Construction Economics and Building

Vol. 25, No. 2

July 2025

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Achieving Zero Waste: Circular Economy Strategies in Australian Higher Education

Olabode Emmanuel Ogunmakinde

School of Engineering and Technology, Central Queensland University, Brisbane, QLD 4000, Australia

Corresponding author: Olabode Emmanuel Ogunmakinde, o.ogunmakinde@cqu.edu.au

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v25i2.9131

Article History: Received 08/05/2024; Revised 05/04/2025; Accepted 28/04/2025; Published 08/08/2025

Citation: Ogunmakinde, O. E. 2025. Achieving Zero Waste: Circular Economy Strategies in Australian Higher Education. Construction Economics and Building, 25:2, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v25i2.9131

Abstract

The circular economy concept, which aims to minimise waste and make the most of resources, has gained global traction as a sustainable alternative to the traditional linear economy. In recent years, Australian universities have increasingly adopted these principles to align with global sustainability goals to reduce environmental impact, enhance resource efficiency, and foster a culture of sustainability within their communities. This study examined the implementation of circular economy protocols in Australian universities to achieve zero waste and promote sustainable practices. Specifically, it assessed universities’ commitment to circular economy strategies, waste reduction, resource optimisation, and the net-zero agenda. The research involved a systematic literature review of 70 sources from 2012 to 2022. Text mining techniques, including co-occurrence analysis, were applied to a secondary dataset to reveal the relationships between circular economy principles and universities, thereby enhancing our understanding of these connections. Emergent themes centred on sustainability-oriented economic models like circular and sharing economies. The analysis underscored the importance of sustainability, collaboration, and locality in achieving waste minimisation goals. Significantly, there was an overlap between circular economy principles and the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Universities showed a growing commitment to these goals through sustainable practices. Region-specific strategies, dynamic collaborations, and community engagement played key roles in waste minimisation. The adoption of sustainable economic models, including the circular economy, was prominent. In conclusion, the study provides insights into universities’ roles in waste reduction, resource optimisation, and supporting the transition to a net-zero, circular economy.

Keywords

Australian Universities; Circular Economy; Natural Language Processing; Sustainable Development Goals; Zero Waste

Introduction

The circular economy (CE) represents a systemic shift that builds long-term resilience, generates business and economic opportunities, and provides environmental and societal benefits (Rocca, Veneziani and Carini, 2023). The premise of a circular economy is to minimise waste and make the most of resources, consequently reducing the environmental impact and generating value from what was once considered waste. Higher education institutions, including universities, are emerging as key stakeholders in this transition, given their role in fostering knowledge, innovation, and societal transformation (Serrano-Bedia and Perez-Perez, 2022). Universities are incorporating the principles of CE in their curriculum and implementing them in their operations. However, the shift towards a circular economy within universities is not without challenges. Key issues revolve around budget constraints, particularly in public schools, where the influx of students and the relative stagnation of funding sources pose considerable problems (Dieleman and Martínez-Rodríguez, 2019). Implementing CE requires understanding the entire systemic level, requiring the cooperation and integration of various stakeholders, such as businesses, consumers, and governments. This broad cooperation can often be complex and challenging to manage (Serrano-Bedia and Perez-Perez, 2022). Additionally, universities must address the competitive environment of higher education institutions and successfully navigate the need for sustainable transformation while ensuring their reputation and academic excellence (Maruyama, et al., 2019). Overall, the journey to a circular economy within universities is fraught with complexities, but it also holds the potential for profound change and progress towards a sustainable future.

Emphasising the urgent need for transformations in waste management, researchers have delineated the prospect of aligning the Australian construction and demolition waste management system with the principles of the circular economy (Shooshtarian, et al., 2022). A similar paradigm shift has been advocated in other sectors. For instance, regional economies in Australia have begun to adopt circular economy practices, pointing to the nascent and broadening interest in this area (Fleischmann, 2019). Moreover, circular economy-oriented actions are not confined to the industrial and business sectors. Australian universities have committed to a circular economy and net-zero emissions (Study Australia, 2023). These trends indicate a wider acceptance and implementation of the circular economy framework in diverse Australian sectors. In light of these, digital technologies have been recognised as integral in guiding circular economy practices towards achieving net-zero emissions. This aligns with the view that net-zero cities and circular economy strategies offer multiple avenues for cities to fully realise a net-zero future. The intertwined nature of the circular economy and net zero suggests that progress in one area can have positive spillover effects on the other. Furthermore, it has been highlighted within academia that universities can contribute to the energy transition and circular economy principles (Cahill, 2021). Universities like Monash University have established net-zero initiatives, embodying circular economy principles to prioritise the transition to sustainability, which is in line with their strategic plan (Impact 2030) and environmental, social, and governance (ESG) statement.

The aim of this study was to investigate the implementation of circular economy protocols in Australian universities, with a focus on achieving zero waste and promoting sustainable practices. This includes assessing universities’ commitment to circular economy strategies, waste reduction, resource optimisation, and the net-zero agenda, using text mining techniques and co-occurrence analysis to elucidate the relationships between these principles and higher education institutions.

Literature review

Australia’s net-zero agenda and the position of universities

The net-zero agenda in Australia, a response to the global call for climate change mitigation, signals the nation’s commitment to drastically reduce its greenhouse gas emissions to achieve carbon neutrality (Bernecker, et al., 2022). This transition to net zero is intended to realise environmental sustainability, economic resilience, and social justice. Australian universities hold a critical role in successfully executing this agenda, not only as educational institutions shaping future generations but also as leading research centres and significant operational entities with substantial carbon footprints. The transition towards a net-zero future presents various challenges that require innovative solutions, many of which can be conceived within university campuses. From establishing net-zero programs to pioneering green energy strategies, universities across Australia have been at the forefront of transitioning to a low-carbon future (Hull, 2023). For instance, as part of its ambitious M-program, Monash University aims to transform its campuses into net-zero spaces, showcasing its pioneering position in urban planning and sustainable practices. The net-zero commitment also extends beyond operational transformations. For example, the Australian National University has pledged to achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2025 and has revised its travel policies to promote sustainability (ANUB Zero, 2022). This illustrates how universities are embedding sustainability into their governance and policy-making processes.

Furthermore, universities are crucial in generating research and knowledge on climate change and sustainability, significantly influencing policy pathways towards a net zero-carbon-built environment (Prasad, et al., 2023). The academic community is also studying the implications of net-zero emission targets on organisational practices and financial markets, underlining the breadth of this agenda’s impact (Parashar, 2023). Australian universities are actively engaging in and contributing to the national net-zero agenda. Australian universities lead by example, innovate in their operations, and provide valuable insights through their research. The societal position affords them a privileged platform for leading and facilitating change (Hull, 2023). In their capacity as education providers, research hubs, and large-scale operational entities, universities are primed to implement effective strategies that align with the net-zero ambition. Notably, their actions are not limited to energy use or operational modifications. Consequently, universities are revising policies in broader areas, such as university-related travel, reflecting their commitment to overarching sustainability (ANUB Zero, 2022).

Collaborative research, inter-university cooperation, and alliances with governments and private sectors are vital to the universities’ approach. These partnerships promote sharing best practices, drive systemic change, and add value through a net-zero energy strategy (Roche, et al., 2022). Universities’ research also provides a foundational understanding of the economic, social, and environmental implications of transitioning to a net-zero future, thus informing policy pathways and driving critical discourse (Prasad, et al., 2023; Parashar, 2023). Undoubtedly, universities are instrumental in ensuring that Australia’s net-zero agenda is successful. Through their actions, universities reduce their carbon footprint and influence the behaviour and attitudes of their students, staff, and wider communities. Australian universities form a crucial nexus of knowledge, innovation, and action, pushing boundaries and exploring novel pathways to sustainability. Thus, the journey to net zero offers a unique opportunity for Australian universities to further their mission of creating a positive societal impact and preparing future generations for a sustainable, low-carbon world.

Circular economy strategies in Australia

The importance of a circular economy for resource optimisation and waste reduction aligns with the United Nations’ sustainability agenda through the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 11 (Moghayedi, et al., 2021). The circular economy aligns with sustainability principles by espousing the judicious use and reuse of resources, with the construction industry playing a pivotal role in such implementation (Osobajo, et al., 2022). Nonetheless, the interplay between systems thinking and continuous improvement in this sector is worth noting, underlining the need for a holistic, not fragmented, approach (Omotayo, et al., 2020). The circular economy should not be viewed as a panacea for all environmental woes but considered part of a broader sustainability strategy. Additionally, the management of post-consumer waste, as depicted by Oke, et al. (2021), presents a key area in which the circular economy can concretely manifest. However, this necessitates an understanding and adaptation to consumer sentiments. The review of sustainability performance reporting by Osobajo, et al. (2022) underscores the importance of consistent, critical evaluation and transparency for continuous improvement in sustainability and circular economy strategies.

Embarking on a circular economy necessitates a holistic transformation, incorporating far-reaching modifications to business frameworks, supply chains, and financial systems. This transition is underpinned by inventive thought and a collaborative ethos shared by the entirety of the university community, including students, teaching and administrative personnel, stakeholders, and wider society (Maruyama, et al., 2019). Furthermore, the task for universities to incorporate principles and practices associated with the circular economy into their academic syllabi has emerged. This undertaking calls for a novel pedagogical model that advocates for sustainable cognition and the real-world application of circular economy tenets (Serrano-Bedia and Perez-Perez, 2022). By doing so, higher education institutions can play a critical role in equipping future generations with the necessary skills and knowledge to address a world marked by limited resources and assist in hastening the transition towards a more sustainable economic and social framework (Rocca, Veneziani and Carini, 2023). While the transition towards a circular economy provides an attractive solution to the sustainability hurdles facing universities, the shift itself is an intricate process requiring significant dedication, resource distribution, and a cultural revolution. However, this move to a circular economy presents an exceptional opportunity for universities to spearhead sustainability endeavours and contribute substantially to a more environmentally friendly and sustainable future. When scrutinising the incorporation of circular economy strategies within Australia, it is evident that numerous potential advantages are on offer.

Nevertheless, the journey to realising these benefits is filled with obstacles and intricacies. This section critically dissects these strategies, particularly emphasising the construction industry—a major contributor to waste—and the broader Australian economy. Adopting a circular economy within the Australian construction and demolition waste management system is critical. Shooshtarian, et al. (2022) proposed the Less of Waste, More of Resources (LoWMoR), a model premised on circular economy principles, to steer the analysis of pertinent Australian literature. The model underscores waste reduction, reuse, and recycling, aiming to minimise the environmental footprint of construction activities. However, it is essential to confront the barriers impeding the successful introduction of the circular economy model in this sector, such as regulatory constraints, market deficiencies, and a lack of awareness and education. Simultaneously, efforts to incorporate circular economy principles are discernible across the wider Australian economy. Halog, et al. (2021) charted the evolution and insights gleaned from circular economy strategies in Australia, accentuating the need for a deeper introspection into Australia’s potential. Notably, the shift towards a circular economy model has not been uniform across different sectors, which is a testament to each industry’s complexity and distinct nature.

Shooshtarian, et al. (2023) investigated the hindrances and catalysts influencing the circular economy within Australia’s architecture, engineering, and construction (AEC) industry. They underlined the necessity to confront technical, economic, and behavioural barriers to the circular economy. The authors advocated for policy interventions and industry development activities suitably tailored to the specific context of the Australian AEC industry. Circular economy strategies in Australia span various sectors and engage diverse stakeholders. Acknowledging and addressing the unique challenges posed to each sector, harnessing their potential, and devising contextually appropriate strategies are paramount. The shift towards a circular economy requires a systemic approach, integrating policy, practice, and societal behavioural modifications to accomplish sustainability. Incorporating circular economy strategies in Australia is a promising yet multifaceted endeavour. The challenges may be numerous, but the potential benefits are equally substantial. Overcoming the barriers to a circular economy requires strategic planning, robust policy support, industry collaboration, educational initiatives, and a commitment to perpetual learning and adaptation.

Waste reduction and resource optimisation for circular economy in Australian universities

In light of the global call for sustainability, Australian universities are shifting focus towards the principles of a circular economy, particularly in waste reduction and resource optimisation. Universities can drive a circular economy and improve resource sustainability through engagement with the waste management and resource recovery sector (Shooshtarian, et al., 2022). However, examining how these engagements are being materialised and the inherent challenges posed by this paradigm shift is critical. Although Australian universities are posited as crucial actors in the circular economy, there is a dearth of detailed studies on integrating circular economy principles into their operational and strategic frameworks. It is not merely enough to advocate for waste reduction and resource optimisation; specific, actionable strategies must be developed and implemented.

Furthermore, the benefits of university–industry engagement in driving the circular economy must be systematically evaluated and optimised. Given Australia’s mineral-rich landscape, the mining industry’s role in a circular economy is particularly noteworthy. Although Lèbre, Corder and Golev (2017) proposed a framework for resource management at the mine site level, the application of such strategies within Australian universities remains underexplored. Mining-related courses could incorporate circular economy principles to prepare future professionals for sustainable resource management, thereby optimising mineral utilisation. Universities could learn from their innovative practices, such as using solar-powered energy systems, to reduce resource consumption and enhance campus sustainability. While Australian universities have begun to embrace the circular economy’s principles, there is still significant scope for improvement. Systemic changes, cross-sectoral collaboration, and a critical reassessment of current practices are necessary to achieve sustainability in waste reduction and resource optimisation. Implementing a circular economy within the sustainable development of universities in Australia necessitates multi-level thinking, including innovations in housing and construction, incentivisation for green practices, and effective waste management. However, the aspiration for a circular economy must be tempered with realistic expectations, aligned with broader sustainability strategies, and supported by comprehensive, transparent reporting mechanisms. Through these multifaceted approaches, a circular economy can be optimised, delivering its full potential for environmental sustainability and continuous improvement in the built environment. Thus, the text mining approach would be applied to ensure that lessons from other universities globally are extracted for Australian universities as a contribution to knowledge.

Natural language processing: text mining for circular economy research

The adoption of text mining in big data analytics has transformed how researchers and practitioners interpret large amounts of unstructured data, fundamentally altering the landscape of knowledge discovery (Hassani, et al., 2020). Nevertheless, it is paramount to acknowledge the intricacies and constraints associated with its deployment. Feldman and Sanger (2007) noted that the architecture of text mining systems may be bound by constraints, which can impact the potential outcomes. Ignatow and Mihalcea (2016) extensively surveyed text mining tools, elucidating the benefits, drawbacks, and suitability for specific research questions and data types. Such a nuanced understanding can guide the apt application of text mining in diverse contexts. O’Mara-Eves, et al. (2015) advocated for applying text mining to identify themes in systematic reviews, albeit acknowledging the nuances associated with the process. Text mining provides a powerful tool in big data analytics. Its implementation necessitates a keen awareness of its limitations and appropriate usage contexts, thereby ensuring the delivery of insightful and accurate analyses.

Among text mining techniques, Natural language processing (NLP) is exceptional for its in-depth analysis and interpretation of human language. Unlike the common keyword-based methods, which utilise precise matches and may neglect context, NLP employs machine learning and linguistic principles to determine the meaning of words, phrases, and sentences (Khan, et al., 2023). This enables more precise entity identification, topic modelling, and sentiment analysis (Jim, et al., 2024). NLP models may automatically learn from big datasets, improving over time compared to statistical techniques (Gudivada, Rao and Raghavan, 2015). Overall, NLP’s capacity to manage ambiguity, context, and the nuance of human language makes it a better option for drawing significant insights from text.

The application of capability maturity modelling for circular economy implementation

The concept of the Capability Maturity Model (CMM), originally applied in information technology fields, has been extended to shed light on the implementation of the circular economy (Howard, et al., 2018). This adoption is an innovative methodological approach and underscores the potential for interdisciplinary dialogue to address complex sustainability challenges. The development of the CE CMM provides a new lens to understand how organisations evolve their practices towards more sustainable production and consumption patterns (Miemczyk, Carbone and Howard, 2022). The multi-level perspective offered by this model is a nuanced approach that recognises the factors at the individual, organisational, and systems levels that play a crucial role in successfully implementing CE principles. Similarly, Brendzel-Skowera (2021) engaged with the concept of organisational maturity concerning the circular economy, particularly within the small and medium enterprises (SME) sector. The study contributes valuable insights into the practical application of the circular economy, especially within an organisational context traditionally seen as less equipped to engage with sustainable innovation. Furthermore, the application of the CMM and systems thinking has also been highlighted in the construction industry, demonstrating its relevance for continuous improvement (Omotayo, et al., 2020). In another study by Omotayo and Kulatunga (2017), an IDEF0-based continuous improvement framework was proposed for post-contract cost control, underscoring the potential of these approaches for strategic realignment and process improvement.

Research aim

Incorporating the CMM in the sphere of the circular economy portends a significant step forward in operationalising the principles of sustainable development in diverse sectors and not only universities. This research highlights holistic and multi-level perspectives that acknowledge the dynamic interplay between various elements within complex systems of circularity in university campuses for implementation in Australian universities. To reduce the typologies of circularity for a CMM, text mining analysis would be deployed as part of the natural language processing approach.

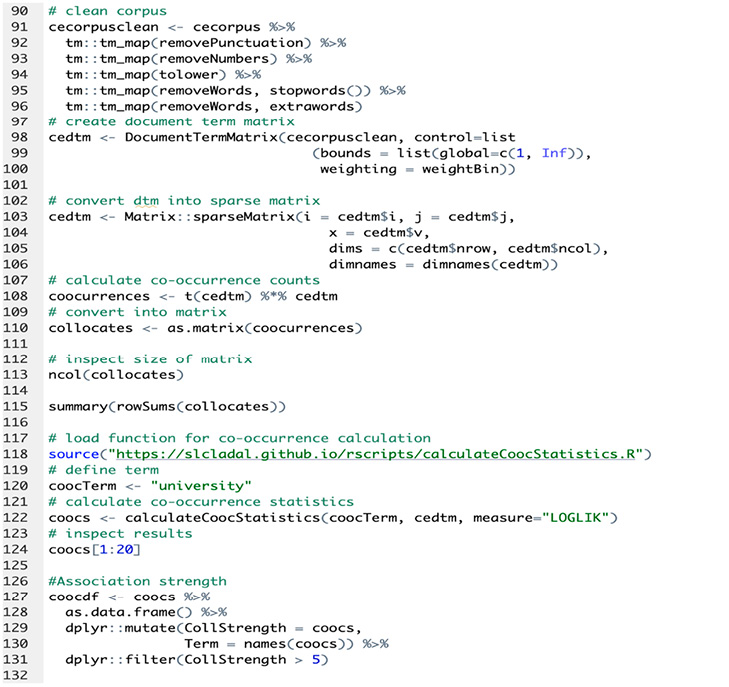

Method and materials

Figure 1 illustrates the flowchart of the methodological process employed in this study. The research was conducted to scrutinise the interplay of Australian universities in the facilitation of CE strategies, waste reduction and resource optimisation, and their stance on the net-zero agenda through a qualitative secondary data approach. A systematic review of the literature published from 2012 to 2022 used the keywords in Table 1. The 70 peer-reviewed articles, conference papers, books, and chapters were extracted as full text. The publications concentrated on the circular economy and related aspects within the context of Australian universities. The data were compiled from Scopus academic databases. The exclusion criteria, as presented in Table 2, were established to filter out non-peer-reviewed reports, opinion pieces, dissertation news articles, and publications over a decade old. A co-occurrence analysis was conducted in RStudio to understand the relationships between various terms within the dataset. This process involved calculating co-occurrence counts and statistics, visualising the results using dendrograms, and performing significance testing.

Figure 1. Methodological flowchart.

Source: Author’s own (2024)

Table 2 outlines the selection criteria for the studies used in the research. The inclusion criteria target scholarly publications from 2012 to 2022 in English, focusing on the circular economy and related subjects, specifically in the context of Australian universities. These publications must offer full access, emanate from Australia, and have undergone rigorous peer review. The exclusion criteria discard news articles, non-academic reports, older studies, publications in languages other than English, studies irrelevant to the defined subjects, those lacking a clear methodology, studies conducted outside Australia or not specifically targeting Australian universities, and studies with poor methodological quality.

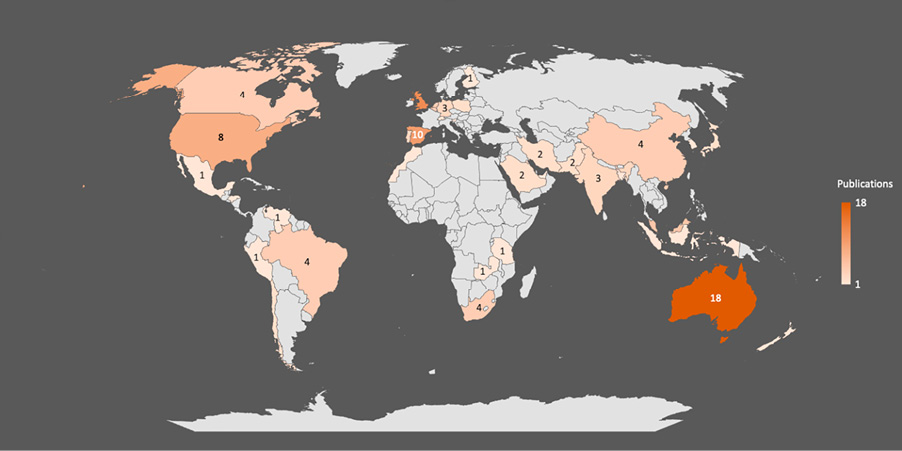

With 18 publications, as indicated in Figure 2, Australia leads the academic discourse on the circular economy and sustainable practices in universities, contributing to 14.2% of the selected works. The United Kingdom and Spain, with 12 and 10 publications, respectively, contribute 17.4% of the studies. The United States (eight publications) and Malaysia (five publications) account for 10.3% of the total works, while other nations like Belgium, Brazil, Canada, China, the Netherlands, and South Africa, each with four publications, collectively comprise 15.9%. The remaining countries collectively contribute 42.2% of the total publications, affirming the widespread global interest in this topic.

Figure 2. Distribution of publications used in the text mining analysis.

Source: Author’s own (2024)

Analysis

Text mining through co-occurrence

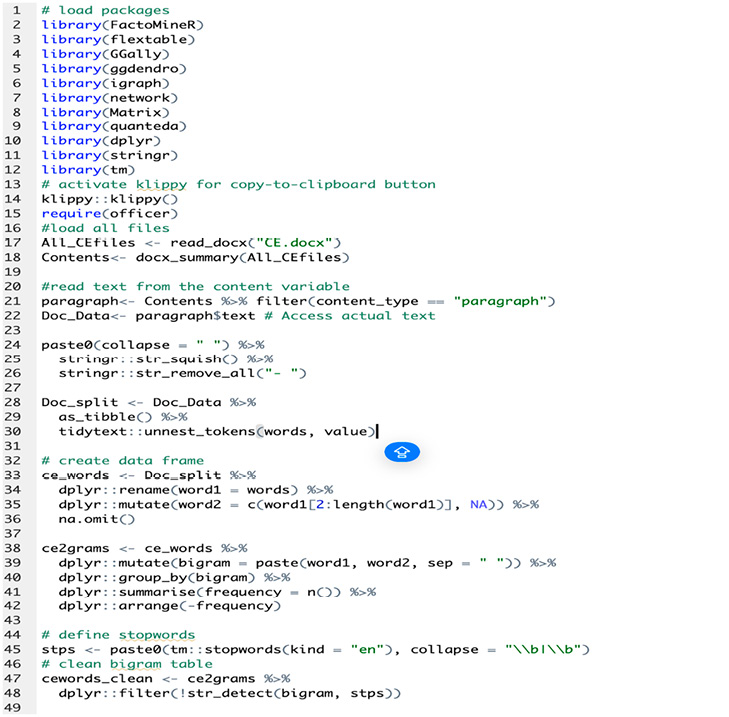

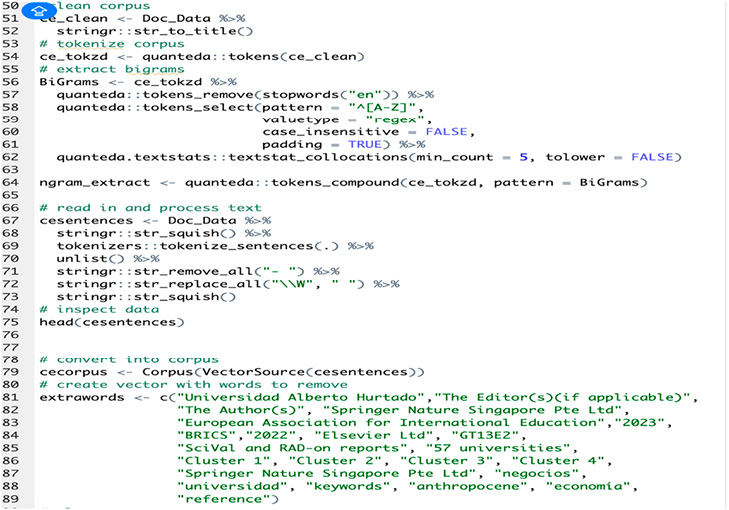

Using RStudio, the co-occurrence of keywords on the circular economy and Australian universities was conducted (see Appendix A). The R script used to perform a text mining and analysis task followed the following steps:

Step 1. Load packages: The code loads the necessary R packages for text analysis, network analysis, and visualisation.

Step 2. Activate klippy: klippy::klippy() activates a copy-to-clipboard button, which can be handy for copying results or data to the clipboard.

Step 3. Load files: It reads in a Word document using the read_docx function from the officer package. Then, it extracts the summary of contents from the document.

Step 4. Read text: It extracts the paragraphs from the content and then accesses the actual text. It then cleans the text by squishing multiple spaces into single spaces and removing all “-”.

Step 5. Tokenisation: It splits the text into individual words (tokens) using the tidytext::unnest_tokens function.

Step 6. Create data frame: It creates a data frame of bigrams, which are pairs of words that appear together, and counts their frequencies.

Step 7. Define stopwords: It defines stopwords, words that are to be ignored in the text analysis.

Step 8. Clean bigram table and corpus: It cleans the bigram table and corpus by removing the stopwords.

Step 9. Tokenise corpus: It tokenises the cleaned corpus and extracts the bigrams.

Step 10. Text processing: It squishes the sentences, removes punctuation and non-word characters, and squishes spaces again.

Step 11. Corpus construction: This step entails the formation of a corpus derived from the refined sentences.

Step 12. Supplementary purification: This phase involves the further sanitisation of the corpus by eradicating punctuation and numerical values, converting all text to lowercase, and excising additional specific words.

Step 13. Development of document-term matrix: This step engenders a document-term matrix (DTM), a mathematical matrix that portrays the frequency of term occurrences within a compendium of documents.

Step 14. Computation of co-occurrence tally: This stage calculates the co-occurrence tally, revealing the frequency with which terms appear jointly within a document.

Step 15. Co-occurrence metrics: During this stage, the computation of co-occurrence statistics for a specific term occurs. This process aids in comprehending the context in which the term is used.

Step 16. Visualisation of findings: This phase involves the visual representation of results using various plotting styles, such as dendrograms.

Step 17. Testing for significance: The final step involves conducting significance tests to ascertain whether the observed co-occurrences are of statistical significance.

One of the primary methods to quantify co-occurrence or association between two or more terms is to calculate the pointwise mutual information (PMI). PMI is a measure of association used in information theory and statistics. The formula is given as follows:

PMI(x, y) = log [P(x, y)/(P(x) * P(y))](1)

P(x, y) is the probability of both words x and y occurring together.

P(x) and P(y) are the probabilities of words x and y occurring independently.

The probability of a word occurring in a text could be calculated by integrating all the positions in the text where the word could occur, normalised by the total length of the text:

P(x) = ∫ dx/L(2)

dx represents an infinitesimal segment of the text where the word x occurs.

L is the total length of the text.

The joint probability of two words occurring together could be calculated by integrating over all the pairs of positions in the text where the words could occur together, normalised by the total number of such pairs:

P(x, y) = ∫ dx dy/(L^2)(3)

dx and dy represent infinitesimal text segments where x and y occur, respectively.

L is the total length of the text. These formulas are somewhat abstract and not directly used in practice, as in real-world applications, we generally count the occurrences and co-occurrences directly rather than integrate them over the text.

The natural logarithm (ln) was used in the PMI calculation instead of the base-2 logarithm (log2) to maintain consistency with the statistical methods employed throughout the analysis. Although the base-2 logarithm is commonly used in information theory and NLP applications (Pantel and Lin, 2002; Martin and Jurafsky, 2009), the choice of logarithmic base does not affect the relative ranking of PMI values. The logarithmic base merely scales the results without altering their comparative significance. Consequently, the findings of this research remain consistent, as the relationship between the terms in the analysis is preserved across varying logarithmic bases.

Co-occurrence analysis through text mining

Co-occurrence tables and dendrograms are statistical tools that allow researchers to understand and visualise relationships between different terms or variables within a dataset. A co-occurrence table displays how frequently certain terms appear together in a dataset. This table often includes additional metrics like Phi (φ), a measure of association between two terms, and chi-squared (χ2), which tests the independence of two terms. A higher φ-value indicates a stronger relationship, while a higher χ2-value signifies a stronger divergence from expected independent frequencies. “CoocTerm” refers to the term that co-occurs with the main term, while “TermCoocFreq” is the frequency of their co-occurrence. A dendrogram is a tree-like diagram used to illustrate the arrangement of the clusters produced by hierarchical clustering. Each branch of the dendrogram represents a cluster, and the height of the branch indicates the distance (or dissimilarity) between clusters. Reading a dendrogram starts from the “leaves” and moves towards the “root”. The more closely connected the “leaves”, the more similar they are. Therefore, both tools provide insight into relationships within data, aiding in identifying patterns, similarities, or differences that may not be immediately apparent from raw data.

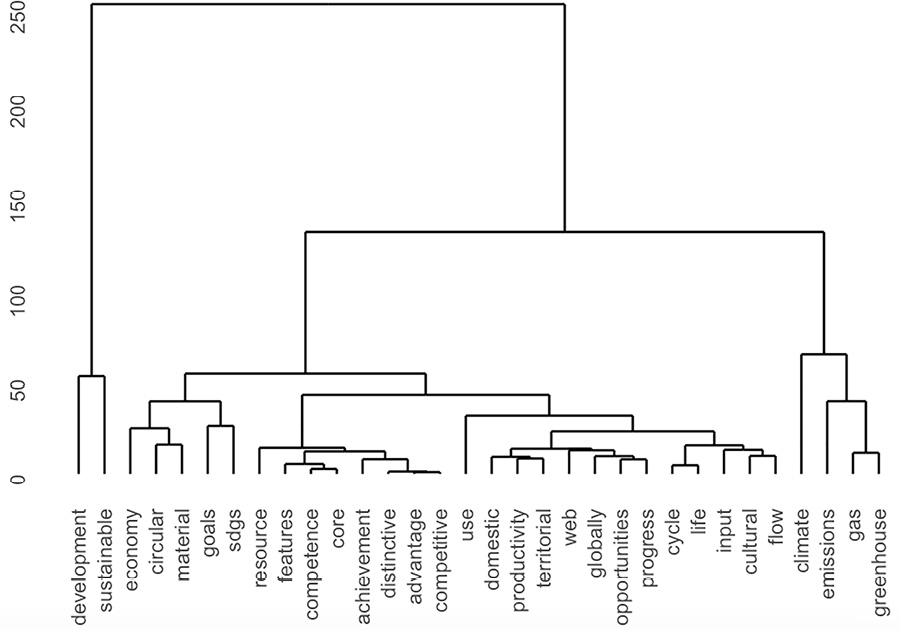

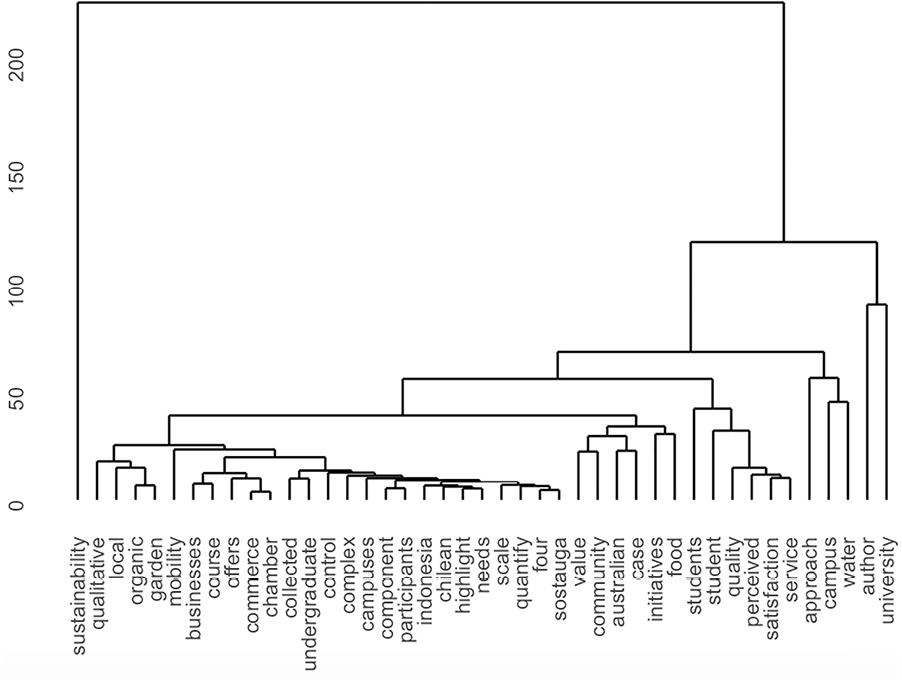

In the context of the “economy” (Figure 3), the most significant co-occurring terms include “circular”, “sharing”, “material”, “sdgs” (Sustainable Development Goals), and “achievement”. Each of these terms is statistically significant (p < .001) and indicates a higher-than-expected frequency of co-occurrence with the term “economy”. This may point towards a shift in economic discourse towards sustainability and resource efficiency, with the high occurrence of “circular” and “sharing” suggesting increased interest in circular and sharing economy models, respectively. “Material” could be connected to discussions around material usage and efficiency, while “sdgs” suggests a focus on sustainable development. Finally, “achievement” may indicate attention to achieving these sustainability-oriented economic goals. Regarding the “university” context (Figure 4), the terms “partnerships”, “Australian”, “sustainability”, “community”, and “author” occur significantly more often (p < .001). This may imply universities’ increasing focus on sustainability and collaborative work or partnerships. The high association of “Australian” with “university” could reflect an Australian context or a specific focus on Australian universities. “Community” may refer to the university community or the broader local community where universities operate. The co-occurrence with “author” may suggest the importance of individual authors in university discourse or research outputs. These combinations suggest emerging themes around sustainable development, resource efficiency, and collaboration in both the economy and university sectors, with potential regional distinctions.

Figure 3. Dendrogram for the circular economy co-occurrence context.

Source: Author’s own (2024)

Figure 4. Dendrogram for the university co-occurrence.

Source: Author’s own (2024)

In terms of emerging themes within the context of “economy”, the dominance of terms like “circular”, “sharing”, and “material” underscores a growing interest in sustainability-oriented economic models. The circular economy is a system aimed at minimising waste and making the most of resources. Conversely, the sharing economy is a socio-economic system built around sharing human and physical resources. The term “material” may indicate discussions around material science or material efficiency in this circular and sharing economy paradigm. The term “sdgs” stands for Sustainable Development Goals, suggesting a growing concern about integrating these global goals into economic policy and practice. The co-occurrence of “achievement” could refer to the measurement or attainment of these goals. On the “university” side, “partnerships” hints at an increased emphasis on collaborative work, possibly towards a shared goal such as achieving the sdgs. “Australian” may signify specific studies or policies related to Australian universities or suggest a geographic focus on this region. “Sustainability” underscores the increased role of universities in promoting sustainable practices and education. “Community” may indicate a growing awareness of universities’ roles and responsibilities to local communities. Lastly, “author” may focus on individual academic contributions or indicate the university’s role in producing scholarly work. The data suggest that the “economy” and “university” sectors are becoming increasingly intertwined with themes of sustainability, collaboration, and locality, driven by a shared desire to address global challenges such as the Sustainable Development Goals.

Based on the dendrogram in Figures 2 and 3 and Table 3 for the circular economy and Australian universities, the emerging combination of themes is adopting SDGs towards a circular economy, collaboration, and partnership; Australian region-specific contexts; community engagement; and Australian university circular economic models. These themes will be discussed as contributions of the study.

Discussion

Contribution to knowledge: zero waste lessons for Australian universities towards a circular economy

Adopting sustainable development goals towards a circular economy

As the circular economy garners interest, it becomes a pivotal platform to operationalise the United Nations’ SDGs (Ogunmakinde, Egbelakin and Sher, 2022). Halog and Anieke (2021) noted a significant overlap between the concepts of the circular economy and SDGs, suggesting their co-dependence and mutual reinforcement in fostering sustainable development. The application of the circular economy extends to various sectors, including construction, where waste minimisation has profound implications for sustainability (Ogunmakinde, Egbelakin and Sher, 2022). Successfully implementing circular economy strategies requires knowledge sharing and capacity building. Universities, as knowledge hubs, play a crucial role in this respect, although barriers persist in integrating circular economy concepts into their curricula (Halog and Anieke, 2021). Addressing these challenges necessitates robust strategies that embed circular economy principles into educational institutions and broader society.

University collaboration and partnership for waste reduction and resource optimisation

In sustainable development, collaborations and partnerships are instrumental in driving positive change. This is particularly true in waste reduction and resource optimisation, where academia can offer innovative solutions. With their rich pool of resources and intellectual capital, universities are increasingly seen as key players in spearheading sustainability initiatives (Massaro, et al., 2021). One such example is the strategic design approach developed by a partnership between Politecnico di Milano University and Bocconi University. This approach encourages systemic resource optimisation and stimulates the formulation of beneficial relationships and partnerships that facilitate environmentally friendly innovation. Equally, in reverse logistics, cooperative alliances can optimise recycling vehicle routing. The application of such cooperation in two-echelon reverse logistics networks has proven to be effective in improving the stability of the network (Wang, et al., 2018). By fostering collaborations and partnerships, universities, industry, and other stakeholders can make significant strides in achieving the dual objectives of waste reduction and resource optimisation.

Australian region-specific contexts of circular economy

Delving into region-specific contexts, the CE takes on unique characteristics influenced by local cultural, socio-economic, and environmental factors. In Australia, for instance, CE strategies are tailored to suit its distinct regional contexts, enhancing effectiveness and relevance (Arora, Mutz and Mohanraj, 2023). A detailed understanding of end-of-life (EoL) options for materials, particularly plastics, is vital in these region-specific approaches. For example, Venkatachalam, Pohler and Spierling (2022) underscored the significance of life cycle assessment in defining system boundaries for plastic waste management in specific regions. The interplay of local contexts and CE strategies underlines the complexity yet feasibility of transitioning to sustainable practices, underscoring that successful implementation is always embedded in the region’s specificities.

Australian university community engagement for waste minimisation

The transformation towards a circular economy within the Australian construction and demolition waste management system necessitates dynamic interactions and collaborations (Shooshtarian, et al., 2022). University–industry engagement (UI-E) plays a crucial role in achieving waste minimisation objectives, highlighting the significance of cross-sector partnerships. Moreover, understanding cultural diversity and community attitudes towards waste is paramount, as exemplified in the Canterbury-Bankstown study (James, et al., 2019). Such shared responsibilities and community engagement provide a nuanced comprehension of waste management, fuelling context-specific waste reduction strategies. Hence, it is clear that a successful transition to a circular economy hinges on collective efforts that encapsulate industry, academia, and community perceptions.

Australian university circular economic models

The shift to sustainable economic models within the academic sector is a focal point in Australia’s transition towards a circular economy, with various universities implementing innovative practices and conducting substantive research. Fleischmann (2019) expounded on this, detailing how Queensland universities play a significant part in instigating circular economy practices. However, there is an imperative need for the industry to transition from linear supply chain models to circular ones, a challenge that universities could overcome through research and collaboration with industry stakeholders (Shooshtarian, et al., 2023). As such, the role of Australian universities extends beyond pedagogy and research, forging a path towards a sustainable and circular future for the entire society.

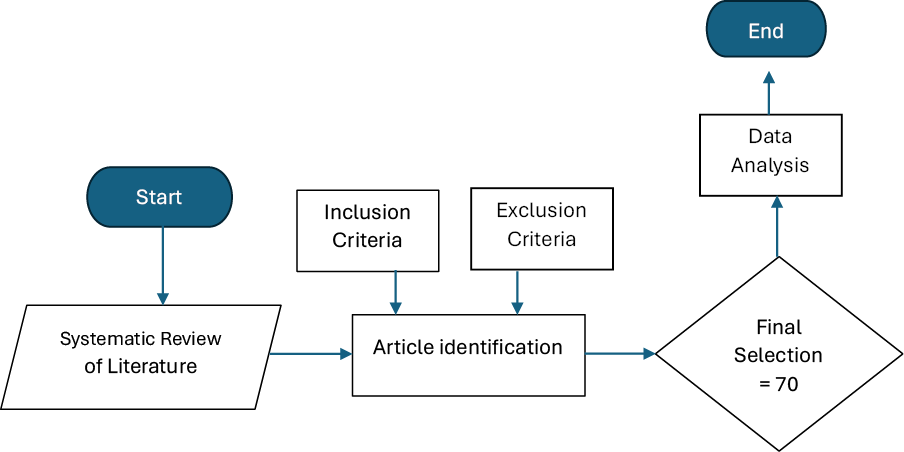

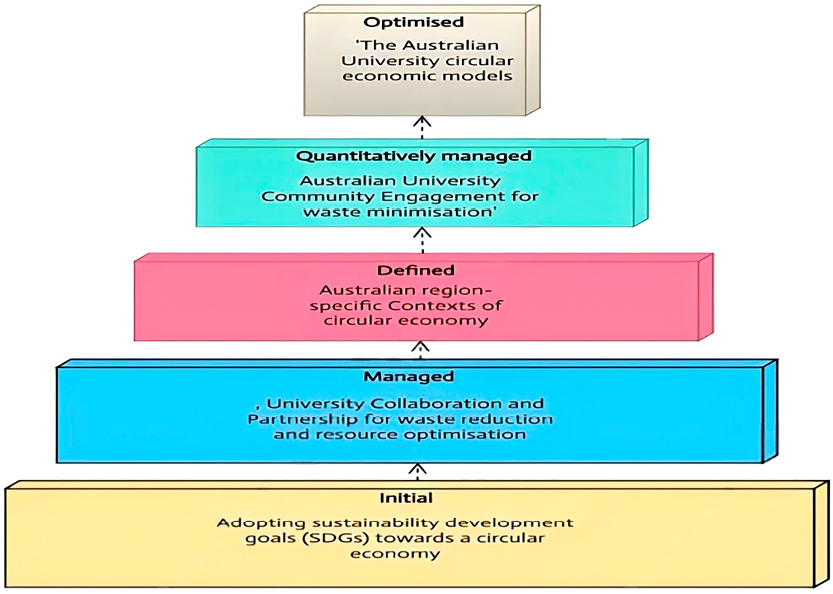

Capability maturity modelling for circular economy in Australian universities

As the discourse around sustainable development gains traction, the integration of the CE concept in various sectors is becoming an area of intense focus. Achieving a CE necessitates a series of structured stages, defined through the lens of a CMM, a tool that facilitates continuous improvement by incrementally building upon existing capabilities (Omotayo, et al., 2020; Howard, et al., 2018). The CMM is divided into five states: initial, managed, defined, quantitatively managed, and optimising. Combining these five stages with the themes provided, the CMM for the circular economy in Australian universities was structured accordingly (Figure 5).

Figure 5. CMM for circular economy attainment in Australian universities. CMM, Capability Maturity Model.

Source: Author’s own (2024)

The first stage, “Adopting sustainable development goals towards a circular economy”, entails embedding SDGs within organisational objectives to drive the transition towards CE. The CMM at this level revolves around understanding the nuances of CE and gearing organisational strategies towards SDG attainment.

The second stage, “University collaboration and partnership for waste reduction and resource optimisation”, reflects the critical role of academic institutions in shaping the circular transition (Omotayo, et al., 2020). The development of a CMM at this juncture involves fostering synergies between industry and academia to enhance waste management and resource efficiency.

The third stage, “Australian region-specific contexts of circular economy”, highlights the significance of regional nuances in the CE adaptation process. CMM development in this context would necessitate understanding and adapting to regional-specific constraints and opportunities.

In the fourth stage, “Australian university community engagement for waste minimisation”, the focus shifts towards leveraging university-led initiatives for community awareness and engagement in waste reduction (Omotayo, et al., 2020). The CMM at this level would map the progression of community engagement activities.

In the last stage, “The Australian university circular economic models” accentuates the role of universities in shaping CE practices through research and innovation (Brendzel-Skowera, 2021). Here, the CMM would track the evolution of university-led circular business models and their impact on broader CE transformation.

By structuring the CE transition in these stages, organisations can apply the CMM to benchmark their progress, identify areas of improvement, and drive continuous advancement towards a circular economy.

The findings of this study highlight the theoretical significance of integrating circular economy principles within higher education institutions. By demonstrating the alignment between circular economy practices and the United Nations’ SDGs, the study underscores the potential for universities to serve as catalysts for broader societal shifts towards sustainability. The emergent themes of collaboration, locality, and sustainability-oriented economic models suggest that universities can play a pivotal role in fostering sustainable development.

Conclusion, limitations, and further research

The assimilation of a CMM into Australian university frameworks exhibits an innovative approach to driving the transition towards a CE. Encompassing various stages, from SDG adoption to developing region-specific contexts, this methodology has the potential to catalyse considerable positive change. Each progressive stage introduces new objectives that culminate in optimising circular economic models within universities. The breadth and depth of Australian contributions to academic discussions around CE and sustainable practices further underscore the country’s leadership. Nevertheless, this intricate process does not come without its challenges. For instance, the initial stage of understanding CE nuances and aligning them with SDGs can be complex, demanding meticulous strategic planning. Simultaneously, contrasting objectives and operational practices may hinder fostering meaningful collaborations between academia and industry. Moreover, regional-specific contexts can introduce unique variables that may complicate the standardised approach offered by the CMM. Lastly, engaging communities effectively for waste minimisation and gauging the impact of university-led circular models can be a daunting task due to the diverse interests of stakeholders. Therefore, it would be valuable to explore the specific mechanisms through which universities can enhance their circular economy initiatives, including the role of policy frameworks and stakeholder engagement. More so, examining the long-term impacts of these initiatives on both academic and local communities could provide deeper insights into the effectiveness of circular economy strategies in achieving sustainability goals.

Additionally, using text mining as an analytical tool, although powerful, has limitations. The architecture of text mining systems may inadvertently impose constraints that affect potential outcomes. Furthermore, the suitability of this tool is highly dependent on the research questions and data types at hand, necessitating a clear understanding of its application context. Consequently, a balanced perspective is needed to harness the benefits of text mining while acknowledging and navigating its limitations. The NLP approach in this study faces challenges such as data sparsity, which can lead to unreliable word association estimates, especially in smaller datasets. Language ambiguity, including polysemy and homonymy, also affects model accuracy. Additionally, generalising models across different contexts is difficult due to the variability in language use across domains. Therefore, there is a need for methods to mitigate data sparsity in smaller datasets. Also, the complexity of integrating the CMM within universities serves as a reminder of the multifaceted nature of CE transformation, a journey that requires continuous refinement and adaptation.

References

ANUB Zero. 2022. University-Related Travel Policy. Australian National University. [online] Available at: https://iceds.anu.edu.au/files/Opportunities%20for%20change%20in%20Hum an%20Resources%20and%20Travel%20policies%20at%20ANU.pdf

Arora, R., Mutz, D., and Mohanraj, P., 2023. Innovating for the Circular Economy: Driving Sustainable Transformation. London: CRC Press. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781003201816

Bernecker, T., Bradshaw, B.E., Feitz, A.J., and Daley, C., 2022. Evaluating Australia’s energy commodity resources potential for a net-zero emission future. The APPEA Journal, 62(1), S555-S561 https://doi.org/10.1071/AJ21091

Brendzel-Skowera, K., 2021. Circular economy business models in the SME sector. Sustainability, 13(13), 7059. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137059

Cahill, A., 2021. What Regions Need on the Path to Net Zero Emissions. [online] Available at: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5da6541d517c244e83b79581/t/6279d0429d35666087412984/1652150346473/What+Regions+Need+Report+-+Full+May22.pdf

Dieleman, H., and Martínez-Rodríguez, M.C., 2019. Potentials and Challenges for a Circular Economy in Mexico. In: M.L. Franco-García, J. Carpio-Aguilar, H. Bressers, ed. Towards Zero Waste. Greening of Industry Networks Studies, vol 6. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92931-6_2

Feldman, R., and Sanger, J., 2007. The text mining handbook: advanced approaches in analyzing unstructured data. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511546914

Fleischmann, K., 2019. Design-led innovation and Circular Economy practices in regional Queensland. Local Economy, 34(3), 245–262. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269094219854679

Gudivada, V.N., Rao, D. and Raghavan, V.V., 2015. Big data driven natural language processing research and applications. In Handbook of statistics (Vol. 33, pp. 203-238). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-63492-4.00009-5

Halog, A., Balanay, R., Anieke, S., and Yu, T.Y., 2021. Circular economy across Australia: Taking stock of progress and lessons. Circular Economy and Sustainability, 1(1), pp.283-301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43615-021-00020-5

Halog, A. and Anieke, S., 2021. A review of circular economy studies in developed countries and its potential adoption in developing countries. Circular Economy and Sustainability, 1(1), pp.209-230. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43615-021-00017-0

Hassani, H., Beneki, C., Unger, S., Mazinani, M.T., and Silva, E.S., 2020. Text mining in big data analytics. Big Data and Cognitive Computing, 4(1), 1; https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc4010001

Howard, M.B., Boehm, S., Eatherley, D., Lobley, M., and Winter, M., 2018. A capability maturity model for the circular economy: An agri-food perspective. DOI: http://hdl.handle.net/10871/37455

Hull, A., 2023. A view from net zero. ANZCA Bulletin, 32(1), 60-63.

Ignatow, G., and Mihalcea, R., 2016. Text mining: A guidebook for the social sciences. London: Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483399782

James, P., Mellick Lopes, A., Martín-Valdéz, S., Partoredjo, S., Salazar, J. F., and Zhong, F., 2019. Closing the Loop on Waste: Community Engagement, Cultural Diversity, and Shared Responsibilities in Waste Management in Canterbury-Bankstown. Penrith: Institute for Culture and Society. Sydney: Western Sydney University.

Jim, J.R., Talukder, M.A.R., Malakar, P., Kabir, M.M., Nur, K. and Mridha, M.F., 2024. Recent advancements and challenges of NLP-based sentiment analysis: A state-of-the-art review. Natural Language Processing Journal, p.100059. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nlp.2024.100059

Khan, W., Daud, A., Khan, K., Muhammad, S. and Haq, R., 2023. Exploring the frontiers of deep learning and natural language processing: A comprehensive overview of key challenges and emerging trends. Natural Language Processing Journal, 4, p.100026. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nlp.2023.100026

Lèbre, É., Corder, G., and Golev, A., 2017. The role of the mining industry in a circular economy: a framework for resource management at the mine site level. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 21(3), 662-672. https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.12596

Martin, J.H., and Jurafsky, D., 2009. Speech and language processing: An introduction to natural language processing, computational linguistics, and speech recognition (Vol. 23). Upper Saddle River: Pearson/Prentice Hall.

Massaro, M., Secinaro, S., Dal Mas, F., Brescia, V. and Calandra, D., 2021. Industry 4.0 and circular economy: An exploratory analysis of academic and practitioners’ perspectives. Business Strategy and the Environment, 30(2), pp.1213-1231. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2680

Maruyama, Ú., Sanchez, P.M., Trigo, A.G.M., and Motta, W.H., 2019. Circular Economy in higher education ınstitutions: lessons learned from Brazıl-Colombıa network. Brazilian Journal of Operations & Production Management, 16(1), 88-95. https://doi.org/10.14488/BJOPM.2019.v16.n1.a8

Miemczyk, J., Carbone, V. and Howard, M., 2022. Learning to Implement the Circular Economy in the Agri-food Sector: A Multilevel Perspective, In: L. Bals, W.L. Tate, and L.M. Ellram, ed. Circular Economy Supply Chains: From Chains to Systems, Emerald Publishing Limited, Bingley, pp. 283-301. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-83982-544-620221014

Moghayedi, A., Awuzie, B., Omotayo, T., Le Jeune, K., Massyn, M., Ekpo, C.O. and Ndubuka-McCallum, N., 2021. A critical success factor framework for implementing sustainable innovative and affordable housing: a systematic review and bibliometric analysis. Buildings, 11(8), 317. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings11080317

Ogunmakinde, O.E., Egbelakin, T., and Sher, W., 2022. Contributions of the circular economy to the UN sustainable development goals through sustainable construction. Resources, Conservation and Recycling. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.106023

Oke, A., Osobajo, O., Obi, L., and Omotayo, T., 2021. Rethinking and optimising post-consumer packaging waste: A sentiment analysis of consumers’ perceptions towards the introduction of a deposit refund scheme in Scotland. Waste management, 118, 463-470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2020.09.008

O’Mara-Eves, A., Thomas, J., McNaught, J., Miwa, M., and Ananiadou, S., 2015. Using text mining for study identification in systematic reviews: a systematic review of current approaches. Systematic reviews, 4(1), 5. DOI https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-5

Osobajo, O.A., Oke, A., Omotayo, T., and Obi, L.I., 2022. A systematic review of circular economy research in the construction industry. Smart and Sustainable Built Environment, 11(1), 39-64. https://doi.org/10.1108/SASBE-04-2020-0034

Omotayo, T.S., Boateng, P., Osobajo, O., Oke, A., and Obi, L.I., 2020. Systems thinking and CMM for continuous improvement in the construction industry. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 69(2), 271-296. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPPM-11-2018-0417

Omotayo, T., and Kulatunga, U., 2017. A continuous improvement framework using IDEF0 for post-contract cost control. Journal of Construction Project Management and Innovation. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC-8506b6f28

Pantel, P., and Lin, D., 2002. Discovering word senses from text. In Proceedings of the eighth ACM SIGKDD international conference on Knowledge discovery and data mining (pp. 613-619). https://doi.org/10.1145/775047.775138

Parashar, D., 2023. The Impact of Net-Zero Emissions Target Announcements on Listed Organisations’ Share Price (Doctoral dissertation, Macquarie University).

Prasad, D., Kuru, A., Oldfield, P., Ding, L., Dave, M., Noller, C., and He, B., 2023. Policy Pathways to a Net Zero Carbon-Built Environment. In Delivering on the Climate Emergency: Towards a Net Zero Carbon Built Environment (pp. 201-233). Singapore: Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-6371-1_6

Rocca, L., Veneziani, M., and Carini, C., 2023. Mapping the diffusion of circular economy good practices: Success factors and sustainable challenges. Business Strategy and the Environment. Wiley Online Library. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3235

Roche, D., Langham, E., Mouritz, M., Breadsell, J., Sharp, D., Nagrath, K., White, S., McCartney, D., Prendergast, J., Parida, S. Bona, R., Kinstan, K., and Jazbec, M., 2022. The Green Wave. Adding value through net zero energy strategies. RACE for 2030 CRC.

Serrano-Bedia, A.M., and Perez-Perez, M., 2022. Transition towards a circular economy: A review of the role of higher education as a key supporting stakeholder in Web of Science. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 29, 372-385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2022.02.001

Shooshtarian, S., Hosseini, M.R., Kocaturk, T., Arnel, T. and T. Garofano, N., 2023. Circular economy in the Australian AEC industry: investigation of barriers and enablers. Building Research & Information, 51(1), pp.56-68. https://doi.org/10.1080/09613218.2022.2099788

Shooshtarian, S., Maqsood, T., Caldera, S. and Ryley, T., 2022. Transformation towards a circular economy in the Australian construction and demolition waste management system. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 30, pp.89–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2021.11.032

Study Australia. 2023. List of Australian Universities. [online] Available at: https://www.studyinaustralia.gov.au/english/australian-education/universities-and-higher-education/list-of-australian-universities

Venkatachalam, V., Pohler, M., Spierling, S., Nickel, L., Barner, L. and Endres, H.J., 2022. Design for recycling strategies based on the life cycle assessment and end of life options of plastics in a circular economy. Macromolecular Chemistry and Physics, 223(13), p.2200046. https://doi.org/10.1002/macp.202200046

Wang, Y., Peng, S., Assogba, K., Liu, Y., Wang, H., Xu, M. and Wang, Y., 2018. Implementation of cooperation for recycling vehicle routing optimization in two-echelon reverse logistics networks. Sustainability, 10(5), p.1358. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10051358

Appendix

Appendix A: Text mining R-Studio script for circular economy strategies