Construction Economics and Building

Vol. 25, No. 2

July 2025

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Enhanced Construction Project Duration Estimation Using Artificial Neural Networks: Initial Design and Planning Stages

Heba Al-Attar1, Ghaleb Sweis2, Bashar Tarawneh3, Waleed Abu-Khader4,*, Leen Haddad5, Rateb Sweis6

1 The University of Jordan, Department of Civil Engineering, Amman, Amman, JO, attarheba97@gmail.com

2 The University of Jordan, Department of Civil Engineering, Amman, Amman, JO, gsweis@ju.edu.jo

3 The University of Jordan, Department of Civil Engineering, Amman, Amman, JO, btarawneh@ju.edu.jo

4 Merrimack College, Civil Engineering Department, North Andover, MA, USA, abukhaderw@merrimack.edu

5 The University of Arizona, Department of Systems & Industrial Engineering, Tucson, AZ, USA, leenhaddad@email.arizona.edu

6 The University of Jordan, Business Management Department, Amman, Amman, JO, r.sweis@ju.edu.jo

Corresponding author: Waleed Abu-Khader, Merrimack College, Civil Engineering Department, North Andover, MA, USA, abukhaderw@merrimack.edu

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v25i2.9253

Article History: Received 23/07/2024; Revised 20/01/2025; Accepted 20/04/2025; Published 08/08/2025

Citation: Al-Attar, H., Sweis, G., Tarawneh, B., Abu-Khader, W., Haddad, L., Sweis, R. 2025. Enhanced Construction Project Duration Estimation Using Artificial Neural Networks: Initial Design and Planning Stages. Construction Economics and Building, 25:2, 168–191. https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v25i2.9253

Abstract

Maintaining efficiency and quality control during the early phases of construction projects depends on accurate duration estimation. However, because there is not enough data available in the initial stages of project planning, traditional methodologies suffer. To address these challenges, this study presents an innovative approach using artificial neural networks (ANNs) through Python. This method offers reliable predictions for early-stage duration estimation. ANN models were created and validated with 53 design parameters using data from 100 different construction projects in Jordan. Furthermore, the study refined the models to 43 parameters using a questionnaire-driven approach. The average duration estimation accuracy of the ANN models was 90% during the initial stage and 95% during the planning stage, demonstrating their great accuracy. Its uniqueness comes in its application of ANN to early-stage building, an area that has not been extensively studied in the literature to date, and in its demonstration that reliable predictions may be generated in the absence of abundant data. This study demonstrates ANN’s effectiveness in enhancing early-stage construction planning by providing stakeholders with a more accurate duration estimation tool than traditional methods. The findings contribute significantly to improving decision-making and project planning in the early phases.

Keywords

Duration; Artificial Neural Networks; Design; Planning; Jordan

Introduction

Time, cost, and quality are critical factors in determining construction project success. Duration estimation remains challenging for contractors and researchers, with project cost often correlating positively with duration (Velumani, et al., 2021).

Accurately estimating duration and cost during the planning stages remains a challenge. Traditional techniques, such as the critical path method, often fail to manage the complexity of modern projects, leading to frequent underestimations. The current techniques of estimating durations represent a risk to the contractor, as there is a high possibility that the owner’s estimate of the project’s duration will be inaccurate, making the contractor susceptible to liquidated damages. Unexpected delays may lead to litigation and reduced construction quality. Conversely, overestimating durations can cause financial losses for clients (Galli, 2020).

Despite these challenges, research on advanced data-driven methods like artificial neural network (ANN) for early-stage duration predictions is limited. This study addresses this gap by demonstrating ANN’s potential for providing reliable estimates with minimal data. By addressing risks of underestimation and overestimation, ANN provides stakeholders with more reliable predictions.

Sanni-Anibire, et al. (2021) claimed that the complexity of structures is increasing in the 21st century. According to experts, one of the most pervasive issues in the construction sector is the significant variance between the estimated and actual duration of construction projects (Sanni-Anibire, et al., 2020). According to Mensah, et al. (2016), a reliable schedule executed from the initial stages reduces project delays and, consequently, cost overruns. The duration of construction projects is regarded as one of the most crucial factors for the success of a project. Late completion raises costs and results in lost potential revenue for clients.

This research addresses these challenges by developing and validating ANN models to estimate project duration using actual data from various construction projects. Recent research has demonstrated that ANNs often surpass traditional regression models in predicting project durations in construction (Balali, et al., 2020; Titirla and Aretoulis, 2020; Fan, et al., 2021; Ujong, et al., 2022; AlTalhoni, et al., 2025). ANNs are preferred for their capability to handle complex, non-linear relationships and provide quick, precise predictions (Helvaci, 2008; Weckman, et al., 2010; Mensah, et al., 2016; Nani, et al., 2017; Ghritlahre and Prasad, 2018). This study aims to enhance initial schedule estimates in construction projects, particularly in scenarios with incomplete information, thereby aiding stakeholders in achieving greater accuracy in project planning and improving duration prediction accuracy.

The ANN technique has been preferred over other methods of artificial intelligence (AI) because of its ability to manage complex and non-linear functions and its higher accuracy (Weckman, et al., 2010; Kulkarni, et al., 2017).

The idea of developing ANN models for early-stage prediction is repeated several times. It can be stated once and referenced later instead of repeating it in similar forms. Furthermore, it assists stakeholders in obtaining the highest possible accuracy of project scheduling, especially when insufficient information is available about the project during these stages.

The main objectives of this research were to provide a quantifiable tool to identify and evaluate the perceived influence of the most important factors affecting the estimation of the project schedule in the initial stages (planning and the initial design stages), as well as the factors specified by literature and experts’ opinion, and at the same time determine what factors have the greatest influence on the accuracy of construction duration estimation. Moreover, the ANN models with the most effective input variables were used and developed to achieve high accuracy in early-stage duration estimation. After that, an ANN analysis of the predictability of an adequate duration for various buildings in Jordan was performed by implementing, training, and testing the models. The performance of ANN models in predicting project duration was evaluated, providing insights for project managers and researchers into optimizing scheduling practices for new construction projects.

This research focuses on construction projects and includes duration estimations in the planning and initial design stages. ANNs have proven their effectiveness where the accuracy was high during both initial stages when data are limited or unavailable, despite utilizing a high number of factors as well as a high number of different projects during each stage. The data collected were from construction projects during 2014 and 2021 in Jordan. The study inherently accounted for COVID-19 impacts through its dataset, as ANNs adjust to disruptions, including pandemic-related delays, therefore reflected in the training data. They can also be retrained for future disruptions, ensuring flexibility. Relevant literature, such as the study of Ujong, et al. (2022), supports the use of ANNs in predicting project durations under varying conditions. The adopted parameters are limited to the design factors related to project characteristics and leave out variables related to the estimation process, such as the team’s estimation experience and skills in the field, variables affecting labor productivity, and the availability of storage and equipment.

Literature review

According to Ujong, et al. (2022), the need for a precise estimation of construction cost and duration from the outset is evident. This is due to environmental and logistical factors, non-linear dependencies, and general patterns in construction projects.

Mubarak (2019) defined scheduling as the determination of the timing and sequence of operations in a project and their assembly to provide a total completion time. Scheduling and estimating are inextricably linked, and their relationship is likely to be one of the most crucial aspects of project management.

This research provides an overview of schedule estimation in construction projects, a clarification of the significant factors that affect schedule delays in construction projects, ANNs, and empirical studies related to ANNs’ adoption in estimating the schedule of construction projects.

Why is schedule estimation important?

According to Larson and Gray (2013), estimating is “balancing stakeholders’ expectations and the requirements for control while the project is being implemented”. Furthermore, they specified the following vital factors in project time estimation:

• To assist in making good decisions.

• To determine cash flow requirements.

• To ascertain precisely how effectively the project is accelerating.

• To construct time-phased budgets and specify the project baseline.

The significance of the accurate estimation of construction duration from the contractors’ viewpoint and the underestimation of construction durations entails reorganizing and reallocating resources that were not intended in the beginning. However, overestimating construction duration may be as hazardous as underestimating construction duration (Helvaci, 2008).

Key design factors affecting building duration accuracy

Numerous parameters influence construction project costs and duration; the most influential parameters were chosen after reviewing numerous studies (Juszczyk, 2015; Matel, et al., 2019; Al-Tawal., 2020; Sanni-Anibire, et al., 2020; Juan and Liou, 2021; Rauzana and Dharma, 2022; Ujong, et al., 2022). The relationship between construction project cost and duration is critical for project management and control. According to Olawale and Sun (2014), the reasons for cost increases are usually also the reasons for time extensions. Furthermore, their study was of cost and time control together in the argument that these two concepts are difficult to separate.

This study emphasizes early-stage duration predictions rather than cost estimation due to a lack of studies on duration in Jordanian construction projects from 2014 to 2021. Relevant information, including costs, was provided by responsible agents. Duration reflects project complexity and resource requirements, making it an essential variable. It serves as the target for the ANN model, enabling accurate forecasts of project timelines. This approach allows for effective predictions even when cost data are limited or unavailable.

Properties of the artificial neural network

Conventional methods rely on algorithmic instructions, while neural networks approach problems through pattern recognition and learning (Aneja, 2011). As a result, the computer’s capacity to solve a problem is constrained by the programmers’ comprehension of the issue at hand and their problem-solving skills. The inability of algorithmic approaches to resolve issues is that the programmer only has a hazy understanding of these issues (Al-Tawal, 2020).

In contrast, neural networks, composed of small processing units called neurons, function similarly to the human brain by learning rather than relying solely on programming. They adapt their approach to problem-solving based on acquired knowledge (Aneja, 2011).

Wang and Elhag (2007) affirmed that ANNs can learn and approximate various relationships, including both linear and non-linear ones. Their capability to model data with multiple inputs and outputs is a significant advantage. Current literature has highlighted that ANNs serve as effective soft computing tools, simulating the human mind’s reasoning and pattern recognition abilities (Kaur, 2016; Kulkarni, et al., 2017; Pezeshki and Mazinani, 2019). ANNs learn from the relationships between inputs and outputs in training data, enabling them to generalize results and address non-linear problems that require contextual judgment and expertise.

According to Mijwel (2018), the following characteristics distinguish neural network systems from conventional computing and artificial intelligence:

1. Fault tolerance refers to the network’s ability to make a correct decision in the case of incomplete input data because the network correlates the existing components with its memory without the need for the missing components.

2. Pattern recognition.

3. A multiple-layer neural network’s generalization and classification abilities are its most important characteristics.

4. The ability of ANN adaptability is in response to new inputs not encountered earlier. The processing elements (neurons) adjust their weights individually and then in groups, naturally in accordance with the learning scheme.

Empirical studies related to ANNs’ adoption in estimating the duration of construction projects

The application of ANNs in construction has been estimated to date back to the early 1980s, covering various construction-related challenges. A review of contemporary studies demonstrates the relevance of ANNs in enhancing estimation accuracy. Table 1 illustrates several studies that are pertinent to this research, which utilized ANNs in construction duration estimation.

| Country | Objectives | Findings | Authors |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | Compared alternative methods in the initial stages of projects to forecast the conceptual duration of construction projects. Regression analysis and ANN were used to formulate five models to estimate the duration of 17 construction projects in the United States. | 1. The results for the regression and neural network models proved that there were no significant variations in the prediction accuracy. 2. The mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) of the conceptual estimate of the construction duration in this study reached 13%–15%. | Helvaci (2008) |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | A linear regression using a “time cost” model was used to estimate the construction time, and valuable information about the 75 buildings built in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina was gathered through field research. | 1. The value of MAPE was calculated (10.35). 2. The value of MAPE was then determined by applying a multilayer perceptron neural network (MLP-NN) predictive model to the same data (2.50). 3. The MLP-NN model showed a significant increase in prediction accuracy. | Petruseva, et al. (2012) |

| Ghana | Studied a tool for estimating the duration of bridge-building projects. One hundred sets of questions were distributed and the historical records for 30 completed bridge projects. The stepwise regression approach and ANN strategy were utilized to examine and evaluate the data. | 1. Both regression and ANN models are suitable for forecasting the duration of a new bridge development project. 2. During the validation stage, the development of a regression model and an ANN model utilizing a feed-forward backpropagation algorithm resulted in MAPE values of 25% and 26%, respectively. | Nani, et al. (2017) |

| Nigeria | Investigated the cost and duration of construction projects. A database was created using six input variables. The Levenberg–Marquardt training algorithm and MSE performance criteria were used in the development of smart intelligent modeling in MATLAB to achieve an optimized network architecture. | 1. An average coefficient of determination (R2) of 0.99995, which is better than the multiple linear regression (MLR) result of 0.6986. 2. The computed results showed a good correlation between the ANN model and the actual results. 3. The value of MAE was 0.2952, which denotes a robust model. | Ujong, et al. (2022) |

Note. ANN, artificial neural network; MLP, multilayer perceptron; NN, neural network.

Research gap

Neural networks have not been used to estimate the duration of construction projects in Jordan. Furthermore, the estimation of duration is a crucial issue, especially during the initial stages of the design of a construction project and when information is limited. In Jordan, the methods of estimation are poor and traditional due to a lack of historical data and high competitiveness between the companies. It is important to develop an ANN model to estimate the duration, which is why this research is significant. ANNs are being applied during various design stages in a project’s life cycle at the regional level. For these reasons, this research focuses on applying ANNs to actual samples of building construction projects in Jordan that have been built over the past 8 years, using different parameters as inputs at each stage to evolve duration estimation models in the planning and initial design stages. Moreover, building on the challenges identified in the introduction, this research aimed to develop different ANN models for use in the initial stages of construction projects, planning, and preliminary design stages to estimate the duration required to perform a project without delays.

Research methodology

There are two approaches to data analysis: quantitative and qualitative. The objective of the quantitative approach is to gather factual data, investigate the relationships between those facts, and determine whether those facts and relationships are consistent with theories and previous research findings (El-Sawalhi and Shehatto, 2013). In order to perform statistical analysis, quantitative research requires the reduction of phenomena to numerical values. The qualitative approach identified factors influencing project duration through literature reviews. The quantitative approach, in contrast, gathered data on the main factors affecting project durations that have been built in Jordan by building a questionnaire. The identification of the factors that influence the duration of construction projects is one of the most significant steps in developing a neural network (NN) model. Through a literature review, a thorough list of factors relevant to Jordanian construction was created. Key parameters were first determined through literature reviews. After that, a first questionnaire was built based on the literature and a pilot study to identify the factors influencing the duration of construction projects in Jordan. A second questionnaire was constructed to demonstrate the importance of each factor during the initial design and planning stages.

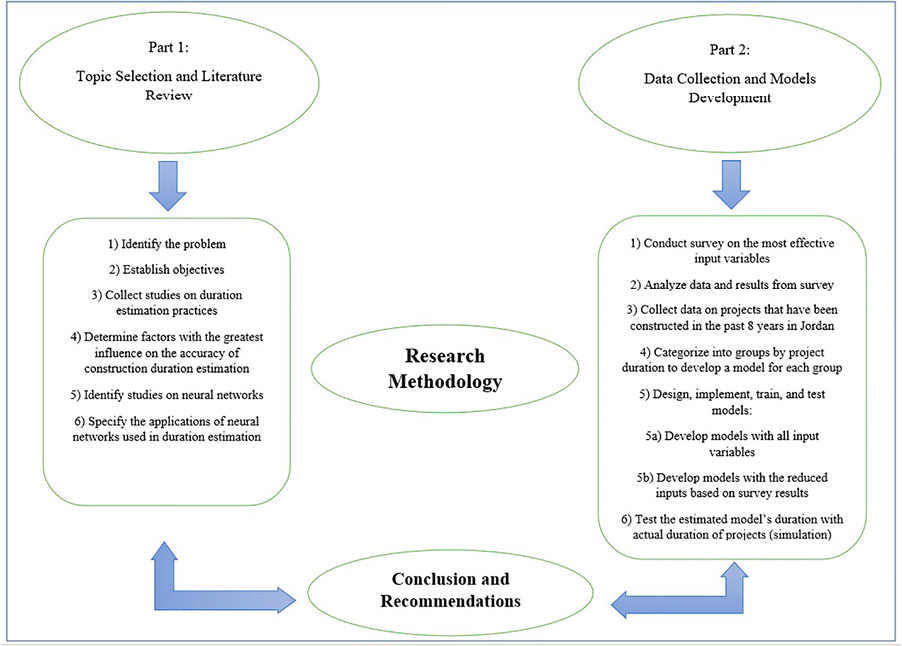

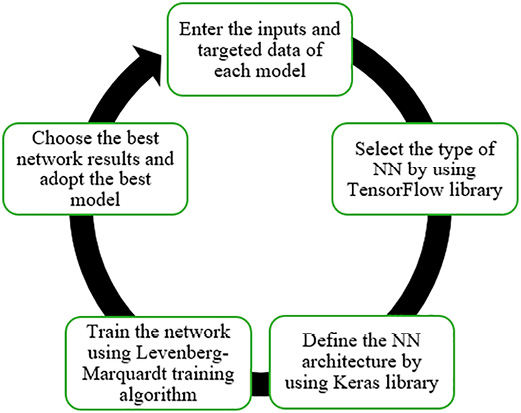

This research developed ANN models for early-stage duration estimation as an alternative to traditional methods. Figure 1 outlines the methodology.

Figure 1. Methodology steps performed (Authors’ Own)

The pilot study

A pilot study was conducted prior to sampling the questionnaire (Al-Tawal, 2020). Ten copies of the questionnaire in total were given and reviewed. The 10 successful surveys were added to the data sample since the analysis from the pilot study demonstrated the validity of the questionnaire’s internal consistency and structure, as well as the reliability of the data gathered.

Distributing the questionnaire

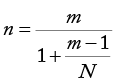

To maintain the research’s objectives, the population to which the questionnaire was distributed was defined. Because the population was small and information was acquired from each member, researchers included the complete population in census studies (Al-Tawal, 2020). The questionnaire for this research was completed in August 2022. Schedule engineers from various Jordanian construction institutions were included in the research population. Due to the small number of people who possessed the desired attribute, judgmental sampling was chosen. Using the technique of judgmental sampling, the researcher relied on the population’s expert opinion. Therefore, the sample size was carefully chosen to ensure validity and adequate reliability. Estimating a proportion for a small, finite population, the following equation was used to calculate the sample size for the population:

where N is the total population, n is the sample size necessary to estimate population sample proportion p of a small finite population, and m is the sample size necessary to estimate the proportion for a large population, which can be calculated using the following formula:

where Zα/2 is the Z-value (1.96 for a 95% confidence level), ε2 is the margin of error (4%), and p = 0.5 is the population proportion in the worst-case scenario.

Assuming 2% of engineers work or participate in schedule estimation processes, statistical analysis was done to estimate the number of planning engineers in Jordan and calculate population N. According to reports from the Jordan Engineers Association (JEA Annual Report, 2021) and Jordan Construction Contractors Association (JCCA Annual Report, 2021) and assuming an average of 50 engineers per company, first-grade and second-grade building construction companies in Amman were selected to estimate the total number of engineers working as consultants and contractors or with owners. Table 2 presents the total number of construction engineering companies and lists the approximate number of engineers in each institution, assuming that there are 50 engineers on average per company.

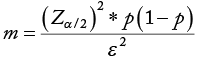

Thus, N = 56 + 163 + 70 = 289 planning engineers.

The sample size for the population can be calculated as follows:

m = (1.96)2 × (0.5 × 0.5) ÷ (0.04)2 = 600.25 and

(planning engineers from owners, consultants, and contractors).

(planning engineers from owners, consultants, and contractors).

The attainable sample was less than the requisite sample size, so the entire population was used. A total of 230 copies of the questionnaire were distributed, and 203 copies were completed and returned by the respondents for quantitative analysis.

Hypothesis testing

The hypothesis for the analysis was formulated in two parts: the null hypothesis H0 represents the expected outcome, while H1 represents the alternative hypothesis. Thus, the research hypothesis tested at n ≥ 30 is as follows:

H0 : μ ≥ μ0

H1 : μ < μ0

where n is the sample size, μ0 = 3, where 3 represents a moderate effect on duration estimation on the Likert scale (median), and μ1 refers to the factor being tested.

If μ ≥ 3, then accept H0, which means that the tested factor has a significant effect on project duration. Other outcomes reject H0, indicating that the tested factor has an insignificant effect on project duration.

Questionnaire analysis and results

The research employed a web-based questionnaire that aligned with a quantitative approach, which was divided into two sections to meet the study’s objectives. The first section gathered general information about the respondents, while the second section focused on design factors with the highest influence on the accuracy of construction duration estimation of buildings in Jordan. The questionnaire included multiple-choice questions, which were simple and quick to answer, did not require writing, and were easy to analyze. Additionally, a logical filter question was used to exclude engineers with no experience in duration estimation. The second section, which produced the majority of the results, asked respondents to rate 53 previously identified factors using a 5-point Likert scale. The Likert scale provided a structured, quantifiable way to assess the perceived influence of each factor on duration estimation. Scale number 1 indicates an exceptionally low effect on duration estimation, number 2 shows a low effect on duration estimation, number 3 indicates a moderate effect on duration, number 4 shows a high effect on duration, and number 5 illustrates a severe effect on duration.

Study population characteristics

• Participation in estimating the duration of construction projects in Jordan.

The majority of respondents (71.4%) had worked entirely in Jordan in estimating project durations; 28.6% had partially participated in estimating project durations.

• Type of organization

The majority of respondents (28.6%) were working in engineering consulting firms, followed by 24.8% working in contracting firms, 21.1% in management firms, and 13.5% in firms that focus on schedule consulting, and the remaining 12% collaborated with owners and client institutions.

• Job title/position

Twenty-five respondents described themselves as project managers (18.8%), 20 as site engineers (15%), 36 as quantity surveyors (27.1%), 21 as project engineers (15.8%), 10 as planning engineers (7.5%), two as stakeholders (1.5%), 15 as schedulers (11.3%), and four as contract administrators (3%).

• Years of experience in the construction industry

Most respondents (72.2%) had more than 7 years of construction industry experience. The targeted respondents comprised 30.1% with more than 10 years of working experience, 42.1% with 7 to 10 years of experience, 16.5% with 3 to 6 years of experience, and 11.3% with less than 2 years of experience in the construction industry.

• Number of construction projects that respondents worked on

The largest group of respondents (38.3%) worked on 20 to 30 projects, 21.1% worked on more than 30 projects, 16.5% worked on 10 to 20 projects, and 24.1% worked on fewer than 10 projects.

• Respondents’ demographic information

To gather data on projects built in Jordan over the previous 8 years, respondents were given the option of providing additional demographic information about themselves. The reliability of the questionnaire answers was influenced by the respondents’ understanding of consulting and construction work.

Factors affecting the duration of construction projects

Finding the parameters or factors that influence how long construction projects take to complete is one of the most important steps in building a neural network model. Based on literature reviews, the factors pertinent to Jordanian construction were carefully identified and chosen. Key parameters were initially determined through literature studies; subsequently, a questionnaire was developed in accordance with the building and expert opinions. Table 3 shows the influence of each factor on building duration. While specific details may not be finalized during the initial stages, expert judgment and assumptions were made based on preliminary design data, historical information, or standard practices. These factors were included as variables in the ANN model to account for their potential impact on project duration, even if some details were estimated at the initial stages.

Moreover, the ANN model’s adaptability means that these assumptions can be adjusted as more detailed information becomes available. Including such variables from the outset improves the model’s accuracy by considering their influence, helping to refine predictions as the design progresses.

Data processing

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 23 was used for quantitative analysis following the data collection process. Descriptive statistics, such as central tendency (the mean), standard deviation, and normal distribution, were used for data analysis in this research to meet the goals of the questionnaire. The independent samples t-test was used to determine whether there was a significant difference between the means of the two factors.

Dividing the dataset into five ANN models grouped projects by duration, reducing variability and enhancing performance by focusing on homogeneous data ranges. Despite fewer samples per ANN, this segmentation significantly boosts prediction reliability for each specific duration range, following established practices, such as those in Ujong, et al. (2022). To mitigate concerns about data limitations and replicability, standardized preprocessing and segmentation criteria were implemented. The dataset was divided into five duration-based groups to enhance the model accuracy by reducing variability within subsets. The division of the dataset into duration-based groups enhanced the model accuracy by reducing variability within subsets; by optimizing predictive accuracy for various project durations, the segmentation approach, combined with consistent methodologies and thorough documentation, guarantees that future researchers can replicate or tailor this framework to their datasets, irrespective of size or regional context.

Normality

Large enough sample sizes (>30 or 40) should prevent key issues arising from the violation of the normality assumption. The central limit theorem states that if the sample data tend to be normal, then the sampling distribution will also be normal. In large samples (>30 or 40), the sampling distribution tends to be normal regardless of the data’s shape (Ghasemi and Zahediasl, 2012). A normality analysis was conducted by examining the distribution’s skewness and kurtosis to verify the assumption. Skewness and kurtosis tests may be reasonably accurate in both small and large samples, according to Wulandari, et al. (2021). George and Mallery (2003) claimed that to demonstrate a normal distribution, values between −2 and +2 for skewness and kurtosis are acceptable.

Independent samples t-test

The independent samples t-test is frequently used when comparing differences between groups, and the compared groups may not even be related to each other (Kim, 2019). It is used under one circumstance: when the items in each group are fairly representative of the population, an independent samples t-test can be used to examine differences between groups according to the data gathered with the value of t = 3, and the significance level is α = 0.05.

Data analysis

There are several factors that affect the duration of construction projects during the planning and initial design stages. The first parameters adopted to build the ANN model at the initial design stage are shown in Table 3; the first model was built using all 53 factors collected from previous literature. Although not all factors, such as contract type or special construction details, are fully known at the initial stages, their inclusion accounts for potential impacts on project duration. Expert judgment and assumptions fill gaps where specific data are unavailable, enhancing the ANN model’s accuracy by considering all influences.

The reliance on expert judgment for initial estimates through a structured framework with predefined criteria like thresholds from historical data, weighted scoring systems, and guidelines for assessing duration ranges was standardized. This reduces variability in expert opinions, grounding decisions in consistent, data-driven methodologies. Pilot testing with multiple experts showed a prominent level of consensus, validating the framework’s replicability.

At the initial design stage of these projects, all specified factors influenced construction duration, as confirmed by engineers, experts, and the hypothesis test results that determined the degree of influence of each factor during each stage. The goal of this section was to reduce the 53 design factors to the most effective ones for the planning stage, resulting in 43 influential factors used in the second ANN model. These 43 factors were determined through a combination of hypothesis testing, expert judgment, and questionnaire results, which allowed the refinement of the model for more accurate duration predictions during the planning stage.

Actual data collection and validation

The process of gathering data about actual projects built in Jordan over the previous 8 years was challenging because construction companies consider such information to be proprietary to each company and find it challenging to share such information with rival firms.

The study made concerted efforts to gather sufficient data from 100 completed projects, ensuring high-quality data through the application of rigorous selection criteria to develop a robust NN model. These data were gathered using a methodology based on direct contacts with construction companies, organizations, and government agencies throughout Jordan.

Creating a realistic duration model with the best results relies on a well-prepared dataset. A data sheet was prepared, and the 53 factors collected from literature reviews required to build the dataset accurately were identified. Factors were divided into two categories: numerical and descriptive. The most critical thing to build any predictive model is data validation to find unusual or invalid cases, inaccurate variables, and inaccurate data. Basic assumptions and criteria were adopted to overcome defects in the data collected:

1. Projects must be completely finished and built (El-Sawalhi and Shehatto, 2013).

2. All inaccurate, missing, or incomplete information must be eliminated. Two projects with the same values in their duplicate data must be removed.

While this study used data from 100 construction projects, which may be considered small for developing robust ANN models, the data underwent a rigorous selection process to ensure their quality and reliability. To ensure a robust and comprehensive dataset for developing the ANN and to gather a diverse range of data from various construction projects, which are crucial for building accurate and dependable cost estimation models, the initial dataset included 110 projects. However, after filtering out incomplete, misleading, or duplicating data, 10 projects were eliminated. This rigorous selection process helped ensure the quality and reliability of the data used in the study. Additionally, the selected 100 projects represented a diverse set of project types, sizes, and complexities within the Jordanian construction sector, making the data highly representative despite the smaller sample size.

Moreover, prior studies have demonstrated that ANN models can still perform effectively with small- to medium-sized datasets when the data quality is high (Ghritlahre and Prasad 2018; Bilski, et al., 2020). Thus, while a larger dataset could further improve the model’s generalizability, this study provides a valuable foundation, laying the groundwork for future research with more extensive data.

The selection of 6-month time frames is a deliberate methodological approach designed to enhance the model accuracy by aggregating projects with comparable durations. While it may appear that advanced knowledge of project lengths is necessary, this grouping is informed by historical data and expert insights, facilitating the identification of the most appropriate model for upcoming projects. For projects with durations close to two-time bands, like 6–7 months or 13–14 months, the use of a dual-stage process was chosen. Initially, these projects were classified by comparing them to the median duration of each group using statistical thresholds from historical data. Then, these classifications were validated by comparing outputs from neighboring ANN models to see if they matched actual project durations. If there were differences, a re-evaluation of the project parameters was performed in order to ensure accurate classification without affecting the model’s predictive performance. Projects on the cusp of two duration ranges were tested against both adjacent ANN models. The outputs were cross-validated to ensure consistency, with results typically aligning within an acceptable margin of error (i.e., <±5%). This dual-model approach ensures that predictions remain robust and comparable, regardless of initial classification.

The first group of projects included those with a duration of less than 6 months and comprised 17 projects. The second group included projects with a duration of 7 to 13 months (36 projects). The third group included projects with a duration of 14 to 20 months (19 projects). The fourth group included projects with a duration of 21 to 30 months (22 projects). The fifth group included six projects with a duration of more than 30 months. This project division produced 10 models, which were then compared to build conclusions and recommendations.

In the application of these models to new projects, the selection of the most appropriate model is based on the estimated duration range of the project. This decision draws on historical data and expert insights, ensuring that the best-suited model is utilized for accurate predictions. By creating and implementing multiple models, our goal was to improve the accuracy of duration estimates for construction projects, effectively addressing the variability in project durations in a way that a single, consolidated model would not achieve.

Developing and building the model

It took a lot of trial and error to find and confirm the best model architecture. Python was chosen to create the ANN models due to its accessibility to excellent AI and machine learning (ML) libraries and frameworks, flexibility, platform independence, and wide community.

To make the selection of the appropriate ANN model consistent and replicable, a structured framework was created. This included setting predefined thresholds, using historical data benchmarks, and applying weighted scoring criteria to guide our decisions. Historical duration data and expert consensus, including project size, complexity, and contract type, guided the predefined thresholds. Key determinants for duration estimation were identified through analysis, although additional factors were initially considered to address variability and uncertainty in early-stage data. Testing the model’s simplification by removing less influential factors led to reduced prediction accuracy, particularly for atypical projects. By having clear guidelines, the differences that can arise from varying expert opinions were minimized. Also, this framework with multiple experts was tested, ensuring that they agreed on the classification outcomes, which confirmed that our approach could be replicated across different professional inputs.

Using the appropriate library for ANNs, Python divided the input data into training, validation, and testing sets. The weights attached to the neural network were modified using the training group. The testing group was used to measure the network’s capacity for generalization and to assess network performance, and training was halted when the examination group’s error rose or when generalization stopped improving. However, the test set was not used in the training process and had no bearing on it (Arafa and Alqedra, 2011; Roxas, et al., 2014; Al-saadi, et al., 2017). Once the neuronal network training was successfully finished, the performance of the model was evaluated using the validation group. As a result, the step of grouping the data into the three categories mentioned above is significant in neural network modeling (Al-saadi, et al., 2017). Table 4 shows the number of projects for each group and dataset.

When projects were initially placed in one duration bracket but later found to fit better in another due to updated design information, a re-evaluation to reassign them was necessary. However, the ANN models were built to be flexible, allowing experts to recalibrate based on new data. After reassignment, a test of the project with the new ANN model was performed to ensure accuracy. This adaptability ensures that the best-fitting model is always used, even as project details change during the design and planning phases.

This was repeated for the two stages, changing the number of input variables (53 and 43 factors) with each stage.

Table 4 demonstrates the development and validation of the ANN model across different project durations, including those less than 6 months. Using known durations for testing allowed us to assess the model’s accuracy and generalization of unseen cases. Separating data into training, testing, and validation sets ensured robust predictive performance for future projects with unknown timelines. This approach enhanced the model’s reliability in estimating durations. The fifth group, which included projects lasting over 30 months, was the smallest due to these projects’ rarity in the dataset. To manage this limitation, oversampling techniques, cross-validation, and synthetic data generation based on historical trends and expert insights were used. These measures ensure that the ANN model for this group remains robust.

After the data were prepared, the ANN was constructed by selecting appropriate libraries, defining the network architecture, and choosing suitable learning algorithms. The network architecture included decisions on the number of hidden layers, the type of transfer functions, and the learning rate. The Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm was chosen due to its effectiveness in training small- to medium-sized datasets, combining the efficiency of the Gauss–Newton method with the robustness of gradient descent (Caliskan and Sevim, 2019). This algorithm is particularly suited for regression tasks, where high precision is required. To optimize performance, the rectified linear unit (ReLU) activation function was used, which accelerates the learning process and prevents vanishing gradient issues. A learning rate of 0.01 was applied, as it balances convergence speed with stability. ReLU has become a popular choice in deep learning for its simplicity and effectiveness in producing state-of-the-art results (Ramachandran, et al., 2017).

The test data included projects covering the full range of each band, including those near the boundaries. This approach ensures that the models are robust in handling real-world cases and validate their performance for both central and borderline projects. Testing of cusp projects confirmed the models’ adaptability and predictive consistency across ranges. Projects situated near the duration range boundaries underwent testing against neighboring ANN models for cross-validation. To avoid data duplication, each project was included in only one model’s training or testing set. This dual-model validation approach ensured the accurate classification of edge projects without inflating the dataset size artificially.

Model training and results

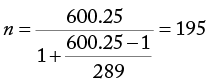

The main goal of training the neural network is to compare the validation sets of each training set to find the network that performs the best for unseen data. The main steps taken to train each of the 10 developed models are shown in Figure 2. Detailed guidelines, including Python scripts and open-source frameworks, are provided to ensure the replicability of these models.

Figure 2. Model training for each of the 10 developed models (Authors’ Own)

Detailed stages in programming were taken to choose the adequate NN. First, the Python library was used to enter the inputs and targeted data of each model. The inputs are the factor variables of each project, whereas targeted data represent the actual project duration. Then, the TensorFlow library was used, and the NN tool was selected by typing “pip install TensorFlow” in the Windows command. After that, the scikit learn library was used by typing “pip install scikit-learn” in the Windows command. Then, the data were split into training, validation, and testing sets on the “train_test_split” command code. This research allocated 80% of the data for training, 10% for validation, and 10% for testing. Additionally, a “fully connected” INPUT layer was added to the Sequential ANN by calling the Dense class to change the number of neurons when the network did not perform well after training.

Moreover, the network was trained using the Levenberg–Marquardt training algorithm because it typically consumes more memory but less time. Training automatically stopped when generalization stopped improving, as indicated by an increase in the Mean squared error (MSE) of the validation samples. After each training, the results of regression plots were shown for all datasets for each model in two stages. In each run, new weights were applied in the first epoch and then adjusted to minimize the percentage error in other epochs. After achieving the best validation performance on the input–output fit, along with the minimal error, the network was adopted, and its outputs and errors were saved. Finally, each adopted network, with its errors and outputs, represented a prediction model.

The testing stage of ANN models is where the effectiveness of the created model is evaluated. The ideal model for every stage was selected via trial and error (i.e., the model that provided the most accurate duration estimate).

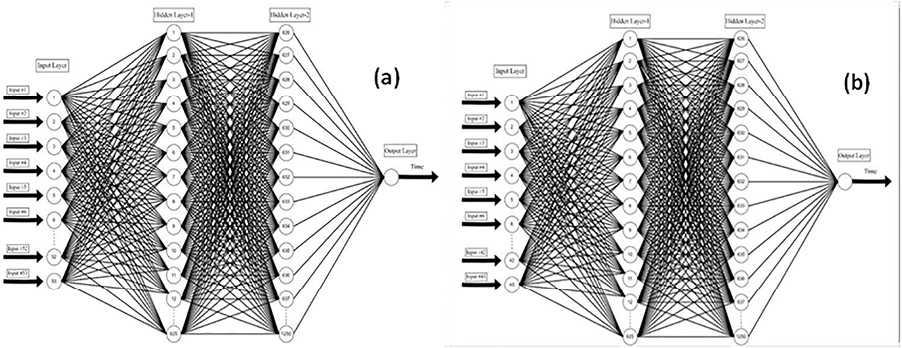

The initial design stage network includes one input layer with 53 input neurons, two hidden layers with 1,250 hidden neurons, and one output layer with one output neuron (representing total duration), as shown in Figure 3a. The planning stage network includes the same number of layers with 43 input neurons, as shown in Figure 3b.

Figure 3. ANN structure for (a) the initial stage and (b) the planning Stage, and linear regression at the initial and planning stages for all models. ANN, artificial neural network (Authors’ Own)

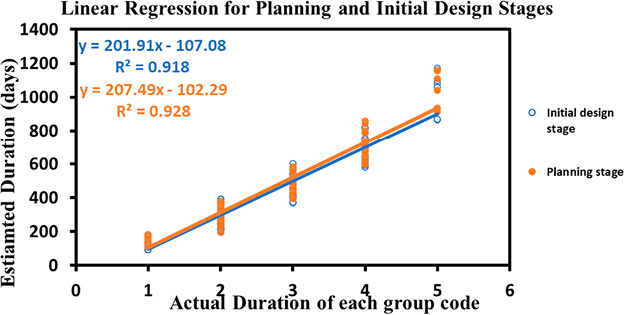

Also, Table 5 shows the summary of layers and neurons for two stages and summarizes the average errors and correlation coefficients at various stages for each group of projects in the testing stage for the adopted networks. The mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) values were 10% and 5% for the initial design and planning stages, respectively.

Regression analysis was applied to determine the relationship between the estimated and actual durations. In Figure 4, the results of linear regression for the two stages (the initial design and planning stages) only for all models are graphically depicted (the R2 values for the initial design and planning stages were 0.918 and 0.928, respectively).

Figure 4. Linear regression for planning and initial design stages (Authors’ Own)

Additional data were collected (10 real projects), and each model was evaluated separately to test the models and ascertain the efficiency of the models developed in Table 5, as the actual duration of the 10 projects exists. The factors influencing the duration of each project were introduced to find the estimated duration, compare it with the actual duration, and verify the value of MAPE. The identified factors were tested against actual project data to assess their influence on duration estimation. The ANN models incorporate these factors as inputs, ensuring that the analysis extends beyond perceived importance to include empirical validation. By comparing predictive performance with and without these factors, the study highlights their significance in improving estimation accuracy. A simulation tool, particularly the scikit-learn package, was used to enter the externally acquired data variables as inputs and to verify the network outputs once the adopted networks had been saved in Python. The actual and estimated duration results from the tested data are shown in Table 6.

The ANN models were crafted to maintain a balance between complexity and dataset size, using simplified architectures for smaller subsets. Overfitting was managed through cross-validation, regularization, and dropout layers. The number of neurons in hidden layers was fine-tuned via trial and error, with final configurations optimized based on performance metrics like MSE and MAPE.

Discussion

A comparative analysis showed that the ANN model reduced estimation errors by approximately 10% compared to conventional statistical models, and at the same time, ANN models improved estimation abilities by 95% compared to the results of current literature, highlighting ANN’s potential to minimize risk for contractors. The results imply that integrating ANN into project management practices can enhance schedule reliability and optimize resource planning.

The most significant factors that affected the duration of construction projects during the two early stages were the type of contract, project cost, built-up area, site conditions of new or existing construction, and location of the building. In the initial design stage, 53 factors were used to build the first model, while in the planning stage, 43 factors were used to construct the second model. Table 3 illustrates the most influential parameters that had the highest rate utilized in earlier studies.

In the planning stage, the model refined 53 factors to 43 based on expert feedback and hypothesis testing, enhancing accuracy and aligning with previous studies like Sanni-Anibire, et al. (2021). Reducing less relevant variables minimizes noise in the model, thereby improving predictive performance. This strategy leads to more precise duration estimates for construction projects.

Two ANN multilayer perceptron (MLP) models were created based on previously specified inputs (factors), outputs (estimated duration), and parameters in each iteration. The total number of inputs and outputs determined the number of input and output neurons, whereas two hidden layers with a maximum of 1,250 hidden neurons were present for each stage. The two models were developed in this research based on the Python programming language, and for each stage, there were five groups based on the actual duration of each project. The MAPE of the models was calculated from the average error as shown in Table 5. The values equaled approximately 10% and 5% for the initial design and planning stages, respectively. This result can be expressed in another form, accuracy performance (AP), as presented by Shehatto (2013). AP is defined as (100 − MAPE) %.

AP (at initial design stage) = 100% − 10% = 90%

AP (at planning stage) = 100% − 5% = 95%

Figure 3 shows the comparison of the actual and estimated durations. As presented, the average estimated accuracy of the initial design stage and planning stage was 10% and 5%, respectively. Moreover, the correlation coefficient (R) was extremely high for each group in two stages. Therefore, it can be concluded that the ANN model shows a particularly good agreement with actual duration and is exceptionally good at estimating the output. Furthermore, according to the R values in Table 5, there is a strong correlation between actual and estimated durations.

This research outperformed previous studies, including those by Anibire, et al. (2021), Helvaci (2008), Petruseva, et al. (2012), and Nani, et al. (2017). Anibire, et al. (2021) developed a model to estimate the duration of high-rise building construction projects in China, utilizing various machine learning algorithms, such as multi-linear regression and ANN. Out of 12 models created, the most efficient one was selected, with an ANN-based ensemble model achieving a correlation coefficient R of 0.69 and a MAPE of 18%.

Petruseva, et al. (2012) used a linear regression model to estimate construction time using a “time cost” model, analyzing data from 75 buildings in Bosnia and Herzegovina, with a resulting MAPE of 10.35%.

Nani, et al. (2017) studied duration estimation for bridge-building projects in Ghana. They collected historical data on 30 completed bridge projects and distributed 100 questionnaires. Their stepwise regression and ANN models, developed using a feed-forward backpropagation algorithm, yielded MAPE values of 25% and 26%, respectively, demonstrating the potential of ANN in improving estimation accuracy.

Conclusion

The main objective of this research was to identify and analyze key factors affecting early-stage duration estimation and to develop ANN models for accurate project duration predictions. This objective aligns with the broader goal of enhancing schedule reliability and aiding stakeholders in construction planning.

Summary

This research showed the importance of using machine learning, particularly ANN, to improve time estimation performance in the construction sector. At each stage, several models were constructed, and the model that produced the most accurate findings was chosen. For the initial design and planning stages, the adopted models’ typical accuracy was 90% and 95%, respectively.

This research highlights that the type of contract is the most significant factor influencing construction project duration. By integrating ANN models into the early planning stages, project stakeholders can improve accuracy and reduce delays. Future research can explore how these models can be adapted to other construction types or geographies to further enhance their utility.

A variety of statistical performance metrics, including MSE, MAPE, and correlation coefficient, were calculated to confirm the reliability of the proposed model in determining the duration of new projects. The results were acceptable and dependable, with the mean absolute percentage error of the models for the initial design stage and the planning stage being 10% and 5%, respectively.

According to these performance metrics, it is concluded that preliminary stage duration estimates can be just as precise as final stage estimates.

Accurately estimating durations impacts schedules, resources, and cash flows. Advances in technology have improved statistical methods for predicting project success. The significance of this research lies in formulating the relationship between the variables included in the initial and planning stages and ANN to get accurate estimates and a better understanding of the construction projects’ schedule, especially in the initial stages of project design and when information is extremely limited.

Recommendations

It is advised that all parties involved in the construction sector expand their understanding of this technique and create their models utilizing a well-built database to produce better estimates and decrease schedule overruns.

The research recommends increasing the amount of collected data for estimating the project durations and decreasing the number of factors in two stages to improve accuracy, robustness, and add them to the training data.

In future studies, researchers may examine the use of ANN for duration estimation for various fields, project types, and parameters. It is advised to be specific when choosing a dataset to use for model development.

Increasing one’s comprehension of construction duration estimation has become imperative in recent times, especially in the early phases of project design when data are limited. According to Ujong, et al. (2022), there are a number of contributing elements that make duration estimation important for communities and construction industries. These are as follows:

1. In order to help both the client and the contractor accurately estimate the resources needed and the precise duration needed for completion, the research study’s findings are crucial in order to provide timely and perfect predictions.

2. The findings of this research study provide immeasurable assistance in making decisions that will ensure the necessary quality for the project deliverables, as well as assist in developing community in the construction sector and the quality of life in the main significant area, which is time, and this will automatically reduce the cost of these projects.

3. The benefits gained from this research will help clients, construction stakeholders, and project managers effectively oversee and execute projects within the target time (schedule).

Limitations

Although the research’s goals and objectives were met, certain issues need to be resolved: sample selection, including the population of planning engineers from different institutions in the construction sector in Jordan, and the first- and second-degree building construction companies in Amman were selected to estimate the approximate targeted population.

The adopted parameters were limited to the design factors related to project characteristics, excluding variables related to the estimation process, such as the estimation team’s experience and skills in the field, as well as variables affecting labor productivity, the availability of storage and equipment, the state of the market, and changes in timing.

The limited availability of historical data on construction project durations and design parameters in Jordan is also a shortcoming.

References

Al-saadi, A. M., Kh. Zamiem, S., Al-Jumaili, L. A. A., Jameel Jubair, M., & Abdalla Al- Hashemi, H. (2017). Estimating the Optimum Duration of Road Projects Using Neural Network Model. International Journal of Engineering and Technology, 9(5), 3458–3469. https://doi.org/10.21817/ijet/2017/v9i5/170905007

Al-Tawal, D. R., Arafah, M., & Sweis, G. J. (2020). A Model Utilizing the Artificial Neural Network in Cost Estimation of Construction Projects in Jordan. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 28(9), 2466–2488. https://doi.org/10.1108/ECAM-06-2020-0402

AlTalhoni, A., Alwashah, Z., Liu, H., Abudayyeh, O., Kwigizile, V., & Kirkpatrick, K. (2025). Data-driven identification of key pricing factors in highway construction cost estimation during economic volatility. International Journal of Construction Management, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2025.2511065

Aneja, N. (2011). Neural Networks Approach vurses Algorithmic Approach : A Study Through Pattern Recognition. Advanced Computing: An International Journal, 2(6), 183–187. https://doi.org/10.5121/acij.2011.2617

Anibire, M. O. S., Zin, R. M., & Olatunji, S. O. (2021). Developing a Machine Learning Model to Predict the Construction Duration of Tall Building Projects. Journal of Construction Engineering, Management & Innovation, 4(1), 022-036. https://doi.org/10.31462/jcemi.2021.01022036

Annual Report (pp. 67-73, Rep.). (2021). Jordan, Amman: Jordan Construction Contractors Association.

Annual Report (pp. 70-78, Rep.). (2021). Jordan, Amman: Jordan Engineers Association.

Arafa, M. and Alqedra, M., (2011). Early-Stage Cost Estimation of Buildings Construction Projects Using ANN. Journal of Artificial Intelligence, 4(1), 63-75. https://doi.org/10.3923/jai.2011.63.75

Balali, A., Valipour, A., Antucheviciene, J., & Šaparauskas, J. (2020). Improving the Results of the Earned Value Management Technique Using Artificial Neural Networks in Construction Projects. Symmetry, 12(10), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym12101745

Bilski, J., Kowalczyk, B., Marchlewska, A., & Zurada, M. J. (2020). Local Levenberg-Marquardt Algorithm for Learning Feedforward Neural Networks. Sciendo: JAISCR, 2020, Vol. 10, No. 4, pp. 299 – 316. https://doi.org/10.2478/jaiscr-2020-0020

Çaliskan, E., & Sevim, Y. (2019). A Comparative Study of Artificial Neural Networks and Multiple Regression Analysis for Modeling Skidding Time. Applied Ecology and Environmental Research. https://doi.org/10.15666/aeer/1702_17411756

El-Sawalhi, N. I., and Shehatto, O. (2013). Cost Estimation for Building Construction Projects in Gaza Strip Using Artificial Neural Network (ANN), Gaza Strip. Master’s Thesis in Construction Management, The Islamic University of Gaza. https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2013.10773209

Fan, S.-L., Yeh, I.-C., & Chi, W.-S. (2021). Improvement in Estimating Durations for Building Projects Using Artificial Neural Network and Sensitivity Analysis. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 147(7), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0002036

Galli, B. J. (2020). Application of Multiple Regression and Artificial Neural Networks as Tools for Estimating Duration and Life Cycle Cost of Projects. International Journal of Applied Industrial Engineering, 7(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJAIE.2020010101

George, D., & Mallery, P. (2003). SPSS for Windows step by step: A simple guide and reference, (4th ed.), 1-63. Retrieved from https://wps.ablongman.com/wps/media/objects/385/394732/george4answers.pdf

Ghasemi, A., & Zahediasl, S. (2012). Normality Tests for Statistical Analysis: A Guide for Non-Statisticians. International Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism, 10(2), 486–489. https://doi.org/10.5812/ijem.3505

Ghritlahre, H. K., & Prasad, R. K. (2018). Application of ANN Technique to Predict the Performance of Solar Collector Systems - A Review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 84, 75–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2018.01.001

Helvaci, A. (2008). Comparison of Parametric Models for Conceptual Duration Estimation of Building Projects, Ankara, Turkey. Master’s Thesis in Civil Engineering, Middle East Technical University.

Juan, Y. K., & Liou, L. E. (2021). Predicting the Schedule and Cost Performance in Public School Building Projects in Taiwan. Journal of Civil Engineering and Management, 28(1), 51–67. https://doi.org/10.3846/jcem.2021.15853

Juszczyk, M. (2015). Application of Committees of Neural Networks for Conceptual Cost Estimation of Residential Buildings. Proceedings of the International Conference on Numerical Analysis and Applied Mathematics, 1648(1), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4912840

Kaur, P. (2016). Artificial Neural Networks As an Effective Project Management Tool. International Journal of Advanced Technology in Engineering and Science (IJATES), 4(7), 229–239. Available at http://ijates.com/images/short_pdf/1470034546_1140ijates.pdf

Kim, H.-Y. (2019). Statistical Notes for Clinical Researchers: The Independent Samples T Test. Restorative Dentistry & Endodontics, 44(3), 2–7. https://doi.org/10.5395/rde.2019.44.e26

Kulkarni, P. S., Londhe, S. N., & Deo, M. C. (2017). Artificial Neural Networks for Construction Management: A Review. Journal of Soft Computing in Civil Engineering, 1(2), 70-88. https://doi.org/10.22115/scce.2017.49580

Larson, E. W., & Gray, C. F. (2013). Estimating Project Times and Costs. Project Management: The Managerial Process, (6th ed.), Chapter 5. 126–155.

Matel, E., Vahdatikhaki, F., Hosseinyalamdary, S., Evers, T., & Voordijk, H. (2019). An Artificial Neural Network Approach for Cost Estimation of Engineering Services. International Journal of Construction Management, 22(7), 1274-1287. https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2019.1692400

Mensah, I., Adjei-Kumi, T., & Nani, G. (2016). Duration Determination for Rural Roads Using the Principal Component Analysis and Artificial Neural Network. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 23(5), 638–656. https://doi.org/10.1108/ECAM-09-2015-0148

Mijwel, M. M. (2018). Artificial Neural Networks Advantages and Disadvantages. Retrieved from LinkedIn. https//www. linkedin. com/pulse/artificial-neuralnet Work

Mubarak, S. (2019). Construction Project Scheduling and Control, (4nd ed.). Canada: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Nani, G., Mensah, I., & Adjei-Kumi, T. (2017). Duration Estimation Model for Bridge Construction Projects in Ghana. Journal of Engineering, Design and Technology, 15(6), 754– 777. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEDT-04-2017-0029

Olawale, Y., & Sun, M. (2014). Construction Project Control in the UK: Current Practice, Existing Problems and Recommendations for Future Improvement. International Journal of Project Management, 33(3), 623–637. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2014.10.003

Petruseva, S., Zujo, V., & Zileska-Pancovska, V. (2012). Neural Network Prediction Model for Construction Project Duration. International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology, 2(11), 1646–1654. Available at https://www.ijert.org/research/neuralnetwork-prediction-model-for-construction-project-duration-IJERTV2IS110333.pdf

Pezeshki, Z., & Mazinani, S. M. (2019). Comparison of Artificial Neural Networks, Fuzzy Logic and Neuro Fuzzy for Predicting Optimization of Building Thermal Consumption: A Survey. Artificial Intelligence Review, 52(1), 495–525. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10462-018-9630-6

Ramachandran, P. Zoph, B. & Le, Q. V. (2017). Searching for Activation Functions. 6th International Conference on Learning Representations, Workshop Track Proceedings, 1–13. Available at https://arxiv.org/pdf/1710.05941

Rauzana, A., & Dharma, W. (2022). Causes Of Delays in Construction Projects in the Province Aceh, Indonesia. PloS one, 17(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263337

Roxas, Cheryl, L. C., Ongpeng, Jason M. C. (2014). An Artificial Neural Network Approach to Structural Cost Estimation of Building Projects in the Philippines. Research Congress. De La Salle University, Manila, Philippines. Retrieved from https://www.dlsu.edu.ph/wp- content/uploads/dlsu-research-congress-proceedings/2014/SEE-I-005-FT.pdf

Sanni-Anibire, M. O., Zin, R. M., & Olatunji, S. O. (2020). Causes of Delay in the Global Construction Industry: A Meta-Analytical Review. International Journal of Construction Management, 48(11), 1395-1407. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjce-2020-0527

Sanni-Anibire, M. O., Zin, R. M., & Olatunji, S. O. (2021). Developing a Machine Learning Model to Predict the Construction Duration of Tall Building Projects. Journal of Construction Engineering, Management & Innovation, 4(1), 22-36. https://doi.org/10.31462/jcemi.2021.01022036

Titirla, M., & Aretoulis, G. (2020). Comparison of Linear Regression and Neural Network Models to Estimate the Actual Duration of Greek Highway Projects. In XIV Balkan Conference on Operational Research, Virtual BALCOR 2020. Retrieved from https://hal.archives- ouvertes.fr/hal-03178692/document

Ujong, J. A., Mbadike, E. M., & Alaneme, G. U. (2022). Prediction of Cost and Duration of Building Construction Using Artificial Neural Network. Asian Journal of Civil Engineering, 23(7), 1117–1139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42107-022-00474-4

Velumani, P., Nampoothiri, N. V. N., & Mariusz, U. (2021). A Comparative Study of Models for the Construction Duration Prediction in Highway Road Projects of India. Sustainability (Switzerland), 13(8), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084552

Wang, Y. M., & Elhag, T. M. S. (2007). A Comparison of Neural Network, Evidential Reasoning and Multiple Regression Analysis in Modelling Bridge Risks. Journal of Expert Systems with Applications, 32(2), 336 - 348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2005.11.029

Weckman, G. R., Paschold, H. W., Dowler, J. D., Whiting, H. S., & Young, W. A. (2010). Using Neural Networks with Limited Data to Estimate Manufacturing Cost. Journal of Industrial and Systems Engineering, 3(4), 257–274. Available at http://www.jise.ir/article_4015.html

Wulandari, D., Sutrisno, S., & Nirwana, M. B. (2021). Mardia’s Skewness and Kurtosis for Assessing Normality Assumption in Multivariate Regression. Enthusiastic: International Journal of Applied Statistics and Data Science, 1(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.20885/enthusiastic.vol1.iss1.art1