Construction Economics and Building

Vol. 25, No. 1

March 2025

RESEARCH ARTICLE

The Role of Project Delivery Methods on the Execution of Construction Projects in the Kenyan Judiciary

John Fredrick Okello1,*, Omondi Bowa2, Joash Migosi3

1 University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya, jfokello2013@gmail.com

2 University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya, bowa2016@gmail.com

3 University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya, jmigosi@gmail.com

Corresponding author: John Fredrick Okello, Department of Management Science and Project Planning, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya, jfokello2013@gmail.com

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v25i1.9298

Article History: Received 20/08/2024; Revised 18/11/2024; Accepted 25/12/2024; Published 31/03/2025

Citation: Okello, J. F., Bowa, O., Migosi, J. 2025. The Role of Project Delivery Methods on the Execution of Construction Projects in the Kenyan Judiciary. Construction Economics and Building, 25:1, 49–68. https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v25i1.9298

Abstract

The Kenyan Judiciary’s construction industry experienced a significant upturn with 63 major court projects funded by the World Bank and Kenya Government from 2012 to 2021. However, these projects faced delays and scope changes, affecting performance indicators like time, cost, site dispute, and quality. The study hypothesized that project delivery methods have no significant influence on the execution of court-building projects in relation to time, cost, site disputes, and quality. Reliability was tested using Cronbach’s alpha technique, and validity was tested using principal component analysis (PCA). This study combined the collection and analysis of quantitative and qualitative data using a mixed-methods approach. Sixty-three projects were surveyed using a convergent parallel mixed-survey design. Document analysis was used to obtain secondary data, and questionnaires and interview guides were used to collect the primary data. Correlation and regression analysis techniques were used for inferential statistical analysis. The slope coefficients were considered significant at p ≤ 0.05. Thematic and document analyses were applied to the qualitative data to triangulate the findings with the quantitative data. According to the study, project delivery methods significantly influenced the execution of construction projects in terms of quality, cost, and site disputes, but not time. The study further highlights the need for flexible, context-specific project delivery approaches in the Kenyan Judiciary to ensure timely completion of court-building infrastructure.This research offers helpful information concerning the use of appropriate delivery methods to scholars, practitioners of project and construction management, policymakers, and other parties involved in implementing the Kenyan Judiciary’s court-building infrastructure.

Keywords

Project Delivery Methods; Execution of Construction Projects; Kenyan Judiciary; Performance Metrics; Mixed-Methods Research

Introduction

The construction sector is essential for infrastructure development, job production, and economic expansion (Holloway, 2018; Odoko, 2018; Pheng and Hou, 2019). The construction industry plays a crucial role in shaping the built environment and supporting other industries (Azhar, Kang and Ahmad, 2014). The Kenyan Judiciary benefited from the construction industry when the World Bank and Kenya Government funded the construction of 63 major court construction projects from 2012 to 2021 (Judiciary Transformation Framework, 2012).

These projects were originally planned for completion by December 2018 but, on average, had more than 12 months of delay in their contract period, and the scope had to be changed for all of them so as to be delivered within the original contract sum (Sojar, 2019). Among the delivery delays and challenges experienced during the project execution were the re-working of some building works concerning quality issues, non-payment of suppliers by main contractors leading to site disputes, delays in honoring payment certificates, setbacks resulting from misinterpretation of the public procurement act requirements, delays emerging from the reduction of the Judiciary development budget, and difficulties in managing the numerous teams involved in the project implementation process (Sojar, 2019).

One of the key project delivery attributes that can lead to improved project performance is using the appropriate project delivery method. Ahmed and El-Sayegh (2020) reported that one of the most crucial managerial choices is selecting the best project delivery strategy because it directly affects critical performance metrics including cost, quality, schedule, and safety, hence influencing the project’s success. Every project is implemented through a project delivery method from initiation to completion. The project delivery method thus describes how the project participants are structured to interact when implementing the targets and objectives of the client (Raykar and Ghadge, 2016; Akob, Hipni and Rosly, 2019; Ktaish and Hajdu, 2022). The construction industry relies on various project delivery methods to bring projects from conception to completion (Trach, Połoński and Hrytsiuk, 2019; Salim and Mahjoob, 2020; Ahmed and El-Sayegh, 2020).

Constructs that can be used to evaluate the impact of project delivery methods on project performance include contract responsibility, the roles and responsibilities of the parties, the general sequence of activities required to deliver the projects, and the reduction of disputes (Ghadamsi, 2016). Well-defined contract responsibilities minimize misunderstandings and disagreements between parties, leading to smoother project execution and reduced delays (Demachkieh, et al., 2020). When each party’s roles and responsibilities are clearly articulated, it fosters accountability and streamlines decision-making processes, contributing to timely project completion and cost control (Singh and Sakamoto, 2001). A logical sequence of activities, established early in the project life cycle, ensures efficient resource allocation and minimizes disruptions, further contributing to cost savings and timely completion (Common Factors for Construction Disputes, 2019). Moreover, clear contractual provisions and established communication protocols can significantly reduce the likelihood of disputes, preventing costly litigation and project delays (Yusuwan and Adnan, 2013). Ultimately, a well-structured contract, coupled with clearly defined roles and a planned sequence of activities, enhances the quality of the finished product by minimizing errors and re-work. Collaboration and dispute mitigation also contribute to improved quality and can lead to overall project success.

Although time, cost, and quality have been the predominant variables in evaluating building construction execution, they have been criticized for focusing on economic matters and missing social or environmental aspects (Atkinson, 1999). To address these shortcomings, Ngacho and Das (2013) in their study identified time, cost, quality, and site disputes as significant in assessing the execution of construction projects. These factors were used to measure dependent variables in this study.

In conclusion, while there is an array of factors that need to be properly managed to enable the successful execution of construction projects, it is essential to properly evaluate the project delivery methods to be used, as research has shown that the use of appropriate project delivery methods leads to overall project success. Additionally, this study adopted the use of time, cost, site disputes, and quality as measurement metrics to evaluate the execution of construction projects, as recommended by Ngacho and Das (2013).

Study scope and objective

Between 2012 and 2015, the Government of Kenya (GoK) funded the construction of 33 court-building projects, whereas the World Bank funded 30 projects under the Kenyan Judiciary. The deadline for completing these projects was December 2018 (Sojar, 2016). However, by January 2020, only 11 projects (10 World Bank and 1 GoK) had been completed, and all had suffered cost escalations and completion delays (Sojar, 2016). The World Bank financing was not through public–private partnership (PPP) arrangement but through a loan that the Government of Kenya was to pay back upon reaching the maturity period (Project Acquisition Document, 2012). Although there are many project delivery methods in use when implementing construction projects, this study narrowed on construction manager at risk, design–build, and design–bid–build, as these have been reported as the three principal project delivery methods currently used in the United States (Zuber, et al., 2018; Tamur and Erzaij, 2021).

Project delivery methods are significant because of their capacity to impact the planning, management, and execution of projects from start to end, maximizing resources, reducing risks, and successfully accomplishing project goals (Lahdenperä, 2015; Mosly, 2016; Islam and Trigunarsyah, 2017; Trach, Połoński and Hrytsiuk, 2019). Each method has unique characteristics and is suitable for different project types. The choice of the project delivery method significantly impacts project success, including cost, time, site disputes, quality, client satisfaction, functionality, health, safety, and user satisfaction (Ngacho and Das, 2013).

Each project differs in terms of its objectives, limitations, and goals. The choice of a suitable project delivery method guarantees conformity with these objectives and goals. When project activities, resources, and strategies are aligned with project objectives, they increase the likelihood of project success and enhance overall performance. This shows that the project delivery methods used are as varied as the projects themselves. No one project delivery method is a fit for all goals (Lahdenperä, 2015; Agustiawan, Coffey and Sutrisno, 2020). The purpose of this study was to establish the project delivery methods (PDMs) used and their influence on the execution of construction projects in the Kenyan Judiciary, while the study objectives were to examine the influence of the used PDM on the execution of construction projects in relation to time, cost, site disputes, and quality in the Kenyan Judiciary.

Literature review

A synthesis of the literature on the three principal project delivery methods of construction manager at risk (CMAR), design–build (DB), and design–bid–build (DBB) is reviewed in this paper, as these have been reported to be the three principal project delivery methods currently used in the United States (Tamur and Erzaij, 2021; Konchar and Sanvido, 2023). Their impact on time, cost, site disputes, and quality is also outlined. Based on the reviewed literature, the study’s conceptual framework is presented.

Performance of DB, DBB, and CMAR on time, cost, site disputes, and quality during delivery of construction projects

DB, DBB, and CMAR project delivery methods offer distinct advantages and disadvantages in terms of project control, cost management, risk allocation, and collaboration between stakeholders (Azari, et al., 2014; Hosseini, et al., 2016; Gordian, 2020; Schwartz, 2022).

Time and cost management

The effects of various project delivery techniques on project delivery characteristics or attributes differ. DBB is sequential in nature, and projects undertaken through it can take longer to complete than through the other methods. Before construction can begin, the design and bidding stages must be completed. Owing to the possibility of changing orders and differences between the design and construction phases, cost management in DBB is difficult (Azis, 2017; Kaur and Singh, 2018; Fahmi, Aulia and Isya, 2020; Hải, et al., 2023). DB permits the design and construction phases to overlap and is frequently more effective in managing time than DBB. This can significantly reduce a project’s total length by a large margin. DB provides a single point of accountability, which helps to simplify cost management procedures (Azis, 2017; Kaur and Singh, 2018; Zuber, et al., 2018). The CMAR allows for the early involvement of the construction manager, which can expedite the construction process. The construction manager can provide input during the design phase to optimize constructability and streamline scheduling. CMAR provides greater transparency and cost control by establishing a guaranteed maximum price (GMP). This helps manage costs and minimizes the risk of budget overruns (Zuber, et al., 2018). DB and CMAR are often cited for their efficiency in cost management because of their streamlined processes and risk management strategies. DBB may pose challenges in cost management owing to potential changes in orders and discrepancies (Zuber, et al., 2018).

Site disputes and quality control

Site disputes can negatively impact project performance and should be avoided. Every project delivery method represents different relationships, thus presenting unique challenges in terms of dispute generation and resolution (Naji, Mansour and Gunduz, 2020). Factors such as the allocation of risk, communication protocols, and the level of collaboration among the project team members all play a role in determining the frequency and severity of site disputes (McConnell and Clevenger, 2018). In a DBB approach, where the owner contracts separately with the designer and the contractor, disputes may arise due to a lack of collaboration between the design and construction teams (Hasanzadeh, et al., 2018). Strahorn, Brewer and Gajendran (2017) suggested that the contractual requirements within the design–bid–build framework tend to foster a focus on personal agendas over the collective interests of the project, which often leads to conflicts. However, in a design–build approach, where the same entity is responsible for both design and construction, there may be fewer disputes, as the team is more integrated and collaborative (Hosseini, et al., 2016; Hasanzadeh, et al., 2018). Similarly, a construction manager is involved during the design phase and holds the risk for construction performance in the construction manager at risk method, which may lead to different types of disputes, compared to other delivery methods. Understanding these implications is crucial for project stakeholders in selecting the most suitable project delivery method to minimize site disputes and ensure successful project delivery (Soni, Pandey and Agrawal, 2017; Hasanzadeh, et al., 2018; Alaloul, Hasaniyah and Tayeh, 2019; Seeboo and Proag, 2019).

Quality is a performance evaluation metric for the execution of construction projects (Ngacho and Das, 2013; Veselá and Synek, 2019). Quality control in DBB relies heavily on specifications and drawings provided by the design team (Zuber, et al., 2018). Contractors are responsible for adhering to these documents during construction. In DBB, owners bear a significant portion of the risk, including design errors and construction defects (Azis, 2017; Kaur and Singh, 2018). Contractors can mitigate risks through careful planning, adherence to standards, and quality assurance processes. DB projects often feature integrated design and construction teams that facilitate better coordination and communication. The single point of responsibility may lead to enhanced quality control measures throughout the project life cycle (Azis, 2017; Kaur and Singh, 2018; Zuber, et al., 2018). DB shifts more responsibility to the design builder, who assumes greater accountability for project outcomes (Djojopranoto and Benhart, 2017; Liu, Nederveen and Hertogh, 2017). This can incentivize risk-mitigation strategies such as proactive problem solving, value engineering, and early issue resolution. DB typically offers stronger quality control measures because of their collaborative nature and single-point responsibility (Liu, et al., 2020). CMAR allows for the early involvement of the construction manager, who can oversee quality control measures from the planning stages to project completion. This can include material testing, inspection, and adherence to the project specifications. CMAR provides opportunities for risk mitigation through proactive risk identification and management strategies. Construction managers can work closely with owners and design teams to identify potential risks and develop mitigation plans to address them. CMAR also provides opportunities for effective quality control through the involvement of early construction managers. DB and CMAR tend to offer better risk-mitigation strategies than DBB (Zuber, et al., 2018; Ammad, et al., 2020).

Theoretical framework for understanding project delivery methods and construction project success

The theoretical framework for analyzing the impact of project delivery methods on the success of construction projects is highlighted as follows.

Project delivery methods

The framework recognizes that different project delivery methods, characterized by varying contract responsibilities, the roles and responsibilities of the parties, the general sequence of activities, and dispute resolution mechanisms, significantly influence project outcomes. The selection of an appropriate project delivery method is crucial, as it not only affects the efficiency of resource utilization but also determines the project stakeholders’ level of integration and collaboration throughout the project life cycle. The choice of delivery method ultimately shapes not just the cost and schedule performance but also the quality of communication and cooperation among the project team members, which in turn impacts overall project success and stakeholder satisfaction (Ahmed and El-Sayegh, 2020; Tamur and Erzaij, 2021; Anderson and Oyetunji, 2003).

Systems theory

Construction projects are viewed as complex systems with interconnected elements. Project delivery methods are seen as integral components within this system, influencing and being influenced by other project aspects such as contract responsibilities, the roles and responsibilities of the parties, the general sequence of activities, and dispute resolution mechanisms (Mccomb and Smith, 2014). Creating a robust framework that emphasizes these attributes can significantly enhance collaboration and communication among stakeholders, ultimately leading to improved project outcomes and adherence to timelines and budgets (Waters and Ahmed, 2020). Moreover, as projects become increasingly complex and uncertain, the necessity for a flexible and adaptive project delivery system that accommodates these interdependencies becomes even more crucial, suggesting that traditional frameworks may be insufficient to meet contemporary challenges in construction projects (Azari-Najafabadi, et al., 2011; Ding, et al., 2018; Whyte and Davies, 2021).

Theory of change

This theory helps explain the causal relationships between project delivery attributes and project execution outcomes. The framework uses this theory to trace how specific project delivery methods impact time, cost, site disputes, and quality. Understanding this complex interplay enables stakeholders to better anticipate project success or failure based on the particular strategies implemented, thus allowing for adjustments that cultivate enhanced integration and collaboration among project teams in the judiciary system. This approach underscores the notion that innovative project delivery systems can significantly improve performance by promoting organizational integration and alignment of interests, ultimately leading to more effective management strategies during the execution phase of building projects in Kenya’s judiciary context (Azari, et al., 2014; Hosseini, et al., 2016; Dhillon and Vaca, 2018; Ding, et al., 2018).

Stakeholder theory

Recognizing the diverse interests of stakeholders, the framework emphasizes the importance of understanding and managing their influence on project success. Project delivery methods are seen as tools that can be leveraged to align stakeholder interests and improve project outcomes (Al-adawiyah and Utomo, 2020). Stakeholders can significantly impact project objectives and their overall effectiveness, underscoring the criticality of proactive stakeholder management during the execution of building projects in the Kenyan Judiciary. Moreover, the identification and engagement of key stakeholders during the early stages of project execution are crucial, as they determine not only the fulfillment of project objectives but also the project’s overall quality, timeliness, and success, making it essential to establish strategies that effectively address their needs and expectations (Eskerod and Vaagaasar, 2014; Nahyan, et al., 2019; Al-adawiyah and Utomo, 2020; Elias, 2023).

This theoretical framework posits that the successful execution of construction projects, measured in terms of time, cost, site disputes, and quality, is heavily influenced by the chosen project delivery method. Moreover, understanding the specific attributes of various project delivery methods such as design–bid–build, construction management, and design–build is crucial for stakeholders in the judiciary sector to make informed decisions that align with their project needs and objectives, particularly in navigating challenges (Ahmed and El-Sayegh, 2020; Tamur and Erzaij, 2021). The framework offers valuable insights for project managers to select appropriate project delivery methods and manage stakeholder expectations effectively (Raouf and Al‐Ghamdi, 2019; Kahvandi, et al., 2020).

The conceptual framework

This conceptual framework was guided by systems theory, theory of change, and stakeholder theory. It postulated that there is a correlation between project delivery methods represented by contract responsibilities, the roles and responsibilities of the parties, the general sequence of activities, and the reduction of disputes as the independent variables and the execution of construction projects represented by time, cost, site disputes, and quality as the dependent variable. Table 1 shows the conceptual framework developed from the literature review used in the study.

Source: Okello (2024).

Hypothesis and research question

H0: Project delivery methods have no significant influence on the execution of court-building projects in Kenya in terms of time, cost, site disputes, and quality. The research question was how do project delivery methods influence the execution of court buildings in Kenya in terms of time, cost, site disputes, and quality?

Methodology

Research design

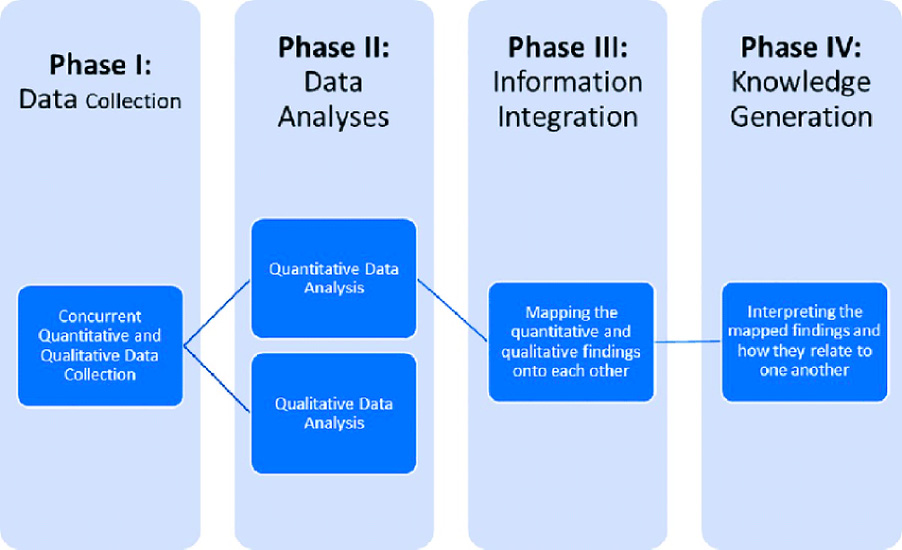

The study employed a pragmatic research design that combines quantitative and qualitative research techniques. The researcher collected and analyzed qualitative and quantitative data in the same phase. After combining the data, a comprehensive analysis was produced, and a convergent mixed-methods design was created (Sekaran and Bougie, 2013; Bryman and Bell, 2015). The triangulation of data gathered through alternate approaches to countercheck and mitigate weaknesses in the approaches used is the strength of this approach. Triangulation and validation were used in the method to enable diversity in data collection and interpretation.

Validity and reliability of the instruments

Three project management experts verified the validity of the research instruments by providing valuable feedback on how to develop the contents in accordance with the study’s objectives. The constructs were deemed suitable for measuring the study variables after they were applied to 12 projects, wherein all Cronbach’s alpha scores for the constructs used to assess project delivery methods and court-building execution scored above the acceptable level of 0.7, in accordance with the recommendation of Pallant (2007). In addition, validity was further tested using principal component analysis (PCA) based on data received from the pilot study. The constructs were confirmed valid. The primary study used 51 projects.

Ethical consideration

The researcher was given permission to collect the study data by the chief registrar of the Judiciary. The researcher agreed not to divulge any information that may affect the courts or people in the study. Confidentiality and anonymity were provided to the research participants. The participants were also informed about the purpose of the research as well as treated with dignity and respect.

Data collection

Data collection and analysis were guided by the diagram shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Visual representation of the mixed-methods study design used in this research work as adopted from Rad, et al. (2021).

The study collected data from 63 ongoing court buildings in Kenya at Molo, Nyando, Vihiga, Oyugis, Nyamira, Muhoroni, Nakuru, Olkalau, Engineer, Nanyuki, Mukurweini, Kigumo, Chuka, Homabay, Maralal, Kajiado, Mombasa, Mombasa Court of Appeal, Narok, Kibera, Makindu, Kitui, Isiolo, Makueni, Kabarnet, Marsabit, Amagoro, Githongo, Machakos, Mbita, Habasweini, Hamisi, Muranga, Mandera, Garissa, Nyeri, Iten, Karatina, Makadara, Forodha House, Wajir, Kapenguria, Kwale, Maralal, Kakamega, Kangema, Makueni, Malava, Siaya, Port Victoria, Bomet, and Nyahururu. A questionnaire was the main tool used in the study to collect data. The questionnaire asked for categorical background data, which included the following: the project’s name, location, stage of completion, highest educational attainment, position within the judiciary, and length of time spent in the current role (design, construction, or completion stage). They are all noteworthy details.

Data (discrete) for the descriptive analysis came from the respondents’ ratings of the project delivery method constructs of contract responsibilities, the roles and responsibilities of the parties, the general sequence of activities, and the reduction of disputes. On a 5-point Likert scale, which was used by Shek and Wu (2014), the respondents rated the execution of court-building constructs as well as timely completion, completion within budget, site disputes, and quality of work. The 10-point visual analog scale (produced continuous data), with 1 denoting the lowest score and 10 the highest, was used to generate data for inferential analysis (correlation, linear, and multiple regression analysis) using the same constructs. Inferential data were tested and passed tests on linearity, normality, multicollinearity, homoscedasticity, and autocorrelation.

By calculating the average of all the courts’ responses to the study constructs, the project delivery methods and court-building execution were determined. Additionally, an interview guide was used to collect data from Judiciary management, which consists of National Environment Management Authority (NEMA) specialists and Judiciary Infrastructure Committee members. The instrument was designed to meet the objectives of the study in accordance with the advice of Patton and Appelbaum (2003), who suggested that protocols and instruments for data collection should be established in order to avoid being overwhelmed by an abundance of data. The study also employed data from the following sources to confirm the impact of project team integration on Kenyan court-building procedures: the Public Procurement Act, the Judicial Performance Improvement Project (JPIP) framework, project appraisal reports, site meeting minutes, Treasury directions, Judicial Service Commission (JSC) directives, the World Bank financial cooperation agreement, and sessional papers.

Data analysis

The study utilized quantitative and qualitative data analysis techniques.

Quantitative data analysis

The researcher employed the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, 29) to streamline the process of data analysis. The mode, mean, and standard deviation of summary statistics were used to analyze the quantitative data obtained from the Likert scale ratings.

Regression was applied to visual analog data to analyze and determine how significantly the project delivery methods influenced the dependent variable using the coefficients of determination and hypothesis tests.

The simple regression model used in the analysis of hypotheses was of the following form:

Y = β0 + βX + ε,

where Y is the project execution about time, cost, site disputes, and quality; X is the independent variable (project delivery method, Ho); β0 is the constant; β is the regression coefficient; and ε is the error term.

Determination coefficient, R2, was used to evaluate the explanatory power of the independent variable (Project delivery methods—X on the project execution (about time, cost, site disputes, and quality) in the Kenyan Judiciary. Similarly, the degree to which the regression model fits the data was assessed using the F-test (analysis of variance). In contrast, the t-statistic was used to assess the significance of the slope coefficient.

Findings

The descriptive statistics of project delivery methods in relation to trust, respect, and collective understanding are shown in Table 2.

Source: Okello (2024).

Table 2 indicates that the respondents were undecided that the project delivery system used was suitable for enhancing contract responsibility in the implementation of building construction projects in the Kenyan Judiciary (Mode = 2.5, M = 3.21, standard deviation (SD) = 0.90). Further, the respondents agreed that the delivery system used was suitable for enhancing the roles and responsibilities of the parties in the implementation of construction projects in the Kenyan Judiciary (Mode = 5, M = 4.36, SD = 0.90).

In addition, the respondents were undecided that the delivery system used was suitable for enhancing the general sequence of activities in the implementation of building construction projects in the Kenyan Judiciary (Mode = 2.75, M = 3.28, SD = 0.64).

Table 2 indicates that the respondents agreed that the delivery system used was suitable for enhancing the reduction of disputes in the implementation of building construction projects in the Kenyan Judiciary (Mode = 3.75, M = 3.92, SD = 0.79).

In summary, in Table 2, the respondents agreed that the project delivery system used was appropriate for the implementation of building construction projects in the Kenyan Judiciary (Mode = 3.75, M = 3.69, SD = 0.50). The respondents ranked the roles and responsibilities of the parties as first (Mode = 5, M = 4.36, SD = 0.90), the reduction of disputes as second (Mode = 3.75, M = 3.92, SD = 0.79), the general sequence of activities required to deliver the projects as third (Mode = 2.75, M = 3.28, SD = 0.64), and contract responsibility as fourth (Mode = 2.5, M = 3.21, SD = 0.90).

The interview guide was used to capture information from project infrastructure committee members and NEMA specialist interviewees. The respondents stated that the PDS adopted by the Kenyan Judiciary was DBB, as opposed to DB and CMAR, which are the other options in the industry. In addition, the respondents commented on the suitability of the system used. They also stated whether the Kenyan Judiciary achieved its aim through the project delivery system used in terms of contract responsibility, the roles and responsibilities of the parties, the general sequence of activities required to deliver the project, and the reduction of disputes. The results of the interview are as follows.

The key respondents stated that the delivery system used by the Judiciary was the DBB system. They were, however, undecided that the project delivery system used was suitable for enhancing contract responsibility, as captured by the following comment:

“The system used may be suitable, as opposed to having one person do the designs and construction; this could create governance problems; the designer can overdesign and employ shortcuts during construction. The system enables accountability, reduces the cost, and makes supervision easy in addition to incorporating all stakeholders, including the court users and staff.” (Respondent R4)

The respondents also stated that the DBB project delivery system needed to be improved to manage time, cost, site disputes, and quality. There was also agreement among the key informants that the delivery system used was suitable for enhancing the roles and responsibilities of the parties in the implementation of construction projects in the Kenyan Judiciary. This theme was captured by a statement from respondent R3:

“There was coordination within the team; everyone played their part albeit with delays and sometimes slow dissemination of information; during the ESIA, it took longer to get the required details and information from the architects and engineers.”

The key informants were undecided that the delivery system used was suitable for enhancing the general sequence of activities in the implementation of building construction projects in the Kenyan Judiciary. The reason for this could be that the sequencing of activities was conducted by different parties, and it was, therefore, difficult to follow up on what each of them was doing in this area. Other key informants agreed with this position, as was captured by another statement on this theme by Respondents R4 and R15:

“The sequence of activities was somewhat not planned as there were projects where the ESIA was being undertaken while construction was nearly complete and therefore the ESIA process could not inform the design.” (Respondent R4)

“The general sequence was well laid out, especially for new projects; thus enabling the management of expectations for each of the parties though the delays were too many to the point that the project at times would seem disorganized for refurbishments of courts; sequence of activities are not clear.” (Respondent R15)

Key informants further agreed that the project delivery system used was suitable for reducing disputes during the implementation of building construction projects in the Kenyan Judiciary. This theme was captured by the following statements from the key informants:

“The process of procuring was transparent; therefore, no disputes registered, there’s however need to develop and implement a Grievance Redress Mechanism.” (Respondent R5)

“The DBB project delivery system is ideal for the Judiciary since the entity covers the whole country. Each region has its unique characteristics, and it would be more efficacious if different entities undertook the design and construction for quick delivery.” (Respondent R17)

A review of project files, contracts, minutes of site meetings, inspection, and acceptance minutes indicated that the project delivery system used in the procurement of construction projects in the Kenyan Judiciary was DBB. This supports the findings from descriptive statistics and corroborated information from key informants. In this type of delivery system, the contractors are not expected to be on board during the design stage (Kormaz, et al., 2010), as confirmed by the respondents who indicated that the delivery system used did not allow the contractor to be involved during the project design.

Inferential statistical results

The purpose of this paper was to use Pearson’s correlation analysis and linear regression analysis to show how project delivery methods affect court-building execution (time, cost, site disputes, and quality) in Kenya. To investigate the possibility of a relationship between project delivery methods and project execution (time, cost, site disputes, and quality), Pearson’s correlation analysis was used. The results of the correlation analysis, with a sample size of 51 respondents, are displayed in Table 3.

Source: Okello (2024).

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

Table 3 indicates that the results of Pearson’s correlation analysis showed that there was no significant association between PDM and time, as the p-value (0.378) was greater than the significance level (0.05). However, there was a significant correlation between the PDM and cost, site disputes, and quality, as the p-values were less than the level of significance. The ‘1’ in the correlation table indicates a perfect positive correlation between the variables themselves

Project delivery methods and execution of construction projects in relation to cost (model 1), site disputes (model 2), and quality (model 3) in the Kenyan Judiciary

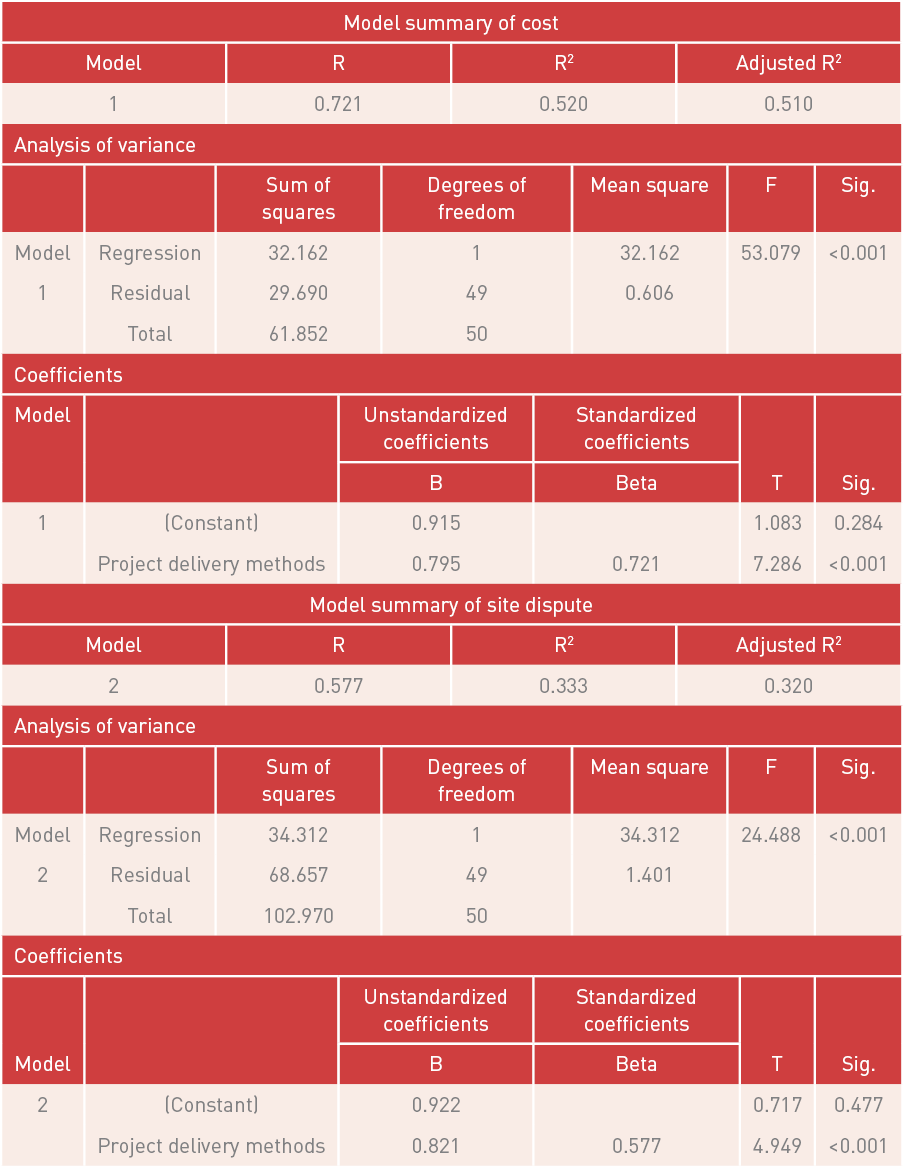

To test the first null hypothesis (H0) that PDM has no significant influence on the execution of construction projects (ECP) (cost) in the Kenyan Judiciary, a simple linear regression analysis was performed. Note that simple linear regression analysis was not performed between PDM and time because the results shown in Table 3 indicate that there was no significant association between PDM and time. The simple linear regression analysis results in relation to the cost are listed in Table 4.

Table 4. Project delivery methods and execution of construction projects in relation to cost, site disputes, and quality.

Note. Dependent variables: cost (model 1), site disputes (model 2), and quality (model 3). Predictor: (Constant), project delivery methods.

Source: Okello (2024).

According to Table 4, model 1, the other variables accounted for 48.0% of the variation in ECP, with costs accounting for 52.0% (moderate explanatory power) of the variance. Because the p-value of 0.001 was less than the significance level (α-value) of 0.05, the model was considered significant overall. Consequently, H0 was rejected, and it was concluded that the PDM had a major impact on cost during the execution of construction projects in the Kenyan Judiciary. Furthermore, Table 4, model 1, also shows that the constant was not significant because its p-value (0.284) was greater than the α-value (0.05), whereas the PDM was significant because its p-value (0.001) was less than the α-value (0.05). The predictive equation was Cost = 0.795 PDM, which indicates that, on average, cost will increase by 0.795 units if the PDM is increased by 1 unit.

Table 4, model 2, demonstrates that site disputes accounted for 33.3% (low explanatory power) of the variance in ECP; hence, other variables accounted for 66.7% of the variation. Because the p-value of 0.001 was less than the significance level (α-value) of 0.05, the model was also judged to be significant. As a result, the H0 was rejected, and it was determined that PDM had a major impact on site disputes during the execution of construction projects in the Kenyan Judiciary. Furthermore, Table 4, model 2, also shows that the constant was not significant because its p-value (0.477) was higher than the α-value (0.05), whereas the PDM was significant because its p-value (0.001) was smaller than the α-value (0.05). Thus, the predictive equation was Site disputes = 0.821 PDM, indicating that, on average, if PDM is raised by 1 unit, site disputes will increase by 0.821 units.

Table 4, model 3, indicates that quality accounted for 44.2% (moderate explanatory power) of the variance in ECP, while other variables accounted for 55.8% of the variation. The p-value of 0.001 was less than the level of significance (α-value) of 0.05, indicating that the model was significant overall. Consequently, H0 was rejected, and it was concluded that PDM had a major impact on the execution of construction projects for the Kenyan Judiciary in relation to quality. Furthermore, it can be observed in Table 4, model 3, that whereas the constant was not significant because its p-value (0.081) exceeded the α-value (0.05), the PDM was significant because its p-value (0.001) was smaller than the α-value (0.05). It follows that Quality = 0.740 PDM is the prediction equation, which indicates that, on average, if the PDM is increased by 1 unit, quality will increase by 0.740 units.

Discussion

The global construction industry is often characterized by its complex PDMs that shape not only the execution but also the cost, timeline, and quality outcomes of construction projects. In the context of the Kenyan Judiciary, the choice of PDM plays a crucial role in determining the efficiency of project execution. The Judiciary predominantly employs the DBB method, a sequential approach known for its potential to result in longer execution times compared to more integrated methods such as DB and CMAR. While the study examining the influence of project delivery methods on construction projects within the Kenyan Judiciary did not establish a direct correlation between DBB and project delays, it highlighted certain inherent challenges that could contribute to project extensions. These include delays during the bidding and procurement phases, along with a lack of stakeholder integration, as suggested by earlier research (Ahmed and El-Sayegh, 2020).

DBB, due to its traditional sequential structure, can potentially extend construction timelines. In this approach, the design and construction phases are separate, and the contractor is selected only after the design is complete. This lack of overlap between the design and construction stages can lead to inefficiencies, longer procurement cycles, and delays. The bidding process itself, which can be time-consuming, and issues related to contractor selection are also notable sources of delay (Kalsaas, et al., 2018; Molenaar, et al., 2000). However, the Kenyan Judiciary’s use of DBB does not always result in delays, and no direct correlation was found between the method and project timelines in the study. This highlights the complexity of the relationship between PDMs and project execution, suggesting that the actual impact may be influenced by factors beyond just the method itself, including project scale, scope, and the capacity of the involved stakeholders.

Alternative project delivery methods, such as DB and CMAR, have gained popularity due to their more integrated and collaborative approaches. DB, for instance, allows for the design and construction phases to overlap, which can lead to a more efficient use of time. By having a single entity responsible for both design and construction, DB reduces the risk of delays due to miscommunication or disputes between the design team and the contractor (McGraw, 2017). This integration facilitates faster decision-making and enables the project to progress more smoothly through its various phases. The result of the study also indicated a positive correlation between DBB and project cost. In contrast to DBB, where cost management can become challenging due to changes in orders or discrepancies between the design and construction phases, DB and CMAR provide more effective control over both time and cost management (Azis, 2017; Kaur and Singh, 2018; Zuber, et al., 2018; Gransberg and Gransberg, 2020).

An unexpected finding in the study was the positive correlation between DBB and reduced site disputes within the Kenyan Judiciary. This contrasts with the general view in the literature that DBB tends to foster adversarial relationships due to its separate contracts for design and construction (Rostiyanti, et al., 2019). The study suggests that in the Kenyan context, DBB may have been more effective at minimizing disputes, although this warrants further investigation. Factors such as the specific contractual arrangements, the professionalism of the project teams, and the regulatory environment may contribute to this finding. It is also possible that the Kenyan Judiciary has developed particular mechanisms to mitigate potential conflicts, leading to smoother project execution.

The performance of DBB, DB, and CMAR can also be compared in terms of quality control. In DBB, quality is heavily dependent on the specifications provided by the design team, with contractors held accountable for adhering to these standards during construction (Azis, 2017). In contrast, DB allows for better coordination between the design and construction teams, improving communication and facilitating stronger quality control throughout the project (Liu, et al., 2020). Similarly, CMAR’s early involvement of the construction manager allows for more proactive quality assurance, as the manager can monitor quality from the planning phase to completion (Zuber, et al., 2018). These integrated approaches typically result in better quality control, as compared to DBB, which may suffer from fragmented oversight and a higher risk of design errors or construction defects (Kaur and Singh, 2018).

The study acknowledges that the actual impact of PDMs on project execution within the Kenyan Judiciary may be influenced by factors beyond just the method itself, including project scale, scope, and the capacity of the involved stakeholders. The lack of a direct correlation between DBB and project delays suggests that other contextual factors may have played a role in shaping the outcomes of the projects examined (McGraw, 2017). Additionally, the study was limited to the Kenyan Judiciary, and the findings may not be directly generalizable to other sectors or regions. While the study provides valuable insights into the influence of project delivery methods on the execution of construction projects in the Kenyan Judiciary, it acknowledges the need for further investigation. The positive correlation between DBB and reduced site disputes warrants deeper exploration to understand the underlying factors contributing to this finding. Additionally, the study’s focus on the Kenyan Judiciary context limits the generalizability of the findings to other construction sectors or geographic regions.

Future research should explore the implementation of alternative PDMs, such as DB and CMAR, within the Kenyan Judiciary to better understand their potential benefits in terms of project timelines, cost control, and overall efficiency. Comparative studies of different PDMs could provide valuable insights into the factors that influence the effectiveness of each method in the Kenyan construction industry context. Additionally, expanding the scope of the research to include other sectors or regions could help identify broader trends and patterns in the relationship between PDMs and project execution. To build upon the current study, future research could expand the scope to investigate the performance of various project delivery methods across a broader range of construction projects in Kenya, beyond the Judiciary. This would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the suitability and effectiveness of different delivery methods in the Kenyan construction industry. Additionally, comparative studies of the Kenyan context and other developing or developed countries could shed light on the contextual factors that influence the performance of project delivery methods. Such cross-cultural investigations could yield valuable insights for practitioners and policymakers to make informed decisions on project delivery strategies.

Conclusion

While DBB may offer some advantages, such as cost savings, it also presents challenges related to time, cost management, and stakeholder collaboration. Alternatives like DB and CMAR, with their integrated and collaborative approaches, may offer better solutions for projects where time efficiency, cost control, and quality are top priorities. The Kenyan Judiciary’s use of DBB has provided some surprising insights, particularly into site disputes, but a more nuanced understanding of the contextual factors influencing these outcomes is needed. Selecting the appropriate PDM requires a careful evaluation of the specific needs and goals of the project to ensure the most efficient and effective delivery.

References

Agustiawan, Y., Coffey, V. and Sutrisno, R. 2020, “The Role of Project Culture in Achieving The Performance of Indonesian Toll Road Projects”. https://doi.org/10.2991/aer.k.201221.024

Ahmed, S. and El-Sayegh, S. 2020, “Critical Review of the Evolution of Project Delivery Methods in the Construction Industry.” Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, 11(1), 11-11. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings11010011

Akob, Z., Hipni, A, Z, M. and Rosly, M, R, M. 2019, “Leveraging on building information modelling (BIM) for infrastructure project: Pan Borneo Highway Sarawak Phase 1”. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/512/1/012060

Al-adawiyah, N. and Utomo, C. 2020, “A Review of Previous Researches’ Methods on Stakeholder Management at Construction Projects”. IOP Publishing, 436(1), 012014-012014. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/436/1/012014

Alaloul, S, W., Hasaniyah, W, M. and Tayeh, A, B. 2019, “A comprehensive review of disputes prevention and resolution in construction projects,” MATEC web of conferences. Available at: https://www.matecconferences.org/articles/matecconf/abs/2019/19/matecconf_concern2018_05012/mate https://doi.org/10.1051/matecconf/201927005012

Ammad, S. et al., 2020, “Evaluating Safety Attributes in Infrastructure Projects”. https://doi.org/10.1109/IEEECONF51154.2020.9319936

Anderson, S. and Oyetunji, A A. 2003, “Selection Procedure for Project Delivery and Contract Strategy”. https://doi.org/10.1061/40671(2003)83

Atkinson, R. 1999, “Project management: cost, time, and quality, two best guesses and a phenomenon, it is time to accept other success criteria”. International Journal of Project Management, 17(6): 337-342 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0263-7863(98)00069-6

Azari, R., Kim, Y., Ballard, G. and Cho, S K. 2014, “Starting From Scratch: A New Project Delivery Paradigm”. 2276-2285. https://doi.org/10.1061/9780784413517.231

Azari-Najafabadi, R., Ballard, G., Cho, S. and Kim, Y. 2011, “A Dream of Ideal Project Delivery System”. https://doi.org/10.1061/41168(399)50

Azhar, N., Kang, Y. and Ahmad, I. 2014, “Factors Influencing Integrated Project Delivery in Publicly Owned Construction Projects: An Information Modelling Perspective”. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2014.07.019

Azis, S. 2017, “Risk management analysis for construction of Kutai Kartanegara bridge-East Kalimantan-Indonesia,” AIP Conference Proceedings. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5011572

“Common Factors for Construction Disputes”. 2019, Available at: https://quantitysurveyor4u.blogspot.com/2019/10/common-factors-for-construction-dispute.html (Accessed: November 16, 2024).

Demachkieh, F. et al. 2020, “Considerations for Filing Global Construction Claims: Legal Perspective,” Journal of Legal Affairs and Dispute Resolution in Engineering and Construction. American Society of Civil Engineers. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)LA.1943-4170.0000393

Dhillon, L., and Vaca, S. 2018, “Refining Theories of Change”. Springer Science+Business Media, 14(30), 64-87. https://doi.org/10.56645/jmde.v14i30.496

Ding, J., Wang, N., and Hu, L. 2018, “Framework for Designing Project Delivery and Contract Strategy in Chinese Construction Industry Based on Value-Added Analysis”. Hindawi Publishing Corporation, 2018, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/5810357

Djojopranoto, A. W., and Benhart, B. L. 2017, “Design and Build: Perception of Project Owners and Contractors on Cost in Java, Indonesia.” Civil Engineering Dimension, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.9744/ced.19.1.7-13

Elias, A. 2023, “Stakeholder Analysis for R and D Project Management”. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1467-9310.00262

Eskerod, P., and Vaagaasar, A. L. 2014, “Stakeholder Management Strategies and Practices during a Project Course”. SAGE Publishing, 45(5), 71-85. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmj.21447

Fahmi, F., Aulia, T. and Isya, M. 2020, “Risk analysis study on building projects in Pidie District,” IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 933(1), p.012011-012011. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/933/1/012011

Ghadamsi, A., & Braimah, N. (2016). Examining the relationship between Design-Bid-Build selection criteria and project performance in Libya. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/ https://doi.org/10.6106/JCEPM.2016.6.2.016

Gordian, 2020, “Comparing 5 Delivery Methods for Construction Projects” https://www.gordian.com/resources/comparing-5-project-delivery-methods/

Gransberg, J. N. and Gransberg, D. D. 2020, “Public Project Construction Manager-at-Risk Contracts: Lessons Learned from a Comparison of Commercial and Infrastructure Projects,” Journal of Legal Affairs and Dispute Resolution in Engineering and Construction, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)LA.1943-4170.0000339

Hasanzadeh, S., Esmaeili, B., Nasrollahi, S., Gad, G. M., and Gransberg, D. D. 2018, “Impact of Owners’ Early Decisions on Project Performance and Dispute Occurrence in Public Highway Projects”. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)LA.1943-4170.0000251

Holloway, 2018, “Importance of Construction Industry in the Economy and Use of Construction Equipments”. Blog https://www.hhilifting.com/

Hosseini, A., Lædre, O., Andersen, B., Torp, O., Olsson, N. O., and Lohne, J. 2016, “Selection Criteria for Delivery Methods for Infrastructure Projects”. Elsevier BV, 226, 260-268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.06.187

Islam, S. M. and Trigunarsyah, B. 2017, “Construction Delays in Developing Countries: A Review,” Journal of Construction Engineering and Project Management, 7(1), p. 1-12. https://doi.org/10.6106/JCEPM.2017.3.30.001

Judiciary Transformation Framework, 2012, “Judiciary transformation framework”. Published by the Judiciary of Kenya.

Kahvandi, Z., Saghatforoush, E., Ravasan, A. Z., and Viana, M. L. 2020, “A Review and Classification of Integrated Project Delivery Implementation Enablers”. Penerbit Universiti Sains Malaysia, 25(2), 219-236. https://doi.org/10.21315/jcdc2020.25.2.9

Kalsaas, B.T., Hannås, G., Frislie, G., and Skaar, J. 2018, “Transformation from design-bid-build to design-build contracts in road construction” In: Proc. 26th Annual Conference of the International Group for Lean Construction (IGLC). González, V.A (ed.), Chennai, India, pp. 34-45. https://doi.org/10.24928/2018/0394

Kaur, M. and Singh, R. 2018, “Risk and Risk-Handling Strategies in Construction Projects,” International Journal of Management Studies, 5(1(4)), p. 01-01. https://doi.org/10.18843/ijms/v5i1(4)/01

Ktaish, B., and Hajdu, M. 2022, “Success Factors in Projects”. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/1218/1/012034

Lahdenperä, P. 2015, “Project delivery methods in Finnish New Building Construction— A Review of the Last Quarter Century.” Procedia Economics and Finance 21:162-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(15)00163-X

Liu, K., Zhang, X., Wang, X., Chen, Y., and Mao, X. 2020, “The application of quality control circle to improve the quality of samples.” https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000020333

Liu, Y., van Nederveen, S. and Hertogh, M. 2017, “Understanding effects of BIM on collaborative design and construction: An empirical study in China,” International Journal of Project Management, 35(4), p. 686-698. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2016.06.007

Mccomb, D., and Smith, J. Y. 2014, “System project failure: the heuristics of risk”. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/07399019108964967

McConnell, H. W. and Clevenger, M. C. 2018, “Frequently Disputed Sections within the AIA A201–2017 General Conditions”. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)LA.1943-4170.0000274

McGraw Hill construction (2017). Managing uncertainty and expectations in building design and construction. Retrieved from https://www.dbia.org/

Molenaar, R. K., Vanegas, A. J. and Martinez, H. 2000, “Appropriate Risk Allocation in Design-Build RFPs”. https://doi.org/10.1061/40475(278)117

Mosly, I. 2016, “Construction Project delivery method Selection Framework: Professional Service Firms’ Perspective.” Journal of Civil Engineering and Architecture 10 (2016) 368-378, https://doi.org/10.17265/1934-7359/2016.03.012

Nahyan, M. T. A., Sohal, A. S., Hawas, Y. E., and Fildes, B. 2019, “Communication, coordination, decision-making and knowledge-sharing: a case study in construction management”. Emerald Publishing Limited, 23(9), 1764-1781. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-08-2018-0503

Naji, K., Mansour, M. and Gunduz, M. 2020, “Methods for Modeling and Evaluating Construction Disputes: A Critical Review,” IEEE Access. Available at: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9007665/. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2976109

Ngacho, C., and Das, D. 2013, “A performance evaluation framework of public construction projects: An Empirical study of Constituency Development Fund (CDF) Projects in Western Province, Kenya”. A thesis submitted to the University of Delhi, Faculty of Management Studies. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2013.07.005

Odoko, A. B. A. 2018, “The Role the Construction Industry Plays in Economic Growth.” Journal of Environmental Science and Resources Management Vol. 10, No. 2, Pp. 92-98

Okello, J. F., Bowa, O. and Migosi, J. 2024, “Project delivery attribute, Procurement Practices and implementation of building construction projects in the Kenyan Judiciary”, PhD Thesis, University of Nairobi. Kenya.

Pheng, L. S., and Hou, L. S. 2019, “The Economy and the Construction Industry”. Construction Quality and the Economy. 2019: 21–54. Published online 2019 Jan 9., https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-5847-0_2

Project Acquisition Document. 2012, “Judiciary of Kenya World Bank financing document”.

Rad, F. A., Otaki, F., Baqain, Z., Zary, N., and Al-Halabi, M. 2021, “Rapid transition to distance learning due to COVID-19: Perceptions of postgraduate dental learners and instructors”. PLoS ONE 16(2): e0246584. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246584

Raouf, A. M. and Al‐Ghamdi, S. G. 2019, “Effectiveness of Project Delivery Systems in Executing Green Buildings”. American Society of Civil Engineers, 145(10). https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0001688

Raykar, P. and Ghadge, A. N. 2016, “Analyzing the Critical Factors Influencing the Time Overrun and Cost Overrun in Construction Project”. International Journal of Engineering Research, ISSN: 2319-6890 (online), 2347-5013 (print), Volume No. 5, Issue Special 1, pp. 21-25, 8 and 9 Jan 2016, NCICE@2016.,

Rostiyanti, S. F., Koesalamwardi, A. B., and Winata, C. 2019, “Identification of design-build project risk factors: contractor’s perspective”. MATEC Web of Conferences, 276, 02017-02017. https://doi.org/10.1051/matecconf/201927602017

Salim, S. M. and Mahjoob, R. M. A. 2020, “Achieving the Benefits and Requirements of Integrated Project Delivery Method Using BIM,” IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 901(1), p. 012033-012033. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/901/1/012033

Seeboo, A. and Proag, V. 2019, “Sources and Cause of Poor Performances on Residential Building Projects – Case Study of the Republic of Mauritius”. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/603/3/032023

Sekaran, U., & Bougie, R. (2013). Research Methods for Business (6th Ed.). John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Shek, D., & Wu, F. (2014). “Quantitative evaluation of the revised training program Project P.A.T.H.S. In Hong Kong.” International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh.2012.038

Singh, A. and Sakamoto, I. 2001, “Multiple Claims in Construction Law: Educational Case Study,” Journal of Professional Issues in Engineering Education and Practice, American Society of Civil Engineers, p. 122. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1052-3928(2001)127:3(122)

Sojar. 2016, “State of the Judiciary Annual Report, 2016/2017”. Published by the Judiciary of Kenya.

Sojar. 2019, “State of the Judiciary Annual Report, 2018/2019”. Published by the Judiciary of Kenya.

Soni, S., Pandey, K. M. and Agrawal, S. 2017, “Conflicts and Disputes in Construction Projects: An Overview,” International Journal of Engineering Research and Applications. Available at: https://www.ijera.com/papers/Vol7_issue6/Part-7/H0706074042.pdf.

Strahorn, S., Brewer, G., and Gajendran, T. 2017, “The Influence of Trust on Project Management Practice within the Construction Industry” Construction Economics and Building. AJCEB.v17i1.5220 https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v17i1.5220

Tamur, S. T. and Erzaij, K. R. 2021, “The effectiveness of project delivery systems in the optimal implementation of green buildings”. IOP Publishing, 1105(1), 012099-012099. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/1105/1/012099

Trach, R., Połoński, M., and Hrytsiuk, P. 2019, “Modelling of Efficiency Evaluation of Traditional Project Delivery Methods and Integrated Project Delivery (IPD),” IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 471, p. 112043-112043. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/471/11/112043

Veselá, L. and Synek, J. 2019, “Quality Control in Building and Construction”. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/471/2/022013

Waters, R. V., and Ahmed, S. A. 2020, “Beyond the spreadsheets: quality project management”. Performance Improvement, 59(10), 16-29. https://doi.org/10.1002/pfi.21940

Whyte, J. and Davies, A. 2021, “Reframing Systems Integration: A Process Perspective on Projects”. Project Management Journal, 52(3), 237-249. https://doi.org/10.1177/8756972821992246

Yusuwan, N.M. and Adnan, H. 2013, “Issues Associated with Extension of Time (EoT) Claim in Malaysian Construction Industry,” Procedia Technology. Elsevier BV, p. 740. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.protcy.2013.12.082

Zuber, S.Z.S., Nawi, M.N.M., Nifa, A.A.F., and Bahaudin, A.F. 2018, “An Overview of Project Delivery Methods in Construction Industry”. International Journal of Supply Chain Management. Vol. 7, No. 6, December 2018. IJSCM, ISSN: 2050-7399 (Online), 2051-3771 (Print, 2018)