolton, A., Butler, L., Dabson, I., Enzer, M., Evans, M., Fenemore, T., Harradence, F., Keaney, E., Kemp, A., Luck, A. and Pawsey, N., 2018. Gemini principles.

Bondarouk, T. V. and Ruël, H. J., 2008. HRM systems for successful information technology implementation: evidence from three case studies. European Management Journal, 26(3), pp.153-165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2008.02.001

Bowen, D. E. and Ostroff, C., 2004. Understanding HRM–firm performance linkages: the role of the “strength” of the HRM system. Academy of Management Review, 29(2), pp.203-221. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2004.12736076

Boxall, P. and Macky, K., 2009. Research and theory on high‐performance work systems: progressing the high‐involvement stream. Human Resource Management Journal, 19(1), pp.3-23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-8583.2008.00082.x

Browne, M.W., Cudeck, R., 1993. Alternative ways of assessing fit. In Bollen KA, Long JS (Eds.). Testing structural equation models. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp.136-162.

Bryman, A., 2015. Social research methods. Oxford University Press, UK.

Bryman, A. and Bell, E., 2015. Business research methods. Oxford University Press, UK.

Chancellor, W., 2015. Drivers of productivity: a case study of the Australian construction industry. Construction Economics and Building, 15(3), pp85-97. https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v15i3.4551

Chen, Z.S., Liang, C.Z., Xu, Y.Q., Pedrycz, W. and Skibniewski, M.J., 2024. Dynamic collective opinion generation framework for digital transformation barrier analysis in the construction industry. Information Fusion, 103, p.102096. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inffus.2023.102096

Chiang, Y. H. and Hsu, C. C., 2012. Perceived high performance work system and individual creativity performance in work teams, Management of Innovation and Technology (ICMIT), IEEE International Conference, Jun 2012, pp.532-537. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICMIT.2012.6225862

Chowhan, J., 2016. Unpacking the black box: understanding the relationship between strategy, HRM practices, innovation and organizational performance. Human Resource Management Journal, 26(2), pp.112-133. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12097

Cleland, D. I. and Kerzner, H., 1985. A project management dictionary of terms, Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Coggins, J., Teng, B. and Rameezdeen, R., 2016. Construction insolvency in Australia: reining in the beast. Construction Economics and Building, 16(3), pp.38-56. https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v16i3.5113

Cooke, F.L., Cooper, B., Bartram, T., Wang, J. and Mei, H., 2019. Mapping the relationships between high-performance work systems, employee resilience and engagement: a study of the banking industry in China. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 30(8), pp.1239-1260. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2015.1137618

Corner, S., 2009. Choosing the right type of rotation in PCA and EFA. JALT Testing & Evaluation SIG Newsletter, 13(3), pp.20-25.

Creswell, J. W., 2014. Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 4th ed. Sage publications.

Cyert, R.M. and March, J.G., 1963. A behavioral theory of the firm. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Danford, A., Richardson, M., Steward, P., Tailby, S. and Upchurch, M., 2005. Partnership and the high performance workplace: work and employment relations in the aerospace industry. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230501997

Daniel, E.I., Pasquire, C., Dickens, G. and Ballard, H.G., 2017. The relationship between the last planner system and collaborative planning practice in UK construction. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 24(3), pp.407-425. https://doi.org/10.1108/ECAM-07-2015-0109

Datta, D.K., Guthrie, J.P. and Wright, P.M., 2005. HRM and labor productivity: does industry matter. Academy of Management Journal. 48(1), pp.135–145. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2005.15993158

de Valence, G., 2011. Defining an industry: what is the size and scope of the Australian building and construction industry. Construction Economics and Building, 1(1), pp.53-65. https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v1i1.2280

Deep, S., Gajendran, T. and Jefferies, M., 2021. A systematic review of enablers of collaboration among the participants in construction projects. International Journal of Construction Management, 21(9), pp. 919–931. https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2019.1596624

Estiri, M., Heidary Dahooie, J., Salar Vanaki, A., Banaitis, A. and Binkytė-Vėlienė, A., 2021. A multi-attribute framework for the selection of high-performance work systems: the hybrid DEMATEL-MABAC model. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 34(1), pp.970-997. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2020.1810093

Farrukh, M., Khan, M.S., Raza, A. and Shahzad, I.A., 2021. Influence of high-performance work systems on intrapreneurial behavior. Journal of Science and Technology Policy Management, 12(4), pp.609-626. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSTPM-05-2020-0086

Field, A., 2009. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS. 3rd ed. Sage publications.

Fu, N., Bosak, J., Flood, P.C. and Ma, Q., 2019. Chinese and Irish professional service firms compared: linking HPWS, organizational coordination, and firm performance. Journal of Business Research, 95, pp.266–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.08.021

Fu, N., Flood, P.C., Bosak, J., Morris, T., and O’Regan, P., 2015. How do high performance work systems influence organizational innovation in professional service firms. Employee Relations, 37(2), pp.209-231. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-10-2013-0155

Garson, G.D., 2009. Factor Analysis from Statnotes: Topics in Multivariate Analysis. Available at http://faculty.chass.ncsu.edu/garson/pa765/statnote.htm

Gong, Y., Chang, S. and Cheung, S.Y., 2010. High performance work system and collective OCB: a collective social exchange perspective. Human Resource Management Journal, 20(2), pp.119-137. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-8583.2010.00123.x

Goodman, A. and Goodman, L.P., 1976. Some management issues in temporary systems: a study of professional development and manpower-the theatre case. Administrative Science Quarterly, 21(3), pp.494-501. https://doi.org/10.2307/2391857

Goodman, R.A., 1981. Temporary systems: professional development, manpower utilization, task effectiveness, and innovation. New York: Praeger.

Greenacre, M., Groenen, P.J., Hastie, T., d’Enza, A.I., Markos, A. and Tuzhilina, E., 2022. Principal component analysis. Nature Reviews Methods Primers, 2(1), p.100. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43586-022-00184-w

Guadagnoli, E. and Velicer, W.F., 1988. Relation to sample size to the stability of component patterns. Psychological Bulletin, 103(2), p.265. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.103.2.265

Guest, D.E. and Bos-Nehles, A.C., 2013. HRM and performance: the role of effective implementation. In HRM and performance: achievements and challenges, Wiley-Blackwell, pp.79-96.

Guthrie, J.P., 2001. High involvement work practices, turnover and productivity: evidence from New Zealand. Academy of Management Journal, 44(1), pp.180-190. https://doi.org/10.2307/3069345

Guthrie, J.P., Flood, P.C., Liu, W. and MacCurtain, S., 2009. High performance work systems in Ireland: human resource and organizational outcomes. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 20(1), pp.112-125. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190802528433

Hair, J.F., Black, W.C., Babin, B.J., Anderson, R.E. and Tatham, R.L., 2010. Multivariate data analysis, 7th ed. Pearson. New Jersey.

Han, J., Sun, J.M. and Wang, H.L., 2020. Do high performance work systems generate negative effects? how and when?. Human Resource Management Review, 30(2), p.100699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2019.100699

Hassett, M.P., 2022. The effect of access to training and development opportunities, on rates of work engagement, within the US federal workforce. Public Personnel Management, 51(3), pp.380-404. https://doi.org/10.1177/00910260221098189

Hayduk, L., Cummings, G., Boadu, K., Pazderka-Robinson, H. and Boulianne, S., 2007. Testing! testing! one, two, three–Testing the theory in structural equation models!. Personality and Individual Differences, 42(5), pp.841-850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.10.001

Hu, L. and Bentler, P.M., 1999. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modelling, 6 (1), pp.1-55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Hughes, J., 2008. The high-performance paradigm: a review and evaluation. Learning as Work Research Paper No. 16. Cardiff: Cardiff University School of Social Sciences.

Huselid, M.A., 1995. The impact of human resource management practices on turnover, productivity, and corporate financial performance. Academy of Management Journal, 38, pp.635-672. https://doi.org/10.2307/256741

Jacobsson, M., Burström, T. and Wilson, T.L., 2013. The role of transition in temporary organizations: linking the temporary to the permanent. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, 6(3), pp.576-586 https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMPB-12-2011-0081

Jiang, K., Lepak, D.P., Hu, J. and Baer, J.C., 2012. How does human resource management influence organizational outcomes: a metaanalytic investigation of mediating mechanisms, Academy of Management Journal, 55(6), pp.1264-1294. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0088

Jo, H., Aryee, S., Hsiung, H.H. and Guest, D., 2023. Service-oriented high-performance work systems and service role performance: applying an integrated extended self and psychological ownership framework. Human Relations, 76(1), pp.168-196. https://doi.org/10.1177/00187267211035656

Katou, A., 2011. Test of a causal human resource management-performance linkage model: evidence from the Greek manufacturing sector. International Journal of Business Science & Applied Management (IJBSAM), 6(1), pp.16-29. https://doi.org/10.69864/ijbsam.6-1.64

Kehoe, R.R. and Wright, P.M., 2013. The impact of high-performance human resource practices on employees’ attitudes and behaviors. Journal of Management, 39(2), pp.366-391. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310365901

Kim, J.O. and Mueller, C.W., 1978. Factor analysis: statistical methods and practical issues. Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412984256

Lepak, D.P. and Snell, S.A., 2002. Examining the human resource architecture: the relationships among human capital, employment, and human resource configurations. Journal of Management, 28, pp.517-543. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-2063(02)00142-3

Liu, Y., Gan, L., Cai, W. and Li, R., 2024. Decomposition and decoupling analysis of carbon emissions in China’s construction industry using the generalized Divisia index method. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 104, p.107321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2023.107321

López-Malest, A., Gabor, M.R., Panait, M., Brezoi, A. and Veres, C., 2024. Green innovation for carbon footprint reduction in construction industry. Buildings, 14(2), p.374. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14020374

Lundin, R.A. and Söderholm, A., 1995. A theory of the temporary organization, Scandinavian Journal of Management, 11(4), pp.437-455. https://doi.org/10.1016/0956-5221(95)00036-U

MacDuffie, J., 1995. Human resource bundles and manufacturing performance: Organizational logic and flexible production systems in the world auto industry. ILR Review, 48(2), pp.197-221. https://doi.org/10.1177/001979399504800201

Marchi, S. and Sarcina, R., 2023. Temporariness in appreciative reflection: managing participatory and appreciative, action and reflection projects through temporary organizations. In Enabling Reflective Learning in Lifelong Career Guidance, Routledge, pp.9-26. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003416852-2

Miao, R., Lu, L., Cao, Y. and Du, Q., 2020. The high-performance work system, employee voice, and innovative behavior: the moderating role of psychological safety. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(4), p.1150. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17041150

Miles, M.B., 1964. On temporary systems. In: Miles, M. B. (Ed.), Innovation in Education, New York: Teachers College Press, pp.437-490.

Naderifar, M., Goli, H. and Ghaljaie, F., 2017. Snowball sampling: a purposeful method of sampling in qualitative research. Strides in Development of Medical Education, 14(3). https://doi.org/10.5812/sdme.67670

Napitupulu, D., Kadar, J.A. and Jati, R.K., 2017. Validity testing of technology acceptance model based on factor analysis approach. Indonesian Journal of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, 5(3), pp.697-704. https://doi.org/10.11591/ijeecs.v5.i3.pp697-704

Nassani, A.A., Hussain, H., Rosak-Szyrocka, J., Vasa, L., Yousaf, Z. and Haffar, M., 2023. Analyzing the leading role of high-performance work system towards strategic business performance. Sustainability, 15(7), p.5697. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15075697

Nelson, S., White, C.F., Hodges, B.D. and Tassone, M., 2017. Interprofessional team training at the prelicensure level: a review of the literature. Academic Medicine, 92(5), pp.709-716. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001435

Ni, G.; Xu, H.; Cui, Q.; Qiao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, H., Hickey, P.J., 2020. Influence mechanism of organizational flexibility on enterprise competitiveness: the mediating role of organizational innovation. Sustainability, 13, p.176. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010176

Nye, C.D., 2023. Reviewer resources: confirmatory factor analysis. Organizational Research Methods, 26(4), pp.608-628. https://doi.org/10.1177/10944281221120541

Ogbonnaya, C., Daniels, K., Connolly, S. and van Veldhoven, M., 2017. Integrated and isolated impact of high-performance work practices on employee health and well-being: a comparative study. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(1), p.98. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000027

Ogbonnaya, C. and Valizade, D., 2018. High performance work practices, employee outcomes and organizational performance: a 2-1-2 multilevel mediation analysis. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 29(2), pp.239-259. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1146320

Olatunji, O. A. and Sher, W., 2014. Perspectives on modelling BIM-enabled estimating practices. Construction Economics and Building, 14(4), pp.32-53. https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v14i4.4102

Omopariola, E.D., Olanrewaju, O.I., Albert, I., Oke, A.E. and Ibiyemi, S.B., 2024. Sustainable construction in the Nigerian construction industry: unsustainable practices, barriers and strategies. Journal of Engineering, Design and Technology, 22(4), pp.1158-1184. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEDT-11-2021-0639

Packendorff, J., Lundin, I.R. and Packendorff, J., 1987. Temporary organizing: integrating organization theory and project management. Project Management, pp.21-41.

Pak, J. and Kim, S., 2016. Team manager’s implementation, high performance work systems intensity, and performance: a multilevel investigation. Journal of Management. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316646829

Palisi, B. J., 1970. Some suggestions about the transitory-permanence dimension of organizations. British Journal of Sociology, 21, pp.200-206. https://doi.org/10.2307/588408

Para-González, L., Jiménez-Jiménez, D. and Martínez-Lorente, Á.R., 2019. Do SHRM and HPWS shape employees’ affective commitment and empowerment. In Evidence-based HRM: a Global Forum for Empirical Scholarship, Emerald Publishing Limited, 7(3), pp.300-324. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBHRM-01-2019-0004

Patton, M.Q., 1990. Qualitative evaluation and research methods. SAGE Publications, inc.

Pruzek, R., 2005. Factor analysis: exploratory. Encyclopedia of Statistics in Behavioral Science. https://doi.org/10.1002/0470013192.bsa211

Rani, N.I.A., Ismail, S., Mohamed, Z. and Mat Isa, C.M., 2023. Competitiveness framework of local contractors in the Malaysian construction industry towards globalisation and liberalisation. International Journal of Construction Management, 23(3), pp.553-564. https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2021.1895485

Sankaran, S., Müller, R., and Drouin, N., 2020. Creating a sustainability sublime to enable megaprojects to meet the United Nations sustainable development goals. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 37(5), pp.813–826. https://doi.org/10.1002/sres.2744

Saunders, M.N., Lewis, P. and Thornhill, A., 2016. Research methods for business students, 7th ed. Pearson Education, Harlaw, England.

Shin, D. and Konrad, A.M., 2017. Causality between high-performance work systems and organizational performance. Journal of Management, 43(4), pp.973-997. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314544746

Siddique, M., Procter, S. and Gittell, J.H., 2019. The role of relational coordination in the relationship between high-performance work systems (HPWS) and organizational performance. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 6(4), pp.246-266. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOEPP-04-2018-0029

Statista., 2019. Construction industry spending worldwide from 2014 to 2019, with forecasts from 2020 to 2035. https://www.statista.com/statistics/788128/construction-spending-worldwide/

Tabachnick, B.G. and Fidell, L.S., 2007. Experimental designs using ANOVA, Belmont, CA: Thomson/Brooks/Cole.

Takeuchi, R., Chen, G. and Lepak, D.P., 2009. Through the looking glass of a social system: cross‐level effects of high‐performance work systems on employees’ attitudes. Personnel Psychology, 62(1), pp.1-29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2008.01127.x

Takeuchi, R., Lepak, D.P., Wang, H. and Takeuchi, K., 2007. An empirical examination of the mechanisms mediating between high-performance work systems and the performance of Japanese organizations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(4), p.1069. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.4.1069

Tavakol, M. and Wetzel, A., 2020. Factor analysis: a means for theory and instrument development in support of construct validity. International Journal of Medical Education, 11, p.245. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.5f96.0f4a

Teo, S.T., Bentley, T. and Nguyen, D., 2020. Psychosocial work environment, work engagement, and employee commitment: a moderated, mediation model. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 88, p.102415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.102415

Turner, J.R. and Müller, R., 2003. On the nature of the project as a temporary organization. International Journal of Project Management, 21(1), pp.1-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0263-7863(02)00020-0

Van De Voorde, K., Paauwe, J. and Van Veldhoven, M., 2012. Employee well‐being and the HRM - organizational performance relationship: a review of quantitative studies. International Journal of Management Reviews, 14(4), pp.391-407. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2011.00322.x

Wang, Y., Cao, Y., Xi, N., Chen, H., 2021. High-performance work system, strategic flexibility, and organizational performance. The Moderating Role of Social Networks, 12, p.670132. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.670132

Zhang, B., Liu, L., Cooke, F.L., Zhou, P., Sun, X., Zhang, S., Sun, B. and Ba, Y., 2022. The boundary conditions of high-performance work systems-organizational citizenship behavior relationship: a multiple-perspective exploration in the Chinese context. Organizational Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.743457

Zheng, X., Deng, J., Song, X., Ye, M. and Luo, L., 2024. Examining the nonlinear relationships of corporate social responsibility, innovation and construction firm performance: the moderating role of construction firms’ competitive position. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 31(4), pp.1517-1538. https://doi.org/10.1108/ECAM-03-2022-0286

Zhu, F., Gao, Y. and Chen, X., 2022. Tough love: impact of high-performance work system on employee innovation behavior. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, p.919993. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.919993