Construction Economics and Building

Vol. 25, No. 2

July 2025

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Pre-Contract Measures to Avoid Potential Disputes in the New Zealand Construction Industry

Pramod Malaka Silva1,*, Niluka Domingo2, Noushad Ali Naseem Ameer Ali3

1 School of Built Environment, Massey University, New Zealand, pramodmalaka94@gmail.com

2 School of Built Environment, Massey University, New Zealand, n.d.domingo@massey.ac.nz

3 School of Built Environment, Massey University, New Zealand, n.a.n.ameerali@massey.ac.nz

Corresponding author: Pramod Malaka Silva, School of Built Environment, Massey University, New Zealand, pramodmalaka94@gmail.com

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v25i2.9259

Article History: Received 28/07/2024; Revised 09/04/2025; Accepted 21/04/2025; Published 08/08/2025

Citation: Silva, P. M., Domingo, N., Ali, N. A. N. A. 2025. Pre-Contract Measures to Avoid Potential Disputes in the New Zealand Construction Industry. Construction Economics and Building, 25:2, 235–252. https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v25i2.9259

Abstract

The New Zealand (NZ) construction industry suffers from negative implications of disputes in construction projects, similar to other countries. Hence, the importance of avoiding disputes has become a vital topic to discuss and research. Avoiding disputes in construction projects has always been challenging, with limited research on this topic. Notably, no studies have explored potential pre-contract measures to prevent disputes in the New Zealand construction industry. To address this research gap, this study was designed, and it is limited only to construction projects in NZ that followed the traditional procurement path. Fourteen professionals in the NZ construction industry with significant experience and knowledge in construction disputes were interviewed, and the gathered data were analyzed qualitatively. A total of 84 pre-contract measures to avoid potential construction-related disputes were identified under five themes (themes of causes of disputes). The most responsible party/parties and most applicable pre-contract stage/s for each dispute avoidance step are also presented. The clarity of communication, risk management, proper documentation and standardization, review and continuous improvements, and collaboration are the main underlying characteristics of the identified avoidance measures. Among the identified dispute avoidance measures, respondents emphasized clear scope documentation and expectation management meetings as the most significant. The proposed measures could help principals, tenderers, and consultants in New Zealand to minimize potential disputes. Additionally, this study opens avenues for further research into dispute avoidance strategies for other procurement methods (other than the traditional procurement path) and practical approaches to clearly document the construction scope.

Keywords

Construction Disputes; Dispute Avoidance; Pre-Contract Stage; New Zealand Construction

Introduction

Gerber (2013) emphasized the importance of preventive measures to reduce disputes, noting that the initial cost of setting up a dispute avoidance procedure can be recovered many times over through savings from reduced disputes and early resolution. Previous research has also focused on the assessment and prediction of potential disputes. Various statistical and mathematical methods have been employed by researchers to develop dispute prediction models. For example, Diekmann and Girard (1995) utilized logistic regression to forecast the likelihood of disputes, highlighting the importance of competent human resources in dispute avoidance and the impact of project complexity on disputes. Similarly, Molenaar, Washington and Diekmann (2000) used structural equation modeling (SEM) to underscore management ability and project complexity as key factors in dispute prediction. Ayhan, Dikmen and Birgonul (2021) applied machine learning (ML) techniques, drawing data from a comprehensive literature review and expert interviews, to predict the occurrence of disputes.

De Alwis, Abeynayake and Francis (2016) emphasized the necessity of forecasting disputes during the “briefing stage” of a construction project in Sri Lanka, where the client’s requirements and objectives are established. They identified factors such as risk allocation, contractor selection, quality of documentation, time management, and procurement methods as critical in avoiding potential disputes.

Zhu and Cheung (2020) proposed a framework illustrating how incentivization can reduce construction disputes by reinforcing relational governance (narrowing gaps in risks, responsibilities, and power), increasing investment in relationships, and improving perceptions of fairness. A study in Saudi Arabia, based on nearly 93 questionnaires, found that fair contract risk allocation, drafting dispute clauses, team building, provision of a neutral arbitrator, and binding arbitration are effective contract administration methods for dispute avoidance and resolution (Jannadia et al., 2000).

Tabish and Jha (2023) used principal component analysis (with orthogonal rotation) to identify three primary factors for consideration during the post-contract stage: (a) comprehension and monitoring of scope, (b) support from higher management, and (c) the expertise of the contractor’s design consultant. Additionally, a Malaysian study suggested that discussions and negotiations between top management with decision-making and financial authority (without third-party involvement) from both contracting parties could be a more effective way of avoiding and resolving disputes.

In Singapore, Aibinu (2009) identified a high level of conflict regarding time claims in the construction industry, particularly when there was minimal pre-contract negotiation and agreement on the rules for quantifying and assessing anticipated delays. The authors highlighted the necessity of negotiating and agreeing during the pre-contract stage on record requirements for claims, methods for maintaining records, and the format of construction schedules. They also emphasized the importance of establishing methods for analyzing delay claims and a formula for calculating prolongation costs.

In the New Zealand (NZ) context, there are several studies about the causes of disputes in the construction industry and dispute resolution mechanisms, but very few studies have focused on dispute avoidance. Finnie (2021) proposed a two-stage early contractor involvement framework in the NZ context. It addresses potential complications, such as determining the variation entitlements due to drawing changes and legal implications of a contractor’s involvement in the design development. Broadly, Yiu, Lu and Ang (2021) recommended that the entire New Zealand construction industry adopt a professional and accountable approach. They advised defining project scopes as early as possible with minimal changes afterward and investigating the other party’s history before entering a construction contract to minimize potential disputes. Ramachandra and Rotimi (2011) emphasized the importance of incorporating proper payment provisions in New Zealand construction contracts. They recommended several measures to minimize payment-related conflicts, including prompt settlement of financial claims to maintain cash flow, early securing of financial guarantees, and mandatory prequalification of funding parties’ financial status.

Many previous studies have proposed measures to resolve construction-related disputes after a dispute has taken place. Kumaraswamy (2002) pointed out the importance of “dispute avoidance” and “dispute minimization” over “dispute resolution”. Globally, as explained here, there were few studies that have recommended methods to predict disputes using statistical mechanisms. Furthermore, there are some suggestions and strategies to minimize and resolve disputes that were found in a few international studies; however, those studies were applicable to the post-contract stage. In addition to the (1) framework proposed by Finnie (2021) on a two-stage early contractor involvement and (2) recommendations proposed by Ramachandra and Rotimi (2011) about the payment provisions in NZ construction contracts, there were no other studies that focused on dispute avoidance in the NZ context. Even these mentioned studies have not focused on the projects that followed the traditional procurement path and have not focused on the possibilities of avoiding potential/future disputes during the pre-contract stage. Therefore, this study attempted to investigate dispute avoidance steps that can be performed during the pre-contract stage, aiming to avoid potential disputes.

Methodology

An initial review of the existing literature in NZ and the international context has highlighted the need to conduct a proper study on possible strategies or steps that can be done in the pre-contract stage to avoid potential disputes in NZ’s construction industry. Fourteen industry experts who had at least 15 years of experience in construction contract management and/or construction disputes were selected for a series of semi-structured interviews. The selected interviewees’ professions, experiences, and identification codes are stated in Table 1.

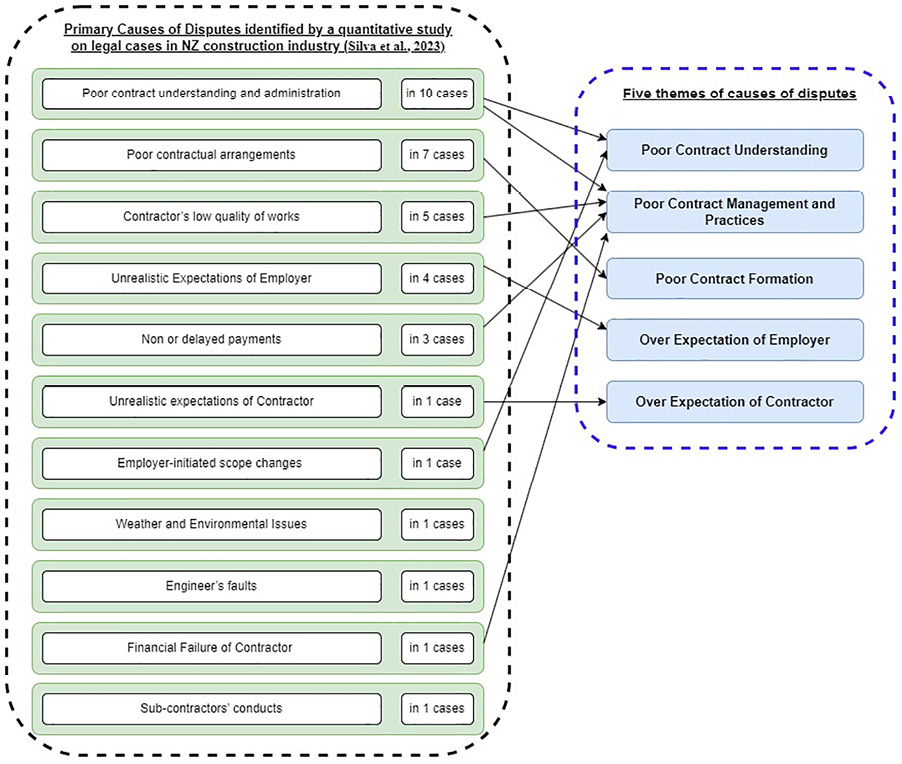

As an initial part of this study, a detailed quantitative analysis of construction-related legal cases was carried out, and 11 primary causes of disputes were identified (Silva et al., 2023). Considering the frequency of those primary causes and commonalities of the identified 11 primary causes, five themes were discerned: poor contract understanding, poor contract practices, poor contract formation, over-expectations of the contractor and over-expectations of the principal. Figure 1 shows how the identified primary causes of disputes in a previous step of this study (Silva, Domingo and Ameer Ali, 2023) have formed the five themes.

Figure 1. Formation of five themes of causes of disputes (Source: Adopted from Silva et al., 2023).

The Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) plan of work has broken down a construction project into eight stages, and it outlines core tasks, stage outcomes, and information exchanges required at each stage (RIBA, 2023). This study considered the four stages of the RIBA plan of work and adjusted the four stages as below in order to obtain and analyze responses more methodically.

Under the mentioned five themes, expert interviewees were questioned regarding the (1) concerns/issues that come under the themes (detailed causes of disputes under a theme) and (2) steps/strategies applicable to the pre-contract stages (under the four adjusted pre-contract stages in Table 2) to avoid potential disputes. This paper only discusses the findings related to the dispute avoidance steps/strategies.

| RIBA stage | Adjusted stage for this study | Description of the adjusted stage |

|---|---|---|

| Preparation and Briefing | Preparation and Briefing (PB) | Prepare project brief including project outcomes and sustainability outcomes, quality aspirations, and spatial requirements. |

| Concept Design | Concept design and spatial coordination (CDSC) | Architectural concept, which is aligned with the project brief, is approved by the client. Architectural and engineering information is spatially coordinated. |

| Spatial Coordination | ||

| Technical Design stage | Technical Design—A (TDA) Until the tender submission (tender preparation and pricing) | All the design information required to construct the project is almost complete. The client prepares the tender document and tenderers price and bid. |

| Technical Design—B (TDB) Until the contract signing (tender evaluation, award and signing contract) | Client selects a suitable tenderer. The potential contractor and client work together until the contract is signed. |

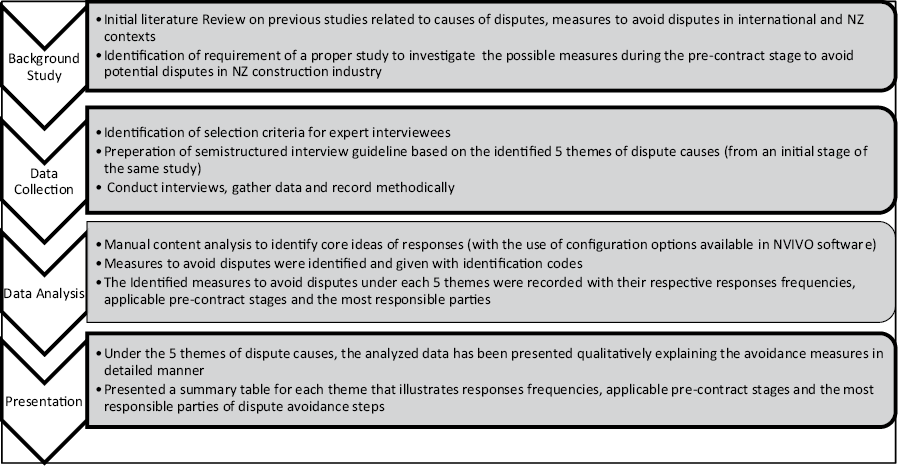

With the permission from the interviewees, interview sessions were recorded, and the files were stored methodically using the NVIVO software. Then, the audio/video recordings and their written transcripts were carefully reviewed to identify core ideas with regard to dispute avoidance steps. The identified dispute avoidance steps were given with a unique identification number as well. Furthermore, the most suitable/responsible party and applicable pre-contract stage (among the four stages in Table 2) to perform a particular avoidance step were identified from the transcripts and recordings accordingly. As an indication of the significance of any avoidance step, the number of respondents who pointed out a particular dispute avoidance step has also been recorded. The content of the gathered data has been critically analyzed manually, with some configuration options available in the NVIVO software. Under the five themes, the analyzed information has been presented, providing important insights into the dispute avoidance steps, applicable pre-contract stages, and the most responsible parties to perform those steps. Figure 2 illustrates the overall research process of this study.

Figure 2. Research process (Source: Authors’ own creation).

Findings

Poor contract understanding

The clarity of the contract documentation and the level of understanding are co-related, as per several respondents. A respondent highlighted the importance of detailed and accurate design information and the necessity of considering what constitutes a complete set of contract documents. Table 3 summarizes the collected pre-contract measures along with their applicable pre-contract stages and responsible parties under this theme. Respondent L emphasized the importance of using clear and easily understandable language with fewer legal terms. However, respondent N expressed a different perspective, stating, “…In my view, we need a well-structured contract document with precise language, especially regarding contract conditions… ..while some advocate for plain English, I am not a great fan of it, certain contractual matters cannot be fully conveyed in plain English, so I believe a combination of contract-specific language and plain language works best…”. A clear indication of measurement methods for construction activities or stating the standard method of measurements could avoid many quantity-related disputes, particularly in service-related activities (respondents K and N). A few other respondents highlighted the importance of understanding the construction programme, including how activities are linked, the scale of activities, and key activity timings. They also emphasized that being aware of the completion requirements is essential for enhancing overall understanding.

* PB, preparation and briefing; CDSC, concept design and spatial coordination; TDA, technical design—A (until the tender submission); and TDB, technical design—B (until the contract signing)

Being clear about the allocation of risks during the pre-contract stage was highlighted by respondents H and G. Respondent H highlighted the importance of the client being honest and open when transferring the risks to the contractor. In other words, it is paramount for the client to clearly draft the contractual provisions that will transfer the risks to the contractor. Respondents H and M added that understanding and clarifying the roles and responsibilities and having a better understanding of them may avoid potential confusion. Furthermore, respondent H said, “an innovative schedule that identifies what the responsibilities of each party would be helpful”.

Utilizing the previous experience for the current project and sharing knowledge in good faith with other parties are important to avoid potential disputes, as indicated by respondents E and L. Using the experience gained from the previous projects will enhance the understanding of the contract and best practicing methods; also, sharing the knowledge, such as educating the client about the construction process and practicalities during a pre-contract stage, will provide an opportunity for the contractor/tenderer to understand the client’s expectations. If a party’s internal knowledge regarding the contract administration is inadequate, it can even seek an external legal service. Respondent G stated, “2-hour workshop with a lawyer, just to talk about the nuances of clauses rather than just assuming the other person’s opinion would be worthwhile”. Innovatively, parties can even use diagrams to understand and explain contractual matters and responsibility hierarchies.

Poor contract management and practices

Setting up a contractual environment during the early stage to work collaboratively in the post-contract stage has been recorded from several responses. The responses varied across agreeing on reasonable and sufficient time for pricing variations, offering incentives for working collaboratively, and negotiating more workable contract administration procedures for both parties (refer to Table 4 for all the pre-contract dispute avoidance measures under this theme). Unless an agreed rate or a similar rate is available in the contract, a contractor needs to rely on external quotations. Therefore, interviewee K opined to discuss during the pre-contract stage to allow sufficient time to properly price variations. Similarly, interviewee N also emphasized that it is possible to adopt a different, more workable administrative methodology without undermining the risk profiles or without disturbing the project’s objectives. Furthermore, respondent N commented, “maybe you have a very poor, poorly structured contract, but if you have an intent or mindset to work collaboratively, you can deliver the project in a dispute-free environment”.

* PB, preparation and briefing; CDSC, concept design and spatial coordination; TDA, technical design—A (until the tender submission); and TDB, technical design—B (until the contract signing)

Three respondents said that proper record-keeping is essential to avoid disputes. It is common in construction companies that employees shift to other positions or different companies, leaving significant loopholes in the knowledge and records of the project. Hence, it is paramount to record important information well, particularly to smoothly transfer and record the assumptions, correspondences, and the like from the pre-contract team to the post-contract team (respondent N). While an interviewee with significant main-contractor experience highlighted the hardship of establishing the entitlement of a claim without proper recording, another interviewee pointed out some complications of not keeping suppliers’ warranties and producer statements well. To avoid those kinds of complications, which potentially lead to disputes, setting out report requirements in the contract, understanding the reporting requirements, and organizing measures to gather information for those reports were suggested.

For both the client and tenderer, it is important to bring the lessons learnt from past projects and seek experienced practitioners’ knowledge and expertise to avoid potential malpractices and mismanagement (respondents D and L). Furthermore, the respondents emphasized the importance of having capable individuals who can understand and effectively use a well-crafted contract, and they stated that even with a high-quality contract, the absence of people who can comprehend and apply its terms could lead to failure. A senior quantity surveyor from a reputed company in NZ indicated the importance of carrying out a background check to identify the financial potential of the client and the importance of identifying the experiences of the tenderers regarding past projects.

Variations and claims and their surrounding administrative mechanisms are prone to disputes during the construction stage; hence, three respondents provided recommendations to establish during the pre-contract stage. “We should incorporate robust change control procedures into the contract to establish a protocol for managing changes and identifying the owner of those changes”, respondent L added. The importance of bearing in mind from the early stages of the projects to notify the other party about upcoming cost and time implications has also been emphasized. Moreover, to facilitate the practice, it has been recommended that suitable information technologies be used to establish robust risk management procedures and to keep significant design portions as separate contract/s.

Poor contract formation

Several respondents opined that when forming their contract, the client and contractor/tenderer must go through the tender documents thoroughly to identify errors, communicate them to the other party, and manage them well. Specifically, when a tenderer notices a major omission, respondent K advised explicitly listing both the priced items and those that were not (the missing items) to prevent potential pricing misunderstandings while remaining competitive. From a tenderer’s perspective, the respondent further emphasized the importance of conducting a general review of the schedule of quantities, even in a cost-reimbursement arrangement. This is because significant differences in actual quantities during the post-contract stage can lead to substantial variations in unit costs, potentially causing conflicts. The importance of agreeing to a list of comprehensive rates has been highlighted by respondent N, saying that, “client should let tenderers to price a comprehensive set of daywork rates which are detailed enough to apply in the post-contract stage alongside the tender price”. Moreover, the involvement of experienced persons for pricing and the inclusion of a comprehensive set of pricing preambles were also suggested by two interviewees. Table 5 summarizes the pre-contract measures to properly form the contract.

* PB, preparation and briefing; CDSC. concept design and spatial coordination; TDA, technical design—A (until the tender submission); and TDB, technical design—B (until the contract signing)

The contract documents are complex and consist of many sub-documents; their clarity and tidiness are paramount (respondents E and M). Particularly, before compiling the entire contract document, all the correspondences made in various modes must be well-organized and perhaps require summarizations. Regarding the special conditions of the contract, respondent B opined, “there’s no need to add a whole layer of extra/particular conditions of contract unless there’s a specific need to include them”. From a tenderer’s perspective, it is essential to thoroughly review the tender, clearly understand what is being priced, and, most importantly, seek clarification from the client, obtain responses, and properly document them.

A senior quantity surveyor with significant experience in NZ and overseas stated that the designs of most of the construction projects in NZ are not developed to a greater extent at the time of signing the contract; hence, it causes a considerable margin of error regarding their associated lump sum prices and the like. Therefore, he suggested not relying on concept designs or very preliminary designs for pricing jobs, as this could potentially lead to scope creep, cost overruns, numerous extension-of-time claims, and disputes since the design has not yet been fully developed. Respondent J suggested paying the consultants’ fee on a percentage basis from the project’s value rather than paying on an hourly basis to ensure that the consultants produce a complete design with the expected level of detail. Five interviewees pointed out the importance of clearly documenting the scope as a primary action to avoid potential disputes. The client and its consultants are required to compile the scope with an adequate level of detail in an understandable way for tenderers. Respondent E added, “A client wants to ensure that their contractor is not surprised halfway through the job when they realise, they need to paint the cable containment in addition to installing it”. Particularly in a lump sum contract, which is more common in NZ, it is essential to clearly mention the assumptions and scope inclusions and exclusions to avoid potential disputes surrounding variation entitlements (interviewees E and J).

“Collaborative contract clauses are usually quite good as well where you work together as opposed to sitting on opposite sides of the table”, respondent G added. Furthermore, he explained that the possibilities of including clauses to incentivize parties who work collaboratively in the post-contract stage would encourage parties to be open and honest. A client can assist in good faith in providing access to the information (such as ground investigation reports) and organizing site visits to assist the preferred tenderer in obtaining the necessary information and assessing the risk effectively (respondents D and N).

Over-expectations of contractor

If the client is willing, the preferred tenderer can be involved in collaborative design reviews so that it (1) can share its specialized knowledge with the design team and (2) can understand the level of detail that would be available to the contractor during the post-contract stage (respondent H). Relevant pre-contract measures to avoid the contractor’s over-expectations are summarized in Table 6.

* PB, preparation and briefing; CDSC, concept design and spatial coordination; TDA, technical design—A (until the tender submission); and TDB, technical design—B (until the contract signing)

Respondent A, with significant main contractor experience, highlighted that certain instructions and drawing issuances could not necessarily be treated as variations with cost or time implications, as they are just further details that would have been envisaged since the pre-contract stage. Therefore, he suggested that the preferred tenderer consider all foreseeable costs as reflected in the tender documents and price them accordingly without getting involved in unnecessary disputes about the price scope. Three respondents stated that the list of items requiring pricing and the quantities provided in the tender documents should not be considered as the full scope of the project. Therefore, the tenderer must independently verify the listed items and quantities rather than relying entirely on the client-prepared schedules. Additionally, the tenderer should ensure that all foreseeable costs are accounted for in the rates or prices, as applicable.

Two respondents from the main contractor side emphasized that tenderers should understand and accept the resources and potential of their company and should not price tenders with unachievable productivity levels. In other words, tenderers should not be overly confident about their strengths or sign a contract with an impractical completion date (with impractical resource allocations). Moreover, even though the overall project follows the traditional procurement path, where the client primarily holds design responsibility, it is important for the tenderer to identify any minor design responsibilities outlined in the tender document. This allows the tenderer to be aware of the client’s expectations and assess whether they can fulfil those responsibilities (respondent M). Three respondents emphasized the importance of organizing a pre-contract meeting to discuss the expectations of the client, contractors, and other stakeholders regarding quality, budget, and timeline expectations while building a positive working relationship and trust. Respondent E from the contractor side commented, “I dread to think of what it would be like if we signed a contract with our client without having those expectation management meetings where we explain stuff”.

Over-expectations of principal

Defining and clearly communicating the quality and performance expectations of the principal before signing the contract is essential to avoid potential quality-related disputes; also, those quality expectations should be realistic, as mentioned by a respondent. Respondent H added that the principals can explain their desired procedure and information expectation from the contractor regarding the submission of extension of time claims and variations to avoid unnecessary confusion surrounding variation entitlements and extension of time claims. Moreover, some assumptions or expectations may be helpful to share with the other party in the first place to avoid potential confusion; for instance, respondent L suggested that principals can disclose any specific software that they expect to use during the post-contract stage (refer to Table 7 for all the pre-contract dispute avoidance measures under this theme).

* PB, preparation and briefing; CDSC, concept design and spatial coordination; TDA, technical design—A (until the tender submission); and TDB, technical design—B (until the contract signing)

While some respondents viewed the early involvement of preferred tenderers in pre-contract designs positively, respondents J and N highlighted negative consequences, such as ambiguities in design responsibilities and unrealistic expectations from the principal that the tenderer would bear certain risk profiles associated with the design stages. Moreover, another respondent highlighted the importance of minimizing unnecessary shared design responsibilities with the preferred tenderers. However, he said it is also essential to agree on transferring the right portions of design responsibilities to the preferred tenderer, particularly in instances where the potential contractor has more competencies than the client (or client’s consultants) or the potential contractor would be in a more controllable position to come up with a more buildable design. For instance, respondent N added, “in a construction project near coastal area, it is better to pass the design responsibility of earth retaining structures to the contractor as it is in a better position to develop designs considering the highly uncertain coastal soil conditions”. Moreover, tenderers need to review the tender document carefully and identify any minor design responsibility expected from the tenderer; if so, the tenderer needs to discuss and understand the boundary of design responsibility (respondents N and J).

Discussion

Not being able to understand the specifications in the tender document and the construction contract was identified in one-fourth of the studied cases in Norway, which caused many disputes (Omar et al., 2019). According to a Turkish study by Cakmak and Cakmak (2013), the vagueness of contract documents and the varying interpretations of these documents were ranked 8th and 12th, respectively, out of 28 attributes based on their relative importance. A New Zealand study based on construction-related court cases found that a significant number of court cases were caused by misunderstandings of the parties, and this caused disputes around payment issues, termination, suspension, and testing and inspection (Silva et al., 2023). Even though the poor contract understanding is highlighted in many international studies, the possibilities of enhancing the parties’ understanding have not been investigated. This study emphasized that the level of understanding is co-related to the clarity of the contract documents and to the level of information that is available at the time of signing the contract. Many experts emphasized the importance of understanding risk profiles and clearly defining the roles and responsibilities of all parties—something that can be effectively achieved during “technical design stage—A”, when the principal prepares the tender documents and tenderers develop their pricing.

A previous study in Hong Kong by Kumaraswamy (2002) identified “insufficient contract administration” as a proximate cause of dispute. Instances where the contract is managed very poorly, such as delays in the construction site handover process, delayed payments, stoppage of work by the principal, and poor quality of construction, were identified by an Indian study by Parikh, Joshi and Patel (2019). In order to address these issues surrounding poor contract management and practices, Yiu et al. (2021) recommended that the entire NZ construction industry should behave in a professional and accountable way to minimize potential disputes. Even though the management and practice of the construction contract are more relevant to the post-contract stage, there are many steps/strategies that can be done even during the pre-contract stage to make their post-contract stage have fewer disputes. Experts recommended establishing a collaborative contractual environment from the early stages. The key elements of this approach include agreeing on reasonable timeframes for pricing variations, providing incentives for collaboration, setting up effective variation and change control procedures, and negotiating contract administration processes that are practical and workable. Furthermore, setting out proper risk management procedures, discussions/agreements on the reporting requirements, and the levels of required information in reports could also avoid potential disputes.

When construction contracts were formed poorly in NZ, disputes related to variation entitlement, design responsibilities, and payment issues were the cause, and poor contract formation was attributable to seven out of 35 studied court cases in NZ (Silva et al., 2023). Ambiguous language, a characteristic of a poorly formed contract, is positioned at the lowest level of the interpretative structural model hierarchy, as it serves as a root cause for many other attributes that lead to disputes (Viswanathan et al., 2020). Similarly, in this study, a significant portion of respondents opined on the importance of documenting the scope clearly with fewer ambiguities to avoid potential disputes. Moreover, several other studies have also emphasized the incompleteness of the contract, vagueness, and unclear information of the conditions of the contract as causes of disputes (Cheung and Pang, 2013; Barman and Charoenngam, 2017). Even though there have been several studies discussing how the construction contracts are poorly formed and their implications, very few have recommended measures to form a contract properly. Ramachandra and Rotimi (2011) recommended a few measures to minimize payment-related conflicts that are applicable to the pre-contract stage in NZ, namely, securing financial guarantees early in contracts and including pre-qualification criteria to assess the financial status of the parties. Similarly, Yiu et al. (2021) also stressed that investigating the other parties’ background, including their financial stability, could be worthwhile to avoid potential disputes in the NZ context. This study also emphasized the importance of investigating the other party’s background before forming the contract. This study revealed the importance of having a comprehensive and more practically meaningful set of rates along with necessary assumptions for pricing inclusions. Tenderers should be experienced enough to price the job properly with all the foreseeable costs, with realistic productivity levels. Also, the tenderer, being the reviewer of the tender document, needs to verify the scope by reviewing the documents properly and by raising questions to the principal for clarification.

Both contractors’ and clients’ unrealistic expectations are major contributors to disputes in construction projects. Kumaraswamy (2002) identified contractors’ unrealistic information expectations as a key root cause of disputes in Hong Kong construction projects. However, Viswanathan et al. (2020) identified “unrealistic principal expectations” as a significant underlying cause of disputes in a six-level hierarchy of factors. Moreover, Tanriverdi et al. (2021) highlighted those unrealistic expectations of the principal as one of the five main concepts causing disputes, with extensive linkages to other causes of disputes. Particularly in the NZ context, both unrealistic expectations of the principal and contractor were identified as primary causes of five legal cases (out of 35 reviewed cases), which caused predominantly quality issues and contract terminations (Silva et al., 2023). This study attempted to investigate possibilities during the pre-contract stage to ensure that parties’ expectations do not extend beyond the ideal boundaries. To avoid disputes over the scope and pricing, tenderers should be realistic about their capabilities and include all foreseeable costs in their tenders. Principals need to clearly communicate quality, performance, and procedural expectations before signing contracts, ensuring that these are realistic. The early involvement of preferred tenderers in design reviews could be helpful, but it must be managed well to avoid ambiguities in design responsibilities and unrealistic risk expectations.

Conclusion and further research

The main aim of this study was to investigate possible steps during the pre-contract stage to avoid potential construction-related disputes in the NZ context. In order to achieve that aim, industry experts with more than 15 years of experience in construction contracts were selected to undergo semi-structured interviews. The initial part of this study identified 11 primary causes of disputes based on actual legal cases in NZ; however, considering commonalities of those primary causes, this study adopted five derived themes of causes of disputes. To gather, analyze, and present the information methodically, four pre-contract stages were discerned from the RIBA plan of work. Under each theme, recommended steps to avoid potential disputes were identified and further categorized under applicable parties and the relevant pre-contract stage.

Most of the steps that could be done to enhance the overall understanding are related to the stage of “technical design stage—B” where the tendering process takes place. The allocation of risks, responsibilities, construction schedule, and construction processes are the areas that parties require to enhance their knowledge. Clarity and the level of detail of the tender/contract documents were highlighted as impactful factors for all areas where an increased awareness is required to avoid potential disputes. Knowledge and experience (i.e., from past project experiences and employees’ competencies) play an important role with regard to effective contract practices. The information expectations and their timing constraints need to be discussed and well-established between the parties before signing the contract to manage the contract easily during the post-contract stage. Documenting the scope clearly was highlighted by a majority of the experts and indicated its positive impacts on other dispute avoidance steps as well. Furthermore, other key recommendations for forming a well-structured contract included better management of tender errors, more developed design work during the pre-contract stage, and clearer pricing scopes. These recommendations apply across all four pre-contract stages. To avoid unrealistic expectations, it is advised that both the principal and the contractor hold expectation management meetings, openly communicate concerns, and avoid placing excessive reliance on tender documents prepared by others.

The identified steps to avoid potential disputes are related to the pre-contract stage and can be considered as early preventive measures to overcome post-contract disputes. The dispute avoidance steps were identified under five themes and categorized under the most suitable pre-contract stage and the most responsible party. Industry practitioners from the client, client’s representatives, or tenderers can perform these avoidance steps throughout the pre-contract stage as avoidance strategies for potential disputes. The presented tables for each theme map the avoidance steps with their applicable pre-contract stage and applicable party, along with the number of respondents who indicated a particular avoidance step, to provide an idea of the significance of a particular step.

As this study is limited to NZ construction projects that follow the traditional procurement path, further research could be done to investigate the suitability of the suggested avoidance steps on other procurement paths as well. This study identified clear scope documentation as the most significant dispute avoidance step, considering its frequency of responses; therefore, a more in-depth study on how to document the scope clearly would be worthwhile. Furthermore, a user-friendly framework can also be developed that links pre-contract dispute avoidance steps and potential causes/concerns of disputes (in the post-contract stage).

References

Aibinu, A. A. 2009. Avoiding and mitigating delay and disruption claims conflict: Role of precontract negotiation. Journal of Legal Affairs and Dispute Resolution in Engineering and Construction, 1, 47-58. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1943-4162(2009)1:1(47)

Ayhan, M., Dikmen, I. & Birgonul, M. T. 2021. Predicting the Occurrence of Construction Disputes Using Machine Learning Techniques. Journal of Construction Engineering & Management, 147, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0002027

Barman, A. & Charoenngam, C. 2017. Decisional uncertainties in construction projects as a cause of disputes and their formal legal interpretation by the courts: Review of legal cases in the United Kingdom. Journal of Legal Affairs and Dispute Resolution in Engineering and Construction, 9, 04517011. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)LA.1943-4170.0000222

Cakmak, P. I. & Cakmak, E. An analysis of causes of disputes in the construction industry using analytical hierarchy process (AHP). 2013 / 01 / 01 / 2013. 93-101. https://doi.org/10.1061/9780784412909.010

Cheung, S. O. & Pang, K. H. Y. 2013. Anatomy of Construction Disputes. Journal of Construction Engineering & Management, 139, 15-23. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0000532

De Alwis, I., Abeynayake, M. & Francis, M. 2016. Dispute avoidance model for Sri Lankan construction industry. Available: http://dl.lib.mrt.ac.lk/handle/123/11960

Diekmann, J. E. & Girard, M. J. 1995. Are contract disputes predictable? Journal of construction engineering and management, 121, 355-363. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9364(1995)121:4(355)

Finnie, D. 2021. A contractual framework for two-stage early-contractor involvement (2S-ECI) in New Zealand commercial construction projects. Thesis, Massey University.

Gerber, P. 2013. Dispute Avoidance Procedures (‘DAPs’)-The Changing Face of Construction Dispute Management. Gerber, Paula ‘Dispute Avoidance Procedures (“DAPs”)–The Changing Face of Construction Dispute Management’(2001), 1, 122-129.

Jannadia, M. O., Assaf, S., Bubshait, A. & Naji, A. 2000. Contractual methods for dispute avoidance and resolution (DAR). International Journal of Project Management, 18, 41-49. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0263-7863(98)00070-2

Kumaraswamy, M. 2002. Construction dispute minimisation. The Organization and Management of Construction. Routledge.

Molenaar, K., Washington, S. & Diekmann, J. 2000. Structural equation model of construction contract dispute potential. Journal of construction engineering and management, 126, 268-277. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9364(2000)126:4(268)

Omar, K. S., Ola, L. & Amund, B. 2019. Why conflicts occur in roads and tunnels projects in Norway. Journal of Civil Engineering and Management, 25. https://doi.org/10.3846/jcem.2019.8566

Parikh, D., Joshi, G. & Patel, D. 2019. Development of prediction models for claim cause analyses in highway projects. Journal of Legal Affairs and Dispute Resolution in Engineering and Construction, 11, 04519018. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)LA.1943-4170.0000303

Ramachandra, T. & Rotimi, J. O. 2011. The Nature of Payment Problems in the New Zealand Construction Industry. Australasian Journal of Construction Economics and Building, 11, 22-33. https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v11i2.2171

Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA). 2023. RIBA Plan of Work [Online]. Available: https://www.architecture.com/knowledge-and-resources/resources-landing-page/riba-plan-of-work [Accessed].

Silva, P., Domingo, N. & Ameer Ali, N. 2023. Quantitative analysis of construction-related legal cases in New Zealand. https://doi.org/10.31705/WCS.2023.72

Tabish, S. Z. S. & Jha, K. N. 2023. Dispute avoidance in public construction projects. Journal of Legal Affairs and Dispute Resolution in Engineering and Construction, 15, 04522033. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)LA.1943-4170.0000577

Tanriverdi, C., Atasoy, G., Dikmen, I. & Birgonul, M. T. 2021. Causal mapping to explore emergence of construction disputes. Journal of Civil Engineering and Management, 27, 288-302. https://doi.org/10.3846/jcem.2021.14900

Viswanathan, S., Panwar, A., Kar, S., Lavingiya, R. & Jha, K. N. 2020. Causal modeling of disputes in construction projects. Journal of Legal Affairs and Dispute Resolution in Engineering and Construction, 12, 04520035. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)LA.1943-4170.0000432

Yiu, T. W., Lu, Z. & Ang, K. P. 2021. A Study of Construction Disputes in the New Zealand Context. EASEC16. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-8079-6_190

Zhu, L. & Cheung, S. O. 2020. Power of incentivization in construction dispute avoidance. Journal of Legal Affairs and Dispute Resolution in Engineering and Construction, 12, 03720001. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)LA.1943-4170.0000368