Construction Economics and Building

Vol. 25, No. 2

July 2025

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Study on the Awareness and Practice of Circular Economy Principles Among Construction Stakeholders in Nigeria

Ayodeji Emmanuel Oke1, Oladoyin Abidemi Akintola2,*, Oyewole Mercy Oluwatobiloba3, John Aliu4, Nicholas Ipinlaye Omoyajowo5

1 Research Group on Sustainable Infrastructure Management (RG-SIM+), Department of Quantity Surveying, Federal University of Technology Akure, Akure, Nigeria, emayok@gmail.com

2 Department of Quantity Surveying, Federal University of Technology Akure, Nigeria, akintolaoladoyin86@gmail.com

3 Department of Quantity Surveying, Federal University of Technology Akure, Nigeria, contactttobi@gmail.com

4 Institute for Resilient Infrastructure Systems, College of Engineering, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia, USA, john.o.aliu@gmail.com

5 Department of Architecture, Federal University of Technology Akure, Nigeria, arcnicholas112@yahoo.com

Corresponding author: Oladoyin Abidemi Akintola, akintolaoladoyin86@gmail.com

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v25i2.9126

Article History: Received 28/04/2024; Revised 19/07/2024; Accepted 17/03/2025; Published 08/08/2025

Citation: Oke, A. E. Akintola, O. A., Oluwatobiloba, O. M., Aliu, J., Omoyajowo, N. I. 2025. Study on the Awareness and Practice of Circular Economy Principles Among Construction Stakeholders in Nigeria. Construction Economics and Building, 25:2, 24–42. https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v25i2.9126

Abstract

The Nigerian construction industry, characterized by a linear economic model and being a major contributor to waste generation, is slow in the adoption of methods that could be beneficial in sustainable waste disposal techniques. Despite the known benefits of circular economy principles (CEPs), the awareness level and usage of circular economy are still considered to be below average. This study aims to analyze the level of awareness and usage of CE principles among Nigerian construction stakeholders. It adopts a quantitative research method by using closed-ended questionnaires distributed to construction professionals in Lagos State, Nigeria. Data were analyzed using frequency distribution for the proportion of responses and characteristics of the respondents and mean item score, standard deviation, and factor analysis for the objectives. Additionally, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was used to indicate that the retrieved data were sufficient for factor analysis, while Bartlett’s test of sphericity (BTS) tested the significance of the correlations between the variables. The findings of the study indicate that construction professionals have only a basic knowledge of CEPs and their importance in practice, but they are very familiar with their application. Thus, it provides the basis for which construction stakeholders, policymakers, and the government can make informed decisions to improve the awareness and usage of CEPs in the construction industry. The study’s findings highlight the knowledge gap and the need for targeted educational and training initiatives, which can serve as a basis for future research and intervention programs.

Keywords

Circular Economy Principles; Environmental Impact; Resilient Construction; Sustainable Waste Disposal; Circular Trainings

Introduction

Circular economy (CE) has become an increasingly prevalent concept globally, especially given its potential to address challenges related to sustainability. The concept, which has garnered attention from various schools of thought, has piqued the interest of countries, including several developed nations (Zuofa, et al., 2023). An assessment by the European Commission revealed that adopting a CE in its manufacturing sector could result in over 500 billion euros in economic gains annually for the continent (Osei-Tutu, et al., 2023). This shift would entail moving away from the long-standing linear method involving extraction, production, usage, anddisposal, as the depletion of raw materials has made the linear approach unsustainable, prompting a return to the CE model (Akinwale, 2023). Since the emergence of CE concepts, numerous definitions have been proposed, sharing broadly similar principles across different schools of thought. Geng and Doberstein (2008) associated CE with the industrial ecology school of thought, suggesting that economic growth and environmental sustainability can coexist. The cradle-to-cradle school of thought more effectively encapsulates the idea of a CE. This perspective posits that everything in nature should undergo a waste revolution, with waste from one organism serving as a valuable resource for another (Kekic, et al., 2020).

Typically, a CE system adopts a cyclic approach to manufacturing and production, where by-products are treated as raw materials for subsequent processes. The term first appeared in a 1990 study by Pearce and Turner, examining the interplay between the environment and economic activities (Donaghy, 2022). This system, according to the authors, is based on the premise that everything is interconnected. The principle was previously cited in the work of Akinwale (2023), highlighting the concept of a closed system and emphasizing the finite natural resources available for human activities. While China’s CE Promotion Law defines a CE as the “activity of reducing, reusing, and recycling in production, circulation, and consumption” European institutions describe it as “an economy where the value of products, materials, and resources is maintained for as long as possible and waste generation is minimized” (Merli, et al., 2018). However, the CE has attracted the attention not only of nations but also of non-governmental organizations focusing on climate change and sustainability. For instance, the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, established in the United Kingdom in 2010, defines it as an industrial system that is restorative or regenerative by intention and design, emphasizing the replacement and replenishment of end-of-life products and a shift toward renewable energy use (Mhatre, et al., 2021). Upadhayay, et al. (2024) further explore the Ellen MacArthur definition, describing the CE as involving the elimination of waste through superior material, product, and system design, including innovative business models.

In recent times, the Nigerian government has established several initiatives such as Circular Lagos, whose aim is to cultivate a more sustainable and resource-efficient economy by promoting circular business practices (Adelekan, 2022). Additionally, the Nigeria Circular Economy Working Group (NCEWG) has been formed to develop a national framework for a CE throughout the nation. According to Ayanrinde and Mahachi (2023), the NCEWG brings together stakeholders from government, business, academia, and civil society to design policies and programs that promote resource efficiency and minimize waste across the entire country. Also, the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) is working with the Nigerian government on various projects that support the country’s transition to a CE (Paul and Ofuebe, 2021). Private sector companies and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) are also driving circularity. For instance, the Coca-Cola Foundation’s initiatives focus on areas like plastic waste management, which aligns perfectly with the CE’s goal of keeping materials in use for longer (Adelekan, 2022). Despite increasing attention to sustainability initiatives, debates continue regarding the actual implementation of CE principles due to several challenges such as lack of knowledge, lack of standardization and regulation, consumer behavior, and hesitance to new ideas (Albert and Olutayo, 2021; Ezeudu et al., 2021; Akinwale, 2023). These challenges are particularly relevant in the construction industry, a significant contributor to solid waste generation in Nigeria. To be able to implement these practices and create a more sustainable construction sector, there is a need to understand if construction professionals are even familiar with CE principles. Thus, this paper aims to shed light on the level of familiarity and adoption of CE principles within Nigeria’s construction sector. The findings of this study can inform the development of targeted interventions and educational programs to bridge any knowledge gaps and encourage the integration of CE practices throughout the construction industry.

Overview of circular economy principles

CE adheres to a set of well-defined guiding principles that encompass a range of methods for achieving circularity. In their work, Schöggl, et al. (2020) identified a comprehensive suite of nine such principles, which include actions like re-use, recycle, recover, repair, remanufacture, refurbish, refuse, reduce, and repurpose. Subsequent research by Osei-Tutu, et al. (2022) and Lee, et al. (2023) has further expanded this framework by introducing additional strategies such as rethink, recirculate, and regenerate as essential components of CE practices.

Recycle

Demolition is an intrinsic element of the built environment, closely paralleling the significance of construction itself. It may arise from alterations in building design, necessitating the partial removal of existing structures to accommodate new construction, or from the complete removal of a building to erect an entirely new structure (Ghaffar, et al., 2020). Following the demolition process, a substantial amount of waste is generated on-site, requiring removal and disposal. According to Zhang, et al. (2022), waste generation is estimated to exceed 1,000 m3 for every 13,500 m2 of built surface. This equates to approximately 0.07 m3 of waste produced per square meter of built surface. This extensive waste generation within the construction industry contributes significantly to the sustainability issues previously mentioned in this research. One notable concern is the environmental impact associated with improper waste disposal, which can lead to ecological degradation and health hazards. Akinwale (2023) recommended recycling as a superior waste management technique. This process not only facilitates responsible disposal but also involves re-engineering potentially harmful waste into new materials that can find applications in various sectors, including construction.

Re-use

Minunno, et al. (2020) identified that the concepts of recycling and re-use are often used interchangeably due to a research gap that has failed to differentiate between these two CE principles. Unlike recycling, where used materials are repurposed, the re-use technique involves keeping already-used materials for the same purpose for which they were manufactured (Kopsidas and Giakoumatos, 2021). This means that the intended use remains consistent for both the original and re-used materials. In recycling, new products may differ from the original, but this is not the case with re-use. While some argue that re-use as a CE principle is challenging in construction due to the disposable nature of buildings at the end of their life cycle, Upadhayay, et al. (2024) contended that resources within the construction framework should be explored for re-use opportunities. Based on a case study of mixed-use construction, Minunno, et al. (2020) also argued that it is possible to incorporate over 80% of re-used materials in construction. This not only enhances sustainability in construction but also makes construction more cost-effective.

Refurbish

Bilal, et al. (2020) identified refurbishment as a key principle of CE that plays a crucial role in optimizing the lifespan and value of buildings. This approach leads to reduced resource usage by maximizing the utilization of existing structures, aligning with the principles of sustainability and the CE (Minunno, et al., 2020). Unlike conventional practices, which often involve the complete reconstruction of buildings, refurbishment prioritizes the retention and improvement of the existing framework (González, et al., 2021). This means that refurbishing allows for the enhancement or upgrading of existing structures without the need to demolish the entire building. Choosing refurbishment over new construction not only conserves resources but also minimizes the environmental impact associated with resource extraction and production (Bilal, et al., 2020). By extending the life of existing buildings through refurbishment, the demand for new construction materials is reduced, further contributing to sustainable practices and CE principles.

Remanufacture

Beyond buildings, the remanufacturing of construction equipment has also been recognized as a sustainable practice. As construction projects increase, so does the demand for equipment, and the production of new equipment can contribute to sustainability concerns. Charef, et al. (2022) argued that remanufacturing these pieces of equipment offers numerous opportunities, including cost-effective machines and reduced resource and energy consumption. Among the various strategies (R-strategies) in CE, Singhal, et al. (2020) indicated that remanufacturing stands out, as it ensures the quality of remanufactured products matches that of new ones. At the end of a product’s life or its intended use, remanufactured items are not only restored to their original state but also often improved upon, underscoring their role in sustainable and quality-centric practices within the CE paradigm (Minunno, et al., 2020). Talamo, et al. (2021) advocated for facility managers as the gatekeepers of remanufacturing in construction due to their primary responsibility for monitoring and managing buildings. While remanufacturing has yet to extend to entire buildings, it already applies to building components like furniture (Singhal, et al., 2020). Thus, manufacturers must collaborate closely with real estate operators to develop products that can be easily retrieved at their end-of-life for remanufacturing, emphasizing the importance of a coordinated approach to circularity in construction.

Repurpose

Morseletto (2020) defined repurposing as a CE principle involving the utilization of abandoned products or their parts to create a new product with a different function. Repurposing has gained increasing popularity as a strategic response to the growing prevalence of abandoned buildings that no longer serve their original purposes. This approach offers a flexible solution by allowing the transformation of unused buildings into various types of spaces for single or multipurpose use (Bertino, et al., 2021). The significance of repurposing lies in its potential to reduce the demand for raw materials in new construction, thereby contributing to sustainability. Furthermore, repurposing extends the life of existing buildings, aligning with principles that prioritize resource efficiency and environmental conservation (OECD, 2023).

Repair

Morseletto (2020) also provided a definition of repair, framing it as the process of addressing defects or malfunctions in products to restore their functionality for their intended purposes. This definition positions repair as a gentle or subtle type of maintenance. Güsser-Fachbach, et al. (2023) acknowledged repair as a viable method for prolonging the lifespan of products and materials. This involves not only fixing issues but also designing products for durability, underscoring the significance of incorporating maintenance and repair practices to maximize usability.

Recover

To facilitate the transition toward a CE, Ruiz, et al. (2020) advocated for the implementation of various strategies, one of which involves the establishment of recovery schemes. In this context, a recovery scheme signifies the systematic retrieval and reintroduction of materials back into the manufacturing industry. Joustra, et al. (2022) posited that the initiation of robust material recovery mechanisms begins at the inception of product design, incorporating strategies for multiple lifecycles and prospective recovery activities. This argument emphasizes that successful recovery efforts also depend on user incentives, necessitating a proactive approach that involves stakeholder analysis and active participation. This perspective underscores the importance of integrating recovery considerations into the earliest phases of product development and advocates for a comprehensive understanding of user motivations to foster effective engagement in recovery practices.

Regenerate

Regeneration has gained significant recognition within the biological context for decades, where the reclamation and restoration of materials, coupled with nutrient regeneration, are key principles. The principle of regeneration also gains relevance within the construction context (Gillott, et al., 2023). Concrete stands out as a key regenerative material in construction, known for its intrinsic self-healing function and renewing mechanism. This inherent quality allows concrete to repair cracks and minor damages over time, extending its lifespan and reducing maintenance needs (Ogunmakinde et al., 2019). The advancements in concrete technology have further enhanced these regenerative properties, leading to the development of self-healing concrete. This innovative approach not only reinforces the fundamental notion of concrete regeneration but also aligns with the principles of a CE by emphasizing sustainable material utilization and promoting regenerative processes within the construction industry.

Recirculate

Recirculation has gained prominence in discussions surrounding sustainable practices and waste reduction. As a principle of the CE, O’Grady, et al. (2021) described recirculation as the process of returning material resources to manufacturing companies for new product development, with waste management playing a key role in facilitating this process. Similarly, Lekan, et al. (2021) defined recirculation as the act of extracting and retaining maximum value from existing resources through diverse circuits of value in local production. Although both definitions vary slightly, they both emphasize effective waste management practices as a driver for recirculation. While O’Grady, et al. (2021) emphasized the need for materials to be reintroduced into the manufacturing sector, Lekan, et al. (2021) suggested that recirculation is not solely about minimizing waste but also about optimizing the utility and value derived from resources within local economies. This broader perspective highlights the importance of integrating recirculation strategies into sustainable practices to maximize resource efficiency and economic benefits.

Refuse

Grigoropoulos, et al. (2022) identified 10 R-strategies aimed at reducing society’s reliance on raw materials and minimizing the environmental impact associated with extracting them. One of these R-strategies, identified as “refuse,” refers to making a product redundant by either abandoning its function or offering the same function with a radically different product. The concept of refuse can also extend to the deliberate avoidance or reduction of certain materials or production processes to promote a more CE (Morseletto, 2020). By choosing to refuse certain products or materials, businesses and consumers can contribute to reducing waste and conserving resources, aligning with the principles of sustainability and circularity.

Rethink

Lekan, et al. (2021) explained the principle of “rethink” as the strategic transformation of a product aimed at enhancing its use intensity. This transformative process includes implementing various mechanisms, such as promoting product-sharing initiatives and introducing multifunctional products to the market. By adopting these strategic approaches, products can be effectively repositioned to unlock their optimal usage potential (Morseletto, 2020). The concept of “rethink” not only aligns with present-day sustainability practices but also underscores the role of innovative strategies in extending a product’s lifespan and maximizing its overall impact. This perspective advocates for a departure from conventional product consumption models toward more sustainable and resource-efficient alternatives. Furthermore, O’Grady, et al. (2021) emphasized the need for a broader reconceptualization of both production and usage. To make anything more circular, there is a foundational need for a rethinking process. “Rethinking” includes dematerialization, which involves substituting a product with a non-material alternative that provides the same utility for users. This aspect of dematerialization is identified as an integral component of the CE, emphasizing the need for a comprehensive rethink to achieve more sustainable and circular product lifecycles (Morseletto, 2020).

Reduce

Estarrona, et al. (2019) underscored the fundamental significance of the “reduce” principle within the context of sustainable manufacturing and the CE. It emphasizes the imperative of minimizing both material and energy consumption, not solely for immediate profitability but also to enhance the enduring viability of assets. The argument posits that assets formulated with a focus on longevity, in conjunction with diminished resource usage, yield sustained profitability over an extended temporal horizon. In pursuit of this objective, due consideration must be accorded to maintenance policies (Ogunmakinde, et al., 2019). The premise is that for assets to endure protracted periods with minimal energy and material consumption, the implementation of effective maintenance strategies becomes critical (Ogunmakinde, et al., 2019). Table 1 presents a summary of the discussed CE principles.

| S/N | Variables | Authors |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Recycle | Ghaffar, et al. (2020), Zhang, et al. (2022) |

| 2 | Repair | Morseletto (2020), Güsser-Fachbach, et al. (2023) |

| 3 | Refurbish | Bilal, et al. (2020), González, et al. (2021) |

| 4 | Remanufacture | Singhal, et al. (2020), Talamo, et al. (2021) |

| 5 | Repurpose | Morseletto (2020), OECD (2023) |

| 6 | Refuse | Grigoropoulos, et al. (2022), Morseletto (2020) |

| 7 | Rethink | Lekan, et al. (2021), O’Grady, et al. (2021) |

| 8 | Reduce | Estarrona, et al. (2019) |

| 9 | Re-use | Kopsidas and Giakoumatos (2021), Upadhayay, et al. (2024) |

| 10 | Recover | Joustra, et al. (2022) |

| 11 | Regenerate | Ogunmakinde, et al. (2019), Gillott, et al. (2023) |

| 12 | Recirculate | Lekan, et al. (2021) |

Research methodology

CE principles propose moving the construction industry from a system of “make and waste” to a system of reliable waste management techniques, where all construction materials are reconsidered as raw materials after use (Papamichael et al., 2023). Throughout this study, the principles of the CE are discussed and used to analyze the level of awareness and usage of the CE within the Nigerian construction industry. To do this, the article employed a quantitative research method using well-structured questionnaires administered to a population of 372 construction professionals, including architects, builders, quantity surveyors, civil engineers, mechanical engineers, and electrical engineers in Lagos State. Questionnaire surveys were chosen for data collection due to their effectiveness in examining human perceptions and feelings toward specific concepts (Ranganathan and Caduff, 2023). In this study, the respondents’ perceptions of the level of awareness and usage of the CE were analyzed.

A convenience sampling technique was used, and 372 respondents were selected, of which only 98 returned data, serving as the basis for the findings of this paper. According to Golzar and Tajik (2022), convenience sampling is a non-probabilistic sampling technique where respondents are selected based on convenience. This typically involves collecting data from construction respondents who are easily accessible, making data collection faster and with fewer implications. The distributed questionnaires used closed-ended questions, with respondents selecting options from a 5-point Likert scale: “very high” = 5, “high” = 4, “average” = 3, “low” = 2, and “very low” = 1. For data analysis, the electronic method of the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) was employed. This included using statistical techniques such as frequency distribution to determine the proportion of responses from the respondents, mean item score, standard deviation, and factor analysis to achieve the main objective of the paper, which is to assess the level of awareness and use of the CE in the Nigerian construction sector.

Results

Background information of respondents

This section presents the characteristics of the respondents who participated in this research. Out of 372 questionnaires distributed to construction professionals, including architects, builders, quantity surveyors, and engineers, 26% were returned, while 74% were not retrieved. This indicates that the number of retrieved questionnaires was sufficient for the analysis of results for this paper. Table 2 shows the frequency and percentage of professionals whose data were used in this study, along with their professional qualifications, academic qualifications, and years of professional experience. Data were collected from 44.9% of quantity surveyors, 18.4% of architects, 12.2% of engineers, and 24.5% of builders. All respondents were duly certified by their respective professional bodies at the time of the research, including Quantity Surveyors Registration Board of Nigeria (QSRBN) (44.8%), Architects Registration Council of Nigeria (ARCON) (18.4%), Council for the Regulation of Engineering in Nigeria (COREN) (12.2%), and Council of Registered Builders of Nigeria (CORBON) (24.5%). The analysis of respondent characteristics also reveals that the majority (63.3%) held a bachelor’s degree, followed by master’s degree holders at 22.4% and PhD holders at 5.1%, with HND holders making up the smallest portion at 9.2% of the population of data collected through questionnaires. Table 2 further indicates that most professionals have less than 5 years of experience, with a frequency of 61 (62.2%). Professionals with 6 to 10 years of experience closely follow with a frequency of 25 (25.5%), those with 11 to 15 years have a frequency of 8 (8.2%), and those with 15 to 20 and over 21 years of experience account for 3 (3.1%) and 1 (1%), respectively. It is therefore sufficient to say that the majority of the professionals had adequate knowledge to respond to questions from this study judging from their academic qualifications, professional qualifications, and years of experience in their different professions.

NB: ARCON, Architects Registration Council of Nigeria; CORBON, Council of Registered Builders of Nigeria; QSRBN, Quantity Surveyors Registration Board of Nigeria; COREN, Council for the Regulation of Engineering in Nigeria.

Awareness of circular economy principles in building projects

Table 3 presents the awareness of CE principles among respondents. The table shows that 78.60% of the respondents are aware of circular construction principles, 8.20% are not aware, and 13.30% are uncertain (maybe). In terms of participation, Table 4 indicates that 41.80% of the respondents adopt these principles, 44.90% do not, and 13.30% are uncertain (maybe).

| S/N | Circular construction principles awareness | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yes | 77 | 78.60% |

| 2 | No | 8 | 8.20% |

| 3 | Maybe | 13 | 13.30% |

| Total | 98 | 100 |

| S/N | Circular construction principles | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yes | 41 | 41.80% |

| 2 | No | 44 | 44.90% |

| 3 | Maybe | 13 | 12.30% |

| Total | 98 | 100% |

The data from Table 5 reveal significant differences in the awareness of CE principles among architects, builders, quantity surveyors, and engineers. One of the notable findings is the strong awareness of “recycle” and “re-use” principles across all professions. Architects stand out in “re-use” with a mean score of 4.17, indicating their focus on sustainable design practices. This indicates that architects prioritize incorporating recycled and reclaimed materials into their designs, aiming to reduce waste and promote sustainability. This emphasis on “re-use” aligns with the findings of Minunno et al. (2020), which highlighted the growing importance of sustainable design strategies in modern architectural practices. However, there are clear gaps in awareness, particularly in areas like refurbish and reduce. Builders’ low score of 3.21 in “refurbish” suggests a possible lack of emphasis on renovation and re-use of building materials. This implies that builders may be more inclined toward new construction rather than refurbishing existing structures or using reclaimed materials, potentially missing out on opportunities to reduce waste and conserve resources. This observation aligns with the study of González, et al. (2021), which emphasized the importance of incorporating refurbishment and re-use strategies to promote sustainability in the construction industry. Quantity surveyors consistently demonstrate high awareness across multiple principles, such as “repair,” “recycle,” and “re-use,” possibly due to their role in project costing and material management. Their involvement in tracking and managing project budgets necessitates a deep understanding of material life cycles, costs, and the value of sustainable practices (Agyekum, et al., 2023). This comprehensive awareness enables them to make informed decisions that prioritize sustainability and cost-efficiency, aligning with the findings of the study by Zulu, et al. (2023), which highlighted the pivotal role of quantity surveyors in driving sustainable practices within the construction industry. However, engineers show a balanced awareness across principles, with “repair” being their strongest area, likely reflecting their problem-solving approach to design and construction challenges. Engineers’ proficiency in repair underscores their ability to address and rectify structural and functional issues, showcasing their technical expertise and adaptability. This finding aligns with the study by Morseletto (2020), which emphasized the engineers’ pivotal role in implementing innovative and sustainable solutions in the construction industry.

NB: SD, standard deviation.

Awareness of circular economy principles in building projects

Based on findings from Table 6, architects demonstrate the highest awareness in “refurbish” with a mean score of 3.89, highlighting their interest in sustainable renovation and re-use practices. This suggests that architects are more inclined toward designing buildings that can be refurbished or repurposed, aligning with the principles of sustainable architecture. The study by Boarin and Martinez-Molina (2022) supports this, emphasizing the architects’ role in promoting refurbishment and re-use in the construction industry. Builders and engineers tie for the highest awareness in “re-use” with a mean score of 3.66 and 4.00, respectively. This indicates a shared emphasis on using reclaimed materials and promoting sustainable construction practices. The builders’ focus on re-use may be due to cost-saving benefits and the engineers’ emphasis on technical feasibility, aligning with the findings of González, et al. (2021), which highlighted the importance of re-use in sustainable construction. Quantity surveyors lead in “repair” with a mean score of 3.45, reflecting their role in project costing and maintenance planning. Their awareness of repair signifies the importance of lifecycle costing and maintenance in sustainable construction practices. This aligns with the study by Minunno, et al. (2020), emphasizing the quantity surveyors’ role in promoting lifecycle thinking and maintenance in the construction industry. In contrast, “recycle” awareness is relatively low across all professions, with quantity surveyors having the highest mean score of 3.09. This suggests a potential gap in understanding the value of recycling in construction materials and processes. The study by Boarin and Martinez-Molina (2022) highlighted the need for increased awareness and implementation of recycling practices in the construction industry to promote sustainability.

NB: SD, standard deviation.

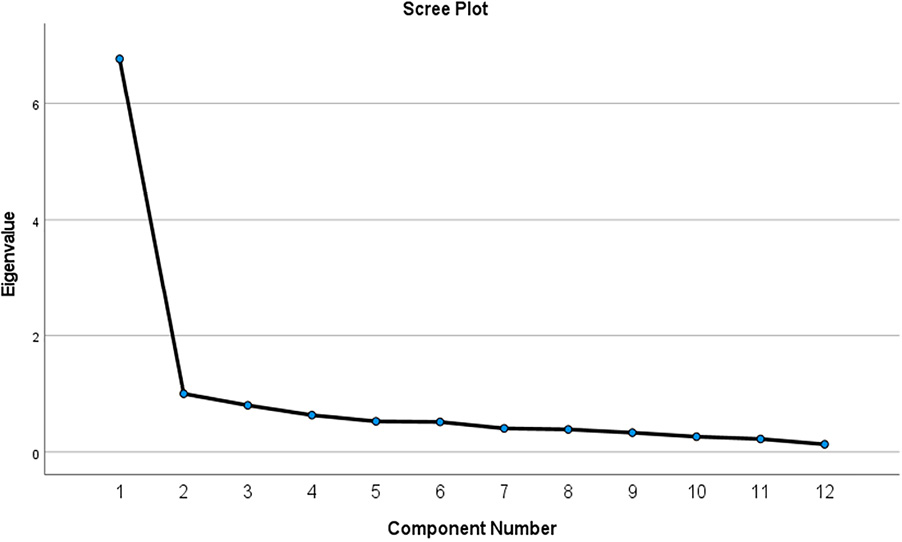

Exploratory factor analysis

Table 7 presents the findings from the factor analysis conducted. With a Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of 0.898, the data’s sampling adequacy was confirmed, making it suitable for factor analysis (Hair, et al., 2019). Bartlett’s test of sphericity, significant at 0.000, further underscored the robustness of the data’s correlations. Initial eigenvalues point to two primary components: the primary component, with an eigenvalue of 6.781 representing 56.51% of the variance, comprises CE practices like “recycle,” “repair,” “re-use,” “refurbish,” “recover,” “remanufacture,” and “repurpose.” The secondary component, with an eigenvalue of 1.000 explaining 8.337% of the variance, includes practices such as “rethink,” “refuse,” “recirculate,” “regenerate,” and “reduce”. Both components combined explain 64.846% of the total variance. The rotated component matrix reveals strong correlations with high loadings above 0.7 for the primary component and significant loadings for the secondary component. Utilizing Varimax with Kaiser Normalization, the rotation converged in 10 iterations. Inspection of the scree plot in Figure 1 revealed a clear break after the second component. The point where the slope of the curve is clearly leveling off indicates the number of factors that should be generated by the analysis.

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy | 0.898 |

| Bartlett’s test of sphericity | — |

| Df | 66 |

| Approximate chi-square | 726.25 |

| Significance | 0.000 |

Extraction method: principal component analysis.

Rotation method: Varimax with Kaiser Normalization.

a. Rotation converged in 10 iterations.

Figure 1. Scree plot of the various circular economy principles.

Source: Figure created by the author

Discussion

The objective of this study is to assess the awareness and usage of circular construction principles among construction professionals involved in Nigerian building projects. A significant majority of these professionals demonstrated awareness and knowledge of circular construction, as shown in Table 5. Notably, all the circular construction principles assessed had mean values above 3.0 on a 5-point Likert scale. These results indicate that construction professionals in Nigeria are well-acquainted with circular construction principles. Moreover, this familiarity suggests a positive trend toward integrating sustainable and circular practices within the Nigerian construction industry. This generally aligns with the studies of Paul and Ofuebe (2021) and Zuofa, et al. (2023), which suggested that construction professionals in the nation are increasingly recognizing the importance of sustainable construction methods. This awareness and acceptance are crucial steps toward achieving a more environmentally friendly and resource-efficient construction industry in Nigeria (Ogunmakinde, et al., 2019). However, despite a high awareness rate of 78.60%, only 41.80% of professionals are actively involved in the practice of these principles. This discrepancy may be attributed to the emerging nature of CE practices in the construction industry, as well as to challenges related to implementation, such as lack of clear guidelines, limited availability of materials, and higher initial costs associated with sustainable construction methods (Bilal, et al., 2020; Ezeudu, et al., 2021; Osei-Tutu, et al., 2023; Zulu, et al., 2023). Additionally, the gap between awareness and practice could also reflect a need for more extensive training and capacity-building initiatives tailored to circular construction principles. As the industry continues to evolve and as more case studies become available, it is anticipated that the gap between awareness and implementation will narrow, paving the way for broader adoption of circular practices in construction projects.

Nevertheless, the top three circular construction principles utilized by construction professionals are “re-use,” “recycle,” and “repair,” as shown in Table 6. This finding aligns with the previous studies of John, et al. (2023) and Otasowie, et al. (2024), which suggested that these principles are among the most accessible and straightforward to implement. The emphasis on these principles can be attributed to their immediate benefits and the lower barriers to adoption compared to other circular construction practices (John, et al., 2023). Ezeudu, et al. (2021) highlighted the economic advantages of “re-use,” “recycle,” and “repair,” emphasizing cost savings and resource efficiency. Osei-Tutu, et al. (2023) further reinforced these findings by noting the environmental benefits associated with these practices, such as reduced waste and carbon emissions. The widespread adoption of these three principles emphasizes their importance as foundational elements of circular construction. However, it also points to a potential gap in the industry’s adoption of more advanced circular practices. As the industry continues to evolve, there is a need to expand the focus beyond these foundational principles to include other aspects of the CE, such as remanufacturing, repurposing, and regenerative design (Kekic, et al., 2020). The industry’s focus on these core principles underscores the need for targeted interventions to promote a broader understanding and application of the full range of circular construction principles. It also highlights an opportunity for training programs, resource development, and policy initiatives that can address the barriers to implementing a wider variety of CE in the Nigerian construction sector.

The first classification in the rotated component matrix, labeled as the primary component, encompasses a range of principles such as “recycle,” “repair,” “re-use,” “refurbish,” “recover,” “remanufacture,” and “repurpose.” This categorization aligns with the core tenets of the CE, focusing on extending the life cycle of materials and reducing waste through various means. By grouping these principles together, the primary component highlights the interconnectedness and complementary nature of these practices in achieving sustainability goals (Morseletto, 2020). This approach to circular construction reflects a holistic view of sustainability, emphasizing not just the reduction of waste but also the efficient use of resources and the promotion of longer-lasting and durable infrastructure. The inclusion of both material recovery methods like “recycle” and “recover” alongside techniques for extending product life such as “repair” and “re-use” underscores the dynamic nature of circular construction (Joustra et al., 2022). However, the secondary component encompasses practices such as “rethink,” “refuse,” “recirculate,” “regenerate,” and “reduce.” This component focuses on more strategic and proactive approaches to sustainability within the construction industry (Talamo, et al., 2021; Charef, et al., 2022). The “rethink” and “refuse” principles encourage professionals to reconsider traditional practices and materials, questioning their sustainability and exploring alternatives (Lekan, et al., 2021). This reflects a shift toward a more conscious and intentional approach to construction, where choices are made with long-term environmental impacts in mind. The “recirculate” and “regenerate” principles emphasize the importance of creating closed-loop systems and restoring natural resources. These practices go beyond mere waste reduction to actively contribute to ecosystem restoration and resource conservation (Ogunmakinde, et al., 2019). Together, these principles in the secondary component represent a forward-thinking approach to sustainability that goes beyond conventional practices, as they highlight the industry’s potential to not only reduce its environmental footprint but also actively contribute to ecological restoration and resilience (Bertino, et al., 2021).

Implications of the study findings

The findings of this study hold critical implications for the Nigerian construction industry and broader sustainable development efforts. First, the high level of awareness among construction professionals, despite a gap in implementation, underscores the need for clear guidelines and policies on circular construction. Policymakers could use these insights to design strategies that address challenges like material availability and initial costs. Second, the discrepancy between awareness and practice highlights the importance of capacity-building initiatives tailored to circular construction principles. Such training programs could equip professionals with the necessary skills to effectively implement these practices. Additionally, the industry’s focus on foundational principles like “re-use,” “recycle,” and “repair” presents collaboration opportunities among stakeholders to foster innovation and accelerate the adoption of more advanced circular practices. Lastly, the findings contribute to existing and emerging studies on sustainability transitions, highlighting the dynamic nature of industry change and the role of multiple stakeholders in driving sustainable transitions. As the industry continues to evolve, understanding these theoretical perspectives can provide a comprehensive framework for exploring the complex factors influencing the adoption of circular construction practices and guiding future research efforts.

Limitations of the study

Despite the findings of this study, a few limitations exist. First, the study’s geographical focus on construction professionals in Lagos State limits the generalizability of the findings. If the characteristics and perspectives of respondents from Lagos differ from those in other regions, the study’s applicability may be compromised. Second, the small sample size may affect the study’s reliability, emphasizing the need for future research with a larger and more diverse sample. Another limitation is the use of convenience sampling. This approach contrasts with random sampling, which ensures a more representative sample and reduces the risk of selection bias. This methodological choice could affect the study’s validity and the generalizability of its findings. Future research may want to consider employing random sampling to improve the representativeness of the sample and enhance the validity of the findings. Furthermore, the study’s short timeframe constrained its flexibility and limited access to various research approaches. Instead of initiating the research with a pilot study to assess the feasibility of selected participants and analytical methods, the study proceeded directly. This decision may have impacted the depth and breadth of the study’s findings.

Conclusion and recommendation

This study aims to analyze the level of awareness and usage of CE principles among Nigerian construction stakeholders. This was achieved through a quantitative research method using close-ended questionnaires distributed to construction professionals in Lagos State, Nigeria. The findings of the study revealed that construction professionals have only a basic understanding of CE and their importance in practice, but they are not well-acquainted with their application. This underscores the need for ongoing education and training to bridge the gap between knowledge and application within the construction industry. Based on these findings, this study recommends several key actions to enhance the adoption and implementation of CE principles within the construction industry. First, there is a clear need for the development of training programs tailored to the specific needs of construction professionals. These programs should offer hands-on experience and practical knowledge about CE principles, ensuring that professionals not only understand the concepts but also feel confident applying them in their projects. Second, awareness campaigns targeting professionals are essential to promote the benefits and importance of CE. Workshops, seminars, and informational materials can be distributed through industry associations, educational institutions, and online platforms to reach a wider audience and raise awareness about the value of sustainable construction practices. Third, there is a need to integrate CE Principles into policies and regulations. Encouraging policymakers to incorporate CE principles into building codes, regulations, and sustainability guidelines can create a supportive regulatory environment that incentivizes the adoption of CE practices in construction projects. Finally, establishing a monitoring and evaluation framework to assess the effectiveness of interventions and track progress over time is essential. Regular monitoring and evaluation by the Nigerian government can help identify areas for improvement, measure the impact of interventions, and ensure that efforts to promote CE in the construction industry are achieving the desired outcomes. Financial support is another area where the government can make a significant impact. Providing grants, subsidies, or low-interest loans to construction companies that adopt CE practices can help offset the initial costs and incentivize more companies to embrace sustainable construction methods.

References

Adelekan, A., 2022. Circular Economy strategies of social enterprises in Lagos: a case study approach (Doctoral dissertation, Middlesex University).

Agyekum, K., Amudjie, J., Pittri, H., Dompey, A.M.A. and Botchway, E.A., 2023. Prioritizing the principles of circular economy among built environment professionals. Built Environment Project and Asset Management. https://doi.org/10.1108/BEPAM-04-2023-0077

Akinwale, Y.O., 2023. Awareness and adoption of circular economy in the consumption and production value-chain among MSMEs towards sustainable development. African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development, pp.1-10. https://doi.org/10.1080/20421338.2023.2247924

Albert, A.O. and Olutayo, F.S., 2021. Cultural dimensions of environmental problems: a critical overview of solid waste generation and management in Nigeria. American International Journal of Multidisciplinary Scientific Research, 8(1), pp.1-15. https://doi.org/10.46281/aijmsr.v8i1.1110

Ayanrinde, O. and Mahachi, J., 2023. Scenario Method for Catalysing Circularity and Lowering Emissions in the Construction Sector/Real Estate, Nigeria. In The Routledge Handbook of Catalysts for a Sustainable Circular Economy (pp. 388-402). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003267492-22

Bertino, G., Kisser, J., Zeilinger, J., Langergraber, G., Fischer, T. and Österreicher, D., 2021. Fundamentals of building deconstruction as a circular economy strategy for the reuse of construction materials. Applied sciences, 11(3), p.939. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11030939

Bilal, M., Khan, K. I. A., Thaheem, M. J., & Nasir, A. R. (2020). Current state and barriers to the circular economy in the building sector: Towards a mitigation framework. Journal of Cleaner Production, 276, 123250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123250

Boarin, P. and Martinez-Molina, A., 2022. Integration of environmental sustainability considerations within architectural programmes in higher education: A review of teaching and implementation approaches. Journal of Cleaner Production, 342, p.130989. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.130989

Charef, R., Lu, W. and Hall, D., 2022. The transition to the circular economy of the construction industry: Insights into sustainable approaches to improve the understanding. Journal of Cleaner Production, 364, p.132421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.132421

Donaghy, K.P., 2022. A circular economy model of economic growth with circular and cumulative causation and trade. Networks and Spatial Economics, 22(3), pp.461-488. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11067-022-09559-8

Estarrona, U. M. de, Seneviratne, D., Villarejo, R., & Galar, D. (2019). The New Asset Management: Implications of Servitization in Circular Economy. Journal of Industrial Engineering and Management Science, 2018(1), 109–120. https://doi.org/10.13052/jiems2446-1822.2018.006

Ezeudu, O. B., Ezeudu, T. S., Ugochukwu, U. C., Agunwamba, J. C., & Oraelosi, T. C. (2021). Enablers and barriers to implementation of circular economy in solid waste valorization: The case of urban markets in Anambra, Southeast Nigeria. Environmental and Sustainability Indicators, 12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indic.2021.100150

Geng, Y., & Doberstein, B. (2008). Developing the circular economy in China: Challenges and opportunities for achieving “leapfrog development.” International Journal of Sustainable Development and World Ecology, 15(3), pp. 231-239. https://doi.org/10.3843/SusDev.15.3:6

Ghaffar, S.H., Burman, M. and Braimah, N., 2020. Pathways to circular construction: An integrated management of construction and demolition waste for resource recovery. Journal of cleaner production, 244, p.118710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118710

Gillott, C., Mihkelson, W., Lanau, M., Cheshire, D. and Densley Tingley, D., 2023. Developing regenerate: A circular economy engagement tool for the assessment of new and existing buildings. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 27(2), pp.423-435. https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.13377

González, A., Sendra, C., Herena, A., Rosquillas, M. and Vaz, D., 2021. Methodology to assess the circularity in building construction and refurbishment activities. Resources, Conservation & Recycling Advances, 12, p.200051. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcradv.2021.200051

Grigoropoulos, C. J., Zerefos, S. C., Tsangrassoulis, A., & Doulos, L. T. (2022). Lighting products as part of the circular economy and strategies that affect it. A literature overview. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 1123(1). https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/1123/1/012006

Güsser-Fachbach, I., Lechner, G., Ramos, T. B., & Reimann, M. (2023). Repair service convenience in a circular economy: The perspective of customers and repair companies. Journal of Cleaner Production, 415(May), 137763. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.137763

Hair Jr, J.F., LDS Gabriel, M., Silva, D.D. and Braga, S., 2019. Development and validation of attitudes measurement scales: fundamental and practical aspects. RAUSP Management Journal, 54(4), pp.490-507. https://doi.org/10.1108/RAUSP-05-2019-0098

John, I.B., Adekunle, S.A. and Aigbavboa, C.O., 2023. Adoption of circular economy by construction Industry SMEs: organisational growth transition study. Sustainability, 15(7), p.5929. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15075929

Joustra, J., Bakker, C., Bessai, R., & Balkenende, R. (2022). Circular Composites by Design: Testing a Design Method in Industry. Sustainability (Switzerland), 14(13). https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137993

Kekic, A., Stojanovic Bjelic, L., & Neskovic Markic, D. (2020). Nature-Inspired Design Biomimicry and Cradle to Cradle. Quality of Life (Banja Luka) – APEIRON, 18(1-2). https://doi.org/10.7251/QOL2001058K

Kopsidas, O. N., & Giakoumatos, S. D. V. (2021). Economics of Recycling and Recovery. Natural Resources, 12(04), 73–90. https://doi.org/10.4236/nr.2021.124007

Lee, P. H., Juan, Y. K., Han, Q, and de Vries, B., 2023. An investigation on construction companies’ attitudes towards importance and adoption of circular economy strategies. Ain Shams Engineering Journal, 14(12). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asej.2023.102219

Lekan, M., Jonas, A. E. G., Deutz, P., & Jonas, A. E. G. (2021). Circularity as Alterity? Untangling Circuits of Value in the Social Enterprise – Led Local Development of the Circular Economy. Economic Geography, 97(3), 257–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2021.1931109

Merli, R., Preziosi, M., & Acampora, A. (2018). How do scholars approach the circular economy? A systematic literature review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 178, 703–722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.12.112

Mhatre, P., Panchal, R., Singh, A. and Bibyan, S., 2021. A systematic literature review on the circular economy initiatives in the European Union. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 26, pp.187-202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2020.09.008

Minunno, R., O’Grady, T., Morrison, G.M. and Gruner, R.L., 2020. Exploring environmental benefits of reuse and recycle practices: A circular economy case study of a modular building. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 160, p.104855. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.104855

Morseletto, P. (2020). Targets for a circular economy. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 153(November 2019), 104553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.104553

OECD (2023), “ A circular transition for construction”, in Towards a National Circular Economy Strategy for Hungary, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/9347f752-en

O’Grady, T., Minunno, R., Chong, H.Y. and Morrison, G.M., 2021. Design for disassembly, deconstruction and resilience: A circular economy index for the built environment. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 175, p.105847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.105847

Ogunmakinde, O. E., Sher, W., & Maund, K. (2019). An assessment of material waste disposal methods in the Nigerian construction industry. Recycling, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.3390/recycling4010013

Osei-Tutu, S., Ayarkwa, J., Osei-Asibey, D., Nani, G., & Afful, A. E. (2023). Barriers impeding circular economy (CE) uptake in the construction industry. Smart and Sustainable Built Environment, 12(4), 892–918. https://doi.org/10.1108/SASBE-03-2022-0049

Otasowie, O.K., Aigbavboa, C.O., Oke, A.E. and Adekunle, P., 2024. Mapping out focus for circular economy business models (CEBMs) research in construction sector studies–a bibliometric approach. Journal of Engineering, Design and Technology. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEDT-10-2023-0444

Papamichael, I., Voukkali, I., Loizia, P., & Zorpas, A. A. (2023). Construction and demolition waste framework of circular economy: A mini review. Waste Management and Research, 41(12), 1728–1740. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734242X231190804

Paul, S.O. and Ofuebe, C., 2021. The United Nations Industrial Development Organization’s Role in Modern Industrialization of Nigeria. International Economic Policy, (34), pp.115-138. https://doi.org/10.33111/iep.eng.2021.34.06

Ranganathan, P., & Caduff, C. (2023). Designing and validating a research questionnaire - Part 1. Perspectives in Clinical Research, 14(3), 152–155. https://doi.org/10.4103/picr.picr_140_23

Ruiz, L.A.L., Ramón, X.R. and Domingo, S.G., 2020. The circular economy in the construction and demolition waste sector–A review and an integrative model approach. Journal of Cleaner Production, 248, p.119238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119238

Schöggl, J. P., Stumpf, L., & Baumgartner, R. J. (2020). The narrative of sustainability and circular economy - A longitudinal review of two decades of research. In Resources, Conservation and Recycling (Vol. 163). Elsevier B.V. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.105073

Singhal, D., Tripathy, S., & Jena, S. K. (2020). Remanufacturing for the circular economy: Study and evaluation of critical factors. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 156(January). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.104681

Talamo, C., Lavagna, M., Monticelli, C., Zanelli, A., & Campioli, A. (2021). Remanufacturing: strategies to enhance the life extension of short-cycle building products. Techne, 22, 71–78. https://doi.org/10.36253/techne-10591

Upadhayay, S., Alqassimi, O., Khashadourian, E., Sherm, A., & Prajapati, D. (2024). Development in the Circular Economy Concept: Systematic Review in Context of an Umbrella Framework. In Sustainability (Switzerland) (Vol. 16, Issue 4). Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MPDI). https://doi.org/10.3390/su16041500

Zhang, C., Hu, M., Di Maio, F., Sprecher, B., Yang, X. and Tukker, A., 2022. An overview of the waste hierarchy framework for analyzing the circularity in construction and demolition waste management in Europe. Science of the Total Environment, 803, p.149892. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149892

Zulu, S.L., Zulu, E., Chabala, M. and Chunda, N., 2023. Drivers and barriers to sustainability practices in the Zambian Construction Industry. International Journal of Construction Management, 23(12), pp.2116-2125. https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2022.2045425

Zuofa, T., Ochieng, E.G. and Ode-Ichakpa, I., 2023. An evaluation of determinants influencing the adoption of circular economy principles in Nigerian construction SMEs. Building Research & Information, 51(1), pp.69-84. https://doi.org/10.1080/09613218.2022.2142496